Abstract

Despite their increasing frequency and magnitude, research on how polycrises influence policymaking has been remarkably scarce. In this article, we approach this issue from an evidence-based policy learning perspective. We explore how the polycrisis involving the progressive intersections between the climate change crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the energy crisis influenced evidence-based policy learning underlying the European Union’s climate policymaking. Our findings show that at the initial phases of the polycrisis, interdisciplinary scientific evidence was employed to depoliticize the climate change crisis and facilitate a paradigmatic policy shift. Yet, as relatively faster burning crises overlapped, such evidence played an increasingly substantiating role for previously established institutional choices, and then its role further diminished as more crises overlapped. These findings offer a more robust theoretical understanding of evidence-based policy learning and its contribution to policy change within polycrises. This also draws practitioners’ attention to the need for actively re-aligning evidence-based policy learning practices as political conditions evolve during polycrises.

1. Introduction

Polycrises occur when multiple crises overlap, often reinforcing the negative impacts of one another. As a concoction of multiple crises, they significantly influence policymaking as each of the constituent crises often entails conflicting solution strategies to those of others. Polycrises have been proven particularly challenging to address within existing crisis response architectures, which are more adapted to addressing bounded, unidimensional, and individual crises. The impacts of polycrises have been substantial, so much so that they featured in the European Union’s (EU) top diplomat Jean-Claude Juncker’s famous speech where he proclaimed that the overlap between the refugee crisis, the financial crisis, the Brexit referendum, and security threats unleashed the EU’s most formidable challenges since the Second World War (Juncker Citation2016). Yet, despite their increasing occurrence and magnitude, research on polycrises is remarkably scarce. Existing research predominantly paints a broad view of potential macro-level outcomes of polycrises. For example, research associates polycrises with cultivating institutional political leverage (Meissner and Schoeller Citation2019; Laffan Citation2023), or reinforcing political narratives (Hloušek and Havlík Citation2023). However, how polycrises influence policymaking processes is seldom researched and is largely ambiguous.

In this article, we address this gap from an evidence-based policy learning lens. Here, evidence-based policy learning can be understood as policy actors’ pursuit of policy issue-related evidence within an evolving context aiming to generate and implement policy solutions (Zaki, Wayenberg, and George Citation2022; Blum and Pattyn Citation2022). The premise of this learning-based approach to policy analysis is: if we understand why, how, and what policymakers learn about policy problems under evolving conditions, we can better explain policymaking processes, policy choices, outcomes, and trace their underlying causal mechanisms (Zaki Citation2023a).

Accordingly, our central question is How does the progression of a polycrisis affect evidence-based policy learning processes?

Given the scarcity of prior research on the issue, we employ an exploratory case design to provide a preliminary account of key changes in evidence-based policy learning approaches within a polycrisis. To do so, we analyze the case of the EU’s climate policy along the development of one of the union’s most pronounced polycrises: The progressive intersections between the climate change crisis, particularly in the period starting 2018 leading up to the European Green Deal (EGD), the COVID-19 pandemic, and the energy crisis resulting from the Russian war in Ukraine. Three crises, the intersection of which, had substantial implications for the EU climate policy (von Homeyer, Oberthür, and Jordan Citation2021; Dupont, Rosamond, and Zaki Citation2024; Winkler and Jotzo Citation2023). We source our data from 10 senior key informant interviews from the European Commission (EC), experts from the European Environment Agency (EEA), and analysis of various documents including scientific publications, reports, and communiques by the EC and other relevant stakeholders.Footnote1

In doing so, this article makes four main contributions. Theoretically, we offer a better understanding of policymaking and policy change during polycrises. Second, we contribute to the budding literature on policy learning governance. That is understanding how actors deliberately shape and adjust policy learning processes in response to evolving conditions (Zaki Citation2024). Empirically, we offer a novel understanding of EU policymaking within a polycrisis context. Last, we point practitioners’ attention to the need for actively re-aligning evidence-based policy learning practices in response to shifting conditions as a polycrisis develops. Here, we do not aim to create a quantitative or bibliographical account of the evidence mix or assess the quality of evidence. Rather, we illustrate the changes in the way evidence is identified and used as a polycrisis develops, particularly at the political leadership level.

First, we review the literature on polycrises, policy learning, and evidence-based policymaking in Section 2. Then, we establish our methodological and analytical frameworks in Section 3. The empirical analysis is presented in Section 4, discussions and implications for research and practice are then offered in Section 5.

2. Polycrises, policy learning, and evidence

2.1. Polycrises: setting the scene

Polycrises are considered a new lens for viewing the world where we depart from linear simplified understandings of cause and effect based on a single crisis episode, toward viewing the complexity of “clumping” interconnected critical events (Henig and Knight Citation2023). Recently, Davies and Hobson (Citation2022) offered one of the very few concise attempts at outlining key features of a polycrisis, in aggregate, being: (1) separate yet simultaneously occurring and interacting crises, with feedback loops, affecting and amplifying each other; (2) spillovers between crises contribute to their entanglement, creating layered social problems with competing ideological preferences and interests; (3) Thus, there is little consensus on a polycrisis definition, and solution pathways; (4) given complex layering, each crisis solution can impede, contradict, or discount the effectiveness of solutions to the other crises; (5) the interaction of these crises creates “emergent properties” where the resulting polycrisis is beyond the sum of its individual crises.

Existing research views polycrises as an exogenous policy context where institutional theories are often adopted to illustrate system-level outcomes. For example, the decentralization of decision-making (Freudlsperger and Weinrich Citation2021), the accumulation of institutional power (Laffan Citation2023), increasing politicization, or eroding trust in political leadership (Zeitlin, Nicoli, and Laffan Citation2019). Interestingly, the effects of polycrises are not only negative. They have also been linked to desirable (albeit often painstaking) evolutions. For example, the EU’s previous polycrisis eventually contributed to strengthening the European Monetary Union and accelerating European integration (see von Homeyer, Oberthür, and Jordan Citation2021). Overall, research on polycrises has hitherto been apt in identifying the intersection of crises, and (lately) painting a broad view of their systemic implications. However, understanding policymaking processes within polycrises is yet to develop. In the next section, we elaborate on how policy learning from evidence can be pursued as a powerful lens to addressing this gap.

