?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

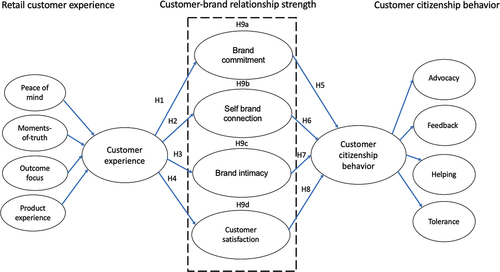

In the retail industry, customer experience over time is the overall customer perception after making transactions with retailers. This concept has been increasingly important since it can help retailers to gain competitive advantages. However, there has been a lack of studies investigating how customer experience over time inspires customers to engage in customer citizenship behavior, especially via the mediation of customer-brand relationship strength. To bridge the gap, this study examines the mediating role of customer-brand relationship strength on the associations between retail customer experience over time and customer citizenship behavior in retail industry. Specifically, the four components of customer-brand relationship strength including brand commitment, self-brand connection, brand intimacy, and customer satisfaction are investigated their mediations on the relationships between retail customer experience over time and customer citizenship behavior. Besides, the four dimensions of retail customer experience over time (i.e. product experience, peace of mind, moments-of-truth, and outcome focus) and of customer citizenship behavior (i.e. advocacy, feedback, helping, and tolerance) are also investigated. A self-administrated survey was conducted utilizing a convenient sampling method. The data, collected from 341 customers of electronics and home appliance retailers, was analyzed by employing PLS-SEM. The results indicate that customer experience over time induces customer brand relationship strength, which subsequently affects customer citizenship behavior. The data analysis results also figure out the mediating role of customer brand relationship strength on the relationship between customer experience over time and customer citizenship behavior. These findings contribute significantly to theoretical and practical implications in retail environment.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

In the retail industry, customer experience over time is the overall perception of customer after making transactions with the retailers. This concept has been increasingly important since it can help retailers to gain competitive advantages. Based on survey data collected from 341 customers of electronics and home appliance retailers, this study finds that customer experience over time induces customer brand relationship strength, which subsequently affects customer citizenship behavior. The research also figures out the mediating role of customer brand relationship strength on the relationship between customer experience over time and customer citizenship behavior. As a result, retailers can use this research’s findings to develop customer experience strategies to gain customer brand relationship strength, which can differentiate themselves from competitors in an era of personalization preference. Furthermore, retailers should invest into integrated information system which is able to track customers’ interaction journey and managers should look for employees with social competence to develop brand relationships with customers. More specifically, retail managers should notice employees while developing brand commitment and customer satisfaction, they also put efforts to build brand intimacy as well as self-brand connection.

1. Introduction

Customer experience has become increasingly important and is considered a strategic approach to building competitive advantage for businesses (Wanwisa et al., Citation2022; Wilbert et al., Citation2022). With the rapid development of the retail industry, customer experience has become the main source of sustainable competitive advantage for retailers. Retailers have focused on improving customer experiences in diverse shopping situations to achieve sustainable customer satisfaction. A recent report by Price Waterhouse Cooper, indicates that 73% of customers place more importance on experience rather than price or quality (Rotageek, Citation2021). Customers find that a positive experience has a stronger influence than advertising, and more than 40% of them are willing to pay more for friendly and welcoming experiences (Rotageek, Citation2021). Contemporary retailing has evolved from providing a transactional exchange process to delivering a memorable shopping experience (Jin & Sternquist, Citation2004). Retail stores selling products such as electronics and home appliances, clothing, and cosmetics do not simply sell goods, but also sell service experience.

Customer experience in a retail setting, which is viewed as a retail customer experience, involves the integration of a series of events that provide pleasurable, involving, relaxing, rewarding, and delightful experiences in the entire purchase cycle, including pre-purchase, purchase, and post-purchase phases (Homburg et al., Citation2017). During this journey, diverse and complicated situations usually occur, such as confusion of alternative product/service choices, ordering and payment, employees’ service recovery performance, and the quality of customers’ interactions with employees (Lemon & Verhoef, Citation2016). Furthermore, this journey could continuously extend when customers make repurchases (Siebert et al., Citation2020). Moreover, customer experience during each subsequent purchase cycle tends to build on experiences from prior cycles (Siebert et al., Citation2020). Therefore, the customer experience journey occurs not only within a single purchase cycle but also within multiple purchase cycles. Therefore, it is essential to comprehensively measure this experience journey in multiple purchase cycles. Better management of customer experience and customer relationship has attracted much scholarly attention (Homburg et al., Citation2017; Kuehnl et al., Citation2019; Lemon & Verhoef, Citation2016; Siebert et al., Citation2020). However, most studies have only examined customer experience journey within a single purchase cycle and have under-examined it within multiple purchase cycles (e.g., Bustamante & Rubio, Citation2017; Happ et al., Citation2020; Kuppelwieser, Citation2022). For example, Bustamante and Rubio (Citation2017) analyze customer experience through cognitive, affective, physical, and social dimensions in a physical store within a purchase cycle. Roy et al. (Citation2022) examine customer experience based on the cognitive, emotional, physical, sensory, and social elements that mark the customer’s direct or indirect interaction with employees and other customers in a retail setting within a single purchase cycle. Happ et al. (Citation2020) also measure customer experience through cognitive, affective, social, and physical dimensions in a sports retail in-store environment within a single purchase cycle. Measuring the customer experience journey within a purchase cycle is insufficient to evaluate firms’ customer experience performance over a long period across multiple purchase cycles, which influences firms’ customer relationship management effectiveness (Homburg et al., Citation2017; Kuehnl et al., Citation2019; Lemon & Verhoef, Citation2016; Siebert et al., Citation2020).

However, much interest from scholars and practitioners has been given to customer-brand relationship, which refers to the bond between customers and brands (Han et al., Citation2021; Rehan et al., Citation2022). Recent studies have suggested that customer-brand relationship strength has a positive impact on customer citizenship behavior, which refers to voluntary and discretionary behaviors that are not required to deliver successful consumption but only aim to help the firm (Hur et al., Citation2020; Liu & Lin, Citation2020). In these studies, customer-brand relationship strength is nurtured by favorable brand experience (Liu & Lin, Citation2020) or the brand’s positive corporate social responsibility activities (Hur et al., Citation2020). This study contends that customer-brand relationship strength nurtured by customer experience over time may generate customer citizenship behavior that can be explained by social exchange theory. Social exchange theory suggests that customers feel obligated to pay back to the retailer from which they receive benefits (Blau, Citation1964; Groth, Citation2005; Hollebeek, Citation2011; Xie et al., Citation2014). Specifically, this study contends that when customers experience positive consumption interactions over time with the retailer, they feel obligated to reward the retailer with customer citizenship behavior.

