Abstract

Professional development in policy for K–12 teachers is relatively rare despite the indelible role that teachers play in policy implementation. This study describes the experiences of five teachers who completed the 10-month Texas Education Policy Fellowship Program. Results showed that the experienced classroom teachers garnered the most policy knowledge, situated leadership development, and networks. Additionally, they sought new professional development, and provided input to policy processes locally and with other teachers.

In the United States, K–12 teachers are charged with policy implementation, yet have few opportunities in shaping the policies they must enact (Lynch, Citation2020). Recent trends in education reform have revealed the need for teachers to become more involved with and lead in policy so they may share their situated expertise in the classroom with policymakers (Derrington & Anderson, Citation2020), advocate for policies to better serve marginalized and under-resourced students (Bradley-Levine, Citation2018), procure buy-in from teachers on education policy initiatives (Honig, Citation2006), ensure successful policy implementation at district and state levels (Kirsten, Citation2020) and, ultimately, improve student learning outcomes (Shen et al., Citation2020). Research has found that K–12 teachers play an essential role in successful implementation of policy (Van Driel et al., Citation2001); however, teachers and their perspectives in influencing policy creation have been largely absent from this participation (Horsford et al., Citation2019; National Research Council, Citation2014). For instance, in the introduction to their book on teacher leadership, Crowther et al. (Citation2009) made a compelling case for the idea that teacher leaders have unique abilities and perspectives that make them indispensable to any progress in a knowledge society. Inman (Citation2009), among others (Bond, Citation2019; Hite et al., Citation2020; NRC, Citation2014), have called for explicit training to translate the knowledge held by teachers into policy.

The emergence of professional development (PD) programs focused on education policy and offered through professional organizations have made it possible for leaders, specifically teacher leaders, to get involved in policy areas to improve school performance (Mangin & Stoelinga, Citation2009) and advocate for effective education reform (Pennington, Citation2013). The National Academies of Sciences et al. (Citation2020) has stated that “a number of shifts over the past two decades have impacted expectations for K–12 teachers … [and] contribute to the demands on teachers: the policy context [emphasis added], an increasingly diverse student body, and the composition of the teacher workforce itself” (p. 1). If PD leads to teacher leadership (Poekert, Citation2012), without specific PD in policy to grow their leadership skills, there is little ability for teachers to be successful in affecting policy as teacher leaders. Without such PD pathways for acquiring knowledge, skills, and connections to participate in policy, U.S. teachers are mired in a system that lacks both coherence and efficiency; meaning, teachers often rely on factors such as luck (e.g. securing one of the few available fellowships to work for the U.S. Department of Education or on Capitol Hill) to secure the PD experiences necessary to develop their policy knowledge and advocacy skills (Hill, Citation2009; Hite & Milbourne, Citation2022). Therefore, there is a need for structured and robust PD experiences, delivered by experts in policy spaces with authentic engagement in policy, for teachers to develop their knowledge, leadership, and networks for education policy advocacy. With such PD, teachers may become prepared for full participation in the spaces that influence education policy.

The present study explores the development of five teacher leaders in a professional development community so they may garner education policy-focused knowledge, leadership, and networks. By using the theoretical framework of communities of practice and a conceptual framework of necessary PD for policy leadership for teachers, data were collected and analyzed to determine how teachers engaged in novice and expert level policy-advocacy activities.

Theoretical Framework

This study used Lave and Wenger’s (Citation1991) situated learning theory in which expertise, defined as explicit and implicit knowledge, is attained not by behaviorist conceptions of innate talent or linear developmental stages (Ericsson et al., Citation1993). Expertise is garnered through opportunities or legitimate peripheral participation (LPP) to foster the skills needed to obtain expert practices (i.e. knowledge and skills) within a community of practice (CoP). According to Lave and Wenger (Citation1991), when an individual enters the CoP as a novice on the periphery, they engage in scaffolded activities guided by a community-vetted or skilled expert. Novices negotiate meaning within the CoP through increasing meaningful and practical experiences (i.e. LPP). Mastery or expertise may be obtained through this process, provided the learner has truly authentic and ample experiences to participate as well as an earnest desire to obtain the situated expertise (Wenger, Citation1998). As a unique skill set, “situated expertise encompasses not only the situatedness of practices and processes, but also their political (and potentially transformative) dimensions in tracing power imbalances (Vienni-Baptista et al., Citation2022, p.1); situated expertise is vitally important to engaging in policy, in which power and politics are implicit to policy processes. To achieve this aim, the CoP must reciprocally provide transparency in what the community practices are that novices should obtain (Lave & Wenger, Citation2000). Moreover, one’s cognition is intrinsically coupled with the specific experience/s from LPP, evidencing the critical importance of one’s environment for situated learning (Durning & Artino, Citation2011). Situated learning occurs when the novice becomes more centrally involved in the practices of the CoP while becoming more aware of the nuance within the activities; this interaction develops their perception of self and recognition within the CoP (Lave & Wenger, Citation1991). Growth and learning from LPP can be observed by the community members and reflected upon by the novice alike, providing vital insight to the situated learning process and outcomes. This perspective is compelling as it acknowledges the power of culturally embedded activity, where the “acquisition of knowledge is contextually tied to the learning situation” (Gessler, Citation2009, p. 1611). This may explain why the apprentice-based student-teaching experience has long been an important bulwark in teacher induction programs (Koskela & Ganser, Citation1998; Tableacbnick & Zeichner, 1984). Thus, the situative approach has been lauded for illuminating how “classrooms and other learning environments afford opportunities for productive learning” (Anderson et al., Citation2000, p. 12).

