ABSTRACT

The purpose of this review was to identify, characterize, and map the existing knowledge on a) nurses’ and pharmacists’ perceived barriers and enablers to addressing vaccine hesitancy among patients; and b) strategies or interventions for nurses and pharmacists to address vaccine hesitancy in their practice. Our comprehensive search strategy targeted peer-reviewed and grey literature. Two independent reviewers screened papers and extracted data. We coded narrative descriptions of barriers and enablers and interventions using the Behavior Change Wheel. Sixty-six records were included in our review. Reported barriers (n = 9) and facilitators (n = 6) were identified in the capability, opportunity and motivation components. The majority of the reported interventions were categorized as education (n = 47) and training (n = 26). This current scoping review offers a detailed behavioral analysis of known barriers and enablers for nurses and pharmacists to address vaccine hesitancy and interventions mapped onto these behavioral determinants.

Introduction

Immunizations are considered one of the greatest public health achievements of the 20th century,Citation1,Citation2 preventing two to three million deaths globally per year. Despite the success of immunization programs,Citation3 vaccine acceptance has often been met with varying levels of vaccine resistance or hesitancy.Citation4 Vaccine hesitancy is defined as a delay in acceptance or refusal to vaccinate despite the availability of vaccines.Citation5 Vaccine hesitancy is believed to be responsible for decreases in vaccine coverage and increased outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases.Citation6 In fact, the World Health Organization (WHO) identified vaccine hesitancy as one of the biggest threats to global health in 2019;Citation2 the threat that global vaccine hesitancy has on herd immunity can cause significant, negative public health outcomes.Citation1 This is particularly concerning given the current COVID-19 pandemic and variants of concern; mass vaccination of the general public will be needed to contain and prevent future spread of COVID-19. In order to create herd immunity for the population, it is expected that the COVID-19 vaccine will need to be accepted by a vast majority of the population in Canada, with some estimates expecting at least 85% depending on the country and infection rate.Citation7,Citation8 To effectively combat COVID-19 and other vaccine-preventable diseases, effective strategies are needed to counter vaccine hesitancy.

Health-care providers are well situated in health systems to address vaccine-related concerns and hesitancy. Nurses and pharmacists, in particular, often have more dedicated time to talk with concerned individuals or parents of children prior to vaccine administration, compared to physicians and other health-care providers.Citation9 Multiple strategies and interventions have been employed to address vaccine hesitancy and, therefore, increase vaccine uptake, including provider-based interventions.Citation10 Of the known provider-based interventions, there is a range of techniques used, from informative conversations about vaccines with patients and/or parents,Citation11,Citation12 the use of prevalence statistics to educate patients and/or parents,Citation13 and practicing empathetic communication.Citation14 These interventions have been shown to be effective techniques in shifting vaccine hesitant patients and/or parents to vaccine acceptors.Citation11–14

Despite these evidence-based interventions to address vaccine hesitancy, little is known about how provider-based interventions are implemented into nurses’ and pharmacists’ practice in the community and hospital setting. In health care, more broadly, studies have shown that barriers at the individual, interpersonal, organizational, and system levels can significantly hinder the implementation of effective health-care interventions into practice.Citation15 However, it is unclear what barriers and enablers affect nurses’ and pharmacists’ ability to address vaccine hesitancy and/or refusal among their patients. Further, it is not known how existing interventions target known barriers and utilize enablers to change, if at all. Research efforts should aim to clearly understand the barriers and enablers in order to tailor interventions to support nurses’ and pharmacists’ ability to address vaccine hesitancy and/or refusal.

As such, adopting a systematic, theory-informed approach is needed to 1) identify barriers and enablers to addressing vaccine hesitancy and/or refusal at multiple levels (i.e., individual, social, cultural, political, etc.) and 2) design implementation strategies to overcome these barriers and enhance the enablers to address vaccine hesitancy. To target barriers and enablers to addressing vaccine hesitancy, a theory-based analysis is needed to better understand the relationship between these factors, and the mechanisms in which they influence behavior.Citation16 Studies have found that the use of theory-based approaches to behavior change can lead to more successful implementation and intervention success.Citation17,Citation18

Research purpose

The purpose of this scoping review was to identify, characterize, and map the existing knowledge on a) nurses’ and pharmacists’ perceived barriers and enablers to addressing vaccine hesitancy among patients; and b) strategies or interventions for nurses and pharmacists to address vaccine hesitancy in their practice. Findings from this review will inform the design of behavioral interventions to support nurses’ and pharmacists’ practice in addressing vaccine hesitancy among their patients.

Review question(s)

What are nurses’ and pharmacists’ perceived barriers and enablers to addressing vaccine hesitancy and/or refusal among patients and/or the general public?

How do the barriers and enablers map onto the COM-B Model?

What strategies exist for nurses and pharmacists to address vaccine hesitancy and/or refusal among patients and/or the general public?

How do the strategies map onto the Behavior Change Wheel?

Inclusion criteria

Participants

This review considered literature that included nurses (licensed practical nurses, registered nurses, nurse practitioners, nursing students) and/or pharmacists, including pharmacy students and pharmacy technicians, as participants.

Concept

We included literature that explored perceived barriers and enablers reported by nurses and/or pharmacists to address vaccine hesitancy and/or refusal among patients, families, or the general public. For this review, an enabler is defined as “a person or thing that makes something possible,”Citation19 whereas a barrier is defined as “a circumstance or obstacle that keeps people or things apart or prevents communication or progress.”Citation20

This review focused on strategies or interventions that have been implemented and/or evaluated to support nurses and/or pharmacists to address vaccine hesitancy and/or refusal among patients, families, or the general public. Strategies or interventions refer to processes, methods, or tools that were implemented or evaluated to promote or improve nurses’ and pharmacists’ ability to address vaccine hesitancy and/or refusal.

Context

This review considered studies located in any care setting, including hospital, community, primary care, ambulatory care settings, and long-term care. To maintain a focused scope of review, studies were limited to countries with similar approaches to health care (i.e., Canada, United States, United Kingdom, Europe, New Zealand, and Australia).Citation21,Citation22

Types of sources

This scoping review considered both experimental and quasi-experimental study designs including randomized controlled trials, non-randomized controlled trials, before and after studies and interrupted time-series studies. In addition, analytical observational studies including prospective and retrospective cohort studies, case-control studies and analytical cross-sectional studies will be considered for inclusion. This review also considered descriptive observational study designs, including case series, individual case reports, and descriptive cross-sectional studies for inclusion.

Qualitative studies were also considered that focused on qualitative data including, but not limited to, designs such as phenomenology, grounded theory, ethnography, qualitative description, action research, and feminist research.

