ABSTRACT

Vaccine hesitancy (VH) in the age of adolescence is a major public health issue, though it has not been widely examined in the scientific literature. This systematic review aims to address the determinants of VH among adolescents aged 10–19. PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science were searched from the inception until 11 December 2020. Articles in English, assessing adolescents’ attitudes toward vaccination in terms of hesitancy and/or confidence were considered eligible. Out of 14,704 articles, 20 studies were included in the qualitative analysis. Quality assessment was performed through the Appraisal tool for Cross-Sectional Studies (AXIS). A better knowledge of vaccine-preventable diseases, a higher confidence in vaccines, as well as an active involvement in the decision-making process showed a positive relationship with adolescents’ vaccine uptake. These aspects should be considered to plan tailored interventions for the promotion of vaccination among adolescents and to reduce VH. Major limitations of this review are represented by the high heterogeneity of the tools used in the primary studies and the lack of standardization in outcomes definitions. Future research is needed to disentangle the interrelationship among the different determinants of VH in this age group.

Background

Vaccine hesitancy (VH) encompasses different phenomena, from delay in vaccine uptake to complete refusal. Actually, vaccine-hesitant individuals may refuse or delay some or all vaccines or even accept them albeit being unsure in doing so.Citation1,Citation2

In fact, the World Health Organization (WHO) defines VH as ‘a delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite the availability of vaccine services.’Citation3 VH is a complex and context-specific issue that varies according to time, place, and vaccine types.Citation4 The findings of a systematic review conducted by the dedicated working group of the Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE) on Immunization on routinely recommended childhood vaccines concluded that many factors are associated with VH and that there is not a unique group of determinants behind VH in all settings. For instance, a higher education showed a direct relationship with VH in China, USA, and Israel and an inverse relationship in Greece and Pakistan, while a lower education was associated with VH in Nigeria and Kyrgyzstan and was inversely related to VH in USA.Citation5

According to the “3Cs” model, VH is linked to complacency, convenience, and confidence. Complacency is defined as the perceived risk of contracting the disease; when it is low vaccination can be deemed an unnecessary preventive action. Convenience is defined as the perceived level of access to vaccinations; it depends on physical availability, affordability, geographical accessibility, ability to understand information (language and health literacy), and appeal of immunization services (the quality of the service). Confidence is defined as the trust in: (1) the effectiveness and safety of vaccines; (2) the system that delivers them, including the reliability and competence of health services and health professionals; and (3) the motivations of the policy-makers who decide on the recommended vaccines.

The more complex VH Matrix includes determinants that belong to three categories: contextual factors (influences due to historic, socio-cultural, environmental, health system/institutional, economic, or political factors), individual and group influences (due to personal perception of the vaccine or to social environment/peer), and vaccine/vaccination-specific issues (directly related to vaccine or vaccination).Citation4

VH has been paid attention by supranational organizations since the second decade of the 21st century. In 2015, a report was published by the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC)Citation6,Citation7 and important recommendations were issued by the SAGE on Immunization of the WHO.Citation8 Although models explaining VH and tools to address it have been published, VH still represents a current issue worldwide.Citation9

A study performed on 65,819 individuals from 67 countries showed different vaccine sentiments across world regions. In particular, the European region reported the highest mean-averaged negative responses for vaccine importance, safety, and effectiveness. Negative vaccine-safety perceptions were particularly alarming in the European region with seven out of the ten most negatively reporting countries to vaccine safety located in Europe.Citation10

Negative sentiments challenge vaccination programs and might prevent reaching the target of vaccination coverage. This justify why VH has been declared by the WHO as one of the top ten global health threats in 2019.Citation11

In order to make it possible to implement effective actions counteracting VH, the understanding of its determinants is of utmost importance. The determinants of VH have been addressed in several population subgroups, mostly parents,Citation12 and healthcare professionals.Citation13 Parents play a relevant role because they are also responsible for decisions on childhood vaccinations. Similarly, healthcare professionals are important for their role in influencing vaccination-related decisions of the general population.

Interestingly, other population subgroups are progressively catching the attention, namely pregnant womenCitation14 or elderly and specific groups of patients, in particular in respect to influenza vaccination.Citation15 To the best of our knowledge, adolescents represent the less studied target. Actually, there has been an increase in papers on adolescents’vaccinations acceptanceCitation5 but they mainly focused on vaccination against Human Papilloma Virus (HPV).Citation16,Citation17

Nevertheless, depending on country-specific immunization programmes, vaccinations intended for adolescents also include those against hepatitis B, tetanus, diphtheria, pertussis, measles, mumps, rubella, varicella, meningococcal diseases and, for risk groups, influenza, and pneumococcal diseases.Citation18 Several strategies can be implemented to improve vaccination uptake among adolescents, namely, health education programmes, school-based vaccination, financial incentives, or mandatory vaccination. They can target adolescents, parents, and healthcare providers but the body of evidence on their efficacy is of lo- to-moderate certainty and a deeper understanding of factors that influence uptake would be deserved.Citation19

Adolescent vaccination has become a major health priority. In the light of a life-course immunization, adolescents should be paid attention as target of both primary immunization and boosting shots and catch up programmes.Citation20,Citation21 Furthermore, 25% of the global population is represented by adolescents, but their vaccine uptake remains low.Citation22

The objective of the present review is to identify main reasons behind VH and vaccine confidence in the adolescent population, including individual, contextual, and vaccine-/vaccination-related issues. The synthesis of these information will be useful to address VH and, consequently, set up intervention to increase adolescents’ vaccination coverage.

