ABSTRACT

This article studies the image of political science in Austria by tracing and analysing references to political scientists and their research in parliamentary debates. Since they were first established in Austrian universities in the 1960s, the social sciences and especially political science have been contested and sometimes accused of being forms of political (left-wing) ideology. This politicization has given references to political science a potential rhetorical value in parliamentary debates between oppositional and governmental factions. The parliamentary records of the Austrian Parliament (National Council) were searched for references to political science and several were found from 1966 until 2021. An analysis of these results identified three main rhetorical strategies at work in references to political science in plenary debates. The declining use of these strategies over time indicates a growing acceptance of political science and a positive view of political science expertise. Nevertheless, in recent debates right-wing populist parliamentary members in particular have continued to perpetuate and reinforce a negative image of political science and political scientists.

Introduction

Under the First Austrian Republic (1919–34) social science research flourished, especially in (social democratic) Vienna. However, this development was brought to a sudden end by the forced emigration of most of its protagonists. There was no restoration of social science research after 1945, so that the re-institutionalization of political science started late.Footnote1 In 1963 the Ford Foundation established the non-university Institute of Advanced Studies (Institut für Höhere Studien, IHS), which offered a postgraduate programme in political science and educated the first generations of political scientists in Austria.Footnote2 By the middle of the decade, the leading political parties – the Catholic conservative People’s Party (Österreichische Volkspartei, ÖVP) and the social democratic Socialist Party (Sozialistische Partei Österreichs, SPÖ) – agreed on a national education plan based on social science expertise, which paved the way for the establishment of political science departments at the universities of Salzburg (1969), Vienna (1971), and Innsbruck (1976).

The establishment of political science was accompanied by professional reservations from the law faculties and by ideological suspicions. A historical legacy of the heyday of the social sciences during the First Republic was their unwarranted reputation in right-wing discourse as ‘leftist ideology’ or a ‘Jewish project’. Furthermore, the establishment of political science coincided with the student movement, so that graduates of political science were assumed to be ideologically left-wing.Footnote3 An exemplary expression of these reservations is a policy briefing that advised against introducing political science into universities on the grounds that this kind of social science undermined the state.Footnote4

This article investigates the changing image of political science and asks whether the initial imputation of left-wing ideology is still detectable. The research focus is inspired by Kari Palonen’s investigation of ‘political science as a topic’ in post-war German Bundestag debates.Footnote5 This study traces the references to political science in plenary debates in the Austrian National Council, the first of which was made in 1966 and the latest in July 2021. It follows the thesis that the way in which parliamentarians refer to political science in their statements reflects the public image of political science and, vice versa, that the public image of political science makes it a useful weapon in parliamentary rhetorical strategies.

Firstly, the establishment of political science is contextualised and the initially rather sceptical view of political science in parliamentary debates is highlighted. The second section deals with the methodological issues raised by the analysis of plenary debates. The third section presents our analysis of the parliamentary records, starting with a simple enumeration of references to political science and political scientists over time, before proceeding to a content analysis. Three rhetorical strategies (competence, legitimization and attack) are identified, which are discussed in relation to the government-opposition divide. The final section turns to the changing image of political science as (left-wing) ideology and includes plenary debates on university policies in the survey. In contrast to other strategies, the rhetorical strategy of attack is sometimes linked to a negative stereotype of political scientists and their research. In recent debates, this strategy has typically been adopted in right-wing populist rhetoric, which perpetuates and reinforces a negative image of political science in Austria.

Political science or left-wing ideology?

Social sciences in Austria and the institutionalization of political science

In the early twentieth century, Austria, and especially its capital Vienna, provided a favourable environment for the development of the social sciences.Footnote6 A great deal of pioneering work in the field of social theory and empirical research was conducted in the period before 1934, when the Catholic conservative political forces established an authoritarian regime which banned the Social Democratic Party. In 1938 Austria was annexed by Nazi Germany. Consequently, those social scientists who were deemed to be Social Democrats and/or Jews either fled the country such as Paul F. Lazarsfeld or were killed in NS concentration camps such as Käthe Leichter. In 1945, the political divide between left and right-wing extremes was still a source of distrust between the two major political parties. Under the Allied occupation, however, they took steps to bridge the gap by collaborating and eventually moving ideologically to the centre. By the end of the decade, they had decided to integrate former Nazis into the political system, leading to the founding of a right-wing party, which later became the Austrian Freedom Party (Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs, FPÖ). None of the re-established political parties was interested in the remigration of the Holocaust survivors and intellectuals who had been expelled.Footnote7 In contrast to Germany, Austria was not a focus of the US re-education programme which, among other things, established political science at German universities. Consequently, in Austria, political science has not usually been viewed in terms of an education in democracy.

During the 1960s, however, a number of researchers advocated the establishment of political science at Austrian universities. Heinrich Schneider quotes a memorandum from the Catholic and ÖVP-affiliated Sozialwissenschaftliche Arbeitsgemeinschaft that calls for academic studies of politics and mentions René Marcic, a conservative professor of law at the University of Salzburg as the main promotors of political science.Footnote8 This shows that during the 1960s the need for a modern political science was not felt only by left-wing intellectuals and parties. Indeed, in 1965 Marcic became Austria’s first professor of political science and philosophy of law. This development was possible because Salzburg was a newly founded university, and the law faculty was rather weak in comparison with the influential law faculties at the universities of Graz and Vienna, which hosted the major academic opponents of political science during the 1960s. In defensive response, the law professors at the University of Vienna suggested the limited introduction of political science as a postgraduate diploma for legal studies graduates. This idea anticipated the postgraduate programme in political science at the non-university Institute of Advanced Studies (IHS), which was established by the Ford Foundation in 1963.

The pre-history of the IHS dates back to the late 1950s, when the Ford Foundation sent a delegation to Poland and Yugoslavia in order to recruit talented students and offer them grants to study in the USA. A member of this delegation was Paul F. Lazarsfeld, a Professor of Sociology at Columbia University. He decided to expand this mission to Austria, where he found that there were no young researchers able to meet the Ford Foundation’s standards.Footnote9 His Report on Austria became the basis for the Foundation’s decision to establish a centre for advanced teaching and research in Vienna. Its focus was to be on underrepresented disciplines at Austrian universities, including the empirical study of politics.Footnote10 The study of politics, however, was itself deemed to be a political matter. The Federal Minister of Education, Heinrich Drimmel (ÖVP), was concerned that, since Lazarsfeld had been a well-known social scientist in ‘Red Vienna’ and a member of the Austrian Social Democratic Party in the 1920s, the Institute would be dominated by Social Democrats. Consequently, a second scientific advisor was installed, Oskar Morgenstern, a professor of economics and mathematics at Princeton University, another Austrian emigrant and until 1938 director of the Economic Institute in Vienna. Finally, the IHS’ board of trustees was divided equally between representatives of the ÖVP and the SPÖ, thereby providing a balance between the major political parties.

