Abstract

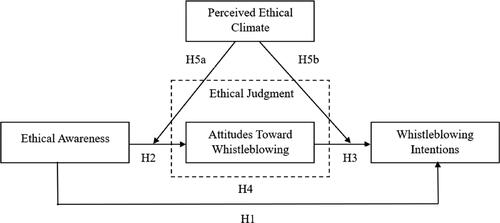

The purpose of this study is to examine the relationship between ethical awareness, ethical judgment, and whistleblowing intention using, as a framework, the integrated ethical decision-making model (I-EDM model). Additionally, this study integrates one of the variables within the theory of planned behavior (TPB), namely attitude, into the ethical judgment stage of the I-EDM model and investigates whether the perceived ethical climate influences every step of the whistleblowing decision-making process. Using a quantitative approach, the researchers collected data using a survey, and successfully gathered 193 responses from the internal auditors of public universities in Indonesia. We found that ethical awareness influences whistleblowing intentions, and the attitude toward whistleblowing mediates the influence of ethical awareness on internal whistleblowing. Further, we found that the perceived ethical climate moderates the relationship between ethical awareness and the attitude toward whistleblowing, as well as the connection between the attitude toward whistleblowing and the external whistleblowing intention. These findings provide support for the I-EDM model, the TPB, and the ethical climate theory. These findings suggest the importance of enhancing auditors’ ethical awareness and positive attitude toward whistleblowing, as well as improving the ethical climate within organizations.

1. Introduction

Fraud is a global problem, occurring in all parts of the world in both developed and developing countries, and it has a negative impact on various types and sizes of organizations, including public sector organizations. According to the survey by the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE) in 2022, public sector organizations such as those for government and public administration have the second-highest number of cases of loss due to fraud, after corruption through bribery, conflicts of interest and extortion.

Fraud in an organization can be detected at an early stage if members of that organization immediately report any indications of ongoing fraudulent behavior. One of the ways is by a whistleblowing mechanism, which has been proven to be effective in exposing fraud (Alleyne et al., Citation2013; Culiberg & Mihelič, Citation2017). Whistleblowing is defined as the disclosure by an organization’s members (former or current) of illegal, immoral, or illegitimate practices, carried out under the control of their employers, to persons or organizations that may be able to affect action (Near & Miceli, Citation1985). A survey conducted by the ACFE in 2022 showed that 55 percent of whistleblowers are employees. However, employees who carry out whistleblowing often run the risk of being fired (Archambeault & Webber, Citation2015), being harassed by co-workers or superiors (Sachdeva & Chaudhary, Citation2022), or facing the dilemma between being considered a hero by society versus a traitor by their organization and co-workers (Keenan, Citation1990; Lindblom, Citation2007; Teo & Caspersz, Citation2011). All of these hazards are more likely to occur with internal rather than external whistleblowers (Read & Rama, Citation2003), which can lead to employee reluctance to report fraud.

The Ethics Compliance Initiative (Citation2019) found nearly one-half (45 percent) of employees observed misconduct in their workplace, but slightly more than one-third (33 percent) remained silent. This underlies the importance of research, not only to determine the factors that can increase the whistleblowing intentions of members of the organization, but also how someone who finds wrongdoing can make the decision to report it (blow the whistle).

Culiberg and Mihelič (Citation2017) stated that whistleblowing is an ethical dilemma, and an individual must go through a series of ethical decision-making processes to arrive at the act of whistleblowing. Although whistleblowing studies have been carried out extensively, their focus has been on the individual stages of the process, such as the intention stage (Brink et al., Citation2017; Kaplan et al., Citation2009; Nuswantara, Citation2023; Owusu et al., Citation2020; Robertson et al., Citation2011) or the positive relationship between the judgment and intention stages (Brown et al., Citation2016; Liyanarachchi & Adler, Citation2011; Mesmer-Magnus & Viswesvaran, Citation2005; Sarikhani & Ebrahimi, Citation2022; Zhang et al., Citation2009a), and they have ignored the other two stages, namely ethical awareness and the whistleblowing behavior itself (Culiberg & Mihelič, Citation2017). It is still unclear how the whole process proceeds (Craft et al., Citation2013). Most of the previous research, especially the research conducted by Latan et al. (Citation2019) that examined whistleblowing as an ethical decision-making process, was conducted in the private sector and very little attention has been directed at the public sector.

The environment and characteristics of public sector organizations, which differ from those of private organizations, result in different whistleblowing processes depending on the type of organization (Latan et al., Citation2023; Miceli & Near, Citation2013) and the application of whistleblowing legislation (Previtali & Cerchiello, Citation2018). The losses suffered by public sector organizations will have a broad impact on society, because the public sector plays an important role in the economy of every country and affects the socio-political structure of the country. The disclosure of fraud is one of the mechanisms that can help improve public sector services to the community (Miceli & Near, Citation2013) and is an important part of openness and accountability to the public (Quayle, Citation2021).

In this paper, we attempt to respond by expanding the whistleblowing literature by examining the whistleblowing process for internal auditors in public sector organizations, with a focus on higher education organizations. In particular, the aim of this study is to examine the relationship between ethical awareness, ethical judgment, and the whistleblowing intention in the ethical decision-making process, and the situational context that can influence each stage based on the I-EDM model (Schwartz, Citation2016). This study also integrates one of the dimensions of the TPB, namely the attitude toward whistleblowing, into the ethical judgment stage.

The study was motivated by several considerations. First, higher education institutions are public sector organizations that play an important role in creating quality human resources that ultimately contribute greatly to local, national and global development (Chankseliani et al., Citation2021). Fraud in higher education institutions can lower the quality of higher education and greatly affect the quality of the human resources they produce. With the increasing demands of good governance and risk management in higher education institutions in the world, and especially in Indonesia, the role of university internal auditors is very important; they play a frontline role in ensuring the achievement of good governance and good risk management (Dzikrullah et al., Citation2020; Susmanschi, Citation2012), especially in their efforts to prevent fraud such as corruption (Rahayu et al., Citation2020) in higher education institutions.

Internal auditors occupy a unique position in an organization, because they have a deep understanding of that organization and its internal control environment. This provides an opportunity for them to be aware of any signs of fraud in an organization beforehand (Lee et al., Citation2021). Internal auditors are usually more sensitive to unethical actions, but they are also more worried than external auditors about the consequences of whistleblowing, such as losing their jobs or being ostracized by the organization (Read & Rama, Citation2003). Accounting research has, until now, highlighted more about the determinants of the whistleblowing intention in auditors working in the private sector: for example, Arnol Sr. and Ponemon (Citation1991), Kaplan and Whitecotton (Citation2001), Brennan and Kelly (Citation2007), Taylor and Curtis (Citation2013), Latan et al., (Citation2019), Boo et al., (Citation2021), while very little is known about the determinants of the whistleblowing intentions for auditors working in public sector organizations, especially those in higher education institutions.

Second, a review of the literature on whistleblowing, conducted by Culiberg and Mihelič (Citation2017), and the literature on whistleblowing in the accounting field by Gao and Brink (Citation2017) showed that research still lacks a focus on whistleblowing as an ethical decision-making process. Furthermore, Culiberg and Mihelič (Citation2017) were critical of how research into whistleblowing up till then had focused more on the relationship between ethical judgment and whistleblowing intentions, while ignoring other stages in the ethical decision-making process, namely ethical awareness and ethical behavior. This research responds to this by examining how the process of whistleblowing occurs as an ethical decision-making (EDM) process, and the situational context that influences the EDM process, based on the integrated ethical decision making (I-EDM) model proposed by Schwartz (Citation2016). Ethical awareness plays an important role in ethical decision-making (whistleblowing). An ethical decision-making process begins with the emergence of an awareness of experiencing an ethical dilemma, which then leads to the stage of ethical judgment when individuals consider the ethical choices that must be taken; the absence of ethical awareness in an individual can lead to unconscious unethical actions (Schwartz, Citation2016).

