ABSTRACT

Did government mines inspectors in late Victorian Britain display overt bias towards employers when assigning blame for fatal underground explosions? Inspectors were closer to managers and coal owners than they were to miners or mine supervisors in terms of status, background, and engineering experience. That inspectors had more in common with management could have led to favouritism or regulatory capture, as was suggested at the time by miners and more recently by historians. To adjudicate these claims, this article applies the technique of qualitative content analysis to the comments of mines inspectors in their published annual reports. The findings reveal that inspectors frequently condemned employers and their representatives, especially after gas and coal dust explosions that took 10 or more lives. By contrast, following blasting explosions, which typically killed only one person, they usually blamed the miners themselves. The available evidence therefore suggests that any discernible pro-employer bias on the part of the inspectorate was limited to smaller explosions where it was easier to ignore systemic factors and deem individual workmen to be at fault.

Introduction

At a public meeting of miners in Glasgow on 22 November 1877, following a devastating explosion at Blantyre colliery in which at least 207 miners died, the British ‘Lib-Lab’ MP Alexander Macdonald, a former miner, excoriated government inspectors of mines in the UK. ‘Human life’, declaimed Macdonald, ‘could not be protected by … dancing in the halls of the rich, or attending at the tables of the great’.Footnote1 The implication is clear: inspectors were too close to the coal owners. Miners and their advocates could be scathing in their assessment of inspectors, sometimes accusing them of neglect of duty or showing undue sympathy towards the coal owners. Suspicions raised in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries about their competence and impartiality are still echoed in academic literature.

The role and independence from management of mines inspectors is a matter of live historical debate. Historians’ views on the UK mines inspectorate are divided. On the one hand, the literature on mine safety in Victorian Britain portrays the inspectors as worthy and even-handed but somewhat downtrodden and frustrated figures (Mills, Citation2016, pp. 99–126). Bartrip (Citation1982, p. 626) describes Victorian factory and mines inspectors as ‘typically overworked, discontented with [their] remuneration, mistrusted by employer and employed, [and] invested with inadequate powers’. Yet, on the other hand, in an article on the Oaks mining disaster of 1866, Ben Harvey (Citation2016) suggests that mines inspectors colluded with, or at least shared the culture of, management. Seven years’ management experience was required under the Mines Act 1855 for an appointment to the inspectorate. Although inspectors would have been ineffective without a thorough grasp of practical mine management, their experience may have conditioned them to adopt a management perspective and thus to be biased in favour of the employers. As Harvey (Citation2016, p. 508) puts it, the background of inspectors ‘increase[d] the likelihood that they could have been part of a manager class.’ Indeed, the head engineer of the Oaks believed that a patronage system was in operation whereby inspectors were appointed at the recommendation of leading coal owners (Harvey, Citation2016, p. 508). In short, it was alleged that Her Majesty’s Inspectors of Mines were, to use modern terminology, captured by the coal owners, setting the scene for disaster at the Oaks and subsequent efforts to deflect blame.Footnote2

Certainly, other perspectives are available. John Braithwaite (Citation1985) argues that in most cases inspectors of mines can achieve better results by seeking the cooperation of firms than by threatening them with punishment. In taking this line, albeit in a multi-country study, Braithwaite implicitly endorses the style of regulation adopted by mines inspectors in late Victorian Britain. However, to evaluate the proposition that members of the inspectorate were biased towards employers, this article assesses whether or not they were unduly inclined to take the side of management over that of the workmen when assigning blame for fatal explosions. Since these tragic events generated greater public interest than other fatal accidents, information about them is abundant. For the purposes of the analysis, blame is defined as going beyond legal culpability – since prosecutions were rare – to include responsibility for any shortcomings that either caused the explosion or created an environment in which an explosion was likely.

We acknowledge the difficulty posed by the lack of an objective standard against which to decide the correctness of an inspector’s comments on the cause of a fatal accident and their subsequent assignment of blame. An explosion – especially a large one – is a complex and often highly destructive event. Reconstructing each explosion to determine who was actually at fault is not feasible. In any event, it is open to question whether the inspectors’ findings should be evaluated using the scientific knowledge and standards of the twenty-first century or those of the late nineteenth century.Footnote3 Given the thorniness of these issues, our task is the more limited one of judging whether or not inspectors were open-minded, eschewed hasty conclusions, and made a genuine effort to be fair when investigating fatal explosions. Our evidence is drawn from the voluminous annual published reports of H.M. Inspectors of Mines.

Economic and safety regulation context

Mining was one of Britain’s major industries in the late nineteenth century. Coal was the fuel of Victorian Britain; it was used in industry, transportation, and the home, and large volumes were sent overseas to markets in Europe and coaling stations used by British ships. Output and employment in the dominant coal section of the mining industry grew rapidly between 1870 and 1900. Other branches of mining were stagnant or declining, or quantitatively insignificant.Footnote4

Mining was a dangerous occupation, comparable in many respects to seafaring. Setting aside occupational diseases, especially those affecting the lungs, which were not understood in the nineteenth century, miners risked life and limb every day. Hazards included the collapse of tunnel roofs or walls, the heavy tubs hauled to and from the shaft, the failure of winding equipment, blasting accidents, underground fires, explosions of firedamp and coal dust, flooding, and defective equipment. Few miners worked for long without at least some injuries or scars to show for it (Rockley, Citation1938, pp. 62–66).

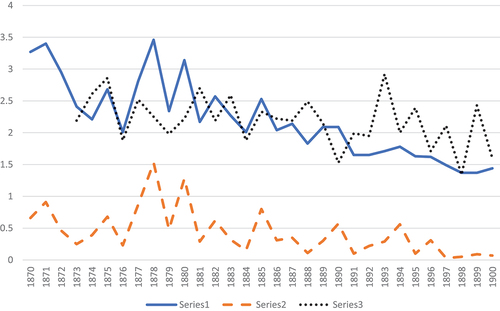

Nevertheless, as shows, the late nineteenth century saw a decline in accident fatality rates in the British coal industry. Accidental deaths below ground from all causes dropped from 2.75 per 1,000 coal miners in 1871 to 1.34 per 1,000 men in 1900. Using the alternative measure of accidental deaths per 1 million metric tons of coal mined, the fall was only slightly less dramatic, from 8.6 per annum in 1871 to 4.6 per annum in 1900 (Silvestre, Citation2022, p. 354). The annual death rate per 1,000 coal miners from firedamp and coal dust explosions also declined over the same period, albeit with wide fluctuations due to the unpredictable influence of disasters. For example, the year 1888 witnessed just one disaster, defined here as an explosion with at least 10 fatalities, and it claimed 30 lives. By contrast, in 1890, two disasters, both in Wales, extinguished a total of 263 lives. Deaths from firedamp and coal dust explosions fell from 0.66 per 1,000 coal miners in 1870 to 0.07 per 1,000 miners in 1900 (Murray & Silvestre, Citation2015, p. 897; Wright, Citation1905, p. 446). It should be noted, however, that the next few years, running up to 1914, were marred by some massive explosions. Annual deaths from all kinds of underground accidents in metalliferous mines fluctuated between 2.92 and 1.60 per 1,000 workers between 1873 and 1900 and did not share in the downward trend enjoyed in coal mining over the same period (Wright, Citation1905, p. 451).

