Abstract

The North China Famine of 1876–79 killed over 10 million people and generated a rise in non-governmental relief both nationally and overseas. This article examines the establishment of the China Famine Fund in Melbourne, Australia, which contributed to famine relief efforts in Shanghai. It demonstrates how the fund’s establishment followed lobbying by Chinese merchants in Melbourne and was made possible by pre-existing Chinese-European collaborative social and commercial networks. In highlighting the fund’s establishment, this article draws attention to the cultural influences of Chinese merchant philanthropy, the global mobilities of famine reportage, and philanthropy as a site for elite cultural encounter.

Lovingly dedicated to my late father, Noel Victor Comley,

who never stopped encouraging me to write.

Introduction

On 20 May 1878, a deputation of prominent Chinese merchants paid a formal visit to the mayor of Melbourne, John Pigdon.Footnote1 They asked for his assistance in collecting funds to relieve victims of what would later be known as the North China Famine. These merchants – among others Lowe Kong Meng, Cheok Hong Cheong, and Ley Kum – had, on the Saturday prior, collected over £130 ‘amongst the Chinese’, and wanted to expand relief efforts to ‘their fellow countrymen throughout this and the neighboring colonies’.Footnote2 In June the mayor’s office established a China Famine Relief Fund Committee (hereafter the Melbourne fund).Footnote3 The committee consisted of Chinese and British merchants and missionaries including Kong Meng and Cheong. They would meet at the Melbourne Town Hall every week until November, when the fund totalled £3899.Footnote4 The committee remitted funds in instalments via the Oriental Bank to an interdenominational Anglo-American missionary-run China Famine Relief Fund in Shanghai, hereafter referred to as the Shanghai fund.Footnote5

This article focuses on the foundation of the Melbourne committee, arguing that mutually beneficial and desired collaboration between Chinese and British organisers was unique to this fund’s establishment. Earlier in April, Kong Meng ‘and other leading Chinese merchants’ had publicly proposed opening a fund, to little response.Footnote6 Scholars attribute this lack of interest to the anti-Chinese racism of the time,Footnote7 which portrayed Chinese settlers as antithetical to the colonial ideal of Australians as hardworking, egalitarian, democratic, self-governing, and white.Footnote8 This antithesis was perhaps reflected in Sydney: when Chinese merchants opened a China Famine Fund at the end of May, the Sydney City Council opted not to open a fund because the ‘merchants in Sydney’ had taken care of it.Footnote9 Yet when the Chinese deputation visited the mayor of Melbourne, they were well received and participated in the fund’s committee. The influence of the Chinese deputation and the prominent involvement of Chinese merchants in the establishment of the Melbourne fund suggests greater nuance in Chinese-European encounters beyond racial reductionism. As Sophie Loy-Wilson has posited, ‘Sino-Australian scholarship has yet to grapple with Chinese “agency” in the shaping of Australian civic life’.Footnote10

Analysis of the establishment of the Melbourne fund lends crucial insights into the circulation of ideas, information, and money between Australia and China, specifically between Melbourne and Shanghai, and ultimately, the famine fields of inland China, Shanxi. The fund reveals previously unexplored connections between Chinese settlers in Australian colonies and their compatriots in China that extend beyond their hometowns, or qiaoxiang (僑鄉), which were largely limited to southern China; and that shape the contributions of Chinese–Australians to China as part of a broader, and emergent, proto-nationalist imagination in China, Hong Kong, and the Nanyang region, as explored by other scholars in different contexts.Footnote11 I first situate the motivations of Chinese merchants in Victoria within the context of Chinese merchant philanthropy. I then examine how Chinese settlers exerted influence on pre-existing Victorian settler charity systems through mutually beneficial social networks that were tied to Sino-Australian commercial interests. Throughout, I interrogate the infrastructure of global famine reportage across British, American, and Chinese empire systems and link (Chinese–) Australian history of the late nineteenth century with historiography of famine relief in China. In doing so, this article contributes to scholarship that reorients global Australian historiography towards a renewed focus on Asia.Footnote12

Materials and methods

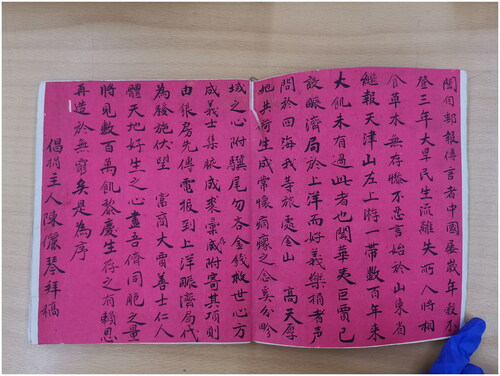

The records of the Melbourne committee, compiled by the Melbourne Town Clerk, document Chinese and non-Chinese collaboration in 1870s Victoria.Footnote13 While European voices predominate the committee records, a close analysis of the letters, subscription lists, and minute book, reveal the presence and actions of Chinese organisers and donors in tandem with European participants. The scope of this article is on the organisers. Further work on its donors, many of whom remained unnamed or collectively titled ‘the Chinese residents of …’, is the work of future projects.Footnote14 The committee records include a letter, written in literary Chinese, pasted inside subscription record booklet.Footnote15 It is the only Chinese-language record of this archive, and to my knowledge has not been consulted before.Footnote16 The letter makes explicit the links between the Chinese–Australian community and the northern China disaster, and thus offers both questions and answers to the ways in which the Melbourne fund was connected to the famine – through its narrative, reportage, and financial logistics. Given the dearth of Chinese-language documents in Australia before the 1890s, this Chinese letter and its provenance within the Melbourne Town Clerk’s Melbourne fund record is an important source in (Chinese–) Australian historiography.

Key frameworks adopted in this article are that of core-periphery relationality and social networks, which help to conceptualise how charitable activities emulated, or were directed towards, a central ideology, leadership, or location.Footnote17 The constellation of core and periphery is situational: in the case of the Melbourne fund, the core could be an emerging Chinese nation; merchant-philanthropic communities of practice; British mentalities of charity; or the famine relief fund itself. Core-periphery relationality also draws attention to direction, in this case from periphery to core. In doing so, this article pays attention to the circulation of newspapers from China or Britain and their effect on the imagination of these core-periphery relationships. Social networks were crucial to the formation of the Melbourne fund. Zoe Laidlaw explains how the ‘ready-made imperial networks’ of missionary societies bolstered humanitarian networks.Footnote18 These ‘ready-made’ social networks were particularly important in the case of the Melbourne fund, whereby the Chinese merchants involved in its establishment tapped into networks of municipal charity, colony-wide church connections, and gentleman–philanthropists already active in and around Melbourne. This article pays close attention to the ‘complex web of social relations’ between Chinese and non-Chinese organisers in Melbourne.Footnote19 In this sense, it is not the aim of this article to overemphasise the agency of Chinese merchants such as Kong Meng or Ley Kum in Australian history. Rather, the article uses the fund to reveal the influences, attachments, and contributions of Chinese elites within British systems.

Famine and Overseas Chinese historiography

The North China Famine (1876–79) was a drought-famine that killed a total of 9–13 million people,Footnote20 and was widely reported, including in England, America, southern China, Hong Kong, and Australia.Footnote21 Scholars have explored the famine in terms of the rise of non-governmental merchant philanthropy and foreign missionary relief in China; the associated rise of a Chinese public sphere; and the ways in which the famine was mediatised in critique of an ailing Qing state.Footnote22 Less scholarship has focused on Overseas Chinese contributions,Footnote23 despite the increasing connectivity of Chinese diaspora in the 1870s, and the significant presence of Chinese settlers in white settler colonies in Australia and California. While Chinese–Australian transnational philanthropy is increasingly receiving attention, most scholarship in this field so far has focused on the 1890s onwards; on political support of the Chinese revolution in the twentieth century; or on family affiliated donations to qiaoxiang via remittance firms run by kinship associations.Footnote24 John Fitzgerald and Mei-fen Kuo, for instance, have framed transnational charity in Republican China as integral to regaining what they call Chinese ‘welfare sovereignty’, whereby the ‘international humanitarian gaze’ and ‘foreign intervention’ needed to be tackled.Footnote25 Yet it is important to note that this competitive narrative of private philanthropic contributions to Chinese ‘welfare sovereignty’ can be traced to the North China Famine, when merchant–philanthropists criticised Qing famine responses, and officials and merchants alike framed foreign humanitarian interventions as competitive threats to China's capacity to help itself.Footnote26

Charity has been one of the more useful ways in which Chinese–Australian historical encounters with European settlers has been explored.Footnote27 As colonists, British and Chinese subjects shared an interest to improve their and others’ livelihoods. Victoria had nothing equivalent to Britain’s Poor Law, reflecting entrenched Malthusian fears that such laws would ‘pauperise’ the poor.Footnote28 Nevertheless, Victoria had an extensive ‘mixed market’ charity system of private philanthropy, community charity, and municipal contributions to otherwise autonomous organisations such as the Ladies Benevolent Society.Footnote29 Private organisations were financially floated by philanthropic ‘subscribers’, who while originally having a say at board meetings, by the end of the nineteenth century were simply donors.Footnote30 Community charity included Chinese communities, which donated to local hospitals and participated in fundraising events, such as the Bendigo Easter Fair.Footnote31 Victorian charity systems emulated British ones, especially the faith-based organisations;Footnote32 and municipal bodies regularly involved themselves in the establishment of, and financial subsidies to, charitable institutions.Footnote33 It was not unusual for a deputation to visit the mayor for charitable support.

