?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The perplexing nature of Iran’s nuclear program is evident in its simultaneous growth of enrichment capacity and the concurrent denial of any aspirations toward nuclear weapons development. This conundrum calls for a rigorous examination of Iran’s deterrence policy and the identification of obstacles hindering the adoption of a nuclear deterrence strategy. The present study’s contribution is thus twofold. Firstly, employing a Systematic Literature Review (SLR) and the Delphi technique, it delves into the intricacies of Iran’s nuclear policy and identifies thirteen driving factors inhibiting the development of nuclear weapons. Secondly, by employing the DEMATEL technique, the article determines the importance of individual factors on Iran’s nuclear strategy as well as the causal relations among them. This study, which draws on the analysis of original data, concludes by highlighting the pivotal role of the Shia religion and the ideology of leaders in Iran’s way of war and deterrence strategy.

Introduction

The Iranian leadership consistently claims that Iran’s military strategy is essentially defensive, relying on deterrence for the safekeeping of the country in the face of external threats (Ajili and Rouhi Citation2019; Eslami and Vieira Citation2020, Citation2022, Citation2023). However, the United States, Israel, and Arab countries around the Persian Gulf have always seen Iran as their first-class threat (Ghanbari Jahromi Citation2015; A. M. Tabatabai and Samuel Citation2017; Takeyh Citation2003), especially following the development of Iran’s nuclear program since 2003 and its enrichment of uranium to 84% in 2023 that occurred alongside the rapid advancement of Iran’s intercontinental ballistic missile, hypersonic munitions, and drone programsFootnote1 (Eslami Citation2021, Citation2022).

This research investigates an internal view of Iran’s nuclear policy, decodes the black box of Iran’s strategy to deter its adversaries, and explains why and under what circumstances Iran has adopted this strategy and not others. After the US invasion of Iraq in 2003, “deterrence” (bazdarandegi) has been one of the key concepts in the statements of Iranian officials. There is a great deal of confusion, however, about the concept of deterrence in Iran. Reviewing the existing literature on Iran’s deterrence policy demonstrates two main research streams in the field. The first group of scholars claim that a sense of threat and insecurity has pushed Iran towards adopting a nuclear deterrence. Accordingly, Iran is developing or would need to develop nuclear weapons sooner or later (Dobbins Citation2011; Duus Citation2011; Edelman, Krepinevich, and Montgomery Citation2011; Evron Citation2008; Guldimann Citation2023; Guzansky and Golov Citation2015; Parasiliti Citation2009; S. Sagan, Waltz, and Betts Citation2007; Waltz Citation2012). The second group of researchers argues that Iran’s deterrence concept is independent of Iran’s nuclear program. To them, Iran’s deterrence is highly dependent on asymmetric ways of war, including ballistic missiles, proxies, drones, naval guerilla warfare, and cyber technologies (Ahmadian and Mohseni Citation2019, Citation2021; Ajili and Rouhi Citation2019; Freedman Citation2017; Olson Citation2016). This research is positioned in the second group of studies acknowledging that nuclear bombs are considered prohibited in Iran, and the country has decided to adopt a conventional (non-nuclear) deterrence against its adversaries. There is still a gap in Iranian security studies, however, which needs to be filled through systematic and comprehensive research. In particular, while most recent studies have been devoted to explaining how to deter Iran from acquiring nuclear bombs (Alcaro Citation2021; Byman Citation2018; Dalton Citation2017; Edelman, Krepinevich, and Montgomery Citation2011; Hicks and Dalton Citation2017; Katzman, McInnis, and Thomas Citation2020; Kaye and Wehrey Citation2023; Mandelbaum Citation2015; A. Tabatabai Citation2019), research explaining what kind of factors have been preventing Iran from adopting a nuclear deterrence have been rare.Footnote2

Aiming to identify the main factors preventing Iran from adopting nuclear deterrence, and to understand the impact of individual factors on Iran’s deterrence strategy, the present contribution draws on a mixed method of analysis. The aspiration to provide a more systematic account of Iran’s nuclear policy is in line with the most recent tendency to employ quantitative methods in security studies (Eslami, Sotudehfar, et al. Citation2021; Johnston Citation2016; Kaltenthaler, Silverman, and Dagher Citation2020; Liberman and Skitka Citation2019; Macdonald and Schneider Citation2019; Quek and Johnston Citation2017; S. D. Sagan and Valentino Citation2017). This innovative method of analysis was developed in three main phases: (1) a Systematic Literature Review (SLR), (extracting the elements preventing Iran from adopting a nuclear deterrence strategy from the existing literature); (2) Delphi technique (validating the findings by a panel of experts); and (3) survey (distributed among eighteen experts and evaluated through a DEMATEL technique), which demonstrates the impact of each factor on Iran’s nuclear deterrence and identifies the most influential factors driving Iran’s conventional deterrence and causal relationships among them.

While the subject of the forthcoming research is specialized and narrow, the number of people who have the necessary knowledge and background to participate in this research is limited. Accordingly, only two groups of Iranian experts were considered to be qualified participants in this study and the respondents to this survey. First, Iranian scholars with at least 15 years of experience in the field of security studies with an established record of publications on Iran’s nuclear strategy. Second, Iranian generals with the experience of participation and command of military operations during the Iran-Iraq war, in fighting ISIS, or others with the experience of participation and command of regional and extra-regional military missions and operations (mostasharane nezami). To this end, and in line with the mentioned standards, 27 experts were identified and contacted, of which 67%, corresponding to 18 experts, agreed to respond to study questionnaires.

This article is structured as follows. It begins with a short overview of Iran’s perspective on deterrence. It then explains and justifies the methodological approach, with the three steps of the proposed analysis discussed in three subsequent sub-sections. Finally, the article draws on the findings of the analysis and introduces factors preventing Iran from adopting nuclear deterrence and demonstrate the causal relations among them. The last section concludes.

Iran’s Concept of Deterrence

Before the revolution, Iran was one of America’s closest allies in the Middle East. The United States had considered no restrictions on the supply of weapons to Iran in order to prevent the influence of communism in Iran and the Middle East (Blight et al. Citation2012; Dolatabadi Citation2017). Accordingly, the United States had promised to meet Iran’s defense needs, provided that Iran made no attempt to acquire a nuclear weapon (Adib-Moghaddam Citation2006; Olson Citation2016; Shannon Citation2019). After the 1979 revolution, Iran’s foreign and security policy changed towards a new, anti-Western and hardline orientation (Adib-Moghaddam Citation2005).

