ABSTRACT

Research into how to support student teachers to work with diverse school students frequently uses a narrow, Anglocentric lens based on binary language speaker labels. This lens limits understandings of the complex factors impacting any individual’s ability to teach inclusively. Given the increases in diversity in the tertiary sector, we therefore sought to explore four teacher educators' perceptions of two inclusive literacy activities they taught that drew on their students’ rich knowledge in, and of, English to understand multilingual classrooms. An experiential checklist was employed to thematically analyse the psychological and sociocultural classroom experiences together with Bourdieu’s habitus and field theories with key findings revealing key aspects in activity design both affirmed and challenged some participants’ thinking. However, critical in disrupting deficit binaries that position us all as “others” was the need to understand how staff and students see themselves as English language speakers.

Introduction

The importance of preparing student teachers to work with school students from diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds is widely recognised with researchers and policy makers deferring to acronyms in Australia such as Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD), Language Background Other Than English (LBOTE), Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (ATSI), or English as an Additional Language or Dialect (EAL/D). However, we have found that the use of such acronyms inadvertently perpetuates stereotypes and marginalises certain groups in class by categorising individuals into predefined labels linked to binaries of native versus non-native English speakers. This runs the risk of fostering an ‘us versus them’ mentality (Roose Citation2001) whilst oversimplifying the multifaceted identities and cultural and linguistic experiences of individuals.

Ironically, some research into how to shift student teacher thinking about culturally and linguistically diverse school students also sees the student teachers in deficit. Researchers often frame their student teachers as primarily white, middle-class and English-speaking only, questioning their students ability to meaningfully interact with diverse cohorts because of a perceived lack of lived experience (Allard and Santoro Citation2006; Cruz and Patterson Citation2005; Ladson-Billings Citation2006; Sleeter Citation2001). It seems that it is not only policy makers but teacher educators themselves that unintentionally perpetuate deficit discourses. By using binary language speaker groups of monolingual/multilingual or native/non-native they risk positioning teachers and students across schools and teacher education courses as inherently in opposition to an abstract racialised ‘other’ (Fylkesnes Citation2018).

Teacher educators can be acutely aware of the powerful role that deficit language can play (Janfada Citation2023; Varga-Dobai Citation2018). As two bilingual teacher educators working in an ever increasingly diverse Australian tertiary sector (OECD Citation2019) we are sensitive to the biases underpinned by native/non-native discourse in the social space of teacher education. We work with staff and students who not only speak English as an additional language, but English speakers from current or former British colonies and ex-U.S. territories, as well as migrants who use ethnolectal or regionally influenced Englishes. This or that speak Aboriginal Englishes influences how we position ourselves and our students in the social space of the classroom because how any individual understands the world will be shaped by an enormous range of invisible socio-historically mediated experiences linked to English language use, language ownership, power and identity (Doecke and Mirhosseini Citation2023; Janfada Citation2023; Kirkpatrick Citation2021).

This can be seen in recent findings where the negative impact of native and non-native English speaker discourse is undermining student teachers’ confidence regarding their language abilities (Ahn Citation2018; Ahn, Ohki, and Slaughter Citation2023; D’warte, Rushton, and Abu Akbar Citation2021). However, it is still unclear in the literature how any individual’s complex and dynamic understanding of English might influence their capacity to teach inclusively.

We therefore seek to understand the experiences of four teacher educators at an Australian higher education institution after they implemented two inclusive classroom activities in a Master of Teaching (Secondary) subject on inclusivity. These activities aimed to begin to deconstruct the dichotomous labels of ‘native’ and ‘non-native’ English speakers, focusing instead on creating the conditions for students and staff to positively experience their own and their peers’ unique linguistic strengths and backgrounds.

Through semi-structured interviews data was collected relating to the teacher educators’ experiences of teaching the two tasks and their perceptions of how students experienced the same activities. The data was thematically analysed using Matsuo and Nagata’s (Citation2020) experiential learning checklist to interrogate the psychological and structural conditions underlying their experiences. We then applied Bourdieu’s (Citation1977) concepts of habitus and field theory to evaluate both individual and broader sociocultural factors that may have influenced staff and student experiences.

Shifting thinking in teacher education

Perceptions and motivations are deeply influenced by social and economic structures (Bourdieu Citation1977, Citation1979). These structures often subtly but powerfully shape the lens through which we interpret our world and interact with others. In the context of initial teacher education, a recurring challenge for us is the shadow cast by dominant societal norms and backgrounds that shape deficit discourse in relation to ‘non-native’ English speakers. We have observed that these dominant perspectives can, at times, inadvertently marginalise a range of English speakers, relegating them to a secondary status based on preconceived notions about language proficiency. This binary perception not only puts ‘non-native’ speakers in a difficult position but also puts ‘native’ English speakers under pressure. They are frequently held up as the ultimate authorities on the English language. Such unrealistic expectations can be taxing, especially when they’re assumed to have an answer to every linguistic query (Ahn Citation2020; Ahn and Delesclefs Citation2020). Ultimately, it is such binary language speaker discourse that can also potentially shape how we perceive ourselves and others.