Both British and Chinese charity systems reproduced to some extent their ‘home’ models, but in ways that were similar.Footnote34 Philanthropy for both was an engine for social prestige. W.M. Jacob attributes the paradox of British philanthropic zeal, despite fears of pauperising the poor, to Christian manifestations of (evangelical) benevolence and compassion towards ill fortune.Footnote35 While doing ‘God’s work’ was surely one motivation, philanthropy also provided access to an ‘old boy’ club of businessmen, politicians, and ecclesiastical leaders that ‘enabled the respectable middle class to associate themselves with their social betters’, irrespective of ethnicity or culture.Footnote36 Charity also looked transnationally, back to the ‘core’. In 1862, when the Mansion House Fund of London called for subscriptions for the Lancashire Fund, Melbourne subscribers donated £365.Footnote37 Chinese–Australian kinship associations, or huiguan (会馆), likewise modelled the huiguan of the Nanyang and China, and settlers remitted to their southern Chinese qiaoxiang to build roads, schools, and relieve disasters.Footnote38 Several members of the Melbourne fund committee were avid philanthropists and members of the same political, church, mercantile or banking networks, or a combination thereof, including Kong Meng, book importer M.L. Hutchinson, member of parliament (MP) and banking director James MacBain, and MP Alexander Kennedy Smith.

The Melbourne fund provides an early case study of Chinese–Australian transnational famine relief beyond the xiaoqiang, as collaboration with non-Chinese philanthropists and British banking networks. In contrast, Chinese merchants in Sydney also raised funds for the famine, but they did so separately to British settlers, and thus via separate methods of financial transfer. Nor was the Shanghai committee the only organisation, nor the only method by which either Chinese or European donors could contribute to the North China Famine relief. The Melbourne fund adds greater nuance to our understanding of the various ways Chinese–Australians contributed to China and, through this Chinese–European encounter, greater insight into the social lives of at least the more prominent Chinese settlers in Victoria.

A Chinese letter: Chinese merchant philanthropy in Australia

Chinese merchants in Melbourne were significant instigators of the fund, and not merely contributors. The weekend before the deputation to the mayor, Kong Meng and other merchants had raised over £130 at a meeting held at Kong Meng’s firm on Little Bourke St, Kong Meng and Co.Footnote39 They intended this amount to be the ‘the nucleus of a Chinese Famine Relief Fund’.Footnote40 A subscriptions record collected by Kong Meng and C.H. Cheong, which provides an itemised donation list of predominantly Chinese names, all anglicised, are likely the names of the Chinese merchants who made donations at Kong Meng’s office.Footnote41 The names are written neatly and uniformly, and do not indicate whether donations had been paid or promised, suggesting they were collected for the Town Clerk as he prepared his own final committee records. The booklet reveals very little about how Kong Meng and Cheong appealed to these Chinese donors, and even less about why the donors listed – donors such as Sun Kwong On, Sun Sue Shing, or Chun Yut – contributed to the fund.

The Chinese-language letter in the committee records reveals the complex interplay of Chinese merchants living in Melbourne, and the ways in which they may have conceptualised the famine and their relief.Footnote42 Neither dated nor addressed, the Chinese letter seems to be a copy of a letter that was sent to a wide audience: its language and reference to merchant-run famine responses indicated it addressed merchants in Victoria, or ‘on the gold fields’, as part of a community of practice. It was signed off by Ley Kum (陳麗琴, Chan Lai Kam in Cantonese), the ‘head solicitor of donations’ (倡捐主人). Ley Kum, present in the Chinese deputation to the mayor, was a merchant and resident of Melbourne of at least six years, and worked for Kong Meng and Co.Footnote43 It is possible that some Chinese merchants living in Melbourne received this appeal for subscriptions to donate to the North China Famine before they met at Kong Meng’s office, although the letter does not include any explicit invitation. The letter is written in literary/Classical Chinese.

The Chinese letter included in the China Famine Relief Fund Committee subscription records – the only Chinese-language record in this archive; Town Clerk’s Files, Series Two, Public Record Office Victoria (PROV), Melbourne, VPRS 3182.

In the letter, Ley Kum used Confucian principles of benevolence ren (仁), righteousness yi (義), as well as goodness shan (善)to frame famine relief as a method of ‘becoming a righteous person’ (成義士), urging merchants to make significant contributions to the famine relief. The letter first introduced a drought-famine it had learnt of in the ‘news’, ‘in its third year’ (三年旱), dating it to 1878, before briefly discussing the ‘unspeakable’ (不忍言) horrors of the famine. It then referred to both Chinese and foreign merchants (華夷巨賈) who had ‘already established a charity bureau … of which these righteous donors have reputation all over the world, including at our goldfields’.Footnote44 Hong Kong historian Elizabeth Sinn has called this adoption of Confucian concepts the ‘language of charity’.Footnote45 Qing statesman Li Hongzhang, in his appeal to Overseas Chinese in Hong Kong and the Nanyang for relief, readily exploited the ‘language of charity’, which ‘encouraged overseas merchants to do good for and in China’.Footnote46 Sinn suggests Li’s language was also designed to ‘make the marginal migrant merchants’ more palatable as donors to the court, since merchants symbolised the lowest rungs of the Confucian social order.Footnote47 The reference in Ley Kum’s letter of ‘becoming a righteous person’ suggests that the desire to become someone of a higher status or moral standing through philanthropy was also modelled in Melbourne. Additionally, the letter incorporated a Han Dynasty poem metaphor, that of ‘attaching oneself to the tail of a great horse’ fu jiwei (附驥尾). This metaphor described how the attainment of social prestige could be attained through the patronage of greats. As such, while Ley Kum encouraged readers to contribute ‘not stingy’ (勿吝) sums of money, he also argued that ‘many hairs make a fur coat’, implying perhaps that any donation amount, large or small, would contribute to a greater cause.

Ley Kum’s letter created a relationship whereby merchants ‘sojourning on the goldfields’ (旅處金山) were positioned as peripheral contributors to a greater core – to an imagined suffering China, or perhaps the Chinese government. The exclusive mention of a merchant-run relief bureau, and the strategic use of Confucian language to construct a ‘methodised benevolence’ whereby charity could increase one’s own social standing, prompts us to also consider the role of merchant philanthropy in facilitating these connections, and in understanding Chinese–Australian motivations. The merchant-philanthropist was not just a merchant who engaged in charity, but a culturally and socially enmeshed term. According to Confucian governance, merchants – who traded objects but did not produce them – sat at the bottom of a moral and social hierarchy. As they gained wealth, they also strove to increase their social standing by ‘emulating[sic] the scholarly elite’, the morally superior class.Footnote48 This emulation included the appropriation of Confucian language. During the North China Famine, emerging merchant-philanthropists in China mobilised Confucian and Buddhist concepts of morality to frame their contributions.Footnote49 Philanthropy as a vehicle of both social and moral mobility indicated its multiple functions beyond any pure, moral-didactic benevolence. As China historian of famine Joanna Handlin Smith has shown, in a ‘methodisation of benevolence’, merchants altered the previously hierarchical and distanced relations between donor and beneficiary, and instead created ‘flattened’ and complex social networks in which philanthropy served multiple social, commercial, and moral purposes.Footnote50

