ABSTRACT

Background: The changes DSM-5 brought to the diagnostic criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) resulted in revising the most widely used instrument in assessing PTSD, namely the Posttraumatic Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5).

Objective: This study examined the psychometric properties of the Romanian version of the PCL-5, tested its diagnostic utility against the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID-5), and investigated the latent structure of PTSD symptoms through correlated symptom models and bifactor modelling.

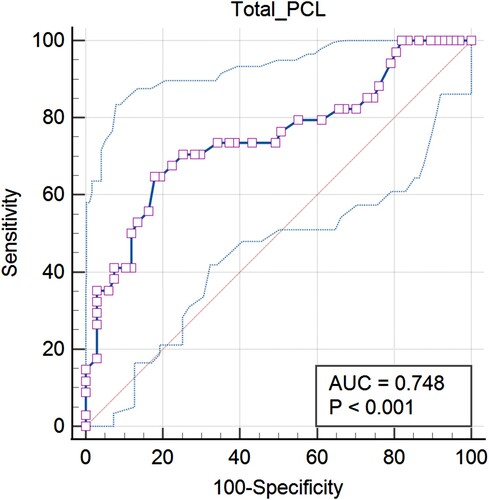

Method: A total sample of 727 participants was used to test the psychometric properties and underlying structure of the PCL-5 and 101 individuals underwent clinical interviews using SCID-5. Receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) analyses were performed to test the diagnostic utility of the PCL-5 and identify optimal cut-off scores based on Youden's J index. Confirmatory Factor Analyses (CFAs) and bifactor modelling were performed to investigate the latent structure of PTSD symptoms.

Results: Estimates revealed that the PCL-5 is a valuable tool with acceptable diagnostic accuracy compared to SCID-5 diagnoses, indicating a cut-off score of >47. The CFAs provide empirical support for Anhedonia, Hybrid, and bifactor models. The findings are limited by using retrospective, self-report data and the high percentage of female participants.

Conclusions: The PCL-5 is a psychometrically sound instrument that can be useful in making provisional diagnoses within community samples and improving trauma-informed practices.

HIGHLIGHTS

This study offers an in-depth analysis of the Romanian version of the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5), exploring its psychometric properties, diagnostic utility, and latent structure.

An optimal cut-off score was identified for PTSD diagnosis using the SCID-5, providing essential insights into the diagnostic process and enhancing its utility in clinical assessments.

Using bifactor modelling and other statistical methods, various PTSD models were compared to offer valuable guidance for future research, assessment, and interventions in this field.

Antecedentes: Los cambios que el DSM-5 introdujo en los criterios de diagnóstico para el trastorno de estrés postraumático (TEPT) dieron como resultado la revisión del instrumento más utilizado para evaluar el TEPT, llamado Lista de verificación postraumática del DSM-5 (PCL-5, por sus siglas en ingles).

Objetivo: Este estudio examinó las propiedades psicométricas de la versión rumana del PCL-5, probó su utilidad diagnóstica frente a la Entrevista Clínica Estructurada para el DSM-5 (SCID-5, por sus siglas en inglés) e investigó la estructura latente de los síntomas de TEPT a través de modelos de síntomas correlacionados y modelado bifactorial.

Método: Se utilizó una muestra total de 727 participantes para probar las propiedades psicométricas y la estructura subyacente del PCL-5 y 101 individuos se sometieron a entrevistas clínicas utilizando la SCID-5. Se realizaron análisis de la curva característica operativa del receptor (ROC, por sus siglas en ingles) para probar la utilidad diagnóstica del PCL-5 e identificar puntuaciones de corte óptimas basadas en el índice J de Youden. Se realizaron análisis factoriales confirmatorios (AFC) y modelados bifactoriales para investigar la estructura latente de los síntomas de TEPT.

Resultados: Las estimaciones revelaron que el PCL-5 es una herramienta valiosa con una precisión diagnóstica aceptable en comparación con los diagnósticos SCID-5, indicando una puntuación de corte de >47. Los AFC brindan respaldo empírico para los modelos de anhedonia, híbridos y bifactoriales. Los hallazgos están limitados por el uso de datos retrospectivos, autoinformados y el alto porcentaje de participantes femeninas.

Conclusiones: El PCL-5 es un instrumento psicométricamente sólido que puede ser útil para realizar diagnósticos provisionales dentro de muestras comunitarias y mejorar las prácticas informadas sobre el trauma.

PALABRAS CLAVE:

1. Introduction

Exposure to a traumatic event is a prerequisite for the development of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013) and it may be more prevalent than previously believed. According to a World Health Organization (WHO) study, over 70% of participants reported exposure to one lifetime traumatic event, and 30.5% exhibited more than four such events (Benjet et al., Citation2016). Since 1980, when PTSD was recognized as a disorder in the third edition of the psychiatric nomenclature (DSM-III; APA, Citation1980), its definition and diagnostic criteria have undergone several changes. In DSM-5 (APA, Citation2013), PTSD has been framed in a chapter named ‘Trauma and Stress-Related Disorders,’ the emotional response criterion (A2) has been eliminated, the symptoms diagnostic clusters extended to four (i.e. re-experiencing, avoidance, negative alteration in cognition and mood, and alteration in arousal and reactivity), and three symptoms were added. Consequently, changes have also been made to assessment questionnaires related to PTSD. The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5; Weathers et al., Citation2013b), updated for DSM-5, is the most widely used and highly cited self-report instrument for PTSD. Based on the citation report from Web of Science (WoS), the PCL-5 and has received over 14,642 citations. The PCL-5 incorporates these changes by substantially revising 11 items, assessing three additional symptoms (i.e. blame, negative emotions and reckless or self-destructive behaviour), changing the scoring scale to 0–4, and consolidating previous versions into a single instrument for all users, eliminating military, civilian, and specific-events versions (Blevins et al., Citation2015). This instrument is intended for several purposes serving clinical and research environments through assessing PTSD symptoms, the underlying structure, or making a provisional diagnosis. The latter can be obtained through the algorithmic scoring method that follows the DSM-5 diagnostic rule (i.e. at least one PCL-5 item rated with two or higher for Criteria B and C, and at least two items rated with two or higher for Criteria D and E; Weathers et al., Citation2013b).

