Abstract

Context

Since recovery or death is generally observed within a few days after intensive care unit (ICU) admission of self-poisoned patients in the developed countries, reasons for the prolonged ICU stay are of interest as they have been poorly investigated. We aimed to identify the characteristics, risk factors, outcome, and predictors of death in self-poisoned patients requiring prolonged ICU management.

Methods

We conducted an eight-year single-center cohort study including all self-poisoned patients who stayed at least seven days in the ICU. Patients admitted with drug adverse events and chronic overdoses were excluded. Using multivariate analyses, we investigated risk factors for prolonged ICU stay in comparison with a group of similar size of self-poisoned patients with <7day-ICU stay and studied risk factors for death.

Results

Among 2,963 poisoned patients admitted in the ICU during the study period, the number who stayed beyond seven days was small (398/2,963, 13.1%), including 239 self-poisoned patients (125 F/114M; age, 51 years [38–65] (median [25th-75th percentiles]); SAPSII, 56 [43–69]). Involved toxicants included psychotropic drugs (59%), cardiotoxicants (31%), opioids (15%) and street drugs (13%). When compared with patients who stayed <7days in the ICU, acute kidney injury (odds ratio (OR), 3.15; 95% confidence interval (1.36–7.39); p = .008), multiorgan failure (OR, 8.06 (3.43–19.9); p < .001), aspiration pneumonia (OR, 8.48 (4.28–17.3); p < .001), and delayed awakening related to the persistent toxicant effects, hypoxic encephalopathy and/or oversedation (OR, 8.64 (2.58–40.7); p = .002) were independently associated with prolonged ICU stay. In-hospital mortality rate was 9%. Cardiac arrest occurring in the prehospital setting and during the first hours of ICU management (OR, 27.31 (8.99–158.76); p < .001) and delayed awakening (OR, 14.94 (6.27–117.44); p < .001) were independently associated with increased risk of death, whereas exposure to psychotropic drugs (OR, 0.08 (0.02–0.36); p = .002) was independently associated with reduced risk of death.

Conclusion

Self-poisoned patients with prolonged ICU stay of ≥7days are characterized by concerning high rates of morbidities and poisoning-attributed complications. Acute kidney injury, multiorgan failure, aspiration pneumonia, and delayed awakening are associated with ICU stay prolongation. Cardiac arrest occurrence and delayed awakening are predictive of death. Further studies should focus on the role of early goal-directed therapy and patient-targeted sedation in reducing ICU length of stay among self-poisoned patients.

Introduction

Self-poisoning is a common cause of intensive care unit (ICU) admission, representing 2–20% of all admissions [Citation1–4]. Self-poisoned patients generally present fewer comorbidities and less marked severity on admission than patients admitted with other conditions [Citation5,Citation6]. Toxicants involved in self-poisonings requiring ICU admission in developed countries mainly include pharmaceuticals and street drugs but rarely chemicals and natural toxins, by contrast to developing countries [Citation7,Citation8]. To help clinicians in charge, scores and risk prediction nomograms have been developed allowing prediction of the need for ICU admission after exposure [Citation9–10]. Well managed, ICU mortality is therefore relatively low (1–6%) in poisoned patients [Citation1–8] by comparison to overall ICU mortality, although varying according to the type of ICU and patients and estimated at ∼16% (95% confidence interval, 15.5–16.9) based on an international audit of ICU patients worldwide [Citation11] and ∼19% based on a European multinational observational study [Citation6].

In the developed countries, mean length of ICU stay for poisoned patients is short, i.e., 0.5–1.5 days (mean 1.3 days) [Citation4,Citation5]. However, different factors contribute to prolonging ICU stay including exposure to chemicals, ethanol co-ingestion, poisoning in the elderly (≥65 years), elevated ICU physiological scores on admission, occurrence of aspiration pneumonia, rhabdomyolysis, thrombocytopenia and organ failure (e.g., kidney, cardiovascular and respiratory failure) [Citation4,Citation12–15]. The exact reasons for ICU stay prolongation and its resulting outcome have been poorly investigated. Therefore, believing that self-poisoned patients requiring an ICU stay of seven days or more may correspond to a very particular patient subgroup, we aimed to investigate their characteristics, outcomes and risk factors for prolonged ICU stay and in-hospital death.

