?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Recent studies have addressed the impact of Environment, Social, and Governance responsibility on corporate financial performance and value, but often ignore its impact on non-financial performance. Whereas the ultimate goal of ESG responsibilities is non-financial matters, that is, to incorporate socially acceptable norms into business activities to reach sustainable goals for society. Employing an unbalance panel data model for listed companies in Indonesian Stock Exchange from 2016 to 2022, this study provides empirical evidence on the indirect impact of ESG implementation on firms’ non-financial performance. Consistent with the stakeholder theory, this study found a positive impact of ESG implementation on firm values. The predictability of ESG performance in future financial performance is in line with the resource-based views. ESG-related financial performance has a positive impact on non-financial performance. Firms are willing to increase their commitment to ESG activities if these activities can primarily improve their financial performance. The regulatory policy with dual materiality characteristic is effective in mitigating the mere financial motives of ESG implementation to the more substantive outcomes on ESG-related issues. The effective law enforcement is able to encourage the companies not only to symbolically implement the ESG but to go beyond the legitimate substantive strategic implementation.

1. Introduction

The United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) has transferred the global focus of business actors’ in accomplishing global goals. The SDGs are rapidly developing a common language across the business sectors. Investors, employees, consumers, and other stakeholders have pushed business actors to become more sustainable (de Silva Lokuwaduge et al., Citation2020; Kumar & Firoz, Citation2019; Luo et al., Citation2012; Manita et al., Citation2018). Indonesia as part of the world society has committed itself on the SDGs. At the national level, the execution of this commitment has been transformed into a number of policies.

One of the most important policies introduced by the Financial Services Authority No. 51/POJK.03/2017 (POJK 51, Citation2017). The program is aimed at strengthening the country’s financial services sector, improving stability, transparency and consumer protection. The policy is created specifically for financial institutions to act in a responsible and sustainable manner. With the issuance of POJK 51, the government requires all financial institutions to implement sustainable financial principles by submitting sustainable financial action plans and sustainability reports to the Financial Services Authority and the public. The banking sector must avoid lending to companies that pose environmental, social and governance risks. Consequently, the guidelines and requirements in POJK 51 must also be implemented by non-financial companies. Companies are encouraged to adopt responsible and sustainable practices, including ESG considerations. Based on POJK 51 and the supplementary provision of OJK letter No. S-264/D.04/2020 dated November 4, 2020, publicly listed companies are required to prepare a sustainability report. The ESG report is no longer a supporting financial report. In this way, stakeholders can gain access to the company’s sustainable information. Investors can also use the information to estimate a company’s financial risk, leading to more stable and higher long-term returns.

Another policy is the Program for Pollution Control, Evaluation, and Rating (PROPER), introduced by the Ministry of Environment and Forestry. This program is an environmental rating system developed in Indonesia. It aims to improve the environmental performance of industries and business by evaluating and rating their compliance with environmental regulations. Under PROPER, companies are categorized into different colours based on their environmental performance. Blue, green, yellow, and red indicate excellent, good, moderate, and poor performance, respectively. PROPER serves as a tool to encourage companies to improve their environmental practices and reduce their environmental impact. It provides incentives for companies to invest in pollution control technologies and adopt sustainable practices. In 2019, corporate performance on environmental management reporting can be done online via Electronic Reporting System (SIMPEL). The results are distributed through the website of the Ministry of Environment and Forestry and various media publications. Because of the extensive involvement of stakeholders, the PROPER program is also known as public disclosure of environmental performance.

In particular, current regulatory approaches of sustainability reporting fall along a range between two boundaries, which are categorized as narrow and broad approach. The narrow approach emphasizes on providing investors what they want, and focuses on the information demands of investors. In the case of ESG information, what matters to the investors are whether such information affect companies’ financial risk and return for their purpose of investment decision making process. Thus, POJK 51 falls under a narrow regulatory approach, because the purpose of the regulation is on the ESG implementation process by ensuring the companies’ compliance in providing sustainability reports. The other approach is that the regulation is intended for specific business actors with the purpose to drive change and encourage desirable behaviors in society. The ultimate goal is on the outcomes of the ESG implementation process. The broad approach includes dual materiality, firstly, how ESG issues impact the firm’s performance, secondly how the implementation of ESG impact the externalities, environment, and society. PROPER can be categorized as a broad approach because the ultimate goal of the regulation is the companies’ outcomes of the environmental-related issues. The two approaches, however, can blend together once the investors have preferences beyond companies’ value maximization (Christensen et al., Citation2021). Chen and Tian (Citation2015), Haque and Ntim (Citation2018, Citation2020), and Jin et al. (Citation2011) suggest that firms’ commitment on good corporate social responsibility (CSR) practices result in increased stakeholders’ trust and satisfaction, and therefore improved financial and non-financial performance. We predict that the improvement on financial performance precedes the achievement of non-financial performance. Thus, the latter achievement requires the law enforcement from the regulators to impose great pressure on the companies to incorporate socially acceptable norms, practices and values into their firms’ operations and activities.

Stakeholder theory (Freeman, Citation1984) posits the idea that successful companies are able to align the interests of all stakeholders to make them more sustainable. They focus not only on maximizing financial performance in the interest of shareholders, but also in the interest of other stakeholders (Armstrong, Citation2020; Kumar et al., Citation2020). A growing number of academic studies have examined the association of ESG scores with variable of interest, including stock market performance, financial performance, financial constraints and governance characteristics (Cheng et al., Citation2014; Hubbard et al., Citation2017; Khan et al., Citation2016). Many studies on ESG are based on market criteria to measure the firm performance (Capelle-Blancard & Petit, Citation2016; Galbreath, Citation2013; Griffin & Sun, Citation2013; Hsu & Wang, Citation2013; Mitsuyama & Shimizutani, Citation2015). The studies that use accounting based criteria to measure financial performance provide mixed evidence. Some empirical studies reported a positive association between ESG and firm financial performance (Auer & Schuhmacher, Citation2016; Crifo et al., Citation2019; Fatemi et al., Citation2017). Some other studies reported negative relation between the two variables (Hahn et al., Citation2010; Winn et al., Citation2012). The rest of the studies do not provide strong support on the relation between the two variables (Kitzmueller & Shimshack, Citation2012; Margolis et al., Citation2009). Despite many papers that have been written on this topic, it is difficult to draw a causal conclusions regarding the firm motives of implementing ESG because of a lack of a clear identification strategy.

Al-Issa et al. (Citation2022) studied the impact of ESG and CSR engagement on marketing expense and firm value to provide a strategic rationale for firms to undertake the sustainability activities to position their companies distinctly in the market. They found that ESG engagement had a direct effect, while CSR had an indirect effect on firm value, measured by Tobin’s Q. The indirect effect of CSR engagement on firm value is mediated by the ratio of marketing expense to revenue. Ahmad et al. (Citation2021) revisited the impact of ESG on financial performance of FTSE 350 UK firms and incorporated static and dynamic panel data analysis. The result indicates that ESG has positive and significant impact on firm financial performance. While most research has studied and validated the beneficial effect of ESG on financial performance, Hamdi et al. (Citation2022) explored the nexus between financial performance and ESG relationship in a double causality relationship. They found a positive impact of financial performance on ESG with the sample of 10,000 firm-year observations of 504 US firms.

