Abstract

Protestant communities in South India were vocal in dissenting against colonial rule and in expressing their discomfort with the demographic politics of nationalist discourse. Within this context, this paper focuses on young Christian women in Madras, who, in the 1930s and 1940s, articulated an internationalist ethic and a geography of ecumenical belonging that drew on their positioning within internationalist humanitarian, Christian socialist and global student Christian networks. Critiquing the narrowly regional and national geographies within which minoritised communities in South Asia have tended to be studied, I argue that these young women drew on social gospel theology to imagine an expansive international geography of social action, while critiquing their positioning as ‘minorities’ within the emergent Indian nation.

Introduction

In 1940, the student senate of the Women’s Christian College (WCC) in erstwhile Madras (now Chennai) debated the question of going on strike in solidarity with nationalist leaders who had been imprisoned in the preceding year.Footnote1 The late 1930s had been particularly tumultuous in India as the colonial government cracked down on nationalist agitation, which continued even as Britain became embroiled in World War II. In October 1940, Jawaharlal Nehru—who would become independent India’s first prime minister—was arrested in the North Indian town of Gorakhpur. WCC’s annual magazine, The Sunflower, reports that the college’s student senate met subsequently to discuss a possible strike in response.Footnote2 The students at this college—mainly members of South India’s sizeable Christian minority, mostly Protestant or Syrian Christian—were conflicted. While they expressed strong anti-colonial sentiments, like many Indian Christians, they had reservations about the ethical value of civil disobedience, as well as about nationalism as its motivating ideology. At their meeting, the students chose not to go on protest, and instead resolved to hold a prayer meeting and form a Politics Club at which they would explore the possibilities that a Christian internationalist ethic offered for anti-colonial mobilisation. This moment encapsulates a set of discourses that grew in prominence in early twentieth century South India, linking an ethic of virtuous individualism with an internationalist geography of a Christian ecumene. In this, I argue, young Christian women in India articulated the international as a site of refusal, both of liberal imperialist missionary discourse and of a predominantly Hindu and upper-caste Indian nationalism.

Anti-colonial mobilisation in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries is now widely acknowledged to have been trans-imperial and transnational. Beyond territorial nationalism, scholars have shown that colonised communities made claims to universalism through movements that undermined colonial geopolitics and established solidarities among non-Western communities.Footnote3 Indeed, nationalism and internationalism were not necessarily exclusive of each other: the nation-state became, in many contexts, a mode through which international anti-colonial solidarities could be established.Footnote4 In India, Dalit, indigenous, Muslim and Christian communities—minorities in an emergent and predominantly Hindu India—saw nationalism as a site of negotiation and struggle, often looking to transnational projects of liberation as a way of thinking beyond the nation-state.Footnote5 A growing scholarship draws attention to the ways in which the spatiality of these struggles inscribed internationalist geographies of political resistance—for instance, in Dalit collaborations with Black and Pan-Africanist movements.Footnote6 This work deprovincialises communal politics as speaking not only to proximate political geographies, but as networked with and shaping discourses circulated nationally and globally.

Simultaneously, scholars of religion and public life in colonial India have argued that anxieties about being seen as inadequately Indian fundamentally shaped the experience of Indian Christians in the late colonial years.Footnote7 Chandra Mallampalli argues that this sense of being an outsider to the nation diagrams the intimate experience of family disinheritance that many early converts faced.Footnote8 This history of disinheritance, and court cases centring on converts’ rights to inherit family property, further resulted by the late nineteenth century in Indian Christians coming under English civil law, while Hindu and Muslim matters of marriage and family life were governed under religious personal law.Footnote9 This, alongside Indian Christians’ exclusion from nineteenth century orientalist discourse about India’s religious culture, meant that this community tended to be positioned on the margins of the national imagination. Indian Christians’ encounter with international and pacifist Christianity in the inter-War years was shaped by this position of alterity in a predominantly Hindu India, as a community composed mostly of converts from the lowest castes.Footnote10

The educated Protestant and Syrian Christian elite who attended institutions like Women’s Christian College engaged communalism in this context as a site of self-construction vis-à-vis the emergent nation-state. The ‘communal problem’ of the 1930s and 1940s has been widely commented on by historians of modern and contemporary India. In much of this scholarship, communalism indexes conflict between majority and minority communities.Footnote11 In this paper, I use ‘communalism’ as Protestant Christians did in the early twentieth century, and as it appears in discussions on this issue at Women’s Christian College, which is the focus of this paper. ‘Communalism’ in this meaning addresses not only conflict, but the vexed question of what it meant to construct an identity around religious community in an emergent Indian nation based on the colonial enumeration practices that undergirded minority status.Footnote12 Chandra Mallampalli has argued that Protestant elites in early twentieth century South India refused communalisation—being rendered into a distinct and enumerable minority—on the grounds that Christian identity was not static and enumerable.Footnote13 This notwithstanding, the Protestant Christian position was not identical with the Congress nationalist view that sought to leave the question of communal representation till after political independence had been achieved.Footnote14 Rather, as I show below, in rejecting communalisation within the territorial terms of the nation-state, Indian Christians also articulated a critique of nationalism, looking instead to an international ecumene—an interconnected community of Christians across denominations—as a site of belonging.

Through an examination of the writing of students at Women’s Christian College produced in the early twentieth century, this paper focuses on how this discourse of transcending communalism for an international geography of Christian ecumene shaped the making of young womanhood in South India. Over the course of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Indian Christian women drew on connections with internationalist Christian organisations to consolidate social mobility and respectability through practices of embodied and domestic transformation.Footnote15 Simultaneously, as Bible women, teachers and social workers, they articulated a sphere of agency for themselves that was distinct from—and sometimes at odds with—the missionary project of constructing respectable Christian womanhood in India. This dynamic was forged on the ground of an ‘imperial social formation’Footnote16—a sphere of encounter for white and colonised women—that the transnational turn in feminist history has shown was integral to gendered subject-making for metropolitan and colonial women alike. In this, Indian Christian women’s framing of the international differed from the feminist internationalism of organisations like the All-India Women’s Conference, the Women’s International Democratic Federation, and the All-Asia Women’s Conferences.Footnote17 The central difference, as I show in this paper, was that the internationalism that emerged from institutions like the WCC rested on the ethic of Christian virtuous individualism rather than on collectivisation. This centring of individual ethical practice would also, as I show below, allow Christian internationalism as articulated from the WCC to engage in refusals of proximate geographies of collective communal struggle, for a transcendent vision of an international Christian community. In this, Indian Christian women also enacted their gendered positioning by claiming for themselves a sphere of social action that was firmly located in the intimate world of domestic reform. As I show in this article, the young women at WCC channelled their desire for political change into their work as Sunday School teachers, social workers in slums, and experts in home science. Through this, they iterated a distinctly modern Indian womanhood that was nevertheless not tethered to the national geography that ‘new womanhood’ in late colonial India has tended to be identified with, but was instead oriented towards an international Christian ecumene.

