?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This paper examines the dynamics of the entrepreneurship ecosystem and entrepreneurship development in Africa. This study is conceived on the premise that although enterprise-induced growth is documented to be the panacea for containing the rising unemployment, poverty rate, and worsening economic conditions, African enterprise-led policies have not generated the desired results with entrepreneurship development still slow. It is believed that the nature of entrepreneurial ecosystem might have contributed to poor entrepreneurship development, however, there is a paucity of evidence about this possible link. This paper is one of the foundational studies in the entrepreneurship literature that has applied quantitative analytical procedures to investigate how the dynamics of the entrepreneurial ecosystem influence entrepreneurship development in Africa. The paper operationalises the entrepreneurial ecosystem within the African context and investigates the short-run and long-run relationships between these proxies and entrepreneurship development in Africa. The paper employed the Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) to estimate the relationships and the Generalised Method of Moments (GMM) to validate the estimates. Annual data from 2000 to 2021 in 54 African countries were used for the study. This translated into 1184 observations in a 22-year data span. The paper revealed a positive consequence of the entrepreneurial ecosystem on entrepreneurship development in Africa in both the short-run and the long-run, however, the short-run estimates were not significant. It is concluded that the entrepreneurial ecosystem proxies: people (human capital), venture capital, infrastructure, system, and support are catalysts that drive entrepreneurship development in Africa in the long run. It is recommended that African enterprise-led policy should emphasise the entrepreneurial ecosystem that revolves around these constructs in order to develop an entrepreneurship culture and sustain the existing enterprises.

1. Introduction

Global economies have continued to struggle to contain rising unemployment, poverty rate, and worsening economic conditions (Atiase et al., Citation2018; Guisinger et al., Citation2018). In recent decades, the consequences of these cankers have been unbearable (Atiase et al., Citation2018; Fischer, Citation2000; Guisinger et al., Citation2018; Kukaj, Citation2018; Okun, Citation1962). The global COVID −19 pandemic which affected the environment and human well-being coupled with global economic policy uncertainties has eroded the rather slippery gains of government interventions (Irfan et al. (Citation2021). UNSD (Citation2020), revealed that the global total unemployment population has reached 220 million. UNSD report documented that regions such as the Caribbean, Latin America, Northern America, and Europe recorded a 2 percentage point increase in unemployment (UNSD, Citation2020).

Africa is considered one of the worst hit by the growing unemployment rate. For instance, a report by World Bank Report (2020) shows that African countries such as South Africa recorded an unemployment rate of 29.20%, Botswana standing at 24.90%, and Gabon at 20.40%. In response to these growing challenges, many countries have been pursuing economic growth-targeting policies with the belief that high economic growth would arrest the growing unemployment and reduce poverty (Fischer, Citation2000; Guisinger et al., Citation2018; Kukaj, Citation2018; Okun, Citation1962). Although some gains have been made with these interventions (Banda, Citation2016; Guisinger et al., Citation2018; Kukaj, Citation2018), emerging evidence has demonstrated that economic growth per se does not necessarily address growing unemployment challenges, poverty, and the worsening economic welfare (Atiase et al., Citation2018; Frederick et al., Citation2010; Osinubi, Citation2005), rather the inclusiveness of the constituents of economic growth. For instance, when economic growth is not inclusive but favours the privileged few, the problem of poverty, poor economic welfare, and even unemployment may persist (Khobai, Citation2018; Osinubi, Citation2005).

The emerging reality of addressing economic, poverty, and unemployment problems is enterprise-induced growth where the emphasis is placed on promoting venture creation and enterprise development (Balkienė & Jagminas, Citation2010; Frimpong & Wilson, Citation2013; Mason & Brown, Citation2014; Ozgen & Minsky, Citation2007; Warwick, Citation2013). It has been recognised and recommended globally that to win against the economic challenges, poverty, and rising unemployment policies should be directed at entrepreneurship development (Carreea & Thurika, Citation2002; Huang et al., Citation2021; Kansheba, Citation2020; Nwagu & Enofe, Citation2021; Quaidoo, Citation2018). Entrepreneurship development could affect all facets of an economy and significantly address unemployment, poverty, and other economic ill-health within an economy (Fields et al., Citation2012; Global Entrepreneurship; Monitor, Citation2017) and may even deepen the stock market (Queku et al., Citation2022).

Global Entrepreneurship Monitor report in 2017 provides that over 582 million people have entered the business environment to start and run their enterprises (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, Citation2017). The rising interest in venture creation is evident in almost all parts of the world including the Americas, Asia, and Europe in the last decades. For example, in the United Kingdom (UK), a total of 70,000 of these enterprises have employed about one million people and contributed about £24 billion to the economic growth (1.3% GDP) in 2016 (Huang et al., Citation2018). Similar to other regions, African countries have also targeted entrepreneurship development as a foundation for their growth agenda (Atiase et al., Citation2018; Oppong et al., Citation2014; Quaidoo, Citation2018).

2. Background of the study

Despite the enterprise-led policies in Africa, entrepreneurship development is slow, and integration of enterprise-led is still in its infancy in Africa (Ahmed et al., Citation2013; Naudé, Citation2010). Furthermore, the enterprises borne out of these policies are not robust enough to withstand business uncertainties, shocks, and turbulence making them susceptible to going-concern problems. For instance, the World Bank report (2022) shows that the Global COVID-19 pandemic collapsed 8.4% of enterprises in Africa and affected the general environment and the well-being of people (Irfan et al., Citation2021) making the situation alarming. Although governments have strived to improve sustainability through various interventions, enterprise sustainability has been a persistent challenge for Africa (Queku & Marfo, Citation2016; Sackey et al., Citation2013) and this might have affected economic viability in Africa (Ali et al., Citation2023). In response, studies have investigated this challenge with some focusing on the dynamics of entrepreneurship and entrepreneurship development (Atiase et al., Citation2018; de Bruin et al., Citation2017), others concentrating on the drivers of entrepreneurship development (Brownson, Citation2013; Economidou et al., Citation2018) and better still another stream has explored entrepreneurship and growth (Acs et al., Citation2018).

Emerging studies in entrepreneurship literature are focusing on the entrepreneurial ecosystem (Alvedalen & Boschma, Citation2017; Atiase et al., Citation2018; Audretsch et al., Citation2019). Although these emerging empirical studies on entrepreneurship ecosystem have improved the understanding of the dynamics of entrepreneurship ecosystem (Alvedalen & Boschma, Citation2017; Audretsch et al., Citation2019), exploring the consequence of such dynamics on entrepreneurship development is still in its infancy (Kansheba & Wald, Citation2020). Fang et al. (Citation2022) recognizes the important role of entrepreneurial ecosystem by emphasizing internet development. However, exploring direct relationship between entrepreneurial ecosystem (internet development) and entrepreneurship development was outside the scope of Fang et al. (Citation2022). A systematic review conducted by researchers in the entrepreneurship literature has revealed that the entrepreneurial ecosystem phenomenon is still undertheorized with most of the contributions limited to conceptual analysis and potential causal relations almost absent (Malecki, Citation2018; Nicotra et al., Citation2018). Kansheba and Wald (Citation2020) acknowledged that the few empirical studies emphasising entrepreneurial ecosystems have mainly followed case study analysis including a qualitative analytical framework.

