ABSTRACT

The notion that scholars should reduce consumption of workrelated flight travel as a form of climate action has become common in academia. Proponents of this idea have coalesced into a sectoral movement seeking to have a more significant impact. This article critically reflects on the case of the Academic Flying Less Movement (AFLM) to conceptually explore how the environmental concerns of individual scholars might cohere and coalesce into something more powerful. We draw lessons from the AFLM’s existing efforts to change common academic practice through norm diffusion, while also interpreting lessons for the AFLM by developing a spiral model of strategic multi-scalar climate action, wherein the limitations of various modes of action compel scalar shifts towards different forms of action. Our analysis contributes to ongoing efforts in the field to develop more nuanced understandings of the value and limitations of small-scale, demandside actions within the broader constellation of climate action.

Introduction

In recent years, as concerns about climate change have become popularized, the idea of reducing consumption of work-related flight travel has become increasingly popular amongst scholars as a way of participating in climate action. Until recently, efforts to reduce academic-related air travel have largely taken place outside of any organized structure within academe. Rather, a handful of individually concerned scholars sought to cut back on their own work-related travel for the purpose of reducing their personal carbon footprints (Langin Citation2019). In the years leading up to the COVID-19 pandemic,Footnote1 however, those previously unaffiliated individuals started to organize and advocate for the institutionalization of the flying less norm throughout academia (particularly within the non-geographic Global North), coalescing into what we argue is a small but tangible collective movement – the Academic Flying Less Movement (hereafter AFLM). This article is born from critical reflection of the movement by two scholars involved in it. We seek to consider two interrelated questions: First, is there any point to taking part in these types of small-scale, mostly voluntary, demand-side actions? Second, is there a way for the AFLM to scale up to have a more significant impact across and beyond academia in terms of contributing meaningfully to climate change mitigation within the global aviation sector?

Many in the AFLM are acutely aware of the material limitations of small-scale, demand-side actions – particularly personal climate actions centering greener consumption or, as with the AFLM, withholding consumption of environmentally damaging goods. In part, this stems from reflections on a range of valid criticisms of the green consumption approaches that guided early proponents of the flying less norm. For instance, recent high-profile criticisms of the discourse of personal climate responsibility in the media have called for regulatory action at the level of the state, and for activists to centre their attention on corporate power rather than obsessing about lifestyle changes (Lukacs Citation2017, Mann and Brockopp Citation2019). The literature in the field of environmental politics has also highlighted the inherent dangers involved in the individuation of environmental politics (Scerri Citation2009) and the associated rise of ‘magical thinking’ in environmental thought: the idea that somehow the collective embrace of small-scale green consumption practices will aggregate and coalesce into some sort of environmentally transformative institutional change (Maniates Citation2019). Such criticisms have caused the AFLM to evolve strategically.

At the same time, proponents of the AFLM have found some justification for continuing to advocate for individually-oriented and/or small-scale, demand-side climate actions, or at least the value of targeting consumer behaviours of high-impact individuals in some way. For instance, recent work in this area has identified the outsized contribution that some groups of individuals make to global warming, namely more affluent high socio-economic status individuals located in the non-geographic Global North, which includes many academics. Thus, some have called for regulatory and other policy changes that seek to shape affluent lifestyles or better leverage their collective capacity to contribute to climate change mitigation (Akenji et al. Citation2019, Newell et al. Citation2021, Nielsen et al. Citation2021). For those in the AFLM, this has largely meant trying to diffuse the flying less norm such that it becomes codified and institutionalized within both the regular social practice of academe and the governance of scholarly activities. Yet, increasingly, there is recognition that to have a more significant impact in supporting climate change mitigation in the global aviation sector, the AFLM must go much further in some way.

We contend that there is indeed a point to taking part in individual demand-side climate actions such as flying less, but – importantly – to have a meaningful impact within and beyond academia, more diverse forms of scalar action are required. Moreover, there are lessons to be learned from the AFLM’s existing efforts to institutionalize the flying less norm throughout academia, while at the same time there are lessons to be learned for the AFLM as it seeks to foment material change in the aviation sector more broadly – particularly by reflecting upon criticisms about individual, small-scale, and/or demand-side climate actions. Using a novel spiral model of strategic multi-scalar climate action, we suggest that to support meaningful climate change mitigation within the aviation sector, proponents of the AFLM should ideally operate at multiple scales and forms at once, by:

practicing flying less at an individual level where possible;

working collectively with other small-scale groups of like-minded activists to create an active movement vanguard;

seeking to diffuse and institutionalize flying less as a norm throughout the academic sector’s social practice and governance structures;

forging partnerships with other flying less and aviation climate activists to help further diffuse the norm outside of academe;

turning to political action seeking regulatory, technological, and policy change within the aviation sector and its supply chains; and

continuing to advocate for and conduct research into better climate governance structures for the aviation sector.

This diversity of scalar ambitions allows for adaptive and sustained activism when efforts are blocked at any given scale. Our analysis contributes to ongoing efforts in the field of environmental politics to develop more nuanced understandings of the value and limitations of small-scale, demand-side climate actions within the broader constellation of climate actions, whilst also developing a theory of praxis for those in the AFLM itself.

Conceptual framework

This is a conceptual paper using a ‘model approach’ (Meredith Citation1993, Jaakkola Citation2020). Conceptual modelling ‘involves a form of theorizing that seeks to create a nomological network around the focal concept,’ thereby detailing causal linkages and ‘unexplored connections between constructs’ (Jaakkola Citation2020). Conceptual modelling typically advances arguments around a central figure depicting relations and arcs between key elements in a given phenomenon, rather than seeking to identify singular drivers (Meredith Citation1993, p. 8). These relations are idealized and narrativized from empirical analyzes of the networks and concepts in question. Specifically, in our case we use two models to show, first, how the AFLM has begun to pursue the institutionalization of its core proposed norm within academe and imagine scalar relations therein; and second, how some actors in the movement have effectively complicated that theory by shifting their scalar targets to try to support more meaningful material change in the global aviation sector.

