?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

In a multi-channel distribution environment, the selection and assessment of suppliers are pivotal to effective retailer performance management. This necessitates heightened qualifications and competence from suppliers. This study examines the relationship between the perception of supplier firms’ status, evaluation performance, and overall satisfaction of food buyers with suppliers in online/offline channels. In addition, this study investigates the moderating impacts of the distribution channel to explore the influence of the online/offline distribution channel on this relationship. For exploratory research, food buyers from 20 large retailers headquartered in Seoul, South Korea, were surveyed, and 110 valid questionnaires were used for analysis. Results of the study indicate that among suppliers’ firm factors, suppliers’ firm size and experience with the retailer were significantly and positively related to buyer satisfaction. Likewise, among evaluation factors, product competency and delivery reliability were significantly and positively related to buyer satisfaction. In addition, the results reveal that the distribution channel has moderating effects on the relationship between firm size and buyer satisfaction, as well as between experience with the retailer and buyer satisfaction. Therefore, the study verified that the distribution channel is an important factor that must be considered not only in the consumer market but also in the buying behavior research of the business-to-business market.

1. Introduction

With the rapid growth of e-commerce and the emergence of various retail formats (Izogo & Jayawardhena, Citation2018), the distribution environment is rapidly evolving to a multi-channel and omnichannel environment without boundaries among channels. In a complex and organic distribution environment that varies from day to day, the position of suppliers (producing or supplying goods) is becoming more important to retailers, and retailers’ efforts to select and secure the best suppliers are accelerating (Wilson, Citation2000). In particular, in the e-commerce environment, more candidate suppliers and purchasing organizations with diverse needs and functions are mutually associated based on a diversity of product varieties, making proper supplier selection more difficult for retailers (Pearson & Ellram, Citation1995).

To better address this, in many studies, the cost of inputs is considered to be the most important criterion used by buying firms to evaluate the performance of suppliers, while quality, delivery and service have also been presented as commonly used evaluation factors (Kannan & Choon Tan, Citation2002). However, the major inputs that are most crucial in the evaluation process are the decision-maker’s perceptions of the importance of evaluation attributes (Ordoobadi, Citation2009). The assessment of criteria is determined by matching the decision-maker’s expectations for the supplier with the organizational aims, as well as by the decision-maker’s individual preferences and behavioral intentions (Anderson & Chambers, Citation1985). Because of the inconsistent usage of criteria (e.g., common evaluation factors, decision-maker perceptions), it is difficult to relevantly evaluate the suppliers from the perspective of the decision-maker. Furthermore, the antecedents of outcome variables (i.e., firm performance, relationship satisfaction, long-term orientation) validated in previous studies have been mostly non-economic factors, such as buyers’ buying perspectives and characteristics, buyer-supplier relationship resources (i.e., trust, commitment, cooperation) (e.g., Kim et al., Citation2022; Nair et al., Citation2015).

In addition, due to changes in the distribution environment, the preferred products of consumers, the criteria of product selection, and the consumption value are constantly changing (Cheraghi et al., Citation2011). Consumers’ needs manifest differently depending on the characteristics of each retailer. Consequently, retailer’s buying behavior differs depending on how retailers interpret customers’ needs (Skytte & Blunch, Citation2005). In this regard, a new approach to understanding retailer’s buying behavior in multi-channel distribution environments is needed (Choi, Citation2022; Mohammed et al., Citation2022).

Therefore, the main objectives of this study are to:

Identify the supplier characteristics and evaluation variables that are to be considered for buyer satisfaction in a multi-channel retail environment.

Investigate the moderating effects of online/offline distribution channels on the relationship between supplier variables and buyer satisfaction.

As explained in the introduction, there is inconsistent criteria for evaluation and changes in the market, so this study set two research goals. This investigation provides three facets of research contribution. First, this study asks buyers about how well retailers’ various online/offline formats work in order to provide empirical evidence that reflects the modern retail environment. Second, this study focuses on supplier-oriented factors (i.e., supplier characteristics, performance evaluation, capability evaluation) to provide practical implications to academics and industry practitioners. Third, the theoretical and practical importance of distribution channel in the buying behavior of online/offline buyers are verified.

This study proceeds in the following order: (1) hypotheses are formed based on a literature review; (2) a research model for distribution channel effects is presented based on the hypotheses; (3) data and methods of analysis used in this study are described; and (4) the results and the practical and academic implications are discussed.

2. Literature review

2.1. Supplier selection and evaluation

Due to the growth of the retail industry, the corporatization (chaining) of retailers, the increased number of products handled and the volume of transactions, the reliance of retailers on suppliers has continued to increase, along with the increasing importance of supplier management (Ganesan, Citation1994; Kang, Citation2018). In general, supplier management is based on the following four dimensions: (1) effectively selecting the supplier; (2) addressing suppliers’ shortcomings; (3) evaluating the performance of the supplier; and (4) determining whether to buy continuously or terminate the relationship (e.g., Davies & Treadgold, Citation1999; Kannan & Choon Tan, Citation2002). Among them, supplier selection and supplier evaluation are the most important elements of the purchasing function that can directly provide financial impacts to the business (Bilişik et al., Citation2012; Kannan & Choon Tan, Citation2003).

The primary objective of supplier selection is to align the buyer firm’s requirements and the supplier’s capabilities (e.g., Cheraghi et al., Citation2011; Petersen et al., Citation2005). Supplier evaluation is a systematic mechanism to ensure suppliers meet the present and future business demands of the buyer and that the realized profits equate to the targeted profits (e.g., Gallear et al., Citation2022; Prahinski & Benton, Citation2004). Consequently, a continuing challenge of supplier selection and evaluation is determining whether the supplier is meeting the needs of the buying firm by delivering quality products, providing on-time delivery, and many other factors (Kant & Vithalrao Dalvi, Citation2017).

Depending on the perspectives related to the selection and evaluation of suppliers, the influence on individual factors of the performance of buying centers may vary. Evidence for this can be found in the study of Nair et al. (Citation2015). By considering both operational and strategic perspectives, the authors found that the buying center’s strategic and operational supplier selection had a significant impact on the supplier’s strategic and operational performance evaluation. However, the supplier’s strategic and operational performance evaluation had a different effect on the purchasing performance factors of the buying center (i.e., delivery, flexibility). Xie et al., Citation2013 study also showed a correlation between supplier selection perspectives (market-oriented, relationship-oriented) and supplier performance, suggesting that differences in perspectives and attributes of supplier selection are important determinants of supplier performance. Meanwhile, in a supplier performance and capability evaluation model assessing supplier efficiency, Sarkar and Mohapatra (Citation2006) found that most supplier evaluation factors in previous studies focused on performance perspectives. Thus, the authors suggested that depending on the characteristics of each purchasing category, retailers’ supplier management strategy should vary and, in the supplier evaluation, suppliers’ capability factors should be considered together with performance factors for future potential. Thus, criteria and model development studies have sought to identify certain factors to evaluate the best supplier.

