Abstract

Despite robust evidence linking alcohol, processed meat, and red meat to colorectal cancer (CRC), public awareness of nutrition recommendations for CRC prevention is low. Marginalized populations, including those in rural areas, experience high CRC burden and may benefit from culturally tailored health information technologies. This study explored perceptions of web-based health messages iteratively in focus groups and interviews with 48 adults as part of a CRC prevention intervention. We analyzed transcripts for message perceptions and identified three main themes with subthemes: (1) Contradictory recommendations, between the intervention’s nutrition risk messages and recommendations for other health conditions, from other sources, or based on cultural or personal diets; (2) reactions to nutrition risk messages, ranging from aversion (e.g. “avoid alcohol” considered “preachy”) to appreciation, with suggestions for improving messages; and (3) information gaps. We discuss these themes, translational impact, and considerations for future research and communication strategies for delivering web-based cancer prevention messages.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04192071..

Introduction

Robust scientific evidence links dietary intake to several cancers, including breast, colorectal, and prostate cancers. However, large segments of the U.S. adult population do not know that alcohol, red meat, and processed meats can increase cancer risk [Citation1]. For instance, 1 in 8 breast cancer cases in women can be attributed to alcohol intake [Citation2] and the risk of colorectal cancer (CRC) rises by 7% for each additional 10 grams a day of ethanol intake (which is the carcinogenic substance in alcoholic beverages) [Citation3], yet most U.S adults (nearly 60%) are not aware that alcohol can increase cancer risk [Citation4,Citation5]. Similarly, only 43% and 53% of people are aware that diets high in red and processed meat, respectively, increase cancer risk [Citation6]. Knowledge gaps about the links between nutrition and cancer present a challenge to promoting prevention measures that support population health. These knowledge gaps may be particularly felt among geographically rural populations, who have unique risk profiles and barriers to cancer screening such as longer distances to health care services. Rural populations’ higher cancer burden compared to non-rural populations, in terms of cancer incidence, late-stage diagnosis, and mortality, as well as lower dietary quality, make this a particularly important population to engage [Citation7,Citation8].

Communicating the nutrition – cancer link

In 2020, an expert panel convened by the U.S. National Cancer Institute proposed increasing focus on communication strategies along the cancer continuum as a strategy to increase awareness of the alcohol – cancer link [Citation9]. However, the complexity of accomplishing a seemingly simple communication task should not be ignored. For one, nutrition recommendations may vary depending on the health goal or disease under consideration, thus disease context is important. For example, some cancer prevention recommendations may differ from recommendations promoting heart health. Second, message recipients are tasked with making health decisions in the context of multiple health conditions and comorbidities. Finally, cultural norms can affect people’s engagement with health messages [Citation10].

Disease-specific nutrition communication

For cancer prevention, it is recommended to avoid alcohol [Citation11]. However, for overall health, the USDA Dietary Guidelines for Americans say that adults who choose to drink alcohol should limit their intake to two drinks or less per day for men and one drink or less per day for women [Citation12]. And despite the lack of formal recommendations on alcohol consumption for heart health, the scientific evidence linking light wine consumption to cardioprotective effects may shape the public’s belief that alcohol use, in general, promotes cardiovascular health [Citation13–15]. Similarly, there is scientific evidence that some dietary patterns (e.g. ketogenic diets with high meat intake) show efficacy for the management of obesity and type 2 diabetes, a message that directly conflicts with nutrition recommendations for CRC prevention (i.e. limiting red and processed meat consumption).

Source-specific nutrition communication

People’s sources of information may also affect overall cancer prevention behaviors. Adults obtain health information from many sources (e.g. physicians, the internet, media, friends/family members, and coworkers), and the internet is used widely and frequently as the first source of health information [Citation16]. Healthcare professionals are a trusted source of health information for many, yet they have a range of knowledge and self-efficacy regarding counseling patients on alcohol or nutrition recommendations [Citation17,Citation18]. For example, while the American Heart Association advises patients to discuss alcohol use with their physician [Citation19], few adult cancer survivors recall receiving information about alcohol use from a healthcare provider [Citation20].

Contradictory information, decisional conflict, and nutrition confusion

Obtaining health information from multiple sources or trying to incorporate information related to co-morbidities may lead to encounters with contradictory information (also called “conflicting” information [Citation21,Citation22]). Carpenter et al. [Citation23] define contradictory information as two-sided coverage where “two or more health-related propositions are logically inconsistent with one another” (p. 3). Contradictory information is often related to a single health issue; a more expansive conceptualization offered by Nagler [Citation22] considers contradictions between multiple health issues, such as when messages indicate that a single behavior can produce two different outcomes This may lead to uncertainty about what behavior to choose, negatively affect the credibility of the message source, and reduce behavior change intentions [Citation24,Citation25]. For example, conflicting recommendations about mammography decreased the uptake of breast cancer screening and future intentions to screen [Citation26]. Understanding how users perceive contradictory information can inform the effective delivery of health messages.

When it comes to nutrition communication, confusion is not new. The 1980 Dietary Guidelines’ advice to limit butter prompted a shift towards margarine, yet was followed in the 2000s by another shift away from margarine because of trans fats [Citation27]. Nutrition confusion is equally easily found in the context of complex findings around alcohol use and health. It becomes unclear how best to manage health when balancing potential cancer outcomes (e.g. heavy drinking related to cancer mortality) vs. heart health (e.g. some positive effects of light to moderate alcohol use for cardiovascular outcomes) [Citation28–30].

Although the evidence for the impact of nutrition confusion is mixed, nutrition confusion is not without consequences. Both nutrition confusion (e.g. perceived ambiguity about nutrition information) and related nutrition backlash (e.g. negative feelings toward nutrition recommendations and research) are negatively associated with intentions to follow nutrition recommendations [Citation22,Citation31,Citation32]. Yet other findings indicate that contradictory dietary information does not affect self-efficacy or motivation to make changes to dietary intake [Citation33]. Thus, exploring perceptions of nutrition recommendations remains important for researchers working to raise awareness of the nutrition – cancer link. Furthermore, the importance of taking a translational approach to understand how the nuances involved in the way information presented may impact perceptions is paramount. As Krieger and colleagues [Citation34] indicate “communication has a long tradition of generating theory, rigorously testing theoretically-informed ideas, and then translating findings into information that can be used to solve practical problems” (p. 33).

