ABSTRACT

Inspired by recent media exposés of the unsustainable investment practices by philanthropic foundations with high-profile climate and environmental mission work, this commentary addresses the under-researched topics of philanthropic foundations’ identity as financial actors and their role in shaping the (sustainable) financial agenda. Philanthropy is commonly regarded as mission actors in the climate space, but its roles and power as asset owners are often overlooked, resulting in a lack of academic research or regulatory scrutiny on the sustainability impact of their investment strategies and practices. The commentary proposes ‘hybridity’ as an appropriate framework to understand philanthropic foundations’ unique position as both financial and mission actors. We propose four dimensions to assessing hybridity: network, policy, strategy and outcome. Foundations seeking to maximise their climate impact should aim to integrate their mission and investment along these dimensions. Similarly, these four dimensions provide a guideline for more comprehensive research and scrutiny of the impact of foundations on climate action. Finally, as businesses and financial institutions seek to integrate climate, biodiversity and other sustainability concerns into their day-to-day operations, we call for the wider adoption of ‘hybridity’ thinking in understanding the key opportunities and hurdles for private sector actors to achieve traditional business and sustainability objectives.

JEL:

1. INTRODUCTION

In December 2019, investigative journalism uncovered that philanthropic foundations supporting climate action are still invested in fossil fuels (Williams, Citation2019). Almost a year later, The Guardian reveals that Prince William’s Royal Foundation continues to invest in a fund that owns shares in the environmentally controversial palm oil sector, despite the foundation’s strong environmental advocacy (Davies, Citation2022). This glaring incoherence prompts critical examination, with existing literature explaining that such disparities may be attributable to philanthropy’s tendency of ‘deliberate ineffectiveness’ (McGoey, Citation2015) – a mechanism to perpetuate the fossil-dependent status quo to justify its own existence. Upon closer inspection, it further reveals two unresearched and under-theorised topics in the literature of sustainable finance and philanthropy.

First, the exposé portrays philanthropic foundations as financial actors, an identity that is often overlooked. Philanthropy features in the climate governance literature as part of the ‘polycentric’ governance structure (Jordan et al., Citation2018), but this literature focuses on philanthropy as mission actors that drive particular climate priorities by providing financial or other resources to support areas where governments funding and private sector investment fall short, often with little to no expectations of financial returns (Association of Charitable Foundations, Citation2017; Wood & Hagerman, Citation2010). Similarly, critical literature focuses on philanthropy’s unchecked agenda-setting power in public policy, including in the climate realm (Monier, Citation2023; Morena, Citation2016; Reich, Citation2018). There is a growing literature on how philanthropy can deploy impact investing to drive change (Fritz & von Schnurbein, Citation2015; Qu & Osili, Citation2017; Zolfaghari & Hand, Citation2021), but none as yet, to the best of our knowledge, has assessed the aggregate climate impact of philanthropy by studying both its investment and mission work in tandem.

Second, the exposé depicts philanthropic foundations as hybrid actors. Most philanthropy encompasses a mission arm, which provides grants and coordinates high public-profile charity work, including climate action, and an endowment arm, which is responsible for investing the foundation’s assets to enable operation in perpetuity (Smith & Shawky, Citation2013). Despite the growing literature on ‘philanthrocapitalism’ focusing on the processes and outcomes of the gradual infiltration and domination of capital market logic on philanthropic missions (Mitchell & Sparke, Citation2016; Stolz & Lai, Citation2018), this inherent hybridity of philanthropy is often overlooked. The convergence or divergence of these functions can result in uneven climate impacts on the financial system and the real economy.

In this commentary, we draw attention to the overlooked ‘hybridity’ of philanthropy as both mission and financial actors. We highlight the importance of critically engaging with this hybridity concept. At the organisational level, it allows us to explain and evaluate how philanthropic organisations make sense of, manage and measure their climate impact. At the systems level, it allows us to define more comprehensively the roles of philanthropy in broader earth systems governance regimes (Burch et al., Citation2019). In doing so, it opens up for more productive conversations for imagining and establishing new frameworks for governing hybrid philanthropic functions in the climate debate and beyond.