Overseas Chinese merchants likewise adopted philanthropy to generate ‘prestige’ or connection to China, perhaps no better represented than through the conferring of imperial titles.Footnote51 Before the ailing Qing Government lifted its ban on emigration in the 1890s, titles to Overseas Chinese were conferred in exchange for donations to the state.Footnote52 Overseas Chinese also contributed to the North China Famine and received state recognition, as was the case when Hong Kong’s Tung Wah Hospital received a memorial from the Qing emperor.Footnote53 The memorial tablet was a powerful signifier of one’s attachment to the ‘core’ of the Chinese imperial system. Kuo has also shown how 1890s Chinese-language Australian newspapers encouraged similar Confucian frameworks of doing good.Footnote54 Philanthropy was considered as a means of accumulating ‘merit’ through good deeds, to overcome one’s lowly status as a merchant.Footnote55

The primary merchants present in the Chinese deputation to the Melbourne mayor engaged in methodised benevolence that ‘flattened’ not only their relationship with Chinese authorities but also their relationship to British colonial authorities. Kong Meng, the most prominent merchant, involved in the famine fund from its initial and informal inception in The Argus newspaper, is the best example of this. He had settled in Melbourne in 1854 and built his successful shipping firm, Kong Meng and Co., which operated in shipping and imports between Melbourne and Hong Kong.Footnote56 Kong Meng had been donating to local causes for over 20 years.Footnote57 He reportedly committed £300 in annual charitable contributions, and in an 1878 local paper was referred to as ‘that world-renowned philanthropist’ (although it is possible this was anonymously self-referred).Footnote58 Kong Meng’s status as a ‘mandarin of the blue button’ was referenced in the English-language local media, demonstrating not only his connection to Qing China (including the implication he bought, or ‘donated’, the title) but also the importance he himself would have put on its being publicly acknowledged.Footnote59 Paul MacGregor argues Kong Meng’s ‘fluidity’ between both British and Chinese cultures and elite circles stems from his upbringing in Penang.Footnote60 Louis Ah Muoy, another prominent Chinese merchant present in the Melbourne deputation, and Kong Meng were also both community leaders of their respective home origins, the See Yap and Sam Yap kinships associations, or huiguan, which Smith has outlined as key institutions for merchant-philanthropists.Footnote61

The ways in which philanthropy served commercial or media interests, and vice versa, were necessary for the collaborative establishment of the Melbourne fund committee. Kong Meng’s 1861 donation to the Acclimatisation Society, for instance, may have allowed him to become closer to Edward Wilson, proprietor of The Argus, a daily paper which routinely advertised Kong Meng’s business.Footnote62 It was The Argus that accepted and published initial informal donations for the famine, and which first published Kong Meng and other Chinese merchants’ interest in opening subscriptions to the Melbourne fund: illustrating how local colonial authorities were attracted to, sought out, and then appealed to the demands of, local Chinese charity organisers, allowing Chinese communities some social leverage and mobility, as Pauline Rule and Amanda Rasmussen have described.Footnote63 Chinese-run charity also signified, for the public, a benevolent approach to Victoria’s laissez-faire welfare. In an 1877 Supreme Court case for libel, the successful prosecutor Ley Kum demanded that the proprietors of The Australasian (one of whom happened to be Wilson) donate £100 to a charity of his choosing.Footnote64 It was important for Ley Kum to be seen as a benevolent gentleman, especially since the libel case was to clear his name of having shirked gambling payouts.Footnote65 Charity, then, granted Chinese communities political leverage, and was weaponised strategically under British governance systems; but was also used to increase the public image of Chinese merchants performing the art of ‘doing good’.Footnote66

Rather than referring to the Qing state, the reference of ‘attaching oneself to greats’ could also suggest that Chinese merchants ‘in the goldfields’ could ‘attach’ themselves to the colonial authorities through the Melbourne fund. In her analysis of Chinese-language Australian newspapers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Mei-fen Kuo demonstrates how Confucian values were adapted to express and to suit new modernist ideals of equality and democracy, while at the same time creating a space for ‘Chineseness’ that was not couched in colour, but rather in culture.Footnote67 In their 1879 anti-racism publication The Chinese Question, editors Kong Meng, Cheong, and Ah Muoy adopted Confucian principles as persuasive techniques to illustrate not only the moral superiority of China, but the role of upstanding Chinese citizens as ideal defenders of British rule of law and governance, which emphasised equality.Footnote68 Chinese charity contributions to Victorian ‘colonial charity models’ often utilised Chinese imperial symbolism and regalia, which should perhaps be considered less as a representation of their own political beliefs than a blended cultural import.Footnote69 As Edgerton-Tarpley has shown, merchant- and gentry-philanthropists in Shanghai and the wealthy Jiangnan region adopted western technocratic and laissez-faire economic approaches to diagnose the famine and prescribe its relief, criticising the Qing government and arguing for reform in the process.Footnote70 The alternative, hybridised appropriation of Confucian and Buddhist symbology suggest that these terms of ‘benevolence’ and ‘righteousness’ did not necessarily denote a simple or reductive relationship to the Chinese state, nor to Confucian governance, but were an independent utilisation of cultural capital to carve a hybridised merchant-philanthropic identity for colonial settler Chinese.

Another key aspect of the Chinese merchant donations to the fund is attitudes to Christianity. Ley Kum’s letter did not mention missionary works but focused exclusively on merchant donors. Yet the Melbourne fund was clearly affiliated with the interdenominational missionary-run Shanghai committee. Local press reported positive responses from ecclesiastical leaders in England.Footnote71 The Melbourne fund was also heavily supported by local ecclesiastical networks: donations came from various churches around Victoria, including Wesleyan, Catholic, and Presbyterian denominations;Footnote72 and money was often collected at church lectures, reinforcing Jacob’s position that British Victorian-era charity networks were fuelled by Christian sentimentalities.Footnote73 Moreover, Chinese Christians Cheong and Moy Ling were present at the deputation, with Cheong active throughout the committee’s activities, suggesting his religious affiliation granted him greater respect among the European members.Footnote74 The omission of Christianity in Ley Kum’s letter suggests he wrote the appeal before the Melbourne fund’s association with the missionary-run Shanghai committee had been established – and that the original intention had been to send funds directly to Shanghai, or China. If this is the case, the emphasis might reflect the proportionate interest of the Chinese merchants in Melbourne in the network of extra-governmental merchant philanthropy in China. The omission of Christian relief could also denote the reception of alternative sources of information of the famine that reached Melbourne from China.

While it is difficult to trace the movement and reception of Chinese-language famine reportage to Australia, it is worth considering the changing nature of journalism in 1870s Shanghai and Hong Kong, and the subsequent co-construction of a nationalist or proto-nationalist consciousness with these newspapers.Footnote75 It was these newspapers, such as Shanghai’s Shenbao, that published hybridised merchant-philanthropic approaches to the famine.Footnote76 During the North China Famine, the emerging Chinese public sphere juxtaposed Christian missionary famine relief against merchant philanthropy and state relief practices, through frameworks of moral competitiveness.Footnote77 While it is unclear how often, and how seriously Chinese communities read them, the highly mobile, transnational nature of Chinese sojourners, communications, and businesses suggest that Chinese merchants had independent access to news from Hong Kong and Shanghai.Footnote78 In August, for instance, Cheong independently received a copy of Shanghai’s English-language paper Celestial EmpireFootnote79; and the Sydney firm On Chong and Co. imported newspapers from Hong Kong.Footnote80 Kuo, drawing on Benedict Anderson’s concept of ‘imagined communities’, has argued of the Chinese-language press of Australia in the late nineteenth century that it co-constructed a national Chinese–Australian identity.Footnote81 While beyond the scope of this article, more attention could be turned to the ways in which Chinese journalism in China and Hong Kong was transferred to the Australian colonies before the 1890s, and how these impacted or influenced Chinese–Australian imaginations of the famine. Ley Kum’s omission of missionary relief, and emphasis of merchant relief, may mirror the kind of discourses emergent in the Chinese newspapers of the time.

