Abstract

In May 2020, when Rio Tinto destroyed ancient rockshelters in Western Australia to expand an iron ore mine, public outcry triggered a parliamentary inquiry. The value and effect of public sector inquiries have been debated for over a century. While the Juukan Gorge inquiry overlooked some important issues, it succeeded in illuminating critical flaws in company, regulatory and administrative systems that trade on injustice. These issues have not been altogether neglected by past state and federal governments, but previous inquiries failed to drive meaningful reform. We conclude that while systemic change seems improbable, the evolving political milieu in Australia may offer prospects for industry change.

1. Introduction

In May 2020, news broke that Rio Tinto – one of the world’s largest diversified mining companies – had destroyed two ancient and sacred rockshelters at Juukan Gorge in Western Australia to expand an iron ore mine.Footnote1 These caves held archaeological evidence of continuous human occupation of 46,000 years.Footnote2 Initially, Rio Tinto executives did not apologise but expressed remorse that the traditional owners, the Puutu Kunti Kurrama and Pinikura (PKKP),Footnote3 were aggrieved and defended their actions as entirely legal.Footnote4 The public was appalled to learn that the destruction of the caves was, in fact, legal. Public outcry and media attention in Australia and internationally provided the impetus for a parliamentary inquiry. Over a period of 16 months, the inquiry provided insight into the complex chain of events leading to the blast, the loss experienced by the PKKP, and the federal and state systems that failed to protect such significant heritage.Footnote5

The inquiry offered the public an unprecedented view into the inner workings of Rio Tinto as they decided to detonate the caves – details that the company did not disclose in its Board-led review, or its initial written submissions and appearances at public hearings. The inquiry also provided insight into the PKKP’s grievances towards the company and the state for their complicity in the destruction of the caves. In its first six months, it focused on the proximate causes of the incident and discovered how market, regulatory and corporate systems empowered Rio Tinto and disempowered the PKKP from protecting their heritage. Over time, it revealed that this type of destruction was not a rare occurrence, but rather a routine practice reflecting the prevailing dynamics of legal and structural inequality that underpins the Australian resources sector.

In Australia, as in other democratic systems, public sector inquiries are ad hoc bodies with varying powers to demand evidence and produce knowledge for policymakers and others to act upon.Footnote6 The value and effect of state-based inquiries has been debated in public administration and other literatures for more than a century. As early as 1849, Smith labelled public sector inquiries ‘pernicious’ self-serving mechanisms for the government of the day.Footnote7 In 1937, Lord KennettFootnote8 referred to these processes as a ‘tribal dance’ performed by governments to create the ‘illusion’ that something profound was taking place, thus forestalling action.Footnote9 Contemporary debates centre on their ability to effect policy change,Footnote10 with Black and Mays reminding us that while public sector inquiries can direct recommendations to any party (public or private) with responsibilities relevant to the issue, they themselves have no authority to formulate policy or to compel any party to act in particular ways.Footnote11 In light of the gravity of events that occurred in the Pilbara in 2020, we examine whether Australia’s Juukan Gorge parliamentary inquiry provides an adequate basis to drive change in the regulation of cultural heritage management in the mining industry.

The paper proceeds by briefly surveying two literatures: community grievance handling in the global mining sector, and public sector inquiries in Australia and elsewhere. We then present a brief timeline of events leading up to the detonation of the Juukan Gorge caves, the scope and format of the inquiry, and the political milieu in which the inquiry was constituted and reported to the public. After briefly describing our methods, we present findings and discussion. In re-tracing the Juukan Gorge inquiry’s discoveries, and the discoveries of previous inquiries, we consider its potential to drive change. While the Juukan Gorge inquiry offered extraordinary insights into the systems and processes that enabled Rio Tinto, it missed several opportunities to challenge key aspects of the underlying system of injustice. The evolving political milieu in Australia, however, may offer some prospects for change.

2. Literature review

2.1. Community grievance handling in the global mining sector

The global mining sector operates in a context of historical, recurring and unresolved local-level grievances, many of which involve Indigenous peoples.Footnote12 Evidence suggests that this grievance landscapeFootnote13 is expanding, with increasing numbers of complaints, allegations and claims making their way into the public domain. Issues relate to the systemic abuse of rights and entitlements through, for example, the compulsory acquisition of land,Footnote14 forced displacement of people,Footnote15 destruction and desecration of heritage and common resources,Footnote16 and violence perpetrated by developers or the state.Footnote17 These issues tend to arise in contexts that lack adequate safeguards and protections for local and land-connected peoples.Footnote18 Much of the critically orientated ‘mines and communities’ literature argues that market, state and corporate systems trade on entrenched systems of structural disadvantage, inequality, and the domination of local and Indigenous peoples and their rights and interests.

Instruments such as local-level agreements have been promoted as an avenue for managing impacts and promoting the more equitable distribution of mining’s risks and benefits.Footnote19 The Juukan Gorge inquiry, however, highlighted the folly of assuming that these instruments offer a solution to the problems of inequality, given the unequal bargaining power between negotiating parties in the absence of state protections, or in the presence of failed protections – a point repeatedly made by established scholars in this area.Footnote20 Likewise, the inquiry highlighted that the application of United Nations (UN) instruments will fail at the local level when states themselves fail to uphold their commitments and obligations.Footnote21 Australia has endorsed the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP),Footnote22 and Rio Tinto had embedded the core tenets of UNDRIP in its corporate policy architecture.Footnote23 The Juukan Gorge inquiry revealed that the company and the state had effectively neutralised these commitments in their front-line practices.

Global mining companies navigate this ‘grievance landscape’ in numerous ways.Footnote24 This includes participation in state-based processes, such as royal commissions, parliamentary inquiries and presidential commissions, such as in the United States (US), and court proceedings, including class actions. Companies also participate in third-party, non-judicial processes, such as those conducted by international finance institutions. One prominent body is the International Finance Corporation (IFC) Compliance Advisor Ombudsman (CAO), which has investigated numerous claims against mining companies that have loan agreements with the IFC.Footnote25 Companies are, at times, compelled to respond to and participate in inquiries conducted by non-governmental organisations (NGOs). From 2000 to 2010, the international NGO Oxfam (Australia), for instance, hosted a Mining Ombudsman to investigate and publish community-level complaints.Footnote26 Companies also navigate the community grievance landscape through informal and private engagements with these same parties.

Finally, companies have their own internal processes. Some of these processes are public facing – although many are not – with grievance handling matters often protected by legal privilege, confidentiality or non-disclosure.Footnote27 On rare occasions, global mining companies have initiated their own public-facing inquiries in response to community-level grievances or incidents.Footnote28 The small number of these company-initiated inquiries stands in contrast to the sheer quantum of grievances that form in and around large-scale mining operations. Fewer than ten public inquiries commissioned by mining companies were identified between 2000 and 2022,Footnote29 whereas hundreds of allegations and claims of abuse are recorded in databases such as the Business and Human Rights Resources Centre (BHRRC). When community grievances are raised publicly, research suggests that it is more common for companies to evade attention and diffuse the debate than subject themselves to scrutiny.Footnote30

2.2. Public inquiries and their purpose

The stated purpose of public inquiries in Australia is to investigate an issue of public concern – a failure, wrongdoing or crisis – to generate knowledge as a basis for policy reform and to avoid future failure.Footnote31 The bulk of contemporary scholarship on inquiries criticises these institutions for failing to drive change – particularly deep, systemic change.Footnote32 Much of this analysis is founded on what external parties expect these inquiries to achieve versus the official state view. In the context of the US, Flitner attributes the perceived failure of presidential commissions to unrealistic expectations regarding their actual purpose.Footnote33 In Australia, the official view is that royal commissions ‘look into’ matters of public and national importance, though Black and Mays contend that their public image implies they will drive change.Footnote34 In the absence of judicial powers, most public sector inquiries succeed (at least to some extent) in focusing attention, collecting and collating evidence, and recommending change to responsible authorities.

The outcomes of landmark inquiries in Australia, particularly those relating to Indigenous peoples, highlight why debate and disagreement about the value and effects of public inquiries is ongoing. In some cases, inquiry recommendations have led to change. In 1973, the Aboriginal Land Rights Commission (also known as the Woodward Royal Commission) led to the establishment of land councils in the Northern Territory and propelled the formation of the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976. In other cases, inquiries fail, or are too slow in achieving change. This was the case for the 1987 Australian Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody (RCIADIC). While federal and state governments adopted the majority of the Commission’s 339 recommendations, Australia maintains unacceptable rates of Aboriginal imprisonment and high numbers of deaths in custody, largely due to systemic gaps in implementation and the systematically racist nature of the criminal justice system.Footnote35

Scholars suggest that while public inquiries may disappoint those who seek rapid and broad-scale change, they are under-recognised for their ability to spur other processes. BulmerFootnote36 and CunneenFootnote37 maintain that even when inquiry recommendations are not implemented, indirect social, cultural and political outcomes can still transpire. In other words, public inquiries can create momentum for future action, even if they do not drive action themselves. Stark argues that different types of learning from inquiries can propel change in ways that are not obvious if we judge inquiries solely on their ability to achieve immediate and observable public policy change.Footnote38 We reflect on this in our analysis of the Juukan Gorge inquiry after providing further background to the process.

