ABSTRACT

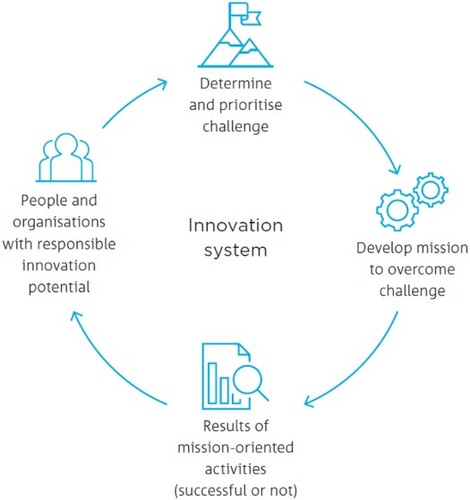

This perspective paper integrates theories of responsible innovation (RI) with the nascent development of the concept of mission-oriented innovation to address wicked socio-institutional challenges. Theoretically, steering a Mission-oriented Innovation System (MIS) and associated ‘mission arena' toward activities that create virtuous cycles of RI practice will lead to cumulative impacts on the evolution of innovation system cultures. We explore this claim using nascent future-oriented ‘missions' developing within the competitive industry setting of Australian agri-food research and development ventures and aligned training exercises (short courses) in RI practice. This example highlights attempts to stimulate the practice of RI from the bottom up through the Australian (national) innovation system, as agri-food ‘missions’ come to be. Such reporting provides a conceptual grounding to foster a cycle (see graphical abstract) of relevance for comparison to other ex-ante MIS as mission-orientation is popularized as a potential solution to intractable and urgent problems throughout the developed world.

A mission-oriented innovation cycle where clockwise from left:

1) people and organizations with ‘responsible innovation’ potential contribute as actors to an innovation system (technological, sectoral, regional, national or mission-oriented) that works to…

2) determine and prioritize a ‘challenge’ (‘grand societal’ or more mundane) then.

3) develops a ‘mission/s’ to overcome the ‘challenge’ leading to…

4) results of mission-oriented activities (that are either successful or not given the mission aims) over a given timeframe, circling back to…

5) the cumulative learning and development of language, discourse and practice (or not) of people, organizations, and innovation systems because of the mission-oriented innovation investment.

Introduction

There is need for innovation processes and resulting technologies to deliver positive impacts and address complex socio-environmental challenges (Veldhuizen Citation2021). This has led to the emergence of two distinct academic discourses, namely, Responsible Innovation (RI) and mission-oriented innovation.

The primary theoretical contribution of this perspective is to bridge these two strands of innovation studies, to highlight the potential of considering them as part of a single intellectual project as opposed to dispersed components of noisy innovation agendas.

Recently, there has been exploration of mission-oriented innovation policy as a mechanism to reorient innovation systems towards new goals (Reale Citation2021). Mission-oriented approaches to innovation (see Section 2 for more detail) have placed great emphasis on institutional designs to redirect innovation investments and actions but have yet to settle on a rigorously assessed and agreed form of practice – it is still early days (Janssen, Bergek, and Wesseling Citation2022). More long standing is the idea of responsible research and innovation (RRI), and subsequently RI, as an idea about proactively guiding the way research and innovation is undertaken cognizant of the social and environmental consequences of different deployment decisions (Owen, Macnaghton, and Stilgoe Citation2012). Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten (Citation2013, 1570) define RI to mean taking care of the future through collective stewardship of science and innovation in the present. The concept of RI (see Section 2 for more detail) has placed emphasis on the practices needed to shepherd innovation processes towards socially desirable outcomes (Christensen et al. Citation2020).

The purpose of this paper is to explore how the ideas of RI and mission-oriented innovation could work together. To both resolve some of the implementation challenges faced by mission-orientation, and at the same time help to elevate RI as a ‘portfolio of practice’ as part of collaborative innovation processes in competitive industrial settings. To explore this complex purpose, the paper reflects on learnings from developing and deploying short courses on responsible innovation and situating these experiences in the context of nascent agri-food mission arena development in Australia. We follow Taebi et al. (Citation2014) to note implications of this theoretical proposition for practice within the context of mission development in the highly competitive industrial setting of agri-food research and development in Australia, where the sector is proudly one of the least subsidized in the developed world (OECD Citation2022). The paper begins by introducing RI and mission-oriented innovation perspectives. It then recounts experiences from short course development and deployment before suggesting integration of these two streams of thought could help address some of the more intractable challenges of developing mission-oriented approaches that foster RI within contemporary, competitive, industrial settings.

RI as a capability to contribute to mission-oriented innovation?

Internationally, mission-oriented innovation approaches are proposed instruments to provide impetus for government to co-create and shape markets in line with societal missions (Mazzucato Citation2018). Mission-oriented innovation has been argued to be generalizable across entire innovation systems, as opposed to more specific domain-based problems or policy developments (Hekkert et al. Citation2020; Mazzucato, Kattel, and Ryan-Collins Citation2020). Kattel and Mazzucato (Citation2018, 787–788) argue that:

New missions can galvanize production, distribution, and consumption patterns across various sectors. Addressing grand challenges – whether traveling to the moon, battling climate change, or tackling modern care problems – requires investments by both private and public actors. The role of the public sector here is not just about de-risking, and leveling the playing field, but tilting the playing field in the direction of the desired goals – creating and shaping markets which increase the expectations of business around future growth opportunities, thus driving private investment.

Hekkert et al. (Citation2020, 77) define a Mission-oriented Innovation System (MIS) as:

The network of agents and set of institutions that contribute to the development and diffusion of innovative solutions with the aim to define, pursue and complete a societal mission.

Wesseling and Meijerhof (Citation2021) go further to describe a MIS as:

A temporary, semi-coherent configuration of different innovation system structures that affect the development and diffusion of solutions to a mission that is defined and governed by a ‘mission arena’ of different stakeholders.

In this perspective, we link the MIS concept to the practice of individuals and organizations utilizing an older sibling of innovation scholarship, namely RI (Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013). Why? Innovation requires that people articulate, operationalize, and actualize ideas (Dodgson and Gann Citation2018). Missions follow a similar trajectory of development, deployment and outcome, but as generally understood in recent literature, involve a ‘collective’ of individuals and organizations working toward the resolution of a mission or set of missions – in most cases within competitive industrial and international contexts (Wanzenböck et al. Citation2020; Klerkx and Begemann Citation2020; Hekkert et al. Citation2020).