We first provide a short history of the AFLM, largely based on the grey and scholarly literatures associated with flying less in academia. These literatures contain a diverse list of resources, including online petitions and campaigns, informal blog posts, magazine and media articles, departmental or institutional policy documents, and academic publications (resulting in a total of 140 pertinent sources). After documenting the formation of the movement, we model an aspirational pathway for further diffusion and institutionalization of the flying less norm within academia using core concepts within the norm diffusion literature. Subsequently, using our spiral scaling framework, we model how the AFLM can and must ultimately seek to expand beyond academia and beyond individual scale, voluntary, consumption-based actions, and instead seek various forms of collective, institutionalized, and political climate actions. We conclude the paper by discussing some of the implications of our conceptual models.

While ours is the first scholarly attempt that we are aware of to approach the AFLM as a social movement and provide an analysis of the transitional moments involved in institutionalizing the flying less norm within academia, our intended contributions go beyond the example of the AFLM itself. That is, we aim to identify the multiple scales that constitute climate action in this particular challenge area (the aviation sector’s climate impact), while demonstrating the potential value of individual actions (even consumption-based ones) – not as the first step of a presumed aggregation of similar green behaviours, but rather as a potential entry point for different forms and scalar orientations of climate action, especially those that recognize (and therefore adapt to) constraints at different levels.

Birth of a movement

The AFLM is shaped by the urgency of global climate mitigation today, combined with the realities of air travel as a contributing cause of climate change. Flying is specifically targeted because it is the most carbon-intensive activity undertaken by professional researchers and it is largely unregulated. Flight emissions usually account for about half to two thirds of the work-related carbon footprints of full-time academics (Nicholas and Wynes Citation2019), while aviation accounts for about one third of a typical university’s total GHG emissions profile (Hiltner Citation2018, Ciers et al. Citation2019). Despite aviation’s central role in work-related emissions within academia, universities largely do not incorporate flying into their existing climate policies or accounting efforts (Glover et al. Citation2017). This reluctance may stem from factors specific to the university, such as a lack of stakeholder pressure (from granting agencies, alumni, and students); concerns about overstepping the governance divisions between research and management (i.e. personal academic freedom); and because of the significant reputational and funding incentives that indirectly accrue from a well-travelled workforce (e.g. promoting the university brand, the intellectual reach of its researchers, and the increasing financial benefits of study abroad programming, etc.; see Storme et al. Citation2013). Lacking institutional governance, researchers have largely had to organize horizontally for change at the level of individual behaviours, peer norms, and departmental or associational expectations (Friesen Citation2019, Langin Citation2019).

The AFLM originated within a community of scholars who, both personally and professionally, were attuned to the climate impacts of flying. A disproportionate number of the AFLM’s early proponents were themselves climate and environmental scientists (Reay Citation2004, Ponette-González and Byrnes Citation2011, Anderson Citation2012, Nevins Citation2014, Kalmus Citation2016). Their personal behavioural choices, often rendered visible through somewhat spectacular feats of train travel or the principled withdrawal of their attendance at distant events, inspired a growing number of sympathetic climate-concerned colleagues and sparked conversations within the climate community about the need to align personal practices with the field’s policy suggestions (Langin Citation2019).

As the stakes of climate action have gained greater social prominence, the broader flying less movement has reached a wider audience and turned towards changing norms across the profession. In recent years, there have been a flurry of academic blog posts (Nicholas Citation2017, Dolšak and Prakash Citation2018, Hickel Citation2018, Büchs Citation2019, Heilman Citation2019); media profiles (Friesen Citation2019, Saner Citation2019); and journal articles confronting academic flying cultures (Nevins Citation2014, Ciers et al. Citation2019, Gössling et al. Citation2019, Higham et al. Citation2019, Wynes et al. Citation2019, Kreil Citation2021, Berné et al. Citation2022). This greater focus on individual decisions spurred further advocacy efforts for more collective forms of action, though most often still outside the organizational purview of the university campus. Peter Kalmus, for example, started the No Fly Climate Sci website for Earth scientists and other academics to individually pledge to reduce flight-related emissions.Footnote2 In the same vein, scholars Parke Wilde and Joseph Nevins started Flying Less as a petition calling on universities and professional associations to greatly reduce flying.Footnote3 More recently, advocates have begun targeting the associations that convene large international conferences and thus drive considerable academic air travel (Aron et al. Citation2020).

Institutionally oriented momentum has been further developed through applied research and practice in the sector, including carbon conduct initiatives, flying less resource documents, and most recently, departmental policies (see Katz-Rosene et al. Citation2019). Several low-carbon conferences have been piloted around the world, testing out new formats that do not require as much conference travel. Many of these efforts preceded the COVID-19 pandemic, during which virtual conferencing became the norm in many academic associations (at least on an interim basis). Some research centres and academic units have adopted internal policy documents in support of the flying less norm, through the initiative of advocate researchers. For instance, the UK-based Tyndall Centre, a collaborative project featuring over 200 climate change focused researchers from across the natural and social sciences, produced a Travel Strategy Document (Citation2014) to support a low-carbon research culture, including a decision tree to guide travel planning. In June 2019, the Department of Geography at Concordia University in Canada became one of the first departments to approve a Flying Less Policy (Department of Geography, Planning & Environment Citation2019), which loosely prioritized conference travel funding for graduate students to attend activities that do not require flying. Similar efforts have been reproduced elsewhere (for instance, Herrmann Citation2020). While the onset of the global COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 put many of these efforts on hold due to the de facto reduction of flight travel, a resurgence in air travel today is bringing back discussions about the flying less norm and how to expand its reach within academe.