Third, Uys (Citation2014) pointed out the importance of integrating various approaches in facilitating the assessment of whistleblowing intentions. This research responds to Uys’s (Citation2014) call by integrating the I-EDM model (Schwartz, Citation2016) and the TPB proposed by Ajzen (Citation1991), especially the attitude toward whistleblowing in the judgment stage of the ethical decision-making process. The attitude toward whistleblowing is an individual’s assessment of whether whistleblowing is an ethical, beneficial action or not; the more a person has a positive view of a particular behavior (whistleblowing), the more likely he/she is to commit that behavior. At the judgment stage, individuals form their judgments about whether whistleblowing is an ideal ethical choice (Zhang et al., Citation2009b). This research differs from previous research conducted by Latan et al. (Citation2019) which examined the influence of rational and nonrational factors from the I-EDM model on the whistleblowing intention.

Fourth, Near & Miceli (Citation1985) showed that the organizational climate is a factor that also plays an important role in increasing the effectiveness of whistleblowing. Whistleblowing intentions are influenced by individuals’ perceptions of organizational support, and whether the organization is willing to change the improper actions. Therefore, it is very important to study how the organizational climate can increase whistleblowing (Gao & Brink, Citation2017). An ethical climate represents an organizational climate that can encourage or prevent the disclosure of fraud.

Consequently, this paper seeks to make the following contributions to the existing literature. First, our research provides empirical evidence that expands the understanding of the factors that influence the intention to commit whistleblowing, from the point of view of the ethical decision-making process. Whistleblowing, as an ethical action, does not just simply happen but rather goes through a series of stages in the ethical decision-making process, which include ethical awareness, ethical judgment, and intentions to behave ethically, as well as situational factors that affect each of these stages. The results of this research answer the call of Culiberg and Mihelič (Citation2017) and provide support for the I-EDM model developed by Schwartz (Citation2016). Second, by integrating one of the determinants of intention from the theory of planned behavior (TPB), namely the attitude toward whistleblowing, which was proposed by Ajzen (Citation1985, Citation1991) at the judgment stage of the I-EDM model (Schwartz, Citation2016), our study responds to Uys’s (2016) call to integrate different approaches in assessing the whistleblowing intention. This study provides empirical evidence that the attitude toward whistleblowing plays an important role in the whistleblowing process; the more an auditor has a positive view of whistleblowing, the more likely it is that he/she intends to blow the whistle. Third, it uses the perceived ethical climate in a situational context, as proposed by Schwartz (Citation2016). The perceived ethical climate itself has not been widely researched in the existing literature on whistleblowing in the field of accounting. Our study demonstrates the important role of the perceived ethical climate in the whistleblowing process. Auditors who have high ethical awareness, supported by a positive perception of the ethical climate that applies within their organization, will assess whistleblowing as a useful, ethical, and appropriate behavior to engage in. Fourth, this research contributes to the methodology by expanding the scope of the research subjects in its examination of the intentions of internal auditors in the public sector, particularly in universities, and by expanding the scope of whistleblowing research through the provision of evidence from Indonesia, so that it can further increase the generalization of the research results.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 describes the background of the study. Section 3 reviews the theoretical literature, while Section 4 reviews the empirical literature and develops the hypotheses. Section 5 describes the research design. Section 6 presents the empirical results and discussions. Section 7 concludes the study.

2. Background

State universities in Indonesia were originally higher education institutions. Their management came under the coordination of the Ministry of Education and Culture. However, since the issuance of Law Number 12 of 2012 concerning Higher Education, universities in Indonesia have been encouraged to achieve full autonomy in the implementation of higher education, managed through good governance, which is intended to achieve its vision and goals as a professional institution (Risanty & Kesuma, Citation2019). One of the criteria is public accountability.

The facts show that public accountability has not been optimally achieved, because higher education in Indonesia is one of the sectors that is harmed by corruption. In Indonesia, during the period from 2016 to 2021, universities accounted for 49 percent of the total state losses caused by corruption in the education sector, namely IDR789.8 billion, through various modes including corruption in the procurement of goods and services, corruption of grant funds, research funds and scholarships (Indonesian Coruption Watch, Citation2021). Although there has been a lot of fraud in higher education institutions, only a few cases have been publicized, which means they can be followed up by the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK).

This research tested the I-EDM model on the internal auditors of state universities in Indonesia, because internal auditors have a unique position in such organizations and play an important role in realizing the good governance of higher education institutions. Their deep understanding of the organization and its internal environment means they can recognize fraud in the organization early on (Lee et al., Citation2021). In carrying out their duties, internal auditors may encounter the whistleblowing process several times throughout their careers, such as assisting in the process of investigating whistleblower reports or providing advice to potential whistleblowers, so they can gain access to sensitive information, which means they may be in a position to report fraud themselves (Archambeault & Webber, Citation2015; Quayle, Citation2021). Apart from that, internal auditors at state universities in Indonesia are unique because they carry out two tasks, namely their main task as lecturers and also as employees who are given additional duties as internal auditors, so it is very likely that they will experience a conflict of interest. This can lead to an ethical dilemma.

This research chose the Indonesian context because, to date, research into whistleblowing has been mostly carried out in developed countries (see the literature review conducted by Gao and Brink [Citation2017], and Lee and Xiao [Citation2018] for the private sector, and Kang’s (Citation2023) research on the public sector), but little has been done in developing countries (Latan et al., Citation2018), especially in Indonesia. Whistleblowing research in Indonesia, especially in public sector organizations, is still limited to testing the variables that affect whistleblowing intentions, including authentic leadership (Anita et al., Citation2021; Anugerah et al., Citation2019), the attitude to whistleblowing (Nurhidayat & Kusumasari, Citation2019) and the perceived organizational protection (Latan et al., Citation2023).

The 2022 ACFE survey shows that the Asia Pacific region ranks third for the largest number of fraud cases in the world, and Indonesia ranks fourth after Australia, China and Malaysia. In the context of the high level of fraud that occurs in the Asia Pacific region, especially in Indonesia, and in view of the limited evidence from the public sector in Indonesia, it is increasingly urgent that research in the Indonesian context is conducted.

3. Theoretical literature review

Three theoretical frameworks are applied in this study, namely, the integrated ethical decision-making (I-EDM) model, the theory of planned behavior (TPB) and the ethical climate theory.

3.1. Integrated ethical decision-making (I-EDM) model

Schwartz (Citation2016) developed an I-EDM model to overcome the weaknesses in previous EDM models, which had assumed that ethical behavior depends on the particular individual facing an ethical dilemma, and the situational context when the individual faced it. At the basic level, there are two main components, (1) a process based on the four stages of EDM, which are: (i) awareness, (ii) judgment, (iii) intention, and (iv) action or behavior (Rest, Citation1986); and (2) factors or variables that influence the EDM process based on the interactionist model (Trevino, Citation1986), namely individual factors and the situational context.

In the context of whistleblowing, Culiberg and Mihelič (Citation2017) suggested analyzing whistleblowing from the point of view of ethical decision-making, which consists of four stages: (1) it starts with an individual awareness that fraud that has negative consequences for others is happening, (2) individuals evaluate whether whistleblowing is ethical behavior or not, (3) the formation of intention, namely when the individual decides whether he or she will engage in whistleblowing, (4) actually engaging in whistleblowing behavior, or not, in accordance with his or her intention. Moral awareness encourages decision makers to make moral judgments about what constitutes right or wrong behavior in a given situation, which in turn encourages individuals to establish moral intentions to perform moral behavior, or not (Haines et al., Citation2008). At the judgment stage, when a person realizes that there is a moral problem, he or she must make a moral judgment (Jones, Citation1991) to choose among the various alternatives and further establish his or her moral intentions.

Using the classical EDM theory (Rest, Citation1986) and the I-EDM model (Schwartz, Citation2016), prior studies that examined the influence of ethical awareness and ethical judgment on the intention to perform ethical behavior have shown that these two variables affect the intention to carry out ethical behavior. For example, research conducted by Rottig et al. (Citation2011) and Haines et al. (Citation2008) shows that individual moral awareness and perceptions of the importance of ethical issues affect moral judgments and moral intentions. Kim and Loewenstein (Citation2020) show that moral awareness, either spontaneously or with encouragement, can capture important aspects of the ethical decision-making process. Research in the context of whistleblowing was conducted by Valentine and Godkin (Citation2019) and their results showed that the recognition and perception of the importance of ethical issues were positively related to whistleblowing intentions. Research by Latan et al. (Citation2019) showed that ethical judgment influenced auditors’ intentions to whistleblow.