In the sections to come, this paper will begin by unpacking Indian Christians’ location within contestations over nation and territory in early twentieth century India, before going on to address gender and the case of the WCC as a site where the international was articulated by young women. The paper then goes on to discuss two major sites on which ideas about young womanhood, nation and territory, and religion all converged: that of religious conversion and of social work.

Nation, territory and Christians in India

Indian nationalist discourse as it emerged in the early twentieth century was founded on the argument that India had always been a singular entity: an idea advanced in Jawaharlal Nehru’s Discovery of India, among other texts. This ‘fundamental’ unity was not merely advanced as a demonstrable fact but as axiomatic.Footnote18 The unqualified ‘Indian’ subject that emerged from this account was the universal at the heart of a counter-discourse to British colonial characterisations of India as lacking in a national character, and Indians as necessarily racially particular subjects mired in an unshakeable oriental destiny.Footnote19 In the context of this vision, criticism of the Congress’ upper-caste character and expressions of communal sentiment were often stigmatised as divisive, dangerous and detrimental to the movement for sovereignty from British rule.Footnote20 Indian Christians entered this debate with the growing identification in the early twentieth century between anti-caste mobilisation among members of the Depressed Classes and their conversion to Christianity. Further, Christian communities’ closeness with missionary networks also drew the accusation that they were inadequately nationalist.Footnote21

Debates on how a national community should be identified and territorially defined were also fundamental to the Congress’ position against the award of special electorates in the recently-instituted elections to provincial governments in India for minorities including the Depressed Classes (‘untouchable’ castes), Muslims and Christians. This issue—the ‘communal question’—came to a head at the second session of the Round Table Conference in 1931, where the Gandhi-led Congress rejected the demand for special electorates. The Congress delegation also affirmed the minority status of Muslims and Sikhs while rejecting both Depressed Class and Indian Christian claims to legitimacy as minority communities distinct from caste Hindus.Footnote22 In responding to this, Ambedkar—the leader of the Depressed Classes—and Rao Bahadur Pannir Selvam, the Madras Presidency representative for both Indian Christians and the anti-caste Justice Party, argued that transfer of power under such conditions would not be acceptable to the communities they represented.Footnote23 Speaking at the same committee, Surendra Kumar Datta, a representative of the Indian Christian Association, registered partial dissent from Pannir Selvam. While he affirmed the need to recognise Indian Christians apart from the wider European and Eurasian Christians in India, he rejected the claim to separate electorates.Footnote24 His argument was that Christianity was a personal faith—a matter of an intimate relationship with a god—which could not be represented in demographic terms as enumerable. In the years after the Round Table Conference, and particularly in the 1940s, Bishop V.S. Azariah also wrote and spoke publicly about his doubts as to the Congress’ capacity to represent and act in the best interests of the lowest castes and non-Hindu minorities, expressing his concerns that the separation of Christians from the Depressed Classes wrongly suggested that conversion ended the caste violence of untouchability.Footnote25

In elaborating this discourse, this paper presents an archive of Christian thinking in the early twentieth century that runs against the construction of communalism as a boundary-making practice, centred on the fixing of distinct communities in place, whether in colonial governance, in the material everyday of caste, or through postcolonial nation-making practice. In articulating themselves as an ecumene beyond the nation-state, Indian Christians in the early twentieth century sought to resist their minoritisation within the emergent nation-state by looking to a more expansive territorial imaginary. Driven by social gospel—a movement within Protestant Christianity that emphasised progressive praxis as the basis of theology—internationalism thus allowed Indian Christians to unsettle mainstream nationalist mobilisation, while also critically engaging Christianity’s imbrication with an imperial discourse about ‘culture’. Christian socialism, as an internationalist project, also held significant appeal for Indian Christians, both in the early twentieth century and in the decades after Independence. When the Madras Christian College magazine criticised the nationalist boycott of machine-made cloth in 1919, its editors argued in particular that Gandhi’s rural utopia was detrimental to an emergent global labour movement.Footnote26 This view also appears in the economist John Mathai’s 1922 talk at the WCC, where he is reported to have argued that India’s nationalism was flawed, not only in its embrace of direct action as its method, but also because it was a bourgeois movement, not rooted in the questions of caste and labour that concerned the nation’s working class communities.Footnote27

In a pamphlet on his political and social thought, Eddy Asirvatham, a prominent political scientist and member of the Indian Christian Association in the 1940s and 1950s, argued that laissez faire economics could not be compatible with Christianity as it was practised in India.Footnote28 Positioning Christianity as a religion of social equality, Asirvatham recounts that he and other members of student Christian groups were, in the 1920s, drawn to social gospel theology that saw Christian social action as imperative to the lived experience of the faith.Footnote29 A 1950s pamphlet circulated by the Christava Ashram in Kottayam similarly argues that the benefit of Christianity to India comes from the potential of the social gospel to create an equitable and peace-loving society.Footnote30 Published less than a decade after Indian Independence, this pamphlet argues that nationalism in the previous decade forged a bitter atmosphere, in which Christians were forced to play into the territorial politics of minority rights within an emergent nation-state. Social gospel, with its internationalist vision, the pamphlet argues, would be the most effective way out of this conflict towards peaceful progress.

