Abstract

This paper looks at the spread and socialization of gender transformative approaches (GTA) within a network of research and development organizations that focus on gender and agriculture. We conducted in-depth interviews with 20 respondents from 19 development and research organizations who work in the agriculture sector and have some interest or engagement with GTA, and we analyzed the scaling drivers and patterns within and beyond this immediate network. The findings show a rapidly growing interest in GTA across the ecosystem, especially among organizations with a strong commitment to helping achieve gender equality. GTA are scaling out across the ecosystem in a nonlinear way, through both direct and indirect strategies. Factors such as the mandate and agency of an organization, as well as the persistence and passion of individual stakeholders appear to be important drivers in influencing how GTA are spreading. Despite the enthusiasm and high momentum for doing gender transformative work across the organizations, this study also surfaces serious reservations about how rapidly the terminology and/or tools related with GTA are being adopted, while there remain widely varying levels of understanding, gender expertise, and funding for the type of intensive effort that is required to achieve a true paradigm shift in the sector.

Introduction

Gender transformative approaches (GTA) have entered the global gender and development discourse in recognition of the failures of more common gender approaches to substantially transform gendered inequalities (Kantor, Citation2013). Conceptualized as a continuum of approaches, “doing gender” in development spans from harmful to transformative interventions. At the harmful end of the spectrum, gender-blind approaches respectively exploit, reinforce, or ignore gender norms, inequalities and differences, thus exacerbating existing gaps and inequalities. Gender-aware approaches include two key forms: accommodative (gender-sensitive and gender-responsive approaches, which involve gender analysis and working around gender issues and visible barriers, such as distinct needs and women’s time constraints) and transformative approaches (see IGWG, Citation2017; McDougall, Citation2021a). Gender transformative approaches complement yet also break from other gender-aware approaches in the continuum in terms of the aims and depth at which they work (Kabeer & Subramanian, Citation1996). Rather than trying to identify and accommodate gender differences and barriers to work around or minimize gender gaps or inequalities, GTA identify and seek to transform the root causes of gender inequalities (Wong et al., Citation2019; Kantor et al., Citation2015; Hillenbrand et al., Citation2015; Pederson et al., Citation2015). In doing so, GTA aim to influence systemic change at the level of structural and normative building blocks of society, rather than to focus only on individual or group-level empowerment (Mullinax et al., Citation2018; McDougall et al., Citation2021b). As summarized by the FAO (n.d.), gender transformative approaches:

…actively examine, challenge and transform the underlying causes of gender inequality rooted in inequitable social structures and institutions. As such the gender transformative approach aims at addressing imbalanced power dynamics and relations, rigid gender norms and roles, harmful practices, unequal formal and informal rules as well as gender-blind or discriminatory legislative and policy frameworks that create and perpetuate gender inequality. By doing so, it seeks to eradicate the systemic forms of gender-based discrimination….Footnote1

While there is fluidity and diversity in their framing, there is some convergence around the fundamental principles of GTA and how these manifest in practice. These include: (1) a deep understanding of and focus on addressing the root causes of gender inequality, both in the given context specifically and as systemic and structural change; (2) an orientation to strategic gender interests (power, rights), not only practical gender needs; (3) engaging women, men, and people of all gender identities as jointly responsible for and co-agents in processes of change and gender justice; (4) seeking change at multiple scales (including household, community, regional, national); and, (5) using iterative cycles of action and reflection to challenge oppressions (see for example, McDougall et al., Citation2023; MacArthur et al., Citation2022; Mullinax et al., Citation2018; Njuki et al., Citation2016; Kantor et al., Citation2015). In practice, implementation of GTA to date has often included participatory and dialogic processes, engaging people in cycles of critical reflection on how gender biases and norms penetrate all aspects of society, and how these shape experiences, opportunities, and outcomes for individuals, households, or communities. Use of an intersectional lens, which connects gender and other and compounding forms of social discrimination, has been flagged as important to address in GTA—although this principle has not yet been widely operationalized (McDougall et al., Citation2023; MacArthur et al., Citation2022). Notably, these gender-transformative principles and practices have been proposed as essential not only for addressing inequalities “out there” (in communities, markets, and so forth), but also within the organizations carrying out development policy, programming and research themselves (McDougall et al., Citation2023; Kantor et al., Citation2015; Hillenbrand et al., Citation2015).

The emergence of GTA in development programs appears to have begun initially in the health, education, and sexual and reproductive health sectors (MacArthur et al., Citation2022; Ruane-McAteer et al., Citation2019; Casey et al., Citation2018; Barker et al., Citation2010; Rottach et al., Citation2009). Evidence from this sector shows that gender-transformative programming is highly effective in improving gender-equal attitudes, reducing gender-based violence, and strengthening women’s empowerment (Giusto & Puffer, 2018; Barker et al., Citation2010). Over the last ten years, interest in GTA has spread beyond the health sector and been taken up by a growing number of actors in the agriculture research for development (AR4D)Footnote3 space (McDougall et al., Citation2010a; Wong et al., Citation2019; Kantor, Citation2013). One of the early explorations of GTA in this sector was led by the WorldFish’s Aquatic Agricultural Systems (AAS) program, which in 2012 introduced GTA with smallholder farmers, within its Research in Development approach (Douthwaite et al., Citation2015). This program led early convening, communication and promotion of GTA, bringing together members of CGIAR centers, local and international NGOs, donors, women’s organizations, and other research institutions to co-create a working definition and conceptual model for GTA that built on participants’ observations, experience, and research into structural and normative gender change (CGIAR 2012a,b). In addition, an approach to organizational culture change for the purposes of transformative programming was developed, proposing stages of radically transforming an organization’s structure, culture, practices, composition, in order to undertake gender transformative programming (Cole et al., Citation2014; Sarapura Escobar & Puskur, Citation2014). As the research base on GTA has grown, bilateral as well as philanthropic donors and key AR4D organizations have published studies, guidelines and good practices on GTA (McDougall et al., Citation2023; FAO, Citation2020; Wong et al., Citation2019). In addition, GTA were recognized in the “Top 50 innovations” by the CGIAR of the past five decades.Footnote4 Recognizing that producing normative change takes time and that significant social changes can be incremental or difficult to quantify, there is also a growing body of guidance on adapting dynamic evaluation systems that can better take into account the complexities, multi-directionality, and nonlinear nature of social and normative change (FAO et al., Citation2023; Mullinax et al., Citation2018; Hillenbrand et al., Citation2015). All of these developments suggest that GTA are crossing into the mainstream of gender and agriculture discourse, and that various AR4D organizations research are likely seeking to innovate new, transformative ways of engaging with gender in research and development practice.

In principle, this momentum toward GTA is a promising sectorial evolution, which offers the potential to address systemic social inequalities, integrate broader social inequality perspectives, and apply systems-thinking orientations for greater social impact (Van der Berg, 2020). Indeed, normative change due to the scaling of GTA could take time to unfold and much of this change is difficult to quantify. However, beyond the evident concerns about limited impact evidence, to date there is also a dearth of information regarding why or how GTA have been spreading, socializing, being taken up, and evolving—i.e., how they are “scaling-out” in the AR4D sector. This includes a lack of insight into how GTA are being replicated and potentially strengthened throughout the AR4D ecosystem, and how different actors within the ecosystem influence and push for GTA across the sector. Furthermore, there has been limited examination of the gaps, weaknesses and inefficiencies in the AR4D ecosystem that may be constraining the effective scaling-out of GTA as an innovation. Moreover, unlike some AR4D innovations, GTA are a complex social innovation: they embody evolving strategies oriented toward a suite of institutional, cultural, and structural changes, including incremental and intangible change in norms, potentially at multiple levels, within complex socio-economic systems (Sarapura Escobar & Puskur, Citation2014). Hence, it remains to be seen how actors within the agriculture research ecosystem are interpreting, taking up and disseminating (i.e., scaling-out) core concepts and approaches of GTA.