Further institutionalizing the flying less norm

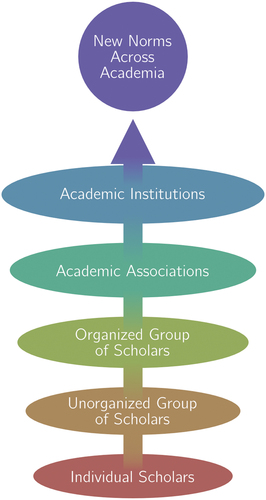

One way to interpret the trajectory of the AFLM within the scholarly community is through the concept of norm diffusion. Early work on norm diffusion within the global governance literature by Finnemore and Sikkink (Citation1998) explained how new proposed norms can scale-up or ‘cascade’ through a subset of the population (the ‘norm entrepreneurs’) towards eventual ‘internalization’ amongst a majority of actors (pp. 895–909). In the case of the AFLM, this could entail at least two main outcomes. At a socio-cultural level, the norm could become internalized within common academic practices. At an institutional level, the norm could become codified into the rules and governance structures of academic institutions. Specifically, if scholars in the Global North come to commonly believe that flying long-distances to conferences ought to be minimized in some way, or that scholarly meetings generally ought to have virtual participation optionality by default, then this would be a sign of the internalization of the norm at a socio-cultural level. Meanwhile, if academic associations that hold conferences begin to integrate policies that minimize flight requirements, or if funding agencies begin to codify requirements for scholars to demonstrate more than financial need in order to receive funding for flight travel, or if university tenure and promotion policies identify in writing that virtual conferences are just as valued as in-person events in terms of scholarly experiences, then these would all serve as examples of the institutionalization of the norm. As shows, this model of change looks like unidirectional scalar growth. As proponents see it, change starts with a few norm entrepreneurs primarily making personal changes in aviation consumption, but eventually this moves out to broader governance and cultural changes across the profession. Individual actions are a means towards institutionalization, not by virtue of the aggregation of individual acts, but through transformations across scales and forms of climate-inspired actions.

Figure 1. An aspirational vision of advancing the norm of flying less in academia, moving unidirectionally from individual to collective scales of action.

Alt Text: A diagram with several ovals stacked above oneanother, getting gradually larger in size. They change color from red to blue, with an upwards facing arrow cutting through and blending the transition colors. The ovals, from bottom to top, are labled:

Individual Scholars, Unorganized Group of Scholars, Organized Group of Scholars, Academic Associations, Academic Institutions. The arrow ends by pointing to a blue circle that reads New Norms Across Academia.

This model of change is both straightforward and, as critics point out, a little naïve. There are limits to relying on environmental norm diffusion as a means of meaningfully changing governance structures. For one, research on norms, and especially environmental norms, shows that the process of diffusion is usually more stuttered, incremental, and multi-dimensional than Finnemore and Sikkink’s (Citation1998) teleology suggests (Frantz and Pigozzi Citation2018). Further research on environmental norm diffusion has cast doubt on whether it can achieve substantive material change. As Dauvergne (Citation2018) has shown, new proposed environmental norms often struggle to garner enough support to move through to the internalization phase. This is especially so when the economic stakes are high, when there is political fragmentation regarding the ecological issue at play, and when the corporate sector strongly resists the new proposed environmental norm. Moreover, in Dauvergne’s assessment of the anti-plastic microbead norm, it was found that even though different forms of environmental action promoting the norm did indeed manifest in legislative change in the form of bans and restrictions, the net total of marine plastic pollution globally continued to grow. He thus concludes that there are very real weaknesses in ‘bottom up, ad hoc norm diffusion’ (Dauvergne Citation2018, p. 579). What is needed is for those norms to result in material change above and beyond the trends of a given product category. Thus, while the norm diffusion model adopted by the AFLM may offer some lessons for how to continue to seek change within academic practice, we also have lessons to learn for the AFLM from an acceptance of the limitations of centering a type of climate action that is founded upon a norm that has – for the most part – been interpreted through the gaze of individual, consumption-based voluntary action. And indeed, some AFLM proponents are beginning to explore these directions. We now turn to a spiral model of climate action to highlight how proponents of new environmental norms might think about scale differently moving forward.

Spiral scaling

As the AFLM seeks to change norms across academia it is not externally unopposed in its pursuits, particularly since business air travel has become so entrenched in recent decades (Gustafson Citation2014). Similarly, internal pressure from within the movement can occur as external critiques are debated, movement goals and composition are re-evaluated, and strategies are shifted in response. Here we suggest that contestation can lead to pressure to shift the scale and form of action both up and down, as proponents of this new environmental norm strategically reflect on how to overcome and address criticisms and limitations relating to a particular type of climate action. In other words, contestation can be generative and promote scaling in multiple directions. This provides a useful way to link the norm diffusion literature’s modeling of how new ideas emerge at one scale and work – through the action of proponents, and in the face of contestation from existing norms – across others, with the idea of ‘spiral scaling’ (Newell et al. Citation2021). As Newell et al. define it, ‘spiral scaling characterises the ongoing process of transformation from “shallow” to “deep” scaling as a dynamic sequence of feedback learning loops between individuals, society, institutions and infrastructures, towards strong global sustainability’ (Newell et al. Citation2021, p. 7 emphasis added).

As we now model, these dual internal and external contestations facing the flying less norm, and specifically strategic efforts within the AFLM to improve its efficacy, can create trans-scalar pressures. That is, in seeking to address both the internal and external criticisms and limitations that obtain to a given form and targeted scale of action, proponents of flying less are often compelled to pursue climate action in different forms and targeting different scales – potentially moving up or down in the size of the socio-political formations it seeks to engage. Making a meaningful contribution to climate change mitigation (in this specific case within the global aviation sector) is thus not merely a linear process of upscaling the flying less norm from the scale of norm entrepreneurship through to academia and beyond to norm internalization within governance structures and common behaviours, but rather a multi-dimensional process occurring in and at dissimilar spaces, speeds, and directions, and incorporating different forms and targets of action. To help model this evolving process, we present these trans-scalar pressures and responses through a series of six idealized moments of engagement within the spiral of climate action relevant to reducing aviation emissions, based on key deliberations within the AFLM’s recent history. We posit that ideally proponents of the AFLM and those concerned about mitigating the climatic impact of the aviation sector ought to seek to operate at multiple forms and scales simultaneously.

Addressing material insignificance

Because the AFLM began with individual pledges, a commonly understood limitation concerns the insignificant material climatic impact of an individual’s choice not to fly. At the scale of the climate, a single academic’s carbon footprint marks an infinitesimally small portion of the world’s (or even the sector’s) annual GHG emissions. Why, then, should one bother? Trans-scalar arguments followed in the AFLM’s responses to this question. The most obvious response is for practitioners of flying less to join with others. As a profession overrepresented at the departures gate (Gärdebo et al. Citation2017), scholars can thus credibly link personal behaviours to group-level collective action opportunities, with (slightly) more tangible material results in terms of emissions abatement (for concrete examples, see Klöwer et al. Citation2020). In the AFLM, small collectives of scholars have formed a movement vanguard that has launched letter-writing campaigns, created flying less pledges to enlist others, and pursued alternative forms of collective transportation to conferences (like carpooling) or conference organization (like hybrid or e-conferences). While the spectre of having to demonstrate a significant material benefit to the climate system serves as one of the key self-criticisms of the movement’s practitioners, one strategic response is to seek collaborations with like-minded individuals at larger (collective) scales.