Finally, it is noteworthy that the Chinese merchants appealed to the mayor, thus supporting the explanation that the ‘core’ for Chinese donors was in fact the British colonial authorities rather than the Qing state; and that famine relief, while reflecting contributions to a greater China cause, would assist the Chinese in leveraging their own social capital in their chosen home. The Chinese donors or merchants who gathered at Kong Meng’s office and contributed to the ‘nucleus of the China Famine Fund’ did not aim to receive recognition by the Qing state: while publicising the names of donors was a common practice in the Sinosphere, and necessary for receiving official recognition, the list of Chinese donors to the Melbourne fund written in English, and the pooling of their donations, prevented the tracing of names or identities to Chinese equivalents.Footnote82 In contrast, during the North China Famine, Chinese newspaper Shenbao, as well as the Tung Wah Hospital group, published donor lists; and by the 1890s, donation lists were routinely published for local and overseas charity causes in the Chinese-language newspapers of Australia.Footnote83 That the Chinese donations in Melbourne were pooled into the mayor’s fund indicate they were not targeted at Chinese state recognition.

Social networks

The Chinese merchants capitalised on their social and commercial relationships with European merchants to leverage the establishment of the Melbourne fund. Aside from already mentioned Chinese, the Melbourne committee meetings were attended by prominent European (largely Scottish) merchants, politicians, and missionaries. These included MPs Alexander Kennedy Smith and James MacBain; Scots Presbyterian minister Reverend Charles Smith; merchants Robert Harper and M.L. Hutchinson; and, of course, John Pigdon, the Honourable Mayor of Melbourne.Footnote84 Chinese and European merchants would have come into contact through mutually productive commercial or political engagements. Kong Meng, Ah Muoy and Cheong, for instance, had strong, life-long relationships with Britons, including Mark Last King, MP.Footnote85

Chinese settlers maintained nuanced and cooperative relationships within and with colonial ‘models’ and benefited from these, especially through intersecting commercial and civil society interests.Footnote86 While Chinese–Australian historiography generally regards Chinese settlers as having little agency in influencing non-Chinese or British politics and affairs, Chinese communities in Bendigo, Ballarat, Ararat, Castlemaine and Melbourne, utilised Chinese costume, martial arts, and opera in charity fairs, which exploited the othered fascination of Europeans to draw crowds – and cash – to the cause.Footnote87 However, the Melbourne fund did not rely on fetishised Chinese entertainment, and instead turned to well-entrenched municipal systems of colonial charity. Paul MacGregor has suggested that Kong Meng was cognisant of the success of the Indian Famine Relief campaign of the previous year, also run by the Melbourne Town Clerk, and desired to capitalise on this pre-existing system of humanitarian relief.Footnote88 While this offers a sound explanation for why the Chinese merchants may have sought the assistance of the mayor, it does little to reveal the reasons for the interest of the mayor – or any of the non-Chinese merchants – in actually running the fund. The dynamics of the Melbourne fund illustrate how the mayor, and the non-Chinese merchants involved in the committee, also benefited from their relationships and cooperation with Melbourne’s Chinese residents.

This social capital is most evident in the Chinese deputation in May. As several Victorian papers reported, it was not the Chinese merchants or missionaries themselves who spoke, but rather Smith, who spoke on their behalf. The Kyneton Guardian reported that ‘[a]t the request of the deputation Mr A. K. Smith read a paper’ and that ‘Mr A. K. Smith stated that the sum of £130 was collected amongst the Chinese on Saturday’.Footnote89 Smith was a member for the Legislative Assembly representing East Melbourne and had served as mayor of Melbourne from 1875 to 1876. When he left his post as mayor, he had been presented by the Chinese residents with ‘a full-length portrait … in his robes of office’, demonstrating that his relationship with Chinese people in Melbourne had been more than cordial.Footnote90 A Scot who had migrated to Melbourne in 1854, Smith was a prominent mining engineer and science enthusiast, and a member of several learned societies, including the Royal Society, of which Kong Meng was also a member.Footnote91 His relationship with Kong Meng was particularly long-lived: in the mayor’s fancy dress ball in 1865, Kong Meng and Smith cross-dressed in each other’s’ elite ethnic clothing, with Kong Meng as an ‘early monarch’ and Smith as a Chinese mandarin.Footnote92 The fact that in 1878 Smith, a member of the Legislative Assembly, acted as spokesperson of the Chinese merchant deputation reflects a level of friendship, commercial interest, or otherwise mutual benefit that spoke beyond the racial discrimination so prevalent in Victoria. These ‘old boy’ relationships were integral to facilitating the outcome of the Melbourne fund, for Chinese and British alike.

Existing commercial activity with Chinese merchants, and further potential trade with China may have been the motivation for non-Chinese merchants’ participation in the formation of the Melbourne fund. On 25 May, a group of British merchants and businesses appealed to the mayor to hold a meeting of citizens to discuss how they could contribute to the famine.Footnote93 Some of these merchants had direct business dealings with Chinese merchants, such as John Turnbull of Turnbull and Co.Footnote94 Others, such as Robert Harper, James MacBain, and M.L. Hutchinson, engaged in industries shared by Chinese merchants, such as banking and international trade. These three men were also keen Presbyterians, and would work closely with Cheong in the committee’s operations and meeting.Footnote95 In their requisition to the mayor, the European merchants referenced not only the ‘grounds of general philanthropy and sympathy with the Chinese residents’ but also their ‘commercial relations with that [Chinese] empire’ as prime motivations to establish a fund.Footnote96 Despite Victoria’s long history of anti-Chinese discrimination, the colony’s economy benefited from Chinese-run international trade and commerce, which many understood with clarity.Footnote97 European businessmen and businesses had long enjoyed profitable relationships with Chinese merchants and storekeepers.Footnote98 While this interest was not necessarily couched in anti-racism ideals (European merchants about-faced if their commercial interests were not aligned), ‘pro-China cliques’ lobbied in the interest of Chinese merchants in 1870s Melbourne, Sydney, Cooktown and Darwin.Footnote99

Another aspect of the social capital fostered by the Chinese deputation is the presence and role of Chinese Christians, namely Cheok Hong Cheong and Moy Ling. Cheong was a second-generation emigrant, his father a missionary at the Presbyterian Chinese Mission at Ballarat, and would live a life as a social activist and missionary for the Chinese community of Victoria.Footnote100 Moy Ling had arrived seemingly as a goldminer, and had been educated and converted by Wesleyan missionaries.Footnote101 It is likely that the leadership and enthusiasm of Christian Chinese, especially Cheong, assisted in the legitimacy of the committee’s engagements in China for various churches around Victora. An English-language circular published by the Melbourne fund committee [hereafter the circular] appealed through a plea of ‘common humanity’, reflecting the global evangelising ambitions of Christians who saw all suffering Chinese as their ‘brethren’ by including Chinese Christians in leadership positions.Footnote102 This humanitarian philanthropy was embedded in what Schauer has called a ‘pillar[sic] of Victorian middle-class masculinity’.Footnote103 Indeed, many of the European merchant committee members were also active in the Presbyterian Church community, forging a link between religion, philanthropy, and the upper-class of Victoria. Cheong, both a merchant and missionary, was one of the most vocal and present members throughout the committee meetings. He was often called on to explain the condition of the famine to European audiences: it was Cheong who was asked to describe the famine in one of the first committee meetings.Footnote104 The Chinese Christian inclusion in the committee was a useful factor that assisted in the legitimacy of the cross-cultural collaboration, and perhaps offered a unifying language to bridge disparate moral and spiritual approaches to the famine. This might also explain the omission of Christian references in Ley Kum’s Chinese letter: while it was necessary to speak to a Chinese merchant-philanthropic audience, Christian networks facilitated cooperation with the British.

Mobilising media

The Melbourne committee’s (choice of) contribution to the Shanghai fund needs to be considered in the context of global press circulation and Victorian attachment to the British Empire, and the recognition of this British imperial attachment by Chinese settlers. In late June, the Melbourne committee published the circular formally soliciting donations from ‘all municipal corporations’ and ‘all the country papers’ in Victoria, as well as the ‘heads of religious denominations and to ministers of churches’.Footnote105 While Kong Meng and Cheong had originally been tasked with drafting the contents, Cheong and Reverend Charles Strong ultimately prepared it.Footnote106 The circular described the famine and referenced ‘Chinese and English newspapers’ as its sources, including the Peking Gazette and Hong Kong’s Daily Press, indicating the dynamic infrastructure of information that reached Melbourne: other papers that have been traced to Melbourne, include Shanghai’s North China Herald and Celestial Empire, and mail updates from London. The circular described the horrors of the famine in greater detail than Ley Kum’s letter, describing the ‘swarms of helpless women and children’, ‘the sale of human flesh’, and the suicide of parents to spare themselves the ‘pain of witnessing their children’s anguish’.Footnote107 The circular then introduced a ‘Committee of Merchants, Missionaries (of all denominations) and other gentlemen of positions in Shanghai and Hong Kong’ and firmly associated its efforts to this committee in its efforts to aid the ‘Chinese Government’.Footnote108 It ended with a note that subscriptions would be ‘received and acknowledged’ by the mayor of Melbourne, John Pigdon. A committee list included Kong Meng and Cheong, MacBain, Harper and Strong.

