Abstract

Background

Few studies have assessed the role of legal protection and institutional trust as structural determinants of health among trans people.

Aim

This study investigated the responses of a nationwide survey of trans people in Aotearoa New Zealand to examine the interplay among perceived legal protection, trust toward institutions, and psychological distress.

Method

Data were employed from the 2018 Counting Ourselves survey (n = 863; Mage = 30.3). We conducted chi-square analyses to identify the extent of differences for institutional trust between trans participants and the Aotearoa/New Zealand general populations. Correlation and mediation analyses were utilised to determine whether structural determinants were associated with lower psychological distress levels.

Findings

Our results revealed that over a quarter (26%) of trans participants did not feel New Zealand law protects against discrimination for being trans or non-binary. Trans participants reported heightened levels of distrust compared to the general populations across media (65% vs 39%; RR= 1.66) parliament (52% vs 25%; RR = 2.07), police (49% vs 7%; RR = 7.48), and courts (48% vs 13%; RR = 3.84). Significant demographic differences in institutional trust levels were observed, with younger individuals, trans men, non-binary people assigned female at birth, or people with a disability status reporting lower trust toward different institutions. Perceived legal protection and confidence were correlated with lower psychological distress levels, and institutional trust partially mediated this association.

Conclusions

Findings from this study demonstrate the urgency for government agencies to consult appropriately and work collaboratively with trans communities to identify current gaps in laws and policies that protect the human rights of trans people. Trans-inclusive policies have the potential to elevate community trust toward institutions and improve the meaningful participation of trans people and address inequities.

Introduction

Transgender and non-binary peopleFootnote1 (hereafter referred to using the umbrella term ‘trans’) often experience significantly higher rates of mental ill-health relative to their cisgender counterparts (James et al., Citation2016; Su et al., Citation2016; Treharne et al., Citation2020). The seminal 2015 US Transgender Survey found that there was an eightfold increase in the manifestation of serious psychological distress among trans respondents compared to general United States populations (39% vs 5%; James et al., Citation2016). Further research examining modifiable risk and protective factors are imperative for mitigating the magnitude of mental ill-health and related harms among trans people. This article focuses on the role of legal protection and trust in public institutions as a means to address these inequities.

There is strong consensus that mental ill-health disparities among trans people are attributable to gender minority stress (additional social stressors that trans people encounter; Testa et al., Citation2015). However, some scholars (Riggs et al., Citation2015; Riggs & Treharne, Citation2017; Tan et al., Citation2020) have emphasized the need for more consideration of the social origins of gender minority stress including how cisgenderism exposes transgender people to enacted stigma experiences. Cisgenderism is a form of prejudice that denies, ignores, and marginalizes genders other than those that adhere to a fixed binary based on sex assigned at birth thereby disproportionately exposing trans people to mental ill-health and related harms (Riggs et al., Citation2015; Tan et al., Citation2020). Notwithstanding this, increasingly strengths-based research frames the gender minority stress model as dynamic in that mental ill-health is the consequence of distal factors such as interpersonal and structural discrimination and victimization and proximal factors such as internalized cisgenderism (Tan et al., Citation2021; Testa et al., Citation2015; Treharne et al., Citation2020). Mediators and moderators of the relationship between gender minority stress and mental ill-health thus present promising prevention targets for public health practitioners (Dolotina & Turban, Citation2022).

Trans people’s perceptions of institutions

At present, international research on gender minority stress experienced by trans people predominantly focuses on interpersonal levels or the enacted form of cisgenderist prejudices directed toward individuals (e.g. family rejection, verbal harassment, physical assault) (Hughto et al., Citation2015; Testa et al., Citation2015). Comparatively, less research exists on the manifestation of cisgenderism at structural levels (including societal norms, governmental laws, and institutional policies) where authorities act to influence the distribution of resources and opportunities for trans people (Hughto et al., Citation2015). Examining structural interventions provides insights into how public agencies articulate and execute their commitments to resolve the high level of discrimination and health inequities that trans people experience (Hughto et al., Citation2015; Human Rights Commission, Citation2008; Riggs et al., Citation2015). Such a focus also reveals whether and to what extent equity initiatives focus on trans people, and how trans identities are accepted in public spheres. This level of structural recognition may influence trans individuals’ trust and impressions of public institutions.

In this article, we draw on the largest community-based survey of trans people in Aotearoa/New Zealand (Veale et al., Citation2019) to provide baseline data on the degree of trust among trans people toward key institutions that serve as structural determinants of health. Here, we define structural determinants as mechanisms that generate social stratification with an influence on people’s socioeconomic position and ability to access social determinants of health (e.g. healthcare and employment opportunities) free from stigma (Cascalheira et al., Citation2022; Scheim et al., Citation2020). Examples of these institutions include Police, courts and parliament that are responsible for enforcing legal protections, and media through its portrayals of transgender people and their rights (Human Rights Commission, Citation2008, 2020). While a considerable body of literature has examined the preventative utility of promoting trust among trans people to improve the accessibility and quality of health care services (Baguso et al., Citation2022; Ker et al., Citation2022), there is a dearth of research investigating the role played by trust in other institutions outside the health sector. The lacuna in empirical evidence on legal protection as a structural determinant, and institutional trust as a modifiable mediator for mental ill-health, has prompted us to examine the interplay among these factors.

There are few isolated pockets of research on how mental health experiences of trans people are affected through systemic policies implemented by decision-makers outside the health sector, and by trans people’s engagement with relevant institutions. The explicit inclusion of nondiscriminatory practices toward trans people in national legislations have been found to not only prevent this population from facing discrimination, with mental health improvements linked to the additional recognition and legitimacy of trans people’s lived experiences (Gleason et al., Citation2016; Hughto et al., Citation2022; Miller-Jacobs et al., Citation2023; Rabasco & Andover, Citation2020). For instance, a study in the United States (Gleason et al., Citation2016) found that trans people residing in states where trans people were protected under nondiscrimination laws had lower rates of suicide attempts than those who did not. Another study in Northeastern United States of 580 trans participants (Hughto et al., Citation2022) reported that almost half (48%) were concerned that their state would pass policies that undermine trans rights. Participants who expressed fear that anti-trans policies would be enacted were significantly more likely to report greater odds of depression and anxiety (Hughto et al., Citation2022). Conversely, other inclusive legislative changes such as allowing trans people to more easily amend their gender marker and name on identity documents have been linked to reduced levels of psychological distress and suicidality (Scheim et al., Citation2020; Tan et al., Citation2022).