Nevertheless, political science remained under suspicion as leftist ideology.Footnote11 The social sciences and some branches of the humanities were deemed Weltanschauungsfächer (disciplines that teach a world view). Consequently, a widespread fear of ‘subversive sociology’ and ‘revolutionary political science’ found expression in political debates.Footnote12 In addition to the historical background of the social sciences in the 1920s with their intimate relationship to social democracy, the student revolts of the late 1960s and 1970s fuelled the image of political science as a seedbed of left-wing extremism. One of the scholars at the IHS was Eva Kreisky, who later became research director of the IHS’ Political Science department and in 1995 Professor of Political Theory at the University of Vienna. In an interview she comments on the situation in the early 1970s: ‘Political science at that time was not what one would call presentable, let alone able to give political advice. We were perceived as those who were outside the institutions and who tried to smash the institutions.’Footnote13 This perception of the young students of political science is consistent with the above-mentioned policy briefing which claimed that political science would undermine the state.Footnote14

Reform politics and emerging labour markets for political scientists

The establishment of political science at Austrian universities was not only a response to the Ford Foundation’s Institute of Advanced Studies, but also part of the government’s efforts to strengthen the economy by investment in education. This strategy followed a recommendation by the OECD for coping with the economic downturn of the mid-1960s that led the ÖVP and SPÖ to agree to implement educational reforms drawing on social scientists’ expertise and advice.Footnote15 Hence, by the end of the decade there was a demand for social and political scientists, which became even stronger with the reform policies of the 1970s. Far from educating subversive forces, the IHS played an important role in the government’s reform projects of the 1970s, by providing research into the Austrian health system, agriculture and administrative system, as well as on social inequality and Austria’s role in international relations.Footnote16

Nonetheless, despite the growing demand, political science education has constantly been accused of being mismatched with the labour market. In the first empirical review of the demand for political scientists in 1973, Heinz Fabris et al. complain about the hitherto rather defensive arguments against political science by occupational bodies.Footnote17 An example of this defence was the suggestion by law professors at the University of Vienna that political science should be restricted to postgraduate education. This idea reflected a determination to ensure that the growing demand for political science expertise did not undermine the de-facto monopoly of employment in higher state administration held by legal studies graduates.

The general character of the subject did indeed mean that the first graduates of university studies of political science suffered from a lack of a clear path into employment. This started to change with the introduction of the diploma programme in 1981. In his introductory book from 1989, Hans-Georg Heinrich refers to research on the professional careers of Viennese political science graduates who had found employment as managers, administrative officers, journalists, or in the fields of public relations and social research. Only 15 per cent of all graduates from 1981 to 1989 were working in jobs below their qualification level. Heinrich concludes that the data do not confirm the nightmare scenarios of politicized taxi drivers or a subversive academic proletariat that had been foreseen in the debates on the introduction of the diploma programme. However, he adds that ‘there is still the image of the left-wing political scientist and the easy studies programme which teaches neither useful knowledge nor skills.’Footnote18 The latest tracking of bachelor’s and master’s graduates in political science who have not continued their studies stems from 2019. It shows that almost 50 per cent of the graduates of the University of Vienna had found full employment in Austria within five years, mainly in state administration (18–19 per cent), legal representative bodies or NGOs (12–13 per cent), educational institutions (8–11 per cent), and advertising and market research (5–11 per cent). About 45 per cent were living and/or working abroad. Only a minority were unemployed or had a very low income.Footnote19

These figures support the view that political science today has freed itself from its image as a form of left-wing ideology and that graduates are no longer suspected of planning to subvert authorities and overthrow the state. Consequently, it can be assumed that references to political science in parliamentary debates would have changed their character over time.

Analysing parliamentary debates

Parliament and plenary debate

The research focus is on plenary debates in parliament, which is considered to be a decisive political forum of representative democracy. The parliament claims to represent the people (the demos of democracy) and in so doing, it symbolizes democracy. Referring to Michael Saward’s concept of ‘representative claims’, it is assumed that claim-making in parliament fuels the democratic imaginary, and that democratic representation thus involves a symbolic dimension.Footnote20 Moreover, following a definition by Kari Palonen, parliamentary debate is considered to be a way of doing politics.Footnote21 Consequently, parliamentary politics is not confined to (final) decisions, but involves the process of debate which has its own ramifications. Based on this double conception of parliament as a symbolic centre of representative democracy and a way of doing politics as an adversarial activity, I argue that the analysis of parliamentary debates can provide insights into the current condition of democracy.

Plenary debate is the public and visible part of parliamentary debate. Its symbolic centrality makes it a standard-setting arena for political discourse and what is publicly ‘sayable’.Footnote22 It is a discursive and rhetorical mise-en-scène of political conflict and power constellations. These involve topical controversies, the confrontational structure of government and opposition, and ideological polarizations. Debate in parliament evolves around items on the agenda, such as university policies and the establishment of political science at Austrian universities. They are the typical topics of parliamentary research with a focus on final decisions. The adversarial activity in parliament includes oppositional agenda setting, a key democratic feature, which illustrates that a once-elected government still does not have a monopoly on politics.Footnote23 This oppositional pressure on government comes into focus when parliamentary research explores the process of policy making. In Austrian democracy, agenda-setting has long been regarded as a common activity of the major parties. Hence, putting the establishment of political science on the agenda was a common, albeit controversial effort by representatives of the SPÖ and ÖVP while in government. From 1966 onwards, including during the phase of the establishment of political science, one of these two parties was always in government and the other in opposition.Footnote24 Oppositional agenda-setting with regards to political science included, as shown in the previous section, the topic of a lack of employment opportunities for graduates in Austria.

Doing politics by debate requires rhetorical skills and strategies that facilitate representative claims and accentuate the political profile of speakers and their factions. Plenary debates take place in unequal power constellations, i.e. the government-opposition divide, and parties have different thematic preferences conforming to their world views (left- or right-wing ideologies). Consequently, it is assumed that parliamentarians have chosen different rhetorical strategies according to their faction.Footnote25 References to political science in plenary debate can be part of a diverse range of rhetorical strategies, whose choice, it is assumed, illuminates the image that the speaker has of political science. Hence, the analysis of plenary debates is a way to trace the changing image of political science in public discourse.

Phases of Austrian parliamentarism

According to the hypothesis that the choice of rhetorical strategies in parliamentary debates depends on power constellations, a timeline for the major changes in the government-opposition divide in the Austrian National Council was constructed. It identifies six phases of Austrian parliamentarism, each comprising a different number of legislative periods (LP) ():Footnote26

Phase 1 (1966–86) is characterized by a one-party government and an almost equally strong and coherent opposition. LP XI was governed by the ÖVP and XII to XV by the SPÖ. Legislative period XVI is a coalition government of the SPÖ with 90 out of 183 seats in the National Council and the FPÖ with 12 seats. The one-party opposition (ÖVP) was still a coherent force.

Phase 2 (1987–99) is characterized by a so-called grand coalition government (SPÖ and ÖVP) with a comfortable majority and a fragmented opposition of competing parties. The Green Party (GRÜNE) entered parliament and held between 8 and 13 seats, and from 1994 to 1999 the Liberal Forum (LiF) was represented in parliament with 11 and then 10 seats. After the elections of 1986, the FPÖ left the coalition and started to practice a populist style of oppositional politics,Footnote27 a strategy which resulted in an increasing number of seats, rising from 18 in the general elections of 1986–52 in 1999, the same number as the ÖVP.

