ABSTRACT

This paper presents ethnographic research from Journey: Bridging Cultures, a UK-based project that worked with school-aged youths with forced migration backgrounds. Between January 2020 and July 2021, participants and facilitators co-produced a multimedia chamber orchestra work about students’ experiences in countries of origin, transit, and destination to present to members of the Oxford community. Through this case study, we explore the translation of refugee narratives into artworks for public audiences, deconstructing the social processes and power negotiations inherent in its crafting and transmission. In conversation with scholarship on arts-based research with refugees, Michel Callon's theory of translation (1984) is mobilised to position translation as both the product and process of multiple mediations. The context of co-productive artistic creation highlights the extent to which marginalised populations shape how their narratives are translated and performed. Such participants may redirect the trajectory of an artistic project through strategies of partial- and non- engagement, but these are balanced against external influences including the parameters of the artistic medium, expectations of imagined audiences, and internalised narratives about what stories to tell.

Introduction

I came to London by plane … I came to the UK for life … I want to stay.

Students' voices in Many Worlds in One Place (2021)

Many Worlds in One Place is a multimedia chamber orchestra work premiered in 2021. It is the product of an intercultural arts project with young refugees in the UK titled ‘Journey: Bridging Cultures Through Music’ (hereafter Bridging Cultures). The 18-minute piece brings together a live string orchestra, recorded sounds and voices, and a video making use of the students’ artwork to tell a narrative about these young lives. However, no part of the story is relayed directly; each element of the work is a layered refraction. The 15-piece orchestra and recorded musical elements constitute a fusion of their favourite genres and represent aspects of their various cultural heritages, blending drill beats, samba rhythms, tabla playing, and lush string textures. Over this foundation, we hear students reading excerpts from essays written not by themselves but rather by their classmates. The orchestra accentuates and punctuates these narratives, bringing forth the same emotions conveyed in the stories. As the bright and cheerful opening section fades, two student voices declare in unison ‘we don’t just eat curry’. The bouncing samba groove is replaced by sounds of traffic and a solo violin intended to invoke imagined images of Afghanistan and Pakistan. Later on in the video, we see glimpses of the students’ artwork held at chest-level, their faces remaining out of the frame (). Extractions of colours and forms from these drawings swirl around the screen throughout the performance ().

Despite multiple mediations of their individual stories, the students nevertheless reported being able to identify themselves in the performance. A Brazilian student recognised the samba beats as her contribution; another smiled when a recording of her laugh echoed over the speakers. At the same time, the students valued the work beyond these isolated nods to their singular representations. As the one Afghan student stated, ‘This piece is not just a summary of individuals, it’s about our experiences as a group’.Footnote1 This article will endeavour to show that one needs to explore the power relations inherent in narrativising refugee experiences to unpack the nuances of crafting such a work.

This paper deconstructs the process of translating experiences of refugees to public audiences. We examine the constituent elements of this transformation through the lens of this arts-based collaborative project with refugees in the UK. Bridging Cultures was launched in 2020, spearheaded by Cayenna Ponchione-Bailey, then associate conductor for the Orchestra of St. John's (OSJ), and Toby Young, a London-based composer. Based on their previous experience in an arts-based project with refugee and asylum-seeking students in 2019, they returned to the same school with another music project.Footnote2 The project transpired over the course of six workshops and two performances from January 2020 to July 2021, with breaks imposed by COVID-19 lockdowns and school holidays. Bridging Cultures brought together a range of year-twelve students: some British-born or long-time residents who followed the school's mainstream curriculum and others new arrivals – mostly identified as refugees and asylum seekers – enrolled in the school's Steps to English Proficiency programme (STEP).Footnote3 Through the collaborative composition and performance of a multimedia orchestral piece, the project aimed ‘to generate intercultural artistic dialogue and break down social and cultural barriers’.Footnote4 These project goals not only manifested among participants in the workshops, but also in the outcomes of the translation: two performances of the resulting work – one recorded and produced for online distribution – and academic research outputs, including this publication and Young (Citation2023).

Drawing on Michel Callon's sociological framework, this article examines the process and product of this creative work as a site of translation. As the field of ‘refugee studies’ increasingly engages with participatory arts-based research practices and issues surrounding narrativisation (see Lenette Citation2019), this article analyses a specific case study to reveal the ways in which agency, representation and subjectivity are defracted through creative co-production. If ‘the dialogical nature of arts-based approaches suggests a clear pathway for Knowledge Holders to challenge damaging narratives about them in the public sphere and reclaim representations of “refugee stories”’ (Lenette Citation2019: 231), we reveal the entangled conditions under which one such pathway presented opportunities for this recovery. This project offers the ideal context for studying the transmission of refugee narratives. The myriad actants used diverse means to negotiate control over the translation, meaning that power and roles were distributed and clearly delineated, presenting an ideal avenue to explore the principles underlying translation. In narrativising refugee experiences, the problem of who speaks for whom requires a critical look at power relations. We hope to offer one such way to do so.

Determining whether the final result faithfully represented the students’ experiences is not the goal of this paper. Similarly, we do not investigate the impact of the interventions or the artistic work on refugees’ well-being, asylum procedures, or media representation. Although we consider the role of the imagined audiences throughout the translation process until the point of its final mobilisation, no audience research has been conducted, and we do not explore the reception of the translation. Instead, the focus is on collaborative artistic processes and products, understanding ‘products’ not as a static objects but sites of translation. By interrogating the minutiae of collaborative crafting in the context of shifting project objectives, this article maps how Bridging Cultures’ various actants negotiated the decoding and recoding of experiences in translation.

Methodology

This research utilised ethnographic methods to facilitate an intersubjective ‘correspondence’ between researchers and actants, deriving knowledge-creation out of an intentional co-presence (Ingold Citation2014). The first author and research assistants attended nearly all workshops and performances over the span of 18 months. These researchers observed the evolution of the project, from its inception to final performances. Importantly, Bridging Cultures was designed to include a research element from the outset, with researchers working alongside the facilitators but with a distinctive agenda: to interrogate the co-productive artistic process, enabling reflexivity both during and after the project. To this end, researchers also developed rapport with the students, with these foundational relationships necessary to gain insights via participant-observation and semi-structured interviews. Other data collection methods included participant diary-keeping and video, photo, and music analysis.