2. ‘TIP OF THE ICEBERG’: THEORISING HYBRIDITY IN PHILANTHROPY

The emergence of ‘philanthrocapitalism’ at the turn of the century defines how philanthropy navigates the capital market in contemporary times (Bishop & Green, Citation2008; Eikenberry & Mirabella, Citation2018), which entails the influence and integration of neoliberal principles in the philanthropic sector in four key dimensions. First, powerful elite actors, such as wealthy individuals, families and large-scale corporations, seek to harness the logic of capital to deliver public goods, transforming traditional philanthropic ‘gifting’ into a market-driven process (Stolz & Lai, Citation2018). Second, they advocate for philanthrocapitalism as a more efficient way of achieving tangible, quantifiable social and financial ‘returns’ with their spending. Third, they seek to integrate market practices in philanthropic operations, relying on market-mediated mechanisms and competitive incentives to deliver social outcomes (Brooks & Kumar, Citation2023). Finally, this results in the heavy influence of elites in setting and delivering social agendas (Bishop & Green, Citation2015; Brooks & Kumar, Citation2023), leading to scholars critiquing the creation of new neoliberal market subjects, often co-opting vulnerable and marginalised communities to abide by and become reliant on market norms and mechanisms, thus perpetuating rather than solving social issues that philanthropy on the surface seeks to solve (Burns, Citation2019; Hay & Muller, Citation2014; Mitchell & Sparke, Citation2016).

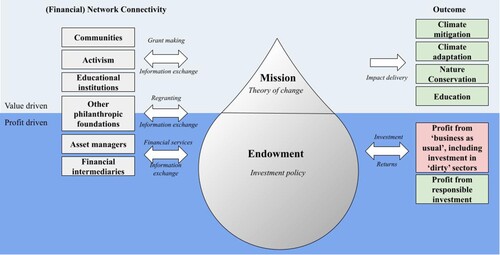

While the philanthrocapitalism literature captures and critiques the marketisation and financialisation of the philanthropic mission, it overlooks the fact that most philanthropic foundations have an invested endowment fund that actively participates in the capital market (, bottom half). To provide adequate financial support for philanthropic operations, the size of the endowment is necessarily larger than the mission budget. In the US, tax regulations dictate that private foundations can dedicate as little as 5% of their endowment assets to mission activities to enjoy their tax status. Estimating the size of philanthropic assets is notoriously difficult owing to divergent philanthropic regulations and disclosure requirements worldwide. Nonetheless, gleaning from multiple sources, total philanthropic assets from the most active markets are estimated to be US$1.5 trillion in 2018 (Johnson, Citation2018). Comparatively, the ClimateWorks Foundation estimated in 2020 that of US$750 billion of philanthropic giving globally, roughly US$6–10 billion was dedicated to climate change mitigation, suggesting that climate philanthropy only receives less than 2% of global philanthropic giving (ClimateWorks Foundation, Citation2021; Edge Funders Alliance, Citation2022). Thus, the hybridity of philanthropic foundations is uneven: mission only represents the ‘tip of the iceberg’ of the total financial power of a philanthropic organisation.

Figure 1. The metaphorical ‘iceberg’ of philanthropy.

Note: The tip of the iceberg represents the ‘mission’ function which typically enjoys a high public profile. The larger part of the iceberg submerged underwater represents the endowment that financially underpins the mission work. Mission and endowment are supported by distinctive activities (left hand side). Colour-coding of the intended outcomes depicts complementary (green) or contradictory (red) climate impacts (right hand side).

In the context of assessing the climate impact of philanthropy and its broader role in Earth systems governance regimes, it is insufficient only to appraise the impact of the climate mission (Nally & Taylor, Citation2015; Nisbet, Citation2018). Importantly, the financed emissions incurred by the endowment (or the foundation’s investments) must not exceed the emissions reduced or prevented as a result of the foundation’s climate mission, lest the mission work be completely undone. Some foundations are beginning to acknowledge the importance of managing their financed emissions. Using divestment commitment as a proxy, as of 2021, the latest available stocktake of the Divest–Invest Philanthropy initiative, signatories have increased from 17 in 2014 (representing US$1.8 billion assets under management [AUM]) when it was launched, to 200 (representing US$25 billion AUM) in 2019 (DivestInvest, Citation2020). This suggests that while there is growing awareness amongst philanthropic circles to responsibly invest in their endowment, the practice remains uncommon.

