ABSTRACT

The paper examines the responses of family directors to board reforms. The notion of reflexivity is used to account for family directors’ concerns and subjectivities shaping board practices. To empirically ground the reflexive deliberations of family directors, the paper draws on qualitative data gathered from 25 in-depth semi-structured interviews in combination with archive material and an extensive documentary survey. The paper has demonstrated how family directors deploy the resistance strategies such as organisation of coordinated lobbies, counter-narratives and codification of internal rules to keep the change minimal. The paper contributes to the debate on distorted/symbolic compliance, seen as resistance in this paper, often being reduced to institutional embeddedness or overgeneralised notion of interests/conflicts in family publicly listed companies. The paper also makes a case of a new theoretical dimension – reflexivity – which enables an understanding not only of family directors’ economic but also non-economic concerns relating to board reforms.

1. Introduction

Family-controlled publicly listed companies (PLCs), especially in Asian emerging economies, have undergone rapid institutional and governance reforms following the 1998 Asian financial crisis. Globally, family firms have become important economic players over the last two decades (Aguilera & Crespí-Cladera, Citation2016). However, the recurring corporate governance scandals, loan scams and corruptions involving family companies have brought their board and corporate governance practices into the limelight (Hassan, Citation2019; Uddin et al., Citation2017). The scandals, along with internationalisation, competition for global capital and funding from donor agencies, have provided justifications for wide-ranging governance reforms. Some of these reforms are focused on curbing family power over the corporate board through the adoption of Anglo-American best practices such as independent boards and committees, professional oversight, transparency and accountability to shareholders (Lien et al., Citation2016). The intended reforms targeting corporate boards are expected to generate tension and resistance from family directors, mainly because of unique governance structures in family PLCs. Yet critical scrutiny of family directors’ responses to reforms is rarely seen on the agenda of research and policy debates (Ahmed & Uddin, Citation2018; Nakpodia et al., Citation2021).

Rapid reforms and recurring scandals led, predictably, to research and policy debates on the level of compliance with reforms (Ahmed & Uddin, Citation2018; Kabbach de Castro et al., Citation2017). Prior literature documents regulatory demands met with superficial compliance (Tremblay & Gendron, Citation2011; Yildirim-Öktem & Üsdiken, Citation2010), cynical adoption of structures decoupled from practice (Yoshikawa et al., Citation2007) or overstatement of compliance (Sobhan, Citation2016). Nevertheless, how powerful actors such as family directors respond (with superficial compliance or resistance) to reforms, especially in the family governance setting, is poorly understood. Thus, we believe, the actions/responses of these powerful family directors to board reforms deserve theoretical and empirical attention.

Much of the research tends to study actions and behaviour of family PLCs based on economic concerns motivated by agency theory (Yusuf et al., Citation2018). Some studies, however, consider non-economic concerns, drawing on theories such as socio-emotional wealth and familiness (Siebels & zu Knyphausen-Aufseß, Citation2012). Such efforts, albeit important, rarely seem to give space to the diverse range of family directors’ concerns (whether economic or non-economic) that shape their actions/resistance in situated settings. Given this, the lack of compliance in family companies is seen to be linked with the divergence of interests (economic and non-economic) between family and non-family shareholders and the institutional contexts. Many of these non-compliance issues are linked with weak democratic and capital market institutions in emerging economies (Ahmed & Uddin, Citation2018; Soleimanof et al., Citation2018). Existing research barely examines the actions of family directors underlying such non-compliance or superficial compliance as an active form of resistance to reforms. Particularly, the ways in which non-economic interests shape actions and resistance are rarely studied. Thus, the paper poses the following questions. How do family directors respond to board reforms? What concerns/interests (economic and non-economic) of directors shape their responses to board reforms?

Our theoretical position builds upon the writings of Archer (Citation2003) on reflexive deliberations. To Archer, the actions of an individual are derived from his/her reflexive deliberations about the personal concerns or interests (both economic and non-economic). Through such deliberations, actors consider on the range of concerns, prioritise one type of concern over another and decide actions. Seen this way, resistance entails a set of actions. Tracing these actions through the reflexive deliberations of directors not only allows us to bring to the fore different types of concerns but, more importantly, shows how these concerns shape their resistance to reforms. The paper thus deepens the current understanding of superficial compliance or non-compliance.

Our empirical illustrations come from family PLCs located in Bangladesh, an emerging economy. The overwhelming dominance of a minority but powerful group of shareholders (i.e. family directors) on boards in Bangladeshi family PLCs is well noted in the literature (Ahmed & Uddin, Citation2018; Uddin & Choudhury, Citation2008). The ownership structure, along with recurring scandals and rapid reforms mainly under the pressure of donor agencies such as the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF), makes family PLCs in Bangladesh an interesting empirical setting.

The paper makes two contributions to the family governance literature. First, we extend prior research on non-compliance/symbolic compliance. We have demonstrated how family directors deploy the resistance strategies such as organisation of coordinated lobbies, counter-narratives and codification of internal rules to maintain their power and keep the change minimal. Second, the paper makes a case for a new theoretical dimension – reflexivity – which enables insight into directors’ deeper concerns/life projects. The paper shows family directors translate regulatory changes in light of their personal concerns, ideologies and subjectivities derived from their life projects. This complements the existing set of theoretical frameworks within family business literature that aim to understand diverse range of concerns of family directors.

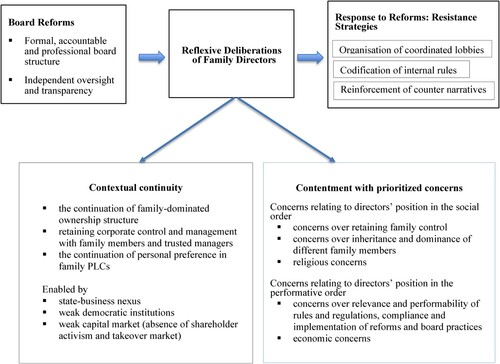

This paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews existing literature on family governance and board reform, Section 3 explains theoretical perspectives on agency and Section 4 discusses the research design. Section 5 discusses the institutional context of reform. Section 6, designed on the basis of , discusses changes to board practices (6.1), responses to change (6.2) and reflexive deliberations to explain the family directors’ actions (6.3). Section 7 summarises the contributions and limitations of the paper.

2. Family governance, board reforms and family directors

Governance in family-controlled PLCs is usually characterised as “principal–principal” conflicts (Young et al., Citation2008). From this perspective, the economic interests of a minority group of principals (i.e. family shareholders) are likely to be in perpetual conflict with the interests of other groups of principals (i.e. dispersed shareholders). Family owners’ inclination to inherited ownership and socio-emotional wealth attachment tend to expose the corporate boards to intra-family conflict, managerial entrenchment, parental altruism and other complexities (Gómez-Mejía et al., Citation2011; Lubatkin et al., Citation2005). Moreover, complex governance structures linked to business group affiliation often make board monitoring complicated (Yildirim-Öktem & Üsdiken, Citation2010).

Studies have generally questioned the suitability of board reforms modelled on Anglo-American tradition for companies in emerging economies beset with under-developed institutions and distinct priorities and histories (Mohamad-Yusof et al., Citation2018; Yildirim-Öktem & Üsdiken, Citation2010; Yusuf et al., Citation2018). This is further exacerbated by the fact these family companies rely on traditional control-based family governance structures (Ahmed & Uddin, Citation2018). For instance, family owners/directors often occupy multiple positions, both within the company (ownership, management and governance) and beyond (family, social, economic and political institutions) (Uddin et al., Citation2016).

