?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The study assessed the satisfaction level of stakeholders with Public-Private Partnership (PPP) in Solid Waste Management (SWM) in Ghana. The study was underpinned by the pragmatist paradigm and mixed-methods design. Purposive and stratified random sampling techniques were used to engage 777 respondents for the data. Narrative inquiry, descriptive statistics and ANOVA were used to analyse the data. The study found that even though there was low participation of service users in the contractual arrangement regarding PPP in SWM, the service agreement was highly responsive to their (73%) SWM needs, as they (51.6%) were generally satisfied with the service provided through the agreement. This finding was at variance with the general participation-satisfaction nexus that greater participation leads to stakeholder satisfaction and vice-versa. The implication is that a high level of responsiveness of a service to the needs of stakeholders could sometimes offset the need for greater participation to enhance satisfaction. The result further suggests that the responsiveness-satisfaction nexus is stronger than the participation-satisfaction nexus in the PPP arrangement for SWM in Ghana. The study recommends that PPP arrangements in SWM in Ghana should focus more on adopting innovative ways to deliver services under the agreement to continuously address the immediate needs of service users and sustain their relevance in public service management. It also recommends that Assembly persons should utilise town hall meetings to increase the participation of service users in the contractual and implementation issues regarding PPP in SWM.

Public Interest Statement

There has been increased global interest in the management of public infrastructure and services among international development agencies and governments in recent decades. The belief in the effectiveness of Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) in Solid Waste Management (SWM) has, thus, characterised governance in many developing countries, including Ghana. However, stakeholder participation and interests have been critical to successful PPP implementation, sustainability of SWM and realising the benefits of PPPs. To contribute to the international discourse on successful PPPs, this study assessed the relationship between stakeholder participation and the level of satisfaction with SWM in Ghana. Though there was low participation of service users in the PPP contractual arrangement for SWM, the primary users were generally satisfied with the service. Ghana should, therefore, focus more on adopting innovative ways in its PPPs in SWM to deliver services that continuously address service users’ immediate needs to sustain their relevance in public service management.

1. Introduction

The Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 17 of the United Nations’ Agenda 2030 recognises and promotes effective Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) that are aimed at leveraging the private sector’s innovation and efficiency in service delivery, better risk control and cost savings, and lower costs of financing (Blowfield & Dolan, Citation2014; Lang, Citation2016; Mohammed et al., Citation2023). This study conceptualised PPPs as formal contracts between government authority (public sector) and a private company (private sector) under which a private company finances, builds and operates some elements of public infrastructure and/or service and gets paid over several years, either through charges to users or payments from the public authority, or a combination of both. This conceptualisation is consistent with the approach used by Hall (Citation2015), Gou et al. (Citation2019) and World Bank (Citation2022).

The belief in the effectiveness of the private sector to deliver and manage public goods has been a key feature of neoliberal governance around the globe in recent decades. Such proposed attributes have made PPPs increasingly popular in public infrastructure and service delivery, especially in developing countries. However, the extent to which the move towards PPPs is driven by evidence rather than by neoliberal ideology, where governments play limited roles in the provision of services, remains an open question. For all the enthusiasm about PPPs, Boardman et al. (Citation2016), Piippo et al. (Citation2015) and World Bank (Citation2017) note that the processes in PPPs are not always as straightforward as perceived and that there are limitations that should be recognised.

Responsibility for realising the benefits from PPPs does not rest on the private sector alone but also on the various partners (Saadeh et al., Citation2019). The stakeholders in PPP arrangements are many, including different government organisations, agencies and departments; and various private sector firms that serve as project advisors, contractors, operators and insurers; as well as non-governmental organisations and service users. Each stakeholder has its own interests, plays a specific role, and is positioned differently in terms of the influence it can exercise (Bayliss & Van Waeyenberge, Citation2018; Hall, Citation2015; Sarmento & Renneboog, Citation2016). Thus, the engagement of all the major stakeholders in PPP agreements is imperative to enable them to establish a reward and punishment system to guarantee the maximisation of their interests. Stakeholder engagement ensures that the interests of all parties are reflected in project design and implementation to help promote ownership and sustainability. As a result, Bayliss and Van Waeyenberge suggest that a common platform should be created to ensure effective communication among stakeholders for the successful implementation of projects and programmes.

Related to the public choice perspective, Mostepaniuk (Citation2016) reported that public officials do not appear to vigorously pursue the public interest, but rather, they seek their self-interests. This could affect the maximisation of the interests of various public stakeholders in the partnership. The institutional environments in which decisions are made, coordinated and implemented, therefore, affect the success of PPP arrangements which involve complex relationships among the multiple partners in the provision and management of public goods (Boardman et al., Citation2016; Liu et al., Citation2015).

Considering the multifaceted challenges faced by countries globally in providing sustainable solutions to waste management, the United Nations Environment Programme (Citation2020) and World Health Organisation (Citation2017) advocate an integrative approach to waste generation, collection, treatment and disposal by bringing together all relevant stakeholders to promote sustainable development of nations. This encouraged many developing countries grappling with waste management issues to adopt the PPP approach to Solid Waste Management (SWM). Thus, PPP arrangements enabled the injection of private capital and resources into the management of solid waste, which further relieved governments of funds. Some innovative strategies introduced through the PPP arrangements, such as the polluter-pays principle, enabled Waste Management Companies (WMCs) to regularly collect household wastes and developed environmentally-friendly measures such as recycling and reuse to promote SWM (Oteng-Ababio et al., Citation2017). For example, a PPP arrangement in SWM in the Greater Beirut Area of Lebanon resulted in the lowest collection cost, increased performance efficiency and enhanced environmental protection (Massoud & El-Fadel, Citation2002). Chatri and Aziz (Citation2012) also found that private sector participation in SWM has contributed to enhancing the cost efficiency of delivering SWM services in India.

