Abstract

To effectively shape healthcare outcomes and delivery, patient engagement has become increasingly important. It also has a significant impact on customer satisfaction and service quality. This study offers an introspective analysis of healthcare providers’ experiences and perceptions as it explores the relationship between patient engagement, service quality, and customer well-being. The study used a quantitative approach, and data were collected from a sample of 320 healthcare professionals working in different healthcare settings. The study adopted the snowball sampling technique to obtain the needed data for processing and analysis through PLS-SEM. The participants used in this study were Doctors and Nurses in public hospitals in Ghana. This study adds insights from the viewpoint of healthcare providers to the expanding body of literature on patient engagement, service quality, and customer well-being. The results highlight the significance of patient involvement in determining healthcare experiences and results, underscoring the necessity for healthcare institutions to adopt patient-centered care tenets and foster cooperative and empowered cultures. According to the findings, patient engagement fosters open communication, shared decision-making, and collaborative care, all of which are critical components of improving the service quality. To improve treatment adherence, improve health outcomes, and increase patient satisfaction, healthcare providers stress the value of giving patients the freedom to actively participate in their healthcare journey. Additionally, it has been shown that patient engagement enhances customer well-being by encouraging a sense of empowerment, independence, and control over one’s health.

Reviewing Editor:

1. Introduction

The healthcare industry is under increasing pressure to improve patient outcomes and satisfaction while keeping costs under control (Amporfro et al., Citation2021; Berwick et al., Citation2008). The pursuit of optimal patient outcomes and satisfaction has assumed paramount importance in modern healthcare settings. Patient engagement is essential to reaching these objectives because it includes patients actively participating in their healthcare process. Worldwide healthcare systems are realizing the importance of patient engagement in determining service quality and patient satisfaction (Bombard et al., Citation2018; Graban, Citation2018). Therefore, healthcare professionals must comprehend how patient engagement affects the quality of their services and the well-being of their clients. From a healthcare perspective, patient engagement is the active participation of patients in their own healthcare decision-making, treatment plans, and health-related issue management (Duffett, Citation2017). It includes a cooperative approach between patients and healthcare professionals in which the latter are given the authority to speak up for themselves, express their preferences, and make decisions about their health that are well-informed. The provision of healthcare services is characterized by a multitude of factors, including but not limited to accessibility, responsiveness, empathy, communication, and technical competence (Rahim et al., Citation2021). It is commonly known that patient happiness, trust, and general well-being are strongly impacted by service quality (Senić & Marinković, Citation2013; Lumentut & Antonio, Citation2022). But little is known about the ways that service quality affects these results, especially when viewed through the prism of patient involvement.

From a healthcare standpoint, the degree to which healthcare services fulfill or surpass patients’ requirements and expectations is referred to as service quality. It covers a range of aspects of the provision of healthcare, such as patient-centeredness, safety, accessibility, empathy, responsiveness, and clinical efficacy (Perera & Dabney, Citation2020; Jeon & Choi, Citation2021). In the healthcare industry, service quality plays a critical role in guaranteeing favorable patient experiences, contentment, confidence, and eventually, better health results.

Customer well-being is the comprehensive state of health, contentment, and general welfare that people who use healthcare services as clients or patients experience. It includes not just physical health but also the psychological, social, and emotional facets of well-being that are impacted by the standard of medical care one receives. Customer satisfaction is an important outcome of healthcare services. Customer well-being refers to the physical, emotional, and mental health of people who receive healthcare services (Ungaro et al., Citation2024). It is a key indicator of patient satisfaction and is directly related to the quality of care provided by healthcare providers. Healthcare organizations can enhance patient satisfaction, improve health outcomes, and contribute to the general well-being of individuals and communities by promoting the well-being of their customers.

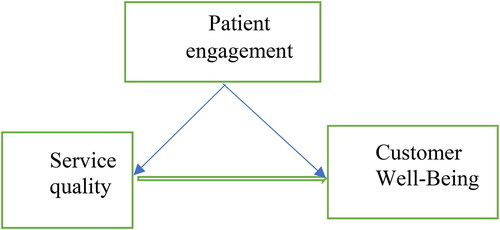

Previous research has primarily examined the direct correlation between patient outcomes or satisfaction and service quality, ignoring the impact function of patient engagement (Manzoor et al., Citation2019; Bombard et al., Citation2018). There exists a deficiency in comprehension regarding how patient engagement functions as a conduit by which service quality impacts the well-being of customers, encompassing satisfaction, trust, and health consequences (Ungaro et al., Citation2024; Netemeyer et al., Citation2020). This study uses an introspective analysis from the viewpoint of healthcare providers to investigate the impact of patient engagement on the relationship between service quality and customer well-being. This research attempts to shed light on how patient engagement is promoted, facilitated, and leveraged within healthcare organizations to improve service quality and customer well-being by exploring the beliefs, attitudes, and practices of healthcare providers. To clarify how patient engagement impacts the relationship between service quality and customer well-being, this study draws on theoretical frameworks including the Service-Dominant Logic theory. Even though patient engagement is becoming more widely acknowledged as a crucial component of healthcare delivery, little is known about how it influences the relationship between customer satisfaction and service quality, especially from the viewpoint of healthcare providers. The impact of service quality on patient outcomes and satisfaction has been the subject of much research; however, the underlying mechanisms by which patient engagement influences these relationships have received less attention. Consequently, research is required to determine how patient engagement influences service quality and customer well-being, with an emphasis on the introspective analysis from the perspective of healthcare professionals.