The PCL-5 has demonstrated excellent psychometric properties on military, community, and mixed samples (Armour et al., Citation2015; Tsai et al., Citation2015). Several studies have validated its use across populations, highlighting its strong internal consistency, with Cronbach's alpha values ranging from .92 to .94 for the total score and from .78 to .89 for subscales (Boysan et al., Citation2017; Krüger-Gottschalk et al., Citation2017; Liu et al., Citation2014), and McDonald's omega values ranging from .88 to .95 (Stanley et al., Citation2023). While effective in capturing essential PTSD traits, distinguishing unrelated ones, and useful for detection (Forkus et al., Citation2023), further research is necessary to confirm its alignment with gold-standard diagnosis across different samples.

To evaluate the PCL-5's efficiency as a diagnostic tool and determine its optimal cut-off score, it is essential to compare it with a gold-standard structured clinical interview like the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5; Weathers et al., Citation2018) or the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5, the Clinician Version (SCID-5-CV; First, Citation2015). Even heterogeneous, cut-off scores between 30 and 48 proved efficient in predicting PTSD diagnosis when benchmarked against these standards (sensitivity = 0.60–0.97, specificity = 0.68–0.97, overall efficiency = 0.78–0.96; Bovin et al., Citation2016; Boysan et al., Citation2017; Pereira-Lima et al., Citation2019).

1.1. The latent structure of DSM-5 PTSD symptoms

Revisions in PTSD diagnosis have maintained researchers’ interest regarding its underlying structure. With the transition to DSM-5, four symptom clusters have replaced the traditional tripartite structure of PTSD symptoms (APA, Citation2013). Competing models have emerged from legitimate attempts to identify which model best represents the PTSD structure (Armour et al., Citation2016), yet it is unclear. Therefore, several key issues were identified: (1) the suboptimal fit of the 4-factor DSM-5 model as compared to alternative models; (2) limited evidence of alternative models, emphasizing the need for further research across different populations, which leads to (3) the lack of consensus regarding the optimal structure of PTSD symptoms.

The DSM-5 model (i.e. reexperiencing, avoidance, negative alterations in cognition and mood, hyperarousal), aligning with the Numbing Model (King et al., Citation1998), has received support in studies that have performed Confirmatory Factor Analyses (CFAs) on the PCL-5 (Krüger-Gottschalk et al., Citation2017; Liu et al., Citation2014; Van Praag et al., Citation2020), but shows poorer fit indices than alternative models, especially Anhedonia and Hybrid models (Bovin et al., Citation2016; Cheng et al., Citation2020; Di Tella et al., Citation2022). An overview of alternative models: the Dysphoria Model (Simms et al., Citation2002), combining markers of numbing and hyperarousal in a 4-factor structure; the 5-factor Dysphoric Arousal Model (Elhai et al., Citation2011), distinguishing between anxious and dysphoric arousal; the 6-factor Anhedonia Model (Liu et al., Citation2014), dividing the Negative Alterations in Cognitions and Mood (NACM) factor into negative affect and anhedonia clusters; the Externalizing Behavior Model (Tsai et al., Citation2015), proposing an externalizing behaviour factor (i.e. irritable or aggressive behaviour, self-destructive or reckless behaviour), and the 7-factor Hybrid Model (Armour et al., Citation2015), combining Anhedonia and Externalizing Behavior models.

Anhedonia and Externalizing Behavior models outperform Dysphoria, Dysphoric Arousal, and DSM-5 models (Ashbaugh et al., Citation2016; Hansen et al., Citation2023; Lee et al., Citation2020), with the Anhedonia Model displaying better indices than the Externalizing Behavior Model (Ito et al., Citation2019). The Hybrid Model, however, consistently demonstrates the best fit across studies (Blevins et al., Citation2015; Bovin et al., Citation2016; Carvalho et al., Citation2020; Hansen et al., Citation2023), despite criticisms regarding its complexity (Armour et al., Citation2016). Concerns about overly complex factor structures resulting from overreliance on goodness of fit indices include concerns about predictive validity, overfitting, and poor generalizability (Schmitt et al., Citation2018). A potential solution is to employ more complex statistical approaches, such as bifactor modelling on the PCL-5. Bifactor models aim to capture a general factor (‘general distress’) and orthogonal-specific factors to address shared and unique variances among observed items (Reise, Citation2012). Few studies on bifactor models of DSM-5 PTSD consistently support the presence of a general factor, surpassing correlated symptom models in fit (Byllesby et al., Citation2017; Law et al., Citation2019; Moring et al., Citation2019; Schmitt et al., Citation2018). Only one study examined a bifactor 7-factor model in the CFA framework (Di Tella et al., Citation2022), while Chen and colleagues (Citation2017) proposed an ESEM approach for the 7-factor bifactor model.