Systematic reviews that report on aspects of nurses’ and pharmacists’ role in addressing vaccine hesitancy were reviewed for primary studies that may meet the eligibility criteria.

Text and opinion papers, as well as other published materials including case studies and relevant academic publications, such as theses and dissertations, were also considered for inclusion. Official websites of public health organizations in the aforementioned geographic regions and health-care provider associations were used, together with white papers, reports, position papers, and policy papers, relevant to governmental guidance. Only studies published in English were included. No date restriction was implemented to allow for the observation of any trends or changes in vaccine hesitancy over time to be captured.

Methods

This review was conducted in accordance with the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodology for scoping reviews.Citation23 JBI is an international research organization focused on Health and Medical Science evidence synthesis to improve health-care practices and health outcomes. There was no patient or public involvement in the design, conduct, reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Search strategy

The search strategy was developed with a JBI-trained medical research librarian scientist and aimed to locate published empirical studies and grey literature. The scoping review followed the three-step, iterative process in accordance with the JBI Scoping Review Methodology.Citation24 The three steps include 1) an initial limited search of at least two appropriate online databases relevant to the topic (MEDLINE and CINAHL), followed by an analysis of the text words contained in the title and abstract of retrieved papers and of the index terms used to describe the articles, 2) a second search using all identified keywords and index terms, and 3) searching the reference list of all identified reports and articles for any additional sources. The search strategy aimed to identify both published primary studies, reviews, and text and opinion papers.

Information sources

The databases searched include MEDLINE, CINAHL, EMBASE, Web of Science, and PsycInfo. Sources of unpublished studies and grey literature were searched using ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global and the first 10 pages of Google Scholar. We also searched for grey literature using the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health grey literature checklist Grey Matters: a practical tool for searching health-related grey literature.Citation25 Relevant organizational, governmental, and health-care association websites were reviewed including, Children’s Healthcare Canada, Canadian Nurses Association, Canadian Pharmacists Association, National Association of Pharmacy Regulatory Authorities, American Academy of Pediatrics, American Pharmacists Association, Canadian Pediatric Society, Immunize Canada, Canadian Immunization Research Network, Public Health Agency of Canada, Infection Prevention and Control, Royal College of Pediatrics and Child Health, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, American Nurses Association, American Pharmacists Association, Australian Nursing and Midwifery Association, Pharmacy Board of Australia, British Nursing Association.

Study selection

Following the search, all identified records were collated and uploaded to Covidence,Citation26 a citation management platform, and duplicates were removed. Two of three independent reviewers (JL, HG & LS) screened the titles and abstracts against the inclusion criteria for the review. Potentially relevant papers were retrieved in full, and their citation details imported into Covidence. Next, two of four independent reviewers (JL, HG, LD & RD) assessed the full text of selected citations in detail against the inclusion criteria. Reasons for exclusion of full-text papers were recorded and reported. Any disagreements that arose between the reviewers at each stage of the selection process were resolved through discussion or with a third reviewer (CC).

Data extraction

Data were extracted from included studies by two independent reviewers using a data extraction tool developed by the research team (see Supplemental file 2). Study information extracted included author(s), year of publication, country of origin, study aim/purpose, study population, study setting, design, outcome measures, barriers, enablers, description of strategies/interventions, reported key findings, and implications. The draft data extraction tool was piloted on five studies by two reviewers. After pilot testing, three additional items were included in the tool; population to be vaccinated, vaccine type, and study limitations. Any disagreements that arose between the reviewers were resolved through discussion or with a third reviewer.

Data synthesis and analysis

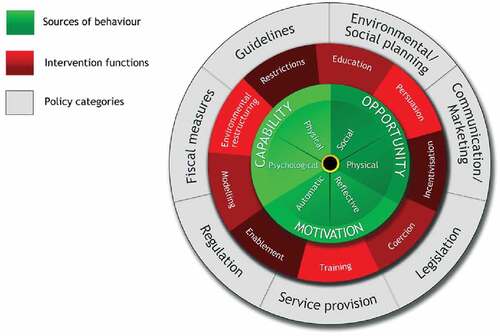

All data were combined to provide one complete dataset for analysis and cleaned by one reviewer (JL). Data on strategies/interventions and barriers/enablers were analyzed using the Behavior Change Wheel (BCW) as a coding guide. The BCW is a synthesis of 19 existing behavior change frameworks that offers a comprehensive and systematic guide to designing interventions.Citation27 The BCW (see ) includes an analysis of the nature of behavior, the mechanisms that need to be addressed in order to create behavior change, and the interventions and policies required to change these mechanisms. The BCW uses the COM-B model, which proposes that one needs Capability (C), Opportunity (O), and Motivation (M) to perform a Behavior (-B), to obtain a better understanding of the behavior in context, which is known as a behavioral analysis.Citation27 The BCW also includes nine intervention functions that are likely to be effective in bringing about behavior change in each COM-B domain.Citation27 An intervention function is defined as the function most likely to be effective in changing a particular target behaviorCitation27The BCW’s behavioral analysis is an important first step in designing and implementing theory-informed interventions. To our knowledge, this type of behavioral analysis has not been conducted in the context of nurses’ and pharmacists’ role in addressing vaccine hesitancy and/or refusal among patients.

First, we conducted a behavioral analysis of nurses’ and pharmacists’ perceived enablers and barriers to addressing vaccine hesitancy. One reviewer categorized the extracted barriers and enablers into the six sub-components of the COM-B Model of behavior: (psychological capability, physical capability, social opportunity, physical opportunity, automatic motivation, and reflective motivation (). Barriers and enablers can be categorized into multiple sub-components. A second reviewer (CC) verified all coded data. Next, the primary reviewer (JL) examined the data further and inductively generated themes on similar statements that represent the barriers and enablers within each COM-B component. All inductive codes were verified and approved by the second reviewer (CC). Discussion between the reviewers (CC & JL) was consistent throughout all steps. We presented the preliminary themes to the research team for refinement.

Second, we classified the strategies/interventions aimed at addressing vaccine hesitancy according to the BCW’s nine intervention functions (education, training, modeling, enablement, environmental restructuring, persuasion, restrictions, coercion, incentivization) (). An intervention could be classified into one or more intervention function. One reviewer conducted the data classification using a pre-defined coding manual based on definitions and guidance from the BCW.Citation27 A second reviewer verified all data classification. Final BCW categorizations were reviewed and discussed with the entire research team. Given the focus of this scoping review on mapping existing literature, we did not explicitly perform a risk of bias assessment.

The extracted data were presented in a tabular form that aligns with the study’s objective. Results were classified under the main conceptual categories: study characteristics (including country of origin, study population, population to be vaccinated, vaccine type, study setting, design); outcome measures; barriers; enablers; strategies/interventions; reported key findings; and implications. The PRISMA-ScRCitation28 reporting guidelines were followed for reporting of this scoping review.

