ABSTRACT

Background: Parents have a significant role in supporting children who have been exposed to traumatic events. Little is known about parental experiences and needs in the wake of traumatic exposure, which could help in designing tailored early interventions.

Objective: This qualitative study explored experiences, perceived needs, and factors impacting those needs being met, in parents of adolescents aged 11–16 years who had been exposed in the past 3 months to a potentially traumatic event, in the city of Montpellier, France.

Method: We purposively sampled 34 parents of 25 adolescents aged 11–16 years meeting the inclusion criteria and used semi-structured in-depth interviews. Thematic analysis was applied using a multistage recursive coding process.

Results: Parents lacked trauma-informed explanations to make sense of their child’s reduced functioning. They experienced stigma attached to the victim label and were reluctant to seek help. School avoidance and lack of collaboration with schools were major obstacles experienced by parents. Parents trying to navigate conflicting needs fell into two distinct categories. Those who experienced distressing levels of shame and guilt tended to avoid discussing the traumatic event with their child, pressuring them to resume life as it was before, despite this perpetuating conflictual interactions. Others adapted by revisiting their beliefs that life should go on as it was before and by trying to come up with new functional routines, which improved their relationship with their child and helped them to restore a sense of agency and hope, but at the cost of questioning their parental role.

Conclusions: Key domains of parental experiences could provide potential early intervention targets, such as psychoeducation on traumatic stress, representations about recovery and the victim status, parent–child communication, and involvement of schools and primary caregivers. Further research is needed to validate the impact of these domains in early post-traumatic interventions.

HIGHLIGHTS

Parents of teenagers exposed to traumatic events struggle to understand trauma and feel isolated.

Parents feel pressured to resume life as it was before, leading to conflictual child–parent interaction.

Psychoeducation, stigma, and school involvement could be early intervention targets.

Antecedentes: Los padres tienen un rol significativo en apoyar a los niños expuestos a eventos traumáticos. Poco se sabe sobre las experiencias parentales y las necesidades al comienzo de una exposición traumática, las cuales podrían ayudar a diseñar intervenciones tempranas hechas a la medida.

Objetivo: Llevamos a cabo un estudio cualitativo explorando las experiencias, necesidades percibidas, y los factores que influyen en la satisfacción de esas necesidades, entre los padres de adolescentes de 11 a 16 años que habían estado expuestos a un evento potencialmente traumático en los últimos tres meses en la ciudad de Montpellier, Francia.

Método: De forma intencionada tomamos una muestra de 34 padres de 25 adolescentes de edades entre 11 y 16 años que cumplieron con el criterio y usamos entrevistas semi-estructuradas en profundidad. Se aplicó un análisis temático usando un proceso de codificación recursivo de múltiples etapas.

Resultados: Los padres carecieron de explicaciones informadas en el trauma para darle sentido al funcionamiento reducido de sus hijos. Ellos experimentaron estigma asociado a la etiqueta de victima y estaban reticentes a buscar ayuda. La evitación escolar y la carencia de colaboración con los colegios emergieron como los mayores obstáculos experimentados por los padres. Mientras tratan de navegar las necesidades conflictivas, los padres caen en dos categorías distintivas: aquellos que experimentan niveles preocupantes de vergüenza y culpa tendieron a evitar discutir el evento traumático con el hijo, presionándolos a retomar sus vidas como eran antes, aunque esto perpetuara las interacciones conflictivas. Otros se adaptaron al revisitar sus creencias que la vida debería continuar como era antes y tratando de crear nuevas rutinas funcionales, las cuales mejoraron su relación con sus hijos, y los ayudaron a restaurar un sentido de agencia y esperanza. Esto sin embargo vino con el costo de cuestionarse su rol parental.

Conclusión: Los dominios claves de las experiencias parentales podrían ser potenciales objetivos de intervención temprana, como psicoeducación en eventos traumáticos, las representaciones sobre la recuperación y el estatus de víctima, la comunicación padre e hijo, y el involucramiento de los colegios y cuidadores primarios. Se necesitan futuras investigaciones para validad el impacto de estos dominios en intervenciones post traumáticas tempranas.

1. Introduction

Children and adolescents worldwide are subject to alarmingly high rates of sexual abuse, physical assaults, violent accidents, and other potentially traumatic events (PTEs), such as war and displacement (Finkelhor et al., Citation2015; Lewis et al., Citation2019). Childhood traumatic exposure represents a menace to children’s development (Dye, Citation2018; Mueller & Tronick, Citation2019; Putnam, Citation2006), and is associated with increased risk for adult psychiatric, physical, and behavioural health, especially in the case of chronic and cumulative traumatic exposure in childhood (Anda et al., Citation2006; Green et al., Citation2010; McLaughlin et al., Citation2012).

In contrast, following exposure to a single traumatic event, there is evidence of spontaneous recovery for some (Berkowitz et al., Citation2011; Hiller et al., Citation2016). However, the rate of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) at 1 year following traumatic exposure among children aged 5–18 years is still substantial, with a prevalence of 11% (Hiller et al., Citation2016). It is well established that child and adolescent PTSD can negatively impact social, emotional, educational, and developmental outcomes (Alisic et al., Citation2008; Bellis & Zisk, Citation2014; Mathews et al., Citation2009). Moreover, while some children and adolescents may eventually recover spontaneously from their traumatic exposure, symptoms occurring in the acute phase, which can include intrusive thoughts, hyperarousal, irritability, fearfulness, sleep difficulties, and concentration problems, are important sources of immediate suffering for the child and family and can cause significant functional impairment and derail optimal development (Garfin et al., Citation2018; Stover et al., Citation2022; Zatzick et al., Citation2008).

It is therefore crucial to better understand individual and contextual factors that might alleviate early post-traumatic reactions and their negative impact, as well as facilitate post-traumatic recovery at an early stage following exposure, to design clinical interventions tailored to address these factors.

One recognized major protective factor facilitating recovery in the aftermath of traumatic experiences is social support (Ozer et al., Citation2003). More particularly, family support and caregiver–child relationship quality are significant factors contributing to children’s success in managing post-traumatic reactions (Cox et al., Citation2008; Trickey et al., Citation2012) and developing emotional self-regulation in response to adversity (Hahn et al., Citation2019; Kliewer et al., Citation2004). A meta-analytic review of the role of parenting behaviours in childhood post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) found that negative parenting (hostility, overprotection) was significantly associated with child PTSD (Williamson et al., Citation2017b). Moreover, involvement in (or reactions to) events that impact their children can traumatically affect caregivers themselves, which may in turn influence their ability to serve effectively in a caregiving role at a time when a child is particularly vulnerable (Rakovec-Felser & Vidovič, Citation2016). This emphasizes the importance of early interventions that strengthen parental capacities in the aftermath of children’s traumatic exposure (Kerns et al., Citation2014; Mooney et al., Citation2017). In a recent scoping review investigating early interventions to prevent PTSD in youth within 3 months of a PTE exposure, we found that interventions that yielded positive results on outcomes such as post-traumatic, anxiety, and depression symptoms involved parents as well as children, and combined psychoeducational content on trauma reactions with coping strategies to deal with PTSS through cognitive behavioural and relaxation techniques (Kerbage et al., Citation2022).