The relationships between trans communities and the Police as an institution tend to be fraught (Ashley, Citation2018; Human Rights Commission, Citation2008; Serpe & Nadal, Citation2017). Studies have shown trans people have less favorable perceptions toward the Police and are less likely to report comfort with interacting with police (Serpe & Nadal, Citation2017) due to their experiences of witnessing or encountering increased targeting such as police searches and harassment (DeVylder et al., Citation2018; Human Rights Commission, Citation2008). Exposure to police violence, including the domains of physical, sexual, psychological, and neglect, has been identified as a risk factor for trans people in reporting suicidal ideation and attempts (DeVylder et al., Citation2018). While a comprehensive historic overview of the criminalization of gender and sexuality diversity is beyond the remit of this article, trans people’s contemporary perceptions of and interactions with the Police have arguably been informed by the historic persecution of queer and trans people throughout the twentieth century (see Russell, Citation2020). These historic oppressions and ongoing injustices have catalyzed much of the resistance against the structural transphobia that persists in legal institutions in Aotearoa today (e.g. Human Rights Commission, Citation2008; Murphy, Citation2018).

Media representations of gender diversity can impact on trans people’s wellbeing. A United States study of 545 trans adults found almost all (98%) had come across negative trans-related media across a range of platforms such as television messages, newspapers, magazine articles and advertisements (Hughto et al., Citation2020). The same study reported a correlation between more frequent exposure to negative media depictions of trans people and heightened levels of psychological distress (Hughto et al., Citation2020). Negative media representation of trans people can jeopardize trans young people’s access to gender-affirming care (Indremo et al., Citation2022), which has been identified as a social determinant of health (Swan et al., Citation2023). A study in Sweden (Indremo et al., Citation2022) found lower referral numbers to specialist pediatric gender clinics following the airing of anti-trans documentaries, suggesting that such negative media coverage may lead to parents and health professionals blocking access to gender-affirming care.

The current study

The aim of this paper is threefold. First, we assess the extent of differences in institutional trust between trans participants in the 2018 Counting Ourselves survey and general population estimates from the 2018 New Zealand General Social Survey (NZGSS; Statistics New Zealand, Citation2019). The NZGSS is a survey conducted by Statistics New Zealand, the official data agency of Aotearoa, that utilizes stratified random sampling methods to produce statistics on social wellbeing based on a nationally representative sample. The 2018 NZGSS can only provide population estimates as it did not ask questions about gender beyond a binary construct (male and female), so there is no information available on trans respondents. NZGSS metadata are available publicly online (Statistics New Zealand, 2016).

Second, we conduct exploratory analyses on the demographic differences (age, gender groups, ethnicity, and disability status) for the degree of trust toward public institutions. Building on previous studies documenting differential outcomes of risk factors and mental health among trans people (James et al., Citation2016; Su et al., Citation2016), we recognized the necessity of investigating within-group differences in institutional trust, as the first study on this topic. We employed an intercategorical approach to analyze differences across cross-classifications of social identities or positions (Bauer & Scheim, Citation2019).

Third, we examine the relationship between legal systems that can protect trans people from discrimination, and institutional trust which can influence trans people’s levels of psychological distress. The public institutions that we assessed for the third hypothesis comprised parliament, court, and Police, which play key roles in enforcing legal protection. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to empirically test the mediation hypothesis of trust in public institutions on the relationship between perceived legal protection and the mental health of trans people.

Method

Procedure

The Counting Ourselves: Aotearoa New Zealand Trans and Non-binary Health Survey was an anonymous community-based survey designed for trans and non-binary people aged 14 or older and living in Aotearoa (Veale et al., Citation2019). A wide range of recruitment strategies were employed to increase the diversity of participant representation. For example, the research team built relationships with trans and LGBT + community groups, connected with networks of health professionals and academic researchers interested in trans health, and invited community leaders from Indigenous Māori, Pasifika, Asian and disability groups to provide quotes and images to promote the importance of the survey on social media (e.g. Facebook). Most (99%) participants opted to complete the survey online on Qualtrics. Participants were briefed about their rights to withdraw their responses and channels to access support via an information sheet and provided their consent by beginning the survey. The survey was open for participation from June to September 2018. More information regarding the study design can be read in the community report (Veale et al., Citation2019).

Participants

shows the demographic characteristics of participants who completed the section on institutional trust (n = 863). The mean age of participants was 30.3 (SD = 13.6). Most participants identified as New Zealand European (Pākehā). Using the two-step gender classification method (Fraser, Citation2018), about two-fifths of participants were categorized as non-binary (41%) and others as trans women (30%) or trans men (29%). About one-third were residing in major cities such as Auckland or Wellington.

Table 1. Demographic details of counting ourselves participants.

Measures

Gender groups

Gender groups were identified using a two-step method (Fraser, Citation2018). Participants were categorised into four gender groups: trans men, trans women, non-binary individuals assigned female at birth (AFAB), and non-binary individuals assigned male at birth (AMAB). This classification was based on responses to two items that inquired about sex assigned at birth and current gender identities. Participants were classified as trans men if they indicated man, trans man, transsexual, or tangata ira tane as their gender and were assigned female at birth. Trans women were those who selected woman, trans woman, transsexual, or whakawāhine and were assigned male at birth. The classification of Māori, Pacific, and Asian gender identities was discussed with the community advisory group involved in the project. All other participants were classified as non-binary.

Ethnic groups

Participants were asked to select multiple options to the question, ‘‘Which ethnic group or groups do you belong to?’’ We followed the Ministry of Health’s (2017) prioritized ethnicity protocol to create a nominal variable in the order of Māori, Pacific peoples, Asian peoples, Pākehā/New Zealand European, and Other.