We address these gaps by examining the DSM-5 (4-factor), Anhedonia (6-factor), and Hybrid (7-factor) both as correlated symptom structures and bifactor models. summarizes existing CFA results on PCL-5 in different populations and summarizes the symptom mapping structure of the three factorial models.

Table 1. CFA Results on PCL-5 in Different Populations.

Table 2. Item Mapping for PTSD Structures.

1.2. The present study

Against this background, our study investigates (a) the psychometric properties and diagnostic utility of the Romanian version of PCL-5; (b) an optimal cut-off score (c) the latent structure of DSM-5 PTSD symptoms, including comparisons with literature models and bifactor modelling.

We anticipate the PCL-5 will demonstrate high internal consistency and provisional diagnostic utility. We also expect it to correlate positively with external depression, anxiety, stress (Bovin et al., Citation2016), and alexithymia (Evren et al., Citation2010), have a weaker to moderate positive correlation with dissociation, and an inverse correlation with resilience (Wortmann et al., Citation2016). Additionally, while we expect the Hybrid model to show the best fit, hypothesizing for bifactor modelling is challenging due to limited prior research.

2. Method

2.1. Procedure

The data sets were collected from two participant samples using an online survey created with Google Forms, a feature within Google Drive, and distributed through a commonly used communication channel among students. This approach employed a non-random sampling method, ensuring that the questionnaire was easily accessible. Participants were psychology students who voluntarily completed questionnaire for course bonus points and could withdraw anytime. Clinical interviews took place at the University of Bucharest, in a room appropriately set up for such purposes and were conducted by a team of clinical psychologists supervised and trained by the first two authors. The duration of the clinical interviews varied depending on the participants’ experiences and the range of symptoms discussed, typically lasting for one hour. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Bucharest.

2.2. Participants

2.2.1. Sample 1

The sample included 727 participants, including 628 females (86.38%) and 99 males (13.62%) aged 18–51 years (M = 21.2, SD = 5.07), mostly urban residents (98.5%). The participants were recruited from the Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, based on their availability, and the inclusion criteria were age above 18 years old and experienced at least one traumatic event in their lifetime. The average PCL-5 score was 26.2 (SD = 18.6, range: 0–80). Common traumatic events included the sudden loss of a loved one (38.92%), accident (32.57%), or physical attack (27.62%), and 62.85% of the participants experienced at least two traumatic events in their lifetime. This sample's data informed the PCL-5's internal consistency, validity (i.e. convergent, and discriminant), and CFAs.

2.2.2. Sample 2

Of the 727 trauma-exposed participants, 101 were assessed with the SCID-5-CV. Selection for interviews was based on PCL-5 responses, using algorithmic scoring to identify those meeting PTSD criteria according to this approach. Participants, who were contacted via e-mail and had previously been involved in the study, attended interviews voluntarily without compensation.

This sample included 93 females (92.08%) and eight males (7.92%), aged 18–47 years (M = 21.8, SD = 5.14). Of these, 34 (33.66%) were diagnosed with PTSD using SCID-5, with a average PCL-5 score of 40 (SD = 14.3, range: 15–73). Reported traumatic events included sexual abuse (24.75%), the sudden loss of a family member (17.82%), physical abuse (17.82%), physical abuse in the family (16.83%), severe accidents (14.85%), and physical injury or life-threatening conditions (6.94%). The data from this sample was used to test the diagnostic utility of the PCL-5.

All participants were briefly informed about the study's purpose before signing the informed consent, completed self-report questionnaires, and were kept blind about their diagnoses or PCL-5 scores.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Posttraumatic stress disorder

The PCL-5 (Weathers et al., Citation2013b) is a 20-item self-report questionnaire widely used to assess the severity of PTSD symptoms using a Likert scale, ranging from 0 to 4. Participants were asked to complete the questionnaire having the most stressful event in mind and rating each item according to how much they were bothered by specific symptoms during the past month. The PCL-5 has demonstrated strong psychometric properties in trauma-exposed undergraduate students (Blevins et al., Citation2015).

2.3.2. Lifetime exposure to trauma

Life Event Checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5; Weathers et al., Citation2013a) was used to assess lifetime exposure to trauma by presenting 16 possible traumatic events. LEC-5 is a tool through which participants can report different forms of exposure to the events they have experienced.

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Disorders, the Clinician Version (SCID-5-CV; First, Citation2015) was applied to 101 of the participants to assess the presence of a PTSD diagnosis. The SCID-5-CV has demonstrated good reliability and a high potential to minimize the false-negative, or false-positive diagnoses (sensitivity > 0.70, respectively specificity > 0.80) (Osório et al., Citation2019).

2.3.3. Depression, anxiety, stress

DASS-21 (Lovibond & Lovibond, Citation1995; Romanian version: Perţe & Albu, Citation2011) is a self-report instrument that assesses symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress, using a Likert scale, ranging from 0 to 3. The scores for each of the three scales are summed up to provide distinct assessments. Recent studies have provided robust psychometric evidence supporting the reliability and validity of the DASS-21 (Cao et al., Citation2023), including among college students (Chen et al., Citation2023).

2.3.4. Alexithymia

The 20-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20; Parker et al., Citation1993; Romanian version: Morariu et al., Citation2013) was used to measure alexithymia. This instrument comprises 20 items rated on a Likert scale, ranging from 1 to 5.

2.3.5. Dissociation

The Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES-II; Carlson & Putnam, Citation1993; Romanian version: Curșeu, Citation2006) consists of 28 statements that distinguish dissociative symptoms. Respondents select a percent frequency for each symptom on a 0–100% scale, increasing by 10%.