It is already well established in the literature that the efforts to replace traditional control-based family governance with distinctively Anglo-American practices – independent boards, attention to shareholder value and enhanced transparency – often inflict a divergent process of change in practice (Yildirim-Öktem & Üsdiken, Citation2010). For example, Japanese firms adopted features from the Anglo-American governance model selectively (Yoshikawa et al., Citation2007). While researchers have made a compelling case that reforms have divergent processes and outcomes (Yildirim-Öktem & Üsdiken, Citation2010; Yoshikawa et al., Citation2007), far less research explicitly examines the deliberations of the powerful family directors in this process. Previous studies have argued that intended reforms make the family-dominated board a battleground for materialisation of multiple, often divergent concerns/interests and open spaces for family directors to play a significant role in the implementation of board reforms within the companies. Yet existing literature pays relatively scant attention either theoretically or empirically to concerns/interests and actions of family directors in the implementation of board reforms and resulting practices.

To date, the existing literature on family boards has mainly focused on firm-level behaviours and actions. A range of theories are drawn upon, notably socio-emotional wealth, familiness, stewardship theory, social capital theory, resource-based view and behavioural agency theory among others (Gómez-Mejía et al., Citation2011; Siebels & zu Knyphausen-Aufseß, Citation2012). These theories enable researchers to shed light on various incentives for actors’ behaviour and their impact on a range of measurable governance outcomes including earnings management, firm performance, disclosure quality and so on (Hsu et al., Citation2021; Martin et al., Citation2014). However, several studies have called for greater theoretical diversity and qualitative methodologies to explore the heterogeneity of family companies and their corporate governance, including board practices, so as to better explain the divergence in the behaviour and actions of actors (Aguilera & Crespí-Cladera, Citation2016; Chua et al., Citation2012).

Similarly, a growing number of studies have called for closer scrutiny of interests/concerns, behavioural processes and actions of key actors in corporate governance research from sociological perspectives (Ahmed & Uddin, Citation2018; Federo et al., Citation2020; Siebels & zu Knyphausen-Aufseß, Citation2012). We believe that focus on the variety and the origin of family directors’ concerns is critical to shed light on how those concerns are negotiated and fed into deliberations (resistance) individually and collectively in a situated setting. It should enable us to explain why the same regulatory pressure works in one context but appears to meet with resistance in another.

Drawing on the above literature, we argue that reforms aim at institutionalising certain structures and norms that are not necessarily linked to the ways in which key actors in the field think and act. The concerns of key actors as the link between the imposed reforms and the responsive actions demand further theorisation. Without denying the benefits of the theories used in family business governance, we find Archer’s (Citation2003) notion of reflexive deliberation – as a theoretical framework – to be a very pertinent way to understand the deeper concerns/life projects, behavioural processes and actions of the board members. The next section elaborates further our proposed theoretical framework.

3. Theoretical framework: reflexive deliberations

Considerations of reflexivity of “agent” (which also denotes here a person/actor) inherently take us away from the notion of “economic agent” derived from the agency theory (Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976). In contrast, Archer provides a nauanced view of agents (actors or similary positioned individuals). She argues, these individuals have multiple and inescapable “concerns” about the natural order (such as food), the performative order (such as job or promotion) and the social order (such as family relations or belongingness). They reflexively deliberate and decide actions in light of their prioritised concerns and the structural contexts they confront. For her, reflexivity is as an emergent personal property resulting from the interplay of “concerns” and “contexts”.

In our case, family directors are reflexive agents/actors who occupy a position of directorship on the board and are connected by family relation. This nuanced view of “agency” allows us to comprehend that regulatory pressures may lead to diverse action(s) depending on subjective deliberations (explaining regulatory pressures in light of prioritised concerns and subjectivities) of actors. Thus, understanding reflexivity of family directors might give us clues to “how” and “why” they respond to and resist reforms in one way rather than another.

Archer (Citation2003, p. 96) defines reflexive deliberation as an inner dialogue, based on listening and responding inwardly to the inner “I” about the structural contexts. In their reflexive deliberation, actors engage in debate about their concerns, prioritise their ultimate “concern” and define their personal life project (defined as the constellation of multiple and prioritised concerns providing contentment to actors) in light of their structural contexts and related influences and decide the courses of actions that serve their personal life projects. If we take Archer’s conceptions of “agency” with diverse reflexive deliberations, family directors – although “similarly positioned individuals” – have multiple concerns relating to their position in the social order (family, religion or political connection, etc.) and the performative order (board/corporate positions). While acknowledging that structures (collections of related institutions, positions and ideas) possess the power to constrain or enable actors to take similar actions, Archer in her theory of agency ascribes a central role to reflexive deliberation as actors’ subjective power that mediates the impact of structures (Caetano, Citation2015b), driving them to take diverse actions.

To put it simply, different individuals occupying certain positions in a given structural domain, and thus confronting the same contexts, do not necessarily act in the same way. Applying this to family PLCs means that family board members in the same role may interact with regulatory constraint(s) or build on structural enablement(s) quite differently. For example, one family director with a performative focus (such as access to bank loans or global capital) may embrace a democratic and professional board, whereas another director’s prioritisation of concerns over religious values (such as the prohibition of interest in Islam) may restrict democratic decision-making by the board. Reforms often make subject positions conflicting, such as directors being viewed as “shareholders’ steward” versus as “owner–manager” and condition the possibility for emergence of alternative meaning and acts.

To understand the reflexive deliberations of family directors (causes of specific courses of actions), Archer (Citation2003) explores two elements: “contextual continuity” and “contentment with prioritised concerns”, as depicted in .

Figure 1. Reflexive deliberations. Source: Developed by authors drawing inspiration from Archer (Citation2003).

According to Archer (Citation2003), an actor’s reflexive deliberations originate from a dialectical interplay in which a particular aspect of context, namely continuity or discontinuity or unsettlement, “proposes”, but the nature of personal concerns then “disposes”. Theoretically, this means a person with contextual continuity will have dispositions for reproducing it further if their prioritised concerns also demand continuity. For example, if a person expects that a given project could encounter constraint, they will try to adjust it or refrain from pursuing it. During execution, if a project is constrained, people will try their best to discover ways around the constraints.

Archer points out the strong roles existing structural advantage/disadvantage might play for a person deciding whether they would like to maintain the status quo (contextual continuity) or unsettle the continuity (discontinuity) and be content with prioritised concerns. For example, persons with contextual continuity (with structural advantage) usually tend to prioritise “familiar and similar” ones in dovetailing their multiple concerns. Since their life projects (defined as the constellation of concerns or deeper concerns) are forged into a particular contextual setting, their reflexive deliberations about changing situations are also carried out in light of those prioritised concerns. This means a person with a different life project would portray different deliberations about the same situation.

Theoretically, this means that the same regulatory change may be constituted and implemented quite differently, depending on the dialectical interplay of context and concerns of actors/individuals (in this case family directors). We argue that board reforms entail changes to contexts that directors confront involuntarily. Conceptualising their reflexivity allows us to provide an explanation of their actions, which ultimately shape how they respond to corporate board reforms and practices.

4. Research design

We studied the boards of six public limited companiesFootnote1 listed on the Dhaka Stock Exchange (DSE), Bangladesh. They have emerged from family business groups, a common trend in Bangladesh (Nahid et al., Citation2019). As per the direct holdingsFootnote2 reported in annual reports, the founder families hold an average of 22% of shares in the PLCs studied. In Bangladesh, sponsors who are from the founder families hold 43% of the market, and 38% is held by the public at large (World Bank, Citation2009, p. 2).