Chart 1. Accidental deaths per 1,000 employees in UK mines 1870–1900.

The Royal Commission on Mines reported in Citation1909 on the type of fatal accidents experienced at mines regulated under the Coal Mines Regulation Act 1887, which included ironstone mines, between 1896 and 1907 (see ). About 1,000 miners per year died in accidents. Almost one-half of these deaths were from falls of roof or sides, and a further one-fifth were from haulage accidents.Footnote5 Deaths from firedamp and/or coal dust explosions accounted for 6.5 per cent of all accidental deaths. Inspectors distinguished between firedamp and coal dust explosions and accidents with explosives, the latter category applying to blasting accidents that did not trigger explosions of gas or coal dust. Most fatal accidents of any type involved no more than one or two deaths, though others could be injured. It was rare for a pure blasting explosion to involve more than one death (Murray & Silvestre, Citation2021). Fatal explosions in metalliferous mines were almost invariably blasting accidents. Although most firedamp and coal dust explosions took under ten lives, on occasion they could kill several hundred miners. Major disasters were infrequent and could distort the picture in any single year, hence the advantage of looking at a longer period.

Table 1. Fatal accidents and their causes in UK coal mines, 1896–1907.

Firedamp and coal dust explosions were largely confined to the coal section of the mining industry. Firedamp (methane) is an inflammable gas that lurks in coal deposits. It seeps out of the coal at a rate depending on local circumstances. Large pockets of firedamp can also be released by falls. Under certain conditions, firedamp can be ignited by a spark or, in the inspectorate’s parlance, an ‘open light’ such as a candle. Between 1870 and 1900, the possibility that explosions could also be caused, or at least propagated by, the ignition of coal dust was taken increasingly seriously, especially in the UK, Belgium, Germany and Austria, though not in France or the United States (Aldrich, Citation1995; Murray & Silvestre, Citation2021).

Compared to the situation pertaining in the United States, the mining industry in the United Kingdom was highly regulated. Legislation in 1842 banned women and girls from working underground in coal mines and regulated the working of boys. Beginning in 1850, inspectors were appointed by the British government to monitor the safety of those working in coal mines. The volume of regulations concerning the safe operation of mines grew over the following half-century, and addressed such matters as ventilation, safety lamps, the training and certification of managers, the reporting of gas levels, the rules for withdrawing men from dangerous places, and the type and use of explosives (Bryan, Citation1975; Mills, Citation2016). Once the principle of regulation was conceded by government, the miners and their political allies, sometimes aided by the inspectors, lobbied to make the regime more comprehensive. Support for further regulation ebbed and flowed in response to the succession of disasters. Regulation and inspection of metalliferous mines commenced under legislation dated 1872, and came under the same organisational umbrella as the inspection of coal mines. Enforcement, however, was generally weak. Successive governments intended for inspectors to nudge mine owners into compliance with safety laws, and not to oversee a punitive regime.

Fatal and other accidents could lead to official prosecution of those deemed in error, but prosecutions were rare except in egregious cases. Coal owners themselves could prosecute supervisors and workmen for breaching safety regulations. An inspector who wished to prosecute a manager or owner required permission from the Home Office. Time spent on prosecutions crowded out other activities including inspection. Not only was it difficult to secure a conviction, but those found guilty of breaching safety regulations faced very modest fines. Prosecuting an individual for manslaughter was another option, but the burden of proof was high and the devastation wrought by an explosion destroyed evidence and often killed potential witnesses. It was also hard for injured workmen or bereaved relatives to take action against employers under the common law. Expensive and intimidating, the legal system operated on the assumption that a worker understood and accepted any risks when taking the job. Moreover, employers could rest easy if the carelessness of the victim or other workers contributed to an accident.Footnote6

Was an improved regime of regulation and inspection the driving force behind the declining rate of accident fatalities, especially in coal mining, in the late nineteenth century? Murray and Silvestre (Citation2015, pp. 894–900) downplay the contribution of regulation, emphasizing instead small-scale (as opposed to macro) technical innovations, such as the adoption of better safety lamps and ventilation techniques. Yet it is undeniable that in some European countries, including Britain, the intensification of regulation was designed to push and sometimes compel coal owners to introduce these innovations, as well as safer explosives such as dynamite and roberite.

Power and perspectives of inspectors, coal owners and miners

The mid-nineteenth century witnessed a gradual shift from a culture in which a job with the British government was regarded as an asset to be exploited for the benefit of the holder to one in which an ethos of public service prevailed (Cawood, Citation2020). Tensions inherent in this transition were particularly acute in the factory inspectorate between the 1830s and the 1850s. The mines inspectorate was fortunate to arrive on the scene a little later when the emphasis was already shifting towards public service. Nevertheless, the Home Office was rather contemptuous of early mines inspectors, concluding that they were second-rate men in search of an easy life. Their willingness to work for much lower salaries than factory inspectors could be interpreted either as confirmation of their poor quality or of their genuine commitment to mine safety (Bartrip, Citation1982, pp. 620–621). But inspectors did not share a single set of attitudes; they varied in their outlook. Mathias Dunn, the first inspector of mines in north-east England, had been a campaigner for greater mine safety for a number of years before his appointment. Herbert Mackworth, his counterpart in South Wales, and the nephew of a baronet, was outspoken on the need for further reform (Mills, Citation2016, pp. 100–111). Others may have been less idealistic, though that need not have made them indifferent.

That many inspectors advocated the extension of safety regulation may also be read in several ways: as proof of genuine concern for the wellbeing of miners, of bureaucratic empire building, or both. Either way, given the limited resources and authority of H.M. Inspectors of Mines, it was not possible for them to deliver a regime of thorough underground inspection and unswerving enforcement of safety regulations. Mines inspectors and their assistants had a herculean task. In 1870 just 12 inspectors of coal and ironstone mines covered the entire UK, which at that time included the whole of Ireland. Each inspector was given an assistant inspector in 1873. Under the Metalliferous Mines Regulation Act 1872 two inspectors were appointed to examine this type of mine. This made a grand total of 26 inspectors (Mills, Citation2016, pp. 123, 151). The size of districts varied, but it is fair to say that each inspector or assistant inspector was responsible for many mines, as well as a raft of other duties. As shown in , James P. Baker, the inspector for South Staffordshire and Worcestershire, disclosed how he and his assistant spent their time in 1878. Between them they conducted 278 inspections, although it is not stated whether every inspection involved descending the pit. Inspectors did not always wait for a complaint to be received before making a mine visit, but no inspector could have observed the whole of each mine. To examine any large mine thoroughly would have taken at least several days, time that was not available.

Table 2. How inspector baker and his assistant disposed of their time in 1878.