The Islamic Revolution, which has been underpinned by the notion of religious democracy (mardom salari dini) complemented with velayat e faqih (the rule of Jurisprudence), has been inherently denying the interests of the great powers and opposing the existing world order (Ghamari-Tabrizi Citation2014; Murray Citation2009), with many international actors openly opposing Iran’s views in the international arena. Strategic challenges of post-Revolution Iran started immediately with the war with Iraq, followed by the war against terrorism and ISIS and proxy wars in the region (Eslami, Bazrafshan, Sedaghat, et al. Citation2021). However, the country has always been facing a comprehensive threat from the United States and Israel (Barzegar Citation2014; Chubin Citation2014; Connell Citation2010; Ghanbari Jahromi Citation2015). Nowadays, Iran is surrounded by many American military bases on the ground and many warships and submarines in the sea. This reality, in addition to the existing sense of threat and insecurity that was fostered especially by the experience of war with Iraq, has been pushing Iran to pay constant attention to its deterrence capabilities (Ajili and Rouhi Citation2019; Aminian and Zamiri-Jirsarai Citation2016; Papageorgiou, Eslami, and Duarte Citation2023; A. Tabatabai Citation2019; A. M. Tabatabai and Samuel Citation2017; Vieira Citation2023; Ward Citation2005)

After 2003 and the US attack on Iraq, the US invasion of Iran became Iran’s main threat. At the same time, the potential threat from Israel has always existed in Iran’s defense perception (Connell Citation2010; Czulda Citation2016; Taremi Citation2005). Adjusting its approach, by 2005, Iran developed the so-called “mosaic defense” doctrine. Besides a focus on naval and air-defense capabilities to disrupt the enemy’s control of the sea and air lanes, “mosaic defense” essentially employs an asymmetrical approach by the IRGC and the Army (Artesh), through the mobilization of a large, dispersed militia force to engage in attritional warfare against the invading forces (Ajili and Rouhi Citation2019; Olson Citation2016; Vatanka Citation2004). Iran’s uranium enrichment emerged in 2003 as a means of deterrence, however, in parallel with Iran’s security and defense programs.

While the emergence of terrorist groups in the region and insecurity in the borders of Iran affected Iran’s military behavior, several indicators attest that Iran has, since 2012, been changing its defensive/deterrent system, adding an offensive dimension by relying on hybrid warfare (Chubin Citation2009; Ghanbari Jahromi Citation2015; A. Tabatabai Citation2019; Yossef Citation2019). The associated “forward defense” doctrine implies that Iran should fight its opponents outside its borders to prevent conflict inside Iran (Olson Citation2016; Ajili and Rouhi Citation2019; Eslami and Al-Marashi Citation2023; Akbarzadeh, Gourlay, and Ehteshami Citation2023. Today, five main dimensions illustrate the nature of this deterrence policy and its offensive approach: ballistic missiles, proxies, drone and naval guerilla warfare, and cyber (Ajili and Rouhi Citation2019; Aminian and Zamiri-Jirsarai Citation2016; Connell Citation2010; Olson Citation2016).

However, Iran’s reliance on asymmetric ways of wars as a form of conventional deterrence has not implied that the country has disregarded the role of its nuclear program in its deterrence strategy. In other words, while there has been no concrete evidence of Iran’s intentions to develop nuclear weapons, the enrichment of uranium at a high level since 2003 has indicated Iran’s readiness to develop a clear military dimension of its ostensibly peaceful nuclear program. In this vein, under the guidance of Ayatollah Khamenei, Iran has devised a distinct approach to deterrence that has been leveraging the benefits of nuclear programs as a means of deterrence while simultaneously avoiding the strategic disadvantages stemming from the possession of actual nuclear weapons (Kazemzadeh Citation2020).

Analytical Framework: A Novel Methodological Approach

The main questions guiding the present study are (1) What factors prevent Iran from adopting a nuclear deterrence strategy? and, (2) What are the causal relations between the factors that prevent Iran from adopting a nuclear deterrence strategy?

To address the two research questions, the study employs a mixed-method approach (Johnson, Onwuegbuzie, and Turner Citation2007). Accordingly, it draws on a Systematic Literature Review (SLR) and Delphi technique to answer the first research question (Bench and Day Citation2010) and the DEMATEL technique to explore the causal relationships between the identified and validated factors (associated with the second research question). In this line, deploying the SLR serves to extract and identify the elements preventing Iran from adopting a nuclear deterrence strategy from the existing literature. The Delphi technique validates the identified factors and adding some missing elements in the existing literature by a panel of experts, and DEMATEL demonstrates the causal relations between the validated factors based on a data collected through an original survey of 18 experts.

A: Systematic Literature Review (SLR)

The state of the art on Iran’s deterrence policy demonstrates a number of elements driving Iran’s deterrence policy. Aiming to identify the factors preventing Iran from adopting a nuclear deterrence, a SLR was conducted (Paul et al. Citation2021). The SLR is “a specific methodology that locates existing studies, selects and evaluates contributions, analyses and synthesizes data, and reports the evidence in such a way that allows reasonably clear conclusions to be reached about what is known and what is not known” (Denyer and Tranfield Citation2009, 672). To this end, in the first stage of the SLR, eighty-nine studies about Iran which involve “deterrence” in their title or keywords and were published in main domestic and international databases within the time period of 2005–2023 were reviewed (see ).

Table 1. SLR algorithm.

In the second phase of the SLR, all existing studies were screened. The studies were filtered through context evaluation, scientific standard, time period, and line of argument. While excluding book chapters, think tank articles, conference papers, studies that were conducted before 2005, in addition to studies claiming that Iran’s deterrence predominantly is or tends to be nuclear, sixteen peer-reviewed articles were selected as the point of departure for extracting the main factors preventing Iran from adopting a nuclear deterrence strategy (see ).

Table 2. Studies found through the SLR review algorithm.

Focusing on the selected studies, a set of twelve factors preventing Iran from adopting a nuclear deterrence strategy were identified. According to the research conducted by local and international scholars, (1) international organizations such as the United Nations, (2) international agreements such as the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), (3) international pressures and threats including sanctions, (4) Shia religion, (5) no need for nuclear deterrence, (6) relying on conventional deterrence, (7) international security environment, (8) cost-benefit considerations, (9) the strategic culture of Iran, (10) cognitive decision-making process in Iran, (11) the ideology of the leaders, and (12) asymmetrical deterrence capabilities are the main factors deterring Iran from development of nuclear weapons (see Appendix 1).

The main criticism regarding the resulting set of twelve factors is their exact number and the subjectivity underpinning their selection. As such, the extracted factors need to be validated by a panel of experts through the Delphi technique before conducting the quantitative analysis.

B: Delphi Technique

The Delphi method provides a structured group communication process for a panel of experts to reach a consensus in collectively evaluating evidence and providing expert judgments. The method comprises two or more rounds of structured questionnaires, each followed by aggregation of responses and anonymous feedback to the participants (Mukherjee et al. Citation2015; Sablatzky Citation2022).