According to Boampong and Tachie (Citation2017), Ghana was among the first sub-Sahara African countries to be inspired by the World Bank and donor agencies to introduce PPPs in the mid-1990s to revive its ailing public sector and services. This was part of the process of restructuring the Ghanaian economy to reduce financial constraints on the government and ensure that any financial injections from the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund could be invested in productive sectors to boost economic growth to guarantee repayment. However, Ghana’s pace of PPP implementation has been notably slow. This is partly due to the reluctance of the government to lose some level of control in the management of public goods through PPP for political reasons, the absence of a comprehensive policy or law to regulate PPP arrangements, and poor perception from the general public about private sector participation in the management of public goods. The citizenry usually perceives PPP arrangements as underlaid by numerous corrupt deals by state actors (Boampong & Tachie).

The responsibility of SWM in Ghana is placed in the hands of local government through various legislative instruments. Key among them are the Local Governance Act, 2016 (Act 936) and the Environmental Sanitation Policy which was formulated in 1999 and revised in 2009. The Local Governance Act empowers the Metropolitan, Municipal and District Assemblies (MMDAs) to provide municipal services, including undertaking waste management and enacting by-laws to regulate the effective management of wastes in their respective jurisdictions. The Environmental Sanitation Policy also guides waste management practices at every level (from district to national) to address the waste problem and promote the reduction, reuse, recycling and recovery of all types of waste streams by minimising the volume and cost of wastes that end up at the landfills.

Belief in the efficiencies of the private sector, budgetary constraints and increased waste generation from its urban and rural areas compelled the MMDAs to adopt PPP in SWM in Ghana in the mid-1990s after the economic crisis in the 1980s (Boampong & Tachie, Citation2017; Lissah et al., Citation2021; Osei-Kyei et al., Citation2014). The Government of Ghana, through the MMDAs, signed partnership agreements with private sector companies on SWM in 2006 to collect, transport and manage municipal and household wastes effectively. This option was accessed after most cities in Ghana got engulfed in huge heaps of garbage and piles of refuse when waste management was the exclusive responsibility of the central government and local authorities (Oteng-Ababio & Amankwaa, Citation2014; Oteng-Ababio et al., Citation2017). The situation was largely attributed to infrastructural and financial constraints and technical inefficiencies of the public sector.

Even though the PPP arrangements in SWM have since been implemented by the MMDAs in Ghana, the remnants of the failed PPP arrangements in other sectors still stare at the various stakeholders as reminders of the likely fate of the current partnership. According to Piippo et al. (Citation2015), the successful implementation of PPPs largely relies on the extent to which the stakeholders are satisfied with the service delivery regarding the contractual arrangements that bind the partners. Thus, stakeholders are more likely to work harmoniously to promote the sustainability of the partnership when they are satisfied with the service delivery output. The implication is that stakeholder satisfaction is critical in promoting the success and sustainability of PPPs. Boampong and Tachie (Citation2017) reported that the use of the local government system to lead the PPP arrangement for SWM in Ghana was to promote stakeholder participation to enhance their satisfaction. The nexus between participation, responsiveness and service delivery satisfaction has also been a major tenet in the decentralisation theory. However, is it always the case that increased participation and responsiveness lead to stakeholder satisfaction? This study sought to explore this nexus further to ascertain whether increased stakeholder participation and responsiveness lead to stakeholder satisfaction. This is imperative since stakeholder satisfaction is necessary in promoting the sustainability of such critical partnerships for SWM in Ghana. The study focused on PPP in SWM in the Cape Coast and Sekondi-Takoradi Metropolitan Areas in Ghana.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Study area

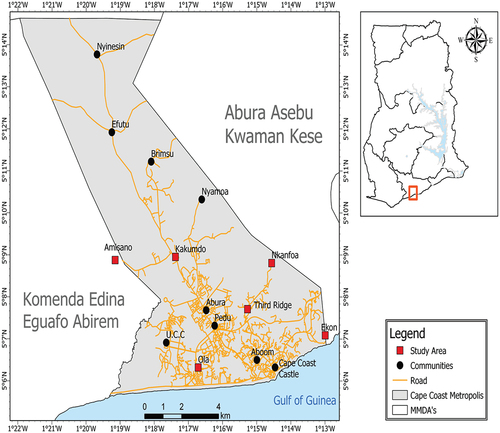

The study was conducted in the Cape Coast Metropolitan Area (CCMA) and Sekondi-Takoradi Metropolitan Area (STMA) in Ghana. The CCMA (Figure ) is one of the oldest districts in Ghana with a total number of 40,386 households and an average household size of 3.5 persons per household. The Metropolis lies within latitudes 5°6’N and 5°20’N, and longitudes 1°11’W to 1°41’W. It is bounded to the south by the Gulf of Guinea, west by the Komenda-Edina-Eguafo-Abrem Municipality, east by the Abura-Asebu-Kwamankese District and to the north by the Twifo-Heman-Lower Denkyira District. The Metropolis occupies an area of approximately 122 km2, with the farthest point at Brabadze, about 17 km from Cape Coast, the capital of the Metropolis, and the Central Region. Due to widespread poverty in the Metropolis and the consequent low financial capacity of the residents, people are neither able nor prepared to pay for waste, especially secondary collection. As a result, waste collection is a heavy burden on the overall CCMA budget (Cape Coast Metropolitan Assembly [CCMA], Citation2014). Consequently, the most widely-used method of solid waste disposal is by public dump in a container, accounting for 56.7 per cent. About two in 10 households (21.9%) dispose of their solid waste by public dump in the open space. House-to-house waste collection accounts for 5.5 per cent.

