ABSTRACT

The institutional and organisational fabric of the global asset management industry is the focus of this paper. Using a stylised version of four models of management evident in the global asset management industry, it is argued that rather than sharing tacit knowledge within and between investment managers hoarding and rent-seeking dominate the industry. It is also suggested that geography matters: realising value in the investment management industry is mediated by institutional frameworks, regulatory-settings, and the incentives driving those who may claim rents on their ‘magic sauce’. The reach and significance of these propositions are illustrated by reference to the Canadian banking industry, its pension fund clients and their peers in New York and Toronto.

1. INTRODUCTION

One of the defining features of the second half of the twentieth century was the ascendancy of finance and the asset management industry in particular (see Arjaliès et al., Citation2019; McKenzie, Citation2006). If global in scope, its’ home-base has been Anglo-American financial centres and, in particular, New York and London, whose significance has been sustained by digital technology and the near-instantaneous links within and between Asian, European and New York financial markets (Haberly et al., Citation2019). The geography of finance is hierarchical with (many) bank-based nodes that collect assets and liabilities, (fewer) nodes that switch assets and liabilities into and between financial markets and (even fewer) nodes that are the hubs for global trading and investment (see Wójcik et al., Citation2024).

At one level, the tentacles of global finance extend to regions, cities and localities. See, for example, Christophers (Citation2023) on the role of the global investment industry in shaping cities around the world illustrated, for example, by the provision of parking garages in downtown Chicago. At another level, finance disturbs and, in some cases, threatens country-specific regimes of accumulation thereby undercutting historically – and geographically – anchored political alliances and social contracts (Braun, Citation2021; Hall & Soskice, Citation2001). The imperatives driving the global financial services industry and the rise of Asian and Middle Eastern financial centres have undercut the vitality of bank-led regimes of accumulation and corporate governance in favour of market-driven asset management companies that dominate home markets (Bebchuk et al., Citation2017).

More generally, Anglo-American financial organisations and institutions have challenged jurisdictional-specific practices of ‘making’ finance – that is, the ways in which domestic financial institutions and organisations go about doing finance as a management and investment process. In this regard, the management practices of Anglo-American financial service companies are arguably as important for their global reach and for the threats posed by these companies to country-specific employment contracts and related economic and political commitments. These issues have been raised by commentators on international political economy who emphasise the costs and consequences of the hegemony of Anglo-American financial institutions for national and local practices (see Pistor, Citation2019).

There are many papers and books on the principles and practice of investment management. But there is less research in the social sciences on the nature of management models and processes in the industry, notwithstanding critical commentaries that emphasise the costs of the culture of finance (Morris & Vines, Citation2014), the perverse incentives on asset managers that can, in some cases, result in financial crises (Lo, Citation2019) and the challenges of regulating the industry at home and abroad (Bernanke, Citation2012). Here, a stylised model of management is used to bring to light some of the challenges and dilemmas facing asset management companies when reliant upon talented individuals and teams and the spatial implications thereof referencing Toronto and New York City. In doing so, this paper contributes to the growing literature in economic geography and beyond on rent extraction in the industry (Pažitka et al., Citation2022), the nature and scope of corporate learning in space and time (see Amin, Citation2003) and the evolution of financial ecosystems in time and space (see Leyshon, Citation2021).

The focus of this paper is upon the management of Anglo-American asset management firms and the factors that underpin the realisation of investment returns at home and abroad. Referencing Gertler (Citation2001, Citation2003), it is argued that tacit knowledge is an important ingredient in making investment returns. This depends, of course, upon context – understood here as the decision-making setting and the complex array of management and organisational factors that frame what is valuable and not so valuable in specific jurisdictions. Recognising that the global asset management industry is dominated by Wall Street, it is suggested that there are discernible geographical (institutional) differences in the culture of finance as illustrated by investment management practices in New York and Toronto.Footnote1

Whereas knowledge is often treated as the ‘property’ of industrial companies (see Hossain & List, Citation2012), in the investment industry the value of an asset manager and his/her team is often determined by their tacit knowledge (‘magic sauce’) albeit often shrouded from view and grudgingly shared with employers, senior executives and clients. In an era of ‘big data’ even ‘surplus data’, asset managers advertise their magic sauce as a crucial ingredient in ‘making’ investment returns out of the enormous volume and flows of information that threaten to overwhelm participants in global financial markets (see Halpern et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, it is argued that successful asset managers often hoard their magic sauce and, in doing so, aim to realise rents from clients and their host companies. If it could be replicated, its value would be readily discounted and/or lost (Laffont & Martimort, Citation2009).Footnote2

In the next section, the significance of financial intermediation is noted and is augmented in the Appendix in the supplemental data online by a schematic map of the global asset management industry emphasising the significance of US institutions. Whereas financial intermediation was dominated by banks and insurance companies for many years, these types of retail-facing organisations can be distinguished from asset management companies that invest the assets and liabilities of clients such as endowments, family offices, pension funds and sovereign wealth funds. In some Organization and Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, the banking sector dominated the finance industry in terms of assets-under-management (AuM) but this is changing as global financial networks envelope national institutions (Wójcik et al. Citation2022). In other countries, the asset management industry has overtaken banks and insurance companies – BlackRock, Fidelity, State Street Global Investors (SSGI) and Vanguard dominate Anglo-American financial markets along with smaller specialised investment firms (see Appendix in the supplemental data online and Lewellen & Lewellen, Citation2022).

This is followed by a model of the production of investment returns focusing upon key inputs to the production of risk-adjusted returns. It is noted throughout the paper that labour – asset managers – is a key ingredient in the production of investment returns. But the significance of this factor of production varies by asset class, investment strategy and market dynamics. It is also noted that technological innovation is an important factor of production (see Monk & Rook, Citation2020). At the same time, data science and technological innovation is an on-going ‘arms-race’ that cannot be conclusively won. Given the advantages and disadvantages of the nature, size and market context of financial institutions for the performance of asset managers, the penultimate section of the paper focuses upon competition between New York and Toronto for advantage in the deployment of Canadian financial assets.

At the heart of the paper are three sections on the hoarding of tacit knowledge.Footnote3 In the first instance, textbook accounts of the theory and practice of asset management are set aside in favour of asset-specific and/or market-specific knowledge (contra Litterman, Citation2004). Manuals, principles, and validated qualifications provide business schools and companies with a steady stream of willing employees. This type of codified knowledge is more often a pre-condition for entry to the industry rather than a reliable playbook for the real world of financial markets ‘drowning in data’ (Pourciau, Citation2022). It is argued that there is a premium on tacit knowledge or ‘magic sauce’ which is acquired by experience and learning-by-doing in circumstances that demand tradable insight as to the interplay of principles and practice (see Scheinkman, Citation2014). As shown here, this has implications for employment contracts.