Materials and methods

A systematic review was conducted and reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA).Citation23

After structuring a search string, three electronic databases were searched to retrieve studies exploring reasons of VH and vaccine confidence in the adolescent population according to pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Then, data were extracted and synthesized qualitatively and a methodological quality assessment of included articles was performed.

Search strategy

Web of Science, PubMed, and Scopus were queried to retrieve potential eligible articles published from the inception until 11 December 2020.

A search string was created on the basis of the PICO model (P, population/patient; I, intervention/indicator; C, comparator/control; and O, outcome).

The string ((“adolescent”[MeSH Terms] OR adolescent* OR teenager* OR “young adult”[MeSH Terms] OR “students”[MeSH Terms]) AND ((vaccine AND confidence) OR (vaccine AND hesitancy) OR (vaccine attitudes)) was launched on PubMed and then adapted to the other two databases.

The reference lists of included articles were hand searched to look for additional eligible studies.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Articles on determinants of adolescents’ attitudes or behaviors in respect to vaccination with any study design (quantitative or qualitative) and published in English were included in the systematic review. For the purpose of the study, we used the WHO 2018 ‘adolescents’ definition, according to which “Adolescence is the phase of life between childhood and adulthood, from ages 10 to 19.”Citation24 Therefore, we considered studies eligible if the mean age of the study population fell between 10 and 19 years.

We excluded systematic reviews, non-empirical studies, conference, abstracts, editorials, commentaries, book reviews, and abstracts not accompanied by a full text. Furthermore, animal and modeling studies were also excluded. Studies that took into consideration parents’ attitudes alongside those of their adolescent children were excluded as well, unless data from the two age groups could be distinguished. In this case, only data from adolescents were extracted and included in our analysis.

Moreover, articles mentioning ‘college/university students’ but not specifying the age of the study population and those considering interventions aimed to increase vaccination confidence among teenagers were also not included.

Study selection

After removing duplicate records, four researchers (C.C., T.E.L., R.M., M.S.) independently screened articles first by title and abstract and then on the basis of the full texts. Disagreements were resolved through discussion among the review team members. The study selection was performed from December 2020 to January 2021.

Data extraction

The four researchers above-mentioned conducted data extraction from the end of January to February 2021. A dedicated data extraction form developed on Excel was used to gather the following information for each eligible study:

Study identification (first author, title, journal, and publication year)

Study characteristics (period, country, and design)

Sample characteristics (sample size, age, gender, and socio-cultural-economic context)

Vaccines/vaccinations investigated

Study outcome(s)

Research tools used (face-to-face/online/self-administered questionnaire, interview, and focus groups)

Preparatory materials provided

Data synthesis

According to data extraction, articles explored different types of vaccinations, adopted different tools for investigation (e.g., questionnaires, surveys, interviews etc.) and were performed in various contexts. Because of all these reasons and the heterogeneity of the information collected, data synthesis was conducted only qualitatively.

Quality assessment

The four researchers independently conducted the methodological quality assessment of included articles. Disagreements were resolved by discussion with a fifth researcher (Ch.C.). As the selected studies were all cross-sectional, the Appraisal tool for Cross-Sectional Studies (AXIS) was used to assess the methodological quality.Citation25 This tool, developed by a consensus, offers the possibility to appraise the methodological quality of articles, based on several specific criteria. It consists of 20 items and allows to record ‘yes,’ ‘no,’ or ‘don’t know’ for each criterion and to add short comments.Citation25

To summarize the results of the quality assessment, the articles were grouped into three categories: good (studies satisfying at least 75% of the quality criteria), moderate (studies satisfying from 55% to 74% of the quality criteria), and poor (studies satisfying less than 55% of the quality criteria) quality.

Results

Results of the search strategy

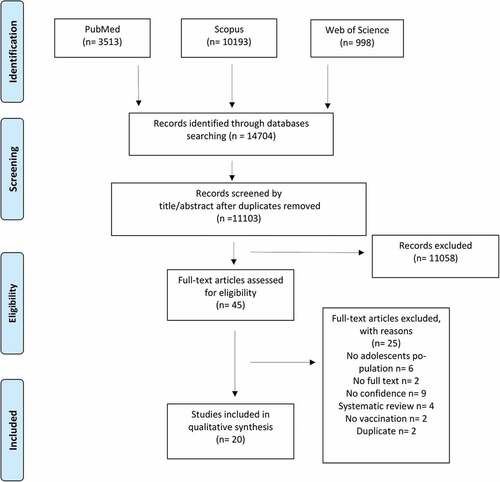

A total of 14,704 articles were retrieved from the three databases. After removing duplicates, the remaining 11,103 records were screened by title and abstract. The full texts of 45 papers were retrieved for the assessment of final eligibility.

