Abstract

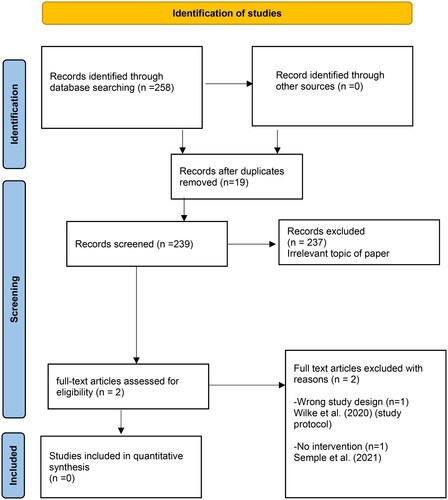

COVID-19 was declared a global pandemic by the World Health Organisation in March 2022, resulting in over 115,0000 deaths worldwide by October of the same year. Only 25% of adults worldwide undertake the recommended levels of Physical activity (PA) for their respective age ranges, potentially exacerbating the symptoms associated with contraction of COVID-19 and recovery. This review aims to identify specific barriers and facilitators to engagement with PA interventions that were implemented during the pandemic. This quantitative study was undertaken adhering to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses. A systematic search was conducted of the following databases: CINAHL, MEDLINE, AMED, Cochrane, SCOPUS and Web of Science. Quality appraisal of selected papers was conducted through the CASP tool, with data extraction by two independent reviewers thereby minimising bias. This was then followed by a meta-analysis of the resulting data; however, no eligible studies were identified. Whilst 258 papers were identified through the database searches, following removal of duplicates (n = 19), the remaining 239 were screened, of these 237 were excluded on title and abstract, with the remaining two subsequently excluded following full read due to failure to meet the inclusion criteria. This review identified research gaps in the study.

REVIEW EDITOR:

Introduction

Physical activity (PA) as any body movement generated by skeletal muscles that results in the expenditure of energy (World Health Organisation [WHO], 2023). PA can be of any kind, whether moderate or vigorous, is beneficial to one’s health (Dhuli et al., Citation2022). An example of PA could be lifting weights, working out, playing, travelling, walking, cycling, dancing, gardening, or cleaning the home. On the other hand, Malm et al. (Citation2019) define PA purely as a physiological concept: all body movement that increases energy use beyond resting levels. PA can benefit individuals living with a health condition by managing symptoms and preventing the emergence of new diseases (GOV.UK, Citation2019). However, public health experts recognise that increasing PA might be stressful, especially if individuals haven’t exercised much in the past or are managing a health issue. It is important to get individuals active in the 2020s, including those who already have a sedentary lifestyle related condition (Kite et al., Citation2021). However, the existing UK policies and recommendations fail to recognise the challenges of making PA lifestyle choices, including participation in PA interventions, for the majority of individuals.

The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) suggests that individuals aged 25 years and over who live a sedentary lifestyle have a risk factor that is responsible for roughly 1.3 million deaths globally (17 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants) (Kyu et al., Citation2016). Worldwide, it is estimated that a sedentary lifestyle is responsible for 6% of coronary heart disease cases, 7% of type 2 diabetes, 10% of breast cancer and 10% of colon cancer cases (Lee et al., Citation2012). These alarming findings, together with a number of systematic reviews that identified physical inactivity as a pandemic (Silva et al., Citation2020), supported the publication of the World Health Organisation Global Plan of Action for Physical Activity 2018–2030. There are several debates surrounding the meaning of PA (DiPietro et al.,Citation2020; Kaur et al.,Citation2020). This study seeks to encourage a relative decrease in sedentary behaviour of 10% by 2025 and of 15% by 2030, both of which will contribute to an increase in the average life expectancy of the population (Amini et al., Citation2021;Pišot, Citation2021) In addition, according to the UK government policy document titled ‘Office for health improvement and disparities of physical activity applying all our health,’ published on 10 March 2022, it is estimated that physical inactivity costs the UK £7.4 billion per year (including £0.9 billion for the National Health Service alone) and is associated with one out of every six deaths that occur in the country (GOV.UK, Citation2022). Unfortunately, compared to the 1960s, the UK population is around 20% less active today. If things keep going the way they are, there will be a 35% decrease in physical activity by the year 2030 in the UK.