A stylised account of the relationship between asset managers and their employers follows, emphasising the incentives for hoarding tacit knowledge notwithstanding the interests of senior executives in understanding the nature and scope of their asset managers’ ‘magic sauce’. At one level, investment companies employ asset managers to at least match if not outperform relevant market benchmarks. In doing so, they delegate responsibility for investment and defer to managers’ domain-specific expertise. Close oversight can prompt caution and/or investment strategies that converge time and again on average or below average performance. Day-to-day oversight by supervisors can also compromise the design and execution of managers’ investment strategies. In any event, to reveal one’s ‘magic sauce’ is to run the risk of losing market advantage and any premium on skills and expertise.

In the third section devoted to hoarding behaviour, the link between Gertler (Citation2001) and Gertler (Citation2003) is made plain by locating hoarding behaviour in country- and industry-contexts. Commentaries on the global financial services industry often focus upon the overarching logic of the industry without regard to how it is mediated and framed by country-specific institutions and regulations. When combined with arguments about the stability or otherwise of global financial markets the implication drawn is that the industry is much the same across the OECD countries and beyond. Nonetheless, there is a vibrant research programme on differences in legal and regulatory traditions, the forms and functions of financial organisations and corporate governance (see Pistor, Citation2019). This is briefly illustrated by reference to the structure of the Canadian asset management industry in relation to Wall Street.Footnote4

The research programme informing this paper can be traced to Clark and O’ Connor (Citation1997) who brought together knowledge of the process whereby markets set the price of gold and the ways in which institutional investors go about realising value from what is deemed, by many, to be an entirely transparent financial product. Having established networks of industry respondents and having grasped the importance of understanding how financial institutions organise themselves over space and time, this research has produced a series of publications which formalise industry-based principles and practices of financial companies and their jurisdictions. See Clark and Thrift (Citation2005) on how investment companies manage the investment process around the world on a 24-hour basis and Clark and Monk (Citation2017) on the management of investment performance of globally-focused pension funds.

The paper owes its insights to close dialogue with participants in the global asset management industry and draws upon academic research which relies upon fieldwork and engagement with investment firms (Clark, Citation1998; Wójcik, Citation2021). See also Hossain and List (Citation2012) on the value of ‘factory visits’ and Graham (Citation2022, p. 2037) who refers to the virtues of research in finance ‘grounded … in what skilled real-world practitioners actually do.’ Insights and experience are drawn from both sides of the market – from clients such as endowments and pension funds that rely upon the industry for investment returns and from the perspective of banks and asset management companies that compete for investment mandates in the context of market risk and uncertainty. In doing so, the paper advances a ‘way of thinking’ about the spatial foundations of the asset management industry rather than definitive conclusions backed by published data and econometric models.

The author has also had responsibilities on the buy-side of the market for investment returns serving as an adviser and board member in organisations that have long term investment mandates but, nonetheless, must negotiate repeated episodes of market volatility to realise their investment objectives. In doing so, it has been observed that contingency and happenstance dominate the practice of investment management, notwithstanding the existence of counterclaims that presuppose that theoretical principles are the benchmark from which to judge investment practice over time and space. In this regard, the author castes a critical eye over concepts such as the efficient markets hypothesis favouring a better understanding of what Arjaliès et al. (Citation2019) refer to as the ‘chains of finance’ or ‘how investment management is shaped’. Similar projects but from different perspectives are found in Scheinkman et al. (Citation2014) and Lo (Citation2019).

2. FORM AND FUNCTIONS OF FINANCE

Recognising the focus of this paper on asset management and the types of Anglo-American companies that dominate the sector, it is important to recognise that its twenty-first century form is both the product of banking and is a rejection of the management practices of banks and related organisations that, in many cases, seek to discount risk-taking or shift the costs of risk taking on to other organisations. There are large country-dominant banks that have significant asset management divisions (witness the Canadian case discussed in later sections of the paper). But these banks face significant challenges in being both nationally and regionally important deposit and lending institutions and global asset managers.

Banks were once privileged intermediaries in part because they were more efficient at collecting dispersed savings just as they were efficient at allocating savings to relevant opportunities in agriculture and industry. In doing so, banks were able to reap the benefits of geographical scope and organisational scale in ways that competing organisations like credit unions and mutual societies were not able to match. In some countries like Australia and Canada, the earliest banks were often sponsored by governments notwithstanding the existence of rudimentary bank-like entities and functions in larger provincial and capital cities (MacLean, Citation2013). Other countries, like the USA banks, collected and placed agricultural surpluses in manufacturing industries and major urban centres (like Chicago).

Banks were often stymied by the conservative ethos of the post-war era while those located in more liberal regulatory regimes embraced commercial activities and were more willing to leverage the short term in favour of long-term profit. Not surprisingly, the benefits associated with commercial lending prompted the development of bank-specific employment contracts that increasingly rewarded risk-taking. In some countries, such as the USA, however, retail banks remained hidebound by local regulations that focused upon ensuring the integrity of personal saving deposits. By contrast, in Australia and Canada provincial banks expanded nationally to take on both sets of activities with related but oftentimes competing internal compensation schemes. In Europe, governments have encouraged industry consolidation and the development of EU banking ‘champions’ that can rival Anglo-American institutions (to limited success).Footnote5

In the aftermath of the Second World War, commercial and government-sponsored banks thrived as economic growth and rising incomes provided opportunities to save and buy property. In response, the banking industry became increasingly segmented with some banks focusing upon retail consumers while other banks focused upon commercial activities including lending to companies for operating and investment purposes. In these circumstances, local managers often occupied a privileged position between savers and borrowers and were often rewarded for low rates of default and the extension of credit to desirable customers. However, as Leyshon et al. (Citation2004) and others have shown, over the 1970s and 1980s in the UK and elsewhere ‘relationship’ banking gave way to centralised management systems based upon client metrics, scores and the like.

The challenges facing banks are significant. In some jurisdictions, workplace pension schemes have produced enormous flows of assets that have bypassed savings banks in favour of commercial banks and providers that offer specialised financial services consistent with the needs of these types of organisations. Savings banks have also faced increasing competition in loans for the purchase of automobiles, homes and the like. As the discount rate declined over nearly 40 years, banks endured a long-term squeeze on profits; in response, retail-facing banks took on greater risks to realise premiums on forward commitments. The liberalisation of stock markets – nationally and globally – provided certain banks and non-bank financial like asset management companies opportunities to realise profits on stock selection and market movements. Asset management became profitable for banks but nonetheless risky given the rise of competing Anglo-American asset management firms (Lo, Citation2019).

