ABSTRACT

On 26 April 2016, Thailand introduced new tax evasion legislation which was enacted by Parliament in April 2017. The Act amended previous anti-money laundering legislation, transferred prosecution of serious tax evasion cases from the Revenue Department to an anti-money laundering unit and permitted the seizure of an accused’s assets once criminal proceedings had been initiated. Drawing on institutional theory, our study examines why this legislation was introduced. It focusses on the formal institutions and legitimacy. Specifically, it reports on 35 interviews with a range of stakeholders to ascertain their views about the reasons behind this legal change. The results suggest that external and internal legitimacy concerns acted as catalysts for the change. These results have practical implications for those investigating the issue of tax evasion and policy implications for those examining whether legislation will impact the incidence of tax evasion within a country.

1. Introduction

Tax evasion is a global challenge faced by all governments (Alm, Citation2021). The issue is often seen as detrimental to a country’s development since it may have a negative influence on economic growth (Omodero, Citation2019) as well as the ability of the government to fund spending on public services (Androniceanu et al., Citation2019; Hasseldine & Morris, Citation2013; Sikka, Citation2010, Citation2013). For many decades, policymakers have sought solutions to tackle the growing problem of tax evasion (Islam et al., Citation2020).

While Thornton et al. (Citation2019) suggest that it may be difficult to measure the exact amount of revenue lost to the state through tax evasion, it can be large for many countries. For example, the “tax gap”Footnote1 in the United States (US) was recently estimated by the Internal Revenue Service at $381 billion per year (IRS, Citation2019). For others, like Thailand, there has been no official tax gap estimation (Sophaphong et al., Citation2017). However, Medina and Schneider (Citation2018) calculated that the average size of the shadow economyFootnote2 for the period 1991–2015 was 50.63% of Thailand’s GDP. This percentage is much higher than the figure of 8.34% reported for the US. Thailand was ranked as having the 13th largest shadow economy among 158 countries (Medina & Schneider, Citation2018). Moreover, a study by the Anti-Money Laundering Office of Thailand identified tax evasion as one of the five major crimes which contributed to approximately 86% of all criminal assets in Thailand in 2016 (FATF, Citation2018). Thus, it is not surprising that the issue of tax evasion has become a priority for the Thai government (Benjasak & Bhattarai, Citation2019). However, what is unusual with the Thai government’s introduction of new legislationFootnote3 in 2017 is that it concentrated on the seizure of an accused’s assets at the beginning of a criminal case, the categorisation of tax evasion as a serious crime, as well as the prosecution of tax evasion cases by the Anti-Money Laundering Office.

On 26 April 2016, Thailand introduced legislation to elevate the crime of tax evasion to a “serious” money laundering offence.Footnote4 Under this legislation, the Revenue Department has the power to initiate legal proceedings before the Anti-Money Laundering Office prosecutes the case. The legislation received royal assent on 30 March 2017 (Table 1 – see online supplementary file) and became effective from 2 April 2017. While this was Thailand’s most recent tax evasion legislation in 18 years, to date, there have been no legal proceedings against taxpayers under this legislation.

Given this political and cultural context, our study examines why tax evasion legislation was introduced in Thailand by drawing on institutional theory, focussing on formal institutions and legitimacy. Specifically, it examines perceptions and asks: why was the current tax evasion legislation introduced in Thailand during 2017? The study draws on 35 interviews, conducted with a range of stakeholders, to ascertain their views about the institutional forces associated with this change in the law on tax evasion. The results suggest that the legislation was introduced for legitimacy reasons in response to internal pressures within the country as well as external influences where the government needed to be seen to act. To date, there remains a dearth of studies drawing on insights from key stakeholders at a time when new tax evasion legislation was introduced; instead, a lot of research in the area focuses on studying the incidence of tax evasion (The World Bank, Citation2015), the mechanisms whereby tax payers attempt to illegally avoid paying their taxes (De Boyrie et al., Citation2005) and the reasons for evading tax (Besley et al., Citation2014). The current paper contributes to the literature by examining a government’s decision to tackle the issue of tax evasion using legislation; the process behind the introduction of such legislation is studied. Because tax evasion is a sensitive issue and the motivations for introducing legislation on this issue can be complex, it is “fundamentally hard to study” (Alstadsæter et al., Citation2019, p. 2074). This study, therefore, adds to our understanding of an under-researched area.

Our study makes three contributions to the current tax evasion literature (Horodnic, Citation2018; Mulligan & Oats, Citation2016). First, it identifies why tax evasion legislation was introduced through the activities of actors at varying levels (macro and micro) by drawing attention to actors’ interpretations and agency in tax evasion policy. In understanding actors’ perceptions, motivations and actions this allows the study to show that since the introduction of the new legislation, which is likely to be costly and potentially risky, it is best introduced by those who are skilled at using their formal authority or social capital (Battilana et al., Citation2009). Second, the study highlights that both internal and external legitimacy concerns may explain the introduction of new legislation as it is important to explore and understand the internal and external workings and environments of the institution. It has been argued that studies must consider both internal and external sources of legitimacy which may well be embedded within the organisation, including both at its foundations and within the practices as well as in the actions of its members (Drori & Honig, Citation2013; Lawrence et al., Citation2011). Thus, the contribution of our study seeks to understand how attempts were made to secure internal and external stakeholders’ continued support for the new legislation by building such legitimacy (Drori & Honig, Citation2013; Wanderley et al., Citation2021). Finally, our study highlights the institutional contexts within which actors work to pursue both external and internal legitimacy for such policy work (Lawrence & Suddaby, Citation2006). Currently, there are very few studies in the tax literature that seek to understand the process and the context in which a change in tax evasion policy occurs (Dell’Anno, Citation2009). We consider “top-down processes” allowing higher-level structures to shape the “actions of lower-level actors” alongside “counterprocesses … [which enable] lower-level actors and structures [to] shape the contexts in which they operate” (Scott, Citation2001, pp. 196–197).

This article is organised as follows. Section 2 presents an overview of the existing literature on tax evasion and the new legislation in Thailand. The section further outlines the theoretical framework adopted in the study. Section 3 outlines the qualitative research design which includes the data collection, sampling and analysis. Section 4 provides the Thai context of the study. Section 5 reports the findings and finally Section 6 focuses on the discussion and contributions.

2. Literature and theoretical framework

2.1. Tax avoidance and evasion

There is a distinction in the literature between “tax evasion” and “tax avoidance”. For example, The International Bureau of Fiscal Documentation (IBFD) highlights that “avoidance is a term used to describe taxpayer behaviour aimed at reducing tax liability that falls short of tax evasion” (IBFD, Citation2009, p. 30). Thus, tax avoidance is seen as legal. By contrast, tax evasion is defined as the illegal non-payment of tax; this non-compliance with tax legislation is a crime which is punishable by some sanction. In practice the differences between tax evasion and tax avoidance activities are “complex with numerous shades of grey in between legal and illegal practices” (Sikka, Citation2014, p. 135). The difference depends on the legitimacy of a taxpayer’s activities (Sandmo, Citation2005) and this legitimacy will often have to be decided by a court if there is “a legal challenge by the tax authorities” (Sikka, Citation2014, p. 135).Footnote5

The many definitions of tax avoidance in the literature vary across different groups. Traditional definitions simply note that tax avoidance is legal and acceptable (Tax Justice Network, Citation2019). Currently, there is no definition of tax avoidance in the Revenue Code of Thailand and the attitude of the Thai society towards tax evasion is not clear (Meesang & Neesanan, Citation2008). Tax evasion, in Thailand, is treated by the government as money laundering under the newly introduced legislation, although the latter is typically more concerned with the process whereby the origins of illegally obtained funds are concealed (Levi & Reuter, Citation2006) and the financing of terrorism (Teichmann, Citation2019). The Thai government’s decision to link tax evasion with money laundering and to assign the prosecution of tax evasion cases to the Anti-Money Laundering Office is unusual and differs from the approaches of other countries to this issue, as highlighted in the literature.Footnote6