African entrepreneurial ecosystems and development have been extensively studied (Jones et al., Citation2018). As part of a special issue on African entrepreneurship, Jones et al. (Citation2018) examined entrepreneurial education and ecosystems. This special issue published innovative and empirically robust findings on under-reported and growing African subjects such entrepreneurial behaviour, entrepreneurial education and ecosystems, and entrepreneurial growth and diversity (Cantner et al., Citation2020) presented a dynamic lifecycle model to understand entrepreneurial ecosystems and emphasise the role of these activities in sustaining the region where entrepreneurs and intrapreneurs live (Buratti et al., Citation2022) examined the evolutionary dynamics of entrepreneurial ecosystems, showing that intrapreneurial activities diminish as entrepreneurial activities rise. Ajide (Citation2020) also explored how financial inclusion affects entrepreneurship in selected African nations using World Bank Development Indicators and World Bank Entrepreneurship Survey data. Other recent studies have mostly focused on the nature and dynamics of the entrepreneurial ecosystem in Africa and conceptual works (Atiase et al., Citation2018; Fuller-Love & Akiode, Citation2020; Guerrero et al., Citation2021; Manya, Citation2020; Quaidoo, Citation2018) without the extended investigation of the relationship between these unique EE and entrepreneurship development (Kansheba, Citation2020; Nicotra et al., Citation2018). Thus, there is limited evidence about the causal relationship between the entrepreneurial ecosystem and entrepreneurship development. This paper, therefore, seeks to extend the literature by exploring the complex relationship between entrepreneurial ecosystem and entrepreneurship development dynamics within the African context.

The paucity of empirical evidence on how the entrepreneurial ecosystem influences entrepreneurship development makes it difficult to identify the elements of the entrepreneurial ecosystem which are fundamental not only in driving entrepreneurial culture but also in ensuring sustainability. It has been asserted that a sound EE is a critical success factor for entrepreneurial activity and development (Abor & Quartey, Citation2010; Atiase et al., Citation2018; Chahine et al., Citation2019; Frimpong & Wilson, Citation2013; Maroufkhani et al., Citation2018; Sperber & Linder, Citation2019). It is, therefore, not surprising that Huang et al. (Citation2021) recommended the need to develop an entrepreneurial culture and explore how the entrepreneurial ecosystem, can drive entrepreneurship development.

This study follows the quantitative approach of Kansheba (Citation2020) who extended the literature by investigating EE quality and productive entrepreneurship. Nevertheless, the present study departs from the analytical procedure of Kansheba who measured productive entrepreneurship from “Total Early-stage Entrepreneurial Activities (TEA)”. An economy benefits from an enterprise-led policy when it deepens the number of enterprises borne out of the policy (Huang et al., Citation2018; World Bank, 2022), not only by early signals of entrepreneurial activities which are usually fragile and unsustainable. This paper, therefore, extends the early works such as Kansheba (Citation2020) by employing new venture creation as the proxy for entrepreneurship development.

The paper makes some significant contributions to the literature. First, it is one of the foundational studies in the entrepreneurship literature that has applied quantitative analytical procedures to investigate how the dynamics of the entrepreneurial ecosystem influence entrepreneurship development in Africa. The evidence from this paper demonstrates how the constituents of the entrepreneurial ecosystem could drive entrepreneurship in Africa. Secondly, despite the assertion that the entrepreneurial ecosystem shares some common characteristics, each setting including specific regions has unique development and implications. Thus, what works in a particular environment may not necessarily fit well in another environment. Efforts to realistically create and develop the entrepreneurial ecosystem are expected to be centred on the region’s or country’s existing resources. Therefore, focusing on the African scenario would provide evidence that works sympathetically for the African region. Thirdly, the study would explore both short and long-run relationships between entrepreneurial ecosystems and entrepreneurship development in Africa. The evidence could showcase whether or not the nature of the African-specific entrepreneurial ecosystem is a short or long-term driver of entrepreneurship development. This is critical because as documented in the literature, many of the enterprises in Africa flourish initially but become susceptible to waves of business turbulence (World Bank report, 2022). The findings could determine whether the entrepreneurial ecosystem emphasises venture creation or business sustainability.

3. Literature review and hypothesis development

This paper follows the assumptions of resource dependence theory (RDT) to situate the study within the theoretical context. RDT was developed by Pfeffer and Salancik (Citation1978). Pfeffer and Salancik (Citation1978) developed the RDT to explain the dynamics of external resources and their effect on the behaviour of organisations. The proponents of RDT argue that the success, continuity, and sustainability of an organization are dependent on how well it continuously negotiates with the environment and external surroundings for the needed resources (Granovetter & Action, Citation1985). Thus, the growth in new venture creations and the development of these firms are dependent on their ability to negotiate for and access the external resources relevant to their competitiveness, survivorship, and growth (Van Weele, Citation2018).

RDT may therefore be considered the organisational theory that explains organisational behaviour, the dynamics, and complexities in intra and inter-organisational relationships and the outworking of important resources that should be available and accessible for firms and enterprises to exist, survive and grow (Fubah & Moos, Citation2021; Johnson, Citation1995). In contributing to this, Kholmuminov et al. (Citation2019) opine that the RDT provides insight into how an enterprise’s external resources influence its behaviour. All forms of businesses rely on resources to survive and the said resources are produced or supplied by other firms or businesses. This diversity and complexity of relationships can be understood as patterns of interdependencies and constraints (Pfeffer, Citation1987, p. 40).

The implication is that the performance and development of enterprises are partly explained by the context within which the critical resources needed by organisations are provided or the environments which supply the critical resources of the organisations. Specifically, enterprises obtain and use critical resources for their development by adapting to the operational environment and the context, reducing uncertainties by minimising the reliance on externalities and enhancing its relevance by providing support to other enterprises (Kholmuminov et al., Citation2019; Seidu et al., Citation2022).

A critical consideration of the theoretical assumptions of RDT suggests that dependence on “critical and important resources” is foundational for the growth and development of enterprises. The theory also suggests that the ultimate business ecosystem that can serve as the catalyst for enterprise sustainability and development is one that creates the environment to achieve reasonable self-sufficiency and self-relevance. The theory assumes that to understand the behaviour of firms including their behaviour, growth, and even development, it is important to understand their context, environment, or ecology. The environment or the ecology of a firm may be defined as its ecosystem. Therefore, defining firms or organisations within the context of entrepreneurship implies that the behaviour of enterprises including their growth and development may be explained by their ecosystem (i.e. entrepreneurial ecosystem).