In this study, we offer another way to examine the potentially value enhancing effects of ESG by examining its association with accounting performance. In this way, we essentially test the notion whether the company is “doing well by doing good.” Previous literature documents the impact of social responsibility on firm performance, and concludes that gaining financial benefit is the main purpose of “doing good” (Elfenbein et al., Citation2012; List, Citation2006). If this is the case, then the ultimate purpose of ESG implementation will not reach the sustainable goals for externalities, environment, and society. Inspired by Alatawi et al. (Citation2023) in their systematic literature review on the impact of CSR on financial and non-financial performance in the tourism sector, we incorporate non-financial measures as the ultimate goal of ESG implementation, imposed by the law enforcement. We combined the conceptual frameworks which are the indirect relation of CSR on firm value presented in Al-Issa et al. (Citation2022) and the nexus between financial performance and ESG relationship in a double causality relationship conducted in Hamdi et al. (Citation2022), to draw a new similar framework. This framework is used to revisit the impact of ESG on financial performance by articulating the motives behind the implementation of ESG. The motives could be just to perceive a routine procedure, or to gain a competitive advantage, or in some point on the way to reach external sustainability. In any case, the adoption of ESG is a dynamic and time-varying process (Iannou & Serafein, Citation2019).

As Indonesian companies are now voluntarily participating in many ESG practices, indicating that they get financial reward for their ESG activities. Without such financial reward, companies may hesitate to engage in ESG activities. In this situation, it is necessary for law enforcement to encourage them to carry out the ESG activities to reach the goal beyond the financial matters. Thus, the purpose of this study is to analyze the nuanced process of ESG adoption and implementation in Indonesia by examining the financial and non-financial impacts in the context of two government policies, namely POJK 51 and PROPER. The motive behind ESG adoption can be revealed by re-examining the impact of ESG scores on firm market value and financial performance and by further analyzing its implication on firm non-financial performance, measured by ESG disclosures. Government intervention through POJK 51 and PROPER is employed as regulatory policies that will direct the companies to make a change and to incorporate socially acceptable norms, practices and values into their operations and activities.

Thus, referring to the Indonesian context, this study attempts the following contributions to the existing literature. First, this study provides more empirical evidence on the impact of ESG implementation not only on the firms’ market value and financial performance, but also on the firms’ non-financial performance. Existing studies have often neglected the non-financial measures. Second, this study finds that the predictability of ESG on financial performance can be used to promote firms’ non-financial performance, measured by ESG disclosure. This finding implies that the effect of ESG implementation on non-financial performance is indirect. Firms are willing to disclose and increase their commitment to ESG activities if these activities can primarily improve their financial performance. Third, as the ultimate goal of ESG implementation is to improve firms’ non-financial performance by increasing commitment to social norms and accepted behaviour, this study provides a specific evidence on the effectiveness of Indonesian Government policies to induce such expected behaviour in society. Fourth, the industry-specific analysis of before-after law enforcement by regulators enriches empirical findings that are useful for evaluating the existing policies.

This study draws a sample of companies listed on the Indonesian Stock Exchange in the years 2016–2022. The main results and findings of this study are comprised into four parts. First, this study finds that ESG implementation have a positive and significant effect on corporate market value. Second, this study also documents that ESG performance implementation can be used to predict future financial performance. Third, the ESG-related financial performance has a positive and significant influence on firms’ non-financial performance. Companies are willing to become more involved in ESG activities if these activities significantly improve their financial performance. Fourth, POJK 51, a narrow approach of law enforcement, is effective to motivate the companies to “do good when they do well”. PROPER, a broad approach of law enforcement, is effective in influencing the actions of companies whose motives for engaging in ESG activities are no longer about financial matters.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: section 2 explains the background to conduct this study by incorporating regulatory and policy issues and developments within the research context and setting. Section 3 covers the theoretical framework to support the underlying prediction. Section 4 presents literature review and hypotheses development. Section 5 describes the data, the statistical models, and the research design and methods. Section 6 shows the empirical results and discusses the findings. Section 7 concludes and provides some limitations.

2. Background

As the purpose of this study is to analyse the nuanced process of ESG adoption and implementation, we need to conduct the study in a country that is still in the process of developing the ESG aspects to become an important consideration in determining the purpose of business activities. Indonesia is one of the ASEAN countries that has implemented the ESG concept, but public understanding regarding ESG is still preliminary. Based on the Indonesia Business Council for Sustainable Development (IBCSD) survey in 2021, Indonesia’s ESG index is ranked 36 out of 47 in the world capital market. Apart from that, 40% of companies in Indonesia are still not aware of the important role of ESG. Nevertheless, companies in Indonesia are preparing to open access to large pools of capital with efforts to achieve sustainable companies.

In the national level, the implementation of ESG commitment has been translated into a number of policies. One of them is issued by Financial Services Authority Regulation No. 51/POJK.03/2017 on the Application of Sustainable Financing, which requires financial institutions, issuers, and publicly listed companies to apply sustainable financing and prepare sustainability report. ESG report is no longer a supporting to financial report. Based on Article 7, paragraph (1) of the Financial Services Authority Regulation, there are 3 priorities for the implementation of sustainable financing. Banks are required to implement these 3 priorities, which are the development of products for financial services, increasing the capacity of financial institutions, and adapting financing service institutions to be in accordance with the principles of sustainable financing implementation (Naiborhu, Citation2023). As a consequence, banking industry has to avoid extending credits to the companies that pose risks to the environment, social, and governance. The non-financial companies have to implement the guidelines and requirements set out in POJK 51, as well. For the companies that look-forward to the successful sustainability, the traditional financial report and sustainability report have to go together. A comprehensive ESG report must contain credible information on ESG progresses from corporations. The information will be useful for investors in estimating company financial risk that leads to more stable and higher long-term returns.

Nonetheless, the majority of companies has little understanding where to begin this practice that makes the sustainability reports lack reliable information. Foundation for International Human Rights Reporting Standards (FIHRRST) is a foundation established by a group of influential human rights activists at the national and international levels. The FIHRRST activities involve in the preparation and study of sustainability reports of business and human rights. In November 2020, FIHRRST issued the results of a Sustainability Report Study in 2019 of all publicly listed companies in Indonesia, to foster reporting on ESG aspects as mandated by the POJK 51 and the Global Reporting Initiatives (GRI) Standards which contain reporting on economic, taxation, environmental and social aspects. In term of bringing the issue of ESG in business activities, FIHRRST greatly involves in assisting the government and companies in Indonesia.

Another policy is PROPER, which was introduced by the Ministry of the Environment in response to weaknesses in the environmental inspection program. PROPER is intended to support sustainable economic development and a sustainable environment. The PROPER program has been operating for two decades since its first implementation in June 1995. However, the progress and achievements of the PROPER program have not been properly analysed. In an empirical study, Handoyo (Citation2018) documented that the achievement of environmental performance in Indonesia from the period 2011–2015 is only at a sufficient level. He suggests that Indonesia requires improvement to higher level of environmental performance; active role of policymakers, mandatory PROPER program instead of voluntary.

Considering the situation and conditions of the Corona Virus Disease 2019 (Covid-19) pandemic that occurred in Indonesia and several other countries, PROPER implementation begins with the selection of targeted companies in 2019. The companies targeted as PROPER participants are companies that have an important impact on the environment, are listed on the stock exchange market, have export-oriented products, and are utilized by the wider community. A company’s participation in PROPER now is mandatory, if it has been appointed, it must be managed carefully, professionally, and continuously by continuing to develop the key mandatory indicators of environmental performance.

