ABSTRACT

Transnational routes such as direct-entry have become a more attractive option for Chinese students, due to the pandemic-imposed travel restrictions in China. The rise of Chinese direct-entry students can potentially lead to a significant increase in demand for academic and non-academic support not only after their arrival, but also before their departure from China. By applying Schlossberg’s transition theory, this paper seeks to develop a good understanding of the academic and social belonging of Chinese direct-entry students in the UK through re-analysing the portraits (written narratives) of a previous research project. The findings indicate that these students were feeling disconnected from the academic and social communities. The factors affecting their sense of belonging are described using the 4S framework, namely self, strategies, situation and support. The paper ends with recommendations to key university stakeholders on how the partner institutions in China and the UK can help enhance a sense of academic and social belongingness of Chinese direct-entry students.

Introduction and background

The UK has consistently been one of the top destinations for Chinese international students (Cebolla-Boado, Hu, and Soysal Citation2018). With regard to an undergraduate programme, Chinese students have the option to either study the entire degree in the UK (e.g. the duration is three-year) or join directly onto an existing cohort in the second or the final year (e.g. the duration is two- or one-year). The latter option is termed as a direct entry route. When choosing this route, Chinese students tend to stay in the UK for a much shorter duration and be able to enjoy a study abroad experience at a much lower cost (Li and Zhang Citation2022). In the post-pandemic era, this study-abroad option is anticipated to become more favourable to Chinese students, because of the sustained influence of the Covid-19 pandemic and the concern over cost of study.

A recent survey conducted by Navitas Insights (Citation2023) shows that the sustained Covid impact is one of the key factors to consider for Chinese students when choosing their study abroad destination and option. Neighbouring countries such as Japan and Singapore are becoming more attractive for those opting for a long-term study abroad. This is because due to a combination of Covid imposed travel restrictions in China, such as tougher border control, flight unpredictability and periodic lockdowns, many Chinese students consider it less troublesome to travel between China and its nearby destinations compared with long-haul international flights if they plan to come back home regularly.

The survey also suggests that the living cost and tuition fees are another important factor for Chinese students, since the Chinese economy took a significant hit from the Covid-pandemic. For example, the rate of Chinese economic growth in 2020 exhibited a low level of 2.2% – the weakest growth since 1976, even though it rebounded to 4.3% in 2022 (World Bank Citation2023; Liang and Hoskins Citation2022).

In spite of its perceived popularity, the transition of Chinese direct-entry students into and through the UK system is recognised as a stressful and demanding process, because of the special features of direct entry routes, and also because of the newly emerging challenges in the post pandemic era. For instance, the study duration via this route is short. Students are expected to settle in and catch up on academic work quickly when joining an existing group of students. In addition, as with other university students globally, Chinese students are experiencing a reverse transition, that is, moving from online to face-to-face learning, and readjusting to campus life (Zhao and Xue Citation2023). The current change in English language teaching policy in China also has an impact on their English language proficiency. These challenges may prevent Chinese direct entry students from connecting with home students and integrating into the local communities. This feeling of being left out is likely to affect their overall satisfaction with studying in the UK, as well as their academic performance (Quan, Smailes, and Fraser Citation2013; Hewish et al. Citation2014; O’Dea Citation2021).

There have been numerous research articles on international students’ sense of belonging, particularly their social belonging, that is, their social relationships and interactions with home students and other international student groups (Chen and Zhou Citation2019). However, less attention has been paid to understanding the academic and social belonging of Chinese direct entry students in the post-pandemic context, in particular, when they are facing a new set of competitive challenges. Fostering a sense of belonging in a very short period of time can be more challenging for Chinese direct-entry students, compared with those studying an entire first degree abroad, as the latter is given much longer time to adjust to the new learning and social environment. Besides, Chinese direct entry students have to join an existing group of students who often already have their close group of friends. In contrast, other international students tend to begin at the same starting line. This makes it easier for them to make friends with each other (Rohrer, Keller, and Elwert Citation2021).

This paper therefore aims to bridge the gap. Using Schlossberg’s adult transition theory as a theoretical foundation, the paper explores the personal experiences of a group of Chinese direct entry students in the UK and seeks to answer the following questions:

What are the perceived views of Chinese direct entry students in the UK on their academic and social belonging?

What are the key factors affecting sense of belonging among this group of students?

This group of students studied the UK between 2015 and 2016 via an articulation agreement between their home and host institutions. When they arrived in the UK, they joined directly onto a final year programme in the Business School at a post-92 university. Before coming to the UK, they studied in different Chinese institutions and gained either a Scottish Qualifications Authority Higher National Diploma (SQA HND) or an equivalent diploma in China.

As discussed above, the current situation in the post pandemic era is likely to exacerbate the issues raised relating to Chinese direct entry students. By re-analysing the data, it is hoped that the findings will help and support both parties, that is, students themselves and the partner institutions in both countries better contribute to the enhancement of Chinese direct entry students’ sense of belonging in the new era.

Post-pandemic challenges

In the post pandemic era, Chinese students face two new challenges: the reverse transition and the change in English language teaching policy in China.

Globally university students are experiencing a reverse transition (Zhao and Xue Citation2023), that is, a transformation from online to face-to-face learning. Through the pandemic, universities had to move teaching wholly online as a result of the lockdown. The associated difficulties and challenges students encountered are well documented. For example, they needed to adjust to the remote learning environment and learn to use new online platforms as quickly as possible. Many students were severely affected by campus closure and a lack of interactions with their peers and their tutors (Barrot, Llenares, and Del Rosario Citation2021). Following a span of two years (2020–2022) when online learning almost became the new normal for students, Covid restrictions in the UK have been lifted gradually, and the Department of Education urged universities to go back to face-to-face teaching (Gov.uk Citation2022). In this situation, helping students re-adjust to campus life and rebuild their sense of belonging is high on the agenda for universities during the post-pandemic era (Tang and He Citation2023).