This study offers actionable recommendations for improving patient engagement, service quality, and customer well-being in healthcare organizations through an introspective analysis, in addition to providing insights into the perceptions and experiences of healthcare providers. In the end, this research’s conclusions may influence clinical practices, organizational tactics, and policy choices meant to enhance patient-centered care delivery and enhance health outcomes for both individuals and communities. The remainder of this paper includes a literature review, a theoretical foundation, as well as material and methods. The research hypotheses are followed by the results and discussion sections. The study concludes with conclusions and recommendations, including future research and limitations.

2. Theoretical foundation

2.1. Service-Dominant logic

Service-dominant logic (SDL) is a theoretical framework that emphasizes the co-creation of value between the customer and the service provider and places the customer at the center of service provision (Vargo & Lusch, Citation2008). According to SDL, service is the foundation of all economic exchange, and value is created through the interaction between the customer and the service provider (Russo et al., Citation2019; Tsegaye et al., Citation2020). From the perspective of healthcare providers, SDL could provide a useful theoretical foundation for understanding the importance of customer co-creation of value in healthcare service delivery. Transformative service goes beyond meeting customers’ basic needs and instead seeks to improve their well-being through personalized and empathetic service delivery (Nwachukwu & Vu, Citation2022). Researchers could use the SDL framework to investigate how transformative service delivery in the healthcare industry can create value for patients by improving their physical, emotional, and social well-being (Verhoef et al., Citation2009). This could entail investigating the collaboration between healthcare providers and patients to co-create personalized service experiences that meet their specific needs and preferences. Furthermore, SDL could help researchers understand how customers in the healthcare industry perceive the concept of value (Grönroos, Citation2008). For example, what do patients value in interactions with healthcare providers that provide value through transformative service delivery? Understanding these value perceptions can help healthcare providers tailor their service delivery to better meet their patients’ needs. Using SDL as a theoretical foundation provides a useful lens for investigating the relationship between transformative service and customer well-being in the healthcare industry, and can aid in identifying the key factors that contribute to successful service delivery in this context.

3. Literature review and hypotheses development

3.1. Customer well-being

A key component of providing healthcare is ensuring the well-being of the patient, which includes many aspects of their physical, mental, and social health. Customer well-being in the healthcare sector is influenced by several factors, such as the standard of care, patient-provider communication, accessibility to care, socioeconomic status, health literacy, and social determinants of health. Positive healthcare experiences and outcomes are facilitated by patient-centered care models, shared decision-making procedures, and efficient care coordination, which have been identified as critical determinants of customer well-being. As healthcare providers strive to provide more patient-centered care that empowers patients and improves their health outcomes, customer well-being has become increasingly important (Berwick et al., Citation2008). Customer satisfaction has also received a lot of attention in the medical literature. It is defined as a state in which people can realize their full potential, cope with everyday stresses, work productively, and give back to their communities (Galderisi et al., Citation2015).

Customer satisfaction is regarded as an important indicator of the quality of care provided as well as a predictor of health outcomes in healthcare (Boehm & Kubzansky, Citation2012). Personalized care and empowerment, for example, have been shown in studies to increase patient satisfaction, trust, and loyalty (Eryılmaz et al., Citation2023). Furthermore, research has shown that customer citizenship behavior, or the voluntary actions that customers take to improve their own and others’ well-being, is positively related to customer well-being in healthcare (Burnaz & Ozcelik, Citation2019). However, there are obstacles to providing healthcare services and promoting customer well-being. One challenge for healthcare providers is a lack of resources and time, which can make it difficult to provide personalized care and engage in social exchanges with customers (Islam et al., Citation2022). Another challenge is the requirement for cultural competence, as healthcare providers must be able to provide care that is sensitive to the diverse needs and values of their patients (Betancourt et al., Citation2018). Yu et al. (Citation2022), for example, investigated the impact of healthcare providers’ empathy on patient satisfaction and loyalty. Patients who perceived higher levels of empathy from their providers were found to be more satisfied with their healthcare experience and more likely to recommend their providers to others. (Shahbaznezhad et al., Citation2021; Muntinga et al., Citation2011), for example, Other studies that investigated the impact of a patient portal on patient satisfaction and engagement, found that patients who used the portal were more satisfied with their healthcare experience and more engaged in their care. The study therefore proposes that;

H1: There is a significant relationship between patient engagement and customer well-being

3.2. Service quality

Service quality is an important part of how healthcare is given, and it has a big impact on how people feel about their care. Service quality is a way of doing business that focuses on giving people good experiences that change their lives. Several studies (Anderson & Fornell, Citation2000; Parasuraman et al., Citation1988) have shown that the level of service has a positive effect on how happy patients are. Patients who get good care are more likely to be happy with it. Healthcare providers have a big impact on how people feel about their care, including how good the care is. Several studies have looked at how healthcare workers see the quality of their services. The SERVQUAL model was first presented by Parasuraman et al. (Citation1988), and it identified five dimensions of service quality: responsiveness, tangibles, assurance, empathy, and reliability. These dimensions have been expanded upon by later research to include things like continuity of care, cultural competence, and patient-centered care (Rahim et al., Citation2021). In the healthcare sector, several factors affect the quality of services provided, such as organizational culture, leadership, workforce competency, technology adoption, and patient engagement. To promote a culture of service excellence and quality improvement initiatives, leadership is essential (Lasserre, Citation2009). Furthermore, telemedicine and electronic health records (EHRs) are two examples of healthcare technology that can improve patient outcomes, coordination, and service efficiency (Uslu & Stausberg, Citation2021). Grönroos (Citation2008), for example, investigated how important service quality is from the point of view of healthcare providers and how important it is for healthcare providers to pay attention to patients’ wants and expectations. Patient-centeredness is an important part of service quality, and it has a big impact on the health and well-being of patients. To provide good service, healthcare workers must be able to put the needs of their patients first. Several studies (Epstein et al., Citation1996; Rahim et al., Citation2021) have shown how important it is for service quality to be focused on the customer. This review of the literature shows how important service quality is in healthcare and how it affects customer satisfaction and health. The review has also shown how important it is for service quality to be patient-centered and how healthcare workers can help make care that is patient-centered. Based on the reviewed literature, the study proposes,