There have been calls within RI literature for a higher level ‘knowledge arena’ conscious of institutional preconditions (Deblonde Citation2015). Missions and their ‘mission arenas’, have the potential to fill such gaps. On the other hand, there has been a recent call to formalize the evaluation of mission oriented innovation investment (Janssen, Bergek, and Wesseling Citation2022). Activities from a RI portfolio of practices can be deployed to fast-track such efforts to create learning cultures. Despite the potential synergy of these two perspectives, little work has been done to explicitly connect these discourses either conceptually or in terms of practical application (for exceptions see links in Schot and Steinmueller (Citation2018) or Robinson, Simone, and Mazzonetto (Citation2021)). By linking the scholarship of RI (in principle and practice) to the theory and execution of mission-oriented innovation agendas (in scope and trajectory of collective public-private partnerships), it could be possible to better orient toward a discourse targeted at achieving beneficial outcomes from broad stakeholder engagement.

RRI emerged explicitly out of European policy circles during the last decade in recognition of the need to consider responsibility across the entire innovation development cycle – from research (upstream) through engagement with stakeholders (mid-stream) and when developing and deploying innovation/s into a market (downstream) (Lacey, Coates, and Herington Citation2020; Owen, Macnaghton, and Stilgoe Citation2012). Such efforts to foster RI also represent more ‘inclusive’ innovation (Swaans et al. Citation2014). The term RI is used to more broadly encompass the interactions across an entire innovation value chain, and in order to recognize innovation itself – if defined as ideas, successfully applied – can arise from any component of an innovation system rather than just the upstream (research) sphere, including emerging and being driven via governments and civil society (Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013). The word ‘responsible’ implies a process that is active rather than passive. In some ways ‘responsible’ and ‘innovation’ exist in tension, with disruptive entrepreneurial start-up mantras of ‘move fast and break things’ running counter to consideration, responsibility, and accountability for actions (specifically those actions that ‘break things’) (Brookes Citation2021).

Randles and Laasch (Citation2016) introduced the Normative Business Model (NBM) which also helps to frame the logic of our Mission-Oriented Innovation Cycle (graphical abstract). On examining notions of normativity and institutional entrepreneurship within the NBM there is alignment with the ‘people and organizations’ component of the Mission-Oriented Innovation Cycle. Similarly, the (de)institutionalization notion of the NBM will ‘determine and prioritize the challenge/s’ being faced in a Mission-Oriented Innovation Cycle. Finally, the economic and financial models employed within the NBM are used to develop ‘missions’ and their operational scope, and subsequently the results (i.e. whether the mission is viewed as a success or a failure or somewhere in between) in relation to the initial projections and assumptions of such models. When viewed through a NBM lens, the actors (leading and supporting) develop the form of challenge worth overcoming, the organizations and institutional arrangements they emerge from determine the legitimacy of the challenge framing, and the interaction between these actors and institutions and the evaluative metrics developed for subsequent mission activities determine the success or otherwise of a mission. We propose that combined consideration of MIS (as institutional design) and RI (as individual and collective practice) would help to address some of the manifold concerns surrounding transparency, interaction, responsiveness and co-responsibility that hinder the employment of RI in competitive industrial environments (for more detail see Blok, Hoffmans, and Wubben (Citation2015)). Similarly, re-imagining economic and financial models and including social and environmental considerations in the evaluation of mission-oriented innovation investments would be supported by consideration of RI processes – for example the AIRR dimensions that follow.

On developing language and discourse to practice ‘responsible’ AgTech innovation

We introduce RI ‘practice’ as a mechanism to develop appropriate missions; achieve socio-environmental mission goals; and exploit unintended consequences of innovation processes that could build pathways to overcome grand societal challenges. Here, a case study concerning the transition toward digital agriculture via responsible technological capability in Australia highlights one example where these high-level framings of emerging innovation policy discussed in the literature (Schot and Steinmueller Citation2018) are beginning to be applied in practice. As such, the potential role of RI as practice – individual and organizational – can be probed to build RI capacity. The practice of RI is often distilled into four AIRR dimensions regarding the process of innovation:

into the future (Anticipation);

when choosing who to include/exclude (Inclusion);

in considering individual and group backgrounds, values, and interaction (Reflexivity); and,

proactively responding to issues raised as a result of interventions involving the previously mentioned dimensions (Responsiveness) (Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013).

Specific methods to consider each dimension when designing innovation processes can be found in existing literature (Fleming et al. Citation2021; Long et al. Citation2020; Eastwood et al. Citation2019; Bronson Citation2019; van der Burg, Bogaardt, and Wolfert Citation2019; Ditzler et al. Citation2018; Berthet, Hickey, and Klerkx Citation2018). RI, as a concept, builds on a plethora of ambitious projects to apply theory that results in ethically governed processes of innovation (ELSI, EGS, CSG, etc) (van der Burg, Bogaardt, and Wolfert Citation2019). There is a noticeable gap in RI literature regarding the operationalization of RI and how to most appropriately embed RI into innovation processes (Christensen et al. Citation2020).

Five of the authors of this paper (SF, JL, EJ, CS, JA) developed a short course entitled ‘Building Capacity for Responsible Innovation: Agri-Technology’. The purpose of the course was to embed in participants’ practice the recognition of opportunities and challenges that a responsible approach to innovation might engender. We moved, as pilot course participants, beyond the tools and theory of RI to think about the role of the concept in our everyday practice. In Australia, our attempts to discuss relevant ideals for RI practice within the nascent and competitive agricultural technology (AgTechFootnote1) sector were met with barriers that seemed rather obvious and have been widely reported in other contexts.Footnote2 Primarily, there is a lack of awareness of how a portfolio of RI practice is different to existing ‘best practice’ (Fielke et al. Citation2022). There is hesitancy to sacrifice existing political and economic capital by investing in the knowledge economy and novel ideas until proven worthwhile (Leeuwis and Aarts Citation2021). It is rare to garner buy-in from both formal and informal institutional ‘entrepreneurs’ to encourage change (Kaltenbrunner Citation2020). For specific discussion on barriers to the development and deployment of digital technologies in Australian agriculture see Higgins and Bryant (Citation2020). Questions arose from colleagues and course participants for our research practice as to whether already (or informally) doing RI-like activities ‘count’, why we need a new overarching concept, what level of authenticity or understanding of the concepts were required, etc (Lacey, Coates, and Herington Citation2020). At the same time, the unquestionable value propositions of how technologically driven change will actually benefit society resulted in confusion concerning the added value of RI from the perspective of potential beneficiaries for whom value propositions may not be very obviously aligned to technological development (Fielke et al. Citation2021; Jakku et al. Citation2019; Stitzlein et al. Citation2021).