Phase 3 (2000–06) is characterized by a novel, though contested two-party coalition of the almost equally strong ÖVP and FPÖ with an opposition of collaborating parties (SPÖ and GRÜNE). In this phase the opposition-government and the ideological divides more or less overlapped. The now co-governing FPÖ split into conflicting groups, provoking early elections in 2002, in which the FPÖ lost votes and won only 18 seats. At the same time the ÖVP won 79 seats (an increase of 27). Although the leading members of the FPÖ remained in the government coalition, the party broke apart. Those in government and their supporters founded the BZÖ (Bündnis Zukunft Österreich), while the other faction retained the FPÖ label and went into opposition.

Phase 4 (2007–17) comprises the legislative periods XXIII to XXV with a coalition between the SPÖ and the ÖVP, which resembles phase 2. However, the coalition is weaker than in phase 2 and the opposition stronger in terms of seats, but disunited in terms of ideology and the number of factions. The Green Party is a consistently strong oppositional faction. The FPÖ, initially weakened by the previous party split, reverted to its oppositional style of right-wing populism and almost doubled its seats in the elections of 2013.Footnote28 At the same time, the BZÖ spin-off was very successful until the elections of 2008 but could not pass the 4 per cent threshold following the death of its chairman.Footnote29 Towards the end of this phase, two further oppositional factions emerged, both sponsored by influential industrialists. Team Stronach (TS) was a right-wing populist spin-off from the ÖVP that won 11 seats in the elections of 2013, but subsequently disappeared. The NEOS, a liberal party, entered parliament with nine mandates in 2013.

Phase 5 (2018–19) indicates a rupture in parliamentary power constellations. It is characterized by a two-party coalition government between the ÖVP and the FPÖ as in phase 3, and a collaborating, but weakened opposition consisting of the SPÖ (52 seats) and the new faction PILZ with 11 mandates.Footnote30 The Green Party failed to pass the 4 per cent threshold. In contrast to phase 3, the governmental faction is stronger (113 seats), but the two parties within it are unequally strong. Although the FPÖ almost reached its historical peak of 1999 (52 seats) and won 51 seats in 2017, the ÖVP won a landslide victory and gained 62 seats. The reason was the new party chairman and his re-branding of the ÖVP as the Neue Volkspartei (New People’s Party) combined with a populist spin, which resulted in a close ideological relation to the FPÖ. However, phase 5 was brought to an early end on 27 May 2019 by a parliamentary vote of no confidence in the Chancellor and was replaced by a government of experts until the early elections on 29 September 2019, which brought the Green Party back into parliament.Footnote31

Phase 6 (since 2020) is the ongoing LP XXVII. In the elections of 2019, the New ÖVP won 71 seats (up 11) and formed a coalition with the re-entered Green Party, while the FPÖ lost 20 seats and went into opposition. Compared to phase 5, the opposition in parliament is stronger and the ideological divide goes against the grain of the government-opposition divide. The last debate included in our sample dates from 7 July 2021.

Table 1. Distribution of seats in the Austrian National Council during each phase by party and between government and opposition. Grey party is in government.

Political science in the national council

Parliamentary Records 1966–2021

The research spans a period of 25 years of Austrian parliamentarism and understands itself as a contribution to digital and conceptual history. In a first step, the digitalized records of plenary debates of the Austrian National Council were scanned for two words or word combinations. These are first, politikwiss* to find all versions of the German words referring to political science and political scientists such as Politikwissenschaft, politikwissenschaftlich in all grammatical variations, and second, politolog* which gives all the results for the Latin-based versions of the same words, for instance, Politologie, politologisch. The parliamentary records include: the plenary debates on bills as well as (written) parliamentary questions; Aktuelle Stunde – a general debate dedicated to a current topic of interest; and question hours – a time slot reserved for questions to members of the government. The very first reference that was found dates to 15 July 1966 and the latest to 7 July 2021. I found 148 words with politikwiss* in 105 different debates including written inquiries, and 146 with politolog* in 100 debates and inquiries were found. Thus, an almost equal distribution between the two terms was found. However, while in the first phase variations of politolog* were more often used (89 compared to 55 politikwiss*), this form of expression almost disappeared from plenary debates in the last two phases (2 compared to 23 politikwiss*). This may be caused by the usual self-designation of political science as Politikwissenschaft.

The topics of the debates are diverse and range from the annual budget, through employment policies to reforms of the electoral system. A majority, however, relate to science and university policies, and especially to the UOG (Universitätsorganisationsgesetz), the law regulating the organization of public universities, which has been the subject of frequent debate in parliament. Until 2002 Austrian universities were under state administration so that the UOG was the basis for the establishment of curricula, departments, and professorships. Consequently, the establishment of political science was a topic of parliamentary debates. Assuming that references to political science are to be expected and are normal in this kind of debate, these were excluded them from further analysis.

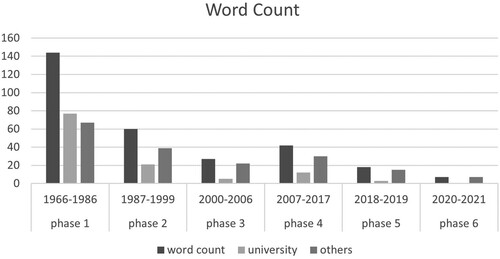

shows the results for all of the phases of Austrian parliamentarism. Our two terms identified an overall total of 291 references. References to political science in debates on research and university policies are indicated as ‘university’ (118), those on other topics as ‘others’ (173).

The word count reaches its peak (144) during the first phase, which includes the debates on the establishment of political science in the universities. The high number of results partly reflects the fact that this period lasted twenty years, while the others were shorter. The annual average of references to political science in phase 1, however, also shows a high number of seven references per year, in contrast to only four or five references per year during the following periods, except phase 5. Phase 5 is a significant exception with an annual average of 12 references, which indicates the highly polarized political constellation at the time. Comparing ‘university’ with ‘others’, I assume that, once the establishment of political science at universities has taken place, political science ceases to be a relevant topic in debates on university policies. Even the fundamental reform of the UOG in 2002 did not result in a higher number of references. On the other hand, the strategic use of references to political science now prevailed. In the following section, the rhetorical strategies will be examined in more detail.

Rhetorical strategies

In a further step, a content analysis was conducted of those debates that do not discuss research or university policies. Each reference to political science was assigned a code indicating its rhetorical use. The code system is based on the hypothesis that references to political science strategically serve three main purposes: first, to indicate specific knowledge and underline the competence of the speaker (‘competence’), second, to support and legitimize the speaker’s point of view (‘legitimization’), and third, to question and de-legitimize other perspectives. Studying the material, I detected all three strategic uses. However, the de-legitimization of political views is often directed against the political opponent in a more fundamental or personal way. This is in line with the findings of Maria Stopfner who conducted a linguistic conversation analysis of Austrian plenary debates.Footnote32 She found that instead of rational deliberation, many disputes in parliament take the form of interpersonal conflicts. To highlight this dimension of personal attack on political opponents, I named the third strategy ‘attack’.