This paper aims to help address these gaps, shedding light on how complex social ideas and innovations travel and evolve between different actors/organizations within an ecosystem. It starts from the entry point of one of the recognized early adopters of GTA within an informal network of organizations working on agriculture research for development. It presents findings regarding how GTA have been scalingout through the ecosystem of AR4D organizations, the organizational depth of uptake and adaptation of GTA in their programming, and the perceived risks and constraints of integrating GTA. In doing so, it also brings new insight into measuring scaling-out and knowledge-sharing processes within a multi-organization ecosystem. Understanding what motivates or hinders actors in this field to embrace GTA, how they interpret and apply the key principles, and how they share knowledge, experience, outcomes, and strategies to influence other organizations and policies can provide valuable lessons about how feminist ideas—and other social innovations—infuse, are amplified and shared, or deflected by different organizations, each with unique roles and power in the field. This knowledge will be helpful for research organizations and program funders, especially in supporting effective scaling of GTA. As such, this study has implications for AR4D in its commitments to furthering gender equality, including lessons about risks regarding how promising gender and/or development trends may become weakened in the processes of scaling.

How to measure scaling-out of social innovation

Scalingout, also known as horizontal expansion, here refers to the replication or spreading of programs geographically or across organizations. This can occur either through spontaneous adoption or adaptation, or through assistance from active promoters or projects that require facilitation and promotion of an idea or innovation (Riddell & Moore, Citation2015). It differs from scaling-up, which may refer to taking a pilot beyond its experimental stage, with some social impact on target populations in mind, potentially including policy and legal changes (Sartas et al., Citation2020). Most gender-responsive scaling evaluations have been conducted through the lenses of scaling-up achievement. They are mostly measured in the effects on “users” and “non-users,” in terms of whether social inequalities will be exaggerated or lessened, and whether a scaling process is intentional in addressing the potential harms of the innovation (McGuire et al., Citation2022; Badstue et al., Citation2020; Petesch et al., Citation2018). However, GTA represent a "complex social innovation," and assessing how GTA are scaling must go beyond assessment of how particular gender transformative tools or approaches are embraced by end users. It also must engage with the potentially diverse and dynamic interpretations of GTA by the organizations that design and implement them and take into account the interface between and within the organizations. According to McGuire et al. (Citation2022), scaled-out social innovation aims to disrupt practices or create new social relations in the existing external environment, thus, scaling-out any social innovation by default intersects with gender norms and organizational dynamics in the scaling environment.

While there have been some studies on gender-transformative practices and performance in AR4D, as well as a few comparative studies of the social impact of GTA (such as Hillenbrand et al., Citation2023; CARE and ACGSRIA Citation2021; Lecoutere & Wuyts, Citation2021; Cole et al., Citation2020; Kantor et al., Citation2015), no study yet has evaluated how GTA are scaling out within the AR4D organization ecosystem. Tracing the scale-out of GTA in such an ecosystem of organizations is a challenging endeavor for several reasons. First, organizations could have multiple uptake sources, channels, values, and uptake depth. Yet, rigorous methods to measure depth of knowledge uptake are not fully developed in the monitoring and evaluation (M&E) literature (Rogers, Citation2008; CitationSecco et al., 2019). Second, the process through which GTA scale may be complex, driven by internal or external factors, or both (Hillenbrand et al., Citation2015). The complexities may be exacerbated by the fact that the introduction of GTA may be “fortuitous,” which makes tracing the scaling-out process problematic (Sanderson, Citation2000). Furthermore, the social innovation in question—GTA—is not a particular model, toolkit, package, or program; GTA are akin to a paradigm shift in the gender and development perspective and ways of working, based around core principles that align gender and development work more closely to feminist research and theory. As such, it is important not to erroneously conflate the use of any one particular tool or exercise with the broader phenomena of scaling-out GTA in a dynamic and diverse ecosystem of A4RD, donors, and other grassroots organizations that share a mandate to advance equality as part of the sustainable development agenda. Hence, there is a need to develop a unique framework for tracing the scaling-out of GTA within an organization ecosystem.

In general, the development of a framework of why and how social innovations get scaled-out among organizations has received limited research attention. Some noteworthy contributors to this workstream include Voltan (Citation2017), Voltan and De Fuentes (Citation2016), Westermann et al. (Citation2015), Riddell and Moore (Citation2015), and Westley et al. (Citation2014), which show that effective scaling-out of social innovations requires multi-stakeholder platforms and policy-making networks, coupled with capacity enhancement and learning. This literature signals three key questions to ask when measuring how social innovation scale-out: i) why do organizations adopt social innovation? ii) how does social innovation spread? and, iii) how best to analyze the scaling out strategies?

Why do organizations adopt social innovation? Goldstein et al. (Citation2010), and Lichtenstein (Citation2009), identify two drivers for adopting a social innovation in an ecosystem of organizations and networks: “opportunity tension” and “emergence.” In the case of opportunity tension, organizations might adopt social innovations through an inherent passion and drive to create new practices to solve societal challenges, or they might take advantage of societal opportunities. Opportunity tension also includes the combination of externally imposed changes, the availability of potential resources, and internally motivated actions. In the context of adopting GTA, organizations whose mission centers around gender equality may likely adopt gender-transformative principles when they have the resources in terms of human capacity and the financial capital, which is influenced in part by donor demands and consistent funding of gender work. In the second reason, organizations may adopt social innovation through emergence. Emergence comes after a series of iterative cycles of trial, replication and adaptation of social innovations that are communicated by sister organizations whose intent may or may not be to influence others. Before full emergence occurs, the uptake process is usually slow until it reaches a tipping point, whereby a relatively small amount of evidence can catalyze a significant uptake of the social innovation across the network. This study applies this framework to identify the current factors driving the spread of the GTA and to provide insights into the role of networks and collaborations in the scaling-out process.

How does social innovation spread among ecosystem of organizations? From a monitoring and evaluation perspective, it has been argued that social innovation does not scale in a linear or stepwise manner but is instead shaped by a complex interplay of forces and actors (Jones, Citation2011). Here we flag three typologies of social innovation scaling approaches: 1) those that require evidence and advice; 2) those that involve public campaigns and advocacy; and 3) those that involve lobbying and negotiation (Jones, Citation2011). We suggest that a gender-transformative scaling-out strategy could mainly fall within the evidence and advisory approach, since receiving organizations (as part of an AR4D ecosystem) are likely to be influenced by “success story” evidence and knowledge-sharing events to inform policy shifts. In the context of the global AR4D ecosystem, this could mean that a pioneer organization that takes the lead to promote new practices among the AR4D community may do so by communicating success stories and sharing various forms of evidence. The pioneer organizations could also provide technical assistance or advisory support to other community members to reform their practices.

How best to analyze the scaling-out and adoption strategies? Following Jones (Citation2011), it is recommended to start from the “causal chain”-type theory of change. In this theory of change, the pioneers’ or lead organizations’ (or scaling organizations’) research activities are expected to lead to communicable outputs in the form of journal articles, policy briefs, technical guidance notes, or events like seminars, training, and workshops. These outputs would lead to a variety of forms of uptake or use among the related organizations within the network. The analyst’s challenge is to identify the pioneer organizations, measure their power and influence, evaluate the depth of uptake of the innovation by the target organizations, and compare their fidelity to the original model or principles behind the innovation. In this method, the pioneer organizations should be acknowledged as such by other actors, and second, their influence can be measured by reviewing their publications and events and analyzing their credibility, quality, and accessibility to the target audience (that is, the additional adopters). Desk research can reveal organizational contacts and interactions, such as organizations that jointly engaged in or co-financed projects. These organizations reference publications of the pioneer organizations, the works that are frequently cited within the ecosystem, or link to the pioneer organization through events like conferences and webinars. Complementing this desk review, a survey and interviews can also be used to identify indirect contacts as well as the depth of uptake and the fidelity of the scaled approaches to the original model or principles. This methodological approach was adopted in this research.