Social gospel also enabled Indian Christians to distance themselves from the doctrinaire and denominational practice of Christianity within missionary parameters, and the initiation of a project of church indigenisation. Social gospel, thus, functioned as a site on which Indian Christians could consider questions of political pertinence to India through the lens of Christian ethical thinking. An article published in the 1920s in the Indian Student Christian Association’s monthly Student Movement Review elaborates this: ‘…the Church that does not recognise this need for a social gospel remains doomed to poverty of life’.Footnote31 It goes on to argue: ‘We need to abandon soul-stultifying rules in favour of a simple principle—the principle of love that Christ taught us. We need a socialization of our ideals’.Footnote32

Beyond its ideological pertinence to Indian Christians, the transnational institutional infrastructure of social gospel that spanned Britain, the US and European countries—the YMCA and YWCA, the Red Cross and the Fellowship of Reconciliation, as well as educational institutions and hostels for students funded by major Christian philanthropic organisations such as the Rockefeller Foundation in New York—also enabled Indian Christians to access international networks.Footnote33 Indeed, the 1931 Commission on Christian Higher Education in India specifically recommended the founding of hostels in major Indian cities for the purpose of embedding Indian students in such international communities.Footnote34 These encounters allowed young Christians to anchor themselves to an internationalist geography of Christian belonging as they articulated critiques of the Indian Independence movement at home. A 1923 issue of the Indian Student Movement Review includes a section on the Christian student and public life. Having clarified that it was a Christian duty to be involved in the social and political movements of the day, the editors of the review write: ‘It is necessary to protest against an exclusively national view of public questions, to insist that all nations have a claim on our regard, and that in the last resort only “righteousness exalteth a nation”’.Footnote35 The same issue also printed a declaration by the World’s Student Christian Federation of its fundamentally international character and commitment to transcending national concerns towards addressing the spiritual well-being of a shared human community.Footnote36

Gender and Christian internationalism: Women’s Christian College

Gender was a particular focal point of early twentieth century religious modernities in India and informed young Christians’ entanglements with pan-regionalism and internationalism. Christianity in South India shared a complex relationship with projects of colonial and missionary-led social reform and was shaped significantly by the development of Tamil-language reformist literature in the early twentieth century.Footnote37 As scholars like Rupa Viswanath and Eliza Kent have shown, missionaries played a major role in shaping the colonial discourse on caste and social reform in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.Footnote38 In particular, the schools for girls that missionaries founded and the zenana missions that addressed upper-caste women by educating them in their homes shaped both the practice of conversion as well as everyday ethical life in South India. However, these scholars have also shown that the colonial record significantly underestimates the agency of Indian women in shaping the terms of Christian culture in South India in this period. As Bible women, and as members of an emergent elite in this region, Christian women engaged in fraught debates about the ethics—and aesthetics, particularly the body politics of clothing—of modern gendered subjectivity.Footnote39 Publications produced by prominent Indian Christians like Kamala Satthianadhan were read internationally, and shaped national debates on gender and the ‘new woman’.Footnote40 The implications that this had simultaneously for an international politics, and for Christian critiques of nationalism, is evident from this scholarship and from the archival collections on which this paper has drawn. A rich biographical and historical literature on Pandita Ramabai—a Brahman convert to Christianity, driven by her anti-caste commitments—has, for instance, shown that educated converts used theological debates to challenge the racial imaginaries of missiological discourse in India.Footnote41 Ramabai herself drew on her international connections among pacifists in the United States to challenge Anglican orthodoxy and to set up hostels for Indian women in Pune.Footnote42

Historians have shown that women missionaries and social workers claimed for themselves a maternal sphere of intervention in the colonies—as reformers of domestic and intimate life.Footnote43 The work of Indian Bible women from the late nineteenth century advances a similar project of making modern homes and families, albeit often in a distinctly non-missionary register.Footnote44 For instance, Annal Satthianadhan’s Nalla Tai (The Good Mother, written in Tamil) is a manual that advises young mothers on their role in the family not only with regard to their children, but also their marriages and home-keeping.Footnote45 Christian advice literature in this genre is closely aligned with the broader print culture in this period typically associated with the emergence of a companionate marriage norm, and the figure of the ‘new woman’ of colonial modernity.Footnote46 The formalisation of women’s education and growing establishment of schools and colleges in this period might also be positioned within this history of domestic modernity. While it would be an exaggeration to argue that girls were necessarily being educated to be good wives and mothers, institutions like the Women’s Christian College, which is the focus of this paper, sought explicitly to model a modern domestic space for its students.Footnote47 The WCC would also become a centre for the study of Home Science in India: a field that not only educated young middle-class women to become efficient managers of their own homes, but also trained them to teach mothers less privileged than themselves about nutrition, hygiene and economical home-keeping.Footnote48

The history of the Women’s Christian College is further exemplary of the international connections that undergirded Christian modernity in India. The WCC was founded in 1915 with the cooperation of 12 missionary societies in Britain and North America. In this, it was paradigmatic of the type of inter-War cooperation that historians have argued shaped American philanthropic intervention in British colonial contexts. In the years following the college’s founding, the Laura Spellman Rockefeller Foundation made a grant towards purchase of land for the college, enabling the fledgling institution to buy one of the grandest houses in Madras.Footnote49 Lucy Peabody, a Massachusetts philanthropist who had known Pandita Ramabai personally, also lobbied for the college’s inclusion in the Seven College Program that the Laura Spellman Rockefeller Foundation had agreed to fund if matching funds could be found from public subscription.Footnote50 Prominent missionaries of the time, such as Ida Scudder, who came from a well-known family of medical missionaries to India, endorsed the college’s effort, and ultimately, most of its funds were raised from contributions by middle-class Christians in the United States.Footnote51

The Seven Colleges of the East, as these institutions were called in periodicals like International Women’s News and Woman’s Work were, further, also engaged in faculty and student exchange programmes with American women’s colleges, including Mount Holyoke, which became a sister institution of the WCC.Footnote52 Issues of the college’s The Sunflower typically include a section on international exchanges for the academic year. In 1952, the magazine notes: ‘We have always been proud of this feature of our college life, for nothing so makes for genuine internationalism as well as a really liberal education, both for students and teachers as a free, honest, happy exchange of ideas between people of different countries, having for their background different civilisations, different traditions and different attitudes to life’.Footnote53 This everyday practice of internationalism as a lived ethic constructed the space of the college as a site from which a Christian community could be imagined as necessarily transcendent of borders.