In view of time and resource constraints, inspectors had little choice but to rely on moral suasion in their dealings with management. The mines inspectorate endured a Spartan funding regime. Governments insisted on light-handed inspection for reasons of parsimony combined with a reluctance to trespass on the right of coal owners to manage their own businesses. Courts were loath to convict managers when safety regulations were breached, and the fines available were modest (Bartrip, Citation1982, pp. 616–617).Footnote7 Mining was an important industry and the employers influential. Coal owners established the Mining Association of Great Britain in 1854 to represent their interest in Parliament (Church & Outram, Citation1998, p. 46). Even if legislative concessions on safety issues were necessary to accommodate miners and concerned members of the public, neither Liberals nor Conservatives could afford to go too far in upsetting the coal owners. Caution was underpinned by utilitarian ideas. As Medema (Citation2007) explains, leading Victorian economists and philosophers, including John Stuart Mill and Henry Sidgwick, advocated a pragmatic but sceptical approach to state intervention in industrial matters. Where, as in the realm of industrial safety, the free play of market forces worked to the detriment of weaker parties, there were grounds for corrective regulation. At the same time, however, the quality of staff recruited by the regulator was expected to be low because the best candidates would stay in the private sector. The evolution of the mines inspection system shows the marks of these trade-offs. Inspectors received clear instructions from the Home Office not to aggravate coal owners by instituting prosecutions; this, together with the paucity of resources, kept them on a tight leash (Bartrip, Citation1982, p. 618).

By the same token, miners’ trade unions were relatively ephemeral organisations for the bulk of the nineteenth century. Coal miners combined primarily to fight the coal owners in battles over wages. Unions prospered when those battles were successful, but were prone to collapse in the wake of defeats.Footnote8 Despite several attempts to create a national organisation, most activity was at the regional level. The coal miners also campaigned on safety issues where they enjoyed some limited success. Durham and Northumberland suffered some of the worst pit explosions in the first half of the nineteenth century, and it was here that support for reform was most pronounced. Disasters generated widespread sympathy for miners in the press and amongst the general public, enhancing the influence of their representatives until public attention inevitably began to flag. After the Haswell colliery disaster in County Durham, which killed 95 men and boys, in 1844, the lawyer representing the miners hounded the government into appointing scientific experts to investigate the explosion and give evidence at the inquest. The prominent scientists selected, Michael Faraday and Charles Lyell, published a report that recommended a number of safety improvements (James & Rayb, Citation1999). Haswell was followed by a spate of other disasters, and in the late 1840s the government faced growing pressure to act on mine safety. Middle class reformers and the miners themselves lobbied vigorously, although their efforts were poorly coordinated (Mills, Citation2016, pp. 72–84). The Coal Mines Act 1850 introduced a limited regime of safety regulation and inspection, staffed initially by just four inspectors. It was a first step, conceded without much state enthusiasm. Over the ensuing decades, the coal miners continued to advocate for more government intervention in the safety arena.Footnote9 Metalliferous miners were more passive and far less numerous than coal miners, and safety inspection was not extended to their section until the 1870s (Mills, Citation2016, pp. 70–71).

Inspectors often seemed to perform their role in a perfunctory manner, and in consequence attracted some of the resentment from miners that may otherwise have been directed towards the government. As noted, the men at the coalface and their representatives often expressed frustration with inspectors, blaming them as well as the coal owners for accidents. The 1877 Glasgow public meeting’s chairman, John Gillespie, remarked that in his experience ‘the inspector often contented himself with inspecting the workings not in the mine, but on the plan in the office. The men … should insist that the inspectors did their duty.’Footnote10 Another speaker noted that Blantyre had not been inspected regularly. Too much time was spent writing reports and too little underground. Alexander Macdonald MP added that he would continue to use ‘strong expressions against inspectors … until some things that were called inspectors were hurled out of the list of inspectors altogether.’ Footnote11 He charged that some, but not all, inspectors were ‘idle’ and had no intention of fulfilling their duties, and that those miners who wrote to the inspector to complain about dangerous working conditions soon found themselves out of a job because their names were allegedly passed on to management.

An article by J.M. Foster, a working miner, in the June 1885 issue of the periodical The Nineteenth Century was scathing about the mines inspection system and the inspectors themselves. Inspection was a ‘sham’, opined Foster, since despite being ‘a pitman for nearly a score of years,’ he had ‘never seen an inspector underground – nor above ground either’ (Foster, Citation1885, p. 1056). Though safety complaints could be made to the inspector, ‘Not one miner in a hundred knows an inspector’s address’, and, in any case, miners would have been afraid to exercise the right of complaint, for ‘Rightly or wrongly, miners generally entertain the belief that mine owners and inspectors are in collusion’ (Foster, Citation1885, p. 1057). They feared being unable to find further employment. Notably, Foster warned that allegations of collusion were circulating through the mining community. He thought that the selection system was compromised and inspectors appointed on the recommendation of ‘influential friends’ (Foster, Citation1885, p. 1059). Foster recommended that sub-inspectors be drawn from the ranks of the miners themselves, a recurring proposal that was thwarted by government.Footnote12

Historians have suggested that the reasons for pro-employer bias extended beyond particularistic hiring to regulatory capture. Perchard and Gildart (Citation2015) discuss an episode of regulatory capture in the British coal industry that occurred in the early twentieth century, when coal owners hired doctors and scientists to challenge the proposition that inhaling dust – coal dust in particular – was harmful and possibly lethal to miners. With the help of such expertise, the employers were able to delay the passing of legislation to extend compensation to sufferers and their families. In the 1870s, Alexander Macdonald and other critics argued that the inspectorate was in thrall to the employers, which was tantamount to a charge of regulatory capture.

Regulatory capture can occur during the drafting of regulations and the design of enforcement mechanisms, or in their implementation. It can operate through subtle mechanisms to which, arguably, the mines inspectors were susceptible.Footnote13 For one thing, mine inspectors required experience of mine management. Consequently, they were inclined to look upon mine managers as their equals and workmen as their inferiors. They might also have thought of the capitalists who owned the mines as their superiors. Patronising views of miners were also expressed by inspectors. For example, in Colliery Working and Management, H.F. Bulman and Richard Redmayne (Citation1906, p. 57) argued that miners themselves were one of the main hazards underground. Miners, they wrote, were inclined to drink, and were ‘not always the most intelligent and careful of men, and by the default of any one of these, an accident may happen.’ At the time of writing, Redmayne, a mining engineer and former manager of collieries in Northern England and South Africa, was Professor of Mining at Birmingham University. He was appointed the first Chief Inspector of Mines for the United Kingdom in 1908. Redmayne knew miners and respected many of them, but he was not of their world.