Qualitative data was gathered from 25 in-depth semi-structured interviews in combination with archive material and an extensive documentary survey. The interviews comprised five with regulators, nine with family directors (including a life historyFootnote3 interview), six with independent directors (non-family) and five with senior management (non-family, including two group interviews). All interviewees, except the regulators, had a role on the board of a company drawn from six PLCs. The interviewee profile is presented in .

Table 1. Interviewee profile.

Four interview guides were used to interview family directors, independent (non-family) directors, managers and regulators (see Appendix). The interview guides contained semi-structured but open-ended questions. Interview guides were influenced by the positions of the interviewee. For instance, for family directors, interviews included broader questions adopting a biographical approachFootnote4 (Caetano, Citation2015b). The family directors were asked about their roles and responsibilities; family and professional relationships; their roles and interaction with family and non-family directors, managers, shareholders and regulators; ways of decision-making; how they implemented and experienced the regulatory changes and how the implementation of regulations influenced their role, interaction, decision-making and board practices. The aim was to understand the evolution of deeper concerns/interests related to board and family governance in a specific time and context. We were particularly interested in the life stories of founder directors where they would reflect on their personal and family life, role in the family business and governance and how these changed over time. After several attempts, the life history interview with one founder chairman of a business group with several PLCs listed on the DSE was successfully undertaken.

The life history interview with one founder chairman of a business group was much longer and was conducted over a few days. Archive material (e.g. interviews, talk shows and news coverage in the electronic and print media about this founder chairman and other family directors) and documents formulated for different purposes were consulted (Mutch, Citation2007). Archer (Citation2003) also warns about exclusive reliance on the words of interviewees. Before the family directors were interviewed, individuals having some social and professional ties with these actors were interviewedFootnote5 to complement researchers’ understanding about their life projects and to incorporate some degree of data triangulation in research design. Questions were slightly different for independent (non-family) directors, managers and regulators (see Appendix for details). In general, the interview questions were geared to understand responses to reforms, respondents’ experiences and board practices.

We obtained consent to record two interviews using a digital voice recorder. Extensive handwritten notes were taken at other interviews. One research assistant accompanied the first author to take notes during the interviews. Interviews were conducted in Bangla, the local language. The first author transcribed the recorded interviews in Bangla. Both transcribed interviews and researchers’ notes were translated into English. These translated transcripts were sent to interviewees for comments (all interviewees are proficient in reading English text). Nevertheless, interviewees did not make any substantial changes. We revisited the transcripts to address any factual inaccuracies complemented by other sources of evidence such as annual reports, rules and regulations.

The documents examined included annual reports; company charters and articles of association; prospectuses; agenda papers, minutes and other board reports; internal codes of conduct and policy documents; terms of reference and job descriptions of directors and managers; regulatory notifications; policy documents and other reports published in newspapers and electronic media / company websites / websites of regulators, stock exchanges and development partners. In exploring the dataset, we elicited interviewees’ individual career trajectories and experiences and tracked the resources and interests associated with the position(s) directors held, while paying particular attention to their education, family background, career turning points, decisions and other events relating to board practices.

This study adopted latent thematic analysis to look for underlying meaning rather than the surface/semantic content of the data (Braun & Clarke, Citation2013). Themes were developed based on repeated reading (and interpretation) of interview transcripts. In each reading, “significant points” were noted in the left column while a new column was added clarifying, connecting and (re)interpreting the notes from previous reading. Sub-themes were developed based on these notes alongside the original text and reflections of the researcher. Sub-themes from other data sources (such as documents or archive materials) were linked with and cross-checked against the transcribed texts to ensure that the interpretation made sense in terms of the interview narratives. The first author carried out data familiarisation, coding of themes and indexing. The second author was consulted from time to time in that process. After coding, a Framework matrix – an indexing tool – was prepared in a spreadsheet to group together indexed textual data, dispersed across the transcripts, in charts of themes (Ritchie et al., Citation2013). For example, family directors’ interview quotes (textual data) are organised under chart of themes (sub-themes) such as decision-making control, board meetings, etc. This helped us to analyse the data further and develop key themes.

In this analysis, we constantly reworked our coding scheme/thematic analysis to capture nuances in the data and to theorise the process of resistance. Based on our discussion, we agreed to sum up “unaltered board practices” in two key themes: formal, accountable and “professional” board structure and independent oversight and transparency. Three more key themes were developed to articulate resistance in action: organisation of coordinated lobbies, internal codification of rules and reinforcement of counter-narratives. We then reflected on our theoretical framework () and sought to understand what concerns shape such resistance. We developed an analytical framework (see ), to articulate how reforms are deliberated by family directors considering their concerns. These concerns of family directors produced certain resistance strategies. This is important because it opens the black box of interaction and shows how changes in regulations set in motion strategic responses that only reproduce the traditional (family) governance structures.

The second researcher’s involvement was especially valuable at this, more interpretive, stage to increase sensitivity and openness to meanings within the data. To test the validity of the interpretation, the second researcher sampled a few transcripts for counter evidence. Multiple aspects of experiences and meanings relating to board reform were taken into account. Discussion and consensus about the pattern of reflexive deliberations were obtained between the researchers on a case-by-case basis. We examined interviewees’ personal concerns/interests in the context in which they were situated to understand why one particular interest was prioritised over others. We identified their dispositions for the reproduction or change of “board practices”. We then traced back these dispositions to their prioritised concerns/interests. This involved exploring the theory-driven themes from the data: “contextual continuity” and “contentment with prioritised concerns”. For example, interviewees’ comment about their rigidity in pursuing a career outside the family business would be coded under the theoretical theme “contextual continuity”. CEOs’ reliance on father or trusted manager is indicative of their “prioritisation of known/similar ones”, something which we viewed as their “contentment with concerns in the social order”. In contrast, someone’s reliance on formal decision-making is indicative of his “contentment with concerns in the performative order”.

The following sections are presented inspired by to address the research questions set out earlier of how family directors respond to board reforms and to provide nuanced explanations of their resistance to reforms.

5. The institutional context of reform and family board

Before elaborating on the board reforms and practices, it is important for us to take stock of the institutional conditions of reforms and family boards. This will help us to contextualise the family directors’ concerns/interests in maintaining the status quo. In other words, it will help us to explore family directors’ interests in “contextual continuity” and “contentment with prioritised concerns”.

The six PLCs studied have emerged from family business groups, a common trend in Bangladesh (Nahid et al., Citation2019). As in many emerging economies, controlling families implement a pyramidal ownership structure to secure their control and dominance over boards in the listed companies. Families often have ownership in several de facto holding companies (usually private limited) that hold the controlling stake in affiliated companies (Nahid et al., Citation2019). Families with a non-controlling stake (i.e. less than 50% share ownership) secure control over the companies by reserving the board and management positions (Sobhan & Werner, Citation2003).

The dominance of family owners and firms in the stock market is partly linked with the privatisation programs of 1980s and 1990s in Bangladesh (Uddin & Hopper, Citation2003). However, raising capital through the stock market was not a very common approach, partly because of the owners’ reservations about dilution of control and the availability of bank loans (Uddin & Hopper, Citation2003). Until recently, institutional context is characterised by concentrated ownership, a heavy reliance on bank and public finance, reluctance to raise money from the stock market, almost non-existent shareholder activism, an inefficient judiciary and a non-existent takeover market (Uddin & Choudhury, Citation2008; World Bank, Citation2009).