The program is designed to use disclosure, environmental and reputational awards as motivational forces for environmental improvement (Afsah et al., Citation2013). The basic idea of PROPER is to use public disclosure of environmental indicators by companies as a substitute for enforcement (García et al., Citation2007). As part of the PROPER program, business entities are evaluated by the Environmental Impact Agency of the Ministry of the Environment and Forestry based on clearly defined criteria. The results of this assessment are reflected in an index that has been widely published (Makarim and Butler, Citation1996). In order to get a complete picture of the behavior patterns of the system, it is necessary to install sensors to monitor the behavior of the pollution sources. This monitoring system is a subsystem of SIMPEL (Environmental Electronic Reporting System Live), which is an online reporting system that replaces manual or paper reporting systems. With SIMPLE, the Ministry of Environment and Forestry makes reporting easier for companies. Companies simply enter data from laboratory analysis and waste management results online by filling in the necessary support files. The data entered annually is stored in a database so that it can be easily used to analyse trends in the company’s environmental management. Currently, 6,753 companies have registered with SIMPEL and 3,945 companies are actively implementing the management reporting environment. As of 2019, these data are available online at the Ministry of the Environment and Forestry. PROPER registered companies can directly access their performance appraisal results without having to manually print them on paper. The environmental behavior of companies is mapped on a scale of five colors; gold for excellent, green for good, blue for moderate, red for poor, and black for very poor. Based on the PROPER color index, the Ministry of Environment and Forestry classifies gold, green and blue as environmentally friendly. Meanwhile, the red and black color index does not track the environment. The results are distributed through the website of the Ministry of Environment and Forestry and various media publications. Because of the extensive involvement of stakeholders, the PROPER program is also known as public disclosure of environmental performance.

There are several incentives for companies to engage in PROPER and improve their environmental performance as part of their ESG implementation. The incentives include improving their environmental performance, benefit from enhance reputation, increased investors’ interest, regulatory compliance, cost savings, and access to government incentives. The government incentives are tax breaks, grants, and subsidies to companies that actively participate in PROPER environmental program. These incentives can further motivates companies to invest in sustainable practices and improve their environmental performance.

This study provide an evaluation on the effectiveness of the two policies by providing empirical evidence on before-after effects of the POJK 51 and PROPER policies. Based on POJK 51 and the additional provision of OJK letter No. S-264/D.04/2020 of November 4, 2020, financial institutions, issuers, and publicly listed companies are required to prepare a Sustainability Report. Related to this study, year 2020 can be used as a cut-off point to measure the difference of the ESG-related financial performance impact on non-financial performance. Related to PROPER, year 2019 can be used as a cut-off point to statistically test - the before after - impact of environment-related financial performance on the improvement of non-financial performance. We predict a dynamic impact between the two policies, due to the spectrum differences. POJK 51 has a narrow spectrum because the focus is to measure the effectiveness of ESG implementation process through sustainability reporting. On the other hand, PROPER is considered to have a broader spectrum because the environmental disclosure measures directly the companies’ environmental performance which is the outcomes of their environmental responsibility process. POJK is intended more to the financial industry, PROPER target is on polluted companies, categorized in sensitive industries.

3. Theoretical literature review

The literature on the impact of ESG implementation on firm value and financial performance often draws on the three theoretical perspectives: stakeholder theory, resource-based theory, and legitimacy theory. In light with drawing causal relationship of corporate ESG implementation and non-financial performance, we need to go beyond these theories, and analyse further to the motivation of companies in corporate goodness spending. The literature on the notion of “doing well by doing good” explores the association of companies’ financial and non-financial performance. In this section, we will discuss each of these theories and apply them to develop our hypotheses and interpret the empirical findings.

3.1. Stakeholder theory

Stakeholder theory is a concept that firms should consider not only shareholder’s interest, but also the interest and need of various groups, including employees, customers, suppliers, communities, and the environment. When it comes to corporate ESG implementation, stakeholder theory plays a crucial role, that enables the companies to identify and engage with the various stakeholders affected by the ESG practices. Post et al. (Citation2002) defines a company’s stakeholders as "individuals and constituents who voluntarily or involuntarily contribute to their ability and activities to create wealth and who are potential beneficiaries and/or bearers of risk." Stakeholder theory can even emphasize on an institutional view. Since the social entity in which companies operate consists of stakeholders, legitimacy rests on meeting their expectations. A company develops legitimacy by meeting stakeholder expectations (Bansal & Bogner, Citation2002).

Stakeholder theory states that companies disclose their financial and non-financial information to satisfy the needs of various stakeholders (Ahmad et al., Citation2021; Albitar et al., Citation2020; Atan et al., Citation2018). The performance of companies in ESG activities is becoming an increasingly important aspect for stakeholders and in the investment decision-making process (Ahmad et al., Citation2023; Almeyda & Darmansya, Citation2019). ESG issues are the most important factor for prospective investors, as companies with good ESG scores are considered better equipped to anticipate future risks and opportunities. Some studies (Aydoğmuş et al., Citation2022; Naseer et al., Citation2023) have documented that companies that follow ESG principles have lower operational risk and can be more sustainable, even under less favorable financial conditions.

ESG usually strives for improving social welfare or making business activities more sustainable. ESG can be fully aligned with shareholder interests and even increase company value by building trust and social capital (Lins et al., Citation2017). However, maximizing firm value is not necessarily the same as maximizing shareholder welfare (Hart & Zingales, Citation2017). Shareholders may have non-financial preferences and therefore be concerned about a company’s negative impact on the environment or society, even if this impact does not have direct monetary consequences. ESG commonly aims that a company engages in a broader goal than maximizing market value and pursues to meet the essentials and expectations of a broader group of stakeholders than the company itself. In doing so, companies may sacrifice profitability (Bénabou & Tirole, Citation2010; Holthausen & Leftwich, Citation1983; Wong et al., Citation2021), although losing profitability is not necessarily part of the definition of ESG (Kitzmueller & Shimshack, Citation2012).

Stakeholder theory also encourages companies to adopt a long-term goal when implementing ESG. Instead of focusing only on short-term financial goals, companies recognize that sustainable and responsible practices can lead to better outcomes for all stakeholders in the long term. Generally based on stakeholder theory, corporate ESG practices can increase the value of companies, but the reasons behind increasing the value of companies can be different. In one hand the reason is due to the possibility of gaining more resources to increase profitability, on the other hand is caused by the firms’ legitimately meeting the stakeholders expectation. Meanwhile, as previously recognized, stakeholder expectations are not necessarily aligned with shareholder maximization. So the following two theories, resource-based and legitimacy theory, can be used to deepen our understanding of the reasons and motives behind the implementation of ESG. If the implementation of corporate sustainability (ESG scores) can increase the firm value, it means that ESG scores can be used to predict future financial performance. If the predictability of ESG scores in future financial performance affects the non-financial performance, this situation indicates that the motivation of companies to implement ESG is determined by financial reasons.

3.2. Resource-based theory

Stakeholder theory can also be complemented by resource-based theory, as companies may see meeting stakeholder needs as a strategic investment that requires commitments beyond the minimum requirements to satisfy stakeholders (Ruf et al., Citation2001; Serafeim, Citation2020). Resource-based theory suggests that firms can create sustainable competitive advantages by effectively controlling and manipulating their resources, which are valuable, unique, imperfectly imitable, and for which no perfect substitutes are available (Barney, Citation1999; Kraaijenbrink et al., Citation2010; Pertusa-Ortega et al., Citation2010; Utami & Alamanos, Citation2023). These resources include physical assets, financial resources, human capital, and organizational processes that can develop unique capabilities and competencies that are instrumental in competitive advantage and increased firms’ value (Backman et al., Citation2017). Partaking in ESG activities when it is expected to promote the company is a conduct that can be evaluated through the lens of resource-based theory (Bhandari et al., Citation2022; Surroca et al., Citation2010). Companies attract in ESG because it is realized that they get a specific competitive advantage.