Methodology

Study design

This study set out to explore how a complex social innovation—specifically GTA—scales-out and is taken up in an ecosystem of organizations engaged in agriculture-related research for development. This ecosystem includes funding agencies, implementing INGOs and local NGOs, agriculture research organizations, especially those that are part of the CGIAR system.Footnote5 In line with the causal chain-type approach outlined above, this study starts from the entry point of one nodal point within this informal network of organizations—WorldFish. Starting the network analysis from WorldFish does not imply that this organization is the sole innovator or pioneer of GTA work within this ecosystem. Many other research and development organizations, local and international, within and without the AR4D sector, had been doing important work on normative and structural change related to gender, which contributed to the formulation of the concept of GTA. Not all of these influencers may have been explicitly identified in this paper. There were practical and strategic reasons to use WorldFish as this starting nodal point. Practically, this decision reflects that the study needed to start somewhere and funding for the research was available from FISH as part of its investment in GTA. Strategically, it made sense to use WorldFish as the entry point because as noted above, it was the earliest of the CGIAR centers to adopt and promote a GTA in the CGIAR (since 2012); it has been recognized as a “pioneer” in developing and scaling GTA throughout the CGIAR system (Wong et al., Citation2019). Additionally, as an applied research center, it straddles the world of applied AR4D, theory, and policy and practice through partnerships and GTA network contacts dating back to 2011.

From the starting point of this one nodal point—an organization with active participation and institutional investment in the intellectual debates about applying GTA and what it takes to do so—we explored the relationships among a constellation of networked organizations to better understand how complex social innovations and ideas are exchanged and shared horizontally. Tracing relationships and scaling strategies, we can understand how knowledge and evidence-sharing processes shapes what is being taken up.

Data collection

We used two methods of tracing the AR4D organizations that have a demonstrated interest in GTA and have direct or indirect links with WorldFish. The first is forward tracing from WorldFish to the target organizations. Here, with the collaboration of WorldFish scientists, we identified 34 organizations that participated in events, conferences, or webinars where the WorldFish staff presented on GTA or have partnered with WorldFish in GTA implementation or joint projects. The second method is through backward tracing from the target organizations back to pioneers of gender-transformative work. Using citation analysis, we identified an additional seven AR4D organizations (i.e., not part of the forward-traced organizations) that have published work on GTA and/or cited WorldFish publications. A total of 41 organizations were therefore traced and participated in the study.

In-depth interviews and a user survey were conducted with a respondent in each selected organization, soliciting information related to influencing strategies (i.e., the communications channels, networking events, and organizations that shaped organizations’ own understanding and uptake of GTA), adoption processes, and the depth of GTA uptake within the organization. We purposively selected respondents with specific responsibility for gender outcomes (gender specialists or gender sector managers), as they would be the most likely to be engaged in inter-organizational research, sharing platforms, and networks related to GTA. Respondents were informed that their organization’s names would be included but their comments would remain anonymous; they also had the opportunity to review the initial draft of the paper. Of the 41 respondents who were invited to participate in the study, 20 did not respond or declined, one provided an incomplete response, 12 completed in-depth interviews with the lead author (an expert in GTA), and 8 elected to complete an online survey, which followed the same questionnaire structure. The final 20 respondents who provided complete responses are affiliated with 19 unique organizations, as shown in . The organizations that completed the interview include CGIAR organizations, INGOs, local NGOs, funding agencies, Rome-based UN organizations, and other AR4D organizations. The online survey questionnaire and the interview schedule were organized in five parts: 1) the organization’s overall level of focus on gender; 2) the organization’s current level of engagement and depth of uptake of GTA; 3) the players who influenced the organization to adopt GTA, and which other organizations did this organization share or influence regarding GTA; 4) the key communications channels used in the scaling of GTA; 5) the motivations and challenges for the adoption of GTA.

Table 1. List of organizations interviewed.

Data analyses

The data were analyzed using a mixed-methods approach. A social network analysis was used to analyze how GTA scales-out within the ecosystem. The social network analysis was done with Social Network Visualizer software, and the Eigenvector centrality prominence index was adopted. The Eigenvector centrality is a measure of the influence of a node in a network. It assigns relative scores to all nodes such that a high Eigenvector score means that a node is connected to many nodes, which are also connected to other nodes with high scores. By calculating nodes connections and extended connections, Eigenvector centrality identifies nodes with influence over the whole network. In our analysis, the node or organization with the highest Eigenvector would have the biggest influence on the scaling of GTA because it is connected to several organizations who themselves are influential. Social network analysis has equally been applied by Hermans et al. (Citation2017) to investigate the structural properties of collaboration, knowledge exchange and influence networks of multi-stakeholder platforms in AR4D.

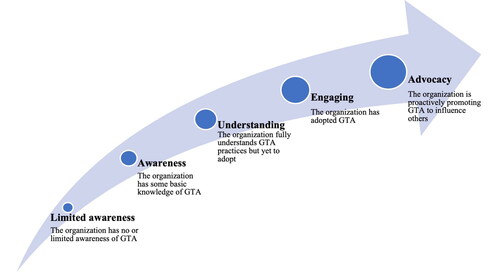

To analyze the qualitative aspects of the dissemination processes (such as the depth of GTA uptake, the main communication channels, the motivation and the challenges of adoption of GTA), transcripts of the in-depth interviews were uploaded into Dedoose software and coded, using deductive codes from the frameworks outlined above, as well as additional inductive codes that surfaced during the discussions. The transcripts were merged with the appropriate open-ended responses from user survey. For assessing the depth of GTA uptake, we inquire how organizations use GTA by the outcomes of their projects and the nature of the strategies applied. Respondents were asked to self-evaluate their organization’s overall placement along the gender continuum in one of three categories (i.e., gender blind, gender accommodative, gender transformative). The 5-point organizational engagement level () scale was used by organizations to self-assess their level of engagement with GTA.

Limitations

The method has two important potential limitations. First, as the study design used WorldFish as the starting point in the network of institutions, this raised a risk relating to the validity and consistency of the SNA results. Specifically, there was a potential risk that respondents would overstate the role of WorldFish due to their awareness of the study’s association with the organization or overlook other organizations that are less influential in the space. The study took measures to address this issue by being transparent about its ownership and giving equal opportunity and pro-active encouragement for all respondents to mention all organizations that play a role in their organizations’ awareness and uptake of GTA or that have influenced them to become aware of or adopt GTA. We acknowledge that there may be other actors in the space whose influence is understated due to the nodal starting point.

Second, in almost all cases, only one respondent per organization was interviewed, so their responses cannot be considered representative of the organization. These responses were self-evaluations and not necessarily official views of the organization. Nevertheless, the purposively selected respondents were the ones most likely to engage in debates and strategies around GTA adoption and had the expertise to speak to their organizations’ engagement in this area. The respondents’ anonymity also gave the respondents the opportunity to speak freely about perceived gaps and constraints within their own organizations.