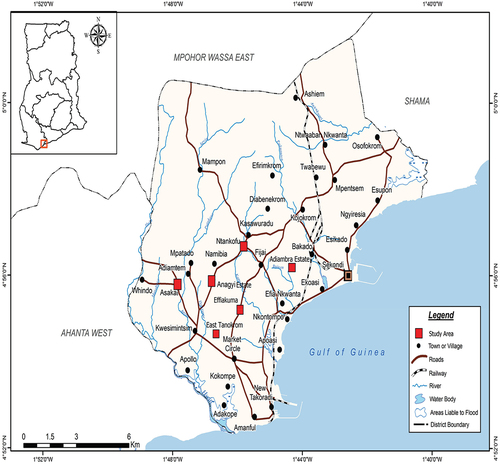

The STMA (Figure ) has a total number of 142,560 households with an average household size of 3.7 persons per household. It is located within latitudes 4°52’N and 5°3’N, and longitudes 1°42’W and 1°50’W. The Metropolis is bounded to the north by the Mpohor-Wassa East District, to the south by the Gulf of Guinea, west by the Ahanta West District and to the east by the Shama District. It has a total land area of 192 km2, with Sekondi as the administrative headquarters. The Ghana Statistical Service (Citation2014) further states that the most widely used method of solid waste disposal is by public dump in the container, accounting for 47.1 per cent. About 1.4 per cent of households dump their solid waste indiscriminately. House-to-house waste collection accounts for 7.9 per cent. Generally, sanitation and waste management in the STMA is the sole responsibility of the Metropolitan Assembly. Three WMCs are engaged to perform this major responsibility using the polluter-pays principle. Solid wastes generated amount to 280 tonnes per day, totalling 102,200 tonnes per year. The final disposal system is a controlled tipping at the engineered landfill site for solid waste and an oxidation system for liquid waste disposal. The waste collection system being operated in the Metropolis is a mix of door-to-door refuse collection and communal container lifting systems.

2.2 Research approach and design

The study was underpinned by the pragmatist paradigm, combining quantitative and qualitative methods to better understand the central theme of the study. Mixed-methods design was adopted to compare qualitative and quantitative data simultaneously to study the processes of selecting private sector stakeholders to partner with the public sector in SWM in Ghana.

2.3 Study population, sampling and sample size

The study population comprised household heads, Assembly members in the two Metropolises, and staff of CCMA, STMA and WMCs [CCMA: Zoomlion Ghana Limited and Alliance Waste Company Limited (previously Zoom Alliance Company Limited); STMA: Zoomlion Ghana Limited, Waste 360, and Deloved WMC] in the two Metropolises. Table presents the samples for the various categories of respondents.

Table 1. Sample details for the various categories of respondents

Purposive sampling was used to select the representatives of the Departments or Units who were related to contract administration and SWM in the Metropolitan Assemblies. The aim was to obtain information on contractual arrangements on PPP in SWM. As a result, the study purposively sampled a representative each from the offices that were directly involved in the SWM contractual arrangements of the Assemblies (i.e., Metropolitan Coordinating Directorate, Metropolitan Planning Office, Environmental Waste Management Department, and Finance and Budget Office). Eight participants (four from each MMDA) were sampled under this category.

Purposive sampling was also used to select representatives of the five WMCs in the two Metropolises. The study further employed purposive sampling to select Assembly members of the Social Services sub-Committee under the two Metropolises (14 - seven each for the two Metropolises). Assembly members of the Social Services sub-Committees were selected for the study because they were directly responsible for issues on sanitation in the Metropolises. Stratified random sampling was used to sample the household heads from the various MMDAs. The MMDAs were organised under residential classes, i.e., high, middle and low, based on the income levels of the residents in locations (see Appendix 1 on sampled respondents from the residential classes). These stratifications were given by the Metropolitan Assemblies based on their own data. Household heads were randomly sampled from these cohorts to ascertain their level of participation in the contractual processes and the extent to which the implementation of the contracts met their needs and expectations.

2.4 Data collection

The study gathered data using in-depth interviews, questionnaire and Focus Group Discussions (FGDs). The in-depth interviews were conducted with the representatives from the Metropolitan Coordinating Directorates, Metropolitan Planning Offices, Environmental Waste Management Departments, and Finance and Budget Offices, while the questionnaire was used to gather data from the household heads. The FGDs were held with the Assembly members of the Social Services sub-Committees of the two Metropolises. A total of 13 interviews and two FGDs were conducted, while 750 questionnaires were administered (details are presented in Table ). The average time for each interview was about 45 minutes, while the questionnaire administration was 30 minutes. The questionnaire focused on contractual arrangements between household heads and the WMCs, level of participation in the preparation of the contract, and level of satisfaction with private sector participation in SWM. The research instruments were pre-tested in the Accra Metropolitan Area, as it had similar waste management issues such as untidy beaches and fish wastes. The data were collected through a face-to-face approach in 2018. The interviews and FGDs were conducted in Twi language, which is the local language in the selected MMDAs. The responses to the interviews and FGDs were digitally recorded with the consent of the participants.