In many countries, banks have asset management departments that also use contracts for services with related entities or independent asset managers. Fieldwork suggests that these banks do not compete with the big players in the asset management industry – they are unable to pay a premium for skilled employees, their investment strategies are relatively unsophisticated and the volumes of assets available for investment are modest given the economies of scale and scope that dominate the industry (Clark & Monk, Citation2017). In some countries more than others, large retail banks maintain asset management departments that compete with domestic and international asset managers (Australia, Canada, Germany, the Netherlands and the UK). Nonetheless, bulge-bracket asset managers like BlackRock dominate the global asset management industry along with specialised boutique and mid-sized companies that offer distinctive products and services (see Appendix in the supplemental data online).

While asset management services can be provided by various kinds of financial organisations, nation- and region-based banks, building societies and insurance companies have faced many challenges in matching the products and performance of the large and specialised Anglo-American asset management firms. Given the significance attributed here to the never-ending competition for assets under management (AuM), banks, insurance companies and similar organisations have sought opportunities that allow them to survive if not prosper against the burgeoning global asset management industry. Crucially, asset management companies are often different from banks even if their functions appear similar and even if they are sponsored and/or owned by banks – their significance is evident in research that emphasises the relationships within and between companies that constitute the global asset management industry (as illustrated by the penultimate section of this paper).

3. PRODUCTION OF INVESTMENT RETURNS

Whereas conventional theories of the firm seek as much as possible to represent production systems in terms of minimising the costs of risk and uncertainty, in this section and throughout the paper it is argued that risk management is an essential ingredient in the production of investment returns and is, in many cases, a means of distinguishing investment professionals, teams and whole companies, one from another. In doing so, I stress the importance of investment professionals and the context in which they apply their expertise and judgement.

Returns on assets-under-management are produced by combining labour, capital and technology in financial markets. Labour refers to asset managers and their teams, those that provide, internal and external to the company, the services needed to make investment returns and the senior managers and staff that orchestrate the production process and validate the integrity of reported results. Capital is just as complex and refers to the systems and infrastructure of the company as well as its interface with markets, the offices and trading centres of the company and the physical plant and equipment of the company. This could include, for example, an office complex in downtown Manhattan, a processing centre in New Jersey, and high-grade electronic networks and systems of management for the real-time monitoring of managers and markets across the globe.

Standard treatments of the asset management industry tend to focus upon standout managers. Reported investment returns depend upon knitting the process of production together in ways that anticipate and adapt to market movements while doing better or just as good as immediate competitors in translating risk-taking into better-than-average returns (Lo, Citation2019). It has also been noted that the stock of AuM is a key ingredient in the production process such that a relatively small stock of AuM can constrain or limit investment strategies whereas a large or very large stock of AuM can make the investment process cumbersome and unwieldly especially in situations where market movements are less predictable and may threaten current and future positions (Clark & Monk, Citation2017).

An investment product is a ‘unit’ that is offered to the market and its value depends upon its absolute performance and its performance relative to other similar products and asset classes. The electronic and print media regularly publish data on the performance of investment groups allowing clients and investors to compare providers’ investment performance over time. Large companies that produce investment returns on a wide variety of products are distinguished by their investment strategies, time horizons, geographies and risk and return profiles. There are, nonetheless, specialised companies that offer limited ranges of products justified by claims that specialisation produces, over the long-term, more robust and higher than average returns net of fees.

Asset management firms produce returns in public and private markets relying upon investment playbooks that are designed to realise the benefits associated with risk-taking while seeking, at every opportunity, to discount or manage the downside risks associated with their strategies. Some asset classes in some corners of the market are characterised as low-risk opportunities whereas, in other asset classes and segments of the market, risk arbitrage and management are essential elements of effective investment strategies. Trading in US government bonds is normally thought to involve relatively low risks notwithstanding arbitrage opportunities between governments and the impact of unexpected events on governments’ capacity to honour their commitments (witness the constraints imposed by indebtedness). By contrast, trading in emerging market debt is very risky and subject to unexpected shocks – uncertainty often dominates even if mediated by on-the-ground market knowledge.

Research suggests that investors’ risk appetites vary by age and gender, whether they trade on behalf of themselves or others, and whether their objective is to at least meet market benchmarks or outperform benchmarks in ways that attract notice and a premium on their endeavours (Sharpe, Citation2007). Meeting, time and again, market benchmarks is very challenging and is reliant upon computer trading systems based on pattern recognition software calibrated against recent events and market movements. In some cases, relying upon second-by-second and minute-by-minute market data is sufficient to trade daily and weekly on market indices. In these cases, company-based trading teams circumnavigate the world 24 h a day thereby realising clients’ objectives over the short- to medium-terms (Bauer et al., Citation2008).

To illustrate, assume an asset manager faces a rising market and must decide how to vary its equities portfolio to keep-up with the market if not go beyond market sentiment. One way forward would be to look backwards to similar events and incorporate current information into a forward-looking playbook. To keep up with the market requires anticipating other asset managers’ decision-making, changes in market sentiment and likely events that would either amplify or dampen a rising market. Sifting through data representing other managers’ trades and positions is one way of proceeding. Managers can also back their intuition, being mindful of the opportunity costs of converging time and again upon market sentiment. Those that succeed over the longer-term have a mode investment decision-making that, if not unique, is colloquially known as ‘magic sauce’ (an intuitive feel for market sentiment which is recognised as such by the market for talent).

Keeping up with a rising market is somewhat less challenging than dealing with a market that is about to turn (up or down). In this respect, asset managers face immediate and longer-term issues that complicate the framing and implementation of investment strategy. One is obvious – if the market is expected to turn, should the benefits of a rising market be immediately capitalised by selling-out to other traders? Those lulled into a false sense of security by a rising market might be ‘surprised’ by events and take flight in the hope of realising a profit. A more sophisticated response could see those who have benefited from the past stay in the market on the expectation that the reversal is just a correction and that patience will be rewarded when the market returns to its upward path in the future (a time horizon relevant to framing investment strategy).

This type of strategy may require investment companies to back the judgement of their asset managers against market sentiment. In doing so, they may have their own concerns as a business and must assess whether their traders have something ‘special’ – insight, knowledge and understanding – which justifies going forward against market sentiment. In these circumstances, formal knowledge of the processes underpinning market movements and sentiment may be set against the tacit knowledge (judgement) of their asset managers.

4. KNOWLEDGE AND EMPLOYMENT CONTRACTS

Formal knowledge of investment strategy and practice is found in trading manuals and organisational protocols. These rule books are designed to codify industry practice and govern managers’ asset- and product-specific trading practices. Rule books were, at one time, formulaic in that their protocols matched the elements and precepts of the efficient markets’ hypothesis (see Litterman, Citation2004). However, as anomalies accumulated and recurrent financial crises precipitated the re-writing of company-specific rule books, these manuals became more like operational protocols subject to the review and over-sight of senior executives. As rule books became less reliable, there was an increasing premium on tacit knowledge. However, reliance upon tacit knowledge brings with it threats and opportunities to asset managers and their sponsors.

