ABSTRACT

Vaccination intent is foundational for effective COVID-19 vaccine campaigns. To understand factors and attitudes influencing COVID-19 vaccination intent in Black and White adults in the US south, we conducted a mixed-methods cross-sectional survey of 4512 adults enrolled in the Southern Community Cohort Study (SCCS), an ongoing study of racial and economic health disparities. Vaccination intent was measured as “If a vaccine to prevent COVID-19 became available to you, how likely are you to choose to get the COVID-19 vaccination?” with options of “very unlikely,” “somewhat unlikely,” “neither unlikely nor likely,” “somewhat likely,” and “very likely.” Reasons for intent, socio-demographic factors, preventive behaviors, and other factors were collected. 46% of participants had uncertain or low intent. Lower intent was associated with female gender, younger age, Black race, more spiritual/religious, lower perceived COVID-19 susceptibility, living in a greater deprivation area, lower reading ability, and lack of confidence in childhood vaccine safety or COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness or safety (p < .05 for all). Most factors were present in all racial/gender groups. Contextual influences, vaccine/vaccination specific issues, and personal/group influences were identified as reasons for low intent. Reasons for higher intent included preventing serious illness, life returning to normal, and recommendation of trusted messengers. Hesitancy was complex, suggesting tailored interventions may be required to address low intent.

Introduction

COVID-19 vaccination is a critical strategy to control the COVID-19 pandemic. This requires both effective vaccine distribution and individual willingness to be vaccinated. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy continues to range from 24–32% of adults in the United States (U.S) in most reports.Citation1–4

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated longstanding health disparities among Black, Hispanic, and other racial/ethnic minority populations who experience more COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths than non-Hispanic White populations.Citation5 In the U.S., COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy is somewhat higher among Hispanic adults, rural residents, and Black adults as well as other groups such as political affiliation.Citation6 Additionally, Black and Hispanic Americans have received disproportionately fewer COVID-19 vaccinations than White and Asian Americans.Citation7 In the southeastern U.S., COVID-19 vaccination rates have lagged national averages.Citation8 This raises the concern that a combination of vaccine hesitancy and inequities in vaccine distribution could worsen COVID-19 health disparities.

Identifying factors related to vaccine hesitancy among groups at greater risk of adverse outcomes, such as Black Americans, continues to be foundational to ensuring effective vaccination campaigns. Studies have largely been conducted among non-Hispanic White adults. Few studies have been conducted to understand extensive socio-demographic, health status, or social determinants of health and how these factors are related to vaccination intent among a racially diverse population and within the U.S. south. To fill these knowledge gaps, we assessed factors and attitudes influencing intent to receive a COVID-19 vaccine among 4,512 adults enrolled in the Southern Community Cohort Study (SCCS), an ongoing study of racial and economic health disparities within a population of adults in the southeastern U.S.

Methods

Study design and participants

The SCCS was established in 2002 to examine health disparities in cancer and other chronic diseases. Nearly 86,000 English-speaking adults between the ages of 40 and 79 years, two thirds Black, and living in 12 states in the southeastern U.S. were enrolled between March 2002 and September 2009. Additional study details are provided elsewhere and in the Appendix.Citation9,Citation10 The SCCS was approved by institutional review boards at Vanderbilt University Medical Center and Meharry Medical College. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

COVID-19 survey

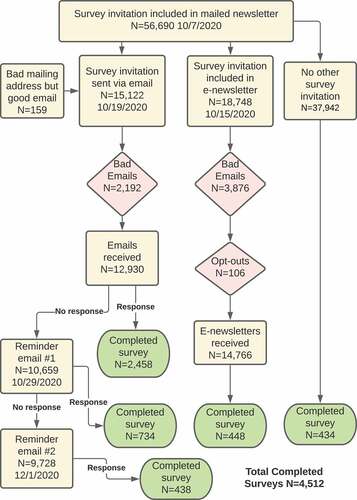

To assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on participants, we conducted a survey of COVID-19 infection, physical and emotional health status, COVID-19 related behaviors and beliefs, and household impacts. Questions cover vaccination attitudes and intentions including likelihood to choose a COVID-19 vaccine, the reasons for that choice, confidence in COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness and safety, past and planned receipt of an influenza vaccine, and attitude toward the safety of vaccines. ().Citation11–14 The survey was administered via an online platform which could be completed on a smartphone, tablet, or computer. Survey completion took approximately 20 minutes, for which participants received $10 compensation. Following a pilot of the questionnaire, the fielding period for the full survey was October 7 – December 14, 2020. Participants were notified of the survey via a mailed newsletter or direct e-mail (n = 15,122; ). In total, 4,512 completed the survey, including 3,630 participants who were emailed a direct invitation. Completion of all questions was achieved by 98.0% of participants. The American Association for Public Opinion Research Response Rate #1 among the participants emailed a direct invitation was 24.4%.Citation15

Geographic data

The residential address was used to determine the county, Census 2010 tract, and Census 2010 block group. This was linked to the Area Deprivation Index (ADI).Citation16,Citation17 We also linked urban-rural status based on the USDA 2013 Rural-Urban continuum codes, and Pandemic Vulnerability Index (PVI)Citation18,Citation19 and its components (PVI-social distancing, PVI-COVID-19 testing rates, PVI-residential density, PVI-air-pollution and others) from the day of survey completion. We also calculated transmittable case rate as the mean daily rate of new casesCitation20 per 100,000 in the county of residence in the 14-days prior to completing the survey.