Although these early interventions focusing on strengthening individuals and families’ abilities to cope in the aftermath of trauma look promising, recent resilience research highlights the need to shift the focus from a symptomatology paradigm to exploring processes allowing children and parents to respond in an adaptive manner within their environmental settings, in line with a multisystemic and ecological framework of risk and resilience (Ellis & Dietz, Citation2017; Iacoviello & Charney, Citation2014). This implies understanding children’s and parents’ own perceptions and experiences of coping following traumatic exposure, and how they interact with their social milieu, including resources available in their ecological contexts and their interaction with their proximal environments in the family, school, and neighbourhood (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, Citation2007; Mooney et al., Citation2017). Exploring these experiences as well as perceived factors facilitating or preventing these adaptive processes is crucial to a successful implementation of early interventions to prevent post-traumatic psychopathology and increase adaptation in the face of adversity. Such knowledge is essential to inform a systemic approach that would consider environmental obstacles as well as resources, instead of only focusing on individual psychological attributes, and is mainly acquired through a qualitative design that allows the in-depth understanding of behavioural patterns, lived experiences, perceived needs, and subjective reactions, which may otherwise go unnoticed by close-ended questionnaires and quantitative measures (Renjith et al., Citation2021).

Qualitative data investigating the experiences, reactions, and perceived needs of parents while supporting their child in the wake of traumatic exposure are scarce. Available studies suggest that parents are usually actively supportive of their children and sensitive to their distress (Røkholt et al., Citation2016; Williamson et al., Citation2016). However, they struggle with structural obstacles such as lack of collaboration with schools and social isolation, as well as lack of access to adequate professional support (Røkholt et al., Citation2016; Williamson et al., Citation2017a). Furthermore, parents report having difficulties recognizing post-traumatic stress and struggle with conflicting demands, especially regarding the reinstatement of pre-trauma routines (Røkholt et al., Citation2016; Williamson et al., Citation2016). They express the need for peer support, experiential knowledge sharing, and professional support to understand and deal with their children’s reactions (Foster et al., Citation2017; Heath et al., Citation2018). Other qualitative studies reveal that parents feel uncertain about the best way to approach the subject of the traumatic event with their child, and tend to avoid trauma-related discussions, fearing that non-avoidant approaches may worsen the child’s post-traumatic symptoms (McGuire et al., Citation2019; Williamson et al., Citation2016, Citation2017a). In the case of a traumatic event involving child sexual abuse (CSA), available qualitative studies suggest that parents’ beliefs and stigma surrounding CSA shape their reactions and experiences following the child’s disclosure of sexual abuse and can promote the avoidance of trauma-related discussions (Alaggia et al., Citation2019; Simon et al., Citation2017). Clearly, these studies highlight important needs experienced by parents that can be targets for early interventions, such as structural obstacles and lack of perceived adequate professional support, problems identifying post-traumatic stress, and avoidance of trauma-related conversations. However, they also emphasize crucial gaps regarding how trauma shapes the family dynamic and parent–child relationships, along with the family adjustments needed in the wake of the traumatic exposure, which could be targeted through family interventions. Furthermore, little is known about the more complex representations and beliefs of parents regarding post-traumatic stress and adjustment, and how these representations impact their reactions, relationships with the child, and social roles following traumatic exposure. A conceptual model integrating all of these various psychological and socioecological aspects of parents’ lived experiences in the aftermath of trauma is lacking and could be best achieved by an in-depth qualitative exploration of all of these closely intertwined elements.

Adolescence is a critical developmental period characterized by marked psychological transformations in cognition, identity, self-consciousness, and relationships with others. One important facet underlying these changes is the maturation of the social and emotional brain (Blakemore, Citation2012). Traumatic exposure in adolescence can therefore interfere with this brain maturation, altering developmental acquisition of emotion regulation abilities, stable sense of self, identity, and cognitive flexibility. Further, adolescents’ needs for parental contact and comfort following traumatic exposure may contrast with their need for independence, leading to ambivalence and conflict regarding parental involvement (Lattanzi-Licht, Citation1996) and impacting family relationships (Alisic et al., Citation2008; Røkholt et al., Citation2016). This developmental period, however, also provides benefits and opportunities in terms of young people’s increased potential to communicate their needs and form trusting relationships. To our knowledge, few studies have explored the specific needs of teenagers’ parents, and no study has been conducted in Montpellier regarding the experiences and psychosocial needs of parents while supporting their adolescents in the aftermath of traumatic exposure.

This study aims to explore the experiences of parents of adolescents aged 11–16 years who had been exposed to a PTE in the past 3 months, and to identify early parental reactions to the child’s traumatic stress, changes in the family dynamic, and perceived factors that contribute to or impede their needs being met during the peritraumatic period.

2. Method

This study forms part of a multicentre study conducted in France and Lebanon investigating the experiences and needs of parents of adolescents aged 11–16 years who had been exposed to a PTE in the past 3 months. This article describes the qualitative findings from the site in the city of Montpellier, France. An interpretive qualitative approach was used to investigate parents’ subjective experiences and needs. This design is useful for understanding how people interpret and make meaning of their experiences, and is appropriate when little is known about a phenomenon (Merriam & Tisdell, Citation2009).

2.1. Participant recruitment

Data collection was carried out from December 2021 to July 2022 in Saint-Eloi University Hospital in Montpellier. Participants were recruited following purposive sampling targeting parents of adolescents aged between 11 and 16 years old had been were exposed to a PTE in the past 3 months. Exclusion criterion included suspicion of child neglect or abuse by one or both parents, suspicion of domestic violence, and a current severe parental mental health episode or the presence of suicidal ideations. Parents of children who were previously known by the principal investigator (PI) as their main child psychiatrist were excluded from the study. Participants needed to speak, read, and write French.

The definition of a PTE endorsed in our study was that of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), requiring ‘direct personal exposure, in person witnessing of trauma to others (and not solely through social media), and indirect exposure through trauma experience of a family member, to an event involving actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence’ (American Psychological Association, Citation2013). This definition excludes stressful events not involving an immediate threat to life or physical injury, such as psychosocial stressors (North et al., Citation2009), and non-immediate, non-catastrophic life-threatening illness, such as terminal cancer (APA, Citation2013). Examples of PTEs include physical and sexual violence or assault, community or school violence, serious accidents, natural disaster, terrorism, sudden or violent loss of a loved one, and refugee or war experiences.

Participant recruitment was carried out through the paediatric emergency department, and through child mental health professionals working at the clinics of the Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Department of Saint-Eloi University Hospital of Montpellier, whenever they encountered in their practice a recent traumatic exposure among their patients, whether as a chief complaint in an initial consultation or throughout the follow-up of a child for a different complaint. The emergency room (ER) staff and mental health professionals were previously briefed by the PI to screen for eligible parents and inform them about the aim and procedures of the study. Voluntary parents were subsequently contacted by the PI to gather consent and check for inclusion/exclusion criteria. This recruitment procedure was facilitated by the involvement of the Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Department and the paediatric ER Department in the regional network of paediatric health structures, along with weekly staff meetings to discuss suitability for enrolment and inclusion.

2.2. Study design

We used semi-structured in-depth interviews to capture subjective experiences, personal narratives, and meaning making (Hennink et al., Citation2011). The interview guide was developed and implemented using both a deductive and an inductive conceptual approach. The initial interview guide was designed deductively based upon existing literature on parental perceptions of the child’s trauma and coping, perceived change in parenting styles, and child–parent interactions following the child’s traumatic stress reactions, along with trauma-specific parental responses and perceived needs in the peritraumatic period (Cobham & McDermott, Citation2014; Foster et al., Citation2017; Gil-Rivas & Kilmer, Citation2013; Røkholt et al., Citation2016; Stallard et al., Citation2001). Questions were developed to explore the themes that have already been identified in the literature in consultation with academics and child mental health professionals, as detailed in Supplementary Material 1. Further revisions were made after each interview to refine the questions. The initial interview guide was piloted with a small group of participants (n = 5) and adjusted based on their feedback. The adjustments consisted of reformulating some questions, especially regarding the perception of risk and protective factors, to render them more open ended and less directive towards specific answers, to gather as much information as possible.