3.2. Theory of planned behavior

The theory of planned behavior (TPB) has been demonstrated to be an effective theoretical framework for predicting ethical and unethical behavior intentions (Buchan, Citation2005; McMillan and Conner, Citation2003; Randall and Gibson, Citation1991), particularly for predicting whistleblowing intentions (Park & Blenkinsopp, Citation2009). The main factor in this theory is the individual’s intention to engage in certain behaviors. Intention is an indicator of motivation that influences a person’s behavior, indicating the extent to which a person is willing to plan, try, and make the effort to realize that behavior. Brown et al. (Citation2016) developed a judgment model based on the TPB, and supported this with the fraud triangle theory to provide a more complete perspective on the intention to engage in whistleblowing. Brown et al. (Citation2016) stated that the TPB provides an explanation of the factors or elements that contribute to individual judgment.

One of the determinants of intention that was proposed by the TPB (Ajzen, Citation1985, Citation1991), which determines a person’s intention to behave, is the attitude toward behavior. The attitude toward behavior indicates the extent to which individuals perceive a particular behavior as acceptable (beneficial), or not (Ajzen, Citation1991). In relation to whistleblowing, individual attitudes can have positive and negative effects on intentions and behavior, depending on the individual’s personal views. If the individual has a positive attitude toward the whistleblowing action, then this will have a positive impact on that individual’s intention to disclose fraud, and vice versa. Using the TPB, previous research using the attitude toward whistleblowing as an independent variable to the intention to do whistleblowing include studies by Park and Blenkinsopp (Citation2009), Trongmateerut and Sweeney (Citation2013), Brown et al. (Citation2016), Alleyne et al. (Citation2019), Arkorful (Citation2022) and Zhang et al. (Citation2022). The results all show a positive influence of the attitude toward whistleblowing on whistleblowing intentions. In this research we use the attitude toward whistleblowing as a mediating variable that links ethical awareness with the intention of blowing the whistle in the judgment stage, based on the I-EDM model. The ethical awareness that an individual has will cause the individual to recognize ethical dilemmas when discovering fraud, which then leads to the judgment stage to assess whether whistleblowing is a fair, ethical, and beneficial action or not, and ultimately affects the individual’s intention to whistleblow.

3.3. Ethical climate theory

Another theory used in this research is the ethical climate theory, which was developed by Victor and Cullen (Citation1988). This theory is used in this research to represent one of the situational contexts of the I-EDM model, namely the organizational context. An ethical climate is defined as the prevailing perceptions of typical organizational practices and procedures that have an ethical content (Victor and Cullen, Citation1988:101), as well as the perceptions of what constitutes correct behavior, which then becomes a psychological mechanism through which ethical issues are managed (Martin & Cullen, Citation2006). The ethical climate influences decision making and the subsequent behavior in response to ethical dilemmas.

An ethical climate includes the employees’ perceptions of behavior that is seen as being ethical, or unethical, within an organization (Kaptein, Citation2011). This concept was developed because individual characteristics cannot fully explain the factors that influence ethical decision-making in the organizational context (Buchan, Citation2005), and also because individuals often seek guidance from outside themselves when faced with ethical dilemmas. Therefore, organizations can influence the relationship between individual understanding and behavior through reinforcing ethical behavior, organizational norms, and managerial responsibility (Trevino Citation1986).

Whistleblowing is a reporting mechanism that helps management identify unethical situations and behavior, and thus take corrective action. Employees’ positive perceptions of their organization can encourage them to report fraud that they encounter, meaning that the problem can be resolved within the organization without the need to involve outside parties (Aydan & Kaya, Citation2018). When an employee or member of an organization knows about fraud and feels that the organization supports ethical behavior (for example through norms, rules, or its leadership’s appreciation), then that individual will be more motivated to engage in whistleblowing.

Previous research using the ethical climate theory to explain ethical behavior, especially whistleblowing, has shown that, directly or indirectly, the ethical climate influences a person’s intention to report fraud (Ahmad et al., Citation2014; Nuswantara, Citation2023; Potipiroon & Wongpreedee, Citation2021; Rothwell & Baldwin, Citation2006, Citation2007; Smaili, Citation2023; Zhou et al., Citation2018).

4. Empirical literature review and hypotheses development

4.1. Whistleblowing as an ethical decision-making process

Whistleblowing is a form of ethical decision-making (EDM) (Culiberg & Mihelič, Citation2017). According to the I-EDM model developed by Schwartz (Citation2016), there are four stages of ethical decision-making, namely the awareness, judgment, intention, and behavior. Ethical awareness is the awareness possessed by individuals at a certain point in time when faced with an ethical dilemma that requires a decision or action that may affect their own interests, or those of others, in a way that may conflict with one or more of the moral standards (Butterfield et al., Citation2000).

The ethical awareness stage is a critical one in the EDM process (Schwartz, Citation2016), because when individuals are not aware of the moral or ethical nature implied in a particular situation, it can lead to unintentional ethical or unethical behavior (Tenbrunsel & Smith-Crowe, 2008). At the awareness stage, individuals must recognize or feel that they are facing an ethical dilemma.

Previous research has shown that moral awareness influences the intention to behave ethically, both directly and indirectly, including in marketing services (Singhapakdi et al., Citation1999), consumer attitudes (Ang et al., Citation2001; De Matos et al., Citation2007), organizational ethical infrastructure (Rottig et al., Citation2011), and ethics education (Rangkuti et al., Citation2022; Tomlin et al., Citation2021).

In the whistleblowing process, the first step occurs when the individual has sufficient ethical awareness to identify an error, or observes illegal or unethical activity within the organization (Smaili, Citation2023) that creates an ethical dilemma. In the case of auditing, auditors who have ethical awareness can distinguish between normal and unusual types of errors, because unusual errors can be a sign of fraud, ethical violations, or illegal acts (Arnol Sr. & Ponemon, 1991). Auditors who are aware of ethical problems or dilemmas have the potential to be involved in the EDM process, one element of which is the ethical intention stage (whistleblowing intention).

Based on the explanation above, the following hypothesis has been formulated:

Ha1: Ethical awareness has a positive effect on the whistleblowing intention.

According to Schwartz (Citation2016), ethical judgment is the determination of the most ethically appropriate action among various alternatives. Fishbein and Ajzen (Citation1975) explained that judgments are formed through evaluating beliefs. Beliefs are defined as: ‘the subjective probability of the relationship between an object of belief and other objects, values, concepts, or attributes’. These are obtained through observation of, conclusions about, and communication with, other people. One of the three beliefs that are the focus of the TPB is behavioral beliefs (Ajzen, Citation1985, Citation1991), which is assumed to influence people’s attitudes toward whistleblowing.

Brown et al. (Citation2016) developed a whistleblowing judgment model based on the theory of planned behavior (TPB) and the fraud triangle theory, and argued that the TPB provides an explanation of the factors or elements that contribute to individual judgment. One such factor is the attitude toward whistleblowing. This attitude toward a type of behavior refers to the extent to which a person has a favorable or unacceptable evaluation or assessment of the behavior (Ajzen Citation1991:188). At this judgment stage, a person forms judgments about whether or not disclosing fraud is an ideal choice (Zhang et al., Citation2009a).

In the whistleblowing process, after an individual realizes that there is a mistake that creates an ethical dilemma, he or she forms an opinion about what should be done by making a judgment about whether or not blowing the whistle is the correct, ethical, profitable, and useful action. Auditors who are aware of fraud that creates ethical problems or dilemmas will then evaluate whether or not whistleblowing is an ideal choice, based on their attitude or assessment of the behavior.