Drawing on social exchange theory and adapting a measure for retail customer experience over time across multiple purchase cycles (Klaus & Maklan, Citation2013), this study aims to comprehensively evaluate customer experience performance over a long period. Further, this study attempts to examine the effect of customer experience journey on customer-brand relationship, which in turn affects customer citizenship behavior. By doing this, this study enriches empirical evidence of the impact of customer-brand relationship on customer citizenship behavior, resulting from the customer experience journey. Furthermore, these findings provide managerial implications for retailers regarding customer experience and customer relationship management.

2. Theoretical background and hypotheses development

2.1. Social exchange theory

Social exchange theory states that people build and maintain relationships because they believe that relationships are beneficial to everyone, resulting in reciprocity between parties (Blau, Citation1964). Specifically, when people benefit from others’ actions, they feel responsible to reciprocate. This study shows that social exchange occurs between service providers and customers during the service recovery process, and such an exchange can increase customer satisfaction, word-of-mouth (Jung & Seock, Citation2017), and customer citizenship behavior (Anaza & Zhao, Citation2013). Based on social exchange theory, this study builds a research model presenting customer-brand relationships derived from customer experience over time as a source of benefits that the retailer delivers to the customer over the long-term experience journey across multiple purchase cycles. Giving benefits to customers makes them feel obligated to pay back to the retailer, resulting in customer citizenship behavior. Next, this study discusses the literature on the variables proposed in the research model and justifies the relationships between them.

2.2. Customer experience in retail environment

Customer experience in a retail environment is a dynamic and iterative journey of purchase in nature, through which customers interact with components in this environment. A retail environment contains various components, such as products, people, physical environments, policies (e.g., product warranties and returns), and procedures (e.g., ordering and payment) (Garaus, Citation2017), and consumers typically have a series of contacts with retail components over time (Lemon & Verhoef, Citation2016). Verhoef et al. (Citation2009) identify components of retail customer experience, including interactive environments such as the social environment, service interface, retail atmosphere, and product experience such as assortment, price and promotions, and loyalty programs. According to Meyer and Schwager (Citation2007), retail customer experience needs to focus on retail service attributes such as delivery, representation of products and services, advertisement, and new reports that could align with the physical environment or atmospherics, other customers and employees, and service delivery processes to help customers co-create their desired experiences (Teixeira et al., Citation2012). Grewal et al. (Citation2009) identify promotion, price, merchandise, supply chain, and location as key drivers for a superior retail customer experience. Thus, the retail customer experience consists of many independent and interactive contact points during the journey. However, unexpected events often occur during the purchase cycle, such as payment service problems, product failure within the warranty period, or confusion from over-choice and lack of choice (Turunen & Pöyry, Citation2019), which comprehensively reflect customer experience toward the retailer. Gijsenberg et al. (Citation2015) show that retail customer experience can result in negative experiences, such as service failures, which affect customer experience in both the short and long term and require more effort to achieve the same customer experience than before such failures. Therefore, it is necessary to use a measurement of customer experience covering the purchase cycle, which more accurately measures the overall perceptions of customer experience.

2.3. Customer experience measurement

As a comprehensive measure of customer experience, Klaus and Maklan (Citation2013) have developed components to measure customer experience over time. The components are as follows: product experience, outcome focus, moments-of-truth, and peace-of-mind. Product experience is related to the customer’s perception of being able to receive and compare different options before making a decision, which plays an important role in creating the customer experience (Bui & Kemp, Citation2013). Outcome focus reflects the effectiveness of purchase outcome-oriented customer experiences, such as seeking out and qualifying different retailers, which helps customers decrease their transaction costs by finding a more suitable retailer. Moments-of-truth emphasizes the importance of the retailers’ capability and flexibility in dealing with customers when problems or complications arise, which affects the customer’s decision-making when faced with problems at the retailer (Jong & Ruyter, Citation2007). Peace-of-mind emphasizes customers’ emotional experiences with the service providers’ perceived expertise and commitment in during the purchase cycle journey.

2.4. Customer-brand relationship strength as a consequence of customer experience

A customer experience going through a long purchase cycle journey nurtures a strong customer-brand relationship. Customer-brand relationship refers to the bond between customers and brands (Rehan et al., Citation2022), and its strength can be fostered by developing interactions and connections over time (Arcand et al., Citation2017). A strong customer-brand relationship contains four indicators: brand commitment, self-brand connection, brand intimacy, and customer satisfaction (Aaker et al., Citation2004). We contend that the customer-brand relationship derived from the retail customer experience over the long purchase cycle journey develops into brand commitment, self-brand connection, brand intimacy, and customer satisfaction.

Brand commitment refers to the desire to maintain the exiting relationship with the brand (Aaker et al., Citation2004). Customers manifest their relationship with a brand through psychological attachment to a service provider, which ensures that the relationship is maintained over time (Shaikh et al., Citation2015). In the retail environment, customers experience the service providers’ involvement in helping to recover product/service failures during purchase and post-purchase (Jafarzadeh et al., Citation2021), providing useful advice or suggestions regarding the best option (Pantano & Gandini, Citation2017), or performing well in product warranty services for customers before, during, and after purchase, even during another purchase cycle (Borchardt et al., Citation2018). The abundance of purchase benefits enables customers to hold a positive emotional attachment or psychological bond (Allen & Meyer, Citation1990) and feel obligated toward the brand (Allen & Meyer, Citation1990). These bonds motivate customers to devote efforts to maintaining and solidifying their relationship with the brand (Morgan & Hunt, Citation1994; Shaikh et al., Citation2015). Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1:

Customer experience in the retail environment has a positive impact on brand commitment.

Self-brand connection refers to the extent to which brand associations connect strongly with customers’ psychosocial needs and identities (Aaker et al., Citation2004). Brand associations, which could be either functional attributes such as quality, professionalism, installations, and warranty, or intangible factors such as advertising, price, and brand community, can connect customers’ self-identity with the brand and present themselves to others (Sirgy, Citation1985). Hollebeek et al. (Citation2014) consider that customers’ interactive experiences with the brand develop customer self-brand connection. In a retail context, generating positive interactive experiences with the retailer while fulfilling customers’ individual needs and appropriately responding to their purchase situations helps build a strong connection between the retailer and customers’ identity. Every positive touch point related to either functional attributes or intangible factors of the brand incorporates customers’ self-identity and transforms it into congruency with customers’ self-identity (Ballantine et al., Citation2015). Wijnands and Gill (Citation2020) show that self-congruity with a brand positively influences self-brand connection. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2:

Customer experience in the retail environment has a positive impact on self-brand connection.

Intimacy refers to a deep mutual understanding created through information disclosure between the brand and customer (Aaker et al., Citation2004). Information disclosure can be understood as an exchange of information that facilitates both parties’ understanding toward completing a particular task (Dellaert et al., Citation2005). In the shopping environment, positive interaction between the retailer brand and customers encourage customers to disclose more personal information to the retailer to let the retailer better cater to customer needs. The more information that the retailer has about a particular customer, the more value it is able to provide to that customer (Moon, Citation2000). According to reciprocity principle, people are more likely to be attracted to those who provide them information, and simultaneously, they are also more likely to be attracted to those who they disclose information to. Therefore, consistent interpersonal interaction for transactional information exchange between the retailer brand and the customer generates intimacy (Orehek et al., Citation2018). Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3:

Customer experience in the retail environment has a positive impact on brand intimacy.