Study purpose and research question

The purpose of this study was to explore how nutrition risk factors for CRC prevention were perceived by rural adults participating in the brief intervention and message design stage of a larger study aiming to promote CRC screening. The brief intervention focuses solely on activating nutrition-based risk perceptions as we were interested in providing specific, clear, and actionable messages about one type of behavior (avoid/reduce consumption) to activate cancer risk perceptions and promote a primary type of protective behavior (CRC screening). This study contributes to understanding how nutrition risk messages in the context of colorectal cancer are presented and perceived. We highlight how to plan for context when delivering messages – in this case, potentially contradictory messages. Given the low awareness of the nutrition – cancer link among the general public and the fact that nutrition guidelines vary by health condition, there is a need to understand how message recipients perceive and respond to context-specific nutrition messages. Our study explored the following research question: What are rural adults’ perceptions of nutrition risk messages for CRC prevention delivered by a virtual health assistant (VHA)?

Methods

This analysis was part of a larger study that engaged rural adults in a community-engaged process to design and develop a web-based nutrition risk module centered around CRC prevention. The goal of the overall module was to communicate information about nutritional risks related to CRC and to promote CRC screening options, including a home-based stool test. During the development of this risk module, researchers focused largely on understanding cultural expectations and preferences related to communication surrounding food and cancer prevention. Researchers also sought feedback and suggestions from users regarding how to present nutrition risk information to be understandable, acceptable, and actionable (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04192071). During this initial process, insights related to contradictory information and message resistance among users testing the module prompted us to conduct an exploratory analysis of how users were responding to CRC avoidance guidelines and how those guidelines may conflict and compete with other sources of information.

Recruitment

Participants were recruited through several approaches. We began by using the University of Florida’s HealthStreet community engagement program to identify eligible participants; most of those recruited in this way participated in the first two focus groups, held in-person at the start of the study period. We used another university resource, the Integrated Data Repository, to identify and contact potentially eligible participants who had previously asked to be notified of relevant research studies. Flyers were placed in the surrounding community, but because the research protocol was moved from in-person to remote (e.g. Zoom) data collection in March 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, flyers were not the main recruitment strategy. For inclusion in the study, participants had to be between 45 and 73 years old, be able to read or write in English, and self-identify as Black/African American or White. After the switch to remote data collection, these initial inclusion criteria were expanded to include having access to virtual video conferencing software (Zoom). A member of the research team contacted eligible participants by phone and/or email using standardized messages, approved by the institutional review board (IRB), to assess eligibility and schedule data collection.

Data collection and script development

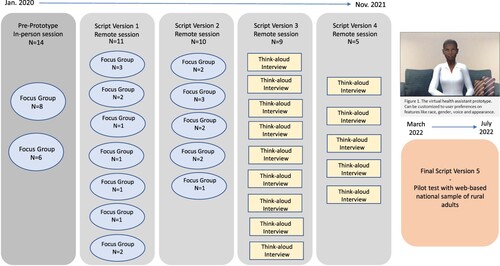

All protocols were approved by an IRB and a Safety Review and Monitoring Committee. Data collection occurred between January 2020 and November 2021. Participants provided informed consent before participating. Two focus groups (in-person) were followed by several online focus groups, and then a series of online individual think-aloud interviews [Citation35] (Figure ). Each session lasted 60–90 min and was audio-recorded. During focus groups 1 and 2, participants completed photo sorting and storyboard activities to brainstorm preferred images and messages. Participants then viewed a brief clip of a VHA describing how to screen for CRC (created for the parent study), then participated in a moderated discussion. All subsequent participants interacted with the current version of the VHA prototype then participated in a moderated discussion of their experience and completed a questionnaire [Citation35].

Figure 1. The virtual health assistant prototype. Can be customized to user preferences on features like race, gender, voice and appearance.

Moderator notes facilitated an iterative process of updating the VHA scripted content, including nutrition messages (Appendix). Informed by Construal Level Theory (CLT), the script was primarily developed with considerations for temporal framing (e.g. short-term vs. long-term or day vs. year). However, the multiple messages delivered in the approximately 12-minute script employed several message features informed by existing literature (gain vs. loss frame, repetition, intention formation prompt, and optional message branches). Based on CLT, and existing research, we conceptualized that among adults consuming any of the nutrition risk foods discussed by the VHA, messages about dietary patterns linked to cancer would invoke the immediacy of colorectal cancer risk (proximal threat), making individuals less likely to discount a theoretical future cancer risk. A meta-analysis of the persuasive impact of temporal frames found that present-oriented health messages were significantly more persuasive than future-oriented health messages, showing a positive effect on intentions [Citation36].

Data analysis

Transcripts were managed using NVivo version 12. An initial transcript review prompted an exploratory analysis of comments about the intervention’s nutrition messages. Three members of the research team drafted a codebook to systematically explore this data. Based on transcript review and existing literature on competing and contradictory nutrition messages, we created operational and conceptual definitions and updated these via iterative coding and review of inter-rater reliability. The final codebook included themes related to perceptions of the nutrition messages. All transcripts were coded by one or more of the three-member coding team and reviewed weekly until all transcripts were coded. When necessary, subthemes were defined and previously coded data from the parent theme was re-coded.

Results

Participants

Overall, 48 men and women between 50 and 73 years old participated in a one-time focus group or think-aloud interview. Participants self-identified as non-Hispanic Black (65%) or non-Hispanic White (35%) in addition to self-identifying as men or women and participated in race and gender-stratified focus groups or were asked to participate in the individual think-aloud interviews. All of them self-reported having health insurance. Participant characteristics are presented in Table .

Table 1. Participant demographics.

Inter-rater reliability

We conducted an iterative process to establish acceptable coding schemes to reduce coding errors. Establishing acceptable inter-rater reliability consisted of multiple rounds of coding, which included reviewing coding discrepancies on 20% of transcripts and pulling out codes for negative case analysis (codes that indicate the opposite of the theme as a process of refining and confirming the patterns emerging from analysis; see [Citation37]). All themes had a percent agreement higher than 97% and a weighted kappa score greater than .75, indicating sufficient agreement between coders [Citation38]. Percent agreement and Cohen’s kappa statistic scores indicate high agreement between coders and that the codebook was functioning well as a tool to aid data coding (Table ).