2.5 Data analysis

Narrative inquiry was used to analyse the qualitative data from the institutional respondents. Descriptive (frequencies and percentages) and inferential (chi-square test of independence, Analysis of Variance [ANOVA] and post-hoc Tukey test) statistics were used to analyse the quantitative data. An error margin of 0.05 was used for all inferential statistics.

2.6 Ethical considerations

The study secured ethical clearance from the University of Cape Coast Institutional Review Board, Ghana. The researchers verbally sought participants’ consent to participate in the study, explained the importance of the study to them, and scheduled interview dates that were conducive to the participants. Other ethical issues considered in the study were the anonymity of the respondents and confidentiality of information.

3. Results and discussion

3.1 Contractual arrangements establishing the PPP in SWM

The section describes the contractual arrangements that established the partnership for SWM in the two Metropolises in Ghana. The study found that the initial contractual arrangement of PPP in SWM was secured through a top-down approach. This enabled the WMCs to gain nationwide coverage within the shortest possible time to tackle the sanitation problems of the country. The top-down approach also enabled the WMCs to assume critical control over the MMDAs in the quest to improve sanitation. This, however, created problems regarding monitoring and evaluation of the execution of the contract as the MMDAs responsible for the monitoring were not privy to the details of the contract. The top-down approach did not allow for the greater participation of the local actors, who were responsible for ensuring service quality and maintaining a balance of interests between service users and providers, to guarantee the sustainability of the partnership.

To help promote competition and quality service in SWM, the representative of the Environmental Waste Management Department at STMA reported that the Assemblies were subsequently directed to use competitive bidding processes to select their WMCs. This enabled the Assemblies to engage other private sector companies in waste management services. The criteria set for selecting a WMC by the Assemblies were an inspection of insurance policy to cover one’s operations, a bank statement indicating the financial health of the company, physical inspection of the types and number of waste management equipment owned or available to the companies, service charges of the companies, and previous experiences of the companies in waste management services. The importance of these criteria was to ensure that credible companies with the requisite expertise, resources and capacity were selected for the exercise. The aim was also to ensure that the selected WMCs could sustain their operations over a long period to promote SWM. Further, the criteria were used to boost competition among the WMCs to ensure that the MMDAs procure services at the most reasonable cost. Lastly, the selection criteria helped to justify the selection process and promoted transparency and accountability in the process of engaging the private sector in SWM services.

The selection criteria of the other WMCs showed the MMDAs were very much committed to ensuring that selected companies could effectively execute the task stipulated in the contract. This suggests that greater participation of local actors in PPP contractual processes can help ensure that critical benchmarks are established to protect the interests of both private and public partners to sustain the partnership. The agreed tasks in the contractual arrangement were the collection, transportation and disposal of both household and municipal solid wastes. Subscribers to the service were responsible for paying for the collection, transportation and disposal of household wastes, whereas the Assemblies were responsible for the payment of municipal wastes.

3.2 Stakeholder participation in the contractual arrangements of PPP in SWM

The study enquired about the participation of stakeholders in the contractual arrangements of PPP in SWM in their Metropolis, considering its importance in meeting their needs and interests to informing their level of satisfaction. The representative of the Metropolitan Planning Office at STMA reported that the Assembly members participated in the contractual process for their electorates. However, all the Assembly persons at CCMA intimated that they only participated in the agreement to approve the contract between the Assembly and the WMCs. They also could not give detailed specifications about the contract that established the partnership. This showed that the people’s representatives were not engaged at the highest level of participation, which could also imply that the Assembly persons could not solicit views and inputs from their electorates concerning their interests and ability to pay for the services and incorporate them into the contract. Since the Assembly persons and the MMDAs in general are representatives of the citizens, their active participation in the contractual processes would have been very critical to ensure that the interests of the service users were adequately reflected. They possess the local knowledge about the economic situation of the people and their capacities to afford the services of the WMCs. This would have helped to ensure that innovative services are provided for different categories of households.

The non-participation or low participation of the Assembly persons in the CCMA suggested that the contractual processes with the private sector were largely handled by the technocrats of the Assembly. In Mostepaniuk’s (Citation2016) and Lang’s (Citation2016) criticisms of the public choice philosophy, they stated that PPP contracts are mostly hijacked by local elites to impose their ideas and interests on the service users or project beneficiaries. Such actions pose serious threats to the success and sustainability of PPPs as the local elites become less transparent and accountable in the implementation of PPP arrangements to protect their own interests. Even though the technical staff of the Assembly, comprising members from the Metropolitan Coordinating Directorate, Finance and Budget Office, Metropolitan Planning Office and Environmental Waste Management Department, had the technical expertise to engage in such contractual arrangements, the low or non-engagement of the Assembly persons, who represent the interests of the service users, could affect the level of representativeness of the contract to the stakes of the various partners. This was imperative because a balance of power and interests in PPP contracts is necessary to maintain the partnership.