2.3.6. Resilience

The Resilience Scale (RS) developed by Wagnild and Young (Citation1993) was employed to measure resilience. This instrument consists of 25 items and is measured using a Likert scale, ranging from 1 to 7.

2.3.7. Translation

Translation-accurate procedures were applied to warrant the linguistic validity of the LEC-5, PCL-5, and Resilience Scale. First, two independent researchers, who were Romanian native speakers and had high English proficiency, undertook the forward translation. Afterward, the tools were back-translated by a bilingual English-Romanian clinical psychologist. Both translated versions were examined and refined until a consensus was reached concerning linguistic equivalence. After the backward translation, only a few adjustments were necessary regarding semantic accuracy. Furthermore, 30 voluntary participants blind about the study aim filled out the questionnaires to confirm the items’ coherence and clarity. These participants, with a mean age of 24.04 (SD = 6.48, range: 19–42), consisted of 11 males (36.67%) and 19 females (63.33%). Among them, 22 individuals (73.33%) completed high school and were current college students, five (16.67%) had obtained a Bachelor's degree, and three (10%) had completed their Master's degree.

2.4. Data analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using MedCalc software version 19.5.3 and the lavaan package (Rosseel, Citation2012) in R software (R Core Team, Citation2017). We reported descriptive statistics for PCL-5 scores and assessed internal consistency using McDonald's omega coefficient, a more flexible alternative to Cronbach's alpha for non-equal factor loadings (Hayes & Coutts, Citation2020). Pearson correlations evaluated external convergent (i.e. depression, anxiety, stress, alexithymia) and discriminant validity (i.e. resilience, dissociation).

Logistic regression analyzed the criterion validity of the PCL-5 in predicting SCID-5 diagnoses. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed using MedCalc software to assess diagnostic utility, using area under the curve (AUC) to indicate diagnostic accuracy. This included sensitivity (Sn), specificity (Sp), positive and negative likelihood ratios (±LR), positive and negative predictive values (±PV), overall efficiency and optimal cut-off score determination via Youden's J index (Youden, Citation1950). Additionally, ROC analysis for the PCL-5 symptom scoring method was conducted to compare its predictive accuracy for PTSD diagnoses against SCID-5, using only PCL-5 item responses and DSM-5 scoring.

CFAs were conducted using the function cfa in the lavaan package to examine the correlated symptom clusters models (e.g. DSM-5, Anhedonia, and Hybrid models). A chi-square difference test compared nested models (Satorra & Bentler, Citation2001). These models were respecified to incorporate a general factor for bifactor modelling, and correlations between the general factor and the specific factors were fixed to zero to meet the orthogonality assumption. Model assessment followed bifactor guidelines, using metrics like explained common variances (ECV), item-level explained common variances (IECV), omega hierarchical (ωH), and construct replicability (H). An ωH exceeding 0.80 indicated unidimensionality, and H values over 0.80 indicate well-defined latent variables (Reise, Citation2012).

The Maximum Likelihood (ML) estimator was used for both approaches, and the model fit was evaluated using the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR). Good fit was determined by CFI and TLI ≥ 0.90, RMSEA ≤ 0.06, and SRMR ≤ 0.08 (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999).

3. Results

3.1. Psychometric properties

Descriptive statistics, internal consistency, and correlations between variables are presented in . The PCL-5 and its subscales displayed excellent internal consistency coefficients ranging from .78 to .94. As expected, the results revealed evidence of good convergent and discriminant validity, as indicated by moderate to strong correlations with depression, anxiety, stress (range: .36 to .71), alexithymia (range: .33 to .55), small correlations with dissociation (range: .23 to .36), and negative correlations with resilience (range: −.16 to −.39).

Table 3. Descriptive Statistics, Internal Consistency, and Correlation Coefficients

3.2. Diagnostic utility

Logistic regression analysis revealed a significant association between PCL-5 total scores and SCID-5 diagnoses (χ2(1) = 16.1, p < .001), with an unstandardized regression coefficient of B = −.06 (SE = .01) and a correct classification rate of 75.2%. ROC curve analysis (see ) indicated an AUC of .75 (SE = .05), 95% CI = [.65–.83], suggesting acceptable overall accuracy (Hanley & McNeil, Citation1982). This led to the identification of an optimal cut-off score of >47, which maximizes sensitivity and specificity (Youden's J = .47), and having the highest overall efficiency (OE; Sn = 64.71, Sp = 82.09, OE = 74.11; see ).

Table 4. Diagnostic Utility Measures of the PCL-5 Against SCID-5 Diagnosis.

The PCL-5 symptom scoring method performed better within the ROC analysis, showing that PTSD prevalence is 72.3%, with an AUC of .91 (SE = .02). Based on this method, 85.15% (i.e. overall diagnostic efficiency) of the participants would be correctly classified (Sn = 86.30, Sp = 82.14). The recommended cut-off score is >33 (Sn = 86.3, Sp = 82.14, OE = 84.22).

3.3. Confirmatory factor analyses

CFAs were performed for three models of PTSD symptoms, which included the DSM-5 model, the Anhedonia model, and the Hybrid model. The DSM-5 4-factor model yielded marginally acceptable fit indices. Subsequently, when comparing nested models, it was determined that both the Anhedonia and Hybrid models exhibited superior fit compared to the DSM-5 Model. Specifically, in the comparison between nested Models 1 (DSM-5) and 2 (Anhedonia), Model 2 demonstrated a better fit. In the comparison between nested Models 3 (Hybrid) and 2 (Anhedonia), Model 3 displayed a better fit. CFA results are provided in .