Nevertheless, the capital markets in Bangladesh grew over the years. The Bangladesh Security Exchange Commission (BSEC), on behalf of the Ministry of Finance, regulates the business affairs of the capital market. The BSEC has the regulatory authority to seek more information and explanations for financial reporting items or abnormal share prices from PLCs. In case of non-compliance, the BSEC has the power to impose penalties. More importantly, the BSEC keeps a close eye on the daily affairs of the stock exchanges. This did not prevent the first stock market crash in 1996. Since 1990, the government embarked on state-led institutional reformsFootnote6 under pressure from its development partners, notably the World Bank, Asian Development Bank (ADB) and IMF (ADB, Citation2013, Citation2016; World Bank, Citation2009).

The legal and regulatory structure, particularly the Companies Act 1994, was viewed as less obtrusive and detailed with regard to the conduct of boards of directors and the protection of shareholders’ rights (World Bank, Citation2009). Recurring stock market scandals, loan scams and other corruptions involving politically influential directors of PLCs have resulted in multiple revisions of the code(s) and listing regulations over the last decade. The aim was to promote the accountability of directors by weakening the tight grip of families on PLCs.

The interview evidence suggests that, as founders, families have tended to form the initial boards and establish family control over corporate decision-making and resources. During the interviews, the founder of a business group confirmed that he reserved “director” positions for his family members and trusted individuals. He insisted, “That is why we are what we are today.” Thus, the alignment of interests made their governance relational, limiting the need for formal structures. The entrepreneurial life stories that the founders narrated during the interviews also encapsulate a strong message of family connection and commitment. In many PLCs, family members found themselves directly involved in day-to-day management. In a context in which general shareholders tended to remain totally ineffectual and apathetic (Sobhan & Werner, Citation2003), the direct involvement of families gave them absolute control, even enabling amendments to the memoranda or articles of association to be achieved with relative ease.

Directors were nominated informally depending on the will of the controlling family. The candidates nominated were elected by default at annual shareholders’ meetings. Boards comprised close family members (wife, son, daughter, brother, sister, father) of the founder. Independent directors were uncommon or non-existent. On boards where the directors had ultimate controlling power, their appointment, remuneration and performance evaluation mechanisms were opaque and informal. Informal practices also extended to the conduct of boards such as getting important official documents signed at the founder’s residence. The boundaries of “household” and “company” were blurred (Uddin & Choudhury, Citation2008). The founder held the main decision-making power, and major board decisions were usually made at the instigation of the family. Board meetings appeared to be no more than a legal formality for rubber-stamping decisions requiring formal approval. In short, corporate board practices were characterised by informal board mechanisms, powerful founders and a lack of independent oversight. All these are expected to change following corporate governance reforms.

6. Resistance and change in board practices

depicts three important elements of the analytical framework to address the research questions set out earlier: board reforms, resistance to reforms and reflexive deliberations of family directors to understand “how” and “why” family directors respond to and resist the reforms imposed on family PLCs. These are discussed below.

6.1. Reforms: unaltered board practices

This section presents the change efforts of corporate board reforms. Several key reformsFootnote7 were implemented in Bangladesh (BSEC, Citation2012; World Bank, Citation2009). This has brought in an idealised Anglo-American corporate governance framework with shareholder supremacy, transparency and accountability of board members and independent boards, perhaps in a bid to separate the “household” and the “company”, especially for family firms. Two major change efforts can be articulated: (a) a formal, accountable and “professional” board structure and (b) independence and transparency of board processes. These are discussed below.

6.1.1. Formal, accountable and “professional” board structure

The regulatory changes brought about by the recent corporate governance reforms have broadly redefined the roles and responsibilities of corporate board members in terms of intensifying the scrutiny of directors as protectors of shareholders’ interests. Significant emphasis has been placed on the professional attributes of directors such as relevant education and qualifications. Nevertheless, in practice, family relations seem to surpass all professional attributes. The family directors interviewed reported that directors are appointed on the basis of family and kinship ties. “Learned from father”, “disclosure of having experience in the industry” or “travelling around the world” are sufficient professional attributes for one to become a director.

Emphasis has also been placed on the formalities of corporate boards, such as downsizing, changing composition, formalisation of meetings, segregation of duties, legal documentation, reporting to regulators and new positions and specialised committees supporting the board (BSEC, Citation2012). The positions of the chairperson and the CEO were filled by different individuals in all the PLCs studied. However, to minimise what has been construed as the “costly intervention of outsiders”, the new positions to support board and committee operations (such as company secretary, chief financial officer and head of internal audit) were mostly staffed through internal restructuring. To some extent board meetings became formal. One company secretary in charge of arranging board meetings said: “Nowadays board meetings are becoming more structured as we have to report to the regulators on several matters, such as directors’ attendance, minutes and interim financial reports approved by the board.”

Meetings are still seen as burdensome. The CEOs interviewed complained about preparations for “what goes into the meeting” and the volume of paperwork around board meetings. An examination of the minutes of the board meetings indicates that the boardroom activities tend to be dominated by non-strategic and regulation-compliance-centric discussions.

6.1.2. Independent oversight and transparency

Specific regulatory changes have been proposed in the area of board independence especially limiting the board size to between 5 and 20 directors, with at least one-fifth being independent directors. This is to allow non-controlling shareholders’ concerns to be raised in the boardroom and reduce controlling owners’ opportunistic behaviour (BSEC, Citation2012). The definition of “independent director” resembles Anglo-American corporate governance models. Most PLCs have complied with the reforms by appointing “independent directors” fitting the definition set in the code. Despite the strong regulatory oversight of board independence, the task of establishing an active independent board is largely left to the company-specific initiatives of dominant family directors. As is evident from the fieldwork, those recruited as independent directors continue to be drawn from a closed network. The trend of appointing retired civil servants, military persons, regulators and senior bankers in this position and using them to get the best out of the regulators or as payback for previous favours is documented in prior studies and reports (Sobhan & Werner, Citation2003, p. 23; World Bank, Citation2009).

The independent directors interviewed clearly indicated that they had been invited to join boards by personal acquaintances and that they regarded it as an act of honour and friendship that is hard to resist: “I could not turn down the board’s invitation. It’s my school friend’s company.” None of them received written terms of reference defining their duties and authorities. Material incentives for serving on boards are limited to a generous meeting honorarium. Some of them were confused about whether or not they were indemnified from any civil or criminal proceedings arising out of their role. This is particularly related to bank loans, which require all directors to sign personal guarantee letters for loans. However, not all of them seemed to be very bothered. When asked about the challenges facing independent directors, one respondent’s answer was: “Frankly speaking, I have found nothing challenging. All I need to do is to attend the quarterly board meetings and sign some documents.”

The inability of independent directors to raise difficult questions in board meetings was revealed in many of our interviews. One independent director admitted, “Independent directors can never be the champions of shareholders’ interests at the board level. We don’t have any defined job responsibilities.” There is ambiguity regarding the responsibilities of “independent” directors as reflected in this respondent’s comment. Unlike the directors whose responsibilities are enumerated in the Companies Act, the responsibilities of “independent” directors are set by the board of directors.

Another talked about the inhibiting board culture: “The culture is different. Founders have a powerful position on the board. We can at best work in an advisory capacity. The financial reports and information presented in board meetings are controlled by them.” Similar views were expressed by all independent directors interviewed.