On 30 January 2020, the WHO labelled the pandemic a public health emergency of global concern, and on 11 Mar 2020, the WHO labelled the outbreak a worldwide pandemic. The World Health Organization (WHO) declared the COVID-19 outbreak a global pandemic on the 11th of March 2020, by October 2020, more than 42,000 reported cases were identified in over 130 countries resulting in about 1,150,000 deaths (Cucinotta & Vanelli, Citation2020; Mbabazi, Kanmodi, et al., Citation2022; Mbabazi, MacGregor, et al., Citation2022; Stockwell et al., Citation2021). Lockdown measures differed between countries, with some restricting how far individuals can move from their houses and others prohibiting all unnecessary outdoor activity (Roche et al.,Citation2022; Stockwell et al., Citation2021). These restrictions impacted individuals’ employment, education, travel, recreation, and physical activity (PA) (Mbabazi, Kanmodi, et al., Citation2022; Roche et al., Citation2022). The European Center for the Prevention and Control of Disease estimated 5,899,866 cases of COVID-19 between 31 December 2019, and 30 May 2020, following the applied case definitions and testing strategies in the affected countries, including 364,891 deaths due to the disease (Eurosurveillance editorial team, Citation2020). On 30 May 2020, the UK registered 272,607 deaths, and the USA registered 1,747,087. The COVID-19 pandemic had a negative social impact, leading to negative feelings of isolation, mental health concerns, financial pressure, limited outdoor PA, and closed community centres (Appendix Table 6) (Mbabazi, Kanmodi, et al., Citation2022; Roche et al., Citation2022).

Research from the past has shown that individuals from adult Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) communities have worse health outcomes from many health interventions (Ajayi Sotubo, Citation2021). No existing empirical studies have explored and focused on PA interventions regarding the prevention of sedentary lifestyle diseases (Albert et al., Citation2020). In addition, there is a range of barriers and facilitators towards improving PA lifestyle choices amongst UK BAME adults, including but not limited to those in the individual, structural, environmental, and social domains (Mbabazi, Kanmodi, et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, not enough research has been done on PA concerning ethnic minority groups (Magadi & Magadi, Citation2022). There is even less research regarding ethnicity and culture’s role in forming PA lifestyle choices (Mbabazi, Kanmodi, et al., Citation2022; Mbabazi, MacGregor, et al., Citation2022). Mbabazi, Kanmodi, et al. (Citation2022) conducted a systematic review of a systematic reviews (overview) using the Cochrane database. The findings were that no reviews had been carried out regarding the facilitators and barriers to physical activity interventions among adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Mbabazi, Kanmodi, et al. (Citation2022) recommended that there is a need to conduct a systematic reviews of PA intervention programmes among UK adults during the Corona virus pandemic. There is a need to fill this research gap to combat sedentary lifestyles and sedentary lifestyle-related diseases among adult individuals. Mansfield et al. (Citation2021) suggest that COVID-19 affected physical and mental health in most adults in the UK and globally. PA is so significant in enhancing individuals’ mental health and physical well-being (Roche et al., Citation2022). Literature has suggested that living PA has several benefits, such as improving the immune system, which is significant in reducing the death rate during COVID-19 if individuals get infected (da Silveira et al., Citation2021).

PA participation varies amongst adults, and researchers often meet with varying levels of success when implementing interventions that target increasing the uptake of PA (Garner-Purkis et al., Citation2020; Kandula et al., Citation2015). The UK chief medical officer recommends a weekly average of 150 min of moderate intensity physical activity or 75 min of vigorous-intensity physical activity for adults (GOV.UK, Citation2019). In another recent UK government policy document titled ‘Advancing Our Health: Prevention in the 2020s’, PA has been identified as a key element in improving population health. The policy document acknowledges that the level of PA among UK adults is lower than that reported in other Western countries such as France, Australia, and the Netherlands (GOV.UK, Citation2019). A small proportion of individuals in the UK meets these recommendations. The purpose of this study was to report on barriers and facilitators to PA intervention programmes among UK adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. However there is a lack of research on PA in adults, which limits public health experts’ ability to come up with successful interventions that are essential and ensure a healthy PA lifestyle, hence promoting future health. This study justifies using physical activity as opposed to diet as a behavioural intervention for physical and mental well-being because it is a modifiable behavioural intervention. Over the last decades, several studies, including systematic reviews no known study conducted Barriers and Facilitators to Physical Activity Interventions Among UK Adults during COVID-19 Pandemic.