Conceptual Framework

Certain PD programs may serve as these situative “learning environments,” in which experts provide scaffolded LPP such to impart upon novices important knowledge, skills, and relationships of a specific CoP. One example of this PD is in teacher leadership. Notably, many teacher leadership programs focus on the extremes of experience (i.e. teach PLUS for new teachers and the Albert Einstein Distinguished Educator Fellowship for experienced teachers). To help understand what type of advocacy is needed, Aydarova et al. (Citation2022) found in a study of teacher educators engaging in policy advocacy activities, a large portion of their work was in relationship building with policymakers and engaging with the public on points of advocacy. Research suggests novice teachers are understandably engaged in learning the CoP of teaching, whereas in-service teachers that are in the ‘middle’ of their careers may be an ideal audience for policy-focused PD. These teachers hold considerable knowledge of and leadership in their craft as well as prior experiences with cultivating and sustaining networks within their local community (Baker-Doyle, Citation2017), and are connected to their communities (Velasco et al., Citation2023) for the type of work that Aydarova et al. (Citation2022) suggested is needed for effective advocacy in education.

To determine what the PD needs are for experienced classroom teachers, it is important to discern in what leadership activities they are engaged and to what extent, if any, those leadership activities relate to policy and advocacy. Dagen et al. (Citation2017, p. 325) studied perceptions of teacher leadership among national board-certified teachers, described by the authors as “a high-quality professional learning experience for [K–12] educators. The certification [process] requires teachers to engage in rigorous reflection on their understanding of pedagogy, student achievement, and content knowledge” from videos of their practice, student work samples, written narratives, and a proctored content assessment. Among the 261 national board-certified teachers sampled, they found that the leadership category teachers had significantly reported engaging in the least was in advocacy. Although the researchers did not explore why, it does suggest that teacher leaders, at a national scale, are rarely engaging in advocacy as a part of their leadership activities. To better understand the impact on teachers from PD specific to policy and advocacy, Velasco et al. (Citation2022) studied a PD fellowship program that intended to develop STEM education advocates from a cadre of nationally acclaimed STEM teachers (i.e. recipients of the Presidential Award for Excellence in Mathematics and Science Teaching or PAEMST). Velasco et al. (Citation2022) found that most salient affordance, as reported by participating teachers, was in their self-efficacy to engage in advocacy activities for STEM education. In a follow up study of these same teachers by Velasco and Hite (Citation2022), the authors examined if and how these teachers continued their advocacy during the apex of the COVID-19 pandemic (2020–2021), they had shifted their advocacy in communicating with policymakers from face-to-face to online (Twitter) and developing PD to help colleagues adjust to the change in modality of K–12 teaching from face-to-face and online, suggesting longevity of their PD to adapted and novel advocacy activities. These studies affirmed Poekert’s (Citation2012) relationships between specific PD and teacher leadership actions and extended his work by suggesting the PD has longevity for teachers who participate in policy-advocacy PD.

The literature suggests that teachers are in need of PD to engage in policy-advocacy activities and asks the question of what type of PD experience would best suit their professional development. In their report on professionally developing teachers to meet the challenges of the modern K–12 school, NASEM concluded that, for in-service teachers, “evidence of effective PD tends to come from research on small-scale interventions designed and led by experts (or in some instances, PD designed by experts and led by local facilitators trained by experts)” (NASEM, Citation2020, p. 154). The statement from NASEM suggests that CoPs are an ideal vehicle for providing PD to experienced teachers. This review of literature indicates that experienced teachers may benefit from expert-led PD that leverages their situated knowledge of teaching and learning is warranted so they may apply their classroom-based experiences to a new domain of education policy-advocacy. Then, K–12 teachers would obtain the specific knowledges in policy, situated leadership skills in policy, and access to policy networks, so they may apply said knowledge, build relationships with policymakers and stakeholders to be effective in education policy spaces.

Our research explores an aspect of teachers’ development in policy knowledge, skills via leadership and influence by examining sustained LPP in a CoP, known as the Texas Education Policy Fellowship Program [herein, fellowship] which aims to improve teachers’ knowledge in education policy, leadership, and networks to participate in education policy processes. By leveraging best practices (per Miller, Citation2015) in creating collaborative sessions and providing spaces to give their input and receive feedback, the fellowship (Citation2022) is a ten-month PD program in which teachers who hold some interest in policy, among other middle-level leaders (e.g. individuals at levels who hold some leadership responsibility such as principals, informal educators, etc.), participated in online as well as in-person meetings with policy experts and engaged in sessions designed to improve leadership skills and cultivate networks in local and state policy. A notable part of completing the PD program is completion of a policy project, a culminating experience in which the participants develop and implement an intervention aimed at improving an educational outcome of their choosing, typically focusing on enhancing equity, within the K–12 educational communities they serve.

Materials and Methods

Our study examined the growth in teachers’ situated learning in policy knowledge, leadership, and networks from their participation in policy-based LPP experiences within the CoP known, in this case, as the fellowship. The research question for this study asked: What types of novice and/or expert actions (LPP) did teachers report to engage in upon participation in a fellowship (a policy-based CoP with expert guidance) to advance their knowledge, leadership, and networks (situated expertise) in education policy? Within two cohorts of fellows, five teachers had completed the fellowship (including completion of a policy project) and had provided a single in-depth exit interview.

Participants

In reviewing curriculum vitae, submitted as part of the admissions process to the program, the five participants (four female, one male) sampled held a mean of eight years of classroom teaching experience (median is eight, mode is eleven) ranging from three to 14 years. Two participants were certified and working in elementary (K–6) education, two in science and one in mathematics. One participant taught in a mid-size city (of approximately 250,000), the second participant taught in a larger city (approximately 700,000) and the other three participants taught in two of the largest urban centers in Texas (with population levels of three to eight million people). Four participants held ESL certifications and/or were bilingual in Spanish and two had obtained principal certifications (although were practicing classroom teachers). Prior to participating in the fellowship, teachers’ leadership centered in staff PD delivery, instructional coaching, and curriculum development at the school or district level. Notably, all participants reported that their entire teaching career had occurred within the state of Texas; two participants had only taught in one school district. Notably, all but one participant had obtained a doctorate in education or was working toward one while in the PD program. Three had reported engaging in leadership training in their district, but none of those opportunities focused on policy-based leadership. Using race and ethnicity identification provided from each participant, each individual was provided a randomly generated pseudonym for analysis and reporting.

