ABSTRACT

Background

Individuals working with biological samples in Indian universities are at risk for occupational exposure to hepatitis B virus (HBV) and may not be vaccinated.

Aim

We documented the need for HBV vaccination in students and others, developed an institutional HBV vaccination program, delivered HBV vaccines, and then assessed the determinants of vaccine uptake.

Methods

Over a year, we conducted a prospective cohort study documenting the need for HBV vaccination in people working with biological materials in a major Indian institution, developed a HBV vaccination program, delivered HBV vaccines, and assessed determinants of vaccine uptake. In August 2018, a needs assessment determined exposure to blood, body fluids, and other potentially infectious material in the research setting, followed in September by a cross-sectional survey on HBV vaccination status. Institutional approval for vaccination followed in October, and vaccine clinics began in February 2019. In September, a follow-up survey investigated determinants of vaccine uptake.

Results

A total of 185 people participated in the baseline HBV vaccination status survey. Only 26% of students, staff, and faculty were fully vaccinated for HBV. Over 70% of the target group came forward for vaccination and >90% completed all doses. Getting vaccinated with peers strongly influenced vaccine uptake, as did availability of free vaccine, onsite clinics, and reminders.

Conclusion

HBV vaccination programs for individuals at occupational risk are needed in Indian academic institutions beyond medical schools as part of institutional biosafety programs.

Introduction

Preventing occupational transmission of hepatitis B virus (HBV) from blood, body fluids, and other potentially infectious material (OPIM) is central to biosafety, and regulated by occupational health statutes in the United States, the European Union, and now in India.Citation1–3 The focus of occupational exposure to HBV in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) has been on preventing healthcare-related needle stick injuries (NSI); however, research settings are also sources of occupational exposure to blood-borne pathogens (BPP) like HBV.Citation4,Citation5

The revised Bloodborne Pathogen Standard addresses this fact. Not just blood and body fluids but human cell lines and non-human primate cell lines also pose risk for occupational transmission of BPP.Citation6

India has invested in biotechnology research, resulting in increased numbers of young adults entering laboratory-based training programs, with exposure to BPP.Citation7,Citation8 HBV vaccination only became a part of the Universal Indian immunization program (UIP) in 2011, with all babies getting vaccinated at birth, six, ten, and fourteen weeks.Citation9 Coverage in children under five is about 55%.Citation10 There has been no catch-up vaccination program for adolescents, so young Indian adults now entering biotechnology research may not be vaccinated.

India has 40 million people with chronic hepatitis B. A quarter of whom may develop cirrhosis or liver cancer.Citation11,Citation12

The 2016 Government of India (GOI) Biomedical Waste Handling Rules define biomedical waste, its handling, and disposal, and mandate HBV vaccination for all individuals with occupational exposure.Citation3 This gives Indian universities a framework to build systems for biosafety with programs to vaccinate young adults and others at risk for occupational exposure to HBV.

Little systematic research exists on needs assessments and vaccine uptake for HBV in Indian institutions outside of medical colleges. This study aims at assessing the need for HBV vaccines for people working with biological materials in a major Indian institution, and identifies factors affecting vaccine uptake. We conducted a prospective cohort study to document the needs assessment for HBV vaccination in students and others, developed an institutional HBV vaccination program, delivered HBV vaccines, and then assessed the determinants of vaccine uptake.

Methods

Study setting and timeline

We conducted this work at the Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur (IIT-Kgp), a major research institute of eminence in India with 15,000 students.Citation13 In August 2018, we conducted an online departmental needs assessment in the School of Medical Science and Technology (SMST) at IIT-Kgp with 4 questions distributed to all faculty (n = 10) to determine exposure of their research groups to blood, body fluids, and OPIM, including human and non-human primate cell lines. The American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), the global resource for reference cell lines states, “it is strongly recommended that all human and other primate cell lines be handled at the same biosafety level as a cell line known to carry HIV or hepatitis virus.”Citation14

In September 2018 a cross-sectional survey was given to all students, faculty, and staff in SMST (n = 121) to determine HBV vaccination status, and willingness to get vaccinated. We requested participants to upload proof of vaccination to ensure data reliability. The survey was administered with Google forms in English, or in-person in Bengali or Hindi, by a social worker, depending on participant literacy. The results were reviewed by the administration, and an Institutional office order supporting HBV vaccines for all individuals with occupational exposure was issued by the Registrar in October 2018. Vaccines, however, were not institutionally mandated.