H2: There is a significant relationship between service quality and customer well-being

3.3. Patient engagement

Patient engagement in transformative service" means that patients are actively involved in their own healthcare journey and decision-making processes (Buljac‐Samardzic et al., Citation2021). It emphasizes collaboration between healthcare providers and patients and gives people the power to take an active role in managing their health and well-being (Geese & Schmitt, Citation2023; van Doorn et al., Citation2010). By getting patients involved in their care, doctors and nurses can learn more about each patient’s wants, preferences, and goals. This collaborative method leads to more personalized and patient-centered care, better treatment outcomes, higher patient satisfaction, and better adherence to treatment plans (House et al., Citation2022). Research established that different methods can be used to get patients involved in transformative services (Geese & Schmitt, Citation2023). These include shared decision-making, patient education and empowerment, open communication, and getting patients involved in planning care and setting goals. It sees patients not as passive recipients of healthcare services but as active participants in their care. This improves the total patient experience and health outcomes. Patient involvement is an important part of healthcare because it gives people the power to take an active role in their care and decision-making. This review of the literature looks at recent changes in patient engagement, focusing on key ideas and methods used to get patients involved. The review uses several relevant studies that have been released to give an up-to-date picture of how this field is changing. Patient engagement was defined as a partnership between healthcare workers and patients that focuses on shared decision-making and active participation in care (Harrington et al., Citation2020). Shared decision-making (SDM) is when healthcare providers and patients work together to make choices about treatment options that are based on as much information as possible. Galletta et al. (Citation2022) have talked about how important SDM is for getting patients involved, making them happier, and making sure they stick to their treatment plans. Getting the patient involved is especially important when treating a long-term illness. Further, the literature that there is a positive link between patient involvement and self-management behaviors in people with chronic conditions, which leads to better health outcomes and lower healthcare costs (Fatima et al., Citation2018). Health literacy is another important factor. This is the relationship between a patient’s ability to find, understand, and use health knowledge and their willingness to be involved. Consequently, studies have shown how important it is to tailor health communication methods to improve health literacy and make it easier for patients to get involved (Gibson et al., Citation2022) Healthcare organizations must play a key part in getting patients involved by looking into different organizational strategies that get patients involved and improve patient-centered care. Understanding and using effective ways to get patients involved can help them have a better experience, take better care of themselves, and have better health results. There need to be more studies on innovative interventions and how they affect patient engagement in different types of healthcare settings. Upon the literature review above, the study proposes the hypothesis below;

H3: There is a significant relationship between patient engagement and service quality.

4. Methods and materials

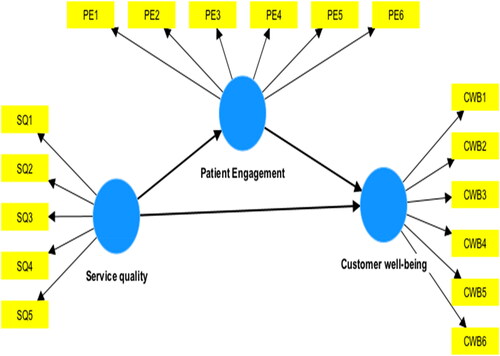

To accomplish the study’s purpose, the researchers used a snowball methodological approach in selecting the preferred respondents for the data collection since the study is quantitative. This sampling technique needs little planning and fewer workforce compared to other sampling techniques and allows the researcher to reach populations that are difficult to sample. The participants used in this study were Doctors and Nurses in public hospitals in Ghana. Before embarking on the data collection, official consent was sought from the respondents through emails, WhatsApp, etc. After their respective approval, the Google link was sent to them. The structured questionnaire was developed into two sections. The first part contains the demographics of the respondents while the second section contains questions relating to the main research constructs. The data collection was conducted from January to March 2023. The study was carefully designed with internal validity as a focus. With many nurses and doctors targeted for the study, the sample size was based on the number of people who could respond through the link sent to their respective association platforms within two weeks after posting the survey questionnaire. Thus, a snowball sampling method was appropriate to make referrals possible to other respondents who fall within the selected criteria. In all, 87 doctors and 233 nurses responded to the survey, making the sample size 320. The structured questionnaire was designed and administered through the online method for the data collection. To carry out the design of the scale, first, the researchers proceeded to an analysis of the literature with the help and collaboration of an expert to identify the most appropriate variables, relationships, and measures for the proposed model (), leading to the generation and validity of content (Bergkvist and Rossiter, Citation2007; Bruce et al., Citation2023). The design of the questionnaires was based on the principle of equanimity to reduce the costs and methodological problems (Šegota et al., 2017). The five-point Likert scale was adopted in this study. Data were collected and analyzed using Partial least square structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). PLS-SEM is a second-generation multivariate technique that combines multiple regressions with confirmatory factor analysis to estimate simultaneously a series of interrelated dependence relationships. SEM is a widespread technique in several fields including marketing, psychology, social sciences, and information systems (Bruce et al., Citation2024; Henseler, Citation2017; Henseler et al., Citation2015). A pre-test with 40 participants was used to ensure the reliability of the scales before the questionnaire was finalized. Each respondent devoted an average of ten minutes to complete the questionnaire. Again, respondents/participants were free to leave the questionnaire’s online portal after answering. Respondents and participants were particularly instructed not to say or write their identities on the questionnaire before or after replying to uphold a high degree of ethics and confidentiality. Descriptive statistics are used to summarize the data on patient engagement and well-being, while inferential statistics are used to test hypotheses about the relationships among variables. Factor analysis is used to identify underlying factors that explain the relationships among the variables, and the structural equation model (SEM is used to test the validity of the proposed theoretical model. below depicts the profile of the respondents.