Reframing the tone of action

Small collectives of like-minded scholars are quickly confronted with another moment of critique; this time pertaining to their potentially moralizing tone. For the AFLM, this has emerged through concerns that the framing of flying less as a moral action risks alienating others, in turn limiting the material impact of the decision to fly less (Ferguson Citation2019). Take, for instance, flygskam or ‘flight shame’: a word recently developed to represent the personalized feeling of guilt when flying. Shame, guilt, and other negative emotions often serve as triggers for regulating action or behavior on the part of an individual (Lickel et al. Citation2014). However, there is something of a paradox in the way individuals sometimes respond when called-out for supposedly non-conforming behaviour. If individuals feel attacked – and in particular when behaviours that they associate with key aspects of their identity are criticized – they may turn off or even fight back (Murtagh et al. Citation2012). Moreover, people who do take up the cause of more sustainable behavior as a result of negative emotions could rebound to their original behaviour if they feel as though they have taken on a greater share of burden than others (Frederiks et al. Citation2015). At this moment of norm contestation, academics may come to the defense of flying as a necessary part of the trade. While it is yet unclear whether such reactions against a vanguard of the AFLM may materialize in any significant sense, critiques of tone are generally seen as a potential limitation worth addressing. In doing so, the AFLM is compelled to shift scales and forms of action yet again, in this case to one that allows a more inclusive, collaborative effort across the scholarly community. By seeking equitable and voluntary flight reduction policies within academic departments, university faculties, and scholarly associations, the tone of the movement is reframed so that scholars do not feel as if they are being shamed to act on their own by their colleagues, but instead included as a stakeholder in collective deliberations and expectations.

Building diverse coalitions

In pursuing more expansive efforts to define and act on the problem, movements like the AFLM inevitably run into another obstacle: Inequalities between members of the collective (and those seeking membership therein) complicate the extent to which the group can or should move as a whole. In the case of the AFLM, when movement actors – typically tenured or tenure-track faculty members in the Global North – address academia as a singular group, they risk making inequitable assumptions about who can afford to withdraw from the aviation-dependent norms of contemporary academia. For most early career and precariously employed scholars, even one speaking invitation may be an occasion not to be missed, as it affords vital networking and career advancement opportunities. Furthermore, several disciplines effectively require attendance at large annual conferences as early steps in the job interview process, and thus de facto require air travel. Moreover, attendance via more low-carbon travel arrangements may neither be possible nor feasible (for financial or time reasons) to researchers with tight budgets, heavy teaching loads, and care work responsibilities (Calisi and Working Group of Mothers in Science Citation2018).

Strategic responses from the AFLM seek to shift the scale of action, though now moving across multiple directions. On the one hand, AFLM activists advocate for the transformation of the entire academic profession, in part by proposing new norms and expectations around every academic’s relationship with travel (i.e. to bring everyone along for the ride). This opens up considerations of useful equity co-benefits to flying less (Skiles et al., Citation2022). As the opportunities for travel disproportionately accrue to those in elite positions in academia (Wynes et al. Citation2019), AFLM proponents have argued that flying less should concern itself with much more than mitigating the climate impacts of air travel itself; it must also – at least to some degree – seek to address long-standing injustices across the global academy (Pasek Citation2020). By scaling up, the AFLM thus augments the stakes and broadens coalitions that make up the movement.

Yet, at the same time, AFLM proponents also advance parallel arguments that instead seek to resolve these critiques by narrowing their address and scaling down their target actors. AFLM actors drawing on a mobility justice framework (Sheller Citation2022) have argued that the benefits of flying might not be uniformly abandoned in the short term, but rather restricted to those who have not already benefitted from extensive air travel. Funding for flights at the departmental or faculty scale might thus be awarded on the basis of need and equity, reducing overall travel miles while preventing inequitable outcomes during the process of collective norms adoption. These proposals move away from addressing the norms of the entire profession, instead focusing on the needs of smaller constituencies within it.

Seeing the forest for the trees

While new norms about a more equitable academia are laudable, at this scale of proposed action the AFLM becomes limited by its inward focus on academe. The aviation footprint of researchers, after all, is a mere fraction of that of aviation at large. Moreover, the argument has been made that some academic travel is of net benefit to the climate, particularly for sustainability researchers engaged in wide-ranging environmental governance and advocacy work (Bendell Citation2016). In strategically reflecting upon this critique, the AFLM yet again faces pressure to shift scales, in this case beyond academia.

Here, the AFLM can seek broader partnerships with the climate advocacy work of allies in a range of aviation-dependent professions, becoming part of a broader Flying Less Movement. The Stay Grounded network, an amalgam of some 180 member organizations from around the world, is one such example. The network was founded in 2016 by climate activists seeking to call out the ICAO’s lax aviation and climate plan through a series of protests at airports (Stay Grounded Network Citation2021). More recently, the network has forged partnerships with academics, hosting a conference on ‘degrowing aviation’ and publishing reports and discussion papers on the science and strategy of flight reduction across sectors (Stay Grounded Citation2019, Stay Grounded, & PCS Citation2021). In this way, the (A)FLM is less a case of missing the forest (the aviation sector) for the trees (academic flying), and more a recognition that trees constitute, and relate with, the wider forest.

At the same time, other AFLM proponents may seek to scale down action in recognition of the opportunities specific to their part of this wider forest. Although academic aeromobility patterns follow broader trends in globalized, flexible work rhythms, it can still be argued that researchers enjoy, at least in principle, unique levels of self-determination, especially after achieving tenure. The rise of e-conferencing during COVID-19, moreover, has already introduced greener alternatives to the academic sector’s cultural expectations about conferencing. The AFLM, accordingly, can argue that their sector is positioned to move faster than others, and therefore ought to.