According to the resource-based theory, ESG provides internal or esxternal paybacks (Branco & Rodrigues, Citation2006; Orlitzky et al., Citation2003). The following are the internal paybacks. Investments in responsible ESG activities have intrinsic paybacks for a company in the form of new resources, know-hows, and corporate culture. These investments have important significances in inventing or depleting essential intangible resources. Liang et al. (Citation2022) document that the implementation of a company’s ESG strategy is an important determinant affecting sustainable management performance. The findings offer important and practical implications not only for achieving sustainable growth but also for creating a competitive advantage. Previous study reveals that corporate sustainability has a positive effect on employee motivation, morale, commitment and loyalty to the company (Brammer et al., Citation2007). In addition to the company’s productivity benefits, it also reduces the cost of recruiting and training new employees (Vitaliano, Citation2010). Further empirical evidence in the area of environmental responsibility, adopting process-based initiatives for climate change can improve economic efficiency, reduce operational and process costs, reduce business risks, strengthen stakeholder relationships and create sustainable benefits (Hart & Dowell, Citation2011). Process-based climate change initiatives can also develop resource mixes for green innovation, prevent greenhouse gas emissions and waste, and improve internal resilience to climate change (Weber & Neuhoff, Citation2010).

The external paybacks of ESG are related to their influence on corporate reputation (Branco & Rodrigues, Citation2006; Gallego-Alvarez et al., Citation2010; Hussainey & Salama, Citation2010; Orlitzky, Citation2008; Orlitzky et al., Citation2003). Corporate reputation is valued as one of the most critical intangible resources that furnish a effective sustainable competitive advantage (De Leaniz & Del Bosque, Citation2013; Roberts & Dowling, Citation2002). Companies with good ESG can develop relationships with customers, investors, bankers, suppliers and competitors. They can also attract better employees improve their motivation and morale, as well as increase their commitment and loyalty to the company, which result in the financial benefits. Stakeholders ultimately have a hold over a firm’s access to scarce resources, and firms must get on the relationships with key stakeholders to guarantee maintained resources access (Roberts, Citation1992). ESG responsibility can generally increase long-term benefits through improved stakeholder relations and reduced costs of conflict with them, building reputation and employee productivity. All these make companies more appealing to investors. A higher level of ESG responsibility can reduce economic uncertainty, increase profit predictibility, and lower risk for investors.

3.3. Legitimacy theory

Legitimacy theory, also known as institutional perspectives, is used as a lens to examine corporate sustainability (Campbell, Citation2007; Doh et al., Citation2010; Doh & Guay, Citation2006). The theory predicts that firms will adopt specific behaviors to gain supports of critical stakeholders and access the external resources (Doh et al., Citation2010). The focus of the theory is on social legitimacy, which refers to the acceptance of the company by the society. Failure to meet essentially institutionalized standards and social norms can threaten companies’ legitimacy, resources, and survival. This theory suggests that firms respond strategically to institutional norms and changes in society to maintain and even gain legitimacy because social conformity leads to improved access to external resources (Bansal, Citation2005; Suchman, Citation1995).

There are two types of legitimacy strategies, which are symbolic or greenwashing strategies and substantive strategies. Firms seeking legitimacy motivated by symbolic strategies, implement ESG-related issues through superficial impressions, rather than producing meaningful improvements to get ESG outcomes (Aguilera et al., Citation2007; Ashforth & Gibbs, Citation1990). In this case, companies with higher ESG performance are subject to more pressures from stakeholders. Therefore they may make symbolic/greenwashing efforts to maintain legitimacy (Suchman, Citation1995), even though such efforts do not improve ESG performance (Crossley et al., Citation2021). In contrast, substantive strategies involve fundamental changes in a company’s goals, behaviours, and practices to meet the expectations and needs of societal stakeholders (Ashforth & Gibbs, Citation1990). In this context, companies can take ESG actions to address ESG-related issues by adopting sustainable activities that can lead to get outcomes and value. The adoption of comprehensive ESG actions, in fact, requires significant investment and resources. Therefore, companies are more likely to engage in symbolic rather than substantive ESG strategies to create a positive impression among stakeholders and to protect company value (Berrone & Gomez-Mejia, Citation2009; Maas & Rosendaal, Citation2016).

The notion of "doing well by doing good" can be used to explore the motivation of companies to engage in ESG practices based on legitimacy theory. When firms "do good," they increase their legitimacy, which promotes financial performance and firm value. Additionally, the improvement in financial performance obtained from ESG practice will encourage companies to do more in the activities of corporate sustainability, to make external changes and to participate in acceptable social standards and practices in their operations and activities.

3.4. The notion of “doing well by doing good”

The notion that companies can do well by doing good has attracted the attention of executives, business academics and public officials. The annual report of almost every big company claims that their mission is to serve some greater social purpose than making a profit. It is believed that companies can achieve some positive social goals without suffering financially. According to the proposition of "doing well by doing good", companies have a corporate social responsibility to achieve some major social goal, and this can be done without financial sacrifice. A major driver of corporate interest in ESG-related activities is the argument that corporate virtue provides financial rewards (Vogel, Citation2005). With a strategic approach, ESG-related practices do not have to be a cost and can be a source of competitive advantage. This appealing proposition has convinced so many people.

Related research documents that companies practicing corporate responsibility perform well in the long term (McWilliams & Siegel, Citation2001; Orlitzky et al., Citation2003). However, other research has shown that firms undertaken corporate responsibility over-spent on strategic corporate responsibility (Lantos, Citation2001). It seems that there is an optimal level of spending on strategic corporate responsibility (Orlitzky & Moon, Citation2010). Therefore, it is necessary to constantly balance the conflicting interests of stakeholders and measure the return on strategic investments in social responsibility (Freeman, Citation1984; McWilliams & Siegel, Citation2001). (Porter & Kramer, Citation2006) suggest that firms can develop an affirmative CSR agenda that maximizes societal benefits and gains for the businesses themselves, rather than acting solely on well-intentioned incentives or responding to external pressures.

Karnani (Citation2010) states that where many major social problems reside, there is a conflict between corporate profits and social welfare. Doing well by doing good is almost impossible. Managers face increasing pressure from increasingly active shareholders to act in the interests of shareholders. In this situation, managers may act less for the social interest if it imposes a significant financial sacrifice on the companies. In this situation, the role of the government is necessary to force firms to change their behavior to be in line with the interests of society. Unfortunately, ESG-related issues may not lend themselves to such easy solutions. In this case, "doing well" and "doing good" are contradictory. Strong behavior needs to be curbed. The last option to intervene in the company’s behavior to achieve the interest of society is government regulation.

4. Empirical review and hypotheses development

4.1. The impact of ESG implementation on companies’ market value

Many studies have documented the effect of ESG on firm value and profit. According to Friede et al. (Citation2015), researchers started looking for an association between ESG ranks and the financial performance of companies in the 1970s. After reassessing 2,200 papers, they inferred that research verifies the logic of ESG investing and that almost 90% of studies show a positive relationship between ESG and a company’s market value and financial performance. Another meta-analysis of 132 papers published in reputable journals revealed that 78% pointed out a positive relationship between sustainability and company financial performance (Alshehhi et al., Citation2018).

