Abstract

Background

Many anti-obesity health promotion campaigns focus on physical activity as a means to lose weight. Organizations have created positive images of people living with obesity being physically active with the intention of normalizing people in larger bodies being active. However, it is not clear if using the images when taking a weight-neutral (compared to a weight-centric) approach will be more positively received, and thus more effective, in promoting physical activity to people living in larger bodies.

Aims

The primary purpose of the present research was to examine whether people in larger bodies preferred messages that featured images of people in larger bodies being active with weight-neutral (i.e., no mention of weight loss) compared to weight-centric (i.e., weight loss-focused) physical activity messages. Secondary purposes were to examine between condition differences on internalized weight bias and whether message ratings or internalized weight bias mediated effects of message type on objectively measured physical activity.

Methods

Adults of any self-identified gender who also self-identified as living in larger bodies were recruited through a variety of Obesity Canada channels including their newsletter and social media. The data from 54 adults (Mage = 49.9 years; 90.7% women) were analyzed. Participants completed pre-test measures (demographics and internalized weight bias), wore an accelerometer for one week then viewed eight images with condition-specific messages. This was followed with post-test measures (image ratings, thought listing, internalized weight bias) and one more week of accelerometer wear.

Results

The weight-neutral messages were rated more positively than the weight-centric messages but there were no between group differences in internalized weight bias nor in sedentary behavior, light physical activity, or moderate to vigorous physical activity.

Discussion

It is possible that participants were already interested in the topic of weight bias and possibly aware of the images used in this study, limiting the generalizability of the study. However, the results of this research, considered with the findings of other researchers who report health messages to be more motivating, indicate that focusing on weight is not recommended when promoting physical activity to people in larger bodies. Rather other benefits of being active should be highlighted.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

This research compared a message about the health benefits of physical activity without mentioning weight compared to a message about being active to lose weight. Both messages were shown with pictures of people in larger bodies doing physical activity. People living in larger bodies liked the messages that did not mention weight more than the messages that did mention weight. However, both groups felt the same about their body size and did the same amount of activity. Physical activity is best promoted without mentioning weight loss.

Physical activity (PA) and exercise are positive health behaviors for people of any size, independent of weight loss. For example, PA can contribute to a reduction in visceral fat in persons living with obesity even in the absence of weight loss (Bellicha et al., Citation2021). Researchers have also found that weight-neutral approaches that include discussions of being active for pleasure and accepting one’s body can be as effective as weight-loss programs on health outcomes such as total cholesterol and behavioral outcomes such as increased PA, among other positive changes (Mensinger et al., Citation2016). Despite such findings, many anti-obesity and weight-loss focused health promotion campaigns focus on PA as a means to lose weight (Hunger et al., Citation2020). A systematic review of mass media campaigns targeting weight loss in adults showed that PA was one of two main featured behaviors (the other being reduction of sugar-sweetened beverages; Kite et al., Citation2018). At the same time, obesity and body size-related stereotypes are perpetuated by negative media portrayals of persons with obesity or living with larger bodies as lazy or uninterested in being active (Puhl et al., Citation2013). In an effort to counter such pejorative representations, organizations such as the Rudd Center and Obesity Canada have created positive images of people living with obesity, some of which show people being physically active. The images are intended to be used to positively promote PA and to normalize people in larger bodies being active. However, it is not clear if using the images when taking a weight-neutral (compared to a weight-centric) approach will be more positively received, and thus more effective, in promoting PA to people who self-dentify as living in larger bodies.

Some research has investigated the effects of images of people in larger bodies being active. One study compared the effects of PA-focused images and videos created by Obesity Canada to control materials featuring images of people not living with obesity on weight bias. The researchers found that people who did not self-report living with obesity themselves, nor had friends or family with obesity, and who saw the control images had lower weight bias than people who saw materials that featured people living with obesity (Berry & Myre, Citation2021). Thus, materials such as those created by Obesity Canada might not be effective in reducing weight bias among people with no experience of obesity themselves or through close others with obesity. These findings confirm the skepticism expressed by women living in larger bodies of the possible effectiveness of the images of people in larger bodies being active (Myre et al., Citation2019). Participants in that study said they found the images motivating and relatable, and supported more body weight diversity in PA images, but doubted that the general public would react positively to the images or that they would have any effect on weight bias. Thus, it is expected that people living with obesity will appreciate the use of PA images featuring people in larger bodies but questions remain about the most effective text to accompany such images.