2.2. Policy learning, evidence, and crises

Policy learning can be understood as a process by which policy actors deliberately seek information and knowledge, aiming to develop better understanding of potential solutions to evolving policy problems (Zaki, Wayenberg, and George Citation2022). In this learning process, there is an increasing reliance on “evidence” as policy problems become more complex, and accountability demands grow louder. Here, evidence can be broadly understood as certified (i.e. somewhat reliable) knowledge and information regarding a certain policy issue (Blum and Pattyn Citation2022). Thus, there is no single normative standard for what constitutes evidence for policy learning or policymaking. Rather, evidence is what policy actors construe (or could frame as) as being closest to accurate depictions of reality. This is particularly as policymakers have different attitudes on that matter, depending on their experiences, backgrounds, and perceptions (Piddington, Mackillop, and Downe Citation2024). Furthermore, while reliable evidence is supposedly the most sought-after commodity in policymaking, in practice the very idea of best evidence remains elusive as both the production and consumption of knowledge and evidence are subject to scientific and political contestation. For example, different expert or social groups can produce contradicting knowledge and information given their epistemological preferences and approaches (e.g. Pattyn, Gouglas, and De Leeuwe Citation2020). Also, while policy actors proclaim that “guided by science” and “following evidence” are their policymaking creeds, they can either misidentify the optimal evidence to learn from or cherry-pick what comports with their political and ideological preferences within what Zaki and Wayenberg (Citation2021) call a “marketplace” of evidence. As such, the idea of a pure or “true” evidence-based policy learning and policymaking is often considered an untenable ideal (Cairney Citation2022, Citation2023).

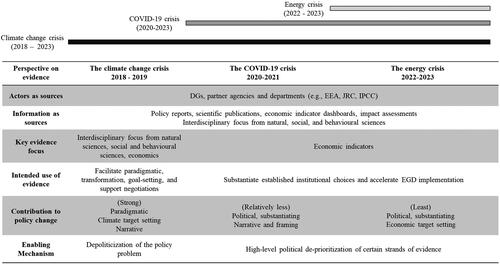

Consistent with our conceptual approach, there are three main perspectives to approach evidence related to policy learning, as shown in : sources, types, and intended use. Sources can be described both in terms of repositories, and actors involved. Evidence can be collected from different repositories including policy evaluations and performance indicators (Sanderson Citation2002), scientific publications (Zaki and Wayenberg Citation2021), or drawing on tacit knowledge within institutions, and from other policy experiences across time, space, and policy domains (Newig et al. Citation2016). Also, in terms of sources, different actors can engage in evidence provision and interpretation. For example, specialized organizational actors such as those focused on specific policy domains like public health, the environment, and others. This is in addition to special interest groups, political advocacy coalitions, scientific communities, citizens, and different stakeholder groups with experiences relevant to problems being addressed. These sources can provide various types of evidence with different ways to describe reality. For example, through behavioral and societal, or technical indicators (Zaki, Pattyn, and Wayenberg Citation2023). The third, and perhaps one of the most important perspectives is the intended use of evidence. Evidence can be used to formulate technical solutions to policy problems. For example, to combat climate change through calibrating emission level restrictions (e.g. Dupont, Rosamond, and Zaki Citation2024), or handle a pandemic through stipulating rules for social contacts or vaccinations (e.g. Zaki and Wayenberg Citation2023). However, evidence is not exclusively used to formulate successful technical solutions (Mavrot and Pattyn Citation2022). The same sources and types of evidence (e.g. knowledge from scientific evidence and expert communities) can be deliberately used to legitimize pre-determined or favorable policy positions or accumulate political capital (e.g. Boswell Citation2008). Furthermore, focusing on particular types of evidence can also be used to depoliticize issues and facilitate unopposed decision-making (Cairney Citation2022). Intentions for evidence use can be motivated by several factors such as policy issue features. Depending on issue salience, and degree of politicization, policy actors can be more inclined toward political or programmatic (technical) use of evidence (see Trein and Vagionaki Citation2022). Another factor concerns institutional legacies and the path dependence generated by preexisting policy choices. Here, policy actors use evidence in ways that generate optimal returns (political or technical), consistent with their institutional preferences, objectives, and policy priorities (e.g. Zaki and Wayenberg Citation2021).

Table 1. Main sources, types, and intended uses of evidence.Footnote2

Now we turn to why would we expect those approaches to evidence-based policy learning to change when different crises intersect as a polycrisis develops? In other words, why would the layering of crises create junctures at which evidence-based policy learning approaches vary?

While extant research does not tell us much about policy learning during polycrises, drawing on single-crisis learning literature gives us insights. Fundamentally, crises present unexpected situations that pose threats to societal values and systems. Some of these crises “creep” or evolve over time, showcasing different intensity cycles, divisive risk perceptions, where values and goals driving crisis response become contested, and policy responses become politicized (Boin, Ekengren, and Rhinard Citation2020). To address such crises, policymakers often seek to support their decisions with evidence, serving two main purposes: first is to deliver effective crisis responses under critical conditions where fault tolerance is low. Second, to accumulate political capital, answer accountability demands, and guard against political contestation. Even within one crisis, this learning process is not static. To cope with crisis evolutions, i.e. changes in policy issue formulation or understanding, policymakers engage in policy learning governance. This can be understood as a process where they deliberately adjust types and sources of evidence used in policy learning to respond to an evolving policymaking context and requirements (Zaki Citation2024). For example, they can establish new advisory structures, seek new sources of knowledge and information within and across scientific disciplines, or engage with different societal and political actors to certify their learning and acquire more comprehensive evidence as the crisis evolves (e.g. Petridou, Zahariadis, and Ceccoli Citation2020). A developing polycrisis can further exacerbate this dynamic in a threefold sequence. First, the introduction of a new crisis (i.e. a focusing event) presents a new policy issue that requires institutionalizing new policy learning processes, specifically catered for its knowledge and evidence requirements (Zaki Citation2024). Second, the effects of a newly introduced crisis spill over and influence previously ongoing crises, often making crises mutually reinforcing. Resultantly, solutions to a newly emerging crisis can compete against solutions to earlier crises for limited policy resources. Third, this creates something akin to a “Fujiwhara” effect where the two crises morph into a newly formed crisis with a more complex policy issue formulation that is beyond the sum of its constituent components (see Davies and Hobson Citation2022). Generally, with the introduction of a new crisis into the policy process, policymakers need to shift their attention from one issue to the other, seeking different types of evidence (see Cairney Citation2022). This can result in changes and tradeoffs between types, forms, and uses of evidence to address a continuously morphing polycrisis.