Language proficiency plays a critical role for direct entry routes due to the compressed nature of direct entry programmes. It has been reported that there are some major changes relating to English teaching in China, which potentially may affect the English language competence of Chinese students. For instance, a new regulation issued by the Ministry of Education in 2020 forbids primary and secondary public schools in China to use foreign textbooks (Ministry of Education Citation2019). Shanghai as a pilot city has started trialling to remove English from primary school end of term exams since 2020 (Shanghai Municipal Education Commission Citation2021). In addition, a member of China People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) has suggested eliminating English from the current compulsory education (primary and secondary schools) and the Gaokao. He believes that Chinese students spend too much time studying English, which has proven to be only beneficial to a small number of Chinese university graduates (10%) in the Chinese labour market.

Direct-entry route to the UK

Direct-entry is a type of study abroad route in the UK, and is associated with an articulation agreement. Depending on the individual agreements between Chinese and UK institutions, articulation agreements enable Chinese students to study at a home institution first for two or three years, and then entry directly onto an existing undergraduate programme in the UK partner institution for an additional one (final year) or two years (from year two). Once they complete their studies successfully, they will obtain a UK bachelor’s degree (Saville and Hewish Citation2015). Consequently, Chinese students coming to the UK via a direct-entry route are referred to as Chinese direct-entry students. This paper is concerned with the final year direct-entry Chinese students only.

In the UK, Chinese direct-entry students have been particularly significant, because of the strong and increased collaborative partnerships between the two countries (Johnson et al. Citation2021). Data from the Higher Education Association (HEA) show that in 2018–2019, 16% of international students in the UK were direct-entry students and over half of them were from China (8665). This accounts for 38% of the Chinese undergraduate students coming to the UK in that year (Saville and Hewish Citation2015).

Chinese direct-entry students are forecast to rise notably in the post-pandemic era. This is because China has only just reopened its border after three years of Covid restrictions. These restrictions indeed made it difficult for Chinese students to come to the UK since China stopped issuing and renewing passports for non-essential travel in the past three years.

Cross-border transition and a sense of belonging

A smooth transition is very important for the academic and social success of international students and is closely interconnected with their sense of belonging. Research shows that those who experience an unpleasant and unsuccessful transition experience often feel that they lack a sense of belonging. On the other hand, students who do not feel that they are part of the university communities tend to have a more stressful transition experience (Chen and Zhou Citation2019). Nevertheless, feeling part of a community has been shown to have a positive impact on students’ motivation and psychological wellbeing.

Sense of belonging includes both academic and social aspects and is largely concerned with the degree to which they feel that they are valued, cared, supported and accepted as a member in their academic and social communities (Lewis et al. Citation2016). In the context of international students, research on social belonging appears to emphasise social connectedness of these students with different groups within the university, such as home students, other international students, academic and support staff (Chen and Zhou Citation2019). Academic belonging however focuses on students’ connection to their subject discipline, and professional communities, including their peers on the same programme and their tutors. The identified main barriers to international students’ belonging at both the social and academic aspects include poor English proficiency, different culture and custom and the differences between the host and home countries in terms of the education systems, including learning and teaching approaches, and the host university and faculty support (Slaten et al. Citation2016).

Creating a sense of belonging is particularly important for international students in the post-pandemic era. This is in part because many of them suffered from social isolation, depression and anxiety during the emergency remote teaching taking place in the Covid-pandemic period (Gopalan, Linden-Carmichael, and Lanza Citation2022). In addition, even though higher education institutions in the UK by and large have returned to face-to-face teaching, many opt to deliver large lectures (e.g. with over 100 students) and personal tutorial meetings online. This can potentially have a significant impact on the sense of belonging of international students, in particular direct-entry students.

Schlossberg’s transition theory

Schlossberg’s transition theory (Citation1984, Citation2011) is an adult development theory. It has been adopted regularly to explore transition experiences of university students (DeVilbiss Citation2014; Monaghan Citation2022). To manage their transitions successfully, Schlossberg suggests individuals to take all perspectives and possibilities into account and view any transition they experience, including cross-border transition as a unique and positive life-changing opportunity to develop, to grow and to explore options for dealing with various changes they may encounter.

Schlossberg’s theory is developed specifically for helpers, such as counsellors, education practitioners and psychologists to assist individuals, including adolescents and young adults, to go through their transitions smoothly. She advocates that helpers should have a clear idea of the key factors that influence one’s transition, including self, strategies, situation and support. These factors are termed as the 4S factors. Self and strategies are considered as personal level factors, whilst situation and support are considered as institutional level factors. For example, self describes the characteristics of individuals, such as their age, gender, cultural background and socioeconomic status. Strategies are methods or solutions individuals use to handle a transition. Situation is concerned with the context of a transition, such as the trigger of the transition, the nature, and the duration of the transition, and whether the individual has previous experience in a similar type of transition. Support refers to the support that individuals seek when going through a transition. External help may come from their personal social network, such as family, friends and peers or from local communities and universities where they study.