One semi-structured interview averaging 60–90 min in length was conducted with each participant. Participants were offered a face-to-face interview at the PI’s office in a calm setting or an online interview. The option of an online interview was suggested in case it would be more convenient for parents regarding their schedule and transportation logistics, as well as owing to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) sanitary restrictions. By the time of the study, the full lockdown had been lifted in France, but preventive measures were still mandatory, such as wearing masks and social distancing. Each participant was offered the option of a second interview, which consisted of a 20–30 min encounter to follow up on any impact that the first meeting might have had on their mental health, to allow a deeper exploration of their experience, and to gather feedback.

Although semi-structured, the interviews were open-ended in the style of questions to provide an understanding of the informants’ subjective experiences (Marvasti, Citation2010; Morse, Citation2012). Initially, the interviewer invited participants to share their experiences by asking the following opening question: ‘Can you tell me about your experience since your child has been exposed to the traumatic event?’, before seeking additional information by following the semi-structured interview guide. However, when participants broached interesting subjects, even if not mentioned in the interview guide, the interviewer allowed for the participant to determine the flow of information by probing more follow-up details, such as ‘Can you tell me more about this?’ and ‘How did you feel about that?’ (Johnson, Citation2001), or through keywords such as social support, coping, trauma, family support, and school support. All interviews were carried out in French by the PI. Interviews were audio-recorded with participants’ consent.

2.3. Ethics

Montpellier University Hospital Institutional Review Board granted ethical clearance for this study. All participants signed a written consent form. All data were made anonymous, and recordings were destroyed following analysis. Participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the study and cease the interview at any time. All participants were given contact details for follow-up emotional support if required. Respondents were also offered the opportunity to receive a summary of findings and discuss it with the PI.

During the initial meeting of consent gathering, the PI, a psychiatrist, carefully evaluated participants for signs of severe emotional distress or suicidal ideas. In this case, parents were excluded from the study to prevent any exacerbation of their mental health condition caused by recounting upsetting experiences and were referred to appropriate mental health services. Furthermore, given the expected high rates of post-traumatic stress in this peritraumatic period, all participants were offered during this initial meeting the opportunity to be provided with the Child and Family Traumatic Stress Intervention (CFTSI), which is an evidence-based brief intervention provided within 3 months of the child’s exposure to a traumatic event, founded at the University of Yale, and recently implemented at Saint-Eloi University Hospital. The CFTSI aims to increase understanding of common child post-traumatic reactions, improve communication between the child and caregiver about the child’s reactions to the event, and teach the caregiver and child coping strategies to reduce post-traumatic reactions (Berkowitz et al., Citation2011; Hahn et al., Citation2019).

2.4. Data analysis

Interviews were transcribed verbatim and anonymized, substituting names with functional codes. Transcripts were imported into NVIVO 10, and an inductive thematic approach was used to analyse data and allow for themes and patterns to emerge from the triangulated data (Morse, Citation2012). Preliminary data analysis and collection were conducted concurrently, allowing us to cease recruitment upon achieving coding saturation (Saunders et al., Citation2018). Data were compiled, disassembled, and reassembled, following a multistage recursive coding process (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). Following repeated data immersion to gain analytic insight into the data, transcripts were inductively coded separately by two researchers. Coding was redone as a group to reach a consensus on coding discrepancies and refine the codes. The framework for this study was developed using a bottom–up approach based on key themes emerging from the data (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006), with broad, overarching themes divided into subthemes. Within each theme and subtheme, the researchers drew comparisons, looking for overlap and differences, as well as newly emerging topics and patterns. The themes and subthemes were checked by asking five participants for feedback. Relevant suggestions were incorporated into the results.

3. Results

3.1. Sample characteristics

Throughout the recruitment period, 18 parents were referred by the ER and 26 by child mental health specialists, yielding a total of 44 potentially eligible participants. Among them, seven were excluded for the following reasons: suspicion of child abuse by the parents (n = 2), presence of parental severe emotional distress and suicidal ideas (n = 3), and having a child who was previously followed by the PI as their main child psychiatrist (n = 2). Among the 37 remaining respondents, three withdrew from the study by not showing up to the first interview, resulting in a total of 34 parents of 25 children who participated in the study. Parents included 26 mothers and eight fathers, with a mean age of 43.8 years. Most parents were French born (n = 31), with three parents born in another country. All parents held a university degree.

Children were aged from 11 to 16 years and included 16 girls. Most children were French born. Nine children had both their parents interviewed separately (18 parents) and 16 children had one parent interviewed (16 parents). In the latter cases, the other parent declined to participate. At the time of the study, nine children had already had a mental health follow-up that preceded the traumatic exposure, while only three had their child under a specific follow-up related to the traumatic exposure. The most predominant type of traumatic event found was exposure to sexual abuse. See for the children’s demographics.

Table 1. Characteristics of the children.

3.2. Themes and subthemes

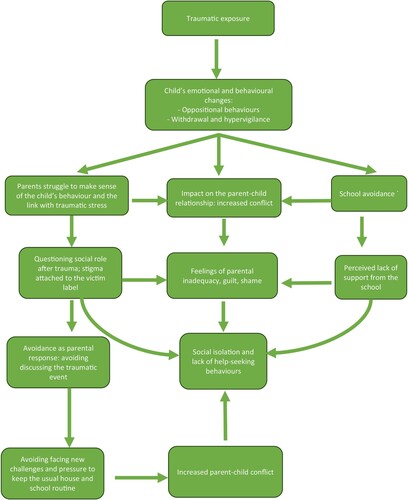

The most recurrent themes and subthemes that emerged from our inductive analysis of the parents’ perceptions and experiences are summarized in . Themes 1–4 are related to the consequences of the traumatic exposure experienced by parents, and themes 5 and 6 are related to mechanisms to which they resorted to deal with these consequences.

Table 2. Emergent themes and subthemes extracted from the interviews with parents.

3.2.1. Theme 1: Identifying the child’s behavioural and emotional changes following the traumatic exposure

All participants reported a wide range of behavioural and emotional problems manifested by the child following the traumatic exposure.

3.2.1.1. Subtheme: Difficulties with emotion regulation

All parents reported a change in their child’s ability to regulate emotions and noticed exaggerated responses to uncomfortable emotions as well as an irritable mood. Oppositional behaviours were also prominently reported, with refusal to follow house rules, slamming doors, and provoking fights: ‘She becomes easily frustrated and overreacts. I feel she is always angry […]’ (P2: 12yF). ‘She cannot stand a remark or a comment and challenges even the simplest house rules that were once a given’ (P4: 14yF). ‘When I remind him of a house rule, he slams doors and makes inappropriate verbal comments’ (P3: 11yM). Parents of children with a pre-existing mental health diagnosis noticed that their previous symptoms worsened: ‘He already had difficulties regulating emotions and anger because of his ADHD [attention deficit hyperactivity disorder] but I feel it is much worse now, the ADHD medications have no effect any more (P16: 15yM). Parents reported that their child seemed to be in a persistent underlying uncomfortable emotional state: ‘She often appears as she is on the verge of exploding into tears or screaming’ (P7: 14yF). ‘I feel he is constantly in a fragile emotional state, crying very suddenly or often being angry’ (P22: 13yM).

3.2.1.2. Subtheme: Hypervigilance state

Parents described that their children lived in a constant state of hypervigilance and hyperawareness: ‘She is jumpy and easily frightened’ (P21: 13yF). ‘He seems to be always on the lookout, checking to see if someone is walking behind him’ (P5: 13yM). This hypervigilance state ultimately affected their sleep, since parents noticed increased difficulties with sleep. ‘She stays up a lot more often, scrolling her phone’ (P20: 16yF). ‘She has sleep problems and is waking up very early’ (P32: 13yF). Nightmares were also preventing teenagers from sleeping through the night: ‘I know he is having nightmares because I hear him scream at night and he suddenly wakes up’ (P5: 13yM).