The Assembly persons from the STMA, on the other hand, asserted that they participated in approving the contracts as well as occasional reviewing of the charges of the WMCs. Thus, the STMA had established a fee fixing resolution committee responsible for approving all fees and charges from the Assembly and any other private organisation performing services on behalf of the Assembly. This enabled the people’s representatives (Assembly persons) to have some control over the activities of the WMCs in the STMA to ensure that their fees match up to the quality of their services. This aligns with one of the tenets of the public choice perspectives in PPP arrangements that the public sector should protect the social and economic welfare of its citizenry by ensuring value for money in its decision-making.

The study inquired from the household heads about how they also entered into the SWM partnership. Households are nuclear families living together as a unit. They constitute users of the services provided through the partnerships. From the study, all the service users denied participating in the contractual processes that established the SWM partnership with WMCs at the Assemblies. They added that the Assembly persons did not organise town hall or communal meetings to enable them to contribute to critical decision making at the Assemblies. They were only informed about the outcomes of the decision-making process from the Assemblies. This suggested that the Assembly persons did not consult their electorates before approving the SWM contracts with the WMCs. The implication is that there was a low level of participation of service users in the contractual process regarding PPP in SWM across the two metropolises. This is likely to create information asymmetry in favour of the WMCs, as the service users may not know the details of the agreements that bind their partnership.

Following the approval of the partnership agreement between the Assemblies and the WMCs, individual households were required to enter into contractual arrangements with the WMCs to access their services. Table presents results on household respondents having contractual arrangements with the WMCs to collect solid wastes.

Table 2. Households having contractual arrangements with WMCs

The majority (76.5%) of the household heads reported that they have entered into a contractual arrangement with a WMC (see Table ). The table further shows that whereas all (100%) the household respondents from STMA had some form of agreement (i.e., either formal [written] or informal [verbal]) with WMCs in the management of solid wastes, a little over half (53.2%) of the respondents from CCMA had such arrangements with WMCs. The study found that all the household heads in CCMA who had contractual arrangements with WMCs were those receiving door-to-door services (mostly from high- and middle-class residential areas) from the companies. This was because they had entered into individual arrangements with the WMCs for door-to-door services at a fee. However, the household heads in CCMA using communal skip containers (mostly within the middle- and low-class residential areas) for dumping their wastes did not have any contractual arrangements with the WMCs. The Assembly was paying on behalf of such service users. As a result, there were no obligations on such service users to ensure the sustainability of the partnership.

From the study, the lack of obligations on some of the household heads in the CCMA made them feel less part of the partnership. This was because they were mostly not informed of any changes in the contractual arrangements. As a result, they were unable to monitor the operations of the WMCs to ensure that they were operating as stipulated in the contract. This could affect the effective implementation and sustainability of the partnership as described by Boardman et al. (Citation2016) that poor knowledge of some of the partners about the tenets of the partnership could affect the effective execution of their roles to sustain others’ interests.

A chi-square test of independence showed that there was a significant association (2 = 51.070, df = 2, p-value = 0.001) between the residential classes of the household heads in CCCMA and having contractual arrangements with WMCs at an error margin of 0.05 (refer to Appendix 2). This suggests that one’s location of residence in CCMA partly determines the contractual arrangements with WMCs. This was because an individual’s location or class of residence is partly influenced by the income level. The implication is that residential classes and income levels of service users should critically be considered in the implementation of the PPP policy in SWM in CCMA.

With respect to STMA, the study found that the Assembly has adopted a polluter-pays principle, which compels each household to pay for the dumping and collection of their household wastes. As a result, respondents who registered for door-to-door services and those using communal skip containers paid for the services they enjoyed in the partnership. Accordingly, both sets of household respondents from STMA considered themselves important partners in the SWM partnership, and empowered to negotiate for adjustments in the charges or quality of services. The results imply that the level of obligations on partners and their ability to demand changes in the contractual arrangements partly influence the extent to which they own the partnership.

Since all the service users in STMA had financial obligations towards their utilisation of waste management services from the WMCs, they felt more empowered to be engaged to negotiate for adjustment in charges. This is because such service users want the service charges to reflect the quality of service received from the WMCs. This posture is critical to improve the level of engagement among the various stakeholders to enhance service quality and sustainability of the partnership. However, since CCMA does not have a polluter-pays principle, some of their service users did not have financial obligations towards the implementation of the PPP arrangement. As a result, some service users were less concerned about the entire arrangements. Their only obligation was to dump their waste in the communal skip container. Such an idle posture from the service users has a negative implication towards the success and sustainability of the PPP arrangement in SWM since they are less concerned about the underlying factors leading to the service quality they are experiencing.

3.2.1 Extent of satisfaction with PPP contract for SWM

The study inquired from the household respondents with contracts about the extent to which the contract met their SWM needs (see Table ). This was important because the extent to which the needs of stakeholders are met helps to sustain their interests in the partnership and perform their assigned roles to keep the partnership (Bayliss & Van Waeyenberge, Citation2018). From Table , the majority (73%) of the household heads who had contracts with the WMCs reported that their needs were highly met in the agreement. This suggests that the majority of the service users considered the service provided through the PPP as responsive to their SWM needs in the metropolises.

Table 3. Extent to which SWM contract meets the needs of household heads

The majority of respondents from both metropolises had their needs highly addressed by the contract. This has the potential of sustaining the partnership as indicated by Sarmento and Renneboog (Citation2016) that stakeholders are more likely to remain in a partnership when their needs and interests are largely or fully addressed or reflected in the contract that binds them. From the study, the primary concern of the household heads was having their wastes easily disposed of from their homes. As a result, having designated areas to dump their refuse and frequently lifting the wastes from their vicinities and homes was seen as having their immediate needs addressed through the PPP arrangement.