A comprehensive evaluation of recent (04 April 2023) on Barriers and Facilitators to Physical Activity Interventions Programmes Among UK Adults during COVID-19 Pandemic will help to collate and pinpoint current and credible evidence on the current challenges associated with PA among UK adults. Using the PICO (Participants, Interventions, Comparators, Outcomes) framework (Richardson et al.,Citation1995), and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) strategy (Moher et al.,Citation2009), this review aims to categorise, analyse, and summarise the findings Barriers and Facilitators to Physical Activity Interventions Among UK Adults during COVID-19 Pandemic. Using the PICO (Participants, Interventions, Comparators, Outcomes) framework, and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) strategy (Bettany-Saltikov, Citation2010), this review aims to categorise, analyse, and summarise the findings of Barriers and Facilitators to Physical Activity Interventions Among UK Adults during COVID-19 Pandemic.

Review question(s)

What are the findings obtained in the recent Barriers and Facilitators to Physical Activity Interventions Among UK Adults during COVID-19 Pandemic (aged 18 years and above)?

Methods

Operational terms

Barrier to PA: this is a factor that prevents a satisfying and a regular participation in PA (Monforte et al., Citation2021).

Facilitator to PA: this is a factor that enables an individual to voluntarily engage in PA of quality-time (Monforte et al., Citation2021).

PA: this can be defined as any body movement generated by the contraction of skeletal muscles that raises energy expenditure (WHO, Citation2023)

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised control trials, quasi-randomized controlled trials (QRCTs), and prospective cohort studies with control groups were eligible. Excluded were single-group designs, retrospective case-control studies, and qualitative research studies.

Types of interventions

Educational interventions and exercises related to physical activity were included. Any educational interventions or exercises not related to physical activity were not eligible to be included in this review.

Types of outcome measures

Studies that measure the barriers and facilitators to participation in PA intervention among UK adults, during COVID-19 pandemic were included. Studies that report any other outcomes related to behavioural change related to PA among UK adults, during COVID-19 pandemic, were also included. Any outcomes different from those listed above were excluded.

Databases and time frame

The following databases were used for the literature search: CINAHL, MEDLINE, AMED, Cochrane, SCOPUS and Web of Science as shown in Appendix Table 1 supplementary materials. The search, done on 04 April 2023, focused on due to the paucity of primary studies as well as secondary research, public health professionals continue to struggle to develop PA intervention the search was focused.

Searching other resources

In addition to looking through academic databases, they also looked through sources of ‘grey literature’ for studies that were still in progress.

Government policy documents in the UK

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

National Health Services

National Office of Statistics

ETHOS

The Library Database of WHO (WHOLIS)

The Web of Science

We also manually searched the following publications:

Physiotherapy

Spine

Work

Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies

Physical Therapy in Sport

European Spine Journal (ESJ)

JAMA (The Journal of the American Medical Association)

LANCET

PLOS Medicine

Furthermore, we searched through the reference lists of included studies to locate other relevant research articles. Also, authors and subject matter experts were asked for information about investigations that had not been published or were still going on.

Search strategy

Using Boolean operators (‘AND’ and ‘OR’), a filtered search of the identified databases was done using a combination of medical subject heading (MeSH) keywords and its synonyms: physical activity, physical activity or exercise or walking or running or sports or cycling or swimming or sedentary or ‘screen time’,COVID* or ‘SARS-COV-2’ or ‘SARS-COV2’ or SARSCOV2 OR ‘SARSCOV-2’ or ‘2019 nCOV’ OR 2019nCOV OR ‘2019 nCOV’ or 2019nCOV or ‘2019-novel COV’ or ‘nCOV 2019’ or ‘nCov 19’ or coronavirus or ‘corona virus’ or pandemic or lockdown or ‘lock* down’ or isolat* or ‘self-isolat* or ‘stay at home order*’ or quarantine, program* or intervention or training or education or policy or initiative, barriers or obstacles or challenges or difficulties or issues or problems, facilitators or motivators or enablers, UK, and United Kingdom as demonstrated in Appendix Table 1 in the Supplementary materials.