Patients and methods

Study design

We conducted a single-center cohort study including all successive self-poisoned adults who stayed for seven days or more in our ICU between November 2013 and May 2021. The study was conducted according to the Helsinki principles, declared and approved by our institutional review board. Patients were informed and invited to express their opposition to the use of their anonymized data if desired, but written consent was waived due to the retrospective and non-interventional methodology of the study.

Patients admitted in relation to drug-related adverse events and accidental overdoses were not included. Noteworthy, such patients have been shown to be older, more severely intoxicated on admission and with a higher mortality rate in comparison to self-poisoned patients [Citation16].

Poisoned patients were managed according to standards of care [Citation17]. Physicians in charge decided if gastrointestinal decontamination using single- or repeated-dose activated charcoal or gastric lavage should be performed and which antidote to administer and at any time.

Data were collected from the patient records and laboratory databases. Systematic blood and urinary toxicological screening was performed on a routine basis and, if relevant, drug quantifications were obtained using specific techniques. Street drugs included cocaine, amphetamines, gamma-hydroxybutyrate, heroin, ketamine, synthetic cathinones, poppers, and cannabis. The Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS) II was calculated on admission [Citation18]. Delayed awakening was defined as a lack of response to simple orders 48 h after sedative drug cessation or after ICU admission if the patient was not sedated [Citation19]. Available medical, laboratory, toxicological, electroencephalography and brain imaging data were reviewed to determine the exact reasons for such delayed arousal. Organ dysfunction/failure was described based on the Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score [Citation20]. Multiorgan failure was defined by the presence of at least two organ failures.

To identify risk factors for prolonged ICU stay, we selected a control group of equivalent size among self-poisoned patients with short ICU stay (<7 days) during the same period. For each self-poisoned patient with ≥7day-ICU stay (“i”), we selected the “i + 1” self-poisoned patient with <7day-ICU stay admitted to our ICU. If the “i + 1” self-poisoned patient had an ICU stay of ≥7days (thus already included in the study), the “i + 2” self-poisoned patient with <7day-ICU stay was considered. Consistent with the study group, patients admitted in relation to drug-related adverse events and accidental overdoses were not included in the control group.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as median [25th-75th percentiles] and percentages as appropriate. Categorical variables were compared using Fisher’s exact tests. Quantitative variables were compared using Mann-Whitney tests. Parameters significantly associated with ICU stay of ≥7days or death (with p < .05) based on univariate analyses were introduced into a multivariable stepwise logistic regression to identify those independently associated with prolonged ICU stay or in-hospital mortality, respectively. The threshold used for identifying factors to be included in the multivariate analysis was the best compromise between preservation of the statistical power and the possible risk of non-inclusion of a pertinent variable. Multicollinearity was tested and ruled out between all variables included in the multivariable analysis by checking that variable inflation factors were <5. Results are expressed as odds ratios (95% confidence intervals). Statistical analysis was performed using R statistical software version 3.6.3. Bilateral p values <.05 were considered as significant.

Results

Patient description

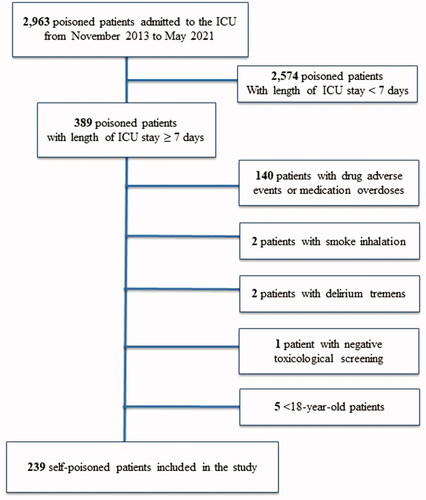

Among the 2,963 poisoned patients admitted to our ICU during the study period, 389 (13%) remained in the ICU for seven days or more. Patients admitted in relation to drug-related adverse effects or accidental overdoses (n = 140), alcohol withdrawal (n = 2), smoke inhalation (n = 2), uncertain poisoning with negative toxicological screening (n = 1) and patients under 18 year-old (n = 5) were not included. Therefore, 239 self-poisoned patients (61%; 125 F (52%)/114 M (48%); age, 51 years [38–65]; SAPSII, 56 [43–69]) were included in the study (). They were compared to a control group of 239 self-poisoned patients with <7day-ICU stay ().