Interview Protocol and Collection

We developed a semi-structured interview protocol to elicit thinking about the experiences fellows had (LPP) during the fellowship program related to their understandings in policy, leadership, and networks, respectively. Interviews were conducted via zoom and up to 45-minutes in length. Given these are termed ‘exit interviews,’ they were two to three months (in July and August) after the completion of the fellowship (in May). The interviews themselves were conducted by two different interviewers, both of whom are former teachers and were trained on the protocol. However, these interviewers did not participate in the implementation of the PD program or any LPP experiences as a means to mitigate positively biased responses among the participants. The interview protocol consisted of 15 questions or prompts—six questions asked about their perceptions of LPP while in the fellowship and nine questions invited participants to share how their policy knowledge, leadership skills and networks had changed or been leveraged to meet their goals and objectives in education policy work (by novice and/or expert activities). The appendix contains the full fifteen item interview protocol and question-by-question alignment to the study’s conceptual 3-pronged framework.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

A deductive content analysis (as prescribed by Hesse-Biber, Citation2016) was used to operationalize the study’s conceptual understanding that the sampled teachers shared in common LPP (provided by the fellowship experience) within the CoP of the fellowship itself as they theoretically advanced from policy novices toward policy expertise. Hence, the conceptual framework generated the three major categories of coding the five interview transcripts: policy knowledge, situated leadership, and network connections in policy, which were loaded as columns into an excel document. In each row, data would be disaggregated by pseudonym (individuals) for greater data visualization. As each interview transcript was read, relevant quotations from the respondents were copied and pasted into the excel document. After the first pass, subcategories were generated by summarizing the essence of the quotation copied and pasted from the interview transcript. As example, cognizance of bills, laws, and the policy process emerged as a subcategory of the category growth in policy knowledge. Subcategories were scrutinized and discussed as being novice or expert activities in policy-advocacy and were labeled as such. Determination of the types of reported activities, novice versus expert LPP, was informed by teacher leadership development work by Smylie and Eckert (Citation2018), York-Barr and Duke (Citation2004), and Poekert et al. (Citation2016), respectively. First, novice activities focused at smaller scales (classroom, school, district) than expert activities. Expert activities occurred at larger scales (regional, national). Second, the targets of teacher leaders’ novice advocacy activities were related to the growth of the individual, whereas teacher leaders’ expert advocacy activities were directed toward teams and organizations. Third, categorization of activities related to how knowledge from PD was internalized and executed, either as activity for personal growth (novice) or activities for sharing knowledge with other teachers and stakeholders (expert). Boxes within the excel spreadsheet were counted by categories and subcategories to develop frequency counts and percentages.

For the interview items that asked how fellows were presently using or planning to apply their LPP experiences after the fellowship in policy-advocacy activities, transcripts were read and highlighted by researchers for evidence of aforementioned activities. Twenty-six quotations from transcripts were identified from a first pass through the data. From those 26 quotations, a second pass established four categories of meaning that described the collective activities. These four categories were: taking on leadership at their school, district, and/or organization; conducting research on behalf of a school, district, organization, or for themselves; efforts to improve equity in the P-20 educational system; and sharing the knowledge, leadership, and networks they have garnered with others (and mainly teachers). A third pass was conducted to condense the participants’ experience within each of these emergent categories and to populate summary descriptive statistics of frequency counts and percentages. Quotations were arranged into a figure, by each participant, to supplement the summary table and provide greater transparency to the coding process of current and future activities.

Trustworthiness and Positionality

A gold standard of qualitative research is adherence to the principles and purpose of trustworthiness ascribed by Lincoln and Guba (Citation1985) of credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability. For credibility, the prolonged engagement of each sampled individual in the PD program provides affirmation that the policy-advocacy activities reported are very likely due to the professional development these teachers received within the programmatic CoP and not from their professional duties or teaching-related experiences, which are largely unrelated to policy work. The use of established CoP theory by Lave and Wenger (Citation1991, Citation2000) affords an element of transferability to the research study as the model was both applicable and appropriate to use as a lens when examining teachers’ LPP experiences and the subsequent development in policy knowledge, leadership, and networks. This applicability to different contexts is important as entities who wish to develop PD programs for teacher leadership in policy can determine which LPP experiences are most generative to nascent policy advocates and how to scaffold and sequence their own LPP experiences. Although “qualitative research does not seek replicability” (Stahl & King, Citation2020, p. 26), qualitative research should be reproducible. Therefore, by providing the full interview protocol (see the Appendix, Supplementary materials) and a step-by-step process of data collection, analysis, and interpretation, we have provided transparency to the reader and added dependability to the research process. Regarding confirmability, the data analysis process we followed also created an audit trail as the original data (quotations from the interview transcripts) were maintained within the data analysis. Evidence of the audit trail is further found in quotations provided from each sampled participant in the findings section and in . Last, but never least, a secondary coder assisted the primary coder in reviewing the data prior to and after coding for reliability purposes.

Regarding positionality, three members of the research team facilitated the program of study and were responsible for crafting the LPP experiences in policy (i.e. securing guest speakers for large group sessions, facilitating small group discussions, providing individualized information and self-reflection on policy, advising on policy ideas and questions). Facilitators were also accountable for meeting programmatic outcomes (e.g. encouraging attendance at fellowship meetings, engagement in policy activities, and completion of a cumulative policy project). Therefore, this unique connection of researchers to the fellowship ensured that each research participant engaged in the PD and verified the activities that participants had reported. Facilitators’ deep knowledge of and experience with the fellowship program also enhanced the development of the exit interview protocol. By this subset of the research team, each question was devised, reviewed, and aligned to the programmatic framework and intended outcomes of garnering policy knowledge, acquiring situated leadership skills, and developing policy networks. To minimize potential avenues of bias in participant data, all interviews were conducted by the remaining two members of the research team who did not: act as a facilitator or guest speaker in the program, engage in any LPP experiences as a fellow themselves, and have any personal or professional relationship to the participants.

Limitations

Lamont and Swidler (Citation2014) contended that “each [methodological] technique has its own limitations and advantages and that a technique does not have agency: all depends on what one does with it, what it is used for” (p. 154), so we have chosen exit interviews as a means for our teacher participants to reflect upon their LPP experiences in policy in the recent past of the program (CoP), connect those experiences to what they are doing and thinking about doing related to policy-advocacy activities in the present and near future, respectively. Semi-structured interviewing has been employed extensively in studies interested in understanding novice-expert interactions and outcomes with teachers (Jin et al., Citation2021, Citation2022; Klassen et al., Citation2018; Liu, Citation2022; Westerman, Citation1991), but this method is not without its limitations.