Based on the explanation above, the following hypothesis has been formulated:

Ha2: Ethical awareness has a positive effect on the attitude toward whistleblowing at the ethical judgment stage.

Research conducted by Buchan (Citation2005), which examined the factors that influence public accountants’ ethical behavioral intentions, found that the attitude toward whistleblowing influenced the intention to engage in ethical behavior. In particular, research into whistleblowing has found that the attitude toward whistleblowing is one of the factors that increases a person’s intention to disclose acts of fraud (Alleyne et al., Citation2019; Arkorful, Citation2022; Brown et al., Citation2016; Latan et al., Citation2018; Owusu et al., Citation2020; Park & Blenkinsopp, Citation2009; Trongmateerut & Sweeney, Citation2013; Zhang et al., Citation2022).

An auditor, when discovering fraud such as fraudulent financial statements, the misappropriation of assets, or corruption, will most likely intend to report it when the individual has a positive assessment of whistleblowing behavior.

Based on this explanation, we developed the following hypothesis:

Ha3: The attitude toward whistleblowing, at the ethical judgment stage, has a positive effect on the whistleblowing intention.

If individuals (auditors) experience a whistleblowing dilemma and judge that blowing the whistle is an acceptable, fair, ethical, and appropriate choice, then they will be more likely to have the intention of engaging in whistleblowing.

Based on the explanation above, the following hypothesis has been formulated:

Ha4: Ethical awareness has a positive effect on the whistleblowing intention, through the attitude toward whistleblowing, at the ethical judgment stage.

4.2. The moderating effect of ethical climate on the relationships between ethical awareness, ethical judgment, and whistleblowing intention

One of the situational factors that can influence each stage of ethical decision-making offered by the I-EDM model (Schwartz, Citation2016) is the organizational environment, especially the organizational ethical infrastructure (Tenbrunsel et al., Citation2003; Treviño et al., Citation2006). An organization’s ethical infrastructure can be represented by its ethical culture (Treviño et al., Citation1998) and ethical climate (Victor & Cullen, Citation1988). An ethical climate is the prevailing perception of an organization’s typical practices and procedures that have ethical content (Victor & Cullen, Citation1988), which influences the decision making and subsequent behavior in response to ethical dilemmas. Organizations with a strong ethical culture and climate will encourage their members to be more sensitive and concerned about ethical issues, and act in accordance with the ethical order, according to the organization (Ethics Resource Centre, Citation2014). Previous research conducted by Verbeke et al. (Citation1996) found that the ethical climate has a positive influence on ethical decision-making. Ford and Richardson (Citation1994) showed that the greater the ethical climate was within an organization, the greater was the likelihood that individuals would possess ethical beliefs and engage in ethical decision-making behavior.

Culiberg & Mihelič (Citation2017) stated that situational factors (e.g. the ethical climate) have been demonstrated to have more explanatory power and consistency, compared to individual factors, in fraud disclosure decisions (Cassematis & Wortley, Citation2013; Culiberg & Mihelič, Citation2017; Vadera et al., Citation2009). Furthermore, Nuswantara (Citation2023) stated that the dimensions of the ethical climate are signals of the environment that increase positive interpretations of the organizational support and protection of ethical behavior, such as whistleblowing. Previous research, for example by Cheliatsidou et al. (Citation2023) found that the absence of a strong ethical climate causes government employees to have negative attitudes toward whistleblowing. Rothwell and Baldwin (Citation2007) found that the ethical climate can predict fraud disclosure intentions and Liu et al. (Citation2018) have shown that an ethical climate moderates the relationship between organizational identification and internal whistleblowing intentions. Research by Nuswantara (Citation2023), showed that although it was indirect, the ethical climate can encourage individuals to blow the whistle.

If individuals (internal auditors) discover fraud and experience a whistleblowing dilemma, and then assess that blowing the whistle would be ethical, fair, correct, and beneficial behavior, and also perceive the organization as having a culture, procedures, and practices that are ethically charged and support ethical actions, then they will be more likely to have the intention to engage in whistleblowing.

Based on the explanation above, the following hypotheses have been formulated:

Ha5: The positive influence of ethical awareness on the attitude toward whistleblowing, at the ethical judgment stage, will increase when the perceived ethical climate is high.

Ha5b: The positive effect of the attitude toward whistleblowing, at the ethical judgment stage, on the intention to engage in whistleblowing will increase when the perceived ethical climate is high.

5. Research design

This research used a quantitative approach, with data being collected using a survey method via two forms of media, namely a link to a questionnaire that was distributed online during the period from August to December 2022. Due to the limited number of responses, printed questionnaires using a convenience sampling (non-probability approach) were also circulated at the annual meeting of the internal auditor units of the state universities in Indonesia on December 12-13, 2022. The respondents to this research were internal auditors at 122 state universities in Indonesia (the full profile of the respondents can be seen in ).

Table 1. Sample selection.

Table 2. Profile of respondents.

Table 3. Measurement of the variables.

The instruments used in this research were adopted from previous researchers. These consisted of scenarios and questions related to the variables to be studied. The instruments were originally in English, and to prevent semantic bias, the researchers performed a back translation (English to Indonesian and back to English). This procedure provides confidence about the semantic equivalence between the target language and the source language (Maneesriwongul & Dixon, Citation2004). The questionnaires that were distributed to the respondents were in Indonesian.

The scenarios used were special cases related to accounting, specifically auditing, and the respondents were asked to assess the actions taken in those scenarios. Scenarios are frequently used in this way in accounting and ethics research (e.g. Alleyne et al., Citation2017; Arnold et al., Citation2013; Curtis & Taylor, Citation2009). The scenarios in this research were based on scenarios used in previous research (Arnold et al., Citation2013; Bagdasarov et al., Citation2016; Curtis & Taylor, Citation2009; Latan et al., Citation2019) and adapted to the circumstances surrounding audits of higher education institutions in Indonesia.

5.1. Data and sample

The population of this study were members of the internal supervisory units (SPI) of 122 state universities in IndonesiaFootnote1, with a total population of 366 internal auditors. The total number of responses came to 197 responses (53.8%), but four responses were incomplete, so they were excluded. Thus, 193 responses were used (see ).

The demographic data about the respondents includes their age, gender, educational level, educational background, position, length of service, and the number of audit training sessions attended can be seen in .

To ensure that there were no differences between the respondents who filled out questionnaires at the beginning and at the end of the data collection period, a nonresponse bias test was carried out. Data analysis in this study used the PLS-SEM (partial least squares) test with WarpPLS 7.0.Footnote3 PLS-SEM has been used extensively over the years, especially in social science disciplines e.g. operations management (Bayonne et al., Citation2020), accounting (Nitzl, Citation2016), and human resource management (Ringle et al., Citation2020). We used PLS-SEM in this research because it has various advantages, especially in social science research when there are data distribution problems, a limited number of samples, and complex models due to many indicators (Hair et al., Citation2018, Citation2022; Sarstedt et al., Citation2017).

Testing using PLS-SEM consisted of two stages, namely the analysis of the measurement model and then the structural model’s analysis. The measurement model’s analysis was intended to assess the validity (convergent and discriminant) and reliability of each of the latent construct’s indicators, meanwhile, the structural model’s analysis was intended to assess the model’s quality and test the research hypotheses (Hair et al., Citation2011, Citation2018).

5.2. Common method bias

We controlled for common method bias in this research through two methods, namely procedural and statistical methods (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). First, we ensured the anonymity of the respondents because considering the disclosure of fraud within an organization is a sensitive topic. Second, we used a full collinearity test by considering the value of variance inflation factors (VIFs) (Kock, Citation2015). Based on , it can be seen that the value of the average variance inflation factors (AVIFs) was 1.350; this was less than 3.3, so the model was free from common method bias (Kock, Citation2015).

5.3. Measurement of variables

5.3.1. Dependent variable

The whistleblowing intention is the intention of organization members (former or current) to disclosure illegal, immoral, or illegitimate practices under the control of their employers, to persons or organizations that may be able to effect action. The whistleblowing intention was measured using questions adopted from Park and Blenkinsopp (Citation2009). Based on the validity test, one item had to be removed because the loading factor was below 0.7 (Hair et al., Citation2011).