Results

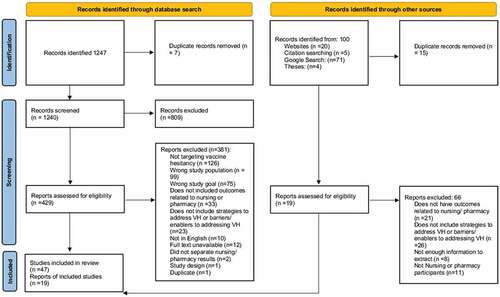

We identified 1247 records through our database search and 100 through additional sources (e.g. grey literature). Following title and abstract screening and full-text review against the eligibility criteria, a total of 66 records were identified that met inclusion criteria and were included in this review. See for the PRISMA flow chart and for characteristics of included citations. The majority of the included records were conducted in the United States (US) (n = 43) and employed a variety of research designs including reviews (mixed, integrative, systematic, literature) (n = 10), qualitative (n = 9) and informative/descriptive (n = 9). A majority of the studies were published after 2015 (n = 52), with 16 identified articles published in 2019 alone. The settings included primary care (n = 12), pharmacies (n = 10), and schools (n = 8). The most frequently targeted population to be vaccinated was children (n = 10), followed by the general population (n = 6); 20 did not specifically state the target population. The majority did not clearly state a specific vaccine (n = 47), while some focused on HPV (n = 7) and influenza (n = 5). Most were conducted with nurses (n = 49), including nurse practitioners (n = 6), school nurses (n = 4) and pediatric nurses (n = 4). Seventeen were conducted with pharmacists but did not differentiate the setting in which the pharmacist worked.

Table 1. Characteristics of included records

Barriers for nurses and pharmacists to address vaccine hesitancy

We identified nine themes related to barriers for nurses and pharmacists to address vaccine hesitancy among patients, parents, or the public. Reported barriers and corresponding COM-B Model of Behavior mapping are outlined in . The most commonly reported barrier for both nurses and pharmacists was that patients and/or parents were misinformed about vaccinations (n = 29 nursing focused papers and n = 6 pharmacy focused papers). In both nursing and pharmacy focused papers, the next two most commonly reported barriers were the lack of communication aid/guidance (n = 18, n = 4, respectively) and addressing patient mistrust in the system (n = 10, n = 5, respectively).

Table 2. Reported barriers to addressing vaccine hesitancy

Capability

Lack of understanding of vaccine hesitancy. A key barrier was a lack of provider understanding of the definition of vaccine hesitancy. The papers described provider confusion on the differences between vaccine hesitancy and anti-vaccination.

Capability and opportunity

Lack of communication aids and guidelines

A common barrier for nurses and pharmacists was the lack of communication aids (i.e., posters, pamphlets, and brochures) and guidelines for providers to reference and support the conversation with vaccine hesitant patients. Studies reported no clear guidelines for providers to communicate effectively with vaccine hesitant patients and/or parents as most resources focused on the evidence about the effectiveness and safety of vaccines and not strategies to address hesitancy.

Health-care provider–patient relationship

A key barrier identified was the relationship nurses and pharmacists had with their patients. Patients felt like they were unable to discuss their concerns with health-care providers, due to fear of dismissal and judgment. Further, studies reported that if there was a lack of trust between patients and health-care providers, nurses and pharmacists lacked the ability/confidence to discuss sensitive subjects, such as fear of vaccines.

Lack of time to address vaccine hesitancy

Nurses reported having limited time to address vaccine hesitancy with their patients. Studies described that other health issues were often prioritized and/or appointment times were limited to one or two topics. Pharmacists did not report time constraints as a barrier to addressing vaccine hesitancy in the included studies.

Opportunity

Lack of opportunities to discuss vaccine hesitancy

Nursing-related studies identified a lack of nurse–patient interactions to discuss vaccine hesitancy. Studies reported that there was not always an opportunity to facilitate this discussion, especially if patients were healthy and not presenting to the clinic. As a result, patients were often not given the opportunity to express their vaccine concerns with a trusted health-care provider.

Health-care provider collaboration

Studies reported that nurses and pharmacists identified a lack of health-care provider collaboration, among nurses, pharmacists, physicians, and public health, when addressing vaccine hesitancy as a key barrier to success.

Opportunity and motivation

Patients are misinformed about vaccinations

A common barrier identified by both nurses and pharmacists was difficulty in addressing patients’ hesitancy that resulted from the patient being misinformed about vaccines. Patients and/or parents often present to appointments with emotional anecdotal stories that include nonscientific information, that counter the known facts about vaccine effectiveness. It is challenging for nurses and pharmacists to counter misinformation that is highly emotional.

Patients have a mistrust in the system

A key barrier for nurses and pharmacists to address vaccine hesitancy was patients having a mistrust in the health-care system and individual providers finding it hard to regain that trust. Patients in several studies reported a lack of trust in government and the health-care system. Nurses and pharmacists identified significant barriers in overcoming patients’ mistrust in the health-care system as discussing patients’ mistrust in government does not fall under the “job description” or is seen as more of a public health issue.

Influence of social media

Several studies described the role of social media on nurses’ and pharmacists’ ability to address vaccine hesitancy. Patients are significantly influenced by what they consume via social media. As a result, nurses and pharmacists reported feeling helpless when attempting to address misconceptions and myths about vaccines.

Enablers for nurses and pharmacists to address vaccine hesitancy

We identified six themes related to enablers for nurses and pharmacists to address vaccine hesitancy among patients, parents, or the public. Reported enablers and corresponding COM-B Model of Behavior mapping is outlined in . In both nursing and pharmacy focused studies, the most commonly reported enablers were the availability and dissemination of resources to support education (n = 29 nursing focused papers, and n = 7 pharmacy focused papers) and health-care provider–patient relationship (n = 25 and n = 6, respectively).

Table 3. Reported enablers to addressing vaccine hesitancy

Capability and opportunity

Availability and dissemination of resources to support education

Nurses and pharmacists expressed the need to educate their patients to help shift patients from hesitant to acceptant. Studies described easy access of information to give to patients and health-care providers as an important enabler to addressing vaccine hesitancy. Nurses and pharmacists can use these accessible resources (e.g., pamphlets and posters) to facilitate a conversation on vaccine hesitancy, educate patients on vaccines, and support informed decision-making.

Opportunity

Reminder system for health-care providers

Nurses described a key enabler to be a reminder system to discuss vaccinations during visits prior to scheduled vaccination appointments. In doing so, nurses were able to provide resources to patients and parents and have time to discuss concerns.