Selection criteria

The selection criteria for selection is identified in Appendix Table 2. A skilled health and social care librarian (JH) developed the search strategy after consulting with the review team’s experts. Two reviewers conducted the literature search (JM and MS) after screening of the title, abstract/full texts of the literature from the database search. Two independent reviewers also performed a screening of the search results (JM and MS). Any disputes between the two reviewers were resolved by a third reviewer (LAN).

Quality assessment

Quality appraisal of selected papers was conducted through the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool, with data extraction by two independent reviewers thereby minimising bias.

Data extraction and analysis

Had there been any eligible study, two review authors (JM and MS) would have extracted data from the full-text articles included in the review. If there would have been any inconsistencies in the extracted data, they would have been resolved by a third reviewer (LAN). In the event of missing data, the primary research author would have been contacted for extra information. We planned to extract the following data:

Study design

Type of study

Duration of study

Country of origin

Participants

Number of participants

Type of participants

Level of education

Interventions

Theory used to explain the intervention

Content, Duration, intensity and delivery of the education programmes Outcomes

Details on the outcome measurements such as definition of the outcome, instruments used to measure the outcome and the period of measurement. The outcomes ‘barriers and facilitators to participation in PA intervention programmes’ or similar outcomes would have been included.

Results

Search outcomes

shows the number of articles found during the literature search, as well as those that were included and removed during the research selection process. A total of 258 published papers were found. After deleting 19 duplicates, there were 239 papers left to be screened. Of those 239, 236 papers were eliminated after titles and abstracts were screened for being irrelevant. This left two papers (Semple et al., Citation2021; Wilke et al., Citation2020) for screening of the full texts. None of these two studies met the inclusion criteria requirements, to be included in the review, after reading the full texts as demonstrated in the Appendix Table 3.

Included studies

There were no quantitative studies that met the criteria for inclusion in this review ().

Excluded studies

We reviewed and excluded 2 full-text articles. They were excluded for using a wrong study design, a study protocol (Wilke et al., Citation2020) and not including an intervention related to physical activity (Semple et al., Citation2021). As a result, these papers were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria for this review (Appendix Table 3). For more information on the characteristics of excluded studies, see the Summary of findings is demonstrated in the Appendix Table 3.

Risk of bias in included studies

No study was assessed for methodological quality.

Allocation

No study was found to be eligible to be included in this review.

Blinding

No study was found to be eligible to be included in this review.

Incomplete outcome data

No study was found to be eligible to be included in this review.

Selective reporting

No study was found to be eligible to be included in this review.

Other potential sources of bias

No study was found to be eligible to be included in this review.

Effects of interventions

No study was found to be eligible to be included in this review.

Quality of the evidence

We searched for research on the topic of barriers and facilitators to PA intervention programmes among UK adults during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as descriptive data of the study, participants, interventions, and methodological quality factors. Although there is some evidence from studies, they were examined and excluded for implementing an incorrect research design, a systematic review, and a study protocol, as well as for excluding an intervention including PA (Semple et al., Citation2021; Wilke et al., Citation2020). We are therefore unable to make any conclusions about the facilitators and barriers to PA intervention programmes among UK adults during COVID-19. The data is valid as of 4 April 2023.

Discussion

Summary of main results

We were unable to find any evidence of barriers and facilitators to physical activity intervention programmes among UK adults during COVID-19 pandemic.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Considering the lack of studies that satisfied all the inclusion criteria, this review is considered to be empty. Notwithstanding this, the review presents critical information regarding the literature gaps regarding barriers and facilitators to physical activity intervention programmes among UK Adults during COVID-19 Pandemic. Three studies were identified, reviewed, and excluded for using inappropriate research design, a systematic review (SR), and a study protocol, respectively (Dixit & Nandakumar, Citation2021; Wilke et al., Citation2020) and for not having an intervention relating to physical activity. Nevertheless, they did not meet the requirements for inclusion in this review, these papers were excluded. However, there is limited evidence on barriers and facilitators to PA intervention programmes among UK Adults during COVID-19 Pandemic. In addition, this SR presents reasons for both facilities and barriers to PA during lockdown in the UK. Findings will be used to improve government policies as PA were limited due to public health and health promotional measures that were put in place to combat the transmission of COVID-19. This meant the adult population including the BAME group were to carryout PA(s) in their back gardens if at all they all had back gardens following the announcement by government chief officers to minimise the spread of COVID 19.