To make sense of this disconnection between philanthropic mission and investment, we borrow from the management scholarship its conceptualisation of ‘hybrid’ institutions, defined as institutions that combine institutional logics to tackle complex problems and achieve duality of outcomes, such as generating financial returns whilst achieving environmental sustainability (Haigh et al., Citation2015; Jay, Citation2013). Examples of hybrid organisations include impact investors, social enterprises, and universities (Pache & Santos, Citation2013; Upton & Warshaw, Citation2017). Strategies undertaken by hybrid institutions diverge and are often unconventional (Battilana & Dorado, Citation2010), leading to a plethora of outcomes ranging from unintended complementarities to paradoxical outcomes (Jay, Citation2013). To navigate this breadth and variety of hybrid institutional processes and outcomes, Gehringer (Citation2021) suggests four dimensions of institutional hybridity: (1) founding actor coalitions; (2) purpose and objectives; (3) organisational capabilities; and (4) the outputs of foundation work. The review finds that navigating between the welfare objectives of charities and the profit-making logic of their corporate donors – and the power imbalance of the actors championing these logics and practices – is challenging. However, successful manoeuvring of these conflicting rationalities can amplify the foundation’s mission across financial, corporate, social, and policy sectors. This typology resonates with the four dimensions of the philanthrocapitalism literature. The complementarities and tensions between the mission and endowment functions of philanthropy can be analysed by examining: (1) the integration of philanthropic and financial networks of actors; (2) the interface between mission ‘theory of change’ and endowment investment policy; (3) the different organisational logic, structure, and strategy in the mission and endowment arms; and (4) how philanthropic hybridity produces distinctive environmental, social and financial outcomes.

3. COMPLEMENTARITY AND CONFLICT: MISSION AND FINANCE ASPECTS OF PHILANTHROPIC FOUNDATIONS

We elaborate here on how these four dimensions of philanthropic hybridity can be analysed to assess the aggregate climate impact of a foundation, accounting comprehensively for the financed emissions of their endowed investment, as well as the contribution to emissions reduction, abatement and community resilience-building by its climate mission:

Network of actors: philanthropic foundations are connected simultaneously to the profit- (, bottom half) and value-driven sectors (, top half), giving them unmatched insights and influence on climate action through both activism/action and investment lenses. Foundations are thus well positioned to facilitate connectivity and break down sectoral silos, for example, in (re)channelling grants to relevant charities and communities, brokering public–private investment partnerships, or lead-by-example in spearheading innovative climate investment strategies. At the same time, climate groups may be unwittingly funded by returns generated by ‘dirty’ sectors such as oil and gas, putting them in a position to have to resolve the problem caused by its funders (, right-hand side). Network analysis can map out the full extent of philanthropic connections, while qualitative investigation can find evidence of mutual learning across the network to determine the full scale of philanthropic climate impact.

Policies: foundations have separate principles and policies governing the purpose and objectives of their mission and endowment (Smith & Shawky, Citation2013). Increasingly, foundations are adopting responsible investing policies to align their endowed investment with their mission (Impact Investing Institute, Citation2022; McClimon, Citation2022). Some foundations take a step further to spend significant proportions or the entirety of their endowment to urgently realise the foundation’s sustainability vision (Butler, Citation2023; Solomon, Citation2013). Analysis of philanthropy governing documents can shed light on evolving and divergent philanthropic policies in addressing climate change.