Statistical analysis

The analysis was based on the 4,486 of the 4,512 participants who responded to the question “If a vaccine to prevent COVID-19 became available to you, how likely are you to choose to get the COVID-19 vaccination?” with a five-point ordinal scale: 1 = very unlikely, 2 = somewhat unlikely, 3 = neither unlikely nor likely, 4 = somewhat likely, and 5 = very likely. COVID-19 vaccination intent was evaluated as the five scale items or categorized into two groups: high intent (somewhat or very likely) and low intent (somewhat or very unlikely) both of which may have been combined with uncertain/undecided (neither likely not unlikely) intent. Analyses were conducted within the entire study population and within strata defined by age (<65, ≥ 65) and combinations of gender (male, female) and race (self-reported non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic White, all other racial/ethnic groups). Stratified analyses were not conducted for other racial or ethnic groups due to a small sample size.

Characteristics of the 4,486 participants or the communities in which they live, which were hypothesized to be related to vaccine likelihood, were summarized as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and as mean and standard deviation for continuous measures. The full list of variables assessed from the COVID-19 survey, SCCS follow-up surveys, or SCCS baseline survey is available in the Appendix materials.

Proportional odds models were used to evaluate the relationship between vaccination intent and 1) characteristics of the participant or the community in which they live, or 2) reasons someone would choose to be (among those with uncertain/high intent) or not to be vaccinated (among those uncertain/low intent). We first assessed the relationship with each individual variable in models adjusted for age, race, and gender. Factors which were statistically significantly or marginally significantly associated with likelihood were included in a full model using stepwise backward selection to reduce multicollinearity and to identify factors which were independently related to vaccination likelihood. Proportional odds assumption was visually assessed by plotting each predictor against the empirical logits.Citation21 Logistic regression was used to estimate the odds of low likelihood versus uncertain/high likelihood of vaccination including the factors in the final proportional odds model. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 with an alpha level of 0.05. We additionally analyzed which factors in the final proportional odds model (except for age, sex, and race) contributed most to participants’ attitude toward vaccination, by comparing models with or without the variable of interest and ranking the change in log likelihood per degree of freedom. We started with a proportional odds model adjusted for age, sex, and race, and sequentially add the variable which had the highest ranking of likelihood change at each step.

The qualitative inductive, deductive content analysis approach was used to analyze and rank the open-ended responses on the reasons one chooses not to vaccinate. A hierarchical coding system was developed based on Working Group Determinants of Vaccine Hesitancy Matrix and an initial review of the codes.Citation22 Three analysts independently coded responses. If new meanings emerged, codes were added or modified. Coding saturation was met when no new codes emerged. Codes were placed into categories (i.e., axial coding). If there were discrepancies in coding, there was discussion until an agreement was reached. Five responses were removed due to indeterminate meaning of response. A constant comparison method was used to compare codes and identify emerging themes. Microsoft Excel was used to summarize the data by determinants of vaccine hesitancy (i.e., themes) and their ranking of importance. To establish rigor, we used thick rich descriptions, peer debriefing, intercoder reliability, and investigator triangulation.Citation23

Results

Among the 4,486 participants who completed the survey, 66% were female, 38% were Black, 55% were White, and 59% were aged 65 or older. Participants ranged in age from 51 to 94 years old. Eighteen percent of participants reported a household income of less than $15,000, and 43% over $50,000. Most participants had completed high school or more (96%) and had at least one major medical condition (81%). Additional characteristics are detailed in and .