The significance of tacit knowledge varies by asset class, the transparency or otherwise of financial products, and market opportunities that are ‘contested’ in the sense that their value is not captured by existing trading routines.Footnote6 It is widely believed that the tacit knowledge can produce large profits for those asset managers and companies willing and able to mobilise and deploy it to their advantage. In this respect, tacit knowledge has two related attributes. First, it involves an intuitive ‘feel’ for market movements such that those that trade for and against market expectations tend to win over those not so endowed. Second, it involves an intuitive ‘feel’ for market value such that those who trade on market expectations recognise and take advantage of market mispricing. Tacit knowledge involves attention to market movements either directly and/or through market data and reporting systems (see Scheinkman, Citation2014).

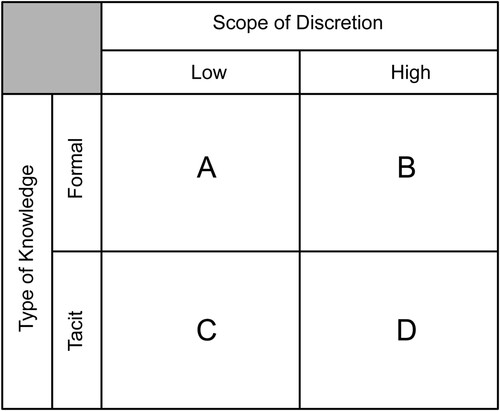

For investment companies, a key management issue is the nature and scope of the discretion provided asset managers. Rule books can impose limits on asset managers’ commitments subject to the oversight of senior executives. In other organisations, rule books are open-ended and are used to prompt engagement with senior managers rather than impose categorical limits and accountability. For ease of exposition, it is assumed that companies can provide a low degree of discretion through to a high degree of discretion wherein the former implies an employment contract that is subject to continuing over-sight and hard limits on risk-taking whereas the later involves limited over-sight and considerable flexibility when it comes to pursuing opportunities beyond notional limits.

For simplicity, the scope of discretion is represented in as ‘low’ and ‘high’ even if it is a continuum rather than a dichotomy in the industry. On the other side of are two forms of knowledge – codified or formal (represented by rule books, for example) and tacit (involving judgement buttressed by market data and insight born of experience and insight). This typology is one way of understanding the challenges that face asset management companies operating in a world of financial risk and uncertainty.

Figure 1. Typology of Asset Management. Source: Author.

Case A is an instance where senior executives provide asset managers little in the way of discretion and expect their managers to adhere to the accepted principles and practices of asset management. In this domain, the goal is to track relevant market indices rather than fall below or go above those indices in ways that assume a degree of risk-taking at odds with the objectives of the investment strategy. These types of investment products are typically transparent as to their underlying principles and practices and, on average, provide only a modicum of downside protection should market momentum falter under the weight of unexpected shocks (Clark & O’ Connor, Citation1997). These products are offered by the biggest investment managers and attract clients with large and small tranches of assets. Competition revolves around the reliability of returns against market benchmarks and fees and charges.

Given the large volume of assets allocated to Case A types of products, they are often referred to as the ‘default’ or ‘standard’ investment products offered in the market. In these instances, products are managed by teams of analysts and portfolio managers led by executives who are rewarded for predictability rather than innovation. As such, this model of management can be labelled as the ‘risk-adverse model of asset management’ in that both sides of the market value predictability over out-performance.

By contrast, Case D is an instance where asset managers are accorded a high degree of discretion in their investment strategies recognising that the performance of related investment products relies heavily upon the deployment of tacit knowledge. These types of products are conceived to produce higher than average market rates of return by exploiting (discovered) shortcomings in market knowledge and expectations. These types of products can produce remarkable returns, recognising that risk-taking is an essential ingredient in their conception and execution. At the same time, these types of products can fail spectacularly when tacit knowledge is overwhelmed by market movements that trounce active investment.

This model of management can be labelled as the ‘risk-seeking model of asset management’ recognising that out-performance against industry benchmarks demands a level of experience and expertise that is expensive and is challenging to manage as well as a modicum of luck in that market volatility is often both an opportunity and a threat to the business model. Systemic shocks such as the global financial crisis and commodity supply disruptions can play havoc with the performance of these types of investment strategies.

Large investment companies find it difficult to run, simultaneously, Case A and Case D investment products and teams. Obvious differences in compensation and employment contracts along with differences in management systems and accountability can encourage destructive envy and jealousy. Furthermore, these two instances demand very different approaches to risk management: a corporate management culture that rewards meeting and matching the performance of market indices at a competitive price (Case A) may be antithetical to products and commitments to high levels of risk-taking for out-performance (Case D). Not surprisingly, large investment companies are self-conscious about promoting risk-taking with high rewards and, over the long-term, may spin-out successful teams that work in the Case D domain rather than attempt to reconcile the irreconcilable within a company or set of related companies.

Case B products are found in markets dominated by high-volume, standardised investment products such as index-linked bond and equity products. Recognising that these products are quite transparent in their structure and execution, it is challenging to stand-out from the crowd – that is, claim an increasing share of the market. At one level, these types of products are labelled by market participants as ‘plain vanilla’ envelopes in that industry playbooks tend to dominate strategic investment. Nonetheless, some companies more than others have sought to innovate in this domain, providing product managers with discretion and budgets to match to systematically outperform immediate competitors. In these cases, data science and trading technologies can make a positive contribution to out-performance especially in circumstances where the margins are modest.

This model of management is less about innovation and risk-taking and more about managing via data analytics against the expected path of market indices. It is a model of management that relies on trading for and against short-term market movements. It is also a model of management that is less about tacit knowledge and more about reaping value from other investment companies and traders that have neither the capacity nor the expertise nor the patience to realise the cumulative value of winning bets on market mispricing.

Case C tends to be found in market segments where tacit knowledge is a key ingredient in driving returns and where mistakes or misconceived trading strategies may threaten the very existence of the companies engaged in this type of investment strategy. In these cases, realising the benefits of tacit knowledge can involve taking large risks relative to the resources available to managers’ host companies. These types of companies typically proscribe traders’ discretion, maintain real-time systems of oversight and require transparency as to the leverage used by asset managers to drive returns in their portfolios. Here, the rewards for out-performance are significant and tend to be shared throughout the company. If successful, these are often smaller, highly specialised investment companies operating in risk and uncertainty with matching integrated management and compensation systems.