Strategy: informed by their policies, foundations can integrate their grant-making and investing functions to channel and scale investments towards climate action, especially in under-financed sectors and geographies. Falling short of integration, foundations can ensure their investment strategies are aligned with climate objectives, typically through fossil fuel divestment, stewardship and shareholder activism, and responsible investing (DivestInvest, Citation2021). Policy analysis can be triangulated with stakeholder interviews and observations, as well as triangulated with quantitative analysis of publicly available financial statements to compare and trace the flow of grant-making and investment towards climate action, clean and dirty sectors.

Outcome and impact: the positive (or negative) climate impact of a philanthropic foundation should not be judged solely upon their mission work, but also on the financial (e.g., changes to access to capital or investment norms) and environmental impacts (e.g., carbon emissions) of their investment (, right-hand side). An analysis of the way the different stakeholders see the impact of foundations through their grant-making and also their endowment would bring new light to the contested practices of impact evaluation.

4. EMBRACING HYBRIDITY: TOWARDS A RESEARCH AGENDA FOR UNDERSTANDING INSTITUTIONAL LOGICS AND PRACTICES IN THE ANTHROPOCENE

We call for greater research attention on philanthropic foundations as hybrid actors as society navigates the transition towards a more sustainable, low-carbon economy. The number of philanthropic foundations has expanded rapidly in the last two decades with 260,000 foundations operational globally (Johnson, Citation2018), making them increasingly prominent actors in contemporary international political economic regimes where the climate will play an increasingly prominent role. More importantly, as we have shown, philanthropic foundations occupy a unique, hybrid position across policy, financial and charity sector networks. Mobilised effectively with appropriate governance and oversight mechanisms, philanthropy has the potential to propel transformative changes by expanding the reach, amplifying the scale, and reforming the practices of the burgeoning ‘purpose ecosystem’ seeking to drive systems change in how the relationship between capital, society and nature should be governed (Dahlmann et al., Citation2020). Leveraging their hybrid nature, philanthropy can catalyse climate-positive investments, foster relations between ‘change agents’ and private sector actors, and exert influence to instigate much-needed mindset and economic systems change. However, unlike corporations and banks, philanthropic organisations often operate under discretion. Research, together with regulation and civil society scrutiny, can lift this veil of secrecy to hold this financially powerful and politically influential group of actors accountable. This is all the more crucial due to the fact that they do not hold any democratic mandate, which invites questions over their legitimacy to address social issues in the name of public interest (Maclean et al. Citation2021; Reich, Citation2018). To this end, we suggest three new research avenues.

First, at the organisational level, research on the role of philanthropy in climate action and sustainability more broadly should acknowledge and scrutinise philanthropic foundations as both mission and financial actors. Assessments of philanthropic contribution to climate action must account for the impact incurred from both the philanthropic mission and the endowed investment. Similarly, greater scrutiny is needed on how philanthropic organisations handle and govern the conflicting or synergistic logics between their mission and endowment arms (Battilana & Dorado, Citation2010).

Second, at the systems level, future research should pay greater attention to how foundations navigate and leverage their unique hybrid identities across public, private, and third sectors to drive (or hinder) transformative change in earth system governance systems (Burch et al., Citation2019). Research should critically reflect on the positionalities and purposes of philanthropy in climate governance regimes by scrutinising the representation and aspirations of philanthropy, investigating the political and environmental implications of philanthropic influence on the climate agenda, and proposing appropriate legal and regulatory framework to hold philanthropic influence accountable.

Finally, we believe there are transferable lessons on ‘hybridity’ to broader sustainable finance discourse. As financial institutions are increasingly engaging with climate and other sustainability-related risks and opportunities, ‘hybridity’ is a relevant concept in explaining how individual institutions and the sector collectively balance conflicting and synergistic business, climate, and other sustainability objectives. As we enter the Anthropocene where all entities must find ways to cope with irreversible environmental change, financial institutions should not be conceptualised as uniform entities, but rather as hybrid institutions, influenced by constantly evolving internal power dynamics, shifting priorities and escalating environmental risks. To this end, ‘hybridity’ is a suitable framework for explaining the uneven (or a lack of) progress in private sector-driven decarbonisation and net-positive climate outcomes, thus complementing existing critical geographical research on the topic with added institutional granularity over time and space.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful and constructive comments. We also thank the organisers and participants in the ‘Pathologies of Philanthropic Power: Transdisciplinary Perspectives and Emergent Issues’ workshop for their helpful feedback and constructive comments. Finally, we also thank the School of Geography and the Environment, University of Oxford, for hosting Anne Monier’s visit as this is where the two authors met.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