Satisfaction indicates the customer’s cognitive and affective states resulting from the overall performance appraisal of the brand over time (Wilbert et al., Citation2022)). In the retail setting, product experience, such as looking for various product categories and colors, product availability, trying on products in the physical store, and searching for product information about attributes; technical specifications; and prices in the e-store, influence customer satisfaction (Flavián et al., Citation2019). The process of choosing an item in online and offline stores influences customer satisfaction (Lazaris et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, customer experience with staff skills and knowledge in performing retail tasks, such as providing adequate products/services to the customer or delivering efficient service or providing solutions for the customer’s individual problems and needs, nurture trust and customer satisfaction toward the employees and the retailer (Van Dat & Ngoc, Citation2022). Furthermore, customer experience of effective purchase outcomes with the retailer (i.e., transaction cost-saving) over time, through a mutual understanding between the customer and retailer, leads to customer satisfaction (Bharadwaj & Matsuno, Citation2006). Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H4:

Customer experience in the retail environment has a positive impact on brand satisfaction.

2.5. Customer citizenship behavior as a consequence of customer-brand relationship strength

Customer citizenship behavior refers to a customer’s voluntary and discretionary behavior to perform unsolicited, helpful, and constructive behaviors toward other customers and the company (Groth, Citation2005; Liu & Lin, Citation2020; Yi & Gong, Citation2013). Groth (Citation2005) suggests that customer citizenship behavior consists of three dimensions: providing recommendations to others, providing feedback to the organization, and helping other customers. Yi and Gong (Citation2013) identify four dimensions of customer citizenship behavior: providing useful feedback for the organization to improve service quality, helping employees and other customers, providing positive recommendations to friends, and tolerating service failures. For example, in a shopping environment, customers may engage in customer citizenship behavior such as sharing a positive experience (e.g., friendliness and hearty welcome of retail staff) with friends and relatives. They can also post positive word-of-mouth and induce user-generated content on retailers’ websites and social networking sites that can support the competitiveness of retailers. They may share insights on how the payment process can be improved. They can support other customers in store or on retailers’ websites regarding the proper use of products/services. In addition, they may be willing to wait for their turn during peak hours or tolerate mistakes if a wrong product is given. This study uses the four dimensions from Yi and Gong (Citation2013) to measure customer citizenship behavior.

Many studies have indicated that consumers’ strong relationship with a brand disproportionately generate customer citizenship behavior (Xie et al., Citation2017). This can be explained by the social exchange theory (Blau, Citation1964; Groth, Citation2005; Yi & Gong, Citation2008). This mechanism is also applied to consumer behavior. When customers experience a benefit during the purchase journey with the retail brand, they feel obligated to reciprocate the retail brand, and their reciprocity takes the form of customer citizenship behavior.

Previous research has shown that commitment to the retail staff and/or retailer brand results in customer citizenship behavior toward the retail staff and/or retailer brand (Yi & Gong, Citation2008). A commitment motivates a person to engage in behaviors that cement and strengthen their relationship with their partners. Bettencourt (Citation1997) results show that customer commitment to the retailer brand increases the willingness to engage in voluntary behaviors such as positive word-of-mouth and active voice. Furthermore, customer citizenship behavior happens to other customers to whom the customer commits to bringing benefits from the organization (Bettencourt, Citation1997). For example, a customer can teach or give advice to other retail brand customers on how to use the brand’s products/services correctly. Thus, customers may engage in customer citizenship behavior to maintain the relationship with the retailer brand. Accordingly, we propose the following hypothesis:

H5:

Brand commitment has a positive impact on customer citizenship behavior.

Self-brand connection results from consumers’ interactive experiences with a brand connected to consumers’ self-identity. According to the self-congruity theory, positive interactions with customers during the consumption journey create congruity between the customer’s self-identity and brand identity (Sirgy et al., Citation1997). Cable and Judge (Citation1997) support that communication and social interactions are smoother when people experience a reduction in cognitive dissonance, which implies similarity attraction. As such, congruency with self-identity encourages customers to sustain their relationship with the brand and develop brand support behaviors, such as brand defense, share of wallet for the brand (Park et al., Citation2010), brand advocacy, and brand loyalty (Roggeveen et al., Citation2021). Social exchange theory suggests that customers engage in a social exchange based on perceptions of their own benefits and costs (Blau, Citation1964). Beneficial resources that customers receive from social exchanges with brands could be economic, emotional, cognitive, social, and physical (Hollebeek, Citation2011). Self-brand connection encourages customers to connect with others to present their self-identity congruency with the brand (Tan et al., Citation2018). In a retail setting, when interactive experiences with the retailer brand over time benefit customers’ psychosocial needs of self-identity congruence, customers feel obligated to reciprocate the brand through customer citizenship behavior. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H6:

Self brand connection has a positive impact on customer citizenship behavior.

Intimate communication with customers enables retailers to truly capture customers’ needs and preferences (Yim et al., Citation2008). This requires customers to disclose extensive personal information so that the retailer can understand customers’ current and future needs (Okazaki et al., Citation2020). Correspondingly, customers consider the retailer’s concern and commitment to understand their needs. This helps the retailer enhance customers’ well-being, maintain a close relationship with its customers, and continuously offer value propositions to customers. According to social exchange theory, social exchanges may also be symbolic benefits, such as praise, respect, intimacy, and aspiration, and people also feel obligated to reciprocate those who provide them symbolic benefits (Blau, Citation1964; Cropanzano & Mitchell, Citation2005). Furthermore, Granovetter’s (Citation1973) social psychology research on person-to-person relationships indicates that frequent contact and intimacy with others lead a person to give more support than others with little or no intimacy. Blackston (Citation1992) reports that customers who engage in an intimate relationship with a brand are more willing to help the brand and its other customers. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H7:

Brand intimacy has a positive impact on customer citizenship behavior.

Customer satisfaction is expected to predict customer citizenship behavior during the consumption journey, which can be explained by the social exchange theory (Groth, Citation2005). The social exchange relationship between customers and retailers is based on value offering. Specifically, when customers are satisfied with the retailer due to cognitive and affective interactions that exceed their expectations, they are willing to reciprocate with customer citizenship behavior that may benefit the retailer. Furthermore, when customers are satisfied with the retailer’s performance, their feelings of gratitude toward the retailer motivate them to reward the retailers (Lovemore et al., Citation2021) and help other customers (Cropanzano & Mitchell, Citation2005; Groth, Citation2005). For example, when customers experience exceptional value from the retailer, such as empathy and cost reduction, they want to return the favor by helping other customers benefit from these values. By doing so, retailers may benefit because more customers may purchase their products. Thus, customers may engage in customer citizenship behavior to repay the retailer, suggesting the following hypothesis:

H8:

Customer satisfaction has a positive impact on customer citizenship behavior.