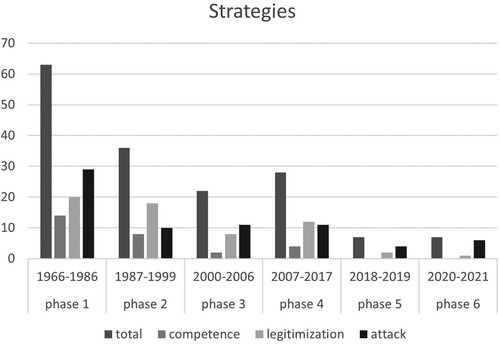

A total of 163 references to political science in plenary debates served strategic purposes and their frequency is constant at a level between three to five references per year. shows their distribution over time.

Strategy 1: Competence

The code ‘competence’ includes occasions when speakers in parliament call themselves political scientists or when they refer to political science research to demonstrate their own expertise and competence in a special field of interest. Parliamentarians often cite definitions taken from political science textbooks. Given the adversarial structure of plenary debates, this strategy can be assessed as neutral, because it neither supports a political point of view nor does it attack an opponent. However, it can be applied to prepare the ground for another strategy (‘legitimization’ or ‘attack’). ‘Competence’ presumes a positive and non-ideological image of political science and political scientists. The following examples illustrate this strategy:

Walter Hauser (ÖVP) states that ‘doctrine, political scientists, and political practice know many different ways to transform voices into mandates’.Footnote33 With this statement, he prepares the ground for discussing the distribution of seats as part of the electoral regulations, which are the topic of the plenary debate. Similarly, Heinz Kapaun (SPÖ) reflects on the changing functions of parliament in a debate on the reform of parliamentary procedures. ‘Modern political science’, he states, ‘defines parliamentary functions fundamentally differently than was once the case. First: The main function of parliament today – according to political scientists – is legislation. […]’Footnote34 This statement is neutral and adequate in terms of the subject matter.

Another way to apply the strategy of competence is to call oneself a political scientist. Friedhelm Frischenschlager (FPÖ), for instance, does this in a debate on a written parliamentary question when he points to a quotation in the text which he appreciates because of his profession as a political scientist.Footnote35 In a more inclusive way, Peter Pilz (GRÜNE) refers to a study by his ‘colleagues Neisser and Wögerbauer [both ÖVP], which was published in the Journal of Political Science.’Footnote36 The term ‘colleague’ can refer to their common profession as members of parliament or to their academic education as political scientists. I suggest that Pilz uses the term in an ambivalent way to include them in the community of social and political scientists. It is likely that this kind of inclusion is meant to turn their expertise as political scientists against them as parliamentarians. This brings us to the grey zones at the margins of this strategy.

Sometimes the strategy of ‘competence’ can hardly be distinguished from the other strategies. Matthias Strolz (NEOS), for instance, gives a definition of a people’s party (Volkspartei) straight from the textbook:

From a political science point of view, a people’s party cannot be seen as an empty activity, of course it must have a capacity to shine, a capacity to integrate, in terms of content, strategy, personnel, and it must renew itself structurally again and again.Footnote37

Another example shows that the strategy of competence can easily be used to prepare an attack: ‘Ladies and gentlemen, I read a lot of political science essays stating that parliament is increasingly pushed aside. Today, these theoretical findings have been appended by a practical example.’Footnote38 Here, Heinrich Neisser (ÖVP) uses his standing and knowledge as a political scientist to reprimand a minister for his late arrival at a parliamentary sitting on the budget debate.

Although some of the examples also indicate other strategies, I claim that ‘competence’ differs in terms of directness. When used as a verbal attack, competence is subtle and ironic rather than harsh and aggressive and, when intending legitimization, competence emphasizes the speaker’s knowledge rather than his or her political demands.

Strategy 2: Legitimization

The code ‘legitimization’ is used to describe statements that refer to political science with the aim of supporting the speaker’s point of view or political demands. Again, the image of political science is positive and political scientists and their studies are treated as neutral elements in an ongoing debate. In contrast to the strategy of competence, legitimization reflects the adversarial situation in parliament. The following examples illustrate this rhetorical strategy.

Rupert Gmoser (SPÖ) claims that his demand for a model of political participation beyond the majority principle is in line with the ideological basis of the ÖVP (the Catholic Social Doctrine): ‘In case you believe this is just a Social Democratic point of view, I have brought an essay by Anton Pelinka. Thus, this comes from Catholic Social Doctrine.’Footnote39 He introduces Pelinka as a professor of political science at the University of Innsbruck. During his speech, Gmoser refers to several political scientists and papers that all serve the purpose of supporting his view of a balanced democratic model, mixing participatory and representative elements. He tries to disconnect participatory democracy from a left-wing ideology by giving it a neutral, academic legitimacy.

A further example shows how the legitimization strategy clearly differs from that of competence. When Wolfgang Gerstl (ÖVP) cites the political scientist Hubert Sickinger, a well-known specialist in political party funding and corruption, he does not claim to be competent, instead he uses Sickinger’s competence to legitimate a technical measure relating to party donations. This measure had been proposed by Sebastian Kurz, the then leader of the ÖVP. Gerstl claims that Sickinger had called it ‘prudential and exemplary’.Footnote40 In this way, Gerstl supports his party’s proposal and, furthermore, presents his party leader as one who fights corruption.Footnote41 Against the backdrop of public debates on illegal party donations to Kurz and the New ÖVP during the general election campaign of 2017, this interpretation of political prudence is rather provocative. However, the aim here is to legitimate the speaker’s own point of view, not to attack opponents.

Sometimes the disputatious intent is disguised. In a budget debate in 1990, for instance, Herbert Fux (GRÜNE) calls for a fundamental reform of parliament and claims that this reform is necessitated by the fact that parliament is not able to retain its leadership position in the face of the institutions of social partnership. He adds: ‘These findings on the state of parliamentary democracy in Austria are undisputed among political scientists.’Footnote42 This remark legitimates his demand for a fundamental parliamentary reform. However, the social partners in Austria are traditionally constituted by labour and trade organizations, which have close relations to the SPÖ and ÖVP respectively. As a member of an oppositional party that is hardly represented in the social partnership institutions, Fux’ call for a parliamentary reform is, at the same time, a critique of the major parties.

The final example is taken from a debate on a referendum in 2000 that was announced but never held, in which the government planned to consult the people by asking if the EU member states should end their ‘political sanctions’ against Austria. These so-called ‘sanctions’ consisted of the refusal of all forms of diplomatic courtesy to members of the Austrian government by other EU member states and their mainly social democratic governments. This was an answer to the ÖVP’s coalition with the right-wing populist and allegedly fascist FPÖ. In the plenary debate on the statement of the Chancellor and Vice-Chancellor announcing their withdrawal of the referendum plan, Alfred Gusenbauer, the leader of the oppositional SPÖ, comments:

According to many legal experts, constitutional lawyers, political scientists, and others, the referendum, promised by the federal government and fortunately not held, would have been an abuse of a tool of direct democracy.Footnote43

In conclusion, legitimization is a way of referring to political science in a controversy in a plenary debate with the intention ot supporting a speaker’s view or claim. Due to the adversarial setting, it sometimes effects a subtle attack, but above all it emphasizes the speaker’s own demands. The reference to political science serves to give the speaker’s position a patina of indisputable truth.