The entrepreneurial ecosystem is based on the concept of the notion of interactions between multiple interdependent actors and factors (Alvedalen & Boschma, Citation2017; Audretsch et al., Citation2019). It reflects the environment or the context within which enterprises emerge, interact, operate and develop as it is based on the concept of interactions between multiple interdependent actors and factors (Alvedalen & Boschma, Citation2017; Audretsch et al., Citation2019). As defined by Chowdhury et al. (Citation2019), an entrepreneurial ecosystem is a set of interconnected entrepreneurial actors which merge to connect, govern and mediate the performance within the local entrepreneurial environment. These factors or heterogeneous elements include government, financial institutions, higher education, support services, knowledge, and culture that support the development of a new venture and contribute to entrepreneurship development (Hechavarría & Ingram, Citation2019; Queku, Citation2023; Stam, Citation2015). This means that the entrepreneurial ecosystem is also resource-induced, an assumption that is central to RDT. Therefore, a possible link between an entrepreneurial ecosystem and entrepreneurship development is grounded in resource dependence theory. Resource Dependence Theory (RDT) opines that organisations and institutions including entrepreneurship thrive on resources for survival, growth, and development (Johnson, Citation1995).

The multidimensionality characteristics of the entrepreneurial ecosystem including funding (capital), human capital (people), infrastructure, system, and technology are resourced based which defined the entrepreneurial context and the environment. Thus, even though the proponents of the RDT did not test the causal relationship between environment or context and organisational success, behaviour, or development, the foundational assumption of the behavioural change arising from the environment and context suggests such a relationship. Moreover, the existing literature recognises environmental inducement in attitude (Asif et al., Citation2023; Sobotie & Queku, Citation2018), which may include entrepreneurs. This implies that following the assumptions of RDT, it can be posited that the entrepreneurial ecosystem could have a significant effect on entrepreneurship development.

These theoretical relationships are also supported by some empirical assertions even though the causal relationship has not been well investigated in the literature. For instance, it has been asserted that a sound entrepreneurial ecosystem is a critical success factor for entrepreneurial activity and development (Abor & Quartey, Citation2010; Atiase et al., Citation2018; Chahine et al., Citation2019; Frimpong & Wilson, Citation2013; Maroufkhani et al., Citation2018; Sperber & Linder, Citation2019). It is, therefore, not surprising that Huang et al. (Citation2021) recommended the need to explore and develop an entrepreneurial culture and ecosystem and determine how it can drive entrepreneurship development. Following these theoretical and empirical lessons, this paper posits that the entrepreneurial ecosystem could have a significant influence on entrepreneurship development and therefore formulates a working hypothesis as follows:

H1a:

Entrepreneurial ecosystem has a significant relationship with entrepreneurship development in Africa

4. Analytical framework and design

This paper employs a quantitative analytical framework and explanatory design. This quantitative approach and the explanatory design complement each other. Moreover, all the constructs used in this paper require numerical data for their measurements These are fundamental characteristics of the quantitative analytical framework (Cohen et al., Citation2011; Johnson & Christensen, Citation2012). Both the quantitative approach and the explanatory design permit the test of cause and effect relationships and they draw theoretical assumptions and empirical assertions to develop and test hypotheses (Bryman, Citation2012). To apply the quantitative approach and explanatory design strategy, the paper operationalises the variables and follows the existing literature to select proxies and collect secondary data to measure the variables. The causal relationship proposed in this paper is translated into a model and estimated through an appropriate estimation approach.

5. Sources and description of data

The paper uses secondary data to measure the key variables: entrepreneurship ecosystem, and entrepreneurship development (Andrews et al., Citation2012; Schutt, Citation2011; Smith, Citation2008; Smith et al., Citation2011). The data are sourced from the Global Economy Indicator (TGEI); and the World Bank’s database (WBDI). These databases are credible and widely used (Atiase et al., Citation2018; Ionescu et al., Citation2020; Yan & Guan, Citation2019). Following the literature, entrepreneurship development is measured using the average new venture creation or formation (Ahmad & Hoffman, Citation2007; Iversen et al., Citation2007) while the entrepreneurial ecosystem is measured using multiple proxies and it is considered a multidimensional variable (Chahine et al., Citation2019; Manya, Citation2020; Pita et al., Citation2021).

The paper uses data spanning from 2000 to 2021 for all African countries that have relevant data within the time frame. The paper also introduces some control variables in addition to the variables of interest to check possible spurious estimates. It is expected that enterprises will thrive and develop under a strong rule of law (ROL), sound political stability (PS), and good governance (Gov). These variables are introduced into the model specifications as control variables. Table summarises the data sources and their measurement.

Table 1. Summary of variables and measurements

6. Model specifications

This paper follows the general panel model to test the relationship between the entrepreneurial ecosystem, and entrepreneurship development. The panel model combines the characteristics of both time series (longitudinal) and cross-sectional data for robust analyses with less collinearity problem and more degrees of freedom (Fu, Citation2007; Greene, Citation2008; Torres-Reyna, Citation2007; Wooldridge, Citation2006). The generalised model is specified as:

Where:

“i” and “t” are the cross-sectional and the time-series (longitudinal) dimensions respectively

“Y” is the outcome or the dependent variable.

“X” is the vector of the independent variables and the controls.

“a” is the intercept or the constant

“β”1 are the coefficients from the model

“e” is the error term.

The generalised model specified in Eqn (1) is operationalised into the empirical model by substituting the relevant variables (Seidu et al., Citation2021; Waiyaki, Citation2013). The model is expressed in Eqn (2) as follows:

Where:

ED is the entrepreneurship development and represents the dependent variable

Cap, Pp, SS, and InF are capital, people, system and support, and infrastructure respectively. They are collectively the proxies of the entrepreneurial ecosystem (EE) and the independent variables.

ROL, Gov, and PS are the rule of law, governance, and political stability respectively. These are the vectors of controls

ɛ is the error term

β1, β2 … … … β7 are the sensitivities of entrepreneurship development (ED) to the independent and the control variables. The nature and the direction of the relationships between ED and the respective variables are determined by β1, β2 … … … β7. The paper expects the EE variables (Cap, Pp, SS, and InF) and the control variables (ROL, PS, and Gov) to exhibit a positive effect on entrepreneurship development.