4.1. Data analysis technique

The study used Partial Least Square and Structural Modeling (PLS-SEM), particularly SmartPLS 3.3, to test the research model. PLS-SEM was applied rather than Co-Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling (CB-SEM). PLS-SEM makes no presumptions regarding the spatial distribution of the data, whereas CB-SEM necessitates that the data have a typical distribution. The use of PLS-SEM makes sense since non-normal data do not drastically alter a statistical test’s outcomes (Amoah & Jibril, Citation2021). Since it rendered the variance of the variables apparent, the Partial Least Squares (PLS) method was utilized for data analysis (Hair et al., Citation2019).

4.2. Measurement of the constructs

The research variables were assessed using the body of existing literature. The present theme was rated on a five-point Likert scale using the new scales (1 = highly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, and 5 = highly agree). The goal was to gauge the respondent’s level of agreement or disagreement with the method used to measure the constructs. A five-point Likert scale was utilized since it is simpler for respondents to complete and takes less time than open-ended questions (Attor et al., Citation2022).

4.3. Common method bias

The researchers considered the probability of CMB (common method bias) before conducting the investigation. In Attor et al. (Citation2022), which was cited in the study, respondents received strict confidentiality guarantees, and the construct items were carefully crafted. In a similar vein, the poll was designed to ensure that respondents would maintain their anonymity and be given the full choice to stop taking it at any time. The researcher examined the robustness of the Common Method Variance (CMV) using a rigorous multicollinearity test, focusing on the variance inflation factor (VIF), to support our claim. As the estimated VIFs are below the threshold of ten (10) in these simulations (see Amoah & Jibril, Citation2021) (see ), CMV is not problematic.

Table 3. Construct items, loading factor, and Variance Inflation Factor (VIF).

5. Empirical results

5.1. Model assessment

The focus of the inspection was on academic works that used PLS-SEM in the depicted research. Dijkstra-Rho Henseler’s and Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were used to gauge the validity and reliability of the study constructs. According to Hair et al. (Citation2019), all the coefficients were above the cut-off point of 0.5, as indicated in the table below. The basic constituents of the study variables’ cognitive characteristics were assessed. By satisfying the minimum values of 0.7 and 0.8 for Jöreskog’s rho (pc) and Cronbach Alpha, respectively, the test met the specifications for the composite reliability of constructs (). As shown in the table below, the convergent validity (Average variance extracted) of 0.5 minimum threshold was adequately obtained.

Table 2. Test of validity and reliability.

The factor loading for each of the preceding constructs was meticulously examined and placed in the proper placements, satisfying the 0.6 requirements and demonstrating the efficacy of the indicators. The connected constructs’ coefficients indicated that 0.778 represented the least loading and 0.949 the most loading (see below for more information). Additionally, because the researchers were very concerned about the problem of multicollinearity, they used the common method variance (CMV) to discover how it was used in proving the variance inflation factor (VIF). Studies by (Amoah et al., Citation2023; Attor et al., Citation2022; Hair et al., Citation2019), and others suggest that CMV is not a concern because the VIF is less than five as opposed to a maximum threshold of 10. For more details, see .

Discriminant validity measures how different a construct is from other components in the Structural model empirically, which means that the constructs are different from each other and are not represented by other constructs (Henseler et al., Citation2015). The researchers were motivated by the literature work of Henseler et al. (Citation2017) to use the Fornell-Larcker criteria to assess the discriminant validity of the latent variables. The values or figures on the diagonal form all exceeded the minimum threshold of 0.5, as shown in () below, which invariably displays the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) as confirmed by Hair et al. (Citation2019). This bolding emphasizes the importance of these values in confirming the discriminant validity of the constructs. The essential and strong criteria of the research constructs were established after the AVE was required to have higher values (both column and row position) than the other constructs, as seen in the discriminant validity table below, by Fornell-Larcker criteria (1981).

Table 4. Discriminant validity-fornell-larcker criterion.

5.2. Hypothesis Testing - PLS-SEM

The structural model depicts the research framework’s hypothesized routes. The structural model (path analysis) is necessary after the model fit is evaluated. This stage is critical to the analysis because it identifies and establishes the causal effect (or linkages) of the emphasized study construct. The current study’s empirical findings demonstrated that all the hypotheses were positive and substantial effects. shows the T-values more than 1.96 (or P-values less than 0.05), regression coefficients, Beta, and significant values. The prediction capacity (coefficient of determination) of the study scenario was examined using the regression model’s coefficient of determination (R2). The coefficient represents the fraction of the change in the dependent variable that can be attributed to an independent (predictor) variable. below depicts the empirical tested research model.

Table 5. Hypothetical path coefficient.