The circular created a tri-part hierarchy of core-periphery relations, wherein the Melbourne fund, spearheaded by the mayor, became a metropolitan core for aspiring gentlemen in the colony to be recognised for their humanitarian contributions; and where the committee itself was framed as peripheral to a larger benevolent committee of ‘[g]entlemen of positions’ of ‘all denominations’ stationed in China and Hong Kong. Donors might conceptualise themselves as part of a larger network of western charitable aid, linked to British imperial or Christian missionary endeavours and centralised around the London metropole.Footnote109 In their subscription letter, contributors often apologised to the mayor for not having sent more; and eagerly awaited the mayor’s acknowledgement: one memorandum said, ‘I have not yet received any acknowledgement of another cheque … which I sent you two or three weeks ago’.Footnote110 The mayor also regularly acknowledged donors in The Argus, indicating that public recognition was an important component of the practice of donations.Footnote111

While the Melbourne fund clearly cited efforts in ‘Hong Kong and Shanghai’ and not Britain, the committee surely conceptualised itself as contributing to a British imperial humanitarian presence in China. Pigdon inaccurately addressed the Melbourne fund’s first remittance of £1200 to the ‘British Consul Fund for the Relief of the Chinese Famine’ in Shanghai, suggesting that he or the committee had initially believed the Shanghai-based committee to be intrinsically operated by the British government in China.Footnote112 Moreover, when Kong Meng expressed interest in opening a fund in April, newspapers reported that the Archbishop of Canterbury had presided over a March fund meeting in Lambeth, London, to do the very same.Footnote113 The British had responded with enthusiasm by establishing a Famine Relief Fund in February.Footnote114 London’s committee would ultimately telegraph monthly remittances to Shanghai to a total sum of 113,320 silver teals, or over £32,000.Footnote115 British imperial emulation – that is, modelling the responses from London that were reported in the press – remains a strong explanation for the enthusiasm of those who did respond.

Twomey and May have argued that Australia’s desire to prove it was an ‘integral portion of Empire’ contributed to the success of its 1877 Indian Famine Relief Campaign, which raised £52,000.Footnote116 They attribute the comparatively meagre amount of £3899 raised by the Melbourne fund to a broader colonial anti-Chinese racism, as well as the fact that China was not a part of the British Empire and thus had far less claim than India for imperial humanitarian provisions.Footnote117 This is certainly true: the North China Famine did not produce any comparable colony-wide zeal to that which the Indian Famine did, which extended beyond the realm of ecclesiastical networks so prominent in the Melbourne fund.Footnote118 Yet the Melbourne fund can also be looked at in comparison with other cities that donated to the Shanghai fund. These cities included Adelaide, ‘Northern Tasmania’ (presumably Launceston), New York, Manchester, London, Otago, Calcutta, Penang, Singapore, Hong Kong and Kobe.Footnote119 Melbourne was the second-largest overseas contributor after London, including Hong Kong.Footnote120 Given the details of the famine came largely from Anglo-American missionary networks stationed in China, and circulated via England, it is likely many donors felt that they were contributing to a larger network of British Christian humanitarian service. As MacBain posited in the first committee meeting, they were ‘bound to help the distressed’ on the ‘mere ground of humanity’.Footnote121 It is notable that no contributions are listed from California, an analogous site of racial tension stemming from Chinese mining settlers in an Anglo settler system.

A brief (and incomplete) comparison with other Australian cities that contributed more broadly to the North China Famine further underscores the unique, and successful, collaborative effort of the Melbourne Fund. Between 27 May and 6 June, Chinese merchants in Sydney opened a Chinese Famine Fund. Of subscriptions from both European and Chinese merchants, donors were overwhelmingly Chinese.Footnote122 The fundraising period was short: after one week of advertising, treasurers On Chong and Co. and Sun Kim Tiy thanked the ‘liberal contributions of their countrymen, and those of their European fellow-colonists’ to a total of £1004 and effectively closed the fund.Footnote123 While the process of remittance is less documented than the Melbourne fund, it is likely that the Chinese merchants donated funds directly to the Chinese state through Hong Kong, where On Chong and Co. chartered ships and traded, among other things, newspapers.Footnote124 Conversely, the Adelaide China Famine Relief Fund mirrored the missionary-based motivations of global Anglophone contributions and, like the Melbourne fund, remitted directly to Shanghai.Footnote125 Like Melbourne, the Adelaide fund was formed of politicians and ecclesiastical leaders, including the Mayor of Adelaide, which mirrored the interwoven social networks of prestige so indicative of British Victorian-era philanthropy.Footnote126 Their meeting summaries included commentaries of missionary reports from China, and of the London Famine Relief Fund, which emphasised the core-peripheral relationality towards Britain and the way in which global press informed inspirations for relief.Footnote127 It did not have any visible Chinese leadership, although Adelaide Chinese merchant Way Lee would later publicly involve himself in transnational disaster relief in 1888.Footnote128 The Melbourne fund is unique in that the City of Melbourne and its Chinese merchants were collaboratively involved from the beginning, placing the ownership of the fund on neither, or both, ethnic or cultural group, and appealing to both the ‘centres’ of Chinese merchant philanthropy and British humanitarian missionary zeal.

When he advertised opening a fund for the North China Famine in April 1878, it is unlikely that Kong Meng knew that he and his fellow Chinese merchants would raise and remit almost £4000 to an Anglo-American interdenominational missionary-based relief fund in Shanghai. The Melbourne fund’s establishment could not be attributed to the Chinese deputation alone but was a product of situatedness. Networks of long-standing social, commercial, and ecclesiastical networks with European settlers transcended the pure function of their original relationships and encouraged not only donations but also mercantile lobbying. The well-established charity networks of municipal support and philanthropic social mobility, modelled off British systems, gave precedence for the City of Melbourne to run the fund and contribute financially to an autonomous and external administrator. The timing of British and Chinese press circulation, which reported instances of fund relief and appeals from British cores in London, from British missionaries in China, and from Chinese state officials, motivated readers to contribute. Lastly, the sheer presence of Chinese settlers in Melbourne and the role of Melbourne as a trading, immigration, and information hub facilitated the productive commercial networks and interests between both London, Hong Kong, and Shanghai.

Conclusion

This article has shown how leading Chinese figures in Melbourne successfully lobbied the mayor of Melbourne to open a relief fund to support famine victims in northern China in 1878. Figures such as Lowe Kong Meng, Ley Kum and Cheok Hong Cheong, leveraged local social and commercial networks, but also utilised global information networks, to appeal to European merchants and politicians’ own commercial and humanitarian sensitivities. While the North China Famine struck five provinces in northern China, Overseas Chinese in Melbourne reacted to and engaged with its relief through channels predominantly attributed to western instigators, fostering cross-cultural exchanges and collaboration otherwise contested in China and on the goldfields.

It is important to note, however, that the Melbourne fund committee was a space for the elites, and that the cooperative relationship between Chinese and British merchants did not reflect the lived reality of all Chinese settlers. Moreover, the situatedness of these productive relationships was tenuous. Not two weeks after the closure of the Melbourne fund, seamen’s strikes broke out in Sydney against the employment by the Australian Steam Navigation Company of Chinese labour. The strikes extended to Melbourne, where unionists formed the Victorian Anti-Chinese League.Footnote129 It was in response to these anti-Chinese unionist strikes that Kong Meng, Ah Muoy and Cheong published their pamphlet ‘The Chinese Question’, which argued for the civility of Chinese customs and for the right of Chinese settlers to freely migrate.Footnote130 Despite their recent productive relationships through the Melbourne fund, the Chinese merchants’ advocacy was met with disdain. A meeting of Richmond ratepayers with the mayor noted that the ‘Chinese merchants … grew fat on … the slave labour of their countrymen’, and further that the ‘Chinese ought not to be allowed to associate with Europeans’.Footnote131 While Chinese merchants involved in the Melbourne fund leveraged their ‘old boy’ commercial networks for their benefit, this leverage seems to have been an exception to the rule for Chinese settlers in white colonial Australia.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Beatrice Trefalt and Koji Hirata, my very patient supervisors, and to Sophie Loy-Wilson for her enthusiasm, encouragement, and expertise on Chinese-Australian history.