The traditional neoclassical approach to explaining the motivations for tax evasion is based on the model by Allingham and Sandmo (Citation1972). Their model assumes that rational taxpayers “seek to maximise the utility of their taxable income by weighing the benefits and costs of compliance with the utility of non-compliance” (Horodnic, Citation2018, p. 868). If the net costs of compliance are low relative to the utility of non-compliance for many taxpayers, tax evasion may be a sizeable issue for a government which may struggle to fund public services and State-backed commitments. Such a government may introduce legislation, therefore, to ensure that the cost of non-compliance (in terms of expected penalties and/or the increased likelihood of detection) outweighs any utility that the taxpayer may derive from non-compliance (Horodnic, Citation2018; Williams & Yang, Citation2018). However, the Allingham and Sandmo model (Citation1972) does not take account of the social and psychological factors that make tax evasion different from a utility-based cost–benefit evaluation (Torgler, Citation2003). Dissatisfaction with the approach of Allingham and Sandmo (Citation1972)Footnote7 has led researchers to consider other non-economic factors behind government decisions to legislate on tax evasion (e.g. Williams, Citation2014).

One strand of the literature suggests that a nation’s institutional culture can affect tax evasion behaviour (and hence the need for anti-tax evasion legislation) since institutions have an influence on the governance of a society and individuals’ behaviours (Erserim, Citation2012).Footnote8 Within this strand of the literature, different dimensions of culture have been used to explain tax evasion (Bame-Aldred et al., Citation2013). For example, Hofstede’s (Citation1980) dimensions of culture (uncertainty avoidance, power distance, individualism and masculinity) have been linked with international tax compliance diversity across countries (Brink & Porcano, Citation2016; Richardson, Citation2008). Others have suggested that the literature on “tax-cultural considerations [should not be limited] to the side of taxpayers, but … widen its understanding” by recognising that the “topic of “tax culture” is located at the intersection of economics, sociology and history” (Nerré, Citation2004, pp. 153–154). Nerré (Citation2004, pp. 163–164) therefore proposes that a national tax culture can be defined as “the entirety of all interacting formal and informal institutions connected with the national tax system and its practical execution, which are historically embedded within the country’s culture”. From this definition, Nerré (Citation2004, p. 164) argues that, to understand a country’s tax culture, “a vast number of actors and institutions have to be studied as well as the procedures and processes of their interaction”.

A recent development in the tax literature focuses on the ability of institutional theory to explain different aspects of tax (such as tax evasion). For example, Ostapenko and Williams (Citation2016, p. 5) argue that “tax evasion … [may] result from the lack of alignment of formal institutions (the codified laws and regulations [of a country]) with informal institutions, namely the norms, values and beliefs” of that country. The authors suggest that “when the norms, values and beliefs [of a country] align with the codified laws and regulations, there will be little or no … tax evasion”. When they do not align, new legislation may be needed, or the government may attempt change in the informal institutions. Legislation which increases the probability that tax evasion may be detected, and imposes sanctions on those evading tax, may change social behaviour as well as social perceptions about whether tax evasion is socially acceptable. Horodnic (Citation2018, p. 871), from an analysis of over 400 databases, argues that the “influence of formal institutions on tax morale represents the main research topic in the tax morale literature”. This literature sees a breakdown in the social contract between government and taxpayers as a key reason for tax evasion and those who pay tax in return for government services are dissatisfied with the terms of the exchange. Studies in this area suggest that tax morale may be improved by greater trust in government institutions (e.g. Andriani, Citation2016), Parliament (e.g. Chan et al., Citation2018), the legal system (e.g. Vythelingum et al., Citation2017) and the tax authority and its officials (e.g. Torgler et al., Citation2008) among others. Less trust in these institutions and organisations among taxpayers may be associated with greater levels of tax evasion and a need for government action. Our study employs an institutional theoretical lens to understand why a legislative change about tax evasion (or a change to what the literature sees as the formal institutions) was introduced by the Thai government. As such, our study adds to the literature in this area and responds to Horodnic’s (Citation2018) call for subtler investigations of a topic where empirical evidence is difficult to uncover.

2.2. Theoretical framework: institutional theory

Institutional theory has only relatively recently emerged in accounting (Mulligan & Oats, Citation2016) and has been growing in popularity as a theoretical lens for the study of tax reform and compliance under the umbrella of tax policy (Horodnic, Citation2018). By drawing on institutional theory, researchers have shown that, although policy processes and behaviour are linked to wider social and cultural beliefs, these structures can change as new policies are introduced and implemented (Burch, Citation2007). Institutional theory also argues that the policy process, in this case understanding why anti-tax evasion legislation was introduced, will not proceed without the action of an institution (namely a government) (Mahmud, Citation2017). The actors involved also play an important role in shaping the institutions as their actions reflect the outcomes from the institutions. Therefore, it is imperative to understand the institutions involved in the introduction of such legislation and those actors who influence and inform policy. New legislation often requires public support and one way of facilitating public support is through legitimacy. Legitimacy entails a general confidence among the public that a government’s power to make binding decisions for a nation is justified and appropriate (Dahl, Citation1998). Thus, institutions and legitimacy are fundamental for understanding the introduction of the tax evasion policy process in Thailand.

However, before discussing institutions and legitimacy within the tax policy process in Thailand, it is important to highlight that different groups of actors co-exist at numerous levels and with varying amounts of power and influence within the realms of formal institutions and legitimacy. Mulligan and Oats (Citation2016) argue that there are different elements of policies which range from policy formation (which involves individuals at the macro level who develop and enact tax laws at the economic and political level) to the micro implementation of tax plans and associated processes at the organisational level.

At the macro level, rules and regulations are required for society and thus it “sets the dominant ideology for the organizational field to translate into organizational controls” (Hopper & Major, Citation2007, p. 56). The organisations and actors involved in the tax evasion legislature in Thailand include the government itself but also wider external stakeholders such as international organisations, i.e. Asia Pacific Group (APG) on Money Laundering and the Financial Action Task Force (FATF). At the macro-level, institutions iteratively shape and are shaped by the judgements and actions of individual actors (Barley, Citation2008; Dacin et al., Citation2010). At this level, attention focusses on the policymakers within government who are responsible for shaping and resourcing policy narratives. The micro level comprises individual organisations and primary actors (Mulligan & Oats, Citation2016) and how and why they apply such policy initiatives (Kvidal & Ljunggren, Citation2014). At the micro level we argue that understanding those tax professionals from the Revenue Department of Thailand who are “in-house” is important to garner the different levels of engagement; thus, our study seeks to explore the issue at the micro level with those “who are charged with managing the organization’s tax functions” (Mulligan & Oats, Citation2016, p. 10).Footnote9 By drawing on institutional theory it is possible to link the macro and micro levels of the study because the actors and interest groups operating at these levels of engagement have different interests, sources of power and audiences to whom they must articulate their claims for legitimacy (Mulligan & Oats, Citation2016).

2.2.1. Institutions

Within institutional theory, institutions are central to the functioning of society; they are defined as “the rules of the game in a society or, more formally, are the humanly devised constraints that shape human interaction” (North, Citation1990, p. 3). North (Citation1990) highlights the ways in which institutions reduce uncertainty by providing a safe and comprehensible means for efficient economic exchange. Two types of institutions have been documented within the theory: formal and informal. Formal institutions can be characterised by formal rules, laws or constitutions and are the visible “rules of the game” enforced by governments. Informal institutions such as constraints, customs, norms or culture are the invisible “rules of the game” which are not legally enforced (North, Citation1990).