Avoiding neoliberal diversions

Even at cross-sectoral scales, a coalition of groups seeking to abstain from aviation is still subject to a political economic critique that is broadly skeptical of consumption-based solutions. Such tactics, the critique posits, must be understood as an outcome of neoliberalization, wherein governance decisions have been offloaded to consumers and the ‘invisible hand’ of the market (Lukacs Citation2017). In this sense, the (A)FLM is portrayed as merely playing into the corporate sector’s strategy to get people to cast blame for environmental harm upon themselves or one another (Mayes et al. Citation2017), rather than the large profiteering corporations doing everything within their power to delay meaningful action in cases where it cuts into their profits (Huber Citation2021). If consumption-based climate action proposals are problematically diverting attention away from the real culprits in the sector’s climate impacts, then, to overcome this critique, the movement ought also to focus its attention on targeting those corporations and the entire production supply chain of aviation in the first place.

Opportunities to address these challenges of political economy obtain across many scales and forms of action. The cross-sectoral FLM might agitate for state-level regulations in the aviation sector requiring corporate actors – from airlines to aircraft manufacturers to aviation fuel producers and airports – to reduce emissions throughout their operations and supply chains. The possibilities for governmental action are vast, ranging from punitive and hard cap approaches, to more business-friendly options that earmark public investments for the corporate sector with some climate policy strings attached (as exemplified in the French government’s recent bailout package for Airbus and Air France, which required the firms to use the investments to design low carbon aircraft; see Topham Citation2020). At the same time, smaller scale tactics may be necessary to move towards these larger goals. Two of the most poignant examples of this include Frequent Flyer Levy campaigns and appeals to stop airport expansions, campaigns that have been especially effective in garnering political attention in the United Kingdom and France thanks to efforts by advocates of the FLM such as Stay Grounded and the Campaign for Better Transport (Coffey Citation2021, Usborne Citation2021). These types of collective action could be pursued at various scales, through political letter-writing campaigns, consumer boycott campaigns, demonstrations and rallies, individuals offering expert testimonials to legislative hearings, and the mobilization of research findings.

Avoiding a tragedy of collective action

State-based efforts to regulate the aviation sector’s climatic footprint are precisely the type of collective action policies that critics of personal climate action typically support. Yet even at this scale of action, there are limitations that result in pressures to shift scales. The problem with stopping at the level of state regulations, some say, is that the atmosphere is a commons, and without some type of collective action at the international scale it is subject to the tragedy of unit actors pursuing their economic interests (e.g. O’gorman Citation2010, Keohane and Victor Citation2016). By way of example, the implementation of relatively strong climate regulations on the aviation sector in the European Union has done little to incentivize similar actions in the United States. What is ultimately needed, then, is a global scale collective agreement wherein all nations commit the entire aviation sector to a regulatory framework aiming to reduce the sector’s climatic footprint – ideally with strong enforcement mechanisms to hold all parties to account.

This impetus has thus far given rise to the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (or CORSIA). CORSIA seeks to introduce a global market-based mechanism to raise capital for the sector to offset emissions from international aviation, and additionally seeks to cap emissions at 2020 levels (Carpanelli Citation2018). In addition to offsets, the international agreement seeks to use technological innovations in the form of more efficient aircraft, better air traffic control, and new low-carbon sustainable fuels. These types of global agreements, which span the entire aviation sector and implicate the entire international community, mark the highest scale of collective climate action possible. Insofar as the FLM can advocate and agitate in favour of such global-scale governance, it ought to, as it nicely complements action at other scales of the collective.

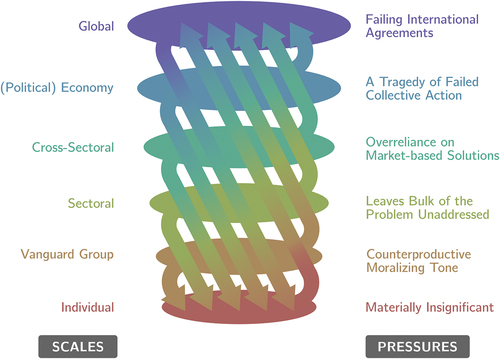

Nevertheless, even global actions come with limitations. Namely, such efforts have a poor track record on climate change mitigation (Stoddard et al. Citation2021). State and international efforts serve as a stark example of how collective action has thus far failed to produce meaningful results. CORSIA specifically has been widely criticized for being deeply ineffective (see Pidcock and Yeo Citation2016, Lyle Citation2018), not solely because of its reliance on offsets, but because it seeks to cap emissions growth at a very high baseline (Pidcock and Yeo Citation2016). This has prompted both calls for a better agreement with stronger enforcement mechanisms (Niranjan and Schacht Citation2021) and, importantly, climate action at smaller scales to fill in gaps left by a failed global collective effort. To account for failures in global regulatory efforts, proponents of the academic flying less norm can concentrate their work in more specific targeted areas over which they have greater control – for instance, by tackling aviation emissions in their own work lives, influencing colleagues, organizing to pass departmental policies, seeking changes to common practice in their profession, and engaging in political activism, and – yes – through individualized green consumption practices. In this way, withdrawing from the aviation marketplace is an acknowledgement of current scalar prospects for reform. It is in this capacity that the AFLM spiral scales action ‘from the individual to the systemic level and back again’ (Newell et al. Citation2021, p. 9 emphasis added) with the intention of achieving transformative change (see ).

Figure 2. A multidirectional model for spiral scaling action on aviation and climate change, demonstrating contestation and pressure to shift scales of action.

Alt Text: A diagram several ovals stacked on top of one another, getting gradually larger in size and changing colour from red to blue. Instead of a single upward arrow, there are now several arrows cutting across the ovals, pointing up and down. On one side of the diagram are lables for Scale; starting from the bottom to the top, they read: Individual, Vanguard Group, Sectoral, Cross-Sectoral, (Political) Economy, and Global. On the other side there are lables for Pressures; starting from the bottom to the top, they read: Materially Insignificant, Counterproductive Moralizing Tone, Leaves Bulk of the Problem Unaddressed, Overreliance on Marker-based Solutions, A Tragedy of Failed Collective Action, and Failing International Agreements.

Concluding discussion

In this final section we draw upon the modelling of norm diffusion and spiral scaling within and without academe to discuss lessons from and for the AFLM, as well as the need for further research in environmental politics in the area of interscalar forms of climate action.

First, the AFLM has often imagined its objective of norm diffusion as a unidirectional upscaling from norm entrepreneur to the profession at large. However, a fuller consideration of the challenges that obtain at different scales, and indeed the practices of some AFLM advocates, demonstrate that up may not be the only or best direction to go, or even an available direction in the first place. Moreover, the AFLM will need to make further connections beyond the academy if it is to be truly effective in achieving material change. That is, it ought to seek partnerships with other sectors to influence aviation supply chains, agitate for change within domestic transport regulations and even more ambitious international agreements governing aviation’s climatic impact as part of a broader spectrum of climate related civic actions.