Realizing the need for appropriate ‘practice’ of mission-oriented innovation

Increased global inequality, systemic planetary risks like climate change, and massive shifts in communications, commerce and production via digital disruption have challenged conventional neoclassical economic theory and the role of government in innovation (Schot and Steinmueller Citation2018). The nature and scale of the various challenges mean that innovation policy, and the innovation systems it guides, must also evolve over cycles of innovation investment (Hekkert et al. Citation2020; Mazzucato, Kattel, and Ryan-Collins Citation2020). Various national and global sustainability challenges involve re-orientation of innovation systems into the future (Rosenbloom et al. Citation2020). To develop, work on, and successfully achieve missions that may overcome such challenges, we need to consider culture, practice and partnership across innovation system actors at individual and organizational levels (e.g. see Blok, Sjauw-Koen-Fab, and Omtac (Citation2013) or Scholten and Blok (Citation2015)). Similarly, initial confrontational interactions can led to multually beneficial partnerships across diverse organizations, as Bos, Blok, and Tulder (Citation2013) report in relation to an animal welfare Non-Governmental Organization and private agricultural companies co-creating a product ‘brand’ in the Netherlands.

Informal discussions with RI short course participants and international MIS scholars suggested that the emergence of ‘mission arenas’ come from pre-existing relations and networks. Missions may be a recently popularized approach to overcoming challenges, but the innovation systems they draw from are not new. As a ‘temporary, semi-coherent configuration’ a mission is an opportunity to develop capacities in desired directions that accumulate via subsequent generations of missions (or whatever terms were used before or will come after for such efforts) (Wesseling and Meijerhof Citation2021). For individuals and involved organizations missions provide an opportunity to practice and refine their versions of innovation to be more appropriate and aligned with individual, organizational, mission determined, and societal values.

More collaborative innovation cultures and practices would enable parties to balance working together across institutions more productively as opposed to traditionally segregated public and private organizations and individuals (for examples of such efforts in the context of circularity of RI see Scholten and Blok (Citation2015), or Nathan (Citation2015)). Such cultural evolution, however, requires cycles on innovation investment to foster. In the absence of mission-oriented innovation policies in the Australian (national) innovation system, organizations are beginning to develop missions of their own. Such bottom-up, or informal mission development involves recognizing innovation as a collective social process with different metrics of success for different individuals and organizations (Leeuwis and Aarts Citation2021). Inevitably, during such social organization processes, accountability for governance and leadership, resource allocation, and activity prioritization needs to be ‘held’ somewhere (Klerkx and Begemann Citation2020). However, the dominant institutional structures within research and development (R&D) organizations may be a barrier to mission outcomes if these agendas are viewed as a threat to incumbent regime trajectories (Turner et al. Citation2020). Incumbent pioneers may then need to use their powers to explore opportunities to promote change, cognizant of their individual biases, and in making choices about tradeoffs concerning a diversity of potential outcomes (van Mossel, van Rijnsoever, and Hekkert Citation2018). New language and embodied practice, such as that developed through targeted training (short courses), will be required to help such pioneers deliver on their individual and across organizational endeavors (Veldhuizen Citation2021). In the next section a national and sector specific exploration of such mission-oriented innovation development identifies the potential for RI and MIS integration.

Emerging ‘mission arenas’ in the Australian agri-food sector

Are current research, development and innovation organizations best placed to adequately encourage the hard work required to bridge across organizations that have learned to be primarily in competition into a more ‘team Australia’ approach to R&D via RI? Here, some of the emerging mission (and mission like) activities in the Australian agri-food sector are used to highlight the current state of development, ambitions pursued, and likely structural and cultural barriers to mission success. Individuals and organizations that act as components of MIS will need to work in concert with multiple parties to define challenges, develop, deploy, and achieve (or not) a collective mission/s. Ludwig et al. (Citation2022) highlight the risk of allowing ‘dominant stakeholders’ to lay the foundation of interpretation and solution generation ideation associated with grand global challenges. Specifically, that institutions holding power – as incumbents – interpret challenges and then suggest ‘solutions’ to such challenges that align with the existing zeitgeist they themselves are locked into (Ludwig et al. Citation2022). We recognize, as Ludwig et al. (Citation2022) argue, in many cases ‘other’ actors will have disparate and potentially competing or disruptive aims, whether implicitly or explicitly, that may result in negotiation strategies when (re)framing a challenge, and their approach to operationalizing a mission/s. We also agree that such challenge negotiation is open to ‘token’ inclusion whilst beholden to the same incumbent and ‘dominant stakeholders’ (Ludwig et al. Citation2022). Importantly, however, the immaturity and diversity of the mission-oriented approach to innovation in Australia exposes a lack of empirical examination in this research space now. This paper begins to address this immaturity by framing the need for mission-oriented and responsible innovation conceptualization – in both design and delivery or policy and practice – to determine the success of a ‘challenge’ and subsequent ‘mission’ life cycle, for whom, over a given time frame. Work is underway to report on mission’s ex ante, as they begin to be negotiated (for a similar approach to post commencement mission analysis see Janssen (Citation2020)).

Caveats above noted, activities that may contribute to Australian mission-oriented agricultural innovation systems already exist. For example: the National Agricultural Innovation Agenda;Footnote3 the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization’s (CSIRO) agri-food related challenges and missions;Footnote4 the Food Agility Cooperative Research Centre’s (CRC) ‘Mission Food for Life’;Footnote5 more general CRC investment; and an ongoing shift of the University sector toward impact and/or commercially focused R&D. Similarly, industry bodies’ aspirational goals such as: The National Farmers’ Federation 2030 roadmap to exceed $100 billion in farmgate output by 2030;Footnote6 or Meat and Livestock Australia’s mission to be carbon neutral by 2030Footnote7 also highlight ambitious and multi-faceted aims. These organizations and their partner’s ambitions will benefit from orientation and oversight of critical R&D resources to align different actors with common national and international sustainability transition and transformative agri-food innovation agendas (Veldhuizen Citation2021; Herrero et al. Citation2020). We suggest that the agendas of individuals and organizations in pursuing mission-oriented innovation can be assisted via consideration of social responsibility and RI practice – as Dabars and Dwyer (Citation2022) describe in the context of the institutionalization of RI at Arizona State University. Virtuous cycles of collegial, multi-stakeholder fora, engagement, and socio-environmental consideration prompted as a component of RI practice (Gurzawska, Mäkinen, and Brey Citation2017) align with the broader and more complex nature of challenge and mission development and resolution (Sachs et al. Citation2019). As such, there is potential to create what we refer to as a more or less ‘Responsible MIS’ via individual and collective reflexivity on how and why such mission arenas develop, are conducted, and disperse (Fleming et al. Citation2021; Berthet, Hickey, and Klerkx Citation2018).