However, many studies have targeted specific categories of retailers, which is insufficient to explain the overall purchasing behavior of retailers in a multi-channel environment. For instance, studies focused on supermarket chains (e.g., Hansen, Citation2001; Rong et al., Citation2022), e-commerce (e.g., Kaushik et al., Citation2022; Liu et al., Citation2019), independent retailers (e.g., Makhitha, Citation2017) and product categories like fresh food, dairy and frozen food (e.g., Lin & Wu, Citation2011; Van Everdingen et al., Citation2011). First, in a study of criteria used by Taiwan supermarket retailers to select fresh fruit and vegetable suppliers, cost, product quality, product consistency, and safety of the product were found to be the most important supplier selection criteria (Lin & Wu, Citation2011). In addition, according to the results of a study of seafood supplier selection in Chinese e-commerce, cold-chain technology had the highest integrated importance weight among the supplier selection criteria, followed by transportation capacity, inventory environment, and order management system (Liu et al., Citation2019).

Their results indicated that, in addition to the importance of the category characteristics of freshness-sensitive fresh food, more specialized capabilities are required (compared to the level required in the offline channel) in the ordering, inventory management, and delivery stages due to the channel characteristics of e-commerce. As such, these findings suggested that criteria attributes vary depending on the product category and the channel characteristics of the retailer, and the priority of importance varies. On the other hand, it also shows the need for empirical research that can reflect more recent retail environments to better understand overall food purchase behavior.

2.2. Buyer satisfaction in a relationship with suppliers

Satisfaction in the relationship between two organizations includes both economic satisfaction and social satisfaction (Geyskens & Steenkamp, Citation2000; Geyskens et al., Citation1999) and refers to a positive emotional response between partners (Frazier et al., Citation1989). Partners can perform better when they are connected by a positive relationship between organizations (Lai, Citation2007), and satisfaction contributes to improving relationship performance between organizations (Wong & Zhou, Citation2006).

However, these relationship resource variables are limited due to the difficulties in utilizing them as practical assessment variables for evaluating and managing suppliers at actual industrial sites. The variables are also difficult to measure objectively. In the organizational relationship perspectives of the purchaser and supplier, relationship resources (e.g., trust, commitment, satisfaction, dependence) have been studied as an important topic. In addition, most of these relationship resources show a significant correlation to outcome variables such as organizational performance and long-term orientation (e.g., Abdul-Muhmin, Citation2005; Ganesan, Citation1994; Mungra & Kumar Yadav, Citation2020). First, Mungra and Kumar Yadav (Citation2020) conducted a mediation impact study of satisfaction between trust-commitment and relational outcomes (performance, governance cost) in the relationship between manufacturers and their suppliers. They demonstrated that a manufacturer’s satisfaction with the supplier has a mediation impact between the respective trust and commitment and the respective performance and governance cost variables. In addition, in a study by Kannan and Choon Tan (Citation2006), the authors verified that the successful relationship performance (economic/non-economic) between the buyer and the supplier is a direct influencing factor leading to the performance of the buying firm, while the buyer-supplier engagement and supplier selection are important influencing factors that precede the successful relationship performance.

On the other hand, unlike relationship resources such as trust, commitment, and satisfaction, which show positive impacts on organizational performance, previous studies have shown that the excessive and risky degree of dependence on trading partners has negative impacts on organizational performance (e.g., Ganesan, Citation1994; Heide & John, Citation1988; Lusch & Brown, Citation1996). Caniëls and Gelderman (Citation2007) defined dependence using four key characteristics—the financial size of trading resources between the two companies, the criticality of resources, availability of alternative resources, and replacement cost required to replace partners. Dependence on partners leads to organizational uncertainty or unpredictability, a problematic situation, which makes the organization vulnerable (Gelderman & Van Weele, Citation2004).

These findings suggested that the relationship resources between the organizations directly affect the firm performance, or preceding or trailing supplier evaluation, thereby having an indirect impact as significant variables. However, because of limitations on relationship resources variables (i.e., difficult to measure objectively or to evaluate in a practical setting), this study seeks to confirm functional antecedents that affect firm performance by verifying the correlation between the evaluation factors actually used and needed by retail buyers to evaluate suppliers and buyer satisfaction.

2.3. Variables contributing to organizational purchasing behavior

In the retailer’s buying behavior process, the purchasing manager is deeply involved in supplier management and the supply decision-making process (Chen et al., Citation2014. With the growth of the retail industry, the role of the purchasing manager in the supply chain management of large retailers is gaining greater importance (e.g., Barney, Citation2012; Kim & Takashima, Citation2018; Kim, Miao, and Hu 2021). Da Silva et al. (Citation2002) evaluated the effect of retail buyer variables on the buying decision-making process among 35 UK clothing retailers. They found that the older the buyer, the greater the value placed on cost by female buyers, while older buyers with less experience as buyers placed greater importance on delivery and responsiveness. These tendencies showed significant differences in the buying decision-making process according to the buyer characteristics (e.g., age, gender, buyer experience).

In addition, variables such as the length of the relationship, relationship phase, and relationship lifecycle, which measure the relationship degree with the supplier, have been described in several prior studies as factors that directly or indirectly significantly influence retailer’s buying behavior (e.g., Jap & Ganesan, Citation2000; Ngouapegne & Chinomona, Citation2018; Van Everdingen et al., Citation2011). In the Jap and Ganesan (Citation2000) study on the control mechanisms (supplier’s transaction-specific investments [TSIS], relational norms, explicit contracts) and relationship life cycle, evidence was presented that the significance of the relationship between retailers’ TSIS and retailers’ perception of supplier commitment to the relationship varies depending on the relationship phase (exploration, buildup, maturity, decline, deterioration). In addition, the length of the relationship showed significant effects on relationship satisfaction. These results suggest that both the variables of absolute time and the relative degree of the retailer-supplier relationship have significant effects on retailer buying behavior.

Meanwhile, active research in consumer buying behavior considering the characteristics of online and offline channels has not led to further research on retail buyers’ buying behavior. Sheth (Citation1980) described merchandise buying behaviors from organizational purchasing perspectives, distinct from consumers’ merchandise buying behavior. Key constructs of the Sheth’ theory of merchandise buying behavior are merchandise requirements and supplier accessibility. The merchandise requirements are what consumers want from retailers’ products and are made due to inter-organizational factors (e.g., retailer size, type of retailer, management method) and intra-organizational factors (e.g., product category, brand, type of decision). In the end, they are expressed as the purchasing needs and motives of the retailer and the purchase criteria (Hansen & Skytte, Citation1998). Supplier accessibility is a set of choice options that can fully satisfy the requirements for the product of the retailer (i.e., the competitive structure of the industry, relative marketing efforts, and corporate image) (Sheth, Citation1981).