Results

How GTA scales-out through an ecosystem of organizations

The GTA social network analysis

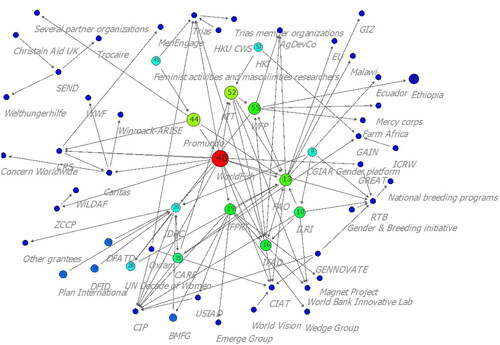

In order to understand the network dynamics, the study utilized the EigenCentrality model of Social Network Analysis (SNA) to show the levels of power and influence different organizations have over the network. The SNA analysis started with 19 unique organizations, but ultimately revealed the presence of over 50 organizations that have some level of involvement with GTA. These organizations displayed a range of integration with GTA, ranging from simply being aware of its existence to actively piloting the approach and even incorporating it into organizational policy. The findings of this analysis are described in greater detail in section 4.2.1.

The SNA elucidates connectivity and influence (relating to GTA) in the ecosystem, categorized into three levels of intensity (). The highest Eigenvector centrality is represented in red in ; it has a wide-reaching influence within the network. One organization (WorldFish) was identified in the SNA at this level, reflecting it being the only one identified as having had strong GTA connections to multiple nodes with high-scoring Eigen-vector centrality (i.e., green nodes), specifically, CGIAR organizations including ILRI, IFPRI, and the CGIAR Gender Platform; Rome-based UN agencies, namely WFP, FAO, IFAD; INGOs such as Promundo, CARE International; and other research organizations, such as KIT. One may wonder if it is inevitable that WorldFish would be the most influential since it was the starting nodal point in the SNA. This does not appear to be the case. In line with the risk-mitigation strategies (see Limitations above), several respondents did not attribute their adoption of GTA to WorldFish. Rather, the scoring as red node emerges from patterns of WorldFish being uniquely involved over time in co-sharing of GTA evidence, including leading joint publications and hosting sharing events within these high scoring nodes. In turn, these high-scoring “green” nodes appear to be better placed to scale GTA evidence to additional organizations (including beyond the red node’s network), due to their global mandates, sectoral breadth and networks. For instance, we found evidence that the green node organizations have scaled GTA to global, regional, and national institutions including the World Bank, the European Union, national government agencies in Ecuador and Ethiopia, and local institutions, which are shown in blue.

One question that arises is whether there are organizations within the given ecosystem that do not have any knowledge-sharing connection with the central red node (here, WorldFish). The response to this question in this case is yes. We found four organizations in the upper left of the SNA that may have a distinct network from the one to which the central node is connected. One implication of having one or more distinct networks identified here in the scaling of GTA is the possibility of having different foundational understandings and interpretations of gender-transformative principles and practices. This is further explored in the Discussion section.

Tracing GTA influence in relation to a pioneer

Most respondents explained that their organizations’ initial exposure to GTA was relatively recent—ranging from 2 to 10 years ago. There was agreement that the use of the term “GTA” has exploded quite recently, within the past 4–5 years. Most of the respondents could pinpoint a specific learning event, organizational commitment, or project that introduced the terminology and concepts to their organization, such as a strategic plan with GTA targets or a pilot project that offered staff technical assistance on GTA. A few organizations (including UN, donor, and NGO representatives) pointed out that they have been working on social transformation and social norms issues well before the use of the GTA term became commonplace; from their perspective, they are the “innovators” in the transformative space, but there is a sense that the type of gender work that they have been doing has been eclipsed by the new interest in the terminology of GTA.

Here we looked at the extent to which the starting nodal point in the ecosystem (in this case, WorldFish as the “red node” and an identified pioneer) has influenced the scaling of GTA. We note that the perceptions of who influences whom is a subjective matter, and thus may be perceived differently from the “influencer” and those “influenced by” GTA-promoting organizations. With this study, we focus on self-reported adoption and influence, rather than attempting to classify the gender-transformative interventions and outcomes as such. The results show a combination of no recognized influence, indirect influence, and direct influence in the ecosystem.

The red node was perceived as an influential catalyst for knowledge-sharing and innovation around GTA, through its practices such as publications and implementation of joint programs, which generated lessons learned as well as new GTA champions. At the same time, the conceptual development of GTA in the red zone was informed by INGOs like Promundo, HKI, and CARE, which were mentioned as particularly influential in testing GTA and sharing good practices and lessons learned (including on measurement of GTA) in the AR4D sector. The direct and extended networks of the more influential and dominant organizations like the Rome-based UN organizations and the CGIAR gender platform, which are more connected to many other organizations, also played vital roles in motivating awareness and interest in GTA. At the same time, respondents also mentioned some smaller NGOs that have less recognition in the ecosystem but who were doing innovative and transformative gender work; these organizations may not be promoting the work as GTA, and their voices and lessons may be overshadowed by the larger organizations.

In terms of central influences, two NGOs indicated that they were not primarily influenced by the starting node (WorldFish Center). Rather, one national NGO indicated they had been influenced by an organization outside this network, namely Christian Aid UK and Ireland. The other INGO indicated that their organization was itself a pioneer in GTA, having integrated GTA practice from masculinities research:

[We] pioneered gender-transformative approaches to engage men and boys in Brazil and other countries in the late 1990s, but along the way, we have been very much influenced by the work of feminist activists and masculinities researchers from Latin America, Sub-Saharan Africa, and the Middle East/North Africa. In particular, social welfare programming from South America has made us think about how to integrate GTA at a large scale. Emerging research from these regions has also informed how [our organization] evaluates and innovates its programming as it relates to women’s economic empowerment, men’s caregiving, in the workplace, and ending VAWG. (INGO respondent)

[World Fish] increased the use of the terminology but I am not sure that they influenced [our] use of it directly. They probably influenced the discourse. We tend to have a different language to describe what we are doing—we say that social norms are changing. I am personally not comfortable putting things in boxes. In my work, we have been looking at the normative change since the 2000s. Would you call that transformative? (CGIAR respondent)

A broader theme that emerged was around overall momentum-building, which was attributed to a combination of direct and indirect influence. A number of respondents (especially CGIAR respondents) credited the thought leadership, academic outputs, and political leadership of the red node organization (WorldFish) in maintaining the momentum around gender transformative work across the CGIAR system. Some credited specific researchers as champions of gender transformative work in the CG system:

The work of WorldFish has been very important—for keeping [GTAs] on the radar within the system. Just to get people looking in the same direction, speaking the same language. What I appreciate from WorldFish is there have been some committed people who consistently build up that body of work and keep it on the agenda. (other AR4D organization)

GTA scaling-out and knowledge-sharing strategies

Here, we explored how GTA-related information (concepts, theory, good practices, and lessons learned) evidence is communicated within the network. We found that direct scaling strategies, such as intra-agency joint initiatives and research partnerships, appeared to be the most influential and valued scaling strategy in encouraging organizations to make sense of and start engaging with and integrating GTA. Additionally, participants signaled that lateral learning and collaborative influence among networks of similar organizations had been important in their journeys toward GTA. For example, the Rome-based agencies reported having influenced one another and their partners to consider GTA in their priorities through their publications and joint programs; funding agencies mentioned joint funding agency meetings as important spaces for sharing ideas and strategies on gender-transformative approaches and indicators.