Most studies have found a positive relationship between ESG and financial performance of companies, confirming that the positive effect of ESG scores on financial performance is stable over time and space (Liu et al., Citation2022; Malik et al., Citation2015). In fact, ESG scores appear to have a positive and significant effect on financial performance and firm value in different samples across different countries (Elmghaamez et al., Citation2023). According to stakeholder theory (Freeman, Citation1984), most studies have found evidence that companies with better ESG performance have better financial performance and are more valued in the market compared to their peers (Aboud & Diab, Citation2018; Ahmad et al., Citation2021; Chouaibi et al., Citation2021; Deng et al., Citation2023; Melinda & Wardhani, Citation2020; Sinha Ray & Goel, Citation2023; Xie et al., Citation2019).

Even though, previous studies in Indonesia show mixed results (Gunarsih et al., Citation2020), we focus on stakeholder theory in developing the hypothesis of the impact of ESG implementation on companies’ market value. This is due to the growing awareness of investment sustainability among Indonesian stakeholders. There is already an indicator that shows the correlation of high returns of ESG investments, as measured by the Sustainable and Responsible Investment (SRI) - KEHATI Stock Index. It is the only one of its kind on the Indonesia Stock Exchange (IDX) as it focuses on companies that meet ESG criteria (Prasidya, Citation2020).

Considering the theoretical and empirical literature mentioned above, as well as taking into account the increased interest of investors and the public image of the company, we state the following hypothesis:

H1: Corporate sustainability performance reflected in ESG scores has a positive impact on firm value.

4.2. The predictability of ESG on companies’ financial performance

In a latest meta-analysis, Whelan et al. (Citation2021) from Rockefeller Asset Management and the NYU Stern Center for Sustainable Business assessed more than 1,000 articles published between 2015 and 2020 that aimed on the association between ESG and financial performance. The analysis discovered that 58% of the papers found a positive association between ESG and financial performance, 8% a negative association, 13% no association and 21% mixed results. They concluded that although the majority was positive, the results reflect continued disagreement on the issue. In this study, we re-examine the relationship of ESG scores and financial performance, and hypothesize ESG scores as a predictor of future financial performance.

Based on resource-based theory, ESG implementation becomes a source of corporate competitiveness (Cao et al., Citation2019; Waddock & Graves, Citation1997), which is useful to disclose for predicting future financial performance. Therefore, companies must supplement financial information with other information of interest to shareholders, such as customer data, human capital, innovation, and other intangible assets. Proponents of this "financial materiality" view argue that financial information is not a perfect predictor of future financial performance (Jørgensen et al., Citation2022). As a result, sustainability information can provide insight into a company’s expected future financial performance. Reporting in the form of sustainability metrics can provide information about a company’s intangible assets that are not captured on the balance sheet (Eccles, Citation1991).

Additionally, the proponent of “doing well by doing good” predicts that the companies that concern about the ESG-related issues and incorporate into their business activities, would result in the improvement of future financial performance. Liang and Renneboog (Citation2017) define CSR as “firm activities that improve social welfare but not necessarily at the expense of profits.” A positive relation between corporate sustainability activities and firm performance is often referred to “doing well by doing good” (Deng et al., Citation2013; Dowell et al., Citation2000; Flammer, Citation2015; Orlitzky et al., Citation2003).

Based on the first hypothesis that high ESG performance creates value as predicted by stakeholder theory, we construct a conditional hypothesis that links ESG performance to future financial performance. Combining a resource-based theory and the notion of “doing well by doing good”, along with empirical evidence provided on the link between ESG performance and financial performance, we develop the following hypothesis.

H2: Corporate sustainability performance reflected in ESG scores can predict firm future financial performance.

In other words, the higher the ESG scores, the higher the firm future profitability.

4.3. The indirect relationship of ESG performance on companies’ non-financial performance

If ESG performance contains sustainability information, it can be used by investors to predict future financial performance, as stated in hypothesis 2. Prior studies suggest that committing to corporate responsibility activities can result in the increased stakeholders’ trust and satisfaction, and therefore improve not only financial performance, but also non-financial performance (Auer & Schuhmacher, Citation2016; Crifo et al., Citation2019; Fatemi et al., Citation2017). When the predicted value of financial performance contained ESG performance information, has an impact on companies’ non-financial performance, in this case, the financial benefits that the company gets from implementing ESG is the one that influence the companies’ non-financial performance. Thus, according to the legitimacy theory, that influence could be due to either symbolic strategy or the substantive strategy. In order to disclose the motivation behind the firms incorporating ESG-related activities, we use the notion of “doing good, by doing well”. As mentioned before, a positive relation between CSR and firm value is often referred to as “doing well by doing good” (Deng et al., Citation2013; Dowell et al., Citation2000; Flammer, Citation2015; Orlitzky et al., Citation2003). However, others point out that the relation may run the other way, that is, firms “do good when they do well” (Hong et al., Citation2012; Lys et al., Citation2015).

Borrowing the notion of “doing good by doing well”, we test the impact of predicted future financial performance that contains ESG information, on non-financial performance. we can identify the motivation of companies implementing ESG-related activities. If the relationship is positive, we can interpret that the motivation to implement ESG is to obtain financial benefits, and an increase in financial benefits encourages companies to engage more in ESG activities. ESG disclosure is used to measure non-financial performance. In this way, we test the indirect relationship of companies’ ESG performance and non-financial performance. Hence, the hypothesis is stated as follows:

H3: The predicted value of firms’ future financial performance that contains ESG performance information has a positive relationship with the firms’ non-financial performance.

In other words, ESG-related financial performance has a positive effect on ESG disclosures.

4.4. The effectiveness of law enforcement on companies’ non-financial performance

The fourth hypothesis is developed to test the motivation behind the ESG implementation that can increase firm financial performance and value, and in turn ESG-related future financial performance can increase the firm non-financial performance. If the predicted value of firms’ future financial performance that contains ESG performance information has a positive relationship with the firms’ non-financial performance, this relationship does not automatically lend to the substantive legitimacy strategy. It is still possible that the ESG implementation may be a symbolic strategy. To investigate further, we include government regulation that are enacted to encourage the Indonesian firms to implement ESG-related activities along with their business activities.

To accomplish this purpose, we observed the before-after relationship shown in hypothesis 3, whether there is a change in the relationship before and after the law enforcement by the regulators, namely POJK 51 and PROPER. The hypothesis is stated as follows.

H4: The predicted value of firms’ future financial performance that contains ESG performance information has a different relationship with the firms’ non-financial performance, before and after the law enforcement by the regulators.

In other words, ESG-related financial performance has a different relationship with ESG disclosures, before and after the law enforcement by the regulators.

The results will be used to evaluate the effectiveness of POJK 51 and PROPER. We also performed a specific analysis by dividing the sample into industry-specific companies. Because POJK 51 is intended more for the banking sector, while PROPER is intended for sensitive industries that are vulnerable to polluting environments. Furthermore, we can analyze the impact of two different regulatory approaches, narrow and broad, in encouraging companies to increase their non-financial performance.