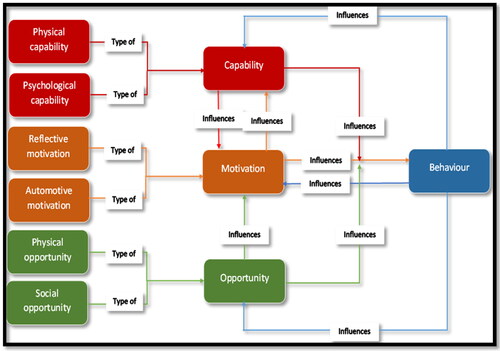

This meant that as a barrier of the COVID-19 lockdown simply exacerbated sedentary lifestyle or decrease in PA during lockdown putting the adult individuals’ group at increased risk of obesity, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, hypertension etc. This is because of poor PA habits and attitudes resulting in increased risk of being hospitalised or death. Many BAME individuals who died due to COVID-19 had a high body mass index (>25) which potentially exacerbated the likelihood of contracting and succumbing to COVID-19. It should be noted that there are many adult BAME groups, such as the Black African-Caribbean Society, that had the capability, opportunity and motivation to do physical activities but struggled to do them because of confined places. The capability (C), opportunity (O) and motivation (M) and behaviour (B) (COM-B) model ( and Appendix Table 4) explains that in such situations it is the individuals who are limited because of the environment and not their attitudes towards doing PA(s). Since COVID 19 remains prevalent although it is post-lockdown, this implies that there they are still negative feelings around social relationships and hence limiting the willingness and possibilities to remain physically active.

Figure 2. COM-B model (adapted from West & Michie, Citation2020).

Conclusions

The findings reveal major research gaps. Although it was not possible to draw conclusions regarding the barriers or facilitators tom physical activity intervention programmes among UK adults during COVID-19 pandemic due to a lack of primary research data. Primary research is required regarding the efficacy of PA intervention programmes generally and more specifically in times of enforced social mobility restrictions, to enable the development of effective evidence-based PA interventions moving forward.

Implications for practice

We are unable to draw any definitive conclusions on the barriers and facilitators to physical activity intervention programmes among UK adults during the COVID-19 Pandemic because of the lack of available data. This is due to the fact that there is no published work that emphasises the gap that is required to enhance practise in knowledge, attitudes, behaviour, and understanding of PA lifestyle among the adult individual’s community in the UK. This is needed to improve practise. Through this evaluation, we were able to identify contemporary research gaps, highlighting current difficulties connected to obstacles and facilitators to physical activity intervention programmes among adults in the UK during the COVID-19 Pandemic. There is a paucity of evidence on the barriers and facilitators of PA intervention among UK adults. This evidence is timely as we are still experiencing the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. This review highlights the need for intervention programmes in the adult BAME UK groups to address the challenges of PA and reduce on mortality rates and physical inactivity related diseases such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, some cancers, hypertension etc. However, due to the paucity of primary studies as well as secondary research, public health professionals continue to struggle to develop PA intervention programmes in adults generally, and more specifically in BAME populations that will assist in minimising the barriers and facilitators. Therefore, there is an urgent need for intervention programmes designed by and for the BAME population to provide evidence in order to lower prevalence, incidence, and death rates among adult minority ethnic groups in the UK. This modification could enhance the government’s PA policies and guide medical care practises so that adult minorities can live productive lives rather than just manage with long-term problems. Due to their perceived lower immunity to COVID 19, this together with reduced uptake of the COVID 19 vaccination and booster campaigns needs to be addressed in any future strategies implemented to address PA engagement with BAME population. The COVID-19 epidemic just exacerbated the challenges already faced by the adult BAME population since the majority are overweight or obese and lead sedentary lifestyles. Therefore, it is vital to develop efficient therapies that can support a PA lifestyle.