A third form of direct scaling-out and sharing was formal capacity-building and other direct engagements, such as sharing sessions with partners. This was noted in particular by NGO respondents, such as this one:

We organized training (of trainers), coaching and sessions for peer-to-peer support. We also compiled educational modules on gender and inclusion. In some contexts we also inspired partners to engage in campaigns against gender-based violence. (NGO respondent)

Respondents also identified the complementary role of indirect strategies in sharing or learning about GTA. These included communications, such as research publications, training modules and other written dissemination channels including newsletters and technical papers. Additionally, some respondents who were working on GTA in their previous jobs introduced the approach and have been informally influencing colleagues in their current jobs to move toward GTA. For example, two CGIAR respondents successfully lobbied their organizations to move toward GTA, using knowledge they gained from previous employment. Moreover, some grantee respondents identified that funding agreements can also influence organizations to adopt GTA. Funding agency respondents similarly reported that they influenced others through joint funding activities, and they influenced recipient governments through awards to strengthen gender approaches and think about moving toward GTA. Funding agency respondents in turn reflected that they learned about GTA from the INGOs, NGOs, and research organizations that they fund:

[Our learning and influence] is two-fold: Through our grantees, at the project level, our capacity building and training, and changing our hiring policies, etc. We also work with a lot of donors on new programs—especially in joint-funding programs, we’ve added a lot of comments on gender, but they recognize that they need to strengthen that area. With other donors, we’ve also been influenced in terms of our larger signing agreements…. We’ve influenced other donors in terms of programs that we want to fund together. (funding agency respondent)

The motivation and drivers of GTA adoption

We identified three main drivers or motivations for the shift from “business as usual” gender approaches to GTA. These drivers include the funding agencies’ priorities and backing, organizational interest, and personal motivations. Most respondents agreed that there is a great deal of momentum and movement toward adopting GTA (and more broadly, toward more gender-responsive work) in the agriculture research for development sector. Funding agencies’ backing and institutional commitments to tracking and reporting on gender outcomes were identified as one of the primary motivating factors that were contributing to that momentum. Several respondents underscored that having funding agencies’ backing gave them (as GTA advocates) greater support to push for more transformative approaches. Additionally, respondents also identified that having gender networks and communities of practice across complex institutions provides moral support and encouragement to gender advisors, who often find themselves isolated in their organizations:

My team has a donor from GIZ who says that gender is important. If SHE says it, everyone cares. If I say it, nobody cares. There was a time when we were devising the budget package—I was looking at what percentage goes to gender. If the donor is on the team, then I can copy her in that, and get a standard budget for gender (20%). But if I struggle alone, I don’t get anywhere. (CGIAR respondent)

Finally, beyond the funding agencies’ backing and leverage for organizational mandates, many respondents indicated that there is a genuine and often personal passion within the ecosystem, which sustains the growing momentum and interest in GTA work across the sector. Moreover, in contrast to the above reference to struggle, in some cases, this personal motivation is seen as less isolated than it used to be. Many respondents across the board noted a broader organizational cultural shift toward taking responsibility for gender outcomes across the sectors, as one funding agency respondent noted:

There’s absolutely been a shift in culture—I see it happening, and there is a keen interest. In the past, people would say “oh, that’s the gender stuff, [the gender person] will deal with that” but the technical people [now] cannot escape it, you have to take responsibility. (funding agency respondent)

Organizations’ depth of adoption and adaptation of GTA

Respondents’ self-reported level of uptake of GTA in their organization

We asked respondents to identify where they feel that their organization currently falls overall on the continuum from gender-blind, to gender-accommodative, to gender-transformative orientation at the time of the survey. The majority of the respondents (n = 16) identified their organizations as gender-accommodative in their approach to addressing gender and doing gender-related research. Most respondents were highly cautious about claiming the label of GTA. Only respondents from three organizations (all INGOs or NGOs) self-identified as gender-transformative, while one respondent (a CGIAR respondent) identified their organization as “completely gender-blind,” expressing frustration with what they saw as a lack of genuine commitment within the organization.

The INGO and NGO respondents who categorized their organizations as being on the “gender-transformative” end of the continuum self-reported their organizations as “leads” or “promoters” of GTA, often because they had been using household methodologies that challenge traditional notions of gender roles and responsibilities. Funding agency and UN agency respondents indicated that, overall, their organizations are still working within gender mainstreaming frameworks (based in gender accommodative, including women’s empowerment, approaches), but they are making specific organizational commitments to pilot and move toward GTA either through financial commitments, pilot projects, or addressing staff balance. Across the CGIAR organizations, respondents were familiar with the term GTA, but none was ready to label their center (or the CGIAR system as a whole) as gender transformative. Respondents did identify particular CGIAR centers (especially WorldFish, ILRI, IWMI) as being more actively engaged with GTA than others. Some felt that the variability in gender-responsiveness across the CGIAR system has to do with whether a center is commodity-focused or systems-focused, noting that in the more “technical” or single-commodity focused programs, there was generally less interest or capacity for doing deep gender work.

Another approach we used to determine the depth of uptake of GTA was the five-level stakeholder engagement framework (see ). Respondents were explicitly asked about how they perceived their organization’s current application of GTA. The options range from having limited awareness of GTA approaches to being fully aware of and disseminating the approaches to other organizations. Only two respondents felt that their organization had no or limited GTA awareness. Likewise, only two said their organization fully applies GTA and advocates other institutions and stakeholders to initiate GTA. Six respondents said that there was “some awareness” of GTA but not in-depth knowledge. Five respondents indicated that they were “fully aware of GTA and have advanced understanding of the principles and practices.” Five indicated that they are actively engaging with GTA to some degree, in policy and research.

summarizes some of the respondents’ views concerning their organization’s level of engagement with GTA. Interestingly, funding agencies claim to be actively engaging GTA in their portfolios (and by default influencing other organizations), although they did not claim to be playing an advocacy role in the space. All of the CGIAR respondents except one self-reported that their organizations are at level 2 (some awareness and understanding of the GTA practices).

Table 2. Self-representations of organization engagement with GTA.

Organizational actions in preparation for GTA adoption

Several respondents indicated that their organizations have made some changes in preparation for fuller adoption of GTA. These preparations included implementing gender-transformative pilot projects or learning initiatives and instituting changes to their organization’s policies and practices.

Pilot programs and targeted learning initiatives

First, many organizations that were starting to apply GTA did so through pilot programs and targeted learning initiatives. Notably, the Rome-based organizations, the funding agencies, and the CGIAR Gender Platform were implementing gender-transformative programming in a subset of programs or had a specific learning agenda for improving their organizational knowledge of GTA approaches. Organizations that had formal gender-transformative targets or pilot programs were able to give clear and comprehensive criteria for what distinguished “accommodative” projects from gender transformative ones. They emphasized addressing political dimensions, power relations, and social norms; having a community-led orientation; and seeing gender and social dialogue as intrinsically valuable processes (not instruments for other development outcomes). For those engaging with gender-transformative programs and pilots, gathering measurable evidence of the differential gender outcomes was expressed as important, although several seemed to be relying on standardized or instrumental measures of empowerment (variations of the WEAI) rather than gender-transformative change-focused monitoring and dynamic evaluation tools. Other respondents (including CGIAR and NGO partners) that did not have GTA pilot programs or a full engagement with GTA explained that they had nonetheless started to apply some related methods in their programs, especially the GALS methodology, Community Conversations, or associated research tools such as the GENNOVATE toolkit.

Programs and institutional practices

Respondents from all the organizations concluded that gender (if not necessarily GTA) is currently taken more seriously as an organizational objective and as a funding agency mandate than it used to be. Many respondents were able to relay new or ongoing actions that support gender mainstreaming overall in their organization’s work. These include new reporting forms, screening questions, and checklists to strengthen gender programs and outcomes; learning sessions on intersectionality and gender-responsive budgeting; including gender equality as a strategic outcome area in strategic plans; hiring designated gender experts; set up gender working groups and communities of practice; and addressing gender and inclusion issues with staff. In addition, respondents across the board identified some actions that were more oriented to reflect GTA principles or to prepare for fuller engagement with GTA. These are outlined here.

Including GTA in strategic plans: Several organizations (notably, large UN agencies and funding agencies) indicated official commitments to making gender and GTA a more prominent part of their strategic plans. Both funding agency respondents stated that their organizations have official targets for increasing the subset of gender-transformative projects and making sure that such activities are fully budgeted. A UN respondent mentioned that GTA are included in the Strategic Framework for Priority Program Areas.