Furthermore, under the Mines Inspection Act 1855, a distinction was made between the general safety rules applicable to all coal mines, and special rules to meet the peculiar needs of each district. The inspectors had advocated this change in the system because variations in geological conditions both between and within coalfields affected the risks faced by miners. The negotiation of special rules brought the regulated and the regulator into close proximity. Committees of local coal owners were asked to draft lists of special rules in conjunction with the district inspector, for approval by the Home Secretary, the minister responsible for mines inspection (Bryan, Citation1975, pp. 57–59). Employers often embellished these lists with disciplinary requirements not linked directly to safety (Campbell, Citation1978, p. 107). The coal owners and the inspector sometimes struggled to agree, but even when the debate was heated good relations were soon restored: in one such case in the early 1860s the inspector was presented with a gold snuff box (Boyd, Citation1879, p. 150).

Another potential source of bias was the mining institutes, the professional societies of mining engineers, in which inspectors, coal owners, and managers met on more or less equal terms to debate scientific and technical questions relating to the industry. One of the original goals of the mining institutes was to promote safer working conditions, and considerable attention was given in meetings and publications to this endeavour (Strong, Citation1988). Safety was a major theme of the work of the institutes, especially towards the close of the nineteenth century, when self-contained breathing apparatus emerged as a possible rescue technology (Singleton, Citation2022). Significantly, membership of the institutes did not extend to supervisors, workmen or union officials. Although the institutes performed valuable work, the shared understanding that they fostered between management and inspectors sometimes spilled over into camaraderie. Hugh Johnstone, the coal mine inspector for Staffordshire held the position of president of the South Staffordshire and Warwickshire Institute of Mining Engineers in 1909, an appointment that necessitated the support of prominent coal owners (Johnstone, Citation1910). Johnstone’s selection could just as readily be interpreted as an example of regulatory capture as it could of a mutual concern for mine safety.Footnote14

Insofar as there was regulatory capture of H.M. Inspectors of Mines, the Home Office and the government were complicit through their insistence that inspectors tread warily, and through their denial of sufficient resources to do anything more. On the face of it, there are good reasons to believe that, whether by dint of circumstance, regulatory capture or social background, inspectors were inclined to favour the employers and their agents.

Mines inspection and disaster reporting

One way of evaluating the proposition that inspectors were overtly biased is to examine what they actually recorded and wrote about fatal accidents. Mines inspection generated a vast quantity of information about accidents. Each year a report was written by the inspector in each district, and all fatal accidents were listed in tabular form. Many accidents were also discussed in greater or less detail in the text, and inspectors added general observations on safety concerns. The resulting voluminous annual reports of H.M. Inspectors of Mines are part of the Blue Book series. The reports were explicitly for public and parliamentary consumption. The Victorian state offered the public, or at least those able to read and either to pay or visit a good library, a wealth of information about its activities and the conditions in regulated industries, including textiles, coal, and railways. This constituted an impressive exercise in transparency and accountability, not least in comparison with the furtive government operations of earlier times. The inspectors’ annual reports, together with occasional special reports on disasters such as Blantyre and Senghenydd, supplied information that critics of government policy, including the unions, could use as ammunition (Frankel, Citation2004; Hutter, Citation1992). Such information can also be used to determine how inspectors apportioned blame for fatal explosions between management, supervisors and workmen.

To understand the reports, the chain of command in Britain’s coal mines must be explained. Management included the certificated manager of the mine and any undermanager, plus any more senior figures such as the ‘agent’ or ‘viewer’ who represented the owners, as well as the mine owners (known as coal owners) themselves. The certificated manager was the person legally responsible for what happened at the mine, including the safety of those employed.Footnote15 Coal owners often hid behind the certificated manager in legal proceedings by demonstrating that they had granted that person full authority. The supervisory category included the mine officials who were responsible on a day to day basis for ensuring that the mine was operated safely and that production was maintained, tasks that regularly clashed. The most senior supervisor was the overman, and then came the deputies or firemen who conducted safety inspections before each shift, and the shot-firer who oversaw blasting and in most cases was responsible for firing the shots (Ackers, Citation1994). Charter masters were small independent subcontractors who operated in several districts but were becoming less common in the period examined. Since they hired and supervised teams of miners, but did not participate in mine ownership, they fit into the supervisory group. Finally, everyone else working underground was deemed a workman. In terms of pay and status supervisors were closer to the workmen than to management.

The annual reports split fatal explosions into two types, those arising from explosions of gas, coal dust, or a combination thereof, and those relating to the blasting of coal or rock with explosives. In our subsequent analysis, fatal blasting explosions that also ignited gas or coal dust are placed in the gas and dust category, in line with the convention followed in the reports. The following examples offer a flavour of commentary in the reports and demonstrate how responsibility for fatal explosions can be assigned among the various blame categories.

In some cases the inspector’s opinions are clear-cut. Many blasting fatalities were attributed to the carelessness of the workers directly concerned. For example, in 1892 Inspector Ronaldson complained that ‘Recklessness in handling explosives is too prevalent in the district [West of Scotland] … When men thus wilfully violate the regulations, and thereby expose themselves to unnecessary danger, it is not surprising that they frequently pay the penalty of their rashness with their lives.’Footnote16 At New Boston colliery near Liverpool a miner died under the following circumstances in 1888: ‘As he was charging a shot-hole the cartridge stuck fast, and, contrary to rule, he was trying to force it in with an iron drill when it exploded.’Footnote17 There is no question that the inspector regarded the collier, John Berry, as responsible for his own death. Judgements could sometimes be harsh. For example, in 1878, David Jones, a 59 year old workman at the Welsh Slate mine in Denbighshire was hit on the head by a stone from a shot, dying a few days later. The inspector, Thomas Fanning Evans, concluded that Jones fell victim ‘to the rash carelessness which is unfortunately too common among men whose vocation renders them so familiar with the use of dangerous explosives.’Footnote18 Carelessness by individual workmen was also deemed the cause of some gas and firedamp explosions.

Supervisors could also err in the eyes of the inspector. One such case occurred at Leycett colliery, Staffordshire, in 1874. One collier died and others were badly injured in an explosion ‘caused by the fireman’, Sampson Viggers. According to the inspector’s report, Viggers, who also suffered serious injuries, ‘on finding gas in a drift brush[ed] it out with a piece of brattice cloth (a most improper act and contrary to all decent colliery usage and discipline), although fully aware that a man was working with a naked light in the next place above, and that the gas must pass to that light.’Footnote19 It is noteworthy that, whilst the practice was deprecated by many inspectors, it was permissible to operate mines with open lights – candles – rather than safety lamps in conditions where gas was not a constant threat.