Aiming to measure the perception of experts regarding individual factors preventing Iran from developing a nuclear deterrence strategy, the study employed a Likert scale from 1 (for completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). According to Musa et al. (Citation2019), if the average of experts’ responses is more than 3.5, it can be inferred that the experts validate the factors. The rounds will be continued to the point that Kendall’s coefficient of each round reaches at 0.8 and this would be the stop point. In this research, four rounds of questionnaires were carried out with eighteen experts in February 2021 ().

Table 3. The result of Delphi method after four rounds of survey.

In addition to providing their perceptions on the factors identified in the SLR, the panel of experts suggested the inclusion of four new factors in the initial round of the Delphi survey. These factors are (1) the lack of financial resources for research and development, (2) scientific weakness and lack of access to scientific databases, (3) Iran’s logic/aspiration to prevent the formation of a nuclear competition in the region, and (4) public objection against weapons of mass destruction (WMDs). These four factors were incorporated into the second round of the Delphi survey.

Additionally, during the first round, 66% of the experts believed that “relying on conventional deterrence (via BMP)” should be merged with “asymmetrical deterrence capabilities and method of warfare of Iran”. Taking this into account, factor number 6 and 7 were combined. Furthermore, 83% of the experts considered “No need of Iran for nuclear deterrence” to be a consequence of Iran’s current deterrence strategy rather than a cause of it, and, therefore, this factor was excluded from the questionnaire based on their recommendation.

After distributing four rounds of questionnaires to eighteen experts, it was found that there was disagreement regarding the significance of “Public objection against WMDs” as a factor preventing Iran from adopting a nuclear deterrence strategy. The final average score for this factor was calculated to be 3.106, which is below the threshold of 3.5. Consequently, all experts agreed on the remaining thirteen factors that are considered the main drivers behind Iran’s deterrence strategy. The final list of factors preventing Iran from developing nuclear weapons determined through the Delphi method is presented in .

Table 4. Factors preventing Iran’s nuclear deterrence.

C: Dematel

Although the first research question guiding the present study has been responded to in the previous section (), the second question remains unanswered. Aiming to understand which factor has the most impact in preventing Iran from adaptation of nuclear deterrence and determine the causal relationship among identified factors, the DEMATEL technique was employed.

The Decision-Making Trial and Evaluation Laboratory (DEMATEL) method (Fontela and Gabus Citation1976) is an improvised type of structural modeling approach. This technique is a structuring tool used for analyzing and understanding the cause-and-effect relationship among factors under consideration (Tsui, Tzeng, and Wen Citation2015). The knowledge of decision-makers is incorporated in the method to develop a cause-and-effect diagram that shows the influence of each factor on another (Keskin Citation2015).

DEMATEL is one of the techniques of Soft Operational Research (SOR). This technique aims to identify and create awareness about the relationships between the components of phenomena, not to generalize the results in terms of statistical probabilities.

As problem structure methods such as DEMATEL and Delphi rely on the opinions of experts to explain the relationships between factors (Azar, Khosravani, and Jalali Citation2019; Chung-Wei and Gwo-Hshiung Citation2009), data was gathered from a limited number of experts in the specific field of study. It should be noted that the findings obtained through this approach heavily depend on the experts’ perception of the phenomena under investigation. Therefore, if data were collected from different experts, the results could potentially vary. The main strategy of the present study was to distribute the questionnaire among the most qualified available experts who are considered to be the representatives of Iran’s internal debate on deterrence strategy. In March 2022, the DEMATEL questionnaire was distributed to a panel consisting of eighteen experts.

To deploy the DEMATEL technique, a pair-wise questionnaire was designed and distributed it among eighteen experts (including seven military experts and eleven academic experts) in the field of Iran’s nuclear policy. In line with this, the experts demonstrated the impact of individual elements of Iran’s deterrence policy on the other elements and showed the causal relationships among them (see the questionnaire in appendix 4).

The data was analyzed based on the following steps:

Step 1:

In the first step of my DEMATEL analysis, the initial relationship matrix was generated for each expert using EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) . The matrix is a pair-wise comparison generated using the scale (0 – No influence, 1 – Very low influence, 2 – Low influence, 3 – Medium influence, 4 – High influence, 5 – Very high influence), to depict the interrelationship of factors. The notation of xij indicates the degree to which the respondent believes factor i affects factor j. For i = j, the diagonal elements are set to zero.

In total, k matrices are obtained where k represents the number of experts:

The overall direct relationship matrix A is obtained as follows:

The average matrix A (presented in ) can be constructed based on EquationEquation 1(1)

(1) :

Table 5. The average matrix A.

Table 6. The normalized initial direct-relation matrix.

Step 2:

The normalized initial direct-relation matrix is calculated according to the following equation: EquationEquation 2(2)

(2)

Each element in matrix D falls between zero and one.

Step 2 is to calculate the normalized initial direct-relation matrix D, depicted below ():

Each item in this table is the normalized amount of experts’ opinion towards pair-wise comparisons of individual factors. Accordingly, the result would be a number between Zero and One.

Step 3:

In the third step, the total relation matrix calculated and is defined as matrix T:EquationEquation 3(3)

(3)

Where I is the identity matrix ().

Step 4:

The sum of the rows and the sum of columns (presented in ) are calculated as given below and are separately denoted as R and C within the total-relation matrix D: EquationEquation 4(4)

(4)

According to EquationEquations 4(4)

(4) and Equation5

(5)

(5) , each item in the body of matrix is the amount of relationship between related i and j. In line with this, Ri stands for the sum of influences rate of each i, and Cj stands for sum of impactability of each j.

Table 7. The total relation matrix.

Table 8. Calculation of R and C.

Table 9. Causal relations among the factors.

Step 5:

A threshold value to obtain the digraph is set up in step 5. Since matrix T provides information on how one factor affects another, it is necessary for a decision-maker to set up a threshold value to filter out some negligible effects. In doing so, only the effects greater than the threshold value would be chosen and shown in a figure. In this study, the threshold value is set up by computing the average of the elements in matrix T. The digraph can be acquired by mapping the dataset of (r + c, r − c) (Shieh, Wu, and Huang Citation2010).

The threshold value is calculated as 0.1826.