β1, β2, β3, β4, β5, β6, and β7 >0

7. Estimation approach

The paper employs the Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) to estimate Eqn(2). ARDL was developed by Pesaran & Pesaran (Citation1997), Pesaran & Shin (Citation1999). This estimator provides both long-run and short-run estimates. The time series dimension of the panel makes it prone to stationarity problems. The traditional approach such as Engle-Granger, Ordinary Least Squares (OLS), and Johansen approach provide unreliable estimates when there is a unit root problem. However, ARDL is capable of generating valid results even when the series have unit root problems and appropriate when the series have mixed stationarity properties (i.e. I(0) and I(1) variables) (Pesaran et al., Citation2001). It is important to acknowledge that ARDL is inconsistent with I(2) variables.

This estimation technique can estimate simultaneously the short and long-run dynamics between the entrepreneurial ecosystem and entrepreneurship development. With the ARDL, a different optimal number of lags can be assigned to different variables, thus allowing for flexibility. The ARDL estimation is expressed as:

Where

The specifications with are the short-run dynamics whiles the second part of the specifications shows the cointegration

et is the white noise error term and t-1 denotes the lags.

The rest of the variables remain as already described

8. Descriptive analyses

Table captures the descriptive properties of both the variables of interest and the control variables. The mean statistics for entrepreneurship development is 12,504. This suggests that on average, each African country establishes 12,504 new enterprises annually. Although this is relatively high, the individual countries’ observations are highly dispersed as evident in the high coefficient of variation of about 370% (3.6987). Additionally, while some countries are developing enterprises with an annual score of 564,264, others are scoring 15. This is quite troubling especially since the economy is driven by these enterprises (Atiase et al., Citation2018, Oppong et al., Citation2014; Quaidoo, Citation2018). This corroborates the slow entrepreneurship development observed by some researchers in Africa (Ahmed et al., Citation2013; Naudé, Citation2010).

Table 2. Descriptive statistics

The mean score for entrepreneurial ecosystem (EE) proxies: people (ability to retain talents), venture capital availability, system and support (ease of doing business) and infrastructure (the individual using the internet) are 3.5572, 22.9259, 13.2227 and 9.6774 respectively. Other than the infrastructure which has very high volatility, the rest of the proxies for the entrepreneurial ecosystem are relatively stable. The mean scores imply that African countries have serious weakness in retaining talent as less than 50% of talents are retained, the venture capital growth is also poor as some are reporting negative, businesses go through several procedural bureaucracies for doing business and infrastructures to provide fertile grounds for businesses to spring out are also weak. In effect, the entrepreneurial ecosystem in Africa is poor. Table also reports the descriptive statistics of the control variables where all of them: governance (gov), rule of law (rol) and political stability (ps) are negative. This is not surprising as Africa is known as one of the regions with weak governance, rule of law and political stability. Nevertheless, these control scores are closer to zero than the −2.5 making them relatively good.

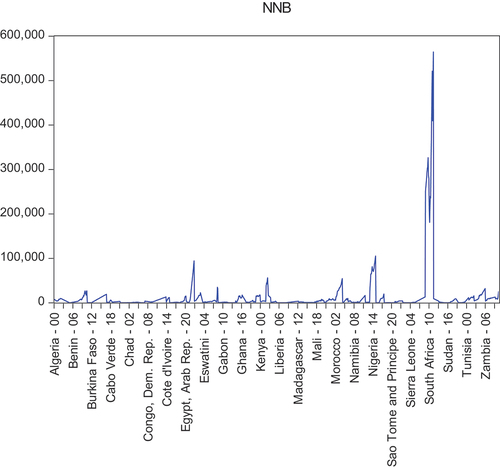

9. Trend analyses of entrepreneurship development in Africa

Figure presents a visual view of the trend in entrepreneurship development in Africa. It can be observed that at the country level generally, entrepreneurship development is smoothening as year-on-year variations are not significant. However, at the regional or African level, it is observable that while some countries exhibit high entrepreneurship culture others are behind. Specifically, countries such as South Africa, Nigeria, Egypt, Morocco and Kenya are exhibiting relatively high entrepreneurship development within the period of the investigation while others are still lagging.

10. Correlation analyses

The paper conducts pre-diagnostic on the data of the variables in the model specified for the investigation. Since the specifications use several independent and control variables, there is the possibility of a multicollinearity problem which could adversely affect the stability of the estimates. A correlation matrix among the independent and control variables is used to check the multicollinearity. The results are presented in Table . The results in Table show that there is no multicollinearity problem as all the correlation coefficients between the variables are less than 0.8 (Salmeron-Gomez et al., Citation2020; Vani, Citation2021).

Table 3. Correlation matrix of the independent and control variables

11. Panel unit root

The appropriateness of an econometric model and its specifications are influenced by the way the variables have been integrated. Therefore, the correct order of integration must always be known and through unit root tests these can be determined (Herranz, Citation2017). This is critical as the estimation approach employed in this paper (ARDL) though capable of handling non-stationarity or mixed order of integrations, the estimates become unstable if any of the variables id I(2).

The paper employs the Fisher-Augmented Dickey-Fuller model, the Philip and Perron test model and the Levin, Lin and Chu unit root (Choi, Citation2001; Levin et al., Citation2002; Maddala & Wu, Citation1999) to determine the stationarity of the variables. The paper conducts this analysis as a prerequisite for ARDL estimation. The Fisher ADF and PP are the primary unit root tests, however, where there are contradictory results, the study follows Lin and Chu (LLC) to make the choice. The results are captured in Table . Since none of the series is I(2), the study continues to use the proposed Autoregressive distribution lag (ARDL) to run the cointegration test. Prior to conducting the ARDL, lag length is determined from the lag structure. The lag length affects the nature of ARDL output. The study uses a lag length of 2. The output of the ARDL is also used to test the serial independent assumption under the ARDL.

Table 4. Summary of group unit root results

12. Empirical results

With consistent diagnostic results, the paper proceeds to estimate the long-run and short-run between entrepreneurship development and the entrepreneurial ecosystem using the ARDL approach. For robustness checks and stability of the estimates, the ARDL results are reported along with the GMM results. The details are in Table . The first column of the table captures the variables, the second column reports the results of the main estimator (ARDL) and the third column presents the estimates of the robustness check through GMM. Two values are reported in each of the ARDL and GMM columns. The values in the parentheses are the t-statistics and those outside the parentheses are the coefficients. The level of significance of these coefficients is denoted *, ** and *** for 10%, 5% and 1% significance respectively.

Table 5. Panel analyses of ED and EE relationships

The estimates generated from the ARDL are similar to the GMM results. Other than venture capital, all the indicators are similar in both significance and direction. This suggests that the estimates from the ARDL are robust. It can be observed that all the entrepreneurial ecosystem variables exhibited a positive effect on entrepreneurship development in both the short and long run. However, none of the short-run estimates is significant. This suggests that the study fails to reject the null hypothesis that the proxies of the entrepreneurial ecosystem do not have a significant effect on entrepreneurship development.