Table 1. Characteristics of study participants and COVID-19 vaccination intent

Approximately 54% of participants indicated high intent to receive COVID-19 vaccination. The proportion of participants who had a high intent varied by several characteristics. For example, White males had the highest intent (75%) while Black females (34%) reported lowest intent (). Several factors which were initially associated with intent in age-, gender-, and race-adjusted models were not independently associated with vaccine intent in the final multivariable model (e.g. health insurance status, employment status, self-reported health status, rural residence, and PVI-social distancing) (; ). In the final model (), participants who had a higher intent to be vaccinated were statistically significantly older (odds ratio (OR) = 0.99, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.98–1.00 per one year increase; p = .01), male (OR = 0.69, 95% CI: 0.60–0.79), White or all Other racial/ethnic groups (OR = 0.61, 95% CI 0.53–0.71 and OR = 0.68, 95%CI 0.52–0.89 respectively, versus Black participants), more highly educated (OR = 0.72, 95% CI 0.63–0.82 for college or above versus high school or some college), less spiritual/religious (OR = 0.67, 95%CI 0.55–0.81 for slightly/not at all spiritual and OR = 0.80, 95%CI 0.70–0.91 for fairly spiritual versus very spiritual/religious), had kidney disease (OR = 0.76, 95% CI 0.58–0.99 versus none), had more days of COVID-19 community protective behaviors (OR = 0.95, 95% CI 0.94–0.96), believed they were more likely to get COVID-19 (OR = 0.84, 95% CI 0.79–0.89), or had a high confidence in COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness or safety (OR = 0.64, 95%CI 0.58–0.71 for effectiveness and OR = 0.62, 95% CI 0.56–0.68 for safety). Factors associated with lower intent included no history or plan to have a flu vaccination in the past two influenza seasons (OR = 3.02, 95% CI 2.59–3.53), not believing childhood vaccines are safe (OR = 1.93, 95% CI 1.44–2.57), a lower reading ability (OR = 1.14, 95%CI 1.05–1.24), and residing in a community with a higher ADI (OR = 1.01, 95% CI 1.00–1.01 per one unit increase; p = .0002). In the ranking analysis for relative importance of each of the factors included in the final model, confidence in the safety of the vaccine, history of influenza vaccination, reading ability, chronic kidney disease, and educational attainment were the top five factors associated with vaccine intent (data not shown in table).

Table 2. Associations between individual and community characteristics and lower COVID-19 vaccination intent

In stratified analysis, many of the factors associated with vaccination intent persisted, however, they may not have been associated with intent within all strata. For example, high educational attainment was associated with intent among women but not among men. Factors related to confidence in vaccines in general and COVID-19 vaccine specifically (had or will have a flu vaccine in past two years, belief that childhood vaccines are safe, and confidence in COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness and safety) remained strongly associated with COVID-19 vaccination intent among all racial/gender, age, and rural/urban () groups.

Reasons participants would get the vaccine were evaluated among those who indicated they had uncertain/high intent (n = 3,109, 69%; ; ). Most participants cited protection for themselves and/or their families as reasons for getting the vaccine (≥93%). A majority of participants would get the vaccine based on the recommendation of a medical professional (88%) but relatively fewer would do so based on a political or religious leader (range of 7–22% across groups). The recommendation of friends and family was also a common reason to have the vaccination (43%). Preventing serious illness (OR 2.29, 95% CI 1.69–3.12), making efforts for life to go back to normal (OR 2.23, 95% CI 1.79–2.79), recommendation of political leaders (OR 1.80, 95% CI 1.38–2.34), and belief in vaccine safety (OR 2.64, 95% CI 2.10–3.31) were reasons to be vaccinated that were independently, significantly, and strongly associated with higher vaccination intent within this group with uncertain/high intent. Unlike urban residents, the recommendation of medical professionals and protection for self or family were not associated with intent among rural residents.

Table 3. Associations between COVID-19 vaccination intent and reasons for getting or not getting a COVID-19 vaccine

Among participants who had low/uncertain intent (n = 2078, 46%), concern about side effects from the vaccine was the most common reason selected (80%), followed by concern about being infected with COVID-19 by the vaccine (50%), and distrust in the efficacy of vaccines (35%) (; ). Concern about side effects and the cost of vaccine were associated with higher intent in this group (p < .05). The open-ended other reason (29%; regardless of explanation) was the only reason showing a lower intent (OR 1.35, 95% CI 1.05–1.73). These three reasons were also the only reasons significantly associated with intent among either urban or rural residents.

In content analysis of the open-ended reasons (), three themes emerged to describe factors contributing to vaccine hesitancy: (1) contextual influences; (2) vaccine/vaccination specific issues; and (3) individual/group influences.

Table 4. Qualitative coding and quantification of free text responses of other reasons to not get a COVID-19 vaccine among those with low/uncertain intent

The theme vaccine/vaccination specific issues yielded the most responses (n = 305, 61%) among those with uncertain/low intent. The most common concern was the reliability of the research process (n = 166) perceiving it was “rushed” or methods for development were unreliable, substandard, or incomplete. The risk/benefit associated with vaccination was the second most cited contextual concern (n = 107). Many wanted to know the side effects, efficacy and/or effectiveness, and vaccine ingredients. Other concerns were “newness” of the vaccine (n = 14), costs (n = 1), and lack of or need for a recommendation (n = 17). Participants preferred a recommendation from scientists, medical professionals, or government/political leaders.