Opportunity and motivation

Health-care provider–patient relationship

Nurses and pharmacists noted the importance of having a strong relationship with their patients to help build trust to discuss vaccines in an effective manner. This was particularly relevant in the primary care and school settings. Nurses and pharmacists also noted that the time they were able to give to patients helped establish this trust to a greater extent.

Agreement on a revised schedule

For patients with higher levels of vaccine hesitancy, nurses found it beneficial to formulate an agreed upon vaccination schedule so there was not as many vaccinations given at once, or were more spaced out, it is crucial that this is well-documented among all health-care providers. This approach ensures that vaccinations are still administered, and patients feel involved in the vaccination process. This was not reported as an enabler for pharmacists.

Collaborative practice to support vaccine acceptance

Nurses and pharmacists noted the importance of interprofessional collaboration to address vaccine hesitancy. This included collaborating with physicians, public health, and other health-care professionals to create a clear and consistent message to support vaccine uptake.

Motivation

Health-care providers identity and role in addressing vaccine hesitancy

Nurses noted that their role and identity as nurses helped them to form strong relationships with their patients. Studies described the professional identity as a motivator for addressing vaccine hesitancy and facilitating the uptake of vaccinations.

Interventions for nurses and pharmacists to address vaccine hesitancy

In this review, 58 out of the 66 records reported strategies or interventions to facilitate nurses or pharmacists to address vaccine hesitancy. We characterized the reported interventions using the BCW’s intervention function categories. The frequency of BCW intervention functions include: Education (n = 47), Training (n = 26), Persuasion (n = 16), Enablement (n = 8), Environmental Restructuring (n = 3), and Modeling (n = 2). As shown in , interventions were multicomponent and consisted of a variety of different combinations of BCW intervention functions. Most commonly, Education and Training together comprised 16 different interventions. describes examples of reported interventions in the following four categories: 1) Communication tools/guidelines to educate patients, 2) Strategies for open communication with patients, 3) Educational workshops, and 4) Social Support.

Table 4. Reported interventions and corresponding intervention functions

Discussion

Summary of evidence

This scoping review aimed to identify, characterize, and map the existing knowledge on a) nurses’ and pharmacists’ perceived barriers and enablers to addressing vaccine hesitancy among patients and b) strategies or interventions for nurses and pharmacists to address vaccine hesitancy in their practice. We identified 66 records that described barriers and enablers for nurses and pharmacists to address vaccine hesitancy in practice and existing strategies/interventions that nurses and pharmacists use to address vaccine hesitancy with their patients. In this review, we mapped the reported barriers and enablers to addressing vaccine hesitancy onto the COM-B Model of Behavior and interventions onto the BCW’s intervention functions. These frameworks enabled a comprehensive behavioral analysis of nurses’ and pharmacists’ capability, opportunity, and motivation to address vaccine hesitancy among their patients. Reported barriers included a lack of understanding of vaccine hesitancy (capability), provider–patient relationship (opportunity), and patients being misinformed about vaccines (motivation). Reported enablers included having availability of resources to support education (capability), open communication with patients and/or parents (opportunity), and having a collaborative practice to support vaccine acceptance (opportunity, motivation). Interventions ranged from creating a more inclusive environment to educating providers on how to talk to vaccine hesitant patients. Based on this behavioral analysis, future research can use our findings to select and tailor interventions to address the behavioral determinants related to vaccine hesitancy for a range of immunization programs, including COVID-19 vaccines.

Capability

Our findings highlight the influence of nurses’ and pharmacists’ capabilities on addressing vaccine hesitancy. According to the BCW, capability is defined as an individual’s psychological and physical ability to engage in a behavior of interest (i.e., addressing vaccine hesitancy).Citation27 This scoping review identified several barriers and enablers related to nurses’ and pharmacists’ psychological and physical skills to address vaccine hesitancy.

First, included studies reported that nurses and pharmacists had a lack of understanding of vaccine hesitancy. Previous research highlights that most health-care providers do not receive training on vaccine hesitancy.Citation11,Citation77,Citation95,Citation96 The majority of interventions identified in this scoping review included an education and/or training intervention function (n = 73), including communication aids, guides, and tools to support nurses and pharmacists to address vaccine hesitancy.Citation31,Citation43,Citation46,Citation61,Citation66,Citation83,Citation85,Citation97 According to the BCW, these types of educational interventions are effective at addressing capability-related barriers,Citation18 including nurses’ and pharmacists’ lack of understanding of vaccine hesitancy and patients’ misinformation on vaccinations. However, despite the availability of these interventions, our review identified that barriers still hinder their utility in practice. Improved implementation efforts of education and training components are needed to support the use of vaccine hesitancy communication aids and tools in nursing and pharmacy practice. For example, previous research has shown simulation training to be an effective mechanism for health-care provider students to develop their knowledge, skills, attitudes, and beliefs related to vaccination practice.Citation91,Citation98 Previous work has been conducted with medical students to develop simulation interventions to address vaccine hesitancy;Citation99 however, there is limited evidence on the use of simulation with vaccine hesitancy or the necessary components needed for nursing and pharmacy students.Citation91,Citation100 Future research might benefit from further development of vaccine hesitancy educational interventions for nursing and pharmacy students.

Opportunity & motivation

Intersecting barriers and enablers within opportunity and motivation appear to play the most impactful role on nurses’ and pharmacists’ ability to address vaccine hesitancy. Opportunity refers to social and environmental factors external to an individual that either positively or negatively facilitate or prompt a particular behavior,Citation27 whereas motivation is defined as the brain processes that enact or inhibit behavior.Citation27 In this review, the literature highlighted the critical role of a trusting patient–health-care provider relationship on vaccine acceptance. Previous research has identified nurses and pharmacists as trusted health-care providers as they are uniquely situated within the health-care system to have discussions with patients about health concerns.Citation101 However, despite the trustworthiness of nurses and pharmacists, this review identified several barriers related to external social influence on patients, including their mistrust in the health-care system, misinformation about vaccines, and the impact of social media on vaccine hesitancy. With patients having unlimited access to information via the internet, providers may find it challenging to address concerns from anti-vaccination groups or anecdotal stories from friends and families. Previous research refers to the “informed opposition” patients, in which individuals have done excessive research on poor outcomes related to vaccines.Citation53,Citation102,Citation103 These social influences make it challenging for nurses and pharmacists to develop a trusting relationship and effectively address vaccine hesitancy with their patients. Contrarily, as this review identified, nurses and pharmacists can use their own social influence as an enabler to positively affect change. There are opportunities to leverage known trust and credibility among nurses and pharmacists as a facilitator to promote vaccine acceptance.