2.6. The mediating role of customer brand relationship strength

Positive emotions derived from retail customer experience, such as pleasure, enjoyment, and excitement, may be important predictors of customer citizenship behavior. Such positive emotions are expected to encourage customers to engage in customer citizenship behavior. However, positive outcomes could be leisure shopping as subjectively experienced (Backstrom, Citation2011) and may not be sufficient to induce customer citizenship behavior. However, they help in creating and maintaining relationship continuity between customers and the brand, especially in a shopping environment where various situations need to be connected, such as physical product assortment, atmosphere, service/product failure, and the sales force (Gilboa et al., Citation2019). Retail customer experience-triggered relationship continuity over time creates benefits for customers; thus, it strengthens customer brand relationship (Gilboa et al., Citation2019; Lemon & Verhoef, Citation2016), encouraging consumers to engage in reciprocal activities (Chai et al., Citation2011). According to social exchange theory, people feel obligated to reciprocate the target and the people related to the target, and commit to the relationship when the target benefits them (Blau, Citation1964; Cropanzano & Mitchell, Citation2005). This finding supports the mediating role of customer brand relationship strength in the relationship between retail customer experience and customer citizenship behavior. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H9:

Brand commitment (a), self brand connection (b), brand intimacy (c) and (d) customer satisfaction mediates the relationship between customer experience and customer citizenship behavior.

The proposed research model is presented in Figure .

3. Methods

3.1. Measures

This study used survey method to collect data for the constructs in the proposed research model. Therefore, a questionnaire was designed based on the constructs. The constructs were adopted from the validated measurements of previous studies. In particular, Klaus and Maklan (Citation2013) used four constructs: peace of mind, moments-of-truth, outcome focus, and product experience as a first-order construct with reflective indicators to measure customer experience over time as a second-order construct with formative indicators. Thus, customer experience over time construct could be considered a reflective, formative second-order construct (Klaus & Maklan, Citation2013). The four constructs included 6 items for peace of mind, 5 items for moments-of-truth, 4 items for outcome focus, and 4 items for product experience. Klaus and Maklan (Citation2013) developed all items of these four constructs in a retail environment relevant to the context of this study. Thus, this study adopted all of these items. Measures of customer-brand relationship, including brand commitment with 5 items, brand intimacy with 5 items, customer satisfaction with 3 items, and self-brand connection with 5 items, were adopted from Aaker et al. (Citation2004). These four constructs were used to measure customer-brand relationships over time (Aaker et al., Citation2004), which is relevant to the focus of customer-brand relationship strength driven by customer experience over time. Therefore, this study adopted all of these items. Yi and Gong (Citation2013) used four constructs—advocacy, helping, feedback, and tolerance—as first-order constructs with reflective indicators to measure customer citizenship behavior as a second-order construct with reflective indicators. Thus, the customer citizenship behavior construct is considered a reflective second-order construct (Yi & Gong, Citation2013). The four constructs included advocacy with 3 items, helping with 4 items, feedback with 3 items, tolerance with 3 items, all of which manifest customers’ deeply supportive behaviors resulting from feelings of obligation to repay the retailer (van Tonder et al., Citation2018). Thus, this study adopted all items of these four constructs to measure customer citizenship behavior. All items of the constructs used a seven-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Additionally, one item measuring overall customer experience (i.e., the overall experience of this retailer’s products and services is wonderful) was added for the redundancy test of the formative construct (Chin, Citation1998).

To ensure content validity, the questionnaire was checked by three academicians from three reputed national universities. The revised questionnaire was then distributed to 15 undergraduate students to re-check the content validity and elicit feedback on whether the items that measured each construct were understandable and represented their own construct. Checking the questionnaire twice confirmed the content validity of the items that are measuring their own constructs.

3.2. Data collection

The retail industry has evidenced rapid growth and expansion in recent years (Ying et al., Citation2021). While it is suggested that every retailer should do their best to offer quality products with reasonable prices (Gielens et al., Citation2021), customer experience seems to be more important to retailers than selling quality products with reasonable prices (Rotageek, Citation2021). Furthermore, Lase et al. (Citation2021) indicates that customers engage in a long consumption journey for electronics and home appliance products and this study thus chose electronics and home appliance retailers to examine relationships between customers and the retailers derived from customer experience over time with the retailers. We chose Nguyen Kim, Dien May Xanh and The Gioi Di Dong as the three biggest electronics and home appliances retailers in Vietnam to collect data.

Data collection of this study was employed by sending out an online survey link to international program students of two big universities in Ho Chi Minh city (i.e., HCMC University of Banking and HCMC University of Technology and Education), Vietnam within two months from April to June in 2022. To qualify respondents who had customer experience over time, respondents were first exposed the question: “Have you repurchased any products in Nguyen Kim, Dien May Xanh, or The Gioi Di Dong within the last six months?. If yes, please continue to answer the survey. Otherwise, please stop here.” Then, respondents gave responses regarding constructs in the proposed research model. Out of 373 responses, 32 responses were not qualified for missing values and the same responses across the survey, which results in only 341 responses retained for a further analysis. For sample profile see in Table .

Table 1. Sample profile

4. Data analysis and results

PLS-SEM has been well-known to effectively handle predictive models, and reflective and formative measurement model (Hair et al., Citation2019; Rigdon et al., Citation2017). This study tested a multi-step model to predict customer citizenship behavior from customer-brand relationship strength derived from customer experience over time. In addition, customer experience was formatively measured and the structural model of this study contains both reflective-reflective and reflective-formative second-order constructs. Thus, this study used the partial least square structural equation model (PLS- SEM) method and SmartPLS 3.2.9 software to analyze both the measurement model and the structural model.

4.1. Validation of measures: reliability and validity

In this study, the measurement model estimation used a disjointed two-stage approach, suggested by Sarstedt et al. (Citation2019) since the measurement model contains both reflective-reflective second-order constructs (i.e., customer citizenship behavior) and reflective-formative second-order constructs (i.e., customer experience). Specifically, In Stage I, Cronbach’s Alpha and composite reliability (CR) were used for assessing reliability, and average variance extracted (AVE) and factor loadings were used for evaluating convergent validity. As shown in Table , the results indicated that Cronbach’s Alpha and CR values were greater than 0.7, confirming reliability for all reflective constructs. In addition, all factor loadings were greater than 0.7 and AVE values were greater than 0.5, providing evidence for convergent validity for these constructs.

Table 2. Convergent validity and reliability

For checking discriminant validity, this study used the square root of AVE of each construct was greater than its bivariate correlations between this construct and other constructs. As shown in Table , the results indicated that the square root of AVE of each construct was greater than its bivariate correlations, demonstrating discriminant validity for all constructs.

Table 3. Correlation matrix and discriminant validity

Next, in Stage II, latent scores obtained from Stage I were used as indicators for the reflective-reflective second order construct (i.e., CCB) and components for the reflective-formative second order construct (i.e., CE). In particular, the assessment for the measurement validation of CCB applied the same criteria as for the reflective constructs in Stage I. As shown in Tables , the assessment values provided evidence for reliability, and convergent and discriminant validity for CCB.