Individual/group influences was the second most common theme (n = 110, 22.0%). Responses primarily reflected participant perceptions or beliefs toward the vaccine (n = 65, 13%). Fear of the vaccine’s side effects, and conspiracy theories were common. Example conspiracy theories were “I believe it will have a tracking devise (sic) in it,” “I do not want to be controlled with DNA change,” or “genocide on black people.” Other concerns were contraindications such as allergic reactions. Some believed in natural immunity or natural remedies. Others stated lack of/need for knowledge (22, 4.4%) on the vaccine, did not take vaccines, or had low perceived susceptibility (23, 4.6%).

Contextual influences are “influences arising due to historic, socio-cultural, environmental, health system/institutional, economic, or political factors.” While this theme has the least responses (n = 84, 16.8%), many participants state “there is too much political involvement in the vaccine [development and approval]” (n = 63, 12.6%). Some indicate distrust in the government and pharmaceutical companies (n = 8). A few participants further cited historical mistrust and abuse in research (n = 5, 1.0%) and their distrust in the communication surrounding the vaccine (n = 2, 0.4%). Lastly, spiritual beliefs influence participant decision-making. Example responses are “my faith in God,” “religious preference,” or “I trust the word of God for my health.”

Discussion

This large study of predominantly Black and White adults identified characteristics of participants with low and high vaccine intent as well as beliefs that influenced intent. Similar to past studies,Citation24–29 several socio-demographic factors were associated with lower intent for COVID-19 vaccination- namely, younger age, female, Black, or having high school or some college education. The increased levels of vaccine hesitancy among Black compared to White participants has been well-documented although differences are not fully explained. General vaccine hesitancy among Black Americans has been shown to be deeply rooted in mistrust in healthcare systems, the research process, and pharmaceutical companies.Citation30,Citation31 Mistrust is built in part upon inequities in the social determinants of health. For example, roughly 20% of Black Americans have experienced discrimination in a health care setting which is similar to the prevalence reported by Black participants in this study.Citation32,Citation33 Historical research abuses have imprinted skepticism and fear.Citation34,Citation35 In our sample, politics around COVID-19 vaccination such as distrust of the presidential administration in fall of 2020 further fueled vaccine hesitancy. Past research indicates lower levels of trust in government negatively influences vaccine confidence.Citation36 Further, Black participants were less likely to perceive getting the vaccine as the best way to avoid serious illness. Future work should explore the behaviors perceived most effective in preventing the severity of COVID-19 among Black Americans with lower perceived susceptibility to COVID-19 in order to address misinformation around COVID-19 and the vaccine.

Personal practices and beliefs about vaccines, such as past influenza vaccination and childhood vaccination, were strongly related to intent to vaccinate within all subgroups. This suggests that interventions to increase COVID-19 vaccination must overcome these long-held beliefs and are important for all communities. It is also consistent with previous studies which have identified anti-vaccine attitudes and beliefs as barriers to vaccination.Citation24 Our study also found reading ability, history of engaging in COVID-19 preventive behaviors, and spirituality/religiosity were negatively associated with COVID-19 vaccine uptake. Individuals with a lower reading ability, even adjusted for educational attainment, may be less likely to understand COVID-19, its severity, and the purpose and development process of the vaccine. Individuals with no history of engagement in COVID-19 preventive behaviors could be less likely to adopt a new preventive behavior like COVID-19 vaccination.Citation37 The observation of spirituality/religiosity being associated with lower likelihood of uptake is consistent with past studies.Citation38,Citation39 This was primarily limited to older adults and White males. Low perceived risk and high-level perception of surviving COVID-19 were negative predictive factors of COVID-19 vaccination. These findings and current literatureCitation40,Citation41 provide intervention targets to apply to vaccine hesitancy that could increase uptake.

COVID-19 vaccination rates are lagging behind in rural areas of the U.S., compared to urban locations or in areas with greater social vulnerability.Citation42 However, after adjustment for other factors, rural residence was not independently related to vaccine intent in this study. In fact, most of the associations related to intent were present in both rural and urban residents, suggesting that factors which influence intent are shared across geographic areas. Likewise, most other community-level characteristics were unrelated to intent including the Pandemic Vulnerability Index. The notable exception was the relationship to lower intent for those living in a community with higher deprivation despite adjustment for individual-level socio-demographic characteristics. This suggests that under-resourced communities may have a greater need for more extensive interventions to overcome barriers to vaccination.