Regarding the long-run estimates, all the proxies exhibited significant positive effects on entrepreneurship development. The coefficients for Pp, Cap, SS and InF are 2.1120, 1.8334, 0.3051 and 0.2805 respectively. This means that an increase in the retention rate of talent (human capital) in Africa would lead to a 2.1120 increase in entrepreneurship development in Africa, all other things being equal. The implication is that managing African talents with emphasis placed on retention is one of the fundamental mechanisms to improve entrepreneurship development in Africa. Thus, African talent retention is an important element of EE that drives entrepreneurship development.

Capital availability (venture capital) has a coefficient of 1.8334 which is also significant at 1% suggesting that an increase in capital available for entrepreneurship could lead to an increase in entrepreneurship development by 1.8334 and vice-versa, holding other factors constant. This demonstrates the fundamental role of capital as an important driver of entrepreneurship development in Africa. It can also be seen that system and support exhibit a coefficient of 0.3051 which is also significant at 1%. Thus, improving support and system to enhance the ease of doing business is critical for entrepreneurship development in Africa. The coefficient for infrastructure is also positive and significant. This means that infrastructure such as individual usage of the internet is needed to improve entrepreneurship in Africa. For brevity, these control variables are not discussed.

13. Discussions and implications

The findings in the long-run model significant effect of the entrepreneurial ecosystem constructs on entrepreneurship development in Africa. The findings indicate that all of the constructs of EE have a positive significant influence on entrepreneurship development in the long-run. This suggests that people, capital, system and support, and infrastructure are the fundamental antecedents and drivers of entrepreneurship development in Africa. The results are inconsistent with similar studies such as Kansheba (Citation2020). The differences in the empirical results may be attributed to the choice of proxies as explained earlier.

Nevertheless, the findings imply that EE needed to drive venture creation in Africa should reflect the environment or the context within which enterprises emerge (system, support and infrastructure), interact and operate (people and capital) and ultimately provide the windows for development. The findings affirm conclusions reached in some studies in Africa and developing economies (Fuller-Love & Akiode, Citation2020; Guerrero et al., Citation2021). Although Fuller-Love and Akiode (Citation2020) did not conduct cause and effect analyses, their study reach a similar conclusion that factors such as capital, human capital, system and support are elements of EE that could drive entrepreneurship development.

The findings have provided inferential evidence to support some of the earlier studies that a sound EE is a critical success factor for entrepreneurial activity and development (Abor and Quartey, Citation2010; Atiase et al., Citation2018; Chahine et al., Citation2019; Frimpong & Wilson, Citation2013; Maroufkhani et al., Citation2018; Sperber & Linder, Citation2019). The results also corroborate some earlier evidence that the entrepreneurial ecosystem to drive entrepreneurship is multifaceted and interdependent actors and factors (see Alvedalen & Boschma, Citation2017; Audretsch et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, the findings show that in the short-run although the effect of the EE factors is positive, they are insignificant. This reflects Africa’s environment where it takes a considerable length of time for new entrants (potential entrepreneurs) to access capital (venture capital), and attract and retain talents (human capital). Thus, it is not surprising that the time-varying effect has implications on the entrepreneurial ecosystem-entrepreneurship development nexus.

Theoretically, the findings demonstrate that the entrepreneurial ecosystem that drives entrepreneurship development in Africa is resource-induced. This is evident by the fact that all the four elements or interconnected proxies used as the proxies for the entrepreneurship ecosystem are resource-led. Thus, the findings are consistent with the resource dependence theory (RDT). The results have shown that entrepreneurship development is dependent on how well externalities and needed resources such as people, capital, infrastructure, system and support influence the businesses’ ability to negotiate well with these externalities for these resources (Granovetter & Action, Citation1985; Van Weele, Citation2018). Further implication is that the entrepreneurial ecosystem factors (people, capital, infrastructure, system and support) are not only “critical and important resources” but also foundational for the growth and development of enterprises in Africa.

One fundamental policy implication of the findings stem from significant positive effect of human capital on new venture creation. This evidence implies that existing, new and potential enterprises require people strategy to attract and retain talents (human capital) for their continuity and development. Nevertheless, the critical role of human capital evident in the results also underscore the need for government intervention. The efforts to stimulate entrepreneurship development and continuity of enterprises cannot be to firm specific interventions. It requires top-tier government efforts to create opportunities to complement firm specific strategies to attract and retain talents to grease environment not only for existing high growth firms but also for new ventures or start-up. Governments in Africa should check brain drain to nurture and retain talents. This policy implication is critical as people remain the strongest entrepreneurial ecosystem element that drives entrepreneurship development.

Moreover, the findings imply that entrepreneurship support funds, infrastructure, system and support are accelerators for entrepreneurship development and therefore active interventions are required. African governments’ enterprise-led policy should emphasis government role in removing barriers such as system and bureaucratic challenges for new venture creation and development, smoothening the ease of doing business and infrastructure so as to bridge the valley of failures of enterprise and grease the ease for new enterprises. Thus, government should be seen as supporter-oriented interventionists to position the elements of entrepreneurial ecosystem for creating entrepreneurship development culture.

14. Conclusions

This paper explores the dynamics of the relationship between the entrepreneurial ecosystem and entrepreneurship development within the African context. The several of the existing studies on entrepreneurial ecosystem and entrepreneurship mostly focused on the nature, conceptualisation and dynamics of the entrepreneurial ecosystem and entrepreneurship with limited evidence on the causal relationship between the entrepreneurial ecosystem and ED. This paper is one of the foundational studies in the entrepreneurship literature that has applied quantitative analytical procedures to investigate how the dynamics of the entrepreneurial ecosystem influence entrepreneurship development in Africa. The paper operationalises the entrepreneurial ecosystem within the African context and investigates the short-run and long-run relationships between these proxies and ED in Africa. The paper employed the Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) to estimate the relationships and the Generalised Method of Moments (GMM) to validate the estimates. Annual data from 2000 to 2021 in 54 African countries were used for the study.

The findings provide that entrepreneurial ecosystem factors: venture capital, human capital, infrastructure, system and support have positive significant influence on entrepreneurship development in the long-run but insignificant in the short-run. The evidence reflects the fact that in Africa these elements are scarce and restrained the development of new venture. Moreover, it takes a considerable length of time for new entrants (potential entrepreneurs) to access capital (venture capital), and attract and retain talents (human capital). This might have contributed to the differences in the short-run and long-run results.

15. Recommendations

The findings show that the nature of the African-specific entrepreneurial ecosystem is a long-term driver of entrepreneurship development. This echoes differential effect on stages of development. It is therefore recommended that African governments and other entrepreneurship institutions should reshape the enterprise-led policy to emphasise interventions according to the stages of development of African enterprises.

Firms and entrepreneurs should develop policies not only to attract but also to retain talents for development and sustainability as human capital is evident in this study as a fundamental drive of entrepreneurship development.

Governments should also check talent flight or brain drain so as to keep Africa’s talent to support enterprise development.