3. Background to the Juukan Gorge inquiry

3.1. Brief timeline of the events at Juukan Gorge

Seven years after it had secured ministerial approval to destroy the caves at Juukan Gorge, Rio Tinto decided to exercise its legal right to expand its Brockman 4 mine and access an estimated $135 million worth of iron ore located in the area surrounding Juukan Gorge. The company loaded explosives in early May 2020. The PKKP did not become aware of the imminent destruction until mid-May when they sought access to the site to pay their respects during Australia’s Reconciliation Week. At this point, Rio Tinto continued to load explosives. The PKKP tried to stop, or even just delay, the detonation, but were told by the company that it was too late. The caves were destroyed on 24 May, two days before Sorry Day for Australia’s Stolen Generations. At risk of breaching confidentiality provisions in their Land Use Agreement with Rio Tinto, the PKKP issued a media release the very next day, expressing their distress and stating how ‘deeply troubled and saddened’ they were that the caves had been destroyed, later describing a sense of ‘immense grief’ for the loss.Footnote39 Major media outlets in Australia headlined the incident and the story began to break internationally. The destruction of Juukan Gorge coincided with the timing of George Floyd’s death in America, making it a Black Lives Matter issue in Australia.Footnote40

The historical dimensions of this incident are both complex and intricate, with the blasting event timeline extending back to 2003. It was at this time that native title negotiations between the PKKP and Rio Tinto began, and archaeological studies of the area commenced. The rockshelters in Juukan Gorge were identified as ‘significant’ and estimated to be 21,000 years old.Footnote41 In 2006, an initial Land Use Agreement was signed. Five years later, in 2011, the PKKP entered into a Participation Agreement with Rio Tinto. This guaranteed the PKKP financial benefits but included so called ‘gag clauses’ limiting them from objecting to specific actions in relation to heritage protection, and preventing them from publicly disparaging the company, with financial penalties for a breach. In 2013, as Rio Tinto laid out its mine plans, the company sought ministerial consent under Section 18 of the Aboriginal Heritage Act 1972 (WA) (AHA) to destroy heritage sites at Juukan Gorge, comprising 12 rockshelters and 20 artefact scatters, with salvage excavations to be made at sites referred to as Juukan 1 and Juukan 2. Ministerial consent was granted.

From this point, an archaeological retrieval and salvage operation commenced. New materials obtained in a 2014 dig indicated that the caves were in fact of staggering archaeological significance and were inhabited not 20,000, but more than 46,000 years ago.Footnote42 One item from the caves confirmed DNA links to the present-day PKKP peoples. Reports were written, lectures given and films made about the caves and their significance to knowledge about early humankind, and their importance to the PKKP. In other words, the archaeological and anthropological significance of the caves was no secret. Yet the Minister did not revise their position as new information about the significance of the caves was established, and information about the caves was removed from Rio Tinto’s mine planning system, essentially because, once approved for destruction, their significance was no longer material to the company’s activities. In 2015, the PKKP won their native title claim, although this determination provided no additional power to negotiate with Rio Tinto about the fate of the caves. Six years after the significance of the caves was confirmed, they were destroyed. Most of this was unknown to the general public until it surfaced during the parliamentary inquiry.

3.2. About the inquiry

3.2.1. Scope and format

On 11 June 2020, two weeks after Rio Tinto destroyed the Juukan Gorge caves and two days after the company commissioned its own Board-led review, the Australian Senate approved a parliamentary inquiry. Greens Party Senators Siewert and Hanson-Young supported a motion from Senator Patrick Dodson of the Australian Labor Party to inquire into and report on the destruction.Footnote43 The case was referred to the Joint Standing Committee on Northern Australia (‘the Committee’) chaired by Warren Entsch, a member of the House of Representatives and the Australian Liberal Party. The Committee was ‘joint’ in the sense that it featured membership from the upper and lower house of Australia’s bicameral parliament.

The scope of the inquiry was outlined in terms of reference (TOR) authorising the Committee to inquire into the destruction of the caves, with ten key provisions. These included the operation of the AHA, community consultation and events leading up to the destruction, loss or damages to the PKKP people, and the effectiveness and adequacy of state and federal legislation to protect Aboriginal cultural heritage. In the government inquiries literature, authors have observed that the inquiry TOR can be restrictive.Footnote44 In this case, a tenth term broadened the scope, allowing the Committee to investigate ‘any other related matters’ deemed fit.Footnote45

The process commenced in August 2020 with an initial mandate to report within three-and-a-half months. With the COVID-19 pandemic and associated travel restrictions, the deadline was extended to December 2020, and then again to report the final recommendations by October 2021.

3.2.2. Submissions and hearings

The inquiry surfaced information through written submissions, public hearings and stakeholder engagement, conducted both remotely and in person. The latter involved a field visit to the Pilbara region of Western Australia, where the Committee met with the PKKP people as well as Rio Tinto personnel at the Juukan Gorge site. A total of 177 written submissions, running to some 4,260 pages, were considered by the Committee. Approximately one-third of submissions came from Indigenous organisations and their legal representatives, and one-third from civil society organisations, experts and informed members of the public, with the remainder split among industry, government and members of the public expressing outrage, but without specific reference to the TOR.

The overwhelming majority of submissions condemned the events that led to the destruction of the caves and supported both stronger cultural heritage laws and harsher penalties for breaches. Industry submissions either showed contrition (in the case of Rio Tinto) or indicated that they valued and respected Aboriginal cultural heritage and supported the modernisation of the AHA, while cautioning against duplication of protections at the state and federal levels. These stand in contrast to submissions to an inquiry seven years earlier into the Non-Financial Barriers to Mineral and Energy Resource Exploration where industry mostly objected to the compliance costs of existing legislation and advocated for regulatory ‘streamlining’.Footnote46

The Juukan Gorge inquiry conducted 23 public hearings over its 16 months. Some hearings were able to settle points that were not fully clear in the submissions. For example, did the Western Australian Minister for Aboriginal Affairs have the power to rescind a Section 18 approval if new information came to hand? Ben Wyatt, the Minister in 2020, conclusively said that once an approval had been made, ‘there is effectively nothing I can do’.Footnote47 The PKKP appeared before the Committee on 12 October 2020 and on the same day released a re-edited Rio Tinto-funded documentary, Ngurra Minarli Puutukunti (In Our Country),Footnote48 showing PKKP elders visiting the Juukan Caves in 2015, discussing their significance and expressing frustration at their inability – five years before their eventual destruction – to stop further blasting in the vicinity of the site complex. Rio Tinto appeared before the Committee three times, on 7 August 2020, 16 October 2020, and 27 August 2021. Later hearings focused on cultural heritage matters in other Australian jurisdictions.

3.2.3. Inquiry reports

The Committee tabled two reports and sets of recommendations. The inquiry’s interim report, Never Again, was released in December 2020.Footnote49 Events leading up to the destruction, and concerns over gag clauses in Rio Tinto’s Indigenous Land Use Agreements and issues of free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) were the focus of the first report. It contained seven recommendations directed to three parties. Rio Tinto was to offer a restitution package to the PKKP and undertake a ‘full reconstruction’ of the Juukan rockshelters. The Western Australian Government was to immediately suspend Section 18 of the AHA, cancel permissions to destroy sites already granted, outlaw gag clauses in agreements with mining companies, replace the AHA with modernised legislation as soon as possible, and undertake a ‘mapping and truth-telling project’ to document all sites affected by it. Lastly, the Australian Government was to ‘vigorously’ apply the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Heritage Protection Act 1984 (ATSIHPA) in Western Australia pending the modernisation of the AHA, and then review the ATSIHPA itself.

The final report, A Way Forward, was released in October 2021.Footnote50 It looked farther afield than the interim report, devoting 100 pages to heritage protection in other statesFootnote51 and 35 pagesFootnote52 to heritage protection at the federal level, including the ATSIHPA, the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBCA) and the Native Title Act 1993 (NTA). All recommendations were directed to the Australian Government,Footnote53 including a new legislative framework for cultural heritage, co-designed with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Given that it would take time to do this, the report recommended that ATSIHPA and EPBCA be amended as a first step to make the Minister for Indigenous Australians responsible for all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander heritage matters.Footnote54 According to the report, the framework should ensure that state and territory heritage protections are consistent with UNDRIP, which Australia endorsed in 2009 but has not adequately codified into law; with the Dhawura Ngilan: A Vision for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Heritage in Australia,Footnote55 published in 2020; and with the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization’s (UNESCO) Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage 2003, which it recommended Australia ratify. Additionally, the report recommended that the NTA be reviewed to ensure agreements arising from it are negotiated consistent with the requirements of FPIC and that native title representative bodies be adequately funded, and their governance professionalised. The final recommendation was that a cultural heritage truth-telling process be established, involving all Australians.