As a result, retailers’ merchandise decision-making is determined by the retailers’ purchasing needs based on the internal and external purchasing environment and the available supplier options corresponding thereto (Fairhurst & Fiorito, Citation1990). Nevertheless, the reasons why retail buying behaviors have not been studied from the distribution channel perspective can be described as follows. This gap stems from the sensitivity of the issue of evaluating suppliers in the retail industry and the difficulty in obtaining data for research. This highlights this study’s significance in researching differences in channel characteristics, which are one of the inter-organizational characteristics overlooked by the existing literature.

3. Hypotheses development

Buyers rely primarily on supplier characteristics, such as suppliers’ firm size, to assess suppliers’ trustworthiness. In particular, in the case of a trading relationship with little-known or inexperienced suppliers, the firm size is an important criterion (Doney & Cannon, Citation1997). The extensive resources of large suppliers and the difference in power between large and medium-sized enterprises seen in buyer-supplier relationships are shown to have the potential to lead to organizational performance (Benton & Maloni, Citation2005; Tsai, Citation2001; Villena et al., Citation2011).

In the supplier evaluation process, experience with the retailer is a significant criterion considered along with past sales performance. Van Everdingen et al. (Citation2011)’s study defined “relationship length” as the business experience with a supplier, and it showed a significant positive effect of relationship length on a retailer’s new product adoption probability, as did other previous studies (eg., Doney & Cannon, Citation1997; Jap & Ganesan, Citation2000; Mungra & Kumar Yadav, Citation2020). In addition, a significant negative effect of relationship dependence on a retailer’s adoption probability has also been observed. Dependence is defined as the degree to which a company depends on its partners, which means the degree to which its partner provides valuable resources to a company (Kang, Citation2018).

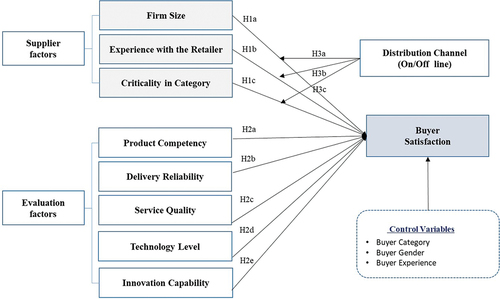

As such, based on previous studies’ verification results, suppliers’ position evaluation criteria within the market and retailers—namely, (1) firm size, (2) experience with the retailer and (3) criticality in the buyers’ category—were respectively found to be significantly correlated with the firm performance. As follows, the first hypothesis to verify the significant correlation between supplier firm’s factors and buyer satisfaction is presented.

H1

Supplier factors of (a) firm size, (b) experience with the retailer, and (c) criticality in buyers’ category will affect buyer’s overall satisfaction.

“Suppliers” operational performance with the retailer’ is the most important criterion for buyers’ decision-making in supplier evaluation. Its importance has been demonstrated by existing studies, which showed that the importance of mainly operational variables such as product quality, delivery service (e.g., Abdul-Muhmin, Citation2005; Makhitha, Citation2017) and supported service and sales activity (e.g., Chumpitaz & Paparoidamis, Citation2020; Hansen, Citation2001). In a study of 1,218 food & beverage buying centers, Chumpitaz and Paparoidamis (Citation2020) examined the relative effects of product quality, delivery service, sales quality, and problem solving to induce relationship satisfaction. It showed that product offering quality directly or via sales team quality had a significant positive effect on relationship satisfaction, and delivery service directly showed a significant positive effect on relationship satisfaction.

On the other hand, several studies suggested the necessity and importance of the capability factors like technology and research and development (R&D), which are described as long-term impact factors on the achievement of supply chain management goals (e.g.,Narasimhan et al., Citation2001; Sarkar & Mohapatra, Citation2006). In a hybrid decision model study for supplier selection of online fashion retailers (Kaushik et al., Citation2022), technical soundness of operational competency was defined as the advanced production infrastructure for consistent quality product production, and was described as one of the most preferred attributes for retailers. Additionally, the innovativeness attribute, which refers to product R&D and future trend prediction, was also highlighted as an important evaluation factor that is prioritized for all online/offline retailers. Also, in the selection and evaluation study of a Chinese fresh food supplier (Rong et al., Citation2022), the innovativeness factor is defined as innovation ability, which means securing financial resources and investment capacity for future development and should be emphasized as an important element in the era of globalization. Thus, capability variables such as technology level and innovation capability are also confirmed as an important evaluation factor required in a multi-channel retail environment. Therefore, the second hypothesis suggests that the buyer’s evaluation perceptions on the five factors—namely, the suppliers’ performance factors of (1) product competency, (2) delivery reliability, and (3) service quality, and the suppliers’ capability factors of (4) technology level and (5) innovation capability—and buyer satisfaction will be significantly correlated.

H2

Buyers’ evaluation perceptions of (a) product competency, (b) delivery reliability, (c) service quality, (d) technology level and (e) innovation capability of supplier will affect their overall satisfaction.

According to a study on the association between e-commerce activity of small and medium‐sized enterprises (SMEs) and internal and external antecedents, enterprise age and size had negative relationships with e-commerce trading activity (Pickernell et al., Citation2013). These results suggest that suppliers’ age and size will be significantly associated with activity of online channel. Furthermore, consumers’ buying behavior studies have shown that it is not difficult to find examples of significant comparative studies of shopping behavioral characteristics by online and offline channels (e.g., Dawes & Nenycz-Thiel, Citation2014; Degeratu et al., Citation2000). Based on previous research, the following hypothesis is proposed stating that the difference between online/offline channels will have an effect on the correlation between buyer satisfaction and buyers’ perception of supplier’ firm factors.

H3

Relationships between the respective supplier factor of (a) firm size, (b) experience with the retailer, and (c) criticality in buyers’ category and overall satisfaction are moderated by (online/offline) distribution channel

In sum, the research model tests three hypotheses with eleven sub-hypotheses, as shown in Figure . The first hypotheses has three sub hypotheses; the second have five sub-hypotheses; and the third has three sub hypotheses.