Further, the WCC was home to a chapter of the Student Christian Movement (SCM) through which its students attended conferences of Christian youth that were convened in the inter-War period in Britain, Europe and North America, as well as meetings of Indian Christian youth in India and Burma (now Myanmar). Issues of The Sunflower note regular SCM events, often of an international tone, for instance, the 1935 ‘SCM sing-song in aid of the Negro Delegation Fund’.Footnote54 An SCM Quadrennial Conference that occurred in Burma in 1938 directly addressed the question of India’s ‘situation’ with the nationalist movement rapidly gaining strength.Footnote55 A report published in The Sunflower argued that the appropriate Christian response from India would be to cultivate friendship over the practice of boycott, and to transcend questions of caste and race, towards creating a global human community.Footnote56 This internationalism was further supported by the college’s interdenominational approach to Christianity: a value that guided the Church of South India’s formation as a distinct body that brought together the Protestant communities of the region after Indian Independence.Footnote57 In both, the WCC fostered a culture of articulating a Christian community beyond the confines of enumeration-focused communalism bounded by the territorial concerns of an emergent, and then new, Indian nation-state.

The Student Christian Movement, the YWCA and their networks also allowed WCC students to access opportunities to participate in public life through the work of international voluntarist institutions. A survey conducted by the editors of The Sunflower in 1935 showed that over 60 percent of alumnae who responded were employed by such organisations either as volunteers or in salaried positions as nurses, teachers and scientists, both in India and elsewhere in the colonial world.Footnote58 This interest in social service and missionary life was explicitly cultivated at the college through its programmes of social service, modelled on the settlement movement in North America and Britain, which took privileged young women to live and work with migrants, refugees and otherwise disadvantaged communities.Footnote59 In Madras, WCC students focused their social service efforts on the city’s urban poor, and also travelled out to visit caste and class marginalised communities elsewhere in South India.Footnote60 Much as the settlement movement did in the West, these roles enabled young Indian women to professionalise the gendered labour of domestic reform that their Bible women antecedents had done.Footnote61 The public roles they inhabited through these activities further positioned them as actively engaged in the work of Christian social transformation, typically focused on the reform of the home and the education of children, while avoiding the conflict-ridden politics of nationalist direct action and student strikes. In this, they materialised a vision of modern womanhood in India that was not oriented towards the emergent nation-state—as in the figure of the ‘national woman’—but instead positioned within an international Christian community of voluntarist service. As I demonstrate below, their positioning as middle-class and educated members of an international Christian community also allowed these young women to cultivate distinction. As they positioned themselves as doers, rather than recipients, of social service, their class mobility was made material through their geographical mobility.

‘Witness Weeks’: Community, enumeration and nation

Protestant Christianity’s popularity in South India revolved centrally around the idea that it enabled a personal spiritual relationship with god, unmediated by ritual practice, and even by family or caste communities. On the one hand, as scholars like Rupa Viswanath have shown, this enabled communities oppressed by caste to reposition themselves within a social order that enslaved them and stigmatised their labour.Footnote62 On the other hand, while many conversions were of whole families or communities, individuals within families could also often be converted, narrating their decision as having emerged from a personal experience of faith.Footnote63 For Bible women, and zenana missionaries who mostly worked with Indian women, this emphasis on a personal relationship with god was crucial to their success in bringing wives and mothers into projects of education and domestic reform, which sometimes, but by no means always, went alongside conversion.Footnote64 In a pamphlet on her work, Annal Satthianadhan, a prominent Bible woman and educator in Madras, writes about Bible reading as a means of orienting housewives away from idle talk and gossip towards morally sophisticated thinking.Footnote65 Bringing women into the Christian fold was, for Satthianadhan, significant not only in that it sometimes led to whole families formally converting, but in that it seeded the work of domestic transformation that she saw as her mission.Footnote66 As more women participated in Bible reading and cultivated an individual relationship with god, Satthianadhan hoped that they would inculcate a desire for moral learning in their daughters and establish companionate relationships with their husbands.Footnote67

This ethic of the individual as the central subject of religious experience was a significant aspect of Indian Christian life at Women’s Christian College. A report of a Student Christian Movement camp at the College reports that students and staff critically considered the meaning of conversion in their political circumstances in the 1930s, at the height of debates on the imperial overtones of mass conversions to Christianity. They report that they agreed that conversion was not to be understood as a legalistic or ritual matter, mediated by law or even the church.Footnote68 Rather, the important thing was ‘witness’: the singular knowledge that the individual self might have of the presence of a Christian god. A further principle of ‘witness’ as the basis for Christian belief, this report argues, is the policy of non-exclusion. To boycott would be to deny the possibility for reform in any person on account of their belonging to a social group defined as oppressive: effectively, this was exclusion from communion, which, the report argued, Christians could not countenance. In a report signed by Indian student representatives, and reprinted in the Madras Guardian in 1936, World Student Christian Federation representatives argued that Christian social action was necessarily inclusive and based on the interdenominational Christian ideal of communion for all, rather than founded on a principle of exclusion.Footnote69 An international Christian ecumene, conceived as a borderless community of those who had experience of witnessing a Christian god and sought to engage in ethical social action on that basis, was, in this rendering, the only appropriate site for a social gospel-driven Christian community.

This brings up an important departure from the missionary theology that social gospel enabled, and that would ultimately become a central tenet of the Church of South India. While missionary-run churches in South India had typically forbidden the taking of communion across denominational lines, Indian Christians in the 1920s and 1930s increasingly advocated universal communion, across and transcendent of denominational difference.Footnote70 The question of communion had also been central to International Christian Conferences that occurred in this period, many of which explored the intersection between national and religious boundaries, arguing ultimately that true Christianity was a religion of universal communion.Footnote71 At ‘Witness Weeks’ at the WCC, everyone received communion, baptised or otherwise, so long as they asserted to having felt the witness of a Christian god in them.Footnote72 Student Christians abstracted this question of universal communion to the broader terrain of Indian politics in articulating their discomfort with direct action. In their reading, to boycott was to refuse communion to a worshipper, and ultimately incompatible with the vision of a borderless ecumene.Footnote73