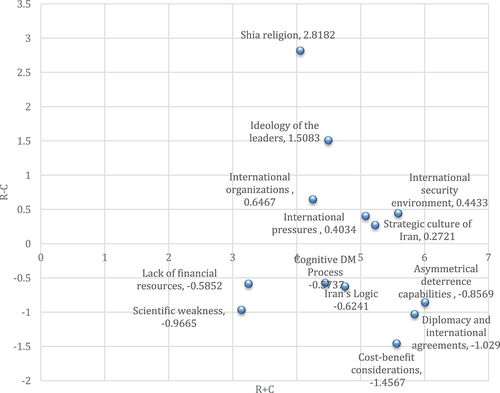

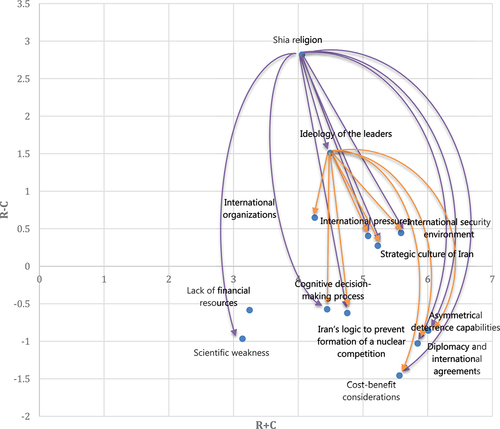

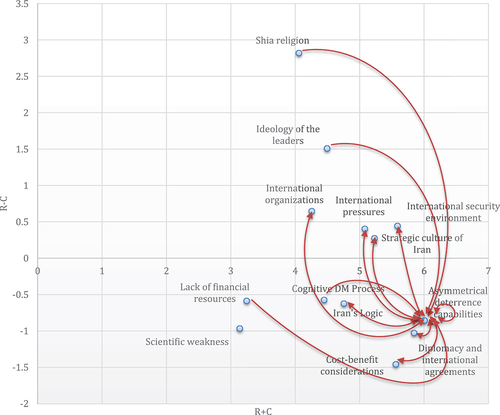

A causal diagram is drawn by mapping the values of (Rij+Cij, Rij−Cij), where the horizontal axis refers to the values of (Rij+Cij) while the vertical axis refers to the values of (Rij−Cij) (Si et al. Citation2018) (see ).

Step 6:

Step 6 (ri + cj) shows the total effects given and received by factor i. (ri + cj) indicates the degree of importance that factor i plays in the entire system. On the contrary, the difference (ri − cj) depicts the net effect that factor i contributes to the system. Specifically, if (ri − cj) is positive, factor i is a net cause, while factor i is a net receiver or result if (ri − cj) is negative ().

While R is the amount of influencing and C is the amount of impactability of each factor, R+C demonstrates the accumulation of effectiveness and impactability of individual deterrence factors, and R-C is the net amount of effectiveness (influentiality). To this end, the biggest amount of R+C is devoted to asymmetric ways of war which has the most powerful network among the factors and in is located in the far right of the horizontal axis. Similarly, the largest amount for R-C is associated with Shia religion, which is at the top of the vertical axis.

Results and Discussion

The results presented in , and provide a response to the two main research questions guiding this study. SLR and Delphi techniques demonstrate thirteen factors preventing Iran from adopting a nuclear deterrence policy and DEMATEL unveils the influence rate of individual factors on Iran’s deterrence policy and shows the causal relation between these factors. The analysis reveals that these factors mutually influence one another. Nevertheless, it is observed that six factors exert greater influence than being influenced, while seven factors are more susceptible to being impacted than being influential.

Table 10. Calculation of R+C and R-C.

According to my research’s findings that are based on the perception of experts, the Shia religion with an influence rate (R-C) of 2.8182 is widely regarded as the primary influential factor inhibiting Iran’s adoption of a nuclear deterrence strategy. The religious factor not only shapes the direction of Iran’s deterrence policy but also significantly impacts nine out of thirteen driving factors behind said policy. Among all factors influencing Iran’s deterrence policy, only international organizations, lack of financial resources, and scientific weaknesses are not influenced by Shia religion.

While rationality is an essential criterion for evaluating a country’s security policy, it is not sufficient on its own. Military behavior cannot be comprehensively understood solely within rational terms, as cultural factors also come into play, such as the influence of the Shia religion in Iran. Thus, if the Shia religion did not form the foundation of Iran’s way of life, there would likely be different interpretations of concepts such as enemy and friend, as well as conventional defense and deterrence strategies.

The ideology of Iranian leaders, particularly Ayatollah Khamenei, Iran’s Commander in Chief of all military forces, with an R-C of 1.5083, holds great significance in determining potential military approaches to deter aggression against the country. Ayatollah Khamenei has consistently emphasized that the possession, development, and use of nuclear weapons are religiously prohibited within Shia doctrine. This specific ideology of Ayatollah Khamenei is one of the primary factors preventing the adoption of a nuclear deterrence strategy by Iran. This finding aligns with the results of my analysis, which affirms the influential role of the ideology of leaders influenced by the Shia religion, impacting nine other factors, albeit to a lesser degree than the Shia religion itself. Consequently, it is ranked as the second most influential factor hindering Iran’s adoption of a nuclear deterrence strategy.

Excluding the “role of Shia jurisprudence” and the “ideology of leaders” from the equation would yield different and inaccurate outcomes. Without these two factors, Iran could have maintained its status as a key ally of the United States in West Asia, eliminating any room for hostility with the United States and Israel. Presently, Iran possesses the potential capability to enrich to levels above 90%. Without the religious and ideological constraints, Iran could have developed its own nuclear deterrence capabilities, similar to neighboring Pakistan. Hence, I assert that the role of the Shia religion in Iran’s military behavior holds great importance and should not be underestimated. The findings of the current study, therefore, prove the arguments of Taremi (Citation2005), Nowrouzani (Citation2009), Guzansky and Golov (Citation2015), and Eslami and Vieira (Citation2022). visually demonstrates the causal relationship between the Shia religion and the ideology of leaders and the various other factors impeding Iran from embracing a nuclear deterrence policy.

In contrast to the aforementioned domestic factors, the subsequent trio of factors impeding Iran from adopting a nuclear deterrence strategy are of an international nature. International organizations and institutions such as the United Nations and International Atomic Energy Agency with an R-C of 0.6467, alongside international pressures like economic sanctions and political isolations with an R-C of 0.4034, as well as the international security environment with an R-C of 0.4433, exert influence on Iran’s deterrence policy and preclude the adoption of a nuclear deterrence strategy. Although these three factors have a relatively equal impact on Iran’s deterrence policy, their overall influence remains modest.

Based on the outcome of this analysis, Iran’s abstaining from nuclear warheads may be attributed more to internal factors such as the Shia religion and the ideological stance of its leaders rather than the imposition of comprehensive sanctions or the oversight of international organizations. Accordingly, the means for managing Iran’s nuclear ambitions should be examined within the framework of the Shia religion and the ideological orientation of its leaders. To this end, the present study disproves the research findings of Sagan et al. (Citation2007), Parasiliti (Citation2009), Dobbins (Citation2011), and Drezner (Citation2022). It is worth noting that, despite the relatively low level of influence of these three factors (international organizations, international pressures, and international security environment), they are interconnected with a growing number of factors and are subject to influence from a significant array of them. Consequently, their significance in shaping Iran’s deterrence policy persists.