Vaccine procurement, clinic planning, and awareness generation happened between November 2018 and January 2019. Vaccination clinics started in February 2019, staffed by a physician, social worker, and nurse. Vaccines were offered for free. Vaccination appointments were flexible, reminders were sent by e-mail, and phone. Coordination was done by the department. Posters on need for HBV vaccination were hung.

In August 2019, the same survey was sent to incoming students in SMST (n = 43) and a second department (n = 21) involved in research with biological materials, to determine HBV vaccination status and willingness to get vaccinated.

In September 2019, a follow-up survey was sent to all vaccine clinic participants (n = 64) to understand determinants of vaccine uptake. It was administered online using Google forms or in-person. Vaccination clinics continued through March 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown in India sent students home.

Ethics statement

Approval from the Institute Ethics Committee of IIT-KGP was taken. Participants provided written informed consent.

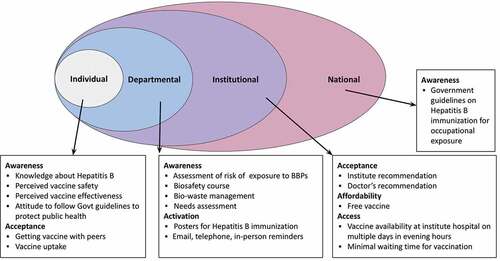

Determinants of vaccine uptake

We assessed determinants of vaccine uptake in September 2019, using the 5A model developed by Thompson et al.: access, affordability, acceptance, activation, and awareness.Citation15 This widely used framework helps understand the interplay of organizational, structural, individual, and socio-cultural factors in determining vaccine uptake.Citation16 Questions used a five-point Likert scale. There was one open-ended question. Three questions addressed access, 2 each affordability and acceptance, 5 activation, and 11 awareness. The questionnaire was pretested on 8 participants and modified for ease of understanding.

Access is the ability of a person to reach or be reached by a vaccine. The participants were asked about the importance of getting vaccinated at IIT-KGP, the availability of multiple slots and evening slots, in their decision to get vaccinated (: questions 1 to 3).

Affordability, the ability to afford the vaccine due to financial and nonfinancial costs, was assessed by asking participants about the importance of getting the vaccine for free and during working hours (: questions 4 and 5).

Acceptance is the degree to which individuals accept, refuse, or question vaccines. The participants were asked the importance of getting vaccinated with peers, and the recommendation of doctors and others in their decision (: questions 6 and 7).

Activation describes the nudge toward vaccine uptake. We assessed the importance of phone calls, e-mail, in-person reminders, and posters (: questions 8 to 12).

Awareness, the individual’s knowledge about vaccines, and their benefits and risks were assessed, by eleven statements ().

Definitions and data analysis

Data were extracted using Google Sheets. Baseline vaccination status was categorized as follows: fully vaccinated, not vaccinated, incompletely vaccinated, vaccinated dose unknown, and vaccination status unknown.Citation17 To be fully vaccinated, individuals needed three doses of HBV vaccine. Incompletely vaccinated included those with one or two doses. Vaccinated doses unknown were those vaccinated individuals who did not know the number of doses they had received. Vaccination status unknown were those who did not know if they were vaccinated. Participants were contacted by phone and e-mail for clarification.

Proportions were calculated for vaccination categories and uptake. Odds ratios for being unvaccinated by occupation were calculated using logistic regression, and the Z-test was used to calculate two-sided p-values for the difference of proportions using STATA 13.

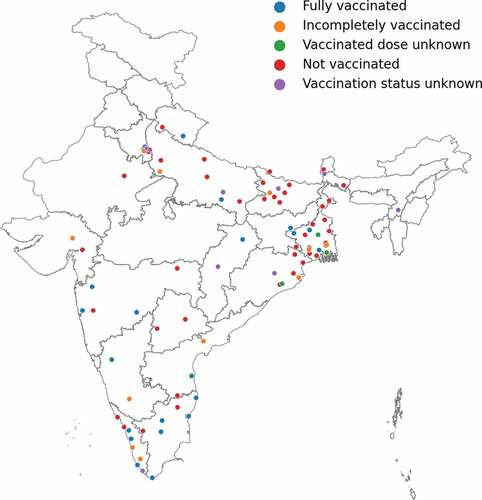

Map construction

The shape file for India was obtained from Community Created Maps of India,Citation18 and the map was drawn using the Geopandas library of Python. The scatter plot of location of participants was made using python libraries, Matplotlib, and Seaborn.

Results

The August 2018 needs assessment found that individuals in all research labs in SMST had occupational exposure to blood, body fluids, or OPIM. A total of 185 individuals participated in baseline HBV vaccination status surveys held at two points: 121 in 2018, and 64 in 2019.