As noted earlier, a 6-months long intervention comparing a weight-neutral to a weight-loss program showed positive health and behavioral results (Mensinger et al., Citation2016). But research investigating simple weight-neutral compared to weight-centric messaging, such as what might be seen in PA promotion campaigns, is limited and what has been conducted has shown mixed results. For example, researchers have found body positive advertising campaigns had little effect on internalized weight bias (i.e., when a person holds negative self-beliefs because of their own body weight or size; Durso & Latner, Citation2008) even though viewers found the body positive advertisements empowering and uplifting (Puhl et al., Citation2021). The research was limited because the majority of participants were not living in larger bodies. Another study, in which about half the participants self-identified as having overweight or obesity, showed that advertisements focused on the negative health effects of excess body fat and included graphic imagery elicited the strongest negative emotional response but were also perceived to have the most potential to motivate people to lose weight compared to other advertisements (Dixon et al., Citation2015). However, focusing on excess body fat and weight loss may be a barrier for PA for people living in larger bodies because it can increase internalized weight bias (Myre et al., Citation2022). Internalized weight bias has been related to a greater urge to avoid exercise, a relationship mediated by negative affect (Carels et al., Citation2019). Internalized weight bias has also been found to be an important moderator of the effects of a healthy living program on PA (Mensinger & Meadows, Citation2017).

In an effort to find effective ways to create effective PA messages, the primary purpose of the present research was to examine whether people in larger bodies preferred messages that featured images of people in larger bodies being active with weight-neutral (i.e., no mention of weight loss) compared to the same images with weight-centric (i.e., weight loss-focused) PA messages. Secondary purposes were to examine between condition (i.e., weight-neutral compared to weight-centric) differences on internalized weight bias and whether image ratings and internalized weight bias mediated the effects of the images and messages on objectively measured sedentary behavior, light PA, and moderate to vigorous PA (MVPA).

The main hypothesis was that participants who viewed the images with weight-neutral messages would rate the messages more positively and make more comments supporting the messages than those who viewed the images with weight-centric messages. Secondary hypotheses were that (1) participants who viewed the images with weight-neutral messages would have lower internalized weight-bias compared to participants who viewed the images with weight-centric messages; (2) that internalized weight bias and image ratings would mediate the relationship between message condition and PA.

Method

Participants

Adults of any self-identified gender who also self-identified as living in larger bodies were recruited with advertisements in Obesity Canada’s newsletter (which had about 10,000 subscribers at the time of recruitment) and posted to social media channels including Facebook and Twitter (now the platform X). Anyone interested in participating contacted the researchers via email. That organization had no other involvement with the study. Inclusion criteria were being over the age of eighteen years, having the ability to read and understand English and no visual impairment (as this wouldn’t allow them to view the images and complete the questionnaires), and ability to be physically active if they wished. It was assumed that there would be a difference in image ratings between the two groups with a medium effect size. Based on this, a sample size of 60 was calculated using G*Power 3.1.9.2 based on a t-test with two groups, a medium effect size, p = .05, and power = .8 as the primary outcome measure.

Procedure

Participants who met inclusion criteria were randomized to one of two conditions: weight-neutral or weight-centric message. Prior to the start of the study a list of participant numbers was generated and assigned to the conditions using a random number generator. All study sessions were completed online using an application of the participants choosing (e.g., Zoom). Accelerometers were mailed to participants and returned to the researcher (participants were provided with a prepaid padded envelope). Participants could skip any questions they did not wish to answer, during all testing sessions and for all survey measures. During the baseline session, participants completed the pretest measures (demographics and internalized weight bias) and were instructed on accelerometer use. They were asked their height and weight and were explicitly informed that these data were only collected because they were needed for the accelerometer calculations and for descriptive purposes. One week later, during the intervention session, participants viewed their condition-specific images and messages (eight images with weight-neutral or weight-centric messages for five seconds each) and then completed post-test measures (image ratings, thought listing, internalized weight bias). Participants continued to wear the accelerometer for one more week and then completed the measure of internalized weight bias one last time.

All participants were sent a debriefing message after their participation concluded explaining the purpose and rationale of the study, explaining why, especially, the weight-centric messages were shown. The debriefing ended with “Physical activity is important for people of all body sizes. It can be a way to support one’s physical, mental, and social health regardless of weight status or weight change. We hope that our research findings can help inform the development of physical activity promotion materials that are inclusive and motivating to people of all body sizes.” Participants were given a $10 Amazon gift card as a thank you for each session they completed. All procedures were approved by the University of Alberta human research ethics board and participants provided consent at the start of each session.