Table further shows that there was a statistically significant difference (F-statistic = 11.931, df = 2, p-value = 0.001) at an error margin of 0.05 among the residential classes of the service users about the extent to which the SWM contracts meet their household needs (see Appendix 3). This was due to the differences in the contractual arrangements across different residential classes in Ghana. This suggests that some of the contractual arrangements were more effective in addressing SWM issues of the service users than others. A post-hoc Tukey analysis (see Appendix 4) on ANOVA showed that there was a statistically significant difference between service users in the high-class and medium-class (mean difference = 0.29930, p-value = 0.004) and high-class and low-class (mean difference = 0.63088, p-value = 0.001) residential areas in relation to the extent to which SWM contracts meet their household needs. However, there was no statistically significant difference (mean difference = 0.33158, p-value = 0.032) in the extent to which SWM contracts meet the household needs of service users between those in medium-class and low-class residential areas.

The study found that service users in the high residential areas were most satisfied with their SWM services in relation to their contractual arrangements. This was due to the management of solid wastes (disposal and collection) at the house level as compared to the other residential classes (especially low-class), where service users used communal skip containers. With the use of communal skip containers, service users had to commute certain distances to dispose of their wastes. The management of solid wastes at the house level gave service users some level of control over the usage and payment of the facility. The implication is that the level of control and distance service users commute to dispose of wastes is essential in designing SWM contractual arrangements in Ghana. SWM arrangements in the low-class and middle-class residential areas were largely communal-based with little individual control to ensure that only paid persons used the service. Further, the communal SWM system created some inconveniences for the service users since the skip containers were located away from some individual homes. The study found that high costs accrued to the Metropolitan Assemblies in using communal skip containers in the PPP agreement sometimes discouraged them from allocating more containers to reduce the distance service users in the low and middle classes have to commute to access them. This was a major problem for the CCMA since the Assembly was paying for waste management services involving the skip containers.

The respondents were further requested to indicate their level of satisfaction with the PPP arrangement in SWM (see Table ).

Table 4. Level of satisfaction of service users with the PPP arrangement in SWM

Slightly more than half (51.6%) of the service users were satisfied with the PPP arrangement in SWM. This could be attributed to the fact that the entire arrangement was a direct response to the SWM needs of the service users. Thus, the PPP arrangement provided a more acceptable and easy way of disposing of solid wastes from the various households, which was a major challenge to them. From the FGDs with the Assembly members of the two metropolises, they attested to having heaps of rubbish and garbage at various refuse dump sites before the PPP arrangement in SWM, which created a serious environmental nuisance. The representatives of the WMCs reported during the interviews that one of their major initial tasks was to get rid of decades-age-old heaps of garbage at several traditional or local dump sites across the country. The representative of Zoomlion Ghana Limited from STMA narrated,

Some of the previously traditional dump sites for solid wastes have now been converted to recreational centres, commercial centres, religious centres and residential facilities. The company invested in multiple well-engineered landfill sites, compost and recycling facilities to execute that task effectively.

This narration shows some of the positives associated with adopting PPP in SWM in Ghana. It aligns with the assertions of Boardman et al. (Citation2016) and Sarmento and Renneboog (Citation2016) that PPPs allow for the injection of private capital and innovation to effectively address major public developmental challenges.

The study found that even though the majority of the service users admitted that the PPP arrangement met their household SWM needs, quite a significant proportion (48.4%) were not satisfied with the arrangement. This was largely attributed to the high SWM fees charged by the WMCs, non-participation in fee determination, and the absence of a common platform for service users to engage WMCs and other stakeholders to share their concerns. The ascribed reasons suggest that the fee determination process is imperative to ensuring the satisfaction of stakeholders in the PPP arrangement for SWM. The implication is that the fee determination process should be agreed on by stakeholders at the contractual phase to enhance their level of satisfaction with the services from the agreement. The poor consultation by Assembly persons to their constituents regarding the SWM contractual arrangements could explain the little regard given to the service users during the fee determination. This could be the underlying bane for the less satisfaction by quite a significant proportion of the service users with the PPP arrangement in SWM services. This suggests that measures to help sustain PPP in SWM services in Ghana should critically open up the processes for greater participation from service users at the contractual and fee determination stages.

Further, 47.6 per cent of the service users from CCMA and 55.6 per cent from STMA were satisfied with the PPP arrangement in SWM. This shows that the majority of the service users from CCMA were not satisfied with the PPP arrangement in SWM. This was attributed to high fees, non-participation in fee determination, and long distances to access skip containers. The implication is that issues related to participation, fee charges and ease of access to SWM services are imperative for promoting the satisfaction of service users in a PPP arrangement system.

A comparative analysis was conducted between the level of satisfaction with the PPP arrangement in SWM and the level of income of the respondents (see Table ).

Table 5. A comparative analysis between level of satisfaction of service users with the PPP arrangement in SWM and level of income

Among the number of service users who were satisfied with the PPP arrangement in SWM, 33.1 per cent earned an average monthly income of between GHȻ1,001 and 3,000, while 29.7 per cent earned GHȻ1,000 and below. The results showed that the level of satisfaction of the service users was spread through the various levels of income. This could be attributed to the varied SWM services provided to service users in different residential zones.