4. Methods

Source material for the findings and analysis that follows includes 5,500 pages of documents generated by the inquiry process itself.Footnote56 Archival searches were performed to access source material for the past events they recall, including Trove at the National Library of Australia,Footnote57 Parliament of Western Australia Hansard,Footnote58 reports in departmental archives, and the Internet Archive.Footnote59 Geospatial information for the construction of was obtained from multiple public domain sources, including Data WA, the Parliament of Western Australia, the state’s Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)Footnote60 and Aboriginal Heritage Inquiry System (AHIS),Footnote61 and the National Native Title Tribunal.Footnote62 We also sourced information from otherwise confidential archaeological studies where they were discoverable,Footnote63 and reports tabled in parliaments.Footnote64

5. Findings

At the same time as it illuminated certain matters, the Juukan Gorge inquiry missed the opportunity to illuminate three significant issues: the many prior attempts at legislative reform; the exponential growth of Western Australia’s iron ore industry since 2016; and the sheer volume of under-reported archaeology that highlights the significance of the Pilbara landscape.

5.1. What the inquiry revealed

5.1.1. The workings of legislation and its bearing on cultural heritage

The inquiry examined the workings of Australia’s legal system, including how different legal instruments and associated procedures bear upon Aboriginal heritage. In Australia’s federal system, legislative powers are granted to the Commonwealth (federal government) over defined areas, such as taxation, defence and foreign corporations. A state may pass law over other matters, provided it is not inconsistent with a Commonwealth law. This included, for example, Western Australia’s AHA. All new laws introduced by the Commonwealth must either relate to areas not covered by state laws or rely on an interpretation of existing Commonwealth powers. This includes ATSIHPA and the EPBCA. The ATSIHPA covers situations where state heritage laws, such as the AHA, leave a gap, while the EPBCA relies on the Commonwealth’s external affairs powers through Australia’s adherence to such treaties as the Ramsar Convention, the World Heritage Convention and the Convention on Biological Diversity.

The focal point of the inquiry was sections 16, 17 and 18 of the AHA. In brief, Section 16 provided the state Registrar of Aboriginal sites with authority to permit the archaeological excavation of a registered site. Doing so without approval was an offence under Section 17. Under Section 18, the Aboriginal Cultural Material Committee (ACMC) sits to consider an application from the ‘owner of any land’ including the holders of mining rights but excluding Native Title owners without exclusive rights to disturb a site. The inquiry recognised multiple flaws in this process, including the arbitrariness of how a site is put on, or taken off, the register of sites; that ACMC recommends the approval of a Section 18 before the significance of a site (cultural, spiritual or archaeological) is known;Footnote65 and that the AHA does not expressly provide for consultation with Aboriginal people. There was no means of appeal by traditional owners under Section 18, even when new information of significance came to light. These features of the AHA allowed the Juukan Gorge caves to be destroyed against the wishes of the PKKP.

It is here that the procedural deficiencies of the AHA are thrown into sharp relief. There was no mechanism for the ACMC to be alerted to significant new information, or in fact for the Section 18 permit to be recalled.Footnote66 In the case of Juukan 2, the 2014 salvage excavations made new finds and established more ancient dates. Rio Tinto put some of these artefacts, and a latex peel of a wall of the excavation, on display at the Brockman 4 administration building.Footnote67 However, the Registrar of Aboriginal sites told the inquiry they were not notifiedFootnote68 and only became aware of this information well after the ACMC’s Section 18 assessment. By the time the sites were at imminent risk of destruction, with federal intervention under the ATSIHPA or EPBCA the last resort, expert advice to Rio Tinto was that it was too late to unload the blast charges, and the company proceeded to detonate the caves.

The inquiry reports also document the many obstacles that stood between the PKKP and recourse to the federal ATSIHPA, concluding that ATSIHPA was ‘not sufficient for the purpose of protecting Juukan Gorge’.Footnote69 With respect to NTA, the Committee noted that this had given Aboriginal groups the right to be consulted over the use of their land from the time of the registration of a claim, but it did not override interests already in existence. In the PKKP’s case, they held this right from 2001, well before the determination of their claim in 2015.Footnote70 The interests that were held to prevail over the PKKP’s native title rights included rights granted to Rio Tinto under the Iron Ore (Hamersley Range) Agreement Act 1963.Footnote71 In this respect, and under these circumstances, as the Committee noted, the NTA was ‘limited in [its] efficacy to protect cultural heritage even where native title has been determined’.Footnote72 Inconsistencies with Australia’s endorsement of UNDRIP were highlighted in the final report, with a section dedicated to UNDRIP and FPIC.Footnote73

Members of the Committee, informed members of the public, and indeed practitioners working in other states without knowledge of the Western Australian system of heritage management expressed a degree of surprise that such poor heritage protection can have persisted two decades into the twenty-first century. It is a key contribution of the inquiry that this was brought to the wider public’s attention.Footnote74

5.1.2. Lack of institutional memory

No other Australian parliamentary inquiry has examined the inner workings of a mining company as closely as the Juukan Gorge inquiry – as limited as this examination was to be. The inquiry exposed a lack of institutional memory, and misrepresentation of information in key documentation. On the one hand, Rio Tinto executives told the inquiry they had no knowledge of the significance of the Juukan Gorge caves before they were destroyed. On the other hand, the Committee heard about artefacts that had been on display in the Brockman 4 mining administration building since 2008,Footnote75 including a large map that depicted the gorge sitting outside the planned extent of the mining pit.Footnote76 The inquiry also heard that Rio Tinto had funded a video of elders speaking in front of the caves in 2015 about protecting the caves from disturbance, and their fears about blasting.

The archaeological significance of the Juukan 2 cave was first brought to light in company-sponsored excavations in 2008. At this time, archaeologist Michael Slack and colleagues initially estimated that the caves were 21,000 years oldFootnote77 and recommended Rio Tinto protect the site.Footnote78 The ethnographic significance of the Juukan Gorge complex was made clear in two subsequent ethnographic reports, also funded by Rio Tinto but not circulated publicly. The first was prepared by Roina Williams in 2008,Footnote79 who described the complex of sites as including the Juukan Caves and Purlykuti Creek, a sacred rock pool at the base of the gorge.Footnote80 The complex as a whole was named after Tommy Ashburton, a PKKP man born at Mount Brockman who was also known as Juukan.Footnote81 Williams said the complex was of ‘high ethnographic significance to the PKKP’.Footnote82 A second report was written by Heather Builth and transmitted to Rio Tinto on 10 September 2013.Footnote83 Builth recommended that ‘Purlykuti be recorded with the Department of Aboriginal Affairs (DAA) as an ethnographical place of high significance’.Footnote84 What the inquiry discovered was that this knowledge was internally mis-managed, to the point that when Rio Tinto submitted a Section 18 application on 17 October 2013, Slack and Builth’s recommendations were omitted.Footnote85 Summarising the Juukan complex as a whole, Rio Tinto listed the ethnographic significance of those sites as ‘N/A’ (that is, not applicable).Footnote86 With the Section 18 approval in place, information about the significance of the caves was removed from the company’s mine planning system. Former Iron Ore Chief Executive Officer (CEO) Chris Salisbury explained at later hearings that the company’s mine planning systems had no trigger or flag to alert operators that these locations contained precious Aboriginal heritage.Footnote87

5.1.3. Indigenous voices in the inquiry

As government inquiries go, the Juukan Gorge inquiry had an exceptionally strong Indigenous voice, with 25 per cent of the submissions from Indigenous corporations, individuals who identified as Indigenous, and organisations with a primary governance, business or research engagement with Indigenous people. This contrasts markedly with the inquiry into the Non-Financial Barriers to Mineral and Energy Resource Exploration, where a small number of NGOs attempted to inject a non-business viewpoint into proceedings. The PKKP and five neighbouring Aboriginal corporations with mines on their land represented their views in submissions.