Regarding the assessment for the measurement validation of Customer Experience, redundancy analysis was employed to evaluate convergent validity of CE. CE was regressed on a single-item measure referring to the overall customer experience. As displayed in Table , the results showed that the path coefficient is 0.76 within a 95% percentile confidence interval of [0.707; 0.809], confirming convergent validity of CE (Cheah et al., Citation2018). Next, the VIF values of peace-of- mind, moments-of-truth, outcome focus, and product experience ranged from 1.04 to 1.35, indicating that there was no threat of multicollinearity among the components. In addition, all four components had significant effects on customer experience. Thus, this study concluded that the formative measurement of customer experience was valid.

Table 4. Redundancy analysis for a formative construct

4.2. Structural model results

To test hypotheses proposed in the research model, the VIF values of predictive variables were firstly checked. As shown in Table , VIF values of all predictive variables were lower than 3.0, ranging from 1.00 to 2.59, indicating that there was no serious issue with multicollinearity (Hair et al., Citation2016). Additionally, the results shown in Table indicated that all eight hypotheses of direct effects from H1 to H8 were supported. In particular, customer experience had significant effects on brand commitment, self brand connection, customer satisfaction, and brand intimacy. Furthermore, brand commitment, self brand connection, customer satisfaction, and brand intimacy had positive impacts on customer citizenship behavior. Lastly, all four hypotheses of mediating effects from H9a to H9d were supported.

Table 5. Hypothesis testing results

To examine explanatory power and predictive power of the proposed research model, coefficient of determination (R2) and Stone-Geisser (Q2) were used. Specifically, as showned in Table , the results showed R2 for endogenous variables ranged from 0.18 to 0.78, indicating the research model’s adequate explanatory power. In addition, the Q2 values were all greater than 0, providing evidence for the research model’s predictive relevance.

5. Discussion

Although customer experience over time is in the nature of the retail industry, research that comprehensively investigates customer experience in retail setting is limited. Moreover, the concept of customer experience over time remains elusive because it is primarily measured in one part of the consumption experience journey (Atkins et al., Citation2012; Babin et al., Citation1994; Bustamante & Rubio, Citation2017). In addition, previous studies have not empirically tested the impact of customer experience over time on customer brand relationship strength in a retail setting. Specifically, this link has been conceptually (Lemon & Verhoef, Citation2016) or qualitatively (Chang & Chieng, Citation2006) proposed in literature. Furthermore, customer experience over time can strengthen customer brand relationship, which is a company’s brand equity that promotes customer citizenship behavior. Therefore, examining whether customer experience over time produces encouraging outcomes in retail settings is essential.

This study finds that customer experience over a long consumption journey significantly impacts customer brand relationship strength (H1-H4). Specifically, customer experience is associated with the development of the relationship between customers and retailer into brand commitment, brand intimacy, customer satisfaction, and self-brand connection. This study is also the first to test customer experience over time in a retail setting as an antecedent to customer brand relationship strength indicators. These findings suggest that close relationships can be achieved by delivering positive customer experiences over time. Furthermore, frequent communication between customers and retailers in various situations of consumption over time increases the parties’ mutual knowledge, thereby fostering the development of commitment, satisfaction, connection, and intimacy. The findings are consistent with the recent studies on customer experience. For instance, Gilboa et al. (Citation2019) prove that customer experience leads to positive attitudes (trust and commitment), which in turn, are positively linked to customer loyalty and word-of-mouth. Specifically, customer experience influences commitment and brand loyalty, and the impact is stronger than the calculative path, highlighting the importance of emotional bond (Khan et al., Citation2020). Happ et al. (Citation2020) reveal that customer experience helps determine customer satisfaction and likelihood to recommend the brand to other customers. We also find that customer-employee interaction plays a significant role in creating a great customer experience. Therefore, the study’s results enhance the customer brand relationship literature derived from customer experience over time.

Additionally, this study finds that customer brand relationship strength has a significant effect on customer citizenship behavior (H5-H8). These findings are consistent with those of previous studies, which suggest that efforts of relationship maintenance through maintaining close and frequent contact with customers lead to less conflict and better collaborative behavior (Eisingerich & Bell, Citation2007), and thus, higher compliance and forgiveness (Zemack-Rugar et al., Citation2017).

Finally, this study finds that indicators of customer brand relationship strength significantly mediate between customer experience and customer citizenship behavior (H9a-H9d). This has rarely been investigated in extant literature. For example, Ramaseshan and Stein (Citation2014) claim that although customers may have continuous pleasurable experiences during their consumption journey, the experiences may be insufficient to generate customer loyalty unless the experiences induce customers’ strong cognitive and emotional responses to customer brand relationships. This study enriches the understanding of the role of customer experience in enhancing customer-brand relationship strength, leading to customer citizenship behavior; thus, it contributes significantly to the customer citizenship behavior literature.

6. Managerial implications

Retailers can use this research’s findings to develop customer experience strategies to gain customer brand relationship strength, which can differentiate themselves from competitors in an era of personalization preference. The recent research reports that customers still encounter negative experiences with the retailers/service prodviers (Mathayomchan & Taecharungroj, Citation2020; Van Nguyen et al., Citation2022). In the real world, providing customer experience is not an easy task because it is in nature of complexity and multidimensionality (Walter et al., Citation2010). Therefore, retailers should pay closer attention in order to attain customer brand relationship strength.

Furthermore, this study allows managers to understand customer experience over time in more details. Specifically, peace of mind and outcome focus were identified as the most important components, indicating retail managers should put efforts to train employees’ expertise to support customers’ consumption journey easily as well as to produce good outcomes for customers during consumption journey. Additionally, retailers should make employees understand that, in order to harvest strength of relationship with customers, delivering objective advice, the promised services problem resolution, good outcomes commitment is a must. Next, given the high complexity of cycle consumption, retailers should integrate and control customers’ continuous record of individual interactions so that all touch points are well-delivered and thus customers better appreciate their offerings and avoid misconceptions. Therefore, retailers should invest into integrated information system which is able to track customers’ interactions journey and managers should look for employees with social competence to develop brand relationships with customers. As suggested by Bolton et al. (Citation2018) customers more and more require a superior experience. Thus, personalized, and tailored experiences based on customer relationship management strategies are very essential and should be designed carefully.

Additionally, this study’s findings showed that the development of brand commitment, brand intimacy, customer satisfaction, and self brand connection results in customer citizenship behavior. Thus, retail managers should notice while developing brand commitment and customer satisfaction, also put efforts to build brand intimacy as well as self brand connection. This is consistent with the notions that price is not the top factor, but rather responsive employees and their ability to solve problems to earn satisfaction with the retailer and personal connection to earn self brand connection have in fact become more paramount in promoting customer citizenship behavior. Finally, as customer citizenship behavior is important to success of retailers, managers should adopt a holistic view of customer citizenship behavior as presented in this study to plan and implement effectively their CCB strategies. This view is because covering advocacy, helping, feedback, and tolerance help retailers to acquire, retain, and harvest customer lifetime value.