Disability status

Participants were administered six questions from the Washington Group Short Set (WGSS), a tool utilized by Statistics New Zealand (Citation2017), to determine their disability status based on any challenges they may face in performing specific activities due to a health problem. Participants were classified as having a disability if they responded that they faced a lot of difficulty or could not perform at least one of the following activities: walking or climbing stairs; hearing, even with the use of a hearing aid; seeing, even while wearing glasses; remembering or concentrating; communicating; and self-care, such as washing all over or dressing.

In this study, we determined the degree of the legal system serving as a structural determinant of health through two measures: perceived legal protection and confidence in the legal system.

Perceived legal protection

We asked participants ‘Do you think New Zealand law protects people against discrimination for being trans or non-binary?’ The response options consisted of ‘No, I do not think any trans or nonbinary people are protected (1)’; ‘I think only some of us are protected (2)’; ‘Yes, I think we are all protected (3)’; and ‘I don’t know’. About one-fifth (n = 174; 20.5%) indicated they did not know (which is likely to include participants uncertain about what counts as discrimination or the legal protection available and those who were unsure of their answer) and these were treated as missing data.

Confidence in legal system

Participants were asked to respond to ‘If you were discriminated against because you are trans or non-binary, how confident are you that the New Zealand legal system would protect you?’ in a four-point scale, from ‘Not at all confident (1)’ to ‘Completely confident (4)’.

Trust toward public institutions (police, courts, parliament, and media)

We asked participants to indicate their degree of trust in public institutions based on their general impression, regardless of the amount of contact they had with these institutions. Using the institutional trust module in NZGSS (Statistics New Zealand, Citation2019), participants were asked to respond to five questions ‘How much do you trust: Police; courts; parliament; and media?’ on a scale from ‘Not at all (0)’ to ‘Completely (10)’. Responses of 4 points or less were classified as having a low trust in the respective public institution.

Psychological distress

Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10; Kessler et al., Citation2002) was employed to measure nonspecific psychological distress symptoms in the past 4 wk. It has undergone validity assessment among the general population in Aotearoa (Ministry of Health, 2018). Participants were asked to complete 10 items with a 5-point response from ‘None of the time (0)’ to ‘All of the time (4)’. Scores of K10 range from 0 to 40 (M = 17.96; SD = 9.59) and the scale demonstrated high internal reliability consistency (α = .94) in our sample (Tan et al., Citation2021).

Data analysis

Preliminary analyses, including descriptive statistics, missing data imputation and correlation analyses, were conducted in IBM SPSS v28. Missing values for variables related to perceived legal protection and institutional trust ranged from 0.8% to 21.9%. The high percentage of missing data included participants who responded ‘don’t know’ when describing their perception of current legal protections. These missing data were imputed using the expectation maximization method through the estimation of means and covariances of available data (Enders, 2003).

Chi-square goodness of fit tests were carried out in VassarStats (Lowry, 2022) to compare the observed proportion for dichotomous institutional trust variables to the expected value of the general population. We relied on risk ratio estimates to depict the effect size differences across different age groups. Next, we carried out linear regression analyses to determine the relationship between demographic characteristics and institutional trust variables. The Generalized Linear Model (GLM) mediation analysis within the jAMM module in Jamovi (Version 2.3; The Jamovi Project, Citation2022) was employed to facilitate the development of multiple mediation models with maximum likelihood regression. To test the mediation hypothesis, we used the bootstrap (percent) estimation method of 1,000 samples to identify the significance of indirect effects of perception of and confidence toward legal systems in mitigating the level of psychological distress via trust in parliament, court, and Police, respectively. Covariates inserted in the mediation model included age, gender groups, and disability status.

Results

When participants were asked whether they thought laws protected trans people from discrimination, slightly more than half (53.6%) responded that some trans people (37.0%) or all trans people (16.6%) were protected. A quarter (25.9%) did not feel that any trans people were protected, and one-fifth (20.5%) did not know. The imputed mean score was 1.87 (SD = .65). Overall, half (51.3%) reported no confidence that the Aotearoa legal system protected trans people against discrimination. Less than one-tenth were very (5.1%) or completely (2.0%) confident that trans people are protected. The mean score was 1.58 (SD = .68) after imputation.

Objective 1: Differences in institutional trust between trans participants and the general population

compares the percentage of low institutional trust among trans participants and the Aotearoa general population across age groups. Approximately two-thirds of trans participants had a low level of trust toward media (65.1%; Mean = 4.41; SD = 2.16), and this was followed by about half with low trust toward parliament (51.6%; Mean = 5.02; SD = 2.40), Police (48.6%; Mean = 5.36; SD = 3.07), or courts (48.0%; Mean = 5.34; SD = 2.59). In comparison to the Aotearoa general populations, we found statistically significant higher percentages of distrust among trans participants toward all the institutions that we examined. There were also large effect size differences, with trans participants having higher risks of expressing distrust toward all institutions (risk ratios ranged from 1.66 for media to 7.48 for Police).

Table 2. Percentage of counting ourselves participants with low levels of institutional trust.

Objective 2: Demographic differences for trust toward institutions

A reduction of effect size differences was noted from younger to older age groups, as we found larger effect size differences for trans young people (aged 15–24) reporting distrust toward institutions relative to the same age group within the general population (ranging from 1.79 for media to 10.04 for Police), and smaller effect size differences for trans older adults (aged 65–74; ranging from 1.00 for media to 4.77 for Police).

presents the results of regression analyses of institutional trust variables across various demographic groups. Significant differences were observed by age, gender groups, and disability status for trust toward Police, courts, and media. We found that older individuals, trans women, and those without a disability status expressed a higher level of trust toward Police, courts, and media. While age and gender groups did not significantly predict trust toward parliament, those with a disability status expressed a lower level of trust in this institution. There were no significant differences in institutional trust based on ethnic groups.

Table 3. Demographic differences for institutional trust.