Disclosure statement

The author reports there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sarah May Comley

Sarah May Comley (they/she) is a Masters of Arts (Research Training) candidate at Monash University. Their thesis explores famine relief from Melbourne, Australia, to the North China Famine, focusing on Chinese-Australian contributions and participation. Broadly, their research interests include the history of (environmental) humanitarianism, transnational disaster subjectivities, and the lived reality (and social history) of Asian-Australian diasporas.

Notes

1 ‘The Chinese Famine’, Kyneton Guardian, 22 May 1878, 2, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/233332176/25147279.

2 Ibid.

3 Minute book, 17 June–9 November 1878, China Famine Fund, Town Clerk’s Files, Series Two, Public Record Office Victoria (PROV), Melbourne, VPRS 3182.

4 Ibid.

5 China Famine Relief Fund, Shanghai Committee, The Great Famine: Report of the Committee of the China Famine Relief Fund (American Presbyterian Mission Press, 1879), 23.

6 ‘Tuesday, April 30, 1878’, The Argus, 30 April 1878, 5, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/5930607/249518; ‘The Chinese Famine’, The Argus, 7 May 1878, 6, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/5931472/249624.

7 Christina Twomey and Andrew J. May, ‘Australian Responses to the Indian Famine, 1876–78: Sympathy, Photography and the British Empire’, Australian Historical Studies 43, no. 2 (2012): 248.

8 Marilyn Lake and Reynolds, Drawing the Global Colour Line: White Men’s Countries and the International Challenge of Racial Equality (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 15–45; John Fitzgerald, Big White Lie: Chinese Australians in White Australia (Sydney, NSW: University of New South Wales Press, 2007), 26.

9 Twomey and May, ‘Australian Responses’, 248.

10 Sophie Loy-Wilson, Australians in Shanghai: Race, Rights and Nation in Treaty Port China (Abingdon: Routledge, 2017), 5.

11 Bryna Goodman, ‘Networks of News: Power, Language and Transnational Dimensions of the Chinese Press, 1850–1949’, China Review 4, no. 1 (2004): 1–10; Elizabeth Sinn, ‘Emerging Media: Hong Kong and the Early Evolution of the Chinese Press’, Modern Asian Studies 36, no. 2 (2002): 421–65; Rudolf Wagner, ‘The Early Chinese Newspapers and the Chinese Public Sphere’, European Journal of East Asian Studies 1, no. 1 (2001): 1–33; Michael R. Godley, The Mandarin-Capitalists from Nanyang: Overseas Chinese Enterprise in the Modernization of China 1893–1911 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981); John Fitzgerald and Mei-fen Kuo, ‘Diaspora Charity and Welfare Sovereignty in the Chinese Republic: Shanghai Charity Innovator William Yinson Lee (Li Yuanxin, 1884–1965)’, Twentieth-Century China 42, no. 1 (2017): 72–96; Tseen Khoo and Rodney Noonan, ‘Wartime Fundraising by Chinese Australian Communities’, Australian Historical Studies 42, no. 1 (2011): 92–110.

12 See other articles in this special issue.

13 China Famine Fund, Town Clerk’s Files, Series Two, Public Record Office Victoria (PROV), Melbourne, VPRS 3182.

14 Subscription letter from J.H. Hearn of Wandiligong, 9 July, Chinese Famine Fund, PROV, VPRS 3182.

15 Booklet and Chinese letter, Chinese Famine Fund, PROV, VPRS 3182.

16 All translations of these records have been made by the author who has Chinese-language skills. Translations were presented and workshopped with other scholars. The author accepts any and all inconsistencies or inaccuracies.

17 Peter Putnis, ‘Shipping the Latest News Across the Pacific in the 1870s: California’s News of the World’, American Journalism 30, no. 2 (2013): 235–59; Tehila Sasson, ‘From Empire to Humanity: The Russian Famine and the Imperial Origins of International Humanitarianism’, Journal of British Studies 55 (2016): 519–37; Elizabeth Sinn, ‘Practicing Charity (Xingshan 行善) across the Chinese Diaspora, 1850–1949’, in Chinese Diaspora Charity and the Cantonese Pacific, 1850–1949, ed. John Fitzgerald and Hon-ming Yip (Hong Kong University Press, 2020), 19–33; Twomey and May, ‘Australian Responses’, 238; Mei-Fen Kuo, Making Chinese Australia: Urban Elites, Newspapers and the Formation of Chinese-Australian Identity, 1892–1912 (Clayton: Monash University Publishing, 2013), 87.

18 Zoë Laidlaw, Colonial Connections, 1815–45: Patronage, the Information Revolution and Colonial Government (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2005), 29.

19 Joanna F. Handlin Smith, ‘Social Hierarchy and Merchant Philanthropy as Perceived in Several Late-Ming and Early-Qing Texts’, Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 41, no. 3 (1998): 418.

20 Kathryn Edgerton-Tarpley, Tears from Iron: Cultural Responses to Famine in Nineteenth-Century China (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008), 1.

21 Ibid, 114; Paul Richard Bohr, Famine in China and the Missionary: Timothy Richard as Relief Administrator and Advocate of National Reform 1876–1884 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1972), 89; Mike Davis, Late Victorian Holocaust: El Niño Famines and the Making of the Third World (London: Verso, 2001), 76; Andrea Janku, ‘Sowing Happiness: Spiritual Competition in Famine Relief Activities in Late Nineteenth-Century China’, Minsu Quyi 143 (2004): 89–118; Liang Liu (刘亮), ‘American Society and the North China Famine in the 1870s: Information, Response, and Knowledge of China’, 古今农业 31 (2017): 68–77; Twomey and May, ‘Australian Responses’, 248.

22 Edgerton-Tarpley, Tears from Iron, 71–156; Yannan Li, ‘Red Cross Society in Imperial China, 1904–1912: A Historical Analysis’, VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 27, no. 5 (2016): 2286; Ruth Rogaski, ‘Beyond Benevolence: A Confucian Women’s Shelter in Treaty-Port China’, Journal of Women’s History 8, no. 4 (1997): 54–90; Vivienne Shue, ‘The Quality of Mercy: Confucian Charity and the Mixed Metaphors of Modernity in Tianjin’, Modern China 32, no. 4 (2006): 411–52; Hu Zhu, ‘Jiangnan Gentry’s Responses to “The Great Famine in 1877-1878”: The Famine Relief in North Jiangsu’, Frontiers of History in China 3, no. 4 (2008): 612–37; Glen Peterson, ‘Overseas Chinese and Merchant Philanthropy in China: From Culturalism to Nationalism’, Journal of Overseas Chinese 1, no. 1 (2005): 87–109; Rudolf Wagner, ‘The Early Chinese Newspapers and the Chinese Public Sphere’, European Journal of East Asian Studies 1, no. 1 (2001): 1–33; Mary Backus Rankin, Elite Activism and Political Transformation in China: Zhejiang Province, 1865–1911 (Stanford: California University Press, 1986), 142–7; Pierre Fuller, ‘Changing Disaster Relief Regimes in China: An Analysis Using Four Famines between 1876 and 1962’, Disasters 39 (2015): 146–65.

23 Ian Welch, ‘Alien Son: The Life and Times of Cheok Hong Cheong (Zhang Zhuoxiong), 1851–1928’ (PhD thesis, Australian National University, 2004); Paul Macgregor, ‘Chinese Political Values in Colonial Victoria: Lowe Kong Meng and the Legacy of the July 1880 Election’, Journal of Chinese Overseas 9, no. 2 (2013): 135–75; Sinn, ‘Practicing Charity’, 24–6; Peterson, ‘From Culturalism to Nationalism’, 94.

24 Kong Hui Ong (王光輝), ‘Fundraising and Patriotism of Chinese Australian through Australian Chinese Newspapers (1894–1937)’ (MA thesis, National Taiwan Normal University, 2018); John Fitzgerald and Hon-ming Yip, Chinese Diaspora Charity and the Cantonese Pacific, 1850–1949 (Hong Kong University Press, 2020); Michael Williams, Returning Home with Glory: Chinese Villagers Around the Pacific, 1849 to 1949 (Hong Kong University Press, 2018); Gregor Benton and Hong Liu, Dear China: Emigrant Letters and Remittances, 1820–1980 (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2018); Gregor Benton, Hong Liu, and Huimei Zhang, The Qiaopi Trade and Transnational Networks in the Chinese Diaspora (New York: Routledge, 2018); Khoo and Noonan, ‘Wartime Fundraising’, 106–10.