It is further recommended that African governments’ enterprise-led policy should emphasise the government’s role in removing barriers such as system and bureaucratic challenges for new venture creation and development, smoothening the ease of doing business and infrastructure so as to bridge the valley of failures of enterprise and grease the ease for new enterprises.

16. Limitations and suggestions for future studies

This paper focused on the dynamics of the entrepreneurial ecosystem and entire entrepreneurship development with the assumption that this could shape Africa’s enterprise-led policy to curb unemployment, poverty and economic welfare. However, it is possible that the stages of enterprise development could influence its response or how it negotiates with the entrepreneurial ecosystem. Therefore, future studies could investigate this by exploring the entrepreneurial ecosystem and entrepreneurship development nexus along the stages of enterprise development. This could reveal whether or not all enterprises would require different enterprise-led policies and interventions. Moreover, this study also assumes that all enterprises contribute significantly to addressing the unemployment, poverty and economic welfare problems. However, the nature of the growth dynamics of an enterprise may rather define its significant contribution to addressing the economic challenges not the number of enterprises in an economy. Future researchers could also integrate this in their analyses in Africa to provide evidence on whether or not to pursue a focus or generic enterprise-led policy. This paper and its evidence follow the premises that African countries have similar economic structures, development and entrepreneurial dynamics. Although this assumption is sounding and echoes the fact that African countries share common entrepreneurial ecosystems, there could still be country-specific inducement which may affect the structure of the ecosystem. This could make the evidence in this paper more generic rather than individualistic which may be needed to develop a more sympathetic policy and intervention for a particular setting.

Finally, the field of entrepreneurship is expanding, necessitating a multifaceted approach to better comprehend this phenomenon and ensure its development. While this study has addressed a limited aspect of entrepreneurship, future research should prioritize exploring servant leadership concepts and social networks. Existing studies (Ruiz-Palomino & Martínez-Cañas, Citation2021; Ruiz-Palomino et al., Citation2021) have primarily focused on the developed world. Therefore, there is a need to examine how servant leadership operates in other contexts, such as Africa. Additionally, connecting servant leadership and social networks to theories like KSTE and RDT could further enrich our understanding.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS.docx

Download MS Word (12.3 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2292315

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Alhaji Abdulai

Alhaji Abdulai is a PhD. Scholar at B.S. Abdur Rahman Crescent Institute of Science and Technology, Chennai and a lecturer at Cape Coast Technical University. His teaching and research activity is in the field of family business, microfinance, strategy and entrepreneurial learning and knowledge transfer.

References

- Abor, J., & Quartey, P.(2010). Issues in SME development in Ghana and South Africa. International Research Journal of Finance and Economics, 39(6), 215–17.

- Acs, Z. J., Estrin, S., Mickiewicz, T., & Szerb, L.(2018). Entrepreneurship, institutional economics, and economic growth: An ecosystem perspective. Small Business Economics, 51(2), 501–514.

- Ahmad, N., & Hoffman, A. (2007). A framework for addressing and measuring entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Indicators Steering Group.

- Ahmed, A., Nwankwo, S., & Ahmed, A. (2013). Entrepreneurship development in Africa: an overview. World Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development, 9(2/3), 82–86. https://doi.org/10.1108/WJEMSD-06-2013-0033

- Ajide, F. (2020). Financial inclusion in Africa: does it promote entrepreneurship? Journal of Financial Economic Policy, 12(4), 687–706. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFEP-08-2019-0159

- Ali, S., Yan, Q., Dilanchiev, A., Irfan, M., & Fahad, S. (2023). Modeling the economic viability and performance of solar home systems: A roadmap towards clean energy for environmental sustainability. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30(11), 30612–30631. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-24387-6

- Alvedalen, J., & Boschma, R. (2017). A critical review of entrepreneurial ecosystems research: Towards a future research agenda. European Planning Studies, 25(6), 887–903. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2017.1299694

- Andrews, L., Higgins, A., Andrews, M. W., & Lalor, J. G.(2012). Classic grounded theory to analyse secondary data: Reality and reflections. Grounded Theory Review, 11(1).

- Asif, M. H., Zhongfu, T., Irfan, M., & Işık, C. (2023). Do environmental knowledge and green trust matter for purchase intention of eco-friendly home appliances? An application of extended theory of planned behavior. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30(13), 37762–37774. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-24899-1

- Atiase, V. Y., Mahmood, S., Wang, Y., & Botchie, D. (2018). Developing entrepreneurship in Africa: Investigating critical resource challenges. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 25(4), 644–666. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-03-2017-0084

- Audretsch, D. B., Cunningham, J. A., Kuratko, D. F., Lehmann, E. E., & Menter, M. (2019). Entrepreneurial ecosystems: economic, technological, and societal impacts. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 44(2), 313–325. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-018-9690-4

- Balkienė, K., & Jagminas, J. (2010). Up-to-date awareness of entrepreneurship policy: focus on innovation. Public Policy and Administration, 10(4), 501–521.

- Banda, L. G. (2016). Good governance and human welfare development in Malawi: An ARDL approach. Malawi Journal of Social Sciences (MJSS), 22(1), 88–119. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4235681

- Brownson, C. D. (2013). Fostering entrepreneurial culture: A conceptualization. European Journal of Business and Management, 5(31), 146–155.

- Bryman, A.(2012). Social Research Methods. Oxford University Press.

- Buratti, M., Cantner, U., Cunningham, J., Lehmann, E., & Menter, M. (2022). The dynamics of entrepreneurial ecosystems: An empirical investigation. R and D Management, 53(4), 656–674. https://doi.org/10.1111/radm.12565

- Cantner, U., Cunningham, J., Lehmann, E., & Menter, M. (2020). Entrepreneurial ecosystems: a dynamic lifecycle model. Small Business Economics, 57(1), 407–423. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00316-0

- Carreea, M., & Thurika, A. (2002). The Impact of entrepreneurship on economic growth. Entrepreneurship Research.

- Chahine, S., Fang, Y., Hasan, I., & Mazboudi, M. (2019). Entrenchment through corporate social responsibility: Evidence from CEO network centrality. International Review of Financial Analysis, 66, 101347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2019.04.010

- Choi, I.(2001). Unit root tests for panel data. Journal of International Money & Finance, 20(2), 249–272.

- Chowdhury, F., Audretsch, D. B., & Belitski, M. (2019). Institutions and entrepreneurship quality. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 43(1), 51–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258718780431

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K.(2011). Research methods in education. Routledge.