Change in one’s attitudes and dispositions towards the self and others is ever evolving and transforming, however, through reflexive and fluid engagement with others in new social settings (Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992; Dépelteau Citation2008). Based on this premise, reflective practices and social justice frameworks have been widely considered useful in teacher education to begin to transform student teacher thinking about diverse school students in the hope that they will then teach inclusively.

Mills and Ballantyne (Citation2010) used reflective practices to shift student views on diversity, noting some growth from self-awareness to social justice. Interestingly, students regularly referred to race dichotomously, offering complex ideas of themselves and others in terms of ‘whiteness’. How this language use continued to perpetuate difference through class tasks was not considered, however. In a subsequent longitudinal study, Mills (Citation2013) assessed student teachers’ perspectives during their university time and early teaching years. Results indicated that as beginning teachers they still perceived themselves as different to their school students and that their course had not prepared them sufficiently to work with diverse students. Of note, three of the interviewed beginning teachers were identified as ‘not citizens’ and one spoke a ‘Language other than English’. However, how these particular students’ unique perspectives on ‘diversity’ shaped perceptions of their course and current school experiences was unclear.

Teacher educators reflecting on their own beliefs and practices is therefore important as highlighted in studies by Rowan et al. (Citation2021) and Lunn Brownlee et al. (Citation2022). Ryan et al. (Citation2019) teacher educators’ recognised the need for their students to reflect critically, to establish emotional connections combined with a social justice perspective, especially concerning race and ethnicity. However, although it was noted that how individuals construct knowledge changes overtime, the impact the cultural and linguistic backgrounds of the teacher educators themselves had on shaping their perspectives was also unclear.

On the other hand, Varga-Dobai’s Citation2018 work underscores the profound role of acknowledging links between language background and perceptions of difference. Her ‘cultural selfies’ approach encouraged her student teachers to reflect on the interplay between language and power in their lived experiences and how this would impact on their work in schools. This theme of linguistic reflection was also evident in Ahn et al (Citation2023) and D’warte et al. (Citation2021), where students often perceived their own unique use of English as in deficit despite being multilingual. Perhaps this begins to unveil why some multilingual student teachers continue to self-position as inadequate or different when going into school settings (Moloney and Giles Citation2015).

Although some argue those with lived experiences of diversity are more likely to teach inclusively (Hammersley Citation2005; Hannigan, Faas, and Darmody Citation2022) it becomes apparent that there exist challenges in how to teach a range of student teachers to confidently work with diverse school students. Many staff and students appear to position themselves and others in the social world based on binary ideas of language groups and language ownership. On the other hand, using staff and student teachers’ own unique understanding of language to stimulate alternative perspectives about how to work with diverse cohorts may offer some advantages (Cross, D’warte, and Slaughter Citation2022). Through a harnessing of both teacher educator and student teachers’ diverse ways of knowing and being, in and through English, has the potential to offer new ways to understand how to teach and embrace language diversity in education.

Methodology

In 2022, we conducted 40-minute, semi-structured interviews with four teacher educators who identified as:

Nur: Malaysian born and speaking English and Malay.

Abbey: Australian born and learning another language in her spare time.

Aarin: Bangladeshi born and speaking several languages.

Nicole: Australian born and has learned languages at school.

The interviews focused on the staff experiences of two activities integrated into a postgraduate inclusive literacy subject within an Australian teacher education context that comprised a diverse range of both international and local students. The tasks aimed to address students’ biases around the ‘native’ vs ‘non-native’ speaker discourse by not privileging any ‘native’ English speaker by promoting a positive view of everyone in the class as a uniquely individual English user.

The two tasks were as follows:

Lesson 1 - a languages learning timeline

The languages learning timeline activity seeks to allow students to explore conscious and subconscious language learning journeys from birth to the present, across different social contexts, and use them as a rich learning resource to share with their peers to understand classroom diversity. To unearth and foreground their language learning experiences, a preliminary lecture on the diversity of English speakers in Australia and internationally was provided. This served to debunk any understanding that there is one ‘standard’ variety of English used in Australia. The concept of a whole linguistic repertoire (Busch Citation2012) was also explained – the notion that we all draw on different language knowledge and cultural understandings concurrently when making meaning.