The Committee was confronted by numerous recitals through the inquiry hearings of the various forms of disadvantage faced by Aboriginal groups interfacing with large-scale mining in the Pilbara. Issues included: limited funding from government; dependency on drawing down funds arising from agreements with mining companies that pre-dated the modern corporations; loss-making heritage survey work;Footnote88 the loss of over 400 sites where 93 per cent of a group’s country was covered by mining tenements; the imbalance between today’s mining profits and the small (or no) income received by traditional owners under agreements made before the mining boom;Footnote89 the AHA serving to expedite mine developments but not the protection of places or heritage; the granting of Section 18 consents before the full significance of archaeological sites is understood; and the difficulties of sharing income from a trust fund among hundreds of people.Footnote90

Each group recounted their own experience of losing sites and/or trying to protect critical sites of equivalent cultural and heritage significance to the Juukan Gorge caves. These instances included the loss felt by the Eastern Guruma over the inability to protect heritage around the Marandoo mine and haul trucks damaging the Yirra site by dislodging boulders as they traversed a land bridge above the site at the Channar mine on Yinhawangka country. The Yirra site showed evidence of 23,000 years of occupation at the time of the inquiry and is now dated at 50,000 years old.Footnote91 Another instance is the 40,000-year-old rockshelter at the Silvergrass mine on Eastern Guruma country, which Rio Tinto obtained ministerial consent under Section 18 to destroy – although they have since agreed not to exercise the right to do so.Footnote92

5.2. What the inquiry overlooked

5.2.1. The Aboriginal Heritage Act 1972 and the political economy of Western Australia

The final inquiry report, A Way Forward, notes that the AHA was the subject of five different reviews – in 1984, 1991, 1995, 1996 and 2011, but said little more than that most attempts at reform ‘failed to garner parliamentary support and lapsed at the conclusion of parliamentary terms’.Footnote93 This brief remark makes evident the political competition between supporting Aboriginal interests and those of mining and other developers, and federal–state policy differences, even within the same party.

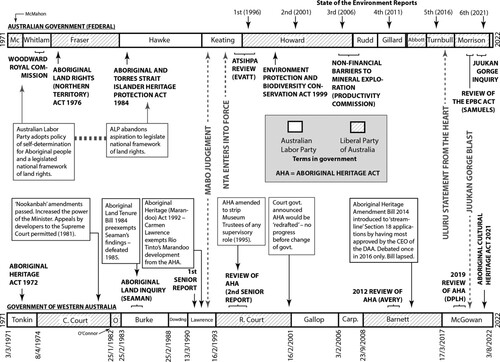

captures the sequence of government-commissioned reports and reviews bearing on the protection of cultural heritage in Western Australia at both state and federal levels since 1971 with respect to the terms of the two main parties that form government. The twin starting points are the passing of the AHA in Western Australia, with bipartisan support, in 1972, and the 1973–1974 findings of the Woodward Royal Commission, underpinned by the Australian Labor Party’s adoption of a policy of self-determination for Indigenous Australians. The Juukan Gorge inquiry’s final report discusses eventual amendments to the AHA that weakened and then abolished oversight from the Trustees of the Western Australian Museum. But it did not capture the political dynamics at play at the time. The Labor Party had returned to govern federally in 1983, with an aspiration of passing a national land rights framework. However, it was not until the High Court judgement in Mabo v Queensland (No 2) in 1992 that the NTA was subsequently formulated – a different regime than originally envisaged, and one without provisions for self-determination, or FPIC for resource developments on native title lands.

At the state level, the incoming Labor government in 1983 launched the Western Australian Aboriginal Land Inquiry.Footnote94 After a year of state-wide consultation, Commissioner Paul Seaman concluded that Aboriginal people should have a mining veto, going further than the consultation required in the International Labour Organization’s Convention 169 later in the 1980s and anticipating the consent required by UNDRIP 23 years later. Seaman’s findings were sidelined by the Western Australian Government on an economic growth trajectory driven by mining. Although Seaman’s findings were summarised by Patrick Dodson in his part of the RCIADIC in 1991, the report is not mentioned in either of the two reports of the Juukan Gorge inquiry.

The long road to the present, through inquiry after inquiry, gives cause for us to reflect on what is happening. It is normal to expect an evolution in the sophistication of legislative mechanisms over time in line with community expectations. But in heritage protection, the situation presents more as a contest between vested interests and reformers, where the latter have been unable to prevail. It is startling that the same arguments about ‘green tape’, ‘black tape’ and the costs of mining exploration used in the 1980sFootnote95 to push back against the idea of Aboriginal groups having a say over heritage sites and land access for miningFootnote97 are being deployed again in the 2020s.Footnote98 Panels of experts across the political spectrum have been saying for decades that efforts to conserve Aboriginal heritage are not working.Footnote99 From this vantage point, the Juukan Gorge inquiry repeats the narrative.

5.2.2. The scale and expansion of Western Australia’s iron ore industry

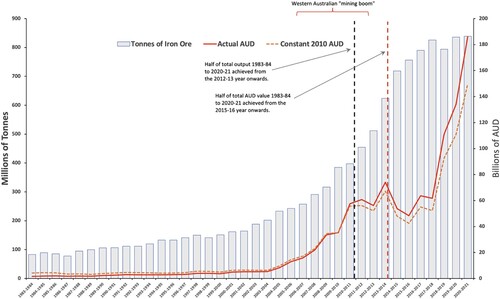

In Australia, a reasonably informed public would be aware that iron ore is produced in the Pilbara Region of Western Australia. A more informed public might know that Tom Price and Newman are mining towns with several mines in the area, and the ore is loaded onto long trains that take it to export terminals on the Pilbara coast. This picture was basically correct from the mid-1960s to the early 2000s. However, the massive scale of expansion over the past 20 years is astonishing. Using data from the Western Australian Department of Mines, Industry Regulation and Safety, shows iron ore production in Western Australia, 1983–2021. These data show that the value of iron ore production was flat for the 20 years up to 2004, and then began to trend upwards as demand from China accounted for an increasing proportion of Western Australian exports. A period now looked back on as Australia’s ‘mining boom’ began around 2006 and looked to be over in 2014.

Figure 2. Value of tonnage of iron ore production in Western Australia, 1893–2021.Footnote96

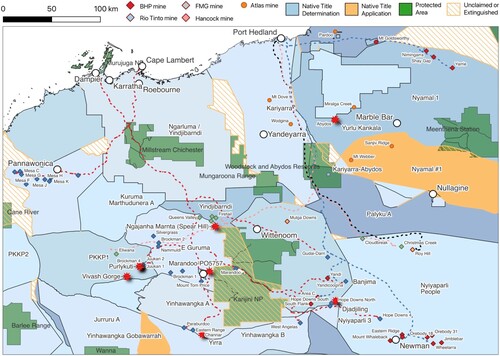

However, for iron ore in Western Australia, the boom never subsided. In tonnes exported, there was no pause. In export dollars, a phase of lower prices lasted until about 2016, then higher growth than ever seen previously commenced. In Australian dollar terms, half of the value of total iron ore sales since 1983–1984 has been created post 2015. It makes little difference to repeat the calculation in constant 2010 dollars. The recency of this growth, and the pressure placed on traditional owners, can be difficult to apprehend. Sara Slattery, the CEO of the Robe River Kuruma Aboriginal Corporation, told the Committee: ‘not very many Aboriginal people … fully understand the impact of mining on country … While they see the trains going by, they don’t actually see all the mines and the actual large footprint that these mines do have’.Footnote102 There are in fact four separate rail networks servicing over 40 active mines in the Pilbara – more if the multiple pits at some mines are counted separately.Footnote103 As many as nine new mines have opened in the last two years ().

Figure 3. Iron ore mines in the Pilbara Region, Native Title and protected areas, and selection of archaeological sites.100

The significance of this context for heritage protection is that traditional owner groups are beset by demands for heritage assessments and land use agreements that need to be conducted in short time frames to meet the industry’s development priorities. These agreements are not only urgent, but numerous and complex, and being negotiated in a landscape with historical grievances and cumulative social and environmental impacts. One agreement between the PKKP and Rio Tinto was said to have been a 740-page document.Footnote104 The inquiry heard from a representative of the PKKP that the regional representative body, the Yamatji Marlpa Aboriginal Corporation (YMAC), created plain English summaries but that they were handed out as they arrived at the meetings, not beforehand.Footnote105 On this basis, the representative said they were not able to exercise FPIC.Footnote106

During the inquiry the Yindjibarndi, claimants over vacant Crown land where the Solomon Hub and Firetail mines were being built, explained how they fell into dispute with Fortescue Metals Group (FMG) over heritage destruction in 2007. The Yindjibarndi dispensed with the services of YMAC and hired their own lawyer, seeking stronger protection and a mining royalty as FMG was offering a capped annual payment (in the context of a mining boom). A 13-year legal battle followed, and a 2011 split among the Yindjibarndi, explained in summary in the inquiry’s interim reportFootnote107 and again in the final report.Footnote108 Further detail is available in the publications of Paul Cleary.Footnote109

Cases such as these illuminate what the final report called the ‘onerous burden’ on Aboriginal groups having to deal with mining companies on unequal terms. This was clear for the six neighbouring groups that engaged with the inquiry – the PKKP,Footnote110 Robe River Kuruma,Footnote111 Banjima,Footnote112 Eastern Guruma,Footnote113 YinhawangkaFootnote114 and Yindjibarndi.Footnote115 It is unclear whether other groups in the Pilbara had the capacity to make submissions or whether they were averse to participation in the inquiry process. In any case, their non-appearance may raise doubt as to the completeness of the insights gained about mining’s destructive effects on Aboriginal heritage in the Pilbara.