‘Witness Weeks’ were, in these years, a significant aspect of Indian Christian life and consisted of numerous confessions of ‘witness’ from among many who had not been officially converted.Footnote74 In this discourse, religion was a matter of affective feeling rather than of consistent belief or practice. While official numbers of conversion and the enumerable size of the Christian community in India were integral to missionaries’ evaluation of their success and ability to attract philanthropic funding, Azariah and other Indian leaders in the Protestant community in the early twentieth century advanced a rethinking of who ‘counted’ as a Christian. Mainly, they argued that Christians could not be enumerated and claimed as a political minority because Christianity was a means to individual spiritual liberation rather than a site of identity.Footnote75 In a follow-up report of this SCM meeting, published in The Sunflower, representatives of the Student Christian Movement at the WCC considered the manner in which socialist principles could be brought into Christian faith and practice.Footnote76 They agreed that while Christians could adopt socialist principles of the equitable distribution of wealth and the advancement of social justice for labouring communities, Christian socialism had to necessarily reconfigure the class basis of socialist thought, as well as its foundation in a social theory of conflict. The authors of this report argued that both were incompatible with Christianity: that is, Christian socialists could neither protest like other socialists—through direct action, including civil disobedience and boycotts—nor see themselves as a class at the receiving end of structural oppression to be addressed through strike action. Seeing the nature of Christian social action as fundamentally spiritual, the SCM report recommended that Christian socialists see their work as targeting the individual for spiritual transformation, rather than a class for material change. Individual spiritual transformation that refused the bordering practices of nation and denomination further imbricated these young people within an internationalist geography of Christian social action. To belong to this new progressive Protestant community necessarily meant a repudiation of the provincialism of regional and national fixity, inviting young Christians instead to engage in a practice of deeply intimate transformation that was simultaneously expansive in its geographical scope.

Reform over public demonstration

Demonstrations of protest against something or someone, which have been indulged in disastrously this year made no appeal to our students. But they [students at the WCC] carried through demonstrations of a more positive kind, chiefly within our laboratories, to show either to officials specifically concerned with problems of food supply or to the general public or to interested students, just how ground-nuts and sweet potatoes, and green leafy vegetables, even jungle plants could supplement the reduced rations in rice, wheat, ragi and other grains.Footnote77

This ethic of the virtuous individual also shaped an emphasis on social work over direct action. Located within a project of Christian social mobility through positioning within internationalist humanitarian institutions in South India, this refusal of civil disobedience and strike action served to consolidate gendered respectability, while allowing young Indian Christians to stand apart from nationalists and a radical politics of the communal alike. In refusing the provincialism of the region and the nation, young Christians also sought to transcend the messiness of local communal collectives in favour of a project of self-improvement that refused identification with such ostensibly parochial concerns. In this, the cultivation of an international geography for Christian communal belonging also iterated a practice of distinction, establishing young middle-class Christians as members of a humanitarian liberal elite.

In the early twentieth century, doing social work—in settlement houses, in the practice of ‘slumming’ and in missionary work alike—was a major means through which Christian humanitarian sentiment was expressed as an intimate relation of care, particularly within communities of women concerned with domestic reform. While the word ‘slumming’ does not appear in any of the material on social work at the WCC, ‘citizenship education’ programmes were instituted with similar goals of taking privileged Indian women to spend time in ‘backward’ areas: slums of cities as well as ‘tribal areas’ in regions such as Coimbatore.Footnote78 It is evident that students at the WCC saw themselves as engaging in a project of intimate social reform and uplift in the work they did in disadvantaged areas, positioning their own participation in humanitarian work as a site of distinction, marking them apart from the women who were typically the recipients of their help. Reaching for the international as the sphere of Christian community thus also allowed these young women to reiterate colonial logics that saw less privileged Indians as lacking in the maturity and capacity to participate in a border-transcendent and expansive community. One student writes in 1936: ‘These people are outcaste; they are servants, untouchable and their poverty is appalling, and until economic conditions are better and education is provided for the people, they cannot enter into their full inheritance that is theirs in Christ…’.Footnote79 This view of social work—as redemptive to the doer—shares similarities with the Gandhian ideal.Footnote80 And indeed, Gandhi’s social programme was widely welcomed and accepted at the WCC, even as students rejected aspects of his political programme.Footnote81 The description in the epigraph to this section, of a plan to grow edible plants as supplements to rice, was an explicitly Gandhian ideal in action in the college.Footnote82 It simultaneously speaks to the maternalistic project of domestic social reform that the project of the WCC explicitly cultivated, both by engaging its Indian students as the object of reform and by educating them to become its doers.

In performing social work as a substitute for civil disobedience, Christian women consolidated the positioning of their labour as entirely non-violent and untainted by nationalist aspirations. In explicitly delinking the nation from the performance of social labour, these institutions also located themselves within a global Christian community of youth voluntarism and of women’s missionary work. That this was seen as more productive activity than engagement in strike action is evident from the explicit comparisons that were widely made. For instance, when manual scavengers in Madras went on strike in 1941, the senate of the WCC considered the question of taking up manual scavenging work ‘to shame the scavengers’ back to work.Footnote83 Ultimately, they decided this was in bad taste, and instead went door-to-door educating middle-class citizens in Chennai on practices of waste disposal that might reduce the labour that scavengers typically performed.Footnote84 In the 1960s, when college students in Madras went on strike in support of the anti-Hindi agitations in Tamil Nadu, against the imposition of a national language, students at the WCC yet again elected not to strike. Instead, the then principal, Anna Zachariah, wrote in a letter to the college’s British Board—one of its two governing bodies along with the American Board—that students convened a special meeting to discuss available forms of social work to mitigate the effects of ongoing strike action in the city.Footnote85 In her letter, Zachariah notes the success of the college’s ethical project. She writes specifically that the young women were not instructed to refuse to protest, rather they chose to out of their own free will. Here again, the students are presented as having refused both nationalism as well as the regional and communal stakes of the anti-caste Dravidian movement.

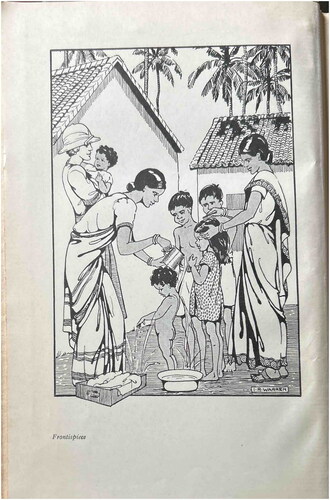

The images that accompany articles in The Sunflower as well as illustrations in books authored by WCC faculty also evoke an imaginary of social work, typically focused on domestic reform and home science, as both necessary labour and positioned within a transnational imaginary of social uplift. In a drawing printed in the memoir of the college’s founding principal, Eleanor McDougall, an Indian woman, wearing a sari, is shown helping a young boy wash himself, while a naked child stands nearby. An Englishwoman standing a few feet away is also participating in this work ().Footnote86

In a pamphlet printed in the 1950s for circulation among philanthropic Christian communities in the UK and the US, an illustration of an Indian woman checking a young, dark-skinned boy’s hand is published with the caption: ‘Students giving simple medical attention to necessitous village children’.Footnote87 This pamphlet further makes the explicit case that such social work is a substitute for the political direction India had taken in the Cold War of refusing to side with Western Europe and North America. In such uncertain times, it argues, a Christian college is an important ballast—necessary for geopolitical stability. Transcending the messy politics of nationalism is, in this rendering, also a refusal of the non-aligned internationalism inaugurated through South-South collaboration in the 1950s. Instead, this discourse articulates the Christian college as a place from which investments in the global circulation of philanthropic capital might be cultivated towards an internationalist geography of Christian virtuous individualism. The effectiveness of this project, it would seem, centrally hinges on abjuring the conflict-driven politics of direct action for social reform focused on home and family life.