4. Research methodology

4.1. Sample and data collection

The primary tool used to collect data was a structured questionnaire. The survey instrument was composed of three principal sections based on a literature review. The first part assembled supplier information such as firm size, experience with the retailer, and criticality (supplier’s sales percentage) in buyers’ category. The second part elicited attitudes toward a set of variables that have been hypothesized to be significant in supplier assessment. The last section included questions about the demographics of retailers and buyers. The questionnaire was reconstructed based on various previous studies (see Tables ) that researched the supplier evaluation in food categories and e-commerce industries. The items were evaluated using a five-point Likert scale. The questionnaire was pilot-tested with buyers responsible for food purchasing in three retailers. These pilot studies revealed several questions lacking clarity, which were fixed.

Additionally, to increase the rigorousness of the study, the following analytical conditions were applied to the survey. The survey was conducted by asking online and offline (i.e., multi-channel retailer) buyers who were in charge of purchasing the food categories. The underlying conditions were that (1) the characteristics between online buyers and offline buyers were not homogenous, but (2) each buyer had homogeneous buying behavior. Therefore, each buyer (i.e., online- and offline buyer) had consistent tendencies regarding their evaluations. In addition, it was assumed that the headquarters of large retail companies were located in the same socio-economic region (i.e., Seoul) so that they were not affected by socio-economic features around the companies. Because the socio-economic features around the headquarters may influence the buyer’s behavioral decision making, the same regions with similar socio-economic surroundings were assumed.

The e-mailed survey was first sent to 340 buyers in multi-channel retailers from the listing of buyers of Buyer Co., Ltd., and the final 66 surveys were secured over three weeks by reminding e-mail recipients (6/22/22–7/16/22, return rate 19.4%). The survey of only e-commerce buyers was conducted by a survey agency to ensure a sufficient number of responses and a total of 44 completed surveys were delivered over two weeks through 1,350 text messages providing the survey link (7/12/22–7/28/22, return rate 3.3%). Ultimately, 110 completed questionnaires were secured for the study. According to data from the National Statistical Office of the Republic of Korea, there are 59,000 professionals in the field of planning and promoting commercial products across all industries (2017, 0.22% of the total number of employed individuals in Korea). Additionally, the G*Power analysis (Faul et al., Citation2009) indicates that the minimum sample size is 92, so the sample size obtained (n = 110) is over the minimum.

Each buyer chose a random, relatively new supplier (sales relationship of 24 months or less) with medium sales in the buyer’s category among suppliers subject to the evaluation and then evaluated the supplier. Considering that previous studies (e.g., Jap & Ganesan, Citation2000) showed the dynamic influence of relationship development stage between purchasers and suppliers, it was limited to new suppliers. Tables describe variables for responding retailer buyers and demographics of the evaluated suppliers.

Table 1. Demographics of responding buyers and evaluated suppliers

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Variables

Appendix 1 shows the questionnaire used in the study. The dependent variable for the study was buyer satisfaction. As shown in Appendix 1, four questions (BS1 to BS4) were used to measure the level of buyer satisfaction in relationship with the supplier, constructing a latent variable in which higher scores indicated a more satisfied relationship with the supplier. The main independent factors were supplier factor and evaluation factor. The supplier factor was measured by three items (SS, ER, CC). The evaluation factor was constructed as five latent variables: product competency, delivery reliability, service quality, technology level, and innovation capability with, respectively, PC1 to PC6, DR1 to DR2, SQ1 to SQ3, TL1 to TL3, and IC1 to IC2. To test the validity of the six latent variables, a confirmatory factory analysis (CFA) was used. The result is presented in the measure validation section. As the moderator factor between supplier factor and buyer satisfaction, distribution channel of retailer was used. Distribution channel was measured with one item (DS). Furthermore, to control for the effect of buyer characteristics, three questions (BC, BG, BE) were used.

4.3. Empirical analytic models

In this study, the control variables (buyers’ characteristics) and independent variables (suppliers’ firm factors and evaluation factors) were systematically introduced stepwise to determine the most suitable model for the research objective. Model 1 is used to verify H1 (H1a, H1b, H1c) and H2 (H2a, H2b, H2c, H2d, H2e) without considering the distribution channel; Model 2 additionally includes only the distribution channel variable as a moderator, and Model 3 is used to test H1, H2 and H3 by entering additional interaction terms between the distribution channel and supplier characteristics (firm size, experience with the retailer, and criticality in buyers’ category). The following Models 1 and 2 are used to test Hypotheses 1 and 2.

The equation for Model 1 is:

where, BS is buyer satisfaction; BC1 ~ BC7 denote buyer category dummy variables (meat and seafood, dried food, deli and bakery, chilled and frozen food, ambient food, snack and beverages, others vs. produce, respectively BC1 to BC7); BG is buyer gender; BE refers to buyer experience; SS is the firm size of supplier; ER denotes experience with the retailer; CC is the criticality (percentage of sales in buyer category); PC is product competency; DR denotes delivery reliability; SQ is service quality; TL is technology level; and IC refers to innovation capability.

The equation for Model 2, where distribution channel is adopted, is:

where, DC is distribution channel.

Finally, the equation for Model 3, where distribution channel interaction terms are additionally adopted, is:

4.4. Measure validation

Because of the sample size, a partial least square was chosen for confirmatory factor analysis. In the confirmatory factor analysis, the item loadings of each item exceeded 0.5 (Table ). Of note, however, the “offering a variety of product” measurement variable of product competency was excluded from the final model because of its low loading value. In order to verify the validity of the research model, convergent validity and discriminant validity were checked based on the rules of thumb proposed by Bollen (Citation1989). Convergent validity is evaluated by the loading value of the measurement, composite reliability, Cronbach’s Alpha and AVE values.

Table 3. Constructs and measures

Table shows the overall fit of this research model. The composite reliability exceeded 0.878, the Cronbach-α was 0.622 or more, and the AVE value was above the threshold of 0.5, ensuring the reliability of each factor. The heterotrait-monotrait ratio of the correlations (HTMT) is used to evaluate the discriminant validity between latent constructs in structural equation modeling. This evaluation technique was proposed by Henseler et al. (Citation2015), who pointed out that sensitivity is insufficient in the conventional discriminant validity evaluation technique suggested by Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981), which compared the correlation coefficient between latent variables and the square root of the mean-variance extract. It is claimed that there is a clear discriminant validity when the calculated HTMT value between latent constructs is lower than 0.85. Based on the HTMT results (Table ), our measurement model exhibits sufficient discriminant validity.

Table 4. Discriminant validity

A cross-loadings table (Table ) was constructed in order to further assess the validity of our measurement instruments (Gefen et al., Citation2000). Each item loading in the table is much higher on its assigned construct than on the other constructs, indicating adequate convergent and discriminant validity.

Table 5. Item loadings and cross loadings

Hence, through confirmatory factor analysis for each measurement item, it was found that each variable explained the latent variables with statistical significance.