This model of management is about giving licence to traders who have proven track records of success in realising returns form insights and knowledge otherwise not widely available in the market and/or require a degree of portfolio leverage that senior managers are willing to back notwithstanding the costs of poor performance. In this part of the market, managers claim significant rewards for their performance and may gravitate to asset management companies with clients that seek higher returns than otherwise available in the other models of management.

The market for asset management is framed by these four types of investment management strategies and products. In some of the world’s largest asset managers, all four products/management strategies can be found notwithstanding the tensions regarding discretion and compensation within and between asset management groups that co-exist with one-another. Tensions often exist between, for example, asset managers that run Case A type products and those that run Case D types of products. Indeed, asset managers that are responsible for Case D type products may find that their discretion and compensation is limited by the huge volume of assets held by managers running Case A type products.

5. HOARDING AND RENT-SEEKING BEHAVIOUR

To hoard knowledge is to exclude others from meaningful access and thereby gain an advantage over those who would benefit from knowledge sharing – for example, senior executives and competing asset managers. The key issue is ‘meaningful access’ given that financial markets and organisations are awash with information about what investors profess to be their investment strategies and products. Readily observable are the results of investment strategies and products. Harder to observe is how and why asset managers trade the way they do even if there is often information about market moves and positions taken when executing investment strategies. Rent seeking occurs when investors’ magic sauce cannot be reliably observed and replicated and where investment companies must rely upon asset managers for their skills and expertise.

The typology presented in the previous section is also a map of hoarding and rent seeking behaviour. For example, limited discretion combined with reliance upon codified knowledge (Case A) provides little in the way of opportunities to hoard knowledge and extract rents from employers and the market. Since related investment strategies and products are widely known in the industry, any advantage is due to happenstance and/or a technological advantage rather than asset managers’ magic sauce. By contrast, Case D is an instance where a high level of discretion combined with market-specific tacit knowledge may enable well-positioned asset managers to extract rents from clients, their employers and the market.

It was noted that Case A circumstances often result in employment contracts that emphasise salaries over bonuses, involve commitment to the objectives of investment companies rather than the interests of asset managers and produce investment routines that can be replicated by similarly qualified individuals inside and outside of the companies employing asset managers. These circumstances do not exclude the possibility of some asset managers in some companies being better at executing recognised investment strategies than others. Even in this domain, the management systems and technological infrastructure underpinning the execution of investment strategies can give some asset managers an advantage in the market over others not so endowed (Monk & Rook, Citation2020).

Case B situations reflect the ever-present premium on matching market indices and, if possible, eking-out a modest but predictable premium on related products. Senior executives may well provide asset managers considerable discretion about the framing and execution of trading strategies in circumstances where codified knowledge dominates market expectations. In doing so, senior executives often use bonuses to encourage the development of these types of routines while reinforcing the importance of keeping pace with market indices. In these cases, senior executives may require their asset managers to be transparent as to their strategies and may use bonuses selectively rather than encouraging a bonus culture.

The problem with Case B settings is twofold. First, consistently beating market indices with investment strategies and products based upon codified knowledge is, on average, a (relative) losing game. In many cases, the margin between outperforming and underperforming the market is small and is difficult to repeat on a consistent basis. Second, providing asset managers with significant discretion in these circumstances is akin to turning a blind eye to attempts to get ‘ahead of the market’ whether by suborning market participants, circumventing market norms and conventions and/or violating government securities’ regulations. Witness the recent scandal involving employees of 10 investment banks located in New York city who evaded ‘company-approved channels’ of communication when making market-related deals and trades (Financial Times, October 1st, 2022, page 20).Footnote7

In Case C situations, where operating in market segments requires a modicum of tacit knowledge for outperformance, limiting the discretion of asset managers is likely to result in underperformance against peers who have higher levels of discretion in competing companies. It may seem surprising that senior executives are, in effect, willing to compromise on the performance of their own asset managers operating in market segments that require magic sauce to realise out-performance against peers and industry benchmarks. This type of situation obtains for a variety of reasons. In some cases, senior executives may be more concerned about their own reputations as managers than the prospect of being held accountable for a relatively poor financial performance in certain market segments. In other cases, clients may be unwilling to switch out of these types of products when they are dependent upon large financial institutions for a suite of investment services that are expensive to manage on a product-by-product basis.

These types of clients may be wilfully ignorant, lack the capacity to closely assess the performance of certain types of products and, like large investment houses, may be more concerned about their reputations than the performance of certain types of products that are part of a much larger relationship with a recognised investment group or groups. These situations also obtain when the clients of large, multifunctional investment houses do not bear the immediate costs and consequences of this type of management strategy and/or where the costs and consequences of this type of management strategy are not revealed until sometime in the future.

While Case A dominates the asset management in terms of AuM, there are other models of management that are designed to manage some of the more pernicious aspects of the model as well as provide incentives for collaboration within and between asset management companies given the costs of hoarding and rent-seeking behaviour (Clark, Citation2018). Being an ambitious asset manager willing and able to operate in market segments that carry a premium on tacit knowledge but hamstrung by limited discretion may prompt conflict and subversive behaviour. It may also result in the separation of ambitious asset managers from their employers, taking with them clients that understand the premium on tacit knowledge and discretion in different cases. These start-ups are commonplace in large financial centres.

6. ASSET MANAGEMENT IN CANADA

The history and geography of financial markets and government regulation affects the institutional structure and performance of markets as illustrated by the political drama in the US associated with the adoption or not of ESG metrics in the production of investment returns by asset managers and state-based public sector pension funds (see Hoepner et al., Citation2021). Nonetheless, the default model remains the global ‘reference’ model because of the dominance of US asset managers and the fact that senior executives, traders and (some) clients often benefit from the model whatever its economic and social costs. There is an ever-present tension between history and geography and the default model.

To illustrate, consider the circumstances facing the Canadian banking industry and its asset management departments. As is the case in Australia, the Canadian banking industry is dominated by a handful of very large retail and commercial banks. By some accounts these five banks, headquartered in Toronto, account for 90% of Canadian banking transactions. Each bank has a significant asset management department, although three of the five dominate the other two. Whereas Montréal (Québec) was once the key financial centre of Canada, Toronto holds sway just as the Ontario economy dominates the Canadian economy. Nonetheless, there remain significant Québec-based financial institutions like the Québec Pension Plan (QPP) just as Vancouver (British Columbia) is an emerging financial centre facing Asia.

Let us assume that each banks’ Wall Street operations is dominated by a Case A culture of management wherein the ruling ethos of the New York financial industry is one where asset managers ‘eat what you kill’ (Mack, Citation2022, p. 187). Hiring high-performing investment staff on Wall Street requires meeting or going beyond the compensation and conditions including scope of discretion offered by peers – by asset class, AuM and mandates. Wall Street is the epicentre of the global industry.