Table 2. Inter-rater reliability of all themes coded.

Overview

Three themes were coded about how participants perceived the tailored messages on nutrition risk and CRC prevention: contradictory recommendations, reactions to nutrition messages, and information gaps. These themes and related subthemes are defined in Table . Examples of the subthemes are detailed in Table .

Table 3. Themes, subthemes, and definitions.

Table 4. Expansion of major themes and subthemes.

Theme 1: Contradictory nutrition recommendations

Participants commented when they perceived that a specific recommendation made by the VHA contradicted a recommendation they had heard previously or had previous knowledge of. This general theme of contradictory information manifested itself in three distinct subthemes: contradicting health conditions, contradicting sources, and contradicting cultural or dietary preferences.

Contradicting health conditions

The first subtheme included comments referencing contradictory nutritional guidelines for different health conditions. Here, participants discussed the differences between nutrition recommendations for CRC prevention compared to nutrition recommendations for other health conditions. For example, “I’m aware that you have to be careful, but there’s a lot of reading that says a beer is good for the heart” (P651, BF, FG14, Prototype 2). Another participant mentioned, “Especially for women who are still having their menstrual cycles. They need heme iron, they need meat” (P8556, WW, FG4, Prototype 1).

When the recommendations for a health condition other than CRC conflicted with messages to avoid alcohol and processed meat and limit red meat, participants asked for clarification on how the recommendations fit into a broader context of health behaviors. One participant, P2948, described a conflict between red meat consumption in two health concerns (low iron and CRC) and identified her doctor as a message source. She specified that her doctor’s advice that liver consumption is good for low iron contradicted the VHA’s message to avoid red meat for CRC prevention. This overlap with conflicting health concerns leads to our next identified theme: contradicting sources.

Contradicting sources

A second way this theme manifested was in participants expressing uncertainty about managing several information sources providing contradictory nutritional information. This included instances when participants explicitly stated the source of the contradictory information. This source was often a clinician, who gave nutritional information that conflicted with the cancer prevention message delivered by the VHA.

I totally disagree with that because I’m aware of a doctor – Doctor [name], I don’t know if you ever heard of him or not, but … some of that information that the avatar was saying was not accurate … I don’t agree with it because I know better. (BM, TA10, Prototype 4)

Before you fall in behind [an online] article, you need to confirm it and see it in more than one written form or by somebody who’s very reputable. You can’t just believe what you’re reading when you go on the computer and it’s there. (P3267, BW, TA3, Prototype 3)

Contradicting cultural or dietary preferences

Finally, participants discussed how dietary patterns linked to cultural or normative ways of eating and drinking conflicted with cancer prevention recommendations. These instances occurred most often in the context of the message that “to prevent CRC it is best to avoid alcohol.” One participant commented, “Part of it is because I’m French, so I was raised on wine from a small child down, so I was a little surprised that drinking any wine, you know, would increase my chances of colorectal cancer” (P7930, WW, FG3, Prototype 1).

There was also concern that incorporating new dietary restrictions would be difficult, especially if they conflicted with current dietary intake patterns. Dietary modifications to meet the recommended guidelines were sometimes discussed as unattainable or in direct conflict with personal needs, like this participant’s description of always being hungry:

I have no choice actually, these people that want to cut out meat in our diets, they’ll kill me literally … because protein from plants, doesn’t be my nutrient. It doesn’t fill me up and I need to eat a lot of vegetables, but the eggs and the beef fill me up. Like I eat chicken, even chicken doesn’t fill me up. (P2729, WW, FG3, Prototype 1)

Theme 2: Reactions to nutrition messages

Participants had a diverse spectrum of reactions to the VHA’s nutrition risk messages, including aversion to prohibitive recommendations, appreciation, and desire for balance in the framing.

Aversion to prohibitive recommendations

In some cases, participants seemed to experience discomfort or react negatively when the VHA suggests avoiding alcoholic beverages to reduce the risk of CRC. Although the most pronounced reactions were in response to the “avoid alcohol” message, participants also indicated that the “limit red meat” and “avoid processed meat” recommendations were not what they were expecting. These recommendations to avoid or limit specific food/beverage items were described as “preachy” or “unrealistic.” In response to being told that the amount of alcohol they consumed was more than the amount recommended for CRC prevention, one participant responded:

The assistant seems rather harsh … when you go, “You shouldn’t drink at all, and you shouldn’t have any red meat” … I’m really not a big beer drinker. And it’s when I play tennis I have a beer, and now you’re making me feel guilty about this. I’m going to get colon cancer because I had one beer [a] week socializing with people? That’s a little bit harsh. Especially when later on … the assistant goes on to say, “Well, we really don’t know how many beers it takes for you to get cancer.” (P464, WM, TA2, prototype 3)

Participants expressed their discomfort in various ways, including shutting themselves off from new information. In one instance, when the moderator asked if any additional foods should be discussed in the intervention, one participant responded: “No. I don’t want to learn about any more foods that I like, and you want to remove them out of my life. I don’t want to know about it” (P7896, BM, FG10, Prototype 2). Additionally, some participants communicated doubts about message validity and negative impact on personal motivation to act on the advice:

To tell people you can’t consume any red meat or any processed meat, or you’re at high risk for cancer, for me, I would just discount [the advice]. If you’re telling me I have to eliminate it, okay, well I’ll just accept the fact that I’m a candidate or at risk for colon cancer. If there are grades of recommendations … it would be considered a more valid measure than just … “You can’t eat red meat, you can’t have processed foods, or you’re just at high risk for colon cancer.” (P5520, WM, FG8, Prototype 1)

Appreciation for guidance

Receiving the messages with skepticism, however, was not a universal reaction. Some participants expressed appreciation for a clear and consistent message that indicated the precise behavior they should take: “She complimented me on … not doing beef … but the alcohol she did come down. What I like is she didn’t play. I’m an absolute person. Okay so, she was definite that the alcohol needed to be stopped” (P651, BW, FG14, Prototype 2).