4.5. Methods for hypothesis testing

In studies that connect organizations and members, it is common for members to be affected by different variables according to the organization level due to their structural characteristics. Thus, hierarchy linear modeling (HLM) is used to examine the influence relationship between each retail buyer’s evaluation perceptions and satisfaction according to the difference in the online/offline channel. HLM estimation was conducted with nested regression function within Stata program. Nested regression conducts the sequential estimation by adding a bundle of independent variables to the basic model. In this adding procedure, the measurement errors are adjusted to make that all regressions are comparable (StataCorp, Citation2021).

The basic assumptions for HLM analysis are confirmed by the Wald test derived from HLM execution: (1) the standard normal distribution of the error terms in each level, (2) the multivariate normal distribution of parameters, and (3) the errors in the two levels are not correlated. In the Wald test results, the significant F statistic of each level shows that the essential assumptions for HLM execution are satisfied (Table ) (Miyazaki & Maier, Citation2005). Consequently, HLM simultaneously executes three models (Model 1 to Model 3), considering the associated covariance to minimize the measurement error across three models (Matsuyama, Citation2013). Therefore, the selected model is suitable for the purpose of the project. The change of F—values and change of R2 between the step-by-step models will be used for the robustness of the HLM estimations.

Table 6. Wald test results

5. Results

We assessed whether the model fit improves by comparing the deviance statistic between these models by functions of the nested model, HLM. In accordance with our research hypotheses, we explored random coefficient models using the likelihood-ratio (LR) test and contrast F-values to choose the appropriate model. We demonstrate the parameter estimates for the final model in Table .

Table 7. Hierarchical linear model results for buyer satisfaction

Model 1 is the random coefficient model only with the independent variables and control variables. It shows that product competency and delivery reliability are statistically significant, with a weak negative correlation between the firm size of the supplier and buyer satisfaction. Accordingly, H1(H1a) and H2(H2a, H2b) are partially supported. Product competency and delivery reliability in the performance evaluation variables have significant positive effects on buyer satisfaction. This result means that the higher the performance evaluation variables are, the higher the buyer satisfaction will be. Meanwhile, any capability variables (TL, IC) in the evaluation variables do not have a significant effect on buyer satisfaction. We also could not identify more significant effects after adding the moderator (DC) variable in Model 2.

Meanwhile, in Model 3 with the interaction terms (SSxDC, ERxDC, CCxDC), experience with the retailer and buyer category 5 (chilled and frozen vs. produce) are newly identified as significant, and the sign of the firm size of the supplier has been converted to positive. Product competency and delivery reliability continue to be significant in Model 3. The results showed that two interaction terms had negative impacts on buyer satisfaction (SSxDC, ERxDC). That is, the positive impact of the firm size of suppliers and experience with the retailer on buyer satisfaction was found to be lower for online distribution channels compared to multi-channel retailers. Finally, the significant F-value difference between Model 2 and Model 3 means the model 3 became more sophisticated and accurate. Therefore, hypotheses 3a and 3b that the distribution channel would moderate buyers’ evaluation perceptions that affect overall satisfaction were accepted. Consequently, H1(H1a, H1b), H2(H2a, H2b), and H3(H3a, H3b) are partially supported.

These results support previous studies showing that category characteristics (e.g., Da Silva et al., Citation2002; Sarkar & Mohapatra, Citation2006), supplier’s firm size (e.g., Mungra & Kumar Yadav, Citation2020; Villena et al., Citation2011) and length of experience with the retailer (e.g., Jap & Ganesan, Citation2000; Ngouapegne & Chinomona, Citation2018) influence buyer satisfaction. Additionally, this study proved that product competency and delivery reliability, which have been important in previous supplier evaluation studies, have significant positive effects on buyer satisfaction. On the other hand, while the variables of supplier firm size and experience with the retailer have demonstrated to have a significant and positive influence on buyer satisfaction, significant and negative relationships were shown in the interaction terms with the distribution channel. These mean that the firm size of the supplier and experience with the retailer attributes respectively increase buyer satisfaction as separate influencers. However, the combined effect of firm size of the supplier and experience with the retailer (i.e., interaction) decrease the buyers’ satisfaction within online channels. Thus, relationships between supplier factors and buyer satisfaction are moderated by distribution channel. Detailed interpretation of the results is covered in the discussion section.

6. Discussion and implications

6.1. General discussion

In this study, we verified the correlations of various supplier evaluation criteria with buyer satisfaction, in order to identify antecedents that have a significant effect on the buyer-supplier relationship satisfaction in the multi-channel retail environment. Additionally, we offer new implications that have not been verified in previous studies of the buying behavior of traditional or e-commerce retailers.

Product and delivery attributes, which were found to be the most important supplier evaluation attributes in the offline channel, are still important evaluation factors for multi-channel retailers. On the other hand, we have not been able to identify significant correlations between buyer satisfaction and the respective technology level and innovation capability variables, which have recently been highlighted in the retail industry. These results suggest that, for buyers who are working on the ground, operational evaluation factors that are directly connected to the daily routine have greater importance than capability factors. Additionally, the product and delivery attributes among the operational evaluation factors can be recognized as variables directly related to the performance of the retailer or the buyer. Especially, in the case of large retailers surveyed in this study, based on the fact that they have greater supplier accessibility and a competitive supplier pool, it can be inferred that there may be less awareness of the need of the supplier capability of buyers. Furthermore, the nonsignificant results of this and previous studies can be attributed to the general preference of retail buyers, in developing innovative processes and products, to make decisions based on their own market research, knowledge and experience rather than relying on suppliers’ capabilities and insight (Da Silva et al., Citation2002). These results reflect the reality of buyers’ perception of supplier evaluation and can also be interpreted as a result that proves the importance of a balanced evaluation system (performance and capability) of retailers.

The variables of supplier firm size and experience with the retailer have also been demonstrated to have a slightly positive significant effect on buyer satisfaction in this study. Additionally, through the interaction terms (SSxDC, ERxDC) with the distribution channel, they showed inverse negative effects on the buyer satisfaction, which is negative moderating effects in online channel. These results support previous studies showing that firm age and size are significantly associated with e-commerce trading activity (Pickernell et al., Citation2013; Ramanathan et al., Citation2012). In addition, final Model 3 exhibits the strongest explanatory power. These results suggest that the difference between the online/offline channels is an important business characteristic and may cause differences in buying behavior. Because the online channel is not limited by space, it can offer a diverse product range that is unrivaled by the offline channel (Sarkar & Das, Citation2017). In a comparative study of price, assortment, and delivery time between an online channel and bricks-and-mortar retailing, Li et al. (Citation2015) claim that the online channel and the offline channel have different assortment strategies. These differences in the assortment strategy and products handled between online/offline channels can lead to differences in the characteristics of suppliers sourcing products (i.e., firm size, number of suppliers available). As such, the significant difference in buyer evaluation perception according to the relationships between distribution channel and supplier factors suggested the importance of strategic positioning that suppliers should take depending on the channel.