Each bank has significant asset management operations in New York City – the world’s leading financial centre (Urban et al., Citation2022). They also have related operations if not market-sensitive asset management functions in other US centres such as Charlotte (North Carolina) and San Francisco and Los Angeles (California). The available data on Canadian banking institutions and asset management companies suggest that these banks are not particularly large by international standards. Industry survey data for 31 December 2022 indicated that the two largest Canadian banks by AuM were Royal Bank of Canada and Toronto Dominion that were ranked 55th and 64th, respectively, in the league table reported by Pensions and Investments in the 12 June 2023 issue. The largest asset managers were American, dominate their domestic markets, and have global footprints (see Appendix).

In any event, Canadian banks’ Wall Street asset management operations act on behalf of Canadian clients including Canadian pension funds and insurance companies with mandates that originate via the front offices of banks found on Bay Street rather than Wall Street. Often, the contracts offered Toronto-based asset management executives are either a discounted version of model A (Wall Street) or Case B which is framed in terms of the compensation practices across the financial operations of the banks’ Toronto-headquarters. It is not surprising that Canadian banks with operations in New York face challenges in reconciling the Wall Street model of asset management with the preferred model of management in Toronto and Montreal. These tensions are hardly ever resolved so much as managed against the predatory practices of large US asset management groups.

Underpinning the Toronto-based culture of finance are Ontario and federal public sector pension funds including the federal government’s Canadian Pension Plan Investment Board (CPPiB) – these funds and the pension operations of a number of major Canadian companies account for more than C$1.5 trillion in assets under management. The largest funds have built significant internal asset management functions with compensation and recruitment policies that rival the big five Canadian banks. Whereas large New York and New England based public-sector pension funds overshadow (AuM) Ontario-based public sector funds, those that have significant internal asset management functions have found it difficult to compete with their commercial rivals. A string of reports on New York City-based pension funds have shown that these funds suffer from underfunding, relatively low compensation and under-funded market-facing investment operations.

The large Toronto-based public-sector pension funds rely upon their investment departments to underwrite beneficiaries’ defined benefit pensions. In doing so, the management goal is less about maximising the rate of return and more about, at a minimum, meeting long-term obligations. In doing so, these organisations manage the ‘pathway’ to paying pension benefits year-by-year in ways that balance short-term and long-term returns against the risks of being underfunded in the face of long-term (50–70 years) commitments. These funds use multiple asset classes with teams of investment managers whose responsibilities include contributing asset-specific investment returns in relation to overarching pension fund objectives. With respect to , this is a Case C model of management.

Fieldwork suggests there are significant differences between Canadian and US pension funds in terms of the in-sourcing and out-sourcing of investment mandates and the scope of investments by asset classes and related instruments. As well, the political sponsors of public sector pension plans can be far more intrusive in the management of US plans than in Canadian plans. Witness the furore over public pension fund ESG investments in Republican-dominated US state legislatures. If not always acknowledged, these differences can be found in the challenges associated with the recruitment and retention of senior staff. See the commentary by Arleen Jacobius in Pensions & Investments (20 September 2023) about the unexpected departure of the CIO of CalPers and her return to Toronto where it was noted that ‘she did not get universal support from the investment team at the $US463.6 California Public Employees Retirement System’.

A number of implications follow from the Case C model of investment management. First, given the overarching goals of their investment departments, these pension funds are organised around a common goal or goals such that a star manager or a group of star managers would find it difficult to hold the pension fund hostage to their demands for a model C type of compensation regime. Unlike the New York City funds, the Ontario funds pay industry rates and can compete with the big five banks for standout investment managers. At the same time, given the time horizons involved, job tenure and switching between institutions is less common than in banks and asset management firms. Importantly, compensation includes both individual and team components and, most importantly, elements that respect the performance of the entire investment department and/or pension fund.

This model of management has proven to be resilient (see Archer, Citation2011). Indeed, some of the larger funds have used investment management services of the banks to augment their investment strategies while keeping at arm’s length asset classes and investment strategies that would disturb the underlying model of management. That is, the pension funds have learnt how to segment their asset management functions to retain control of core components of their investment strategies while outsourcing those aspects of investment that would disturb the internal coherence of the fund.

This is a model of management that has been followed by other similar organisations around the world. For example, the Australian super funds have also built large internal asset management functions focused on producing competitive rates of return. Here, again, the overarching objective of Australian super funds has been a key component in holding to Case C types of management models. This can mean, however, losing stars and their teams who feel undervalued against market norms. In which case, rather than disturb internal benchmarks, these types of funds tend to spin out these activities to the market and use their contractual powers to buy-in these types of services on a cost-effective basis.

7. IMPLICATIONS AND CONCLUSIONS

This paper has focused upon the global asset management industry, the tensions between banks and asset management companies and the subtleties of employment contracts that hinge on the balance struck between managers’ discretion and accountability when there is a premium on tacit knowledge in framing and executing investment strategies. I also argue that context makes a difference: that is, national institutions and regulatory practices are embedded in employment contracts and shape the relationships between investment managers and their corporate sponsors (Clark, Citation2016).

There are many papers and books on the principles and practice of investment management. But there is less research on models of management in the industry notwithstanding critical commentaries that emphasise the culture of finance (Morris & Vines, Citation2014), the perverse incentives on asset managers that can, in some cases, result in financial crises (Lo, Citation2019) and the challenges of regulating the industry at home and abroad (Bernanke, Citation2012). Here, a stylised model of management is used to bring to light some of the challenges and dilemmas facing asset management companies when reliant upon talented individuals and teams and the spatial implications thereof (referencing Toronto and New York City).

The global asset management industry is dominated by Anglo-American companies (see Appendix), notwithstanding the attempts of many EU countries and some east Asian countries to join the race for a share of the industry’s assets-under-management. As such, the industry is caught-up in geopolitical tensions wherein the industry can be held to account, in some cases, for the imposition of corporate and industry models of management and target rates of return that violate national norms and regulations as to the balance of powers between corporations, governments and labour. The long-term effects of the global financial crisis (2008–2012) have amplified these tensions especially as regards the viability of bank-led systems of financial intermediation found in east Asia and Europe (Braun, Citation2022).

The paper is based upon three suppositions. First, as much as the Anglo-American investment industry is distinctive in terms of its decision-making frameworks and practices, it represents a challenge to related frameworks and practices in other countries. This is clearly the case for much of continental Europe. But it is also seen as a challenge by financial institutions and regulatory agencies in Australia, Canada, and the UK. Second, for many analysts these frameworks and practices carry with them significant economic and social costs – witness Morris and Vines (Citation2014) on the adverse economic consequences of the Anglo-American culture of finance. Third, even though attempts have been made to blunt the culture of finance as embodied by American asset managers, effective resistance has required building alternative models of management in the face of resistance.