It is important to note that within institutional theory there are two dominant competing strands: old and new institutionalism. Here, we adhere to new institutionalism as we are focusing on the symbolic role of formal structures (rather than on the informal organisation) (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1991). In this context, the government is responsible for setting up and enforcing the “rules of the game” to control economic performance by shaping the behaviour of individuals via laws, regulations, customs and established patterns (Fogel et al., Citation2008). Introducing legislation is consistent with the notion that building tax morale is based on a social contract which exists between the government and those paying taxes in exchange for public goods and services (Horodnic, Citation2018). If this contract is built on trust between the tax-collecting government and those individuals paying tax, tax morale increases, and individuals are more willing to pay their taxes (Horodnic, Citation2018).

However, tax reform and tax compliance has been a challenge for many countries and their governments which has led to laws and legislation being introduced to address the issue of tax evasion. Not all the pressure to introduce legislation in this area has arisen from within a country; there have been external pressures for countries to address these issues because of capital mobility and potential damage to the global financial system (Eccleston, Citation2006). This study looks at compliance with tax rules and the difficulties that arise when non-compliance occurs in the form of tax evasion. Specifically, it examines one response by a government to the issue of non-compliance in the form of new legislation; views about the motives behind this new legislation are examined to see why the Thai government adopted this legislative response. Such an approach is consistent with the notion that compliance can be based on a multi-dimensional notion of legitimacy which is socially constructed by stakeholders, including international bodies, firms and regulators (Suddaby et al., Citation2017). The role of the context or environment in formulating and implementing policy, including tax policy, is important to understand as it often constrains, shapes, penetrates and renews the institution (Scott, Citation2001). The environment is significant with respect to how the process (of policy change) is shaped, as its demands can persuade institutions to adopt certain roles to safeguard their legitimacy when fundamental challenges arise (Hatch, Citation1997). In this current case, an international organisation insisted that its members take action to combat money laundering and the financing of terrorism where tax legislation became a prominent interest for those with powers regarding revenue (APG, Citation2017). In addition, the Thai government needed to respond to a well-publicised scandal involving tax evasion by current and former Revenue Department officials while satisfying the demands of the military for continued spending on defence and access to new equipment; consequently, the Thai government had to act.

2.2.2. Legitimacy

A great deal of emphasis is placed on the concept of legitimacy within institutional theory (Bitektine, Citation2011). Legitimacy is “a generalised perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions” (Suchman, Citation1995, p. 574). Legitimacy has formed a central component of neo-institutional theory (Meyer & Rowan, Citation1977), explaining both the functioning of institutions and the survival of organisations within institutional fields. It stresses conformity to societal expectations whether these are in the form of legal requirements, social norms, or cultural-cognitive frames of reference (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983; Scott, Citation2001). It has been argued that organisational attributes determine the level of legitimacy that entities receive; the relationships that develop over time, becoming a part of the power hierarchy, endorsement from social actors such as regulators and the public, and the role of process and consultation all play an important part here (Deephouse, Citation1996).

One way of claiming legitimacy is to argue that an institution, such as a government, adheres to global standards. Thus they “conform [to institutional pressures for change] because they are rewarded for doing so through increased legitimacy, resources and survival capabilities” (Scott, Citation1987, p. 498). Furthermore, DiMaggio and Powell’s (Citation1991) sociological institutionalism utilises “legitimacy” as a concept to analyse how public institutions secure consent for their policies from the wider socio-political environment (Wood, Citation2015). The legitimacy of a government as an institution will have an important impact on the level of tax evasion within a country. Perceptions about the fairness of the tax system (rates and application) are key in contributing to tax evasion behaviour. To reduce tax evasion, therefore, “the public must view the taxing authority as legitimate, view the tax system as fair, and government spending as useful and efficient” (Alasfour, Citation2019, p. 253). This highlights the interaction between the individual and collective levels, created subjectively in processes of social construction where legitimacy is understood as a “social judgment” (Bitektine, Citation2011; Haack & Sieweke, Citation2018).

If a change in tax policy (for example, in Thailand’s case, the Anti-Money Laundering Act (1999) was changed to include the new provision which treated tax evasion as a serious tax crime) is implemented without any rationale, it will appear confiscatory; this may, in turn, call the legitimacy of any legislation associated with the change into question (Memon, Citation2013). In other words, a formal institution, such as a government achieves legitimacy by showing that they meet common societal challenges and demands for citizens in an efficient and transparent way, and that their exercise of power is perceived as transparent, rational and equally fair to all citizens (Thornton et al., Citation2012).

Also, it has been argued that those taxpayers, who are less satisfied with their government’s powers to levy taxes, may question its legitimacy and resist its authority (Murphy, Citation2005). Therefore, it is in the interest of a government to garner support and legitimacy from its public for changes to the tax system by responding to social pressures (Carpenter & Feroz, Citation2001) even if comprehensive tax reform is “perhaps the most difficult exercise in public policy in a democratic context” (Radaelli, Citation1997, p. 58). Therefore, the current study highlights two types of legitimacy – internal and external – because the source of legitimacy is important, and its accompanying practices and actions, may originate both inside and outside of the organisation (Ruef & Scott, Citation1998). Firstly, internal legitimacy is predicated on the process and on the policy itself which can lead to “changes in individual beliefs which help explain the rise of resistance to existing institutional arrangements and enhance scholarly understanding of the micro-level antecedents of institutional change” (Haack et al., Citation2020, p. 3). Drori and Honig (Citation2013, p. 347) define internal legitimacy:

as the acceptance or normative validation of an organizational strategy through the consensus of its participants, which acts as a tool that reinforces organizational practices and mobilizes organizational members around a common ethical, strategic or ideological vision.” This view of legitimacy relies upon emergent ‘bottom up’ practices through actors which results from practices “from and spatially dispersed, heterogeneous activity by actors with varying kinds and levels of resources. (Lounsbury & Crumley, Citation2007, p. 994)

The following section now focusses on the research context, Thailand, of the study.

3. Research context

The modern tax system dates from the formation of Thailand’s constitutional democratic monarchy in 1933. In general, value-added tax (VAT) contributes the largest amount to the total tax revenue, representing around 40% of the total tax collected. Corporate income tax is second in importance and personal income tax is third, constituting 35% and 17% of total tax collection respectively. In 2009, tax collection, especially VAT and corporate income tax, dropped 15% compared to the previous year because of the global economic crisis and currency fluctuations.Footnote10 This reduction in the tax collected together with the identification of tax evasion as one of the five major crimes in Thailand by the Anti-Money Laundering Office (FATF, Citation2018) constitutes some of the context against which the new tax evasion legislation was introduced in 2017.

Thailand is also seeking to maintain its international standing with other nations in the Asia-Pacific region on the issue of tax evasion and money laundering. In 1997, Thailand was a co-founding member of the APG on Money Laundering. According to a recent evaluation of the country by the APG, Thailand’s measures to combat anti-money laundering were deemed to be only partially effective while it was found to be non-compliant with some of the technical requirements of an FATF, set up by this international organisation (FATF, Citation2020).

However, according to Tekeli (Citation2011), the national tax culture in Thailand is characterised by a low level of willingness to pay tax. Indeed, in a study of 29 countries, “the [second] lowest level of tax morale is observed for Thailand” (Tekeli, Citation2011, p. 11). Less than 30% of those surveyed from Thailand agreed that tax cheating is never justified – half the average for other Asian countries. Not surprisingly, Thailand’s score in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index stood at 36 out of 100 in 2019. Thailand was ranked 101 out of 180, in terms of its corruption and sixth among ASEAN countries (Transparency International, Citation2020).

Given this political and cultural context, our study examines why tax evasion legislation was introduced in Thailand and examines perceptions and asks: why was the current tax evasion legislation introduced in Thailand during 2017? The next section focusses on the qualitative methodology of the study.