Demographic characteristics

shows the demographic characteristics of the 185 participants of the HBV vaccination status surveys from 2018 and 2019. Fifty-nine percent (109) were male. The majority, 137 (74%), were 18 to 29 years but ranged from 18 to 64 years. The cohort included faculty, medical graduates, master’s students, Ph.D. students, postdoctoral fellows, skilled, and unskilled staff. While most, 129 (70%), were from Eastern India, participants came from all over the country and Nepal ().

Figure 1. Participants’ hepatitis B vaccination status and place of origin.

Table 1. Hepatitis B vaccination status of participants

HBV vaccination status

describes HBV vaccination status. Only 26% (49/185) had three doses, whereas 45% (84/185) had none (p < .00001). In 2018, 31% (38/121) were fully vaccinated, and in 2019, 17% (11/64); suggesting that being fully vaccinated, occurs in a minority of people working with biological samples and is not peculiar to a single year. Of 185 participants, 11% (21/185) were incompletely vaccinated, 3% (6/185) were vaccinated with unknown doses, and 14% (25/185) reported unknown vaccination status.

Nobody age 50–64 years was fully vaccinated; whereas 25% (34/137) age 18–29 years and 35% (15/43) age 30–49 years were completely vaccinated. Sixty-nine percent of staff, 72% of Masters students, 42% of PhD students, and 30% of faculty were not vaccinated. Medical graduates had the highest rates of being fully vaccinated at 67%, but 11% of medical graduates were unvaccinated, and 22% were incompletely vaccinated. Compared to medical graduates, PhD scholars and postdoctoral fellows had 8.94 times (OR = 8.94, 95% CI: 3.43 to 23.29) increased risk for not being fully vaccinated, MSc students 6.67 times (OR = 6.67, 95% CI: 2.23 to 19.89), and project staff 14 times increased risk (OR = 14, 95% CI: 2.59 to 75.41). Students from the south had highest complete vaccination rates at 48% ().

Hepatitis B vaccine clinics

Twenty-five vaccine clinics were held between February 2019 and March 2020 (). One hundred thirty-six people were eligible from SMST, and 96 (71%) came forward for vaccination.

Table 2. Hepatitis B vaccine clinic participation

Table 3. Determinants of hepatitis B vaccine uptake (N = 64)

Table 4. Hepatitis B awareness among study participants (N = 85)

Seventy-seven people participated in the first vaccination cohort. Seventy (91%) completed their HBV vaccine series, six left the institute before dose three, and one was lost to follow-up after dose one. Two of the six who left the institute got dose three on their own. In the second cohort, thirty-three people participated and twenty-nine got dose two before March 2020. The majority were from the SMST: 91% (70/77) in the first round and 79% (26/33) in the second.

Determinants of HBV vaccine uptake

Sixty-four people participated in the survey on determinants of vaccine uptake (). In terms of access, availability of the vaccine in the Institute hospital on multiple days during evening hours was very important. For 78%, getting the vaccine for free was very important. The doctor’s recommendation was very important for 70% of participants, as was getting vaccinated with peers. Activation through phone and e-mail reminders and knowing the GOI recommendation were also very important.

The awareness of students working with OPIM about HBV infection, transmission, and vaccine effectiveness was explored specifically (). Sixty-seven percent of participants knew that HBV infection can cause hepatocellular carcinoma. Less than half agreed that HBV can be caught by touching a contaminated surface. Only 62% agreed that HBV can be transmitted by human cell culture and 77% agreed that HBV can be transmitted by biomedical waste. Most individuals believed the vaccine is safe, and 93% agreed that getting vaccinated could protect others.

shows a Social Ecological framework for uptake of hepatitis B at individual, departmental, institutional, and national levels.Citation19 In the absence of an institutional mandate, uptake by an individual was influenced most proximally by the department.

Discussion

Over a year, we documented the need for HBV vaccination in people working with biological materials in a major Indian institution, developed a HBV vaccination program, delivered HBV vaccines, and assessed determinants of vaccine uptake. Nearly 70% of the cohort was inadequately vaccinated. The majority got vaccinated when offered vaccine, and 90% completed all doses. This is the first Indian study looking at the need for HBV vaccination programs for occupational exposure in the academic research setting, outside of medical institutions.