Put together, the intersection between a new crisis and ongoing ones acts as a juncture that is likely to prompt changes in evidence-based policy learning processes. Having said so, what are the particular changes that take place at these junctures? In the next section, we outline the analytical and methodological frameworks we use to address this question.

3. Methodological framework

To explore how does the progression of a polycrisis affect evidence-based policy learning, we leverage the background conceptualization outlining the process’ key dimensions: actors involved, types and sources of evidence, and intended use of evidence, while accounting for an evolving policy context (see Zaki, Wayenberg, and George Citation2022). In , we illustrate how these key variables were operationalized.

Table 2. Operationalization of key variables.

To answer our research question, we use the case of the European climate policy in the period between 2018 and 2023. This period embodied one of the EU’s most intense polycrises, that is the progressive layering of the climate change crisis, with the COVID-19 pandemic, and the energy crisis resulting from the Russian invasion of Ukraine. All crises which have significantly impacted the Union’s climate and environmental policy. These are also crises where crisis-specific policy learning processes were already observed in emerging literature. Furthermore, specific policy packages have been developed in response to each of the three crises, all with a narrative of evidence-based policymaking: the (EGD) was launched in 2019 in response to the climate change crisis, the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) was launched in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2021, and the REPowerEU package was launched in 2022 in response to the energy crisis. While climate change has been declared a crisis for decades, our analysis focuses on the period from 2018 onwards as it has witnessed the most recent uptick of evidence-based policy learning leading up to the formulation and launching of the EGD (see Zaki and Dupont Citation2023; Dupont, Rosamond, and Zaki Citation2024).

To create our exploratory account, we source our data from 10 interviews with senior officials and experts from the EC and the EEA.Footnote3 Specifically, the two Directorates spearheading environmental and climate policy, the Directorate General for Environment (DG-ENV) and the Directorate General for Climate Action (DG-CLIMA). We employ data source triangulation from official reports, communiques, and published literature. Interviews and documents were analyzed using NVivo using an abductive approach to the development of coding categories.

In designing the above analytical framework, we follow a coherent approach in the empirical identification of learning. This starts with a clear conceptualization, viewing learning as a deliberate pursuit of information and knowledge. Then, we design a measurement instrument consistent with the underlying theoretical assumptions where we use a case study drawing triangulated data from multiple sources over an extended period to allow for learning impacts to materialize and become empirically traceable. Finally, we deploy the measurement instrument in an empirical context best suited to identify the learning process in question such as the EU’s environmental and climate policy domain. A setting where there are multiple streams of evidence with a significant level of discrection for their selection and use. Isolating learning observations at the institutional level, from those emerging from respondents’ developing individual understandings over time is one of the most difficult challenges in policy learning research. To address this challenge, our approach was threefold. First, by focusing on participants with more than 15 years of experience within the EU’s climate and environmental policy, we gather firsthand accounts of learning not only during the polycrisis in question, but also of earlier crises. This helped compare and triangulate insights and better report on the institutional aspect of learning. Second, we triangulated key informant interview inputs against published documents by the EC and other secondary sources such as scientific publications. Third, we deliberately only focused on closely connected directorate generals, helping minimize any differences resulting from across-domain variations. This approach is consistent with the recommendations on designing methodological frameworks for empirically identifying policy learning as proposed by Zaki and Radaelli (Citation2024).

In the next section, we present a longitudinally structured analysis of evidence-based policy learning across three phases of the polycrisis development: the climate change crisis leading up to the EGD between 2018 and 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic between 2020 and 2022, and the energy crisis between 2022 and 2023.

4. Case analysis

4.1. Phase I: climate change and the European Green Deal

Climate change has been long recognized as a crisis, particularly within the EU, going back (Burns and Tobin Citation2018; Oberthür and von Homeyer Citation2023). As a transboundary problem with varying levels of intensity, uneven distributional impacts, its level of politicization and salience have varied over time (Dupont, Rosamond, and Zaki Citation2024). Accordingly, it is one of the most emblematic examples of a “creeping crisis” where significant political contestation underlies potential solutions (Zaki Citation2023a). Scientific evidence regularly featured, sometimes in fleeting cameos within climate policy debates (Hildén, Jordan, and Rayner Citation2014), sometimes taking a backseat to painstaking political priorities (Dupont et al. Citation2023). However, increasing public recognition, politicization, and advocacy by scientific establishments increased impetus for learning from scientific evidence in climate policy over the last decade (Zaki and Dupont Citation2023). This contributed to ambitious systemic targets, and rigorously developed performance indicators, more cognizant of planetary boundaries (INT-01Footnote4; EEA Citation2015; DG Clima Citation2016). Eventually, this contributed to the development and launch of the EGD in 2019, which was considered an ambitious, paradigmatic science-driven path-breaking shift from earlier patterns of climate policymaking (see Dobbs, Gravey, and Petetin Citation2021; Dupont et al. Citation2023; INT-01, INT-07, INT-08, INT-09).

This new systemic approach to climate policy was largely formulated and legitimized by integrating evidence from a wide spectrum of scientific expertise and disciplines, from natural and climate sciences to, governance, and policy (Schunz Citation2022; Zaki and Dupont Citation2023; INT-01, INT-06). There, the EC explicitly emphasized the need to learn driven by the “rapid development of scientific evidence” and using real-life performance indicators (European Commission Citation2019a). The use of evidence in the development and framing of the EGD had two main objectives. First, as an overarching approach, it contributed to the EC’s assertion of top-down political control over the environmental and climate policy agenda where the commission’s leverage over national climate ambitions increased. This was pursued through instrumentalizing evidence to depoliticize the climate change issue. Here, the narrative focused on technocratic governance, directly establishing a new transdisciplinary and systemic way to think about the environment. Thus, excluding political contentions as much as possible (Samper, Schockling, and Islar Citation2021; INT-06). Within this approach, scientific evidence was used to fulfill a normative role corresponding to the public demand driven by the budding climate movement (see Domorenok and Graziano Citation2023). Consistently, while there was consensus on the importance of scientific evidence in formulating the EGD, the instrumental and strategic use of evidence in political bargaining was also notable (Guéguen and Marissen Citation2022).