Parents observed that even though their child displayed more oppositional behaviours and rejected their support at times, they had some form of separation anxiety and requested more than usual the presence of their parents, especially at bedtime. ‘He requests I sleep next to him because he fears falling asleep alone and that something bad would happen’ (P8: 12yM). ‘I must go in her bedroom every ten minutes until she falls asleep’ (P11: 14yF). Moreover, the hyperawareness/hypervigilance state also manifested in eight girls who had experienced sexual assault as obsessive and compulsive-type behaviours, such as engaging in rituals of bathing, cleaning multiple times a day. ‘She spends hours in the bathroom washing herself’ (P4: 14yF). ‘She must wash her hands multiple times a day every time she touches something’ […] (P28: 15yF). Parents also reported that they felt their children wanted things done in a certain way or they would become upset: ‘She can’t stand not having things done in a certain way, in a certain order, especially regarding her personal items and clothes’ (P24: 12yF).

3.2.1.3. Subtheme: Withdrawal

Parents noticed that their children began to withdraw and did not want to engage in activities that they once found pleasurable. ‘She does not want to go outside any more and do fun things’ (P30: 13yF). ‘She spends hours in her room alone and gets angry if I try to intervene or engage with her’ (P26: 16yF).

3.2.2. Theme 2: Experiencing shame, emotional distress, and a negative impact on the parent–child relationship

Many parents reported how their child’s traumatic exposure and emotional changes impacted their own emotional state and feelings of parental efficiency, as well as their relationship with their child. Others reported being reminded of their own history of trauma as an emotional experience.

3.2.2.1. Subtheme: Dealing with guilt, shame, and feelings of parental inadequacy

Parents described a high sense of emotional burden along with worries about the future: ‘I feel sad, irritable, angry as to why this has happened to my child’ (P16: 15yM). ‘I can’t sleep at night, replaying in my head all the events prior to the aggression’ (P3: 11yM). ‘The worry is killing me. Will she forget this? Will she overcome it? What should I do?’ (P14: 13yF). A common concern that occurred among parents whose child was sexually assaulted was the potential long-term impact of the sexual aggression on their child’s relational and sexual development: ‘I have so many concerns about the future, I try to go online and read about the potential impact of sexual assault on a child’s development, I am afraid she won’t have normal relationships’ (P28: 15yF).

Furthermore, parents reported feeling inadequate in dealing with their child’s distress and behavioural changes: ‘I feel completely overwhelmed when she shuts down and I don’t know what to do. I feel I can’t handle her any more the way I used to’ (P33: 13yF). ‘When she throws inexplicable tantrums, I lose it completely, it’s like I am paralysed, whereas I used to deal calmly with this kind of situation’ (P27: 15yF). ‘No manual tells you what to do in these situations. I feel like a total failure as a parent’ (P22: 13yM). Parents also struggled with shame, guilt, and remorse while trying to construct meaning about the event and how it occurred: ‘I keep replaying the events of that day in my head and what I could have done to prevent [the sexual aggression] from happening’ (P19: 14yM). ‘I feel guilty that I was not able to protect my child. I hear people tell me these things happen, and I can’t prevent it, but there must be something I could have done to prevent this. It keeps me awake at night’ (P24: 12yF).

This meaning-making process varied depending on the traumatic event, who was involved, and who parents viewed as responsible. This was particularly influenced by whether they blamed themselves and/or others for the traumatic event. Since most incidents involved sexual assault (17 out of 25), parents usually did not blame the teenager, but blamed the assaulter, and also blamed themselves for not having fulfilled their parental role of protecting and keeping their child safe, for not setting stricter rules for going out at night (most assaults happened during parties and sleepovers at friends). In the case of the sudden death of a loved one (n = 2) or serious car accidents (n = 2), there was less expressed guilt, and they interpreted the event as being beyond anyone’s control.

3.2.2.2. Subtheme: Impact on the parent–child relationship: increased conflict

Participants reported that the traumatic exposure and the subsequent behavioural and emotional changes in their child impacted the family dynamic and their relationship with their child. They notably described that their child seemed to take out their anger on them and that whatever they did seemed insufficient or inadequate.

I can’t seem to get it right. Whatever I say or do […] If I try to engage with her, she rejects me. If I get too close it’s a problem and if I distance myself, she comes and searches for me, trying to pick a fight or blaming me for not being here to support her. Sometimes I feel she just needs a punching bag … . So, I end up getting angry myself, blaming her for being so irritable and selfish, I end up saying horrible things … (P18: 15yF)

Parents also reported not being able to bond with their child or efficiently communicate with him or her:

I can’t seem to be able to connect with her like I used to […] For example, we used to love going shopping together. Now she is in her room all the time and does not want to engage with me […] I can’t help myself feeling angry at her, and frustrated that she does not want to talk, I get this weird feeling that she is blaming me for what happened … (P17: 13yF)

Furthermore, some participants described that there was often a discrepancy between parents in the way in which they dealt with their child’s emotional and behavioural problems, and that this created additional tension in the family:

Her father can get very harsh at her when she shuts down or provokes us […] He loses patience and tells me I am too lenient, that this does not help her … . He said it’s not because she was sexually assaulted that she can allow herself to talk to us like this … that it does not help her that I act with her like a poor victim … . I am just trying to be patient but I end up fighting with my husband too. (P29: 14yF)

Her mother and I are fighting all the time because of her […] I think she should move on with what happened [referring to the sexual assault] and resume her normal life … . Her mother is acting with her like she is disabled or something … . I think it does not help her to be viewed as a victim. (P18: 15yF)

Parents also mentioned how these conflictual relations affected the siblings and the family dynamic, while disrupting family routines. They found it hard to respond to the siblings’ needs, which further added to their feelings of guilt and inadequacy.

3.2.2.3. Subtheme: Remembering earlier personal experiences

A few parents reported being reminded of their own history of trauma as an emotional experience, especially regarding sexual assault. Nine mothers said that their child’s sexual assault reactivated memories of their own sexual abuse during childhood, which overwhelmed them and made them less available for their child. However, this reactivation also provided them with the motivation to look after the child’s needs and avoid the pitfalls that they had encountered in their own experience. The following quotation illustrates this:

When she told me what happened with her, how this guy assaulted her at the party, I was immediately reminded of the sexual abuse I had to go through in my childhood … at multiple times, when he was supposed to take care of me when my parents were away, my uncle would touch me inappropriately … when I told my parents about it they would not believe me and it hurt me so much I figured I was the one who has done something wrong … […] All the anger was reactivated again but then I said I will not let this happen to my daughter … I am going to tell her and show her that I believe her and support her no matter what … even though sometimes it’s easier to ignore it ever happened … (P17: 13yF)

3.2.3. Theme 3: Struggling to understand trauma

Many parents struggled to understand the consequences of traumatic stress and to make sense of their child’s behaviour. They expressed and experienced stigma surrounding the victim status, which led to feelings of social isolation and reluctance to seek social support.

3.2.3.1. Subtheme: Questioning social role after trauma

Parents seemed to have an unclear understanding of the possible consequences of traumatic stress. The major concerns were related to how to communicate with their child and what to do about the problems that have emerged since the event, especially refusal to go to school and oppositional behaviours. However, the connection was not clearly established by participants between symptoms of traumatic stress and the traumatic event. This raised questions about social roles after trauma, and the extent to which the child might use the traumatic event as an excuse for ‘laziness’ and ‘poor performance’.