Second, drawing from our spiral model, we propose that those seeking to advance new environmental norms should pursue a diversity of scales, including: i) the individual, ii) the vanguard group, iii) sectoral social practice and governance structures, iii) trans-sectoral collaborations, iv) industrial standards and supply chains, and v) global regulatory agreements. Embracing a diversity of tactics and targets is commonly regarded wisdom in many social movements (Johnson et al. Citation2010, Chewinski and Corrigall-Brown Citation2022); to this we can urge the embrace of a diversity of scales.

Third, we note that scale is, by now, a lively and increasingly complicated topic of inquiry in climate politics. Scholarly work in environmental behavioural change has identified the need for multiple, complex, and simultaneous layers of climate action (Vandenbergh et al. Citation2008, Ostrom Citation2016). The literature on low-carbon lifestyles has thus sought to problematize the purported dichotomy between individual and collective scales of action, or between consumption-focused (demand-side) and production-centred (supply-side) regulations and solutions, and to better understand how a combination of different types, focal points, and scales of action could result in concrete change (Creutzig et al. Citation2016, Akenji et al. Citation2019, Newell et al. Citation2021, Nielsen et al. Citation2021). As Akenji et al. (Citation2019) explain, for decades climate policy has sought system change, promoting new technological advances to green the production of everyday commodities, and enacting carbon pricing mechanisms to adequately capture the cost of climate pollution such that people can go about their daily lives without significant disruptions to lifestyle patterns. Yet while these collective scale, supply-side actions are important, it is still the case that ‘changes in predominant lifestyles, especially in high-consuming societies, will determine whether we meet commitments in the Paris Agreement and avoid dire consequences of climate change’ (p. 3). Recent work by the 2021 Cambridge Sustainability Commission report on Scaling Behaviour Change has further identified how bringing about lifestyle changes amongst the world’s wealthiest individuals is particularly important for limiting global warming to 1.5°C. Moreover, the report authors identify the ‘need to rethink scale’ in discussions around climate action, such that change becomes truly transformative, moving up from the individual to the level of systems change, and then scaling back down (Newell et al. Citation2021, p. 9).

These insights have particular importance for the AFLM debate. People with high socio-economic status, which includes individuals with access to ample financial and social resources, and in all likelihood those reading this very article, have a disproportionate climate influence, not only as consumers, but as investors, role models, educators, organizational participants, and as citizens (Nielsen et al. Citation2021). This matters strategically; the reduction of such lifestyle emissions will be most significant if approached from both small-scale demand-side voluntary actions and larger-scale, collective, regulatory actions. There is, then, a point to scholars individually practicing flying less and to seeking out the diffusion of a flying less norm throughout academia – not because it makes a significant material contribution to climate change mitigation (arguably it does not), but rather because of the potential relations that such actions can hold with other scales and forms of climate actions that can, in toto, be more materially significant.

It seems, therefore, that we are moving towards a view that does not programmatically insist a priori on the importance or unimportance of a given scale of action, but rather that approaches scale as a question of situated constraints and opportunities. As we demonstrate through our models of norm diffusion within academe and spiral scaling more broadly, the AFLM has emerged as a movement targeting behavioural and institutional change across the profession. However, the road map for norm diffusion is likely to be met with setbacks, obstacles, and may travel a very long road to substantive change. Those within the AFLM often engage in iterative (and in our case, ongoing) deliberations concerning different critiques that obtain at different scales, and can credibly respond with strategic moves in either direction. Fundamentally, this will mean that to have a more meaningful impact, the AFLM will need to go beyond academe and beyond norm diffusion, creating partnerships with other subsectors seeking more climate-friendly aviation and pursuing a range of tactics at different scales and of different forms. With global change in mind, but without a unidirectional map to get there, movement actors must react to – and seek to shape – their circumstances. We therefore welcome new and further inquiries into the politics of scale that attend to the way actors plan and reason across different sizes of social collectivity, and especially the generative frictions one finds in-between them.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all anonymous reviewers for their feedback. Additionally, they are indebted to Lisa Seiler and Susan O’Donnell for their critical insights and editorial help.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The COVID-19 pandemic brought the practice of academic air travel to a complete halt early in 2020, completely transforming the nature of scholarly exchange and research fieldwork, and opening the door to new practices in low-carbon scholarly exchange (Klöwer et al. 2020). Inevitably, as the world overcomes the pandemic (or learns to live with the virus) questions around the environmental politics of academic flying will come back to the fore.

2. At the time of writing there were 17 institutions and 675 individual signatories.

3. At the time of writing the petition had 1073 signatories.

References

- Akenji, L., et al., 2019. 1.5- degree lifestyles: targets and options for reducing lifestyle carbon footprints. Institute for Global Environmental Strategies, Aalto University, and D-mat ltd. https://www.iges.or.jp/en/pub/15-degrees-lifestyles-2019/en

- Anderson, K., 2012. The inconvenient truth of carbon offsets. Nature News, 484 (7392), 7. doi:10.1038/484007a.

- Aron, A.R., et al., 2020. How can neuroscientists respond to the climate emergency? [Preprint]. PsyArxiv. doi:10.31234/osf.io/dxpv4.

- Bendell, J., 2016, May 30. Carry on flying: why activists should take to the skies. OpenDemocracy. https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/transformation/carry-on-flying-why-activists-should-take-to-skies/

- Berné, O., et al., 2022. The carbon footprint of scienti?c visibility. Environmental Research Letters, 17 (12), 124008. doi:https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ac9b51.

- Büchs, M., 2019, July 9. University sector must tackle air travel emissions. The Conversation. http://theconversation.com/university-sector-must-tackle-air-travel-emissions-118929

- Calisi, R.M. and Working Group of Mothers in Science, 2018. Opinion: how to tackle the childcare–conference conundrum. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115 (12), 2845–2849. doi:10.1073/pnas.1803153115.

- Carpanelli, E., 2018. Between global climate governance and unilateral action: the establishment of the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA). In: Harmonising regulatory and antitrust regimes for International Air Transport. Routledge, 125–141. doi:10.4324/9781351134910-11.