Another participant mentioned feeling okay, even positive, at the message to reduce alcohol:

Hmm. Now, that’s interesting, and then numbers that [the virtual agent] was giving me, when it came to the meat, I didn’t care what the numbers were, and what I’m supposed to eat. But when it came to the alcohol, and he said, reduce your level of drinks by one a week, that will help. There was some happiness in that, which is kind of odd. But I saw that more positive than reduce your meat intake. I don’t get it, but that’s where we’re at. (P2474, BM, TA13, Prototype 4)

The desire for a balance of risk messages and positive messages

Participants also suggested advising people to lessen, rather than eliminate items: “And maybe he could say, hey, what you know … try to reduce your alcohol consumption by one drink … without getting too prescriptive” (P8819, WM, FG9, Prototype 1). Perhaps related to participants’ sense that the guidance to eliminate alcohol, red meat, and processed meat was “extreme advice” (P3963, WM, TA5, Prototype 3), a recurring sentiment included wanting the VHA to give positive feedback. “We always want to hear positive things, you know … we always want positive reinforcement” (P7896, BM, FG10, Prototype 2). The fact that participants described the positive talk as “makes you feel good, right?” (P6000, BM, FG10, Prototype 2) suggests that positive reinforcement may help mitigate perceptions that the intervention’s nutrition messages are too negative or restrictive. “If somebody’s drinking one drink per week, they should be – you should be lauded” (P464, WM, TA2, prototype 3).

Theme 3: Information gaps

The overall theme of information gaps manifested in participants’ requests for additional information, specifically information not featured during their brief interaction with the VHA. Requests for additional information were grouped into three smaller groups by topic, which included requests for additional nutrition information, statistics and numbers, and screening information. (Although not all requests were incorporated into later iterations of the VHA intervention, the parent study’s research team did supplement the VHA-delivered intervention with optional access to a cancer prevention website created based on this feedback.)

Gaps in nutrition information

Participants expressed a desire for more information about the three nutrition risk factors for CRC introduced by the VHA. Specifically, when the VHA said that consumption of red meat, processed meat, and alcohol increased CRC risk, participants wanted details about variation in risk levels and “how much is too much” (P2, FG1, BF, pre-prototype).

How much less … less meat, less – I know it should be less – red meat, less alcohol as much is possible. But if you … if you choose to continue to eat red meat and drink alcohol, how much will be the lowest that would keep you … Yeah, well, lower the risk, the chance of getting cancer? (P9, FG1, BF, pre-prototype)

Participants also requested information about foods and drinks they could consume in addition to foods and beverages they should avoid. These requests included suggestions for protective dietary items that reduce CRC risk, like fiber, fruit, vegetables, and water. For instance, one participant said,

The whole app seems to be focused on the bad stuff for you. What about the good stuff? Like you’re leaving out the fiber, you know, broccoli and foods of that nature that can be good and can counteract some of the issues. (P5533, FG7, WM, Prototype 1)

Gaps in statistics and numbers

Some participants wanted to see statistical data describing the relationship between CRC risk and specific population demographics (e.g. gender, race). Participants also asked for visual representations of risk and graphs of the relationship between dietary intake and the number of diagnosed cancer cases. Details about how CRC risk might change at different levels of consumption and about dose-response relationships between consumption and incidence prompted questions about how much alcohol, red meat, and processed meat they could consume without increasing CRC risk. Participants indicated that statistics could help personalize the intervention: “It’s too general on the risk, you’re going to ask specifics of how often [you eat these items], I would suggest that you provide information on what is the increased risk for what I have provided” (P5520, WM, FG8, Prototype 1).

Gaps in screening information

Participants also expressed that the early scripts were too focused on nutrition to the exclusion of CRC screening information. Frequently requested information included the recommended screening age, the accuracy of various screening modalities, as well as guidance on how to choose a screening modality. “There’s a lot of [tests] floating around, and somebody could end up off in the weeds when they really should be on the highway to getting some help” (P6087, WM, FG6, Prototype 1). Visual representations of the colon were also discussed. In response to being asked if an image of a colon should be included in the intervention, one participant described how the use of visuals had facilitated their understanding during a recent healthcare visit. “Whenever the doctor would show us where the cancer was and explain to us … it helps, it helped [my dad] to have some idea of exactly what the doctor was talking about” (P8161, WW, FG4, Prototype 1). Although images were suggested, participants cautioned against elaborate visual aids and suggested using simple depictions in the intervention.

Discussion

This exploratory paper highlights considerations for delivering accessible and actionable cancer prevention messages via a novel message source (i.e. a virtual human/VHA). Rural adults shared their thoughts during real-time message testing of cancer risk messages. We describe three themes, and related subthemes, derived from a qualitative analysis of perceptions related to the nutrition – cancer link: (1) contradictory nutrition recommendations, (2) reactions to nutrition messages, and (3) information gaps. Supplementing existing research on contradictory nutrition messages [Citation22,Citation31,Citation39], which includes randomized designs and quantitative assessments, the current study takes a slightly different approach. Here (1) messages were co-developed with the priority population, (2) message perceptions are assessed iteratively, and (3) we use qualitative, in-depth analysis of narratively described perceptions (vs. Likert scales).

Theme 1: Contradictory nutrition recommendations

Given that nutrition recommendations vary by disease context, it is not altogether unexpected that participants would point out instances when the nutrition guidelines for cancer prevention were contradictory. In this study, we captured three domains within which the VHA-delivered messages contradicted other information: contradictions with other health conditions or concerns, contradictions between information sources, and contradictions with dietary preferences or cultural norms. In context with existing literature, we discuss implications for how contradictions in risk communication for behavior change may affect message recipients’ reactions (e.g. confusion) and perceptions of the credibility of the message.

Contradictions in risk communication: Confusion, negative beliefs, reactance

Participants identified several ways nutrition messages were contradictory or conflicting. Research indicates that exposure to conflicting nutritional information is linked with increased nutrition confusion (e.g. confusion about what foods to eat) and nutrition backlash (e.g. negative beliefs about nutrition research) [Citation31,Citation40] as well as reduced intentions to engage in healthy behaviors [Citation22]. For example, in the current study, some participants questioned if they should consume red meat, processed meat, and alcohol, despite having received the personally tailored, evidence-based nutrition guidelines.