One potential limitation is the imbalance of power that existed between interviewer and interviewee (Anyan, Citation2013). This is particularly important to note when the purpose of the research was to accurately document novice-expert interactions and the subsequent outcomes from those interactions. To mitigate potentially exaggerated or otherwise hindered responses, the two interviewers were both former teachers, not presented as policy experts, and were never part of the LPP experiences or the CoP of the PD program. Our countermeasure provided an interview space in which participants could relate to the interviewers as teachers and provide their honest recollections from their unshared experiences in the program as well as current and future ideas for policy-advocacy activities. To better understand the impacts of the CoPs long term, longitudinal interviewing (see Nolen et al., Citation2012) would provide a greater understanding of the trajectory of their growth in policy knowledge, leadership, and networking, as well as emergent activities that demonstrate novice and expert proficiency in education policy.

Results

Exactly 116 coded responses from each transcribed interview contributed to the data set. shows a summary of the coding process by category (tied to the conceptual framework), subcategories (emergent policy-advocacy activities related to each category), novice-expert level of each activity (per the theoretical framework) with frequency counts and percentages of each category vis-à-vis the total of all coded data (N = 116) regarding the affordances of LPP within the CoP of the fellowship. Each category of situated learning was represented within the data set with leadership having slightly more codes (n = 41, 35%) than policy knowledge (n = 39, 34%) and networks and networking (n = 36, 31%). The degree of teachers’ situated learning is represented by novice and expert activities as described within the conceptual framework. Policy knowledge had more subcategories (nine) and diverse novice-expert activities (four and four respectively) than the other two categories which had fewer subcategories (i.e. seven and six) and fewer expert activities than novice activities (five to two and four to two, respectively).

Table 1. Coding results by conceptual (categories) and theoretical (novice/expert) frameworks.

To explore the second part of the research question relating to the nature of novice-expert activities from the LPP of the CoP in the PD program, displays the summary of novice and expert activities by category. Participants reported mostly novice policy-advocacy activities (n = 79, 68%) as compared to expert policy advocacy activities (n = 37, 32%). Interestingly, policy leadership activities comprised the majority of the novice activities (n = 32) and the fewest activities at the expert level (n = 9), whereas policy knowledge had the fewest novice activities (n = 22) but held the greatest number expert level activities from any one category (n = 17).

Table 2. Summary of LPP experiences reported in the CoP; disaggregated by novice and expert.

To determine individual affordances among teachers and to visualize any potential sources of variance that may exist within the collective data set, provides a summary of LPP experience among each of the three categories and partitioned by novice versus expert activities by each participant. In regard to representation, Mateo contributed the most data (n = 33, 27%), followed by Angela and Cenisa (n = 25, 22%), Lisa (n = 17, 15%), and Michelle (n = 16, 14%). Michelle and Cenisa reported similar experiences of garnering knowledge in knowledge and leadership and to a lesser extent in networks and networking. Lisa and Mateo reported more holistic LPP experiences balanced among the three categories; Lisa reporting slightly less in networks and networking and Mateo reporting slightly more in that category. Regarding the distribution of novice and expert activities, each teacher reported more novice activities than expert; Michelle reported most novice activities (n = 14, 87% of her reported activities), followed by Cenisa (n = 18, 72% of her reported activities), Mateo (n = 21, 63% of his reported activities), Angela (n = 15, 60% of her reported activities), and Lisa reporting the least (n = 10, 59% of her reported activities).

Table 3. Summary of LPP experiences reported in the CoP; disaggregated by teacher participant.

Growth in Policy Knowledge within CoP Participation

In regard to policy knowledge, specific knowledge gains described by teachers were: a basic knowledge of what policy is and how policy is made; a systemic understanding of education (e.g. how districts interfaced with the state educational agency, how the state interfaced with federal agencies related to education); the lack of teacher and diverse input at the state legislature; how lobbyists operate and exert influence in the policy process; and how important nonprofit organizations were to advocate for education. Novice level understandings were largely relegated to awareness of what policy was, the policy process (of agenda setting, formulation, implementation, and evaluation), and the stakeholders involved at their local levels. Michelle, an elementary teacher, reflected on her time in the CoP by how she “got a better in depth understanding of how policies are developed and the processes that they go through until [it reaches] us as teachers; you know [when we] first hear them … it was great to be a part of that.” Mateo, a science teacher, elaborated on how he garnered his policy knowledge by interacting with “guest speakers who provided great insight on how the policy process works … I was able to fully understand how policies, policies play out and how they go from the different committees onto the floor and so forth.” Not all LPP reported was at the novice level. Cenisa, a math teacher, said, “I didn’t realize how much they [nonprofits] advocate for us [teachers, students]” and Lisa, a science teacher shared, “I think [I will follow] a blend of the not for-profits … to see what happens with their advocacy moving forward.” Novice-to-expert development in this category reflects those once teachers understood the policy process, they were growing more cognizant of the external stakeholders and influences on said policy—both positive and negative influences. Angela typified this development in policy knowledge by saying, “I can say, ‘hey [teachers] look there’s this bill that you know it’s out there … [and] what can we do to help you [policymakers] refine this [legislation]?’ Because not everyone takes the time to read that full [bill] text and that’s when some of those messages get twisted.”