- Chewinski, M. and Corrigall-Brown, C., 2022. Penalty or payoff? Diversity of tactics and resource mobilization among environmental organizations. The American Behavioral Scientist, 66 (9), 1181–1203. doi:10.1177/00027642211056573.

- Ciers, J., et al., 2019. Carbon footprint of academic air travel: a case study in Switzerland. Sustainability, 11 (1), 80. doi:10.3390/su11010080.

- Coffey, H., 2021, October 13. Frequent flyer levy backed by 89% of Brits to tackle climate crisis. The Independent. https://www.independent.co.uk/travel/news-and-advice/frequent-flyer-levy-flights-climate-b1937447.html

- Creutzig, F., et al., 2016. Beyond technology: demand-side solutions for climate change mitigation. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 41 (1), 173–198. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-110615-085428.

- Dauvergne, P., 2018. The power of environmental norms: marine plastic pollution and the politics of microbeads. Environmental Politics, 27 (4), 579–597. doi:10.1080/09644016.2018.1449090.

- Department of Geography, Planning & Environment, 2019, July 1. Flying Less Policy. Concordia University Arts and Science. https://www.concordia.ca/content/dam/artsci/geography-planning-environment/docs/Flying_Less_Policy_GPE_June1_2019.pdf

- Dolšak, N. and Prakash, A., 2018, March 31. The climate change hypocrisy of jet-setting academics. HuffPost. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/opinion-dolsak-prakash-carbon-tax_n_5abe746ae4b055e50acd5c80

- Ferguson, K., 2019, August 30. The overlooked danger of flight shaming. DW.COM. https://www.dw.com/en/the-overlooked-danger-of-flight-shaming/a-50192039

- Finnemore, M. and Sikkink, K., 1998. International norm dynamics and political change. International Organization, 52 (4), 887–917. doi:10.1162/002081898550789.

- Frantz, C.K. and Pigozzi, G., 2018. Modeling norm dynamics in multi-agent systems. Journal of Applied Logics, 5 (2), 1–73.

- Frederiks, E.R., Stenner, K., and Hobman, E.V., 2015. Household energy use: applying behavioural economics to understand consumer decision-making and behaviour. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 41, 1385–1394. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2014.09.026

- Friesen, J., 2019, July 15. Academics pledge to fly less due to environmental impact of air travel. The Globe and Mail. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-academics-pledge-to-fly-less-due-to-environmental-impact-of-air-travel/

- Gärdebo, J., Nilsson, D., and Soldal, K., 2017. The travelling scientist: reflections on aviated knowledge production in the anthropocene. Resilience: A Journal of the Environmental Humanities, 5 (1), 71–99. doi:10.5250/resilience.5.1.0071.

- Glover, A., Strengers, Y., and Lewis, T., 2017. The unsustainability of academic aeromobility in Australian universities. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy, 13 (1), 1–12. doi:10.1080/15487733.2017.1388620.

- Gössling, S., et al., 2019. Can we fly less? Evaluating the ‘necessity’ of air travel. Journal of Air Transport Management, 81, 101722. doi:10.1016/j.jairtraman.2019.101722

- Gustafson, P., 2014. Business travel from the traveller’s perspective: stress, stimulation and normalization. Mobilities, 9 (1), 63–83. doi:10.1080/17450101.2013.784539.

- Heilman, J., 2019, July 8. Grounded: academic Flying in the Time of Climate Emergency. Active History. http://activehistory.ca/2019/07/grounded-academic-flying-in-the-time-of-climate-emergency/

- Herrmann, L., 2020, May 8. Flying less gets a thumbs-up. Flying Less Gets a Thumbs-Up. https://ethz.ch/services/en/news-and-events/internal-news/archive/2020/08/flying-less-gets-a-thumbs-up.html

- Hickel, J., 2018, January 13. In an era of climate change, our ethics code is clear: we need to end the AAA annual meeting. Anthro{dendum}. https://anthrodendum.org/2018/01/13/climate-change-ethics-code-end-aaa-annual-meeting/

- Higham, J.E.S., Hopkins, D., and Orchiston, C., 2019. The work-sociology of academic aeromobility at remote institutions. Mobilities, 14 (5), 612–631. doi:10.1080/17450101.2019.1589727.

- Hiltner, K., 2018. A nearly carbon-neutral conference model. University of California Santa Barbara. https://hiltner.english.ucsb.edu/index.php/ncnc-guide/

- Huber, M.T., 2021. Carbon responsibility and class power. The Professional Geographer, 74 (1), 1–2. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00330124.2021.1915813.

- Jaakkola, E., 2020. Designing conceptual articles: four approaches. AMS Review, 10 (1), 18–26. doi:10.1007/s13162-020-00161-0.

- Johnson, E.W., Agnone, J., and McCarthy, J.D., 2010. Movement organizations, synergistic tactics and environmental public policy. Social Forces, 88 (5), 2267–2292. doi:10.1353/sof.2010.0038.

- Kalmus, P., 2016, February 11. How far can we get without flying?. Yes!. https://www.yesmagazine.org/issues/life-after-oil/how-far-can-we-get-without-flying-20160211

- Katz-Rosene, R., et al., 2019, Spring. Flying less in Academia: a resource guide .

- Keohane, R.O. and Victor, D.G., 2016. Cooperation and discord in global climate policy. Nature Climate Change, 6 (6), 570–575. Article 6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2937.

- Klöwer, M., et al., 2020. An analysis of ways to decarbonize conference travel after COVID-19. Nature, 583 (7816), 356–359. Article 7816. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-02057-2.

- Kreil, A.S., 2021. Does flying less harm academic work? Arguments and assumptions about reducing air travel in academia. Travel Behaviour and Society, 25, 52–61. doi:10.1016/j.tbs.2021.04.011

- Langin, K., 2019, May 13. Why some climate scientists are saying no to flying. Science, 364 (6441), 621. https://www.sciencemag.org/careers/2019/05/why-some-climate-scientists-are-saying-no-flying

- Lickel, B., et al., 2014. Shame and the motivation to change the self. Emotion, 14 (6), 1049–1061. doi:10.1037/a0038235.