Sometimes I feel she is trying to take advantage of the situation … using what happened to her [referring to the sexual assault] to obtain adjustments and adaptations at school […] She only accepted to go see our family physician when we told her he could justify to the school her absence and ask for special accommodations. (P13: 12yF)

Many parents expressed uncertainty and confusion while interpreting their child’s behaviour, linking it to a lack of willpower or a way to take advantage of a situation, as illustrated by these quotations:

I threaten and tell him that if you don’t go to school […] you are clearly using what happened to you as an excuse and missing school will destroy your life, and your future … You should have some willpower. Everyone goes through hard things, will you stop your life and ruin your education because of this? […]. But I am really confused: how far should I push? (P19: 14yM)

I feel she victimizes herself a lot, she may even find some comfort in this … look how she is missing school now […] while she is fine going out with her friends again … ! […] so convenient, don’t you think? She is not making any effort any more … (P17: 13yF)

Five parents mentioned that they could not make sense of some of their daughter’s behaviours, following sexual assault. They described that their daughter was only interested in going out with her friends, missing school, and wearing ‘provoking and slutty’ outfits. While they did not blame their daughters for the sexual assault per se, they struggled to understand how a girl could wear these outfits after having been sexually assaulted. The following quotation illustrates this:

Call me old-fashioned but I don’t get it … how can she wear these outfits after being sexually assaulted? I mean … is she searching for it again? I am really confused […] when I tell her this, she gets angry and mad or withdraws for several days in her room, refusing to talk to me […] I don’t get it … (P1: 15yF)

3.2.3.2. Subtheme: Stigma around the victim label and social isolation

The vast majority of participants (28 out of 34) reported feeling socially isolated and struggling to share what happened to their child with family and friends, mainly because of the stigma attached to the victim status. They feared that it would ‘label’ their child as a ‘victim’, maintain the child in this social role, and preventing him or her from moving on. They also explained it by the lack of availability of their friends and families, who all had busy lives, or lived in other cities hours away from them, and their reluctance to ‘burden’ them with what they perceived as a very private matter. However, this came at the cost of parents feeling alone and isolated, with limited possibilities for sharing and reflecting on their problems with their child outside their couple. More specifically, since parents mentioned repetitively the uncertainty towards the ‘right’ attitude, between being demanding and being protective, as their most prominent concern regarding their parental role, they expressed that it would be easier if they knew parents living in the same situation with their children. The following quotations illustrate this notion:

We cannot talk to our family and friends about what happened, they will always look at her as ‘the victim’ … and also we feel a lot of guilt and we don’t want to answer people’s questions … so we’re very isolated, and we often fight about the right attitude to have with her […] I didn’t find the answer in any book, or website, I tried to search … we feel we are very lonely in this experience, if only we could meet other people going through the same thing it would be easier to talk about, to share our experiences and know we are not alone … (P24: 12yF)

You feel like you are the only person it has ever happened to, like I was the only person that felt like this. So maybe it would help if you knew other people in the same situation. (P17: 13yF)

3.2.4. Theme 4: Struggling with the child’s school refusal and lack of school collaboration

A major theme that emerged distinctively was the child’s refusal to go to school and a perceived lack of support from the school, which prevented parents from providing optimal support for their child.

3.2.4.1. Subtheme: School avoidance

A major problem reported by most parents (29 out of 34) was the impact of the traumatic event on school attendance. Parents described that children tried to avoid school, often missing classes, and either refused to go to school or were sent back home from school after multiple physical complaints. ‘The school nurse would call me every day to tell me to come bring my child home because she is sick’ (P2: 12yF). ‘Her school performance dropped, she was always late at school [after the event happened] until she declared she would not attend school any more and that we cannot force her’ (P24: 12yF).

3.2.4.2. Subtheme: Perceived lack of appropriate support and collaboration from the school

Another important topic that parents pointed out as a structural obstacle in supporting their child was the lack of adequate school–home collaboration. Parents reported a considerable need for supportive collaboration between school and home since their child manifested difficulties in and refusal over school attendance. New needs for adjustment emerged, such as arrangements about workload, deadlines, and absence. Only one parent said that their adolescent carried on where they had left off and that academic functioning stayed the same. Another three adolescents’ performance levels stayed the same according to their parents, but it involved compensating with enormous efforts at home that ultimately led to more parent–child conflict. For the remaining 21 adolescents, parents reported considerable changes in school attendance and performance that required extensive support from home and arrangements in their own work schedule to be more present with their child (for example, taking unpaid leave or sick leave from their employment).

Some parents reported that they had to initiate or pressure the school into collaboration regarding educational adjustment measures (18 parents), as illustrated by this quotation:

We had to talk to the principal time and again about what happened, even though it was not easy for us … . I really believe that if the school hadn’t come under so much pressure from the psychiatric team and family physician to make adaptations available, they would have done nothing … (P19: 14yM)

Nine participants questioned the role of the teachers, wondering if they were sufficiently prepared for teaching students who had been exposed to traumatic events.

My son is absent a lot from school, he does not sleep at night and can’t get up in the morning … . I asked the school what measures they could offer, but they had no ideas […] After heavy pressure from our family physician, they finally became generous with adjustments. […] Still, I think they could have been more supportive, talk to him at least, ask him, ask us, instead we had to go look for all the solutions. It’s like they had no clue how to deal with children in these situations … (P8: 12yM)

Seven parents perceived the lack of understanding and absence of flexibility in the school setting as a hopeless situation where they had to fight for credibility. They described that this lack of understanding from the school added further pressure to an already strained situation.

My daughter and we talked about the need for flexibility regarding adaptations, even though the school psychologist backed us up, the school administration remained very rigid about it, insisting on her making more effort instead of supporting her to regain functionality progressively … we had many heated discussions with them and we were accused of being too lenient […] it feels like a fight for credibility and it only adds to our exhaustion … (P4: 14yF)

My son gets extremely panicky every time he leaves home because he fears it will happen again to him on the streets, and the school refuses to take this into consideration … so I told my husband I prefer that he drops school this year, subscribe into a home-schooling programme because really I don’t see any solution with them … (P12: 13yM)

3.2.5. Theme 5: Resorting to avoidance to deal with conflicting needs and demands

Most parents felt challenged in finding ‘the right attitude’ and a good balance regarding several conflicting needs. Most of the time, they resorted to avoiding sensitive topics while navigating antagonistic demands.

3.2.5.1. Subtheme: Avoiding discussing the traumatic event with the child

Participants expressed confusion and doubt as to whether they should focus on the traumatic event that happened with their child or put all of their efforts into helping their child resume a normal life. They avoided talking to or asking their child about the event, or how she or he feels about it, or giving them too much attention, because they felt that ‘life should go on’, as found in 25 transcripts and as illustrated by this quotation:

I struggle to find a good balance between giving too much attention to what happened, and just go on with normal life … . I fear that if I focus too much on the incident, she will stay stuck in a victim position, and she would not be able to move on […] I mean, after all, life should go on … . I want her to focus on other aspects of life rather than be caught in this unfortunate incident [referring to a sexual assault]. (P14: 13yF)

Other parents preferred avoiding discussing the traumatic event altogether because they felt uncomfortable and believed that they lacked the knowhow to bring up the subject.

I don’t know how to approach the subject with him, what to tell him, how to comfort him … . I am not a psychologist after all, I am afraid to say or do something that would worsen his situation […] And I don’t want to focus too much on what happened, I prefer to help him forget about what happened […] after all, life should go on […] (P12: 13yM)

This was also emphasized by the fact that the child often avoided talking and thinking about the event and reacted strongly to any reminder of it: ‘She refuses to talk about what happened, when I try to initiate the discussion, she shuts down completely or gets angry’ (P23: 13yF); ‘She refuses to see her friends that were at the party where it happened’ [referring to the sexual aggression] (P11: 14yF); ‘He does not want to talk about it. He reacted very strongly the few times we tried to bring up the subject’ (P12: 13yM).