Iran’s strategic culture with an R-C of 0.2721 is a significant determinant in the country’s reluctance to adopt a nuclear deterrence strategy. Strategic culture is deeply rooted in historical experiences such as the Iran-Iraq war, the geographical location of Iran in an unstable region, diverse ethnicities and languages that contribute to the national identity, and the tenets of the Shia religion. Deterrence, alongside self-sufficiency and a distrust of global powers, is a crucial principle within Iran’s strategic culture. Viewing strategic culture as a set of norms and beliefs regarding the use of force, it is evident that strategic culture plays a vital role in shaping Iran’s approach to deterrence. This analysis reveals that Iran’s strategic culture both influences and is influenced by a range of factors, with seven factors found to prevent the country from adopting a nuclear deterrence strategy, which is in line with the research of Cain (Citation2002), Knepper (Citation2008), and Gerami (Citation2018), and proves their arguments.

The next seven factors preventing Iran from adopting a nuclear deterrence strategy have a low R-C and high R+C (impactability). Scientific weaknesses with a R-C of −0.9665 and R+C of 3.1393 and lack of financial resources with a R-C of −0.5852 and R+C of 3.2492 are good instances for this claim. As an isolated country, Iran is in hardship to access the scientific achievements of different countries in the field of nuclear sciences. Accordingly, most of Iran’s nuclear progress including the development of advanced centrifuges and increasing the enrichment level has been made by trial and error, which is time consuming, dangerous, and expensive. Moreover, Iran has problems with securing the national budget due to international sanctions. This financial problem limits Iran’s investment in its nuclear program.

Iran’s cognitive decision-making process with a R-C of −0.5737 and R+C of 4.4475 and its logic to prevent the formation of nuclear competition in the region with a R-C of −0.6241 and R+C of 4.7577 as well as cost and benefit calculations with a R-C of −1.4567 and R+C of 5.5635 are three other factors preventing Iran from adopting a nuclear deterrence strategy. They are influenced by an increased number of factors, especially Shia religion, international security environment, international organizations, and Iran’s strategic culture. Accordingly, the benefits of adopting a nuclear deterrence strategy are considered to be less than its costs for Iran as a Shia regime that is located in an insecure region.

Diplomacy and international agreements with a R-C of −1.029 and R+C of 5.8452, such as the NPT and the JCPOA, are also among factors affecting Iran’s nuclear policy and deterring the country from pursuing a nuclear deterrence strategy. While the prevailing viewpoint among Western scholars, such as Sagan et al. (Citation2007), Parasiliti (Citation2009), Dobbins (Citation2011), Kroenig (Citation2018), Maher (Citation2020), Arena (Citation2021) and Drezner (Citation2022), emphasizes the significance of diplomatic engagement and international cooperation in averting Iran’s development of nuclear warheads, the analysis indicates that the impact of diplomacy on Iran’s deterrence policy is relatively limited. This finding supports the notion that Iran has shown reluctance to negotiate over its defense capabilities.

Furthermore, asymmetric deterrence capabilities with a R-C of −0.8569 and R+C of 6.0094 assume a significant role in deterring Iran from embracing a nuclear deterrence strategy (see ). Essentially, by relying on asymmetric methods of warfare, Iran perceives no necessity in developing a nuclear deterrence strategy. In this vein, this research proves Olson (Citation2016), Freedman (Citation2017), Ajili and Rouhi (Citation2019), Ahmadian and Mohseni (Citation2019, Citation2021), Eslami and Vieira (Citation2020, Citation2022), Akbarzadeh et al. (Citation2023) and all contributions pointing at a close connection between Iran’s deterrence strategy and its asymmetric ways of war and forward defense doctrine. This analysis demonstrates that the influence of asymmetric deterrence capabilities is intertwined with various factors, rendering it the most intricate causal relationship network with other factors. Consequently, asymmetric ways of war are seen as viable alternatives to a nuclear deterrence strategy. This approach enables Iran to safeguard the country’s interests while upholding the tenets of Shia religion and the leaders’ ideological principles. Moreover, in the sphere of international security, asymmetric deterrence capabilities are more widely accepted and less subject to criticism than a nuclear deterrence strategy due to its adherence to international treaties and agreements and absence of sanctions. Ultimately, asymmetric deterrence capabilities help prevent the emergence of nuclear competition in the region and aligns with the cost and benefit calculations of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Conclusion

Following the 2003 US invasion of Iraq, Iran’s official and semi-official documents have placed significant emphasis on the notion of “deterrence” (bazdarandegi). The advancement of Iran’s ballistic missile program, coupled with its increasing capabilities in uranium enrichment, increases the perception that Iran is actively pursuing the development of nuclear weapons. In 2021, Iran’s Atomic Energy Organization (sazmane energie atomi) declared that the country was capable of enriching uranium up to the level of 90%. Iranian leadership consistently asserts, however, that the ballistic missile program serves as a substitute for nuclear weapons rather than a means of delivering nuclear warheads. In this vein, Iran’s deterrence approach remained non-nuclear, centered primarily on the insecurity of its borders and the threat of the United States and Israel, without being supplanted by a deterrence strategy with nuclear weapons as its cornerstone.

Aiming to identify the factors inhibiting Iran’s development of a nuclear deterrence strategy and to ascertain the causal relations among these factors, this study employed a novel analytical approach integrating SLR, Delphi, and DEMATEL techniques. The findings of this analysis revealed a comprehensive inventory of thirteen internal and international factors influencing Iran’s deterrence strategy (). Notably, these factors not only impact Iran’s deterrence policy but also exhibit interconnected causal relationships, collectively impeding Iran’s pursuit of nuclear bombs. An in-depth examination of the thirteen factors obstructing Iran’s advancement in nuclear military capabilities reveals that ten of these factors possess broader applicability beyond Iran and are pertinent to other nations. Elements such as international organizations, diplomacy, international security environment, international economic pressure, lack of financial resources, scientific weaknesses, cost-benefit calculations, cognitive decision-making processes, and logic/aspiration to prevent nuclear competition are germane to other countries as well. Hence, it prompts the inquiry as to why Pakistan, a Muslim nation situated in a comparable “geography of threat”, opted for nuclear deterrence while Iran did not. Addressing this query necessitates an exploration of factors exclusive to Iran and its distinct governance framework.

This analysis underscores the paramount influence of Shia religious beliefs and the ideological stance of Iranian leaders in obstructing the adoption of a nuclear deterrence strategy by Iran. Moreover, the centrality of Shia religion in shaping the ideological orientation of Iranian leadership underscores the unique role of these two distinctive factors within the Iranian political framework, steering Iran towards eschewing nuclear deterrence strategies in favor of asymmetric ways of war. Consequently, the religious prohibition within Shia doctrine against the possession of weapons of mass destruction stands as the primary impetus driving Iran’s significant investments in ballistic missile programs. Leveraging Shia religious tenets, Ayatollah Khamenei, in his capacity as the Valie Faghih, regards ballistic missiles not as a delivery mechanism for nuclear warheads, but as a viable substitute for nuclear armaments. The delegation of the deterrence mission to ballistic missiles has led to the development of one of the largest and most diverse ballistic missiles arsenal by Iran.