Measures and materials

Images

The images were from publicly available image banks such as those created by Obesity Canada (n.d.). They showed women and men living in larger bodies engaged in weight training, on a treadmill, cycling, stretching, or walking. The images were the same in both study conditions but the text differed. For example, an image of a woman doing strength work outside on a yoga mat either had the weight-neutral message “Moving my body can support my mental health” or the weight-centric message “Moving my body can support my weight loss goals.” Example images and text are shown in the supplementary materials.

Image rating

After each image with message was shown for five seconds, participants rated their “agreement with the message on the image” on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Participants responded in an average of 4.1 seconds (SD = 3.8). The reliability of the ratings was good, α = .71 and a mean score was calculated for use in data analysis.

Thought listing

After all the images with messages had been rated, participants were asked "What thoughts did you have while viewing the images and messages?” They typed their responses into the program. These data were used to further describe how the messages were received. These data also served as a manipulation check with any participant not commenting on the messages excluded from analysis.

Weight bias internalization

This was measured with an 11-item scale rated on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) scale (Hilbert et al., Citation2014). Relevant items were reverse scored so that a higher score indicated higher internalized weight bias. Sample items include: "Because of my weight, I feel that I am just as competent as anyone (reverse-scored item), or "I am less attractive than most other people because of my weight”. Scale reliability was high across the three testing sessions, α range: .91–.93.

Objective PA

ActiGraph GT3X accelerometers BT (ActiGraph, Pensacola, Florida) were used with a 90 Hz for sampling frequency. Participants were asked to wear the accelerometer on the right hip during waking hours removing it only during sleep and water-based activities. Collected data were downloaded in 60 second epochs with low frequency extension filter to include low-intensity movements. Wear time was validated using the Choi et al. (Citation2011) algorithm, which consists of 90 consecutive minutes of zero counts per minute (cpm) with an allowance of two minutes of activity when it is placed between two 30 consecutive minutes windows of zero cpm. Data were considered valid if participants wore the accelerometer for a minimum of ten hours a day and five days during each week.

PA and sedentary time were classified using the Freedson et al. (Citation1998) algorithm for adults: the cut-points for sedentary time = 0–99 cpm, light activity = 100–1951 cpm, moderate activity = 1952–5724 cpm, and vigorous > 5725 cpm. Actilife 6.13.4 software was used for data download, data calculation, and wear time validation. Percentage of time spent in sedentary, light, and MVPA were used as variables for analysis.

Demographics

Participants self-reported their age in years, their gender (options: woman, man, non-binary, prefer not to answer), ethnicity (open-ended), education (have not completed high school, high school, college or technical diploma, undergraduate degree, professional or graduate degree, prefer not to answer), and annual income (from < $25,000 to > $100,000 in increments of $25,000, and prefer not to answer).

Data analysis

The main hypothesis was tested with a t-test with image group as the between subjects factor and image ratings as the dependent variable. Comments were coded with the a-priori codes of pro-message, anti-message, pro-PA, and anti-PA. After one researcher assigned codes, a second researcher coded one-third of the comments (randomly selected using SPSS) and results were compared using SPSS. Between group differences in the number of statements assigned a code were tested using chi-square analyses.

The secondary hypothesis that participants who viewed the images with weight-neutral messages would have lower internalized weight-bias compared to participants who viewed the images with weight-centric messages was tested with a Repeated Measures Analysis of Variance test (RM ANOVA) with internalized weight bias at pretest, posttest, and follow-up as the within subject’s factor and message group as the between subject’s factor.

The secondary hypothesis that internalized weight bias and image ratings would mediate the relationship between message condition and PA was tested with three mediation models with sedentary behavior, light activity, and MVPA at follow-up as outcome variables using Hayes (Citation2018) Process Macro model 4. In each of these models, message group was the X variable and the mean item ratings and internalized weight bias measured at posttest were the mediators. Independent variables were standardized before running the analyses.