Recognising the diversity of countries’ financial sectors and their respective ecosystems, I argue that the hegemony of Anglo-American finance is in fact the hegemony of US asset managers when considering, for example, the shape and size of the Canadian banking system. In this respect, the Canadian case is both the twenty-first century exemplar of my argument and an instance of unresolved tensions between jurisdictions as regards their attempts to hold the American asset management at bay. It is observed that the Canadian asset management industry is also a ‘local’ industry in that large Canadian pension funds have established their own asset management groups to mediate the power of Canadian banks and, most importantly, the hegemony of US asset managers.

Notwithstanding differences in scales of operation, investment firms share a dilemma: stand-out investment managers often claim a premium on their expertise, challenging company-specific and market-specific norms and conventions. At the other end of the spectrum, those that service these companies do little better than local labour market standards – compensation is less about expertise and more about the volume of labour (McDowell et al., Citation2009). For example, the Swedish government-sponsored pension (AP) funds offer local employment contracts based upon Swedish norms and conventions but vary those contracts to match London-based norms and conventions when applied to offshore investment employees. Otherwise, these types of funds outsource/offshore the production of investment returns to London-based global investment houses and pay the price of those employment contracts through service fees and charges.

Inevitably, the map of global finance is a mirror image of international financial stocks and flows, nation-specific organisations and providers, and financial centre-specific competencies and products. I have argued that certain types of products are best developed and managed in London and New York as opposed to Amsterdam, Paris, Stockholm and Toronto. Global financial centres are centres of financial innovation wherein good ideas and game-changing investment strategies originating in larger financial institutions and organisations are taken to market by newly founded investment firms. To the extent that embodied tacit knowledge is a crucial ingredient in these products, exit may be the only option for investment managers stifled or hamstrung by limited discretion and the necessity of sharing of tacit knowledge.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (110.1 KB)ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author is pleased to recognise the inspiration provided by Meric Gertler, collaboration with Ashby Monk and the team at Stanford University and ongoing dialogue with investment companies about their management of financial performance. The editors, three anonymous referees, Harold Bathelt, Michael Drew, and Dariusz Wójcik provided insightful and constructive comment on previous drafts of this paper. None of the above should be held responsible for the contents and/or arguments presented herein.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The author's current responsibilities include membership of the investment committees of the Oxford Staff Pension Scheme and the endowment fund of St Edmund Hall, chair of the Ethics committee of IP Group (London) and advising and investing in FinTech start-ups. None of the above are sponsors of this paper or have a direct or material interest in its argument and content. No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 See Bathelt and Glückler (Citation2013, Ch. 4) on knowledge-creation and management in firms with an extensive discussion about formal and tacit knowledge referencing key contributions of Gertler and Polanyi. They emphasise the contingent and relational aspects of knowledge – key elements of the model of knowledge management developed in this paper.

2 The term “magic sauce” represents the market-facing skills and expertise of investment managers given that competence is more than recognisable qualities and attributes. The phrase comes from interviews with market participants and suggests that an intuitive ‘feel for the market’ is often important in realising investment objectives (see also Barras et al., Citation2022).

3 Related contributions are found in economics, management and legal studies which emphasises asymmetric information, incomplete contracts and reliance (see Aghion & Tirole, Citation1997; Choi & Triantis, Citation2021; Hart, Citation1995).

4 The European banking industry and related asset management organisations are not considered in this paper. These finance organisations face significant challenges in making good on their global aspirations notwithstanding the relative success of Ireland and Luxembourg. See Clark (Citation2016) and Wójcik et al. (Citation2024).

5 Recent research on the evolving shape and performance of the global banking industry including reference to the experience of OECD countries since 1970 and including the impact of the global financial crisis can be found in Amel et al. (Citation2004), Goddard et al. (Citation2007) and Wheelock (Citation2011).

6 This account is informed by Lo (Citation2019) and assumes that markets are not self-governing trading regimes that converge time-and-again on a stable equilibrium. On the other hand, markets are relatively stable such that ‘pockets’ of disequilibrium are relatively rare and are associated with exogenous shocks (Farmer et al., Citation2023).

7 See https://www.sec.gov/news/press-release/2022-174 on the findings of the US Securities Exchange Commission and https://www.sec.gov/litigation/admin/2022/34-95928.pdf on the case brought against Deutsche Bank on the same issue.

REFERENCES

- Aghion, P., & Tirole, J. (1997). Formal and real authority in organizations. Journal of Political Economy, 105(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1086/262063

- Amel, D., Barnes, C., Panetta, F., & Salleo, C. (2004). Consolidation and efficiency in the financial sector: A review of the international evidence. Journal of Banking & Finance, 28(10), 2493–2519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2003.10.013

- Amin, A. (2003). Spaces of corporate learning. In J. Peck, & H. W.-C. Yeung (Eds.), Remaking the global economy (pp. 114–130). Sage.

- Archer, S. (2011). Pension funds as owners and as financial intermediaries: A review of recent Canadian experience. In C. A. Williams, & P. Zumbansen (Eds.), The embedded firm: Corporate governance, labor and finance capitalism (pp. 177–204). Cambridge University Press.

- Arjaliès, D. L., Grant, P., Hardie, I., MacKenzie, D., & Svetlova, E. (2019). Chains of finance: How investment management is shaped. Oxford University Press.

- Barras, L., Gagliardini, P., & Scaillet, O. (2022). Shill, scale, and value creation in the mutual fund industry. Journal of Finance, 77(1), 601–638. https://doi.org/10.1111/jofi.13096

- Bathelt, H., & Glückler, J. (2013). Institutional change in economic geography. Progress in Human Geography, 38(3), 340–363. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132513507823

- Bauer, R., Braun, R., & Clark, G. L. (2008). The emerging market for European corporate governance: The relationship between governance and capital expenditures, 1997–2005. Journal of Economic Geography, 8(4), 441–469. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbn018

- Bebchuk, L. A., Cohen, A., & Hirst, S. (2017). The agency problems of institutional investors. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(3), 89–102. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.31.3.89

- Bebchuk, L., & Hirst, S. (2019). The spectre of the giant three. Boston University Law Review, 99(3), 721–741.

- Bernanke, B. (2012). The federal reserve and the financial crisis. Princeton University Press.

- Braun, B. (2021). Asset manager capitalism as a corporate governance regime. In J. Hacker, A. Hertel-Fernandez, P. Pierson, & K. Thelen (Eds.), The American political economy: Politics, markets, and power (pp. 270–294). Cambridge University Press.