REFERENCES

- Association of Charitable Foundations. (2017). Firm foundations: Setting your grant-making strategy. Retrieved October 12, 2023, from https://www.acf.org.uk/common/Uploaded%20files/Research%20and%20resources/Resources/Funding%20practices/ACF140_Firm_Foundations_strategy.pdf

- Battilana, J., & Dorado, S. (2010). Building sustainable hybrid organizations: The case of commercial microfinance organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 53(6), 1419–1440. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.57318391

- Bishop, M., & Green, M. (2008). Philanthrocapitalism: How giving can save the world. Bloomsbury.

- Bishop, M., & Green, M. (2015). Philanthrocapitalism rising. Society, 52(6), 541–548.

- Brooks, S., & Kumar, A. (2023). Why the super-rich will not be saving the world: Philanthropy and ‘privatization creep’ in global development. Business & Society, 62(2), 223–228. https://doi.org/10.1177/00076503211053608

- Burch, S., Gupta, A., Inoue, C. Y., Kalfagianni, A., Persson, Å, Gerlak, A. K., Ishii, A., Patterson, J., Pickering, J., Scobie, M., & Van der Heijden, J. (2019). New directions in earth system governance research. Earth System Governance, 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esg.2019.100006

- Burns, R. (2019). New frontiers of philanthro-capitalism: Digital technologies and humanitarianism. Antipode, 51(4), 1101–1122. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12534

- Butler, P. (2023). UK charity foundation to abolish itself and give away £130 m. The Guardian. Retrieved October 12, 2023, from https://www.theguardian.com/society/2023/jul/11/uk-charity-foundation-to-abolish-itself-and-give-away-130m

- Climate Works Foundation. (2021). Funding trends 2022: Climate change mitigation philanthropy. Retrieved October 12, 2023, from https://www.climateworks.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/CWF_Funding_Trends_2021.pdf

- Dahlmann, F., Stubbs, W., Raven, R., & de Albuquerque, J. P. (2020). The ‘purpose ecosystem’: Emerging private sector actors in earth system governance. Earth System Governance, 4, 100053. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esg.2020.100053

- Davies, C. (2022). Prince William charity uses bank that is one of world’s biggest fossil fuel backers. The Guardian. Retrieved October 12, 2023, from https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2022/aug/19/prince-william-charity-royal-foundation-bank-jp-morgan-fossil-fuel-backers

- DivestInvest. (2020). Philanthropy need not sacrifice value for values. Retrieved 12 October 12, 2023, from https://divestinvest.org/philanthropy-need-not-sacrifice-value-values/

- DivestInvest. (2021). A decade towards just climate future. Retrieved October 12, 2023, from https://divestmentdatabase.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/DivestInvestReport2021.pdf

- Edge Funders Alliance. (2022). Beyond 2% From climate philanthropy to climate justice philanthropy. Retrieved October 12, 2023, from https://www.edgefunders.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Beyond-2-full-report.pdf

- Eikenberry, A., & Mirabella, R. (2018). Extreme philanthropy: Philanthrocapitalism, effective altruism, and the discourse of neoliberalism. PS: Political Science & Politics, 51(1), 43–47. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096517001378

- Fritz, T. M., & von Schnurbein, G. (2015). Nonprofit organizations as ideal type of socially responsible and impact investors. ACRN Oxford Journal of Finance and Risk Perspectives, 4(4), 129–145.