Transparency and accountability of board processes were one of the main aspects of the new code (BSEC, Citation2012). For example, the code requires the two top executives – CEO and CFO – to certify that they are not aware of any violation of the code by the board and this certification must be disclosed in the annual report. There is also a mandatory provision in the code for splitting the functions of the CEO and the chairperson of the board. The BSEC officials have argued that splitting is required for two reasons: to restrict absolute control over decision-making and to allow independent managerial evaluation to take place. However, in companies in which the chairperson and CEO are related through family ties, it is unlikely that these aims will be achieved. In practice, even after the functions have been split, the chairperson tends to have unfettered control over decision-making.

In summary, almost all rituals surrounding legally required board practices are found to exist, but the practice closely resembles that of the pre-reform era. The scope of board meetings, as before, is limited to approving quarterly financial reports, financing, dividends and other proceedings that require board approval by law. Holding statutory board meetings, keeping agendas and minutes, reporting director attendance and other similar formalities seem to exist as rituals to fulfil regulatory compliance. Family directors (e.g. wife, son, daughter, cliques and friends) sit on the boards. Board practices, in essence, consist of rubber-stamping decisions. Independent director positions tend to be occupied by friendly outsiders who have political, social or other ties with the founders. Even if they meet the “independence” criteria in legal terms, they have little decision-making role in the boardroom. The following section explains strategies adopted by family directors to keep board practices unchanged.

6.2. Response to reforms: resistance (avoidance) strategies

This section illustrates the resistance strategies of family directors as depicted in . We identify three strategies adopted by family directors to keep change minimal: organisation of coordinated lobbies, counter-narratives and maintenance of close family control. Each of these strategies is discussed in detail below.

6.2.1. Organisation of coordinated lobbies

A lobby group called the Bangladesh Association of Public Listed Companies (BAPLC), a de facto association of family directors, has been very active in challenging prospective changes to corporate governance regulations, which in its terms are “rigid regulatory requirements”. For instance, a top official of the BAPLC stated, “Independent directors are a “double-edged sword” and their inclusion should be left up to the founders.” The executive body of the BAPLC comprises high-profile members who have familial and political ties, not only to the ruling party but also to the opposition in parliament. They successfully delayed strict mandatory provisions for compliance when the first corporate governance guideline (hereafter code) was issued in 2006 on a “comply or explain” basis. According to one high official of the BSEC, “We had a plan to impose the provision of mandatory compliance earlier. However, it got delayed somehow. The stakeholders [the BAPLC] asked for some time before any such strict requirements were imposed.”

In 2012, six years later, the BSEC enacted and revised the corporate governance code as a hard law (BSEC, Citation2012). As a senior official of the BSEC confirmed during an interview:

The initial draft was revised more than three times based on the views of various stakeholders, particularly the BAPLC. The proportion of independent directors, board size, etc. were the areas where the stakeholders expressed their concerns, and the latest guideline was finalised taking into consideration their concerns and views.

6.3. Codification of internal rules

Maintaining close family control amid regulatory reforms is a considerable challenge for family directors. Family directors manage absolute control in PLCs through the board even when they have minority share ownership. As a common practice, the chairperson forms an executive committee (EC), including the CEO and a few other (not all) family directors. Interviews with CEOs, company secretaries and CFOs revealed that since strategic decisions are taken early in the EC meetings and/or in informal discussions, important discussions rarely take place in the presence of “outsider” board members. The comment of the following non-family CEO also portrays the informal nature of EC practice:

I regularly communicate with the chairman. He rarely visits office. We meet at his residence and finalise the decisions based on his guidance. Legal formalities for board meetings are also duly followed. Agenda papers and other documents are posted to independent directors ahead of the board meetings.

To maintain close family control and resist the board’s democratic processes, an internal “code of conduct” is often issued for directors, frequently in writing. Interestingly, such codes not only limit the role of “outsiders” (independent directors), but sometimes empower certain family members over others. They are highly confidential and often contain restrictive provisions on decision-making and control within the PLCs. One code reads as follows:

Interaction with employees: to ensure efficient management operations, avoid conflicting instructions from the board to management and avoid potential liability, employees should only take orders from the president of the board [a title given to the eldest son of the founder].

6.3.1. Reinforcement of counter-narratives

Under the banner of “accountability and transparency” narratives, regulatory actors have introduced the ideas of “shareholder wealth maximisation”, “board independence” and “professionalism”. Family directors encountering such narratives are necessarily incentivised to introduce ideas to counteract those whose hegemony might obstruct their life projects. Bracketing the imposed rules for boards as foreign, and therefore inapplicable, was a common narrative. Directors were resistant to the sweeping generalisation of family managers as non-professionals. Identifying independent directors as “laymen” or “outsiders” is also a common narrative weakening the legitimacy of the code. To quote one founder director:

These provisions apply in the Western society. Corporate governance, accountability, transparency, CSR, these are a passing fad for us. In the name of corporate governance, the regulator [BSEC] is imposing an additional regulatory burden.

All the family directors interviewed harshly criticised the independent directors’ role. They questioned why someone from outside should accept the onerous responsibilities of directorship. For some, the need for independence at the board level was “never felt”: one CEO talked about the tradition of informal control operated through regular meetings with trusted managers, long-term suppliers and dealers. Thus, relational ties were prioritised and conceived as “more effective” than formal board governance. For others, board independence was a “supply-side” problem such as lack of suitable candidates. Independent directors’ incompetence, lack of shareholders’ mandate and genuine incentives, and ambiguous authority and responsibility were common themes of criticism. On the grounds of preserving secrecy and operational effectiveness (for example, avoiding administrative burden and unnecessary delay in decision-making and cost–benefit considerations), insiders tended to justify the necessity to limit the role of independent directors. Some argued that an owner–manager is likely to work “more rapidly and effectively” than an executive hired from outside. Regarding secrecy, one founder director expressed his concern: “We have to be cautious. You can never know what information independent directors are taking out into the market. At worst, perhaps he or she is sitting on our competitor’s board.”

Company secretaries also tended to suggest that board meeting agendas and supporting documents are set out in such a way that sensitive information is never leaked to “outsiders”. This significantly increased the administrative burden.

It was also argued that distinct corporate culture and ambiguity surrounding rules and regulations made it difficult to implement some corporate governance principles in Bangladesh. One vice chairman (also BAPLC leader) gave the example of the norm of personal guarantees required of directors for bank loans, which in his view contradicted the limited liability concept. In his words, “This is something very problematic. Not everyone has good credit, so [it’s] difficult for us to find someone qualified for this post [of independent director].” He also criticised the dilution of family representation on the board, arguing that a family-dominated board is “exactly what our shareholders want.”

The above narratives of family directors, which reflect deeply held beliefs, have implications for board practices. However, regulations have the power to “constrain” family directors. Regulatory interventions take the form of fines, penalties, court cases and other forms of legal action against directors for non-compliance. It is expected that family directors will adopt strategies such as symbolic compliance to avoid the constraining powers. Directors justified their strategy of symbolic compliance on various grounds such as costly and burdensome regulations, pointing out the salaries of legally imposed posts such as CFO, head of internal control and company secretary on a full-time basis, in addition to appointing independent board members. One founder of a family company estimated the incremental costs of compliance, saying, “The changes do not align with the entrepreneurial spirit of running companies”. Rules and regulations are deemed to constitute a “considerable burden” not only in terms of costs but also in terms of a significantly higher administrative load. Getting around the rules and regulations is a reasonable choice for them. The recognition of the importance of compliance eventually led to a higher degree of formalisation to intensify family control, such as the development of an internal code of conduct or administrative adjustment for maintaining secrecy. By reporting minimal compliance, they avoid regulatory intervention. In particular, their box-ticking strategy of showing compliance on paper tends to allow them to successfully avoid regulatory interventions.