Results

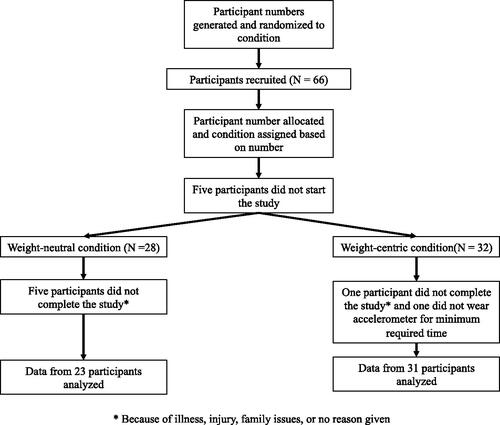

Sixty-six participants were recruited and data from fifty-four participants were analyzed; thirty-one in the weight-neutral condition and twenty-three in the weight-centric condition. shows how participants were excluded from data analysis. All participants provided responses to the thought listing that showed they had paid attention to the images and messages. We are unable to share the data because we did not receive ethics approval to do so. Demographic information is reported in . Means and standard deviations for item ratings, internalized weight bias, and activity behaviors by message group are shown in .

Table 1. Demographic information by condition.

Table 2. Means (SD) for variables at all testing points by message group.

The main hypothesis was supported with participants in the weight-neutral condition rating the messages more positively, t (52) = 2.40, p = .01, Cohen’s d = .65. All participants made relevant comments either about the images or how the images impacted their thoughts about PA. Inter-rater reliability was good, kappa range = .73 to .81. The kappa for anti-PA inter-rater reliability was .23, however of the comments coded by both researchers only three comments received this code accounting for the low reliability. There were significant differences by message group in the number of comments receiving anti-message and pro-PA codes. Sample comments, number of comments assigned a code by condition, and the results of chi-square tests examining between condition differences in numbers of comments per code are shown in .

Table 3. Sample comments and results of chi-square test examining differences between groups in number of statements assigned a code.

The secondary hypothesis that there would be between group differences in internalized weight bias was not supported. The results of the RM ANOVA showed a significant change in internalized weight bias over time, F (1, 52) = 10.00, p < .001, but no group by time interaction, F (1, 52) = .38, p = .69. Follow-up tests with message groups collapsed showed a significant decrease from pretest to posttest, p < .001, Cohen’s d = .25, and from pretest to follow-up, p < .001, Cohen’s d = .23, but no change from posttest to follow-up, p = .60, Cohen’s d = .03.

The secondary hypothesis that internalized weight bias and image ratings would mediate the relationship between message condition and PA was not supported as neither variable mediated the effect of message condition on any of the activity behaviors. Having less internalized weight bias was negatively related to sedentary behavior, p = .02, and positively related to light PA, p = .01. There were no significant variables in the MVPA model. The results of each mediation model are reported in .

Table 4. Mediation models.

Discussion

This research examined the effects of images of people living in larger bodies being active paired with weight-neutral or weight-centric PA messages. Even though the sample analyzed did not reach the pre-determined sample size, the main hypothesis was supported: participants in the weight-neutral condition rated the images more positively than those in the weight-centric condition, with a medium effect size. This result was also supported by open-ended comments. Comments that were against the weight centric message strongly countered the findings of Dixon et al. (Citation2015) who found that advertisements about “toxic fat” and showed graphic imagery were the most likely to motivate people to take action to lose weight compared to other advertisements. For example, one participant in the present research commented “I thought about how they were almost all focused on weight loss instead of overall health and that made me sad and made me feel like I should be ashamed of exercising for reasons other than weight loss.” Another participant wrote “weight loss is not the only goal for engaging in physical activity and I disagree with the focus on weight loss as the be all and end all goal”. These comments highlight how focusing on weight loss may lead to discouragement and "giving up" on health behaviors like PA when the person doesn’t experience weight loss.

It should be noted that the sample recruited for the present research were likely already interested and engaged in trying to mitigate weight bias. Participants were recruited through Obesity Canada, an organization that advocates for reduced weight bias. The findings therefore may not be representative of people living in larger bodies. But the findings of the present study also support other research that found people living in larger bodies reported better health as the most frequent motive to be active and a strong preference for walking or supervised PA (Hussien et al., Citation2022). Others have also demonstrated that positive health messages were more motivating than stigmatizing messages (Pearl et al., Citation2015). Similarly, women in larger bodies have reported the images similar to those used in the present study to be motivational and wished to see diverse bodies in PA promotion materials (Myre et al., Citation2019). But, the longer-term impact of images such as those created by Obesity Canada on movement behaviors or internalized weight bias remains to be determined, particularly as they exist in a media environment that contains many weight-biased images (Hunger et al., Citation2020), which may negatively influence internalized weight bias (Puhl et al., Citation2021). The results of the present research require replication with a sample drawn from the general population. However, the results of this research, considered with the findings of other researchers who report health messages to be more motivating (Hussien et al., Citation2022; Pearl et al., Citation2015), indicate that focusing on weight is not recommended when promoting PA to people in larger bodies. Rather other benefits of being active should be highlighted.