Methods

Data collection

The methodological framework adopted in this study was portrait methodology. Data were collected from a group of 12 Chinese students studying a one-year direct-entry business programme in a single post 92 institution in England between 2015 and 2016. Portrait methodology is a type of narrative methodology. It enables the researcher to represent the personal stories told by the participants through his or her own interpretations (Bottery et al. Citation2009; O’Dea Citation2021). These interpretations are named as portraits and are essentially written narratives. Since the portrait methodology emphasises personal perceptions, it uses only semi-structured interviews to collect data (Bottery et al. Citation2009).

Data collection started almost immediately after these students arrived in the UK and continued across the one-year duration through repeated one-to-one semi-structured interviews at the three key transition stages, namely moving in (the pre-departure and post arrival period), moving through (the first semester) and moving out (the end of the second semester) stages. The interview questions were designed to explore the personal experiences of the participants in depth, including the contextual factors at the personal and institutional level. At the moving-in stage the focus was on their background and learning experience in their Chinese institution. At the moving through and moving out stages, the emphasis was on their academic and social experiences in the first or second semester. A selection of principal questions is listed below. In order to create a relaxing environment for the participants, and to enable them to express their thoughts and opinions comfortably and accurately, interviews were conducted in Chinese. Permission was asked and granted each time for audio recording the interview. In total, 36 interviews were conducted (e.g. 3 interviews for each participant) and each lasted approx. 90 min ().

Table 1. A selection of principal interview questions.

Portraits were produced at each transition stage for all participants upon the interview transcripts, and the writing took place alongside the first coding process. In total, 36 portraits were produced (e.g. 12 portraits at each transition stage), and each was approx. 3500 words. Since it is impractical to include an entire portrait with this article, a small extract of two portraits is provided (). Once all 36 portraits were produced, they were analysed in conjunction with the interview transcripts during the second coding process.

Hotspots analysis

The data collected were then analysed using hotspots analysis. This approach was chosen because it is designed for assimilating large datasets and clustering data around hotspots, the most important data or areas that need to be prioritised (Barthel et al. Citation2015). Even though the sample size of the study was small (12), the size of the dataset was large. It included 36 interview transcripts (approx. 2000–2500 words each), and 36 portraits (approx. 126,000 words altogether).

The hotspots analysis was carried out through the following steps: (1) goal definition; (2) data familiarisation and analysis; and (3) hotspots identification (Barthel et al. Citation2015). The first step is concerned with what the hotspots analysis intends to achieve. As discussed above, this paper aims to explore the perceived views of Chinese direct entry students with regard to their academic and social belonging, and also the factors affecting sense of belonging among this group of students, so that university key stakeholders can plan and take actions accordingly to better facilitate and support Chinese and potentially other direct-entry students transition to and through the UK.

The second step focuses on developing a deep understanding of the data collected. During this process, the author familiarised myself with ‘the depth and breadth’ of the data (Nowell et al. Citation2017, 5). This included all interview transcripts and portraits. I then highlighted the key and important areas that had emerged and categorised them based on similarities. Particular attention was paid to the feelings and opinions of the students towards sense of belonging, and also the impact of the contextual factors at the personal and institutional level on their personal experience in this year.

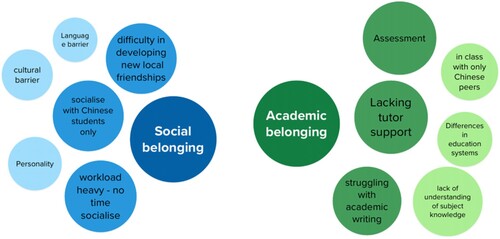

The third and the most important step involves identifying the hotspots and clustering the data around these hotspots. There were two sets of hotspots as the paper addresses two research questions. The first set was revolving around their perceptions towards sense of belonging, and the hotspots included academic and social belonging. The second set identified the factors affecting their sense of belonging. Because this paper adopts Schlossberg’s transition theory as the theoretical foundation, the 4 S factors were used as the hotspots for the second set, including self, strategies, situation and support. Consequently, the categories identified at the previous step were then clustered around these hotspots. An illustration of the first set of the hotspots is provided below (.).

Findings

Feeling disconnected from the social and academic communities

Social belonging refers to the social connections and interactions of individuals with other members of the community. Academic belonging refers to students’ connections with the programme they study, the subject discipline and their professional communities. The participants by and large indicated that they did not feel they belonged at the UK university because they did not manage to fit in with the academic and social communities around them. As a result, they reported that they were unable to truly enjoy their study abroad experience. For example, throughout the year, this group of Chinese students seemed to socialise predominately with their compatriots, and had trouble developing new friendships with home students, and other international students. Some of them (5 out of 12) commented specifically on their perceived feeling of being an outsider.

This one-year study abroad feels more like a trip, a lonely holiday to me. I feel like a total stranger … I don’t belong here … I can’t see the end of this journey … I don’t go out much … I am tied to my room all the time.

I feel that I am just a tourist in this country. I use this year to travel around and have seen different places. But that is about it … . I don’t interact with people, I don’t know any locals.

Data suggest the situation the participants were in was very different from what they had expected. The majority of them (11 out of 12) had a positive attitude and were looking forward to becoming part of local communities when they initially arrived. However, their views and attitude changed significantly at late stages. For instance, at the moving through stage, the differences between these two countries in the areas such as language, cultural and custom differences, living and entertainment habits, and also education systems started showing impact. As a result, almost all of them realised that making friends with home students was not as simple and straightforward as they had anticipated. At the moving out stage, the entire group seemed to have actively given up on trying. This was in part because of their unsuccessful experience. In addition, many (8 out of 12) felt that it was unnecessary for them to make effort anymore, since their programme was close to finish. Meanwhile, coping with intense academic workload means that the participants had far less time to deal with their social life, and making new non-Chinese friends was not a priority for them, in particular, when they moved into their second semester.