Implications for research

The facilitators and barriers to PA intervention programmes among adults during the COVID-19 Pandemic need to be explored in primary research. Models of public health behaviour like the COM-B model () and Transtheoretical Model (TTM) (as demonstrated in Appendix Table 5) should be taken into consideration for future studies. By innovating and critically using the COM-B framework () in the adult BAME community during this COVID19 pandemic and analysing barriers to their PA lifestyle modifications and limitations, this will contribute to knowledge in practise and implement what works for this group of individuals. According to this study, in order to influence this population’s behaviour, interventions need to focus on both the macro and micro levels. Intervention at the family level should also be taken into account in future research as it may be able to maintain PA lifestyle change behaviour. Due to the paucity of research on evidence-informed practise interventions, future research in this area should be directed by a comprehensive mapping of the larger literature to identify models of evidence-informed practise.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Currently, there is no primary study that has explored barriers and facilitators to physical activity Intervention programmes among UK Adults during the COVID-19 Pandemic.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (38.1 KB)Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Abiola Fashina for the proofreading of this final manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Johnson Mbabazi

Dr. Johnson Mbabazi is an associate lecturer at Teesside University. He is also the co-founder and chairman of the Teesside University Health Students Research Network (TUHSRN). He is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Public Health, a Fellow of the European Public Health Association, and an associate of the Royal College of Physicians. He has published a lot of peer-reviewed articles and books. A multiple international award-winning author, lifetime author award winner and UK Plaque winner.

Fiona MacGregor

Fiona MacGregor is a Principal Lecturer for International, SHLS Allied Health at Teesside University and a senior staff member of the Teesside University Health Student Research Network (TUHSRN).

Jeff Breckon

Prof. Jeff Breckon is an associate dean for Research and Innovation in the School of Health and Life Sciences at Teesside University, mentor, and Co-founder of TUHSRN.

Barry Tolchard

Prof. Barry Tolchard is the director of Integrated Care Academy, mentor, and a Co-founder of TUHSRN.

Dorothy Irene Nalweyiso

Dr. Dorothy Irene Nalweyiso is a Doctor of Public Health at Teesside University, part time lecturer at Makerere University and an executive committee member of TUHSRN.

George William Kagugube

George William Kagugube is an associate lecturer and a PhD student at University College London as well as a member of TUHSRN.

Edward Kunonga

Prof. Edward Kunonga is public health consultant, lecturer, mentor, and member of TUHSRN at Teesside University.

Mona Salman

Dr. Mona Salman is Doctor of Public Health at Teesside University and a member TUHSRN.

Lawrence Achilles Nnyanzi

Dr. Lawrence Achilles Nnyanzi is a Senior Lecturer in Research Methods Programme Leader Doctorate in Public Health mentor and a Co-founder of the TUHSRN.

References

- Amini, H., Habibi, S., Islamoglu, A. H., Isanejad, E., Uz, C., & Daniyari, H. (2021). COVID-19 pandemic-induced physical inactivity: The necessity of updating the global action plan on physical activity 2018-2030. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine, 26(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12199-021-00955-z

- Ajayi Sotubo, O. (2021). A perspective on health inequalities in BAME communities and how to improve access to primary care. Future Healthcare Journal, 8(1), 36–12. https://doi.org/10.7861/fhj.2020-0217

- Albert, F. A., Crowe, M. J., Malau-Aduli, A. E. O., & Malau-Aduli, B. S. (2020). Physical activity promotion: A systematic review of the perceptions of healthcare professionals. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(12), 4358. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124358

- Bettany-Saltikov, J. (2010). Learning how to undertake a systematic review: Part 2. Nursing Standard (Royal College of Nursing, 24(51), 47–56; quiz 58, 60. https://doi.org/10.7748/ns2010.08.24.51.47.c7943

- Cucinotta, D., & Vanelli, M. (2020). WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Bio-Medica: Atenei Parmensis, 91(1), 157–160. https://doi.org/10.23750/abm.v91i1.9397