6. Discussions of results

The term ‘patient engagement’ describes how actively patients participate in their healthcare journey, which includes making decisions, planning treatments, and taking charge of their health (Davis et al., Citation2019). It includes actions like looking for health information, following treatment regimens, collaborating with healthcare professionals on decisions, and embracing healthy lifestyle choices. Research indicates that patients with chronic conditions like hypertension or diabetes who are actively involved in their care have better quality of life, fewer hospitalizations, and better disease control. Customer Well-Being is an important outcome of healthcare services. Based on an extensive literature review guided by the Service-Dominant Logic (SDL), the study proposed three hypotheses aimed at achieving the study’s goal. All three hypotheses formulated were supported (agreed). The first hypothesis investigated Patient engagement’s positive impact on Customer Well-Being. In line with (Arifiani et al., Citation2021; Ramez, Citation2012), the findings imply that patient engagement largely contributes to the customers’ well-being. Doctors and nurses better understand each patient’s interests, choices, and aspirations by involving patients in their care. With this team-based approach, patients receive more individualized and patient-centered care, which improves the results of therapy, satisfaction with care, and treatment plan adherence (Davis et al., Citation2019). In response to the hypothesis, the studies of Arifiani et al. (Citation2021; Ramez, Citation2012) affirmed that co-creation and Patient willingness to engage are found to be very essential from the perspective of health service perspective. Improved health outcomes have been repeatedly associated with patient engagement in a variety of medical conditions. Engaged patients are more likely to make healthier lifestyle decisions, stick to treatment plans, and follow preventive care recommendations, all of which improve overall health outcomes and disease management.

The study also set out to investigate whether H2: service quality will positively influence Customer Well-being. The results of the analysis of regression coefficients from the SEM model as shown in clarify that there is a positive relationship between service quality and Customer Well-being. This is so because a p-value of (0.000) affirmed that the formulated hypothesis is supported. Similar studies conducted by Dahl et al. (Citation2018; Zhao & Wei, Citation2019) support the findings of the formulated hypothesis. It is found in the works of (Rodriguez et al., Citation2023; Vogus & McClelland, Citation2016) that patients’ concerns and preferences, level of empathy, and emotional support play a significant role in the service quality of health service delivery. Prior studies conducted in healthcare environments have consistently demonstrated a positive correlation between patient engagement and service quality. These factors tend to enhance service quality and consequently improve Customer well-being of patients. Patients who receive high-quality care are guaranteed prompt access to medical services when they need them. Early detection of health problems is encouraged and waiting times are decreased when prompt access to care, including appointments, diagnostic tests, and treatments, is ensured. By promptly addressing health concerns, minimizing discomfort, and stopping the progression of illnesses or complications, timely access to care improves patient well-being. Evidence of the beneficial correlation between service quality and patient engagement can frequently be found in patient feedback and satisfaction surveys.

Lastly, the third hypothesis was centered on H3: service quality will have a positive relationship with the impact of patient engagement. This is affirmed by the studies of Azman et al. (Citation2020; Kalaja et al., Citation2016). The analysis showed that a significant relationship exists between service quality and patient engagement. The findings also suggest that doctors and nurses believe that it is not enough to say ‘quality patient care is our priority but show by example that indeed the patient is the most important person in their business operations. This requires continuous provision of customer well-being, providing facilities that promote patient engagement and betterment, and tracking customer well-being for continuous improvements. In this sense, doctors and nurses believe in listening to patients and treating their concerns with seriousness, understanding and addressing patients’ challenges, as well as involving patients in making choices about their treatment and care. Healthcare delivery is heavily influenced by service quality, which has a significant impact on patient’s perceptions of their care. Patients are more likely to express greater engagement in their healthcare if they report higher levels of satisfaction with the quality of care they receive. Research has indicated a positive correlation between elevated patient satisfaction levels and heightened patient engagement behaviors, including but not limited to questioning, expressing preferences, and actively participating in treatment decisions. Researchers have discovered that patients who feel more empathy from their healthcare professionals are happier with their treatment and more inclined to recommend it to others. Positive interactions with medical staff, facilities, and services help patients and providers develop a sense of confidence, trust, and partnership that eventually encourages higher levels of patient engagement.

6.1. Implications

The study has several practical, policy, theoretical, and social implications. Practically, healthcare professionals specifically doctors and nurses can utilize the findings to develop and implement strategies that will promote patient engagement. This may involve improving communication skills, providing comprehensive information to patients, and involving them in shared decision-making. Healthcare providers can also design training programs to equip staff with the necessary skills and knowledge to effectively engage patients in their care. Healthcare organizations can allocate resources and create supportive environments to facilitate patient engagement, such as implementing patient portals and other digital tools. Policymakers can also use the study’s findings to inform the development of policies that prioritize patient engagement and promote patient-centered care. They can again establish incentive structures to encourage healthcare providers to incorporate patient engagement practices into their care delivery models. Consequently, policies can be implemented to ensure that healthcare organizations prioritize patient engagement in their quality improvement initiatives. The self-reflection analysis emphasizes how crucial patient-centered care strategies are for encouraging patient participation. Healthcare providers can customize services to meet individual needs, preferences, and cultural backgrounds by giving patients the voice to express their concerns, preferences, and treatment goals. In addition to enhancing the quality of care, this patient-centered approach gives patients a greater sense of control and empowerment over their health.

Theoretically, the results of this introspective analysis can be used to better understand how patient engagement, service quality, and customer well-being interact within healthcare organizations. Also, the study contributes to the understanding of patient engagement by examining its impact on service quality and customer well-being. This helps to establish a clearer link between these constructs and provides a framework for future research. The findings can also guide the development of theoretical models and frameworks that can further explore the mechanisms and factors influencing patient engagement. By emphasizing patient engagement, healthcare providers can promote patient autonomy, dignity, and empowerment, leading to improved patient experiences and outcomes. Patient engagement can contribute to reducing healthcare disparities by ensuring that all individuals, irrespective of their background, have an active role in their healthcare decisions and access to high-quality care; and patients who feel engaged and involved in their healthcare are more likely to have trust in the healthcare system, leading to stronger patient-provider relationships and improved overall satisfaction.