I have no British friends, and know nothing about British culture and customs. To be honest, it is not a big deal for me anymore because I don’t need to stay in this country for much longer.

I have so many assignments [to complete], there seems to be a deadline almost every week … Sometimes I feel that I don’t even have time to shower and eat properly, let alone make local friends.

Academically the whole group also felt that they were disconnected. Although they had not yet received all their results when the moving out interview took place, based on their performance in the first semester (e.g. half of the participants had already failed a number of module assessments already), the participants by and large anticipated that they would not be able to gain the academic results they aimed for initially. The main issues reported were in two areas: assessments and connection with their peers and tutor on the programme. Almost all participants reported that they were really struggling with writing their academic assignments, regardless of the subject they were studying. This as a result not only affected their academic results, but also hindered them from engaging and enjoying their learning. Nevertheless, those who studied Management or Tourism programme reported that they felt they developed a better level of understanding about their subject compared with those who studied Accounting, Finance or Economics. In addition to language barriers, the participants commented that the main challenge relating to academic writing was that they were unclear about how they could produce a good quality assignment that would fully meet the assignment brief, and also their tutor’s expectations, in particular, in relation to the level of criticality expected. In addition, half of the participants did not have any academic writing experiences before coming to Britain. Although the other half did, it appeared that there were many differences between their home institution and the UK institution in the areas such as tutor expectations, academic referencing and the level of support provided.

I know how to get the structure and format right, but I often don’t know what content to put in [for each assignment] … Tutors’ expectations and requirements are different for different modules. In my opinion, the biggest challenge [in assignment writing] is to understand what the individual tutor wants in one’s assignment.

I still find it very hard to write assignments. In fact, it is one of the main challenges for me in the second semester. Sometimes I have no clue at all and don’t know what to write. I often wished that somebody else could write my assignments for me.

Apart from assessments, the participants by and large felt that they did not have many opportunities to get to know their local peers. The allocation to classes resulted in Chinese students mainly studying in a mono-cultural group. When occasionally they were put in a class with a small number of non-Chinese students, some participants (5 out of 12) felt that they were excluded intentionally from their group when doing group-based activities, because of their language ability. On the other hand, many participants believed that their module tutors were not very supportive and made little effort in class to assist Chinese direct-entry students to break down the communication barriers.

When we asked to do discussions, I tried to join, but my group did not welcome me. I think they were all British students, and were just doing the discussion among themselves. I couldn’t join the conversations. To be fair, I didn’t really know what to say anyway. They were talking too fast, I did not understand what they were saying.

There were too many Chinese direct-entry students in each class. I really wished the University took action and grouped Chinese and home students together when we were doing group presentations or discussions in class. This way at least there were a couple local students in each group. Currently we had to be in a group together with other Chinese students, there weren’t really many options for us.

Factors influencing sense of belonging

The factors affecting sense of belonging among this group of Chinese direct-entry students were analysed using Schlossberg’s 4S framework. As discussed above, this framework is made up of four factors: self, strategies, situation and support. Self refers to one’s personal characteristics and strategies refer to one’s coping strategies. These two factors describe an individual’s intrinsic properties. Situation is concerned with the context(s) of transition and support refers to external support one receives. They both describe an individual’s extrinsic properties. Consequently, the themes relating to the factors are grouped into two, namely personal and institutional level.

Personal level

The participants shared similar characteristics, as well as personal and learning backgrounds. For example, they were young, inexperienced and had no previous working experience. Most of them (11 out of 12) did not have any study abroad experience before. Prior to university, they attended gaokao, the National College Entrance Examination (NCEE) in China. Their results were not good enough (e.g. their grades were lower than entry requirements) for them to get a place at a tier one or tier two university. Some of them (4 out of 11) reported that they were even struggling to be admitted to study at a tier three or four university. Studying abroad then became an apparent option for them. They chose the UK and this direct-entry route mainly because of the reputation of the UK higher education and the shorter duration of direct-entry programmes. The details of the participants are provided in the table below ().

Table 2. A summary of the participant details.

In addition, data show that language barriers were not only a key challenge the participants faced, but also one of the main factors influencing their sense of belonging. It appears that the language skills of all participants were weak when they arrived in Britain initially. Almost all of them reported that they were unable to have normal conversations in English, even though their IELTS test result met the minimum entry requirements (e.g. 4.5) for the host institution before entering the UK. At the end of this one-year journey, none of the participants believed that they achieved fluency in English, especially speaking - a goal they set for themselves initially.

Strategy describes the coping strategies adopted by the participants. Socially, the whole group appeared to have adopted a similar approach. They did not have any pre-prepared strategies and shared the ‘go with the flow’ attitude, even though most of them were keen to make new friends with non-Chinese at the beginning. When they faced difficulties and challenges, they withdrew and took no further action. Academically, the participants reacted differently to the academic challenges and adopted different coping strategies. For instance, for personal reasons, two participants were motivated and worked harder than others. Some (4 out of 10) said that they understood that they needed to study harder but did not devote as much as they planned to. The rest of them (6 out of 12) appeared to be losing interest in studies and hence put minimum effort into it.

I made an agreement with my friend - we both would study in University X later together … . In order to get in University X, I need to either achieve a 2.1 degree or an IELTS score of 6.5. I don’t think my English is good enough, so my only hope is to get the degree results required.

In general, I don’t work on my assignments until the last minute. … I am feeling so tired because I am working on assessments constantly … there is no time to rest..I don’t really like life like this.