In the second month of the fieldwork, COVID-19 forced us to revise our data collection strategies. We adapted, along with the rest of the project, to a hybrid format. These innovations yielded additional insights about research with forced migrants and the paradox of proximity when imbalanced power relations are mediated via technology. This finding is beyond the scope of this paper, but opens up avenues for future research into remotely delivered co-produced arts projects with forced migrants.

Of relevance to the focus of this research, the presence of the researchers as active members in the artistic stream of the Bridging Cultures project undoubtedly shaped the trajectory of the translation. Indeed, the translation continues in the write-up, revision and dissemination of this paper, only reinforcing that it is an emergent product and process.

Music and Arts Participation among Young Refugees and Asylum Seekers

In their report of a national survey conducted across the UK, Kidd et al. (Citation2008) characterised the range of social objectives underlying arts participation in refugee communities as follows: social and community cohesion, capacity-building in participants, or challenging negative representations. Although these aims are difficult to disentangle and mutually constitutive, the literature specific to music and arts participation among refugee and asylum-seeking children and youths focuses more strongly on the first two objectives. For example, art and music therapies and community music projects have been found to help asylum-seeking youth generate connectedness and provide a source of wellbeing (Pesek Citation2009, Storsve et al. Citation2012, Lenette and Sunderland Citation2016, de Quadros and Vu Citation2017, Dieterich-Hartwell and Koch Citation2017), facilitate emotional expression and acculturation (Krensky Citation2001, Jones et al. Citation2004, Lenette Citation2019, Vougioukalou et al. Citation2019, Kalsnes Citation2021), and convey political protest (Lenette Citation2019). Other research has analysed the incorporation of diverse music curricula into schools which have high populations of refugee and asylum-seeking youths (Fock Citation2009, Foramitti Citation2009, Karlsen and Westerlund Citation2010, Marsh Citation2012, Karlsen Citation2013, Crawford Citation2017, Citation2020), impacting confidence and fostering cultural connectedness, bridging home and host cultures. Outside of school music lessons and formal, interventionist music programmes, children and young people who have experienced forced displacement are agentive social actors who utilise music towards these ends in the context of their own, autonomous music practices (Dieckmann and Marsh, in press, Marsh Citation2012, Citation2012, Citation2017, Marsh and Dieckmann Citation2017, Marsh et al. Citation2020).

The relationship between agency, cohesion, wellbeing, and capacity-building is central to collaborative projects that work towards the development of public-facing art, where issues of representation are particularly salient. Here, negotiations of representation coalesce around the discursive figure of the refugee, as distinctive notions of refugee-hood and ‘the refugee experience’ are consolidated or challenged through processes of narrativity and performance. Refugee life narratives have emerged as performative genres problematically shaped by the climate of local and global human rights campaigns and the structure of asylum laws. Such narratives have been examined in various forms – including autobiographical histories (Helff Citation2009), legal testimonies (Vogl Citation2013), and theatrical works (Cox Citation2012) – revealing the genre's discursive framing of notions of victimhood, hope, authenticity, agency, healing, and identity. On the one hand, it has been argued that narrative documentation is a powerful tool when working with refugees in trauma therapy (Burns Citation2015) and in response to exclusionary and hostile media coverage (Leudar et al. Citation2008). At the same time, ‘people who have experienced forced migration can feel frustrated by the constant focus on only one aspect of their identities, as this can lead to ignoring their resilience, contributions, and talents’ (Lenette Citation2019: 13). Indeed, it has been suggested that public, institutionalised performances of such testimonial narratives reinforce the speaker's marginalisation (Kisiara Citation2015). Intentions underlying co-creative arts practices recognise the ethical dilemmas of representing refugees’ voices and the importance of centring those that are represented in the framing of discussions (Lenette et al. Citation2015, Fairey Citation2018, Lenette Citation2019). Other projects address the issue by refusing to narrativise refugee-hood, such as the collaborative sound essay discussed by Western, wherein the ‘focus was more on the city – on movement and circulation – than on “THE SOUNDS OF REFUGEES” or something equally exoticizing’ (Citation2020: 298).

The current study contributes to this growing body of research that interrogates the processes through which refugees’ experiences become artistic or practice-based research outputs, many of which aim to challenge negative representations. Following Blomfield and Lenette’s (Citation2018) autoethnographic analyses of their collaborative filmmaking project, this article serves as a reflexive device for the participatory arts-based project under examination. By articulating the logistical and ethical deliberations that unfolded in practice, we highlight the complications involved in realising the principles espoused by the authors, particularly that of collaboration and negotiating the politics of editing. If collaboration can ‘reveal the idiosyncrasies and nuances of refugee experiences’ (Western Citation2020: 334), providing ‘a way of wilfully complicating things’ (305), the transmission and representation of these experiences, whether through art or other means, requires a form of mediation.

Theorising Translation

Regardless of efforts to decentre authorship and distribute creative agency, a story's character changes when represented by others. Mediators inherently ‘transform, translate, distort, and modify the meaning of the elements they are supposed to carry’ (Latour Citation2005: 39). These principles extend to the creative outputs themselves; as carriers of meaning, non-human actors such as musical works shape how the artists’ intended (or unintended) message is transmitted to and received by the audience. This relationship between music and socially-constructed meaning is reflexive: ‘Just as music’s meanings may be constructed in relation to things outside it, so, too, things outside music may be constructed in relation to music’ (DeNora Citation2000: 44).

Our aim is to theorise this mediation – the exchanges amongst human and non-human actors – as a form of translation. Within the broader concept of cultural translation, the movement of persons, objects, and ideas plays a critical role in shaping the transmission of meaning (Bhabha Citation1994, Clifford Citation1997, Pym Citation2010). The sociology of translation, relying heavily on Actor-Network Theory, approaches this process as a study of power relations. Here, the translation process includes ‘all the negotiations, intrigues, calculations, acts of persuasion and violence’ that generate the authority to speak on behalf of another (Latour and Callon Citation2014: 279). Callon’s seminal 1984 paper on the study of scallops in the St. Brieuc Bay positions this argument in relation to the scientific method, but this process can apply to knowledge transmitted more broadly, such as through artistic media. Indeed, the paradigm of translation as power relations has taken increasing influence in music (DeNora Citation2003, Hennion Citation2010) and literary translation studies (Renn Citation2006, Buzelin Citation2007, Bachmann-Medick Citation2009).