7. Conclusion, limitations and suggestions for future research

This study bridges some key gaps in the existing literature by validating the mediation of customer-brand relationship strength on the associations between customer experience over time and customer citizenship behavior. Specifically, all the four components of customer-brand relationship strength including brand commitment, self-brand connection, brand intimacy and customer satisfaction significantly mediate the influence of customer experience over time on customer citizenship behavior. In addition, the research also proves that customer experience over a long consumption journey strengthens customer brand relationship strength by positively influencing brand commitment, self-brand connection, brand intimacy and customer satisfaction. Further, significant and positive relationships between customer brand relationship strength and customer citizenship behavior are also evidenced. As a result, the study contributes significantly to the existing knowledge of customer experience over time and customer citizenship behavior in a retail environment.

There are some limitations to be acknowledged for future research. Data collection method in this study was convenience sampling, which raises caution in generalizing results, particularly considering that brand reputation may result in customer citizenship behavior (Bartikowski & Walsh, Citation2011). Future research should examine both brands with and without reputation to validate the findings of research model in this study. Additionally, prior studies show social influence as a factor outside a company’s control is positively associated with customer brand quality such as brand love (Le, Citation2021). Thus, future research could investigate a moderating role of social influence on the relationship between customer brand relationship strength and CCB. This investigation may contribute to increase in CCB. Besides, this study collected data from students, thus future research could use quota sampling method to collect data from other occupations such as company employee, housewife, frontline employees to gain a better representation of sample to check whether future research’s findings are still consistent with this study’s ones. Furthermore, a longitudinal study would offer more accurately about customer experience over time and customer brand relationship strength. This study considers customer experience over time in cross-sectional data. Furthermore, a longitudinal study should study presence of negative experiences in consumption journey such as service failures to see whether customer brand relationship strength and CCB are still held.

ABout the Author_Public interest statement.docx

Download MS Word (29.5 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2292487

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Hoa PhamThi

Hoa PhamThi is a senior lecturer of marketing at International School of Business, University of Economics Ho Chi Minh City, HCM City, Vietnam. Her research interests include retail customer experience, brand experience, impulse buying, shopping effectiveness with omnichannel, value co-creation, and sustainable consumption behavior. Her work has been published in Service Business, Journal of Fashion and Marketing Management, among others. Several of her current research projects are: - Shopping effectiveness with omnichannel: a MOA perspective - Effect of a negative self-view of impulse buying on consumption reduction behavior: a compensation model - Immersive technology-enabled customer experience on customer engagement behavior.

Trong Nghia Ho

Trong Nghia Ho is a senior lecturer of marketing at International School of Business, University of Economics Ho Chi Minh City, HCM City, Vietnam. His research interests include shopping value, shopping well-being, impulse buying, consumer behavior in different channel (online vs offline), and KOL Marketing. His work has been published in Marketing Intelligence and Planning, Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, amongst others. Some of the on-going research projects are as follows: -Do High Price Promotion Help Brands?- Social Media Influencers: How Public Opinions Are Navigated?- Online shopping well-being as a consequence of shopping value, trust and impulse buying: A duality approach.

References

- Aaker, J., Fournier, S., & Brasel, S. A. (2004). When good brands do bad. Journal of Consumer Research, 31(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1086/383419

- Allen, N. J., & Meyer, J. P.(1990). The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63(1), 1–18.

- Anaza, N., & Zhao, J. (2013). Encounter-based antecedents of e-customer citizenship behaviors. Journal of Service Marketing, 27(2), 130–140. intentions on online shopping websites https://doi.org/10.1108/08876041311309252

- Arcand, M., PromTep, S., Brun, I., & Rajaobelina, L. (2017). Mobile banking service quality and customer relationships. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 35(7), 1066–1087. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-10-2015-0150

- Atkins, K. G., Kim, Y. K., & Runyan, R. C. (2012). Smart shopping: Conceptualization and measurement. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 40(5), 360–375. https://doi.org/10.1108/09590551211222349

- Babin, B. J., Darden, W. R., & Griffin, M. (1994). Work and/or fun: Measuring hedonic and utilitarian shopping value. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(4), 644–656. https://doi.org/10.1086/209376

- Backstrom, K. (2011). Shopping as leisure: An exploration of manifoldness and dynamics in consumers shopping experiences. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 18(3), 200–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2010.09.009

- Ballantine, P. W., Parsons, A., & Comeskey, K. (2015). A conceptual model of the holistic effects of atmospheric cues in fashion retailing. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 43(6), 503–517. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijrdm-02-2014-0015

- Bartikowski, B., & Walsh, G. (2011). Investigating mediators between corporate reputation and customer citizenship behaviors. Journal of Business Research, 64(1), 39–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2009.09.018

- Bettencourt, L. A. (1997). Customer voluntary performance: Customers as partners in service delivery. Journal of Retailing, 73(3), 383–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4359(97)90024-5

- Bharadwaj, N., & Matsuno, K. (2006). Investigating the antecedents and outcomes of customer firm transaction cost savings in a supply chain relationship. Journal of Business Research, 59(1), 62–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2005.03.007

- Blackston, M. (1992). Observations: Building brand equity by managing the brand’s relationships. Journal of Advertising Research, 32(3), 79–83.

- Blau, P. (1964). Power and exchange in social life. John Wiley and Sons.

- Bolton, R. N., McColl-Kennedy, J. R., Cheung, L., Gallan, A., Orsingher, C., Witell, L., & Zaki, M. (2018). Customer experience challenges: Bringing together digital, physical and social realms. Journal of Service Management, 29(5), 776–808. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-04-2018-0113

- Borchardt, M., Souza, M., Pereira, G. M., & Viegas, C. V. (2018). Achieving better revenue and customers’ satisfaction with after-sales services: How do the best branded car dealerships get it? International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 35(9), 1686–1708. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijqrm-01-2017-0016

- Bui, M., & Kemp, E. (2013). E‐tail emotion regulation: Examining online hedonic product purchases. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 41(2), 155–170. https://doi.org/10.1108/09590551311304338

- Bustamante, J. C., & Rubio, N. (2017). Measuring customer experience in physical retail environments. Journal of Service Management, 28(5), 884–913. https://doi.org/10.1108/josm-06-2016-0142

- Cable, D. M., & Judge, T. A. (1997). Interviewers’ perceptions of person–organization fit and organizational selection decisions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(4), 546. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.82.4.546

- Chai, S., Das, S., & Rao, H. R. (2011). Factors affecting bloggers’ knowledge sharing: An investigation across gender. Journal of Management Information Systems, 28(3), 309–342. https://doi.org/10.2753/MIS0742-1222280309

- Chang, P. L., & Chieng, M. H. (2006). Building consumer–brand relationship: A cross‐cultural experiential view. Psychology & Marketing, 23(11), 927–959. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20140

- Cheah, J. H., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., Ramayah, T., & Ting, H. (2018). Convergent validity assessment of formatively measured constructs in PLS-SEM: On using single-item versus multi-item measures in redundancy analyses. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30(11), 3192–3210. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-10-2017-0649

- Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Modern Methods for Business Research, 295(2), 295–336.

- Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31(6), 874–900. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206305279602

- Dellaert, B. G., Golounov, V. Y., & Prabhu, J. (2005). The impact of price disclosure on dynamic shopping decisions. Marketing Letters, 16(1), 37–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-005-0719-8

- Eisingerich, A., & Bell, S. (2007). Maintaining customer relationships in high credence services. Journal of Service Marketing, 21(4), 253–262. https://doi.org/10.1108/08876040710758559

- Flavián, C., Gurrea, R., & Orús, C. (2019). Feeling confident and smart with webrooming: Understanding the consumer’s path to satisfaction. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 47, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2019.02.002

- Garaus, M. (2017). Atmospheric harmony in the retail environment: Its influence on store satisfaction and re‐patronage intention. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 16(3), 265–278. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1626

- Gielens, K., Ma, Y., Namin, A., Sethuraman, R., Smith, R. J., Bachtel, R. C., & Jervis, S. (2021). The future of private labels: Towards a smart private label strategy. Journal of Retailing, 97(1), 99–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2020.10.007

- Gijsenberg, M. J., Van Heerde, H. J., & Verhoef, P. C. (2015). Losses loom longer than gains: Modeling the impact of service crises on perceived service quality over time. Journal of Marketing Research, 52(5), 642–656. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.14.0140

- Gilboa, S., Seger-Guttmann, T., & Mimran, O. (2019). The unique role of relationship marketing in small businesses’ customer experience. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 51, 152–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.06.004

- Granovetter, M. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78(6), 1360–1380. https://doi.org/10.1086/225469

- Grewal, D., Levy, M., & Kumar, V. (2009). Customer experience management in retailing: An organizing framework. Journal of Retailing, 85(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2009.01.001

- Groth, M. (2005). Customers as good soldiers: Examining citizenship behaviors in internet service deliveries. Journal of Management, 31(1), 7–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206304271375

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2016). A primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage Publications.

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Han, H. E., Cui, G. Q., & Jin, C. H.(2021). The role of human brands in consumer attitude formation: Anthropomorphized messages and brand authenticity. Cogent Business & Management, 8(1), 1923355. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2021.1923355

- Happ, E., Scholl-Grissemann, U., Peters, M., & Schnitzer, M. (2020). Insights into customer experience in sports retail stores. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 22(2), 312–329. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSMS-12-2019-0137

- Happ, E., Scholl-Grissemann, U., Peters, M., & Schnitzer, M.(2020). Insights into customer experience in sports retail stores. International Journal of Sports Marketing & Sponsorship, 22(2), 312–329. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSMS-12-2019-0137

- Hollebeek, L. D. (2011). Exploring customer brand engagement: Definition and themes. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 19(7), 555–573. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965254X.2011.599493

- Hollebeek, L. D., Glynn, M. S., & Brodie, R. J. (2014). Consumer brand engagement in social media: Conceptualization, scale development and validation. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 28(2), 149–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2013.12.002

- Homburg, C., Jozić, D., & Kuehnl, C. (2017). Customer experience management: Toward implementing an evolving marketing concept. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45(3), 377–401. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-015-0460-7

- Hur, W. M., Moon, T. W., & Kim, H. (2020). When does customer CSR perception lead to customer extra-role behaviors? The roles of customer spirituality and emotional brand attachment. Journal of Brand Management, 27(4), 421–437. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-020-00190-x

- Jafarzadeh, H., Tafti, M., Intezari, A., & Sohrabi, B. (2021). All’s well that ends well: Effective recovery from failures during the delivery phase of e-retailing process. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 62, 102602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102602

- Jin, B., & Sternquist, B. (2004). Shopping is truly a joy. The Service Industries Journal, 24(6), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/0264206042000299158

- Jong, A., & Ruyter, K. (2007). Adaptive versus proactive behaviour in service recovery: The role of self-managing teams. Decision Sciences, 35(3), 457–491. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0011-7315.2004.02513.x

- Jung, N. Y., & Seock, Y. K. (2017). Effect of service recovery on customers’ perceived justice, satisfaction, and word-of-mouth intentions on online shopping websites. Journal of Retailing & Consumer Services, 37, 23–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2017.01.012

- Khan, I., Hollebeek, L. D., Fatma, M., Islam, J. U., & Riivits-Arkonsuo, I. (2020). Customer experience and commitment in retailing: Does customer age matter? Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 57, 102219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102219

- Klaus, P. P., & Maklan, S. (2013). Towards a better measure of customer experience. International Journal of Market Research, 55(2), 227–246. https://doi.org/10.2501/IJMR-2013-021

- Kuehnl, C., Jozic, D., & Homburg, C. (2019). Effective customer journey design: Consumers’ conception, measurement, and consequences. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 47(3), 551–568. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-018-00625-7

- Kuppelwieser, V. (2022). A glimpse of the future retail customer experience–guidelines for research and practice. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 73, 103205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2022.103205

- Lase, I. S., Ragaert, K., Dewulf, J., & De Meester, S. (2021). Multivariate input-output and material flow analysis of current and future plastic recycling rates from waste electrical and electronic equipment: The case of small household appliances. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 174, 105772. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.105772

- Lazaris, C., Sarantopoulos, P., Vrechopoulos, A., & Doukidis, G. (2021). Effects of increased omnichannel integration on customer satisfaction and loyalty intentions. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 25(4), 440–468. https://doi.org/10.1080/10864415.2021.1967005

- Le, M. T. (2021). The impact of brand love on brand loyalty: The moderating role of self-esteem, and social influences. Spanish Journal of Marketing-ESIC, 25(1), 156–180. https://doi.org/10.1108/SJME-05-2020-0086

- Lemon, K. N., & Verhoef, P. C. (2016). Understanding customer experience throughout the customer journey. Journal of Marketing, 80(6), 69–96. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.15.0420

- Liu, C. F., & Lin, C. H. (2020). Online food shopping: A conceptual analysis for research propositions. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.583768

- Lovemore, C., Charles, M., & Blessing, C. (2021). Understanding mediators and moderators of the effect of customer satisfaction on loyalty. Cogent Business & Management, 8(1), 922127. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2021.1922127

- Mathayomchan, B., & Taecharungroj, V. (2020). How was your meal? Examining customer experience using Google maps reviews. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 90, 102641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102641

- Meyer, C., & Schwager, A. (2007). Understanding customer experience. Harvard Business Review, 85(2), 116.