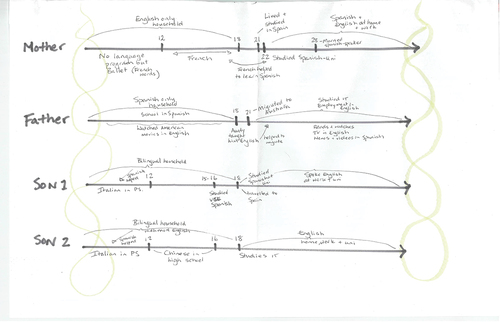

During the lecture a model featuring one Australian family () was presented. The family model showcased when and where each family member learned languages, the contexts in which language learning took place, and how both formal and informal language learning supported the unique acquisition of new languages for each family member.

The aim of presenting the family model was to:

visually represent the concept of ‘linguistic repertoires’ as individual and unique

support all students to create and celebrate their own diverse language learning journey across a range of activities and life events (Thomson Citation2002/2020)

Students were asked to create their own timeline based on the model and then share them in small groups to develop a ‘sociocultural awareness’ of the individual uniqueness of language learning (Doecke and Mirhosseini Citation2023, 78). They could refer to the type of English they used and how all languages, be they from hobbies, family or formal education, influenced their language learning at different stages in their lives. For example, learning ballet as a child supported learning French in high school or learning English was influenced by other languages. The whole class then reflected on what they had learned from each other and how this new knowledge might impact how they view or work with culturally and linguistically diverse school students.

Lesson 2 - a collaborative reading of word and images activity

The pre-tutorial lecture for this task emphasised the significant role words play in symbolising an individual’s comprehension of their surrounding world (Freire Citation1970); that words go beyond being arbitrary symbols and carry cultural and social meanings connected to distinct individual emotions, experiences, and societal knowledge.

In class, students were divided into small groups, and they collaboratively read word combinations aloud () explaining what each one meant to them. As a class, they then reflected on how they felt hearing the range of interpretations.

They then viewed four different images including an image of a cow in the countryside and repeated the process of sharing and reflecting on how they ‘read’ the image. They then reflected on the reading experiences to critically consider the implications for working with diverse cohorts.

The aims of these reading activities were to:

offer an open-ended experience where students appropriate English for their own purposes, without it being linked to a native/non-native speaker (Doecke and Mirhosseini Citation2023).

allow students to encounter alternative uses of the English language (Gibbons Citation2015; Halliday Citation1978), thus validating and appreciating their and their peers’ unique readings in English.

Analytical framework & data analysis

The staff interview data was disaggregated into:

their experiences of teaching the tasks

their perceptions of student experiences.

The data was then thematically analysed using Matsuo and Nagata’s (Citation2020) experiential learning framework, consisting of six areas for consideration:

Expected and unexpected events – Describing events that occurred during the teaching of the two tasks.

Management of emotions – Identifying emotions that arose from the tasks and whether these emotions were effectively managed. If not, examining how this may impact the learning process.

Reflective analysis – Reflecting on the expected and unexpected events to understand the strengths and weaknesses of the teaching approach. This involves challenging any assumed beliefs or biases about the benefits of the tasks.

Abstract conceptualisation – Extracting key ideas and considering possible causes and solutions to problems that arise. Alternative theories and strategies are also offered.

Unlearning – Consciously abandoning or modifying obsolete knowledge, values and associated methods or practices. This involves understanding the conditions and stages of learning experiences that may lead to change and abandoning or modifying approaches, as required.

Active experimentation – Planning, implementing, and reflecting upon new learning. This aspect focuses on whether opportunities are offered to apply new knowledge to facilitate a deep unlearning of attitudes or beliefs that may hinder transformative change.

Although Matsuo and Nagata’s (Citation2020) framework is drawn from experiential learning theory, we deemed it useful for critically analysing the tasks. This comes from the understanding within experiential learning that an unlearning of any entrenched attitudes or beliefs is crucial for acquiring new knowledge. In the context of our research, to analyse whether tasks that celebrate all language speakers’ differences can positively shift any negative attitudes one may hold towards the self and/or others in a multicultural classroom setting.

‘Validating’ and ‘valuable’

The aim of the timeline and reading activities was to challenge ‘native’ vs ‘non-native’ speaker discourse by celebrating everyone’s unique linguistic repertoire. Interviewees’ responses supported this as they felt that they and their students, regardless of their linguistic background, were deemed as ‘valuable’; that the experiences of sharing timelines was ‘validating’. As Abbey (Excerpt 1) notes, she believed her students positively engaged with the timeline task, to develop the understanding that:

Excerpt 1

… everyone’s experiences are valuable and important, and it does highlight the diversity of language learners and what it means to be a language learner … We’re all on a journey…(Abbey)

It can be inferred that by using ‘we’ she is indicating that she too felt that the task also allowed for her own unique linguistic background to be valued.