Growth in Policy Leadership within CoP Participation

Related to leadership, aspects of growth related to recognizing the importance of teacher voice; listening to community and stakeholders; evolving self-reliance in locating and interpreting legislation/bills; and applying their leadership in novel spaces or groups. One interesting finding related to leadership is the recognition that leadership in policy meant amplification (e.g. amplifying the voices of a community) rather than representation like that of a politician or administrator. Michelle described her response to this challenge: to “refine my thinking on stakeholders within the education policy as a whole and within education; I think it’s refined by defining more of who could be a stakeholder.” Lisa contributed to this idea of identifying and supporting stakeholders, relating that as she grew “into a leadership role, especially thinking about local or even state advocacy, [I] am making sure that those voices are at the table, [this] is really important.” Cenisa added, “what I found that I can’t move as a leader, is, listen, take it in, think about it. It’s, you know, listening with intent. [So] in leadership, you’re willing to listen to what your community has to say.” A novice-expert divide occurred among teachers who exercised emerging leadership activities (e.g. reporting having more confidence to engage in policy-advocacy work) as compared to advanced leadership activities (i.e. instilling leadership in others and mentoring other teachers in policy-advocacy work). Angela felt empowered relating that “teachers may not know there aren’t a whole lot of opportunities [for leadership]; we may not know how to find those opportunities and all of that, so it really falls to me.” Mateo cited one specific LPP experience in the CoP in which fellows were tasked at the end of their experiences to pen their leadership story, which he said, “allowed me to reflect on what I’ve done throughout the year [and] what can I do to help other teachers other stakeholders” so they too could have generative LPP in policy and engage teachers in policy-advocacy work.

Growth in Policy Networks and Networking within CoP Participation

Teachers’ discussions about networks and networking connected to: the power that coalitions have in advancing policy activities; the multiple avenues one may take to effect change in policy-advocacy work; joining groups to broaden one’s perspective and amplify voices; making new vertical and horizontal connections within one’s school and district; the importance of connecting stakeholders to one another for synergistic policy-advocacy activities; and the importance of following people, organizations, and events to continually improve policy knowledge and maintain their networks. On the latter point, Cenisa remarked, “Now I'm paying attention to more emails, especially when they say ‘Town Hall’ in them or just anything that has trigger words that I know have to do with policies and laws that are affecting us [teachers].” In becoming more policy aware, Cenisa was exercising leadership through vigilance, monitoring networks for policy changes that she can then communicate back to her stakeholders. Similarly, Angela shared that from the CoP she has been monitoring education policy news more at the national level and Lisa has been following up with the contacts she made in the CoP to keep in touch with ongoing education policy processes. An expert level, Michelle reflected on how best practice with stakeholders can and should be scaled: “I think my district as a whole does a great job of interacting with stakeholders here in the local area … We need to do a better job of interacting and involving stakeholders from the State level and international level.” Mateo, who reported the most policy-advocacy activities and at in the networking category (see ), shared many avenues from which he is fostering connections in education policy from following policy analysts online, leveraging committees to disseminate policy information and action, as well as re/engaging with university professors in science labs to create LPP experiences for his science students. He attributed his new passion for forging new relationships and network connections to his newfound confidence in this knowledge and leadership, sharing “now I’m able and that hesitant to take on any roles and be ready to provide any input on my end.”

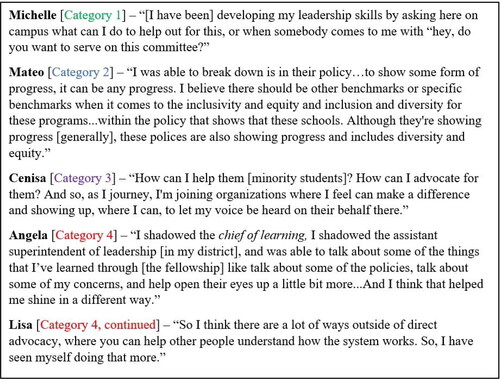

Policy-Advocacy Activities and/or Plans Post CoP Participation

From the analysis of teachers’ reflections from their CoP and LPPs experiences, four salient categories emerged (see ) from the reading and summarizing of 26 coded data. Notably Angela and Mateo contributed the most (62%) to this data set. Thus, not applicable (abbreviated as N/A in the table) was added where there were no data from Michelle, Cenisa, and Lisa respectively to contribute to the categorization schema. provides an understanding to how each teacher is operationalizing or planning to operationalize their CoP experiences and apply the learning from their LPP to their own professional teaching contexts.

Table 4. Reported post fellowship related to their participation in the CoP (N = 26).

The emergent categories and a quotation that exemplifies the category creation is shown in . Category one related to new leadership engagements, centrally on their campuses and in their districts. Michelle’s quote is particularly striking because she was not a reluctant leader; instead, Michelle has been engaging with her district to secure avenues from which she can now exercise her newfound leadership abilities. In category two, three teachers discussed accessing research (e.g. data sets, policy memos, and journal articles) as a tool for their policy-advocacy work. Mateo shared how he is assessing school policies for explicit inclusion of equity and diversity. For category four, teachers described a mission to share their policy knowledge; suggesting that part of the transition from policy novices to expertise is the education of policymakers to relevant policy issues in the classroom and sharing with other teachers’ information about policy and policy processes, so they too may have a larger impact on education. Notably, the fourth area of current and future activity was described as occurring within their own school or their own district.

Discussion

The current study sought to explore the nature of LPP that teachers experienced within a CoP to develop their policy knowledge, leadership, and networks in education policy. The exit interviews of five teachers who participated in such a PD program provided vital insight to the need to include teacher voice in policy and gaps in how such expertise develops. The discussion is differentiated to explore the nature of teacher development in policy, what attributes of the teachers may explain differences in that development, and how that development relates to conceptual models of teacher development in policy spaces to impact the education policy environment.

The Nature of Teacher Development from Policy-Based LPP in a Policy-Focused CoP

Upon analysis of the LPP garnered within the CoP, we found that each category of policy growth was nearly equally represented; leadership was the most reported LPP followed by policy knowledge and then networks (). Conceptually, this trifecta suggests this combination of LPP was equally valuable in providing teachers needed policy information (knowledge), the ability or skills (leadership), and avenues (networks) to engage in policy-advocacy activities. Per the theoretical model, we can anticipate more novice activities in areas in which the participating teachers have less individual knowledge and experiences, such as in how policy works (knowledge) and creating their own policy-networks; the latter of which does not take into account any policy-advocacy that may be done on their behalf through membership to a teacher union (Vieyra et al., Citation2021) or a professional teaching organization (Lambert, Citation2003). Interestingly, when comparing reported novice and expert LPP, the policy knowledge category had equal representation in subcategory type between expert and novice, whereas the leadership and networking categories had fewer at the expert level (). This finding suggests that teachers grew more rapidly in their policy knowledge as compared to leadership and networks. Smit (Citation2005) found that teachers are able to leverage what she termed, ‘local knowledge’ of policy, as a scaffold for learning education policy and policy processes. This finding makes intuitive sense as teachers being charged with implementing policy in the classroom may then draw on those experiences to make sense of policy formation. We may conclude that policy knowledge is the foundation from which teachers can then visualize their leadership in policy and establish or expand their networks for policy work, the latter of which is evidenced in the emerging category two in of their current and future work.