- da Silveira, M. P., da Silva Fagundes, K. K., Bizuti, M. R., Starck, É., Rossi, R. C., & de Resende E Silva, D. T. (2021). Physical exercise as a tool to help the immune system against COVID-19: An integrative review of the current literature. Clinical and Experimental Medicine, 21(1), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10238-020-00650-3

- Dhuli, K., Naureen, Z., Medori, M. C., Fioretti, F., Caruso, P., Perrone, M. A., Nodari, S., Manganotti, P., Xhufi, S., Bushati, M., Bozo, D., Connelly, S. T., Herbst, K. L., & Bertelli, M. (2022). Physical activity for health. Journal of Preventive Medicine and Hygiene, 63(2 Suppl 3), E150–E159. https://doi.org/10.15167/2421-4248/jpmh2022.63.2S3.2756

- DiPietro, L., Al-Ansari, S. S., Biddle, S. J. H., Borodulin, K., Bull, F. C., Buman, M. P., Cardon, G., Carty, C., Chaput, J.-P., Chastin, S., Chou, R., Dempsey, P. C., Ekelund, U., Firth, J., Friedenreich, C. M., Garcia, L., Gichu, M., Jago, R., Katzmarzyk, P. T., … Willumsen, J. F. (2020). Advancing the global physical activity agenda: Recommendations for future research by the 2020 WHO physical activity and sedentary behavior guidelines development group. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 17(1), 143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-020-01042-2

- Dixit, S., & Nandakumar, G. (2021). Promoting healthy lifestyles using information technology during the COVID-19 pandemic. Reviews in Cardiovascular Medicine, 22(1), 115–125. https://doi.org/10.31083/j.rcm.2021.01.187

- Eurosurveillance editorial team. (2020). Updated rapid risk assessment from ECDC on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: Increased transmission in the EU/EEA and the UK. Euro Surveillance: bulletin Europeen Sur Les Maladies Transmissibles = European Communicable Disease Bulletin, 25(12), 2003121. https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.12.2003261

- Garner-Purkis, A., Alageel, S., Burgess, C., & Gulliford, M. (2020). A community-based, sport-led programme to increase physical activity in an area of deprivation: A qualitative case study. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1018. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08661-1

- GOV.UK. (2019). Advancing our health: Prevention in the 2020s–consultation document. GOV. UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/advancing-our-health-prevention-in-the-2020s/advancing-our-health-prevention-in-the-2020s-consultation-document.

- GOV.UK. (2022). Office for health improvement & disparities-physical activity applying all our health. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/.

- Kandula, N. R., Dave, S., De Chavez, P. J., Bharucha, H., Patel, Y., Seguil, P., Kumar, S., Baker, D. W., Spring, B., & Siddique, J. (2015). Translating a heart disease lifestyle intervention into the community: The South Asian Heart Lifestyle Intervention (SAHELI) study: A randomized control trial. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 1064. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2401-2

- Kaur, H., Singh, T., Arya, Y. K., & Mittal, S. (2020). Physical fitness and exercise during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative enquiry. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 590172. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.590172

- Kite, C., Lagojda, L., Clark, C. C. T., Uthman, O., Denton, F., McGregor, G., Harwood, A. E., Atkinson, L., Broom, D. R., Kyrou, I., & Randeva, H. S. (2021). Changes in physical activity and sedentary behaviour due to enforced COVID-19-related lockdown and movement restrictions: A protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(10), 5251. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105251

- Kyu, H. H., Bachman, V. F., Alexander, L. T., Mumford, J. E., Afshin, A., Estep, K., Veerman, J. L., Delwiche, K., Iannarone, M. L., Moyer, M. L., Cercy, K., Vos, T., Murray, C. J., & Forouzanfar, M. H. (2016). Physical activity and risk of breast cancer, colon cancer, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, and ischemic stroke events: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 354, i3857. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i3857

- Lee, I. M., Shiroma, E. J., Lobelo, F., Puska, P., Blair, S. N., & Katzmarzyk, P. T. (2012). Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: An analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet, 380(9838), 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61031-9

- Magadi, J. P., & Magadi, M. A. (2022). Ethnic inequalities in patient satisfaction with primary health care in England: Evidence from recent General Practitioner Patient Surveys (GPPS). PloS One, 17(12), e0270775. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0270775