7. Conclusion

The study provides valuable insights into the relationship between the respective constructs. Based on the findings, the study highlights that patient engagement acts as a crucial mediator between service quality and customer well-being. When patients are actively involved in their care, service quality improves, leading to enhanced customer well-being and satisfaction. To promote patient engagement, healthcare providers must establish settings that value candid communication, group decision-making, and cooperative treatment. Active patient participation in their healthcare journey improves the quality of the services provided, which in turn leads to better patient experiences, satisfaction, and, eventually, health outcomes. Data was collected from doctors and nurses to analyze the impact of patient engagement on service and customer well-being within the healthcare service. All the proposed hypotheses were supported by the findings of the study. The study applied the cross-sectional method of design.

7.1. Limitations

While the study focuses on the impact of patient engagement on service quality and customer well-being providing valuable insights, it is important to acknowledge some limitations. The study’s findings may be limited in generalizability due to the specific context and sample used. The research was conducted with a specific group of healthcare providers, and the findings may not be representative of all healthcare settings or provider populations. Replication of the study in different contexts with diverse samples is needed to enhance generalizability. Also, the study relied on self-reported data from healthcare personnel, which may introduce bias. Using multiple data collection methods, such as observations or patient feedback, could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomena under study since the study centers on staff perception. Again, the study focused primarily on the perspectives of healthcare providers, while patient engagement is a dynamic process involving both providers and patients. Incorporating the patient perspective through interviews or surveys could provide a more balanced view and deeper insights into patient experiences and engagement. Moreover, the study employed a cross-sectional design, which limits the ability to establish causal relationships between variables. Longitudinal or experimental designs would be valuable for investigating the temporal sequence and causal effects between patient engagement, service quality, and customer well-being.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Table 1. Demographic profile.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Solomon Abekah Keelson

Solomon Abekah Keelson is an Associate Professor of Marketing and Strategy at the Business Faculty of Takoradi Technical University, Ghana. He holds a PhD in Marketing and Strategy from Open University, Malaysia, an MBA in Marketing, and a Bachelor of Arts in Economics from the University of Cape Coast, Ghana. Prof Keelson also holds a professional certificate in Marketing from the Chartered Institute of Marketing UK. He is a Chartered member of Marketing - UK and Ghana and a fellow of the Chartered Institute of Management Consultants. Keelson is a renowned academic with several publications and taught for over 25 years. He has also worked as theses Assessor (internationally and externally) for various tertiary institutions in Ghana and other countries. He is currently the Dean of the Faculty of Business, at Takoradi Technical University

Jacob Odei Addo

Dr. Jacob Odei Addo is a Ghanaian accomplished academician. With a PhD from Open University of Malaysia (OUM), in Business Administration. Currently, a Senior Lecturer at Takoradi Technical University, and Head of Marketing & Strategy Department. Has a diverse portfolio of published works which shows author’s versatility and ability to explore a wide range of subjects.

John Amoah

John Amoah is a lecturer at the Department of Marketing and HRM of KAAF University College, Kasoa, Ghana. He holds a PhD a in Marketing Management from the Tomas Bata University, Zlin, Czech Republic. Currently, he is the Maters Coordinator of the MBA Program of the Faculty of Business School. He serves on several editorial boards such as Cogent Business and Management among others as well as reviewer. His main research areas are on SMEs development, social media Analysis, Service Marketing among others. The results of his research have been published in peer-reviewed scientific journals and presented at numerous international conferences around the globe.

References

- Amoah, J., & Jibril, A. B. (2021). Social media as a promotional tool towards SME’s development: Evidence from the financial industry in a developing economy. Cogent Business & Management, 8(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2021.1923357

- Amoah, J., Bankuoru Egala, S., Keelson, S., Bruce, E., Dziwornu, R., & Agyemang Duah, F. (2023). Driving factors to competitive sustainability of SMEs in the tourism sector: An introspective analysis. Cogent Business & Management, 10(1), 2163796. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2163796

- Amporfro, D. A., Boah, M., Yingqi, S., Cheteu Wabo, T. M., Zhao, M., Ngo Nkondjock, V. R., & Wu, Q. (2021). Patient satisfaction with healthcare delivery in Ghana. BMC Health Services Research, 21(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06717-5

- Anderson, E. W., & Fornell, C. (2000). Foundations of the American Customer Satisfaction Index. Total Quality Management, 11(7), 869–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/09544120050135425

- Arifiani, L., Prabowo, H., Furinto, A. F., & Kosasih, W. (2021). Respond to environmental turbulence sparks firm performance by embracing business model transformation: an empirical study on the internet service provider in Indonesia. foresight, 24(3/4), 336–357. https://doi.org/10.1108/FS-02-2021-0032

- Eryılmaz, A., Kara, A., & Huebner, E. S. (2023). The Mediating Roles of Subjective Well‐being Increasing Strategies and Emotional Autonomy between Adolescents’ Body Image and Subjective Well‐being. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 18(4), 1645–1671. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-023-10156-1

- Attor, C., Jibril, A. B., Amoah, J., & Chovancova, M. (2022). Examining the influence of brand personality dimension on consumer buying decision: evidence from Ghana. Management & Marketing. Challenges for the Knowledge Society, 17(2), 156–177. https://doi.org/10.2478/mmcks-2022-0009

- Azman, N. A. I., Rashid, N., Ismail, N., & Samer, S. (2020). A Conceptual Framework of Service Quality and Patient Loyalty in Muslim Friendly Healthcare. International Journal of Human and Technology Interaction (IJHaTI), 4(1), 101–106.