Strategy 3: Attack

The code ‘attack’ is used to indicate statements in plenary debates that serve the purpose of delegitimizing political adversaries and their claims or ideology. As mentioned above, this rhetorical strategy sometimes targets the opponent personally and it often concerns questions of principle, thus challenging the ideological basis of the party under attack. This is the reason why statements that indicate an attack seldom relate to the topic of the plenary debate. They are especially frequent in the annual budget debates, but debates on electoral or constitutional reforms also give parliamentarians the opportunity to present their world view and attack others. Although used to attack, the image of political science is usually positive.

An example is a speech by Jakob Auer (ÖVP), who uses a study by the political scientist Sickinger to attack the SPÖ, insinuating that the Social Democratic Party has obtained an undue amount of funding. ‘If the figures given by colleague Sickinger, the political scientist, are correct, you take in seven million euros party funding – in Vienna alone! I do not want to know how much this is for the whole of Austria.’Footnote44 While Auer attacks the SPÖ as an organization, Ewald Stadler (FPÖ) uses a brief reference to political science to challenge the ÖVP via a personal attack on a party member. He talks of hypocrisy and calls it ‘Casinerism’ (in German: Casinertum), claiming that this was a concept of political science, meaning to preach water while drinking wine.Footnote45 He goes on to attack a member of the ÖVP faction, Walter Schwimmer, accusing him of drinking a great deal of wine. Stadler concludes: ‘This is the problem of the Austrian People’s Party, ladies and gentlemen! The Schwimmers are the problem.’Footnote46 In this example a word is introduced, or better invented, as a terminus technicus of political science to give the attack the semblance of a scientific justification. However, its aggressive tone is evident. Nevertheless, political science is still treated as neutral and objective.

The strategy of citing the work of a political scientist can be turned against the author. Heinrich Neisser (ÖVP), for instance, does this in an ironical way, when he mentions a previous publication by the young political scientist and then minister of defence, Frischenschlager (FPÖ). He uses the citation to criticize the FPÖ for not being liberal, despite the party’s name. Neisser argues that Frischenschlager in his professional role as a political scientist had to concede that the term ‘liberal’ does not appear in any of the FPÖ’s party programmes, nor is the FPÖ usually defined as a liberal party.Footnote47 Actually, this is a double attack, first against the FPÖ for not being ideologically liberal, and second against the SPÖ, which has formed a coalition government with the FPÖ, claiming that it was a coalition with the liberals in the FPÖ, not with the German nationalists and Nazis. By claiming that there are no liberals in the FPÖ, Neisser accuses the SPÖ of endangering democracy.

This coalition broke apart in 1986, when Jörg Haider became party leader, indicating an ideological turn to the right and towards the German nationalist party faction. Consequently, Severin Renolder (GRÜNE), launched a much harsher attack in 1990:

There is a broad discussion in political science about the meaning of the right-extreme, right-radical, right-wing, Nazi and National Socialist resurgence. All of these concepts, which have been scrutinized by German political scientists, can be found in the utterances made in the various committees of the Freedom Party, ranging from right-wing to right-extreme.Footnote48

Strategies in the government-opposition divide

Rhetorical strategies are applied in plenary debates and thus in the adversarial setting of the government-opposition divide. While the strategy of competence is neutral in this environment because it emphasizes the speaker and his/her education and interests, the strategies of legitimization and attack reflect the adversarial situation in parliament. Therefore, it is expected that these strategies differ according to the speaker’s affiliation to an oppositional or a governmental faction. The initial assumption is that the strategy of legitimization is likely to be mainly a government strategy because most of the legal initiatives are proposed by the ministries. Hence, it is the task of the governmental factions in parliament to defend and legitimize the government’s proposals. On the other hand, it might be expected that members of oppositional factions to apply the strategy of attack to criticize the government and its proposals.

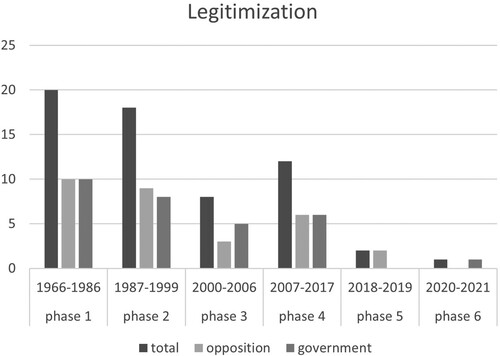

Surprisingly, it was discovered that the use of the strategy of legitimization only weakly reflects the government-opposition divide (). In fact, most of the time it is equally applied by members of governmental and oppositional factions. The slightly imbalanced exceptions are phase 3 and the last two phases, 5 and 6. While phase 3 (ÖVP/FPÖ coalition) and phase 6 (ÖVP/GRÜNE coalition) meet the initial assumption that governmental factions feel a need to legitimize their proposals, in phase 5 (ÖVP/FPÖ coalition) the governmental factions did not resort to a single legitimizing reference to political science. Although the total number of strategies is extremely low in phase 5, this imbalance might indicate a populist attitude on the part of the government.

Figure 3. Strategy of legitimization applied by members of oppositional vs. governmental factions during the phases of Austrian parliamentarism.

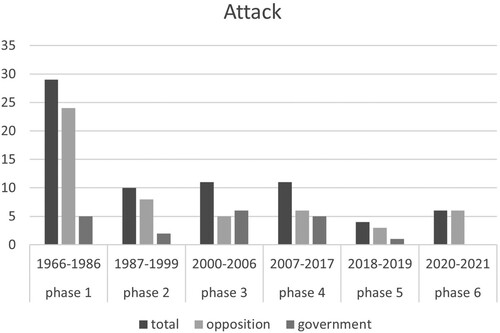

During almost all phases of Austrian parliamentarism the strategy of attack has mostly been applied by oppositional factions, in line with our initial assumption (). However, phase 3 (ÖVP/FPÖ coalition) and phase 4 (SPÖ/ÖVP coalition) are exceptions. Although the total number is again low, the use of the strategies is almost balanced. With regard to phase 3, it is suggested that the slight imbalance in favour of the governmental faction is due to disputes over the so-called EU sanctions.

Figure 4. Strategy of attack applied by members of oppositional vs. governmental factions during the phases of Austrian parliamentarism.

Strategies of legitimization and attack might be expected to reflect the government-opposition divide. However, this does not always hold true for the strategies referring to political science that are the subject of this study. Overall, use of the strategy of legitimization is rather balanced. Moreover, while the strategy of attack was used predominantly as an oppositional means, between 2000 and 2017 its use too was almost balanced. These findings resulted in taking another look at the ideological divide and the image of political science as a form of left-wing ideology.

The changing image of political science

Colouring political scientists in rhetorical strategies

In all the examples of rhetorical strategies given in the previous sections, political scientists and their findings are deemed to be reliable, because they confirm the speaker’s point of view. In that respect, political science enjoys a good reputation. However, the image of political science has been contested and research findings have been suspected of partisanship. A frequent practice in plenary debates that expresses this suspicion is to associate political scientists with a political party and its ideological worldview. While this political ‘colouring’ can serve the strategy of legitimization, it is more commonly used to launch an attack.