Other studies have also documented nutrition confusion and backlash as negatively associated with cancer prevention behaviors like physical activity and dietary intake; however, the message source may be important. One study found that exposure to contradictory nutrition information via health websites or interpersonal communication produced lower backlash, while contradictory nutrition information received from healthcare professionals was associated with higher backlash [Citation32]. VHAs, as a novel source of information, are a promising means of providing consistent information to influence perceptions. However future research is needed to evaluate user responses (e.g. like backlash) to information delivered by VHA’s.

Psychological reactance (i.e. engaging in an admonished behavior or resisting an advocated behavior) as a means of restoring a sense of freedom and choice is another possible response to conflicting messages or contradictory information [Citation41]. Although we did not explicitly measure reactance in the current study, participant questions such as “How much meat can I eat and still be okay?” may signify an attempt to manage the threat of being told to avoid or limit certain foods. This insight is drawn in part from research findings that participants who receive threatening health messages may be motivated to manage the potential threat to freedom [Citation42]. Authors de Lemus et al. [Citation43] provide additional evidence that reactance can result from perceived threats to one’s groups, social identities, or cultural identities.

Contradictions in risk communication: Credibility

In the context of this project, establishing high message credibility was a key factor affecting motivation to implement the recommended behaviors. Source perceptions (e.g. how a message recipient perceives the source or communicator of the information) can shape opinions on credibility and trust as well as whether or not a recipient ultimately acts on a message [Citation44]. Some participants in the current study expressed skepticism about the information’s accuracy and credibility when told to avoid specific foods. Similarly, past research [Citation45] has found that perceptions of nutrition message accuracy increased perceptions of message credibility. Still, regarding conflicting health information, a longitudinal study found neither levels of trust nor literacy protected against carryover effects [Citation46]. Although previous research has found that VHAs can be a credible source of health information, credibility can change with context and should always be assessed [Citation47–49]. Thus, any intervention using nutrition recommendations to activate risk perceptions should be tested to ensure the messages are perceived as accurate and credible and that overall goals regarding screening or other risk-mitigating behaviors are not compromised.

Theme 2: Reactions to nutrition messages

A growing body of literature demonstrates the role of specific message cues and negative affect on successfully increasing risk perceptions [Citation50]. In the current study, receiving the message to eliminate foods that increase CRC risk overwhelmed some participants, especially those who were approaching the dietary intake recommendations or who already followed restrictive dietary guidelines for other health conditions. Some research indicates that reducing the receiver’s defensive processing of threatening messages may be necessary to achieve desired outcomes [Citation51,Citation52]. However, in terms of behavior change and risk perception, it may also be effective to elicit emotional reactions to nutrition guidelines, if a reasonable plan of action is made available to the message recipients as emotional states have implications on attitudes [Citation53]. Emotional arousal has been used as a strategy to motivate individuals to make and maintain behavior changes [Citation54]. Thus, with transparency and access to acceptable risk-reduction options, it may be ethical and practical to ignite low levels of risk perception to persuade adults to modify their health behaviors [Citation55].

Finally, participants suggested that the VHA should balance the nutrition risk messages with more positive messages. Rothman et al. [Citation56] indicate that the role of message frames on outcomes is complex, with evidence that gain frames (e.g. focusing on the benefits of adopting a behavior) work better for prevention behaviors such as avoiding alcohol, whereas loss frames (e.g. focusing on the costs of not adopting a behavior) work better for detection behaviors such as engaging in cancer screening. However, there is limited support to date for the impact of nutrition-specific message framing on intentions or behavior [Citation57,Citation58].

The Transtheoretical Model or Stages of Change (SOC) Model is a behavior change model with implications for the theme “reaction to nutrition messages”. The distinct groups (i.e. aversion, request for balance, and appreciation) seem to map onto this model, which has demonstrated positive outcomes for understanding eating behavior change processes [Citation59]. In the SOC, individuals move cyclically through six stages of change. Contemplation is the stage where individuals begin to recognize concerns about a behavior and start to weigh the pros and cons of making a change. This definition suggests participants requesting balanced messages may be in Contemplation and desire information that can help them decide what to do. DiClemete [Citation60] further supports this interpretation when he says “[t]he task for individuals in Contemplation is to resolve their decisional balance consideration in favor of change.” p. 29.

Furthermore, in the current study, participants seemed to prefer risk-reduction language combined with positive reinforcement for nutrition messages, further suggesting that a request for balanced messages is consistent with a strategy used for individuals in Contemplation. Also, self-efficacy is an important construct linked to longer-term dietary change [Citation61,Citation62], thus is a potentially important construct to test in the context of contradictory messaging delivered by a novel source. Future studies should consider delivering messages that successfully leverage emotional arousal, and consider how to effectively incorporate theoretically-informed processes of change into brief, digital interactions.

Theme 3: Information gaps

Participants identified several content areas with inadequate information, which we named information gaps. These gaps broadly covered the desire for more content on nutrition, colorectal screening, and statistics. However, the Ottawa Decision Support Framework indicates that both inadequate and excessive information can negatively affect decision-making in health contexts [Citation25,Citation63]. Thus, asking users about the “right amount” of information necessary to fill information gaps is important.

Surprisingly, none of the participants indicated that the length of the interaction was too long. While we took care to provide essential information, some messages, such as the importance of getting screened for colorectal cancer and remaining within guidelines were repeated in several portions of the interaction. Repetition as a strategy is consistent with previous research indicating that persuasive messages when repeated are more effective [Citation64].

Perhaps in an attempt to assuage negative feelings when advised to avoid specific foods, study participants requested more risk statistics and numerical representations of risk information. This study’s participants’ requests for additional statistics on “levels of risk” based on personal dietary intake may indicate a desire to reduce rather than eliminate intake of certain items. While an important part of the community-engaged and user-centered approach prioritizes meeting user needs, we proceeded with caution when adding statistics on nutrition risk outcomes. Previous research indicates that understanding numerical presentations of risk is a complex skill; nearly one-third of U.S. adults cannot perform basic math functions or process simple statistics or graphs [Citation65]. Thus, thoughtful approaches to effectively communicate numerical risk for health promotion are needed [Citation66].