- Bergkvist, L., & Rossiter, J. R. (2007). The predictive validity of multiple-item versus single-item measures of the same constructs. Journal of Marketing Research, 44(2), 175–184.

- Berwick, D. M., Nolan, T. W., & Whittington, J. (2008). The triple aim: Care, health, and cost. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 27(3), 759–769. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759

- Betancourt, J. R., Green, A. R., Carrillo, J. E., & Ii, A. (2018). Disparities in Health and Health Care Defining Cultural Competence: A Practical Framework for Addressing Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Health and Health Care. Public Health Reports, 118(4), 293–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0033-3549

- Boehm, J. K., & Kubzansky, L. D. (2012). The heart’s content: The association between positive psychological well-being and cardiovascular health. Psychological Bulletin, 138(4), 655–691.https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027448

- Bombard, Y., Baker, G. R., Orlando, E., Fancott, C., Bhatia, P., Casalino, S., Onate, K., Denis, J.-L., & Pomey, M.-P. (2018). Engaging patients to improve quality of care: a systematic review. Implementation Science, 13(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-018-0784-z

- Bruce, E., Keelson, S., Amoah, J., & Bankuoru Egala, S. (2023). Social media integration: An opportunity for SMEs sustainability. Cogent Business & Management, 10(1), 2173859.

- Bruce, E., Shurong, Z., Amoah, J., Egala, S. B., & Sobre Frimpong, F. K. (2024). Reassessing the impact of social media on healthcare delivery: insights from a less digitalized economy. Cogent Public Health, 11(1), 2301127.

- Buljac‐Samardzic, M., Clark, M. C., van Exel, N. J. A., & van Wijngaarden, J. D. H. (2021). Patients as team members: Factors affecting involvement in treatment decisions from the perspective of patients with a chronic condition. Health Expectations: An International Journal of Public Participation in Health Care and Health Policy, 25(1), 138–148. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.13358

- Burnaz, S., & Ozcelik, A. B. (2019). Customer experience quality dimensions in health care: Perspectives of industry experts. Pressacademia, 6(2), 62–72. https://doi.org/10.17261/Pressacademia.2019.1034

- Dahl, A. J., Peltier, J. W., & Milne, G. R. (2018). Development of a value co-creation wellness model: the role of physicians and digital information seeking on health behaviors and health outcomes. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 52(3), 562–594. https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12176

- Davis, F. D., Bagozzi, R. P., & Warshaw, P. R. (2019). User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models. Management Science, 35(8), 982–1003. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.35.8.982

- Duffett, L. (2017). Patient engagement: what partnering with patients in research is all about. Thrombosis Research, 150, 113–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2016.10.029

- Epstein, S., Pacini, R., Denes-Raj, V., & Heier, H. (1996). Individual differences in intuitive-experiential and analytical-rational thinking styles. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(2), 390–405. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.71.2.390

- Fatima, T., Malik, S. A., & Shabbir, A. (2018). Hospital healthcare service quality, patient satisfaction and loyalty: An investigation in context of private healthcare systems. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 35(6), 1195–1214.

- Galderisi, S., Heinz, A., Kastrup, M., Beezhold, J., & Sartorius, N. (2015). Toward a new definition of mental health. World Psychiatry: official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 14(2), 231–233. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20231

- Galletta, M., Piazza, M. F., Meloni, S. L., Chessa, E., Piras, I., Arnetz, J. E., & D’Aloja, E. (2022). Patient involvement in shared decision-making: Do patients rate physicians and nurses differently? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21), 14229. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114229

- Geese, F., & Schmitt, K.-U. (2023). Interprofessional collaboration in complex patient care transition: A qualitative multi-perspective analysis. Healthcare, 11(3), 359. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11030359

- Gibson, C., Smith, D., & Morrison, A. (2022). Improving health literacy knowledge, behaviors, and confidence with interactive training. Health Literacy Research and Practice, 6(2), e113–e120. https://doi.org/10.3928/24748307-20220420-01

- Graban, M. (2018). Lean hospitals: improving quality, patient safety, and employee engagement. Productivity Press.

- Grönroos, C. (2008). Service logic revisited: who creates value? and who co-creates? European Business Review, 20(4), 298–314. https://doi.org/10.1108/09555340810886585

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2019). Multivariate data analysis (8th ed.). Cengage Learning.

- Harrington, R. L., Hanna, M. L., Oehrlein, E. M., Camp, R., Wheeler, R., Cooblall, C., Tesoro, T., Scott, A. M., von Gizycki, R., Nguyen, F., Hareendran, A., Patrick, D. L., & Perfetto, E. M. (2020). Defining patient engagement in research: results of a systematic review and analysis: Report of the ISPOR patient-centered special interest group. Value in Health: The Journal of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research, 23(6), 677–688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2020.01.019

- Henseler, J. (2017). Partial least squares path modeling. Advanced Methods for Modeling Markets, 361–381.

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43, 115–135.