- Moon, Y. (2000). Intimate exchanges: Using computers to elicit self-disclosure from consumers. Journal of Consumer Research, 26(4), 323–339. https://doi.org/10.1086/209566

- Morgan, R. M., & Hunt, S. D. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 58(3), 20–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299405800302

- Okazaki, S., Eisend, M., Plangger, K., de Ruyter, K., & Grewal, D. (2020). Understanding the strategic consequences of customer privacy concerns: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Retailing, 96(4), 458–473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2020.05.007

- Orehek, E., Forest, A. L., & Barbaro, N. (2018). A people-as-means approach to interpersonal relationships. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 13(3), 373–389. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617744522

- Pantano, E., & Gandini, A. (2017). Exploring the forms of sociality mediated by innovative technologies in retail settings. Computers in Human Behavior, 77, 367–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.02.036

- Park, C. W., MacInnis, D. J., Priester, J., Eisingerich, A. B., & Iacobucci, D. (2010). Brand attachment and brand attitude strength: Conceptual and empirical differentiation of two critical brand equity drivers. Journal of Marketing, 74(6), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.74.6.1

- Ramaseshan, B., & Stein, A. (2014). Connecting the dots between brand experience and brand loyalty: The mediating role of brand personality and brand relationships. Journal of Brand Management, 21(7–8), 664–683. https://doi.org/10.1057/bm.2014.23

- Rehan, H., Amna, A., & Bilal, M. K. (2022). The impact of brand equity, status consumption, and brand trust on purchase intention of luxury brands. Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 2034234. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2034234

- Rigdon, E. E., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2017). On comparing results from CB-SEM and PLS-SEM: Five perspectives and five recommendations. Marketing: ZFP–Journal of Research and Management, 39(3), 4–16. https://doi.org/10.15358/0344-1369-2017-3-4

- Roggeveen, A. L., Grewal, D., Karsberg, J., Noble, S. M., Nordfält, J., Patrick, V. M., & Olson, R. (2021). Forging meaningful consumer-brand relationships through creative merchandise offerings and innovative merchandising strategies. Journal of Retailing, 97(1), 81–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2020.11.006

- Rotageek, (2021). How to improve customer experience in retail stores in 2021. https://www.rotageek.com/blog/customer-experience-inretail#:~:text=A%20retail%20customer%20experience%20is,experience%2C%20purchasing%20and%20the%20packaging.

- Roy, S. K., Gruner, R. L., & Guo, J.(2022). Exploring customer experience, commitment, and engagement behaviours. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 30(1), 45–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965254X.2019.1642937

- Sarstedt, M., Hair, J. F., Cheah, J. H., Becker, J. M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). How to specify, estimate, and validate higher-order constructs in PLS-SEM. Australasian Marketing Journal, 27(3), 197–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ausmj.2019.05.003

- Shaikh, A. A., Karjaluoto, H., & Chinje, N. B. (2015). Continuous mobile banking usage and relationship commitment–A multi-country assessment. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 20(3), 208–219. https://doi.org/10.1057/fsm.2015.14

- Siebert, A., Gopaldas, A., Lindridge, A., & Simões, C. (2020). Customer experience journeys: Loyalty loops versus involvement spirals. Journal of Marketing, 84(4), 45–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022242920920262

- Sirgy, M. J. (1985). Using self-congruity and ideal congruity to predict purchase motivation. Journal of Business Research, 13(3), 195–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/0148-2963(85)90026-8

- Sirgy, M. J., Grewal, D., Mangleburg, T. F., Park, J. O., Chon, K. S., Claiborne, C. B., Johar, J. S., & Berkman, H. (1997). Assessing the predictive validity of two methods of measuring self-image congruence. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 25(3), 229–241. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070397253004

- Tan, T. M., Salo, J., Juntunen, J., & Kumar, A. (2018). The role of temporal focus and self-congruence on consumer preference and willingness to pay: A new scrutiny in branding strategy. European Journal of Marketing, 53(1), 37–62. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-04-2017-0303

- Teixeira, J., Lio, P., Nuno, J. N., Leonel, N., Raymond, P. F., & Larry, C. (2012). Customer experience modeling: From customer experience to service design. Journal of Service Management, 23(3), 362–376. https://doi.org/10.1108/09564231211248453

- Turunen, L. L. M., & Pöyry, E. (2019). Shopping with the resale value in mind: A study on second‐hand luxury consumers. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 43(6), 549–556. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12539

- Van Dat, T., & Ngoc, T. T. N. (2022). Investigating the relationship between brand experience, brand authenticity, brand equity, and customer satisfaction: Evidence from Vietnam. Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 2084968. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2084968

- Van Nguyen, A. T., McClelland, R., & Thuan, N. H. (2022). Exploring customer experience during channel switching in omnichannel retailing context: A qualitative assessment. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 64, 102803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102803

- Van Tonder, E., & Petzer, D. J.(2018). The interrelationships between relationship marketing constructs and customer engagement dimensions. The Service Industries Journal, 38(13–14), 948–973.

- Verhoef, P., Lemon, K., Parasuraman, A., Roggeveen, A., Tsiros, M., & Schlesinger, L. (2009). Customer experience creation: Determinants, dynamics and management strategies. Journal of Retailing, 85(1), 31–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2008.11.001

- Walter, U., Edvardsson, B., & Öström, Å. (2010). Drivers of customers’ service experiences: A study in the restaurant industry. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, 20(3), 236–258. https://doi.org/10.1108/09604521011041961

- Wanwisa, P., Chutima, R., & Narissara, S. (2022). Customer experience and commitment on eWOM and revisit intention: A case of Taladtongchom Thailand. Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 2108584. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2108584

- Wijnands, F., & Gill, T. (2020). ‘You’re not perfect, but you’re still my favourite.’ brand affective congruence as a new determinant of self-brand congruence. Journal of Marketing Management, 36(11–12), 1076–1103. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2020.1767679

- Wilbert, M., Charles, M., & Zororo, M. (2022). The effect of customer experience, customer satisfaction and word of mouth intention on customer loyalty: The moderating role of consumer demographics. Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 2082015. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2082015

- Xie, L. S., Peng, J. M., & Huan, T. C. (2014). Crafting and testing a central precept in service-dominant logic: Hotel employees’ brand-citizenship behavior and customers’ brand trust. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 42, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2014.05.011

- Xie, L., Poon, P., & Zhang, W. (2017). Brand experience and customer citizenship behavior: The role of brand relationship quality. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 34(3), 268–280. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCM-02-2016-1726

- Yi, Y., & Gong, T. (2008). The electronic service quality model: The moderating effect of customer self‐efficacy. Psychology & Marketing, 25(7), 587–601. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20226

- Yi, Y., & Gong, T. (2013). Customer value co-creation behavior: Scale development and validation. Journal of Business Research, 66(9), 1279–1284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.02.026

- Yim, C. K., Tse, D. K., & Chan, K. W. (2008). Strengthening customer loyalty through intimacy and passion: Roles of customer–firm affection and customer–staff relationships in services. Journal of Marketing Research, 45(6), 741–756. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.45.6.741

- Ying, S., Sindakis, S., Aggarwal, S., Chen, C., & Su, J. (2021). Managing big data in the retail industry of Singapore: Examining the impact on customer satisfaction and organizational performance. European Management Journal, 39(3), 390–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2020.04.001

- Zemack-Rugar, Y., Moore, S. G., & Fitzsimons, G. J. (2017). Just do it! Why committed consumers react negatively to assertive ads. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 27(3), 287–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2017.01.002