Aarin also agreed that the removal of the dichotomous ‘either/or’ discourse in both tasks to one of ‘a kind of a single repertoire in there’ supported students to actively begin to move away from any abstract, idea that a unified and singular English is separate or superior to knowledge and use of other languages or Englishes.

Nur felt her own legitimate voice was heard as a Malaysian speaker of English as she shared her own language story. She described how when she explained that she was fluent in English but still had to ‘take the IELTS, even though I actually teach English […]’ just so she could become a registered teacher in Australia her students then questioned ‘What is a native English language speaker?’ revealing how through the story telling of ‘unheard stories’ (Nur) some students were beginning to question the abstract ‘native’ English speaker construct that normally shapes ideas of difference.

Staff felt the reading of words and images in English also positively elevated multiple perspectives whilst shifting binary ideas of certain English language users as in deficit. For example, regarding the reading of the cow image, Abbey and Nicole explained how their students openly generated different interpretations such as a ‘barbecue’, a ‘sacred animal’ (Abbey and Nicole) or ‘animal cruelty’ (Nicole). These interpretations of the cow allowed for a range of ‘…interpretations…(that) may vary across …time, space’, (Aarin) to be experienced by peers as images in backyards, ships and countries were evoked.

Similarly, a range of interpretations emerged as observed by Aarin and Nicole when their students reflected on the reading of the indigenous Australian phrase ‘On Country’:

Excerpt 3

…one student, being of Malaysian descent said, if she went home and used this phrasing at home, nobody would be able to…associate it in the same way that we do… to her it stands out as very distinctly Australian (Nicole)

Excerpt 4

… a mature age student…he (had) no clue about the meaning of ‘Country’ from (an) indigenous perspective, like, you know, in Scotland…(Aarin)

As can be seen, from excerpts 3 and 4 two ‘native’ speakers’ experience of English diverged in interpretation based on their familiarity of a culturally mediated expression unique to Australia. Through the collaborative nature of the task the Malaysian student used her knowledge of English to reveal that words have both cultural and geographical boundaries, affirming her unique English language competency across borders. The Scottish student’s response reinforced the idea that even ‘native’ English speakers do not always have language knowledge, refuting notions that any ‘standard’ exists or has primacy. Knowledge was not related to being ‘native’ but to one’s experience of the English language.

‘It’s not easy’ for some; ‘it’s ok’ for others

A degree of discomfort was anticipated as a natural part of learning as one begins to reconsider any abstract ideas of there being a singular competent ‘native’ English speaker. Nevertheless, staff reported that some students openly struggled during tasks designed to be inclusive. For example, Aarin described how one student was participating in tasks but was frequently saying ‘You know it’s, it’s not that easy’. Aarin inferred, based on her own lived experiences, that ‘many second language speakers … they are sometimes unaware of their own linguistic identity because of the pressure of the dominant language…’. To justify this claim, she admitted that ‘Once upon a time’ she too ‘was kind of like that’ because in her family English was used as a sign of status. How Aarin understood the tasks and her student’s struggles was directly shaped by her lived experiences of the devaluing of other languages in the face of some elevated form of English.

Abbey also noted difficult feelings arose for some students with regards to the timeline task specifically. She noted her students seemed to show ‘some resistance’ and ‘vulnerability’. Although this indicates that the task required a further explicit process of reflective analysis to ask students why they might feel uncomfortable, thanks to staff expertise, a management of emotions was enacted so as not to stifle the learning process for students (Matsuo and Nagata Citation2020). For example, both Abbey and Nicole recounted how they shared their own timelines to support their students’ learning. Unexpectedly though, Nicole explained that it was so that her Anglo-Australian students would no longer see themselves as an ‘outsider’ … ‘compared to the ones that already spoke multiple languages … ’. She perceived that to overcome this negative belief they needed to understand that they were ‘the same’ as her as shown in excerpt 5:

Excerpt 5

…Yeah, I did mention, I said, you know, for example, you know I come from a very monolingual background, and mentioned that, you know, my, the extent of language learning in my family was really learning it at school. And then some of them sort of like, went, ‘okay, I’m the same, you know, that’s okay’. (Nicole)

In Excerpt 5 Nicole suggests that a mirroring of similar experiences was needed to support the necessary abstract positioning of staff and students in positive, new ways, that did not rely on labels of deficit as ‘monolinguals’. This suggests an extension of the task may be required to allow students to self-identify in certain ways to explain to each other the ‘root cause’ for what makes them feel discomfort when being exposed to multiple perspectives (Matsuo and Nagata Citation2020).

The root cause for Nicole’s perceptions of her students’ experiences of the timeline task was revealed in her reflecting on how, before the timeline task, she had felt ‘like a fraud’ when working with her linguistically diverse school students, as shown in excerpts 6 and 7.