Contrary to the hypothesized relationship, there was no difference in internalized weight bias by message condition. Even though the present research was likely underpowered, this finding supports previous research that found body positive advertising campaigns did not have an influence on internalized weight bias even though viewers found them empowering (Puhl et al., Citation2021). As highlighted by others (e.g., Hunger et al., Citation2020), reducing internalized weight bias will likely require changes at societal levels (e.g., policy changes) and continued interventions targeting acceptance of one’s body. Yet, internalized weight bias decreased from pretest to posttest and follow-up in the present research. There are several reasons why this change in internalized weight bias may have been observed. First, even though participants could not see their accelerometer data, it is possible that simply wearing it affected their thoughts about themselves. Fitness trackers may increase motivation to be active in people not currently meeting their goals (Nuss et al., Citation2021). Although not testable in the current research, it is possible that wearing the accelerometer indirectly affected internalized weight bias. Similarly, knowing the study was about PA may have affected participant’s internalized weight bias, again because it affected the motivation of a sample of participants already likely engaged with the topic of weight bias. It is also possible that the change was seen because of regression to the mean where random variation in internalized weight bias led to less extreme internalized weight bias at posttest and follow-up (Barnett et al., Citation2005).

Also contrary to the hypothesized relationship, neither internalized weight bias nor image ratings mediated the relationship of message condition on movement behaviors The regression models indicated that internalized weight bias was positively related to sedentary behavior at follow-up and negatively related to light PA, but not related to MVPA. This finding in a small sample should nonetheless be of little surprise given that meta-analytic results have shown social media interventions targeting obesity (which are typically more intensive than merely showing some images) have very small effect on steps taken per day (An et al., Citation2017). Independent of message condition, internalized weight bias was related to more sedentary behavior and less light PA, supporting the findings of other studies (e.g., Mensinger & Meadows, Citation2017). Thus, it is necessary to find ways to promote PA without negatively affecting internalized weight bias. Future research could examine the effects of more ‘typical’ PA promotion materials that do not feature people in larger bodies compared to the images shown here on internalized weight bias.

There are several limitations to this research. First, although the present research was open to any gender, over ninety percent of participants self-identified as middle-aged White women. Others have found that internalized weight bias was not directly related to PA in men (Himmelstein et al., Citation2018) and future research should investigate the questions examined in this research with men. Another limitation, as already noted, is that participants were recruited with the help of Obesity Canada. This organization advocates on the part of people living with obesity and works to reduce weight bias. It is therefore likely that participants were already interested in the topic of weight bias and possibly aware of the images used in this study. The results of this research need to be replicated with people living in larger bodies who may not already be engaged with this topic to determine if the results can be generalized to a population more representative of the general public. Further, given the method of recruitment, calculating response rate is not possible as we cannot know how many people saw the advertisement. However, the response rate was quite low, further highlighting that people who did choose to participate were likely already interested in the topic. Another limitation is that the study was under powered, particularly with the fewer number of participants in the weight-centric message group. However, even with this limitation, this research showed that weight-neutral messages were more positively received than weight-centric messages with a medium to large effect size. Thus, in conclusion, this research adds to the literature by supporting the use of weight-neutral messages when promoting PA.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (152.3 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- An, R., Ji, M., & Zhang, S. (2017). Effectiveness of social media-based Interventions on weight-related behaviors and body weight status: Review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Health Behavior, 41(6), 1–10.

- Barnett, A. G., van der Pols, J. C., & Dobson, A. J. (2005). Regression to the mean: What it is and how to deal with it. International Journal of Epidemiology, 34(1), 215–220.

- Bellicha, A., van Baak, M. A., Battista, F., Beaulieu, K., Blundell, J. E., Busetto, L., Carraça, E. V., Dicker, D., Encantado, J., Ermolao, A., Farpour-Lambert, N., Pramono, A., Woodward, E., & Oppert, J. (2021). Effect of exercise training on weight loss, body composition changes, and weight maintenance in adults with overweight or obesity: An overview of 12 systematic reviews and 149 studies. Obesity Reviews, 22(Suppl 4), e13256.