5.2.3. The extent of the archaeological effort in the Pilbara

A major reveal in the course of the inquiry was the fact that consent to destroy the caves was approved in 2013 under a Section 18 application before their full archaeological significance was understood, and that from the point of approval, the Minister considered that he had no basis to reverse that decision – no matter the findings of subsequent archaeological findings. This resulted in the perverse situation, much vented in the submissions from the public, that a 46,000-year-old site could be discovered only to be blown up by a mining company. The submissions and hearings went on to show that, under the AHA, gaining a better understanding of the significance of the Juukan sites was not the purpose of the final excavations in 2014. This was salvage archaeology only, typically carried out prior to commencing an infrastructure project as a last attempt to rescue artefacts from the path of bulldozers. This explained how, administratively at least, the caves were doomed. The final inquiry report recommended an overhaul of legislation such that excavations and heritage surveys be conducted ‘at the beginning of any decision-making process’, allowing traditional owners time to assess the value of sites and either consent to (including with conditions) or prevent their destruction.Footnote116

It was not necessary for the inquiry to apprehend the totality of Australian archaeology, but its findings overlook how little archaeology, as a scientific field, shares with mining and, consequently, how this impacts (or fails to impact) organisational decision-making.

Consider the two following observations. The archaeologist Bird reviews a 2018 monograph reporting the excavation of six rockshelter sites at Rio Tinto’s Hope Downs 1 mine on Banjima country. Bird notes that ‘Little has been previously published’, except for a paper announcing a 41,000-year-old date at the Djadjiling shelter,Footnote117 and that ‘the comprehensive publication of these six rockshelters has certainly been worthwhile and demonstrates the value of large-scale excavations in the region’.Footnote118 The volume itself runs to 464 pages, has contributions by 16 experts, including two Martidja Banyjima elders, and reports on sites across a 4,250-hectare area, including three additional rockshelters dating back 36,000–47,000 years, discovered between 2007 and 2010 following a 2002 Section 18 application.Footnote119 A second archaeologist, Winter, was working on a heritage survey at another mine in the same time period. In his writing, he recounts how company officials pressured the archaeological survey team to provide spatial data at the end of each day’s work so that drilling could commence the next day.Footnote120

Clearly, there is a gulf between the kind of forensic work required to make sense of multiple sites over a wide area, and the expectations of miners. In the inquiry, the Australian Archaeological Association drew attention to the need to assess sites in a manner consistent with best practice professional standards; that is, painstakingly and before decisions relating to Aboriginal heritage and its management are made. The Committee absorbed this by recommending that a new framework for cultural heritage protection be developed at a national level through a process of co-design with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.Footnote121

However, this recommendation elides the scale of cultural heritage and archaeological work being done in the Pilbara by both non-Aboriginal and Aboriginal archaeologists and by the cultural mapping arms of Aboriginal corporations.Footnote122 There are not one or two teams excavating rockshelters here and there obtaining occasional ancient dates, but multiple teams working across a vast region and reporting multiple ancient dates in published works.Footnote123 A book published during the inquiry reported on archaeological investigations since 2006 at 19 rockshelters at FMG’s Cloudbreak and Christmas Creek mines.Footnote124 A reviewer of the book rightly observed that ‘the Pilbara … is perhaps the most intensely archaeologically surveyed and excavated region on the continent’.Footnote125

The picture is one of the huge demands on traditional owner groups to find teams and consultancy firms to comply with heritage survey requirements as fast as possible. Time is not always available to do the fieldwork and to understand the significance of what is being found relative to development timelines, and the significance of what is found is being overlooked outside the field. Directors of the Wintawari Guruma gave evidence before the inquiry about how their problems were doubled when dealing with FMG over the construction of the Eliwana railway.Footnote126 They fell into dispute with FMG over land use agreements, and FMG responded by withholding royalty payments due to them during 2019.Footnote127 They were simultaneously fighting to prevent the railway from cutting through the 50 sites found near a cultural feature they call Ngajanha Marnta (also known as Spear Hill), which included a rockshelter with evidence of occupation dating back 23,000 years. The Wintawari Guruma’s archaeologist said that on this occasion the Minister granted a Section 18 application in the absence of findings from emergency archaeological investigations. The ancient rockshelter now exists in ‘a narrow sliver of land underneath a heavy-duty haul road and within metres of the railway’.Footnote128

While the inquiry exposed various legal and legislative paradoxes that allowed the caves to be destroyed, and the frustrations of traditional owner groups, it did not highlight the wider archaeological effort in the Pilbara over the past two decades. This effort is yielding results of high significance to the deep prehistory of the continent. This alone merits a long pause for reflection.

6. Discussion

The Juukan Gorge inquiry recommends progressing a range of law reforms for Aboriginal heritage to be valued and protected, with special reference to control of assessment processes by traditional owners, consistent with UNDRIP and Dhawura Ngilan. While the hearings heard many statements about profit coming before heritage protection, the inquiry did not examine the market forces at play, the influence of industry lobbyists, or the nation’s economic dependency on iron ore exports from the region.Footnote129

The inquiry reports propose a ‘truth telling’ process, including the mapping of existing and destroyed cultural heritage sites. What we have sought to do in this paper is to draw attention to three critical problems – the many fruitless attempts at legislative reform over 40 years; the scale of the never-ending mining boom in Western Australia (and to create a basic map of minesFootnote130); and to highlight the volume and significance of the archaeological finds made during the twenty-first century – which far exceeds what was conveyed by the media or, indeed, the inquiry process itself.

The inquiry did not consider why previous attempts at reform, of which there have been many, did not succeed. Premiers have assumed power with the best of intentions, like Carmen Lawrence, who held the Aboriginal Affairs portfolio in her first Ministry, but who went on to pass objectively bad legislation (in Lawrence’s case, the Aboriginal Heritage (Marandoo) Act 1992). Ministers of Aboriginal Affairs including Ben Wyatt, himself of Yamatji heritage, have overseen thorough processes of review, yet changes fall short of inquiry findings and recommendations, and community expectations (in Wyatt’s case, the Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Act 2021).

At the time of the Juukan Gorge blast, heritage protection in Australia and Western Australia had advanced little since the Hawke and Burke era of government and had yet to reflect the position reached in the 1984 Seaman Report. A full assessment of the situation is beyond the scope of this paper but would need to take into account Western Australia's new Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Act 2021, passed at the conclusion of the Juukan Gorge inquiry, and which rests on a co-design process taking place before this law comes into effect in late 2022. Economic and political interests have long prevailed over Aboriginal control over land sought for mining, and so we should assume they may continue to do so – despite the sobering revelations of the Juukan Gorge inquiry.

7. Conclusion

The parliamentary inquiry into the destruction of the 46,000-year-old rockshelters at Juukan Gorge enlivened public debate about the deep structural inequalities that underpin Australian society, and the mining industry. It connected this seemingly isolated event to the underlying systems that enable the destruction of heritage and benefit from resource extraction. In doing so, it shone a light on the absence of human rights-compatible safeguards for Aboriginal heritage protection and the systemic abuse of Australia’s First Peoples and their connection to country. While these issues have not been altogether neglected by past state and federal governments, previous processes of inquiry have failed to establish sufficient momentum to drive change. The Juukan Gorge inquiry did not describe, in any detail, the numerous prior attempts at inquiry and reform, over half a century. This type of inertia lends support to the ‘mobilisation of bias’Footnote131 argument that continues to dominate the public administration literature – that political and economic elites readily manipulate government inquiry processes for their own benefit.

By way of conclusion, we note two arenas for future research that pushes beyond asking what happened at Juukan Gorge and towards asking why the underlying systems are so entrenched and how they might shift. Firstly, there is an opportunity for researchers to insist on access to the organisational domain to further understand the internal dynamics of mining companies themselves.Footnote132 The inquiry offered a glimpse into these dynamics as they related to the Juukan Gorge event but little insight into why organisational structures militate against conforming to the standards and policies to which mining companies so publicly commit. As Aboriginal academic Noel Pearson wrote in his searing critique of Rio Tinto’s effort to understand why it acted as it did, the Board-led review was little more than a ‘fig leaf’ – a feeble cover-up that failed to reveal anything of substance.Footnote133 Unless there is a willingness on the part of mining companies to understand the drivers of corporate social irresponsibility,Footnote134 future reform processes will remain blind to the issues that they claim to address.

Secondly, industry discourse suggests that companies are moving towards greater transparency in their activities and actions. In contrast, we found companies continue to report vaguely, particularly with respect to spatial data, making accessing even the most basic information about mining in the Pilbara a difficult and laborious task.Footnote135 Discoverable information is so patchy and buried that it must be described as a disclosure deficit. Identifying the spatial intersections between mining activities, native title claims and determinations, land tenure arrangements, and archaeological sites of significance must be a focus of future research efforts to map and understand dynamics on the ground in real time. Companies may not have actively colluded to obscure the intensification of their activities in the Pilbara, but they nonetheless managed to obscure vital knowledge that would otherwise have provided an interested public a basis upon which to ask informed questions for the purposes of public accountability.