6.4. Reflexive deliberations of family directors: opening the black box

The above sections discussed how reforms were resisted by family directors. This section also reflects on why this is so. Drawing on reflexive deliberations of family directors, it opens up the black box of interactions. We do so by examining two important elements of reflexive deliberations: “contextual continuity” and “contentment with prioritised concerns” as depicted in and .

6.4.1. Contextual continuity

Following Mutch’s (Citation2007) work, we sought to do a life history interview with a founding family director alongside interviews with other family directors to empirically substantiate reflexive deliberations originating from their contextual continuity as depicted in . Our life history interviewee was Mr X, founder and former chairman of the board of directors of A Group (name and company anonymised). He was a top industrial entrepreneur who had been actively involved in the industrial sector of Bangladesh since the period of union with Pakistan. During the life history interview, he shared how his early experiences, in terms of economic, political and social contexts, had shaped his business ventures. He was the eldest son of a jute businessman and had been born and brought up in a religious family in a small suburb near Dhaka, the capital city. Having graduated in commerce, he had gone on to study chartered accountancy to become a professional accountant, partly persuaded by his family members. During that time, Pakistanis dominated white-collar jobs to the apparent detriment of qualified Bengali candidates. Ethnic tensions were very high. On completion of his articleship with a renowned audit firm, he had returned to his suburban home in 1963 and engaged in the family jute business. The sense of discrimination against Bengalis in white-collar jobs had discouraged him from joining the accountancy firm, and he had joined his father’s business instead. During his professional training, he had had opportunities to learn about the jute business while auditing one of the largest jute mills. His decision to join the family business had been somewhat unexpected. He said, “My extended family was a bit unhappy with my decision initially, but later it was OK. But my mother was always against moving to Dhaka city.”

His decision to stay in his childhood home after professional qualification, to be around the business with which he had grown up and not to take a white-collar job in the context of ethnic tensions in the country is indicative of his communicative life of mind. One way to understand this is that he sought refuge in his old ways and wanted to avoid the structural/cultural constraints with which he might have been confronted had he taken an accountancy job. Archer argues that actors (in our case, the founding director) reflexively designating “similars and familiars” as the ultimate concern tend to invest themselves to a significant extent in the social order. Since expression and realisation of their concerns necessarily entails deep embeddedness in a localised social context, this kind of reflexive deliberation serves to mediate actions in the continuity of the context (Archer, Citation2003).

During his business career, Mr X diversified over time and moved into new business sectors only when threats to the continuity of context were real. His first change came when the family business was nationalised in 1972, following Bangladeshi independence. This was something of a shock to him and his family: suddenly they were out of business. His contextual continuity was shattered. His preference for cash and liquid assets, as will be mentioned later, was perhaps born out of this bitter experience. The business was returned to the family in 1978. At the same time, the jute sector in Bangladesh was facing a severe crisis (Papanek, Citation1967). The small business was allowed to continue during the period of nationalisation in Bangladesh. He moved into his father-in-law’s family businesses involving “export and import of goods”, which led to his current main business.

Mr X had continued his journey in a familiar and similar context throughout his business life, except during the crisis period between 1972 and 1978. During his interview, he spoke about many failures in business. He talked about trust and control being important in business. His largest business was stock exchange listed very early in Bangladesh’s stock exchange history. Two reasons might be surmised for listing his family business on the stock exchange. First, he had a personal preference for equity rather than debt. He told us that he hated being indebted, partly because of his religious background and the bitter lessons learned from his many previous business failures. The second reason was his fear of future nationalisation. Becoming a PLC, he felt, was a safer route to avoid being put out of business overnight, or at least sharing the risks. Nevertheless, he had consistently retained control of the business, kept the factories close to his home in the Dhaka suburb where he lived, and employed people from his family, villages and surrounding areas.

Except for his one child, all of his children are active in his ventures. Currently, his elder daughter, with her husband and children, are actively involved in the business. Board positions, subject to retirement after each five-year term, are limited to Mr X, his wife and close family members. The positions of all CEOs in the listed PLCs, except for one, are kept within the family. He mentioned the commitment of the senior management team, some of whom are his relatives, who are in charge of overall management and administration. Mr X has always looked after decision-making and cash control. As he mentioned, “Nowadays my grandchildren are getting active in business. They are doing well. Official autonomy and authorisation are there, but usually they consult with me before finalising major decisions.”

Mr X’s reflexive deliberation, prioritising the continuity of the context, became vivid with reference to the issue of retaining corporate control and management with his family members and trusted ones. From starting his entrepreneurial journey with the family jute business through to ending up with diversified industries, in all aspects of his narratives the overlap between family and work was apparent. His contexts included being born into a business family, which had exposed him to business, and then marrying into a business family, borrowing capital from his father-in-law and working with experienced partners, some of whom are still active in management. According to his daughter, who hold director position in several PLCs, his personal preference for cash-rich businesses, sustainability and avoidance of bank loans had come at the cost of growth. Senior management (including his grandson) also mentioned his “conservative and calculative mindset”. His “conservative attitude” to decision-making and “comfort” in getting the next generation on board embodied his smooth dovetailing of concerns.

Given Mr X’s life project, it is no surprise that he regarded running the PLCs in the interests of general shareholders as a “regulatory burden” rather than a “necessity”. Regarding dispersed shareholders’ interests, he commented, “We are giving dividends; if they [non-family shareholders] are not happy, aren’t they free to invest elsewhere?” His preference for appointing “known” people as independent board members was apparent in his strong reservations about opening up “his” companies to independent external scrutiny. This reflected deep-seated scepticism about the benefits of reform, which, in his words, added “unnecessary formalities and cost of appointing full-time professionals”. During his interview, he emphasised the importance of active day-to-day management with direct and close control as the key to business success.

The importance of informal close control was also echoed in a comment by a senior manager, who recalled Mr X’s strategic leadership:

We sometimes delayed lunchtime. Then sir [Mr X] started to join us during lunchtimes and declared the sponsoring of lunch facilities with the company’s funding. Following the lunch, he used to talk with us about our work, give appreciation or guidance.

Unlike non-family PLCs, in family PLCs the objectives of profit maximisation and growth need to fit well with the family’s objectives of income, wealth and the longer-term stability of the business for future generations. Thus, growth is more than acceptable, albeit within limits. One CFO commented on not pursuing opportunities for growth, which, in his view, is a “disregard to [non-family] shareholders’ interests”. He continued: “Growth has to be within the comfort zone of the [family] owners.” His comment reflects the significance of reconciling family and company objectives in family PLCs. One CEO encapsulated how the focus on family sometimes restricts growth ambitions: “I can feel my dad’s sentiment. It [the company] is precious, a good earner. Sometimes I feel like we are steering it too much towards serving family. He does not want the hassle of growing.”

Preference for long-term continuity, financing from non-debt sources and a cash-rich business was echoed in the family directors’ comments.