Table 5. Goodness of Fit Indices for CFA and Bifactor Models.

3.4. Bifactor modeling

The DSM-5 bifactor model demonstrated superior fit over the correlated factors DSM-5 model, revealing a robust general PTSD construct that accounted for 78% of the total variance (ECV = .78; i.e. the proportion of variance explained by the general factor). The ωH and H were above .90 for the general factor, but not for specific factors, underscoring the robustness of a general PTSD construct. At the factor level, each factor exhibited substantial variance that was uniquely attributable to its associated items, with the highest ECV observed for the Avoidance factor, indicating that 42% of the variance in this factor can be attributed to the general factor. At the item level, the average IECV was .81 (range: .47 to .99), with the majority of items exceeding .70, supporting the bifactor model's validity.

Bifactor modelling was also applied to Anhedonia and Hybrid models. While fitting the data well, they did not outperform correlated symptom models. Both models showed convergence challenges, even after increasing the number of iterations, due to their complexity and limited items per factor. Consequently, the starting values were specified as NA, and a stable solution was found. The findings revealed a strong general factor in both models (ECVs = .77, and .71, respectively), with ωH and H values above .90 (and lower for specific factors), indicating reliability and unidimensionality. At the factor level, both bifactor models emphasize the strong connection of the Avoidance factor to the general PTSD construct (see ). Interestingly, our findings also suggest that besides Avoidance, other specific symptom clusters such as Anhedonia and Anxious Arousal in the Anhedonia Model, and Externalizing Behavior, Anxious Arousal and Dysphoric Arousal in the Hybrid Model, play pivotal roles in capturing the broader PTSD construct. At the item level, more than half of the items exceeded .80 for both models (average IECVs = .78, and .71, respectively).

4. Discussion

This study underscores the PCL-5's psychometric robustness, providing valuable insights for clinical and psychotherapeutic settings, and advancing research in these critical areas.

Our findings regarding the reliability properties of the PCL-5 as assessed by McDonald's omega are consistent with previous evidence, which similarly demonstrates excellent internal consistency for this instrument (Bovin et al., Citation2016; Garabiles et al., Citation2023; Lee et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, the results revealed evidence of convergent and discriminant validity. The intercorrelations of PCL-5 subscales ranged from moderate to high, indicating that they assess the same underlying construct without being entirely interchangeable. In line with our hypotheses, the total score and subscales of PCL-5 demonstrated good convergent validity with congruent external constructs (i.e. depression, anxiety, stress, and alexithymia), and discriminant validity with resilience (i.e. inverse correlation), and dissociation, as more distinct constructs.

The PCL-5 demonstrated good criterion validity with SCID-5, effectively predicting SCID-5 diagnoses. An optimal cut-off score of >47, determined by Youden's J index for maximizing sensitivity and specificity, proved most efficient, with 75% accuracy in diagnosis assignment. This finding aligns with previous results (Boysan et al., Citation2017; Roberts et al., Citation2021) that also identified similar cut-off scores suitable across populations. As in these findings, the diagnostic utility of the PCL-5 in the current study was moderate. The measure of diagnostic accuracy, namely the proportion of correctly classified cases, is in connection with the prevalence of the condition (Šimundić, Citation2009), sample characteristics, and severity of trauma exposure (Wilkins et al., Citation2011). Previous research proposes cut-off scores ranging between 31 and 48, but all these samples have rather heterogeneous characteristics. (Blevins et al., Citation2015; Krüger-Gottschalk et al., Citation2017; Pereira-Lima et al., Citation2019).

Furthermore, we found the DSM-5 algorithm-based symptom-scoring method more diagnostically efficient, which is consistent with previous findings (Krüger-Gottschalk et al., Citation2017). However, this result should be interpreted with caution. According to this method, 72.3% of the participants were potentially diagnosed with PTSD, a markedly higher prevalence compared to the 33.66% identified through the SCID-5 interviews. This discrepancy could be due to self-report biases or other methodological factors. The interview approach, being more conservative and relying on clinical judgment, may not identify cases that the symptom scoring method does.

Additionally, our study aimed to explore the PCL-5's latent structure using correlated symptom CFAs and bifactor modelling to assess DSM-5 4-factor Model, Anhedonia, and Hybrid models. Consistent with prior studies, we found acceptable fit indices for the DSM-5 Model (Di Tella et al., Citation2022; Orovou et al., Citation2021), but Anhedonia and Hybrid models fit the data better (Carvalho et al., Citation2020; Hansen et al., Citation2023). Notably, the bifactor DSM-5 model displayed superior fit indices, as previously demonstrated (Moring et al., Citation2019), and supported the importance of a general PTSD construct (Byllesby et al., Citation2017). Our bifactor metrics results closely matched Schmitt and colleagues (Citation2018), highlighting the statistical relevance of a bifactor 4-factor model. Additionally, a more in-depth analysis was conducted to explore specific factors as well, revealing that the Avoidance factor exhibited substantial commonality across symptom configurations, consistent with previous findings (Law et al., Citation2019).

Hence, there are some clinical implications within this study. First, examining this questionnaire against a gold-standard clinical interview emphasizes that the PCL-5 is a valuable assessment tool in making a provisional diagnosis. Second, identifying optimal cut-off scores can guide clinicians in their work. Third, the investigation of PTSD's latent structure responds to repeated attempts to determine how this disorder may be represented in terms of factor-based models. By highlighting the importance of the general PTSD construct, this research contributed to a more refined understanding of PTSD's nosology, offering valuable insights for guiding clinical and psychotherapeutic interventions.