The strength of this approach lies in its foregrounding of the negotiations needed to craft and present a symbolic representation. Callon delineates the process in four stages. In ‘problematization’, actors are defined and alliances are formed around a common goal. In ‘interessement’, actors negotiate relational identities to each other and the project. Through ‘enrolment’ the duties and expectations of the actants are solidified.Footnote5 And finally in ‘mobilisation’ a small number of individuals speak on behalf of the assemblage. Through these four stages entities are ‘displaced’: actors are symbolically taken from their original position and represented in the translation by a spokesperson.

While this act of displacement risks perpetuating violent misrepresentation, especially in cases with forced migrants and other marginalised groups, these individuals are not powerless in the negotiations. Callon lists ‘physical violence, seduction, transaction, and consent without discussion’ (Citation1984: 214) as tactics of grabbing power in translation theories. But we argue here that stakeholders can also exert power through non-engagement, selective divulgence, and a broader set of ‘weapons of the weak’ (Scott Citation1985). The multiple bridges between stakeholders can be formed in such a way that endows all constituents with a certain basis of power; if one pillar in the translation does not bear its weight, the entire structure may collapse.

Therefore, we will reframe Callon’s theory of translation not as a teleological four-step struggle for hegemony, but rather as an emergent negotiation for representational power. As the paper will show, that these processes of negotiation operate at every stage does not erase the presence or influence of power differences. These diffuse power structures have long been acknowledged in arts-based research practices; indeed they constitute part of the rationale for such methods. Foster (Citation2015) identifies that artistic outputs are ‘co-constructed through turn-taking, adding, embellishing, and polishing’, and that ‘narratives are never neutral but rather depend on the positionalities – that plethora of intersecting factors – of not just the teller, but also the reteller and the audience’ (34). On participatory video production with refugees specifically, Lenette confirms that ‘the promise of “empowerment” … does not preclude the need to engage critically with inherent power dynamics’ (Lenette Citation2019: 219). An important addendum to these arts-based practices borrowed from Callon is the role of non-human actants; as a mediator, the artistic work itself plays a critical role in realising, or potentially undermining, the intended message.

Building on these two fields, this article aims to expand Callon’s theory of translation through heightened attention to the landscape of power relations: how each translational stage in Bridging Cultures was impacted by positional jockeying and shifting relationalities within the network. In turn, translation theory offers due recognition of the roles of all actants in translational processes, magnifying the impact of non-human entities in arts-based co-production. This will be presented in the three phases of the project: the initial problematization and recruitment, the restructuring of roles during the COVID-19 lockdown, and the mobilisation of diverse stakeholders in the performance of the translation.

Phase One: Initial Approach and Stakeholder Negotiations

The next group work discussion question was announced: ‘What should people know about the country you’re from?’ My stomach clenched – we hadn't talked about their lives before coming to England yet. S1 and S2, who both left Syria in 2014, are reticent while S3 gushed about everything he liked about Oxford. I acknowledged his contribution, but nudged him in the direction they meant: ‘And what about Eritrea?’ His grin wavered. ‘I was young when I left, I don't remember’. S4 – white, family ‘probably here since the Norman conquest’, as he said – shrugged and mumbled, ‘This question isn't really for me’. (Author 1 fieldnotes, Workshop 3, 4 March 2020)

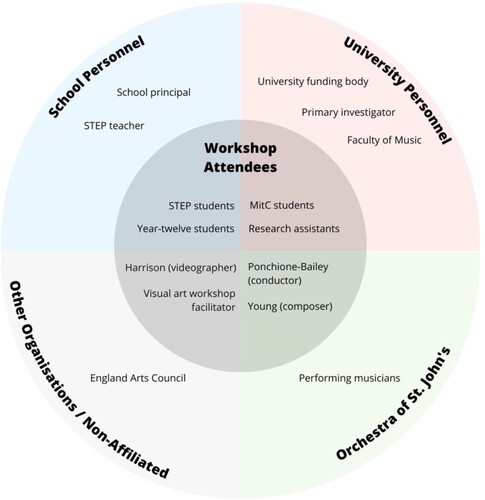

The performance described at the article's open comprised Bridging Cultures’ primary goal, yet each stakeholder had their own objectives. As seen in the fieldnotes excerpt above, different groups served various roles that needed to be worked out and established in the initial meetings. gives an overview of the stakeholders in this project.

Alongside Ponchione-Bailey and Young, three University of Oxford undergraduate students and two graduate research assistants (including the first author) helped facilitate the workshops. These undergraduate students participated as part of a course titled ‘Music in the Community’ (hereafter MitC students), convened by the second author, for which they were expected to write a paper based on their experiences. The research assistants attended the sessions with the goal of collecting and analysing data and ultimately disseminating research. Beyond those present at the workshops, the funding bodies also imposed restrictions and expectations. Drawing support from Orchestra of St. John's (OSJ), the University of Oxford, and the Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities, the project balanced diverse priorities about musical output, social outcomes, and community impact. Administrators and teachers at the host school shaped the programme to fit within its structure, including how and when facilitators could interact with the two groups of students. The year-twelve and STEP students themselves spent considerable time, both in and out of the workshops, to develop a piece that was meant to represent their lives and heritages. However, their investment and engagement in this representation became a source of tension.

Callon’s first two stages of translation – problematization and interessement – establish the terms on which a translation process is undertaken. As project leaders, Ponchione-Bailey and Young faced the task of recruiting members and forging a new ‘system of alliances or associations’ to reach their objective (Callon Citation1984: 206). In Callon's formulation, researchers discover a problem in the world which forces the engagement of relative stakeholders. This approach does not acknowledge issues of framing inherent in problematization. In seeking to co-produce knowledge, the paradigm used will not only shape the project's questions but also the answers. This is of particular concern in refugee studies, where Lenette advocates researchers ‘relinquish the question-asker role and enter space alongside Knowledge Holders, listening intently to the ways they choose to articulate their lived experiences’ (Citation2019: 127).