Table 1. Comparisons between self-poisoned patients with ICU stay of more and less than seven days.

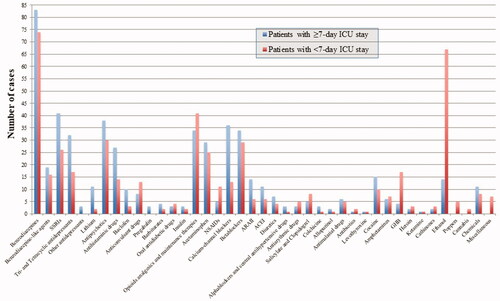

Patients who remained in the ICU for seven days or more were admitted from pre-hospital emergency services (n = 167, 70%), emergency departments (n = 51, 21%), other ICUs (n = 20, 8%) and psychiatric wards (n = 1, 0.4%). They had a history of psychiatric disorders (n = 170, 71%), suicidal attempt (n = 94, 39%), drug/ethanol addiction (n = 65, 27%), cardiac (n = 87, 36%), respiratory (n = 31, 13%), neurological (n = 35, 15%) and/or renal diseases (n = 7, 3%) (). Half the patients presented a multidrug exposure (n = 134, 56%). Involved toxicants included psychotropic drugs (n = 141, 59%), cardiotoxicants (n = 74, 31%), opioid analgesics and maintenance treatments (n = 34, 14%), street drugs (n = 32, 13%), ethanol (n = 14, 6%) and/or chemicals (n = 11, 5%) (). The delay between exposure and first medical rescue was distributed as follows: <6 h (26%), 6–12 h (22%), 12–24 h (27%), 24–48 h (7%), and >48 h (2%). It remained unknown in 16% of the patients found comatose on the scene with no bystander.

Figure 2. Drugs involved in self-poisoned patients with prolonged ICU stay of ≥7 days (n = 23) and shorter ICU stay of <7 days (n = 23). ACEI, angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; GHB, gamma-hydroxybutyrate; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug. Street drugs included the followings: cocaine, amphetamines, GHB, heroin, ketamine, synthetic cathinones, poppers, and cannabis.

Table 2. Characteristics of 239 self-poisoned patients with prolonged ICU stay of more than seven days.

Complications in the ICU

Complications consisted of aspiration pneumonia (n = 201, 84%), cardiovascular failure (n = 144, 60%), acute kidney injury (n = 136, 57%), acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS; n = 47, 20%), and/or cardiac arrest (n = 37, 15%). Cardiac arrests occurred in the prehospital setting (n = 24, 65%) and/or after ICU admission (n = 13, 35%), mainly during the first hours (n = 11) and rarely later (n = 2). Multiorgan failure was present in 181 patients (76%).

At least one electroencephalogram and/or brain imaging (computed tomography-scan or magnetic resonance imaging) were obtained in 182 (76%) and 109 patients (46%), respectively. Delayed awakening (n = 62, 26%) was attributed to direct sedative effects of the involved toxicants (n = 27, 44%), encephalopathy in relation to a hypoxic event or insufficient blood flow (n = 21, 34%), oversedation (n = 7, 11%), stroke or intracranial hemorrhage occurrence (n = 6, 10%) and/or metabolic impairments (n = 1, 2%). Encephalopathy responsible for confusion and/or agitation without consciousness impairment and attributed to the involved toxicants was observed in 31 patients (13%). Withdrawal syndrome in chronic alcoholics, drug users and psychoactive drug-depending patients was reported in 19 patients (8%).