- House, S., Wilmoth, M., & Kitzmiller, R. (2022). Relational coordination and staff outcomes among healthcare professionals: A scoping review. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 36(6), 891–899. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2021.1965101

- Islam, S., Muhamad, M., & Sumardi, W. H. (2022). Customer-perceived service wellbeing in a transformative framework: Research propositions in the area of health services. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 19(1), 219–245. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-021-00302-6

- Jeon, J., & Choi, S. (2021). Factors influencing patient-centeredness among Korean nursing students: Empathy and communication self-efficacy. In. Healthcare, 9(6), 727. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9060727

- Kalaja, R., Myshketa, R., & Scalera, F. (2016). Service quality assessment in the health care sector: the case of Durre’s public hospital. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 235, 557–565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.11.082

- Lasserre, C. (2009). Fostering a culture of service excellence. The Journal of Medical Practice Management, 26(3), 166–169.

- Lumentut, I. J., & Antonio, F. (2022). Quality of care effect on cancer patient’s well-being and its impact on the private hospital reputation. Universal Journal of Public Health, 10(5), 492–504. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujph.2022.100507

- Manzoor, F., Wei, L., Hussain, A., Asif, M., & Shah, S. I. A. (2019). Patient satisfaction with health care services; an application of physician’s behavior as a moderator. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(18), 3318. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16183318

- Muntinga, D. G., Moorman, M., & Smit, E. G. (2011). Introducing COBRAs: Exploring motivations for brand-related social media use. International Journal of Advertising, 30(1), 13–46. https://doi.org/10.2501/IJA-30-1-013-046

- Netemeyer, R. G., Dobolyi, D. G., Abbasi, A., Clifford, G., & Taylor, H. (2020). Health literacy, health numeracy, and trust in doctor: effects on key patient health outcomes. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 54(1), 3–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12267

- Nwachukwu, C., & Vu, H. M. (2022). Service innovation, marketing innovation, and customer satisfaction: Moderating role of competitive intensity. SAGE Open, 12(2), 215824402210821. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440221082146

- Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A., & Berry, L. L. (1988). SERVQUAL: A multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. Journal of Retailing, 64(1), 12–40.

- Perera, S., & Dabney, B. W. (2020). Case management service quality and patient-centered care. Journal of Health Organization and Management, https://doi.org/10.1108/JHOM-12-2019-0347

- Rahim, A. I. A., Ibrahim, M. I., Musa, K. I., Chua, S. L., & Yaacob, N. M. (2021). Patient satisfaction and hospital quality of care evaluation in malaysia using SERVQUAL and facebook. Healthcare, 9(10), 1369. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9101369

- Ramez, W. S. (2012). Patients’ perception of health care quality, satisfaction, and behavioral intention: an empirical study in Bahrain. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 3(18)

- Rodriguez, A., Patton, C. D., & Cara Stephenson-Hunter, C. (2023). Impact of locus of control on patient-provider communication: A systematic review. Journal of Health Communication, 28(3), 190–204.https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2023.2192014

- Russo, G., Tartaglione, A. M., & Cavacece, Y. (2019). Empowering patients to co-create a sustainable healthcare value. Sustainability, 11(5), 1315. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11051315

- Senić, V., & Marinković, V. (2013). Patient care, satisfaction and service quality in health care. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 37(3), 312–319. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-6431.2012.01132.x

- Shahbaznezhad, H., Dolan, R., & Rashidirad, M. (2021). The role of social media content format and platform in users’ engagement behavior. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 53(1), 47–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2020.05.0

- Tsegaye, A., Bjørne, J., Winther, A., Kökönyei, G., Cserjési, R., & Logemann, H. N. A. (2020). Attentional bias and disengagement as a function of Body Mass Index in conditions that differ in anticipated reward. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 9(3), 818–825. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2020.00073

- Ungaro, V., Di Pietro, L., Guglielmetti Mugion, R., & Renzi, M. F. (2024). A systematic literature review on transformative practices and well-being outcomes in healthcare service. Journal of Service Theory and Practice, https://doi.org/10.1108/JSTP-03-2023-0071

- Uslu, A., & Stausberg, J. (2021). Value of the electronic medical record for hospital care: update from the literature. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(12), e26323. https://doi.org/10.2196/26323

- van Doorn, J., Lemon, K. N., Mittal, V., Nass, S., Pick, D., Pirner, P., & Verhoef, P. C. (2010). Customer engagement behavior: Theoretical foundations and research directions. Journal of Service Research, 13(3), 253–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670510375599

- Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2008). Service-dominant logic: continuing the evolution. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-007-0069-6

- Verhoef, P. C., Lemon, K. N., Parasuraman, A., Roggeveen, A., Tsiros, M., & Schlesinger, L. A. (2009). Customer experience creation: Determinants, dynamics and management strategies. Journal of Retailing, 85(1), 31–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2008.11.001

- Vogus, T. J., & McClelland, L. E. (2016). When the customer is the patient: Lessons from healthcare research on patient satisfaction and service quality ratings. Human Resource Management Review, 26(1), 37–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2015.09.005

- Yu, C., Xian, Y., Jing, T., Bai, M., Li, X., Li, J., Liang, H., Yu, G., & Zhang, Z. (2023). More patient-centered care, better healthcare: the association between patient-centered care and healthcare outcomes in inpatients. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1148277.https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1148277

- Yu, C. C., Tan, L., Le, M. K., Tang, B., Liaw, S. Y., Tierney, T., Ho, Y. Y., Lim, B. E. E., Lim, D., Ng, R., Chia, S. C., & Low, J. A. (2022). The development of empathy in the healthcare setting: a qualitative approach. BMC Medical Education, 22(1), 245. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-022-03312-y

- Zhao, C., & Wei, H. (2019). The highest hierarchy of consumption: A literature review of consumer well-being. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 07(04), 135–149. https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2019.74012