During the first phase (1966–86), the colouring of political scientists was a common practice and it sometimes served the strategy of legitimization on both sides of the government-opposition divide. Peter Schieder (SPÖ), a member of the governing faction, for instance, proposes to the parliamentary group leader of the ÖVP, Alois Mock, to consult ‘his own’ political scientists in order to achieve a fuller understanding of the topic.Footnote50 Herbert Kohlmayer (ÖVP) refers to an article by Norbert Leser and introduces Leser as a ‘socialist political scientist’, hence, ideologically from the opposing faction.Footnote51 His aim is to legitimize his point of view and obtain the SPÖ’s approval. In a similar vein, Josef Meisinger (FPÖ) cites Leser to support his demand for the Chancellor to resign.Footnote52 Kohlmayer and Meisinger are from oppositional factions and use Leser’s Social Democratic background to legitimize their own demands vis-à-vis the Social Democratic government. However, Meisinger’s request already shows that the colouring of political scientists can easily turn into an attack. Karl Blecha (SPÖ), for example, refers to a paper by a ‘young ÖVP political scientist’ that states that the ÖVP must accept being only a middle-ranking party.Footnote53 In this way, Blecha tries to delegitimize the ÖVP and its political influence.

Since the beginning of phase 2 in 1986, the colouring of political scientists has exclusively served the strategy of attack. Helene Partik-Pablé (FPÖ), for instance, criticizes the fact that the political scientist Pelinka, whom she associates with the SPÖ, was going to teach at the newly founded Security Academy; Jörg Haider (FPÖ) cries out that this is ‘brainwashing’ and Partik-Pablé affirms his heckle.Footnote54 Although the statement starts of sounding like a legitimate criticism, the reference to brainwashing turns it into a crude attack. It is an attack by an oppositional faction against the government, which is ideologically directed against the left-wing part of the coalition between the SPÖ and ÖVP.

The research findings suggest that the colouring of political scientists has ceased to function in strategies of legitimization and is now exclusively a tool for attack. Furthermore, it damages the image of political science as a provider of objective and reliable expertise.

Reflections on political science in plenary debates on university policies

In order better to understand the changing image of political science it is worth taking another look at the plenary debates on university policies. In the first analytical stage, such debates were excluded from the corpus, because it was not expected to find any strategic use of political science in these debates. This assumption proved correct for most of the references in the stenographic protocols, which simply mention political science as one of the disciplines at issue. However, it was also discovered that debates on university and research policies set the scene for recurring reflections on the status of political science in Austria.

Some of these debates are linked to reservations about the establishment of political science in the universities related to concerns about graduate employability. Johanna Bayer (ÖVP), for instance, calls for estimates of the ‘actual need for political scientists in five or ten years’.Footnote55 Such concerns about employability do not necessarily involve a rejection of political science as such, instead they may relate to demands for the recognition of the relevant university degrees for admission to employment in public administration or education. I observed such concerns especially during the first period under scrutiny. However, over time, concerns regarding the employability of political science graduates give way to a strategy of rejection and delegitimization.

During the second phase (1986–99) which witnessed the first generations of graduates with political science degrees,Footnote56 some members of parliament take debates on university and research policies as an opportunity to reflect on the long and difficult road to the institutionalization of political science and its precarious status. Irmtraut Karlsson (SPÖ), for instance, reminds the audience that the IHS, not the universities, invited Paul Lazarsfeld as guest lecturer, and criticizes the universities’ resistance to progressive social sciences.Footnote57 Johann Stippel (SPÖ) regrets that political science is still neglected in Austria.Footnote58

Others use these debates to insinuate that studying political science is an easy way to get a university degree, leading to a rising number of lazy students. Michael Krüger (FPÖ), for example, wants to reduce the number of political science students by linking grants with grades. He refers to Professor Helmut Kramer, who claims that introductory lectures cannot be given anymore.Footnote59 However, the problem Kramer was addressing here was the unbalanced staff-student ratio in political science, in response to which he advocated an increase in the number of lecturers, not a reduction in the number of students.

The negative stereotype is also challenged. Dieter Brosz (GRÜNE), himself a political science graduate, criticizes the ideal of finishing one’s studies within four years and claims that those of his fellow students who completed their studies early did not know what to do next.Footnote60 In his view, the easy way to get a degree is a bad way to start a professional career. Although Brosz argues against the stereotype of the lazy political science student, he affirms the stereotype of the difficult labour market for graduates.

In short, when parliamentarians confirm the negative status of political science in Austria, they tend to repeat certain stereotypes, such as political science being an easy way to obtain a university degree, the lazy student and low graduate employability. However, in contrast to references to political science in rhetorical strategies of competence, legitimization, and attack, I found that reflections on the status of political science in debates on university policies and research show a clear ideological divide. While members of parliament affiliated to left-wing parties and some moderate conservative parliamentarians regret the negative image of political science, members of right-wing parties tend to confirm the negative stereotype. I suggest that this right-wing stereotyping echoes the initial suspicion of political science as left-wing ideology.Footnote61

Political Science in right-wing populist rhetorical strategies of attack

In the previous section, it was found that negative stereotyping of political science in debates on university policies is primarily practiced by right-wing parliamentarians. In this section, references to political science used as rhetorical strategies of attack based on these negative stereotypes are examined. The focus of this section is on recent plenary debates, i.e. phases five and six starting in 2018, when the right-wing populist FPÖ was in government with the New ÖVP, which also applied right-wing populist strategies and promised to stop (illegal) immigration.Footnote62

During the most recent phases a total of 10 attacks that refer to political science was found. All the parliamentarians who made them were in opposition, because from June 2019 until January 2020 an experts’ government had replaced the ÖVP/FPÖ coalition following a vote of no confidence in the Chancellor. In phase 5, while the ÖVP and FPÖ were in government, there were two attacks, one by a member of PILZ and one by a member of the SPÖ, both referring to political scientists and their research to support their criticism of the government. Hence, these rather left-wing parliamentarians refer to political science as an objective provider of knowledge. Under the government of experts there were two attacks, one by a member of the ÖVP and one by a member of the FPÖ. Both had been in government before and both relied on a negative stereotype of political science. Finally, I found three attacks referring to political science after January 2020, when the ÖVP was in government again in a coalition with the GRÜNE party. Two of the attacks were uttered by members of the FPÖ and one by a member of NEOS. All of them suggest a negative image of political science.

A typical prejudice resulting from the notion of political science as an easy way to get a university degree is the assumption that political scientists lack the necessary skills for employment in state administration. This is the basis for Michaela Steinacker’s (ÖVP) attack against the SPÖ, when she criticizes the attempt of the former minister of defence to reverse the purchase of fighter jets, by emphasizing that the minister was a political scientist.Footnote63 She does not explain this in detail. Hence, she obviously relies on a tacit agreement that a political scientist is not qualified to fill the position of a minister of defence. Gerald Loacker (NEOS) reproduces this negative attitude when he criticizes a personnel decision by a provincial governor from the ÖVP. ‘Although she has studied political science and has no leadership experience, she is now allowed to lead a legal department with 61 people.’Footnote64 Again, the insinuated bad qualification seems to be self-evident, since Loacker does not add any further explanation. Moreover, he does not need to prove the alleged lack of leadership, because a political scientist supervising legal practitioners seems to be sufficiently scandalous in itself.