Finally, we note that in May 2022, two years after the destruction of the Juukan Gorge rockshelters, Australia installed a Labor government committed to implementing the Uluru Statement from the Heart,Footnote136 that includes a call for constitutional change and structural reform to address powerlessness, and a process of truth-telling. In November 2022, the federal Environment Minister tabled the government’s response to the Juukan Gorge inquiry in federal Parliament and committed to implementing seven of the eight recommendations contained in the final report.Footnote137 Within hours, a co-design partnership agreement was signed by the Australian Government and the First Nations Heritage Protection Alliance to begin the process of designing new, stand-alone First Nations heritage legislation. Whereas previous initiatives to improve Aboriginal heritage protections were scuppered by elite politics, the Australian public and the government today appear more alert to these issues and underlying systems of inequality. These changing conditions, including a follow-on inquiry into Australia’s endorsement of the UNDRIP, and a clearer sense of the drivers for corporate irresponsibility, may enable Australia to engage its colonial legacy of trading broadscale destruction of Aboriginal heritage for economic gain through extractive industries.

Acknowledgements

The authors are extremely grateful to colleagues Emma Garlett and Rodger Barnes for their comments and corrections on drafts of the manuscript, and John Owen, who continues to challenge our thinking on mining's grievance landscapes.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 PKKPAC, ‘Ancient Deep-Time Rock Shelters Believed Destroyed in Pilbara Mining Blast, Calls for Greater Flexibility to Retain Sites’ <https://pkkp.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/PKKP-20200525-FINAL-Media-Release-Rio-Tinto-Juukan-Gorge-blasts.pdf> accessed 28 April 2022; Tiffanie Turnbull, ‘Destruction of Ancient Aboriginal Site Sparks Calls for Reform in Australia’ (Reuters, 29 May 2020) <www.reuters.com/article/us-australia-rights-mining-feature-trfn-idUSKBN2351UK> accessed 29 August 2022; BBC, ‘Mining Firm Rio Tinto Sorry for Destroying Aboriginal Caves’ (BBC, 31 May 2020) <www.bbc.com/news/world-australia-52869502> accessed 29 August 2022

2 Michael Jon Slack, Wallace Boone Law and Luke Andrew Gliganic, ‘The Early Occupation of the Eastern Pilbara Revisited: New Radiometric Chronologies and Archaeological Results from Newman Rockshelter and Newman Orebody XXIX’ (2020) 236 Quaternary Science Reviews 106240

3 In this paper, we refer to the custodians of those sites as the ‘PKKP’ or ‘PKKP traditional owners’. The PKKP Aboriginal Corporation comprises ‘two separate but related language groups speaking for their own country, as well as a shared area’. See ‘About PKKP – PKKP Aboriginal Corporation’ <https://pkkp.org.au/about-pkkp> accessed 29 November 2022

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

4 Rio Tinto, ‘Juukan Gorge’ <www.riotinto.com/news/inquiry-into-juukan-gorge> accessed 28 April 2022

5 For a commentary on the case and the interim report findings, see Judith Preston and Donna Craig, ‘In Plain Sight – From Juukan Caves Destruction to Just Development’ (2021) 40 (3) Journal of Energy & Natural Resources Law 361 <https://doi.org/10.1080/02646811.2021.1984036>

6 Scott Prasser, ‘Royal Commissions in Australia: When Should Governments Appoint Them?’ (2006) 65 Australian Journal of Public Administration 28

7 Joshua Toulmin Smith, Government by Commissions Illegal and Pernicious: The Nature and Effects of All Commissions of Inquiry and Other Crown-Appointed Commissions: The Constitutional Principles of Taxation: And the Rights, Duties, and Importance of Local Self-Government (S Sweet 1849)

8 Quoted in M Greenwood, ‘On the Value of Royal Commissions in Sociological Research, with Special Reference to the Birth-Rate’ (1937) 100 Journal of the Royal Statistical Society 396

9 HD Clokie and WJ Robinson, Royal Commissions of Inquiry (Stanford University Press 1937)

10 Patrik Marier, ‘The Power of Institutionalized Learning: The Uses and Practices of Commissions to Generate Policy Change’ (2009) 16 Journal of European Public Policy 1204; Michael Mintrom, Deirdre O’Neill and Ruby O’Connor, ‘Royal Commissions and Policy Influence’ (2021) 80 Australian Journal of Public Administration 80; Alastair Stark and Sophie Yates, ‘Public Inquiries as Procedural Policy Tools’ (2021) 40 Policy and Society 345

11 Nick Black and Nicholas Mays, ‘Public Inquiries into Health Care in the UK: A Sound Basis for Policy-Making?’ (2013) 18 Journal of Health Services Research & Policy 129

12 Following the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples 2007, we use ‘Indigenous’, acknowledging that other terminology may be preferred, including First Nations or First Peoples.

13 John R Owen and Deanna Kemp, ‘“Free Prior and Informed Consent”, Social Complexity and the Mining Industry: Establishing a Knowledge Base’ (2014) 41 Resources Policy 91

14 David Szablowski, ‘Mining, Displacement and the World Bank: A Case Analysis of Compania Minera Antamina’s Operations in Peru’ (2002) 39 Journal of Business Ethics 247; Jeffrey Bury, ‘Mining Mountains: Neoliberalism, Land Tenure, Livelihoods, and the New Peruvian Mining Industry in Cajamarca’ (2005) 37 Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 221

15 Theodore E Downing, Avoiding New Poverty: Mining-Induced Displacement and Resettlement (International Institute for Environment and Development 2002) 52; John R Owen and Deanna Kemp, ‘Mining-Induced Displacement and Resettlement: A Critical Appraisal’ (2015) 87 Journal of Cleaner Production 478

16 I Keen, ‘Aboriginal Beliefs vs. Mining at Coronation Hill: The Containing Force of Traditionalism’ (1993) 52 Human Organization 344; Nick Bainton, C Ballard and K Gillespie, ‘The End of the Beginning? Mining, Sacred Geographies, Memory and Performance in Lihir’ (2012) 23 The Australian Journal of Anthropology 22; Gareth Lewis and Ben Scambary, ‘Sacred Bodies and Ore Bodies: Conflicting Commodification of Landscape by Indigenous Peoples and Miners in Australia’s Northern Territory’ in Pamela McGrath (eds), Right to Protect Sites: Indigenous Heritage Management in the Era of Native Title (Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies 2016) 221

17 Gail Whiteman and Katy Mamen, ‘Examining Justice and Conflict Between Mining Companies and Indigenous Peoples: Cerro Colorado and the Ngabe-Bugle in Panama’ (2002) 8 Journal of Business and Management 293

18 Owen and Kemp, ‘Free Prior and Informed Consent’ (n 13); John R Owen and others, ‘Fast Track to Failure? Energy Transition Minerals and the Future of Consultation and Consent’ (2022) 89 Energy Research & Social Science 102665

19 Rio Tinto, ‘Why Agreements Matter’ (2016) <www.riotinto.com/-/media/Content/Documents/Sustainability/Corporate-policies/RT-Why-agreements-matter.pdf> accessed 29 August 2022

20 Ciaran O’Faircheallaigh, ‘Negotiating Cultural Heritage? Aboriginal–Mining Company Agreements in Australia’ (2008) 39 Development and Change 25; Marcia Langton and Odette Mazel, ‘Poverty in the Midst of Plenty: Aboriginal People, the “Resource Curse” and Australia’s Mining Boom’ (2008) 26 Journal of Energy & Natural Resources Law 31

21 S James Anaya, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples on Extractive Industries and Indigenous Peoples (2013) <https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/ajicl32&i=126> accessed 29 August 2022

22 United Nations, ‘United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples’ (2007) <www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/wp-content/uploads/sites/19/2018/11/UNDRIP_E_web.pdf> accessed 29 August 2022

23 Rio Tinto, ‘Human Rights Policy’ (Human Rights, 2015) <https://www.riotinto.com/en/sustainability/human-rights> accessed 19 December 2022; Rio Tinto, ‘Why Agreements Matter’ (n 19)

24 Deanna Kemp and John R Owen, ‘Grievance Handling at a Foreign-Owned Mine in Southeast Asia’ (2017) 4 The Extractive Industries and Society 131

25 IFC CAO, ‘Cases | Office of the Compliance Advisor Ombudsman’ <www.cao-ombudsman.org/cases> accessed 29 August 2022

26 Oxfam Australia, ‘Mining Ombudsman’ (Trove, 19 July 2005) <webarchive.nla.gov.au/awa/20050718175728/www.oxfam.org.au/campaigns/mining/ombudsman/index.html> accessed 5 September 2022

27 Deanna Kemp and Frank Vanclay, ‘Human Rights and Impact Assessment: Clarifying the Connections in Practice’ (2013) 31 Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 86