4.1. Limitations and future directions

This study is not without limitations. The convenience sampling method and reliance on student participants, primarily female, may have introduced gender bias and limited sample diversity. This could be attributed to the data collection within the predominantly female Faculty of Psychology. A more diverse participant pool in future studies is essential for broader generalizability.

Additionally, the retrospective self-report of trauma exposure may lead to recall bias. Accurate assessment methods are needed to mitigate this issue. This study did not investigate test-retest reliability, essential for assessing psychometric properties. Further research, particularly for bifactor models, is necessary to more accurately determine PTSD's latent structure.

5. Conclusions

The current study provides empirical evidence for the clinical use of the PCL-5 and the latent structure of PTSD symptoms. It aimed to test the psychometric properties of the Romanian version of the PCL-5 and its diagnostic utility against a SCID-5 diagnosis on a sample of trauma-exposed undergraduates. The Romanian version of the PCL-5 has excellent psychometric properties and can be a significant measure of PTSD for clinicians and researchers. Additionally, our results highlight the good fit of the Anhedonia, Hybrid, and bifactor models. These findings emphasize the need to refine the current classification of PTSD symptoms, which might have significant implications in the field of trauma.

Ethics approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of the University of Bucharest (CEC no. 37/22.02.2019).

Authors contributions (CrediT Taxonomy)

Conceptualization: Teodora Georgescu, Cătălin Nedelcea, Claudiu Papasteri;

Methodology: Teodora Georgescu, Cătălin Nedelcea;

Data collection – Teodora Georgescu, Cătălin Nedelcea, Adrian Gorbănescu;

Formal analysis and investigation: Teodora Georgescu, Adrian Gorbănescu;

Writing – original draft and preparation: Teodora Georgescu;

Writing – review, and editing: Teodora Georgescu, Ana Cosmoiu, Ramona Letzner, Diana Vasile;

Project administration – Teodora Georgescu, Adrian Gorbănescu;

Supervision – Cătălin Nedelcea, Diana Vasile.

Acknowledgements

We would wish to thank Ruxandra Rădulescu, Cristina Turoșu, Ramona Bazâru, and Monica Șenchiu for their work in conducting the clinical interviews. Additionally, we are grateful to all participants for their essential role in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability

The datasets generated during and analyzed during the current study are available in the OSF repository: https://osf.io/6wam8/. Additional information is available upon request from the corresponding author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (1980). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (3rd ed.). American Psychiatric Association.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.

- Armour, C., Műllerová, J., & Elhai, J. D. (2016). A systematic literature review of PTSD's latent structure in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV to DSM-5. Clinical Psychology Review, 44, 60–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.12.003

- Armour, C., Tsai, J., Durham, T. A., Charak, R., Biehn, T. L., Elhai, J. D., & Pietrzak, R. H. (2015). Dimensional structure of DSM-5 posttraumatic stress symptoms: Support for a hybrid Anhedonia and Externalizing Behaviors model. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 61, 106–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.10.012

- Ashbaugh, A. R., Houle-Johnson, S., Herbert, C., El-Hage, W., & Brunet, A. (2016). Psychometric validation of the English and French versions of the posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). PLoS One, 11(10), e0161645. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0161645

- Benjet, C., Bromet, E., Karam, E. G., Kessler, R. C., McLaughlin, K. A., Ruscio, A. M., Shahly, V., Stein, D. J., Petukhova, M., Hill, E., Alonso, J., Atwoli, L., Bunting, B., Bruffaerts, R., Caldas-de-Almeida, J. M., de Girolamo, G., Florescu, S., Gureje, O., Huang, Y., … Koenen, K. C. (2016). The epidemiology of traumatic event exposure worldwide: Results from the World Mental Health Survey Consortium. Psychological Medicine, 46(2), 327–343. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291715001981

- Blevins, C. A., Weathers, F. W., Davis, M. T., Witte, T. K., & Domino, J. L. (2015). The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation: Posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(6), 489–498. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22059

- Bovin, M. J., Marx, B. P., Weathers, F. W., Gallagher, M. W., Rodriguez, P., Schnurr, P. P., & Keane, T. M. (2016). Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist for diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders–fifth edition (PCL-5) in veterans. Psychological Assessment, 28(11), 1379–1391. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000254

- Boysan, M., Guzel Ozdemir, P., Ozdemir, O., Selvi, Y., Yilmaz, E., & Kaya, N. (2017). Psychometric properties of the Turkish version of the PTSD checklist for diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition (PCL-5). Psychiatry and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 27(3), 300–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/24750573.2017.1342769

- Byllesby, B. M., Elhai, J. D., Tamburrino, M., Fine, T. H., Cohen, G., Sampson, L., Shirley, E., Chan, P. K., Liberzon, I., Galea, S., & Calabrese, J. R. (2017). General distress is more important than PTSD's cognition and mood alterations factor in accounting for PTSD and depression's comorbidity. Journal of Affective Disorders, 211, 118–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.01.014

- Cao, C. H., Liao, X. L., Jiang, X. Y., Li, X. D., Chen, I. H., & Lin, C. Y. (2023). Psychometric evaluation of the depression, anxiety, and stress scale-21 (DASS-21) among Chinese primary and middle school teachers. BMC Psychology, 11(1), 209. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01242-y

- Carlson, E. B., & Putnam, F. W. (1993). An update on the dissociative experiences scale. Dissociation: Progress in the Dissociative Disorders, 6(1), 16–27.