Of these, 20 articlesCitation26–45 met eligibility criteria and were included in the systematic review. They were all cross-sectional studies. The selection process is reported in .

Results of the quality assessment

As illustrated in , quality assessment was performed for all the 20 articles evaluated in the analysis.

Table 1. Quality assessment of the included studies using AXIS quality assessment tool

TenCitation26–35, out of 20 studies (50%) were evaluated of ‘good quality,’ while nineCitation36–44 out of 20 (45%) were evaluated of ‘moderate quality.’ Only 1 studyCitation45 out of 20 (5%) had a poor quality, for this reason it was excluded. As a consequence of this, a total of 19Citation26–44 studies of ‘moderate’ and ‘good’ quality were considered in the descriptive analysis.

The objective of the study (criterion n. 1), the reference population for the sample (criterion n. 4), results presentation (criterion n. 16), discussion, and conclusions justified by the results (criterion n. 17) were well descripted by all the 19 (100%) studies.

On the contrary, none of the included studies met the criterion n.7, which asks for measures undertaken to address and categorize non-responders.

Furthermore, 18 out of 19 articlesCitation26–36,Citation38–44 (95%) clearly discussed the limitations of their studies (criterion n. n.18), and 16 articlesCitation26–35,Citation38,Citation39,Citation41–44 (84%) met the quality standards about methods reproducibility (criterion n.11).

Characteristics of the included studies

The majority of the included studies (53%) were conducted in European countries: oneCitation31 in Austria, oneCitation30 in France, oneCitation44 in Germany, oneCitation40 in Ireland, threeCitation28,Citation41,Citation42 in Italy, oneCitation39 in Romania, and oneCitation37 in Scotland. SevenCitation26,Citation29,Citation32,Citation36,Citation38,Citation42,Citation43, out of 19 (37%) were performed in US countries or counties.

Only oneCitation27 study was conducted in Asia, Hong Kong, oneCitation35 in Australia, and another oneCitation33 in Africa. Included articles were published from 2010 to 2020.

As far as study vaccines/vaccinations are concerned, studies were grouped into three categories:

Focusing on HPV vaccine only (12Citation26–28,Citation30,Citation33,Citation38–44 out of 19 articles – 63%);

Considering all vaccines in general (fiveCitation31,Citation34–37 out of 19–25%);

Examining all vaccines in general with a specific focus on HPV vaccine (twoCitation29,Citation32 out of 19–10%).

Half of the included articlesCitation28,Citation29,Citation31,Citation32,Citation34–37,Citation41,Citation44 (53%) considered samples balanced between females and males. Five studiesCitation26,Citation27,Citation33,Citation40,Citation43 took into account only female, while two studiesCitation30,Citation38 only males. Only two articlesCitation39,Citation42 did not describe the gender distribution of the study population. The description of the characteristics of the included studies is reported in .

Table 2. Description of the characteristics of the studies included in the systematic review

Outcome categories

All the included articles focused their attention on determinants that might influence adolescents’ vaccine confidence.

Although the majority of them – 15Citation26,Citation27,Citation29–33,Citation36–41,Citation43,Citation44 out of 19 (80%) – took also into consideration the reasons underlying VH.

As shown in , according to the findings, we chose to group the study outcomes into four different categories:

Vaccine-related issues (knowledge about the disease and the vaccine, vaccines’ effectiveness and safety);

Vaccination-related issues (source of information, vaccine costs, vaccination setting, injection fear and related pain);

Individual factors;

Socio-cultural-economic characteristics.

Table 3. Description of the main findings assessed from the studies included in the systematic review

Vaccine-related issues (knowledge about the disease and the vaccine, vaccines’ effectiveness and safety)

Knowledge

Knowledge of vaccine-preventable diseases and associated risks, together with the awareness of available vaccines and the availability of correct information about them, are described as some of the major factors positively influencing adolescents’ vaccine acceptance.Citation33,Citation36,Citation42 On the contrary, lack of awareness and information about recommended vaccines was one of the main reasons given by adolescents for not receiving them.Citation30,Citation31,Citation33,Citation37 Likewise, some of the included studiesCitation37,Citation38,Citation42 confirmed that adolescents’ confidence on vaccines is higher if the disease is considered ‘severe,’ such as measles or HPV-related cervical cancer.

Concerning HPV, girls revealed to have a greater knowledge of HPV infection than boys and they also showed more favorable attitudes about HPV vaccination.Citation37

In accordance with one study,Citation34 girls compared to boys were 20% more likely of having a satisfactory knowledge about vaccine-preventable diseases (OR = 1.2; 95% CI 0.87–1.65). Boys were 20% (OR = 0.8; 95% CI 0.58–1.11) and 29% (OR = 0.71; 95% CI 0.48–1.05) less likely to show positive attitudes regarding the usefulness of vaccines to prevent diseases and to consider useful the information received about vaccinations with respect to girls. Some authorsCitation39 reported that a significant higher percentage of girls than boys (45.0% vs 26.3%) was concerned about HPV infection and would have undergo HPV vaccination (68.3% vs 39.7%). According to another study,Citation44 a significant difference was observed between boys and either HPV-vaccinated or unvaccinated girls (13.6% vs 31.3% or 23.1%) in respect to the agreement with the statement ‘HPV infection occurs frequently.’ A significant difference was also observed between boys and HPV-vaccinated girls (43.9% vs 64.6%) in regard to the agreement on the statement reporting that HPV infection can cause premalignant lesions and carcinosis of cervix and penis.