Objective 3: Relationships between legal protection, institutional trust and psychological distress

Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations of the relevant variables are presented in . As hypothesized, age was positively correlated with all institutional trust variables and perceived legal protection and confidence. Higher ratings on perceived legal protection and confidence corresponded to higher levels of institutional trust. Lower K10 psychological distress scores were found when participants had higher levels of trust in institutions, and higher perceived rates of legal protection and confidence in legal systems.

Table 4. Correlation matrix of legal system, institutional trust, and age, and psychological distress among counting ourselves participants.

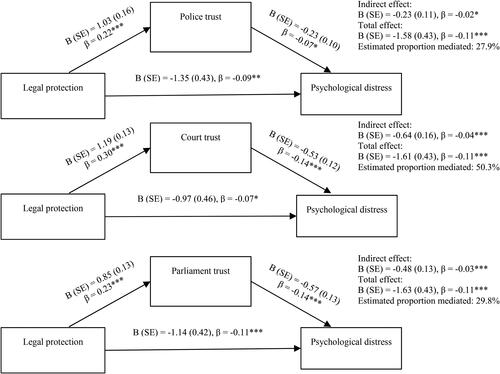

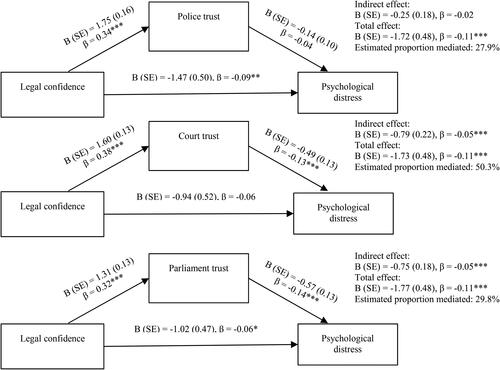

We conducted mediation analyses to examine hypothesized causal pathways (that confidence in legal systems protects against psychological distress) using an intermediary variable (trust in Police, courts, and parliament). and depict the regression paths for the mediation analyses for perception about and confidence in legal protection, accordingly. These analyses show that (a) Participants reporting higher ratings of perceived legal protection and confidence were more likely to trust public institutions; (b) Higher degrees of institutional trust predicted lower levels of psychological distress; (c) Trust in courts and parliament (respectively) partially mediated the two sets of relationships between perception and confidence in legal protection and psychological distress, even when adjusted for demographic variables (age, gender groups and disability status). Trust in Police was only a significant mediator for the relationship between perception in legal protection and psychological distress. Calculation of the proportion of the effect mediated suggests that institutional trust accounts for 27.9% to 50.3% for the total effect of perceived legal protection, and 20.4% to 35.9% for the total effect of confidence in legal systems, on psychological distress. The stated hypothesis that institutional trust mediates the effect of perceived legal protection on psychological distress is therefore supported.

Figure 1. Mediation analysis of institutional trust toward police, court and parliament on the relationship between perception of legal protection, and psychological distress.

Note that the mediation model for police and courts adjusted for age, gender groups and disability status. The mediation model for parliament adjusted for age and disability status.

Figure 2. Mediation analysis of institutional trust toward police, court and parliament on the relationship between confidence of legal protection, and psychological distress.

Note that the mediation model for police and courts adjusted for age, gender groups and disability status. The mediation model for parliament adjusted for age and disability status.

Discussion

This study offers the novel finding that trans people’s perceived lack of legal protection is a structural determinant that explains lower levels of institutional trust and higher levels of psychological distress. Investigating the negative mental health associations of distrust in institutions is critical given the global rise in anti-trans legislation and negative media coverage about trans people and their rights (Indremo et al., Citation2022; Paceley et al., Citation2023).

Trans participants consistently reported significantly lower levels of trust toward Police, courts, parliament and media than the general population. Out of all the institutions that we assessed, trans participants had the highest level of distrust toward the media (65%). The media plays a powerful role in providing knowledge about trans issues and influencing the general public’s attitudes toward and acceptance of trans people (Billard, Citation2016; McInroy & Craig, Citation2015; Scovel et al., Citation2023). In Aotearoa, there is evidence of the voices and personal experiences of trans people being left out or misrepresented by the media with authority given instead to cisgender scientists, politicians and anti-trans groups (Scovel et al., Citation2023). While presenting itself as a politically neutral platform, some media disseminate provocative content and generate controversy that perpetuates cisgenderism (Scovel et al., Citation2023). In recent years, there has been a surge of media discourses (e.g. about trans people’s participation in competitive sports and access to gender-affirming care) that undermine the dignity of trans people in Aotearoa and globally (Duncan & Eggleton, Citation2022; Scovel et al., Citation2023). Our findings postulate that these negative media portrayals of trans people may have affected trans people’s trust toward media and are correlated with heightened levels of psychological distress. As the general trust toward media continues to decline in Aotearoa (Myllylahti & Treadwell, Citation2023), particularly when there is a surge of disinformation around trans issues (Hattotuwa et al., Citation2023), there is an urgency for the media to identify interventions that willcounter the victimization of trans people in public discourses.

Our findings reveal that young trans participants not only had a higher level of distrust toward public institutions compared to general populations, but also compared to older trans participants. Internationally, young people of any gender have low institutional trust as they are more heavily affected by institutional decisions and have less political power and autonomy in effecting change (Chevalier, Citation2019). In Aotearoa, this age group is often framed within discourses that undermine their agency; for example, the media depiction of young people as ‘out of control’ for criminal behaviors (Morton, Citation2022) and the narrative that young people lack the competence to meaningfully participate in social and political activism (Hay, Citation2022). Moreover, trans young people are offered minimal opportunities to engage in decision-making processes that influence their livelihood as they face cisgenderist discourses such as fearmongering about the prescription of puberty blockers and about the growing number of people identifying as non-binary (Indremo et al., Citation2022). Comparatively, older trans people have had a mix of experiences with institutions. Despite the recognition of structural and systemic power within institutions, older trans people are more likely to have built some contacts in agencies over the years and become aware of examples of progress made within such institutions (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., Citation2014; James et al., Citation2016).