Excerpt 6

… I felt like I haven’t maybe had the experience, that, that they’ve been learning multiple languages. And when I’m trying to explain something, and […] I’m trying to make sure I can explain it in multiple ways … it is hard thinking I don’t have, you know, all of these different ways to say and explain things. (Nicole)

However, her deficit feelings had changed after the teaching and sharing of her timeline as shown in excerpt 7.

Excerpt 7

I don’t feel as much as, kind of a fraud [.] … I don’t kind of feel like … I’ve only got this one language […] and I’m … trying to kind of, you know, make it work. Now, I can see multiple different ways. (Nicole)

Excerpts 6 and 7 suggest that in the past she experienced feelings of inadequacy or being unqualified to teach multilingual students as a ‘monolingual’ teacher. However, through the concrete experience of sharing her story in class, where she acknowledged that she has learnt English and other languages, she now felt more equipped.

An important step in beginning to unlearn her deficit beliefs was to draw relevant and transferable conclusions in the interview as to the root causes of what impeded her from teaching inclusively in the past (Matsuo and Nagata Citation2020). This indicates that the tasks themselves alone were not facilitating such critical thinking.

In our analysis of the data, transferable conclusions as to why someone will not teach inclusively could not be causally linked to a ‘monolingual’ label. Abbey, although also ‘Anglo-Australian’, did not possess a similar deficit self-perception because, as she said, she already had knowledge of ‘different Englishes’. This was due to her learning another language and being married to a migrant. She further elaborated by noting that prior to the timeline task she already knew that a ‘merging’ of language occurred naturally which is why she ‘quite explicitly think(s) about the fact that’ she is learning ‘different Englishes’. She added that such knowledge ‘helps to inform (her) thinking’. This suggests that the timeline task simply affirmed, not shifted, dispositions towards herself and others because her unique life experiences already supported her to value linguistic diversity more broadly.

Deeper shifts – multiple contexts and further reflection

A valuing of linguistic diversity through two short tasks does not necessarily translate into inclusive teacher practice. Unexpectedly, however, three of the four teachers interviewed acknowledged that through the teaching of the reading activities they had now positively modified their own pedagogical approaches even though the tasks were designed for students. For example, in excerpt 8 Nicole explained how she now spends more time exploring various relevant concepts and key terms to support meaning when teaching The Crucible:

Excerpt 8

‘ … when looking at the idea of a “witch hunt”, (we) spent quite a lot of time in, on… What does this mean? What do you think of when you hear this word? And looking at … how different cultures perceive it, how it’s perceived over time, and really getting an understanding of that language rather than just kind of me, giving the definition, talking about it, saying it can be said in a number of different ways, and then moving on’ (Nicole).

Additionally, as seen in excerpt 9 Abbey now engages in a deeper analysis of images as seen in her description of a lesson from her Year 7 English class:

Excerpt 9

‘We ended up doing a whole lesson where we just talked about “What is symbolism?”, and “What is colour symbolism?” and “How is it rooted in different cultural understandings”[…] Just trying to check my own assumptions about things like multimodality, and how images will actually be interpreted, if they’ll be helpful, or if they’ll be actually problematic, or will it make understanding meaning more difficult’.

Both participants revealed that through the concrete experience of listening to their diverse student teachers’ reading the words and images they have now changed their teaching approaches. They also now possess an enhanced, critical understanding of the limitations of simplistic word definitions and multimodality as a simple solution to teach inclusively. These observations suggest that the reading tasks have the potential to initiate a process of deeper unlearning if combined with further contexts in which to actively experiment and then reflect upon.

Discussion

We understand that profound unlearning of any deficit beliefs that impede inclusive teaching practice cannot be achieved solely through two short activities. To begin to shift understandings about what constitutes a diverse language learner, adequate and frequent social conditions that offer multiple perspectives and reflection are needed. Only then can the underlying structures that shape certain beliefs or attitudes be understood and then challenged (Pöllmann Citation2016). Nevertheless, through the implementation of these purposefully designed activities, teaching staff felt more valued and together with their students, they began to challenge longstanding binary discourses around English speakers; discourses that often essentialise the complexities of linguistic differences.

Open-ended tasks, particularly those centred around the common practice of reading, appear to prompt a shift in how diversity is perceived. For example, in the cow reading activity diverse interpretations emerged as Abbey and Nicole observed. Varied perceptions of the cow arose from festivity to spiritual connections and ethical sentiments. The range of responses to the phrase ‘On Country’ also further emphasised this diversity and deconstructed the notion of one singular, ‘native’ experience of English. Nicole observed her Malaysian student’s versatile use of English across cultures, while Aarin underscored a Scottish student’s need for specific language knowledge, even as a ‘native’ speaker, to be able to complete the task. This activity therefore debunking the misconception that proficiency is limited to a ‘Standard’ English form.