- Berry, T. R., & Myre, M. (2021). Effects of physical-activity-related anti-weight stigma materials on implicit and explicit evaluations. Obesity Science & Practice, 7(3), 260–268.

- Carels, R. L., Hlavka, R., Selensky, J. C., Solar, C., Rossi, J., & Miller, C. (2019). A daily diary study of internalised weight bias and its psychological, eating and exercise correlates. Psychology & Health, 34(3), 306–320.

- Choi, L., Liu, Z., Matthews, C. E., & Buchowski, M. S. (2011). Validation of accelerometer wear and nonwear time classification algorithm. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 43(2), 357–364.

- Dixon, H., Scully, M., Durkin, S., Brennan, E., Cotter, T., Maloney, S., O’Hara, B. J., & Wakefield, M. (2015). Finding the keys to successful adult-targeted advertisements on obesity prevention: An experimental audience testing study. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 804.

- Durso, L. E., & Latner, J. D. (2008). Understanding self-directed stigma: Development of the weight bias internalization scale. Obesity, 16(Suppl 2), S80–S6.

- Freedson, P. S., Melanson, E., & Sirard, J. (1998). Calibration of the computer science and applications, Inc. Accelerometer. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 30(5), 777–781.

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression based approach. Guilford Press.

- Hilbert, A., Baldofski, S., Zenger, M., Löwe, B., Kersting, A., & Braehler, E. (2014). Weight bias internalization scale: Psychometric properties and population norms. PLoS One, 9(1), e86303.

- Himmelstein, M. S., Puhl, R. M., & Quinn, D. M. (2018). Weight stigma and health: The mediating role of coping responses. Health Psychology, 37(2), 139–147.

- Hunger, J. M., Smith, J. P., & Tomiyama, A. J. (2020). An evidence-based rationale for adopting weight-inclusive health policy. Social Issues and Policy Review, 14(1), 73–107.

- Hussien, J., Brunet, J., Romain, A. J., Lemelin, L., & Baillot, A. (2022). Living with severe obesity: adults’ physical activity preferences, self-efficacy to overcome barriers and motives. Disability and Rehabilitation, 44(4), 590–599.

- Kite, J., Grunseit, A., Bohn-Goldbaum, E., Bellew, B., Carroll, T., & Bauman, A. (2018). A systematic search and review of adult-targeted overweight and obesity prevention mass media campaings and their evaluation: 2000–2017. Journal of Health Communication, 23(2), 207–232.

- Mensinger, J. L., Calogero, R. M., Stranges, S., & Tylka, T. L. (2016). A weight-neutral versus weight-loss approach for health promotion in women with high BMI: A randomized-controlled trial. Appetite, 105, 364–374.

- Mensinger, J. L., & Meadows, A. (2017). Internalized weight stigma mediates and moderates physical activity outcomes during a healthy living program for women with high body mass index. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 30, 64–72.

- Myre, M., Berry, T. R., Ball, G., & Hussey, B. (2019). Motivated, fit, and strong – Using counter-stereotypical images to reduce weight stigma internalization in women with obesity. Applied Psychology. Health and Well-Being, 12(2), 335–356.

- Myre, M., Glenn, N. M., & Berry, T. R. (2022). Experiences of size inclusive physical activity settings among women with larger bodies. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 94(2), 351–360.

- Nuss, K., Moore, K., Nelson, T., & Li, K. (2021). Effects of motivational interviewing and wearable fitness trackers on motivation and physical activity: A systematic review. American Journal of Health Promotion, 35(2), 226–235.

- Obesity Canada. (n.d.). Image bank. https://obesitycanada.ca/resources/image-bank/.

- Pearl, R. L., Dovidio, J. F., Puhl, R. M., & Brownell, K. D. (2015). Exposure to weight-stigmatizing media: Effects on exercise intentions, motivation, and behavior. Journal of Health Communication, 20(9), 1004–1013.

- Puhl, R. M., Peterson, J. L., DePierre, J. A., & Luedicke, J. (2013). Headless, hungry, and unhealthy: A video content analysis of obese persons portrayed in online news. Journal of Health Communication, 18(6), 686–702.

- Puhl, R., Selensky, J. C., & Carels, R. A. (2021). Weight stigma and media: An examination of the effect of advertising campaigns on weight bias, internalized weight bias, self-esteem, body image, and affect. Body Image, 36, 95–106.