In 2018, the GOI launched the National Viral Hepatitis Control Program, hoping to eradicate viral hepatitis by 2030. The cornerstone is expanding the target group for HBV vaccination to include adults at risk.Citation20 In China, where a strong HBV vaccination program for infants and children covered those under 20 years, they continued to see 60,000–80,000 annual cases of acute HBV, with the highest incidence in 20–29 years old. They found that a catch-up program for young adults could save close to a billion dollars.Citation21

The majority of participants in this study were young adults 18–29 years of age, all were exposed to OPIM, and compared to medical graduates, students and staff from other backgrounds had 6.7–14 times increased risk of being unvaccinated. Making HBV vaccines available to all at risk for occupational exposure to BBP is in line with Sustainable Development Goal 3.3, adopted by the GOI to eradicate viral hepatitis.Citation22

A study of auxiliary health workers in India that included laboratory technicians, hygienists, laundry workers, and housekeeping staff showed that while over 90% knew about HBV infection, less than 40% understood how to handle biomedical waste.Citation23 Awareness that HBV can be caught by touching contaminated surfaces, cell culture, and biomedical waste is essential, for students and staff to understand the relevance of HBV vaccination. We saw that a knowledge gap exists in terms of transmission via contaminated surfaces and understanding that human cell lines are OPIM. Integrating BBP exposure control education as part of institute biosafety programs that include HBV vaccination could increase awareness and vaccine uptake and prevent occupational infections. In the UK, after the implementation of BBP exposure control measures, there were no reported occupational HBV infections.Citation24

The US Blood Borne Pathogen Exposure Standard mandates HBV vaccination and teaching of engineering controls, work practice controls, and the development of individual safety plans in research universities as part of a biosafety framework.Citation25 The GOI 2016 Biomedical Waste Management and Handling Rules now require routine education and HBV vaccination for all working with these materials, thus providing an opportunity for Indian Institutions to augment BBP exposure control.Citation3

Vaccine uptake is influenced by 1) thoughts and feelings; 2) social norms; and 3) practical issues26. A person’s social network exerts tremendous influence on their behavior. We found that students, faculty, and staff of SMST were more likely to come forward to get vaccinated than members of other departments, although the vaccine was offered for all at risk, perhaps because a behavioral level contagion created in SMST promoted vaccination, which was not present in other departments. Activation, awareness, and acceptance are linked to social networks. Practical issues such as easy appointment times, on-site vaccination, reminders, recalls, and provider recommendations all issues related to affordability and access also affected uptake.

This study has limitations. We could not reach people who refused to get vaccinated to find out what led to vaccine hesitancy. This is a single-institution study with participants from only two departments. Consequently, the number of participants in some groups for stratified analysis is small, which may bias the results of the statistical analysis; however, we found that participants came from diverse geographic, educational, and literacy backgrounds, representative of a major academic institution. With the increase in biological research across Indian institutions, this study is representative of the need to develop BBP exposure control programs integrating HBV vaccination for those in the academic research environment. Additional studies are needed from other academic research institutions in India to help inform policies on BBP awareness, biosafety training, and the need for HBV vaccination for those at risk of occupational exposure.

Conclusion

HBV vaccination programs are needed in Indian academic institutions beyond medical schools as part of institutional biosafety programs. Uptake can be increased by building awareness and addressing the practical issues to activate people to get vaccinated by making vaccines accessible and affordable.

Acknowledgment

We want to acknowledge Dr. Samir Dasgupta, and Dr. Indranath Banerjee and the nurses, and staff at BC Roy Technology Hospital IIT Khragpur for their support with the vaccine clinics.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- 1910.1030 - Bloodborne pathogens. | occupational Safety and Health Administration [Internet]. [accessed 2021 Nov 2]. https://www.osha.gov/laws-regs/regulations/standardnumber/1910/1910.1030.

- European Union, Directive 2000/54/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 September 2000 on the protection of workers from risks related to exposure to biological agents at work (seventh individual directive within the meaning of Article 16(1) of Directive 89/391/EEC). Official J L. 2000 Oct;262. 0021 – 0045. EUR-Lex - 32000L0054. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2000/54/oj Accessed on 12 February 2021.

- Bio-medical Waste Management Rules. Government of India, Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change. Gazette of India, Extraordinary, Part II, Section 3, Sub-section (i). G.S.R. 343 (E) Mar 28, 2016; 2016. https://dhr.gov.in/sites/default/files/Biomedical_Waste_Management_Rules_2016.pdf.

- Mengistu DA, Tolera ST, Demmu YM. Worldwide prevalence of occupational exposure to needle stick injury among healthcare workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2021 Jan 29;2021:e9019534. doi:10.1155/2021/9019534.

- Sewell DL. Laboratory-associated infections and biosafety. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995 Jul;8(3):389–405. doi:10.1128/CMR.8.3.389.

- Applicability of 1910.1030 to establish human cell lines. | Occupational Safety and Health Administration [Internet]. [accessed 2021 Nov 2]. https://www.osha.gov/laws-regs/standardinterpretations/1994-06-21.