From the foundation of education policy, we turn to the importance of LPP in policy leadership. Findings indicate that the greatest number of LPP was reported in leadership category (n = 41) as compared to the other two categories, however, leadership held the least amount of LPP at the expert level (n = 9; ). This finding suggests that teachers engaged in policy-leadership activity, but mainly locally and not beyond the purview of their own area or district. The bulk of teacher leadership literature focuses on instructional leadership and their activities within the school (Wenner & Campbell, Citation2017). Expert interactions in the leadership category were advocacy at scale (national) and distributing leadership to other teachers. It may be the case that teachers did not choose to engage in expert level leadership, but simply did not have the opportunities to do so. There exists a persistent dearth of opportunity for elementary teachers (Kenjarski, Citation2015), special education (Billingsley, Citation2007), and teachers of STEM subjects (Bundy et al., Citation2019; NRC, Citation2014) to engage in policy leadership, which comprises all the groups of teachers in this sample. Granted teachers can engage in instructional leadership within structures like the professional learning communities of their school (Rasberry & Mahajan, Citation2008), policy-based leadership is often considered as outside of the expected instructional work of a classroom teacher (Hite et al., Citation2020; Smylie, Citation1995). As teachers reported taking on more or expanded leadership roles in their school as well as district (as seen in the first emergent category of ), suggests they are willing and able to move beyond instructional leadership.

The networks and networking category held the fewest reports of LPP among the three categories, although not significantly. Findings indicate that there was the least amount of variance among subcategories (i.e. the least at five and the greatest at seven and mostly at six) when compared to subcategory frequencies in the other two categories of policy knowledge and leadership. This finding suggests teachers were diversifying their policy-based networking into different areas similarly. Lambert (Citation2003) discussed the importance of networking for “teachers [to] see themselves as part of a profession; they find themselves listened to in new ways; they hear and see how others think and interact and, in so doing, change how they perceive themselves as teachers” (p. 427) and teacher leaders. The aforementioned finding may be best understood through, as once policy and leadership were understood, networks and networking which aided in teachers’ application of the aforementioned knowledge and skills, thus supporting their policy-advocacy work (Vieyra & Hite, Citation2023; Yow et al., Citation2021). The emergent category 4 in supports this assertion given the type of teacher-to-teacher and policy-based networking they are or are planning to engage.

The Variance of Teacher Development from Policy-Based LPP in a Policy-Focused CoP

We noted some individual differences as teachers reported policy related LPP during and after the program. Individually, Mateo reported twice as much LPP than Michelle and Lisa individually (). When examining their curriculum vitae, it was noted that Michelle and Lisa held half the amount of teaching experience when compared to Mateo and Angela. Further, Mateo and Angela were also outliers of the group as they reported the most LPP around networking as compared to the other three teachers, emphasizing the importance that Bond (Citation2019) found for teachers to build professional relationships with policy-based stakeholders. A situative model of teacher leadership in policy by Hite and Milbourne (Citation2018) helps to explain how experience in the classroom can advance or stymie teachers’ developmental processes. By chronicling the professional experiences of K–12 STEM master teacher leaders and use of situative learning theory, the STEMMaTe model describes five salient phases of policy focused LPP in which individual teachers advance in their policy leadership from novice to expert levels. The first and most novice phase is their ability to effectively teach their content area (scholastic effectiveness) in the classroom followed by garnering institutional knowledge and memory of their school and system. Lisa and Michelle had reported no present or future experiences related to research (), and from their CVs, they held the fewest years of classroom experience (i.e. seven and three years, respectively). It is likely they are still in the first or second phase of the model, still garnering understandings of school-based and local policies before engaging in research to determine how those policies (do or do not) work, notable activities of the third phase of adaptability and flexibility. It is in this third phase in which teachers employ their scholastic effectiveness and leverage their institutional capacity to fully engage in the LPP on policy, being offered by a policy CoP, toward policy leadership development. This model also helps to explain why Mateo and Angela also reported the most LPP experiences at the expert level (). The STEMMaTe model suggests after the third phase of learning policy, teachers engage in LPP related to emergent and then, strategic policy leadership activities, just as Mateo and Angela had done. It is these strategic teacher leaders in policy that have the ability to have the greatest and most widespread impacts on policy due to their actions that engage policymakers directly and recruit other teachers to policy leadership. Given that strategic leadership often, but does not have to, occur later in the teacher’s teaching career, this study and this model demonstrates that time in classroom is not the best proxy for determining a teacher’s engagement in policy leadership, and there are tangible actions that can be made within the policy-focused CoP to provide the sequenced and adequate LPP needed to aid teachers in fully developing their teacher leadership in policy from a sustained policy PD experience.