As in the case of Annagher No. 5 colliery in County Tyrone in 1898, some fatal explosions were attributed entirely to the shortcomings of management. Annagher was a small pit on an obscure coalfield, and the number of fatalities, three, was modest, yet the case is instructive. The inspector’s report summarised the evidence presented at the inquest. Annagher was worked from a single shaft, a potentially dangerous arrangement with respect to ventilation, which was permissible only with an exemption from regulations provided by the Home Secretary. The Annagher coal owners had no such exemption. Inspector Gerrard remarked in his concluding damning assessment that there was effectively ‘no provision for ventilation’ at the colliery.Footnote20

Sometimes, the inspectors found fault with several or all parties: management, supervisors and workmen. When something went badly wrong and large numbers died there was often plenty of blame to share around. The death toll at Llanerch colliery, Pontypool, in 1890 was 176. This was an open light case that prompted severe censure from Inspector Martin. Gas was ignited by an open light carried by a miner. Martin stressed that he had ‘pressed’ the owners ‘for some time previous to the explosion to introduce safety-lamps as a precaution’, though the mine was not exceptionally gassy. Despite promising to act, the firm had dragged its feet, with the support of the miners themselves who did not want safety lamps. A fireman also admitted to breaching the regulations mandating the accurate recording of gas levels. Where ‘owners and managers continue to allow the use of naked lights in mines known to give off fire-damp’, remarked Martin, ‘they must expect to be held morally if not culpably responsible when anything occurs, as well as responsible under the Mines Act.’ The inspector found ‘no less remiss’ the workmen who ‘remained at their work with naked lights’ in the knowledge that they were in the presence of gas.Footnote21 In Martin’s view, the miners were not powerless victims, but accomplices in the practices that led to their own demise.

Interpreting the comments of inspectors requires attention to nuance, as is shown by the explosion at Micklefield, Yorkshire in 1896, which killed 63 persons including the undermanager and five deputies. Inspector Wardell concluded that an explosion of fire-damp was propagated by the subsequent ignition of coal dust. Clearly consternated, he stated that he had never seen ‘a trace of fire-damp’ in previous visits to the mine, that the mine was ‘considered to be perfectly safe, and yet, at the end of this long interval of time, this terrible disaster occurs!’Footnote22 The inquest concluded that no-one was to blame, but Wardell continued to feel ‘most serious anxiety’.Footnote23 Naked lights had been used in the pit since it opened 23 years earlier. If such a disaster could happen at an apparently safe mine, he averred, there must be strong grounds for banning naked lights altogether. While this was a comment on mine safety in general rather than Micklefield in particular, Wardell proceeded to criticise the inadequate efforts by management at the colliery to counter the accumulation of coal dust: ‘with the experience of recent years, greater care might have been taken with a view to its removal’.Footnote24 Micklefield was ultimately a case in which the employer was to blame.

Inspectors did not always reach a firm judgement on responsibility for a fatal explosion. The St. Helen’s, Cumberland, disaster of 1888, which killed an undermanager and 29 workmen, offers an example of ambiguity. This was a fire-damp explosion, amplified by coal dust, and the inquest concluded that it was accidental. The majority of fatalities happened after managers sent in a party to combat a fire by building stoppings to cut off the air supply. Inspector Willis maintained, on the one hand, that ‘such a catastrophe was not expected’, probably because ‘the influence of coal dust in extending explosions of gas and air was not understood’ by officials at St Helen’s or indeed many other mines.Footnote25 On the other hand, he regarded some of the evidence provided by the manager, Johnson, with suspicion.Footnote26 Although uneasy and dissatisfied, the inspector did not explicitly condemn the actions of managers or officials, hence the explosion is assigned to the ambiguous category.

In certain other cases, the inspector did not attempt to allocate blame. Sometimes the responsibility for an explosion could not be determined, particularly when the physical evidence was destroyed and there were no survivors. The Seaham colliery disaster in County Durham in 1880 resulted in 164 fatalities. The devastation underground was such that there was no expert consensus on the location of the initial explosion or its proximate cause. Thomas Bell, the district inspector, did not seek to attribute blame for the disaster. In fact, he seems to have been overwhelmed by the volume of expert and scientific evidence.Footnote27

Pro-employer bias of the inspectorate: a balanced assessment

The annual reports proved that inspectors were expert at collecting, presenting, and explaining data. Still, inspectors had their own corner to defend. No doubt they cast their own activities in the most favourable light and hoped to avoid embarrassing the government. It was not in their interests either to appear callous about loss of life in the wake of disaster, or to provoke the coal owners unduly since their cooperation was needed in the day to day conduct of their duties. Most of all, it was not in the interests of inspectors to admit to any fault or oversight in their own, or their assistants’, inspections. These caveats must be kept in mind when determining exactly how inspectors allocated the blame for fatal explosions in the pages of their reports.

Content analytic method

The data on explosions in the inspectors’ reports are subjected to qualitative content analysis (QCA). QCA is a subset of content analysis, a research method developed within the field of communication studies to systematically analyse recorded and widely available ‘communicative material’ (Mayring, Citation2004, p. 266). The types of historical text to which content analysis is well-suited include newspaper articles, legal judgements, and official reports. The specifically qualitative form of content analysis is distinguishable from its quantitative counterpart in that QCA foregoes using computer-based or statistical techniques to analyse the incidence or salience of certain textual elements, such as keywords or phrases. Instead, manual coding is used to allocate targeted items to a flexible set of analytical categories. Using this QCA procedure, researchers iteratively shape their interpretations and revise their categories as they interact with the textual data. The qualitative content analyst is, therefore, both close to the data and has the leeway to adjust categories in line with their subtleties.Footnote28 As a result, skilful ‘manual content analysis has an important advantage in terms of meaningfulness of the analysis’ (Polizzi, Citation2022, p. 33).

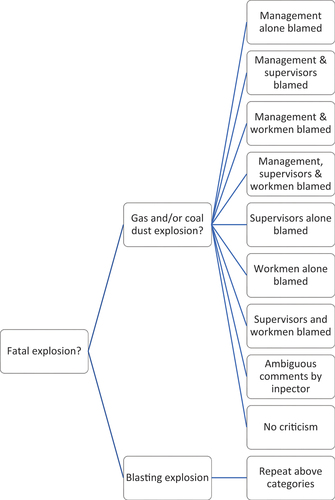

The mechanics of doing QCA centres on the construction and application of a coding frame composed of a number of main analytical categories (Schreier, Citation2012). The frame used in this study is depicted in the decision tree in .

Our first move in developing the frame was to distinguish between different types of fatal explosions. Recorded by the inspectors under different headings, explosions in quarries and boiler explosions were immediately excluded from the analysis since open cast quarries are unlike underground coal mines and boilers typically exploded above ground. That left gas and coal dust explosions, on one side, and blasting explosions on the other. The various actors whom inspectors could blame, either separately or together, were then clearly identified as managers, supervisors and workmen.

Having designated the period 1870 to 1900 as our target, we then piloted our coding frame on an early and a late year in the series − 1878 and 1898. Each fatal explosion was allocated to one of the frame’s analytical categories, which are mutually exclusive. After refining our categories to take account of nuances in the data, especially the number of vague or imprecise inspector comments, we then embedded the frame in a master spreadsheet. This enabled us to manage the sheer volume of data generated for each year. For example, the year 1870 alone brought 85 fatal explosions and several hundred data points. With this procedure intact, we then applied our coding frame to the even years between 1870 and 1900. The 30-year period for the analysis, together with a two-year sampling interval, kept the exercise manageable and is sufficient to avoid selection bias.