The framing of the problem is important, as it lays the groundwork for the second stage of Callon's translation. In ‘interessement’, relational identities emerge from each entity's role in the group. As Callon notes, some actors must use their position of power to ‘impose and stabilize the identity’ of others with regards to the problematization (207). Here the programme structure as laid out by Ponchione-Bailey and Young defined these identities within the context: the students supplied the content for the musical piece and the facilitators processed it for outward presentation. But as shown in the ethnographic vignette above, this role was not wholly accepted by the students. Although facilitators hoped to draw out the diversity of cultural heritages within the classroom and recognise their equal value, after the first two sessions, they noted that this approach paradoxically limited student interessment in the project. The white British students reportedly did not feel addressed by the questions, and the STEP students chose to articulate other lived experiences than those asked.

These hurdles posed a challenge to framing the project: how could this chosen problematization be adopted without engaging the most relevant stakeholders? As Ponchione-Bailey noted, ‘it was clear to me that we were unsuccessful in conveying what this opportunity was and the agency that they [the students] had to shape it’.Footnote6 To overcome the preponderance of one-worded answers in the first workshop sessions, facilitators altered the programme to suit the perceived interests and abilities of the two student groups. Ponchione-Bailey and Young restructured their appeals for participation, reworded questions, developed visual aids, and created a new presentation about the final product to motivate the students. The research team used similar tactics. After a series of generic responses in the student reflections, we offered more diverse ways for students to record their thoughts, including writing, drawing, typing on their phones, and talking with facilitators.

While the top-down problematization of the project seemingly circumscribed participants’ influence, the students, including those with limited English skills, nevertheless shaped its course. As Callon comments, the ‘devices of interessement create a favourable balance of power’ even for those who may be otherwise marginalised (Citation1984: 211). While the asylum-seeking students did not often express their protest with words, their non-engagement prompted facilitators to seek alternative ways of generating investment in the project. Instead of relying exclusively on group discussion, Ponchione-Bailey and Young invited the students to respond with drawings, multilingual texts, videos, and the sharing of online media to represent their experiences. These responses diversified the means for student engagement beyond English-language anecdotes in group discussions. Ross Harrison, videographer and workshop facilitator, reflected on this addition at a later workshop:

They [the students] just got involved straight away. I think it was quite an intuitive, interactive process that people could get engaged with quite quickly and just spontaneously respond to what was going on without the need for talking.Footnote7

The facilitators, recognising the increased engagement that this approach seemed to generate, continued to offer multi-modal response options throughout the workshops. Viewed through the paradigm of Callon's stages of translation, this shift shows the power STEP students wielded via non-engagement to prompt creative means of interessement. In this way, silence is ‘not just a politics of domination and non-participation-–silence is a strategy to respond to situations of conflict; silence is a creative tool […] Silence can also be agency’ (Western Citation2020: 304). Subversive non-engagement calls for the kind of political listening arts-based methods require in refugee research, that which faces dissent, embraces discomfort and exercises power diffusion (Lenette Citation2019).

While Callon notes the equitable power distribution that this process creates, the problematic at the heart of this translation was nonetheless primarily dictated by Ponchione-Bailey and Young. In these interactions STEP students retained more decision-making power than might be expected in such a project; nevertheless, the role assigned to them based on their previous experiences and skillsets limited the scope of identities they may have adopted. With the goals and relational identities settled through the process of problematization and interessement, the following section will examine how roles were formed amidst the instability of 2020.

Phase Two: Responding to Remote Requirements during COVID-19

In the first workshop using distance learning methods, three female Brazilian STEP students and one young Afghan woman who has lived in the UK for a number of years spoke to us through a video call on the laptop. Instead of talking about ‘musical heritage’ as in previous sessions, the MitC facilitator for this group was tasked with gathering ideas and concepts the students wanted to be represented. The facilitator posed a carefully-worded question: ‘which emotions would you like to convey in your part of the musical work?’ The STEP students, previously looking at the screen, turned to expectantly look at the young Afghan woman with them in the classroom. She took the MitC student's deliberately open prompt and reformulated it as such: ‘what did you feel in your home country, and what did you feel when you got here?’ While this might have been the underlying question of the exercise, none of us facilitators felt comfortable necessarily framing it in such a direct, reductive way. (Author 1 fieldnotes, workshop 4, 25 November 2020)

This scene illustrates the many mediations and exchanges that took place within the Bridging Cultures project. The constellation of these micro-negotiations gave rise to the larger exchanges which formed the basis of this translation. In phase two of the project, new challenges and a shifting set of ‘interessed entities’ recast the problematization, roles, and means of representation in a different light.

Measures to combat the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020 put the programme on hold. When students returned to school, the project resumed in November 2020 in hybrid format, with all but one facilitator joining the programme remotely via a video calling platform. In addition to rebuilding relationships with students at a distance, facilitators needed to contend with the technology as an additional entity in the translation process, the influence of which could be seen in broken internet connections, the framing of the camera angle, and audio delays and echoes.Footnote8

In this second phase from November to December 2020, external changes to the context forced a shift in both the project's problematization and interessement. In addition to social-distancing restrictions between classes, many year-twelve participants finished school in 2020. As a result, the programme was restricted to just STEP students. The loss of a key participant group weakened the position of the enrolment tactics; the dialogue between classes and backgrounds could not be fulfilled as originally intended. Instead, facilitators forged a new framing for the project focused on the individual students’ journeys and the emotions they wished to convey through the artwork. This new approach reinforced the outward orientation of the project: the final artistic output was now aimed at translating these experiences for concert audiences, not necessarily amongst the students themselves. In fact, the original plan of fostering intercultural dialogue could have continued under these new conditions, as the programme still included students from different cultural backgrounds within the STEP programme.Footnote9

The enrolment process also saw facilitators tapping into STEP students’ pre-existing expertise, namely that of language competencies. Out of this new structure emerged a class of ‘young interpreters’, as they were called: STEP students who had lived in England the longest and were comfortable communicating in English as well as other languages. Unlike the project's previously language-blind policies that sought to downplay differences, in this phase the facilitators worked with the STEP teacher to create language-based working groups. Young interpreters took on a quasi-facilitating role as mediators between workshop leaders on the screen and participants in the room.