Conclusion

In this paper, I have argued that the discourse against direct action in Christian colleges for women drew on inter-War pacifist and Christian internationalist discourse to position strikes and civil disobedience as fundamentally unchristian in that they resulted in the cessation of necessary work. As such, students were encouraged instead to participate in social service within a Christian internationalist paradigm: young women particularly undertaking forms of social work that reinscribed the gendered practice of the settlement movement onto the colonial urban space. In doing so, these institutions enacted a particularly Christian and gendered imaginary of respectable life that was not only referential to the Indian nation but rooted in a transnational history of Christian voluntarism that emerged in the early twentieth century and shaped the ethical imaginary of student life in India. While, on the one hand, this framing allowed Indian Christians to resist the missiological emphasis on enumeration, on the other, it also enabled distancing from a radical politics of the communal, for instance, labourers’ strikes and the anti-caste Dravidian movement.

In concluding, I draw attention to the terms on which the project of transcending proximate communal struggles for an internationalist communal imaginary through Protestant individualism converged with Hindu upper-caste posturing towards caste transcendence. The annual magazine of the Women’s Christian College in Chennai records that in 1966, Lesslie Newbigin, a bishop of the Church of South India in Madras, delivered an address on the role of Christian education in a secular democracy.Footnote88 The occasion was the college’s golden jubilee and Newbigin’s talk centred on the then-emergent tension between claims to ‘merit’ as the primary basis for access to higher education, and the rights-claims made by members of Dalit and Backward Class communities, who remain heavily under-represented in Indian universities. Elites in India have long held up ‘merit’ as a counterargument to caste-based policies of positive discrimination in public institutions.Footnote89 The claim to ‘merit’, scholars have noted, is rooted in the discursive disembedding of upper-caste selfhood from histories of capital accumulation and social privilege.Footnote90

Newbigin’s talk at the WCC grappled with these questions, albeit through the lens of Christian ethics. He argued that, on the one hand, it was imperative for the state to ensure that every citizen—‘whatever his income bracket and whatever his IQ’—had access to higher education.Footnote91 On the other, he also contended that the demand for ‘excellence’ was neither unreasonable nor entirely incompatible with the demand for equality. The fostering of individual talent, he specified, was a fundamentally Christian social duty: the materialisation in the temporal world of divine love not only for a common humanity, but for each individual soul.Footnote92 Newbigin then went on to warn, however, that such talents would necessarily be those of a small minority. Christian education, he argued, might play an important role here: recasting merit as a god-given gift meant for the use of society as a whole. The meritorious few, Newbigin suggested, might thus be taught to see themselves not as entitled to the labours of others on account of their gifts, but instead as bearing a greater burden of social service towards the society that nurtured their talents.Footnote93

In this discourse, ‘merit’ came to be imagined among middle-class Christians as a site of moral capacity as much as intellectual ability. Virtues and talents, to use the eighteenth century terminology, which drew in equal measure on Protestant theology as on Enlightenment ideals of self-improvement, are regarded as mutually constitutive in this discourse.Footnote94 In the scholarship on merit in South Asia, the typical focus has been on institutions of technical education that have played a significant role in materialising national claims to scientific modernity and development. However, ‘merit’ has also allowed Indian elites access to spaces of international technocracy as an intellectual class. Footnote95 Seeking the international tends to be framed in this discourse as anti-communal, rooted purely in individual capacity. As the discourse of Protestant individualism and internationalism from the WCC show, however, meritorious claims to membership in an international community—whether of technical elites or of Christian humanitarians—reinscribes communalism outside its familiar geographies of regional fixity rather than transcending it.

This re-inscription undergirds the intersections of caste, class, gender and coloniality in the making of Indian modernity and is particularly clear in the role that WCC’s alumnae played as missionaries. Issues of The Sunflower published in the years after Indian Independence and the founding of the Church of South India (CSI) indicate that WCC’s students and alumnae travelled to take up teaching roles in New Guinea and Ethiopia as missionaries of the CSI.Footnote96 In an essay on her experiences in Ethiopia in the 1950s, Elizabeth Jacob writes of her experience teaching proper nutrition and cooking skills to Black mothers. An extension of the urban social work that the college’s students performed during their education, this missionary labour reinscribes the educated Indian woman as a full member of a Christian ecumene, taking her knowledge of proper domesticity elsewhere—to places imagined less modern. Transcending community for a Christian internationalist project of social service is here very much a practice of distinction, accomplished through the intimate and gendered labour of domestic reform.

Acknowledgements

This article has been a long labour of love, and I owe thanks (among others) to Stephen Legg and Charu Gupta for their editorial work on this special issue; to Sumathi Ramaswamy and the North Carolina Consortium for South Asian Studies; to the attendees of the South Asian Studies seminar at Oxford; to Megan Robb, Afsar Mohammed and other attendees of a Religious Studies Symposium at the University of Pennsylvania; to the members of the Desirable Writing group; and to V. Geetha and Anusha Hariharan for comments at various stages. Any errors are of course all mine.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1. Anonymous, ‘Education and Politics’, The Sunflower (1941): 16–19.

2. Ibid.

3. Cemil Aydin, The Politics of Anti-Westernism in Asia: Visions of World Order in Pan-Islamic and Pan-Asian Thought (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007); Seema Alavi, Muslim Cosmopolitanism in the Age of Empire (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015); Manu Goswami, ‘Imaginary Futures and Colonial Internationalisms’, The American Historical Review 117, no. 5 (2000): 1461–85.

4. Mrinalini Sinha, ‘Mapping the Imperial Social Formation: A Modest Proposal for Feminist History’, Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 25, no. 4 (2000): 1077–82.