Based on the forgone analysis, the study concludes that even though there was low participation from the service users in the contractual arrangement regarding PPP in SWM, the service agreement highly met their SWM needs, as they were generally satisfied with the service provided through the agreement. This finding was at variance with the general participation-satisfaction nexus, as reported by Boampong and Tachie (Citation2017) and other writers, that greater participation leads to stakeholder satisfaction and vice-versa. This was because SWM was a general problem for the service users who searched for an effective way to manage the situation. As a result, creating a system for the service users to get avenues to dispose of their solid wastes was considered a direct response to their SWM needs. The implication is that the level of responsiveness of a service to the needs of stakeholders could sometimes offset the need for greater participation to enhance satisfaction. In other words, the level of responsiveness to user needs from a PPP agreement toward the critical needs of beneficiaries could sometimes cause service users to overlook their minimum level of engagement in the contractual and implementation processes. The result further implies that the responsiveness-satisfaction nexus is stronger than the participation-satisfaction nexus in the PPP arrangement for SWM in Ghana. This suggests that efforts to boost PPPs in achieving the SDGs should focus more on the level of responsiveness of the services towards the critical needs of the targeted beneficiaries.

4. Conclusion and recommendations

Contractual arrangements in PPPs are essential in guaranteeing successful implementation and sustainability. Thus, the level of engagement of stakeholders in the design and implementation of PPPs is imperative to not only improve implementation processes but also to meet the needs and satisfy the interests of all partners. The absence of a polluter-pays principle at CCMA was restricting the capacity of the Assembly to increase the allocation of skip containers to manage solid wastes effectively in the Metropolis. This negatively affected the extent to which the PPP arrangement was satisfying the SWM needs of service users in CCMA as they commuted long distances to dispose of their solid wastes. The study found that there was little engagement of the service users in preparing the contract on PPP in SWM. However, the agreement highly met the SWM needs of the service users. The service users were also generally satisfied with the implementation of the PPP contract in SWM. This was attributed to the high level of responsiveness of the service provision toward the critical need of the service users in SWM. This means that a high level of responsiveness of service provision could achieve high-level satisfaction from the service users regardless of their level of participation. The study concludes that PPPs should focus on the critical needs of society and provide services and projects that are responsive to such needs to enhance stakeholder satisfaction while promoting the relevance and sustainability of the partnership.

The study recommends that the Assembly persons utilise town hall meetings to increase the participation of service users and other stakeholders in the contractual and implementation issues regarding PPP in SWM. Such an avenue will help to create a common platform for high-level stakeholder engagement in the design and implementation of PPP in SWM. It is expected that the effective utilisation of town hall meeting platforms to engage service users and other stakeholders on critical issues such as service fees and service quality will help enhance their level of satisfaction with the PPP arrangements in SWM. The study also suggests that the CCMA should introduce polluter-pays principles that will help shift the financial obligation attached to the allocation of skip containers to the service users. This will help to increase some level of responsibility to service users in the low and middle classes of residence. The financial relief will also enable the Assembly to allocate more skip containers to underserved areas to reduce the distance service users commute to dispose of their solid wastes.

It is further recommended that the PPP arrangements focus more on adopting innovative ways to deliver services under the agreement to continuously address the immediate needs of the service users and sustain their relevance in public service management. Future PPP arrangements should make frantic efforts to increase stakeholder participation, ensure interest maximisation of stakeholders, assign roles and responsibilities to stakeholders, increase transparency and establish service quality standards, accountability mechanisms, monitoring and evaluation systems. These elements are imperative for the sustainability of PPP arrangements. The study again suggested that future studies should explore the responsiveness-satisfaction nexus associated with PPPs in service delivery in other jurisdictions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. 10.6084/m9.figshare.24310225 N/A

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Millicent Abigail Aning-Agyei

Millicent Abigail Aning-Agyei is a Research Fellow at the Directorate of Research, Innovation and Consultancy of the University of Cape Coast, Ghana. She holds a PhD degree in Development Studies. Millicent has garnered over a decade of practical experience in collaborating with other researchers and consultants in several disciplines to conduct research projects and provide consultancy services for local and international agencies and state and non-state actors. Her core expertise includes sustainable development, community development, stakeholder engagement, development policy, forest management, sanitation and waste management, public-private partnership (PPP), and gender studies and analysis. This study primarily contributes to stakeholder participation and interest in PPP arrangements for solid waste management. It postulates that Ghana must not only focus on adopting PPPs in managing its public goods but also consider the immediate needs of primary users in public service management as it strives to achieve Sustainable Development Goals 6, 12 and 17 by 2030.

References

- Bayliss, K., & Van Waeyenberge, E. (2018). Unpacking the public-private partnership revival. The Journal of Development Studies, 54(4), 577–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2017.1303671

- Blowfield, M., & Dolan, C. S. (2014). Business as a development agent: Evidence of possibility and improbability. Third World Quarterly, 35(1), 22–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2013.868982

- Boampong, O., & Tachie, B. Y. (2017). Implications of private participation in solid waste management for collective organisation in Accra, Ghana. In E. Webster, A. O. Britwum, & S. Bhowmik (Eds.), Crossing the divide: Precarious work and future of labour (pp. 121–142). University of KwaZulu-Natal Press.