28 Case examples include: John Harker, Saloman Kalmonovitz, Nick Killick and Elena Serrano, ‘Cerrejon Coal and Social Responsibility: An Independent Review of Impacts and Intent’ (2008) <https://www.cerrejon.com/sites/default/files/2021-10/report-february-2008.pdf> accessed 19 December 2022; John Harker, Haroutune Armenian, Hayk Akarmazyan and Nune Harutyanyan, ‘Amulsar Independent Advisory Panel: Annual Report 2017-2018’ (2018) <https://www.lydianarmenia.am/img/uploadFiles/2d08074978e06bb0db97AmulsarIndependentAdvisoryPanel-AnnualReport2017-2018.pdf> accessed 19 December 2022; Enodo Rights, ‘Pillar III on the Ground An Independent Assessment of the Porgera Remedy Framework’ (2016) <https://www.enodorights.com/assets/pdf/pillar-III-on-the-ground-assessment.pdf> accessed 19 December 2022; Tim Martin, Miguel Cervantes Rodriguez, Myriam Mendez-Montalvo and Deanna Kemp, ‘Tragadero Grande: Land, Human Rights, and International Standards in the Conflict Between the Chaupe Family and Minera Yanacocha: Report of the Independent Fact Finding Mission’ (RESOLVE NGO 2016) <https://www.resolve.ngo/docs/yiffm-final-report-english.pdf> accessed 19 December 2022

29 Deanna Kemp and John R Owen, ‘Public–Private Inquiries: Institutional Intermediaries and the Transparency Nexus in Global Resource Development’ (2021) 21 Global Environmental Politics 143

30 Rajiv Maher, Moritz Neumann and Mette Slot Lykke, ‘Extracting Legitimacy: An Analysis of Corporate Responses to Accusations of Human Rights Abuses’ (2022) 176 Journal of Business Ethics 609

31 ‘Making Inquiries: A New Statutory Framework: Report’ (Australian Law Reform Commission 2009) <www.alrc.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/ALRC111.pdf> accessed 29 August 2022

32 Alastair Stark, ‘Left on the Shelf: Explaining the Failure of Public Inquiry Recommendations’ (2019) 98 Public Administration <https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12630>

33 David Flitner Jr, The Politics of Presidential Commissions: A Public Policy Perspective (Transnational 1986)

34 Black and Mays (n 11)

35 Marcia Langton, ‘Why the Black Lives Matter Protests Must Continue: An Urgent Appeal by Marcia Langton’ [2020] The Conversation <https://theconversation.com/why-the-black-lives-matter-protests-must-continue-an-urgent-appeal-by-marcia-langton-143914> accessed 29 August 2022

36 Martin Bulmer, ‘Increasing the Effectiveness of Royal Commissions: A Comment’ (1983) 61 Public Administration 436

37 Chris Cunneen, ‘Assessing the Outcomes of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody’ (2001) 10 Health Sociology Review 53

38 Alastair Stark, ‘Policy Learning and the Public Inquiry’ (2019) 52 Policy Sciences 397; Stark and Yates (n 10)

39 PKKPAC (n 1); ‘Juukan Gorge Inquiry Hansard 12 October 2020’ 2 <www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Joint/Former_Committees/Northern_Australia_46P/CavesatJuukanGorge/Public_Hearings> accessed 29 August 2022

40 Rio Tinto and Juukan Gorge: Executive Purge Should Be the First, Not Last, Step towards Reform and Remedy’ (Business & Human Rights Resource Centre) <www.business-humanrights.org/pt/blog/rio-tintos-executive-purge-should-be-the-first-not-last-step-towards-reform-and-remedy-for-juukan-gorge> accessed 30 August 2022

41 Michael Slack, Melanie Fillios and Richard Fullagar, ‘Aboriginal Settlement During the LGM at Brockman, Pilbara Region, Western Australia’ (2009) 44 Archaeology in Oceania 32

42 Slack, Law and Gliganic (n 2)

43 Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia, ‘46th Parliament Senate Notice Paper’ <https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/chamber/notices/46f455f3-cdb3-4a07-8d9d-251ac3f389f5/toc_pdf/sen-np.pdf;fileType=application%2Fpdf#search=%22chamber/notices/46f455f3-cdb3-4a07-8d9d-251ac3f389f5/0000%22> accessed 29 August 2022

44 Dominic Elliott and Martina McGuinness, ‘Public Inquiry: Panacea or Placebo?’ (2002) 10 Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 14

45 Parliament of Australia, ‘Terms of Reference’ <www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Joint/Former_Committees/Northern_Australia/CavesatJuukanGorge/Terms_of_Reference> accessed 30 August 2022

46 Productivity Commission, Non-Financial Barriers to Mineral and Energy Resource Exploration: Inquiry Report No. 65 (Productivity Commission 2013)

47 ‘Juukan Gorge Inquiry Hansard 7 August 2020’ 32 <www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Joint/Former_Committees/Northern_Australia_46P/CavesatJuukanGorge/Public_Hearings> accessed 29 August 2022

48 Ngurra Minarli Puutukunti (directed by Ngaarda Media, 2020) <www.facebook.com/watch/?v=1548236238897139> accessed 29 August 2022

49 JSCNA, Never Again: Inquiry into the Destruction of 46,000 Year Old Caves at the Juukan Gorge in the Pilbara Region of Western Australia: Interim Report (JSCNA 2020)

50 JSCNA, A Way Forward: Final Report into the Destruction of Indigenous Heritage Sites at Juukan Gorge (JSCNA 2021)

51 Ibid 43–148

52 Ibid 149–184

53 Recommendations in the final report were additional to the interim report and did not supersede those of the first report.

54 At the time of writing, this change had not occurred.

55 HCOANZ, ‘Dhawura Ngilan: A Vision for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Heritage in Australia’ (Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment, Heritage Chairs of Australia and New Zealand Secretariat 2020) <www.dcceew.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/dhawura-ngilan-vision-atsi-heritage.pdf> accessed 29 August 2022

56 Parliament of Australia, ‘Committees’ <www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees> accessed 29 August 2022

57 ‘Trove Spotlight’ (Trove) <https://trove.nla.gov.au> accessed 30 August 2022

58 ‘Parliament of Western Australia’ <www.parliament.wa.gov.au/WebCMS/WebCMS.nsf/index> accessed 30 August 2022

59 ‘Internet Archive: Digital Library of Free & Borrowable Books, Movies, Music & Wayback Machine’ <https://archive.org> accessed 30 August 2022

60 ‘EPA WA | EPA Western Australia’ <www.epa.wa.gov.au> accessed 30 August 2022

61 ‘Search Aboriginal Sites or Heritage Places (AHIS)’ <www.wa.gov.au/government/document-collections/search-aboriginal-sites-or-heritage-places-ahis> accessed 30 August 2022

62 ‘National Native Title Tribunal Website’ <www.nntt.gov.au/Pages/Home-Page.aspx> accessed 30 August 2022

63 See eg J Dortch and T Sapienza, ‘Site Watch: Recent Changes to Aboriginal Heritage Site Registration in Western Australia’ (2016) 4 Journal of the Australian Association of Consulting Archaeologists 1

64 See eg R Hovingh and L Sinclair, ‘A Report Detailing an Indigenous Archaeological Heritage Assessment of the Flying Fish (EXP_EAS_ 036) Exploration Area’ (for Windiwari Guruma Aboriginal Corporation and Fortescue Metals Group 2009) (October 2018 Legislative Council Tabled Paper [2131] 31)

65 Government of Western Australia, ‘Juukan Gorge Inquiry Submission 24’ 2 <www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Joint/Former_Committees/Northern_Australia/CavesatJuukanGorge/Submissions> accessed 29 August 2022

66 ‘Juukan Gorge Inquiry Hansard 12 October 2020’ (n 40) 14

67 Rio Tinto, ‘Brockman Syncline 4 Mine Closure Plan – Additional Information Part 12’ (Environmental Protection Agency 2018) 55 <www.epa.wa.gov.au/proposals/brockman-syncline-4-iron-ore-project-%E2%80%93-marra-mambas-proposal> accessed 29 August 2022

68 ‘Juukan Gorge Inquiry Hansard 20 November 2020’ 7 <https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/committees/commjnt/7579e369-a0e6-4171-b5a9-1fb0b159a7ea/toc_pdf/Joint%20Standing%20Committee%20on%20Northern%20Australia_2020_11_20_8359_Official.pdf;fileType=application%2Fpdf#search=%22committees/commjnt/7579e369-a0e6-4171-b5a9-1fb0b159a7ea/0000%22> accessed 29 August 2022

69 Ibid 6.8

70 Chubby on Behalf of the Puutu Kunti Kurrama People and the Pinikura People #1 and #2 [2015] FCA 940

71 [2017] 024 of 1963 (12 Eliz. II No. 24)

72 JSCNA, A Way Forward (n 51) para 6.53

73 Ibid para 6.79–6.83

74 Noting that the WA AHA was reviewed in preceding years and there was a Bill ready to go before the WA Parliament at the time of the inquiry. It has now passed. See .