Even though most participants emphasized the importance of resuming normal routines and focusing on other aspects of life, they felt confused at times as to whether avoiding the subject might minimize the experience of the child:

I try not to focus too much on what happened and help her to get back to her normal life … I don’t know if it is the right attitude after all, maybe she needs to talk about it, maybe she is waiting for me to open the subject? […] I don’t feel comfortable asking her … and she does not want to talk about it also … so better focus on moving on … (P15: 13yF)

3.2.5.2. Subtheme: Avoiding facing new challenges: pressure to keep the normal house and school routines

Another area of conflicting needs was the dilemma faced by parents about keeping the usual house and school routines versus being flexible in the aftermath of traumatic exposure. Parents expressed struggling to achieve what they perceived as general advice to help their teenagers to get ‘back to normal’, in line with their own expectations that ‘life should go on’. Yet, their arduous attempts to restore performance and normality were hindered by the fact that their adolescents now behaved differently, had different needs, and were barely functional. Participants pointed to enormous efforts in trying to build completely new functioning daily lives and routines. As one parent described it:

We heard we have to get to a normal everyday routine as soon as possible, our daughter has to keep attending school all the time, do her normal extracurricular activities, we have to keep going, like if nothing happened … . Ok I get it, we have to get an everyday life going, but how do you do that really when you have a child who refuses to get up from the bed in the morning, who’s not mentally ready to learn anything […] well in that case just going for a short walk with her is an achievement and has to be negotiated for hours … (P20: 16yF)

You could say that I force her into a routine, what else can you do? I know it may sound brutal to you, it is brutal to me too to force my child to get up and go to school […] but neither her father nor I would give in […] we would practically pull her physically out from bed while she is screaming, but it did result in her going back to school and doing some exercise again […] It’s a war field every morning, her siblings witness these horrible starts of the day, her screaming that she hates us, that she will never forgive us … . But we do this for her, we are convinced it is positive to maintain her normal routine and it is a goal for us … . You could say we coerce her into it … (P6: 12yF)

3.2.6. Theme 6: Finding ways to cope

Less than half of the participants tried to actively find ways to cope and navigate through the conflicting needs and demands of their children in the aftermath of traumatic exposure. They adapted to the situation by setting realistic objectives and dealing with present needs, restoring a sense of meaning and agency, accepting, at times, help from family and friends, and seeking professionals’ advice. Parents who were able to find these ways to cope were distinct from those who resorted to avoidance as the main mechanism to deal with the child’s traumatic stress.

3.2.6.1. Subtheme: Dealing with the present situation and needs: ‘One thing at a time’

Twelve parents described how they came to admit that they would not be able to achieve resuming normal house and school routines and ‘getting back to normal’, only weeks after the traumatic event, and that they had adjusted to that situation. They were able to let go of the performance-oriented perspective and had shifted the focus to helping and supporting the adolescent in just ‘surviving the day’. They tried to respond to the challenges of sleeping, eating, and finding some daily structure, even if this involved letting go of the usual ‘normal routines’ requirements. They opposed the general advice of getting back to normal as soon as possible, saying that it did not match their new reality or their children’s needs. They revised their expectations from their child and tried to adapt to his or her current needs and situation, while setting minimalistic goals every day; for example, getting the adolescent out of the bed each morning and doing some meaningful tasks. They adopted a practical approach aiming at mobilizing the necessary logistic support to meet the daily basic needs:

My wife and I, we decided to accept that she cannot come back to school now … we agreed we would not force her into it, we said ok, let’s first try to make her get up every morning and do something, like walking the dog became an achievement, or playing a game together … . We had to revise our expectations and decided to give her the time, to do one thing at a time […]. (P30:13yF)

Parents who were able to resort to this pragmatic approach described that it helped them to appreciate every small piece of progress and improved their relationship with their child, since they were not forcing them into attending school, for example.

3.2.6.2. Subtheme: Risk of overaccommodation

Despite the improvement in the parent–child relationship following parents’ adjustments to their child’s current needs, parents who resorted to this mechanism reported that it necessitated their ongoing involvement and continuous presence, assisting and compensating for the adolescent’s lack of daily functioning. The following quotation illustrates this:

But one of us must be continuously with her or she would isolate herself in her room again. We had to make huge adaptations at work, I am self-employed so I manage, but my wife she will end up having problems with her employer […]. (P18: 15yF)

Moreover, five among them (five out of 12) did not feel that these new measures fell naturally into the parental role.

Since I stopped fighting with her and forcing her to do things, like cleaning her room and attending school, you could say that many of our conflictual interactions improved and I am able to connect with her at times … she smiles to me again, we go for a walk together, I feel she is opening up a bit more […] but you know it doesn’t feel normal, it doesn’t feel it is what a parent should do, I still feel a lot of guilt, and wonder if I should do anything differently […]. (P30: 13yF)

3.2.6.3. Subtheme: Restoring a sense of agency

Among those parents who dealt with the present situation and needs, without avoiding the necessary subsequent adaptations, six demonstrated and expressed agency, a sense that they had control over their lives, and the ability to impact their environment and their child’s remission, no matter how hard the current situation was. They expressed determination in the face of obstacles and in supporting their child. Agency was mutually reinforcing with two other factors that contributed to those parents coping with the situation: hope and self-esteem; more specifically, a positive perception of themselves as parents. A belief in their own parental efficiency supported parents’ beliefs that they were of value and that they had reason to be hopeful about the future of their child, as illustrated in the following quotations:

I am hopeful things will get better […] I am doing everything I can to support my child after this horrible event and I believe she will be able to move on with time and with our support. I show her and tell her that I am not afraid, this assault will not determine our lives, her future and our future as a family, I keep taking care of myself so she sees I can handle it, I will not collapse with her, but I will hold her through it […]. (P29: 14yF)

It is all about regaining control over your life, whatever you had gone through […] he is not there yet, but I know I can help him with time realizing it. (P5: 13yM)

3.2.6.4. Subtheme: Seeking help from family, friends, and professionals

The same parents who explicitly expressed a sense of agency, along with three others, described that they could reach out to their family, friends, and neighbours. They were mostly open to accepting help for their practical and logistic needs, while they were more reluctant to accept emotional support. They described that turning to these relationships and seeing people positively answering to their needs for support further enhanced their agency and hope and promoted help-seeking behaviours. These parents expressed less stigma around the victim status.

I was reluctant at first to reach out to my friends and family […] I mean you know how it is, everyone has his own life, issues and problems you don’t want to overwhelm people with yours […] but then I realized I will not be able to support my child if I myself am not supported […] my sister she lives in another city in France but I called and told her everything, told her I needed some presence and practical support […]. Within a week she came to visit and stayed for three weeks, helping me with basic logistics of daily life, but it made all the difference to me, it made me feel valued, it relieved me from all the logistic constraints to be able to be more emotionally present to my daughter and also my other children […] when she had to leave, I felt more comfortable asking a friend for help and reiterate the experience […]. (P34: 16yF)

Another source of help mentioned was that of professionals to whom parents turned, when possible, for advice and guidance. The most cited professionals were the family physician, the school counsellor, and, in cases where the child had a previous mental health follow-up, their regular psychologist or psychiatrist. Parents reported that professionals had a compassionate ear, tried to alleviate their guilt, and helped with providing recommendations for adjustments and special arrangements at school. However, they still felt that professionals did not provide them with practical tools and solutions to deal with the conflicting needs and demands or to understand and cope with their child’s emotional and behavioural problems. They also described them as giving vague or elusive answers to the parents’ pressing questions, as to how long these problems would last and how the traumatic event would affect the child in the long term.