5.3.2. Independent variables

Ethical awareness is the awareness possessed by individuals, at a certain point in time, when faced with an ethical dilemma that requires a decision or action that may affect their own interests, or those of others, in a way that may conflict with one or more moral standards. Ethical awareness was measured using two question items adapted from Arnold et al. (Citation2013). Based on the results of the validity test, the two items had to be removed because their loading factors were below 0.7 (Hair et al., Citation2011).

5.3.3. Mediating variable

The attitude toward behavior is the extent to which individuals perceive whistleblowing behavior as acceptable (beneficial), and ethical, or not. The attitude toward whistleblowing was measured using an instrument developed by Park and Blenkinsopp (Citation2009). The results of validity testing showed that all the items could be used because they had loading factor values above 0.7.

5.3.4. Moderating variables

The perceived ethical climate was measured using the instrument used by Tsai and Huang (Citation2008), which was based on the ethical climate questionnaire (ECQ) developed by Victor and Cullen (Citation1988). The validity test results showed that two items had to be deleted because they had loading factors that were below 0.7.

5.3.5. Control variables

The control variables in this study used several demographic variables that have been proven in previous studies to be associated with the intention of auditors to blow the whistle, namely gender (Erkmen et al., Citation2014; Xiao & Wong-On-Wing, Citation2022), age (Erkmen et al., Citation2014; Liyanarachchi & Adler, Citation2011), educational background (Keller et al., Citation2007; Rose et al., Citation2018), tenure (Alleyne et al., Citation2018; Kaptein, Citation2011), and audit training (Lee et al., Citation2016; Yang et al., Citation2013).

The complete results of the measurement of the variables can be seen in below:

Testing the validity and reliability showed that both have been met. Convergent validity was analyzed using the loading factor and AVE. The results showed a loading factor value of >0.7 and an AVE value of >0.5. Meanwhile, the discriminant validity test showed that the indicators of each construct had a higher loading for the construct measured compared to the other constructs, and the AVE root for each construct, shown on the diagonal in bold, had a higher value than the correlation between constructs on non-diagonal elements in the same column (Fornell-Larcker criterion) meaning that the discriminant validity had been met (see ). Besides that, the discriminant validity test also used the heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratio, which was carried out to improve the weaknesses of the cross-loading approach and the Fornell-Larcker criterion. shows that the HTMT ratio value was smaller than 0.9, meaning that discriminant validity was met. The results of the reliability test showed that reliability had been fulfilled, because the values for Cronbach’s alpha and the composite reliability, for each construct, were greater than 0.7 (see ), meaning that all the indicators used in the analysis met the requirements stated by Hair et al. (Citation2011).

Table 4. Results of discriminant validity test using the Fornell-Larcker criterion.

Table 5. Heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT).

Table 6. Results of measurement model’s testing.

6. Empirical results and discussion

6.1. Empirical results

The results of the descriptive statistical tests in showed that the average value of the ethical awareness variable was 5.881. The average value of the internal whistleblowing intention variable was 5.953 and the external whistleblowing variable was 2.885. Meanwhile, the attitude toward whistleblowing variable had an average value of 6.298 and the perceived ethical climate was 5.676.

Table 7. Descriptive statistics.

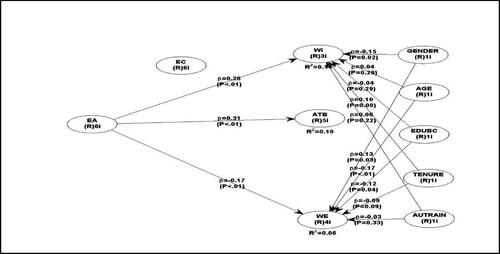

Structural model testing was carried out in order to assess the quality of the model and test the research hypotheses; the results can be seen in .

Table 8. Results of the structural model’s analysis.

The results of the structural model’s analysis in showed that the indicators met the criteria, meaning that the model was fit (appropriate or supported) according to the data. Another indicator was the f2 effect size of the constructs in the model, which were in the weak (0.01) and medium (0.162) categories, and the estimation results of this research model had good predictive validity, because the Q2 value was above zero.

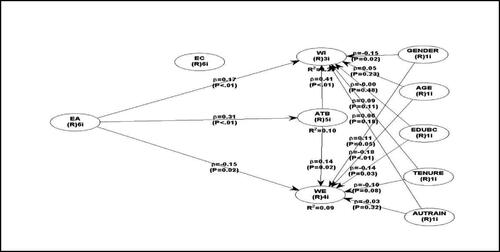

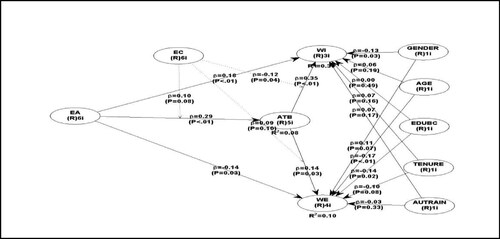

Hypothesis testing was carried out with three tests, namely testing the direct effect, testing the moderating effect, and testing the moderating mediation effect. shows the results of the hypothesis testing. According to the testing of the direct influence, this study succeeded in demonstrating that ethical awareness had a significant positive effect on the whistleblowing intention, especially on the internal whistleblowing intention (p = <0.001), meaning that Hypothesis 1 is supported, and it also had a positive effect on the attitude toward whistleblowing (ATB) (p = <0.001) meaning that Hypothesis 2 is supported ( and ).

Table 9. Results of hypothesis testing.

The results of the mediation test in and and moderating mediation tests in and showed the consistency of the direct influence of ethical awareness and the attitude toward whistleblowing on the whistleblowing intention. Furthermore, the attitude toward whistleblowing was shown to have a positive effect on internal (p = <0.001) and external (p = 0.020) whistleblowing intentions, meaning that Hypothesis 3 is supported. This research also succeeded in demonstrating that the attitude toward whistleblowing at the ethical judgment stage partially mediated the influence of ethical awareness on internal whistleblowing intentions, as indicated by, (1) the direct effect of ethical awareness on internal whistleblowing intentions, with a coefficient of 0.172 and a p-value of 0.053; (2) the attitude toward whistleblowing had a positive effect on internal whistleblowing intentions, with a coefficient of 0.406 and a p-value of <0.001; and (3) there was a decrease in the value of the mediation path coefficient in testing the direct influence of ethical awareness on internal whistleblowing intentions, from 0.282, and significant with a p-value of <0.001, to 0.172 with a p-value of <0.001. These results are also supported by the indirect effect result (coefficient = 0.136; and p-value 0.008), meaning that Hypothesis 4 is supported, especially in terms of the internal whistleblowing intention. In the moderating mediation test, it was demonstrated that a high perceived ethical climate would increase the positive influence of ethical awareness on the attitude toward whistleblowing (p = 0.083) and would also increase the positive influence of the attitude toward whistleblowing on the whistleblowing intention, especially the internal whistleblowing intention (p = 0.102), meaning that hypotheses 5a and 5b are supported.

6.2. Discussion

The results of this study show that ethical awareness has a positive effect, both directly and indirectly, on the whistleblowing intention. Internal auditors at universities, who have high ethical awareness, can not only recognize or feel that they are facing an ethical dilemma but can also make right or wrong judgments about what to do in the context of the situation at hand. This means that they will also consider the duties and functions of internal auditors in helping their organizations to achieve their goals by evaluating the effectiveness of risk management, improving control, and good governance processes (Dzikrullah et al., Citation2020; Susmanschi, Citation2012). This can encourage internal auditors to prefer reporting violations/fraud that they encounter internally, within their organization, rather than reporting it to external parties.