Context of transition

The literature, as well as the comments of the students, suggest that with regard to the direct-entry route they opted in, it was relatively easier to get admission to their host institution in China. This is because the articulation agreements and partnerships do not need to be approved by the Chinese Ministry of Education (MOE) (Zheng, Citation2014). Therefore, any Chinese institutions or colleges can run articulation programmes, and recruit whoever wants to study abroad, as long as these students are able to pay the fees, which can be much more expensive than the state university degrees. Consequently, the quality of student intake of articulation programmes is likely to be lower than those who are admitted to study in a Chinese institution via the National College Entry Exams (Zheng, Citation2014).

Meanwhile, the whole group reported that the programme (SQA HND or an equivalent) they studied in China was delivered and managed solely by their home institution, and without the contribution of the UK institution. This seems to correspond to what has been reported by Saville and his colleagues in their report, entitled ‘transnational routes to on-shore UK higher education’ (Citation2015).

Institutional level

Participants’ comments suggest that there was a gap between the support institutions provided to Chinese direct-entry students and what these students needed and what these students truly needed in order to manage their transition smoothly in the new learning and teaching environment. The issue raised by the participants is what Pollard and her colleagues (Citation2017) described as ‘inter-institutional variation in course content and structure’ (16). This is mainly due to the fact that there was a lack of communication and understanding between both partner institutions, as reported by the students. For instance, even though in principle the curriculum design and syllabus were supposed to follow the UK style, the participants reported that the actual learning and teaching in China was predominately teacher-centred and exam driven. However, it is worth pointing out that the finding was based upon the perceptions of the students. The appropriateness and effectiveness of the support provided by their home institution needs to be explored further in future research.

Regarding language learning and practice, students reported that they were not provided with a proper authentic English environment. Although the first year of their studies focused on English language, 9 out of 12 participants indicated that this whole year training was not particularly useful and did not help them improve their language skills. In their opinion, the ineffectiveness was mainly the result of the teaching style and the content of the language course, as there were hardly any interactions in class between them and their tutor, and the teaching and learning activities were designed mainly to test their memorisation. The participants by and large also commented that they felt they were not encouraged to develop their subject discipline vocabulary (in English) and reading competency.

The training in year one was completely useless. The content was very broad and shallow. It didn’t cover anything particularly useful. In my opinion, it should be reduced to one semester only, and with a target focus on our IELTS test.

While they were in the UK, the participants believed that their host institution didn’t sufficiently help them settle in and mix with British students in their daily life either. Some (5 out of 12) commented on the lack of sufficient social activities and events for international, in particular Chinese students. In addition, some (4 out of 12) felt that the activities they were offered were not attractive to Chinese students. Furthermore, many participants believed that their module tutors made little effort in class to assist Chinese direct-entry students to break down the communication barriers.

I think the Student Union has overlooked the needs and expectations of international students. I have friends who are studying in other UK universities, and they have had many interesting activities, such as playing table tennis together, and students of different nationalities cooking together. Why don’t we have activities like those ones?

I never attended any activities organized by the Student Union. I can’t even remember what they were … I just had a quick glance at the emails at the time. But I do remember that I wasn’t interested in any … it isn’t my type of entertainment.

Discussion

Using Schlossberg’s transition theory as the theoretical foundation, this paper has developed a good understanding of a small group of Chinese direct-entry students’ experience of belonging. The findings indicate that these students experienced more what Schlossberg described as ‘psychological decline’ than ‘psychological growth’ (Anderson, Goodman, and Schlossberg Citation2011, 48) in this one-year study. They had a very difficult time and expressed a feeling of not belonging in both their social and academic communities. Socially, they did not seem to engage in social activities or develop new social connections with non-Chinese students. They appeared to have confined themselves to their close friend group, which were solely their compatriots. Academically, the whole group was having difficulties in academic writing, and many were struggling with understanding their subject content properly. Their feeling of lacking a sense of belonging in turn affected their achievements and also their overall study abroad experience.

This finding ties well with previous studies investigating transition and belonging of international students. For instance, a qualitative study conducted by Matheson and Sutcliffe (Citation2018) shows that motivation, engagement and identity of international students are affected significantly by how they feel regard sense of belonging. This view is supported by García and her colleagues (Citation2019). Their research indicates that creating a sense of social and academic belonging is critical for supporting international students to settle into a host country environment successfully.

The findings of this paper have the following contributions. Firstly, among the 4 factors (the 4S framework), support, or institutional support (provided by both partner institutions) seems most critical to Chinese direct-entry students, mainly because of the situation relating to this particular study abroad route and the associated partnership agreements between the institutions in the two countries. For example, two-third of their studies were carried out in China, and the duration of the direct-entry programme in the UK was only one-year. These students also joined directly onto an existing programme in the UK and existing academic and social communities. In this context, Chinese direct-entry students probably needed more institutional level support than other international students, in order to go through the steep learning curve and cope with the academic pressure of their final year study.

Secondly, this paper highlights some weaknesses of articulation agreements and direct-entry routes. The Chinese institution did not appear to be clear about the local settings and the expectations of its UK partner, on the other hand, the UK institution did not seem to be fully aware of the learning backgrounds and experiences of these Chinese direct-entry students. This was because the Chinese and the UK institutions did not seem to have contributed to each other’s curriculum design, even though they were in a partnership. In this context, although the two institutions provided support for these students at both ends, prior to their departure and after their arrival, the comments of the participants seem to suggest that there was a gap between the type of support the partner institutions thought the Chinese direct-entry students needed and the actual needs of these students. It is however worth pointing out that further research is needed to explore whether the perceptions of the students truly reflected the situation.