4. Discussion

4.1. Overview

We aimed to understand the experiences, reactions, and perceived needs of 34 parents of 25 adolescents who had been exposed to a traumatic event in the past 3 months, with 17 out of 25 of the traumatic events being sexual assaults. Our findings reveal that parents struggled to understand the behavioural and emotional changes that they identified in their children. They reported that their relationship with their child had become conflictual, and struggled with feelings of guilt, shame, and inadequacy. They questioned their social role after trauma and felt socially isolated, mainly because of the stigma attached to the ‘victim status’. The issue of school avoidance and lack of collaboration with the school emerged as major structural obstacles experienced by parents while trying to support their child.

In trying to navigate conflicting needs brought by the traumatic exposure, parents fell into two distinct categories. Those who experienced distressing levels of shame and guilt tended to resort to avoidance as a coping mechanism, avoiding discussing the traumatic event with their child, and pressuring them instead to resume life as it was before, even though it did not conform to their real experience and needs, while perpetuating conflictual relationships. Fewer parents adapted by revisiting their beliefs and expectations that life should go on as if nothing happened and by trying to come up with new functional routines, with nevertheless a perceived risk of overaccommodating the child’s maladaptive behaviours. Parents who adapted to the functional consequences of traumatic stress and revisited their daily routines, however, were able to restore some level of connection with their child, and a sense of agency and hope, and to seek help from family, friends, and professionals.

summarizes the connections between the themes and subthemes related to family consequences of traumatic exposure and avoidance as a parental response.

4.2. Parents tended to identify externalized rather than internalized symptoms

In line with previous studies (Rescorla et al., Citation2013, Citation2017), parents’ observations of their child’s difficulties emphasize externalized behaviours rather than internalized ones and therefore do not necessarily reflect the emotional experience of children themselves. The symptoms observed fit into the category of post-traumatic stress, according to the DSM-5 criteria (APA, Citation2013). Flashbacks and intrusive symptoms, however, were not reported by parents, which may be explained by children not sharing these symptoms because it might involve talking about the traumatic event, which could trigger further post-traumatic reactions (Meiser-Stedman et al., Citation2007).

Dissociative states per se were not reported by parents, even though they might be experienced in post-traumatic reactions; however, parents may not recognize dissociative symptoms if they lack knowledge about them, and these symptoms may be hindered by other symptoms, such as ‘shutting down for hours’ or ‘withdrawing in the room for several hours’.

One striking observation by parents was the emergence of obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD)-like behaviours in eight girls who had been sexually assaulted, while these symptoms were not noted prior to the assault. At this point, it is unclear whether these symptoms are part of an acute post-traumatic reaction and would resolve with time, or whether they constitute inaugural symptoms of long-term OCD. Studies investigating the association between CSA and OCD yield contradictory findings, with some having shown an increased rate of CSA among patients with OCD (Caspi et al., Citation2008; Grisham et al., Citation2011), while others have not (Carpenter & Chung, Citation2011). Adults with OCD and a history of CSA, however, have higher OCD symptom severity and more treatment resistance than those without a history of trauma (Boger et al., Citation2020; Visser et al., Citation2014). There is also some evidence that childhood trauma may play a role in the development of OCD, particularly cleanliness and washing behaviours (Lochner et al., Citation2002; Mathews et al., Citation2008). More prospective research is needed on this subpopulation of children who develop OCD-like behaviours following sexual abuse. An important clinical implication of this finding is to highlight the importance of screening OCD-like behaviours in children and adolescents following CSA exposure to provide early interventions.

4.3. Parents struggled to understand trauma and questioned their child’s social role after trauma, while experiencing shame and stigma, which impacted the parent–child relationship, increased feelings of parental inadequacy, and affected help-seeking behaviours

It was striking how few trauma-informed explanations were used by parents when describing their child’s reduced functioning, while seeking to attribute the causes of the changes within a moral framework rather than a trauma framework: Is my child lying or telling the truth? Is he taking advantage or the situation and using it as an excuse to be lazy? This parental attitude towards children exposed to a traumatic event and their suspicion that their children might be lying or taking advantage of the situation has been observed elsewhere (Røkholt et al., Citation2016) and seems to reveal a lack of knowledge about the functional consequences of traumatic stress. This poor understanding of trauma appears to fuel miscommunication between parents and children and lead to more conflictual relationships and more parental distress. This misunderstanding can also be explained by the fact that parents did not have access to their child’s inner thoughts or feelings, but instead had to deal with externalized symptoms that they struggled to make sense of.

This finding has an important implication in clinical practice as it emphasizes the importance of integrating psychoeducation on traumatic stress beginning at the primary care and paediatric emergency level. Psychoeducation allows the identification of post-traumatic symptoms and the understanding of trauma. This, in turn, can help to normalize reactions, seeing them as understandable and expected, which would help the teenager to feel validated and understood rather than judged and controlled (Smith et al., Citation2019; Stallard et al., Citation2001), and improve parent–child communication while reducing both the parent’s and child’s anxiety levels (Kerbage et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, the parental process of normalizing and validating expectable and intense emotionally dysregulated states while explicitly linking the behavioural change to the traumatic exposure can promote children’s abilities to regulate emotions and develop more adaptive strategies (Hobfoll et al., Citation2007; Kerbage et al., Citation2022). In addition, a more in-depth understanding of trauma beyond the basic knowledge of symptoms may be warranted to make sense of some behaviours that can seem confusing, such as oppositional behaviours, taking out the anger on family members, or wearing provocative outfits following sexual assaults. Understanding loss of control and helplessness as central to the traumatic experience may help parents to understand these behaviours as a maladaptive attempt to regain control over oneself after trauma and to grasp why traumatized children may experience rules and directives as a repetition of the experience of being controlled (Herman, Citation1997; Van Der Kolk, Citation2015).

More broadly, this parental doubt regarding the authenticity of symptoms was found to be related to the stigma attached to the victim status. Parents of children who were sexually assaulted expressed feelings of shame and were reluctant to seek help from friends and family members because of this stigma, which ultimately contributed to their feeling socially isolated. The representation of a ‘victim’ was that of a person who finds some kind of complacency in their situation, taking advantage of the attention and arrangements brought by this situation, while lacking the willpower and sense of responsibility deemed necessary to be able to ‘move on’. This stigma around the ‘victim’ status may reflect a broader societal representation around victims of sexual abuse and lead to internalized stigma in survivors, increasing their feelings of shame, guilt, and self-blame, perpetuating their post-traumatic symptoms, and mediating their long-term adverse outcomes (Coffey et al., Citation1996; Gibson & Leitenberg, Citation2001; Schomerus et al., Citation2021). It is important for health professionals to be aware of the impact of stigma and shame around the victim status, and to address it clinically through an honest conversation with parents about social representations surrounding sexual assault survivors, and how these stereotypes can be deleterious and prevent them from seeking support. This awareness of stigma, coupled with psychoeducation about traumatic stress and enhancing social support, can increase parents’ understanding of their children’s behaviours as well as their capacity to efficiently support them.

4.4. School avoidance and lack of perceived support from schools highlight the importance of promoting trauma-informed approaches among teachers

Of particular concern was the frequent report of considerable changes in school attendance, which can be explained in many intricate ways. There is evidence that post-traumatic stress alters learning processes by inducing impairments in verbal memory, along with complex attention and executive skills, all of which lead to cognitive impairment (Elzinga & Bremner, Citation2002; Johnsen & Asbjørnsen, Citation2008). This drop in school performance can further affect the self-esteem of teenagers who have just been impacted by a traumatic event, which, in turn, leads to their missing school. This can be particularly marked in children with pre-existing school difficulties, with the traumatic exposure further affecting their school performance. In addition, refusal to go to school can be a post-traumatic avoidant symptom. A third explanation can be post-traumatic oppositional behaviour and an attempt to regain control after the traumatic event by opposing usual routines (Perrin et al., Citation2000).