Adapting theories of change and program design processes: One NGO respondent indicated that the organization was developing a new theory of change and learning agendas that tackle root causes and systemic change, which they considered to be much in line with the principles of gender-transformative change. Another respondent highlighted that their organization is incentivizing the shift to GTA by certifying, rewarding, and publicly recognizing successful projects that meet the criteria of GTA.

Changes in community engagement processes: Respondents whose organizations were actively implementing gender-transformative research and development projects stated that they had changed how they engage and partner with communities in relation to gender. For instance, some had started setting up community committees on gender, involving communities in setting priorities for development programs, working with traditional community leaders (often men) on gender, or offering capacity building on gender-transformative tools and approaches to partners and local leaders.

Refining monitoring, evaluation, and learning systems: Several respondents said that their organizations were making changes to monitoring, evaluation, and learning (MEL) practices so that they are more compatible with GTA. Specifically, some organizations were exploring conceptual frameworks and measurement approaches (qualitative, participatory, Outcome Mapping, Most Significant Change, feminist political ecology) that they considered to be more able to capture gender transformative change, rather than only measuring sex- or gender-disaggregated involvement or benefits or women’s empowerment.

Internal organizational reflection processes: A few respondents indicated that their organizations were exploring gender equality incentive mechanisms to transform in organizational culture in alignment with GTA. For example, one organization was also exploring institutional change processes to address unconscious bias in the workplace. Two organizations (NGOs) stated that their organizations were going through institutional decolonization processes, which forced them to reflect on historical power dynamics and gendered and racial hierarchies within their own organizations. While not specifically on gender, the nature of these processes, they felt, were in alignment with the principles of GTA, particularly the emphasis on self-reflection (of individuals and at the level of organization) on power relationships.

Risks and constraints of integrating GTA

Despite the notable momentum for applying GTA across the AR4D organizations surveyed, there were likewise a number of identified challenges, hesitations and concerns—including concerns about the rapid uptake of GTA. While some of these obstacles relate to gender mainstreaming overall, they also have specific GTA-related dimensions, which are highlighted here:

Inconsistent application

The most emphatically identified concern about the spread of GTA across the network was what respondents saw as the inconsistent application and definition of the terminology, principles, and practices of GTA. This was a notable concern expressed by many gender specialist respondents, who perceived that the terminology of GTA is scaling rapidly, but without the necessary consistency, depth, and shared understanding of what GTA means and involves. In other words, there is a risk that the use of the term is scaling faster than, or disassociated from, its radical substance. The range of responses in the study also underscore this as an issue: When asked to describe GTA in their own words, respondents showed varied depth of understanding and meanings—despite this being a purposively selected group of organizations that have a declared interest in applying GTA. Other respondents noted that as GTA gains funding agencies’ attention, there is a tendency to retroactively label an organization’s gender-responsive approaches as “transformative,” without the accompanying shift in vision, strategy, or resources.

Funding and time constraints

Eight respondents mentioned financial constraints and funding shortages as a key obstacle to adopting GTA responsibly. One respondent from an NGO noted that because investing in gender does not necessarily produce a financial, productivity, or economic impact, some funding agencies are reluctant to adequately budget for gender-transformative work. Several respondents stated that their organizational leadership assumes that gender activities do not cost much or that they can be financed through other programs, even though doing GTA often takes a longer time and deeper investment in communities. Many respondents stated that they relied on external rather than core funding for gender-transformative initiatives, which made such interventions less stable and secure in the long run.

Lack of support and career advancement for gender expertise

The lack of support, recognition, and career prospects for gender experts was an area of deep discouragement for some respondents, particularly those within the CGIAR system in crop-focused research programs. Several indicated that even with cross-cutting gender agendas, most organizations were understaffed when it comes to specialized gender expertise. The lack of investment in gender expertise was seen as a vicious cycle, making it prohibitive to securing long-term funding and investment in capacity for the type of intensive commitment, effort, and depth of expertise that GTA requires.

Several gender specialists voiced frustration at the general lack of respect and career progress for gender specialists, which ultimately limits the uptake and scaling of GTA. While non-gender expert respondents were frustrated with trying to learn more about gender on the job in order to meet increasingly extensive gender requirements, gender specialists felt that their expertise was being devalued and seen as something that can be mastered in a short gender-sensitization training. They emphasized the importance of recruiting dedicated gender specialists to meet the considerable demands required to scale GTA effectively:

I always say that we need to hire the right person—everyone knows that statistics are important—but you need to hire a statistician. I’m going to teach you how to talk about gender, to understand how to understand it–but I’m not going to make you a gender specialist. (CGIAR respondent)

Organizational size and bureaucracy

A number of respondents hypothesized that the institutional size and bureaucracy of organizations determines the uptake and depth of institutionalization of GTA approaches. They pointed out that on the one hand, the influence of large influential organizations (such as donors or the Rome-based agencies) can be momentous: once such organizations have institutional mandates around a given approach (such as GTA), the influence is felt throughout the ecosystem by their partners. On the other hand, internalizing GTA principles within the organization, such as reflexivity on organizational culture and gender, was perceived to be easier within nimbler, smaller organizations—particularly NGOs that engage with partners and communities on the ground.

Challenges of culture, power and influencing gatekeepers

Respondents saw the inherently political nature of gender-transformative work running up against the internal politics and male-staffing biases of their organizations. Even with strong institutional mandates, donor guidance, gender action plans, and gender expertise in place, some felt that commitments to gender are systematically deprioritized. Respondents noted that while finding and nurturing champions can facilitate scaling GTA within the institutions, certain influential stakeholders can also be gatekeepers, blocking meaningful engagement with GTA.

Discussion

While this study has raised several interesting findings, we opt to take a deep dive on two key areas. The first is how and why GTA are scalingout through an ecosystem of organizations. Our study finds that the way that GTA is currently spreading through the AR4D ecosystem is nonlinear; it involves the complex interactions of multiple organizations making a range of contributions, on different timeframes, and being exposed to and differently recognizing various and combined influences, both at the organizational and ecosystem level. However, actors could identify the influential organizations or channels including events, key documents, or mandates that had sparked their own organization’s awareness of GTA. In line with Voltan (Citation2017), the findings point to two important factors that influence how GTA is spreading and the perceived outcomes of its scaling: the passion and persistence of champions, and the organization’s mandate and agency. First, the passion and persistence of specific research programs or organizations and particular individuals within the research organizations were important factors in keeping GTA “on the radar.” The persistence of these “GTA champions” was critical both in generating evidence, as well as getting other actors “looking in the same direction,” thus shifting agendas and consolidating the discourse. Perhaps a surprise finding was the role of particular individuals in scaling: as key champions and influencers of GTA moved from one organization to another in the ecosystem, they also scaled out the innovation by bringing with them capacity and experience as well as passion to motivate other actors. As funding mandates in the broader ecosystem shifted, these champions could also leverage those opportunities to influence their own (new) organizations. Second, organizational mandates and agency were important in shaping the extent they influence other networked organizations. As noted in the findings, larger organizations—notably the Romebased UN agencies and funding agencies—were credited with promoting GTA throughout the ecosystem, thanks to their global mandates, sectorial breadth, and extensive networks. On the other hand, smaller and perhaps less-central actors (notably NGOs and smaller research organizations) were perceived to be more open to the type of political and organizational change and self-reflection processes that principles of GTA entail; they were also perceived to be nimbler and better positioned to test and innovate GTA through pilot projects. This is in line with the “opportunity tension” and “emergence” model (Lichtenstein, Citation2009), which speaks to how social innovations scale-out through inherent passion and drive to replicate and to adapt social innovations communicated by larger nodes in the social network, whether they intend to influence others or not.