In contrast to the New Zealand General Social Survey (Statistics New Zealand, Citation2018) that reported Māori and Pacific peoples were more likely to have low levels of institutional trust (compared to Pākehā), we did not detect significant differences across ethnic groups for trans survey participants. We are mindful of the long history of justified distrust that Indigenous Māori feel toward governmental institutions and agents (i.e. parliament, courts, and Police) due to settler colonialism and the Crown government’s breaches of te Tiriti o Waitangi (the foundational document of New Zealand that guarantees Māori self-determination) (Lindsay Latimer et al., Citation2021). Our unexpected finding suggests that there is no compounding effect on institutional trust for trans people who are also a member of minoritised ethnic communities. Future qualitative research is required to unpack the factors that influence Indigenous and culturally diverse trans peoples’ trust toward institutions through an intersectional lens.

The lower levels of trust reported among trans people with disabilities compared to non-disabled people aligned with the trend observed within general populations (Statistics New Zealand, Citation2018). These findings shed light on the effects of ableism (O’Shea et al., Citation2020) and the inaccessibility of medical, social, and legal institutions in Aotearoa (Murray & Loveless, Citation2021). Much work is still required of the Government to improve the usability of the four capitals (natural, physical/financial, social and human) as outlined in the Treasury’s Living Standards Framework for people with disabilities (Murray & Loveless, Citation2021). March 2024 announcements from the Government to reduce funding for the provision of equipment and caregiver support services for disabled people may further erode people’s trust in legal institutions (Graham, Citation2024).

It is initially unclear why trans men and non-binary people assigned female at birth reported lower levels of institutional trust, even after adjusting for the main effect of age and the interaction effect of age and gender. Previous studies on gender differences among cisgender populations, including the New Zealand General Social Survey (Statistics New Zealand, Citation2018), found no significant difference in levels of institutional trust when measured by sex assigned at birth (McDermott & Jones, Citation2022). However, as these findings do not account for trans people’s experiences, there may be unique considerations among trans populations that have not yet been explored. For example, the relative lack of visibility of transmasculine and non-binary in public discourses may have an impact on these groups’ perceived levels of trust. More empirical research is therefore warranted to understand this relationship between visibility and trust.

Our study showed that the elevated distrust among trans participants toward parliament, court and Police was associated with the degree to which trans people perceived laws passed by parliament legally protected trans people or had confidence the legal system would protect them. Trans scholars and activists have expressed concern about very limited progress in implementing legal and policy reforms needed to protect trans people (Human Rights Commission, Citation2008, 2020). This lack of confidence and distrust is likely to be heightened by events since the 2018 data were collected. Firstly, a High Court decision in March 2023 turned down a request for a judicial review of the decision made by the Minister of Immigration to allow a prominent anti-trans figure to enter Aotearoa and organize protests (Ensor, Citation2023). Community groups responded by filing for a judicial review of the ministerial decision to not prevent this individual’s entry—a case that was later dismissed by the court. Secondly, divisive statements about trans people’s human rights were prominent during the 2023 election campaign (Daalder, Citation2023); and subsequently, the new coalition Government in November 2023 ruled out the introduction of hate speech legislation (Luxon & Peters, Citation2023), including background work the Law Commission had been asked to undertake by the previous Government (Allan, Citation2023).

Despite the high rates of gender minority stress that trans people in Aotearoa face (Fenaughty et al., Citation2022; Veale et al., Citation2019), existing laws have a limited scope in providing explicit legal protection from discrimination with regard to gender identity and expression. The current prohibition of discrimination on the ground of sex under the Human Rights Act 1993 is insufficient to preclude trans people from exposure to gender minority stress (Human Rights Commission, Citation2008, Citation2020). Aotearoa continues to fall behind overseas countries that have put in place specific laws that explicitly prohibit discrimination toward trans people (TGEU, 2022). Our analysis is timely given the Law Commission (Citation2023) is reviewing the protections in the Human Rights Act 1993 for transgender people, non-binary people, and people with diverse sex characteristics in Aotearoa.

In line with overseas studies that have demonstrated the association of trans-inclusive legislation with decreased levels of mental ill-health (e.g. Gleason et al., Citation2016; Miller-Jacobs et al., Citation2023), our findings point to the urgency for government agencies to work closely with trans communities, enabling trans people to participate in decisions that affect their lives (Human Rights Commission, Citation2008, 2020). This is an essential step to build trust and confidence and to demonstrate a commitment to achieving equity for trans people. This will require government agencies to consult appropriately and work collaboratively with trans community organizations to identify current gaps in laws and policies and develop action plans that include the implementation of trans-inclusive legislation (Department of the Prime Minister & Cabinet, Citation2021).

The Police have a responsibility to ensure public safety and maintain law and order, yet about half (48%) of trans participants had low trust toward police in executing their roles. Trans people in Aotearoa have a history of being mistreated by police including harassment, abuse, misgendering, and excessive prosecution and detainment (Human Rights Commission, Citation2008). An earlier study based on the Counting Ourselves dataset (Veale et al., Citation2019) found that out of those who had been detained or charged by police, at least one-tenth reported negative experiences while interacting with police (e.g. harassment and not being able to choose whether they were searched by a female or male e police officer) (Veale et al., Citation2019). There is no data in the 2018 New Zealand Crime and Victim Survey (NZCVS) about trans people, but it does collect sexual orientation data and found gay, lesbian, and bisexual victims were less likely to report crimes to the Police compared to the national average, despite these groups experiencing higher rates of minority stress (Human Rights Commission, 2020).

Limitations

The findings of our study should be interpreted in light of their limitations. First, the Counting Ourselves Survey utilized a convenience sampling that over-represented trans people who were Pākehā (New Zealand European), young, and living in urban cities (i.e. Auckland and Wellington). It is an oversimplification to imply all trans people have a similar degree of distrust toward institutions as those with intersectional minoritised identities may experience additional overlapping forms of marginalization that were not adequately explored in this study (Hamley et al., Citation2021; Veale et al., Citation2019). Our survey achieved proportional representation of Māori compared to the general population, and the under-recruitment of Pacific and Asian peoples may be linked to the limited availability of diverse language options for responding to the survey. Second, while our WGSS measure to classify disability status may encapsulate a broader spectrum of functional difficulty, it does not include aspects of neurodivergence. The next iteration of the Counting Ourselves survey includes a wider range of questions for participants to self-report their disability status as well as the WGSS.