4. Methodology

4.1. Data sources

4.1.1. Interviews

Interviews were conducted with officials in the Revenue Department, the Department of Special Investigation, the Anti-Money Laundering Office and the Fiscal Policy Office of the Thai government. In addition, the views of senior staff in accountancy firms within Thailand were ascertained while the opinions of several key stakeholders (academics, as well as leaders of business-representative organisations) were gathered. Eight individuals were initially contacted and agreed to participate in the study. These initial participants were then asked to suggest other interviewees to contact; a snowball sampling approach was then employed. This approach was adopted because the issue of tax evasion is very sensitive and obtaining information on an activity which is illegal can be problematic.

Thirty-five interviews involving 37 participants were conducted between March and April 2018 throughout Thailand (Table 2 – see online supplementary file). All but one of the interviewees gave permission to have the interview recorded. One director from a big-four accountancy firm refused, so detailed notes were taken during this interview, and these were written up immediately following the meeting.

All interviews were conducted face-to-face via a semi-structured interview guide. In addition to gathering background information, the interview guide had five questions in a section about the new tax evasion legislation. Specifically, participants were asked about their awareness of the new Act and their understanding of why it had been introduced. They were also asked about their awareness of any lobbying over its content. Furthermore, views were sought on the likely impact of the legislation on tax evasion in Thailand and the publicity associated with the new Act. The interview questions were shaped by the lead researcher’s pre-understanding rather than the interview being based solely on the theoretical framework; this led to issues, themes and perspectives which were spontaneously raised by the interviewees or emerged from formal theory (Alvesson & Sandberg, Citation2022). Thus, the experiences and knowledge of participants was ascertained as to why the tax evasion legislation had been introduced in Thailand.

Each interview lasted between 35 and 150 min, was conducted in Thai and subsequently transcribed in Thai. The views of the respondents in these transcripts were read several times and then summarised. Significant answers or quotes that related to the questions asked were then translated into English.Footnote11

4.1.2. Archival data

A range of documented evidence was also collected which included newspapers, magazines, texts of TV programmes and online media (Dallyn, Citation2017). The collection of archival data permitted us to understand: (i) the underlying factors behind the introduction of the legislation; and (ii) the narrative around the legislation as it progressed through Parliament to elicit any challenges to the legitimacy of the draft law. The documentary evidence further enabled us to triangulate the data with respect to investigating links between individual perceptions and observations and the actions that were undertaken at the wider, macro level of the legislation being introduced and implemented.

4.2. Analysis

We adopted an inductive approach to the analysis (Gioia et al., Citation2013). Starting from an analysis of secondary data, we used online articles and official government documents relevant to the new tax evasion legislation to form a baseline of the content in different periods of time as the legislation passed through the Thai Parliament. Analysis of secondary data helped us to examine the motivations and perceptions behind the introduction of the legislation from the wider stakeholders.

As a first step to the primary data collection, further inductive analysis was undertaken to identify, analyse and report on themes within the data at the latent level. This level was used to identify and examine the underlying ideas, assumptions and conceptualisations. We developed first-order codes from individual respondent motivations and perceptionsFootnote12, before comparing emerging systematic labels against one another in what amounted to a form of “cross case” analysis (Eisenhardt & Graebner, Citation2007). The second stage involved manual coding whereby initial concepts in the data were identifiedFootnote13 and grouped into categories (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1998) and key words, phrases, sentences, and paragraphs from the transcripts were highlighted (Miles & Huberman, Citation1994). This led us to the final stage which explored these categories, grouping them into higher-order themes (Gioia et al., Citation2013). The final stage involved the entering of all codes into Microsoft Excel so that the relationship between themes could be determined; the broadest themes (internal and external legitimacy) were placed at the top, with more specific second-order themes (e.g. the wishes of the military) and then third-order sub-themes (e.g. the need to fund military spending) beneath. This stage of the analysis sought to ensure that the findings emerging in the first round of coding could be systematically evidenced in the data, thus ensuring validity (Table 3 – see online supplementary file).

5. Findings

5.1. Conforming to internal pressures

Three triggers led the Thai government to conform to internal pressures when introducing the legislation: public disquiet, government influence and military influence. These insights about internal pressures allow for a “more complete” treatment of the differences in decision-making processes and how internal legitimacy played a supportive role in framing the Thai government’s identity and in shaping its strategic direction and decision-making (Drori & Honig, Citation2013).

5.1.1. Public disquiet

The background to the new tax evasion legislation was explained in detail by 11 of the respondents. Five interviewees argued that the impetus for the legislation was domestic in nature. They suggested that enactment of this law resulted from a high-profile case of VAT fraud in 2015 which called the legitimacy of the tax system into question.Footnote14 The former Director-General of the Revenue Department, the Revenue officials of Samut Prakan Area Revenue Office and accomplices were involved in a Baht 4.3 billion (£97.77 million) VAT Fraud. The National Anti-Corruption Commission found that these officials formed bogus export companies which presented fraudulent tax invoices to claim VAT refunds. Interviewee GOV23, a senior member of staff at the Anti-Money Laundering Office, further explained that the limitations of the Revenue Department’s power to take legal proceedings against the accused and recover the illegally obtained funds in this case, led to a demand amongst the public for a change in the law. Interviewee GOV16 referred to a statement by Mr. Prasong Poontaneat, the former Director-General of the Revenue Department from 2014 to 2018, who claimed that the purpose of the new tax evasion law was to clamp down on the transfer of assets obtained via tax fraud to facilitate the recovery of monies due. Mr. Poontaneat highlighted the recent tax fraud case which had attracted publicity in the Thai financial press during 2013–2015 and caused some disquiet among the population.

Furthermore, Thailand began to harness a growing public disquiet to assert more control in their relationship with the professional bodies to find “a strategy to govern unruly perceptions and to maintain the production of legitimacy in the face of those perceptions” (Power, Citation2007, p. 21).

Interviewee GOV23 noted that the Revenue Department was restricted in accessing information about the properties of the accused. This included properties transferred to other individuals and concealed from the investigation process. This limited the Revenue Department’s ability to retrieve funds owed to the State. Interviewee GOV11 concurred with this view and referred to public disquiet following Mr. Poontaneat’s admission that recovery of funds from large-scale tax evasion was problematic:

[Cases] usually took several years before they were adjudicated upon. As a consequence, properties of the accused often disappeared without trace and only some of the properties associated with a judgement could be collected.

[Before the enactment of this law], the Revenue Code did not include the confiscation of illegal gains as a penalty. Tax authorities were only able to investigate and collect evidence [for confiscation] before submitting details to relevant law enforcement agencies.

5.1.2. Government influence

Interviewee GOV11 explained that the government representatives attempted to justify in operational terms why the new legislation was needed. These justifications were couched in terms of improving the Revenue Department’s efficiency and effectiveness – thereby attempting to increase the public’s trust in the tax collection system. Introducing stricter regulations is one factor that has emerged as a source of public sector improvement (Boyne, Citation2003). And to ensure confidence in the system, those endorsing the procedures will ensure that internal legitimacy is strengthened because, without a minimum degree of legitimacy, institutions have difficulty functioning and loss of legitimacy in the eyes stakeholders is an important contributor to state failure (Brinkerhoff, Citation2005).