According to MacDonald et al., vaccine hesitancy exists on a continuum ranging from full acceptance to outright refusal.Citation22 The degree of hesitancy was measured by a five-point bipolar scale with both ends reflecting either positive or negative intent and a midpoint that reflected respondents were uncertain or undecided in their intent. Our study further identified if degree of hesitancy was determined by different factors among these adults. Protection of self and family and the recommendation of a healthcare provider were most common reasons for those with uncertain or high vaccination intent. Many also indicated that the recommendation of other trusted messengers (family and friends, political leaders, religious leaders) would influence their intent. However, these reasons were not universally important. Likewise, many of those with low or uncertain intent cited side effects, concern about being infected with COVID-19 from the vaccine, or concern that the vaccine will not work as common barriers. In our open-ended statements, participants describe vaccine specific issues (e.g., conspiracy theories, lack of information), individual influences (e.g., beliefs in natural immunity and remedies), and contextual factors (e.g., degree of political involvement in vaccine development process, distrust in pharmaceutical companies, healthcare systems, and research processes) as barriers, some of which have also been observed in other studies.Citation24,Citation43 Collectively, findings demonstrate the complexity of vaccine hesitancy and indicate that addressing a single barrier will not address vaccine hesitancy for a majority of individuals. Intervention targets or approaches should be tailored to reasons for vaccine intent by degree of hesitancy. For example, interventions including trusted messengers may need to involve a variety of messengers based on characteristics of the target population such as religiosity which was associated with lower intent in this study and has been associated with lower likelihood of uptake in past studies.Citation38,Citation39

There are several strengths of the study. First, it was conducted within a well-characterized population across multiple U.S. states. The study also includes a large sample size, which permitted simultaneous evaluation of potential individual-level and community-level factors and subgroups. Limitations include a relatively low survey response rate. Also, responders had a somewhat higher educational attainment than non-responders. However, responders are likely underrepresented in other studies and still represent a wide distribution of many socio-demographic and other factors. We were unable to evaluate racial/ethnic minority groups other than Black Americans. The survey overlapped the time period when vaccine efficacy was first reported which may have affected responses in an unknown manner. Although we were able to evaluate many factors, we were not able to evaluate every potential factor reported to be related to vaccine intent such as political affiliation. Finally, the intention to vaccinate does not always mean an individual will get vaccinated. This will be evaluated in this population in future work.

Conclusions

In this large, mixed-methods study, we identified several socio-demographic and other factors that were independently associated with COVID-19 vaccination intent in the months leading up to vaccine availability in the U.S. Hesitancy was complex with many observed associations and variation in the associations among socio-demographic groups. Participants also cited many concerns such as safety, side effects, efficacy, and a distrust of the vaccine development process as reasons for their hesitancy. Thus, addressing these factors, recommendations of trusted messengers, and identification of additional factors which are associated with this hesitancy continue to be important for developing tailored interventions to increase vaccination rates in the U.S.

Supplemental Material

Download ()Disclosure statement

K. Edwards is consultant to Bionet and IBM, and Member of the Data Safety and Monitoring Board for Sanofi, X-4 Pharma, Seqirus, Moderna, Pfizer, Merck, and Roche. J. Cunningham-Erves, C. Mayer, X. Han, L. Fike, C. Yu, P. Tousey, D. Schlundt, D. Gupta, M. Mumma, D. Walkley, M. Steinwandel, L. Lipworth, M. Sanderson, X. Shu, M. Shrubsole have nothing to disclose.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website at https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2021.1984134

Additional information

Funding

References

- Hamel L, Kirzinger A, Lopes L, Sparks G, Kearney A, Stokes M, Brodie M. KFF COVID-19 vaccine monitor May 2021. [accessed 2021 Jun 17]. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/poll-finding/kff-covid-19-vaccine-monitor-may-2021/

- Pew Research Center. Growing share of Americans say they plan to get a COVID-19 vaccine – or already have [Internet]; 2021 [accessed 2021 Jun 17]. https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2021/03/05/growing-share-of-americans-say-they-plan-to-get-a-covid-19-vaccine-or-already-have/

- Agiesta J CNN poll: about a quarter of adults say they won’t try to get a Covid-19 vaccine [Internet]. CNN [ accessed 2021 Jun 17]. https://www.cnn.com/2021/04/29/politics/cnn-poll-covid-vaccines/index.html

- Jones J COVID-19 vaccine-reluctant in U.S. likely to stay that way [Internet]. Gallup.com 2021 [accessed 2021 Jun 17]. https://news.gallup.com/poll/350720/covid-vaccine-reluctant-likely-stay.aspx

- CDC. Cases, data, and surveillance [Internet]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2020 [ accessed 2021 Jun 17]. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html

- Hamel L, Lopes L, Kearney A, Brodie M KFF COVID-19 vaccine monitor: March 2021 [Internet]; 2021 [accessed 2021 Apr 20]. https://kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/poll-finding/kff-covid-19-vaccine-monitor-march-2021/

- CDC. COVID data tracker: demographic trends of people receiving COVID-19 vaccinations in the United States [Internet]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2021 [ accessed 2021 Jun 17]. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#vaccination-demographics-trends

- CDC. COVID data tracker: COVID-19 vaccinations in the United States [Internet]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2021 [ accessed 2021 Jun 17]. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#vaccinations

- Signorello LB, Hargreaves MK, Blot WJ. The southern community cohort study: investigating health disparities. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(1A):26–37. doi:10.1353/hpu.0.0245.