Responsible mission-oriented innovation systems

What has applying theory via research and training practice taught us about the concepts of RI and mission-oriented innovation in the context of the competitive agri-food industry of Australia? Three important things: existing interactions within innovation systems matter; temporality matters; and cumulative learning can be directed over cycles of innovation investment. But first, caution from the work of Peterson (Citation2013, 15) concerning multi-stakeholder engagement around innovation for sustainability outcomes in that:

If only system outcomes are considered and managed, potential innovation to change the system may never be implemented because of stakeholder vetoes. Government and societal organizations can veto supply chain/network actions. Their differing values and commitment levels create the potential to act. On the other hand, if only stakeholder process matters, potential innovation will never be implemented because of endless debate.

First, each challenge being addressed, along with the mission/s that contribute to overcoming them, will depend on the practice/s of actors through interactions within their networks. By linking the practice of the individuals and organizations they identify with a more holistic, considerate, consistent in message, authentic and mature innovation system (or perhaps connectivity might justify recent use of the term ‘ecosystem’) will be developed (Granstrand and Holgersson Citation2020; Walrave et al. Citation2017).

The practice of RI, or at least its explicit consideration, provides impetus to debate individual and organizational fears of change, power struggles and lock ins, and build a different form of capacity within national, regional, sectoral, technological, and now mission-oriented innovation systems. Over a decade of research on RI (Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013; Owen, Macnaghton, and Stilgoe Citation2012) provides an opportunity to blend different micro-level activities of individuals and organizations within respective innovation systems and steer challenge articulation and mission responses in more appropriate directions. While passing mention of RI within mission-oriented packages of work seeking system transformation has been made (Schot and Steinmueller Citation2018; Robinson, Simone, and Mazzonetto Citation2021), deeper exploration is required of how RI and mission-oriented innovation (as the more nascent yet significantly influential concept) can create novel synergies. The emergence of the concept of a MIS now allows for actors practicing within a mission arena (with respect to both governance of and in undertaking mission-oriented activities) to consider their positions relative to others throughout a mission lifecycle (Wesseling and Meijerhof Citation2021). This learning is a natural outcome when situating oneself and their disciplinary and worldview lens’ in a framework of RI to contribute to a ‘mission’ (organizational or grand or societal) agenda (Taebi et al. Citation2014).

Second, missions are temporary investments in the direction of innovation capacity. The graphical abstract shows how the individual and organizational actors that make up an innovation system contribute to this process. Even though a mission is by its definition temporary (Wesseling and Meijerhof Citation2021), the effect of the actions of individuals and organizations involved will contribute to national and international innovation systems in various ways in perpetuity. If made to explicitly link to RI practice at individual, organization and mission arena levels it would be possible to enact a Responsible MIS. Certain grand societal challenge-based mission concepts will likely predispose themselves to the creation of more Responsible MIS than others. However, such diversity of approaches to MIS investment portfolios will then be important for overall agri-food systemic change in an effort to increase resilience (Hansen, Ingram, and Midgley Citation2020).

In some cases, particularly in revenue-focused private organizations and adjacent technological innovation systems, the most responsible pathway may be to innovate quickly if the scale of change sought is incremental product alteration, likeminded coalition building, or rapid return on investment. Engineering the next (with better features or fixing existing bugs) version of software would be an example of such exploitation. When innovation processes have an explicit and cumulative aim to contribute to the transformation of societies, economies, and environments, an example being missions to address grand societal challenges, we argue an investment in RI practice is necessary as part of such ambitious change agendas. Why not? To pursue radically novel agendas, collective proponents will need to consider implications for the entirety of impacts they will (and may) have on the holistic systems they are part of adapting. These impacts are both positive and negative, for example deciding to cease the exploitation of certain innovation or industry activities and related need for skills and capabilities. Ongoing RI practice also builds a broader view of such decisions informed by, but also evolving with, developments in both technology and societies into which they are deployed (Novitzky et al. Citation2020).

Finally, learning contributing to micro-level individual, group and across organizational practice change over time will alter the composition of an innovation system. Building capabilities to address grand societal challenges will require building collective innovation capacity – of individuals and their organizations and which can be optimized via RI practice – to increase the likelihood and appropriateness of collective mission outputs (Oreszczyn, Lane, and Carr Citation2010; Berkes Citation2009; Wals Citation2008). Informed by participation in somewhat confronting exercises, such as philosophical discussions of values and motivations, we suggest individuals and organizations need to proactively examine the cumulative impacts of their practice and the mission/s they contribute to (or not). Whether implicitly or explicitly, investment in mission-oriented innovation delivery will create the innovation systems future generations inherit. Providing a space for such internal individual grounding will provide the collective actors in a mission arena a solid basis to do the hard work to situate their positionality as part of a group. In missions developed from the bottom up via influential organizations and partnerships, the explicit recognition and encouragement of RI practice is one way to bridge the gap between lofty ambitions and everyday practices that build the authenticity and legitimacy of a mission arena.

We do not underestimate the task in front of the diversity of international actors currently attempting to define and enact a more Responsible MIS – whether knowingly or unknowingly. Both the need for critical introspection and recognizing complexity formed part of our motivation to build the course participant experience, and our subsequent engagement and thinking about/with missions. Practitioners will be required to critically reflect on their own position, principles, and values within the context of a portfolio of activities. Understanding this complexity is part of the ‘ask’ of mission-oriented innovation and we agree with arguments it is the first step to navigating such internal, interpersonal and systemic tensions (Klerkx and Begemann Citation2020). We also support others in the argument that stronger quantitative and systematic analyses will be required to determine the success (or not) of RI (Ryan, Mejlgaard, and Degn Citation2021), mission-oriented (Janssen, Bergek, and Wesseling Citation2022) and challenge-led innovation (Välikangas Citation2022).

Reflecting on efforts to bridge practice and ambition as Australian mission arenas organize

At present, in the Australian agri-food sector at least, there is a lack of language and evidence to convincingly justify the underlying agenda of MIS experimentation as it is too premature. Quite often terms such as ‘building the plane while flying it’, ‘schizophrenic’, or ‘scaling up while scaling out’ are used when discussing the emergence of missions as the latest phase of large programs of multi-organizational R&D investment. As Välikangas (Citation2022) notes with regard to ‘grand challenges’ generally, there is ‘something for everyone’. It is no secret that coordination and collaborative zeal has not been encouraged to the extent that competitiveness has in Australian (agricultural or otherwise) innovation systems (Robertson et al. Citation2016).

Bridging concepts of RI (as practice) with a MIS (as a temporary institutional organization mechanism) provides a way of thinking about collective innovation as an alternative option to overcome short falls that exist in a previously disconnected, highly competitive and privatized sectoral approaches to innovation.