Furthermore, communicators must be mindful when delivering cancer-related risk statistics for several reasons. First, numeracy, the ability to process and understand numerical health and risk information, can influence how people process and understand cancer risk information due to its impact on information seeking, and the ability to interpret and accept population risk data [Citation67,Citation68]. Alternatively, Han et al. [Citation69] indicate it may be helpful to visually represent risk, but some formats like dynamic, animated representations of risk may function better than other formats. They presented the dynamic, animated format as “9 individuals scattered randomly through an icon array of 100 persons, employing web animation to randomly change the placement of these 9 individuals every 2 s.” (p. 107). Finally, verbal sources of information (e.g. their physicians) may still be more trustworthy than numbers even when numeracy is high [Citation70]. Thus, when patients say, “My doctor told me it was okay,” it may be a clue that certain verbal advice is more persuasive and trustworthy than numbers.

Study limitations and future research

This study has several limitations. Due to the exploratory nature of the study, there was no opportunity to include probes to elicit more in-depth responses related to contradictory sources of nutrition information. Due to the iterative study design, participants responded to evolving messages adapted for each new round of data collection. Future research should further assess the relationship between personal dietary intake and message preferences for or against contradictory nutrition risk messages. Future studies should also seek to understand the role of temporal framing of nutrition messages delivered in virtual settings. Specifically, how do they function to promote cancer prevention behaviors across a range of audience types (variations in stage of change, self-efficacy, dietary patterns)? Using an audience segmentation approach to tailor information may be helpful, especially for those in “contemplation” who may need more information to decide to change.

Lessons learned from studies on correcting health misinformation contextualize the current study findings and might help guide message developers when health messages are potentially contradictory. Based on previous work [Citation71] correcting misinformation follows recommendations such as (1) correcting misinformation after exposure rather than as a warning before, and (2) focusing on why information is wrong and where it comes from (rather than why the new information is right and credible). Message design for contradictory nutrition information may also benefit from applying and testing these strategies. From a practical implication, as healthcare providers feel urgency and motivation to correct misinformation but lack professional, interpersonal, and institutional support in doing so, health information technologies may become essential to support and supplement challenges found in the healthcare system [Citation72].

Conclusion

Appropriate use of health information technologies could help bridge the gap between awareness of the nutrition – cancer link and engaging in cancer prevention behaviors for older rural adults at risk for CRC. We recommend that cancer prevention interventions bundled with nutrition recommendations consider the potential effects of contradictory and conflicting nutrition guidelines. We also suggest that when “filling” or “satisfying” information gaps, audience characteristics like the receiver’s ability to manage the information (e.g. numeracy skills) or readiness (e.g. stage of change) be considered. We suggest testing perceptions of message contradictions in the context of actual behavior change, intentions to change behavior, and self-efficacy to change behavior. Message testing and community-engaged approaches may help identify unanticipated outcomes of engagement with cancer prevention and nutrition risk messages in novel web-based contexts.

Ethics approval

All procedures were approved by the University of Florida institutional review board (IRB#201902537) and Scientific Review and Monitoring Committee (SRMC) OCR27722.

Acknowledgements

MJV, EB, TP, collected data, analyzed data, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. EJC and GM contributed meaningful contributions to the manuscript and critical comments to revised drafts. MZ and BCL advised on virtual human script development and code and contributed meaningful edits/comments to revised drafts of the manuscript. JLK contributed to data analysis and interpretation and provided key insights and critical comments and edits to revised drafts. JKL and MJV conceptualized the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Peacey V, Steptoe A, Davídsdóttir S, et al. Low levels of breast cancer risk awareness in young women: An international survey. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42(15):2585–2589. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2006.03.017

- Goding Sauer A, Fedewa SA, Bandi P, et al. Proportion of cancer cases and deaths attributable to alcohol consumption by US state, 2013-2016. Cancer Epidemiol. 2021;71(Pt A):101893), doi:10.1016/j.canep.2021.101893

- Vieira AR, Abar L, Chan DSM, et al. Foods and beverages and colorectal cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies, an update of the evidence of the WCRF-AICR continuous update project. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(8):1788–1802. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdx171

- Kiviniemi MT, Orom H, Hay JL, et al. Limitations in American adults’ awareness of and beliefs about alcohol as a risk factor for cancer. Prevent Med Rep. 2021;23:101433), doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2021.101433

- Wiseman KP, Klein WMP. Evaluating correlates of awareness of the association between drinking too much alcohol and cancer risk in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prevent. 2019;28(7):1195–1201. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-18-1010

- American Institute for cancer research. (2020). 2019 AICR Cancer risk awareness survey.

- Cole AM, Jackson JE, Doescher M. Colorectal cancer screening disparities for rural minorities in the United States. J Prim Care Commun Health. 2013;4(2):106–111. doi:10.1177/2150131912463244

- Zahnd WE, Murphy C, Knoll M, et al. The intersection of rural residence and minority race/ethnicity in cancer disparities in the United States. Intern J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(1384):1384–26. doi:10.3390/ijerph18041384

- Gapstur SM, Bandera Ev, Jernigan DH, et al. Alcohol and cancer: existing knowledge and evidence gaps across the cancer continuum. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prevent. 2022;31(1):5–10. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-21-0934

- White MJ, Perrin AJ, Caren N, et al. Back in the Day: nostalgia frames rural residents’ perspectives on diet and physical activity. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2020;52(2):126–133. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2019.05.601

- Clinton SK, Giovannucci EL, Hursting SD. The world cancer research fund/American institute for cancer research third expert report on diet, nutrition, physical activity, and cancer: impact and future directions. J Nutr. 2020;150(4):663–671. doi:10.1093/jn/nxz268

- USDA, U.S. Department of Agriculture, & U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2020). Dietary guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. DietaryGuidelines.gov.