Effectiveness/safety

Effectiveness and safety also represent two significant factors that positively affect the acceptability of vaccination among adolescents.Citation29,Citation30,Citation32,Citation36,Citation44 In particular, one studyCitation32 reported that adolescents were more likely to choose vaccines with 99% effectiveness than those with 20%.

Boys were significantly more likely than girls to perceive vaccines to be effective (49.7% vs 29.0) and believe they are ‘very safe’ (48.4% vs 30.2%).Citation29 Nevertheless, another study did not find differences between male and females in respect to preventive potential of vaccinations toward infectious diseases.

Concerns about the potential side effects deriving from the vaccine and the lack of detailed information about them are described as two of the main reasons underlying VH in the adolescent population.Citation33,Citation36,Citation44

According to some authors,Citation44 a statistically significant difference was observed between HPV-unvaccinated and vaccinated girls when considering the agreement about the severity of vaccination side effects (23.1% vs 10.4%) and the risk of weakening of the immune system through vaccination as reasons avoiding vaccinations (9.2% vs 1.0%).

Vaccination-related issues (source of information, vaccine costs, vaccination setting, injection fear, and related pain)

Source of information

According to our results, the family and school environment (e.g., participating in school educative seminars on HPV, formative intervention scheduled during school hours, school-based vaccination educational programs)Citation28,Citation35 seem to have a positive impact on adolescents’ attitude toward vaccinations. Indeed, some authorsCitation28 described that a school-based educational intervention was strongly associated with an increased HPV vaccination confidence, knowledge, and uptake, with young girls significantly more likely than boys peers in the willingness to receive vaccination after the educational intervention. According to our findings, the main sources of information on vaccinations and the most trusted ones were family, schools, family doctors, and other medical professionalsCitation28,Citation30,Citation32,Citation35,Citation36. On the contrary, the least reliable source of information were social media, even though they represent the most easily accessible.Citation28,Citation30,Citation32,Citation35,Citation36

Setting and costs

In some cases, having different options to access the vaccine (e.g., school, free clinics, etc.) is a factor that positively affect confidence in vaccination programmes and also leads to an increased uptake.Citation33

Some of the included studies,Citation26,Citation27,Citation32,Citation40 conducted in different countries and contexts, reported vaccine cost as a potential barrier to vaccine uptake: a high cost might be a driver of VH among adolescents if compared to a low-cost vaccine or to a vaccine free of charge.

Injection/fears/pain

One studyCitation40 of the included studies (5%) reported that the fear of the needle and the pain due to the injection are potential discouraging factors, while combined vaccines are significantly preferred since they reduce the overall number of injections.Citation37

Only one studyCitation35 found a slightly higher number of females than males expressing fear of pain at the injection site.

Individual factors

Adolescents seem generally to prefer taking an active part in the decision-making process, since they feel able to deal with it by themselvesCitation35. However, they also appreciate the support and the guidance of professionals, like medical doctors, or of their parents.Citation35

Data on HPV vaccination showed that vaccine confidence is greater in individuals with a previous history of sexual intercoursesCitation26,Citation38,Citation43 and in those who know someone already vaccinated against HPV, such as school friends.Citation38.

Socio-cultural-economic characteristics

Adolescents’ attitudes toward vaccinations were significantly more favorable in those who had at least one graduated parent,Citation34,Citation43 while there were not significant associations with the parents’ occupation.Citation30 Attending middle or high school or being at a private or public facility were not significantly associated with adolescents’ attitudes toward HPV vaccinations.Citation30 One study,Citation29 conducted in several schools of different areas in New York, showed that adolescents living in the suburbs are less involved in the vaccine decision-making process than those who live in urban areas. Monthly household income higher than 1,000 EurosCitation39 and annual income higher than 75,000Citation38 seemed to be associated with a better vaccination confidence and uptake.

Discussion

Key results of the systematic review

Our review addressed determinants of VH and vaccine confidence in the adolescent population being the first one, to the best of our knowledge, to provide a broad overview of the topic. In fact, our review focused on all types of vaccinations recommended to adolescents and looked at the total range of reasons behind VH in this age. Most of the articles included in the review actually dealt with HPV vaccination but 35% also addressed other vaccines. Interestingly, included papers were mostly published in the last three years, except for Wang et al. 2016Citation35 and Hilton et al. 2013,Citation37 and this showcases the increasing interest in the topic as a whole. In respect to determinants of VH, the findings showed that, as expected, confidence in vaccines effectiveness and safety plays a relevant role also among adolescents.Citation26,Citation32,Citation44 In addition, the lack of awareness and information on vaccine-preventable diseases and vaccines, often reported among adolescents,Citation30,Citation36,Citation39 negatively impact on vaccination attitudes.Citation30,Citation33,Citation39,Citation41,Citation43 Other important determinants of vaccine acceptance, beside some individual and socio-economic factors, pertained to vaccination-related issues and included ease of accessCitation33 and cost of vaccination.Citation27,Citation32