Using a minimum of two coders who are familiar with the research topic and industry context is the gold standard for QCA, since it is a stronger way of ensuring that the coding frame has been consistently applied than if just one coder analyses the data. Inter-coder reliability – agreement between two coders – is preferable to intra-coder reliability because ‘two persons differ more’ in their background understandings than ‘one person at two different points in time’ (Schreier, Citation2012, p. 191). We sought this reliability by each of us – this present article’s authors – independently using the coding frame to analyse each report. Accordingly, two coding sheets were generated for each target year. We then worked towards a consensus in cases where there was initial disagreement. This iterative process of reconciliation typically involved exchanging sheets five to ten times before a final version was agreed upon. The point of exhaustively seeking inter-coder agreement was to avoid advancing our own opinions as to where the blame for explosions should lie. Instead, we sought to be systematic and consistent when classifying the judgements of the mines inspectors themselves, in circumstances where, due to the language used or brevity of comment, these were often unclear.

As below shows, the responsibility for fatal explosions has been distributed among our coding frame’s analytical categories. This allocation explicitly acknowledges that, as the preceding section explains, more than one party could have been at fault, and sometimes no fault could be found. In the latter connection, ‘ambiguous’ means that the inspector’s comments were not expressed clearly. Equally, ‘no criticism’ means that the inspector blamed nobody, likely because the accident was deemed a matter of chance – or what passed for bad luck in the late nineteenth century – or because there was insufficient or conflicting evidence.

Table 3. Blame for fatal explosions as attributed by mines inspectors, 1870–1900 (even years only).

Findings

The content analysis provides a clear answer to the question of whether mines inspectors exhibited pro-employer bias. The results are striking. Looking first at all gas and coal dust explosions, management was judged by inspectors to be either wholly or partly to blame in 33 per cent of cases where ambiguous and no blame cases are included in the total number of fatal accidents, and 51 per cent of cases where ambiguous and no blame cases are excluded from consideration. The findings are even stronger for gas and coal dust explosions that took at least 10 lives: management was deemed wholly or partly at fault in 68 per cent of cases where ambiguous or no blame instances are included, and 84 per cent where they are excluded. The situation, however, is different in the blasting sphere: management was deemed wholly or partly at fault in just 4 per cent of cases where ambiguous or no blame instances are included, and 7 per cent where they are excluded.

Clearly, inspectors were more inclined to dismiss deaths due to blasting as the result of carelessness by workers and sometimes supervisors. Blasting accidents were less complex events than gas and coal dust explosions. In the absence of multiple fatalities, it was tempting to reach for the explanation closest to hand, namely worker error. It cannot be denied that careless and reckless behaviour occurred underground. For example, miners and other workers in heavy industries on Clydeside in the mid-twentieth century were inclined to disregard or even court danger (Johnston & McIvor, Citation2004). Similarly, young tin miners took unnecessary risks at work to prove their masculinity, occasionally leading to fatal accidents (Mills, Citation2005). Still, miner bravado is unlikely to be the only accident cause in so many cases. Sheer exhaustion resulting from long hours and hard labour was a factor in some blasting and other explosions. Mining was a brutal occupation and men could not concentrate all of the time. Miners were also at the mercy of the materials and tools, some of which were unsafe, used in blasting. Before the introduction of nitro-glycerine-based stick explosives from the 1870s, the black powder in use was notoriously flammable; a spark from a hand tool struck on rock could set it off. The lighting of fuses was fraught with danger; though explosives such as gelignite were generally safer in this connection than black powder, they too had risks associated with their friability, susceptibility to degradation and tendency to exude noxious fumes (Wegner, Citation2010). Yet the volitional acts involved in setting and detonating explosives lent themselves to making attributions about the behaviour of the individual miner, who was typically the only casualty. To blame miners in these circumstances, therefore, is to ignore the systemic reasons for blasting deaths and thus to commit the fundamental attribution error.Footnote29

By contrast, inspectors did not hold back from criticising management for neglect of ventilation, tolerating poor discipline, and other failings after gas and coal dust explosions. Inspectors were evidently not afraid to criticise, often in strong terms, the management of coal mines after such accidents, and on occasion were prepared, subject to the approval of the Home Office, to institute legal action against the offenders. This was especially the case when the shortcomings of management contributed to numerous fatalities, as at Wood Pit near Wigan in 1878 where 189 men died in an explosion. Supervisors and workmen bore some responsibility for the disaster because they failed to report the presence of gas to management. Even so, Inspector Henry Hall concluded that ‘the method of leading the ventilation in one continuous current over such a long distance … showed a sad want of skill on the part of the management.’Footnote30 The certificated manager of Wood Pit was brought before a magistrate and accused of ‘gross negligence’ and of being ‘unfit to discharge his duties’, but the manager was allowed to retain his certificate, there being some uncertainty over whether he or a more senior manager, the viewer, was the person responsible for the ventilation system.Footnote31 The tone of the inspector’s report suggests that he found it unsatisfactory that no one was held to account by the courts. Inspectors could condemn errant managers in the strongest words, but they could not take them to court without the support of the Home Office, and they could not secure a conviction without proof of illegality.

Inspectors’ preparedness to engage in public condemnation does not, however, render them completely immune to the charge of bias. Inspectors may have said one thing in private and another in their official reports, perhaps because they sought to avoid seeming callous and feared a public backlash. That possibility is raised by an informal survey conducted amongst his colleagues by Inspector Hugh Johnstone in the west Midlands in 1910. It shows that, in the eyes of the participating inspectors, management bore little blame for accidents and deaths.Footnote32 We thus acknowledge that there could be subtle, or not so subtle, differences between how inspectors reflected on accidents in private or among their peers and how they reported on fatal accidents to Parliament. Whether mines inspectors had an ex ante bias towards management is not determinable from the available data. On the balance of probabilities, they did exhibit discernible ex post bias towards management in their reports on small-scale blasting accidents, but emphatically not in their reports on gas or coal dust explosions.

Conclusion

This article largely exonerates mines inspectors from the imputation of bias towards management in their ex post commentary on fatal explosions caused by gas and coal dust. After a fatal firedamp or coal dust explosion the inspector often criticised management, either alone or in conjunction with supervisors and workmen. The higher the number of fatalities, the greater was the propensity to express adverse comments about management. Our analysis does show, however, that some level of pro-employer bias is evident in their writings on underground explosions due to blasting, where they were inclined to disregard the pressures on miners and the inadequacy of the tools available to them.

Miners and their representatives in the trade unions and Parliament were liable to criticise inspectors for neglect of duty or showing favouritism to the coal owners, especially in the wake of major explosions which destroyed the lives of their workmates. Governments accepted that something had to be done to safeguard miners from unsafe conditions, but they were not prepared to spend much money on mine inspection and the enforcement of regulation and were unwilling to step on the toes of the coal owners who were determined to remain masters in their own mines. Inadequate resources and Home Office injunctions to show caution meant that the inspectors had little room to manoeuvre. It is also conceivable that the government found it convenient for inspectors to play the role of scapegoat.