- Agarwal DP. Cardioprotective effects of light-moderate consumption of alcohol: a review of putative mechanisms. Alcohol Alcoholism. 2002;37(5):409–415. doi:10.1093/alcalc/37.5.409

- Haseeb S, Alexander B, Baranchuk A, et al. Wine and cardiovascular health. Circulation. 2017;136:1434–1448. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030387

- Koppes LLJ, Dekker JM, Hendriks HFJ, et al. Moderate alcohol consumption lowers the risk of type 2 diabetes. Diab Care. 2005;28(3):719–725. doi:10.2337/diacare.28.3.719

- Jackson I, Osaghae I, Ananaba N, et al. Sources of health information among U.S. cancer survivors: results from the health information national trends survey (HINTS). AIMS Public Health. 2020;7(2):363–379. doi:10.3934/publichealth.2020031

- Khandelwal S, Zemore SE, Hemmerling A. Nutrition education in internal medicine residency programs and predictors of residents’ dietary counseling practices. JMed Educ Curric Develop. 2018;5:238212051876336), doi:10.1177/2382120518763360

- Smith S, Seeholzer EL, Gullett H, et al. Primary care residents' knowledge, attitudes, self-efficacy, and perceived professional norms regarding obesity, nutrition, and physical activity counseling. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7(3):388–394. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-14-00710.1

- Szmitko PE, Verma S. Red wine and your heart. Circulation. 2005;111(2):e10–e11. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000151608.29217.62

- Eng L, Pringle D, Su J, et al. Patterns, perceptions and their association with changes in alcohol consumption in cancer survivors. Eur J Cancer Care. 2019;28(1):e12933), doi:10.1111/ecc.12933

- Ihekweazu C. Is coffee the cause or the cure? Conflicting nutrition messages in two decades of online new york times' nutrition news coverage. Health Commun. 2023;38(2):260–274. doi:10.1080/10410236.2021.1950291

- Nagler RH. Adverse outcomes associated with media exposure to contradictory nutrition messages. J Health Commun. 2014;19(1):24–40. doi:10.1080/10810730.2013.798384

- Carpenter DM, Geryk LL, Chen AT, et al. Conflicting health information: a critical research need. Health Expect. 2016;19(6):1173–1182. doi:10.1111/hex.12438

- Chang C. Motivated processing. Sci Commun. 2015;37(5):602–634. doi:10.1177/1075547015597914

- Hoefel L, O’Connor AM, Lewis KB, et al. 20th anniversary update of the Ottawa decision support framework part 1: A systematic review of the decisional needs of people making health or social decisions. Med Decision Mak. 2020;40(5):555–581. doi:10.1177/0272989X20936209

- Han PKJ, Kobrin SC, Klein WMP, et al. Perceived ambiguity about screening mammography recommendations: association with future mammography uptake and perceptions. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prevent. 2007;16(3):458–466. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0533

- Goldberg JP, Sliwa SA. Communicating actionable nutrition messages: challenges and opportunities. Proc Nutr Soc. 2011;70(1):26–37. doi:10.1017/S0029665110004714

- Cai S, Li Y, Ding Y, et al. Alcohol drinking and the risk of colorectal cancer death. Eur J Cancer Prevent. 2014;23(6):532–539. doi:10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000076

- Piano MR. Alcohol’s effects on the cardiovascular system. Alcohol Res Curr Rev. 2017;38(2):219.

- Ronksley PE, Brien SE, Turner BJ, et al. Association of alcohol consumption with selected cardiovascular disease outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2011;342(7795):d671), doi:10.1136/bmj.d671

- Lee CJ, Nagler RH, Wang N. Source-specific exposure to contradictory nutrition information: documenting prevalence and effects on adverse cognitive and behavioral outcomes. Health Commun. 2018;33(4):453–461. doi:10.1080/10410236.2016.1278495

- Vijaykumar S, McNeill A, Simpson J. Associations between conflicting nutrition information, nutrition confusion and backlash among consumers in the UK. Public Health Nutr. 2021;24(5):914–923. doi:10.1017/S1368980021000124

- Wei Lin Leung V, Krumrei-Mancuso EJ, Trammell J. The effects of conflicting dietary information on dieting self-efficacy and motivation. Psi Chi Journal of Psychological Research. 2019;24(4):246–254. doi:10.24839/2325-7342.JN24.4.246

- Krieger, J. L., Lee, D., Vilaro, M. J., Wilson-Howard, D., Raisa, A., & Addie, Y. O. (2022). Research translation, dissemination, and implementation. In T. L. Thompson & N. G. Harrington (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of health communication (3rd ed). Routledge.

- Ericsson KA, Simon HA. How to study thinking in everyday life: contrasting think-aloud protocols With descriptions and explanations of thinking. Cult Activ. 1998;5(3):178–186. doi:10.1207/s15327884mca0503_3

- Wang Y, Thier K, Lee S, et al. Persuasive effects of temporal framing in health messaging: A meta-analysis. Health Communication. 2023.

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 1985.

- Campbell JL, Quincy C, Osserman J, et al. Coding in-depth semistructured interviews: Problems of unitization and intercoder reliability and agreement. Soc Method Res. 2013;42(3):294–320. doi:10.1177/0049124113500475

- Zimbres TM, Bell RA, Miller LMS, et al. When media health stories conflict: test of the contradictory health information processing (CHIP) model. . J Health Commun. 2021;26(7):460–472. doi:10.1080/10810730.2021.1950239

- Clark D, Nagler RH, Niederdeppe J. Confusion and nutritional backlash from news media exposure to contradictory information about carbohydrates and dietary fats. Public Health Nutr. 2019;22(18):3336–3348. doi:10.1017/S1368980019002866

- Reynolds-Tylus T. Psychological reactance and persuasive health communication: A review of the literature. Front Commun. 2019;4(56):1–12.

- Steindl, C., Jonas, E., Sittenthaler, S., Traut-Mattausch, E., & Greenberg, J. (2015). Understanding psychological reactance: New developments and findings. In Zeitschrift fur psychologie/Journal of psychology (Vol. 223, issue 4), pp. 205–214. Hogrefe Publishing.