However, even though many studies on consumer buying behavior based on online/offline channels have been conducted, few studies on the organizational buying behavior of retailers based on online/offline channels have been conducted. As online retailers get products directly from suppliers for fresher products and faster delivery, supplier management has emerged as a critical function in e-commerce. Therefore, despite the growing industry interest and need for research in buying behavior according to retailer channel, certain topics had only been studied at the conceptual and theoretical level due to the limitations of access and data for information. Thus, this study has particular significance in that it surveyed working-level food buyers in various online/offline channels directly, thereby verifying the functional antecedents that actually affect buyer satisfaction.

6.2. Practical and academic implications

Through empirical validation of the food buying behavior of multi-channel retailers, this study provides some important implications relevant to academia and industry. This study has theoretical significance in that it expands the understanding of the inter-organizational factors that affect retailers’ decision making in Sheth (Citation1981)’s theory of merchandise buying behavior. In doing so, it newly identifies the distribution channel as one of the organizational characteristics affecting retailers’ buying behavior, and highlights distribution channel as an important variable to consider in the multi-channel retail environment. Additionally, supplier’s firm characteristics (i.e., firm size, age of experience) have been mainly studied as incidental attributes to correct the influence of other variables of interest (e.g., Doney & Cannon, Citation1997; Jap & Ganesan, Citation2000). However, through this study, it was verified that it is an essential variable to be considered for supplier evaluation in organizational purchasing behavior studies, especially in the online business.

Additionally, the negative correlation with buyer satisfaction shown in the interaction terms (SSxDC, ERxDC), suggests important practical implications to the multi-channel retailers and manufacturers. Due to the online business characteristics (store-picking, integrated sourcing through offline suppliers) of multi-channel retailers, for multi-channel buyers, channel characteristics have not been considered important in supplier evaluation. However, multi-channel retailers need to change from integrated purchasing focused on the offline channel, and base their buying behavior characteristics on e-commerce buyers, as shown in this study. In addition, for suppliers to maintain business relationships with existing retail customers and to secure additional potential client companies, the e-commerce buyers’ preference for smaller and newer suppliers will be useful to suppliers. Therefore, the suppliers need to recognize the differences in buying behavior between online and offline buyers. Thus, suppliers should consider crafting a sales strategy, clear positioning, and effective communication for each channel.

7. Conclusions

This study explored the correlation between multi-channel buyers’ perception of supplier evaluation and their satisfaction, considering the moderating effects of distribution channel. The results of this study confirmed the importance of product competency and delivery reliability, which had been emphasized in previous studies. However, the relationship between the evaluation perception of relative technology level and innovative capability and the buyer satisfaction was still insignificant. On the other hand, the significant influence shown in the interaction terms between the supplier’s firm characteristics and distribution channel are very interesting results, which provide meaningful theoretical and practical implications. The theoretical concept of organizational characteristics influencing purchasing behavior has been expanded and the importance of the supplier’s firm factors has been highlighted for future research on organizational purchasing behavior. In addition, from a practical point of view, this study suggested to multi-channel buyers and manufacturers the necessity of changing merchandising and sale strategies according to the characteristics of the distribution channel. Consequently, this study has a great contribution to academia and retail industries in that it drew empirical implications by confirming a significant correlation between channel characteristics and supplier-oriented attributes from multi-channel practitioners.

7.1. Limitations and future research

This study has some limitations that should be considered in future studies. First, it is possible that there may be important factors that are missing from the evaluation factors of this study. The capabilities required of suppliers, such as sustainability (e.g., Mohammed et al., Citation2019; Okwu & Tartibu, Citation2020) and digitalization (e.g., Mohammed et al., Citation2022; Pratap et al., Citation2022), are constantly changing due to rapid changes in the retail environment. Therefore, follow-up research should be conducted considering the needs of retailers. Additionally, this study used survey data from working-level practitioners. However, corporate decisions are made through involving different constituents of buying centers, including the opinions of decision makers (Chumpitaz & Paparoidamis, Citation2020). Therefore, it is necessary to conduct a qualitative study that includes the opinions of decision-makers in the future study of organizational purchasing behavior. Thus, the study will provide more meaningful implications through various analyses and approaches.

Appendix_questionnaire.docx

Download MS Word (35.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The participants of this study did not give written consent for their data to be shared publicly, so due to the sensitive nature of the research supporting data is not available.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2283229.

References

- Abdul-Muhmin, A. G. (2005). Instrumental and interpersonal determinants of relationship satisfaction and commitment in industrial markets. Journal of Business Research, 58(5), 619–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2003.08.004

- Anderson, P. F., & Chambers, T. M. (1985). A reward/measurement model of organizational buying behavior. Journal of Marketing, 49(2), 7–23. https://doi.org/10.2307/1251561

- Barney, J. B. (2012). Purchasing, supply chain management and sustained competitive advantage: The relevance of resource‐based theory. The Journal of Supply Chain Management, 48(2), 3–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-493X.2012.03265.x

- Benton, W. C., & Maloni, M. (2005). The influence of power driven buyer/seller relationships on supply chain satisfaction. Journal of Operations Management, 23(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2004.09.002

- Bilişik, M. E., Çağlar, N., & Nalan Alp Bilişik, Ö. (2012). A comparative performance analyze model and supplier positioning in performance maps for supplier selection and evaluation. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 58(12), 1434–1442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.09.1128

- Bollen, K. A. (1989). Structural equations with latent variables (Vol. 210). John Wiley & Sons. https://snu-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/f/1l6eo7m/82SNU_INST21453788750002591

- Caniëls, M. C., & Gelderman, C. J. (2007). Power and interdependence in buyer supplier relationships: A purchasing portfolio approach. Industrial Marketing Management, 36(2), 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2005.08.012

- Chen, I. J., Yeob Lee, Y., & Paulraj, A. (2014). Does a purchasing manager’s need for cognitive closure (NFCC) affect decision-making uncertainty and supply chain performance? International Journal of Production Research, 52(23), 6878–6898. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2014.910622

- Cheraghi, S. H., Dadashzadeh, M., & Subramanian, M. (2011). Critical success factors for supplier selection: An update. Journal of Applied Business Research (JABR), 20(2), 91–108. https://doi.org/10.19030/jabr.v20i2.2209