Although we identified many education and training interventions, fewer interventions exist for opportunity- and motivation-related barriers and enablers, including patients’ mistrust and the influence of social media. With the BCW intervention function mapping, we identified only 16 persuasion interventions and eight enablement interventions. Previous behavioral science research has shown that persuasion and enablement-type interventions are effective at addressing behavioral determinants related to opportunity and motivation.Citation18 In the vaccine hesitancy context, persuasion and enablement interventions include providers maintaining an open dialogue with patients by exploring what works best for them, sharing personal stories, humanizing or adding emotion to the information shared, using motivational interviewing techniques, or having an empathetic discussion.Citation35,Citation66,Citation67,Citation85,Citation92 These types of behavioral interventions are urgently needed to combat vaccine hesitancy, especially given the current state of the COVID-19 pandemic. Although vaccine development, production, and distribution have been at the forefront of this pandemic, deployment efforts can be hampered by vaccine hesitancy. This will have significant impacts on achieving herd immunity and bringing the pandemic under control globally.Citation104 Social media movements, such as #ScienceUpFirst in Canada, have been developed to address the spread of COVID-19 misinformation online. This is a valuable example of a persuasion and enablement intervention that nurses and pharmacists can participate in to address COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among the public.Citation105 In future intervention design work for COVID-19 vaccinations and other immunization programs, more broadly, tailored efforts are needed to include persuasion and enablement intervention functions, along with education and training strategies, to effectively target capability, opportunity, and motivation barriers to change.

Utility of the BCW in examining vaccine hesitancy

The BCW offers a systematic approach to understanding the range of factors influencing the target behavior (i.e., addressing vaccine hesitancy) and potential intervention options. By describing barriers and enablers in behavioral terms, this approach helps to identify what interventions are working and where there are gaps in aligning interventions to behavioral determinants. The implementation science literature has shown that interventions are more effective when theory is used to identify behavioral determinants and tailor interventions to address these factors.Citation17 As described above, there are opportunities to use this theory-informed approach to tailor interventions to target nurses’ and pharmacists’ capability, opportunity, and motivation to address vaccine hesitancy among their patients. More recently, vaccination researchers have started to borrow from behavioral science to improve intervention design and implementation. The WHO Regional Office for Europe developed the Tailoring Immunization Programmes (TIP) approach to support vaccine uptake.Citation106 The TIP approach adapted the BCW for vaccine-related concerns and highlights the importance of understanding barriers to vaccination before developing interventions. Other researchers have been using the BCW to identify factors affecting influenza vaccine uptake in adults with chronic respiratory conditionsCitation107 and health-care workers in long-term care facilities,Citation108 as well as designing an implementation intervention to increase HPV vaccinations in primary care.Citation109 We recommend building on this momentum and continuing to use behavioral science to design, implement, and evaluate interventions to address vaccine hesitancy.

Strength and limitations

This review posed several strengths, including the use of a rigorous JBI scoping review methodology, which included searching multiple databases and grey literature. Our selection, screening, extraction, and mapping steps were completed by two independent reviewers. Further, by applying the Behavior Change Wheel to our scoping review findings, we have clearly outlined behavioral determinants and mechanisms of action that can be tested to build our understanding of what interventions work in the context of addressing vaccine hesitancy. This work also presents the following limitations. First, we did not complete quality appraisal as the aim of this review was to map the existing literature. Second, although comprehensive, this scoping review was limited in the language and search terms used. As a result, our findings may be different from those conducted in lower-income and middle-income countries. Lastly, our review was conducted prior to the development of COVID-19 vaccinations and does not include COVID-19-specific vaccine hesitancy studies. However, our systematic, behavioral analysis provides a strong theoretical and empirical foundation, from which interventions can be designed to address COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy moving forward.

Conclusion

This current scoping review offers a detailed behavioral analysis of known barriers and enablers influencing nurses’ and pharmacists’ ability to address vaccine hesitancy and interventions mapped onto these behavioral determinants. We identified nine barriers and six enablers related to nurses’ and pharmacists’ capability, opportunity, and motivation to address vaccine hesitancy among their patients. The majority of existing interventions are focused on education and training, which target known capability-related barriers to addressing vaccine hesitancy. Fewer interventions exist to target known opportunity- and motivation-related barriers. Future vaccination practitioners and researchers can use these findings as a foundation to tailor interventions to target barriers and enablers to addressing vaccine hesitancy. Subsequent evaluation research is needed to understand if interventions are addressing the right behavioral determinants and to what effect.

Author contributors

All authors listed on the manuscript have met the ICMJE authorship criteria as follows: all authors (CC, JL, AS, BT, AS, NKK, HG, LS & JI) provided substantial contributions to the concept/design of the manuscript; helped draft, provided intellectual content and continual revision; provided final approval of the version to be published and are in agreement/accountable to all aspects of the work submitted.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (22.4 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (24.1 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Rachel Dorey and Lauren Donnelly for their help with data extraction.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website at https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2021.1954444

Additional information

Funding

References

- CDC. Ten great public health achievements– United States 1900-1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999;48(12):241–43.

- WHO. Ten health issues WHO will tackle this year; 2019 [accessed 2020 Feb 17]. https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019

- WHO. Vaccination greatly reduces disease, disability, death and inequity worldwide; 2020.

- Larson HJ, Jarrett C, Eckersberger E, Smith DMD, Paterson P. Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective: a systematic review of published literature, 2007-2012. Vaccine. 2014;32(19):2150–59. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.081.

- MacDonald NE, Eskola J, Liang X, Chaudhuri M, Dube E, Gellin B, Goldstein S, Larson H, Manzo ML, Reingold A, et al. Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4161–64. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036.

- Dubé E, Laberge C, Guay M, Bramadat P, Roy R, Bettinger J. Vaccine hesitancy: an overview. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9(8):1763–73. doi:10.4161/hv.24657.

- Kwok K, Lai F, Wei W, Herd TJ. Immunity- estimating the level required to halt the COVID-19 epidemics in affected countries. J Infect. 2020;80:e32–e33. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.027.

- Sanche S, Lin YT, Xu C, Romero-Severson E, Hengartner N, Ke R. RESEARCH high contagiousness and rapid spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(7):1470–77. doi:10.3201/eid2607.200282.

- Hobson-West P. Understanding vaccination resistance: moving beyond risk. Health Risk Soc. 2003;5(3):273–83. doi:10.1080/13698570310001606978.

- Dubé E, Gagnon D, MacDonald NE, Eskola J, Liang X, Chaudhuri M, Dube E, Gellin B, Goldstein S, Larson H, et al. Strategies intended to address vaccine hesitancy: review of published reviews. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4191–203. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.041.