The findings of this research also show that ethical awareness has a positive effect on the attitude toward whistleblowing, which is at the ethical judgment stage or, in other words, ethical awareness has a positive effect on ethical judgment, proving support for the I-EDM model (Schwartz, Citation2016) and the classical EDM model (Rest, Citation1986). In accordance with the ethical decision-making model, this study demonstrates that the awareness possessed by an individual, when faced with an ethical dilemma that requires a certain decision or action, influences his or her judgment in determining his/her next decision, and a person’s lack of moral (or ethical) awareness means a person does not realize (or ignores) the fact that the situation they are experiencing raises ethical judgments that can lead to unconscious unethical behavior (Tenbrunsel & Smith-Crowe, Citation2008). These results are consistent with Singhapadi et al. (Citation1999) who found that moral awareness (perceptions of ethical problems) influences the intention to behave ethically, while Rottig et al. (Citation2011) and Haines et al. (Citation2008) found that ethical awareness is a predictor of ethical judgment and an important element in moral decision-making (Luo et al., Citation2023; Martinez & Jaeger, Citation2016).

The test results show that the attitude toward whistleblowing has a positive effect on internal and external whistleblowing intentions, and mediates the influence of ethical awareness on the internal whistleblowing intention, indicating that internal auditors who judge whistleblowing to be ethical and useful behavior—and capable of preventing the organization from suffering losses due to fraud—will have a stronger intention to report the fraud they encounter. These results give support to the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, Citation1985, Citation1991). This research has also succeeded in demonstrating that the whistleblowing process, as one form of ethical decision-making, must be preceded by individual awareness to recognize ethical issues; then, the individual will advance to the judgment stage by starting to consider alternative decisions that must be made, especially considering whether whistleblowing behavior is an ethical, appropriate, and beneficial action, and then he or she forms an intention to blow the whistle. The results of this research also give support to the whistleblowing judgment model (Brown et al., Citation2016), which states that the attitude toward whistleblowing is at the judgment stage and influences whistleblowing intentions.

The implication is that, when an internal auditor has high ethical awareness and finds a violation, his or her assessment or evaluation of whether whistleblowing behavior is useful behavior—such as preventing greater losses for society, in accordance with the moral values he or she adheres to, or whether it is an obligation for a public employee—will greatly influence the auditor’s intention to engage in whistleblowing. These results are consistent with previous research that found that the attitude toward whistleblowing is one of the factors that increases a person’s intention to disclose acts of fraud (Alleyne et al., Citation2019; Brown et al., Citation2016; Latan et al., Citation2018; May-Amy et al., Citation2020; Owusu et al., Citation2020; Park & Blenkinsopp, Citation2009; Sarikhani & Ebrahimi, Citation2022; Trongmateerut & Sweeney, Citation2013). Research by Rottig et al. (Citation2011) shows that the recognition and perception of the importance of ethical issues and ethical judgment are positively related to whistleblowing intentions. Similarly, Rangkuti et al. (Citation2022) show that ethical judgment is a significant mediator between ethical awareness and fraud reporting intentions, especially whistleblowing (Latan et al., Citation2019).

The test results also show that the perceived ethical climate moderates the influence of ethical awareness on ethical judgment (the attitude toward whistleblowing) and it also moderates the influence of ethical judgment (the attitude toward whistleblowing) on external whistleblowing intentions. This demonstrates the important role of the perceived ethical climate in the whistleblowing process. Auditors who have high ethical awareness, supported by a positive perception of the ethical climate that applies within their organization, will assess whistleblowing as a useful, ethical, and appropriate behavior to engage in. Then, auditors who have a positive assessment of whistleblowing and are supported by a positive perception of the existing ethical climate that applies to their organizations, will be more likely to intend to report the fraud they encounter.

These results show support for the I-EDM model, especially in situational contexts when individuals experience ethical dilemmas (the same individual can behave differently depending on the situation faced or the environment the individual is in). These results also support the ethical climate theory by Victor and Cullen (Citation1988) and are consistent with previous research conducted by Liu et al. (Citation2018), which found that the ethical climate moderates the relationship between organizational identification and internal whistleblowing intentions, as well as research conducted by Nuswantara (Citation2023), which shows that although it is indirect, the ethical climate can encourage individuals to blow the whistle. The situational context, or organizational environment, greatly influences how an individual responds and acts to the ethical dilemmas he or she faces; organizations with a strong ethical climate will generally be able to encourage more employees to be aware of ethical issues and to behave in a way that is considered ethical for the organization (Ethics Resource Centre, Citation2014).

Another interesting result of this research is that internal auditors of universities in Indonesia prefer to report violations internally rather than externally. This has positive implications for the organizations because, by reporting internally, the organizations can immediately respond and follow up on reports in a positive way, so that the auditor does not choose to report to external parties, which can result in greater losses for the reported organizations. Therefore, it is very important for organizations to improve their communication channels for reporting fraud within each organization, by increasing the effectiveness of the fraud-reporting system (WBS system).

6.3. Test of endogeneity and additional analysis

6.3.1. Test of endogeneity

Endogeneity is the process of determining a set of control variables that explain a portion of the variance in the dependent variable (Ebbes et al., Citation2020). Ignoring endogeneity issues can cause test results to be biased or inconsistent. Endogeneity problems can be tested and controlled in PLS-SEM. We used the stochastic instrumental variable (IV) Hausman test procedure, which is intended to test and control endogeneity simultaneously using Warp PLS. In this research we created instrumental variables for WI and WE. As seen in , the path coefficient for the link iV-WI with WI and iV-WE with WE was statistically significant, which means there was an endogeneity problem but this has been controlled by adding instrumental variables iV-WI and iV-WE to the model as control variables (Kock, Citation2022). The test results using instrumental variables (see ) show consistency with the main findings (see ).

Table 10. Testing of endogeneity and consistent PLS results.

6.3.2. Additional analysis

We retested the previous research results using consistent PLS (PLSc), developed by Dijkstra. PLSc was developed to combine both SEM techniques, namely CB-SEM and PLS-SEM, to be able to maintain the flexibility of PLS-SEM in its data distribution assumptions and ability to handle complex models, while obtaining results similar to CB-SEM, because PLSc provides corrections for estimates when PLS is applied to reflective constructs (Dijkstra & Henseler, Citation2015). The test results in show consistency with the main findings, namely, ethical awareness affects the intention to conduct internal whistleblowing and the attitude toward whistleblowing. The results also show the consistency of the role of the attitude toward whistleblowing as mediating ethical awareness and the intention to whistleblow, both internally and externally. Although it shows different results on the influence of the perceived ethical climate at each stage of whistleblowing decision-making.

7. Summary and conclusion

Whistleblowing is one of the effective methods for detecting fraud and has been widely researched. Whistleblowing research, especially in public sector organizations, is important, because differences in the organizational characteristics, and the social and political environment in public sector organizations can cause differences in the whistleblowing process, compared to the private sector (Lee, Citation2020; Miceli & Near, Citation2013). In addition, whistleblowing in public sector organizations has the benefit of saving many lives and influencing the overall well-being of society (Latan et al., Citation2023).

This research examines whistleblowing intentions in public sector organizations by investigating the relationship between ethical awareness, ethical judgment, and the whistleblowing intention in the ethical decision-making process and the situational context that can influence each stage, based on the I-EDM model (Schwartz, Citation2016), on internal auditors of state universities in Indonesia. This study also integrates one of the dimensions of the TPB, namely, the attitude toward whistleblowing, into the ethical judgment stage. According to the findings, this research demonstrates that whistleblowing, as an ethical action, does not just simply happen but rather goes through a series of stages in the ethical decision-making process, which include ethical awareness, ethical judgment, and the intention to behave ethically.

This study provides theoretical implications by confirming the three theories used. First, proving that the ethical awareness of auditors has a positive effect, both directly and indirectly, on whistleblowing intentions. Ethical awareness is an important factor that individuals must have, in order to be able to assess whether a situation contains ethical dilemmas that then influence their judgment in determining the next decision to report, or not report, fraud, and this confirms the I-EDM model. Second, it proves that the auditors’ attitude toward whistleblowing mediates the influence of ethical awareness on the whistleblowing intention. The whistleblowing process begins with individual awareness that recognizes ethical issues, then considers various alternative decisions, especially whether whistleblowing is an ethical, beneficial and appropriate action to take. This then forms the intention to report violations, again confirming the I-EDM model and the TPB. Third, it demonstrates the importance of the role of the perceptual ethical climate in the whistleblowing process. Auditors who have high ethical awareness, supported by positive perceptions about the prevailing ethical climate in the organization, will assess whistleblowing as a useful, ethical and appropriate action to take, which will then encourage them to report fraud. The results of this research show support for the ethical climate theory.