5. Research design

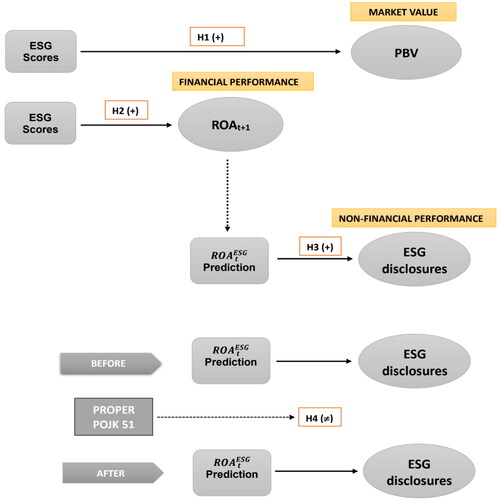

Our study attempts to analyse the nuanced process of ESG adoption and implementation in Indonesia by examining the financial and non-financial impacts in the context of two government policies, namely POJK 51 and PROPER. To accomplish this purpose we employ the conceptual framework shown in . First, we test the impact of ESG scores on market value measured by PBV. Second, the positive and significant impact of ESG on PBV implies that ESG scores contain information that can be used to predict firm future performance, measured by ROA. Third, the predicted value of ROA that contains ESG information (ESG-related financial performance) is expected to affect firm non-financial performance, measured by ESG disclosures. In this way, we expect that ESG-related future financial performance will encourage the firms to engage more on ESG activities, reflected on ESG disclosures. Fourth, to investigate further on the firm motivation behind implementing the ESG, we employ two existing government policies, namely POJK 51 and PROPER. By testing the change on the impact of ESG-related future financial performance on ESG disclosures, we can observe the impact before and after law enforcement. If before the enforcement of the regulations, the effect of ESG-related future financial performance is positive and significant on ESG disclosures, we can interpret that financial motivation affects the firm in engaging more in ESG activities. When the positive effect turns into insignificant after the law enforcement, it means that it is not the financial motivation anymore that influences the firm to engage more on ESG activities. Additionally, we also observe that the mean of firms’ ESG disclosures are significantly higher after the law enforcement. By analysing the effectiveness of POJK 51 and PROPER, the study can shed a light on what the regulation can do to shift companies’ motivation to engage more in ESG-related activities. The impact of two different regulatory approaches, narrow and broad, is further observed and analyzed.

5.1. Sample and data

We focus on all companies listed in the Indonesian Stock Exchange (IDX) from 2015 to 2022. outlines the sample selection process. We only employ companies that have consecutive ESG scores until 2022. Unbalanced-panel data is used to accommodate companies that have new ESG scores in the 2016–2022 period. The analysis was based on the collection of data for a period of the last 7 years (2016–2022). Throughout this period some firms had missing data for some variables, therefore, we turn out with an unbalanced panel data of 66 firms with 338 observations for Model 1, 61 firms with 271 observations for Model 2, and 27 firms with 133 observations for Model 3.

Table 1. Sample selection.

The time-series distribution of number of companies by year and by industry is presented in . The number of companies with ESG scores shows an increase from year to year. Likewise, the average of ESG scores and ESG disclosures also show an increase every year. This indicates that in terms of quantity and quality, Indonesia is a country that cares about ESG-related issues. To avoid survival bias, we only took companies that had consecutive ESG scores until the end of 2022. When looking at the number of companies in each industry, the Sensitive Industry ranks highest, followed by the banking industry for companies that have ESG scores. This is in line with the attention given by the Indonesian government to these two industries with the existence of POJK 51 for banking and PROPER for sensitive industries. Even though those two policies also have an impact for other industries, as well.

Table 2. Sample distribution of companies with ESG by year and industry.

shows the definition of each variable used in this research, including dependent, independent, and control variables. Most financial data and ownership structures are obtained from Osiris Database, while ESG disclosures are drawn from Bloomberg Database. ESG scores, cost of equity, CSR committee, and CGB Committee are obtained from Refinitiv-Thomson Reuters Database. In this research, ESG scores from Refinitiv are used to measure ESG implementation, while ESG disclosures from the Bloomberg database are employed to measure firms’ non-financial performance. While both Refinitiv and Bloomberg provide ESG-related information, their offerings differ in terms of the data they collect, the methodologies they use, and the types of insights they provide. Refinitiv’s ESG score focus on assessing a company’s overall ESG performance, while Bloomberg’s ESG disclosures focus on providing detailed information on specific ESG metrics and indicators. Previous study (Tahmid et al., Citation2022) employed Refinitiv’s ESG scores to capture the ESG implementation. As suggested by Alatawi et al. (Citation2023) ESG disclosures can be used as a measure of reporting quality that captures firms non-financial performance.

Table 3. Definition of variables.

The summary statistics of all variables employed in this study is presented in . The average ESG scores and ESG disclosure of companies included in the research sample were 50.84% and 42.05% respectively. This shows that the ESG rating of companies in Indonesia on average is still around 50%, which is not too high, although there are several companies that have the highest ESG scores and ESG disclosures of 88% and 73.87%, respectively. Therefore, this is the right time to capture and analyse the initial stages of the ESG adoption and implementation process in Indonesia, and the effectiveness of government intervention in accelerating ESG implementation, as well. The PBV ratio ranges between 0.170 and 82.440, with a mean of 3.700 indicating that the company’s shares are overvalued. Tobin’s Q which shows the company’s market performance ranges between 0.040 and 22.560 with a mean of 1.552. The cost of equity, which is a market indicator for measuring the risk of a company’s shares, in this research sample has a mean of 13.86%. ROA and ROE are used to measure profitability, which is the company’s financial performance. The mean of ROA and ROE for companies included in the research sample is 7.308% and 16.003%, respectively. The ROA and ROE range is quite wide, from -28% to 55%, and -254% to 238%, respectively. This indicates quite large variations in the financial performance of the companies included in this research sample. Ownership structure including family and state ownership of the companies in the sample is also considered as control variables (Kumar et al., Citation2022). Likewise for the CSR committee and Corporate Governance Board Committee which are considered to explain variations in the effectiveness of ESG implementation (Khatib et al., Citation2022).

Table 4. Summary statistics.

shows the Correlation Matrix of all main research variables employed in this study. The independent variables have low correlations, except for some variables that proxy the similar concepts. Most dependent and independent variables have high and significant correlation. Interestingly, the ESG scores and ESG disclosures have no correlation, which support the intended purpose in this study to proxy two different things, that are ESG implementation and ESG-related non-financial performance, respectively.

Table 5. Correlation matrix.

5.2. Statistical model

A panel data regression model has the specifications of pooled ordinary least square (OLS), Fixed Effect, and Random Effect models. As we employ the panel data regression, we expect to generate efficient estimates by setting control for heterogeneity of individual variables, collinearity, and robustness measures (Khaki & Akin, Citation2020). Reffering to the econometric model, there are some restrictions of unobserved heterogeneity problem which determines the time-variant variables of each company (Gormley & Matsa, Citation2014). Additionally, endogeneity problem may arise due to causality relationship between some independent variables (Wooldridge, Citation2002).

To estimate the impact of ESG scores on firm value, the following model (Model 1) is employed.

To predict the firm future financial performance with ESG scores, the following model (Model 2) is employed.

The Predicted value of and

are as follows.

where,

is predicted future financial performance of company i at time t, that contains ESG information, while

is predicted future financial performance of company i at time t that contains E information. The first one is employed to test before-after POJK 51, and the latter for before-after PROPER.

To test the impact of ESG-related and E-related financial performance, on firm non-financial performance, the following models (Model 3) are used respectively.

A generalized least squares approach is used to estimate our model. After implementing Hausman tests, most of our panel data required a random effects model. In panels of main results, we present both the output of the pooled OLS and the random effects model to compare the results of the regression coefficients. Most of the results are still comparable and the interpretation of the coefficients is not that different between the two alternative models.