Current debate on the topic

VH and its determinants in the adolescent population have been paid less attention as compared to other age groups. Published systematic reviews on adolescent population have mainly focused on HPV vaccination addressing specific groups, such as boys,Citation46 or determinants, such as knowledge and preferences.Citation47,Citation48 On the contrary, the paper by Karafillakis et al.Citation17 took a broader perspective addressing determinants of VH toward HPV vaccination in the whole European population, including parents and healthcare workers. They showed a higher percentage of people reporting doubts on safety and effectiveness of HPV vaccines among hesitant people. With this respect, the importance of confidence on vaccines was also emphasized by our findings, not only for HPV but also for other vaccinations. Undoubtedly, the lack of confidence is recognized as one of the most vital determinants of VH. This is also demonstrated by the Vaccine Confidence ProjectCitation49 effort in measuring the public confidence in immunization programmes in people aged 18 and older. Another important determinant is information issues. In fact, Karafillakis et al.Citation17 identified insufficient knowledge or information as an underlying reason of VH in almost all articles they considered. Our review showed that information issues represent a challenge also in regard to vaccinations other than HPV. Luckily, our findings also attested that adolescents trust more family physicians or other medical professionals and parents than social media.Citation26,Citation32,Citation36,Citation40 This aspect is closely linked to vaccination confidence as it is described as the “belief that vaccination – and by extension the providers and range of private sector and political entities behind it – serves the best health interests of the public.”Citation50 Adolescents’ trust in health professionals is a relevant piece of information, which adds up to similar results issued by the survey on Europeans’ attitudes toward vaccination of the European Commission.Citation51 This information is of great potential interest in order to set up intervention to improve adolescents’ knowledge and awareness on vaccine-preventable diseases.Citation52 In addition, the school context has a fundamental role in this process. In fact, previous research provides evidence that educating students through school-based educational programs, represents one of the best practices to promote vaccine awareness among adolescents.Citation28,Citation53 In respect to vaccination-specific issues, our review pinpointed ease of access as a potential determinant, adding relevant information to the identification of access barriers in the adolescent population. The review authored by Thomson et al.Citation54 summarized the evidence on the reasons behind low vaccination uptake addressing five domains, namely access, affordability, awareness, acceptance, and activation. The authors concluded that access and affordability of vaccination can represent important barriers in many contexts, despite interventions aimed at increasing vaccine awareness and acceptance. This should be kept in mind to improve vaccine uptake, as the Authors showed that arranging the vaccination in universities and schools could be helpful. As already stated in the introduction section, other factors beyond vaccine-/vaccination-specific issues play a role in VH, namely, contextual and individual/group factors.Citation4 Actually, also the findings of our review highlighted that both these factors can play a role. As far as contextual factors are concerned, the review showed a potential indirect relationship between VH and socio-economic conditions in terms of higher parents’ education and household income.Citation38,Citation39 Nevertheless, these finding asks for confirmation, because results on the role of socio-economic status seem currently not conclusive.Citation5 Eventually, individual/groups factors, such as knowing someone who got the vaccine and personal sexual behaviors,Citation38 as well as fear of the injection play a role.Citation49

Larson et al.Citation5 pinpointed to the importance of parents’ awareness and dissuasion in vaccine uptake among adolescents. In this regard, a last relevant aspect needing further attention is that adolescents call for either an involvement in the decision to be vaccinatedCitation35 or for a complete autonomy in decision.Citation34,Citation35,Citation43 These findings implicate some very sensitive and still debated ethical issues, including topics regarding minors’ medical decisions such as the right time for minors to make their own health decisions. Generally speaking, children are considered non-autonomous until they reach 18 years of age. Nevertheless, denying vaccination to adolescents because of parents’ choice could lead to important health threats at individual and society level. In light of this and considering that in some countries adolescents are already allowed to make own decision on sensitive or stigmatized healthcare services, some Authors call for laws enacting minors to consent to vaccination if at least 12 or 14 years old.Citation55,Citation56 Another point is the involvement of adolescents in the vaccine-related decision that is generally ensured, albeit in different extent,Citation57 and whose final impact on vaccine uptake would deserve more investigations.

Limitations and strengths

This review has some limitations that should be considered when interpreting results:

Protocol of this systematic review was not registered;

Only articles published in English were included in the analysis, and this might have led to and underrepresentation of findings from certain countries. In fact, the great majority of studies included were from Europe and USA, whereas data available from other regions were dearth;

A potential bias in the selection of studies cannot be completely ruled out, even though selection was performed independently by four researchers working in couples supervised by a fifth senior researcher;

The heterogeneity of the tools used in the studies, namely, questionnaires/interviews/national surveys/focus-groups and the lack of homogeneity in outcomes definition prevented us making a meta-analysis and issuing more conclusive findings. Nevertheless, it should be said that the whole literature on VH and its determinants is still undermined by the lack of standardization of definitions (i.e., confidence, acceptance and uptake are generally used interchangeably), data collection, and analysis. Nonetheless, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review giving an overview of determinants of VH and vaccine confidence in the adolescent population. Furthermore, as a strength, most of the studies were judged of moderate-good quality.