- Carvalho, T., Motta, C., & Pinto-Gouveia, J. (2020). Portuguese version of the posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Comparison of latent models and other psychometric analyses. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 76(7), 1267–1282. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22930

- Chen, C. M., Yoon, Y. H., Harford, T. C., & Grant, B. F. (2017). Dimensionality of DSM-5 posttraumatic stress disorder and its association with suicide attempts: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions-III. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52(6), 715–725. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-017-1374-0

- Chen, I. H., Chen, C. Y., Liao, X. L., Chen, X. M., Zheng, X., Tsai, Y. C., Lin, C. Y., Griffiths, M. D., & Pakpour, A. H. (2023). Psychometric properties of the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21) among different Chinese populations: A cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis. Acta Psychologica, 240, 1044042. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2023.104042

- Cheng, P., Xu, L. Z., Zheng, W. H., Ng, R. M., Zhang, L., Li, L. J., & Li, W. H. (2020). Psychometric property study of the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) in Chinese healthcare workers during the outbreak of corona virus disease 2019. Journal of Affective Disorders, 277, 368–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.038

- Curșeu, P. (2006). Scala de Experiente Disociative: Un Instrument de Evaluare a Simptomelor de Disociere. Cognition, Brain, Behavior – An Interdisciplinary Journal, 3(1–2).

- Di Tella, M., Romeo, A., Zara, G., Castelli, L., & Settanni, M. (2022). The post-traumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5: Psychometric properties of the Italian version. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(9), 5282. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095282

- Elhai, J. D., Biehn, T. L., Armour, C., Klopper, J. J., Frueh, B. C., & Palmieri, P. A. (2011). Evidence for a unique PTSD construct represented by PTSD's D1–D3 symptoms. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 25(3), 340–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.10.007

- Evren, C., Dalbudak, E., Cetin, R., Durkaya, M., & Evren, B. (2010). Relationship of alexithymia and temperament and character dimensions with lifetime post-traumatic stress disorder in male alcohol-dependent inpatients. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 64(2), 111–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1819.2009.02052

- First, M. B. (2015). Structured clinical interview for the DSM (SCID). In R. L. Cautin & S. O. Lilienfeld (Eds.), The encyclopedia of clinical psychology (pp. 1–6). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118625392.wbecp351.

- Forkus, S. R., Raudales, A. M., Rafiuddin, H. S., Weiss, N. H., Messman, B. A., & Contractor, A. A. (2023). The posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) checklist for DSM–5: A systematic review of existing psychometric evidence. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 30(1), 110–121. https://doi.org/10.1037/cps0000111

- Garabiles, M., Mordeno, I. G., & Nalipay, M. J. (2023). A comparison of DSM-5 and ICD-11 models of PTSD: Measurement invariance and psychometric validation in Filipino trauma samples. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 163, 24–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychires.2023.05.006

- Hanley, J. A., & McNeil, B. J. (1982). The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology, 143(1), 29–36. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiology.143.1.7063747

- Hansen, M., Vaegter, H. B., Lykkegaard Ravn, S., & Elmose Andersen, T. (2023). Validation of the Danish PTSD checklist for DSM-5 in trauma-exposed chronic pain patients using the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 14(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008066.2023.2179801

- Hayes, A. F., & Coutts, J. J. (2020). Use omega rather than Cronbach's alpha for estimating reliability. But … . Communication Methods and Measures, 14(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2020.1718629

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cut-off criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Ito, M., Takebayashi, Y., Suzuki, Y., & Horikoshi, M. (2019). Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5: Psychometric properties in a Japanese population. Journal of Affective Disorders, 247, 11–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.12.086

- King, D. W., Leskin, G. A., King, L. A., & Weathers, F. W. (1998). Confirmatory factor analysis of the clinician-administered PTSD Scale: Evidence for the dimensionality of posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Assessment, 10(2), 90–96. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.10.2.90

- Krüger-Gottschalk, A., Knaevelsrud, C., Rau, H., Dyer, A., Schäfer, I., Schellong, J., & Ehring, T. (2017). The German version of the posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Psychometric properties and diagnostic utility. BMC Psychiatry, 17(1), 379. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1541-6

- Law, K. C., Allan, N. P., Kolnogorova, K., & Stecker, T. (2019). An examination of PTSD symptoms and their effects on suicidal ideation and behavior in non-treatment seeking veterans. Psychiatry Research, 274, 12–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.02.004

- Lee, H., Aldwin, C. M., Kang, S., & Ku, X. (2020). Dimensionality and psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist-5 (PCL-5) among Korean Vietnam War Veterans. Military Behavioral Health, 9, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/21635781.2020.1776179

- Liu, P., Wang, L., Cao, C., Wang, R., Zhang, J., Zhang, B., Wu, Q., Zhang, H., Zhao, Z., Fan, G., & Elhai, J. D. (2014). The underlying dimensions of DSM-5 posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in an epidemiological sample of Chinese earthquake survivors. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 28(4), 345–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.03.008

- Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U

- Morariu, R. M., Ayearst, L. E., Taylor, G. J., & Bagby, R. M. (2013). The development of a Romanian version of the 20-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20-Ro). Romanian Journal of Psychiatry, 15(3), 155–158.