- Lukacs, M., 2017, July 17. Neoliberalism has conned us into fighting climate change as individuals. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/true-north/2017/jul/17/neoliberalism-has-conned-us-into-fighting-climate-change-as-individuals

- Lyle, C., 2018. Beyond the ICAO’s CORSIA: towards a more climatically effective strategy for mitigation of civil-aviation emissions. Climate Law, 8 (1–2), 104–127. doi:10.1163/18786561-00801004.

- Maniates, M., 2019, Beyond magical thinking. In: A. Kalfagianni, D. Fuchs, and A. Hayden, eds. Routledge Handbook of Global Sustainability Governance. 1st ed. Routledge, 267–281. doi:10.4324/9781315170237-22.

- Mann, M.E. and Brockopp, J., 2019, June 3. Climate change requires government action, not just personal steps. USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/story/opinion/2019/06/03/climate-change-requires-collective-action-more-than-single-acts-column/1275965001/

- Mayes, R., Richards, C., and Woods, M., 2017. (Re)assembling neoliberal logics in the service of climate justice: fuzziness and perverse consequences in the fossil fuel divestment assemblage. In: V. Higgins and W. Larner, eds. Assembling neoliberalism: expertise, practices, subjects. Palgrave Macmillan US, 131–149. doi:10.1057/978-1-137-58204-1_7.

- Meredith, J., 1993. Theory building through conceptual methods. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 13 (5), 3–11. doi:10.1108/01443579310028120.

- Murtagh, N., Gatersleben, B., and Uzzell, D., 2012. Self-identity threat and resistance to change: evidence from regular travel behaviour. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 32 (4), 318–326. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2012.05.008.

- Nevins, J., 2014. Academic jet-setting in a time of climate destabilization: ecological privilege and professional geographic travel. The Professional Geographer, 66 (2), 298–310. doi:10.1080/00330124.2013.784954.

- Newell, P., Twena, M., and Daley, F., 2021. Scaling behaviour change for a 1.5 degree world: challenges and opportunities. Global Sustainability, 1–25. doi:10.1017/sus.2021.23.

- Nicholas, K.A., 2017, July 12. A hard look in the climate mirror—scientific American blog network. https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/observations/a-hard-look-in-the-climate-mirror/

- Nicholas, K.A. and Wynes, S., 2019, July 16. Flying less is critical to a safe climate future. Public Administration Review. https://www.publicadministrationreview.com/2019/07/16/gnd24/

- Nielsen, K.S., et al., 2021. The role of high-socioeconomic-status people in locking in or rapidly reducing energy-driven greenhouse gas emissions. Nature Energy, 6 (11), 1–6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-021-00900-y.

- Niranjan, A. and Schacht, K., 2021, January 22. CORSIA: world’s biggest plan to make flying green “too broken to fix.”. DW.COM. https://www.dw.com/en/corsia-climate-flying-emissions-offsets/a-56309438

- O’gorman, M., 2010. Global warming: a tragedy of the commons. SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1653947.

- Ostrom, E., 2016, February 21 . A multi-scale approach to coping with climate change and other collective action problems. The Solutions Journal. https://thesolutionsjournal.com/2016/02/22/a-multi-scale-approach-to-coping-with-climate-change-and-other-collective-action-problems/

- Pasek, A., 2020. Low-carbon research: building a greener and more inclusive academy. Engaging Science, Technology, and Society, 6, 34–38. doi:https://doi.org/10.17351/ests2020.363

- Pidcock, R. and Yeo, S., 2016, August 8. Analysis: Aviation could consume a quarter of 1.5C carbon budget by 2050. Carbon Brief. https://www.carbonbrief.org/aviation-consume-quarter-carbon-budget

- Ponette-González, A.G. and Byrnes, J.E., 2011. Sustainable science? Reducing the carbon impact of scientific mega-meetings. Ethnobiology Letters, 2, 65–71. doi:10.14237/ebl.2.2011.29

- Reay, D.S., 2004. New directions: flying in the face of the climate change convention. Atmospheric Environment, 38 (5), 793–794. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2003.10.026.

- Saner, E., 2019, May 22. Could you give up flying? Meet the no-plane pioneers. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/travel/2019/may/22/could-you-give-up-flying-meet-the-no-plane-pioneers

- Scerri, A., 2009. Paradoxes of increased individuation and public awareness of environmental issues. Environmental Politics, 18 (4), 467–485. doi:10.1080/09644010903007344.

- Sheller, M., 2022. Mobility Justice: The Politics of Movement in an Age of Extremes. Verso.

- Skiles, M., et al., 2022. Conference demographics and footprint changed by virtual platforms. Nature Sustainability, 5, 149–156. doi:10.1038/s41893-021-00823-2

- Stay Grounded, 2019. Degrowth of aviation: reducing air travel in a just Way. 52. https://stay-grounded.org/report-degrowth-of-aviation/

- Stay Grounded Network, 2021, October 14. Looking back at 5 years of stay grounded. Stay-Grounded.Org. https://stay-grounded.org/5-years/

- Stay Grounded, & PCS, 2021. A rapid and just transition of aviation—shifting towards climate-just mobility. https://stay-grounded.org/just-transition/

- Stoddard, I., et al., 2021. Three decades of climate mitigation: why haven’t we bent the global emissions curve? Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 46 (1), 653–689. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-012220-011104.

- Storme, T., et al., 2013. How to cope with mobility expectations in academia: individual travel strategies of tenured academics at Ghent University, flanders. Research in Transportation Business & Management, 9, 12–20. doi:10.1016/j.rtbm.2013.05.004

- Topham, G., 2020, June 9. France announces €15bn plan to shore up Airbus and Air France. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2020/jun/09/france-announces-15bn-plan-to-shore-up-airbus-and-air-france

- Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research, 2014, July 21. Tyndall travel strategy. Tyndall.Ac.Uk. https://tyndall.ac.uk/sites/default/files/tyndall_travel_strategy_updated.pdf

- Usborne, S., 2021, October 26. Hot topic: should we tax frequent flyers? National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.co.uk/travel/2021/10/hot-topic-should-we-tax-frequent-flyers

- Vandenbergh, M.P., Barkenbus, J., and Gilligan, J., 2008, August 23. Individual carbon emissions: the low-hanging fruit. UCLA Law Review. https://www.uclalawreview.org/individual-carbon-emissions-the-low-hanging-fruit/

- Wynes, S., et al., 2019. Academic air travel has a limited influence on professional success. Journal of Cleaner Production, 226, 959–967. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.04.109