- Signorello LB, Hargreaves MK, Steinwandel MD, Zheng W, Cai Q, Schlundt DG, Buchowski MS, Arnold CW, McLaughlin JK, Blot WJ. Southern community cohort study: establishing a cohort to investigate health disparities. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97:972–79.

- Hamel L, Kirzinger A, Muñana C, Brodie M KFF COVID-19 vaccine monitor: December 2020 [Internet]; 2020 [accessed 2021 Jan 19]. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/report/kff-covid-19-vaccine-monitor-december-2020/

- The associated press-NORC center for public affairs research. The May 2020 AP-NORC Center Poll [Internet]. 2020. [accessed 2021 May 6] https://apnorc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/may-topline.pdf

- MESA COVID-19 [Internet]. [ accessed 2021 May 6]. https://www.mesa-nhlbi.org/MESACOVID19/

- The economist/YouGov poll [Internet]. 2020 [accessed 2021 May 6]. https://docs.cdn.yougov.com/t0qsgk3wcg/econTabReport.pdf

- American association for public opinion research response. Standard Definitions - AAPOR [Internet]. [accessed 2021 Jun 11]. https://www.aapor.org/Standards-Ethics/Standard-Definitions-(1).aspx

- Kind AJH, Buckingham WR. Making neighborhood-disadvantage metrics accessible - the neighborhood atlas. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(26):2456–58. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1802313.

- University of Wisconsin School of Medicine Public Health. Neighborhood atlas [Internet]. 2021 Area Deprivation Index v2.02021 [accessed 2021 Feb 9]. https://www.neighborhoodatlas.medicine.wisc.edu/

- National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. Pandemic Vulnerability Index Model 11.2 [Internet]. COVID-19 Pandemic Vulnerability Index (PVI) Dashboard 2021 [ accessed 2021 Feb 9]. https://github.com/COVID19PVI/data

- Marvel SW, House JS, Wheeler M, Song K, Zhou Y-H, Wright FA, Chiu WA, Rusyn I, Motsinger-Reif A, Reif DM, et al. Pandemic vulnerability index (PVI) dashboard: monitoring county-level vulnerability using visualization, statistical modeling, and machine learning. Environ Health Perspect. 2021;129(1):017701. doi:10.1289/EHP8690.

- Coronavirus resource center [Internet]. Johns Hopkins University & Medicine [accessed 2021 Feb 8]; Available from: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/

- SAS Institute Inc. SAS note 37944: plots to assess the proportional odds assumption in an ordinal logistic model [Internet]. 2012 [accessed 2021 Apr 1]. http://support.sas.com/kb/37944

- MacDonald NE. Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4161–64. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036.

- Creswell JW, Miller DL. Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Theory Pract. 2000;39(3):124–30. doi:10.1207/s15430421tip3903_2.

- Fisher KA, Bloomstone SJ, Walder J, Crawford S, Fouayzi H, Mazor KM. Attitudes toward a potential SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: a survey of U.S. adults. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(12):964–73. doi:10.7326/M20-3569.

- Khubchandani J, Sharma S, Price JH, Wiblishauser MJ, Sharma M, Webb FJ. COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy in the United States: a rapid national assessment. J Community Health. 2021;46(2):270–77. doi:10.1007/s10900-020-00958-x.

- Malani PN, Solway E, Kullgren JT. Older adults’ perspectives on a COVID-19 vaccine. JAMA Health Forum. 2020;1(12):e201539. doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2020.1539.

- Stern MF Willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccination among incarcerated or detained persons in correctional and detention facilities — four states, September–December 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Internet]; 70 2021 [accessed 2021 Apr 25]. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/wr/mm7013a3.htm

- Nguyen KH. COVID-19 vaccination intent, perceptions, and reasons for not vaccinating among groups prioritized for early vaccination — United States, September and December 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Internet]; 70 2021 [cited 2021 Apr 25]. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/wr/mm7006e3.htm

- Latkin CA, Dayton L, Yi G, Colon B, Kong X, Camacho-Rivera M. Mask usage, social distancing, racial, and gender correlates of COVID-19 vaccine intentions among adults in the US. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(2):e0246970. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0246970.

- Quinn SC, Jamison AM, An J, Hancock GR, Freimuth VS. Measuring vaccine hesitancy, confidence, trust and flu vaccine uptake: results of a national survey of White and African American adults. Vaccine. 2019;37(9):1168–73. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.01.033.