Within the EGD framework itself, evidence was used in two ways. Programmatically, to improve future decision-making as part of the EC’s Better Regulation agenda (European Commission Citation2019b). Second, to set and track performance targets in key areas. For example, air pollution waste generation and treatment, the ecological conditions of EU waters, bird populations (reversing or halting decline as a proxy of biodiversity), among other indicators (e.g. DG-ENV Citation2019). This was not only limited to confirmed knowledge but was also sensitive to emerging evidence. There, the precautionary principle (as a relatively new regulatory philosophy, also not entirely apolitical) was invoked to allow even preliminary scientific evidence to shape regulation in cases such as in the case of Endocrine disruptors (European Commission Citation2018; INT-06). Accordingly, evidence was sourced through different actor groups, for example, including the EEA, the Joint Research Center (JRC), different directorate generals within the EC as well as the broader scientific research community (INT-01, INT-02, INT-03). This meant that various repositories were also used, for example, periodic reports from the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), policy evaluations, and scientific literature (e.g. European Environment Agency Citation2019). This overarching strategy toward using evidence in the formulation of the EGD was deliberately pursued by the EC by engaging with a broad spectrum of experts and community actors, for example, through empowering forums for debate, consultation, and networking (e.g. Zaki and Dupont Citation2023; Dupont, Rosamond, and Zaki Citation2024).

Shortly after the EGD was announced in December 2019 and as momentum for its implementation was building up, the COVID-19 crisis came into the scene being declared a global pandemic in March 2020. A phase to which we now turn.

4.2. Phase II: the COVID-19 pandemic

The transboundary nature and impact of the COVID-19 crisis had substantive implications for the then-nascent EGD. When the crisis hit, the EC was in the middle of crafting the “fit for 55” package which aimed at updating EU legislation to reduce net greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030. When the economic fallout of the pandemic became evident, there was genuine concern whether the EC would be able to maintain the present level of ambition while providing an adequate economic crisis response, especially as many member states initially called for abandoning several core EGD commitments to facilitate economic recovery (Carević Citation2021; INT-04, INT-07, INT-10). Hence, the COVID-19 crisis was debated as a potential critical juncture for EU climate policy where even within the Commission there was anticipation whether the senior political leadership was going to “ditch the Green Deal completely” (INT-09). The outcome of this juncture largely depended on the Commission’s political will, and its ability to act entrepreneurially and strategically to create substantive synergies between the narratives surrounding core EGD objectives and COVID-19 economic recovery (e.g. see Dupont, Oberthür, and Von Homeyer Citation2020; Bongardt and Torres Citation2022).

Early on policies such as the pandemic crisis support fund, and the emergency purchase program came as responses to the initial shock, thus there was limited time to learn from evidence. However, the EU’s post-shock responses such as the RRF were formulated through deliberate learning processes where policymakers had sufficient space to learn from evidence and past experiences (see Ladi and Tsarouhas Citation2020). During this phase, the EC showed the political determination to use the recovery facility to further ground the EGD (INT-05, INT-06, INT-09). For example, by only financing recovery measures compliant with the no significant harm principle concerning the EU’s environmental objectives (Carević Citation2021). To do so, the EC also leveraged narratives of expertise, knowledge, and evidence (see Ryner Citation2023), as well as used evidence-based framings to accelerate sustainable transitions, a process where “the political will has been extremely important” (INT-04, INT-09).

From a learning perspective, this was approached through two main ways. First, doubling down on EGD policy choices via employing similar evidence-based policy learning practices in the period leading up to the EGD’s launch where “the usual stakeholders (actors) were being involved.” There, relationships with evidence-supplying actors such as the JRC, EEA, and across DGs became even stronger as the need for substantiating targets and indicators grew (INT-04, INT-07, INT-08; DG-Clima Citation2020). Second, using such evidence to gingerly craft narratives that link EGD building blocks to recovery funds, thus accelerating EGD adoption and preventing potential backsliding (INT-07; Bongardt and Torres Citation2022). This process was largely shaped by the political determination aiming to maintain the course toward climate neutrality enshrined in the EGD (INT-05).

As such, the COVID-19 crisis did not lead to substantive or qualitative changes to formal evidence-based policy learning structures and practices, particularly given that there was no genuine political intention to reformulate preexisting policy paradigms as one of our interviewees stated that “the utility of evidence and data depended very much on the willingness to see it.” As such, during this phase, little to no new disruptive evidence entered into the policy learning process. Rather, existing evidence was “complemented, completed, synthesized, and made accessible in different ways” (INT-05). Yet, during this phase, we start to see changes in how evidence was employed. Perhaps, one of the most notable changes was dedicating more weight to economic indicators, especially coming from economic operators and groups. This mainly manifested in framing and communicating RRF implementation, often in connection with pre-established EGD objectives (INT-04, INT-05, INT-07; European Commission Citation2020).

The EC’s use of evidence during this phase is consistent with observations as to why the COVID-19 crisis primarily had an “evolutionary” impact on the EGD implementation, instead of a transformational or “revolutionary” one where the existing fundamental gaps in the EGD could have been addressed. Rather, preexisting policy choices were confirmed (see Crnčec, Penca, and Lovec Citation2023). Next, we turn to the most recent layer of the polycrisis, which is the energy crisis of 2022.

4.3. Phase III: the energy crisis

As the EU established a path toward a “green” recovery from the COVID-19 crisis, a geopolitical shock with massive implications for climate, environmental, and energy policies hit when Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022. At the time, the EU was importing 35% of its natural gas from Russia. Hence, the invasion of Ukraine was considered another difficult test for the EU’s determination regarding climate and environmental policy with tangible risks of backsliding into pre-EGD energy consumption patterns. Also here, there was pressure to sideline the EGD to cope with the crisis impacts (Ciot Citation2022; INT-05, INT-10). However, in response to the crisis, under significant political pressure, and within a short duration, the EU mounted a strict regime of sanctions against Russia, eventually leading to gas imports dropping to around 24% by November 2022 (European Council Citation2023). This decisive response was somewhat unexpected where several actors were “surprised that the Russian war in Ukraine has not completely eclipsed EU Climate policy” (INT-05). In this phase, political commitment to the EGD and green recovery remained very high (INT-04, INT-06, INT-08, INT-09, INT-10).