Final remarks and suggestions for future research

In the context of VH, adolescents still represent a poorly investigated population. Nonetheless, they are an important target of both primary immunization with new vaccines and boosting shots and catch-up programmes. Adolescence is also a phase of life in which boys and girls begin to make significant choices in respect to their health and develop attitudes and behaviors that remain in adulthood. Improving adolescents’ vaccination uptake can provide substantial health benefits to individuals, society, and future generations. Indeed, further studies should better disentangle the role of VH determinants and their interrelationship and investigate how VH and its determinants influence the final vaccination uptake considering also other issues, such as access and affordability. Finally, new evidence would be worthwhile to address context-specific determinants of VH in the adolescent population.

Conclusion

This systematic review provides an overview of the total range of determinants of VH in the adolescent population advancing knowledge to what is already known for HPV. The knowledge of vaccine-preventable diseases and the confidence in vaccines, as well as an active involvement in the decision-making process were shown significant factors that positively influenced adolescents’ attitudes. These aspects should be taken into consideration to plan tailored interventions to reduce VH and then strengthen vaccine uptake among adolescents. Future research should be conducted to disentangle the interrelationship between different determinants of VH, also considering the role of contextual aspects and other challenges for vaccine uptake. This will be fundamental to develop context-specific interventions.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

All the Authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Dubé E, Vivion M, MacDonald NE. Vaccine hesitancy, vaccine refusal and the anti-vaccine movement: influence, impact and implications. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2015 Jan 2;14(1):99–117. doi:10.1586/14760584.2015.964212.

- WHO SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Report of the SAGE working group on vaccine hesitancy. 2014. www.who.int/immunization/sage/meetings/2014/october/SAGE_working_group_revised_report_vaccine_hesitancy.pdf

- Organization WHO. Global vaccine action plan 2011-2020. apps.who.int. World Health Organization; 2013 [accessed 2021 Mar 21]. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/78141

- MacDonald NE. Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015 Aug 14;33(34):4161–64. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036.

- Larson HJ, Jarrett C, Eckersberger E, Smith DM, Paterson P. Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective: a systematic review of published literature, 2007–2012. Vaccine. 2014 Apr 17;32(19):2150–59. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.081.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Rapid literature review on motivating hesitant population groups in Europe to vaccinate. Stockholm; 2015. 34 p. [accessed 2021 Mar 21]. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/media/en/publications/Publications/vaccination-motivating-hesistant-populations-europe-literature-review.pdf

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Vaccine hesitancy among healthcare workers and their patients in Europe– a qualitative study. Stockholm; 2015. 33 p [accessed 2021 Mar 21]. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/vaccine-hesitancy-among-healthcare-workers-and-their-patients-europe

- Edited by Melanie Schuster, Philippe Duclos. Vaccine | WHO recommendations regarding vaccine hesitancy | scienceDirect.com. Sciencedirect.com. 2015 [accessed 2021 Jul 8]. https://www.sciencedirect.com/journal/vaccine/vol/33/issue/34

- Yaqub O, Castle-Clarke S, Sevdalis N, Chataway J. Attitudes to vaccination: a critical review. Soc Sci Med. 2014 Jul 1;112:1–1. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.04.018.

- Larson HJ, de Figueiredo A, Xiahong Z, Schulz WS, Verger P, Johnston IG, Cook AR, Jones NS. The state of vaccine confidence 2016: global insights through a 67-country survey. EBioMedicine. 2016 Oct;12:295–301. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.08.042.

- World Health Organization. Ten health issues WHO will tackle this year. World Health Organization. 2021. [accessed 2021 Mar 21]. https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019

- Schellenberg N, Crizzle AM. Vaccine hesitancy among parents of preschoolers in Canada: a systematic literature review. Can J Public Health. 2020 Aug;11:1–23.

- Vasilevska M, Ku J, Fisman DN. Factors associated with healthcare worker acceptance of vaccination: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Control & Hosp Epidemiol. 2014 Jun;35(6):699–708. doi:10.1086/676427.

- Wilson RJ, Paterson P, Jarrett C, Larson HJ. Understanding factors influencing vaccination acceptance during pregnancy globally: a literature review. Vaccine. 2015 Nov 25;33(47):6420–29. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.08.046.

- Okoli GN, Lam OL, Abdulwahed T, Neilson CJ, Mahmud SM, Abou-Setta AM. Seasonal influenza vaccination among cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the determinants. Curr Probl Cancer. 2020 Sep;4:100646.

- Karafillakis E, Larson HJ. The benefit of the doubt or doubts over benefits? A systematic literature review of perceived risks of vaccines in European populations. Vaccine. 2017 Sep 5;35(37):4840–50. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.07.061.