The practical implications for public sector organizations, are first, the recruitment of auditors who have high professional and ethical standards. Second, provide education about whistleblowing, so that employees can better understand the benefits of whistleblowing and know the steps to take when finding fraud in the organization. Third, build an organizational ethics infrastructure that implements formal and informal systems, such as communication systems (i.e., codes of conduct or ethics, missions, performance standards, and compliance or ethics training programs), monitoring systems (i.e., performance appraisals and reporting hotlines), and sanctions systems (i.e., rewards and punishments including evaluations, promotions, salaries, and bonuses), which can assist employees in responding to ethical dilemmas and reporting fraudulent acts. Fourth, organizations create situations that support the internal reporting of violations. This includes making the whistleblowing system (WBS) channels more effective in organizations, for example, by having internal hotlines, providing a positive response to fraud reporting, and guaranteeing the confidentiality of the identity of the reporter.

This study has certain limitations. (1) It only tests a small part of the I-EDM model; future studies could test up to the stage of whistleblowing behavior. Aside from that, future studies could also examine the rationality factors including moral reasoning, moral rationalization, and moral consultation, as well as non-rational factors such as emotions and intuition, which influence the stages of the ethical decision-making process (Schwartz, Citation2016). (2) It only tests the situational context of the I-EDM model; future research could also test the individual factors, such as the moral disposition of an individual’s character. (3) The respondents in this research are the internal auditors of state universities; future research could use respondents who are auditors from other non-profit organizations, for example, private universities or hospitals, as well as respondents from outside of organizations who have the potential to discover fraud, such as external auditors, consumers, distributors, or consultants.

Author contributions statement

Alfiana Antoh was involved in the conception and design, analysis and interpretation of the data, drafting of the paper, revising it critically for its intellectual content, and the final approval of the version to be published.

Mahfud Sholihin was involved in the conception and design, analysis and interpretation of the data, drafting of the paper, revising it critically for its intellectual content and the final approval of the version to be published.

Slamet Sugiri was involved in the conception and design of the work, analysis and interpretation of the data.

Choirunnisa Arifa was involved in the conception and design of the work, analysis and interpretation of the data.

All the authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Ethics approval

We declare that the principles of ethical and professional conduct have been followed and all the participants have read and signed the informed consent before participating in this survey.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

This research is part of the first author’s dissertation.

Data availability statement

Data not available – the participants in this study did not give written consent for their data to be shared publicly.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Alfiana Antoh

Alfiana Antoh is a doctoral student in accounting at the Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Indonesia. Currently, she is a lecturer at the Department of Accounting, Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Cenderawasih, Papua, Indonesia.

Mahfud Sholihin

Mahfud Sholihin is a Professor at Department of Accounting, Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Indonesia. His research interests include behavioral accounting, business ethics and corporate governance, islamic accounting and finance, management accounting and public sector accounting.

Slamet Sugiri

Slamet Sugiri is a Professor at Department of Accounting, Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Indonesia. His research interests include auditing, financial accounting, management accounting, market-based accounting research and public sector accounting.

Choirunnisa Arifa

Choirunnisa Arifa is a Lecturer at Department of Accounting, Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Indonesia. Her research interests include corporate governance, financial accounting, and management accounting.

Notes

1 Based on Higher Education Statistics in Indonesia published by Ministry of Education and Culture (2020).

2 Regulation of the Minister of Education and Culture Number 22 of 2017.

3 The first author (Alfiana Antoh) has obtained an individual Warp PLS license, number X55Y-BXZV-5BBK-ZA0Y-AKYV-BZZY-XZ5A.

References

- Ahmad, S. A., Yunos, R. M., Ahmad, R. A. R., & Sanusi, Z. M. (2014, August). Whistleblowing behaviour: The influence of ethical climates theory. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 164, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.11.101

- Ajzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In J. Kuhl, J. Beckmann (Eds.), Action-control: From cognition to behavior (pp. 11–39). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-69746-3_2

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1922/CDH_2120VandenBroucke08

- Alleyne, P., Wayne, C.-S., Broome, T., & Pierce, A. (2017). Perceptions, predictors and consequences of whistleblowing among accounting employees in Barbados. Meditari Accountancy Research, 25(2), 241–267. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-09-2016-0080.

- Alleyne, P., Haniffa, R., & Hudaib, M. (2019). Does group cohesion moderate auditors’ whistleblowing intentions? Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, 34, 69–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intaccaudtax.2019.02.004

- Alleyne, P., Hudaib, M., & Haniffa, R. (2018). The moderating role of perceived organisational support in breaking the silence of public accountants. Journal of Business Ethics, 147(3), 509–527. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2946-0

- Alleyne, P., Hudaib, M., & Pike, R. (2013). Towards a conceptual model of whistle-blowing intentions among external auditors. The British Accounting Review, 45(1), 10–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2012.12.003

- Ang, S. H., Cheng, P. S., Lim, E. A. C., & Tambyah, S. K. (2001). Spot the difference: Consumer responses towards counterfeits. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 18(3), 219–235. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363760110392967

- Anita, R., Abdillah, M. R., & Zakaria, N. B. (2021). Authentic leader and internal whistleblowers: testing a dual mediation mechanism. International Journal of Ethics and Systems, 37(1), 35–52. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOES-03-2020-0036

- Anugerah, R., Abdillah, M. R., & Anita, R. (2019). Authentic leadership and internal whistleblowing intention: the mediating role of psychological safety. Journal of Financial Crime, 26(2), 556–567. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-04-2018-0045

- Archambeault, D. S., & Webber, S. (2015). Whistleblowing 101. The CPA Journal, 85(7), 60–65. http://www.nysscpa.org

- Arkorful, V. E. (2022). Unravelling electricity theft whistleblowing antecedents using the theory of planned behavior and norm activation model. Energy Policy, 160(October 2021), 112680. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2021.112680

- Arnol, D. F., Sr., & Ponemon, L. A. (1991). Internal auditors’ perceptions of whistle-blowing and the influence of moral reasoning: An experiment. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 10(2), 1–15. http://ezproxy.sunway.edu.my/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=9703212520&site=eds-live&scope=site

- Arnold, D. F., Dorminey, J. W., Neidermeyer, A. A., & Neidermeyer, P. E. (2013). Internal and external auditor ethical decision-making. Managerial Auditing Journal, 28(4), 300–322. https://doi.org/10.1108/02686901311311918

- Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE). (2022). Occupational fraud 2022: A Report to the nations. Association of Certified Fraud Examiners, pp. 1–96.