- de Lemus S, Bukowski M, Spears R, et al. Reactance to (or acceptance of) stereotypes. Zeitschrift Für Psychologie. 2015;223(4):236), doi:10.1027/2151-2604/a000225

- Hocevar KP, Metzger M, Flanagin AJ, et al. Oxford research encyclopedia of communication. Oxford Res Encycl Commun. 2017.

- Jung EH, Walsh-Childers K, Kim HS. Factors influencing the perceived credibility of diet-nutrition information web sites. Comput Hum Behav. 2016;58:37–47. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.11.044

- Nagler RH, Vogel RI, Rothman AJ, et al. Vulnerability to the effects of conflicting health information: testing the moderating roles of trust in news media and research literacy. Health Educ Behav. 2023;50(0):224–233. doi:10.1177/10901981221110832

- Cooks EJ, Cooks EJ, Duke KA, et al. Telehealth and racial disparities in colorectal cancer screening: A pilot study of how virtual clinician characteristics influence screening intentions. J Clin Transl Sci. 2022;6(1):e48), doi:10.1017/cts.2022.386

- Olafsson, S., O’Leary, T. K., & Bickmore, T. W. (2020). Motivating health behavior change with humorous virtual agents, 1–8.

- Vilaro MJ, Wilson-Howard DS, Zalake MS, et al. Key changes to improve social presence of a virtual health assistant promoting colorectal cancer screening informed by a technology acceptance model. BMC Med Inform Decision Mak. 2021;21(196):1–9.

- Qin, Y., Chen, J., Namkoong, K., Ledford, V., Jungkyu, &, & Lim, R. (2022). Increasing perceived risk of opioid misuse: The effects of concrete language and image. Health Commun, 37(4), 425–437. doi:10.1080/10410236.2020.1846323

- Iles IA, Gillman AS, Ferrer RA, et al. Self-affirmation inductions to reduce defensive processing of threatening health risk information. Psychol Health. 2022;37(10):1287–1308. doi:10.1080/08870446.2021.1945060

- Smith SG, Kobayashi LC, Wolf MS, et al. The associations between objective numeracy and colorectal cancer screening knowledge, attitudes and defensive processing in a deprived community sample. J Health Psychol. 2016;21(8):1665–1675. doi:10.1177/1359105314560919

- Nabi RL, Green MC. The role of a narrative’s emotional flow in promoting persuasive outcomes. Media Psychol. 2015;18(2):137–162. doi:10.1080/15213269.2014.912585

- Lane RD, Ryan L, Nadel L, et al. Memory reconsolidation, emotional arousal, and the process of change in psychotherapy: New insights from brain science. Behav Brain Sci. 2015;38:e1), doi:10.1017/S0140525X14000041

- Oxman AD, Fretheim A, Lewin S, et al. Health communication in and out of public health emergencies: to persuade or to inform? Health Res Policy Syst. 2022;20(1):1–9. doi:10.1186/s12961-022-00828-z

- Rothman AJ, Bartels RD, Wlaschin J, et al. The strategic use of gain- and loss-framed messages to promote healthy behavior: How theory Can inform practice. J Commun. 2006;56(suppl_1):S202–S220. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00290.x

- Bannon K, Schwartz MB. Impact of nutrition messages on children’s food choice: pilot study. Appetite. 2006;46(2):124–129. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2005.10.009

- Brug J, Ruiter RAC, van Assema P. The (IR)relevance of framing nutrition education messages. Nutr Health. 2003;17(1):9–20. doi:10.1177/026010600301700102

- Prochaska JO, di Clemente CC. Transtheoretical therapy: toward a more integrative model of change. Psychother Theory Res Pract. 1982;19(3):276–288. doi:10.1037/h0088437

- DiClemete CC. Addiction and change: How addictions develop and addicted people recover. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; 2018; https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2017-40890-000.

- Burke V, Beilin L, Cutt HE, et al. Moderators and mediators of behaviour change in a lifestyle program for treated hypertensives: a randomized controlled trial (ADAPT) on JSTOR. Health Educ Res. 2008;23(4):583–591. doi:10.1093/her/cym047. https://www.jstor.org/stable/45110475.

- Vilaro MJ, Staub D, Xu C, et al. Theory-Based interventions for long-term adherence to improvements in diet quality. Amer J Lifestyle Med. 2016;10; doi:10.1177/1559827616661690

- Misra S, Stokols D. Psychological and health outcomes of perceived information overload. Environ Behav. 2012;44(6):737–759. doi:10.1177/0013916511404408

- Suka M, Yamauchi T, Yanagisawa H. Persuasive messages can be more effective when repeated: A comparative survey assessing a message to seek help for depression among Japanese adults. Patient Educ Counsel. 2020;103(4):811–818. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2019.11.008

- Mamedova, S., & Pawlowski, E.. (2013). Adult numeracy in the United States. Data point. NCES 2020-025. National Center for Education Statistics.

- Ancker JS, Benda NC, Sharma MM, et al. Taxonomies for synthesizing the evidence on communicating numbers in health: goals, format, and structure. Risk Anal. 2022.

- Gurmankin AD, Baron J, Armstrong K. Intended message versus message received in hypothetical physician risk communications: exploring the Gap. Risk Anal. 2004;24(5):1337–1347. doi:10.1111/j.0272-4332.2004.00530.x

- Lipkus IM, Peters E. Understanding the role of numeracy in health: proposed theoretical framework and practical insights. Health Educ Behav. 2009;36(6):1065–1081. doi:10.1177/1090198109341533

- Han PKJ, Klein WMP, Killam B, et al. Representing randomness in the communication of individualized cancer risk estimates: effects on cancer risk perceptions, worry, and subjective uncertainty about risk. Patient Educ Counsel. 2012;86(1):106–113. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2011.01.033

- Reyna VF, Nelson WL, Han PK, et al. How numeracy influences risk comprehension and medical decision making. Psychol Bullet. 2009;135(6):943–973. doi:10.1037/a0017327

- Walter N, Murphy ST. How to unring the bell: A meta-analytic approach to correction of misinformation. Commun Monogr. 2018;85(3):423–441. doi:10.1080/03637751.2018.1467564

- Bautista JR, Zhang Y, Gwizdka J. Healthcare professionals’ acts of correcting health misinformation on social media. Intern J Med Inform. 2021;148; doi:10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2021.104375