- Malm, C., Jakobsson, J., & Isaksson, A. (2019). Physical activity and sports-real health benefits: A review with insight into the public health of Sweden. Sports, 7(5), 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports7050127

- Mansfield, K. E., Mathur, R., Tazare, J., Henderson, A. D., Mulick, A. R., Carreira, H., Matthews, A. A., Bidulka, P., Gayle, A., Forbes, H., Cook, S., Wong, A. Y. S., Strongman, H., Wing, K., Warren-Gash, C., Cadogan, S. L., Smeeth, L., Hayes, J. F., Quint, J. K., McKee, M., … Langan, S. M. (2021). Indirect acute effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on physical and mental health in the UK: A population-based study. The Lancet Digital Health, 3(4), e217–e230.(21)00017-0 https://doi.org/10.1016/S2589-7500

- Mbabazi, J., Kanmodi, K. K., Kunonga, E., Tolchard, B., & Nnyanzi, L. A. (2022). Barriers and facilitators of physical activity. Journal of Health and Allied Sciences NU, 13(01), 019–027. https://www.thieme-connect.com/products/ejournals/html/10.1055/s-0042-1753561 https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0042-1753561

- Mbabazi, J., MacGregor, F., Salman, M., Breckon, J., Kunonga, E., Tolchard, B., & Nnyanzi, L. (2022). Exploring the barriers and facilitators to making healthy physical activity lifestyle choices among UK BAME adults during covid-19 pandemic: A study protocol. International Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 1(3), 1. https://research.tees.ac.uk/ws/files/44600956/Exploring_the_barriers.pdf https://doi.org/10.18122/ijpah.010303.boisestate

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 339(1), b2535–b2535. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2535

- Monforte, J., Úbeda-Colomer, J., Pans, M., Pérez-Samaniego, V., & Devís-Devís, J. (2021). Environmental barriers and facilitators to physical activity among university students with physical disability-A qualitative study in Spain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(2), 464. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020464

- Pišot, R. (2021). Physical inactivity - The human health’s greatest enemy. Zdravstveno Varstvo, 61(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.2478/sjph-2022-0002

- Richardson, W. S., Wilson, M. C., Nishikawa, J., & Hayward, R. S. (1995). The well-built clinical question: A key to evidence-based decisions. ACP Journal Club, 123(3), A12–A13. https://www.scinapse.io/papers/1572319397

- Roche, C., Fisher, A., Fancourt, D., & Burton, A. (2022). Exploring barriers and facilitators to physical activity during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(15), 9169. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159169

- Semple, T., Fountas, G., & Fonzone, A. (2021). Trips for outdoor exercise at different stages of the COVID-19 pandemic in Scotland. Journal of Transport & Health, 23, 101280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2021.101280

- Silva, D. A. S., Tremblay, M. S., Marinho, F., Ribeiro, A. L. P., Cousin, E., Nascimento, B. R., Valença Neto, P. D. F., Naghavi, M., & Malta, D. C. (2020). Physical inactivity as a risk factor for all-cause mortality in Brazil (1990-2017). Population Health Metrics, 18(Suppl 1), 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12963-020-00214-3

- Stockwell, S., Trott, M., Tully, M., Shin, J., Barnett, Y., Butler, L., McDermott, D., Schuch, F., & Smith, L. (2021). Changes in physical activity and sedentary behaviours from before to during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown: A systematic review. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine, 7(1), e000960. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsem-2020-000960

- West, R., & Michie, S. (2020). A brief introduction to the COM-B Model of behaviour and the PRIME Theory of motivation [v1]. Qeios. https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10095640/1/WW04E6.pdf https://doi.org/10.32388/WW04E6.2

- Wilke, J., Mohr, L., Tenforde, A. S., Vogel, O., Hespanhol, L., Vogt, L., Verhagen, E., & Hollander, K. (2020). Activity and health during the SARS-CoV2 pandemic (ASAP): Study protocol for a multi-national network trial. Frontiers in Medicine, 7, 302. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2020.00302

- World Health Organization. (2023). Physical activity. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/physical-activity