The notion of doing political science as an easy way to obtain a university degree does not only reflect the professional snobbery of lawyers, but can also be linked to right-wing ideological views. The negative stereotype is used by Walter Rosenkranz (FPÖ) and others in a written parliamentary question concerning Turkish bachelor degree students of political science at the University of Vienna.Footnote65 They ignore the international university landscape and assume a lack of German language skills in order to fuel popular resentment against (Muslim) migrants. The FPÖ strategy of combining anti-Muslim ideology with negative stereotyping of political science is also practiced by Axel Kassegger (FPÖ) when he expresses his concerns about a political scientist studying Islamophobia at the University of Salzburg.Footnote66

Almost all attacks by FPÖ parliamentarians imply an ideological divide and place political scientists and their research on the left, and thus hostile, side. Moreover, they use references to political science to promote a populist notion of an elite working against the people. This populist strategy is employed by Gerhard Deimek (FPÖ) when he criticises a political elite of alleged self-proclaimed experts: ‘In politics we have wonderful political scientists, lawyers, we have journalists and everything possible, who explain to us ex cathedra, so perhaps with infallibility, in what way the economy has to work.’Footnote67 When he comments on measures against climate change, Deimek makes it clear that, for him, political scientists are part of a left-wing political elite that neglects the people’s needs: ‘If political scientists from the Green direction, if sociologists and functionaries of the Young ÖVP tell me, then I know that the worst is to come.’Footnote68 Deimek insinuates that those political scientists who comment on climate change and propose measures are affiliated to the Green party, which is coded ‘left’ in FPÖ discourse, and concludes that their suggestions negatively affect the people by ‘making their lives more difficult’. In fact, he replaces the strategy of colouring political scientists with a strategy of colouring certain fields of political science research.Footnote69

In sum, it is concluded that Deimek reproduces the right-wing populist rhetoric of the FPÖ in parliament. With reference to political science, he combines the lack of competence trope with the strategy of colouring political science research and uses the negative stereotype to construct a political elite that is hostile to the people.

Conclusion

This research traced the references to political science in plenary debates of the Austrian National Council and asked if the initial image of political science as a form of left-wing ideology still prevails. It found that some references simply discuss university policies and the establishment of political science departments and curricula. Others, however, refer to political scientists and their research in a strategic way. The strategy of competence highlights the speaker’s knowledge in a neutral way, while the strategies of legitimization and attack reflect the adversarial setting of the parliament. While I found that these strategies did not reflect the government-opposition divide in the Austrian parliament, I also learnt that political scientists and their expertise seem to enjoy a good reputation there.

These findings change when focussing the ideological divide in parliament. While the practice of ‘colouring’ political scientists has almost disappeared, some types of negative stereotyping of political science still exist. The tropes of the easy way to obtain a university degree, the lazy student, and the incompetent graduate of political science are frequently applied in rhetorical strategies of attack. Moreover, the strategy of colouring political scientists has been replaced to some extent by a strategy of colouring certain fields of research in political science, such as research into climate change or anti-Muslim racism. In recent debates these strategies are also combined with right-wing populist rhetoric, where they serve to construct a political left-wing elite that works against the people. At the same time, they also serve to perpetuate the otherwise obsolete image of political science as a form of left-wing ideology.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Marion Löffler

Marion Löffler, Dr. Mag. PD, is a researcher and lecturer at the University of Vienna. She is Aigner-Rollett Visiting Professor at the department of public law at the University of Graz, and was visiting professor for gender and politics at the department of political science at the University of Vienna, and assistant Visiting Professor at the Austrian Studies Center at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. Her research focus is on contemporary political theories, democracy and parliamentarism, political masculinities and right-wing populism. Recent publication: ‘What parliamentary rhetoric tells us about changing democratic culture: the case of antisemitism in Austrian parliamentary debate as a threat to democracy’, co-authored with Karin Bischof, Redescription, forthcoming.

Notes

1 H.-G.Heinrich, Einführung in die Politikwissenschaft (Vienna & Cologne, 1989), pp. 48–51. W. Hummer, Politikwissenschaft in Österreich unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Europapolitik. Institutionelle und materielle Rahmenbedingungen (Innsbruck, Vienna & Bozen, 2015), pp. 109–88; T. Kliment, ‘Politikwissenschaft in Österreich. Zur Geschichte und Institutionalisierung’, (Diploma Thesis, University of Vienna, 1992); H. Sickinger, ‘Die Entwicklung der österreichischen Politikwissenschaft’, in H. Kramer (ed.), Demokratie und Kritik – 40 Jahre Politikwissenschaft in Österreich (Frankfurt/Main et al., 2004), pp. 27–69.

2 Hummer, Politikwissenschaft in Österreich, p. 115; Sickinger, Entwicklung der österreichischen Politikwissenschaft, pp. 34–39.

3 Sickinger, Entwicklung der österreichischen Politikwissenschaft, p. 49.

4 In 1969 the University of Vienna set up a committee lead by Professor Berthold Sutter from the University of Graz, who finally wrote the policy brief in question without ever convening the committee, Hummer, Politikwissenschaft, p. 127. In the history of political science, this report has been called ‘the ironic founding document of Austrian Political Science’, T. König, & T. Ehs, ‘Wissenschaft von der Politik vor der Politikwissenschaft? ’ Österreichische Zeitschrift für Politikwissenschaft 41, (2012), pp. 211–27, p. 212.

5 K. Palonen, ‘Political science as a topic in post-war German Bundestag debates’, History of European Ideas 46, (2020), pp. 360–73.

6 Sickinger, Entwicklung der österreichischen Politikwissenschaft, pp. 28–9.

7 Christian Fleck coined the term ‘autochtonous provincialisation’ to criticise the self-imposed isolation and sterility of intellectual and academic life in the early years of the Second Republic, C. Fleck, ‘Autochthone Provinzialisierung. Universität und Wissenschaftspolitik nach dem Ende der nationalsozialistischen Herrschaft in Österreich’, Österreichische Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaft 7, (1996), pp. 67–92.

8 Interview with Heinrich Schneider, in Kliment, Politikwissenschaft in Österreich, pp. 119–34, p. 122.

9 Lazarsfeld cited by C. Fleck, ‘Wie Neues nicht entsteht. Die Gründung des Instituts für Höhere Studien in Wien durch Ex-Österreicher und die Ford Foundation’, Österreichische Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaften, 11 (2000), pp. 129–78, p. 133.

10 Fleck, ‘Wie Neues nicht entsteht. Die Gründung des Instituts für Höhere Studien in Wien durch Ex-Österreicher und die Ford Foundation’pp. 139ff.

11 This is similar to Germany and unlike Great Britain (see Kari Palonen’s article in this special issue).

12 H. Kramer, ‘Wie Neues doch entstanden ist. Zur Gründung und zu den ersten Jahren des Instituts für Höhere Studien in Wien’, Österreichische Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaften, 13(3) (2002), pp. 110–32, p. 113.

13 E. Kreisky, & S. Hamann, ‘Der doppelte Blick’, in H. Kramer (ed.), Demokratie und Kritik – 40 Jahre Politikwissenschaft in Österreich. (Frankfurt/Main, 2004), pp. 11–23, p. 13.