This study presents a policy recommendation for world leaders who have sought to deter Iran from acquiring nuclear capabilities through regime change initiatives. Taking into consideration the implications that altering the regime in Iran may yield unintended consequences for its nuclear program, the most feasible approach to influence Iran’s nuclear pursuits appears to be through diplomatic engagement and negotiation with the existing leadership of the Islamic Republic of Iran that is not interested in the development of nuclear bombs due to Shia religious constraints.

In conclusion, this study lays the foundation for two potential avenues of future research. Firstly, an exploration of the influence of domestic factors, including religion, leadership ideologies, and strategic culture on the deterrence policies of distinct nuclear nations could be pursued using a systematic research framework akin to the one employed in this study. Secondly, the methodological approach introduced in this study can be used to scrutinize and elucidate the underlying motivations driving the nuclear ambitions of individual countries.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mohammad Eslami

Mohammad Eslami is an Assistant Professor of International Relations at the University of Minho in Portugal and an Integrated Member of the Research Center for Political Science (CICP). He was also a research fellow at the Arms Control Negotiation Academy of the Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies at Harvard University. His research interests primarily relate to International Security, Arms control, Nuclear Proliferation, and Middle East Studies. He has published in International Affairs, Third World Quarterly, Journal for Peace and Nuclear Disarmament, Journal of Asian Security, Small Wars and Insurgencies and Spanish Journal of Political Science and wrote book chapters to several edited volumes published by Springer and Palgrave Macmillan, among others. Mohammad’s most recent book The Arms Race in the Middle East, was published by Springer in 2023.

Notes

1 I would like to express my deep gratitude to Program-specific Associate Professor Hibiki Yamaguchi, the Journal’s editor, as well as Professor Alena Vieira and the two anonymous reviewers. Their insightful comments played a crucial role in enhancing the quality of this manuscript.

2 The genesis of deterrence theorizing can be traced back to the imperative to address the advent of the atomic bomb. Subsequently, a second wave emerged during the 1950s and 1960s wherein game theory was incorporated to shape the prevailing understanding of nuclear strategy (Knopf Citation2009; Nye Citation2020; Ven Bruusgaard Citation2016). The third wave, which materialized in the 1970s, used statistical and case-study methods to empirically test deterrence theory, predominantly in relation to instances of conventional deterrence. This investigation draws on the advancements made by the third generation of deterrence studies (Knopf Citation2010; Lupovici Citation2016; Williams Citation2021).

References

- Adib-Moghaddam, A. 2005. “Islamic Utopian Romanticism and the Foreign Policy Culture of Iran.” Critique: Critical Middle Eastern Studies 14 (3): 265–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/10669920500280623.

- Adib-Moghaddam, A. 2006. The International Politics of the Persian Gulf: A Cultural Genealogy. London, UK: Routledge.

- Ahmadian, H., and P. Mohseni. 2019. “Iran’s Syria Strategy: The Evolution of Deterrence.” International Affairs 95 (2): 341–364. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiy271.

- Ahmadian, H., and P. Mohseni. 2021. “From Detente to Containment: The Emergence of Iran’s New Saudi Strategy.” International Affairs 97 (3): 779–799. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiab014.

- Ajili, H., and M. Rouhi. 2019. “Iran’s Military Strategy.” Survival 61 (6): 139–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2019.1688575.

- Akbarzadeh, S., W. Gourlay, and A. Ehteshami. 2023. “Iranian Proxies in the Syrian Conflict: Tehran’s ‘Forward-defence’in Action.” Journal of Strategic Studies 46 (3): 683–706. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2021.2023014.

- Alcaro, R. 2021. “Europe’s Defence of the Iran Nuclear Deal: Less Than a Success, More Than a Failure.” The International Spectator 56 (1): 55–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/03932729.2021.1876861.

- Aminian, B., and S. Zamiri-Jirsarai. 2016. “The Impact of Missile Technology Control Regime on National Security and the Deterrence of Islamic Republic of Iran.” Security Horizons Quarterly 9 (32): 71–96. ( Persian source).

- Ansari Fard, M., and A. M. Haji-Yousefi. 2023. “Challenges of Iran Deterrence Strategy in the Middle East: From Alliance to Gray Zone Politics.” Geopolitics Quarterly 19 (69): 96–130.

- Arena, M. D. C. P. 2021. “Narratives Modes and Foreign Policy Change: The Debate on the 2015 Iran Nuclear Deal.” Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional 64 (1): e007. https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-7329202100107.

- Azar, A., F. Khosravani, and R. Jalali. 2019. Soft Operational Research: Problem Structuring Methods. Tehran: Industrial Management.

- Barzegar, K. 2014. “Iran–US Relations in the Light of the Nuclear Negotiations.” The International Spectator 49 (3): 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/03932729.2014.953311.

- Bench, S., and T. Day. 2010. “The User Experience of Critical Care Discharge: A Meta-Synthesis of Qualitative Research.” International Journal of Nursing Studies 47 (4): 487–499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.11.013.

- Blight, J. G., H. Banai, M. Byrne, and J. Tirman. 2012. Becoming Enemies: US-Iran Relations and the Iran-Iraq War, 1979–1988. Maryland, The US: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Byman, D. 2018. “Confronting Iran.” Survival 60 (1): 107–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2018.1427368.

- Cain, A. C. 2002. Iran’s Strategic Culture and Weapons of Mass Destruction. Alabama, The US: Air War College, Air University.

- Chubin, S. 2009. “Extended deterrence and Iran.” Naval postgraduate school Monterey ca center on contemporary conflict.

- Chubin, S. 2014. “Is Iran a Military Threat?” Survival 56 (2): 65–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2014.901733.

- Chung-Wei, L., and T. Gwo-Hshiung. 2009. Identification of a Threshold Value for the DEMATEL Method: Using the Maximum Mean de-Entropy Algorithm. In International Conference on Multiple Criteria Decision Making (pp. 789–796). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.

- Connell, M. 2010. Iran’s Military Doctrine, the Iran Primer. RB Wright. Washington: US Institute of Peace.

- Czulda, R. 2016. “The Defensive Dimension of iran’s miliTary DocTrine: How Would They Fight.” Middle East Policy 23 (1): 92–109. https://doi.org/10.1111/mepo.12176.

- Dalton, M. G. 2017. “How Iran’s Hybrid-War Tactics Help and Hurt It.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 73 (5): 312–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.2017.1362904.

- Denyer, D., and D. Tranfield. 2009. “Producing a Systematic Review.” In The Sage Handbook of Organizational Research Methods, edited by D. A. Buchanan and A. Bryman, 671–689. Washington DC, The US: Sage Publications Ltd.