Management and outcome

Management included mechanical ventilation (n = 198, 83%; with tracheal intubation on the scene (78%) versus in the ICU (22%); duration, seven days [Citation4–10]), sedation (n = 189, 79%; duration, three days [Citation1–6]), catecholamine infusion (n = 149, 62%; duration, two days [Citation1–4]), and antidote administration (n = 133, 56%; Supplemental material, Table1S). Renal replacement therapy (n = 49, 21%) was necessary to treat acute kidney injury (n = 44) and enhance lithium (n = 4, 8%) and metformin elimination (n = 1, 2%). Thirty-seven patients (15%) required veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) to manage refractory drug-induced cardiac failure or arrest. Overall, length of ICU stay was 12 days [Citation8–18]. ICU survivors were discharged to the medical (n = 116, 49%), psychiatric (n = 72, 30%), or rehabilitation wards (n = 11, 5%) or directly home (n = 18, 8%). Withdrawal care in relation to severe irreversible post-anoxic encephalopathy was decided in 10 patients. Overall, twenty-two patients (9%) died in the hospital.

Subgroup characteristics

Street drug-overdosed patients (n = 32) were mostly males (n = 27, 84%), aged of 36 years [27–44], developed more seizures (25% versus 11%, p = .04), ARDS (44% versus 16%, p < .001), and cardiac arrest (41% versus 12%, p < .001) in comparison to other patients. Psychotropic drug-poisoned patients were mostly females (n = 86, 61%), experienced fewer seizures (9% versus 18%, p = .02), less cardiac (23% versus 45%, p < .001), renal (48% versus 69%, p = .001) and multiorgan failure (70% versus 85%, p = .007), and presented less cardiac arrest (11% versus 21%, p = .03) but developed more critical illness myopathy (10% versus 3%, p = .04) in comparison to other patients. Almost all ECMO-treated patients developed multiple organ failure with acute kidney injury (76%), liver failure (32%), ARDS (27%) and thrombocytopenia (16%) in addition to cardiovascular failure, which required ECMO implementation. They presented aspiration pneumonia (95%), seizures (24%), and critical-illness neuromyopathy (11%). In-hospital mortality rate was 19% (7/37 patients) in this subgroup.

Risk factors for prolonged ICU stay

We compared our cohort of 239 self-poisoned patients with ≥7day-ICU stay to a control group of 239 self-poisoned patients with <7 day-ICU stay (). A significantly higher proportion of patients with self-poisoning with psychotropic agents (59% versus 48%, p = .01) and cardiotoxicants (31% versus 21%, p = .005) and those with multi-drug exposure (56% versus 41%, p = .001) had prolonged ICU stay when compared with those who stayed less than seven days. On the other hand, a significantly higher proportion of patients who presented with ethanol overdose (6% versus 28%, p < .001) stayed for less than seven days (). Differences in the administered antidotes are presented in the Supplemental material, Table1S. Noteworthy, there was no significant difference in in-hospital mortality between patients with <7day- and ≥7day-ICU stay (5% versus 9%, p = .1).

Based on a multivariate analysis, acute kidney injury (OR, 3.15 (1.36–7.39); p = .008), multiorgan failure (OR, 8.06 (3.43–19.9); p < .001), aspiration pneumonia (OR, 8.48 (4.28–17.3); p < .001), and delayed awakening (OR, 8.64 (2.58–40.7); p = .002) were independently associated with prolonged ICU stay of ≥7days, whereas cardiac arrest (OR, 0.15 (0.04–0.52); p = .003) and ethanol ingestion (OR, 0.28 (0.11–0.66); p = .005) were independently associated with <7day-ICU stay (). Medical conditions susceptible to have contributed to the prolonged ICU stay in our patients are presented in Supplemental material, Figure1S.

Table 3. Risk factors for prolonged ICU stay in self-poisoned patients based on a multivariate analysis.

Risk factors of death

Based on univariate analyses, parameters on ICU admission associated with in-hospital mortality included history of addiction (p = .04), acute exposure to street drugs (p = .004), higher heart rate (p = .04) and requirement of tracheal intubation (p = .02) and catecholamine infusion (p = .003) (). Severity of complications including cardiac arrest (p < .001), mechanical ventilation (p = .02), catecholamine infusion (p = .003), ARDS (p = .003), acute kidney injury (p = .04), cardiovascular (p = .01) and liver failure (p = .03) were more frequent in non-survivors than survivors. Neurological complications including delayed awakening (p < .001), status epilepticus (p = .001) and seizure occurrence (p = .01) were also associated with death. By contrast, overdose involving psychotropic drugs (p < .001) and more specifically benzodiazepines (p = .03) was associated with survival.