Nevertheless, research shows that the participants had the potential to achieve success in this short period of time if they were given the appropriate and adequate support (Willis and Sedghi Citation2014; Reilly et al. Citation2019). As mentioned previously, when choosing a direct entry route, Chinese students tend to spend most of their time in China (e.g. three years). During this period of time, they receive English language training, study subject related knowledge, and also make preparation academically and socially for their future study abroad. Their learning experience in China serves as the foundation upon which their future study is built. Consequently, partner institutions should have facilitated them to build a solid foundation and develop appropriate academic and social skills required before their departure. Both institutions should also make a great effort to establish and maintain close and regular communication so that the pre-departure and after-arrival support can be joined seamlessly. Since higher education institutions globally have acclimated to online learning, in the post-pandemic era, online communications can be established and carried out much easier. For the same reason, part of the after-arrival support, such as pre-sessional language course and academic skills module may perhaps be delivered to Chinese direct-entry students online, and while they are in China. The focus of the support should be on subject related academic writing, conducting independent learning, coping with final year stress, and managing time effectively in this more student-centred learning and teaching environment. The receiving UK institution should also consider encouraging Chinese and other international direct-entry students to come forward and communicate with the Institution directly to give their feedback or raise their concerns. This may be achieved by appointing bilingual or multilingual staff to join the Student Services and other student support teams, so that these students have the opportunity to speak to the staff in their native language.

Thirdly, among the 4S factors, strategies were also very important to Chinese direct students if they wanted to achieve their intended academic goal. Study abroad is a major transition to all international students, and particularly challenging to those on one-year programme (Khanal and Gaulee Citation2019). Data suggest that most students in this group did not take initiative to prepare or consider coping strategies before and after they arrived in the UK. When they were facing difficulties and challenges relating to their academic and social development, they did not really know what to do. Their lack of preparation was associated factors such as support, self and situation. As discussed already, students perceived that there was a lack of proper institutional support. Additionally, this group of students was young and inexperienced. They were also more used to the Chinese education system and the Chinese learning and teaching style. As the duration of their time in the UK university was short, the problems presented to them were much more challenging than what they had expected, and hence pushed them out of their comfort zone.

And finally, the findings also highlight the critical role language proficiency playing for this direct-entry route. In addition to providing pre-sessional language course before their departure, partner institutions should consider allowing students to attend several online synchronous teaching sessions to get familiar with Academic English and teaching style. A buddy scheme (Bretag and van der Veen Citation2017; Nieto and Nebot Citation2020) has the potential to help Chinese direct-entry students practice English regularly and build new friendships with domestic students.

Limitations and future research

This paper focused on Chinese direct-entry student studying a one-year direct-entry programme in one UK institution. Further research may be conducted to explore whether Chinese direct-entry students at other UK institutions demonstrate a similar experience as the participants in this study and also whether the level of training and support provided at the UK and Chinese partner institution is similar to what has been identified in this research. In addition, this paper explores only the views of students. It would be necessary and interesting to gather the views and opinions of academic tutors, and professional support staff. Furthermore, it would also be relevant to compare the cross-border transition experiences of Chinese direct-entry students before and after the pandemic, taking the impact of online learning and the changes China is making about English language teaching into account.

In spite of the limits, this paper has a significant contribution to theory and practice relating to international direct-entry students. For instance, it has provided a good insight into the cross-border transition experience of Chinese direct-entry students in the UK, and recommendations for improving more sufficient pre-departure and after-arrival support to this particular group of international students. It also shows that Schlossberg’s transition is appropriate in examining the cross-border transition experience of Chinese direct-entry students. In addition, it has identified the most critical factor influencing the transition, within the 4S framework.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Xianghan O’Dea

Dr. Xianghan O'Dea is a Senior Fellow of Higher Education Academy. She is currently a Subject Group Lead (Logistics, Transportation, Operations and Analytics) at Huddersfield Business School, University of Huddersfield. She has more than 20 years of experience in higher education as lecturer, researcher and academic developer.

References

- Anderson, M. L., J. Goodman, and N. K. Schlossberg. 2011. Counseling Adults in Transition: Linking Schlossberg’s Theory with Practice in a Diverse World. New York: Springer Publishing Company.

- Baker, S. 2022. Has the Pandemic Redirected International Student Flows Forever? Accessed 20th June 2022. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/depth/has-pandemic-redirected-international-student-flows-forever.

- Barrot, J. S., I. I. Llenares, and L. S. Del Rosario. 2021. “Students’ Online Learning Challenges During the Pandemic and How They Cope with Them: The Case of the Philippines.” Education and Information Technologies 26 (6): 7321–7338. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10589-x.

- Barthel, M., J. A. Fava, C. A. Harnanan, P. Strothmann, S. Khan, and S. Miller. 2015. “Hotspots Analysis: Providing the Focus for Action.” In Life Cycle Management. LCA Compendium – The Complete World of Life Cycle Assessment, edited by G. Sonnemann and M. Margni, 149–167. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Berry, J. W. 1997. “Immigration, Acculturation, and Adaptation.” Applied Psychology: An International Review 46: 5–34.

- Bethel, A., C. Ward, and V. H. Fetvadjiev. 2020. “Cross-Cultural Transition and Psychological Adaptation of International Students: The Mediating Role of Host National Connectedness.” In Frontiers in Education. Frontiers Media SA.

- Bottery, M., W. P. Man, N. Wright, and G. Ngai. 2009. “Portrait Methodology and Educational Leadership: Putting the Person First.” International Studies in Educational Administration (Commonwealth Council for Educational Administration & Management (CCEAM)) 37 (3).