5.1.3. Military influence

Militaries often have institutional and informal mechanisms for influencing government policy (Atlı, Citation2010) and, within Thailand, the military has set up new, military-dominated political structures to ensure that they maintain influence over the nation (Chambers, Citation2018). Indeed, the link between the military and economy is a defining characteristic of Thailand (Lambo, Citation2021) with 75% of active state enterprises having military members on their boards of directors. Four of the interviewees suggested that the new tax evasion law was enacted because of the influence of the military on the government. These interviewees argued that the military did not want to endanger the nation’s spending on defence or have Thailand labelled as a tax haven which might lead to a reduction in foreign (military) aid from developed nations such as the US. According to some of the interviewees, this element of the internal environment within Thailand played a role in the proposal of this new legislation. Three interviewees indicated that this military support was vital for the enactment of the legislation and that, without the support of the military, the law would have been successfully opposed by many interest groups. Interviewee GOV7 stated that:

The Revenue Department [had] wanted to enact this legislation for a long time; however, since there were many interest groups [lobbying against it during] the previous [civil] government this had not been possible.

5.1.4. Business influence/lobbying

Having decided that the law was to be given effect through the Revenue Code, respondents indicated that Parliament seemed to reduce the role of the Revenue Department in the implementation of this legislation. For example, four interviewees revealed that the texts of the current proposed tax evasion law were changed from the first draft Bill proposed by the Revenue Department. The first draft Bill had authorised the Revenue Department to temporarily seize the property belonging to an accused person immediately. This clause, however, disappeared from the new law.

Interviewee GOV23 added that an article in the press had queried “how the discretion of the Revenue Department’s authority [would be] exercised”. Specifically, it questioned the moral authority of the Revenue Department to temporarily seize the assets of an accused – especially, in VAT fraud schemes – where “someone in the tax authorities [may have] conspired [with the accused] to commit the VAT fraud [when they were submitting] false tax returns”.

Others agreed that the legislation seemed to be the product of a power struggle between the government and the relatively independent Revenue Department. They pointed out that, as the draft legislation evolved, the power to prosecute a tax evasion case was given to the Anti-Money Laundering Office which was under the supervision of the Prime Minister. Interviewee GOV14 concurred, emphasising that the level of discretion over a tax evasion case given to the Revenue Department changed at this time. For a tax crime to be a “serious” criminal offence under the new legislation, the Director-General of the Revenue Department now had to consult with a committee. Interviewees noted that the Revenue Department had argued against their Director-General having to consult any committee about whether there was a prima facia case. However, the government rejected this argument – possibly because of lobbying, possibly to placate those who saw the Revenue Department as powerful, and possibly to punish the Revenue Department for the public disquiet over the fraud case which had involved the Department’s employees.

Interviewee GOV17 indicated that, after the draft Bill had been revised by the Office of the Council of State and submitted to the Parliament, several vested interests had tried to get the threshold requirements for considering a tax crime as a serious offence increased. GOV17 pointed out that higher thresholds could have made “enforcement of the law [difficult]”. Interviewee GOV23 revealed that, during the Bill drafting process, many details including stricter threshold requirements were lobbied against:

[T]here was a meeting to review the final draft Bill before submitting to Parliament at which [stage various] interest groups lobbied … [threatening to] oppose the Bill.

What conforming to internal pressures has highlighted is that internal legitimacy relies upon emergent “bottom up” practices from the public, the military, the government and from lobbying advocates; it suggests that the emergent results for the tax evasion legislation have come “from spatially dispersed, heterogeneous activity by actors with varying kinds and levels of resources” (Lounsbury & Crumley, Citation2007, p. 994). Thus, in this case, internal legitimacy has created support in framing the Thai government’s shaping of strategic direction and decision-making regarding the introduction of the tax evasion legislation.

5.2. Externalising institutional compliance

Although internal legitimacy was influential for the introduction of the new tax legislation, there was also a need for external endorsement (Scott, Citation2001). This required the Thai government to engage with those actors and agencies who could improve their reputation and increase their legitimacy with the introduction of the legislation. Thus, compliance in this context adheres to Oliver’s (Citation1991, p. 152) definition: “conscious obedience to or incorporation of values norms or institutional requirements”.

5.2.1. International cooperation in tackling international tax evasion

Some suggested that the impetus for the new law was international in nature. Interviewees GOV17 and GOV23 noted that a study by the Anti-Money Laundering Office on the National Risk Assessment for Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing (FATF, Citation2018) identified tax evasion as a major contributor to a large percentage of all criminal assets in Thailand. Nine interviewees argued that this new tax evasion legislation was necessary to tackle both domestic and international tax evasion. Furthermore, Thailand, was required to implement the recommendations of the FATF to treat certain tax crimes as criminal offences under its laws relating to anti-money laundering. Interviewees GOV17 and GOV23 also mentioned that the FATF had on-going assessments of (i) the effectiveness of measures initiated by its members to combat money laundering and the financing of terrorism; and (ii) the success of its members in implementing the technical requirements of the FATF Recommendations. These interviewees saw the new legislation as a response to this external pressure.

The legislation sought to ensure that the government’s external legitimacy responded to the scrutiny and testing of these external stakeholders (Drori & Honig, Citation2013). Although Thailand had partly implemented the different requirements proposed by the FATF, there was a concern raised about the effectiveness with which the recommendations of the FATF were being pursued. For example, Interviewee GOV23 stated that there were very few “criminal proceedings initiated against tax evaders” which created the impression internationally that “Thailand [was] not yet achieving all key goals of effectiveness”. Interviewee GOV17 further explained how external pressure was a key factor behind the new law, stating that without the new legislation, there might have been “trouble in implementing the recommendations of the Financial Action Task Force, and [with] international cooperation”.

5.2.2. Signals from national bodies

Interviewees GOV17 and GOV23 emphasised that if Thailand was assessed as having a low level of compliance with the FATF recommendations, the country might have appeared on either the “black” or “dark grey” list of countries. This might have resulted in a reduction in international trade since other countries would have seen Thailand as a nation where there was a high-risk of becoming involved in money laundering transactions or the funding of terrorism. For example, GOV17 suggested that:

If Thailand did not … implement the Anti-Money Laundering and Combating the Financing of Terrorism standard, [it would] have appeared on the list of [high] risk countries. [If this happened], other member countries of the Financial Action Task Force could implement financial retaliatory measures against Thailand. … this might have affected international trade and [resulted in an] investment boycott against Thailand

As an open economy with a reliance on imports and exports, Thailand’s international standing was also important to the government and seen as a key driver behind the introduction of the tax evasion legislation by some of the interviewees. Furthermore, it was key that the Thai government was advocating the “need to do something or be seen to be doing something” (Arshed et al., Citation2014, p. 649) with respect to addressing the concerns raised by the international bodies.

5.3. Micro-political strategizing

The micro-political element, here, is related to individuals’ and smaller groups’ political issues with the introduction of the tax evasion legislation. This occurred where opportunities for public challenges may have been transparent because of turf war, conflicts of interest and grassroots stakeholder interests being restricted (Lazega, Citation1992). This, in turn, could threaten the legislation which was being proposed (Ryan, Citation2000) and, by supressing the voices of those who were opposed to the new law, this added to the legitimacy of the tax evasion legislation which allowed for the creation of legitimacy around the tax evasion legislation to continue. Oliver (Citation1991, p. 153) argues that governments often undertake such tactics which refer to the “accommodation of multiple constituents’ demands in response to institutional pressures and expectations … to achieve parity among or between multiple stakeholders and internal interests”.

5.3.1. Turf war

Several of the interviewees highlighted opposition to the new legislation when it was proposed. For example, Interviewees GOV14, GOV15, GOV17 and GOV23 mentioned that there had been a debate as to which law the proposed legislation would fall under and who would be responsible for its implementation. Before the Bill drafting process began, the Revenue Department and the Anti-Money Laundering Office had agreed that the law should be legislated under the umbrella of the Anti-Money Laundering Law. However, the government opposed this suggestion, arguing that the legal process had to be initiated by the Revenue Department. The government also required the law to be legislated under the Revenue Code – possibly because the Revenue Department might add to the legitimacy of the proposed legislation. For instance, Interviewee GOV14 stated that:

At the first place, the new tax evasion Bill should have been legislated under the Anti-Money Laundering Law. However, due to many political issues arising during the stage of preparing the Bill, this law was finally legislated under the Revenue Code

5.3.2. Conflict of interests

Interviewees argued that opposition to the Bill might have called the legitimacy of the government’s proposals into question. For instance, Interviewee GOV23 mentioned that many elected representatives, “even the President and the Vice-President of the National Legislative Assembly”, were, themselves, members of interest groups that that might be impacted by the legislation.