Based on a multivariate analysis, cardiac arrest occurrence at any stage of the poisoning (OR, 27.31 (8.99–158.76); p < .001) and delayed awakening (OR, 14.94 (6.27–117.44); p < .001) were independently associated with in-hospital mortality whereas psychotropic drug exposure was independently associated with survival (OR, 0.08 (0.015–0.36); p = .002) (Supplemental material, Figure2S). Parameters associated with in-hospital death in patients with <7day-ICU stay are presented in the Supplemental material, Table2S.

Discussion

Our study focused on critically ill self-poisoned patients with prolonged ICU stay of seven days or more. ICU stay prolongation was mainly attributed to the occurrence of poisoning-attributed organ complications and delayed awakening. Our most important finding was that delayed awakening and occurrence of cardiac arrest mainly in the first hours of poisoning management represented independent predictive factors of in-hospital death while involvement of psychotropic drugs as toxicants was protective.

Characteristics of our patient population were consistent with other studies reporting ICU poisoned patients [Citation1,Citation2,Citation4–7]. However, as expected, in-hospital mortality rate (9%) in this selected cohort with prolonged ICU stay was elevated in comparison to other ICU poisoned patient cohorts, possibly also in relation to higher prevalence of cardiac morbidities, exposures to cardiotoxicants and drug-induced cardiovascular failure that can be attributed to the specificities of our department.

A proportion of patients poisoned with common toxicants such as benzodiazepines, antidepressants, ethanol and opioid stayed in the ICU for a prolonged time, suggesting that complications during the overdose even with drugs that should wear off quickly may have resulted in prolonged stay rather than the toxin per se. By comparing ≥ seven-day- versus <seven-day-ICU stay patients, we showed that aspiration pneumonia, acute kidney injury, and multiorgan failure are risk factors for prolonged ICU stay, as previously reported [Citation4,Citation13,Citation14]. By contrast, cardiac arrest patients had shorter ICU stay. Although it appears paradoxical that patients who were sickest stayed for a shorter period, it is likely that the nature of the illness probably allowed earlier withdrawal of active treatment. By definition, patients with a high risk of early mortality had a reduced chance of surviving to stay in the ICU for ≥7 days. Interestingly, based on SAPS II scores, prolonged ICU stay patients were more severe on admission than short ICU stay patients were. Here we identified delayed awakening as additional risk factor. Contrasting with a previous finding [Citation14], we showed that ethanol intoxication was also associated with shorter ICU stay.

In the critically ill self-poisoned patient, delayed awakening is a frequent reason for prolonged ICU stay and an independent risk factor for in-hospital mortality, as previously demonstrated [Citation19]. Delayed awakening is either a component of coma or delirium, defined as a persistent disorder of arousal or consciousness 48 to 72 h after sedation interruption in critically ill patients. In the context of self-poisoned patients, it may be related to the prolonged pharmacological effects of self-ingested toxicants (i.e., presence of extremely high concentrations, prolonged half-life, and/or delayed clearance), or to post-anoxic encephalopathy resulting from cardiac arrest, prolonged pre-hospital hypoxemia and/or brain hypoperfusion. Rarely, delayed awakening is caused by oversedation or cerebrovascular events. Agitation, delirium and pain management and monitoring is therefore crucial in the critically ill poisoned patient, as routinely practiced in all ICU patients [Citation21,Citation22]. Although we almost systematically used propofol as first-line sedation in our ICU, the type and dose regimen of the chosen sedative drugs can highly influence the arousal time and should be adapted to the patient’s kidney and liver functions. Sedative drugs should also be administered at the minimally effective dose, especially in the elderly, to allow optimal care and mechanical ventilation and avoid oversedation [Citation23]. ICU nurses are advised to apply the ABCDE bundle including awakening and breathing coordination, delirium monitoring/management, and early mobility in the poisoned patients to limit complications and shorten ICU stay [Citation24]. Brain imaging, repeated electroencephalograms and/or monitoring of the plasma concentrations of involved toxicants and ICU sedative drugs are useful to clarify the reasons for delayed awakening, as shown in several animal models [Citation25,Citation26].