- Moring, J. C., Nason, E., Hale, W. J., Wachen, J. S., Dondanville, K. A., Straud, C., Moore, B. A., Mintz, J., Litz, B. T., Yarvis, J. S., & Young-McCaughan, S. (2019). Conceptualizing comorbid PTSD and depression among treatment-seeking, active duty military service members. Journal of Affective Disorders, 256, 541–549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.06.039

- Orovou, E., Theodoropoulou, I. M., & Antoniou, E. (2021). Psychometric properties of the post traumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) in Greek women after cesarean section. PLoS One, 16(8), e0255689. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255689

- Osório, F. L., Loureiro, S. R., Hallak, J. E. C., Machado-de-Sousa, J. P., Ushirohira, J. M., Baes, C. V. W., Apolinario, T. D., Donadon, M. F., Bolsoni, L. M., Guimarães, T., Fracon, V. S., Silva-Rodrigues, A. P. C., Pizeta, F. A., Souza, R. M., Sanches, R. F., dos Santos, R. G., Martin-Santos, R., & Crippa, J. A. S. (2019). Clinical validity and intrarater and test–retest reliability of the structured clinical interview for DSM-5 – clinician version (SCID-5-CV). Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 73(12), 754–760. https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.12931

- Parker, J. D. A., Michael Bagby, R., Taylor, G. J., Endler, N. S., & Schmitz, P. (1993). Factorial validity of the 20-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale. European Journal of Personality, 7(4), 221–232. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2410070403

- Pereira-Lima, K., Loureiro, S. R., Bolsoni, L. M., Apolinario da Silva, T. D., & Osório, F. L. (2019). Psychometric properties and diagnostic utility of a Brazilian version of the PCL-5 (complete and abbreviated versions). European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1581020. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2019.1581020

- Perţe, A., & Albu, M. (2011). Adaptarea şi standardizarea pe populaţia din România. DASS-Manual pentru Scalele depresie, anxietate şi stres, Editura ASCR.

- Reise, S. P. (2012). The rediscovery of bifactor measurement models. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 47(5), 667–696. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2012.715555

- Roberts, N. P., Kitchiner, N. J., Lewis, C. E., Downes, A. J., & Bisson, J. I. (2021). Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 in a sample of trauma exposed mental health service users. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1863578. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2020.1863578

- Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. http://hdl.handle.net/1854/LU-3099674.

- Satorra, A., & Bentler, P. M. (2001). A scaled difference chi-square test statistic for moment structure analysis. Psychometrika, 66(4), 507–514. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02296192

- Schmitt, T. A., Sass, D. A., Chappelle, W., & Thompson, W. (2018). Selecting the “best” factor structure and moving measurement validation forward: An illustration. Journal of Personality Assessment, 100(4), 345–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2018.1449116

- Simms, L. J., Watson, D., & Doebbelling, B. N. (2002). Confirmatory factor analyses of posttraumatic stress symptoms in deployed and nondeployed veterans of the Gulf War. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 111(4), 637–647. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.111.4.637

- Stanley, I. H., Tock, J. L., Boffa, J. W., Hom, M. A., & Joiner, T. E. (2023). Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) anchored to one's own suicide attempt. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 16, 425–434. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0001456

- Šimundić, A.-M. (2009). Measures of diagnostic accuracy: Basic definitions. EJIFCC, 19(4), 203–211. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4975285/.

- Team, R. C. (2017). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

- Tsai, J., Harpaz-Rotem, I., Armour, C., Southwick, S. M., Krystal, J. H., & Pietrzak, R. H. (2015). Dimensional structure of DSM-5 posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms: Results from the national health and resilience in veterans study. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 76(05), 546–553. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.14m09091

- Van Praag, D. L., Fardzadeh, H. E., Covic, A., Maas, A. I., & von Steinbüchel, N. (2020). Preliminary validation of the Dutch version of the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) after traumatic brain injury in a civilian population. PLoS One, 15(4), e0231857. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231857

- Wagnild, G. M., & Young, H. M. (1993). Development and psychometric. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 1(2), 165–17847.

- Weathers, F. W., Blake, D. D., Schnurr, P. P., Kaloupek, D. G., Marx, B. P., & Keane, T. M. (2013a). The life events checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5). Instrument available from the National Center for PTSD at www.ptsd.va.gov.

- Weathers, F. W., Bovin, M. J., Lee, D. J., Sloan, D. M., Schnurr, P. P., Kaloupek, D. G., Keane, T. M., & Marx, B. P. (2018). The Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM–5 (CAPS-5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation in military veterans. Psychological Assessment, 30(3), 383–395. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000486

- Weathers, F. W., Litz, B. T., Keane, T. M., Palmieri, P. A., Marx, B. P., & Schnurr, P. P. (2013b). The PTSD checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). Scale Available from the National Center for PTSD at Www.Ptsd.va.Gov, 10.

- Wilkins, K. C., Lang, A. J., & Norman, S. B. (2011). Synthesis of the psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist (PCL) military, civilian, and specific versions. Depression and Anxiety, 28(7), 596–606. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20837

- Wortmann, J. H., Jordan, A. H., Weathers, F. W., Resick, P. A., Dondanville, K. A., Hall-Clark, B., Foa, E. B., Young-McCaughan, S., Yarvis, J. S., Hembree, E. A., & Mintz, J. (2016). Psychometric analysis of the PTSD Checklist-5 (PCL-5) among treatment-seeking military service members. Psychological Assessment, 28(11), 1392–1403. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000260

- Youden, W. J. (1950). Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer, 3(1), 32–35. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(1950)3:1<32::AID-CNCR2820030106>3.0.CO;2-3