- Dobbins, J. 2011. “Coping with a Nuclearising Iran.” Survival 53 (6): 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2011.636513.

- Dolatabadi, A.2013. “Deterrence and Iran’s Military Strategy.” Defese Policy 85 (22): 3–25. Persian Source.

- Dolatabadi, A. B. 2017. “The Role of Deterrence in Iran’s Military Strategy.” Journal of Defense Policy 22 (85): 1–30. Persian source.

- Drezner, D. W. 2022. “How Not to Sanction.” International Affairs 98 (5): 1533–1552. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiac065.

- Duus, H. P. 2011. “Deterrence and a Nuclear-Armed Iran.” Comparative Strategy 30 (2): 134–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/01495933.2011.561731.

- Edelman, E. S., A. F. Krepinevich, and E. B. Montgomery. 2011. “The Dangers of a Nuclear Iran: The Limits of Containment.” Foreign Affairs 66–81. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25800382.

- Eslami, M. 2021. “Photoshopped Missiles and Fallen Iran’s Ballistic Missile Program and Its Foreign and Security Policy Towards the United States Under the Trump Administration.” Revista Española de Ciencia Política 55:37–62. https://doi.org/10.21308/recp.55.02.

- Eslami, M. 2022. “Iran’s Drone Supply to Russia and Changing Dynamics of the Ukraine War.” Journal for Peace & Nuclear Disarmament 5 (2): 507–518. https://doi.org/10.1080/25751654.2022.2149077.

- Eslami, M., and I. Al-Marashi. 2023. “The Cold War in the Middle East: Iranian Foreign Policy, Regional Axes, and Warfare by Proxy.” In The Arms Race in the Middle East: Contemporary Security Dynamics, edited by Eslami and Vieira, 111–123. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Eslami, M., M. Bazrafshan, M. Sedaghat. 2021. “Shia Geopolitics or Religious Tourism? Political Convergence of Iran and Iraq in the Light of Arbaeen Pilgrimage.” In The Geopolitics of Iran, edited by F. Leandro, 363–385. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Eslami, M., and S. Sotudehfar. 2021. “Iran–UAE Relations and Disputes Over the Sovereignty of Abu Musa and Tunbs.” In The Geopolitics of Iran, edited by F. Leandro, 343–362. Sngapore: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Eslami, M., and A. Vieira. 2022. “Shi’a Principles and Iran’s Strategic Culture Towards Ballistic Missile Deployment.” International Affairs 98 (2): 675–688. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiab234.

- Eslami, M., and A. V. G. Vieira. 2020. “Iran’s Strategic Culture: The ‘Revolutionary’ and ‘Moderation’- Narratives on the Ballistic Missile Programme.” Third World Quarterly 42 (2): 312–328. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2020.1813562.

- Eslami, M., and A. V. G. Vieira. 2023. “Introducing the Arms Race in the Middle East in the Twenty First Century: A “Powder Keg” in the Digital Era?” In The Arms Race in the Middle East: Contemporary Security Dynamics, edited by Eslami and Vieira, 3–13. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Evron, Y. 2008. “An Israel-Iran Balance of Nuclear Deterrence: Seeds of Instability.” Israel and a Nuclear Iran: Implications for Arms Control, Deterrence, and Defense, Tel Aviv: Institute for National Security Studies, Memorandum 94:47–63. http://www.jstor.com/stable/resrep08946.6.

- Fontela, E., and A. Gabus. 1976. The DEMATEL Observer. Geneva, Switzerland: Battelle Geneva Research Center.

- Freedman, G. 2017. “Iranian Approach to Deterrence: Theory and Practice.” Comparative Strategy 36 (5): 400–412. https://doi.org/10.1080/01495933.2017.1379831.

- Gerami, N.2018. “Iran’s Strategic Culture: Implications for Nuclear Policy.” In Crossing Nuclear Thresholds. Initiatives in Strategic Studies: Issues and Policies, edited by J. Johnson, K. Kartchner, and M. Maines, 61–108. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-72670-0_3.

- Ghamari-Tabrizi, B. 2014. “The Divine, the People, and the Faqih: On Khomeini’s Theory of Sovereignty.” In A Critical Introduction to Khomeini, edited by Addib-Moghaddam, 211–239. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Ghanbari Jahromi, M. H. 2015. “The Process of Designing the Comprehensive Deterrence Doctrine of IR Iran in the country’s Outlook for Next Twenty Years.” Defence Studies 13 (2): 1–38. Persian source.

- Guldimann, T. 2023. ”The Iranian Nuclear Impasse.” Survival 49 (3): 169–178.

- Guzansky, Y., and A. Golov. 2015. “The Rational Limitations of a Nonconventional Deterrence Regime: The Iranian Case.” Comparative Strategy 34 (2): 169–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/01495933.2015.1017349.

- Hicks, K. H., and M. G. Dalton, Eds. 2017. Deterring Iran After the Nuclear Deal. Washington DC, The US: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Johnson, R. B., A. J. Onwuegbuzie, and L. A. Turner. 2007. “Toward a Definition of Mixed Methods Research.” Journal of Mixed Methods Research 1 (2): 112–133. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689806298224.

- Johnston, A. I. 2016. “Is Chinese Nationalism Rising? Evidence from Beijing.” International Security 41 (3): 7–43. https://doi.org/10.1162/ISEC_a_00265.

- Kaltenthaler, K. C., D. M. Silverman, and M. M. Dagher. 2020. “Nationalism, Threat, and Support for External Intervention: Evidence from Iraq.” Security Studies 29 (3): 549–573. https://doi.org/10.1080/09636412.2020.1763451.

- Katzman, K., K. J. McInnis, and C. Thomas. 2020. “US-Iran Conflict and Implications for US Policy.” Congressional Research Service 2–8.

- Kaye, D. D., and F. M. Wehrey. 2023. “A Nuclear Iran: The Reactions of Neighbours.” Survival 49 (2): 111–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/00396330701437777.

- Kazemzadeh, M. 2020. Iran’s Foreign Policy: Elite Factionalism, Ideology, the Nuclear Weapons Program, and the United States. London, UK: Routledge.

- Keskin, G. A. 2015. “Using Integrated Fuzzy DEMATEL and Fuzzy C: Means Algorithm for Supplier Evaluation and Selection.” International Journal of Production Research 53 (12): 3586–3602. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2014.980461.

- Knepper, J. 2008. “Nuclear Weapons and Iranian Strategic Culture.” Comparative Strategy 27 (5): 451–468. https://doi.org/10.1080/01495930802430080.

- Knopf, J. W. 2009 2. “Three Items in One: Deterrence as Concept, Research Program, and Political Issue.” In Complex Deterrence, edited by Paul, 31–57. Chicago, The US: University of Chicago Press.

- Knopf, J. W. 2010. “The Fourth Wave in Deterrence Research.” Contemporary Security Policy 31 (1): 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/13523261003640819.