As a recalibration of nation-state and international relations occurs post 2020 it is possible to use training in a RI portfolio of practice as an individual and organizational asset that seeks to bolster the relational and process dependent components central to resilient agri-food systems. We reported on early efforts to do so here via the development of bespoke short courses on RI in agri-technology and a symposium to bring disparate actors across innovation systems together (see Note 2). Others have already clearly highlighted similar investments to understand resilience will be critical for shaping various levels of ‘system’ into the future, including: food systems (Hansen, Ingram, and Midgley Citation2020); farming systems (Darnhofer Citation2021); rural communities (Kaye-Blake et al. Citation2019; Fielke et al. Citation2018); the R&D sector (Knickel et al. Citation2018; Lubberink et al. Citation2019); and, entire agricultural systems (Snow et al. Citation2021).

We encourage the exploration and brokerage of innovation language that broadens our understanding of the potential of a MIS considering RI practice to develop alternative pathways leading to various plausible futures. Such broadening might involve the inclusion of unlikely or uncommon views in discussions, and efforts to think about the individual and organizational biases that are embedded in the day-to-day tasks weFootnote8 undertake. In many cases, these discussions may get uncomfortable and result in sitting with tension. We must learn to recognize but not retreat from uncomfortable situations such as these. The language of RI is a communication tool that should allow us to branch out from our comfortable circles and communities and form new, more diverse ones.

The subsequent cultures that develop through emergence of a Responsible MIS could begin to shift priorities and nudge us as both individuals and representatives of collectives beyond commercial start-up mantras (Thaler and Sunstein Citation2009). Such that innovation for innovation’s sake is no longer aspirational – rather we seek innovation that attempts to achieve positive socio-environmental change in various and diverse forms. Such forms include, but are not limited to, income generation, increased employment, societal wellbeing, and as a contribution to national GDP. This is important because even those organizations that were technology start-ups not too long ago, evolving into corporate technology sector behemoths, are now explicitly recognizing a need to develop training and team offerings based around RIFootnote9 and in the development of their techno-utopian visions of the future.Footnote10

Conclusion

Now, pandemics, natural disasters, and increasing climatic variability are being faced at the same time as aspirational goals for sustainable development – poverty reduction, natural resource management, decarbonization, ongoing economic growth and improvements in quality of life – are sought (Sachs et al. Citation2019). During such transitioning of social, environmental and economic outcomes there are windows of opportunity to re-orient innovation policy and practice to begin to shift the priorities of actors working in innovation systems to focus their collective energy in different ways (Boin, Hart, and McConnell Citation2009). It is feasible to add value by deploying the theory and practice of RI when considering the justification of activities within sectoral, regional, and technologically influenced MIS. Virtuous innovation processes will help articulate the need to hold onto certain strategic mission activity pathways both during and beyond mission life cycles (long term planning), report on progress (or lack thereof) in diverse ways and change direction if necessary. Building respect for the individual actors within a Responsible MIS, conscious of the value of diversity of personal and professional identities and interactions, will be critical to achieving the across organization ownership of many mission agendas. This goodwill then provides a platform for engagement beyond the mission life cycle, whether this happens in the nascent missions mentioned briefly in this paper or in future rounds of mission (or mission-like) investments that follow. It is important that innovation brokers and institutional entrepreneurs contributing to these missions respectfully encourage RI practice (whether recognized by their organizations as such or not) in order to build a capability that accumulates and can be deployed repeatedly (Turner et al. Citation2020). Considering the challenges twenty-first century societies face – including a variety of compounding environmental, economic, and social crises – it seems such a capability asset is a critically important one to prioritize because it boosts dialogue of resilience from the individual/organization level ‘down under’ all the way up to the top-sectors of our innovation systems (Janssen Citation2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge CSIRO, Australian National University, Athena Education, University of Tasmania and Utrecht University colleagues for ideas, input, and feedback on this paper. Thanks specifically to Joeri Wesseling (Utrecht University), Sanne Bours (Utrecht University) and Katharina von Stauffenberg (Leuphana University), Peat Leith, Tracy Henderson, and the anonymous peer reviewers for their comments to further improve this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Simon J. Fielke

Simon Fielke conducts applied human geographical research into the implications of the digitalization of agricultural innovation systems. The domain of agtech is helping build on conceptualizations of ‘Responsible Innovation’ and what they mean for the practice of research and development into the future. Simon’s work has always focused on the future of agricultural land use, particularly regarding the governance of agri-food systems, within Australasia and more broadly.

Justine Lacey

Justine Lacey leads CSIRO’s Responsible Innovation Future Science Platform; a research program examining the interface between science and technology innovation and the associated ethical, social and legal consequences of new and disruptive science and technologies. CSIRO’s Future Science Platforms aim to develop the early-stage science that underpins disruptive innovation and has the potential to reinvent and create new industries for Australia.

Emma Jakku

Emma Jakku applies her expertise in the sociology of science and technology to help improve understanding of technology development, implementation and adoption processes. Her current research examines the social and institutional context of digital transformation in Australian agriculture.

Janelle Allison

Janelle Allison has over 25 years’ experience in higher education and most recently was Pro Vice-Chancellor (Community, Partnerships and Regional Development) and Principal of University College at the University of Tasmania. Janelle has a background in Geography and Regional Planning. She has worked with regional communities and in regional development in Australia, (particularly Queensland) as well as overseas in Africa, Papua New Guinea, Cambodia and Indonesia. Janelle has taught in a range of settings including planning/design studios, rural community development, short courses and training for regional development in provincial governments in Indonesia.

Cara Stitzlein

Cara Stitzlein applies human-centred design methodologies for purposes of development, evaluation and performance benchmarking. Qualifications include formal training in human factors, applying User Experience (UX) research techniques within industry settings, and executing research programs in areas that include remote collaboration, critical care, first generation interfaces, and workforce productivity.

Katie Ricketts

Katie Ricketts is a development economist interested in food systems and agricultural value chains; in particular, how these networks influence human health, nutrition and poverty. Her work has analysed the welfare risks and opportunities for linking smallholder farmers to market opportunities and the evolution of food value chains on urban and rural food security. In the past, she’s collaborated with non-governmental agencies like Oxfam, UN-FAO and the World Bank and been on the research staff of the CGIAR, Cornell University and Colorado State University.

Andy Hall

Andy Hall is a science and technology policy analyst with a specialization in the study and design of agriculture innovation processes, policies and practices. Andy has done pioneering research on the nature and performance of agricultural innovation systems and more recently has explored the conditions and enablers of transformational innovation in agri-food systems. Andy has held positions at the National Agricultural Research Organization in Uganda, the Natural Resources Institute in the United Kingdom, the International Crops Research institute for the Semi-Arid Tropic (ICRISAT), India and the United Nations University Institute for Economics Research on Innovation and Technology (UNU-MERIT) in the Netherlands and India.