Mr X had developed and nourished his life project through the contextual anchorage of the family business. The life projects of other directors interviewed did not appear exceptional in this respect. Some talked about how they had been exposed to their family business from an early age. One director commented, “Our [siblings’] attachment was built up since childhood. I used to accompany my father during factory visits, meetings and business trips. We knew that there were big shoes to fill.” Family commitment, real interest in the business, freedom, flexibility and being one’s own boss were cited as common reasons for joining family PLCs.

6.4.2. Contentment with prioritised concerns

The deliberations of directors reflect their dovetailing of concerns through which they prioritise their ultimate “concern” and define their life projects (constellation of concerns). It would seem that directors’ prioritisation of concerns entailed deep embeddedness in the continuity of a family business context.

Our interviews with some young directors seemed to suggest that they had never conceived of projects beyond their contextual confines, while for others it had been a tough decision, as they had wanted careers outside the family business. Some had even pursued them but had been unable to maintain them for various reasons. As one second-generation director said:

After CPA, I worked for a few years in the USA, which I never thought of; now I feel like it wasn’t me … I was brought up in a business environment, so it’s really hard to keep myself detached from business.

Interviews with second- and third-generation family directors provided us with interesting insights into their emotional and material investments in their fathers’ ideals. These directors confirmed that they had acquired their positions through inheritance. Now that they are in the businesses and following their fathers’ legacy, trusting friends of their fathers and maintaining existing traditions are their primary concerns. As one director said: “I am relatively inexperienced, so before finalising any major decision I consult with Mr R [general manager], who has been with our business from the very beginning.”

The importance of “trust and relationships” was also reflected in the comment that “I do talk to my brother [CEO] outside of work about work. We have a work relationship and a sibling relationship. It’s not that we have disagreements.” Echoing the same idea, another director opined that working in a family business is challenging when, in his terms, “You are taking steps in a legend’s shoes”. These stories encapsulate the values and priorities that the young directors assign to family sentiment and traditions, not to mention that contextual continuity accompanies the resources and interests. Even the Western-educated heirs dared not risk losing ties with their fathers’ networks and social capital. The dovetailing of concerns of directors thus reveals how concerns and contexts become inseparable and mutually reinforcing.

The dovetailing of concerns, as presented above, seemingly depends on a secure contextual anchorage, such that, by sharing common reference points and through their communality of experiences, “similars and familiars” can be interlocutors, capable of complementing a subject’s own deliberations. This suggests the directors’ comfort and openness to walk in the shadows of their families and trusted ones. Actors’ contentment with the contextual continuity may lead them to renounce opportunities and self-interests (Archer, Citation2003). Such renunciation is evident when a young director foregoes career opportunities outside the family business or when founders in their 70s reject retirement to spend time in business. Renunciation is not self-sacrifice for them “when their concerns are vested in their proximate context, for they know that their own contentment depends upon the stability of the micro-world” (Archer, Citation2003, p. 354).

To summarise, the evidence presented above is indicative of contextual continuity, the prioritisation of the actors’ family/trusted relationships and the associated contentment characterise a pattern of reflexivity that, according to Archer’s (Citation2003) theorisation, creates disposition for stability over change. Put differently, family directors having this pattern of reflexivity are expected to act strategically. Reflexivity illuminates how embodied dispositions emerging from the socioeconomic stability and life projects of directors have become significant in relation to implementing regulatory changes.

This theoretical development departs from existing theories within the family business literature dominated by socio-emotional wealth, familiness, stewardship theory, social capital theory, resource-based view and behavioural theory. Whilst they are insightful in highlighting both material and emotional concerns of family directors, they are limited in delving into deeper concerns/life projects. As a consequence, previous studies often underestimated variations of responses to reforms and seemingly dismiss superficial compliance as a structural/institutional problem (Kabbach de Castro et al., Citation2017). Focusing only on an overgeneralised notion of economic and non-economic interests tends to prevent a conceptualisation of agency (reflexivity) from a sufficiently accommodating diverse range of non-economic concerns implied yet playing a significant role in shaping responses to board reform. Below we seek to make a case for why developing an account of reflexive deliberations of reforms provides an understanding of non-compliance, overstating compliance or superficial compliance.

Reflexive deliberations in a variety of ways are derived from subjectivities of actors. We see how conflicting subject positions of resisting actors, as “shareholders’ steward” versus as “manager in own business”, give rise to challenging meaning and acts within the organisation, for example, interpreting the requirement of “board independence” as a “passing fad”, “leakage of secrecy” or “costly administrative burden”. These meanings are directed towards disrupting and subverting the underlying meaning of “accountability” (to shareholders) ascribed to the requirement of “board independence”. It is also evident that embodied dispositions emerging from the contextual continuity (such as being born into a business family and pursuing a family business career), lack of shareholder activism and an under-developed capital market, etc. have been significant in relation to implementing regulatory changes. Preserving family control, confidentiality and the importance attached to trust, relationships and informal processes, as discussed in Section 5, reinforced family directors’ inclination towards maintaining the internal governance arrangements. Strategically, they take a non-confrontational route of resistance involving coordinated lobbies, counter-narratives and close family control via formal and informal mechanisms. Eventually, the outcome is a reproduction of largely (pre-reform) ex ante board practices, with minimal change ex post.

7. Concluding remarks

Returning to the question posed earlier regarding family directors’ response to reform, our paper tells a story of resistance and symbolic compliance in a context in which listed companies, requiring separation of ownership and control, are managed and run by family owners and their trusted managers. Family directors are expected to act like shareholders’ stewards. Contrary to expectations, family directors dominate corporate board processes. Non-family directors, including independent directors, remain bystanders on family-dominated boards.

Empirically, the paper provides visibility to diverse concerns of actors such as inheritance, securing unfettered control (sometimes to keep away other family members), religious values and confidentiality. We have argued that economic concerns alone do not fully explain the actions of resisting directors. For example, the decision to forgo growth opportunities in favour of “doing business within comfort zones” or “not pursuing bank loans on religious grounds” clearly goes against their own and shareholders’ economic interests. They deliberately prioritise such concerns over the economic interests. More importantly, as depicted in the theoretical discussion, non-economic concerns often appear powerful in shaping resistance strategy. For example, the paper shows how one founder’s personal religious values and preference for cash-based business strongly mandated his approval for decision-making and restricted democratic/professional decision-making. In the view of some of the next-generation family members, this led to compromising growth and ran against the shareholders’ interests including their own. This implies that had the prioritisations of family directors’ concerns been different, the outcome of the reform would not be the same as articulated in this paper. The contributions of the paper to the family governance literature are twofold.

First, prior research debated on distorted/symbolic compliance, seen as resistance in this paper, often reducing this to institutional embeddedness or overgeneralised notion of interests/conflicts in family PLCs (Sobhan, Citation2016; Yildirim-Öktem & Üsdiken, Citation2010; Yoshikawa et al., Citation2007). For example, Sobhan documented “overstatement of compliance” in Bangladeshi family-controlled PLCs. Extending Sobhan’s work, we argue overstatement of compliance is the mere outcome of a process of interaction and strategic responses. We have demonstrated how family directors deploy the resistance strategies such as organisation of coordinated lobbies, counter-narratives and codification of internal rules to maintain their power and keep the change minimal. We have also demonstrated why they wish to maintain minimal change. This takes us to our theoretical contributions.