6. Empirical results and discussion

6.1. Main empirical results

First, we present empirical evidence on the impact of ESG on firm value to verify whether the result is consistent with previous empirical evidence at national and global levels. shows the regression results of each individual ESG component and the combined ESG score on firm value as measured by PBV, with financial ratios and ownership structures used as control variables. The regression models shown in the table are pooled OLS regression and the best alternative model selected after performing a model specification test for unbalanced panel data. Tests of model specification performed to determine the best selected model are the Chow, Hausman, and Breusch Pagan Lagrange Multiplier Tests. An example of the model selection process is shown in the notes below . The coefficient regression outputs shown in pooled OLS and the alternative model in each regression model appear to point in the same predictive direction when explaining the effect of ESG scores and its components on firm value. The results show that the ESG scores have a positive and significant effect on firm value as measured by PBV. This positive effect also occurs for each individual ESG component, except the G component. The insignificant result of G component is inconsistent with the findings of Xie et al. (Citation2019) and Velte (Citation2017). They found that governance performance had the strongest impact on financial performance compared to environmental and social performance. Except for G component, this result is generally consistent with some previous studies (Delvina & Hidayah, Citation2023; Junius et al., Citation2020) that were conducted in Indonesia with a sample taken from years before 2022. Empirical evidence at the global level also confirms the result (Aboud & Diab, Citation2018; Ahmad et al., Citation2021; Chouaibi et al., Citation2021; Deng et al., Citation2023; Elmghaamez et al., Citation2023; Melinda & Wardhani, Citation2020; Sinha Ray & Goel, Citation2023; Xie et al., Citation2019). Thus, this empirical result supports the first hypothesis of this study. Companies that focus on ESG aspects tend to achieve better corporate value. The result also support the stakeholders theory. The empirical evidence shows that stakeholders in Indonesia are concerned with the companies implementation of ESG-related issues. There is a growing awareness of investment sustainability among Indonesian stakeholders as reported by Prasidya (Citation2020) that documents high returns of ESG investments, as measured by the Sustainable and Responsible Investment (SRI) - KEHATI Stock Index that focuses on companies that meet ESG criteria.

Table 6. The impact of ESG scores on market value.

Second, reports the regression of each ESG component and the combined ESG scores on future firm profitability, as measured by ROA. As in the previous procedure, we first perform a model specification test to determine the best model for the unbalanced panel data regression. The regression results we report are in the form of pooled OLS along with the alternative model according to the model specification tests, presented below . All reported regression models show consistent results for all effects of main independent variables, namely ESG combined and its individual components, on ROA. All regression coefficients of ESG combined and its individual components show the same direction, which are positive and significant. These results indicate that ESG scores and its individual components can be used to predict future profitability as measured by ROA. Additionally, almost all control variables also have a significant effect with a consistent predictive direction on future profitability. The regression models have an R-squared of around 0.30, indicating the model’s predictive ability in explaining the variation of firms’ future profitability. In general, these results are consistent with the previous studies that ESG implementation is a source of corporate competitiveness (Cao et al., Citation2019; Waddock & Graves, Citation1997). Therefore, ESG information is useful in predicting future financial performance. Thus, the second hypothesis of this study is supported by this finding, that corporate sustainability performance reflected in ESG scores can predict future financial performance. This prediction is also consistent with resource-based theory (Bhandari et al., Citation2022; Surroca et al., Citation2010) and the notion of "doing well by doing good" (Deng et al., Citation2013; Dowell et al., Citation2000; Flammer, Citation2015; Liang & Renneboog, Citation2017; Orlitzky et al., Citation2003).

Table 7. ESG predictability on financial performance.

Third, this study also provides empirical evidence on the impact of ESG implementation not only on the firms’ market value and financial performance, but also on the firms’ non-financial performance. Existing studies have often neglected the non-financial measures. The firm’s non-financial performance is defined as the companies’ attempts to get involved in ESG-related activities with the aim of being able to contribute to society beyond their financial benefits that the companies may get. presents the regression results of the impact of ESG-related future financial performance on the firm’s non-financial performance, measured by ESG disclosures. The ESG-related future financial performance is estimated using a prediction model performed to test the second hypothesis. is a measure of environmental-related future profitability, while

is a measure of ESG-related future profitability. The impact of ESG-related future financial performance on ESG disclosures reveals the company’s motivation in engaging more on ESG-related activities. A positive and significant regression coefficient can be interpreted as a financial benefit motive that encourages the company to engage more in ESG activities. shows that for all the regression coefficients of

,

,

, and

have a positive and significant effect on ESG disclosures. This finding suggests that companies’ motivation to engage in ESG-related activities is determined by the financial benefits they receive from ESG implementation. CSR committee and CGB committee are employed as control variables in this study, following the studies of Elmghaamez et al. (Citation2023). CGB_Com has a positive and significant effect on ESG_disc in all REM-GLS regressions suggested by model specification tests. CSR_Com has a positive and significant effect only in Model 1 and 3. Thus, the third hypothesis is also supported. The empirical evidence provided in this study confirm prior studies’ suggestions that committing to corporate responsibility activities can result in the increased stakeholders’ trust and satisfaction, and therefore improve not only financial performance, but also non-financial performance (Auer & Schuhmacher, Citation2016; Crifo et al., Citation2019; Fatemi et al., Citation2017). Thus, this evidence is consistent with the prediction of legitimacy theory, although we cannot distinguish the source of legitimacy from symbolic or substantive strategies. This result also fulfils the prediction of the notion of companies that “do good when they do well” (Hong et al., Citation2012; Lys et al., Citation2015). In addition, this study also confirms that the effect of ESG implementation on companies’ non-financial performance is indirect because ESG-related financial performance is the first to affect companies’ non-financial performance.

Table 8. The impact of ESG-related financial performance on non-financial performance.

The final results are to provide empirical evidence whether the law enforcement, namely POJK 51 and PROPER can change or improve the companies’ motivation in engaging more in ESG-related activities. Before-after event study is employed to investigate the impact of the two implemented policies. The cut-off year is 2020 for POJK 51 and 2019 for PROPER. First of all, we observed the difference between two means of ESG disclosures before and after the law enforcement, as reported in for the POJK 51 and for PROPER. In both cases, the mean of ESG disclosures before and after the law enforcement are significantly increased with the level α of 1%. Whether the motivation of companies implementing ESG disclosure changes or improves before and after the implementation of the law enforcement is the purpose of testing the fourth hypothesis.

Table 9. The impact of ESG-related financial performance on non-financial performance before and after the POJK 51.

Table 10. The impact of ESG-related financial performance on non-financial performance before and after PROPER.

shows the impact of ESG-related financial performance on non-financial performance before and after the POJK 51 mandatory sustainability reporting has to be provided since the additional provision of OJK letter No. S-264/D.04/2020 of November 4, 2020. Under the full sample, we can observe that the regression coefficient before the POJK 51 is 1.080 and significant at the level α of 1%. After the POJK 51, the regression coefficient decreases to 0.832 and significant at the level α of 10%. The slope difference is not statistically significant. Since POJK 51 is intended more to financial industry, we have to observe further by dividing the sample into two industry categories which are financial and non-financial industry. There are no statistically differences on regression slopes in both industry categories before and after the POJK 51. However, by taking a closer look in financial industry category, we found that the regression coefficients changed from 0.359 to 1.194, and from statistically not significant to significant at α level of 5%, respectively. We can interpret that after POJK 51, the ESG-related financial performance has a positive influence on non-financial performance. As mentioned before, POJK 51 is categorized in a narrow approach regulation characteristic which is intended to provide investors with sustainability reporting for investment decisions. Interpreting the result through the lens of legitimacy theory, we can observe through the change in regression coefficients that the motivation of the financial industries to comply with the law is to gain supports of critical stakeholders (Doh et al., Citation2010). Failure to meet essentially institutionalized standards and social norms can threaten firms’ legitimacy, resources, and survival, since social conformity leads to improved access to external resources (Bansal, Citation2005; Suchman, Citation1995). In the case of banking industry, legitimacy can be earned by avoiding extending credits to the businesses that pose risks to the environment, social, and governance. Combining with the notions of “doing good by doing well”, we observe that the positive and significant on coefficient regression after the POJK 51 confirms that the motivation for engaging more on ESG activities (doing good) is encouraged by gaining financial benefits through the ESG implementation (doing well). This result confirms the previous findings (Hong et al., Citation2012; Lys et al., Citation2015). Even though POJK 51 has not been implemented for long that is initiated in 2017 and required in 2020, its preliminary impact can be observed. The empirical evidence in the financial industry sector provides a support to hypothesis 4. However, we cannot conclude whether the source of the legitimacy coming from symbolic or substantive strategy, because after the law enforcement, financial benefits still influence the non-financial performance.