The second issue we discuss is the perceived constraints and risks of the current scaling-out GTA. Our study surfaced serious reservations about the rapid uptake of gender-transformative terminology and the associated risk of losing the depth and transformative power of the concept as it scales through this ecosystem. The study surfaced genuine enthusiasm about GTA within the sector, which seems to be part of a longer sectorial transition to recognizing the importance of “doing gender” well in agriculture development (even if that progress is also seen as uneven and challenged by more techno-focused gatekeepers or certain organizational cultures). On the other hand, this study also highlights precautions and deep concerns, particularly about the tendency to apply the terminology of GTA to gain funding agencies’ approval or to capitalize on a development trend, while not really following through in practice or truly recognizing the investment in time, effort, and expertise that GTA entails. As with gender mainstreaming, women’s empowerment, human-centered development, and other trending terms in development, there is a tendency for critical, pointed terms to lose their specific meaning and radical intent when “mainstreamed” into practice and taken up by development institutions (Cornwall, Citation2007). This was identified as a major source of disappointment and frustration by gender experts, who emphasized that pushing for gender-transformative interventions, when organizations are still struggling to adequately fund, staff, and implement gender-responsive approaches, is a disservice to all. Diverting investments intended for substantive and systemic change to “empowerment lite” (Cornwall, Citation2018) via a change in terminology hinders progress toward sustainable development at a juncture when equality has been set back, and development outcomes that rely on equity and equality (such as climate adaptation) are precarious and critical. Moreover, this tendency poses a significant potential risk to communities, and to women in particular, given that intervening to address social norms and power dynamics without deep contextual understanding, gender expertise, long-term engagement, and thoughtful and methodical research processes can produce very real harms and backlash (Goldmann et al., Citation2019), not to mention reinforce global north-south power dynamics around the production of knowledge (Wazir, Citation2023). Underlying these risks is the longstanding issue of resource constraints and disciplinary and sectorial hierarchies. This echoes wider ongoing development challenges of technological versus social science silos in agriculture research and development, with gender expertise being chronically understaffed, overstretched, underfunded, or under-valued (WEF Citation2022). As surfaced above, there is a potential danger of undermining the promise of GTA, if there is a premature push for organizations to embrace gender-transformative change when many organizations are still struggling to commit to adequate funding and staffing to implement gender-responsive approaches. It seems likely that a meaningful paradigm shift to GTA will have to go hand-in-hand with resolving this longstanding development challenge.

Conclusion

Our study examines how a complex social innovation—GTA—is moving through the AR4D ecosystem. The study confirms that there is indeed momentum for shifting toward GTA across the ecosystem. Actors are motivated and eager for ways to shift away from prior, more superficial gender approaches and to embrace GTA as an innovation that can engage more systemically and structurally with equality as a core development challenge and commitment.

The study finds that the scaling-out of social innovation through an ecosystem of organizations is often nonlinear; it involves a complex interaction of contributions from individual organizations operating on different timelines, with each organization being exposed to and differently recognizing various and combined influences, both at the organizational and ecosystem level. For GTA specifically, the study points to the passion and persistence of particular stakeholders and an organization’s mandate and agency as two important factors that influence both how GTA is spreading and the perceived outcomes of its scaling.

Given the precarity of advances to date toward gender equality, the momentum of GTA as an innovation that can better address root causes of inequality is significant. And yet, our study also cautions that momentum without consistent, in-depth understanding of how GTA is a departure from (and not a re-branding of) more common gender approaches—like enthusiasm without the associated investment in and enabling environments for the required expertise—risks emptying out the radical intent of the innovation and undermining its potential to drive systemic change. Paramount to the ethical and effective scale-out of GTA are the continued diverse and synergistic contributions, collaboration, learning across diverse actors about the core principles of GTA; making the necessary long-term investments (technical, political, and financial) to implement GTA; and addressing the older sticky barriers around gender equality as a priority within the AR4D ecosystem.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their appreciation to the anonymous peer reviewers of the journal who offered very useful guidance. We also express gratitude to Dr. Miranda Morgan and Dr. Steven Cole for their invaluable expertise and contributions to shape the revisions of the manuscript. Additionally, the authors extend their sincere thanks to the respondents who generously shared their insights through key informant interviews.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

2 Gender mainstreaming, not to be conflated with a gender approach, "involves the integration of a gender perspective into the preparation, design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of policies, regulatory measures and spending programmes, with a view to promoting equality between women and men, and combating discrimination." https://eige.europa.eu/gender-mainstreaming/what-is-gender-mainstreaming

3 AR4D organizations use scientific research to build resilience and increase food and overall livelihood security of small holders in rural communities.

5 CGIAR is a global research partnership for a food-secure future dedicated to transforming food, land, and water systems in a climate crisis, it has 15 research centers globally with presence in 89 countries.

References

- Badstue, L., van Eerdewijk, A., Danielsen, K., Hailemariam, M., & Mukewa, E. (2020). How local gender norms and intra-household dynamics shape women’s demand for laborsaving technologies: Insights from maize-based livelihoods in Ethiopia and Kenya. Gender, Technology and Development, 24(3), 341–361. https://doi.org/10.1080/09718524.2020.1830339

- Barker, G., Ricardo, C., Nascimento, M., Olukoya, A., & Santos, C. (2010). Questioning gender norms with men to improve health outcomes: Evidence of impact. Global Public Health, 5(5), 539–553. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441690902942464

- CARE Burundi and Africa Center for Gender, Social Research and Impact Assessment. (2021). A win-win for gender, agriculture and nutrition: testing a gender-transformative approach from Asia in Africa. Impact evaluation report. CARE. https://careevaluations.org/wp-content/uploads/Win-Win-Impact-Evaluation.pdf

- Casey, E., Carlson, J., Two Bulls, S., & Yager, A. (2018). Gender transformative approaches to engaging men in gender-based violence prevention: A review and conceptual model. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 19(2), 231–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838016650191

- CGIAR Research Program on Aquatic Agricultural Systems. (2012a). Building coalitions, creating change: An agenda for gender transformative research in development. Workshop Report, 3-5 October 2012, Penang, Malaysia. Workshop Report: AAS-2012-31.

- CGIAR Research Program on Aquatic Agricultural Systems. (2012b). CGIAR research program on aquatic agricultural systems gender strategy brief – A gender transformative approach to research in development in aquatic agricultural systems. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10<?sch-permit JATS-0034-007?>.1080/14735903.2017.1336411

- CGIAR. (2023). Available at: https://www.cgiar.org/innovations/gender-transformative-approaches/. Assessed Jan 30.

- Cole, S. M., Kaminski, A. M., McDougall, C., Kefi, A. S., Marinda, P. A., Maliko, M., & Mtonga, J. (2020). Gender accommodative versus transformative approaches: A comparative assessment within a post-harvest fish loss reduction intervention. Gender, Technology and Development, 24(1), 48–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/09718524.2020.1729480

- Cole, S., Kantor, P., Sarapura, S., & Rajaratnam, S. (2014). Gender-Transformative Approaches to Address Inequalities in Food, Nutrition, and Economic Outcomes in Aquatic Agricultural Systems.” CGIAR Research Program on Aquatic Agricultural Systems.

- Cornwall, A. (2018). Beyond “empowerment lite”: Women’s empowerment, neoliberal development and global justice. Cadernos Pagu.

- Cornwall, A. (2007). Buzzwords and fuzzwords: deconstructing development discourse. Development in Practice, 17(4-5), 471–484. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614520701469302

- Douthwaite, B.; Apgar, J.M.; Schwarz, A.; McDougall, C.; Attwood, S.; Senaratna Sellamuttu, S.; Clayton, T. (eds.) (2015). Research in development: learning from the CGIAR Research Program on Aquatic Agricultural Systems. CGIAR Research Program on Aquatic Agricultural Systems. ” Working Paper: AAS-2015-16.