Conclusion

Results adhered to extant models of teacher leadership in policy—sampled teachers used their teaching experiences and expertise as the focal point of their policy learning, leadership development, and making connections for future policy-advocacy work. Teachers reported that the policy-focused CoP LPP experience helped them individually to garner knowledge and skills which then were spread to other teachers and policy stakeholders in their nascent policy-focused networks. Programs that wish to develop teacher leadership in policy, through situative learning processes, should acknowledge and intentionally provide both policy knowledge and leadership LPP to ensure teachers not only learn—but also are ready to engage in and disseminate (via new policy networks) their policy knowledge and ideas for advocacy. Thus, the present research uniquely contributes to the literature by providing insight to how teachers garner policy knowledge, acquire situated leadership skills, and expand their networks to influence policy, such as education advocacy activities and amplifying stakeholder voices. And by understanding how this development from novice to expert in policy-advocacy activities occurs, we may also better understand how teacher leadership in policy impacts the education policy ecosystem, from local to national and international levels. This research provides avenues for future research in exploring the finer grained details of teacher leadership in policy, either at the novice or expert level, and following teacher leaders in policy throughout their teaching careers to determine how they, as individuals or groups of policy teacher leaders, influence policy development and implementation in their districts and beyond.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (277.5 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the institutional support of the Center for Innovative Research in Change, Leadership, and Education (CIRCLE) at Texas Tech University.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anyan, F. (2013). The influence of power shifts in data collection and analysis stages: A focus on qualitative research interview. Qualitative Report, 18(18), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2013.1525

- Anderson, J. R., Greeno, J. G., Reder, L. M., & Simon, H. A. (2000). Perspectives on learning, thinking, and activity. Educational Researcher, 29(4), 11–13. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X029004011

- Aydarova, E., Rigney, J., & Dana, N. F. (2022). Playing chess when you only have a couple of pawns: Policy advocacy in teacher education. Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education, 124(9), 199–227. 227. https://doi.org/10.1177/01614681221134762

- Baker-Doyle, K. J. (2017). How can community organizations support urban transformative teacher leadership? Lessons from three successful alliances. The Educational Forum, 81(4), 450–466. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131725.2017.1350242

- Billingsley, B. S. (2007). Recognizing and supporting the critical roles of teachers in special education leadership. Exceptionality, 15(3), 163–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/09362830701503503

- Bradley-Levine, J. (2018). Advocacy as a practice of critical teacher leadership. International Journal of Teacher Leadership, 9(1), 47–62.

- Bond, N. (2019). Effective legislative advocacy: Policy experts’ advice for educators. The Educational Forum, 83(1), 75–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131725.2018.1505992

- Bundy, B., Dahl, J., Guiñals-Kupperman, S., Martino, K., Hengesbach, J., Metzler, J., Smith, T., Spencer, N., Whitehurst, A., Vargas, M., & Vieyra, R. (2019). Aspiring to lead: Physics teacher leaders influencing science education policy. The Physics Teacher, 57(3), 186–189. 189. https://doi.org/10.1119/1.5092483

- Crowther, F., Ferguson, M., & Hann, L. (2009). Developing teacher leaders: How teacher leadership enhances school success. Corwin Press.

- Dagen, A. S., Morewood, A., & Smith, M. L. (2017). Teacher leader model standards and the functions assumed by national board-certified teachers. The Educational Forum, 81(3), 322–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131725.2017.1314572

- Derrington, M. L., & Anderson, L. S. (2020). Expanding the role of teacher leaders: Professional learning for policy advocacy. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 28(68), 68. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.28.4850

- Durning, S. J., & Artino, A. R. (2011). Situativity theory: A perspective on how participants and the environment can interact: AMEE Guide no. 52. Medical Teacher, 33(3), 188–199. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2011.550965

- Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R. T., & Tesch-Römer, C. (1993). The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychological Review, 100(3), 363–406. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.100.3.363

- Gessler, M. (2009). Situated learning and cognitive apprenticeship. In R. Maclean & D. Wilson (Eds.), International handbook of education for the changing world of work (pp. 1611–1625). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-5281-1X.3

- Hesse-Biber, S. N. (2016). The practice of qualitative research: Engaging students in the research process (3rd ed.). Sage Publishing.

- Hill, H. C. (2009). Fixing teacher professional development. Phi Delta Kappan, 90(7), 470–476. https://doi.org/10.1177/003172170909000705

- Hite, R., & Milbourne, J. (2018). A proposed conceptual framework for K–12 STEM Master Teacher (STEMMaTe) development. Education Sciences, 8(4), 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci8040218

- Hite, R., & Milbourne, J. (2022). Divining the professional development experiences of K–12 STEM master teacher leaders in the United States. Professional Development in Education, 48(3), 476–492. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2021.1955733

- Hite, R., Vieyra, R., Milbourne, J., Dou, R., Spuck, T., & Smith, J. F. (2020). Chapter 37: STEM Teacher Leadership in Policy. In C. Johnson, M. Mohr-Schroeder, T. Moore & L. English (Eds.), Handbook of research on STEM education (pp. 470–480). Routledge/Taylor & Francis.

- Honig, M. I. (2006). Complexity and policy implementation: Challenges and opportunities for the field. In M. I. Honig (Ed.), New directions in education policy implementation: Confronting complexity (pp. 1–23). State University of New York Press.

- Horsford, S. D., Scott, J. T., & Anderson, G. L. (2019). The politics of education policy in an era of inequality: Possibilities for democratic schooling. Routledge.

- Inman, M. (2009). Learning to lead: Development for middle‐level leaders in higher education in England and Wales. Professional Development in Education, 35(3), 417–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674580802532654

- Jin, X., Li, T., Meirink, J., van der Want, A., & Admiraal, W. (2021). Learning from novice–expert interaction in teachers’ continuing professional development. Professional Development in Education, 47(5), 745–762. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2019.1651752

- Jin, X., Tigelaar, D., van der Want, A., & Admiraal, W. (2022). Novice teachers’ appraisal of expert feedback in a teacher professional development programme in Chinese vocational education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 112, 103652. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2022.103652

- Kenjarski, M. (2015). Defining teacher leadership: Elementary teachers’ perceptions of teacher leadership and the conditions which influence its development. [Doctoral dissertation]. North Carolina State University. http://repository.lib.ncsu.edu/ir/bitstream/1840.16/10097/1/etd.pdf

- Klassen, R. M., Durksen, T. L., Al Hashmi, W., Kim, L. E., Longden, K., Metsäpelto, R. L., Poikkeus, A.-M., & Györi, J. G. (2018). National context and teacher characteristics: Exploring the critical non-cognitive attributes of novice teachers in four countries. Teaching and Teacher Education, 72, 64–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.03.001

- Koskela, R., & Ganser, T. (1998). The cooperating teacher role and career development. Education, 119(1), 106–107.