Thirdly, while the K10 measure is useful for providing comparative data to the general population, it is inherently Eurocentric and does not capture the indigenous concept of hauora (holistic health). Next, our measures on structural intervention relied on subjective ratings of legal protection, and confidence in legal systems that protect trans people from discrimination. This is different from overseas studies (e.g. Gleason et al., Citation2016; Rabasco & Andover, Citation2020) that utilised location-specific data (e.g. regions of residence) to determine the level of trans-inclusiveness. We recommend that future studies monitor ongoing legislative changes and their cohort effects on institutional trust and mental health among trans people. Lastly, the cross-sectional design restricts interpretations of causality of perceived legal protection and institutional trust on mental ill-health. The reverse (i.e. trans people with heightened level of psychological distress have lower confidence in legal protection) may also be true; longitudinal research is required to confirm the temporal relationships between these factors.

Conclusion

The relatively higher level of distrust toward public institutions reported among trans people in Aotearoa in this study, and its correlation with psychological distress, may indicate that public institutions are perceived and likely experienced as not accounting for trans people’s needs. The reported distrust may result from past personal experiences of gender identity-based stigma and discrimination within these institutions, or anticipated discrimination based on others’ negative experiences including historic contentions. The lower prevalence of trust toward institutions among younger, trans men, non-binary assigned female at birth, or people with a disability constitutes novel findings that underscore the imperative for nuanced research into the specific determinants shaping institutional trust.

Public institutions have an obligation under binding international human rights standards to respect, protect, and promote human rights. Findings from this study identify gaps in institutional trust which need to be addressed and may inform the Law Commission’s current review into whether the Human Rights Act adequately protects trans people from unlawful discrimination in Aotearoa as well as informing similar considerations internationally. The question of how to build institutional trust warrants continual exploration in the context of working with trans people as a historically marginalized community that continues to experience disproportionately high levels of discrimination.

We reiterate specific recommendations, based on binding international human rights standards, from the Human Rights Commission (2020) and community groups for meaningful engagement with trans people about decisions that impact their lives. With rising concerns for safety nationally and internationally in the current political climate, it is vital for government agencies to review their current practices and name trans people in their action plans. To support building trust and repairing relationships with trans communities, we recommend implementing a formal mechanism for coordinating cross-agency responses, noting calls for a specific Minister and Ministry, to address inequities experienced by trans people (and other LGBTQIA + people) in Aotearoa.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the New Zealand Health and Disability Ethics Committee (18/NTB/66/AM01) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge the work of Counting Ourselves research team, and give special thanks to Elizabeth Kerekere and Gareth Treharne for their feedback in an earlier draft of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 There is a wide range of terms used by Counting Ourselves participants to describe their transgender identity, including Māori, Pacific, and other terms that lack English equivalents. Among these numerous terms are transgender, non-binary, transsexual, whakawahine, tāhine, tangata ira tāne, takatāpui, fa’afafine, fa’atama, fakaleiti, fakafifine, akava’ine, aikāne, vakasalewalewa, genderqueer, gender diverse, bi-gender, cross-dresser, pangender, demigender, agender, trans woman, trans feminine, trans man or trans masculine (Veale et al., Citation2019).

References

- Allan, K. (2023). Proactive release – Work to address incitement of hatred, hate crime and discrimination. https://www.justice.govt.nz/assets/Documents/Publications/Incitement-of-Hatred-Hate-Crime-and-Discrimination_FINAL.pdf

- Ashley, F. (2018). Don’t be so hateful: The insufficiency of anti-discrimination and hate crime laws in improving trans well-being. University of Toronto Law Journal, 68(1), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.3138/utlj.2017-0057

- Baguso, G. N., Aguilar, K., Sicro, S., Mañacop, M., Quintana, J., & Wilson, E. C. (2022). “Lost trust in the system”: System barriers to publicly available mental health and substance use services for transgender women in San Francisco. BMC Health Services Research, 22(1), 930. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08315-5

- Bauer, G. R., & Scheim, A. I. (2019). Advancing quantitative intersectionality research methods: Intracategorical and intercategorical approaches to shared and differential constructs. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 226, 260–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.03.018

- Billard, T. J. (2016). Writing in the margins: Mainstream news media representations of transgenderism. International Journal of Communication, 10, 4193–4218.

- Cascalheira, C. J., Helminen, E. C., Shaw, T. J., & Scheer, J. R. (2022). Structural determinants of tailored behavioral health services for sexual and gender minorities in the United States, 2010 to 2020: A panel analysis. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 1908. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14315-1

- Chevalier, T. (2019). Political trust, young people and institutions in Europe. A multilevel analysis. International Journal of Social Welfare, 28(4), 418–430. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsw.12380

- Daalder, M. (2023). “Race relations among most divisive issues in election – poll” https://newsroom.co.nz/2023/11/03/race-relations-among-most-divisive-issues-in-election-poll/

- Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (2021). Report on Community Hui held in response to the Royal Commission of Inquiry into the Terrorist Attack on Christchurch Mosque. http://tinyurl.com/2p9rj2e8

- DeVylder, J. E., Jun, H., Fedina, L., Coleman, D., Anglin, D., Cogburn, C., Link, B., & Barth, R. P. (2018). Association of exposure to police violence with prevalence of mental health symptoms among urban residents in the United States. JAMA Network Open, 1(7), e184945. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.4945

- Dolotina, B., & Turban, J. L. (2022). A multipronged, evidence-based approach to improving mental health among transgender and gender-diverse youth. JAMA Network Open, 5(2), e220926. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.0926