5. Gyanendra Pandey, The Construction of Communalism in Colonial North India (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 3rd ed., 2012); Ali Usman Qasmi and Megan Eaton Robb, ‘Introduction’, in Muslims against the Muslim League, ed. Ali Usman Qasmi and Megan Eaton Robb (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017): 1–34.

6. Nico Slate, Coloured Cosmopolitanism: The Shared Struggle for Freedom in the United States and India (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012); Toral Jatin Gajarawala, ‘Mother Russia, Dalit Internationalism and the Geography of Postcolonial Citation’, Interventions 22, no. 3 (2020): 329–45.

7. Chandra Mallampalli, Christians and Public Life in Colonial South India: Contending with Marginality (London: Routledge, 2004); Eliza F. Kent, Converting Women: Gender and Protestant Christianity in Colonial South India (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004).

8. Mallampalli, Christians and Public Life.

9. Ibid.

10. Rupa Viswanath, The Pariah Problem: Caste, Religion, and the Social in Modern India (New York: Columbia University Press, 2014); Kent, Converting Women.

11. Pandey, Construction of Communalism.

12. Mallampalli, Christians and Public Life; Anonymous, ‘A Summary of Dr. John Matthai’s Speech on Responsible Government’, The Sunflower, 5–7; see also, Margaret Hunt, ‘Death of Miss Coon, the War, the Nationalist Struggle, Friendships (1938–1939)’, in Diary, Vol. 7 (1922), British Library, MSS EUR F 241 / 7.

13. Mallampalli, Christians and Public Life.

14. Pandey, Construction of Communalism.

15. Kent, Converting Women.

16. Sinha, ‘Mapping the Imperial Social Formation’.

17. Mrinalini Sinha, ‘Suffragism and Internationalism: The Enfranchisement of British and Indian Women under an Imperial State’, The Indian Economic & Social History Review 36, no. 4 (1999): 461–84; Elisabeth Armstrong, ‘Before Bandung: The Anti-Imperialist Women’s Movement in Asia and the Women’s International Democratic Federation’, Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 41, no. 2 (2016): 305–31; Sumita Mukherjee, ‘The All-Asian Women’s Conference 1931: Indian Women and Their Leadership of a Pan-Asian Feminist Organization’, Women’s History Review 26, no. 3 (2017): 363–81.

18. Pandey, Construction of Communalism.

19. Ibid.

20. Mallampalli, Christians and Public Life.

21. Ibid.; Viswanath, Pariah Problem; Kent, Converting Women; Stephen Legg, ‘Imperial Internationalism: The Round Table Conference and the Making of India in London, 1930–1932’, Humanity: An International Journal of Human Rights, Humanitarianism, and Development 11, no. 1 (2020): 32–53.

22. Stephen Legg, Round Table Conference Geographies: Constituting Colonial India in Interwar London (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2023).

23. For Ambedkar’s comments, see ‘Proceedings of Federal Structure Committee and Minorities Committee’, Indian Round Table Conference (Second Session), September 7, 1931–December 1, 1931 (London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1932): 563–64; for Pannir Selvam’s comments, see ibid., 565–66.

24. Ibid., 583–85.

25. V.S. Azariah, ‘Bishops and Politics’, The Madras Guardian, 14, no. 2 (1936): 17; V.S. Azariah, ‘The Caste Movement in South India’, International Review of Missions, 21, no. 84 (1932): 457–67.

26. Editors, ‘Notes of the Month’, Madras Christian College Magazine (1919).

27. Anonymous, ‘Dr. John Matthai’s Speech’.

28. Eddy Asirvatham, ‘The Evolution of My Social Thinking’, ed. The Christian Institute for the Study of Religion and Society, Bangalore (Madras: Christian Literature Society, 1970).

29. Ibid.

30. John Dharma Theertha, ‘Christ’s Contribution to Free India’, ed. Manganam Christava Ashram (Kottayam: Daily News Press, 1951).

31. A Group in Delhi, ‘Students and Public Questions’, Student Movement Review (1923).

32. Ibid. That this ideal was shared with Gandhi is evident from the scholarship that addresses Gandhi’s affinities with Christian thought. The point of divergence, however, centrally focused on the communal question, and Gandhi’s use of civil disobedience as a method: Leila Danielson, ‘In My Extremity I Turned to Gandhi’, Church History 72, no. 2 (2003): 361–88.

33. Harald Fischer-Tiné, The YMCA in Late Colonial India: Modernization, Philanthropy and American Soft Power in South Asia (London: Bloomsbury, 2022).

34. India Commission on Christian Higher Education, ‘Report of the Commission on Christian Higher Education in India: An Inquiry into the Place of the Christian College in Modern India’, in Christian Higher Education in India (London: Oxford University Press [and] H. Milford, 1931).

35. A Group in Delhi, ‘Students and Public Questions’.

36. Ibid.; Editors, ‘A Brief Statement about the World’s Student Christian Federation’, Student Movement Review 5, no. 1 (1923): 10–13.

37. Bernard Bate, ‘“To Persuade Them into Speech and Action”: Oratory and the Tamil Political, Madras, 1905–1919’, Comparative Studies in Society and History 55, no. 1 (2013): 142–56; Bhavani Raman, Document Raj: Writing and Scribes in Early Colonial South India (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2012).

38. Kent, Converting Women; Rupa Viswanath, Pariah Problem; Gauri Viswanathan, Outside the Fold: Conversion, Modernity, and Belief (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1998).

39. Kent, Converting Women.

40. Deborah Anna Logan, The Indian Ladies’ Magazine, 1901–1938: From Raj to Swaraj (Bethlehem, PA: Lehigh University Press, 2017).

41. Meera Kosambi, ‘Multiple Contestations: Pandita Ramabai’s Educational and Missionary Activities in Late Nineteenth-Century India and Abroad’, Women’s History Review 7, no. 2 (1998): 193–208; Meera Kosambi, ‘Returning the American Gaze: Pandita Ramabai’s “The Peoples of the United States, 1889”’, Meridians 2, no. 2 (2002): 188–212.

42. Viswanathan, Outside the Fold.

43. Barbara N. Ramusack ‘Cultural Missionaries, Maternal Imperialists, Feminist Allies: British Women Activists in India, 1865–1945’, Women’s Studies International Forum 13, no. 4 (1990): 309–21; Jane Haggis, ‘Ironies of Emancipation: Changing Configurations of “Women’s Work” in the “Mission of Sisterhood” to Indian Women’, Feminist Review 65, no. 1 (2000): 108–26.