Sudden reduction of Russian imports led to an energy crisis that disproportionately affected member states (Ciot Citation2022). Responding, the EU’s policy went in two main directions. First, stabilizing and optimizing current natural gas consumption. This included securing flows from alternative exporters such as the United States of America among others (European Council Citation2023). Additionally, a voluntary pledge to reduce gas demand by 15% was made by member states in July 2022 (Council of the EU Citation2022). Second, ensuring strategic long-term energy security. To do so, the EC launched the REPowerEU framework aiming to save energy, diversify supplies, and most importantly increase production of clean energy (European Commission Citation2022). Here, the EC substantively focused on further accelerating EGD implementation even more than in the previous phase (INT-08). Targets in the renewable energy directive were raised to 45% by 2030, compared to 40% in the previous year, outputs from new photovoltaic installations were to be doubled by 2025, and a million tons of domestic renewable hydrogen were to be produced by 2030. Additionally, targets for biomethane and hydrogen use were substantively increased, and the EU solar industry alliance was set up.

During this phase, the same sources, types, and actors involved in the evidence-based policy learning process were still present in the system as in the previous phase (INT-04, INT-05, INT-07, INT-09, INT-10). However, the narrative, focus, and use of particular types of evidence relatively receded. There was a notable reduction in evidence-based and knowledge narratives compared to the previous two phases. Instead, the narrative of accelerating the EGD implementation was used (often overused) without thorough analyses of implementation and impact assessments (Ciot Citation2022). An issue that contributed to targets and their delivery pathways being somewhat unclear (Wisniewski Citation2023). This was driven by a strong high-level political commitment to further accelerate EGD implementation and embed EGD narratives transversally, so much so that even while dealing with the fallout of the war in Ukraine, questions of environmental damage due to conflict were salient (INT-04, INT-05, INT-06). This once again stressed the highly political nature of this phase, particularly as questions of strategic autonomy and sovereignty were omnipresent compared to the case during the COVID-19 pandemic (INT-05, INT-09, INT-10).

In this phase, the focus further shifted to evidence drawn from economic indicators such as inflationary impacts, the positive effects of accelerating EGD implementation, changing prices of renewable technologies to support ambitious targets (INT-07). Hence, while similar types and sources of evidence were present in the system, it was “what evidence to put focus on” that has changed to address the most prominent issues (INT-05, INT-06, INT-10). Consistently, some key informants even argued that due to this crisis, we even altogether “got rid of knowledge in policymaking … and listened to whoever could shout loudest” under crisis pressure, when referring to prioritizing manifest social and economic issues over environmental ones (INT-07). One of the key contention points here was spurred by the EC’s drive toward the (de) regulation of green technologies. A case where different actors tried to mitigate the tensions between the political drive to accelerate EGD implementation and “deregulation with detrimental impacts to the environment” (INT-08). An issue that some believe contributed to sidelining evidence from climate sciences in favor of more political and economic objectives leading to an “industrial green deal” (INT-07). This took place through high-level leadership de-prioritizing certain strands of scientific evidence, something recently observed within the EC’s policymaking. For example, when prioritizing political agenda and functions over particular values, such as in the case of bargaining over the rule of law mechanism with Poland and Hungary in return for their approval of the EU’s budgetary package including the Multiannual Financial Framework 2021–2027 and Next Generation EU (see Dobbs, Gravey, and Petetin Citation2021). This represented an intention to double-down on the previously established trajectory, an approach consistent with European Institutions’ affinity for continuity, especially concerning recently established paths (see Müller Citation2023). Accordingly, during this phase, holders of scientific evidence raced to “tag on to the (political) engine room in the Berlaymont”Footnote5 and “modulate” political responses that overlooked some strands of evidence to make them more consistent with environmental considerations (INT-09).

Notably, under (yet another) crisis shock and political pressure for a swift response, the consultation processes and evidence collection did not always have sufficient time to occur compared to the previous phases (INT-06, INT-08, INT-09). Sometimes, this affected the quality of legislative drafts and to some, did not create conditions conducive to the inclusion of solid scientific evidence (INT-07). As such, in this phase, we see evidence trying to catch up with, and re-align political preferences, rather than drive them.

With an exploratory account of the general approach to evidence-based policy learning along the culmination of the polycrisis, we discuss our findings in the next section.

5. Discussion

To synthesize our findings, it is first important to briefly highlight how the polycrisis affected EU climate policy. Before the polycrisis, as individual crises were relatively few and far apart (e.g. the eurozone crisis, Brexit, etc.), we saw them detracting attention from the climate change crisis and limiting climate policy ambitions (see Burns and Tobin Citation2018). However, the fast-paced overlaps between emerging crises as the polycrisis developed helped create a window of opportunity for the EC’s political leadership to play an entrepreneurial role and accelerate the EGD implementation. A process where learning from evidence played a strong, albeit varying role.

Leading up to the EGD, public pressure, and strong advocacy for ambitious climate action policies have led to a strong uptake of scientific evidence and facilitated a paradigmatic transformation of climate policy manifesting in the adoption of the EGD (Zaki and Dupont Citation2023). There, Interdisciplinary evidence helped formulate a systemic and ambitious agenda for climate action. This was enabled by the long timespan of the crisis, allowing for a deliberate discursive use of evidence (e.g. Dupont, Rosamond, and Zaki Citation2024). As the COVID-19 crisis hit, while the same types, and sources, of evidence remained available, its use has changed. Via a “soft” process of political de-prioritization, evidence on economic performance enjoyed relatively more attention than from climate and environmental sciences. Facilitated by higher time pressure, policy actors leveraged economic evidence to cement the EGD by linking it to recovery narratives and linking financing to EGD objectives. This is rather than using more interdisciplinary comprehensive evidence to address existing “technical” gaps in the previously established policy framework (see, e.g. Crnčec, Penca, and Lovec Citation2023).