25 Fitzgerald and Kuo, ‘Diaspora Charity and Welfare Sovereignty’, 72–96.

26 Edgerton-Tarpley, Tears from Iron, 191; Bohr, Timothy Richards, 84–7; Rogaski, ‘Beyond Benevolence’, 82; Li, ‘Red Cross’, 2286.

27 Pauline Rule, ‘Chinese Engagement with the Australian Colonial Charity Model’, in Chinese Diaspora Charity and the Cantonese Pacific, 1850–1949, ed. John Fitzgerald and Hon-min Yip (Hong Kong University Press, 2020); Amanda Rasmussen, ‘Networks and Negotiations: Bendigo’s Chinese and the Easter Fair’, Journal of Australian Colonial History 6 (2004): 82–7; Elizabeth Sinn, ‘Practicing Charity’, 22–4; Khoo and Noonan, ‘Wartime Fundraising’, 95–9.

28 John Murphy, A Decent Provision: Australian Welfare Policy, 1870 to 1949 (Farnham, UK: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2011), 11–12; W.M. Jacob, Religious Vitality in Victorian London (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021), 234–5.

29 Murphy, A Decent Provision, 29–53; R.A. Cage, Poverty Abounding, Charity Aplenty: The Charity Network in Colonial Victoria (Marrickville, NSW: Southwood Press Pty Limited, 1992), 135; G.F.R. Spenceley, ‘Charity Relief in Melbourne: The Early Years of the 1930s Depression’, Monash Papers in Economic History, no. 8 (1980): 4–5.

30 Murphy, A Decent Provision, 33.

31 Sinn, ‘Practicing Charity’, 23; Amanda Rasmussen, ‘Networks and Negotiations’, 79–92.

32 Murphy, A Decent Provision, 52.

33 Cage, Poverty Abound, 34.

34 Murphy, A Decent Provision, 52–3.

35 Jacob, Religious Vitality, 226–30.

36 B.J. Gleeson, ‘Public Space for Women: The Case of Charity in Colonial Melbourne’, Area 27, no. 3 (1999): 198.

37 John Watts, The Facts of the Cotton Famine (Hoboken: Taylor & Francis, 2013), 168.

38 Michael Williams, Returning Home with Glory, 66–119; Madeleine Y. Hsu, Dreaming of Gold: Transnationalism and Migration Between the United States and South China, 1882–1943 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2000), 47–8.

39 ‘The Famine in China’, The Argus, 21 May 1878, 6, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/5933173/249934.

40 Ibid.

41 China Famine Relief Fund collected by Kong Meng and C.H. Cheong, Chinese Famine Fund, PROV, VPRS 3182.

42 Chinese letter, 1878, Chinese Famine Fund, VPRS 3182.

43 ‘Law Report’, The Argus, 2 March 1877, 10, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/5915219/247386.

44 Chinese letter, Chinese Famine Fund, PROV, VPRS 3182.

45 Sinn, ‘Practicing Charity’, 24.

46 Ibid., 24–25.

47 Ibid.; Peterson, ‘From Culturalism to Nationalism’, 92, 98.

48 Smith, ‘Social Hierarchy’, 421; Peterson, ‘From Culturalism to Nationalism’, 88.

49 Shue, ‘The Quality of Mercy’, 425–7; Edgerton-Tarpley, Tears from Iron, 133–4; Rogaski, ‘Beyond Benevolence’, 81.

50 Smith, ‘Social Hierarchy’, 418; Nanny Kim, ‘River Control, Merchant Philanthropy, and Environmental Change in Nineteenth-Century China’, Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 52, no. 4 (2009): 660–94.

51 Peterson, ‘From Culturalism to Nationalism’, 94.

52 Ching-huang Yen (颜清湟), Studies in Modern Overseas Chinese History (Singapore: Times Academic Press, 1995), 165–66; Peterson, ‘From Culturalism to Nationalism’, 94.

53 ‘Tablet Bearing Inscription Shen Wei Pu You’, Multi-media historical and cultural heritage repository, Hong Kong Memory, accessed 9 July 2023, https://www.hkmemory.hk/MHK/collections/TWGHs/All_Items/images/202003/t20200306_94130.html?cf=classinfo&cp=%E7%89%8C%E5%8C%BE&ep=Tablets&path=/MHK/collections/TWGHs/All_Items/10266/10278/10281/index.html.

54 Kuo, Making Chinese Australia, 66–79.

55 Edgerton-Tarpley, Tears from Iron, 133–4.

56 Macgregor, ‘Chinese Political Values’, 120–2; ‘The Chinese in Victoria’, The Herald, 17 August 1863, 4, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/244289465/26563893.

57 Mount Alexander Mail, 14 April 1864, 2; The Argus, 17 September 1861, 8.

58 ‘The Chinese in Victoria’, The Herald, 17 August 1863, 4, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/244289465/26563893; ‘The News of the Day’, The Age, 24 December 1867, 4, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/185503431/18283474.

59 ‘Mr Lowe Kong Meng’, The Australian News for Home Readers, 20 September 1866, 4, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/63171144/6163430.

60 Paul MacGregor, ‘Lowe Kong Meng and the fluidity of nineteenth century geopolitical affinity’, in Colonialism, China and the Chinese, ed. Peter Monteath and Matthew Fitzpatrick (London: Routledge, 2019), 218–19.

61 Smith, ‘Social Hierarchy’, 421.

62 ‘Acclimatisation’, The Argus, 20 May 1861, 5, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/5700340/203774.

63 Rule, ‘Chinese Engagement’, 138–53; Rasmussen, ‘Networks and Negotiations’, 82.

64 ‘Law Report’, The Argus, 2 March 1877, 10, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/5915219/247386.

65 Ley Kum v Edward Wilson Lauchlan Makinson, 1877, Supreme Court of Victoria Civil Case Files, PROV, VPRS 267.

66 Joanna Handlin Smith, The Art of Doing Good: Charity in Late Ming China (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), 3–6.

67 Mei-fen Kuo, ‘Confucian Heritage, Public Narratives and Community Politics of Chinese Australians at the Beginning of the 20th Century’, in Chinese Australians: Politics, Engagement and Resistance, ed. Sophie Couchman and Kate Bagnall (Leiden: Brill, 2015), 137–73.

68 Lowe Kong Meng, Cheok Hong Cheong, and Louis Ah Muoy, eds., The Chinese Question in Australia 1878–79 (Melbourne: F. F. Bailliere, 1879), 10–30; Fitzgerald, Big White Lie, 111; Marilyn Lake, ‘The Chinese Empire Encounters the British Empire and Its “Colonial Dependencies”: Melbourne, 1887’, Journal of Chinese Overseas 9, no. 2 (2013): 178–80.

69 Rasmussen, ‘Networks and Negotiations’, 83; Rule, ‘Chinese Engagement’, 142–7.

70 Edgerton-Tarpley, Tears from Iron, 131–55.

71 See for instance, ‘Arrival of the English Mail. General Summary’, The Argus, 20 April 1878, 5, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/5929494/249370.

72 Various subscription letters, China Famine Fund, PROV, VPRS 3182.

73 ‘Saturday, August 24, 1878’, The Argus, 24 August 1878, 7, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/5945613/251444; Untitled, Weekly Times, 22 June 1878, 18, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/page/23353422; Jacob, Religious Vitality, 227–78.

74 Meeting minutes, 17 June–November 1878, China Famine Fund, PROV, VPRS 3182.

75 Sinn, ‘Emerging Media’, 432–3; Wagner, ‘The Early Chinese Newspapers’, 1–33.

76 Edgerton-Tarpley, Tears from Iron, 142–55.

77 Ibid., 131–55; Rogaski, ‘Beyond Benevolence’, 82.

78 Kuo, Making Chinese Australia, 53; Mei-fen Kuo, ‘Jinxin: The Remittance Trade and Enterprising Chinese Australians, 1850–1916’, in The Qiaopi Trade and Transnational Networks in the Chinese Diaspora, ed. Gregor Benton, Hong Liu, and Huimei Zhang (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2018), 160–78.