- FAO. (2020). Gender transformative approaches for food security, improved nutrition and sustainable agriculture – A compendium of fifteen good practices. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- FAO. (n.d.), Available at www.fao.org/joint-programme-gender-transformative-approaches/overview/gender-transformative-approaches/en. Accessed Jan 30, 2023.

- FAO, IFAD, WFP, and CGIAR GENDER Impact Platform. (2023). Guidelines for measuring gender transformative change in the context of food security. Nutrition and Sustainable Agriculture.

- Giusto, A., & Puffer, E. (2018). A systematic review of interventions targeting men’s alcohol use and family relationships in low- and middle-income countries. Global Mental Health, 5, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2017.32

- Goldmann, L., Lundgren, R., Welbourn, A., Gillespie, D., Bajenja, E., Muvhango, L., & Michau, L. (2019). On The CUSP: The politics and prospects of scaling social norms change programming. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters, 27(2), 1599654–1599663. https://doi.org/10.1080/26410397.2019.1599654

- Goldstein, J., Hazy, J. K., & Silberstang, J. (2010). A complexity science model of social innovation in social enterprise. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 1(1), 101–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420671003629763

- Hermans, F., Sartas, M., van Schagen, B., van Asten, P., & Schut, M. (2017). Social network analysis of multi-stakeholder platforms in agricultural research for development: Opportunities and constraints for innovation and scaling. PLoS One, 12(2), e0169634. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0169634

- Hillenbrand, E., Mohanraj, P., Njuki, J., Ntakobakinvuna, D., & Tasew Sitotaw, A. (2023). “There is still something missing”: Comparing a gender-sensitive and gender-transformative approach in Burundi. Development in Practice, 33(4), 451–462. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2022.2107613

- Hillenbrand, E., Karim, N., Mohanraj, P., & Wu, D. (2015). Measuring gender-transformative change: A review of literature and promising practices. Working Papers, (October), 1–52. https://care.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/working_paper_aas_gt_change_measurement_fa_lowres.pdf

- Interagency Gender Working Group (IGWG). (2017). Gender integration continuum training session user’s guide. IGWG and USAID. Retrieved from https://www.igwg.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/17-418-GenderContTraining-2017-12-12-1633_FINAL.pdf

- Jones, H. (2011). A guide to monitoring and evaluating policy influence. ODI Background Note. Retrieved from http://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/6453.pdf

- Kabeer, N., & Subramanian, R. (1996). Institutions, relations and outcomes: Framework and tools for gender-aware planning. Discussion Paper 357, September 1996. Institute of Development Studies.

- Kantor, P. (2013). Transforming gender relations: Key to positive development outcomes in aquatic agricultural systems. CGIAR Research Program on Aquatic Agricultural Systems.

- Kantor, P., Morgan, M., & Choudhury, A. (2015). Amplifying outcomes by addressing inequality: The role of gender-transformative approaches in agricultural research for development. Gender, Technology and Development, 19(3), 292–319. https://doi.org/10.1177/0971852415596863

- Lecoutere, E., & Wuyts, E. (2021). Confronting the wall of patriarchy: Does participatory intrahousehold decision making empower women in agricultural households? The Journal of Development Studies, 57(6), 882–905. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2020.1849620

- Lichtenstein, B. B. (2009). Moving far from far-from-equilibrium: Opportunity tension as the catalyst of emergence. E:CO Emergence: Complexity and Organization, 11(4), 15–25. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umb.edu/management_wp/13

- MacArthur, J., Carrard, N., Davila, F., Grant, M., Megaw, T., Willetts, J., & Winterford, K. (2022). Gender-transformative approaches in international development: A brief history and five uniting principles. Women’s Studies International Forum, 95, 102635. November) Pergamon. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2022.102635

- McDougall, C., Newton, J., K. F., & Reggers, A. (2021a). Gender integration and intersectionality in food systems research for development: A guidance note. CGIAR Research. Program on Fish Agri-Food Systems. Manual: FISH-2021–2026.

- McDougall, C., Badstue, L., Elias, M., Fischer, G., Joshi, G., Pyburn, R., Mulema, A., & Najjar, D. (2021b). Beyond gender and development: How gender transformative approaches in agriculture and natural resource management can advance equality. In R. Pyburn, and A. van Eerdewijk (Eds.), How can agriculture and natural resource management contribute to gender equality? Lessons from the CGIAR. International Food Policy Research Institute. https://www.ifpri.org/publication/toward-structural-change-gender-transformative-approaches

- McDougall, C., Elias, M., Zwanck, D., Diop, K., Simao, J., Galiè, A., Fischer, G., Jumba, H., & Najjar, D. (2023). Fostering gender transformative change for equality in food systems: A review of methods and strategies at multiple levels. CGIAR GENDER Platform Methods Working Paper. CGIAR GENDER Platform.

- McGuire, E., Rietveld, A. M., Crump, A., & Leeuwis, C. (2022). Anticipating gender impacts in scaling innovations for agriculture: insights from the literature. World Development Perspectives, 25, 100386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wdp.2021.100386

- Mullinax, M., Hart, J., & Garcia, A. V. (2018). Using research for gender-transformative change: Principles and practice. International Development Research Center (IDRC) and American Jewish World Service. (AJWS).

- Njuki, J., Kaler, A., & Jenkins, J. (2016). Transforming gender and food security in the global south. Routlege, Earthscan.

- Pederson, A., Greaves, L., & Poole, N. (2015). Gender-transformative health promotion for women: A framework for action. Health Promotion International, 30(1), 140–150. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dau083

- Petesch, P., Badstue, L., & Prain, G. (2018). Gender norms, agency. And innovation in agriculture and natural resource management: The gennovate methodology. CIMMYT.

- Riddell, D., & Moore, M. L. (2015). Scaling out, scaling up, advancing systemic scaling deep: Social innovation learning processes to support it. Prepared for the J.W. McConnell Family Foundation & The Tamarack Institute for Community Engagement.

- Rogers, P. J. (2008). Using programme theory to evaluate complicated and complex aspects of interventions. Evaluation, 14(1), 29–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389007084674

- Rottach, E., Schuler, S. R., & Hardee, K. (2009). Gender perspectives improve reproductive health outcomes: New evidence. Population Reference Bureau. Http://Www.Igwg.Org/Igwg_media/Genderperspectives.Pdf.

- Ruane-McAteer, E., Amin, A., Hanratty, J., Lynn, F., Corbijn van Willenswaard, K., Reid, E., Khosla, R., & Lohan, M. (2019). Interventions addressing men, masculinities and gender equality in sexual and reproductive health and rights: An evidence and gap map and systematic review of reviews. BMJ Global Health, 4(5), e001634. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001634

- Sanderson, I. (2000). Evaluation in complex policy systems. Evaluation, 6(4), 433–454. https://doi.org/10.1177/13563890022209415

- Sarapura Escobar, S., & Puskur, R. (2014). Gender capacity development and organizational culture change in the CGIAR research program on aquatic agricultural systems: A conceptual framework. Working Paper: AAS-2014-45, https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.2586.3201

- Sartas, M., Schut, M., Proietti, C., Thiele, G., Leeuwis, C., & Group, I. (2020). Scaling readiness: Science and practice of an approach to enhance impact of research for development. Agricultural Systems, 183(August), 102874. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2020.102874

- Secco, L., Pisani, E., Da Re, R., Rogelja, T., Burlando, C., Vicentini, K., Pettenella, D., Masiero, M., Miller, D., & Nijnik, M. (2019). Towards a method of evaluating social innovation in forest-dependent rural communities: First suggestions from a science-stakeholder collaboration. Forest Policy and Economics, 104, 9–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2019.03.011