When the energy crisis hit, and as the EGD paradigm was already more established, both the use and narrative of evidence relatively receded. Facilitated by an even more fast-burning nature of the energy crisis, goal setting has been largely driven by high-level political commitment. This was at the expense of genuine reflections on implementation challenges driven by interdisciplinary scientific evidence and managerial expertise. Here, we also see a wider use of economic evidence and indicators to accelerate EGD implementation.

So, how did this polycrisis affect evidence-based policy learning? As polycrisis developed, strong political commitment contributed to cementing a recently established evidence-driven paradigmatic transformation (the EGD). Accordingly, during the second and third crises, at the leadership level evidence-based policy learning was gradually less used in a deep discursive manner to scrutinize gaps in existing policies, but more to stabilize preexisting institutional choices.

This seems to be facilitated by strong legitimation capacity driven by strong political acumen (see Woo, Ramesh, and Howlett, Citation2015). As such, changes in the use of evidence during the polycrisis were not always driven by the logics of scientific suitability, or practical viability as our respondents shared that “if the political narrative changes, the question will be what type of evidence will policymakers use to justify one or the other narrative” and that if there was “scientific evidence that might not be “convenient” at some point in time, then it will not be taken into account.” This builds on emerging literature emphasizing the subterranean schisms between the proclaimed depoliticized use of evidence, power-driven approaches, and the actual way evidence is used in EU policymaking (e.g. Ryner Citation2023; Juntti, Russel, and Turnpenny Citation2009). Especially, concerning the use of evidence to legitimize preexisting institutional choices rather than informing new ones (Souto-Otero Citation2013). Our analysis has shown that during longer creeping crises, scientific evidence can get more space to paradigmatically infiltrate policymaking. Yet, as faster-burning crises overlap, this gradually changes where evidence plays a more substantiating role, and then its role further diminishes. This is particularly as newly introduced crises compete for attention, and resources as shown in .

While these findings show that the polycrisis affected the breadth and depth of evidence-based policy learning, in this particular case, this was not necessarily a catastrophic outcome. Here, it eventually contributed to cementing an ambitious transition toward climate neutrality, also thanks to strong political entrepreneurship of the Commission and other actors. However, in our case, as well as others, this can also have adverse effects. Chiefly, missing out on the potential use of evidence to scrutinize existing choices and address gaps therein. It can also undermine the credibility of evidence-based policymaking narratives, and the legitimacy of the policymaking altogether. With these results showcased, where do we go from here? In the next section, we present concluding remarks including an account of limitations, implications for practice, and avenues for future research.

6. Concluding remarks and implications for practice

Before concluding, some caveats and an account of limitations are warranted. First, we do not make normative or quality assessments of decision-making within the polycrisis. Rather, we observed how the general approach to evidence-based policy learning changed as the polycrisis developed, particularly at the political leadership level. Second, we do not assess if the logic of evidence-based policy learning and policymaking have changed at the sub-organizational level. If anything, our analysis shows that commitment to using scientific evidence has remained largely unchanged in different DGs, the EEA, and other units. Third, in our analysis of the relationship between politics and scientific evidence, we do not claim that at some phases, either of them was a sole driver of policymaking. Politics, learning and evidence are inseparable. What we do, however, is point to the ebbs and flows in the role of evidence and politics across different phases.

So, what do these findings mean for practice? Several implications can be drawn. First, there is a need to guard against the creeping influence of polycrises on the use of evidence in learning and policymaking. While our findings show that existing advisory structures, sources, and types of evidence did not formally change, shifting political priorities implicitly led to the de-prioritization of types of evidence that were considered central for policymaking. So, in terms of policy learning governance, changes in the use of evidence within polycrises can happen in a “soft” or creeping manner capitalizing on shifts in attention induced by overlapping crises with different priorities. This is rather than taking place via easily recognizable “hard” changes such as formal adjustments in advisory architectures often observed in single crises. Second, while polycrises are generally disruptive events with substantive adverse impacts, contingent on the entrepreneurial role of political leadership, practitioners can engage with polycrises as of opportunity for paradigmatic transformation, or the pursuit of ambitious policy objectives. This opens the space for long-term strategizing, particularly where long-term creeping crises exist (see Zaki Citation2023b). Third, the evolving conditions presented by polycrises call on practitioners to engage in active political learning and employ various advocacy strategies to enhance the uptake of scientific evidence in policymaking as political preferences shift. This can include narrative and semantic, governance, and socialization strategies (see Zaki and Dupont Citation2023).

Though our findings are robust and consistent, they are preliminary and relatively specific to the polycrisis, and policy domain analyzed. Perhaps one of the reasons our findings are consistent across sources is that climate and environment policy actors within the EC and partners (such as the EEA and the JRC) operate from an unwavering position where environmental conservation is a non-negotiable imperative. Accordingly, future research can explore evidence-based policy learning practices within a polycrisis context in other policy areas that could be more prone to shifting approaches and priorities such as economic and financial policy, migration, cohesion, among others. Additionally, given the evident role of political entrepreneurship in this polycrisis and its influence on facilitating policy change, future research could adopt a multiple streams perspective to analyze crises within a polycrisis as separately flowing problem streams, focusing on how political actors can couple these streams to create windows of opportunity to facilitate paradigmatic change.

Acknowledgments

We would like to sincerely thank our three anonymous reviewers, and the journal editors for their very constructive comments and support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 Respondent inputs are not representative of the official positions of their respective organizations.

2 A non-exhaustive account of different sources, types, and uses of evidence. This table offers a brief synthesis of the most common varieties in policy learning literature.

3 All interviews were conducted between September and November 2023.

4 INT: Interview data.

5 The building housing the political leadership of the European Commission.

References

- Blum, S., and V. Pattyn. 2022. “How Are Evidence and Policy Conceptualised, and How Do They Connect? A Qualitative Systematic Review of Public Policy Literature.” Evidence & Policy 18 (3): 563–582. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426421X16397411532296.

- Boin, A., M. Ekengren, and M. Rhinard. 2020. “Hiding in Plain Sight: Conceptualizing the Creeping Crisis.” Risk, Hazards & Crisis in Public Policy 11 (2): 116–138. https://doi.org/10.1002/rhc3.12193.

- Bongardt, A., and F. Torres. 2022. “The European Green Deal: More Than an Exit Strategy to the Pandemic Crisis, a Building Block of a Sustainable European Economic Model.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 60 (1): 170–185. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13264.