- Quinn S, Jamison A, Musa D, Hilyard K, Freimuth V. Exploring the continuum of vaccine hesitancy between African American and white adults: results of a qualitative study. PLoS Curr. 2016;8: ecurrents.outbreaks.3e4a5ea39d8620494e2a2c874a3c4201.

- Hall GL, Heath M Poor medication adherence in African Americans is a matter of trust. J Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities [Internet] 2020 [accessed 2021 Apr 6]. http://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-020-00850-3

- Hamel L, Lopes L, Muñana C, Artiga S, Brodie M Race, health, and COVID-19: the views and experiences of black Americans. KFF/Undefeated Survey on Race and Health; 2020.

- Scharff DP, Mathews KJ, Jackson P, Hoffsuemmer J, Martin E, Edwards D. More than Tuskegee: understanding mistrust about research participation. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(3):879–97. doi:10.1353/hpu.0.0323.

- Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, Williams MV, Moody-Ayers S. Attitudes and beliefs of African Americans toward participation in medical research. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14(9):537–46. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.07048.x.

- Mesch GS, Schwirian KP. Social and political determinants of vaccine hesitancy: lessons learned from the H1N1 pandemic of 2009-2010. Am J Infect Control. 2015;43(11):1161–65. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2015.06.031.

- Pampel FC, Krueger PM, Denney JT. Socioeconomic disparities in health behaviors. Annu Rev Sociol. 2010;36(1):349–70. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102529.

- Olagoke AA, Olagoke OO, Hughes AM. Intention to vaccinate against the novel 2019 coronavirus disease: the role of health locus of control and religiosity. J Relig Health. 2021;60(1):65–80. doi:10.1007/s10943-020-01090-9.

- Mahdi S, Ghannam O, Watson S, Padela AI. Predictors of physician recommendation for ethically controversial medical procedures: findings from an exploratory national survey of American Muslim physicians. J Relig Health. 2016;55(2):403–21. doi:10.1007/s10943-015-0154-y.

- Caserotti M, Girardi P, Rubaltelli E, Tasso A, Lotto L, Gavaruzzi T. Associations of COVID-19 risk perception with vaccine hesitancy over time for Italian residents. Soc Sci Med. 2021;272:113688. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113688.

- Guidry JPD, Laestadius LI, Vraga EK, Miller CA, Perrin PB, Burton CW, Ryan M, Fuemmeler BF, Carlyle KE. Willingness to get the COVID-19 vaccine with and without emergency use authorization. Am J Infect Control. 2021;49(2):137–42. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2020.11.018.

- Hughes MM County-level COVID-19 vaccination coverage and social vulnerability — United States, December 14, 2020–March 1, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Internet]; 70 2021 [cited 2021 Apr 25]. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/wr/mm7012e1.htm

- Pogue K, Jensen JL, Stancil CK, Ferguson DG, Hughes SJ, Mello EJ, Burgess R, Berges BK, Quaye A, Poole BD. Influences on attitudes regarding potential COVID-19 vaccination in the United States. Vaccines (Basel). 2020;8(4):582. doi:10.3390/vaccines8040582.

Appendix methods

Southern Community Cohort Study

Recruitment for the SCCS was conducted primarily (86%) through Community Health Centers (CHCs), institutions which largely provide health care and preventive services to low-income and uninsured persons. Approximately 14% of participants were recruited via an age-, sex-, and race-stratified random sample of the general population. Study participants completed a survey at baseline and up to four additional surveys during the SCCS follow-up. In this analysis we incorporated responses from these prior surveys including education, spirituality/religiosity, income, discrimination in medical care, reading ability, needing help to read medical materials, and confidence filling out medical forms. In addition, chronic disease history and BMI from the most recently completed survey were used wherever missing from the COVID-19 survey (all survey instruments available at https://www.southerncommunitystudy.org/questionnaires.html).

COVID-19 Survey

A pilot of the COVID-19 survey was conducted between 7/20/2020 and 9/30/2020. A total of 400 SCCS participants with an e-mail address on file who completed the 3rd or 4th follow-up parent study survey were emailed a personalized e-mail invitation on 07/20/2020 to complete the survey using a unique URL to the survey consent landing page. Non-responders received up to two reminder e-mails (on 07/23/2020 and 07/28/2020) and 158 were also mailed a reminder letter on 08/3/2020. In all, 106 participants completed the pilot survey and 13 participants recorded refusal of the survey on the consent page. As a result of the pilot, the questionnaire was updated to expand questions about vaccine hesitancy.