Interviewee GOV17 agreed, arguing that some elected representatives realised that the law might adversely affect their businesses if thresholds were too low. However, they couched their arguments in terms of Small and Medium-sized Enterprises who play a significant role in driving the Thai economy. As a result, there were compromises made between politicians and the government.

5.3.3. No mobilisation of grassroots stakeholder interests

After the new tax evasion law had been promulgated, nine participants perceived that there was relatively little discussion about the proposed new legislation, especially with the public. If one of the purposes of the new tax law was to raise awareness about the payment of tax among the Thai people, Interviewee GOV23 suggested that it had failed. Although, the Revenue Department publicised this law through seminars with entrepreneurs (GOV2, GOV5, GOV7 and GOV8) and via its website (GOV3), participants suggested that many of the Thai people were unaware of this law. Interviewees GOV14, GOV23 and OS1 explained that there were no public hearings conducted to discuss the new tax evasion law.

Additionally, six interviewees perceived that the new law was unlikely to have an impact on most entrepreneurs since they operated below the thresholds set in the legislation. Furthermore, 12 interviewees revealed that, as far as they were aware, there had been no prosecutions under this law. Also, those participants who worked with the Revenue Department were not aware of any instance whether this law had been enforced in their areas of responsibility.

However, some medium-sized entrepreneurs and large-sized business were concerned about this law. They were afraid that the Revenue Department might use excessive powers in enforcing this legislation as the high threshold meant that it would not apply to many smaller enterprises. Thus, they were worried about being accused of tax fraud and having their properties seized under the Anti-Money Laundering Law. For example, Interviewee GOV7 heard that entrepreneurs involved with precious metals “held [a] meeting … [of their] trade association [where] experts in money laundering were invited to [speak]” (GOV7). Interviewee AF3 noted that there was, also, more concern about this law among tax advisers, commenting that “many tax advisers, … are more afraid of this law and will avoid using hybrid transactions and tax havens” (AF3).

These three themes highlight that the attempts of the Thai government to retain control over the legislation which led them to ensure that political behaviour, for example, influencing, persuading, claiming and negotiating of individuals in and around organisations who seek to pursue their interests (individual or collective, formally legitimate, or boundary pushing) was over-ruled by applying strategies to marginalise those groups that might oppose them (Blazejewski & Becker-Ritterspach, Citation2016). It is predominantly the key actors who make and implement rules and the findings highlight why the legislation was introduced and how the government mobilised its resources of power and legitimacy to ensure that they were successful (Morgan & Kristensen, Citation2006).

6. Discussion and conclusion

This paper set out to explore why tax evasion legislation was introduced in Thailand during 2017. We explored the perceptions about why the government introduced this legislation and identified three themes which helped to understand the Thai government’s motives when introducing the tax evasion legislation.

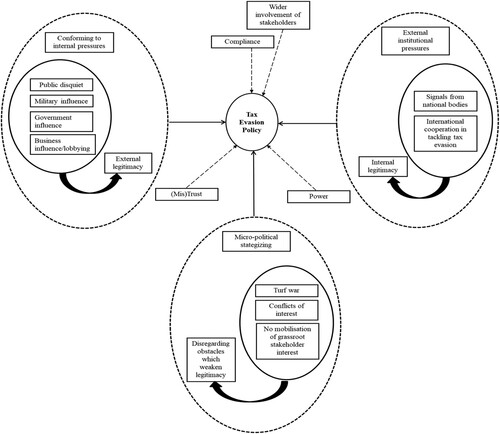

We found that the Thai government adopted the tax evasion legislation because they were: (1) conforming to internal pressures and (2) externalising institutional compliance; in which, (3) they applied micro-political strategizing to ensure the legislation was enacted and implemented. captures the findings and links the relationships between the macro (institution) and micro (actors) levels and the internal and external legitimacy concepts. Four areas of the process highlighted 'missing links’, concerning the understanding of tax evasion legislation in Thailand, are highlighted in which include: the expected levels of compliance (from both the government and the public) in which the perceived legislation and the institution themselves are seen as legitimate (Bello & Matshaba, Citation2020); the willingness to implement the legislation once it had been introduced because if there is willingness this will bolster obedience to the legislation (Sunshine & Tyler, Citation2003); the (mis)trust and lack of information amongst officials within government and those prosecuting the cases; and, the power given to certain officials to ensure the law was upheld. The figure highlights two key elements of why the tax evasion legislation was introduced: external and internal legitimacy based on external and internal pressures.

The external legitimacy highlights that the pressure of external expectations from stakeholders influenced the choice of legitimacy strategies (Scherer et al., Citation2013) as to why the current tax evasion legislation was introduced in Thailand. Thus, one of the main findings from this research is that the Thai government adopted this approach to tackle tax evasion legislation in direct response to concerns about external legitimacy over money laundering and the financing of terrorism. Some of the participants believed that the legislation was required to satisfy the APG’s Terms of Reference and assessments made by the FATF which resonates with the formal institution being faced with external pressures they try to strategically address (Oliver, Citation1991).

Internal pressures also contributed to the introduction of this legislation. Several interviewees expressed the view that the Act was introduced because of pressure placed upon the government by the military. The prominence of the military in the tax reform process is unusual within the current literature, suggesting that tax legislation by the State involves subtler and less coercive notions of power; the possibility of physical coercion or threat was hinted at by some of the interviewees in the passage of the tax evasion legislation in Thailand who placed a good deal of emphasis on the role of the military in ensuring that the government enacted the legislation. The internal legitimacy affected the policy process – the intricacies as to why the tax policy had to be voiced and articulated in an official manner. Furthermore, there was pressure from a previous scandal which concerned the Revenue Department as well as interest groups lobbying for small businesses (where some elected members were, themselves, owners). The Thai government was able to grasp that it needed to respond to such a crisis of public confidence. Specifically, it understood the heightened awareness of risk among the public as a key factor in shaping its response (O’Regan & Killian, Citation2014). To this end, Power (Citation2007) sees risk governance as essentially about the management of public expectations and the production of legitimacy. Hence, one way of tackling this risk and providing reassurances was to introduce the tax evasion legislation.

From our analysis, both external and internal legitimacy were important impetuses for government action in this area. The pressures from both the external and internal environments were intertwined in the process of legitimation with the institution conforming to such pressures (Deephouse, Citation1996; DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983). The external environment played a crucial role in how the Thai government responded to change. The institution was seen to behave in a way which attempted to overcome any potential upheaval and this led them to agree to changes in the tax policy from stakeholders such as the APG. Thus, the Thai government, from an instrumental legitimacy perspective, ensured that they, themselves, the process and the legislation were “judged as legitimate” (Tost, Citation2011, p. 691).

The Thai government expressed an intention to reduce tax evasion by businesses but, given the findings, there was some dispute about how “strict” and “which” businesses the legislation would affect. This suggests that the legislation may not be efficient (in terms of additional tax revenues from lower tax evasion) because of the government’s desire for legitimacy. Furthermore, the introduction of such a change in tax law does not necessarily ensure that the government will take effective enforcement action (Meyer & Rowan, Citation1977). It can be argued that the Thai government introduced the new legislation because of the issues associated with increased legitimacy rather than efficiency. Meyer and Rowan (Citation1977, p. 349) argue that “incorporating externally legitimated formal structures increases the commitment of internal participants [e.g. taxpayers] and external constituents [e.g. APG]”.