- Bretag, T., and R. van der Veen. 2017. “‘Pushing the Boundaries’: Participant Motivation and Self-Reported Benefits of Short-Term International Study Tours.” Innovations in Education and Teaching International 54 (3): 175–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2015.1118397.

- Brunsting, N. C., C. Zachry, and R. Takeuchi. 2018. “Predictors of Undergraduate International Student Psychosocial Adjustment to US Universities: A Systematic Review from 2009–2018.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 66: 22–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2018.06.002.

- Cebolla-Boado, H., Y. Hu, and Y. N. Soysal. 2018. “Why Study Abroad? Sorting of Chinese Students Across British Universities.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 39 (3): 365–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2017.1349649.

- Chen, J., and G. Zhou. 2019. “Chinese International Students’ Sense of Belonging in North American Postsecondary Institutions: A Critical Literature Review.” Brock Education Journal 28 (2): 48–63. https://doi.org/10.26522/brocked.v28i2.642.

- DeVilbiss, S. E. 2014. The Transition Experience: Understanding the Transition from High School to College for Conditionally-Admitted Students Using the Lens of Schlossberg’s Transition Theory. Lincoln, Nebraska: The University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

- Gao, X. 2020. “Proposing a Cross Border Peer Support Programme to Enhance Chinese Direct-entry Students’ Academic Performance and Learning Experience.” Compass: The Journal of Learning and Teaching at the University of Greenwich 13 (1). https://doi.org/10.21100/compass.v13i1.1057.

- García, H. A., T. Garza, and K. Yeaton-Hromada. 2019. “Do We Belong? A Conceptual Model for International Students’ Sense of Belonging in Community Colleges.” Journal of International Students 9 (2): 460–487. https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v9i2.669.

- Gopalan, M., A. Linden-Carmichael, and S. Lanza. 2022. “College Students’ Sense of Belonging and Mental Health Amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Journal of Adolescent Health 70 (2): 228–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.10.010.

- Gov.uk the education Hub. 2022. ”Face to Face Teaching is a Vital Part of Getting a High Quality Student Experience.” Accessed 10th July 2023. https://educationhub.blog.gov.uk/2022/01/17/face-to-face-teaching-is-a-vital-part-of-getting-a-high-quality-student-experience-education-secretary-nadhim-zahawi-writes-to-students/.

- Hewish, D., J. Chelin, M. Williams, J. Saville, I. Collins, R. Danes, and C. Comrie. 2014. “International Direct-Entry Students’ Study Experiences: Phase 1 project report.

- Hu, G. 2012. “Assessing English as an International Language: Guangwei Hu.” In Principles and Practices for Teaching English as an International Language, edited by L. Alsagoff, S. L. Mckay, G. Hu, and W. A. Renandya, 131–151. New York: Routledge.

- Johnson, J., A. Johnson, J. Ilieva, J. Grant, J. Northend, N. Sreenan, V. Moxham-Hall, K. Greene, and S. Mishra. 2021. The China Question. Accessed 10th May 2022. https://www.kcl.ac.uk/policy-institute/assets/china-question.pdf.

- Khanal, J., and U. Gaulee. 2019. “Challenges of International Students from Pre-Departure to Post-Study: A Literature Review.” Journal of International Students 9 (2): 560–581. https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v9i2.673.

- Lewis, K. L., J. G. Stout, S. J. Pollock, N. D. Finkelstein, and T. A. Ito. 2016. “Fitting in or Opting Out: A Review of Key Social-Psychological Factors Influencing a Sense of Belonging for Women in Physics.” Physical Review Physics Education Research 12 (2): 020110.

- Li, L., and J. Zhang. 2022. “Academic Adjustment in the UK University: A Case of Chinese Students’ Direct-Entry as International Students.” Journal of Education and Learning 11 (5): 131–141. https://doi.org/10.5539/jel.v11n5p131.

- Liang, A., and P. Hoskins. 2022. “Covid: China 2022 Economic Growth Hit by Coronavirus Restrictions.” Accessed 10th July 2023. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-64286126.

- Martirosyan, N. M., R. M. Bustamante, and D. P. Saxon. 2019. “Academic and Social Support Services for International Students: Current Practices.” Journal of International Students 9 (1): 172–191. https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v9i1.275.

- Matheson, R., and M. Sutcliffe. 2018. “Belonging and Transition: An Exploration of International Business Students’ Postgraduate Experience.” Innovations in Education and Teaching International 55 (5): 602–610. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2017.1279558.

- Mesidor, J. K., and K. F. Sly. 2016. “Factors That Contribute to the Adjustment of International Students.” Journal of International Students 6 (1): 262–282. https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v6i1.569.

- Monaghan, C. 2022. “Transition and the International Taught Postgraduate Nursing Student: Qualitative Evidence from Middle Eastern Students in a UK University.” Doctoral Dissertation. Queen’s University Belfast.

- Ministry of Education. 2019. Notice of the Ministry of Education on the Issuance of the “Measures for the Management of Textbook Materials for Primary and Secondary Schools”, “Measures for the Management of Textbook Materials for Vocational Colleges” and “Measures for the Management of Textbook Materials for General Universities”. Accessed 1st July 2023. https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2020-01/07/content_5467235.htm.

- Navitas Insights. 2023. “South Asia and Greater China: What Matters to Students & which Destinations are Winning?” Accessed 1st July 2023. https://insights.navitas.com/south-asia-and-greater-china-what-matters-to-students-which-destinations-are-winning/.