reports the impact of ESG-related financial performance on non-financial performance before and after the reinforcement on the PROPER implementation in 2019. PROPER has become mandatory for targeted polluted companies and the online reporting has to be done online with SIMPLE since 2019. The regression coefficient of E-related financial performance on ESG disclosures, under the all sample, before the PROPER is 1.276 and significant at the α level of 1%, while after the PROPER the coefficient is 1.018 and significant at the α level of 5%. Even though the coefficient is slightly decrease after the PROPER but the difference is not statistically significant. Since PROPER is intended for the sensitive industry, then we observe the sensitive industry sample to compare the regression coefficients before and after the PROPER. The regression coefficient before the PROPER is 2.231 and significant at the α level of 1%, after the PROPER the coefficient reduces to 0.919 and statistically insignificant. The difference between two slopes shows a significant change at the α level of 10%. For the sample of non-sensitive industry, there is no slopes difference before and after the PROPER. The regression coefficients are not statistically significant both before and after the PROPER. We can see that before the PROPER, E-related financial performance motivate the sensitive industry companies to increase their non-financial performance to engage more on the ESG-related activities, measured by ESG disclosures. After the PROPER reinforcement, when the targeted companies are mandatory to do the environmental reporting through SIMPLE according to the standard measurements, the E-related financial performance no longer has an impact on the increase of non-financial performance. We can interpret that the change in companies’ motivation reflects the effectiveness of the PROPER when it becomes mandatory to targeted companies in the sensitive industry. Before the PROPER, companies are motivated to do good when they can do well, financially, this result confirms previous studies on “doing good by doing well” (Hong et al., Citation2012; Lys et al., Citation2015). After the PROPER, the law re-enforcement is able to shift the companies’ motivation to involve in legitimacy substantive strategies. They involve fundamental changes in companies’ goals, behaviours, and practices to meet the expectations and needs of societal stakeholders (Ashforth & Gibbs, Citation1990). In the PROPER context, companies can take environmental actions to address E-related issues by adopting sustainable activities that can lead to get outcomes and value. The adoption of comprehensive environmental actions requires significant investment and resources. In fact, the enactment of the PROPER occurred in the Covid period where many major social problems reside, and when “do good” and “do well” are contradictory. However, the result of this study still confirms Karnani’s (Citation2010) suggestion that in the situation where there is a conflict between corporate profit and social welfare, strong behavior needs to be curbed with government regulation. In this case PROPER seems effective in intervening the company’s behavior to achieve the interest of society especially related to the environmental issues. Therefore, the empirical evidence provided before and after the PROPER in sensitive industry sample supports hypothesis 4 of this study.

Even though the regression output before and after the POJK 51 and PROPER resulted on the different directions, the interpretations of the empirical evidence are in conformity with the existing regulatory approaches of sustainability reporting. As mentioned before, the regulatory approaches fall along a spectrum between two extremes, which are characterized as narrow and broad approach. POJK is a narrow approach therefore the effectiveness is to motivate the companies to “do good by doing well” by emphasizing on the ESG process through the sustainability reporting. PROPER approach is broader, it can motivate the companies to focus on the outcomes of the ESG process. Thus, compared to POJK 51, PROPER is one step ahead in shifting the companies’ motivation to increase the non-financial performance. The success of PROPER implementation is not only based on the mandatory environmental reporting through SIMPLE, but also the way the ranking results are published. The results are distributed through the website of the Ministry of Environment and Forestry and various media publications. Because of the extensive involvement of stakeholders, the PROPER program is also known as public disclosure of environmental performance. Therefore, monitoring the PROPER program is not only done by the regulator, but also by market and society. Especially if the information is obtained from a trusted source. Environmental regulators have integrity and authority to access information that is valid and can be taken into account. This information is very effective in building companies’ image and reputation, especially if the information is conveyed in a simple and easy-to-remember form. In other words, targeted companies can be quickly and decisively praised or punished with only one weapon, which is information.

6.2. Robustness tests

We performed robustness test of the primary models used to interpret the findings of this study. We want to ensure that the interpretation is robust to any changes in the main research variables. shows the effect of ESG scores on other measures of market variables. We replace PBV with other measures, namely COE and Tobin’s Q. COE measures the cost of equity, which is expected to have a negative relationship with ESG implementation. The higher the ESG score, the lower the companies’ equity risk. Tobin’s Q is a measure of market performance and is expected to have the same association as with ESG and PBV. The regression coefficients shown in are consistent with the expectations. Therefore, Model 1 and Model 2 are not sensitive to changes in the dependent variable.

Table 11. The impact of ESG scores on other measures of market values.

shows the robustness test for Model 3, we used another measures of company performance to measure the predictive value of ESG on future financial performance. We replace ROA with ROE. The Results presented in in column (1), (2), (3), and (4) are compared with the results in . We observed that all of the regression coefficients of E, S, G, and ESG in have the same direction as those of in . The results of in column (5), (6), (7), (8), are compared with the results of . We see that the results are similar and all of the regression coefficients have the same direction and significant. Thus, Model 3 is not sensitive to change in the measurement of dependent variable.

Table 12. The impact of ESG scores on financial performance and the impact of ESG-related financial performance on non-financial performance.

In this study, we also performed the endogeneity test of ESG as the independent variable along with PBV and ROAt +1 as the dependent variables. ESG is suspected of having a problem with its endogeneity. Therefore, we performed the Dubin, Hausman and Wu test for endogeneity using the two-stage least squares method (Wooldridge, Citation2002). The result is shown in , the insignificant regression coefficient of the error term from the first stage concludes that endogeneity is not present in model 1 and 2.

Table 13. Two-stage least squares.

reported VIF values of all the independent variables employed in Model 1, 2, and 3. All the VIF values are closed to 1, indicating the absence of a potential multicollinearity problem in the estimated model.

Table 14. Multicollinearity test - VIF.

7. Summary and conclusion

In the recent literature, many studies have raised an issues of the impact of ESG scores on corporate financial performance and value. However, the impact of ESG scores on non-financial performance has not been thoroughly explored. The purpose of this study is to analyse the nuanced process of ESG implementation by conducting a study in a country that is still in the process of developing ESG aspects. Using an unbalanced panel data model for Indonesian listed companies from 2016 to 2022, this study provides empirical evidence on the indirect effect of ESG implementation on companies’ non-financial performance. Consistent with stakeholder theory, this study found a positive effect of ESG implementation on corporate values. The predictability of ESG performance in future financial performance is consistent with resource-based perspectives. ESG-related financial performance has a positive and significant impact on non-financial performance as measured by ESG disclosure. Companies are willing to disclose and increase their commitment to ESG activities if these activities improve their financial performance.