- Jarrett C, Wilson R, O’Leary M, Eckersberger E, Larson HJ, Eskola J, Liang X, Chaudhuri M, Dube E, Gellin B, et al. Strategies for addressing vaccine hesitancy - A systematic review. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4180–90. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.040.

- Karras J, Dubé E, Danchin M, Kaufman J, Seale H. A scoping review examining the availability of dialogue-based resources to support healthcare providers engagement with vaccine hesitant individuals. Vaccine. 2019;37(44):6594–600. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.09.039.

- Gust DA, Kennedy A, Wolfe S, Sheedy K, Nguyen C, Campbell S. Developing tailored immunization materials for concerned mothers. Health Educ Res. 2008;23(3):499–511. doi:10.1093/her/cym065.

- de St. Maurice A, Edwards KM, Hackell J. Addressing vaccine hesitancy in clinical practice. Pediatr Ann. 2018;47(9):e366–e370. doi:10.3928/19382359-20180809-01.

- Grol R, Grimshaw J. From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients’ care. Lancet. 2003;362(9391):1225–30. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14546-1.

- Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new medical research council guidance. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(5):587–92. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.09.010.

- Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions; 2008. [accessed 2021 May 1]. www.mrc.ac.uk/complexinterventionsguidance

- Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Sci. 2011;6:1. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-6-42.

- Enabler def. Oxford University Press; 2020 [accessed 2020 Dec 4]. https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/enabler?q=enabler

- Barrier def. Oxford University Press; 2020 [accessed 2020 Dec 4]. https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/us/definition/english/barrier?q=barriers

- Lovett- Scott M, Prather F. Global health systems: comparing strategies for delivering health services. 1st ed. Burlington (MA): Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2014.

- Brown LD. Comparing health systems in four countries: lessons for the United States. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(1):52–56. doi:10.2105/AJPH.93.1.52.

- The Joanna Briggs institute reviewers’ manual 2015 methodology for JBI scoping reviews. Joanna Briggs Institute; 2015.

- Peters M, Godfrey CMP, Munn Z, Tricco ACKH. Chapter 11: scoping reviews. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual; 2020.

- Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. Grey Matters: a practical tool for searching health-related grey literature; 2020.

- Covidence [accessed August 10, 2018]. https://www.covidence.org/reviews/active

- Michie S, Atkins L, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a guide to designing interventions. 1st ed. Silverback Publishing; 2014.

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MDJ, Horsley T, Weeks L, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73. doi:10.7326/M18-0850.

- Vaccine hesitancy: understanding and addressing vaccine hesitancy during COVID-19. American Pharmacists Association; 2020.

- Anderson P, Bryson J. Confronting vaccine hesitancy. Nursing. 2020;50(8):43–46. doi:10.1097/01.NURSE.0000668436.83267.29.

- Anderson VL. Promoting childhood immunizations. J Nurs Pract. 2015;11(1):1–10. doi:10.1016/j.nurpra.2014.10.016.

- Apfel F, Cecconi S, Oprandi N, Larson H, Karafillakis E. Let’s talk about hesitancy. Stockholm; 2016.

- Bernard DM, Cooper Robbins SC, McCaffery KJ, Scott CM, Rachel Skinner S. The domino effect: adolescent girls’ response to human papillomavirus vaccination. Med J Aust. 2011;194(6):297–300. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2011.tb02978.x.

- Berry NJ, Henry A, Danchin M, Trevena LJ, Willaby HW, Leask J. When parents won’t vaccinate their children: a qualitative investigation of Australian primary care providers’ experiences. BMC Pediatr. 2017;17(1):1–10. doi:10.1186/s12887-017-0783-2.

- Black ME, Ploeg J, Walter SD, Hutchison BG, Scott EAF, Chambers LW. The impact of a public health nurse intervention on influenza vaccine acceptance. Am J Public Health. 1993;83(12):1751–53. doi:10.2105/AJPH.83.12.1751.

- Blackford JK. Immunization controversy: understanding and addressing public misconceptions and concerns. J Sch Nurs. 2001;17(1):32–37. doi:10.1177/105984050101700105.

- Bowling AM. Immunizations – nursing interventions to enhance vaccination rates. J Pediatr Nurs. 2018;42:126–28. doi:10.1016/j.pedn.2018.06.009.

- Brackett A, Butler M, Chapman L. Using motivational interviewing in the community pharmacy to increase adult immunization readiness: a pilot evaluation. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2015;55(2):182–86. doi:10.1331/JAPhA.2015.14120.

- Carhart MY, Schminkey DL, Mitchell EM, Keim-Malpass J. Barriers and facilitators to improving Virginia’s HPV vaccination rate: a stakeholder analysis with implications for pediatric nurses. J Pediatr Nurs. 2018;42(2018):1–8. doi:10.1016/j.pedn.2018.05.008.

- Courtney E. Communicating effectively with vaccine-hesitant patients. Western University; 2019.

- D’Arrigo T Vaccine hesitancy: pharmacists step up to address fears about immunization in their communities. Pharmacy Today. 2018 Jul:24–27.

- Dahlqvist J, Stalefors J, Pennbrant S. Child health care nurses’ strategies in meeting with parents who are hesitant to child vaccinations. Clin Nurs Stud. 2014;2(4):47–59. doi:10.5430/cns.v2n4p47.

- Davis TC, Fredrickson DD, Kennen EM, Humiston SG, Arnold CL, Quinlin MS, Bocchini JA. Vaccine risk/benefit communication: effect of an educational package for public health nurses. Health Educ Behav. 2006;33(6):787–801. doi:10.1177/1090198106288996.

- Deem MJ. Responding to parents who refuse childhood immunizations. Nursing. 2017;47(12):11–14. doi:10.1097/01.NURSE.0000526899.00004.b9.

- Dempsey A, Zimet G. Interventions to Improve adolescent vaccination: what may work and what still needs to be tested. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(6):S445–454. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2015.04.013.

- Donovan H, Bedford H. Talking with parents about immunisation. Primary Health Care. 2013;23(4):16–20. doi:10.7748/phc2013.05.23.4.16.e741.

- Dubé E, Gagnon D, Clément P, Bettinger JA, Comeau JL, Deeks S, Guay M, MacDonald S, MacDonald NE, Mijovic H, et al. Challenges and opportunities of school-based HPV vaccination in Canada. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(7–8):1650–55. doi:10.1080/21645515.2018.1564440.

- Dubé E, Gagnon D, Vivion M. Optimizing communication material to address vaccine hesitancy. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2020;46(2/3):48–52. doi:10.14745/ccdr.v46i23a05.

- Fernbach A. Parental rights and decision making regarding vaccinations: ethical dilemmas for the primary care provider. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2011;23(7):336–45. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7599.2011.00627.x.