The two activities, as interpreted by teachers, revealed to us the role experience, not language speaker background, plays in making meaning in English. In this way, English moved away from being attached to rules, standards or proficiencies – factors that affirm difference. Instead, the tasks allowed for English to serve as a ‘translingual’ tool (Horner et al. Citation2011), to emphasise the fluid and dynamic ways with which all English speakers interact with English in an English medium classroom. However, not all interventions elicited positive responses. For instance, one English as an Additional Language learner found the tasks challenging. This may be attributed to a mismatch between her prior self-perception (as an English language learner in deficit) in the face of the new social positioning offered by the strengths-based approach of the activities (Bourdieu Citation1979). Alternatively, the challenges may have stemmed from an attempt to navigate multiple linguistic and ontological frameworks simultaneously (Dryden, Tankosić, and Dovchin Citation2021) around Australian educational concepts of inclusion while learning in English.

Both of the activities required for reflective mechanisms to be embedded to allow more of the unconscious to be made conscious (Akram Citation2013) as occurred in the interviews for Aarin and Abbey who disclosed childhood experiences and feelings of inadequacy as influencing how they understand themselves and others. However, it was also the absence of student voice in the research project that impeded us from developing further understandings of what was occurring for some individuals.

What was apparent though was that relationality was crucial in understanding how the classroom activities could potentially mould or shift attitudes in the future. While some participants naturally adopted strengths-based perspectives through collaborative language usage, others needed a shared ‘trans-action’ (Dépelteau Citation2008), rooted in their self-identity as language speakers. For example, Nicole and certain students needed mutual self-identification, highlighting how shared language-learning experiences may support a move past any deficit beliefs about language knowledge. Conversely, Abbey, was already exposed to varied language use due to her own unique social trajectory (Carrington and Luke Citation1997). She therefore did not need self-identification as her existing positive dispositions toward linguistic diversity already equipped her with the capital needed to meet the inclusive objectives.. This difference underscores the necessity for us all as researchers in initial teacher education to examine the interplay between habitus and capital in the social context (Edgerton and Roberts Citation2014), particularly between individual attitudes towards diversity and self-perceived linguistic capital, both within and outside of English. Understanding this interplay may then provide deeper comprehension about why some teachers and students are more open to adopting inclusive teaching approaches and embracing nuanced understandings of cultural and linguistic diversity.

Conclusions

Through this work, we highlight the effectiveness of using strengths-based multimodal tasks to engage in challenging negative social positionings underpinned by binary language speaker groups. By foregrounding marginalised voices and often hidden linguistic and cultural relationships with English, English served as a learning tool to celebrate staff and students’ unique linguistic and cultural profiles (Ollerhead Citation2018). The influential role of personal experiences as social narratives positively shaped perceptions of cultural and linguistic diversity through a non-hierarchical linguistic space.

Embracing an interdisciplinary methodological approach supported us to reveal and interpret complex emotional responses and perceptions generated by individuals in the social world (Bourdieu Citation1977; Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992; Matsuo and Nagata Citation2020). Through this approach we came to understand the limitations in teacher education of labelling individuals as coming from narrow English language speaker groups to comprehend how one interprets tasks designed to become more inclusive.

By advocating for practices that harness culturally and linguistically rich language use we reveal how staff and students manifested distinctive responses that could not be conveniently categorised into either a ‘monolingual’ or ‘multilingual’ group, reinforcing the need for us all to challenge dominant tertiary educational narratives and literacy practices (Albright and Luke Citation2008; Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992) that often perpetuate an oversimplified, binary correlation between race, language speaker and negative attitudes, dispositions and beliefs. Binary language speaker labels fail to account for the socially complex nature with which each individual relates and connects through language use. The individual paths of each participant in our research challenged prevailing norms and addressing these issues is therefore crucial for promoting inclusive practices in teacher education.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

April Edwards

April Edwards is a Lecturer in the Language and Literacies Academic Group in the Faculty of Education, The University of Melbourne, Australia. Her research focuses on culturally sustaining pedagogies that seek to holistically include all learners in the teaching and learning processes. She is also interested in the philosophy of experience and the role simulated literacy activities can play to evoke new, more pluralistic understandings of the self.

Hyejeong Ahn

Hyejeong Ahn is a Senior Lecturer in the Language and Literacies Academic Group in the Faculty of Education, The University of Melbourne, Australia. Her research draws on the evidence-based approach, documenting and evaluating the fast-changing literacy skills required for literacy leaders and teachers to help their students to participate in international affairs actively and meaningfully in the global context.