- Duncan, R., & Eggleton, C. (2022). Mainstream media discourse around top surgery in New Zealand: A qualitative analysis. Australasian Journal of Plastic Surgery, 5(2), 29–36. https://doi.org/10.34239/ajops.v5n2.343

- Ensor, J. (2023). Rainbow groups taking immigration minister Michael wood to court over Posie parker case. https://www.newshub.co.nz/home/politics/2023/03/rainbow-groups-taking-immigration-minister-michael-wood-to-court-over-posie-parker-case.html

- Fenaughty, J., Ker, A., Alansari, M., Besley, T., Kerekere, E., Pasley, A., Saxton, P., Subramanian, P., Thomsen, P., Veale, J. (2022). Identify survey: Community and advocacy report. Identify Survey Team. https://www.identifysurvey.nz/publications

- Fraser, G. (2018). Evaluating inclusive gender identity measures for use in quantitative psychological research. Psychology & Sexuality, 9(4), 343–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2018.1497693

- Fredriksen-Goldsen, K. I., Simoni, J. M., Kim, H.-J., Lehavot, K., Walters, K. L., Yang, J., Hoy-Ellis, C. P., & Muraco, A. (2014). The health equity promotion model: Reconceptualization of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) health disparities. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 84(6), 653–663. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000030

- Gleason, H. A. M. A., Livingston, N. A. M. A., Peters, M. M. E., Oost, K. M. M. A., Reely, E. B. A., & Cochran, B. N. P. (2016). Effects of state nondiscrimination laws on transgender and gender-nonconforming individuals’ perceived community stigma and mental health. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 20(4), 350–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/19359705.2016.1207582

- Graham, R. (2024). Cutting sorely needed supports for carers is cruel and harmful. https://thespinoff.co.nz/society/20-03-2024/cutting-sorely-needed-supports-for-carers-is-cruel-and-harmful

- Hamley, L., Groot, S., Le Grice, J., Gillon, A., Greaves, L., Manchi, M., & Clark, T. (2021). “You’re the one that was on uncle’s wall!”: Identity, whanaungatanga and connection for Takatāpui (LGBTQ+ Māori). Genealogy, 5(2), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy5020054

- Hattotuwa, S., Hannah, K., Taylor, K. (2023). Transgressive transitions: Transphobia, community building, bridging, and bonding within Aotearoa New Zealand’s disinformation ecologies. https://thedisinfoproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Transgressive-Transitions.pdf

- Hay, A. (2022). Nurturing the political agency of young people in Aotearoa New Zealand. (Masters of Arts) Massey University.

- Hughto, J. M. W., Meyers, D. J., Mimiaga, M. J., Reisner, S. L., & Cahill, S. (2022). Uncertainty and confusion regarding transgender non-discrimination policies: Implications for the mental health of transgender Americans. Sexuality Research & Social Policy: Journal of NSRC: SR & SP, 19(3), 1069–1079. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-021-00602-w

- Hughto, J. M. W., Pletta, D., Gordon, L., Cahill, S., Mimiaga, M. J., & Reisner, S. L. (2020). Negative transgender-related media messages are associated with adverse mental health outcomes in a multistate study of transgender adults. LGBT Health, 8(1), 32–41. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2020.0279

- Hughto, J. M. W., Reisner, S. L., & Pachankis, J. E. (2015). Transgender stigma and health: A critical review of stigma determinants, mechanisms, and interventions. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 147, 222–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.010

- Human Rights Commission. (2008). To be who i am: Report of the inquiry into discrimination experienced by transgender people. Human Rights Commission.

- Human Rights Commission. (2020). Prism: Human Rights issues relating to Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Expression, and Sex Characteristics (SOGIESC) in Aotearoa New Zealand – A report with recommendations. New Zealand Human Rights Commission.

- Indremo, M., Jodensvi, A. C., Arinell, H., Isaksson, J., & Papadopoulos, F. C. (2022). Association of media coverage on transgender health with referrals to child and adolescent gender identity clinics in Sweden. JAMA Network Open, 5(2), e2146531. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.46531

- James, S. E., Herman, J. L., Rankin, S., Keisling, M., Mottet, L., & Anafi, M. (2016). The report of the 2015 U.S. transgender survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality.

- Ker, A., Gardiner, T., Carroll, R., Rose, S. B., Morgan, S. J., Garrett, S. M., & McKinlay, E. M. (2022). “We just want to be treated normally and to have that healthcare that comes along with It”: Rainbow young people’s experiences of primary care in Aotearoa New Zealand. Youth, 2(4), 691–704. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth2040049

- Kessler, R. C., Andrews, G., Colpe, L. J., Hiripi, E., Mroczek, D. K., Normand, S. L., Walters, E. E., & Zaslavsky, A. M. (2002). Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine, 32(6), 959–976. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291702006074

- Law Commission (2023). A review of the protections in the Human Rights Act 1993 for people who are transgender, people who are non-binary and people with innate variations of sex characteristics. https://tinyurl.com/IaTangata

- Lindsay Latimer, C., Le Grice, J., Hamley, L., Greaves, L., Gillon, A., Groot, S., Manchi, M., Renfrew, L., & Clark, T. C. (2021). ‘Why would you give your children to something you don’t trust?’: Rangatahi health and social services and the pursuit of tino rangatiratanga. Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online, 17(3), 298–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/1177083X.2021.1993938

- Luxon, C., Peters, W. (2023). Coalition agreement – New Zealand National Party & New Zealand First (54th Parliament). https://assets.nationbuilder.com/nzfirst/pages/4462/attachments/original/1700784896/National___NZF_Coalition_Agreement_signed_-_24_Nov_2023.pdf?1700784896

- McDermott, M. L., & Jones, D. R. (2022). Gender, sex, and trust in government. Politics & Gender, 18(2), 297–320. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X20000720

- McInroy, L. B., & Craig, S. L. (2015). Transgender representation in offline and online media: LGBTQ youth perspectives. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 25(6), 606–617. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2014.995392

- Miller-Jacobs, C., Operario, D., & Hughto, J. M. W. (2023). State-level policies and health outcomes in U.S. transgender adolescents: Findings from the 2019 youth risk behavior survey. LGBT Health, 10(6), 447–455. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2022.0247