- Fogarty C, Crues L. How to talk to reluctant patients about the flu shot. Fam Pract Manag. 2017:6–8. https://regroup-production.s3.amazonaws.com/documents/ReviewReference/198002259/HOWTOTALKTORELUCTANTPATIENTSABOUTTHEFluShot.pdf?AWSAccessKeyId=AKIAJBZQODCMKJA4H7DA&Expires=1620831278&Signature=U9g0HSUKWOz%2BRM7aIAVY2fKHn%2F0%3D .

- Greene A. Vaccination fears: what the school nurse can do. J Sch Nurs. 2002;18(Suppl(13)):31–35. doi:10.1177/105984050201800408.

- Hidalgo S. Do nurse practitioner phone call, to parents declining HPV vaccine, increase adolescent vaccination rates in school-based health centers: a DNP project. Southeastern Louisiana University; 2017.

- Hinman AR. How should physicians and nurses deal with people who do not want immunizations? Can J Public Health. 2000;91(4):248–51. doi:10.1007/bf03404280.

- Hoekstra S, Margolis L. The importance of the nursing role in parental vaccine decision making. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2016;55(5):401–03. doi:10.1177/0009922815627348.

- Wade GH. Nurses as primary advocates for immunization adherence. MCN Am J Maternal/Child Nurs. 2014;39(6):351–56. doi:10.1097/NMC.0000000000000083.

- Hurley- Kim K Tackling vaccination hesitancy unrelated to medical exemption. Pharmacy Today; 2019.

- Kenney K. Learn how to counter vaccine hesitancy. Pharm Times. 2019;85:1.

- Koslap-Petraco MB, Parsons T. Communicating the benefits of combination vaccines to parents and health care providers. J Pediatr Health Care. 2003;17(2):53–57. doi:10.1067/mph.2003.42.

- Koslap-Petraco M. Vaccine hesitancy: not a new phenomenon, but a new threat. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2019;31(11):624–26. doi:10.1097/JXX.0000000000000342.

- Is KL. There a resurgence of vaccine preventable diseases in the U.S.? J Pediatr Nurs. 2019;44:115–18. doi:10.1016/j.pedn.2018.11.011.

- Lisenby KM, Patel KN, Uichanco MT. The role of pharmacists in addressing vaccine hesitancy and the measles outbreak. J Pharm Pract. 2021;34(1):127–32. doi:10.1177/0897190019895437.

- Ludwikowska KM, Biela M, Biela M, Szenborn L. HPV vaccine acceptance and hesitancy - Lessons learned during 8 years of regional HPV prophylaxis program in Wroclaw, Poland. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2020:346–49. doi:10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000556.

- Luthy KE, Burningham J, Eden LM, Macintosh JLB, Beckstrand RL. Addressing parental vaccination questions in the school setting: an integrative literature review. J School Nurs. 2016;32(1):47–57. doi:10.1177/1059840515606501.

- Macdonald K, Wick J Vaccine Hesitancy: Management Strategies for Pharmacy Teams. 2020.

- Maurici M, Arigliani M, Dugo V, Leo C, Pettinicchio V, Arigliani R, Franco E. Empathy in vaccination counselling: a survey on the impact of a three-day residential course. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(3):631–36. doi:10.1080/21645515.2018.1536587.

- Marcus B. A nursing approach to the largest measles outbreak in recent U.S. history: lessons learned battling homegrown vaccine hesitancy. Online J Issues Nurs. 2020;25(1):3. doi:10.3912/OJIN.Vol25No01Man03.

- Mossey S, Hosman S, Montgomery P, McCauley K. Parents’ experiences and nurses’ perceptions of decision-making about childhood immunization. Cana J Nurs Res. 2020;52(4):255–67. doi:10.1177/0844562119847343.

- Navin MC, Kozak AT, Deem MJ. Perspectives of public health nurses on the ethics of mandated vaccine education. Nurs Outlook. 2020;68(1):62–72. doi:10.1016/j.outlook.2019.06.014.

- Nicastro BM, Rejman KP. Parental decision making regarding vaccinations. Pediatrics. 2012;16:21–26.

- Nold L, Deem MJ. A simulation experience for preparing nurses to address refusal of childhood vaccines. J Nurs Educ. 2020;59(4):222–26. doi:10.3928/01484834-20200323-09.

- N.R. Improving immunization rates in high-risk populations. Abu Dhabi; 2020 [accessed 2021 May 1]. https://media.pharmacist.com/practice/19420-PracticeInsightsGlobalEdition2020Update103020.pdf

- Nutty A. A community effort: practices and information for communicating with vaccine- hesitant patients. Alaska Nurse. 2015:4–6. https://regroup-production.s3.amazonaws.com/documents/ReviewReference/198001233/ACommunityEffort-PracticesanInformationforCommunicatinwithVaccine-HesitantPatients.pdf?AWSAccessKeyId=AKIAJBZQODCMKJA4H7DA&Expires=1620873799&Signature=E5Ns7azlMxP.

- O’Keefe C, Vaccine: PM. Boon or Bane- a nurse’s outlook. In: Chatterjee A, editor. Vaccinophobia and vaccine controversies of the 21st Century. New York: Springer US; 2013. p. 165–80.

- Omecene NE, Patterson JA, Bucheit JD, Goode JVR, Caldas LM, Anderson AN, Rogers D. Pharmacist-administered pediatric vaccination services in the United States: major barriers and potential solutions for the outpatient setting. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2019;17(2):1–5. doi:10.18549/PharmPract.2019.2.1581.

- Orenstein WA, Gellin BG, Beigi RH, Despres S, Lynfield R, Maldonado Y, Mouton C, Rawlins W, Rothholz MC, Smith N, et al. Assessing the state of vaccine confidence in the United States: recommendations from the national vaccine advisory committee. Public Health Rep. 2015;130(6):573–95. doi:10.1177/003335491513000606.

- Poudel A, Lau ETL, Deldot M, Campbell C, Waite NM, Nissen LM. Pharmacist role in vaccination: evidence and challenges. Vaccine. 2019;37(40):5939–45. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.08.060.

- Pullagura GR, Violette R, Houle SKD, Waite NM. Exploring influenza vaccine hesitancy in community pharmacies: knowledge, attitudes and practices of community pharmacists in Ontario, Canada. Can Pharm J. 2020;153(6):361–70. doi:10.1177/1715163520960744.

- Punch D. In defence of immunization. Register Nurse J. 2015;27:9–14.

- Queeno BV. Evaluation of inpatient influenza and pneumococcal vaccination acceptance rates with pharmacist education. J Pharm Pract. 2017;30(2):202–08. doi:10.1177/0897190016628963.