- Karafillakis E, Simas C, Jarrett C, Verger P, Peretti-Watel P, Dib F, De Angelis S, Takacs J, Ali KA, Celentano LP, et al. HPV vaccination in a context of public mistrust and uncertainty: a systematic literature review of determinants of HPV vaccine hesitancy in Europe. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019 Feb 20;15(7–8):1615–27. doi:10.1080/21645515.2018.1564436.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Vaccine Scheduler | ECDC. Europa.eu. 2009. [accessed 2021 Mar 21]. https://vaccine-schedule.ecdc.europa.eu/

- Abdullahi LH, Kagina BM, Ndze VN, Hussey GD, Wiysonge CS. Improving vaccination uptake among adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020 Jan 17;1(1):CD011895. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011895.pub2.

- Brabin L, Greenberg DP, Hessel L, Hyer R, Ivanoff B, Van Damme P. Current issues in adolescent immunization. Vaccine. 2008 Aug 5;26(33):4120–34. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.04.055.

- Mackroth M, Irwin K, Vandelaer J, Hombach J, Eckert L. Immunizing school-age children and adolescents: experience from low- and middle-income countries. Vaccine. 2010;28(5):1138–47. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.11.008.

- Bruni L, Diaz M, Barrionuevo-Rosas L, Herrero R, Bray F, Bosch FX, De Sanjosé S, Castellsagué X. Global estimates of human papillomavirus vaccination coverage by region and income level: a pooled analysis. The Lancet Global Health. 2016 Jul 1;4(7):e453–63. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30099-7.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Prisma Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009 Jul 21;6(7):e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.

- World Health Organization. Adolescent health. www.who.int. 2021. [accessed 2021 Mar 21]. https://www.who.int/health-topics/adolescent-health#tab=tab_1

- Downes MJ, Brennan ML, Williams HC, Dean RS. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open. 2016 Dec 1;6(12):e011458. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011458.

- Caskey R, Lindau ST, Alexander GC. Knowledge and early adoption of the HPV vaccine among girls and young women: results of a national survey. J Adolescent Health. 2009 Nov 1;45(5):453–62. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.04.021.

- Choi HC, Leung GM, Woo PP, Jit M, Wu JT. Acceptability and uptake of female adolescent HPV vaccination in Hong Kong: a survey of mothers and adolescents. Vaccine. 2013 Dec 17;32(1):78–84. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.10.068.

- Costantino C, Amodio E, Vitale F, Trucchi C, Maida CM, Bono SE, Caracci F, Sannasardo CE, Scarpitta F, Vella C, et al. Human papilloma virus infection and vaccination: pre-post intervention analysis on knowledge, attitudes and willingness to vaccinate among preadolescents attending secondary schools of palermo, sicily. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Jan;17(15):5362. doi:10.3390/ijerph17155362.

- Herman R, McNutt L-A, Mehta M, Salmon DA, Bednarczyk RA, Shaw J. Vaccination perspectives among adolescents and their desired role in the decision-making process. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019 Mar 14;15(7–8):1752–59. doi:10.1080/21645515.2019.1571891.

- Huon J-F, Grégoire A, Meireles A, Lefebvre M, Péré M, Coutherut J, Biron C, Raffi F, Briend-Godet V, Mugo NR. Evaluation of the acceptability in France of the vaccine against papillomavirus (HPV) among middle and high school students and their parents. Plos One. 2020 Oct 22;15(10):e0234693. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0234693.

- Kreidl P, Breitwieser -M-M, Würzner R, Borena W. 14-year-old schoolchildren can consent to get vaccinated in tyrol, Austria: what do they know about diseases and vaccinations? Vaccines. 2020 Dec;8(4):610. doi:10.3390/vaccines8040610.

- Lavelle TA, Messonnier M, Stokley S, Kim D, Ramakrishnan A, Gebremariam A, Simon NJ, Rose AM, Prosser LA. Use of a choice survey to identify adult, adolescent and parent preferences for vaccination in the United States. J Patient-Reported Outcomes. 2019 Dec;3(1):1–2. doi:10.1186/s41687-019-0135-0.

- Nabirye J, Okwi LA, Nuwematsiko R, Kiwanuka G, Muneza F, Kamya C, Babirye JN. Health system factors influencing uptake of Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) vaccine among adolescent girls 9-15 years in Mbale District, Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2020 Dec 1;20(1):171. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-8302-z.

- Pelullo CP, Di Giuseppe G. Vaccinations among Italian adolescents: knowledge, attitude and behavior. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018 Jul 3;14(7):1566–72. doi:10.1080/21645515.2017.1421877.

- Wang B, Giles L, Afzali HH, Clarke M, Ratcliffe J, Chen G, Marshall H. Adolescent confidence in immunisation: assessing and comparing attitudes of adolescents and adults. Vaccine. 2016 Nov 4;34(46):5595–603. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.09.040.

- Griffin DS, Muhlbauer G, Griffin DO. Adolescents trust physicians for vaccine information more than their parents or religious leaders. Heliyon. 2018 Dec 1;4(12):e01006. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2018.e01006.

- Hilton S, Patterson C, Smith E, Bedford H, Hunt K. Teenagers’ understandings of and attitudes towards vaccines and vaccine-preventable diseases: a qualitative study. Vaccine. 2013 May 24;31(22):2543–50. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.04.023.