H.M. Inspectors of Mines were closer, both professionally and culturally, to the coal owners and managers than they were to the workforce. Experience of mine management and knowledge of mining engineering were qualifications for the post of inspector. Inspectors were members, sometimes senior members, of the mining institutes, the regional bodies that brought together all on the management side who were interested and qualified in mining engineering. Yet, despite their social conditioning and the constraints under which they worked, inspectors were willing to challenge and condemn reckless employers in the pages of their annual reports, documents that not only went to Parliament but were published for use by journalists and members of the general public.

In summary, our study demonstrates how mines inspectors in the UK between 1870 and 1900 were prepared, notwithstanding their pro-management instincts, to speak up periodically in public for miners and their families. On those occasions, they resisted pressure to give mine managers and owners an easy ride, especially after large numbers of lives had been lost. Much can be learned about industrial relations in coal and other industries by examining the views and behaviour of the official safety inspectors who occupied a sometimes uncomfortable position between the employers and the employed.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

John Singleton

John Singleton is Emeritus Professor of Economic and Business History at Sheffield Hallam University, UK. He has published extensively on British and New Zealand business history, the history of central banking, and disasters including mining accidents and safety. His most recent book, co-edited with Nicole Robertson and Avram Taylor, is 20th century Britain: Economic, cultural and social change published by Routledge in 2023.

James Reveley

James Reveley is Associate Professor of Management in the School of Business at the University of Wollongong. His research interests include banker misconduct, the history and politics of port infrastructure development, and the sociohistorical ontology of business enterprises.

Notes

1. The colliers and colliery disasters. Public meeting in Glasgow. Glasgow Herald, 23 November 1877, p. 4.

2. Regulatory capture is discussed in more detail below.

3. For a recent survey of disasters in Indian coal mines since 1900s which deals, albeit in a less explicit way, with similar difficulties, see Sahu and Mishra (Citation2023).

4. Coal production doubled from 115 million metric tons in 1870 to 229 million metric tons in 1900. Output of iron ore was around 14.5 million metric tons per annum at the beginning and the end of this period. Lead and tin mining were small and declining operations. The number of coal miners increased from 351,000 in 1870 to 780,000 in 1900 (Mitchell, Citation1971, p. 118, Citation2007, pp. 168, 466, 482–483, 490–491).

5. On roof falls, see Aldrich (Citation2016).

6. Despite several half-hearted changes to the law over the course of the century, it was not until the Workmen’s Compensation Act 1897 that a standard procedure was put in place for injured workers and the bereaved to obtain some financial redress (Lester, Citation2001).

7. When 439 miners died in an explosion at Senghenydd in South Wales in 1913, the manager and owners received fines equivalent to 1 shilling 1 ½ pence (under £0.06) per fatality (Wilkinson, Citation2013/14, p. 33).

8. For a recent account of the emergence of trade unionism on one coalfield see Stanley (Citation2020).

9. For a contemporary account, see Boyd (Citation1879).

10. The colliers and colliery disasters. Public meeting in Glasgow. Glasgow Herald, 23 November 1877, p. 4.

11. The colliers and colliery disasters. Public meeting in Glasgow. Glasgow Herald, 23 November 1877, p. 4.

12. From 1872 miners were permitted by law to conduct inspections of their own mines, but such inspections were independent of the official regime and workmen inspectors had no official status.

13. Our concern here is mainly with the presence or absence of capture effected through contact between inspectors and employers, rather than any capture by the employers of the legislative process or policy-making within the Home Office.

14. On the cultural capture of regulators, see Carpenter and Moss (Citation2014).

15. The certificated manager was also an agent in a more general sense and in relation to principal-agent theory.

16. Ronaldson, J.M. (1893). Report upon the inspection of mines in the western district of Scotland for the year ending 31st December 1892, C. 6986-III. HMSO, pp. 1–35.

17. Hall, H. (1889). Report of H.M. Inspector of Mines for the Liverpool district (No. 7) for the year 1888, C. 5779-VI. HMSO, pp. 1–38.

18. Inspectors of Mines (1879). Reports of the Inspectors of Mines for the year 1878, C. 2321. HMSO, pp. 447, 449.

19. Inspectors of Mines (1875). Reports of the Inspectors of Mines for the year 1874, C. 1216. HMSO, p. 100.

20. Gerrard, J. (1899). Reports of H.M. Inspector of Mines for the north and east Lancashire and Ireland district (no. 6) for the year 1898, C. 9264, VIII. HMSO, pp. 1–56.

21. Some miners opposed the use of safety lamps because they spread less light than candles. Martin, J.S. (1891). Report of H.M. Inspector of Mines for the south-western district (no. 12) for the year 1890, C. 6346-XI. HMSO, pp. 1–60.

22. Wardell, F.N. (1897). Reports of H.M. Inspector of Mines for the Yorkshire and Lincolnshire district (no. 5) for the year 1896, C. 8450-XI. HMSO, pp. 1–44.

23. Wardell, F.N. (1897). Reports of H.M. Inspector of Mines for the Yorkshire and Lincolnshire District (No. 5) for the Year 1896, C. 8450-XI. HMSO, p. 21.

24. Wardell, F.N. (1897). Reports of H.M. Inspector of Mines for the Yorkshire and Lincolnshire district (no. 5) for the year 1896, C. 8450-XI. HMSO, p. 21.

25. Willis, J. (1889). Reports of H.M. Inspector of Mines for the Newcastle district (no. 3) for the year 1888, C. 5779-II. HMSO, pp. 1–39.

26. Willis, J. (1889). Reports of H.M. Inspector of Mines for the Newcastle district (no. 3) for the year 1888, C. 5779-II. HMSO, p. 7.

27. Inspectors of Mines (1881). Reports of the Inspectors of Mines for the year 1880, C. 2903. HMSO, pp. 414–432.

28. Unlike the quantitative approach, the qualitative content analytic method allows for the researcher’s ‘system of categories’ to be ‘revised in the course of the analysis’ as it is ‘flexibly adapted to the material’ (Mayring, Citation2004, p. 269).

29. The fundamental attribution error refers to the tendency to attribute perceived worker failings to internal psychological states rather than to the environing context in which they work or to the specific work situation. For a discussion of this concept and a cognate example of how it can be applied in labour history, see Davison and Smothers (Citation2015).

30. Inspectors of Mines (1879). Reports of the Inspectors of Mines for the year 1878, C. 2321. HMSO, p. 371.

31. Inspectors of Mines (1879). Reports of the Inspectors of Mines for the year 1878, C. 2321. HMSO, p. 373.

32. The survey of inspectors’ opinions on the causes of fatal and nonfatal accidents in the West Midlands found as follows: 1.27 per cent of accidents were attributed to defective plant, 1.75 per cent to neglect or breach of rule by officials, 9.08 per cent to neglect or breach of rules by workmen, and 35.03 per cent to ‘causes which were preventible [sic] by the exercise of greater caution on the part of the persons killed or injured, or of their fellow workmen’, while 52.87 per cent were unpreventable (Johnstone, Citation1910, pp. 101–102). Inspector Johnstone did not say whether the category of officials included managers, and the survey was confined to one corner of the UK coalfield.