This role of the young interpreter introduced ‘closeness’ as a theme in the network, both in terms of physical proximity and perceived similarity. As illustrated in the ethnographic vignette at the beginning of this section, the young interpreters played a crucial role in bridging the gulf between facilitators and other STEP students. This applied not only with regards to age, gender, experience living in England, and knowledge of the school, but also with physical proximity: they sat together in the classroom while facilitators were confined to laptop screens.

The interpreter role also held a symbolic meaning; in these instances, young interpreters rephrased and shifted the emphasis of a statement in English to clarify the underlying message for the intended recipient. This could mean simplifying the vocabulary, using culturally-relevant terminology, or even imbuing it with the inflection and codes of youth communication styles. They were not just passive intermediaries – they shaped the message as they transmitted it. In the above example, the MitC facilitator went to great lengths to keep the questions as open-ended as possible. But the young interpreter, having participated in a number of such programmes ‘for refugees’ herself, projected what sort of answers she thought were expected and reframed the questions to generate these results. The facilitators were not the only ones crafting the narratives. Students’ life stories had already been shaped by their previous experiences with the asylum system, media consumption, and internalised institutional expectations. As described in the quote below in reference to differently-abled people, refugees and asylum seekers are often,

expected to tell and retell traumatic stories, stories of the worst things that happened to them, in order to have maximal political effectivity. Applying for accommodation from welfare or educational systems often requires narrating one's areas of difficult or incapacity, and one's most difficult moments. Particular stories are ‘coaxed’ here by the requirements of particular listeners – or even by the expectation of particular kinds of listening on the part of listening storytellers alert to particular genres of story and types of narrative (Matthews and Sunderland Citation2017: 183).

These encounters, shaped by the varying expectations and interests in the project, illustrate the dynamic process of enrolment. With the new problematization and interessement with the STEP-only participant group, entities needed to reconfigure their position with one another in relation to the overarching goal. The enrolment process is not without conflict as it encompasses the ‘multilateral negotiations, trials of strength and tricks’ to determine roles and contributions (Callon Citation1984: 211). The number of interessed entities in this project yielded quite a few points of negotiation: Ponchione-Bailey and Young struggling with the school to have more in-person time with the students, MitC students needing enough material for their essays, remote facilitators navigating technical difficulties, the researchers jockeying for access to the students, the videographer canvassing for material, and the STEP teacher protecting the emotional wellbeing of the students. One could add the role of the COVID-19 pandemic to this assemblage; protection from the virus demanded social distancing when these entities most needed to come together in the workshops.

These power relations within the project became more codified in the next phase as the artistic work was forged. The goal of narrative formation will shape not only how students and facilitators position themselves in the network, but also how they are represented externally to the public.

Phase Three: Speaking in the Name Of

[The piece] is just so open in terms of translation, so my concern was about essentialising: what are we saying? We were dealing with bits and bobs from each of these young people and trying to put something together that they could feel themselves reflected in a positive, yet still poignant way … that they actually felt celebrated and appreciated and important in that space at that time. But we also wanted to make sure that we didn't miss the opportunity to convey them to the public audience. So it was an audience question, right? Who were we speaking to? Is this piece just for them? Is this piece trying to bridge a communicative potential or imagined communicative gap between them and the community? (Interview with Ponchione-Bailey 1 July, 2021)

This final section will consider the ‘mobilisation’ of the translated object to its target audience, in this case the school and the broader community. In the summer of 2021 two concerts were held in Oxford: one in the school for students and staff and another in the Oxford city centre for the public. The project leaders hoped to present the co-produced piece to not only to the students’ peers, but also to the wider community. These two premieres had been planned since the project's inception. Therefore, this imagined audience was silently addressed throughout the workshops and in the crafting of the artistic work.

Within this act, issues arise as to who is speaking for whom, especially when working with forced-migrant youths. This stage of Callon's trajectory foregrounds the role of the final mediator: one who speaks and acts on behalf of others. Callon's use of the anthropocentric term ‘spokesperson’ conflicts with his heretofore commitment to more-than-human actants. In this case study, the art itself – sheet music, instruments, sound waves – is critical to the mobilisation of the translation. Replacing ‘spokesperson’ with ‘actants’ not only brings in non-human entities, but also draws attention to the multiple forces mediating the translation to external audiences.

Callon illustrates the mobilisation step as a scientific presentation – a formal, one-person delivery of an agreed-upon message with a singular meaning and interpretation. Here we propose that mobilisation is more akin to a collaborative performance with many actants and a multiplicity of possible interpretations. The transmission of a message does not occur at an isolated point in time; it unfolds dialogically through the course of crafting and interpreting the translation in response to the audience and the other performers.

This process is made concrete in the description of the performance at the beginning of the article in which the actant's role is defracted and abstracted. In this case, who or what can claim to be an actant?: the musicians, conductor, videographer, art teacher, students, sheet music, video, and the sounds themselves all perform part of the translation. Instead, could it be the co-constructed knowledge itself that is the ultimate actant? This abstracted representative form of these young people's experiences has indeed been shaped by all the enrolled entities; through the many iterations of collaboration, this final product has reached consensus by the interessed groups, fulfilling Callon's understanding of the actant.

Each of the entities involved in performing the translation will be profiled here. By complicating the unidirectional relationship between project members and the audience, the blended expectations and obligations of the various entities clarify the dialogic process of performing a translation. This bifocal gaze, encompassing both the positionality of the interessed entities and the addressed audience, sheds light on the practical, creative, and personal decisions made in crafting this project's final outcome. In the end we hope to show that after all the prior negotiations leading up to the concert, the translation itself only emerged through the act of performing it.

First, we will consider the receivers of the message. While those involved in the project differed in their motivations, the target audience of the translation remained constant. Throughout, students were prompted by questions such as ‘what do you want to present to other students in the school?’ or ‘what should people in Oxford know about your home country?’ In targeting both students and the concert-going public (divided by age, socio-economic status, nationality, and ethnicity, to name a few factors), the music was tasked with producing the desired emotional effect across widely divergent receiving populations. This imagined terminus of the translation process shaped the timbre of delivery.