Second, the paper makes a case for a new theoretical dimension – reflexivity – which enables insight into directors’ deeper concerns/life projects. We have demonstrated that family directors translate regulatory changes in light of their personal concerns, ideologies and subjectivities derived from their life projects. The diverse subjective interpretations can be seen as the outcome of actors’ reflexive deliberations, which guide their actions, and provide shared symbols and identities that define their interactions. By tracing the processes through which imposed regulations are implemented, the analysis opens the black box of interaction and shows how changes in regulations set in motion strategic responses that only reproduce the traditional (family) governance structures. Seen this way, this new theoretical idea complements the existing set of theoretical frameworks within family business literature that aim to understand diverse range of economic and non-economic concerns of family directors.

Finally, the paper has potential policy implications beyond Bangladesh, because symbolic compliance remains a challenge to practical policy reforms in various settings. We emphasise the need to go beyond the demarcation of resistance versus compliance to appreciate more micro, routine, subtle and discursive forms of resistance and its situated construction. Policy reforms often rest on simplistic assumptions about the performativity of regulations, such as changes in practices and intended outcomes. Looking more closely at compliance from the perspective of resisting actors informs the inherent challenge of institutionalising Anglo-American best practices in diverse governance and institutional settings.

We acknowledge, methodologically, empirical reconstruction of reflexive deliberations is inherently challenging (Mutch, Citation2007). Participant observations or shadowing the actors would have provided different insights into the lived experience of family directors and thereby an even better understanding of their reflexivity. The failure to do so was mainly because of a shortage of time, resources and lack of access to become a participant observer. In terms of acknowledging the limitations of the current theoretical framework and possible future research pathways, the combined analysis of “reflexivity” and broader institutional conditions such as a morphogenetic approach (Ahmed & Uddin, Citation2018; Archer, Citation1995) as a central theoretical axis would have added much broader explanations of resistance. Furthermore, reflexivity coupled with institutional analysis is an interesting methodological strategy to advance that allows an understanding of structural and actors’ power while exposing the reality of compliance. This perhaps will find ways for emancipation from repeated corporate governance scandals, reforms and economy-wide consequences.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 All six PLCs report some identifiable share of ownership by at least one family member and having multiple generations in leadership positions.

2 World Bank (Citation2009, p. 4) finds that only direct holdings are reported whereas indirect or “beneficial” ownership remains undisclosed.

3 Life history interview calls on interviewees to provide a subjective account of their life over a certain period or about certain aspect/event (Bertaux, Citation1981).

4 The biographical approach captures interviewees' work, life and family backgrounds.

5 Seven preliminary interviews (not included in the count of 25 interviews) were conducted. These interviews provided an informed basis on which to interview the family directors and helped careful development of the interview guide.

6 This involved the formation of a new capital markets regulatory body, enactment of a new Companies Act, changes to exchange and listing rules, and recent publication of corporate governance codes.

7 This study is based on the Corporate Governance Guidelines or Code issued in 2012, which is hard law for listed PLCs (BSEC, Citation2012). In 2018, a revised code was issued keeping the board requirements the same with additional provision for the formation of compensation committees.

8 The charging of interest is prohibited in Islam.

References

- ADB. (2013). Bangladesh’s efforts on capital market reforms. Asian Development Bank.

- ADB. (2016). Capital market development in Bangladesh: A sector reform perspective. Asian Development Bank.

- Aguilera, R. V., & Crespí-Cladera, R. (2016). Global corporate governance: On the relevance of firms’ ownership structure. Journal of World Business, 51(1), 50–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2015.10.003

- Ahmed, S., & Uddin, S. (2018). Toward a political economy of corporate governance change and stability in family business groups: A morphogenetic approach. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 31(8), 2192–2217. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-01-2017-2833

- Archer, M. S. (1995). Realist social theory: The morphogenetic approach. Cambridge University Press.

- Archer, M. S. (2003). Structure, agency and the internal conversation: The morphogenetic approach. Cambridge University Press.

- Bertaux, D. (1981). Biography and society: The life history approach in the social sciences. Sage Publications.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. Sage.

- BSEC. (2012). Corporate governance guidelines. Bangladesh Securities and Exchange Commission.

- Caetano, A. (2015b). Personal reflexivity and biography: Methodological challenges and strategies. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 18(2), 227–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2014.885154

- Chua, J. H., Chrisman, J. J., Steier, L. P., & Rau, S. B. (2012). Sources of heterogeneity in family firms: An introduction. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(6), 1103–1113. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2012.00540.x

- Federo, R., Ponomareva, Y., Aguilera, R. V., Saz-Carranza, A., & Losada, C. (2020). Bringing owners back on board: A review of the role of ownership type in board governance. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 28(6), 748–371. https://doi.org/10.1111/corg.12346

- Gómez-Mejía, L. R., Cruz, C., Berrone, P., & De Castro, J. (2011). The bind that ties: Socio-emotional wealth preservation in family firms. Academy of Management Annals, 5(1), 653–707. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2011.593320

- Hassan, M. (2019). Loan scams, soaring non-performing loans, bank owners increasing clout hurt banking sector. Dhaka Tribune.

- Hsu, H., Shou-Min, T., & Che-Hung, L. (2021). Family ownership, family identity of CEO, and accounting conservatism: evidence from Taiwan. Accounting Forum. https://doi.org/10.1080/01559982.2021.1957542

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(76)90026-X

- Kabbach de Castro, L. R., Aguilera, R. V., & Crespí-Cladera, R. (2017). Family firms and compliance: Reconciling the conflicting predictions within the socio-emotional wealth perspective. Family Business Review, 30(2), 137–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486516685239

- Lien, Y., Teng, C., & Li, S. (2016). Institutional reforms and the effects of family control on corporate governance. Family Business Review, 29(2), 174–188. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486515609202

- Lubatkin, M. H., Schulze, W. S., Ling, Y., & Dino, R. N. (2005). The effects of parental altruism on the governance of family-managed firms. Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 26(3), 313–330. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.307

- Martin, G., Campbell, J. T., & Gomez-Mejia, L. (2014). Family control, socioemotional wealth and earnings management in publicly traded firms. Journal of Business Ethics, 133(3), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2403-5

- Mohamad-Yusof, N. Z., Wickramasinghe, D., & Zaman, M. (2018). Corporate governance, critical junctures and ethnic politics: Ownership and boards in Malaysia. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 55(2), 33–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2017.12.006

- Mutch, A. (2007). Reflexivity and the institutional entrepreneur: A historical exploration. Organization Studies, 28(7), 1123–1140. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840607078118

- Nahid, F., Gomez, E. T., & Yacob, S. (2019). Entrepreneurship, state–business ties and business groups in Bangladesh. Journal of South Asian Development, 14(3), 367–390. https://doi.org/10.1177/0973174119895181

- Nakpodia, F., Adegbite, E., & Ashiru, F. (2021). Corporate governance regulation: a practice theory perspective. Accounting Forum. https://doi.org/10.1080/01559982.2021.1995934

- Papanek, G. F. (1967). Pakistan’s development, social goals and private incentives. Harvard University Press.

- Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., Nicholls, C. M., & Ormston, R. (2013). Qualitative research practice: A guide for social Science students and researchers. Sage.

- Siebels, J.-F., & zu Knyphausen-Aufseß, D. (2012). A review of theory in family business research: The implications for corporate governance. International Journal of Management Reviews, 14(3), 280–304. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2011.00317.x

- Sobhan, A. (2016). Where institutional logics of corporate governance collide: Overstatement of compliance in a developing country, Bangladesh. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 24(6), 599–618. https://doi.org/10.1111/corg.12163

- Sobhan, F., & Werner, W. (2003). Comparative analysis of corporate governance in South Asia: Charting a roadmap for Bangladesh. Bangladesh Enterprise Institute.