- Aydan, S., & Kaya, S. (2018). Ethical climate as a moderator between organizational trust & whistle-blowing among nurses and secretaries. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences, 34(2), 429–434. https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.342.14669

- Bagdasarov, Z., Johnson, J. F., MacDougall, A. E., Steele, L. M., Connelly, S., & Mumford, M. D. (2016). Mental models and ethical decision making: The mediating role of sensemaking. Journal of Business Ethics, 138(1), 133–144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2620-6

- Bayonne, E., Marin-Garcia, J. A., & Alfalla-Luque, R. (2020). Partial least squares (PLS) in operations management research: Insights from a systematic literature review. Journal of Industrial Engineering and Management, 13(3), 565–597. https://doi.org/10.3926/jiem.3416

- Boo, E., Ng, T., & Shankar, P. G. (2021). Effects of advice on auditor whistleblowing propensity: Do advice source and advisor reassurance matter? Journal of Business Ethics, 174(2), 387–402. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04615-0

- Brennan, N., & Kelly, J. (2007). A study of whistleblowing among trainee auditors. The British Accounting Review, 39(1), 61–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2006.12.002

- Brink, A. G., Lowe, D. J., & Victoravich, L. M. (2017). The public company whistleblowing environment: Perceptions of a wrongful act and monetary attitude. Accounting and the Public Interest, 17(1), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.2308/apin-51681

- Brown, J. O., Hays, J., & Stuebs, M. T. (2016). Modeling accountant whistleblowing intentions: Applying the theory of planned behavior and the fraud triangle. Accounting and the Public Interest, 16(1), 28–56. https://doi.org/10.2308/apin-51675

- Buchan, H. F. (2005). Ethical decision making in the public accounting profession : An extension of Ajzen’s theory of planned behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 61(2), 165–181. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-005-0277-2

- Butterfield, K. D., Trevin, L. K., & Weaver, G. R. (2000). Moral awareness in business organizations: Influences of issue-related and social context factors. Human Relations, 53(7), 981–1018. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726700537004

- Cassematis, P. G., & Wortley, R. (2013). Prediction of whistleblowing or non-reporting observation: The role of personal and situational factors. Journal of Business Ethics, 117(3), 615–634. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1548-3

- Chankseliani, M., Qoraboyev, I., & Gimranova, D. (2021). Higher education contributing to local, national, and global development: New empirical and conceptual insights. Higher Education, 81(1), 109–127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00565-8

- Cheliatsidou, A., Sariannidis, N., Garefalakis, A., Passas, I., & Spinthiropoulos, K. (2023). Exploring attitudes towards whistleblowing in relation to sustainable municipalities. Administrative Sciences, 13(9), 199. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13090199

- Craft, J. L., Journal, S., & October, N. (2013). A review of the empirical ethical decision-making literature : 2004 – 2011 linked references are available on JSTOR for this article : A Review of the empirical ethical decision-making literature. Journal of Business Ethics, 117(2), 221–259. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1518-9

- Culiberg, B., & Mihelič, K. K. (2017). The evolution of whistleblowing studies: A critical review and research agenda. Journal of Business Ethics, 146(4), 787–803. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3237-0

- Curtis, M. B., & Taylor, E. Z. (2009). Whistleblowing in public accounting: Influence of identity disclosure, situational context, and personal characteristics. Accounting and the Public Interest, 9(1), 191–220. https://doi.org/10.2308/api.2009.9.1.191

- De Matos, C. A., Ituassu, C. T., & Rossi, C. A. V. (2007). Consumer attitudes toward counterfeits: A review and extension. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 24(1), 36–47. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363760710720975

- Dijkstra, T. K., & Henseler, J. (2015). Consistent partial least squares path modeling. MIS Quarterly, 39(2), 297–316. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2015/39.2.02

- Dzikrullah, A. D., Harymawan, I., & Ratri, M. C. (2020). Internal audit functions and audit outcomes: Evidence from Indonesia. Cogent Business & Management, 7(1), 1750331. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1750331

- Ebbes, P., Papies, D., & Heerde, H. J. V. (2016, January). Dealing with Endogeneity: A Nontechnical Guide for Marketing Researchers. In C. Homburg et al. (eds), Handbook of market research (pp. 1–37). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-05542-8_8-1

- Erkmen, T., Çalışkan, A. Ö., & Esen, E. (2014). An empirical research about whistleblowing behavior in accounting context. Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change, 10(2), 229–243. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAOC-03-2012-0028

- Ethics Compliance Initiative. (2019). Workplace misconduct and reporting: A global look. https://www.ethics.org/wp-content/uploads/Global-Business-Ethics-Survey-2019-Third-Report.pdf

- Ethics Resource Centre. (2014). Global ethics survey. https://www.ethics.org/.

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Addison-Wesley Publishing Company.

- Ford, R. C., & Richardson, W. D. (1994). Ethical decision making: A review of the empirical literature. Journal of Business Ethics, 13(3), 205–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2012.05.050

- Gao, L., & Brink, A. G. (2017). Whistleblowing studies in accounting research: A review of experimental studies on the determinants of whistleblowing. Journal of Accounting Literature, 38(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acclit.2017.05.001

- Haines, R., Street, M. D., & Haines, D. (2008). The influence of perceived importance of an ethical issue on moral judgment, moral obligation, and moral intent. Journal of Business Ethics, 81(2), 387–399. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-007-9502-5

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., Black, W. C., & Anderson, R. E. (2018). Multivariate data analysis (8th ed.). Cengange Learning EMEA. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119409137.ch4

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2022). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling. Long Range Planning, 46, 1–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2013.01.002

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 139–152. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

- Indonesian Coruption Watch. (2021). Trend Penindakan Korupsi Sektor Pendidikan: Pendidikan di Tengah Kepungan Korupsi. https://antikorupsi.org/id/article/tren-penindakan-korupsi-sektor-pendidikan-pendidikan-di-tengah-kepungan-korupsi

- Jones, T. M. (1991). Ethical decision making by individuals in organizations : An issue-contingent model. The Academy of Management Review, 16(2), 366–395. https://doi.org/10.2307/258867

- Kang, M. M. (2023). Whistleblowing in the public sector: A systematic literature review. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 43(2), 381–406. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734371X221078784

- Kaplan, S., & Whitecotton, S. M. (2001). An examination of auditors’ reporting intentions when another auditor is offered client employment. AUDITING: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 20(1), 45–63. https://doi.org/10.2308/aud.2001.20.1.45

- Kaplan, S., Pany, K., Samuels, J., & Zhang, J. (2009). An examination of the association between gender and reporting intentions for fraudulent financial reporting. Journal of Business Ethics, 87(1), 15–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-9866-1

- Kaptein, M. (2011). From inaction to external whistleblowing: The influence of the ethical culture of organizations on employee responses to observed wrongdoing. Journal of Business Ethics, 98(3), 513–530. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0591-1

- Keenan, J. P. (1990). Upper-level managers and whistleblowing: determinants of perceptions of company encouragement and information about where to blow the whistle. Journal of Business and Psychology, 5(2), 223–235. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01014334

- Keller, A. C., Smith, K. T., & Smith, L. M. (2007). Do gender, educational level, religiosity, and work experience affect the ethical decision-making of U.S. accountants? Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 18(3), 299–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2006.01.006

- Kim, J., & Loewenstein, J. (2020). Analogical encoding fosters ethical decision making because improved knowledge of ethical principles increases moral awareness. Journal of Business Ethics, 172(2), 307–324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04457-w

- Kock, N. (2015). Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. International Journal of e-Collaboration, 11(4), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijec.2015100101

- Kock, N. (2022). Testing and controlling for endogeneity in PLS-SEM with stochastic instrumental variables. Data Analysis Perspectives Journal, 3(1), 1–6.

- Latan, H., Chiappetta Jabbour, C. J., & Lopes de Sousa Jabbour, A. B. (2019). Ethical awareness, ethical judgment and whistleblowing: A moderated mediation analysis. Journal of Business Ethics, 155(1), 289–304. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3534-2

- Latan, H., Chiappetta Jabbour, C. J., Ali, M., Lopes de Sousa Jabbour, A. B., & Vo-Thanh, T. (2023). What makes you a whistleblower? A multi-country field study on the determinants of the intention to report wrongdoing. Journal of Business Ethics: JBE, 183(3), 885–905. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-022-05089-y

- Latan, H., Ringle, C. M., & Jabbour, C. J. C. (2018). Whistleblowing intentions among public accountants in indonesia: Testing for the moderation effects. Journal of Business Ethics, 152(2), 573–588. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3318-0

- Lee, G., & Xiao, X. (2018). Whistleblowing on accounting-related misconduct: A synthesis of the literature. Journal of Accounting Literature, 41(1), 22–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acclit.2018.03.003

- Lee, H. (2020). The implications of organizational structure, political control, and internal system responsiveness on whistleblowing behavior. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 40(1), 155–177. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734371X18792054

- Lee, J., Ramamoorti, S., & Zelazny, L. (2021). Whistleblowing Intentions for Internal Auditors. CPA Journal, 16(1), 46–51. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=sso&db=buh&AN=152588730&custid=s4338230