- Boswell, C. 2008. “The Political Functions of Expert Knowledge: Knowledge and Legitimation in European Union Immigration Policy.” Journal of European Public Policy 15 (4): 471–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760801996634.

- Burns, C., and P. Tobin. 2018. “The Limits of Ambitious Environmental Policy in Times of Crisis.” In European Union External Environmental Policy: Rules, Regulation and Governance beyond Borders, edited by C. Adelle, K. Biedenkopf, and D. Torney, 319–336. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Cairney, P. 2022. “The Myth of ‘Evidence-Based Policymaking’ in a Decentred State.” Public Policy and Administration 37 (1): 46–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0952076720905016.

- Cairney, P. 2023. “The Politics of Policy Analysis: Theoretical Insights on Real World Problems.” Journal of European Public Policy 30 (9): 1820–1838. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2221282.

- Carević, M. 2021. “The COVID-19 Pandemic and the Implementation of the European Green Deal.” EU and Comparative Law Issues and Challenges Series 5: 903–925. https://doi.org/10.25234/eclic/18357.

- Ciot, M.-G. 2022. “The Impact of the Russian–Ukrainian Conflict on Green Deal Implementation in Central–Southeastern Member States of the European Union.” Regional Science: Policy & Practice 15 (1): 122–143. https://doi.org/10.1111/rsp3.12591.

- Council of the EU. 2022, July 26. Member States Commit to Reducing Gas Demand by 15% Next Winter. European Council. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2022/07/26/member-states-commit-to-reducing-gas-demand-by-15-next-winter/.

- Crnčec, D., J. Penca, and M. Lovec. 2023. “The COVID-19 Pandemic and the EU: From a Sustainable Energy Transition to a Green Transition?” Energy Policy 175: 113453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2023.

- Davies, M., and C. Hobson. 2022. “An Embarrassment of Changes: International Relations and the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Australian Journal of International Affairs 77 (2): 150–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357718.2022.2095614.

- DG Clima. 2016. Annual Activity Report. Brussels: European Commission.

- DG-Clima. 2020. Strategic Plan 2020–2024. Brussels: European Commission.

- DG-ENV. 2019. Annual Activity Report. Brussels: European Commission.

- Dobbs, M., V. Gravey, and L. Petetin. 2021. “Driving the European Green Deal in Turbulent Times.” Politics and Governance 9 (3): 316–326. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v9i3.4321.

- Domorenok, E., and P. Graziano. 2023. “Understanding the European Green Deal: A Narrative Policy Framework Approach.” European Policy Analysis 9 (1): 9–29. https://doi.org/10.1002/epa2.1168.

- Dupont, C., B. Moore, E. L. Boasson, V. Gravey, A. Jordan, P. Kivimaa, K. Kulovesi, et al. 2023. “Three Decades of EU Climate Policy: Racing toward Climate.” WIREs Climate Change 15 (1): e863. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.863.

- Dupont, C., J. Rosamond, and B. L. Zaki. 2024. “Investigating the Scientific Knowledge–Policy Interface in EU Climate Policy.” Policy & Politics 52 (1): 88–107. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557321X16861511996074.

- Dupont, C., S. Oberthür, and I. Von Homeyer. 2020. “The Covid-19 Crisis: A Critical Juncture for EU Climate Policy Development?” Journal of European Integration 42 (8): 1095–1110. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2020.1853117.

- EEA. 2015. The European Environment – State and Outlook 2015. Copenhagen: European Environmental Agency.

- European Commission. 2018, November 7. Endocrine Disruptors: A Strategy for the Future That Protects EU Citizens and the Environment. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_18_6287.

- European Commission. 2019a. The European Green Deal. COM (2019) 640. Brussels: European Commission.

- European Commission. 2019b. Annual Burden Survey. Brussels: European Commission.

- European Commission. 2020. COM(2020) – Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee, and the Committee of the Regions. Brussels: European Commission.

- European Commission. 2022. COM(2022) – Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee, and the Committee of the Regions. Brussels: European Commission.

- European Council. 2023, February 7. Infographic – Where Does the EU’s Gas Come From? https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/infographics/eu-gas-supply/#:∼:text=In%202021%2C%20the%20EU%20imported,)%2C%20particularly%20from%20the%20US.

- European Environment Agency. 2019. The European Environment – State and Outlook 2020. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. https://www.eea.europa.eu/soer/publications/soer-2020.

- Freudlsperger, C., and M. Weinrich. 2021. “Decentralized EU Policy Coordination in Crisis? The Case of Germany.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 60 (5): 1356–1373. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13159.

- Guéguen, D., and V. Marissen. 2022. Science-Based and Evidence-Based Policy-Making in the European Union: Coexisting or Conflicting Concepts? Bruges: College of Europe.

- Henig, D., and D. M. Knight. 2023. “Polycrisis: Prompts for an Emerging Worldview.” Anthropology Today 39 (2): 3–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8322.12793.

- Hildén, M., A. Jordan, and T. Rayner. 2014. “Climate Policy Innovation: Developing an Evaluation Perspective.” Environmental Politics 23 (5): 884–905. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2014.924205.

- Hloušek, V., and V. Havlík. 2023. “Eurosceptic Narratives in the Age of COVID-19: The Central European States in Focus.” East European Politics 40 (1): 154–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/21599165.2023.2221184.

- Juncker, J.-C. 2016, June 21. Speech by President Jean-Claude Juncker at the Annual General Meeting of the Hellenic Federation of Enterprises (SEV). European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/SPEECH_16_2293.

- Juntti, M., D. Russel, and J. Turnpenny. 2009. “Evidence, Politics and Power in Public Policy for the Environment.” Environmental Science & Policy 12 (3): 207–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2008.12.007.

- Ladi, S., and D. Tsarouhas. 2020. “EU Economic Governance and Covid-19: Policy Learning and Windows of Opportunity.” Journal of European Integration 42 (8): 1041–1056. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2020.1852231.

- Laffan, B. 2023. “Collective Power Europe? (the Government and Opposition/Leonard Schapiro Lecture 2022).”Government and Opposition 58 (4): 623–640. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2022.52.