Our findings make three contributions to the current tax evasion literature. The first is to provide a more in-depth understanding of the motives of actors at the macro and micro levels for introducing tax evasion legislation. This study returns to the “coalface” of formal institutions (Barley, Citation2008) by drawing attention to actors’ interpretations and agency in tax evasion policy. Their perceptions, motives and actions have been critical in explaining why the Thai government would introduce the tax evasion legislation. This agency explanation contrasts with previous studies that have concentrated on the formal institutional failings and low tax morale, including a perceived lack of tax fairness, corruption and political instability (Williams, Citation2020). Second, the study shows that internal and external legitimacy are required for formal institutions to be effective in formulating and implementing new laws. New legislation on tax evasion in Thailand required the acceptance and support of key external and internal stakeholders. Thus, elite members of different departments of the government and selected entrepreneurs were chosen to validate the new laws (Drori & Honig, Citation2013). The Thai government also needed to maintain and continue to build external legitimacy to secure continued support for their policies and actions (Wanderley et al., Citation2021) even if that meant employing micro-political strategies to “eliminate” challenges created by stakeholders. Finally, our study focusses on the importance of institutional contexts within which these actors operate when pursuing legitimacy for such policy work (Lawrence & Suddaby, Citation2006). This focus complements existing research within the tax literature that pays attention to the processes without locating these in the context in which they occur. Taken together, our contributions can be seen to somewhat respond to Horodnic’s (Citation2018) call for subtler investigations into an area where empirical evidence is difficult to gather. Moreover, by drawing on institutional theory we have explored the macro and micro levels of the study because the actors and interest groups operating at these levels of engagement highlighted their different interests, different sources of power and different audiences to whom formal institutions such as government must articulate their claims for legitimacy (Mulligan & Oats, Citation2016).

Furthermore, our study yields some practical insights that might be leveraged to improve the process whereby tax evasion legislation can be introduced. Firstly, policymakers should draw on the backing of powerful institutions (such as the military in the case of Thailand) for the introductions. They should also exploit any groundswell among the public for the issue of tax evasion to be changed. It would also be worthwhile to compare the role of military with Western countries to understand how the military can play a proactive and strategic role in helping to create legislation. Second, policymakers could consider the implications of pursuing ambitious policies without commensurate resources for tax professionals and others concerned with the implementation of tax evasion legislation. The resources required for effective and efficient policy are fundamental to ensure that both the external and internal legitimacy of the policy are upheld. Thirdly, policymakers may need to rebut challenges to their attempts at tackling tax evasion (Mohammadi Khyareh, Citation2019). This can be done by ensuring the public and key stakeholders are involved in the understanding of the reasons behind the introduction of new legislation by: building credible evidence and fully assessing policy options rather than rushing to legislate, spending or setting ill-considered targets; giving influential and motivated ministers responsibility for priority cross-cutting policy areas; and, involving a range of people in the policymaking process to get the ideas and buy-in from other sectors and stakeholders (Institute for Government, Citation2015). Lastly, government should allow flexibility and transparency when introducing tax evasion policies, as this allows for tax morale and trust to be much more positive in a country (Estrin et al., Citation2013). This can be achieved by holding public officials accountable and fighting corruption; allowing the press and the public to have access to meetings (via records, attendance via online, etc.); making budgets open to public scrutiny and; the laws discussed in a manner that involves a bottom-up approach. This creates flexibility on the processes of such legislations.

We acknowledge the limitations of our findings, and of the methodological approach adopted. The study was based in Thailand; this may have consequences for governments introducing tax policies based elsewhere. For example, governments in the West operate differently and, therefore, organisational culture needs to be considered in future studies undertaken. Fruitful research might, therefore, explore government tax policy formulation and implementation in different countries and contexts and compare their results with the current findings in Thailand. Another possibility is to undertake future studies with a view to collecting data through ethnographic methods rather than in a snapshot of time, to extend the study to longitudinal data collection. Nevertheless, without our study, subsequent investigations will not have a benchmark against which to evaluate their findings.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (28.4 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank the the Editor and the anonymous reviewers for their careful reading of our manuscript and their many insightful comments and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The tax gap is the difference between the amount of revenue actually collected for a tax in respect of a fiscal year and the amount that would have been collected with perfect compliance (OECD, Citation2018).

2 Medina and Schneider (Citation2018, p. 4) define the shadow economy as “all economic activities which are hidden from official authorities for monetary, regulatory, and institutional reasons”.

3 Prior to this, tax evasion was dealt with under the Revenue Code of Thailand, B.E.2481 (A.D.1938) without mentioning tax evasion.

4 For tax evasion to be a serious offence, (i) the tax offence must relate to tax evasion of ten million Baht or more in a tax year, or a fraudulent tax claim of two million Baht or more in a tax year; (ii) the offender, either on their own or with others, has attempted to conceal assessable income for the purpose of committing income tax evasion or tax fraud; and (iii) any properties which relate to this offence are concealed or hidden by the offender for the purpose of preventing the tracing and seizure of these assets.

5 For instance, Sikka (Citation2014) reported that, at that time, the UK tax authority was scrutinising over 40,000 tax avoidance schemes involving in excess of £10bn of tax revenue to decide whether or not they should be legally challenged on the grounds that were unlawful and constituted tax evasion.

6 This approach may have been adopted because the AMLO identified tax evasion as one of the five major crimes which contributed to a large percentage of all criminal assets in Thailand (AMLO, Citation2018). In addition, the switch of the ALMO from the Ministry of Justice to the direct supervision of the Prime Minister may have influenced the decision. Such issues are explored in the current paper.

7 For a comprehensive review of the literature which suggests that some of the predictions of the Allingham and Sandmo (Citation1972) are not supported by empirical evidence, see Freire-Serén and Panadés (Citation2013).

8 This paper recognises the government as the formal institution because it involves key individuals who have substantial and unrivalled power to shape tax policy (Grimm, Citation2006). Furthermore, these formal institutions exert influence through rules and regulations, normative prescriptions and social expectations (Scott, Citation2001).

9 Mulligan and Oats (Citation2016) refer to “in-house” as tax executives from 15 companies from the technology sector in the Silicon Valley. However, this study refers to “in-house” as officials in the Revenue Department, the Department of Special Investigation, the Anti-Money Laundering Office and the Fiscal Policy Office of the Thai government.

10 Analysis of statutory tax rates of other ASEAN countries, the UK and US reveals that the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam currently have the top marginal tax rate for personal income at 35% among those ASEAN countries with Personal Income Tax (KPMG, Citation2019).

11 The quotes in Thai were read by two other Thai nationals fluent in the local language and translations were agreed before being used in this paper.

12 After finalising the transcripts, the views of the respondent in the transcripts were read several times and then summarised. For example, the view that “five interviewees suggested that enactment of this law resulted from a high-profile case of VAT fraud in 2015 which called the legitimacy of the tax system into question” were summarised to the first-order concept which is “A high-profile fraud case in 2015 involving Revenue Department staff”.

13 The main ideas or themes raised from the first-order concepts (i.e., improving the Revenue Department’s efficiency and effectiveness, increasing trust in the tax collection system, as well as being seen to act on tax evasion) were grouped into the second-order themes which is “Government influence”.

14 Zhang et al. (Citation2021) highlight how underpayment of corporate VAT is often ignored by the tax literature noting “that traditional studies “that limit their focus to income tax may have underestimated the magnitude of firms” tax avoidance [and evasion]”. The VAT-fraud case in Thailand which was thought to be a factor behind the legislation would tend to support this view.