- Khurana S, Sipsma HL, Caskey RN. HPV vaccine acceptance among adolescent males and their parents in two suburban pediatric practices. Vaccine. 2015 Mar 24;33(13):1620–24. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.01.038.

- Maier C, Maier T, Neagu CE, Vlădăreanu R. Romanian adolescents’ knowledge and attitudes towards human papillomavirus infection and prophylactic vaccination. Eur J Obstetrics Gynecology Reproductive Biol. 2015 Dec 1;195:77–82. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2015.09.029.

- Marshall S, Sahm LJ, Moore AC, Fleming A. A systematic approach to map the adolescent human papillomavirus vaccine decision and identify intervention strategies to address vaccine hesitancy. Public Health. 2019 Dec;1(177):71–79. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2019.07.009.

- Pelucchi C, Esposito S, Galeone C, Semino M, Sabatini C, Picciolli I, Consolo S, Milani G, Principi N. Knowledge of human papillomavirus infection and its prevention among adolescents and parents in the greater Milan area, Northern Italy. BMC Public Health. 2010 Dec;10(1):1–2. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-378.

- Pennella RA, Ayers KA, Brandt HM. Understanding How Adolescents Think about the HPV Vaccine. Vaccines. 2020 Dec;8(4):693. doi:10.3390/vaccines8040693.

- Read DS, Joseph MA, Polishchuk V, Suss AL. Attitudes and perceptions of the HPV vaccine in Caribbean and African-American adolescent girls and their parents. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2010 Aug 1;23(4):242–45. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2010.02.002.

- Stöcker P, Dehnert M, Schuster M, Wichmann O, Deleré Y. Human papillomavirus vaccine uptake, knowledge and attitude among 10th grade students in Berlin, Germany, 2010. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013 Jan 1;9(1):74–82. doi:10.4161/hv.22192.

- Forsner M, Nilsson S, Finnström B, Mörelius E. Expectation prior to human papillomavirus vaccination: 11 to 12-Year-old girls’ written narratives. J Child Health Care. 2016 Sep;20(3):365–73. doi:10.1177/1367493515598646.

- Prue G, Shapiro G, Maybin R, Santin O, Lawler M. Knowledge and acceptance of human papillomavirus (HPV) and HPV vaccination in adolescent boys worldwide: a systematic review. J Cancer Policy. 2016 Dec 1;10:1–5. doi:10.1016/j.jcpo.2016.09.009.

- Hendry M, Lewis R, Clements A, Damery S, Wilkinson C. “HPV? Never heard of it!”: a systematic review of girls’ and parents’ information needs, views and preferences about human papillomavirus vaccination. Vaccine. 2013 Oct 25;31(45):5152–67. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.08.091.

- Patel H, Jeve YB, Sherman SM, Moss EL. Knowledge of human papillomavirus and the human papillomavirus vaccine in European adolescents: a systematic review. Sex Transm Infect. 2016 Sep 1;92(6):474–79. doi:10.1136/sextrans-2015-052341.

- London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, Vaccine Safety Net. the vaccine confidence project. The Vaccine Confidence Project. [accessed 2021 Jul 8]. https://www.vaccineconfidence.org

- Larson H, Alexandre De Figueiredo E, Karafillakis M, Rawal, health. State of vaccine confidence in the EU 2018 A report for the European Commission by. 2018. https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/vaccination/docs/2018_vaccine_confidence_en.pdf

- Special EUROBAROMETER 488 report Europeans’ attitudes towards vaccination fieldwork special eurobarometer 488 -wave EB91.2 –Kantar. 2019. https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/vaccination/docs/20190426_special-eurobarometer-sp488_en.pdf

- Cadeddu C, Daugbjerg S, Ricciardi W, Rosano A. Beliefs towards vaccination and trust in the scientific community in Italy. Vaccine. 2020 Sep 29;38(42):6609–17. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.07.076.

- Underwood NL, Gargano LM, Sales J, Vogt TM, Seib K, Hughes JM. Evaluation of educational interventions to enhance adolescent specific vaccination coverage. J Sch Health. 2019 Aug;89(8):603–11. doi:10.1111/josh.12786.

- Thomson A, Robinson K, Vallée-Tourangeau G. The 5As: a practical taxonomy for the determinants of vaccine uptake. Vaccine. 2016 Feb 17;34(8):1018–24. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.11.065.

- Silverman RD, Opel DJ, Omer SB. Vaccination over parental objection — should adolescents be allowed to consent to receiving vaccines? N Engl J Med. 2019;2:381.

- Agrawal S, Morain SR. Who calls the shots? The ethics of adolescentself-consent for HPV vaccination. J Med Ethics. 2018 Aug;44(8):531–35. doi:10.1136/medethics2017-104694.

- Gowda C, Schaffer SE, Dombkowski KJ, Dempsey AF. Amanda F dempsey understanding attitudes toward adolescent vaccination and the decision-making dynamic among adolescents, parents and providers. BMC Public Health. 2012 Jul 7;12(1):509. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-509.