Cardiac arrest is another major factor associated with in-hospital mortality in self-poisoned patients. As shown in our series, it usually occurs early in the poisoning time-course and thus contributes to shorten hospital stay. However, if successfully resuscitated, it may be responsible for subsequent morbidities including cardiovascular failure and anoxic encephalopathy both contributing to prolong ICU stay. Self-poisoned patient management, especially in the pre-hospital setting, should aim at minimizing the risk of cardiac arrest. Of self-intoxicated patients with cardiac arrest who survived to discharge, a previous study showed no difference in the likelihood of favorable neurological recovery whether cardiac arrest was related or not to drug overdose [Citation27].

We observed a statistical association based on univariate analysis between street drug overdose and death, possibly resulting from increased prevalence of cardiac arrest if successfully resuscitated that led to post-anoxic encephalopathy. Due to the risks of life-threatening cardiac complications [Citation28,Citation29], street drug overdoses, especially those related to cocaine and amphetamines, require immediate care and close monitoring, starting from the prehospital setting. By contrast, admission in relation to psychotropic drug exposure, at lower risk of cardiovascular complications and organ failure, was associated with reduced mortality risk.

Our study has limitations. Our analysis may be underpowered, but our cohort, specifically dedicated to self-poisoned patients with prolonged ICU stay, is relatively large. The cohort is heterogeneous but reflects the real life situation in most ICUs. Organ failure was almost due to non-drug-specific mechanisms including prolonged hypotension, hypoxemia or sepsis, although, due to our retrospective study design, we could not rule out that some cases were drug-induced. Although reasonable given the number of poisoned patients admitted to the ICU during the study period (n = 2963), the chosen method to select controls could have introduced biases. Finally, we acknowledge that accidental overdoses, which were excluded from our analysis may have been deliberate in some cases with patients stating it is accidental to avoid legal problems with deliberate self-harm. However, this issue was minimized by the fact that all poisoned patients have had a psychiatric consultation before ICU discharge to clarify the intentionality and suicidality of their exposure.

To conclude, acute kidney injury, multiorgan failure, aspiration pneumonia, and delayed awakening are risk factors for prolonged ICU stay in self-poisoned patients. Cardiac arrest and delayed awakening are independently associated with death in these patients, while psychotropic drug overdose is protective. Our study suggests that street drug-overdosed patients who have experienced cardiac complications resulting in prolonged ICU stay may be particularly at risk of fatal outcome. Further prospective multicenter studies should be performed to confirm our results.

Author contributions

Dr Mégarbane designed the study. All authors managed the patients in the intensve care unit. Dr. Naïm collected the data. Drs. Naïm and Lacoste-Palasset performed the statistical analysis. All authors participated in the critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (579.3 KB)Supplemental Material

Download Zip (551.4 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mrs. Alison Good (Scotland, UK) for her helpful review of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Prof. Mégarbane have full access to all data and takes responsibility for the data integrity and its analysis accuracy.

References

- Lindqvist E, Edman G, Hollenberg J, et al. Intensive care admissions due to poisoning. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2017;61(10):1296–1304.

- Athavale V, Green C, Lim KZ, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients with drug overdose requiring admission to intensive care unit. Australas Psychiatry. 2017;25(5):489–493.

- Beaune S, Juvin P, Beauchet A, et al. Deliberate drug poisonings admitted to an emergency department in Paris area - a descriptive study and assessment of risk factors for intensive care admission. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2016;20(6):1174–1179.

- Liisanantti JH, Ohtonen P, Kiviniemi O, et al. Risk factors for prolonged intensive care unit stay and hospital mortality in acute drug-poisoned patients: an evaluation of the physiologic and laboratory parameters on admission. J Crit Care. 2011;26(2):160–165.

- Brandenburg R, Brinkman S, de Keizer NF, et al. In-hospital mortality and long-term survival of patients with acute intoxication admitted to the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(6):1471–1479.

- Capuzzo M, Volta CA, Tassinati T, et al. Hospital mortality of adults admitted to intensive care units in hospitals with and without intermediate care units: a multicentre European cohort study. Crit Care. 2014;18(5):551.