With this majority-English listenership in mind, Young's composition mediates the students’ experiences in modalities that were anticipated to resonate with these audiences. As Ponchione-Bailey said after the concert, Toby's music is ‘just likeable’: these palatable soundscapes and pleasant resolutions likely engendered an empathetic response to the students represented in the narrative. Confined by the limited material students contributed and parameters set by funding bodies, ‘it is sometimes inevitable that artists may fall into the trap of creating stories that reflect their perspectives or perceptions of what audiences want to see, rather than remaining faithful to the wishes of the protagonist(s)’ (Lenette Citation2019: 217). In this way, the audience for a translation exerts considerable power over how the artistic work emerges, well before it even reaches the stage. This imagined audience has been an actant in the project since phase one, complicating previous attempts to redistribute power relations.

However, to assert that the audience totally determined Bridging Cultures’ representation of the STEP students would be a mischaracterisation. The myriad actants, with their own objectives and concerns and – in the case of non-human actants – configurations, simultaneously afforded and limited the means by which the performance of this translation could develop. First of all, while the composition may have been crafted across many iterations and discussions, the actualisation of the sounds relied on a faithful performance by the orchestra. To this end, the professional musicians who joined the project in the final stages brought with them critical expertise to translate the message, yet they lacked the experience of co-production with the STEP students. This disjuncture generated moments of friction, especially regarding musical styles unfamiliar to the ensemble. As Ponchione-Bailey reported, the OSJ musicians initially struggled to find ‘the groove’ within this ‘musical montage’: ‘I think it was intimidating to try and wear musical cultures that they were not steeped in – to groove in a Brazilian beat but then groove in a drill beat’.Footnote10

The demand for safety and sensitivity for individual STEP students also shaped how they were anonymously presented. In the performance, students were distanced from the final representations by their textual and artistic responses. Competing tensions arise when considering the maintenance or erasure of storyteller identities in these contexts. Lenette argues for the former ‘as an assertion of agency and as a way of preventing further dehumanisation of people from refugee and asylum seeker backgrounds through institutional demands for de-identification and anonymity in all circumstances’ (Citation2019: 136). In Bridging Cultures, the decision to anonymise was guided by institutional safeguarding concerns and aided by the defracted nature of the material collected in the initial workshops. As illustrated in the first ethnographic vignette, students were asked about their countries of origin and destination. The collected responses were curated and edited by the facilitators and then read aloud and recorded not by the initial contributor, but instead by another participant. These final recordings were then interwoven into the sonic fabric of Young's composition.

To facilitate engagement that could nonetheless be anonymised, students created artwork in response to the musical composition. Guided through the process by a professional artist and workshop facilitator, the STEP students created two-dimensional works with markers and paper to stand in as their person in the video. Additionally, the artworks were not simply added to the film without some form of transformation; Harrison extracted elements and forms from the work to frame the orchestra and give movement to the visuals (). Once again, the imagined concert audiences guided the translation of the material. To fulfil the requirement for an 18-minute film to match the length of the composition, Harrison extended and transformed the artworks to evoke and augment the desired emotional response in concert with the music. Similar to Young, Harrison generated an artwork from limited material input from the students, necessitating his primacy in the creative decision-making process. However, in reaching the final goal of the project to convey these students’ narratives in an affective way, both Young and Harrison's professional experiences addressing similar audience groups ultimately mobilised the translation.

Indeed, the connection between translators and audiences embodies yet another fluid, dynamic relationship over the course of the translation process, not just in its final mobilisation. The defracted nature of the spokes-acting is mirrored in the constellated nodes that form the addressed audience; each of the stakeholders took on the role of performer and audience alternatively throughout the project. The STEP students initially performed their narratives, which the facilitators and students reinterpreted and reconfigured over multiple mediations until the final artistic outcome was presented back to the students. As evidenced by the student reflection quoted in the introduction, the piece could be seen not just as ‘a summary of individuals’, but rather as a reflection of the group as a newly-formed entity in itself. After all, the process of translation ‘is not just about putting a story together for an audience; at times, the most important audience member may be the storyteller her/himself’ (Lenette Citation2019: 127).

Conclusion

This final product – the multimedia orchestral work Many Worlds in One Place – took form over the course of 18 months in workshops, stakeholder meetings, rehearsals, and finally two public performances. But the work does not sufficiently represent the entirety of the translation. Tracing the trajectory from start to finish, this translation must be viewed as simultaneously product and process. The relations between entities did not progress linearly, nor were they fixed; they shifted, double-backed, and cycled in response to individuals’ interests and objectives, as well as external stimuli. For example, recognising the STEP students’ communication needs, the facilitators added the roles of young interpreters and videographer to the project in phase two. Different groups of project actants, along with the artworks itself, switched back and forth between performer and audience member. Initially, STEP students were asked to produce their own narratives they wished to share with the community. As the workshops progressed, these stories were retold through drawings, videos, musical representations, written texts, and spoken performances.

Given this dynamic process involving exchanges between a number of stakeholders, the project's theme of ‘building bridges’ aptly illustrates our approach to cultural translation: instead of a unidirectional transmission of meaning, this project produced multiple avenues of connection between project actants (including the artistic works) and publics. The act of bridge-building facilitates travel between two points of crossing where there is a strong need for connection. Exchanges may have previously transpired, but the bridge opens up new modes of mobility and connectivity that did not exist in that form previously. This conception mirrors the process of interessement and enrolment; stakeholders’ multifaceted identities are necessarily reduced and pinned down for the purposes of this construction, codified in agreements between the interessed. Yet, once a connection is made, channels of exchange flow in both directions and travel beyond its endpoints. Thus the translation itself does not stop once it reaches the other side – it continues to transform and address new audiences in future mediations.

Applying Callon's four-step process of translation to Bridging Cultures brings to the fore the negotiations, frictions, and transformations inherent to the task. Considering problematization, interessment, enrolment and mobilisation in turn draws attention to distinctive points in the translation process. Further insights arise when a network of actants is deconstructed into its constituent, dynamic roles and responsibilities. If these are always in flux, then Callon's analytical framework provides a snapshot of key relationships at significant moments, within which shifts or ruptures may occur.