- Braun, B. (2022). Exit, control, and politics: Structural power and corporate governance and asset manager capitalism. Politics and Society, 50(4), 630–654. https://doi.org/10.1177/00323292221126262

- Choi, A. H., & Triantis, G. G. (2021). Contract design when relationship-specific investment produces asymmetric information. Journal of Legal Studies, 50(2), 219–260. https://doi.org/10.1086/716173

- Christophers, B. (2023). Our lives in their portfolios: Why asset managers Own the world. Verso.

- Clark, G. L. (1998). Stylized facts and close dialogue: Methodology in economic geography. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 88(1), 73–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8306.00085

- Clark, G. L. (2016). The components of talent: Company size and financial centres in the European investment management industry. Regional Studies, 50(1), 168–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2015.1068932

- Clark, G. L. (2018). Learning-by-doing and knowledge management in financial markets. Journal of Economic Geography, 18(2), 271–292. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lby005

- Clark, G. L., & Monk, A. H. B. (2017). Institutional investors in global markets. Oxford University Press.

- Clark, G. L., & O’ Connor, K. (1997). The informational content of financial products and the spatial structure of the global finance industry. In K. Cox (Ed.), Spaces of globalisation (pp. 89–114). Guilford.

- Clark, G. L., & Thrift, N. J. (2005). The return of bureaucracy: Managing dispersed knowledge in global finance. In K. Knorr Cetina, & A. Preda (Eds.), The sociology of financial markets (pp. 229–249). Oxford University Press.

- Farmer, L. E., Schmidt, L., & Timmermann, A. (2023). Pockets of predictability. Journal of Finance, 78(3), 1279–1341. https://doi.org/10.1111/jofi.13229

- Gertler, M. S. (2001). Best practice? Geography, learning and the institutional limits to strong convergence. Journal of Economic Geography, 1(1), 5–26. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/1.1.5

- Gertler, M. S. (2003). Tacit knowledge and the economic geography of context, or the undefinable tacitness of being (there). Journal of Economic Geography, 3(1), 75–99. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/3.1.75

- Goddard, J., Molyneux, P., Wilson, J. O. S., & Tavakoli, M. (2007). European banking: An overview. Journal of Banking & Finance, 31(7), 1911–1935. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2007.01.002

- Graham, J. R. (2022). Presidential address: Corporate finance and reality. Journal of Finance, 77(1), 1975–2049. https://doi.org/10.1111/jofi.13161

- Haberly, D., MacDonald-Korth, D., Urban, M., & Wójcik, D. (2019). Asset management as a digital platform industry: A global financial network perspective. Geoforum, 106, 167–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.08.009

- Hall, P., & Soskice, D. (Eds.). (2001). Varieties of capitalism: The institutional foundations of comparative advantage. Oxford University Press.

- Halpern, O., Jagoda, P., Kirkwood, J. W., & Weatherby, L. (2022). Surplus data: An introduction. Critical Inquiry, 48(2), 197–210. https://doi.org/10.1086/717320

- Hart, O. (1995). Firms, contracts, and financial structure. Oxford University Press.

- Hoepner, A. G., Majoch, A. A., & Zhou, X. Y. (2021). Does an asset owner’s institutional setting influence its decision to sign the principles for responsible investment? Journal of Business Ethics, 168(2), 389–414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04191-y

- Hossain, T., & List, J. A. (2012). The behaviouralist visits the factory: Increasing productivity using simple framing manipulations. Management Science, 58(12), 2151–2167. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1120.1544

- Laffont, J. J., & Martimort, D. (2009). The theory of incentives. Princeton University Press.

- Lewellen, J., & Lewellen, K. (2022). Institutional investors and corporate governance: The incentive to be engaged. Journal of Finance, 77(1), 213–264. https://doi.org/10.1111/jofi.13085

- Leyshon, A. (2021). Financial ecosystems and ecologies. In J. Knox-Hayes, & D. Wójcik (Eds.), The routledge handbook of financial geography (pp. 121–141). Routledge.

- Leyshon, A., Burton, D., Knights, D., Alferoff, C., & Signoretta, P. (2004). Towards an ecology of retail financial services: Understanding the persistence of door-to-door credit and insurance providers. Environment and Planning A, 36(4), 625–645. https://doi.org/10.1068/a3677

- Litterman, B. (2004). Modern investment management. John Wiley.

- Lo, A. W. (2019). Adaptive markets. Princeton University Press.

- Mack, J. (2022). Up close and All In: Life lessons from a Wall Street warrior. Simon and Schuster.

- MacLean, I. W. (2013). Why Australia prospered: The shifting sources of economic growth. Princeton University Press.

- McDowell, L., Batnitzky, A., & Dyer, S. (2009). Precarious work and economic migration: Emergent immigrant divisions of labour in Greater London’s service sector. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 33(1), 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2009.00831.x

- McKenzie, D. (2006). An engine, not a camera: How financial models shape markets. MIT Press.

- Monk, A. H., & Rook, D. (2020). The technologized investor: Innovation through reorientation. Stanford University Press.

- Morris, N., & Vines, D. (2014). Capital failure: Rebuilding trust in financial services. Oxford University Press.

- Pažitka, V., Bassens, D., Van Meeteren, M., & Wójcik, D. (2022). The advanced producer services complex as an obligatory passage point: Evidence from rent extraction by investment banks. Competition and Change, 26(1), 53–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/1024529421992253

- Pistor, K. (2019). The code of capital. Princeton University Press.

- Pourciau, S. (2022). On the digital ocean. Critical Inquiry, 48(2), 233–261. https://doi.org/10.1086/717319

- Scheinkman, J. A. (2014). Speculation, trading, and bubbles. Columbia University Press.

- Sharpe, W. F. (2007). Investors and markets. Princeton University Press.

- Urban, M., Wójcik, D., Pažitka, V., & Wu, W. (2022). Labour and control shifts: Financial services in US metro areas, 2007–17. Regional Studies, 57(7), 1254–1266. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2022.2120976

- Wheelock, D. C. (2011). Banking industry consolidation and market structure: Impact of the financial crisis and recession. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, 93(6), 419–438.

- Wójcik, D. (2021). Financial geography III: Research strategies, designs, methods and data. Progress in Human Geography, 03091325211043208.

- Wójcik, D., Iliopoulos, P., Ioannou, S., Keenan, L., Migozzi, J., Monteath, T., Pazitka, V., Torrance, M., Urban, M., with maps & graphics by Cheshire, J., & Uberti, O. (2024). An Atlas of finance. Yale University Press. (forthcoming).

- Wójcik, D., Urban, M., & Dörry, S. (2022). Luxembourg and Ireland global financial networks: Analysing the changing structure of European investment funds. Transactions, Institute of British Geographers, 47(2), 514–528. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12517