References

- Ackers, P. (1994). Colliery deputies in the British coal industry before nationalization. International Review of Social History, 39(3), 383–414. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002085900011274X

- Aldrich, M. (1995). Preventing ‘the needless peril of the coal mine’: The Bureau of Minesand the campaign against coal mine explosions, 1910-1940. Technology and Culture, 36(3), 483–518. https://doi.org/10.1353/tech.1995.0049

- Aldrich, M. (2016). Engineers attack the ‘no. one killer’ in coal mining: The Bureau of Mines and the promotion of roof bolting 1947-1959. Technology and Culture, 57(1), 80–118. https://doi.org/10.1353/tech.2016.0022

- Bartrip, P. W. J. (1982). British government inspection, 1832-1875: Some observations. The Historical Journal, 25(2), 605–626. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0018246X0001181X

- Boyd, R. N. (1879). Coal mines inspection: It’s history and results. W.H. Allen.

- Braithwaite, J. (1985). To punish or persuade: Enforcement of coal mine safety. State University of New York Press.

- Bryan, S. A. M. (1975). The evolution of health and safety in mines. Mine and Quarry.

- Bulman, H. F., & Redmayne, R. A. S. (1906). Colliery working and management (2nd ed.). Crosby Lockwood and Son.

- Campbell, A. B. (1978). The Lanarkshire miners: A social history of their trade unions,1775-1974. John Donald.

- Carpenter, D., & Moss, D. A. (2014). Introduction. In D. Carpenter & D. A. Moss (Eds.), Preventing regulatory capture: Special interest influence and how to limit it (pp. 1–22). Cambridge University Press.

- Cawood, I. (2020). Corruption and the public service ethos in mid-victorian administration: The case of leonard horner and the factory office. The English Historical Review, 135(575), 860–891. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehr/ceaa249

- Church, R., & Outram, Q. (1998). Strikes and solidarity: Coalfield conflict in Britain 1886-1966. Cambridge University Press.

- Davison, H. K., & Smothers, J. (2015). How theory X style of management arose from a fundamental attribution error. Journal of Management History, 21(2), 210–231. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMH-03-2014-0073

- Foster, J. M. (1885). Mining inspection a sham. The Nineteenth Century, 17(100), 1055–1063.

- Frankel, O. (2004). Blue books and the Victorian reader. Victorian Studies, 46(2), 308–318. https://doi.org/10.2979/VIC.2004.46.2.308

- Harvey, B. (2016). The Oaks colliery disaster of 1866: A case study in responsibility. Business History, 58(4), 501–531. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2015.1086342

- Hutter, B. M. (1992). Public accident inquiries: The case of the railway inspectorate. Public Administration, 70(Summer), 177–192. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.1992.tb00933.x

- James, F. A. J. L., & Rayb, M. (1999). Science in the pits: Michael Faraday, Charles Lyell and the Home Office enquiry into the explosion at haswell colliery, country [sic] Durham, in 1844. History and Technology, 15(3), 213–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/07341519908581947

- Johnstone, H. (1910). Presidential address. Transactions of the Institution of Mining Engineers, 38, 92–103.

- Johnston, R., & McIvor, A. (2004). Dangerous work, hard men and broken bodies: Masculinity in the clydeside heavy industries, c. 1930s-1970s. Labour History Review, 69(2), 135–151. https://doi.org/10.3828/lhr.69.2.135

- Lester, V. M. (2001). The employers’ liability/workmen’s compensation debate of the 1890s revisited. The Historical Journal, 44(2), 471–495. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0018246X01001856

- Mayring, P. (2004). Qualitative content analysis. In U. Flick, E. von Kardorff, & I. Steinke (Eds.), A companion to qualitative research (pp. 266–269). Sage Publications.

- Medema, S. G. (2007). The hesitant hand: Mill, Sidgwick, and the evolution of the theory of market failure. History of Political Economy, 39(3), 331–358. https://doi.org/10.1215/00182702-2007-014

- Mills, C. (2005). A hazardous bargain: Occupational risk in cornish mining 1875-1914. Labour History Review, 70(1), 53–71. https://doi.org/10.3828/lhr.70.1.53

- Mills, C. (2016). Regulating health and safety in the British mining industries, 1800-1914. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315244884

- Mitchell, B. R. (1971). Abstract of British historical statistics. Cambridge University Press.

- Mitchell, B. R. (2007). International historical statistics: Europe 1750-2005 (6th ed.). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Murray, J. E., & Silvestre, J. (2015). Small-scale technologies and European coal mine safety, 1850-1900. The Economic History Review, 68(3), 887–910. https://doi.org/10.1111/ehr.12080

- Murray, J. E., & Silvestre, J. (2021). How do mines explode? Understanding risk in European mining doctrine, 1803-1906. Technology and Culture, 62(3), 780–811. https://doi.org/10.1353/tech.2021.0107

- Perchard, A., & Gildart, K. (2015). ‘Buying brains and experts’: British coal owners, regulatory capture and miners’ health, 1918-1946. Labor History, 56(4), 459–480. https://doi.org/10.1080/0023656X.2016.1086555

- Polizzi, S. (2022). Risk disclosure in the European banking industry: Qualitative and quantitative content analysis methodologies. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-93967-0

- Rockley, B. E. (1938). Report of the royal commission on safety in coal mines, Cmd. 5890. HMSO.

- Royal Commission on Mines. (1909). Second report, Cd. 4820. HMSO.

- Sahu, A., & Mishra, D. P. (2023). Coal mine explosions in India: Management failure, safety lapses and mitigative measures. The Extractive Industries and Society, 14, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2023.101233

- Schreier, M. (2012). Qualitative content analysis in practice. Sage.

- Silvestre, J. (2022). Productivity, mortality, and technology in European and US coal mining, 1800–1913. In P. Gray, J. Hall, R. Wallis Herndon, & J. Silvestre (Eds.), Standard of living: Essays in economics, history, and religion in honor of John E. Murray (pp. 345–371). Springer.

- Singleton, J. (2022). Breathing apparatus for mine rescue in the UK, 1890s–1920s. In P. Gray, J. Hall, R. Wallis Herndon, & J. Silvestre (Eds.), Standard of living: Essays in economics, history, and religion in honor of John E. Murray (pp. 373–394). Springer.

- Stanley, J. W. (2020). The Yorkshire miners 1786-1839: A study of work culture and protest [ Unpublished PhD thesis]. Sheffield Hallam University.

- Strong, G. R. (1988). A history of the institution of mining engineers 1889-1989. Institution of Mining Engineers.

- Wegner, J. H. (2010). Blasting out: Explosives practices in Queensland metalliferous mines, 1870-1920. Australian Economic History Review, 50(2), 193–208. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8446.2010.00301.x

- Wilkinson, A. (2013/14). Each man’s life was worth 1sh 1d 1/2d! The Historian, 120, 33.

- Wright, C. D. (1905). Coal mine labor in Europe. Department of Commerce and Labor.