- Lambert, L. (2003). Leadership redefined: An evocative context for teacher leadership. School Leadership & Management, 23(4), 421–430. https://doi.org/10.1080/1363243032000150953

- Lamont, M., & Swidler, A. (2014). Methodological pluralism and the possibilities and limits of interviewing. Qualitative Sociology, 37(2), 153–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2022.103652

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (2000). Legitimate peripheral participation in communities of practice. In R. L. Cross & S. B. Israelit (Eds.), Strategic learning in a knowledge economy (pp. 167–182). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-7506-7223-8.50010-1

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage Publishing.

- Liu, P. (2022). Understanding the roles of expert teacher workshops in building teachers’ capacity in Shanghai turnaround primary schools: A teacher’s perspective. Teaching and Teacher Education, 110, 103574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103574

- Lynch, M. (2020, August 17). Teachers must be partners in shaping education policies. The Edvocate. https://www.theedadvocate.org/teachers-must-be-partners-in-shaping-education-policies/

- Mangin, M. M., & Stoelinga, S. R. (2009). The future of instructional teacher leader roles. The Educational Forum, 74(1), 49–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131720903389208

- Miller, L. (2015). School–university partnerships and teacher leadership: Doing it right. The Educational Forum, 79(1), 24–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131720903389208

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2020). Changing expectations for the K-12 teacher workforce: Policies, preservice education, professional development, and the workplace. National Academies Press.

- National Research Council. (2014). Exploring opportunities for STEM teacher leadership: Summary of a convocation. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/18984

- Kirsten, N. (2020). A systematic research review of teachers’ professional development as a policy instrument. Educational Research Review, 31, 100366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2020.100366

- Nolen, S. B., Ward, C. J., & Horn, I. S. (2012). Methods for taking a situative approach to studying the development of motivation, identity, and learning in multiple social contexts. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 27(2), 267–284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-011-0086-1

- Pennington, K. (2013). New organizations, new voices: The landscape of today’s teachers shaping policy Center for American Progress. Retrieved from ERIC database. (ED561062).

- Poekert, P. E. (2012). Teacher leadership and professional development: Examining links between two concepts central to school improvement. Professional Development in Education, 38(2), 169–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2012.657824

- Poekert, P., Alexandrou, A., & Shannon, D. (2016). How teachers become leaders: An internationally validated theoretical model of teacher leadership development. Research in Post-Compulsory Education, 21(4), 307–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/13596748.2016.1226559

- Rasberry, M. A., & Mahajan, G. (2008). From isolation to collaboration: Promoting teacher leadership through PLCs. Center for Teaching Quality.

- Shen, J., Wu, H., Reeves, P., Zheng, Y., Ryan, L., & Anderson, D. (2020). The association between teacher leadership and student achievement: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 31, 100357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2020.100357

- Smit, B. (2005). Teachers, local knowledge, and policy implementation: A qualitative policy-practice inquiry. Education and Urban Society, 37(3), 292–306. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013124505275426

- Smylie, M. A. (1995). New perspectives on teacher leadership. The Elementary School Journal, 96(1), 3–7. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1001662 https://doi.org/10.1086/461811

- Smylie, M. A., & Eckert, J. (2018). Beyond superheroes and advocacy: The pathway of teacher leadership development. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 46(4), 556–577. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143217694893

- Stahl, N. A., & King, J. R. (2020). Expanding approaches for research: Understanding and using trustworthiness in qualitative research. Journal of Developmental Education, 44(1), 26. 28. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45381095

- Tabacbnick, B. R., & Zeichner, K. M. (1984). The impact of the student teaching experience on the development of teacher perspectives. Journal of Teacher Education, 35(6), 28–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/002248718403500608

- Texas Education Policy Fellowship Program. (2022). Home. Texasepfp.org

- Van Driel, J. H., Beijaard, D., & Verloop, N. (2001). Professional development and reform in science education: The role of teachers’ practical knowledge. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 38(2), 137–158. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-2736(200102)38:2<137::AID-TEA1001>3.0.CO;2-U

- Velasco, R., & Hite, R. (2022). Advocacy interrupted: Exploring K-12 STEM teacher leaders’ conceptions of STEM education advocacy before and during COVID-19. The Electronic Journal for Research in Science & Mathematics Education, 26(1), 56–83.

- Velasco, R. C. L., Hite, R., & Milbourne, J. (2022). Exploring advocacy self-efficacy among K-12 STEM teacher leaders. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 20(3), 435–457. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-021-10176-z

- Velasco, R. C. L., Hite, R. L., Milbourne, J. D., & Gottlieb, J. J. (2023). Stand out and speak up: Exploring empowerment perspectives among advocacy activities of STEM teachers in the US. Teacher Development., 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530.2023.2207095

- Vienni-Baptista, B., Goñi Mazzitelli, M., García Bravo, M. H., Rivas Fauré, I., Marín-Vanegas, D. F., & Hidalgo, C. (2022). Situated expertise in integration and implementation processes in Latin America. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 9(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01203-7

- Vieyra, R. E., & Hite, R. (2023). Conceptualizing secondary science teachers as strategic leaders. Teaching Education, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210.2023.2189234

- Vieyra, R., Smith, J. F., & Hite, R. (2021, August) Bold actors in policy spaces: Supporting teachers as change agents through a fellowship for science educators. The Learning Professional, 42(4), 60–64.

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning and identity. Cambridge University Press.

- Wenner, J. A., & Campbell, T. (2017). The theoretical and empirical basis of teacher leadership: A review of the literature. Review of Educational Research, 87(1), 134–171. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654316653478

- Westerman, D. A. (1991). Expert and novice teacher decision making. Journal of Teacher Education, 42(4), 292–305. https://doi.org/10.1177/002248719104200407

- Yow, J. A., Criswell, B. A., Lotter, C., Smith, W. M., Rushton, G. T., Adams, P., Ahrens, S., Hutchinson, A., & Irdam, G. (2021). Program attributes for developing and supporting STEM teacher leaders. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2021.2006794

- York-Barr, J., & Duke, K. (2004). What do we know about teacher leadership? Findings from two decades of scholarship. Review of Educational Research, 74(3), 255–316. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543074003255