79 The Argus, 20 August 1878, 7.

80 Kuo, Making Chinese Australia, 53.

81 Ibid., 11–12.

82 China Famine Relief Fund collected by Kong Meng and C H Cheong, Chinese Famine Fund, PROV, VPRS 3182.

83 Ong (王光輝), ‘Fundraising and Patriotism’, 2; Tung Wah Hospital, ‘Zhengxinlu (Annual Report) of Tung Wah Hospital, 1877’ (Tung Wah Museum, 1877), Tung Wah Museum Archives Catalogue, http://www.twmarchives.hk/zhengxinlu_detail.php?uid=16&sid=1&contentlang=tc&lang=en.

84 Minute book June–November 1878, Chinese Famine Fund, VPRS 3182.

85 Macgregor, ‘Chinese Political Values’, 143; see also ‘In Days of Old’, The Sun, 12 May 1918, 5, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/221942879/24411600.

86 Rasmussen, ‘Networks and Negotiations’, 79–92; Rule, ‘Chinese Engagement’, 142–51; Pauline Rule, ‘The Transformative Effect of Australian Experience on the Life of Ho A Mei, Hong Kong Community Leader and Entrepreneur’, in Chinese Australians: Politics, Engagement and Resistance, ed. Sophie Couchman and Kate Bagnall (Leiden: Brill, 2015), 22–52.

87 Rasmussen, ‘Networks and Negotiations’, 82; Rule, ‘Chinese Engagement’, 142–51.

88 Macgregor, ‘Chinese Political Values’, 160.

89 ‘The Chinese Famine’, Kyneton Guardian, 22 May 1878, 2, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/233332176/25147279.

90 Captain H. Morin Humphreys, Men of the Time in Australia, Victorian Series, Second Edition (Melbourne, M’Carron, Bird & Co., Printers and Publishers: 1882), 190.

91 Ibid.; ‘News of the Day’, The Age, 7 June 1864, 4, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/155013355/18274413; Jill Eastwood, ‘Smith, Alexander Kennedy (1824–1881)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography (ADB), National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/smith-alexander-kennedy-4597/text7557, published first in hardcopy 1976, accessed online 24 October 2022.

92 ‘The Mayor of Melbourne’s Fancy Dress Ball’, Maryborough and Dunolly Advertiser, 2 September 1863, 2, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/253525330.

93 Advertisement, The Argus, 15 June 1878, 12, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/5936451/250349.

94 ‘Law Report’, The Argus, 2 March 1877, 10, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/5915219/247386.

95 Minute meetings, June–November 1878, Chinese Famine Fund, PROV, VPRS 3182; Peter Cook, ‘Robert Harper (1842–1919)’, ADB, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/harper-robert-6572/text11305, accessed 1 January 2023; J. Ann Hone, ‘Sir James MacBain (1828–1892)’, ADB, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/macbain-sir-james-4063/text6477, accessed 1 January 2023.

96 Advertisement, The Argus, 15 June 1878, 12, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/page/250349.

97 The Herald, 17 August 1863, 4; Nicholas Guoth and Paul MacGregor, ‘Getting Chinese Gold Off the Victorian Goldfields’, Southern Chinese Diaspora Studies 8 (2019): 129–50; Benjamin Mountford, Britain, China, and Colonial Australia (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), 71.

98 Report of the Board appointed to consider the claims of certain Chinese in the Buckland District to compensation, together with the evidence taken before the Board, 28 April 1858, VA 2585 Legislative Assembly, PROV, VPRS 3253.

99 G. Oddie, ‘The Lower Class Chinese and the Merchant Elite in Victoria, 1870–1890’, Historical Studies: Australia and New Zealand 10, no. 37 (1961): 65–70; Alistair Bowen, ‘The Merchants: Chinese Social Organisation in Colonial Australia’, Australian Historical Studies 42, no. 1 (2011): 25–44; Macgregor, ‘Chinese Political Values’, 140–3; Sascha Auerbach, ‘Margaret Tart, Lao She, and the Opium-Master’s Wife: Race and Class among Chinese Commercial Immigrants in London and Australia, 1866–1929’, Comparative Studies in Society and History 55, no. 1 (2013): 44–52; Natalie Fong, ‘The Significance of the Northern Territory in the Formulation of “White Australia” Policies, 1880–1901’, Australian Historical Studies 49, no. 4 (2018): 533–7; Kevin Rains, ‘Doing Business: Chinese and European Socioeconomic Relations in Early Cooktown’, International Journal of Historical Archaeology 17, no. 3 (2013): 520–45.

100 Welch, ‘Alien Son’, 23–73.

101 ‘Wesleyan Church: Rev. Moy Ling’, Southern Times, 19 May 1896, 3, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/157532400/18682416.

102 Howard Le Couteur, ‘Reverend George Soo Hoo Ten’, Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society 105, no. 2 (2019): 225–47; Davis, Late Victorian Holocausts, 77.

103 Auerbach, ‘Margaret Tart, Lao She, and the Opium-Master’s Wife’, 46.

104 Welch, ‘Alien Son’, 68–9; Meeting minutes, Chinese Famine Fund, PROV, VPRS 3182; Geelong Advertiser, 21 June 1878, 2.

105 ‘The Chinese Famine Fund’, The Argus, 27 June 1878, 7, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/5937828; Meeting minutes, 26 June, Chinese Famine Fund, PROV, VPRS 3182.

106 Meeting minutes, 21 June 1878, Chinese Famine Fund, PROV, VPRS 3182.

107 ‘The Famine in China’ Circular, 24 June 1878, Chinese Famine Fund, PROV, VPRS 3182.

108 Ibid.

109 Davis, Late Victorian Holocaust, 77–8; Twomey and May, ‘Australian Responses’, 233; Sasson, ‘From Empire to Humanity’, 104.

110 Memorandum from John F. Paten, ‘Avoca Mail’ Office, to the Mayor of Melbourne, 19 July 1878, Chinese Famine Fund, PROV, VPRS 3182.

111 The Argus, 8 June 1878, 7; Article cut-out in minute book, Chinese Famine Fund, PROV, VPRS 3182.

112 Letter from Arthur Davenport to John Pigdon, 30 July 1878, Chinese Famine Fund, VPRS 3182.

113 ‘Arrival of the English Mail. General Summary’, The Argus, 20 April 1878, 5, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/5929494/249370; ‘The Suez Mail’, The Ballarat Courier, 22 April 1878, 4, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/211540532/22745835.

114 Committee, The Great Famine, 82.

115 Ibid., 83.

116 Twomey and May, ‘Australian Responses’, 238, 250.

117 Ibid., 248; James MacBain, Committee meeting minutes, 17 June 1878, Chinese Famine Relief Fund, PROV, VPRS 3182.

118 Individual contributions were substantially larger, school headmasters were involved, Department officers were asked for ‘voluntary’ contributions, and the file contains four boxes. See Charity and Relief Indian Famine, PROV, VPRS 3182, Box 6.

119 Committee, Final Report, 29–30.

120 China Famine Relief Fund, Shanghai Committee, The Great Famine: Report, 29.

121 MacBain, Committee meeting minutes, 17 June 1878, China Famine Fund, PROV, VPRS 3182.

122 ‘Chinese Famine Fund’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 29 May 1878, 8, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/page/1434261; ‘Chinese Famine Fund’, 30 May 1878, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/page/1434269; ‘The Chinese Famine Fund’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 31 May 1878, 8, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/page/1434277; ‘Chinese Famine Fund’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 6 June, 1, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/page/1434320.

123 ‘The Chinese Famine Fund’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 7 June 1878, 2, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/page/1434331.

124 Kuo, Making Chinese Australia, 53.

125 ‘South Australia’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 22 August 1878, 5, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/13411211/1432755.

126 ‘The Chinese Famine’, South Australian Register, 21 May 1878, 6, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/42991642/4005326.

127 ‘The Famine in China’, Adelaide Observer, 1 June 1878, 12, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/159442417/18906568.

128 ‘Floods in China’, The Australian Star, 6 June 1888, 6, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/229937584/24929990; Michael Williams and Shen Yuexiu, ‘Benevolence Returns from across the Seas’, History SA, no. 273 (2023): 9–10.

129 Geoffrey A. Oddie, ‘The Chinese in Victoria, 1870–1890’ (MA thesis, University of Melbourne, 1959), 40–3.

130 Kong Meng et al., The Chinese Question, 3–7.

131 ‘The Chinese Question’, The Argus, 9 January 1879, 6, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/5927710/251409.