- Mavrot, C., and V. Pattyn. 2022. “The Politics of Evaluation.” In Handbook on the Politics of Public Administration, edited by L. Andreas and S. Fritz, 243–254. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Meissner, K. L., and M. G. Schoeller. 2019. “Rising Despite the Polycrisis? The European Parliament’s Strategies of Self-Empowerment after Lisbon.” Journal of European Public Policy 26 (7): 1075–1093. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1619187.

- Müller, M. 2023. “Crisis Learning or Reform Backlog? The European Parliament’s Treaty‐Change Proposals during the Polycrisis.” Politics and Governance 11 (4): 311–323. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v11i4.7326.

- Newig, J., E. Kochskämper, E. Challies, and N. W. Jager. 2016. “Exploring Governance Learning: How Policymakers Draw on Evidence, Experience and Intuition in Designing Participatory Flood Risk Planning.” Environmental Science & Policy 55 (2): 353–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2015.07.020.

- Oberthür, S., and I. von Homeyer. 2023. “From Emissions Trading to the European Green Deal: The Evolution of the Climate Policy Mix and Climate Policy Integration in the EU.” Journal of European Public Policy 30 (3): 445–468. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2022.2120528.

- Pattyn, V., A. Gouglas, and J. De Leeuwe. 2020. “The Knowledge behind Brexit. A Bibliographic Analysis of Ex-Ante Policy Appraisals on Brexit in the United Kingdom and the European Union.” Journal of European Public Policy 28 (6): 821–839. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1772345.

- Petridou, E., N. Zahariadis, and S. Ceccoli. 2020. “Averting Institutional Disasters? Drawing Lessons from China to Inform the Cypriot Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic.” European Policy Analysis 6 (2): 318–327. https://doi.org/10.1002/epa2.1090.

- Piddington, G., E. Mackillop, and J. Downe. 2024. “Do Policy Actors Have Different Views of What Constitutes Evidence in Policymaking?” Policy & Politics 52 (2): 239–258. https://doi.org/10.1332/03055736Y2024D000000032.

- Ryner, M. J. 2023. “Silent Revolution/Passive Revolution: Europe’s COVID-19 Recovery Plan and Green Deal.” Globalizations 20 (4): 628–643. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2022.2147764.

- Samper, J. A., A. Schockling, and M. Islar. 2021. “Climate Politics in Green Deals: Exposing the Political Frontiers of the European Green Deal.” Politics & Governance 9 (2): 8–16. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v9i2.3853.

- Sanderson, I. 2002. “Evaluation, Policy Learning and Evidence-Based Policy Making.” Public Administration 80 (1): 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9299.00292.

- Schunz, S. 2022. “The ‘European Green Deal’ – A Paradigm Shift? Transformations in the European Union’s Sustainability Meta-Discourse.” Political Research Exchange 4 (1). https://doi.org/10.1080/2474736X.2022.2085121.

- Souto-Otero, M. 2013. “Is ‘Better Regulation’ Possible? Formal and Substantive Quality in the Impact Assessments in Education and Culture of the European Commission.” Evidence & Policy 9 (4): 513–529. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426413X662725.

- Trein, P., and T. Vagionaki. 2022. “Learning Heuristics, Issue Salience and Polarization in the Policy Process.” West European Politics 45 (4): 906–929. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2021.1878667.

- von Homeyer, I., S. Oberthür, and A. J. Jordan. 2021. “EU Climate and Energy Governance in Times of Crisis: Towards a New Agenda.” Journal of European Public Policy 28 (7): 959–979. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1918221.

- Winkler, H., and F. Jotzo. 2023. “Climate Policy in an Era of Polycrisis and Opportunities in Systems Transformations.” Climate Policy 23 (10): 1213–1215. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2023.2287284.

- Wisniewski, T. P. 2023. “Investigating Divergent Energy Policy Fundamentals: Warfare Assessment of Past Dependence on Russian Energy Raw Materials in Europe.” Energies 16 (4): 2019. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16042019.

- Woo, J. J., M. Ramesh, and M. Howlett. 2015. “Legitimation Capacity: System-level Resources and Political Skills in Public Policy.” Policy and Society 34 (3–4): 271–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polsoc.2015.09.008.

- Zaki, B. L. 2023a. “Practicing Policy Learning during Creeping Crises: Key Principles and Considerations from the COVID-19 Crisis.” Policy Design and Practice 7 (1): 87–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/25741292.2023.2237648.

- Zaki, B. L. 2023b. “Strategic Planning in Interesting Times: From Intercrisis to Intracrisis Responses.” Public Money & Management 43 (5): 521–524. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2023.2196028.

- Zaki, B. L. 2024. “Policy Learning Governance: A New Perspective on Agency in Policy Learning Theories.” Policy & Politics 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1332/03055736Y2023D000000018.

- Zaki, B. L., and C. Dupont. 2023. “Understanding Political Learning by Scientific Experts: A Case of EU Climate Policy.” Journal of European Public Policy 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2290206.

- Zaki, B. L., V. Pattyn, and E. Wayenberg. 2023. “Policy Learning Mode Shifts during Creeping Crises: A Storyboard of COVID-19 Driven Learning in Belgium.” European Policy Analysis 9 (2): 142–166. https://doi.org/10.1002/epa2.1165.

- Zaki, B. L., and C. M. Radaelli. 2024. “Measuring Policy Learning: Challenges and Good Practices.” Perspectives on Public Management and Governance. https://doi.org/10.1093/ppmgov/gvae001.

- Zaki, B. L., E. Wayenberg, and B. George. 2022. “A Systematic Review of Policy Learning: Tiptoeing through a Conceptual Minefield.” Policy Studies Yearbook 12 (1): 1–52. https://doi.org/10.18278/psy.12.1.2.

- Zaki, B. L., and E. Wayenberg. 2021. “Shopping in the Scientific Marketplace: COVID-19 through a Policy Learning Lens.” Policy Design and Practice 4 (1): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/25741292.2020.1843249.

- Zaki, B. L., and E. Wayenberg. 2023. “How Does Policy Learning Take Place across a Multilevel Governance Architecture during Crisis?” Policy & Politics 51 (1): 131–155. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557321X16680922931773.

- Zeitlin, J., F. Nicoli, and B. Laffan. 2019. “Introduction: The European Union beyond the Polycrisis? Integration and Politicization in an Age of Shifting Cleavages.” Journal of European Public Policy 26 (7): 963–976. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1619803.