- Choi, T.-M. (2022). Achieving economic sustainability: Operations research for risk analysis and optimization problems in the blockchain era. Annals of Operations Research, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-021-04394-5

- Chumpitaz, R., & Paparoidamis, N. G. (2020). The impact of service/product performance and problem-solving on relationship satisfaction. Academia Revista Latinoamericana de Administracion, 33(1), 95–113. https://doi.org/10.1108/ARLA-11-2018-0266

- Da Silva, R., Davies, G., & Naude, P. (2002). Assessing the influence of retail buyer variables on the buying decision‐making process. European Journal of Marketing, 36(11/12), 1327–1343. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560210445209

- Davies, G., & Treadgold, A. (1999). Buyer attitudes and the continuity of manufacturer/retailer relationships. Journal of Marketing Channels, 7(1–2), 79–94. https://doi.org/10.1300/J049v07n01_04

- Dawes, J., & Nenycz-Thiel, M. (2014). Comparing retailer purchase patterns and brand metrics for in-store and online grocery purchasing. Journal of Marketing Management, 30(3–4), 364–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2013.813576

- Degeratu, A. M., Rangaswamy, A., & Jianan, W. (2000). Consumer choice behavior in online and traditional supermarkets: The effects of brand name, price, and other search attributes. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 17(1), 55–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-8116(00)00005-7

- Doney, P. M., & Cannon, J. P. (1997). An examination of the nature of trust in buyer–seller relationships. Journal of Marketing, 61(2), 35–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299706100203

- Fairhurst, A. E., & Fiorito, S. S. (1990). Retail buyers’ decision-making process: An investigation of contributing variables. The International Review of Retail, Distribution & Consumer Research, 1(1), 87–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593969000000007

- Faul, F. Erdfelder, E. Buchner, A. & Lang, A. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

- Frazier, G. L., Gill, J. D., & Kale, S. H. (1989). Dealer dependence levels and reciprocal actions in a channel of distribution in a developing country. Journal of Marketing, 53(1), 50–69. https://doi.org/10.2307/1251524

- Gallear, D., Ghobadian, A., Qile, H., Kumar, V., & Hitt, M. (2022). Relationship between routines of supplier selection and evaluation, risk perception and propensity to form buyer-supplier partnerships. Production Planning & Control, 33(14), 1399–1415. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2021.1872811

- Ganesan, S. 1994). Determinants of long-term orientation in buyer-seller relationships. Journal of Marketing, 58(2), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.2307/1252265

- Gaski, J. F. (1986). Interrelations among a channel Entity's power sources: Impact of the exercise of reward and coercion on expert, referent, and legitimate power sources. Journal of Marketing Research, 23(1), 62–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378602300107

- Gefen, D., Straub, D. & Boudreau, M.-C. (2000). Structural equation modeling and regression: Guidelines for research practice. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 4(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.17705/1CAIS.00407

- Gelderman, C. J., & Van Weele, A. J. (2004). “Determinants of dependence in dyadic buyer-supplier relationships.” Paper presented at the 13th International IPSERA Conference, Catania, Italy.

- Geyskens, I., & Steenkamp, J.-B. E. (2000). Economic and social satisfaction: Measurement and relevance to marketing channel relationships. Journal of Retailing, 76(1), 11–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4359(99)00021-4

- Geyskens, I., Steenkamp, J.-B. E. & Kumar, N. (1999). A meta-analysis of satisfaction in marketing channel relationships. Journal of Marketing Research, 36(2), 223–238. https://doi.org/10.2307/3152095

- Hansen, K. (2001). Purchasing decision behaviour by Chinese supermarkets. The International Review of Retail, Distribution & Consumer Research, 11(2), 159–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/713770585

- Hansen, T. H., & Skytte, H. (1998). Retailer buying behaviour: A review. The International Review of Retail, Distribution & Consumer Research, 8(3), 277–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/095939698342788

- Heide, J. B., & John, G. (1988). The role of dependence balancing in safeguarding transaction-specific assets in conventional channels. Journal of Marketing, 52(1), 20–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224298805200103

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 431, 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Izogo, E. E., & Jayawardhena, C. (2018). Online shopping experience in an emerging e-retailing market. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 12(2), 193–214. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIM-02-2017-0015

- Jap, S. P., & Ganesan, S. (2000). Control mechanisms and the relationship life cycle: Implications for safeguarding specific investments and developing commitment. Journal of Marketing Research, 37(2), 227–245. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.37.2.227.18735

- Kang, B. (2018). The effects of dependence and conflict on qualitative and quantitative organizational performances in partnership. Asia Marketing Journal, 20(2), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.15830/amj.2018.20.2.1

- Kannan, V. R., & Choon Tan, K. (2002). Supplier selection and assessment: Their impact on business performance. The Journal of Supply Chain Management, 38(3), 11–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-493X.2002.tb00139.x

- Kannan, V. R., & Choon Tan, K. (2003). Attitudes of US and European managers to supplier selection and assessment and implications for business performance. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 10(5), 472–489. https://doi.org/10.1108/14635770310495519

- Kannan, V. R., & Choon Tan, K. (2006). Buyer‐supplier relationships: The impact of supplier selection and buyer‐supplier engagement on relationship and firm performance. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 36(10), 755–775. https://doi.org/10.1108/09600030610714580

- Kant, R., & Vithalrao Dalvi, M. (2017). Development of questionnaire to assess the supplier evaluation criteria and supplier selection benefits. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 24(2), 359–383. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-12-2015-0124

- Kaushik, V., Kumar, A., Gupta, H., & Dixit, G. (2022). A hybrid decision model for supplier selection in online Fashion retail (OFR. International Journal of Logistics: Research & Applications, 25(1), 27–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/13675567.2020.1791810

- Kim, C., Miao, M., & Bin, H. (2022). Relations between merchandising information orientation, strategic integration and retail performance. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 50(1), 18–35. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-07-2020-0244

- Kim, C., & Takashima, K. (2018). The impact of retail buyer innovativeness on suppliers’ adaptive selling in Japanese buyer–supplier relationships. Journal of Marketing Channels, 25(4), 173–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/1046669X.2019.1658011

- Lai, C.-S. (2007). The effects of influence strategies on dealer satisfaction and performance in Taiwan’s motor industry. Industrial Marketing Management, 36(4), 518–527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2005.08.015

- Li, Z., Lu, Q., & Talebian, M. (2015). Online versus bricks-and-mortar retailing: A comparison of price, assortment and delivery time. International Journal of Production Research, 53(13), 3823–3835. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2014.973074

- Lin, P.-C., & Wu, L.-S. (2011). How supermarket chains in Taiwan select suppliers of fresh fruit and vegetables via direct purchasing. The Service Industries Journal, 31(8), 1237–1255. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642060903437568

- Liu, A., Zhang, Y., Hui, L., Tsai, S.-B., Hsu, C.-F., & Lee, C.-H. (2019). An innovative model to choose e-commerce suppliers. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Access, 7, 53956–53976. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2908393

- Lusch, R. F., & Brown, J. R. (1996). Interdependency, contracting, and relational behavior in marketing channels. Journal of Marketing, 60(4), 19–38. https://doi.org/10.2307/1251899

- Makhitha, K. M. (2017). Supplier selection criteria used by independent retailers in Johannesburg, South Africa. Journal of Business & Retail Management Research, 11 (3), 72–84. https://www.jbrmr.com/details&cid=274e.