- Ministry of Health (2017). HISO 10001:2017 Ethnicity data protocols. https://www.tewhatuora.govt.nz/our-health-system/digital-health/data-and-digital-standards/approved-standards/identity-standards/

- Morton, N. (2022). Auckland young people ‘out of control’ as ram-raids ramp up across city. https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/crime/300566336/auckland-young-people-out-of-control-as-ramraids-ramp-up-across-city

- Murphy (2018). Pride and police: The history, issues and decisions behind the debate. Radio New Zealand. https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/376950/pride-and-police-the-history-issues-and-decisions-behind-the-debate

- Murray, S., & Loveless, R. (2021). Disability, the living standards framework and wellbeing in New Zealand. Policy Quarterly, 17(1), 64–71. https://doi.org/10.26686/pq.v17i1.6732

- Myllylahti, M., Treadwell, G. (2023). Trust in news in Aotearoa New Zealand 2023. AUT research centre for journalism, media and democracy (JMAD). https://www.jmadresearch.com/trustin-news-in-new-zealand

- O’Shea, A., Latham, J.R., McNair, R., Despott, N., Rose, M., Mountford, R., Frawley, P. (2020). Experiences of LGBT IQA+ people with disability in healthcare and community services: Towards embracing multiple identities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17, 8080. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17218080

- Paceley, M. S., Dikitsas, Z. A., Greenwood, E., McInroy, L. B., Fish, J. N., Williams, N., Riquino, M. R., Lin, M., Birnel Henderson, S., & Levine, D. S. (2023). The perceived health implications of policies and rhetoric targeting transgender and gender diverse youth: A community-based qualitative study. Transgender Health, 8(1), 100–103. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2021.0125

- Rabasco, A., & Andover, M. (2020). The influence of state policies on the relationship between minority stressors and suicide attempts among transgender and gender-diverse adults. LGBT Health, 7(8), 457–460. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2020.0114

- Riggs, D. W., Ansara, G. Y., & Treharne, G. J. (2015). An evidence-based model for understanding the mental health experiences of transgender Australians. Australian Psychologist, 50(1), 32–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/ap.12088

- Riggs, D. W., & Treharne, G. J. (2017). Decompensation: A novel approach to accounting for stress arising from the effects of ideology and social norms. Journal of Homosexuality, 64(5), 592–605. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2016.1194116

- Russell, E. K. (2020). Queer histories and the politics of policing. Routledge.

- Scheim, A. I., Perez-Brumer, A. G., & Bauer, G. R. (2020). Gender concordant identity documents and mental health among transgender adults in the USA: A cross-sectional study. The Lancet Public Health, 5(4), e196–e203. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30032-3

- Scovel, S., Nelson, M., & Thorpe, H. (2023). Media framings of the transgender athlete as “legitimate controversy”: The case of Laurel Hubbard at the Tokyo Olympics. Communication & Sport, 11(5), 838–853. https://doi.org/10.1177/21674795221116884

- Serpe, C. R., & Nadal, K. L. (2017). Perceptions of police: Experiences in the trans* community. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 29(3), 280–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538720.2017.1319777

- Statistics New Zealand (2017). Improving New Zealand disability data. https://www.stats.govt.nz/assets/Reports/Improving-New-Zealand-disability-data/improving-new-zealand-disability-data.pdf

- Statistics New Zealand. (2018). Wellbeing statistics. https://www.stats.govt.nz/information-releases/wellbeing-statistics-2018

- Statistics New Zealand (2019). Wellbeing statistics. https://www.stats.govt.nz/assets/Uploads/Well-being-statistics/Well-being-statistics-2018/Download-data/wellbeing-statistics-2018.xlsx

- Su, D., Irwin, J. A., Fisher, C., Ramos, A., Kelley, M., Mendoza, D. A. R., & Coleman, J. D. (2016). Mental health disparities within the LGBT population: A comparison between transgender and nontransgender individuals. Transgender Health, 1(1), 12–20. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2015.0001

- Swan, J., Phillips, T. M., Sanders, T., Mullens, A. B., Debattista, J., & Brömdal, A. (2023). Mental health and quality of life outcomes of gender-affirming surgery: A systematic literature review. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 27(1), 2–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/19359705.2021.2016537

- Tan, K. K., Treharne, G. J., Ellis, S. J., Schmidt, J. M., & Veale, J. F. (2020). Gender minority stress: A critical review. Journal of Homosexuality, 67(10), 1471–1489. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2019.1591789

- Tan, K. K., Treharne, G. J., Ellis, S. J., Schmidt, J. M., & Veale, J. F. (2021). Enacted stigma experiences and protective factors are strongly associated with mental health outcomes of transgender people in Aotearoa/New Zealand. International Journal of Transgender Health, 22(3), 269–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2020.1819504

- Tan, K. K., Watson, R. J., Byrne, J. L., & Veale, J. F. (2022). Barriers to possessing gender-concordant identity documents are associated with transgender and nonbinary people’s mental health in Aotearoa/New Zealand. LGBT Health, 9(6), 401–410. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2021.0240

- Testa, R. J., Habarth, J., Peta, J., Balsam, K., & Bockting, W. (2015). Development of the gender minority stress and resilience measure. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 2(1), 65–77. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000081

- The jamovi project (2022). jamovi. (Version 2.3) [Computer software]. www.jamovi.org

- Treharne, G. J., Riggs, D. W., Ellis, S. J., Flett, J. A. M., & Bartholomaeus, C. (2020). Suicidality, self-harm, and their correlates among transgender and cisgender people living in Aotearoa/New Zealand or Australia. International Journal of Transgender Health, 21(4), 440–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/26895269.2020.1795959

- Veale, J., Byrne, J., Tan, K., Guy, S., Yee, A., Nopera, T., & Bentham, R. (2019). Counting Ourselves: The health and wellbeing of trans and non-binary people in Aotearoa New Zealand. Transgender Health Research Lab, University of Waikato.