- Gehringer, T. (2021). Corporate foundations as hybrid organizations: A systematic review of literature. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 32(2), 257–275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-021-00318-w

- Haigh, N., Walker, J., Bacq, S., & Kickul, J. (2015). Hybrid organizations: Origins, strategies, impacts, and implications. California Management Review, 57(3), 5–12. https://doi.org/10.1525/cmr.2015.57.3.5

- Hay, I., & Muller, S. (2014). Questioning generosity in the golden age of philanthropy: Towards critical geographies of super-philanthropy. Progress in Human Geography, 38(5), 635–653. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132513500893

- Impact Investing Institute. (2022). Investing with impact in the endowment. https://www.impactinvest.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Investing-For-Impact-In-The-Endowment.pdf

- Jay, J. (2013). Navigating paradox as a mechanism of change and innovation in hybrid organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 56(1), 137–159. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.0772

- Johnson, P. D. (2018). Global philanthropy report: Perspectives on the global foundation sector. Retrieved October 12, 2023, from https://policycommons.net/artifacts/1847356/global-philanthropy-report/2593720/fragments/

- Jordan, A., Huitema, D., Van Asselt, H., & Forster, J. (Eds.). (2018). Governing climate change: Polycentricity in action? Cambridge University Press.

- Maclean, M., Harvey, C., Yang, R., & Mueller, F. (2021). Elite philanthropy in the United States and United Kingdom in the new age of inequalities. International Journal of Management Reviews, 23(3), 330–352. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12247

- McClimon. (2022). Foundations begin to Embrace ESG. Forbes. Retrieved October 12, 2023, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/timothyjmcclimon/2022/03/07/foundations-begin-to-embrace-esg/?sh=38e260e46440

- McGoey, L. (2015). No such thing as a free gift. Verso.

- Mitchell, K., & Sparke, M. (2016). The new Washington consensus: Millennial philanthropy and the making of global market subjects. Antipode, 48(3), 724–749. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12203

- Monier, A. (2023). The mobilization of the philanthropic sector for the climate: A new engagement? In J. J. Kassiola & T. W. Luke (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of environmental politics and theory (pp. 367–382). Springer.

- Morena, E. (2016). The price of climate action: Philanthropic foundations in the international climate debate. Springer.

- Nally, D., & Taylor, S. (2015). The politics of self-help: The Rockefeller Foundation, philanthropy and the ‘long’ green revolution. Political Geography, 49, 51–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2015.04.005

- Nisbet, M. C. (2018). Strategic philanthropy in the post-cap-and-trade years: Reviewing US climate and energy foundation funding. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 9(4), e524. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.524

- Pache, A. C., & Santos, F. (2013). Inside the hybrid organization: Selective coupling as a response to competing institutional logics. Academy of Management Journal, 56(4), 972–1001.

- Qu, H., & Osili, U. (2017). Beyond grantmaking: An investigation of program-related investments by US foundations. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 46(2), 305–329. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764016654281

- Reich, R. (2018). Just giving: Why philanthropy is failing democracy and how it can do better. Princeton University Press.

- Smith, D., & Shawky, H. (Eds.). (2013). Endowment and foundations funds, Chapter 17. Institutional Money Management, Wiley.

- Solomon, J. (2013). The mission of spending down. Candid Learning. Retrieved October 12, 2023, from https://learningforfunders.candid.org/content/blog/the-mission-of-spend-down/

- Stolz, D., & Lai, K. P. (2018). Philanthro-capitalism, social enterprises and global development. Financial Geography Working Paper, ISSN 2515-0111.

- Upton, S., & Warshaw, J. B. (2017). Evidence of hybrid institutional logics in the US public research university. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 39(1), 89–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2017.1254380

- Williams, T. (2019). Major climate funders are still invested in Fossil fuels. Why is That? Retrieved October 12, 2023, from https://www.insidephilanthropy.com/home/2019/12/19/major-climate-funders-are-still-invested-in-fossil-fuels-why-is-that

- Wood, D., & Hagerman, L. (2010). Mission investing and the philanthropic toolbox. Policy and Society, 29(3), 257–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polsoc.2010.07.005

- Zolfaghari, B., & Hand, G. (2021). Impact investing and philanthropic foundations: Strategies deployed when aligning fiduciary duty and social mission. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 13(2), 962–989.