- Matsuyama, Y. (2013). Hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) Gellman, Marc D., Rick Turner, J. In Encyclopedia of behavioral medicine (pp. 961–963. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1005-9_407

- Miyazaki, Y., & Maier, K. S. (2005). Johnson-Neyman type technique in hierarchical linear models. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 30(3), 233–259. https://doi.org/10.3102/10769986030003233

- Mohammed, A., de Sousa Jabbour, A. B. L., Koh, L., Hubbard, N., Jose Chiappetta Jabbour, C., & Al Ahmed, T. (2022). The sourcing decision-making process in the era of digitalization: A new quantitative methodology. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics & Transportation Review, 168, 102948. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tre.2022.102948

- Mohammed, A., Harris, I., & Govindan, K. (2019). A hybrid MCDM-FMOO approach for sustainable supplier selection and order allocation. International Journal of Production Economics, 217(), 171–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2019.02.003

- Mungra, Y., & Kumar Yadav, P. (2020). The mediating effect of satisfaction on trust-commitment and relational outcomes in manufacturer–supplier relationship. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 35(2), 219–230. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBIM-09-2018-0268

- Nair, A., Jayaram, J., & Das, A. (2015). Strategic purchasing participation, supplier selection, supplier evaluation and purchasing performance. International Journal of Production Research, 53(20), 6263–6278. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2015.1047983.

- Narasimhan, R., Talluri, S., & Mendez, D. (2001). Supplier evaluation and rationalization via data envelopment analysis: An empirical examination. The Journal of Supply Chain Management, 37(2), 28–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-493X.2001.tb00103.x

- Ngouapegne, C. N. M., & Chinomona, E. (2018). Antecedents of supply chain performance: A case of food retail industry. Journal of Economics and Behavioral Studies, 10(3 (J)), 23–36. https://doi.org/10.22610/jebs.v10i3.2313

- Okwu, M. O., & Tartibu, L. K. (2020). Sustainable supplier selection in the retail industry: A TOPSIS- and ANFIS-based evaluating methodology. International Journal of Engineering Business Management, 12(), 184797901989954. https://doi.org/10.1177/1847979019899542

- Ordoobadi, S. M. (2009). Development of a supplier selection model using fuzzy logic. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 14(4), 314–327. https://doi.org/10.1108/13598540910970144

- Pearson, J. N., & Ellram, L. M. (1995). Supplier selection and evaluation in small versus large electronics firms. Journal of Small Business Management, 33(4), 53–65. https://snu-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/f/enmgnl/TN_cdi_gale_incontextgauss_ISN_A17838921.

- Petersen, K. J., Handfield, R. B., & Ragatz, G. L. (2005). Supplier integration into new product development: Coordinating product, process and supply chain design. Journal of Operations Management, 23(3–4), 371–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2004.07.009

- Pickernell, D., Jones, P., Packham, G., Thomas, B., White, G., & Willis, R. (2013). E-commerce trading activity and the SME sector: An FSB perspective. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 20(4), 866–888. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-06-2012-0074

- Prahinski, C., & Benton, W. C. (2004). Supplier evaluations: Communication strategies to improve supplier performance. Journal of Operations Management, 22(1), 39–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2003.12.005

- Pratap, S., Daultani, Y., Dwivedi, A., & Zhou, F. (2022). Supplier selection and evaluation in e-commerce enterprises: A data envelopment analysis approach. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 29(1), 325–341. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-10-2020-0556

- Ramanathan, R., Ramanathan, U., & Hsiao, H.-L. (2012). On Taiwanese SMEs: Marketing and operations effects. International Journal of Production Economics, 140(2), 934–943. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2012.07.017

- Rong, L., Wang, L., & Liu, P. (2022). Supermarket fresh food suppliers evaluation and selection with multigranularity unbalanced hesitant fuzzy linguistic information based on prospect theory and evidential theory. International Journal of Intelligent Systems, 37(3), 1931–1971. https://doi.org/10.1002/int.22761

- Sarkar, R., & Das, S. (2017). Online shopping vs offline shopping: A comparative study. International Journal of Scientific Research in Science & Technology, 3(1), 424–431 .

- Sarkar, A., & Mohapatra, P. K. (2006). Evaluation of supplier capability and performance: A method for supply base reduction. Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management, 12(3), 148–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pursup.2006.08.003

- Sheth, J. N. (1980). A theory of merchandise buying behavior/BEBR no. 706. Faculty working papers-University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, College of Commerce and Business Administration; no. 706.

- Skytte, H., & Blunch, N. J. (2005). Buying behavior of Western European food retailers. Journal of Marketing Channels, 13(2), 99–129. https://doi.org/10.1300/J049v13n02_06

- StataCorp. (2021). Stata statistical software: Release 17. College station. StataCorp LLC. https://www.stata.com/

- Tsai, W. (2001). Knowledge transfer in intraorganizational networks: Effects of network position and absorptive capacity on business unit innovation and performance. Academy of Management Journal, 44(5), 996–1004. https://doi.org/10.5465/3069443

- Van Everdingen, Y. M., Laurens, M., Erjen van Nierop, S., & Verhoef, P. C. (2011). Towards a further understanding of the antecedents of retailer new product adoption. Journal of Retailing, 87(4), 579–597. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2011.09.003

- Villena, V. H., Revilla, E., & Choi, T. Y. (2011). The dark side of buyer–supplier relationships: A social capital perspective. Journal of Operations Management, 29(6), 561–576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2010.09.001

- Wilson, D. F. (2000). Why divide consumer and organizational buyer behaviour? European Journal of Marketing, 34(7), 780–796. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560010331207

- Wong, A., & Zhou, L. (2006). Determinants and outcomes of relationship quality: A conceptual model and empirical investigation. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 18(3), 81–105. https://doi.org/10.1300/J046v18n03_05

- Xie, E., Peng, M. W., & Zhao, W. (2013). Uncertainties, resources, and supplier selection in an emerging economy. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 30 (4) , 1219–1242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-012-9321-9