In dealing with this school avoidance, one of the major structural obstacles reported by participants was the perceived lack of appropriate support from the school. According to the French Education Act, schools have the responsibility for providing accommodations and revised learning goals and methods for children with chronic disabilities; however, trauma is not cited in the list of eligible conditions, and this may have constituted an administrative obstacle when considering school accommodations. Some parents ended up dropping the issue of school and shifting to home-schooling to avoid altogether the difficulty of implementing adjustments. However, this may have a deleterious long-term effect since it increases avoidant behaviours in young people, which can perpetuate post-traumatic symptoms (Smith et al., Citation2019). In addition, parents felt that teachers were not equipped to deal with trauma-exposed children, which is in line with several qualitative studies reporting that teachers felt unsure about their role while dealing with students exposed to trauma and lacked understanding about the educational consequences of traumatic stress (Alisic, Citation2012; Dyregrov et al., Citation2013; Papadatou et al., Citation2002). Since negative social experiences in the aftermath of traumatic exposure are strong risk factors for PTSD (Kithakye et al., Citation2010; Ozer et al., Citation2003), our findings have practical implications by highlighting the need to raise awareness about the concept of trauma and its functional consequences in schools, building capacities among teachers to help them to support trauma-exposed children, and anticipate reduced learning capacity following traumatic exposure.

4.5. Parents fell into two distinct categories while dealing with their child’s behaviour: avoidance/shame/social isolation versus dealing with present situations and needs/agency/social support

Two distinct parental responses emerged in facing the challenges brought by the aftermath of the traumatic exposure: In the first case, which was the majority, parents experienced high levels of shame and stigma and tended to avoid discussing the trauma altogether. They believed that ‘life should go on’ as it was before the incident and pressured their child to resume ‘life as usual’, leading to more conflictual interactions. In the second category, parents tried to resolve this paradox of conflicting needs and the pressure of moving on by coming to terms with their new reality and dealing with ‘one thing at a time, one day at a time’. This coping mechanism has already been observed in other settings (Foster et al., Citation2017; Røkholt et al., Citation2016), and allowed parents to restore broken relationships with their children by displaying more realistic expectations and decreasing pressure on the child. However, it did not fall naturally into the parental role and required extensive logistic accommodations. Parents wondered how long these adaptations would last, and whether they were harming their child by accommodating too much and dealing with them as a special case. This dilemma has practical implications in clinical practice regarding psychoeducation content on post-traumatic recovery. In earlier understandings of grief and trauma, the bereavement process was believed to develop in separate stages, with the goals being to forget, finish with the pain within a few months, and resume normal life (Lindeman, Citation1944). A newer grief theory, however, sees bereavement as a process of oscillation between focusing on loss and focusing on restoration over a long period of time, which is closer to real experience (Bugge et al., Citation2012; Stroebe & Schut, Citation1999). More recent theories of post-traumatic recovery also emphasize this ongoing interaction between the stabilization of post-traumatic symptoms, processing of traumatic memories, and post-traumatic remission (Southwick et al., Citation2011). Including this knowledge on post-traumatic recovery as a dynamic and evolving process, rather than a rigid, linear task, in the psychoeducation of parents would allow them to normalize and expect that there might be difficult moments and relapse amid the recovery process. Acquiring more cognitive flexibility through knowledge about trauma and recovery would facilitate distress tolerance and the development of healthy coping strategies (Gil-Rivas & Kilmer, Citation2013; Wojciak et al., Citation2022). In our study, few parents were able to reach this conclusion by themselves, displaying a sense of agency in the face of stress by revisiting their expectations, normalizing their experiences, setting realistic daily goals, adapting to the present needs, and focusing on restoring communication with their child.

4.6. A conceptual model of early intervention to promote parental support in the wake of the child’s traumatic exposure

Our findings can be best interpreted through a multisystemic and ecological framework, where trauma and resilience are implicated in both individuals and systems (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2021; Ellis & Dietz, Citation2017). This best explains why resilience and recovery after trauma do not rely solely on a child’s attribute or trait (Bonanno, Citation2021) but depend closely on resilient families and communities. The multiple layers of resilience therefore include individual resilience, family resilience, and community resilience. Individual resilience is best described as a process by which an individual utilizes their internal and environmental resources to overcome stressful situations or adversity (Baker et al., Citation2021). Family resilience is conceptualized as a process consisting of mobilizing interpersonal family resources and strengths within the family to facilitate good outcomes despite risk exposure within a family system (Maurovi´c et al., Citation2020). Community resilience can be defined ‘by the process by which a community can anticipate risk, limit effects, and rapidly recover through adaptation to community-wide trauma and adversity’ (Ellis & Dietz, Citation2017). In addition, our findings reveal that one important component impacting how parents supported their child was their belief systems about the validity of their child’s behaviours, the victim status, how recovery should be, and their role in the process. Participants who demonstrated cognitive flexibility were able to question their belief systems that things should get back to normal as soon as possible, and adapt to their child’s needs by prioritizing the restoration of the relationship with their child over expectations of performance and functionality. This improved the parent–child relationships, which, in turn, enhanced agency by promoting self-esteem, and feelings of parental efficiency and hope, and facilitated more help-seeking behaviours. Furthermore, the concept of resilience and post-traumatic growth implies acquiring new adaptive strategies, rather than just resuming life and functionality exactly as they were before the traumatic exposure (Kilmer et al., Citation2014).

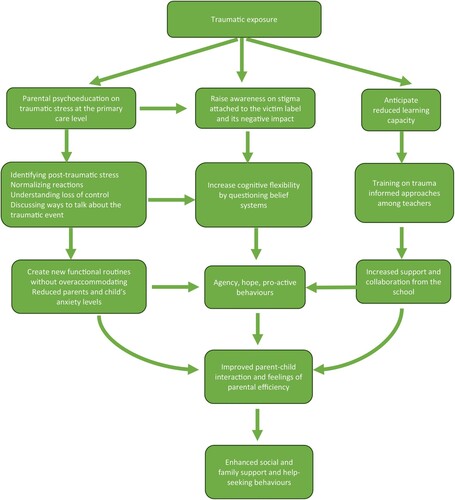

In addition, parents who resorted to health professionals for guidance did not feel that they got the help they needed to deal with their child’s problems. Since most of the professionals mentioned were primary healthcare workers, this points to the importance of increasing awareness and training about trauma-informed approaches at the primary healthcare level. Indeed, being trauma informed and resilience oriented should not only be a matter for highly specialized mental health professionals; it should involve frontline workers at all levels of the pyramid of interventions, as conceptualized by the Interagency Standing Committee (IASC), from basic needs up to specialized clinical services (IASC, Citation2007). (See Supplementary Material 2, adapted from Bah et al., Citation2018, for the IASC pyramid.) Even though the IASC pyramid of services was initially conceptualized for mental health and psychosocial support in crisis settings (war, natural disaster, migration crisis, etc.), we believe, based on our findings, that it can apply to situations involving other types of traumatic events such as sexual assaults, since trauma disrupts social, family, and community networks, as well as the basic sense of security and safety, all of which need to be addressed at an early stage with multiple overlapping layers of interventions, and not only through specialized clinical services. Trauma-informed approaches do not necessarily mean trauma-focused clinical specialized approaches; they encompass being sensitive to the needs of people who have recently been affected by trauma, by ensuring that they can meet their basic needs, strengthening their family and community support networks, helping them to identify post-traumatic stress, and reinforcing coping strategies, emotion regulation, and parent–child communication, all of which are protective factors in the face of adversity (Kerbage et al., Citation2022; Levenson, Citation2017; Roberts et al., Citation2019). suggests a model for practical early post-traumatic interventions to promote adaptive parental responses, such as cognitive flexibility and agency, and enhance social support.

4.7. Limitations