Alexander Cooke

Alex Cooke is an experienced manager and policy adviser in the areas of science, research, innovation and the digital economy. Alex is currently General Manager of the Missions Program within CSIRO.

Notes

1 Since the development of this paper the terms ‘FoodTech’ and ‘ClimateTech’ have also been popularised in global and national discussions.

2 For more information see https://research.csiro.au/ri/short-course-on-responsible-innovation-in-agri-technology/ or https://research.csiro.au/digiscape/responsible-agtech-symposium/

8 As researchers we suggest there is a desperate need to include ourselves in such work.

9 Examples include Facebook’s RI team - https://tech.fb.com/responsible-innovation/ or Google’s work on Artificial Intelligence and RI - https://blog.google/technology/ai/update-work-ai-responsible-innovation/

10 See Facebook’s recent rebrand to ‘Meta’ inclusive of recognised need to build the ‘Metaverse’ responsibly – https://about.facebook.com/meta?utm_source=Google&utm_medium=paid-search&utm_campaign=metaverse&utm_content=post-launch

References

- Berkes, F. 2009. “Evolution of Co-Management: Role of Knowledge Generation, Bridging Organizations and Social Learning.” Journal of Environmental Management 90 (5): 1692–1702. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2008.12.001.

- Berthet, Elsa T., Gordon M. Hickey, and Laurens Klerkx. 2018. “Opening Design and Innovation Processes in Agriculture: Insights From Design and Management Sciences and Future Directions.” Agricultural Systems 165: 111–115. doi:10.1016/j.agsy.2018.06.004.

- Blok, V., L. Hoffmans, and E. F. M. Wubben. 2015. “Stakeholder Engagement for Responsible Innovation in the Private Sector: Critical Issues and Management Practices.” Journal on Chain and Network Science 15 (2): 147–164. doi:10.3920/JCNS2015.x003.

- Blok, Vincent, August Sjauw-Koen-Fab, and Onno Omtac. 2013. “Effective Stakeholder Involvement at the Base of the Pyramid: The Case of Rabobank.” International Food and Agribusiness Management Review 13 (A): 39–44.

- Boin, A., P. Hart, and A. McConnell. 2009. “Crisis Exploitation: Political and Policy Impacts of Framing Contests.” Journal of European Public Policy 16 (1): 81–106. doi:10.1080/13501760802453221.

- Bos, Jacqueline M., Vincent Blok, and Rob van Tulder. 2013. “From Confrontation to Partnerships: The Role of a Dutch Non-Governmental Organization in Co-Creating a Market to Address the Issue of Animal Welfare.” International Food and Agribusiness Management Review 16 (A): 69–75.

- Bronson, Kelly. 2019. “Looking Through a Responsible Innovation Lens at Uneven Engagements with Digital Farming.” NJAS – Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences 90–91: 100294. doi:10.1016/j.njas.2019.03.001.

- Brookes, J. 2021. “Cathy Foley, Uni VCs Warn on Translation Risks.” InnovationAus. Accessed 27 August. https://www.innovationaus.com/cathy-foley-uni-vcs-warn-on-translation-risks/.

- Christensen, Malene Vinther, Mika Nieminen, Marlene Altenhofer, Elise Tancoigne, Niels Mejlgaard, Erich Griessler, and Adolf Filacek. 2020. “What’s in a Name? Perceptions and Promotion of Responsible Research and Innovation Practices Across Europe.” Science and Public Policy 47 (3): 360–370. doi:10.1093/scipol/scaa018.

- Dabars, William B., and Kevin T. Dwyer. 2022. “Toward Institutionalization of Responsible Innovation in the Contemporary Research University: Insights From Case Studies of Arizona State University.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 9 (1): 114–123. doi:10.1080/23299460.2022.2042983.

- Darnhofer, Ika. 2021. “Resilience or How Do We Enable Agricultural Systems to Ride the Waves of Unexpected Change?” Agricultural Systems 187: 102997. doi:10.1016/j.agsy.2020.102997.

- Deblonde, Marian. 2015. “Responsible Research and Innovation: Building Knowledge Arenas for Glocal Sustainability Research.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 2 (1): 20–38. doi:10.1080/23299460.2014.1001235.

- Ditzler, Lenora, Laurens Klerkx, Jacqueline Chan-Dentoni, Helena Posthumus, Timothy J. Krupnik, Santiago López Ridaura, Jens A. Andersson, Frédéric Baudron, and Jeroen C. J. Groot. 2018. “Affordances of Agricultural Systems Analysis Tools: A Review and Framework to Enhance Tool Design and Implementation.” Agricultural Systems 164: 20–30. doi:10.1016/j.agsy.2018.03.006.

- Dodgson, Mark, and David Gann. 2018. Innovation: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Eastwood, C., L. Klerkx, M. Ayre, and B. Dela Rue. 2019. “Managing Socio-Ethical Challenges in the Development of Smart Farming: From a Fragmented to a Comprehensive Approach for Responsible Research and Innovation.” Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics 32: 741–768. doi:10.1007/s10806-017-9704-5.

- Fielke, Simon, Kelly Bronson, Michael Carolan, Callum Eastwood, Vaughan Higgins, Emma Jakku, Laurens Klerkx, et al. 2022. “A Call to Expand Disciplinary Boundaries so That Social Scientific Imagination and Practice are Central to Quests for ‘Responsible’ Digital Agri-Food Innovation.” Sociologia Ruralis 62 (2): 151–161. doi:10.1111/soru.12376.

- Fielke, Simon J., William Kaye-Blake, Alec Mackay, Willie Smith, John Rendel, and Estelle Dominati. 2018. “Learning from Resilience Research: Findings From Four Projects in New Zealand.” Land Use Policy 70: 322–333. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.10.041.

- Fielke, Simon J., Bruce M. Taylor, Emma Jakku, Martijn Mooij, Cara Stitzlein, Aysha Fleming, Peter J. Thorburn, Anthony J. Webster, Aaron Davis, and Maria P. Vilas. 2021. “Grasping at Digitalisation: Turning Imagination Into Fact in the Sugarcane Farming Community.” Sustainability Science 16 (2): 677–690. doi:10.1007/s11625-020-00885-9.

- Fleming, Aysha, Emma Jakku, Simon Fielke, Bruce M. Taylor, Justine Lacey, Andrew Terhorst, and Cara Stitzlein. 2021. “Foresighting Australian Digital Agricultural Futures: Applying Responsible Innovation Thinking to Anticipate Research and Development Impact Under Different Scenarios.” Agricultural Systems 190: 103120. doi:10.1016/j.agsy.2021.103120.