- Rawson SJ, Conway JH, Hayney MS. Addressing vaccine hesitancy in the pharmacy. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2016;56(2):209–10. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2016.02.008.

- Rivera J. Development and evaluation of clinical practice guideline to promote an evidence-based approach to vaccine hesitancy in primary care. The University of Arizona; 2017.

- Schollin Ask L, Hjern A, Lindsrand A, Olen O, Sjögren E, Örtqvist Å MB. Receiving early information and trusting Swedish child health centre nurses increased parents’ willingness to vaccinate against rotavirus infections. Acta Paediatrica. 2017;106(8):1309–16. doi:10.1111/apa.13872.

- Scott K, Lou BM. HPV vaccine uptake among Canadian youth and the role of the nurse practitioner. J Community Health. 2016;41(1):197–205. doi:10.1007/s10900-015-0069-2.

- Sharpe AR, Hayney MS. Strategies for responding to vaccine hesitancy and vaccine deniers. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2019;59(2):291–92. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2019.01.009.

- Speck A, Li C, Diekevers M, Engen M, Van Wyhe M. Addressing childhood vaccination hesitancy. NWC.

- Stevens J. The C.A.S.E. Approach (Corroboration, About Me, Explain/Advise): improving communication with vaccine-hesitant parents. University of Arizona; 2016.

- Stinchfield P. Vaccine safety communication: the role of the pediatric nurse. JSPN. 2001;6(3):143–46. doi:10.2307/j.ctv1574phk.5.

- Taddio A, Freedman T, Wong H, Mcmurtry CM, Macdonald N, Ilersich ANT, Ilersich ALT, Mcdowall T. Stakeholder feedback on The CARDTM system to improve the vaccination experience at school. Paediat Child Health (Canada). 2019;24(7):S29–S34. doi:10.1093/pch/pxz018.

- Venzke M, Pintz C, Posey L. Evaluation of a learning module for nurse practitioner students: strategies to address patient vaccine hesitancy/ refusal. Washington: Sigma Nursing; 2016.

- Violette R, Pullagura GR. Vaccine hesitancy: moving practice beyond binary vaccination outcomes in community pharmacy. Can Pharm J. 2019;152(6):391–94. doi:10.1177/1715163519878745.

- Vyas D, Galal SM, Rogan EL, Boyce EG. Training students to address vaccine hesitancy and/or refusal. Am J Pharm Educ. 2018;82(8):6338. doi:10.5688/ajpe6338.

- Warner JC. Overcoming barriers to influenza vaccination. Nurs Times. 2012;108:25–27.

- Ziemczonek A. Addressing vaccine hesitancy. University of British COlumbia: Pharmacists Clinic. 2020 Nov [accessed 2021 May 14]. https://e1.envoke.com/m/96eb22084d70e7a25cf58dab3b4f1ecc/m/7d7a38d41e56efc2fef5faef3b22f08b/?utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=Our-Practice%3A-November-2020-FI&utm_source=Envoke-Our-Practice&utm_term=Our-Practice%3A-Issue-20%2C-Novemb

- Gagneur A, Bergeron J, Gosselin V, Farrands A, Baron G. A complementary approach to the vaccination promotion continuum: an immunization-specific motivational-interview training for nurses. Vaccine. 2019;37(20):2748–56. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.03.076.

- Fotsch R. Vaccine hesitancy prompts healthcare leaders to take action. J Nurs Regul. 2020;11(4):71–72. doi:10.1016/S2155-8256(20)30178-2.

- Bradley R, Elder C. Addressing vaccine hesitancy. Perm J. 2020;24:175–81. doi:10.7812/TPP/20.216.

- Celeste J, Stevens JC. The C. A. S. E. Approach (Corroboration, About Me, Science, Explain/Advise): Improving Communication with Vaccine-Hesitant Parents by In the Graduate College; 2020.

- Solnick A, Weiss S. High fidelity simulation in nursing education: a review of the literature. Clin Simul Nurs. 2007;3(1):41–45. doi:10.1016/j.ecns.2009.05.039.

- Schnaith AM, Evans EM, Vogt C, Tinsay AM, Schmidt TE, Tessier KM, Erickson BK. An innovative medical school curriculum to address human papillomavirus vaccine hesitancy. Vaccine. 2018;36(26):3830–35. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.05.014.

- Rigone N, O’Donnell L. Educating the next generation of pharmacy students to address vaccine hesitancy. Pulses: Promoting dialogue in pharmacy education. 2021 May.

- Grundy Q, Bero LA, Malone RE. Marketing and the most trusted profession: the invisible interactions between registered nurses and industry. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(11):733–39. doi:10.7326/M15-2522.

- Bester JC. Vaccine refusal and trust: the trouble with coercion and education and suggestions for a cure. J Bioeth Inq. 2015;12(4):555–59. doi:10.1007/s11673-015-9673-1.

- Burki T. Vaccine misinformation and social media. Lancet Digital Health. 2019;1(6):e258–e259. doi:10.1016/S2589-7500(19)30136-0.

- Wouters OJ, Shadlen KC, Salcher-Konrad M, Pollard AJ, Larson HJ, Teerawattananon Y, Jit M. Challenges in ensuring global access to COVID-19 vaccines: production, affordability, allocation, and deployment. Lancet. 2021;397(10278):1023–34. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00306-8.

- Science Up First. Public health agency of Canada; 2020 [accessed 2021 May 11]. https://www.scienceupfirst.com/#:~:text=%23ScienceUpFirsisasocialmedia,andweneedyourhelp!

- Habersaat K, MacDonald NE, Ève Dubé È. Designing tailored interventions to address barriers to vaccination. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2021;47(3):166–69. doi:10.14745/ccdr.v47i03a07.

- Gallant AJ, Flowers P, Deakin K, Cogan N, Rasmussen S, Young D, Williams L. Barriers and enablers to influenza vaccination uptake in adults with chronic respiratory conditions: applying the behaviour change wheel to specify multi-levelled tailored intervention content. medRxiv. 2020:2020.11.18.20233783. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.11.18.20233783v1/0Ashttps://www.medrxiv.org/content/medrxiv/early/2020/11/18/2020.11.18.20233783.full.pdf .

- Kenny E, Á M, Noone C, Byrne M. Barriers to seasonal influenza vaccine uptake among health care workers in long-term care facilities: a cross-sectional analysis. Br J Health Psychol. 2020;25(3):519–39. doi:10.1111/bjhp.12419.

- Garbutt JM, Dodd S, Walling E, Aa L, Kulka K, Lobb R. Theory-based development of an implementation intervention to increase HPV vaccination in pediatric primary care practices. Implementation Sci. 2018;13(45):1–8. https://implementationscience.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13012-018-0729-6/0Ahttps://implementationscience.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13012-018-0729-6