75 ‘Juukan Gorge Inquiry Hansard 12 October 2020’ (n 40) 3

76 Ibid 5; PKKP, ‘Juukan Gorge Inquiry Submission 129’, <www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Joint/Former_Committees/Northern_Australia/CavesatJuukanGorge/Submissions> accessed 29 August 2022

77 Slack, Fillios and Fullagar (n 41)

78 Michael Slack, Report of Archaeological Survey and Excavation at the Proposed Brockman 4 Syncline Project, Pilbara Region, Western Australia. Unpublished Report for Pilbara Iron Pty Ltd (2008) cited in Slack, Fillios and Fullagar (n 41)

79 R Williams, ‘Ethnographic Site Identification Survey of Brockman 4 Mine Area’ (Pilbara Native Title Service 2008)

80 ‘Juukan Gorge Inquiry Hansard 12 October 2020’ (n 40)

81 JSCNA, Never Again (n 50)

82 Quoted in JSCNA, A Way Forward (n 51) 294

83 Heather Builth, ‘Ethnographic Site Identification Survey’ (Yamatji Marlpa Aboriginal Corporation 2013)

84 PKKP (n 76) 32

85 JSCNA, A Way Forward (n 51) 295

86 PKKP (n 77) 35; JSCNA, A Way Forward (n 51) para 2.52

87 ‘Juukan Gorge Inquiry Hansard 16 October 2020’ 4 <www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Joint/Former_Committees/Northern_Australia_46P/CavesatJuukanGorge/Public_Hearings> accessed 29 August 2022

88 ‘Juukan Gorge Inquiry Hansard 21 September 2020’ 18 <www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Joint/Former_Committees/Northern_Australia_46P/CavesatJuukanGorge/Public_Hearings> accessed 29 August 2022

89 ‘Juukan Gorge Inquiry Hansard 13 October 2020’ 13 <https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/committees/commjnt/920d9c8f-4271-4084-88ae-bcffb413ce84/toc_pdf/Joint%20Standing%20Committee%20on%20Northern%20Australia_2020_10_13_8191_Official.pdf;fileType=application%2Fpdf#search=%22committees/commjnt/920d9c8f-4271-4084-88ae-bcffb413ce84/0000%22> accessed 29 August 2022; cf JSCNA, A Way Forward (n 51) 46

90 ‘Juukan Gorge Inquiry Hansard 2 November 2020’ 19–22 <www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Joint/Former_Committees/Northern_Australia_46P/CavesatJuukanGorge/Public_Hearings> accessed 29 August 2022

91 ‘Juukan Gorge Inquiry Hansard 21 September 2020’ (n 90); Yinhawangka Aboriginal Corporation, ‘Yinhawangka People Celebrate 50,000 Years of Life in Pilbara Thanks to New Evidence’ <www.yinhawangka.com.au/yirra> accessed 28 April 2022

92 ‘Juukan Gorge Inquiry Hansard 13 October 2020’ (n 90) 14

93 JSCNA, A Way Forward (n 50) 67

94 Paul Seaman, The Aboriginal Land Inquiry Report (Perth, Western Australia 1984)

95 See eg MW Game, ‘Mining and Land Rights: Letter to the Canberra Times from A/Director, Australian Mining Industry Council’ (16 December 1981); T Duncan, ‘Rights Issue Seen as Land Mine in ALP’ The Bulletin (8 May 1984) 26; J Perrett, ‘Outspoken Mine Chief Dismisses “Racist” Tag’ The Australian (4 May 1984) 7

97 Ciaran O’Faircheallaigh, ‘Land Rights and Mineral Exploration the Northern Territory Experience’ (1988) 60 The Australian Quarterly 70

98 APPEA, ‘Cutting Green Tape: Streamlining Major Oil and Gas Project Environmental Approvals Processes in Australia’ (Australian Petroleum Production & Exploration Association Limited 2013); Kurt Wallace, ‘A Simple Stimulus Step That Won’t Cost a Cent: Stop Green Lawfare’ [2020] Spectator Australia <www.spectator.com.au/2020/03/a-simple-stimulus-step-that-wont-cost-a-cent-stop-green-lawfare> accessed 29 August 2022; Sussan Ley, ‘National Press Club Address’ (16 June 2021) <https://sussanley.com/national-press-club-address-16-june> accessed 29 August 2022

99 See eg SoE, ‘Australia: State of the Environment 1996’ (State of the Environment Advisory Council for the Commonwealth Minister for the Environment 1996); SoE, ‘Australia: State of the Environment 2001’ (State of the Environment Advisory Council for the Commonwealth Minister for the Environment 2001); SoE, ‘Australia: State of the Environment 2006’ (State of the Environment Advisory Council for the Commonwealth Minister for the Environment 2006); SoE, ‘Australia: State of the Environment 2011’ (State of the Environment Advisory Council for the Commonwealth Minister for the Environment 2011); SoE, ‘Australia: State of the Environment 2016’ (State of the Environment Advisory Council for the Commonwealth Minister for the Environment 2016); SoE, ‘Australia: State of the Environment 2021’ (State of the Environment Advisory Council for the Commonwealth Minister for the Environment 2021)

100 Geoscience Australia, National Native Title Tribunal, site location research by John Burton

96 ‘Resource Statistics’ (Department of Mines, Industry Regulation and Safety) <www.dmp.wa.gov.au/Investors/Resource-statistics-1431.aspx> accessed 1 September 2022

101 See eg Jonathan Barrett, ‘WA Contracts as Mining Boom Falters: National Accounts’ Australian Financial Review (Melbourne, 5 June 2014) 11 <www.afr.com> accessed 29 August 2022

102 ‘Juukan Gorge Inquiry Hansard 2 November 2020’ (n 91) 23

103 See ; cf. ‘Mines – Operating and under Development’, Department of Mining, Industrial Regulation and Safety <www.cmewa.com.au/about/wa-resources/project-map> for mines across Western Australia as a whole.

104 ‘Juukan Gorge Inquiry Hansard 12 October 2020’ (n 40) 4

105 Ibid 4–5

106 Ibid 20

107 ‘Juukan Gorge Inquiry Hansard 13 October 2020’ (n 90) 27–35

108 JSCNA, A Way Forward (n 51) para 3.45–3.56

109 Paul Cleary, ‘Native Title Contestation in Western Australia’s Pilbara Region’ (2014) 3 International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 132; Paul Cleary, Title Fight: How the Yindjibarndi Battled and Defeated a Mining Giant (Black Inc 2021)

110 JSCNA, A Way Forward (n 50) 26–33

111 Ibid 43–44

112 Ibid 44–46

113 Ibid 46–50

114 Ibid 50–51

115 Ibid 52–54

116 Ibid 199–201

117 Refer to .

118 Caroline Bird, ‘Rockshelter Excavations in the East Hamersley Range, Pilbara Region, Western Australia’ (2021) 87 Australian Archaeology 214

119 DN Cropper and WB Law (eds), Rockshelter Excavations in the East Hamersley Range, Pilbara Region, Western Australia (Archaeopress 2018) <www.archaeopress.com/Archaeopress/Products/9781784919764> accessed 29 August 2022

120 Sean Winter, ‘Title Fight: How the Yindjibarndi Battled and Defeated a Mining Giant’ (2022) 88 Australian Archaeology 219

121 JSCNA, A Way Forward (n 50) 199–201

122 See eg Hovingh and Sinclair (n 64)

123 W Reynen, ‘Rockshelters and Human Mobility during the Last Glacial Maximum in the Pilbara Uplands, North-Western Australia’ (Unpublished, University of Western Australia 2018); K Ditchfield and W Reynen, ‘Extracting New Information from Old Stones: An Analysis of Three Quarries in the Semi-Arid Pilbara Region, Northwest Australia’ [2022] Australian Archaeology 1

124 Caroline Bird and JW Rhoads, Crafting Country: Aboriginal Archaeology in the Eastern Chichester Range, North-West Australia (Sydney University Press 2020)

125 S Wyatt-Spratt, ‘Review of “Crafting Country: Aboriginal Archaeology in the Eastern Chichester Range, North-West Australia”’ (2021) 46 Lithic Technology 164

126 ‘Juukan Gorge Inquiry Hansard 13 October 2020’ (n 90) 12–21

127 Ibid 17

128 Wintawari Guruma Aboriginal Corporation, ‘Juukan Gorge Inquiry Submission 50’ 5 <www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Joint/Former_Committees/Northern_Australia/CavesatJuukanGorge/Submissions> accessed 29 August 2022

129 Up to 2003–2004, Japan was the principal buyer. A recession in Japan 1981–1983 was likely a factor in the State Government’s aversion to changing the status quo at the time of the Aboriginal Land Inquiry (The Bulletin, ‘Japan – Australia Battles for Market Share’ (22 March 1983) <https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-1311444972/view?sectionId=nla.obj-1604894442&partId=nla.obj-1311557546#page/n76/mode/1up/search/japan> accessed 29 November 2022

130 Refer to .

131 Stark, ‘Left on the Shelf’ (n 32)