- Granstrand, Ove, and Marcus Holgersson. 2020. “Innovation Ecosystems: A Conceptual Review and a New Definition.” Technovation 90–91: 102098. doi:10.1016/j.technovation.2019.102098.

- Gurzawska, Agata, Markus Mäkinen, and Philip Brey. 2017. “Implementation of Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI) Practices in Industry: Providing the Right Incentives.” Sustainability 9 (10): 1759.

- Hansen, Angela R., John S. I. Ingram, and Gerald Midgley. 2020. “Negotiating Food Systems Resilience.” Nature Food 1 (9): 519. doi:10.1038/s43016-020-00147-y.

- Hekkert, Marko P., Matthijs J. Janssen, Joeri H. Wesseling, and Simona O. Negro. 2020. “Mission-Oriented Innovation Systems.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 34: 76–79. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2019.11.011.

- Herrero, Mario, Philip K. Thornton, Daniel Mason-D’Croz Jeda Palmer, Tim G. Benton, Benjamin L. Bodirsky, Jessica R. Bogard, et al. 2020. “Innovation Can Accelerate the Transition Towards a Sustainable Food System.” Nature Food 1 (5): 266–272. doi:10.1038/s43016-020-0074-1.

- Higgins, Vaughan, and Melanie Bryant. 2020. “Framing Agri-Digital Governance: Industry Stakeholders, Technological Frames and Smart Farming Implementation.” Sociologia Ruralis 60 (2): 438–457. doi:10.1111/soru.12297.

- Jakku, Emma, Bruce Taylor, Aysha Fleming, Claire Mason, Simon Fielke, Chris Sounness, and Peter Thorburn. 2019. “If They Don’t Tell Us What They do with it, why Would we Trust Them? Trust, Transparency and Benefit-Sharing in Smart Farming.” NJAS – Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences 90-91: 100285. doi:10.1016/j.njas.2018.11.002.

- Janssen, Matthijs. 2020. “Post-Commencement Analysis of the Dutch ‘Mission-Oriented Topsector and Innovation Policy’ Strategy.” In Utrecht: Mission-Oriented Innovation Policy Observatory (MIPO), Copernicus Institute of Sustainable Development, 1–55. Utrecht: Utrecht University.

- Janssen, Matthijs J., Anna Bergek, and Joeri H. Wesseling. 2022. “Evaluating Systemic Innovation and Transition Programmes: Towards a Culture of Learning.” PLoS Sustainability and Transformation 1 (3): e0000008. doi:10.1371/journal.pstr.0000008.

- Kaltenbrunner, Wolfgang. 2020. “Managing Budgetary Uncertainty, Interpreting Policy. How Researchers Integrate “Grand Challenges” Funding Programs Into Their Research Agendas.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 7 (3): 320–341. doi:10.1080/23299460.2020.1744401.

- Kattel, Rainer, and Mariana Mazzucato. 2018. “Mission-Oriented Innovation Policy and Dynamic Capabilities in the Public Sector.” Industrial and Corporate Change 27 (5): 787–801. doi:10.1093/icc/dty032.

- Kaye-Blake, William, Kelly Stirrat, Matthew Smith, and Simon Fielke. 2019. “Testing Indicators of Resilience for Rural Communities.” Rural Society 28 (2): 161–179. doi:10.1080/10371656.2019.1658285.

- Klerkx, Laurens, and Stephanie Begemann. 2020. “Supporting Food Systems Transformation: The What, Why, Who, Where and How of Mission-Oriented Agricultural Innovation Systems.” Agricultural Systems 184: 102901. doi:10.1016/j.agsy.2020.102901.

- Knickel, K., M. Redman, I. Darnhofer, A. Ashkenazy, T. Calvão Chebach, S. Šūmane, T. Tisenkopfs, et al. 2018. “Between Aspirations and Reality: Making Farming, Food Systems and Rural Areas More Resilient, Sustainable and Equitable.” Journal of Rural Studies 59: 197–210. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.04.012.

- Lacey, Justine, Rebecca Coates, and Matthew Herington. 2020. “Open Science for Responsible Innovation in Australia: Understanding the Expectations and Priorities of Scientists and Researchers.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 7 (3): 427–449. doi:10.1080/23299460.2020.1800969.

- Leeuwis, C., and N. Aarts. 2021. “Rethinking Adoption and Diffusion as a Collective Social Process: Towards an Interactional Perspective.” In The Innovation Revolution in Agriculture, edited by H. Campos, 95–116. Cham: Springer.

- Long, Thomas B., Vincent Blok, Steven Dorrestijn, and Phil Macnaghten. 2020. “The Design and Testing of a Tool for Developing Responsible Innovation in Start-up Enterprises.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 7 (1): 45–75. doi:10.1080/23299460.2019.1608785.

- Lubberink, Rob, Vincent Blok, Johan van Ophem, and Onno Omta. 2019. “Responsible Innovation by Social Entrepreneurs: An Exploratory Study of Values Integration in Innovations.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 6 (2): 179–210. doi:10.1080/23299460.2019.1572374.

- Ludwig, David, Vincent Blok, Marie Garnier, Phil Macnaghten, and Auke Pols. 2022. “What’s Wrong with Global Challenges?” Journal of Responsible Innovation 9 (1): 6–27. doi:10.1080/23299460.2021.2000130.

- Mazzucato, Mariana. 2018. “Mission-Oriented Innovation Policies: Challenges and Opportunities.” Industrial and Corporate Change 27 (5): 803–815.

- Mazzucato, Mariana, Rainer Kattel, and Josh Ryan-Collins. 2020. “Challenge-Driven Innovation Policy: Towards a New Policy Toolkit.” Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade 20 (2): 421–437.

- Nathan, G. 2015. “Innovation Process and Ethics in Technology: An Approach to Ethical (Responsible) Innovation Governance.” Journal on Chain and Network Science 15 (2): 119–134. doi:10.3920/JCNS2014.x018.

- Novitzky, Peter, Michael J. Bernstein, Vincent Blok, Robert Braun, Tung Tung Chan, Wout Lamers, Anne Loeber, Ingeborg Meijer, Ralf Lindner, and Erich Griessler. 2020. “Improve Alignment of Research Policy and Societal Values.” Science 369 (6499): 39–41. doi:10.1126/science.abb3415.

- OECD. 2022. Agricultural Policy Monitoring and Evaluation 2022: Reforming Agricultural Policies for Climate Change Mitigation. Paris: OECD.