- Kroenig, M. 2018. “The Return to the Pressure Track: The Trump Administration and the Iran Nuclear Deal.” Diplomacy & Statecraft 29 (1): 94–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/09592296.2017.1420529.

- Liberman, P., and L. Skitka. 2019. “Vicarious Retribution in US Public Support for War Against Iraq.” Security Studies 28 (2): 189–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/09636412.2019.1551568.

- Lupovici, A. 2016. The Power of Deterrence. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Macdonald, J., and J. Schneider. 2019. “Battlefield Responses to New Technologies: Views from the Ground on Unmanned Aircraft.” Security Studies 28 (2): 216–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/09636412.2019.1551565.

- Maher, N. 2020. “Balancing Deterrence: Iran-Israel Relations in a Turbulent Middle East.” Review of Economics and Political Science, ( ahead-of-print) 8 (3). https://doi.org/10.1108/REPS-06-2019-0085.

- Mandelbaum, M. 2015. “How to Prevent an Iranian Bomb.” Foreign Affairs 94 (19): 19.

- Mukherjee, N., J. Huge, W. J. Sutherland, J. McNeill, M. Van Opstal, F. Dahdouh‐Guebas, N. Koedam, and B. Anderson. 2015. “The Delphi technique in ecology and biological conservation: applications and guidelines.” Methods in Ecology and Evolution 6 (9): 1097–1109. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12387.

- Murray, D. 2009. US Foreign Policy and Iran: American-Iranian Relations Since the Islamic Revolution. London, UK: Routledge.

- Musa, H. D., M. R. Yacob, and A. M. Abdullah. 2019. “Delphi Exploration of Subjective Well-Being Indicators for Strategic Urban Planning Towards Sustainable Development in Malaysia.” Journal of Urban Management 8 (1): 28–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jum.2018.08.001.

- Nowrouzani, S. 2009. “Iran’s Military Culture and Deterring the US Aggression.” Military Sciences 6 (13): 27–50. Persian source.

- Nye, J. S. 2020. “The Long-Term Future of Deterrence.” In The Logic of Nuclear Terror, edited by Kolkowicz, 233–250. London, UK: Routledge.

- Olson, E. A. 2016. “Iran’s Path Dependent Military Doctrine.” Strategic Studies Quarterly 10 (2): 63–93.

- Papageorgiou, M., M. Eslami, and P. A. B. Duarte. 2023. “A ‘Soft’balancing Ménage à Trois? China, Iran and Russia Strategic Triangle Vis-à-Vis US Hegemony.” Journal of Asian Security and International Affairs 10 (1): 65–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/23477970231152008.

- Parasiliti, A. 2009. “Iran: diplomacy and deterrence.” Survival 51 (5): 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00396330903309824.

- Paul, J., W. M. Lim, A. O’Cass, A. W. Hao, and S. Bresciani. 2021. “Scientific Procedures and Rationales for Systematic Literature Reviews (SPAR‐4‐SLR).” International Journal of Consumer Studies 45 (4): O1–O16. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12695.

- Quek, K., and A. I. Johnston. 2017. “Can China Back Down? Crisis de-Escalation in the Shadow of Popular Opposition.” International Security 42 (3): 7–36. https://doi.org/10.1162/ISEC_a_00303.

- Sablatzky, T. 2022. “The Delphi method.” Hypothesis: Research Journal for Health Information Professionals 34 (1). https://doi.org/10.18060/26224.

- Sagan, S. D., and B. A. Valentino. 2017. “Revisiting Hiroshima in Iran: What Americans Really Think About Using Nuclear Weapons and Killing Noncombatants.” International Security 42 (1): 41–79. https://doi.org/10.1162/ISEC_a_00284.

- Sagan, S., K. Waltz, and R. K. Betts. 2007. “A Nuclear Iran: Promoting Stability or Courting Disaster?” Journal of International Affairs 60 (2): 135–150.

- Shannon, K. J. 2019. “Iran-US Relations.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.013.501.

- Shieh, J. I., H. H. Wu, and K. K. Huang. 2010. “A DEMATEL Method in Identifying Key Success Factors of Hospital Service Quality.” Knowledge-Based Systems 23 (3): 277–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2010.01.013.

- Si, S. L., X. Y. You, H. C. Liu, and P. Zhang. 2018. “DEMATEL Technique: A Systematic Review of the State-Of-The-Art Literature on Methodologies and Applications.” Mathematical Problems in Engineering 2018:1–33. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/3696457.

- Tabatabai, A. 2019. Iran’s National Security Debate: Implications for Future U.S.-Iran Negotiations. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. https://doi.org/10.7249/pe344.

- Tabatabai, A. M., and A. T. Samuel. 2017. “What the Iran-Iraq War Tells Us About the Future of the Iran Nuclear Deal.” International Security 42 (1): 152–185. https://doi.org/10.1162/ISEC_a_00286.

- Takeyh, R. 2003. “Iran at a Crossroads.” The Middle East Journal 57 (1): 42–56.

- Taremi, K. 2005. “Beyond the Axis of Evil: Ballistic Missiles in Iran’s Military Thinking.” Security Dialogue 36 (1): 93–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010605051926.

- Tsui, C. W., G. H. Tzeng, and U. P. Wen. 2015. “A Hybrid MCDM Approach for Improving the Performance of Green Suppliers in the TFT-LCD Industry.” International Journal of Production Research 53 (21): 6436–6454. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2014.935829.

- Vatanka, A. 2004. “Analysis: Iranian Military Rhetoric Reflects Outside Pressures.” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, November 1, 2004.

- Ven Bruusgaard, K. 2016. “Russian strategic deterrence.” Survival 58 (4): 7–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2016.1207945.

- Vieira, A. 2023. “Arms Sales as an Instrument of Russia’s Foreign Policy and the Shifting Security Dynamics of the Middle East.” In In The Arms Race in the Middle East: Contemporary Security Dynamics, edited by M. Eslami and A. Vieira, 241–256. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Waltz, K. 2012. “Why Iran Should Get the Bomb.” Foreign Affairs 91 (4): 2–5.

- Ward, S. R. 2005. “The Continuing Evolution of Iran’s Military Doctrine.” The Middle East Journal 59 (4): 559–576. https://doi.org/10.3751/59.4.12.

- Williams, P. 2021. “Deterrence.” In Contemporary Strategy, edited by Baylis, 67–88. London, UK: Routledge.

- Yossef, A. 2019. “Upgrading Iran’s Military Doctrine: An Offensive “Forward Defense”.” Middle East Institute 10.

Appendix 1.

SLR of Iran nuclear deterrence strategy

Appendix 2.

Iran nuclear deterrence factors based on their frequency in papers (SLR)

Appendix 3.

Delphi primary questionnaire

Open Question

In your mind, what are other factors that has any impact on the deterrence of Iran from approaching to nuclear weapons?