- Nieto, N. P., and N. Nebot. 2020. “The Cardiff University Buddy Scheme: How to Prepare Outgoing Students Using the Experience of the Year Abroad and Final-Year Students.” Perspectives on the Year Abroad: A Selection of Papers from YAC2018: 43–52.

- Nowell, L. S., J. M. Norris, D. E. White, and N. J. Moules. 2017. “Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 16 (1): 1609406917733847.

- O’Dea, X. 2021. “Portrait Methodology: A Methodological Approach to Explore Individual Experiences.” In Theory and Method in Higher Education Research. Vol. 7, edited by J. Huisman and M. Tight, 131–146. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S2056-375220210000007008.

- Pedersen, P. J. 2010. “Assessing Intercultural Effectiveness Outcomes in a Year Long Study Abroad Program.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 34 (1): 70–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2009.09.003.

- Pollard, E., K. Hadjivassiliou, S. Swift, and M. Green. 2017. Credit Transfer in Higher Education. Accessed 30th June 2023. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/595633/Credit_transfer_in_Higher_Education.pdf.

- Quan, R., J. Smailes, and W. Fraser. 2013. “The Transition Experiences of Direct Entrants from Overseas Higher Education Partners Into UK Universities.” Teaching in Higher Education 18 (4): 414–426. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2012.752729.

- Reilly, D., W. Sun, I. Vellam, and E. Warren. 2019. “Improving the Attainment Gap of Direct Entry Chinese Students-Lessons Learnt and Recommendations.” Compass: Journal of Learning and Teaching 12 (1). https://doi.org/10.21100/compass.v12i1.932.

- Rhinesmith, S. 1985. Bringing Home the World. New York: Walsh & Co.

- Richards, K. A. R., and M. A. Hemphill. 2018. “A Practical Guide to Collaborative Qualitative Data Analysis.” Journal of Teaching in Physical Education 37 (2): 225–231. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2017-0084.

- Rohrer, J. M., T. Keller, and F. Elwert. 2021. “Proximity Can Induce Diverse Friendships: A Large Randomized Classroom Experiment.” PLoS One 16 (8): e0255097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255097.

- Saville, J., and D. Hewish. 2015. Making Sense of Academic Life in the UK: The Voice of the Direct Entry Student at UWE.

- Schlossberg, N. K. 1984. Exploring the Adult Years.

- Senyshyn, R. M. 2019. “A First-year Seminar Course That Supports the Transition of International Students to Higher Education and Fosters the Development of Intercultural Communication Competence.” Journal of Intercultural Communication Research 48 (2): 150–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/17475759.2019.1575892.

- Shanghai Municipal Education Commission. 2021. Notice of the Shanghai Municipal Education Commission on Printing and Distributing the 2021 School Year Curriculum Plan and Explanations for Primary and Secondary Schools in Shanghai. Accessed 1st July 2023. http://edu.sh.gov.cn/xxgk2_zdgz_jcjy_01/20210730/f45f960541cf42268bc69100ed11ee39.html

- Slaten, C. D., Z. M. Elison, J. Y. Lee, M. Yough, and D. Scalise. 2016. “Belonging on Campus: A Qualitative Inquiry of Asian International Students.” The Counseling Psychologist 44 (3): 383–410. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000016633506.

- Tajfel, H. 1981. Human Groups and Social Categories. Cambridge: Cambridge Press.

- Tang, Y., and W. He. 2023. “Depression and Academic Engagement Among College Students: The Role of Sense of Security and Psychological Impact of COVID-19.” Frontiers in Public Health 11.

- Taylor, C. A., and J. Harris-Evans. 2018. “Reconceptualising Transition to Higher Education with Deleuze and Guattari.” Studies in Higher Education 43 (7): 1254–1267. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2016.1242567.

- Wang, Y. X., and L. Bai. 2021. “Academic Acculturation in 2 + 2 Joint Programmes: Students’ Perspectives.” Higher Education Research & Development 40 (4): 852–867. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1775556.

- Ward, C., and W. Searle. 1991. “The Impact of Value Discrepancies and Cultural Identity on Psychological and Sociocultural Adjustment of Sojourners.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 15 (2): 209–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/0147-1767(91)90030-K.

- Willis, I., and G. Sedghi. 2014. “Perceptions and Experiences of Home Students Involved in Welcoming and Supporting Direct Entry 2nd Year International Students.” Practice and Evidence of Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education 9 (1): 2–17.

- The World Bank. 2023. “China Overview.” Accessed 10th July 2023. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/china/overview.

- Yang, Q., J. Shen, and Y. Xu. 2022. “Changes in International Student Mobility Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic and Response in the China Context.” Fudan Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences 15 (1): 23–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40647-021-00333-7.

- Yao, C. W. 2015. “Sense of Belonging in International Students: Making the Case Against Integration to US Institutions of Higher Education.” Faculty Publications in Educational Administration 7 (45).

- Yoshikawa, M. J. 1988. “Cross Border Adaptation and Perceptual Development.” In Cross Border Adaptation: Current Approaches, edited by Y. Y. Kim and W. B. Gudykunst, 140–148. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Zhang-Wu, Q. 2018. “Chinese International Students’ Experiences in American Higher Education Institutes: A Critical Review of the Literature.” Journal of International Students 8 (2): 1173–1197. https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v8i2.139.

- Zhao, X., and W. Xue. 2023. “From Online to Offline Education in the Post-Pandemic Era: Challenges Encountered by International Students at British Universities.” Frontiers in Psychology 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1093475.

- Zheng, L. 2014. “The Impact of Different HE Systems on International Student Learning.” In Academy of Management Proceedings. Vol. 2014, 10774. Briarcliff Manor, NY: Academy of Management.