- Socias Mir A, Nogué Xarau S, Alcaraz Peñarrocha RM, et al. Evolution of poisoned patients admitted to Spanish intensive care units: comparing two periods. Med Intensiva (Engl Ed). 2021;S2173-5727(21):00079–00075.

- Mehrpour O, Akbari A, Jahani F, et al. Epidemiological and clinical profiles of acute poisoning in patients admitted to the intensive care unit in Eastern Iran (2010 to 2017). BMC Emerg Med. 2018;18(1):30.

- El Gharbi F, El Bèze N, Jaffal K, et al. Does the ICU requirement score allow the poisoned patient to be safely managed without admission to the intensive care unit? - a validation cohort study. Clin Toxicol. 2022;60(3):298–303.

- Elgazzar FM, Afifi AM, Shama MAE, et al. Development of a risk prediction nomogram for disposition of acute toxic exposure patients to intensive care unit. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2021;129(3):256–267.

- Vincent JL, Marshall JC, Namendys-Silva SA, et al. ICON investigators. Assessment of the worldwide burden of critical illness: the intensive care over nations (ICON) audit. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2(5):380–386.

- Mühlberg W, Becher K, Heppner HJ, et al. Acute poisoning in old and very old patients: a longitudinal retrospective study of 5883 patients in a toxicological intensive care unit. Z Gerontol Geriatr. 2005;38(3):182–189.

- Christ A, Arranto CA, Schindler C, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and outcome of aspiration pneumonitis in ICU overdose patients. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32(9):1423–1427.

- Lam SM, Lau AC, Yan WW. Over 8 years experience on severe acute poisoning requiring intensive care in Hong Kong, China. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2010;29(9):757–765.

- O’Donovan FC, Owens J, Tracey JA. Self poisoning: admission to intensive care over a one year period. Ir Med J. 1993;86(2):64–65.

- Schwake L, Wollenschläger I, Stremmel W, et al. Adverse drug reactions and deliberate self-poisoning as cause of admission to the intensive care unit: a 1-year prospective observational cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35(2):266–274.

- Mégarbane B, Oberlin M, Alvarez JC, et al. Management of pharmaceutical and recreational drug poisoning. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10(1):157.

- Le Gall JR, Lemeshow S, Saulnier F. A new simplified acute physiology score (SAPS II) based on a European/North American multicenter study. JAMA. 1993;270(24):2957–2963.

- Bouchereau E, Sharshar T, Legouy C. Delayed awakening in neurocritical care. Rev Neurol. 2022;178(1-2):21–33.

- Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, et al. The SOFA (sepsis-related organ failure assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the working group on Sepsis-Related problems of the European society of intensive care medicine. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22(7):707–710.

- Barr J, Fraser GL, Puntillo K, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in adult patients in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(1):263–306.

- Shetty RM, Bellini A, Wijayatilake DS, et al. BIS monitoring versus clinical assessment for sedation in mechanically ventilated adults in the intensive care unit and its impact on clinical outcomes and resource utilization. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;2(2):CD011240.

- SRLF Trial Group. Impact of oversedation prevention in ventilated critically ill patients: a randomized trial-the AWARE study. Ann Intensive Care. 2018;8(1):93.

- Bardwell J, Brimmer S, Davis W. Implementing the ABCDE bundle, Critical-Care pain observation tool, and Richmond Agitation-Sedation scale to reduce ventilation time. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2020;31(1):16–21.

- Hanak AS, Malissin I, Poupon J, et al. Electroencephalographic patterns of lithium poisoning: a study of the effect/concentration relationships in the rat. Bipolar Disord. 2017;19(2):135–145.

- Chartier M, Malissin I, Tannous S, et al. Baclofen-induced encephalopathy in overdose - Modeling of the electroencephalographic effect/concentration relationships and contribution of tolerance in the rat. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018;86:131–139.

- Ormseth CH, Maciel CB, Zhou SE, et al. Differential outcomes following successful resuscitation in cardiac arrest due to drug overdose. Resuscitation. 2019;139:9–16.

- Grubb AF, Greene SJ, Fudim M, et al. Drugs of abuse and heart failure. J Card Fail. 2021;27(11):1260–1275.

- Hantson P. Mechanisms of toxic cardiomyopathy. Clin Toxicol. 2019;57(1):1–9.