Callon's casting of translation work as a raw power struggle is nuanced here; the context of co-productive artistic creation highlights how even those with seemingly little power can influence a project's trajectory. Actants from often-marginalised backgrounds shaped the terms of engagement and contributed additional skills and experiences that were crucial to the creation of the final artistic output. At the same time, the urge to redistribute power relations, especially in artistic projects with forced migrants, must confront expectations imposed from beyond – expectations from audiences, as well as internalised narratives about what stories to tell. Importantly, Journey: Bridging Cultures’ multiple relations were not just limited to human-to-human interactions; the artistic media shaped and were shaped by these encounters. In the end, the sum of these mediations forged the building of this intercultural bridge, a process and product of translation.

Ethics Approval

This research received ethics approval from the University of Oxford Central Research Ethics Committee reference R67601/RE001

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank research assistants Samuel Fouts & Jessica Edgars for their dedicated work on the project. We thank all members of the Journey: Bridging Cultures project for an interesting exchange and fruitful artistic experience.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Interview with students 2 July 2022.

2 In the ‘Displaced Voices Project’, four young people with forced migration backgrounds worked with Ponchione-Bailey and Young to create an orchestral ‘backing track’ to their spoken word pieces. For more information on this project, see https://www.osj.org.uk/listening-to-displaced-voices/

3 The host institution is a mixed sex, state-funded secondary school, with students aged 11 to 19, run by an academy trust (not-for-profit company). The school caters especially for newly arrived students of this age range – having often moved to the UK as forced migrants – with a custom course entitled Steps to English Proficiency (STEP), involving English, Math, Science and English as an Additional Language.

4 Project funding application, 2019.

5 We use actants in this paper instead of actors to foreground the non-human entities shaping the trajectory of this project.

6 Interview with Ponchione-Bailey, 1 July 2021.

7 Interview with Harrison, 8 July 2021.

8 While other studies have and surely will explore the full impact of digital communication on music education projects in the COVID-19 pandemic (Daubney and Fautley Citation2020, Nichols Citation2020, Rivas et al. Citation2021, Shaw and Mayo Citation2022), this section will primarily focus on how the human actants responded to these ruptures within the network.

9 Music projects in which minoritisation is foregrounded usually work to promote interculturalism or facilitating resettlement and integration (see Marsh and Dieckmann Citation2016, Dieckmann and Davidson Citation2018, Campion Citation2021).

10 Interview with Ponchione-Bailey 1 July 2021.

References

- Bachmann-Medick, D., 2009. Introduction: The Translational Turn. Translation Studies, 2 (1), 2–16.

- Bhabha, H.K., 1994. The Location of Culture. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Blomfield, I., and Lenette, C., 2018. Artistic Representations of Refugees: What is the Role of the Artist? Journal of Intercultural Studies, 39 (3), 322–338.

- Burns, C., 2015. “My Story to be Told”: Explorations in Narrative Documentation with People from Refugee Backgrounds. International Journal of Narrative Therapy & Community Work (4), 26–39.

- Buzelin, H., 2007. Translation “In the Making”. In: M. Wolf and A. Fukari, eds. Constructing a Sociology of Translation. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing, 135–170.

- Callon, M., 1984. Some Elements of a Sociology of Translation: Domestication of the Scallops and the Fishermen of St Brieuc Bay. The Sociological Review, 32 (1), 196–233.

- Campion, R., 2021. The Field of State-funded Music Programmes with Forced Migrants in North Rhine-Westphalia: Promises and Pitfalls. Ad Marginem, 93, 25–47.

- Clifford, J., 1997. Routes: Travel and Translation in the Late Twentieth Century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Cox, E., 2012. Victimhood, Hope and the Refugee Narrative: Affective Dialectics in Magnet Theatre’s Every Year, Every Day, I am Walking. Theatre Research International, 37 (2), 118–133.

- Crawford, R., 2017. Creating Unity through Celebrating Diversity: A Case Study that Explores the Impact of Music Education on Refugee Background Students. International Journal of Music Education, 35 (3), 343–356.

- Crawford, R., 2020. Socially Inclusive Practices in the Music Classroom: The Impact of Music Education Used as a Vehicle to Engage Refugee Background Students. Research Studies in Music Education, 42 (2), 248–269.

- Daubney, A., and Fautley, M., 2020. Editorial Research: Music Education in a Time of Pandemic. British Journal of Music Education, 37 (2), 107–114.

- DeNora, T., 2000. Music in Everyday Life. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- DeNora, T., 2003. After Adorno: Rethinking Music Sociology. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- de Quadros, A., and Vu, K.T., 2017. At Home, Song, and Fika–Portraits of Swedish Choral Initiatives amidst the Refugee Crisis. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 21 (11), 1113–1127.

- Dieckmann, S., and Davidson, J.W., 2018. Organised Cultural Encounters: Collaboration and Intercultural Contact in a Lullaby Choir. The World of Music, 7 (1/2), 155–178.

- Dieterich-Hartwell, R., and Koch, S.C., 2017. Creative Arts Therapies as Temporary Home for Refugees: Insights from Literature and Practice. Behavioral Sciences, 7 (4), 69.

- Fairey, T., 2018. Whose Photo? Whose Voice? Who Listens? `Giving,’ Silencing and Listening to Voice in Participatory Visual Projects. Visual Studies, 33 (2), 111–126.

- Fock, E., 2009. Experiences from a High School Project in Copenhagen: Reflections on Cultural Diversity in Music Education. In: B. Clausen, U. Hemetek, and E. Sæther, eds. Music in Motion: Diversity and Dialogue in Europe. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, 381–394.

- Foramitti, C., 2009. Intercultural Learning in Dialogue with Music: Everybody is Special – Nigerian Music Project at an Austrian Kindergarten. In: B. Clausen, E. Sæther, and U. Hemetek, eds. Music in Motion: Diversity and Dialogue in Europe. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, 347–357.

- Foster, V., 2015. Collaborative Arts-based Research for Social Justice. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Helff, S., 2009. Refugee Life Narratives: The Disturbing Potential of a Genre and the Case of Mende Nazer. Matatu, 36, 331–346.

- Hennion, A., 2010. Loving Music: From a Sociology of Mediation to a Pragmatics of Taste. Revista Comunicar, 17 (34), 25–33.