- de Bruin, A., Shaw, E., & Lewis, K. V. (2017). The collaborative dynamic in social entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 29(7–8), 575–585. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2017.1328902

- Economidou, C., Grilli, L., Henrekson, M., & Sanders, M. (2018). Financial and institutional reforms for an entrepreneurial society. Small Business Economics, 51(2), 279–291. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0001-0

- Fang, Z., Razzaq, A., Mohsin, M., & Irfan, M. (2022). Spatial spillovers and threshold effects of internet development and entrepreneurship on green innovation efficiency in China. Technology in Society, 68, 101844. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101844

- Fields, L. P., Fraser, D. R., & Subrahmanyam, A. (2012). Board quality and the cost of debt capital: The case of bank loans. Journal of Banking & Finance, 36(5), 1536–1547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2011.12.016

- Fischer, F. (2000). Citizens, experts, and the environment. In Citizens, experts, and the environment. Duke University Press.

- Frederick, M. M., Machuma, A. H., & Nafukho, F. (2010). ‘Entrepreneurship and socioeconomic development in Africa: A reality or myth? Journal of European Industrial Training, 34(2), 96–109. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090591011023961

- Frimpong, K., & Wilson, A. (2013). Relative importance of satisfaction dimensions on service performance: A developing country context. Journal of Service Management, 24(4), 401–419. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-07-2012-0151

- Fu, M. C. (2007). Variance-Gamma and Monte Carlo. In M. C. Fu, R. A. Jarrow, J. J. Yen, & R. J. Elliott (Eds.), Advances in Mathematical Finance. Applied and Numerical Harmonic Analysis. Birkhäuser Boston.

- Fubah, C. N., & Moos, M. (2021). Relevant theories in entrepreneurial ecosystems research: An overview. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 27(6), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/1091367X.2021.1979073

- Fuller-Love, N., & Akiode, M. (2020). Transnational Entrepreneurs Dynamics in Entrepreneurial Ecosystems: A Critical Review. Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation in Emerging Economies, 6(1), 41–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/2393957519881921

- Granovetter, M., & Action, E. (1985). The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology, 91(3), 481–510. https://doi.org/10.1086/228311

- Greene, W. H.(2008). The econometric approach to efficiency analysis. The Measurement of Productive Efficiency and Productivity Growth, 1(1), 92–250.

- Guerrero, M., Liñán, F., & Cáceres-Carrasco, F. R. (2021). The influence of ecosystems on the entrepreneurship process: A comparison across developed and developing economies. Small Business Economics, 57(4), 1733–1759. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00392-2

- Guisinger, A. Y., Hernandez-Murillo, R., Owyang, M. T., & Sinclair, T. M. (2018). A state-level analysis of Okun’s law. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 68, 239–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2017.11.005

- Hechavarría, D. M., & Ingram, A. E. (2019). Entrepreneurial ecosystem conditions and gendered national-level entrepreneurial activity: A 14-year panel study of GEM. Small Business Economics, 53(2), 431–458. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-9994-7

- Herranz, G.(2017). Diagnosis and quantification of the non-essential collinearity. Computational Statistics, 35(2), 647–666. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00180-019-00922-x

- Huang, M. H., Donner, M., & Maksimovic, V. (2018). The feeling economy: Managing in the next generation of artificial intelligence (AI). California Management Review, 61(4), 43–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008125619863436

- Huang, Y., Lin, R., & Chen, X. (2021). An enhancement EDAS method based on prospect theory. Technological and Economic Development of Economy, 27(5), 1019–1038. https://doi.org/10.3846/tede.2021.15038

- Ionescu, A. M., Popescu, C. A., & Popescu, G. H.(2020). The impact of digitalization on the accounting profession: A literature review. Journal of Accounting and Management Information Systems, 19(4), 573–601. https://doi.org/10.24818/jamis.2020.04002

- Irfan, M., Ikram, M., Ahmad, M., Wu, H., & Hao, Y. (2021). Does temperature matter for COVID-19 transmissibility? Evidence across Pakistani provinces. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 28(42), 59705–59719. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-14875-6

- Iversen, J., Jørgensen, R., & Malchow-Møller, N. (2007). Defining and measuring entrepreneurship. Foundations and Trends® in Entrepreneurship, 4(1), 1–63. https://doi.org/10.1561/0300000020

- Johnson, S. R. (1995). Fog, fairness, and the federal fisc: Tenancy-by-the-entireties interests and the federal tax Lien. Missouri Law Review, 60(3), 839. https://doi.org/10.2307/1123066

- Johnson, R. B., & Christensen, L.(2012). Educational research: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed approaches. SAGE Publications.

- Jones, P., Maas, G., Dobson, S., Newbery, R., Agyapong, D., & Matlay, H. (2018). Entrepreneurship in Africa, part 2: entrepreneurial education and eco-systems. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 25(4), 550–553. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-08-2018-400

- Kansheba, J. M. P. (2020). Small business and entrepreneurship in Africa: the nexus of entrepreneurial ecosystems and productive entrepreneurship. Small Enterprise Research, 27(2), 110–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/13215906.2020.1761869

- Kansheba, J. M. P., & Wald, A. E. (2020). Entrepreneurial ecosystems: A systematic literature review and research agenda. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development.

- Kansheba, J. M. P., & Wald, A. E.(2020). Entrepreneurial ecosystems: A systematic literature review and research agenda. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development.

- Khobai, H. (2018). Electricity consumption and economic growth: A panel data approach for Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa countries. International Journal of Energy Economics & Policy, 8(3), 283.

- Kholmuminov, S., Kholmuminov, S., & Wright, R. E. (2019). Resource dependence theory analysis of higher education institutions in Uzbekistan. Higher Education, 77(1), 59–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-018-0261-2

- Kukaj, D. (2018). Impact of unemployment on economic growth: Evidence from Western Balkans. European Journal of Marketing and Economics, 1(1), 10–18. https://doi.org/10.26417/ejme.v1i1.p10-18

- Levin, A. Lin, C. F. & Chu, C. S. J.(2002). Unit root tests in panel data: Asymptotic and finite-sample properties. Journal of Econometrics, 108(1), 1–24.

- Maddala, G. S., & Wu, S.(1999). A comparative study of unit root tests with panel data and a new simple test. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 61(S1), 631–652.

- Malecki, E. J. (2018). Entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial ecosystems. Geography Compass, 12(3), e12359.

- Manya, V. O. (2020). Dynamics of a start-up ecosystem in Africa: A case study of Yabacon in Nigeria. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 27(6), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/1091367X.2021.1979073

- Maroufkhani, P., Wagner, R., & Wan Ismail, W. K. (2018). Entrepreneurial ecosystems: A systematic review. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 12(4), 545–564. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEC-03-2017-0025

- Mason, C., & Brown, R. (2014). Entrepreneurial ecosystems and growth-oriented entrepreneurship. Final Report to OECD, Paris, 30(1), 77–102.

- Monitor, G. E. (2017). Empreendedorismo no Brasil: 2016. Curitiba: IBQP, 1–208.