References

- Alasfour, F. (2019). Costs of distrust: The virtuous cycle of tax compliance in Jordan. Journal of Business Ethics, 155(1), 243–258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3473-y

- Allingham, M. G., & Sandmo, A. (1972). Income tax evasion: A theoretical analysis. Journal of Public Economics, 1(3-4), 323–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/0047-2727(72)90010-2

- Alm, J. (2021). Tax evasion, technology, and inequality. Economics of Governance, 22(4), 321–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10101-021-00247-w

- Alstadsæter, A., Johannesen, N., & Zucman, G. (2019). Tax evasion and inequality. American Economic Review, 109(6), 2073–2103. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20172043

- Alvesson, M., & Sandberg, J. (2022). Pre-understanding: An interpretation-enhancer and horizon-expander in research. Organization Studies, (3), 395–412https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840621994507

- AMLO (The Anti-Money Laundering Office). (2018). National money laundering and terrorism financing risk assessment. Retrieved November 5, 2018, from http://www.amlo.go.th/amlo-intranet/media/k2/attachments/NRAYSumY2559YEN_7527.pdf

- Andriani, L. (2016). Tax morale and prosocial behaviour: Evidence from a Palestinian survey. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 40(3), 821–841. https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/bev019

- Androniceanu, A., Gherghina, R., & Ciobănaşu, M. (2019). The interdependence between fiscal public policies and tax evasion. Administratie si Management Public, 32, 32–41.

- APG (Asia Pacific Group on Money Laundering). (2017). Anti-Money laundering and counter-terrorist financing measures: Thailand Mutual Evaluation Report December 2017. Retrieved March 25, 2019, from http://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/reports/mer-fsrb/APG-MER-Thailand-2017.pdf

- Arshed, N., Carter, S., & Mason, C. (2014). The ineffectiveness of entrepreneurship policy: Is policy formulation to blame? Small Business Economics, 43(3), 639–659. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-014-9554-8

- Atlı, A. (2010). Societal legitimacy of the military: Turkey and Indonesia in comparative perspective. Turkish Journal of Politics, 1(2), 5. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.460.8452&rep=rep1&type=pdf#page=7

- Bame-Aldred, C. W., Cullen, J. B., Martin, K. D., & Parboteeah, K. P. (2013). National culture and firm-level tax evasion. Journal of Business Research, 66(3), 390–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.08.020

- Barley, S. R. (2008). Coalface institutionalism. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, K. Sahlin, & R. Suddaby (Eds.), The Sage handbook of organizational institutionalism (pp. 491–518). Sage.

- Battilana, J., Leca, B., & Boxenbaum, E. (2009). 2 How actors change institutions: Towards a theory of institutional entrepreneurship. Academy of Management Annals, 3(1), 65–107. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520903053598

- Beck, U. (1992). Risk society: Towards a new modernity. Sage Publications.

- Bello, P. O., & Matshaba, T. D. (2020). What predicts university students’ compliance with the law: Perceived legitimacy or dull compulsion? Cogent Social Sciences, 6(1), 1803466. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2020.1803466

- Benjasak, C., & Bhattarai, K. (2019). General equilibrium impacts of VAT and corporate income tax in Thailand. International Advances in Economic Research, 25(3), 263–276. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11294-019-09742-7

- Besley, T., Jensen, A., & Persson, T. (2014). Norms, enforcement, and tax evasion. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 1–28. http://www.nber.org/papers/w25575

- Bitektine, A. (2011). Toward a theory of social judgments of organizations: The case of legitimacy, reputation, and status. Academy of Management Review, 36(1), 151–179. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2009.0382

- Blazejewski, S., & Becker-Ritterspach, F. A. A. (2016). Theoretical foundations and conceptual definitions. In F. A. A. Becker-Ritterspach, S. Blazejewski, C. Dörrenbächer, & M. Geppert (Eds.), Micropolitics in the multinational corporation: Foundations, applications and new directions (pp. 17–50). Cambridge University Press.

- Boyne, G. A. (2003). Sources of public service improvement: A critical review and research agenda. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 13(3), 367–394. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mug027

- Brink, W. D., & Porcano, T. M. (2016). The impact of culture and economic structure on tax morale and tax evasion: A country-level analysis using SEM. In J. Hasseldine (Ed.), Advances in taxation (pp. 87–123, Vol. 23). Emerald Group Publishing.

- Brinkerhoff, D. W. (2005). Rebuilding governance in failed states and post-conflict societies: Core concepts and cross-cutting themes. Public Administration and Development, 25(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.352

- Burch, P. (2007). Educational policy and practice from the perspective of institutional theory: Crafting a wider lens. Educational Researcher, 36(2), 84–95. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X07299792

- Carpenter, V. L., & Feroz, E. H. (2001). Institutional theory and accounting rule choice: An analysis of four US state governments’ decisions to adopt generally accepted accounting principles. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 26(7-8), 565–596. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0361-3682(00)00038-6

- Chambers, P. (2018). In the land of democratic rollback: Military authoritarianism and monarchical primacy in Thailand. In B. Howe (Ed.), National security, statecentricity, and governance in East Asia (pp. 37–60). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Chan, H. F., Supriyadi, M. W., & Torgler, B. (2018). Trust and tax morale. In E. M. Uslaner (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of social and political trust (pp. 1–71). Oxford University Press.

- Dacin, M. T., Munir, K., & Tracey, P. (2010). Formal dining at Cambridge colleges: Linking ritual performance and institutional maintenance. Academy of Management Journal, 53(6), 1393–1418. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.57318388

- Dahl, R. A. (1998). On democracy. Yale University Press.

- Dallyn, S. (2017). An examination of the political salience of corporate tax avoidance: A case study of the Tax Justice Network. Accounting Forum, 41(4), 336–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accfor.2016.12.002

- De Boyrie, M. E., Pak, S. J., & Zdanowicz, J. S. (2005). Estimating the magnitude of capital flight due to abnormal pricing in international trade: The russia–USA case. Accounting Forum, 29(3), 249–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accfor.2005.03.004

- Deephouse, D. L. (1996). Does isomorphism legitimate? Academy of Management Journal, 39(4), 1024–1039. https://doi.org/10.2307/256722

- Dell’Anno, R. (2009). Tax evasion, tax morale and policy maker’s effectiveness. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 38(6), 988–997. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2009.06.005

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095101

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1991). Introduction. In P. J. DiMaggio, & W. W. Powell (Eds.), The new institutionalism in organizational analysis (pp. 1–38). University of Chicago Press.

- Drori, I., & Honig, B. (2013). A process model of internal and external legitimacy. Organization Studies, 34(3), 345–376. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840612467153

- Eccleston, R. (2006). Confronting the sacred cow: The politics of work-related tax deductions. Australian Tax Forum, 21, 3–15.

- Eisenhardt, K., & Graebner, M. (2007). Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 25–32. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.24160888

- Erserim, A. (2012). The impacts of organizational culture, firm’s characteristics and external environment of firms on management accounting practices: An empirical research on industrial firms in Turkey. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 62, 372–376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.09.059

- Estrin, S., Korosteleva, J., & Mickiewicz, T. (2013). Which institutions encourage entrepreneurial growth aspirations? Journal of Business Venturing, 28(4), 564–580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2012.05.001

- FATF (The Financial Action Task Force). (2018). Anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing measures – Thailand, Mutual Evaluation Report, December 2017. Retrieved October 18, 2018, from http://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/reports/mer-fsrb/APG-MER-Thailand-2017.pdf

- FATF (The Financial Action Task Force). (2020). Consolidated assessment ratings. Retrieved April 24, 2020, from http://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/4th-Round-Ratings.pdf.

- Fogel, K., Hawk, A., Morck, R., & Yeung, B. (2008). Institutional obstacles to entrepreneurship. In N. S. Wadeson, A. Basu, B. Yeung, & M. Casson (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of entrepreneurship (pp. 540–579). Oxford University Press.