44. Kent, Converting Women.

45. Annal Satthianadhan and Annammal Clarke, Nalla Tāy [The Good Mother] (Madras: Christian Literature Society for India, 1921).

46. Mytheli Sreenivas, Wives, Widows, and Concubines: The Conjugal Family Ideal in Colonial India (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2008).

47. Eleanor McDougall, Lamps in the Wind: South Indian College Women and Their Problems (London: Edinburgh House Press, 1940).

48. Mary Hancock, ‘Home Science and the Nationalization of Domesticity in Colonial India’, Modern Asian Studies 35, no. 4 (2001): 871–903.

49. Eleanor McDougall, ‘Women’s Christian College, Madras 1915–1925’, ed. Women’s Christian College (Chennai [Madras]: Madras Diocesan Press, 1925).

50. Anonymous, ‘For the College Girls of the Far East’, Woman’s Journal 5, no. 29 (1920): 801; W. Peabody Henry, ‘Building Colleges for the Women of Asia’, Woman’s Work 36, no. 12 (1921): 287–88; W. Peabody Henry, ‘Story of the College Campaign’, Woman’s Work 38, no. 4 (1923): 91–93.

51. McDougall, ‘Women’s Christian College’.

52. Henry, ‘Story of the College Campaign’.

53. Editors, ‘Editorial’, The Sunflower (1953): 5.

54. Anonymous, ‘College Calendar’, The Sunflower (1935): 3. College calendars in the 1930s regularly mention Student Christian Movement meetings, camps and fundraising functions in the college.

55. Anonymous, ‘The Quadriennial Conference at Rangoon’, The Sunflower (1938): 20–22.

56. Ibid.

57. For example, Anonymous, “Echoes of the Calcutta Conference”, The Sunflower (1924): 7–12. The diaries of Margaret Hunt, who taught at the WCC in the 1930s, also indicate the growing preference among Indian Christians for interdenominational worship: see Margaret Hunt, ‘Vacations, the International Fellowship, Social Life’, in Diary, Vol. 5, Collection Area: India Office Records and Private Papers, 1936–37, British Library Mss Eur F241/5.

58. Editors, ‘Activities of Our Old Students’, The Sunflower (1935): 31–36.

59. Shannon Jackson, Lines of Activity: Performance, Historiography, Hull-House Domesticity (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2000).

60. For example, see ‘Reports of Societies: Social Work’, The Sunflower (1924): 19–22. In addition, the college calendar throughout the 1930s mentions rural uplift camps—trips on which students would conduct social service with rural communities.

61. Jackson, Lines of Activity.

62. Viswanath, Pariah Problem.

63. Viswanathan, Outside the Fold.

64. Kent, Converting Women.

65. Anna Satthianadhan, A Brief Account of Zenana Work in Madras (London: Seely & Co., 1878).

66. Ibid.

67. Ibid.

68. S.T. Benjamin, ‘Student Christian Movement 1936 October–1937 September’, The Sunflower (1937): 48–49.

69. Editors, ‘The Nature of Christian Social Action’, The Madras Guardian (1936).

70. Mallampalli, Christians and Public Life.

71. Editors, ‘A Brief Statement’.

72. Benjamin, ‘Student Christian Movement’.

73. This argument is also expressed in S.K. Chatterji, Students and India of To-Day (Calcutta: C.M. Bradley, Publications and Publicity Secretary, YWCA, 192–?).

74. For instance, see K. Adam, ‘Report of the Week of Witness for 1940’, Dornakal Diocesan Magazine 18, no. 7 (1940): 7–8.

75. Azariah, ‘Caste Movement’.

76. B.R., ‘Some ‘Findings’ from the Group Discussions at the SCM Camp, August 20–22nd, Submitted to and Accepted by the “Camp” as a Whole’, The Sunflower (1937): 49–51.

77. Eleanor Rivett, Memory Plays a Tune: Being Recollections of India, 1907–1947 (Chennai [Madras]: Women’s Christian College, 1947).

78. McDougall, Lamps in the Wind.

79. Jane Moses, ‘Dharapuram’, The Sunflower (1935): 33.

80. Ajay Skaria, ‘Relinquishing Republican Democracy: Gandhi’s Ramarajya’, Postcolonial Studies 14, no. 2 (2011): 203–229.

81. Anonymous. ‘News’, The Sunflower (1943): 2–3.

82. Benjamin Siegel, ‘“Self-Help which Ennobles a Nation”: Development, Citizenship, and the Obligations of Eating in India’s Austerity Years’, Modern Asian Studies 50, no. 3 (2016): 975–1018.

83. Rivett, Memory Plays a Tune.

84. Ibid.

85. Anna Zachariah, Letter to the British Board of Women’s Christian College, January 29, 1968, Women’s Christian College British Board Papers, British Library, MSS Eur F220/150, 1.

86. McDougall, Lamps in the Wind.

87. Women’s Christian College. A Call from Madras, ed. Women’s Christian College (Madras: Madras Diocesan Press, 1958).

88. Lesslie Newbigin, ‘Jubilee Address: Delivered by the Right Reverend Lesslie Newbigin, Bishop in Madras’, The Sunflower: Golden Jubilee Issue (1966): 27–30.

89. See, for instance, Nivedita Menon and Aditya Nigam, Power and Contestation: India since 1989 (London: Zed Books, 2013).

90. Satish Deshpande, ‘Exclusive Inequalities: Merit, Caste and Discrimination in Indian Higher Education Today’, Economic & Political Weekly 41, no. 24 (2006): 2438–44.

91. Newbigin, ‘Jubilee Address’, 27.

92. The uniqueness of Christianity’s emphasis on the individual was arguably a central tenet of Protestant mission work in India, as I will elaborate below. For other explorations of this idea, see Rosalind O’Hanlon, Caste, Conflict and Ideology: Mahatma Jotirao Phule and Low Caste Protest in Nineteenth-Century Western India (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985).

93. Ibid., 28.

94. See, for instance, John Carson, The Measure of Merit: Talents, Intelligence, and Inequality in the French and American Republics, 1750–1940 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2007).

95. Ajantha Subramanian, The Caste of Merit: Engineering Education in India (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2019).

96. Elizabeth Jacob, ‘Ethiopia through the Eyes of an Alumna’, The Sunflower (1953): 9–11.