- Oreszczyn, S., A. Lane, and S. Carr. 2010. “The Role of Networks of Practice and Webs of Influencers on Farmers’ Engagement with and Learning About Agricultural Innovations.” Journal of Rural Studies 26 (4): 404–417. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2010.03.003.

- Owen, R., P. Macnaghton, and J. Stilgoe. 2012. “Responsible Research and Innovation: From Science in Society to Science for Society, with Society.” Science and Public Policy 39: 751–760.

- Peterson, H. Christopher. 2013. “Fundamental Principles of Managing Multi-Stakeholder Engagement.” International Food and Agribusiness Management Review 16 (A): 11–22.

- Randles, Sally, and Oliver Laasch. 2016. “Theorising the Normative Business Model.” Organization & Environment 29 (1): 53–73. doi:10.1177/1086026615592934.

- Reale, Filippo. 2021. “Mission-oriented Innovation Policy and the Challenge of Urgency: Lessons from Covid-19 and Beyond.” Technovation 107: 102306. doi:10.1016/j.technovation.2021.102306.

- Robertson, Michael, Brian Keating, Daniel Walker, Graham Bonnett, and Andrew Hall. 2016. “Five Ways to Improve the Agricultural Innovation System in Australia.” Farm Policy Journal 15 (1): 1–13.

- Robinson, Douglas K. R., Angela Simone, and Marzia Mazzonetto. 2021. “RRI Legacies: Co-Creation for Responsible, Equitable and Fair Innovation in Horizon Europe.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 8 (2): 209–216. doi:10.1080/23299460.2020.1842633.

- Rosenbloom, Daniel, Jochen Markard, Frank W. Geels, and Lea Fuenfschilling. 2020. “Opinion: Why Carbon Pricing is Not Sufficient to Mitigate Climate Change – And How “Sustainability Transition Policy” Can Help.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117 (16): 8664–8668. doi:10.1073/pnas.2004093117.

- Ryan, Thomas Kjeldager, Niels Mejlgaard, and Lise Degn. 2021. “Organizational Patterns of RRI: How Organizational Properties Relate to RRI Implementation.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 8 (2): 320–337. doi:10.1080/23299460.2021.1975376.

- Sachs, Jeffrey D, Guido Schmidt-Traub, Mariana Mazzucato, Dirk Messner, Nebojsa Nakicenovic, and Johan Rockström. 2019. “Six Transformations to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals.” Nature Sustainability 2 (9): 805–814.

- Scholten, V. E., and V. Blok. 2015. “Foreword: Responsible Innovation in the Private Sector.” Journal on Chain and Network Science 15 (2): 101–105. doi:10.3920/JCNS2015.x006.

- Schot, Johan, and W. Edward Steinmueller. 2018. “Three Frames for Innovation Policy: R&D, Systems of Innovation and Transformative Change.” Research Policy 47 (9): 1554–1567. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2018.08.011.

- Snow, Val, Daniel Rodriguez, Robyn Dynes, William Kaye-Blake, Thilak Mallawaarachchi, Sue Zydenbos, Lei Cong, et al. 2021. “Resilience Achieved via Multiple Compensating Subsystems: The Immediate Impacts of COVID-19 Control Measures on the Agri-Food Systems of Australia and New Zealand.” Agricultural Systems 187: 103025. doi:10.1016/j.agsy.2020.103025.

- Stilgoe, Jack, Richard Owen, and Phil Macnaghten. 2013. “Developing a Framework for Responsible Innovation.” Research Policy 42 (9): 1568–1580. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2013.05.008.

- Stitzlein, Cara, Simon Fielke, François Waldner, and Todd Sanderson. 2021. “Reputational Risk Associated with Big Data Research and Development: An Interdisciplinary Perspective.” Sustainability 13 (16): 9280.

- Swaans, Kees, Birgit Boogaard, Ramkumar Bendapudi, Hailemichael Taye, Saskia Hendrickx, and Laurens Klerkx. 2014. “Operationalizing Inclusive Innovation: Lessons from Innovation Platforms in Livestock Value Chains in India and Mozambique.” Innovation and Development 4 (2): 239–257. doi:10.1080/2157930x.2014.925246.

- Taebi, B., A. Correljé, E. Cuppen, M. Dignum, and U. Pesch. 2014. “Responsible Innovation as an Endorsement of Public Values: The Need for Interdisciplinary Research.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 1 (1): 118–124. doi:10.1080/23299460.2014.882072.

- Thaler, Richard H, and Cass R Sunstein. 2009. Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness. London: Penguin.

- Turner, J. A., A. Horita, S. Fielke, L. Klerkx, P. Blackett, D. Bewsell, B. Small, and W. M. Boyce. 2020. “Revealing Power Dynamics and Staging Conflicts in Agricultural System Transitions: Case Studies of Innovation Platforms in New Zealand.” Journal of Rural Studies 76: 152–162. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.04.022.

- Välikangas, Anita. 2022. “The Uses of Grand Challenges in Research Policy and University Management: Something for Everyone.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 9 (1): 93–113. doi:10.1080/23299460.2022.2040870.

- van der Burg, Simone, Marc-Jeroen Bogaardt, and Sjaak Wolfert. 2019. “Ethics of Smart Farming: Current Questions and Directions for Responsible Innovation Towards the Future.” NJAS - Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences 90–91: 100289. doi:10.1016/j.njas.2019.01.001.

- van Mossel, Allard, Frank J. van Rijnsoever, and Marko P. Hekkert. 2018. “Navigators Through the Storm: A Review of Organization Theories and the Behavior of Incumbent Firms During Transitions.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 26: 44–63. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2017.07.001.

- Veldhuizen, Caroline. 2021. “Conceptualising the Foundations of Sustainability Focused Innovation Policy: From Constructivism to Holism.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 162: 120374. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120374.

- Walrave, Bob, Madis Talmar, Ksenia S. Podoynitsyna, A. Georges, L. Romme, and Geert P. J. Verbong. 2017. “A Multi-Level Perspective on Innovation Ecosystems for Path-Breaking Innovation.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change, doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2017.04.011.

- Wals, Arjen E.J. 2008. Social Learning: Towards a Sustainable World. Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers.

- Wanzenböck, Iris, Joeri H Wesseling, Koen Frenken, Marko P Hekkert, and K. Matthias Weber. 2020. “A Framework for Mission-Oriented Innovation Policy: Alternative Pathways Through the Problem–Solution Space.” Science and Public Policy 47 (4): 474–489.

- Wesseling, J. H., and N. Meijerhof. 2021. “Development and Application of the Mission-Oriented Innovation Systems (MIS) Approach.” doi:10.31235/osf.io/xwg4e.