- Ingold, T., 2014. That’s Enough about Ethnography! Hau. Journal of Ethnographic Theory, 4 (1), 383–395.

- Jones, C., Baker, F., and Day, T., 2004. From Healing Rituals to Music Therapy: Bridging the Cultural Divide between Therapist and Young Sudanese Refugees. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 31 (2), 89–100.

- Kalsnes, S., 2021. Developing Craftsmanship in Music Education in a Palestinian Refugee Camp and Lebanese Schools. In: K. Holdhus, R. Murphy, and M.I. Espeland, eds. Music Education as Craft: Reframing Theories and Practices. Cham: Springer, 133–149.

- Karlsen, S., 2013. Immigrant Students and the “Homeland Music”: Meanings, Negotiations and Implications. Research Studies in Music Education, 35 (2), 161–177.

- Karlsen, S., and Westerlund, H., 2010. Immigrant Students’ Development of Musical Agency – Exploring Democracy in Music Education. British Journal of Music Education, 27 (3), 225–239.

- Kidd, B., Zahir, S., and Khan, S., 2008. Arts and Refugees: History, Impact and Future. London: Arts Council of England.

- Kisiara, O., 2015. Marginalized at the Centre: How Public Narratives of Suffering Perpetuate Perceptions of Refugees’ Helplessness and Dependency. Migration Letters, 12 (2), 162–171.

- Krensky, B., 2001. Going on Beyond Zebra: A Middle School and Community-based Arts Organization Collaborate for Change. Education and Urban Society, 33 (4), 427–444.

- Latour, B., 2005. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Latour, B., and Callon, M., 2014. Unscrewing the Big Leviathan: How Actors Macro-structure Reality and How Sociologists Help Them to do So. In: A.V. Cicourel, ed. Advances in Social Theory and Methodology. Abingdon: Routledge, 287–313.

- Lenette, C., 2019. Arts-based Methods in Refugee Research: Creating Sanctuary. Singapore: Springer International Publishing.

- Lenette, C., Cox, L., and Brough, M., 2015. Digital Storytelling as a Social Work Tool: Learning from Ethnographic Research with Women from Refugee Backgrounds. British Journal of Social Work, 45 (3), 988–1005.

- Lenette, C., and Sunderland, N., 2016. “Will There be Music for Us?” Mapping the Health and Well-being Potential of Participatory Music Practice with Asylum Seekers and Refugees across Contexts of Conflict and Refuge. Arts & Health, 8 (1), 32–49.

- Leudar, I., et al., 2008. Hostility Themes in Media, Community and Refugee Narratives. Discourse & Society, 19 (2), 187–221.

- Marsh, K., 2012. Music in the Lives of Refugee and Newly Arrived Immigrant Children in Sydney, Australia. In: P.S. Campbell and T. Wiggins, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Children’s Musical Cultures. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 492–509.

- Marsh, K., 2017. Creating Bridges: Music, Play and Well-being in the Lives of Refugee and Immigrant Children and Young People. Music Education Research, 19 (1), 60–73.

- Marsh, K., and Dieckmann, S., 2016. Music as Shared Space for Young Immigrant Children and their Mothers. In: P. Burnard, ed. The Routledge International Handbook of Intercultural Arts Research. Abingdon: Routledge, 358–368.

- Marsh, K., and Dieckmann, S., 2017. Contributions of Playground Singing Games to the Social Inclusion of Refugee and Newly Arrived Immigrant Children in Australia. Education 3–13, 45 (6), 710–719.

- Marsh, K., Ingram, C., and Dieckmann, S., 2020. Bridging Musical Worlds: Musical Collaboration between Student Musician-educators and South Sudanese Australian Youth. In: H. Westerlund, S. Karlsen, and H. Partti, eds. Visions for Intercultural Music Teacher Education. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 115–134.

- Matthews, N., and Sunderland, N., 2017. Digital Storytelling in Health and Social Policy: Listening to Marginalised Voices. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Nichols, B.E., 2020. Equity in Music Education: Access to Learning during the Pandemic and Beyond. Music Educators Journal, 107 (1), 68–70.

- Pesek, A., 2009. War on the Former Yugoslavian Territory: Integration of Refugee Children into the School System and Musical Activities as an Important Factor for Overcoming war Trauma. In: B. Clausen, U. Hemetek, and E. Sæther, eds. Music in Motion: Diversity and Dialogue in Europe. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, 359–370.

- Pym, A., 2010. Translation and Text Transfer: An Essay on the Principles of Intercultural Communication. Tarragona: Intercultural Studies Group.

- Renn, J., 2006. Übersetzungsverhältnisse: Perspektiven Einer Pragmatistischen Gesellschaftstheorie. Weilerswist: Velbrück Wissenschaft.

- Rivas, J., et al., 2021. Voices from Southwark: Reflections on a Collaborative Music Teaching Project in London in the Age of COVID-19. International Journal of Community Music, 14 (2–3), 169–189.

- Scott, J.C., 1985. Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Shaw, R.D., and Mayo, W., 2022. Music Education and Distance Learning during COVID-19: A Survey. Arts Education Policy Review, 123 (3), 143–152.

- Storsve, V., Westby, I.A., and Ruud, E., 2012. Hope and Recognition: A Music Project among Youth in a Palestinian Refugee Camp. In: B.Å.B. Danielson and G. Johansen, eds. Educating Music Teachers in the New Millennium. Oslo: Norges Musikkhøgskole, 69–88.

- Vogl, A., 2013. Telling Stories from Start to Finish: Exploring the Demand for Narrative in Refugee Testimony. Griffith Law Review, 22 (1), 63–86.

- Vougioukalou, S., et al., 2019. Wellbeing and Integration through Community Music: The Role of Improvisation in a Music Group of Refugees, Asylum Seekers and Local Community Members. Contemporary Music Review, 38 (5), 533–548.

- Western, T., 2020. Listening with Displacement: Sound, Citizenship, and Disruptive Representations of Migration. Migration and Society, 3 (1), 294–309.

- Young, Toby, 2023. Many Worlds in One Place: Composition as a Site of Encounter. In: Sarah Woodland and Wolfgang Vachon, eds. Sonic Engagement: The Ethics and Aesthetics of Community Engaged Audio Practice. New York: Routledge, 204–218.