- Naudé, W. (2010). Entrepreneurship, developing countries, and development economics: new approaches and insights. Small Business Economics, 34(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-009-9198-2

- Nicotra, M., Romano, M., Del Giudice, M., & Schillaci, C. E.(2018). The causal relation between entrepreneurial ecosystem and productive entrepreneurship: A measurement framework. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 43(3), 640–673.

- Nwagu, N. B., & Enofe, E. E. (2021). The impact of entrepreneurship on the economic growth of an economy: An overview. Journal of Emerging Trends in Economics and Management Sciences, 12(4), 143–149.

- Okun, A. M. (1962). The predictive value of surveys of business intentions. The American Economic Review, 52(2), 218–225.

- Oppong, M., Owiredu, A., & Churchill, R. Q.(2014). Micro and small scale enterprises development in Ghana. European Journal of Accounting Auditing & Finance Research, 2(6), 84–97.

- Osinubi, T. S. (2005). Macro econometric analysis of growth, unemployment and poverty in Nigeria. Pakistan Economic and Social Review, 43(2), 249–269. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25825276

- Ozgen, E., & Minsky, B. D. (2007). Opportunity recognition in rural entrepreneurship in developing countries. International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 11, 49. https://doi.org/10.1108/14626000710749457

- Pesaran, M. H., & Pesaran, B.(1997). Working with Microfit 4.0: Interactive Econometric Analysis. Oxford University Press.

- Pesaran, M. H., & Shin, Y.(1999). An autoregressive distributed lag modelling approach to cointegration analysis. In S. Strom (Ed.), Econometrics and Economic Theory in the 20th Century: The Ragnar Frisch Centennial Symposium. Cambridge University Press.

- Pesaran, M. H., Shin, Y., & Smith, R. J.(2001). Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 16(3), 289–326.

- Pfeffer, J.(1987). A resource dependence perspective on interorganizational relations. In M. S. Mizruchi & M. Schwartz (Eds.), Intercorporate relations: The structural analysis of business (pp. 25–55). Cambridge University Press.

- Pfeffer, J., & Salancik, G. R. (1978). A resource dependence perspective. In M. S. Mizruchi & M. Schwartz (Eds.), Intercorporate relations. The structural analysis of business. Cambridge University Press.

- Pita, M., Lopes, A. P., & Ferreira, J. J.(2021). Entrepreneurial ecosystem and firm performance: A systematic literature review. Journal of Business Research, 132, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.01.042

- Quaidoo, M. (2018). The role of entrepreneurs in economic development: Prospects and challenges of female entrepreneurs in agribusiness in Ghana. https://hdl.handle.net/1813/57393

- Queku, Y. N. (2023). Capital maintenance and depreciation accounting convergence: A new model for sustainability and circularity in capital maintenance. In M. O. Erdiaw-Kwasie & G. M. M. Alam (Eds.), Circular economy strategies and the UN sustainable development goals. Sustainable development goals series (pp. 519–553). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-3083-8_17

- Queku, I. C., & Marfo, M. (2016). Contemporary Internal challenges and Financial sustainability: Evidence from microfinance institutions in Ghana. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 4(11), 199–206.

- Ruiz-Palomino, P., Gutierrez-Broncano, S., Jimenez-Estevez, P., & Hernandez-Perlines, F. (2021). CEO servant leadership and strategic service differentiation: The role of high-performance work systems and innovativeness. Tourism Management Perspectives, 40, 100891. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2021.100891

- Ruiz-Palomino, P., & Martínez-Cañas, R. (2021). From opportunity recognition to the start-up phase: The moderating role of family and friends-based entrepreneurial social networks. International Entrepreneurship & Management Journal, 17(3), 1159–1182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-020-00734-2

- Sackey, J., Sanda, M. A., & Fältholm, Y.(2013). Human factors challenge in entrepreneurship development: An explorative study in a developing economy context. Business and Management Quarterly Review, 4(1), 40–52.

- Salmerón-Gómez, R. García-García, C. & García-Pérez, J.(2020). Diagnosis and quantification of the non-essential collinearity. Computational Statistics, 35(2), 647–666. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00180-019-00922-x

- Schutt, R. K.(2011). Investigating the social world: The process and practice of research. SAGE Publications.

- Seidu, B. A., Queku, Y. N., & Carsamer, E.(2021). Financial constraints and tax planning activity: Empirical evidence from Ghanaian banking sector. Journal of Economic and Administrative Sciences, 39(4), 1063–1087.

- Seidu, B. A., Queku, Y. N., Tackie, G., & Mensah, J. (2022). Working capital-targeting and firms life cycle: Analysis of persistence and speed of adjustment. African Journal of Business and Economic Research, 17(3), 117–143. https://doi.org/10.31920/1750-4562/2022/v17n3a6

- Smith, M. K.(2008). Curriculum theory and practice. SAGE Publications.

- Smith, M. K., Ayanian, J. Z., Covinsky, K. E., & Landon, B. E.(2011). Chasing cascades: A longitudinal investigation of the impact of interphysician communication on physician behavior. Health Services Research, 46(4), 1005–1026. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01245.x

- Sobotie, M. K., & Queku, I. C. (2018). Proposing a theoretical framework to investigate conflict: Perspective of a scuffle. International Journal of Advanced Research (IJAR), 6(4), 1211–1223. https://doi.org/10.21474/IJAR01/6970

- Sperber, S., & Linder, C. (2019). Gender-specifics in start-up strategies and the role of the entrepreneurial ecosystem. Small Business Economics, 53(2), 533–546. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-9999-2

- Stam, E. (2015). Entrepreneurial ecosystems and regional policy: a sympathetic critique. European Planning Studies, 23(9), 1759–1769. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2015.1061484

- Torres-Reyna, O. (2007). Panel data analysis fixed and random effects using Stata (v. 4.2) (Vol. 112). Data & Statistical Services, Priceton University.

- UNSD, W., (2020). Tracking SDG 7: The energy progress report. Washington, DC.

- Vani, G.(2021). A study on the impact of macroeconomic variables on stock prices in India. International Journal of Research in Finance & Marketing, 11(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.18488/journal.137.2021.111.1.12

- Van Weele, A. (2018). Purchasing and supply chain management. UK. Cengage Learning EMEA.

- Waiyaki, J.(2013). The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intentions of university students in Kenya. Journal of Education & Practice, 4(3), 1–10.

- Warwick, K. (2013). Beyond industrial policy: Emerging issues and new trends. OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers, 2013(2), 1–56. https://doi.org/10.1787/5k4869clw0xp-en

- Wooldridge, J. M.(2006). Cluster-sample methods in applied econometrics: An extended analysis. Michigan State University mimeo.

- Yan, Y., & Guan, X.(2019). The impact of social media on consumer behavior: An empirical study of factors influencing consumer purchase intention in China. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 13(4), 456–472.