- Boardman, A. E., Siemiatycki, M., & Vining, A. R. (2016). The theory and evidence concerning public-private partnerships in Canada and elsewhere. (Vol. 9, Issue 12). Calgary, Alberta: School of Public Policy, University of Calgary. https://doi.org/10.11575/sppp.v9i0.42578

- Cape Coast Metropolitan Assembly (CCMA). (2014). Annual composite progress report (2013) for medium-term development plan under Ghana shared growth and development Agenda (GSGDA I) 2010–2013. Retrieved March 8, 2018 from https://new-ndpc-static.s3.amazonaws.com/pubication/CR+Cape+Coast+Municipal_2013_APR.pdf

- Chatri, A. K., & Aziz, A. (2012). Public private partnership in solid waste management: Potential strategies. Athena Infonomics India Pvt Ltd. Retrieved March 10, 2024, from https://www.nswai.org/docs/ReportPPPMunicipalSolidWasteManagement270812.pdf.

- Ghana Statistical Service. (2014). 2010 population and housing census: District analytical report – Sekondi-Takoradi Metropolis. Author.

- Gou, Y., Martek, I., & Chen, C. (2019). Policy evolution in the Chinese public-private partnership market: The shifting strategies of governmental support measures. Sustainability, 11(4872), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11184872

- Hall, D. (2015). Why public-private partnerships don’t work: The many advantages of the public alternative. Public Services International Research Unit. http://www.world-psi.org/sites/default/files/rapport_eng_56pages_a4_lr.pdf

- Lang, M. (2016). Neoliberalism, P3s, and the Canadian municipal water sector: A political-economic analysis of this ‘post-political’ waterscape. Stream: Culture/Politics/Technology, 7(2), 19–31. https://doi.org/10.21810/strm.v7i2.129

- Lissah, S. Y., Ayanore, M. A., Krugu, J. K., Aberese-Ako, M., Ruiter, R. A., & Xue, B. (2021). Managing urban solid waste in Ghana: Perspectives and experiences of municipal waste company managers and supervisors in an Urban municipality. PLOS ONE, 16(3), e0248392. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248392

- Liu, W., Li, W., & Xu, X. (2015). The analysis of the public-private partnership financing model application in Ports of China. Journal of Coastal Research, 73(1), 4–8. https://doi.org/10.2112/SI73-002.1

- Massoud, M., & El-Fadel, M. (2002). Public-private partnerships for solid waste management services. Environmental Management, 30(5), 0621–0630. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-002-2715-6

- Mohammed, N., Salem, Y., Ibanez, M., & Bertolini, L. (2023). How can public-private partnerships be successful? World Bank Brief. Retrieved January 13, 2024, from https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/mena/brief/how-can-public-private-partnerships-ppps-be-successful

- Mostepaniuk, A. (2016). The development of the public-private partnership concept in economic theory. Advances in Applied Sociology, 6(11), 375–388. https://doi.org/10.4236/aasoci.2016.611028

- Osei-Kyei, R., Dansoh, A., & Ofori-Kuragu, J. K. (2014). Reasons for adopting public-private partnership for construction projects in Ghana. International Journal of Construction Management, 14(4), 227–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2014.967925

- Oteng-Ababio, M., & Amankwaa, E. F. (2014). The e-waste conundrum: Balancing evidence from the north and on-the-ground developing countries’ realities for improved management. African Review of Economics and Finance, 6(1), 181–204. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/aref/article/view/106932/96839

- Oteng-Ababio, M., Owusu-Sekyere, E., & Amoah, S. T. (2017). Thinking globally, acting locally: Formalising informal solid waste management practices in Ghana. Journal of Developing Societies, 33(1), 75–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/0169796X17694517

- Piippo, S., Saavalainen, P., Kaakinen, J., & Pongracz, E. (2015). Strategic waste management planning – the organisation of municipal solid waste collection in Oulu, Finland. Pollack Periodica, 10(2), 145–156. https://doi.org/10.1556/606.2015.10.2.13

- Saadeh, D., Al-Khatib, I. A., & Kontogianni, S. (2019). Public-private partnership in solid waste management sector in the West Bank of Palestine. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 191(4), 243. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-019-7395-2

- Sarmento, J. M., Renneboog, L., & Hans Voordijk, D. (2016). Anatomy of public-private partnerships: Their creation, financing and renegotiations. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, 9(1), 94–122. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMPB-03-2015-0023

- United Nations Environment Programme. (2020). Emissions gap report 2020. UN Environment Programme. Retrieved January 13, 2024 from https://www.unep.org/emissions-gap-report-2020.

- World Bank. (2017). Public-private partnerships reference guide (Version 3). The World Bank. Retrieved January 13, 2024, from https://ppp.worldbank.org/public-private-partnership/sites/ppp.worldbank.org/files/documents/PPP%20Reference%20Guide%20Version%203.pdf.

- World Bank. (2022). About public-private partnerships. Retrieved January 13, 2024, from https://ppp.worldbank.org/public-private-partnership/about-public-private-partnerships

- World Health Organisation. (2017). Safe management of waste from healthcare activities. A summary (Reference No. WHO/FWC/WSH/17.05). Retrieved January 13, 2024, from https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/259491/WHO-FWC-WSH-17.05-eng.pdf?sequence=1

Appendix 1:

Population and sample sizes of respondents in CCMA and STMA

Appendix 2:

Chi-square test

Appendix 3:

ANOVA - Extent to which contract meets SWM needs

Appendix 4:

Post Hoc Test

Multiple comparisons

Dependent Variable: Extent to which contract meets SWM needs

Tukey HSD