References

- Ahn, H. 2018. ‘Help me’: The English Language and a Voice from a Korean Australian Living in Singapore.” In Questions of Culture in Autoethnography, edited by P. Stanley and G. Vass, 13–22. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315178738-2.

- Ahn, H. 2020. “Where are You Really From?” In Critical Autoethnography and Intercultural Learning, edited by P. Stanley, 76–83. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429280016-8.

- Ahn, H., and D. Delesclefs. 2020. “Insecurities, Imposter Syndrome, and Native-Speakeritis.” In Critical Autoethnography and Intercultural Learning, edited by P. Stanley, 95–99. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429280016-10.

- Ahn, H., S. Ohki, and Y. Slaughter. 2023. “Ownership of English: Insights from Australian Tertiary Education.” Changing English 30 (3): 263–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/1358684x.2023.2212365.

- Akram, S. 2013. “Fully Unconscious and Prone to Habit: The Characteristics of Agency in the Structure and Agency Dialectic.” Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 43 (1): 45–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/jtsb.12002.

- Albright, J., and A. Luke, eds. 2008. Pierre Bourdieu and Literacy Education. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203937501-10.

- Allard, A. C., and N. Santoro. 2006. “Troubling Identities: Teacher Education Students’ Constructions of Class and Ethnicity.” Cambridge Journal of Education 36 (1): 115–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057640500491021.

- Bourdieu, P. 1977. “The Economics of Linguistic Exchanges.” Social Science Information 16 (6): 645–668. https://doi.org/10.1177/053901847701600601.

- Bourdieu, P. 1979. Algeria 1960: The Disenchantment of the World, the Sense of Honour, the Kabyle House or the World Reversed. New York: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/1960704.

- Bourdieu, P., and L. J. D. Wacquant. 1992. An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.1086/ahr/99.5.1644.

- Busch, B. 2012. “The Linguistic Repertoire Revisited.” Applied Linguistics 33 (5): 503–523. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/ams056.

- Carrington, V., and A. Luke. 1997. “Literacy and Bourdieu’s Sociological Theory: A Reframing.” Language and Education 11:96–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500789708666721.

- Cross, R., J. D’warte, and Y. Slaughter. 2022. “Plurilingualism and Language and Literacy Education.” Australian Journal of Language & Literacy 45 (3): 341–357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44020-022-00023-1.

- Cruz, B. C., and J. Patterson. 2005. “Cross-Cultural Simulations in Teacher Education: Developing Empathy and Understanding.” Multicultural Perspectives 7 (2): 40–47. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327892mcp0702_7.

- D’warte, J., K. Rushton, and A. Abu Akbar. 2021. Investigating Pre-Service Teachers’ Linguistic Funds of Knowledge. Centre for Education Research, Western Sydney University https://researchdirect.westernsydney.edu.au/islandora/object/uws:60711.

- Dépelteau, F. 2008. “Relational Thinking: A Critique of Co-Deterministic Theories of Structure and Agency.” Sociological Theory 26 (1): 51–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9558.2008.00318.x.

- Doecke, B., and S. Mirhosseini. 2023. “Multiple Englishes: Multiple Ways of Being in the World.” English in Education 57 (2): 76–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/04250494.2023.2189910.

- Dryden, S., A. Tankosić, and S. Dovchin. 2021. “Foreign Language Anxiety and Translanguaging as an Emotional Safe Space: Migrant English as a Foreign Language Learners in Australia.” System 101:102593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2021.102593.

- Edgerton, J. D., and L. W. Roberts 2014. “Cultural Capital or Habitus? Bourdieu and Beyond in the Explanation of Enduring Educational Inequality.” Theory & Research in Education 12 (2): 193–220. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477878514530231.

- Freire, P. 1970. “The Adult Literacy Process as Cultural Action for Freedom.” Harvard Educational Review 40 (2): 205–225. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.40.2.q7n227021n148p26.

- Fylkesnes, S. 2018. “Whiteness in Teacher Education Research Discourses: A Review of the Use and Meaning-Making of the Term Cultural Diversity.” Teaching & Teacher Education 71:24–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.12.005.

- Gibbons, P. 2015. Scaffolding Language, Scaffolding Learning: Teaching English Language Learners in the Mainstream Classroom. 2nd ed. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

- Halliday, M. A. K. 1978. Language as Social Semiotic: The Social Interpretation of Language and Meaning. London: Edward Arnold.

- Hammersley, M. 2005. “The Myth of Research‐Based Practice: The Critical Case of Educational Inquiry.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8 (4): 317–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557042000232844.

- Hannigan, A., D. Faas, and M. Darmody. 2022. “Ethno-Cultural Diversity in Initial Teacher Education Courses: The Case of Ireland.” Irish Educational Studies 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2022.2061559.