- Korenblit J. Biotechnology innovations in developing nations. Biotechnol Healthc. 2006 Feb;3(1):55–58.

- National Biotechnology Development Strategy 2015-2020 Promoting Bioscience Research Education and Entrepreneurship [Internet]. Department of Biotechnology, Ministry of Science and Technology, Government of India. https://dbtindia.gov.in/sites/default/files/DBT_Book-_29-december_2015.pdf. Accessed on 5 February 2021.

- Comprehensive Multi-Year Plan (cMYP) 2018–22, Universal Immunization Programme [Internet]. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2018. https://nhm.gov.in/New_Updates_2018/NHM_Components/Immunization/Guildelines_for_immunization/cMYP_201822_final_pdf#:~:text=New%20vaccines%20like%20Measles%20%26%20Rubella,were%20introduced%20in%20the%20country. Accessed on 4 November 2021.

- Khan J, Shil A, Mohanty SK. Hepatitis B vaccination coverage across India: exploring the spatial heterogeneity and contextual determinants. BMC Public Health. 2019 Sep 12;19(1):1263. doi:10.1186/s12889-019-7534-2.

- Geneva: World Health Organization. Global hepatitis report 2017 [Internet]; 2017. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/255016/9789241565455-eng.pdf;jsessionid=DE45341EB5F7E945CDB61F6A695C303F?sequence=1. Accessed on 14 February 2021.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. National plan combating viral hepatitis in India [Internet]; 2019. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/primary-health-care-conference/national-action-plan-lowress-reference-file.pdf?sfvrsn=6a00ecbf_2&download=true. Accessed on 15 February 2021.

- About IIT KGP [Internet]. Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur. [accessed 2021 Nov 2]. http://www.iitkgp.ac.in/about-iitkgp;jsessionid=7A2798FB3C0B12F33467679F56D64F7D.

- Biohazards associated with human tumor cell [Internet]. ATCC; 2012. https://www.atcc.org/support/faqs/81058/Biohazards%20associated%20with%20human%20tumor%20cells-173.aspx. Accessed on 10 May 2021.

- Thomson A, Robinson K, Vallée-Tourangeau G. The 5As: a practical taxonomy for the determinants of vaccine uptake. Vaccine. 2016 Feb 17;34(8):1018–24. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.11.065.

- Dubé È, Ward JK, Verger P, MacDonald NE. Vaccine hesitancy, acceptance, and anti-vaccination: trends and future prospects for public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2021;42(1):175–91. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-090419-102240.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A comprehensive immunization strategy to eliminate transmission of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Part II: immunization of adults [Internet]. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report; 2006. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/rr/rr5516.pdf. Accessed on 29 October 2021.

- India- State Boundaries [Internet]. States - community created maps of India. The Social-Ecological Model: A Framework for Prevention [Internet]. Violence Prevention, Injury Center, CDC; 2021 [accessed 2021 Nov 2]. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/about/social-ecologicalmodel.html.

- National viral hepatitis control program operational guidelines [Internet]. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2018. https://www.inasl.org.in/national-viral-hepatitis-control-program.pdf. Accessed on 4 May 2021.

- Zheng H, Wang F, Zhang G, Cui F, Wu Z, Miao N, Sun Z, Liang X, Li L. An economic analysis of adult hepatitis B vaccination in China. Vaccine. 2015;33(48):6831–39. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.09.011.

- Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. [Internet]. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs; 2015. https://sdgs.un.org/sites/default/files/publications/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf. Accessed on 9 May 2021

- Patil S, Rao RS, Agarwal A. Awareness and risk perception of hepatitis B infection among auxiliary healthcare workers. J Int Soc Prev Comm Dent. 2013;3(2):67–71. doi:10.4103/2231-0762.122434.

- Peng H, Bilal M, Iqbal HMN. Improved biosafety and biosecurity measures and/or strategies to tackle laboratory-acquired infections and related risks. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018 Nov 29;15(12):E2697. doi:10.3390/ijerph15122697.

- Bloodborne Pathogens Institutional Exposure Control Plan – Stanford Environmental Health & Safety [Internet]. Stanford Environmental Health & Safety; 2021 [accessed 2021 Nov 2]. https://ehs.stanford.edu/manual/bloodborne-pathogens-institutional-exposure-control-plan.

- Brewer NT, Chapman GB, Rothman AJ, Leask J, Kempe A. Increasing vaccination: putting psychological science into action. Psychol Sci Public Int. 2017 Dec;18(3):149–207. doi:10.1177/1529100618760521.