For the primary COVID-19 survey, participants were invited by two primary methods. First, SCCS participants routinely receive an annual mailed newsletter updating participants about study activities. Included on the mailed 2020 newsletter was an invitation to complete the COVID-19 impact survey by texting a code to an SCCS number or by using a provided URL (n = 56,690). Both options led to a study website landing page. In addition to a mailed newsletter, participants with an e-mail address on file were also emailed an e-newsletter that included a unique-to-the-participant URL (n = 18,748). In the second pathway and in addition to an e-newsletter, SCCS participants with an e-mail address on file who had not yet completed the COVID-19 impact survey and who had completed either the 3rd or 4th follow-up parent study survey were emailed a personalized invitation to complete the survey (n = 15,122). Non-responders received up to two reminder e-mails. Timings of the mailings are shown in . Participants were considered to have completed the survey if they reached question 162 of 205.

Geocoded addresses were matched to the street level for 91% of residential addresses. ZIP code centroid was used for the 9% of addresses that did not match to a street address, or where only a post office box or rural delivery route was provided.

Statistical analysis

Variables which were assessed for association with vaccination intent included age (years), gender (male/female), race (Black, White, All other racial/ethnic groups including unknown), income (less than $15,000, $15,000-$49,999, over $50,000), education (less than high school, high school or some college, college or above), household composition (alone/with adults no children/with children no adults/with children and adults), health insurance status (any Medicare/Medicaid, any private and not Medicare/Medicaid, only military or others, no insurance), self-reported history of diabetes (yes/no), self-reported history of cardiovascular disease and/or hypertension (yes/no), self-reported history of chronic lung disease (yes/no), self-reported history of kidney disease (yes/no), self-reported history of autoimmune disease (yes/no), self-reported active cancer treatment (yes/no), BMI, self-reported health status (excellent, very good, good, fair, poor), current smoking status (current or not), current employment status (not currently employed, currently employed), hours working within 6 feet of others (0 hours, 0.1 to < 1 hour, 1 to less than 3 hours, 3 or more hours), COVID-19 testing status for self and household members (never/negative/ever positive), likelihood of contracting or surviving COVID-19 (as scales of 1 to 5 for very unlikely, somewhat unlikely, neither unlikely nor likely, somewhat likely, very likely), COVID-19 personal preventive behaviors score (sum of number of days per week for washing hands or using sanitizer frequently, cleaning touched surfaces, wearing face masks, and keeping 6 feet away from others; range of 0–28 days), COVID-19 community protective behaviors score (sum of number of days per week for avoiding large gatherings, avoiding restaurants or bars, and following government guidelines, range of 0 to 21), personal confidence on effectiveness or safety of COVID-19 vaccines (as scales of 1 to 5 for very unlikely, somewhat unlikely, neither unlikely nor likely, somewhat likely, very likely), personal attitude toward safety of childhood vaccination (safe/not safe), ever personally experienced discrimination in medical care due to race or socioeconomic status (yes/no), spirituality (very, fairly, slightly, not at all), self-reported reading ability (as a scale of 1 to 5 for excellent/very good/good/okay/poor), confidence in filling out medical forms (as a scale of 1 to 5 for extremely/quite a bit/somewhat/a little bit/not at all), help needed with reading materials from doctors (yes/no), influenza vaccine status in the last two flu seasons (vaccinated/not vaccinated), urban/rural resident, ADI (1–100) and other demographic factors.]

Appendix Table 1. Survey questions and sources

Appendix Table 2. Characteristics of study participants among racial/gender and age groups

Appendix Table 3A. Simple associations between individual and community characteristics and intent to receive COVID-19 vaccination – Black females

Appendix Table 3B. Simple associations between individual and community characteristics and intent to receive COVID-19 Vaccination – White Females

Appendix Table 3C. Simple associations between individual and community characteristics and intent to receive COVID-19 vaccination – Black males

Appendix Table 3D. Simple associations between individual and community characteristics and intent to receive COVID-19 vaccination – White males

Appendix Table 3E. Simple associations between individual and community characteristics and intent to receive COVID-19 vaccination – all other racial/ethnic groups

Appendix Table 3F. Simple associations between individual and community characteristics and intent to receive COVID-19 vaccination – age <65

Appendix Table 3G. Simple associations between individual and community characteristics and intent to receive COVID-19 vaccination – age ≥65

Appendix Table 3H. Simple associations between individual and community characteristics and intent to receive COVID-19 vaccination – rural residents

Appendix Table 3I. Simple associations between individual and community characteristics and intent to receive COVID-19 vaccination – urban residents

Appendix Table 4A Simple Associations Between COVID-19 Vaccination Intent and Reasons for Getting or Not Getting a COVID-19 Vaccine – Overall

Appendix Table 4B Simple associations between COVID-19 vaccination intent and reasons for getting or not getting a COVID-19 vaccine among racial/gender groups

Appendix Table 4C Simple associations between COVID-19 vaccination intent and reasons for getting or not getting a COVID-19 vaccine among age groups

Appendix Table 4D Simple associations between COVID-19 vaccination intent and reasons for getting or not getting a COVID-19 vaccine among rural and urban residents