- Horner, B., M.-Z. Lu, J. J. Royster, and J. Trimbur. 2011. “Language Difference in Writing: Toward a Translingual Approach.” College English 73 (3): 303–321. https://doi.org/10.7330/9781607326205.c005.

- Janfada, M. 2023. “Dialogic Appropriation in Academic English Literacy and Pedagogy: Transnational and Translingual Praxis.” Changing English 30 (3): 195–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/1358684x.2023.2210831.

- Kirkpatrick, A. 2021. “Teaching (About) World Englishes and English as a Lingua Franca.” In Research Developments in World Englishes, edited by A. Onysko, 251–270. London: Bloomsbury Academic. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350167087.ch-012.

- Ladson-Billings, G. 2006. “It’s Not the Culture of Poverty, It’s the Poverty of Culture: The Problem with Teacher Education.” Anthropology & Education Quarterly 37 (2): 104–109. https://doi.org/10.1525/aeq.2006.37.2.104.

- Lunn Brownlee, J., T. Bourke, P. Churchward, S. L. E. L. Walker, L. Rowan, M. Ryan, A. Berge, and E. Johansson. 2022. “How Epistemic Reflexivity Enables Teacher educators’ Teaching for Diversity: Exploring a Pedagogical Framework for Critical Thinking.” British Educational Research Journal 48 (4): 684–703. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3789.

- Matsuo, M., and M. Nagata. 2020. “A Revised Model of Experiential Learning with a Debriefing Checklist.” International Journal of Training and Development 24 (2): 144–153. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijtd.12177.

- Matsuo, M., and M. Nagata 2020. “A Revised Model of Experiential Learning with a Debriefing Checklist.” International Journal of Training and Development 24 (2): 144–153. http://doi.org/10.1111/ijtd.12177.

- Mills, C. 2013. “Developing Pedagogies in Pre-Service Teachers to Cater for Diversity: Challenges and Ways Forward in Initial Teacher Education.” International Journal of Pedagogies and Learning 8 (3): 219–228. https://doi.org/10.5172/ijpl.2013.8.3.219.

- Mills, C., and J. Ballantyne. 2010. “Pre-Service Teachers’ Dispositions Towards Diversity: Arguing for a Developmental Hierarchy of Change.” Teaching & Teacher Education 26 (3): 447–454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2009.05.012.

- Moloney, R., and A. Giles. 2015. “Plurilingual Pre-Service Teachers in a Multicultural Society: Insightful, Invaluable, Invisible.” Australian Review of Applied Linguistics 38 (3): 123. https://doi.org/10.1075/aral.38.3.03mol.

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development). 2019. Education at a Glance 2019: OECD Indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing. www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/education-at-a-glance-2019_f8d7880d-en.

- Ollerhead, S. 2018. “Pedagogical Language Knowledge: Preparing Australian Pre-Service Teachers to Support English Language Learners.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education 46 (3): 256. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866x.2016.1246651.

- Pöllmann, A. 2016. “Habitus, Reflexivity, and the Realization of Intercultural Capital: The (Unfulfilled) Potential of Intercultural Education.” Cogent Social Sciences 2 (1): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2016.1149915.

- Roose, D. 2001. “White Teachers’ Learning About Diversity and ‘Otherness’: The Effects of Undergraduate International Education Internships on Subsequent Teaching Practices.” Equity & Excellence in Education 34 (1): 43–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/1066568010340106.

- Rowan, L., T. Bourke, L. L’Estrange, J. Lunn Brownlee, M. Ryan, S. Walker, and P. Churchward. 2021. “How Does Initial Teacher Education Research Frame the Challenge of Preparing Future Teachers for Student Diversity in Schools? A Systematic Review of Literature.” Review of Educational Research 91 (1): 112–158. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654320979171.

- Ryan, M., T. Bourke, J. Lunn Brownlee, L. Rowan, S. Walker, and P. Churchward. 2019. “Seeking a Reflexive Space for Teaching to and About Diversity: Emergent Properties of Enablement and Constraint for Teacher Educators.” Teachers & Teaching 25 (2): 259–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2018.1542298.

- Sleeter, C. E. 2001. “Preparing Teachers for Culturally Diverse Schools: Research and the Overwhelming Presence of Whiteness.” Journal of Teacher Education 52 (2): 94–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487101052002002.

- Thomson, P. 2002/2020. Schooling the Rustbelt Kids: Making the Difference in Changing Times. Crows Nest, NSW: Allen & Unwin. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003117216.

- Varga-Dobai, K. 2018. “Remixing Selfies: Arts-Based Explorations of Funds of Knowledge, Meaning-Making, and Intercultural Learning in Literacy.” International Journal of Multicultural Education 20 (2): 117–132. https://doi.org/10.18251/ijme.v20i2.1572.