14 See footnote 4.

15 Heinrich, Einführung in die Politikwissenschaft, p. 49

16 Kramer, ‘Wie Neues doch entsteht’, p. 123.

17 H. Fabris, G. Heinrich, H. Kramer, P. Kreisk, & E. Schmidt, ‘Zum Politologenbedarf in Österreich’, Österreichische Zeitschrift für Politikwissenschaft, 2, (1973), pp. 419–52, p. 419.

18 Heinrich, Einführung in die Politikwissenschaft, p. 119.

19 The so-called AbsolventInnen-Tracking is available on the intranet pages of the University of Vienna, https://politikwissenschaft.univie.ac.at/studium/informationen-fuer-lehrende/informationen/#c120267

20 M. Saward, ‘The Representative Claim’, Contemporary Political Theory, 5 (2006), pp. 297–318. For the dimension of symbolic representation see P. Diehl, Das Symbolische, das Imaginäre und die Demokratie (Baden-Baden, 2015).

21 K. Palonen, From Oratory to Debate: Parliamentarisation of Deliberative Rhetoric in Westminster (Baden-Baden, 2016)

22 K. Bischof, & C. Ilie, ‘Democracy and Discriminatory Strategies in Parliamentary Discourse. Editorial’, Journal of Language & Politics 17, (2018), pp. 585–93.

23 M. Löffler, & K. Palonen, ‘Editorial’, Parliaments, Estates & Representation 38, (2018), pp. 1–5, p. 3.

24 For details refer to the following section on the periods of Austrian parliamentarism.

25 For an exemplary analysis of rhetorical strategies see K. Bischof, & M. Löffler, ‘Antisemitismus als politische Strategie. Plenumsdebatten im österreichischen Nationalrat nach 1945’, in C. Hainzl, & M. Grimm, (eds) Antisemitismus in Österreich nach 1945 (Berlin & Leipzig, 2022), pp. 43–61.

26 The data is taken from the website of the Austrian Parliament: https://www.parlament.gv.at/WWER/NR/MandateNr1945/ (last download 02.02.2022).

27 K.R. Luther, ‘Austria: A Democracy under Threat from the Freedom Party?’ Parliamentary Affairs 53, (2000), pp. 426–42.

28 For the difference between oppositional and governmental styles of populism see M. Löffler, ‘Populist attraction: the symbolic uses of masculinities in the Austrian general election campaign 2017’, NORMA 15, (2020), pp. 10–25.

29 Jörg Haider, the former FPÖ and then BZÖ leader, died in a car accident on 11 October 2008 only a few days after the general elections which were held on 28 September.

30 Named after Peter Pilz, a former member of the Green party, who founded his own electoral party in the wake of internal disputes.

31 For details see Löffler, ‘Populist Attraction’, p. 10–11.

32 M. Stopfner, Streitkultur im Parlament: linguistische Analyse der Zwischenrufe im österreichischen Nationalrat (Tübingen, 2013).

33 Speech by Dr. Walter Hauser, ÖVP, 26–27 November 1970, own translation.

34 Speech by Dr. Heinz Kapaun, SPÖ, 26 June 1986.

35 Speech by Dr. Friedhelm Frischenschlager, FPÖ, 10 March 1982.

36 Speech by Peter Pilz, Grüne, 5 April 1995

37 Speech by Mag. Dr. Matthias Strolz, NEOS, 11 February 2014.

38 Speech by Dr. Heinrich Neisser, ÖVP, 4 December 1975.

39 Speech by DDr. Rupert Gmoser, SPÖ, 7 October 1982’.

40 Speech by Mag. Wolfgang Gerstl, ÖVP, 20 September 2017.

41 Ironically, Kurz himself had to resign from government after public prosecutors filed corruption charges against him and his team on 9 October 2021.

42 Speech by Herbert Fux, Grüne, 29 November 1989.

43 Speech by Dr. Alfred Gusenbauer, SPÖ, 20 September 2000.

44 Speech by Jakob Auer, ÖVP, 20 October 2010.

45 Actually, the word ‘Casinertum’ does not exist, and I suppose that it was invented by Stadler to make his claim.

46 Speech by Mag. Johann Ewald Stadler, FPÖ, 12 May 1998.

47 Speech by Dr. Heinrich Neisser, ÖVP, 1 June 1983; Liberal in German is ‘freiheitlich’ and thus stands for the F in FPÖ.

48 Speech by DDr. Severin Renolder, Grüne, 26.-27 February 1992.

49 Speech by Dr. Andreas Khol, ÖVP, 13 October1995.

50 Speech by Peter Schieder, SPÖ, 17 September 1984.

51 Speech by Dr. Herbert Kohlmayer, ÖVP, 29 June 1982.

52 Speech by Josef Meisinger, FPÖ, 22 November 1994.

53 Speech by Karl Blecha, SPÖ, 6 November 1979.

54 Speech by Dr. Helene Partik-Pablé, FPÖ, 14 March 1996.

55 Speech by Dipl.-Ing. Dr. Johanna Bayer, ÖVP, 30 June 1971.

56 Diploma studies in political science were first introduced in 1980, and the first graduates left university in 1984. Before 1980, political science had been organized according to the so-called Rigorosenordnung, i.e. as part of exams in another field of studies such as economy or law, Sickinger, Die Entwicklung der österreichischen Politikwissenschaft, p. 53.

57 Speech by Dr. Irmtraut Karlsson, SPÖ, 20–21 September 1995.

58 Speech by Dr. Johann Stippel, SPÖ, 20–21 September 1995.

59 Speech by Dr. Michael Krüger, FPÖ, 28 June 1996. Helmut Kramer was Professor of International Politics at the University of Vienna from 1981 to 2006.

60 Speech by Dieter Brosz, GRÜNE, 11 May 2001.

61 See Kari Palonen’s argument on Germany in the 1970s in his contribution to this special issue.

62 R. Wodak, ‘Vom Rand in die Mitte – “Schamlose Normalisierung,”’ Politische Vierteljahresschrift, 59, (2018), pp. 323–35; see also Löffler, ‘Populist Attraction.’

63 Speech by Mag. Michaels Steinacker, ÖVP, 26 September 2019.

64 Speech by Mag. Gerald Loacker, NEOS, 7 July 2021. Loacker studied law at the University of Vienna.

65 Written question by Dr. Walter Rosenkranz et al. to the Federal Minister of Science, Research, and Economy, 4524/J, 14 April 2015, XXV LP.

66 Speech by MMMag. Dr. Axel Kassegger (FPÖ), 17 November 2020. The political scientist in question had come into the frame in the course of criminal investigations relating to an Islamist terrorist attack in Vienna 2020. However, the investigations against him and others finally turned out to be a miscarriage of justice.

67 Speech by Dipl.-Ing. Gerhard Deimek, FPÖ, 19 November 2019.

68 Speech by Dipl.-Ing. Gerhard Deimek, FPÖ, 21 April 2021. The Young ÖVP is the youth organization of the New ÖVP which, after pushing FPÖ out of government, has also been on the FPÖ’s list of enemies.

69 Especially, but not solely, members of the FPÖ identify some fields of research with hostile (left-wing) ideology. Examples are: studies on climate change, gender-specific and intimate partner violence, right-wing extremism, anti-Semitism, and anti-Muslim racism.