Abstract

This study assesses how entrepreneurship education influences the entrepreneurial intentions and employability of students. It also investigates the mediation effect of entrepreneurial intentions on the relationship between entrepreneurial education and employability, as well as the direct effects on employability. In this research, a quantitative method was used to gather data from 397 university students through a survey questionnaire measured on a seven-point Likert scale using a convenience sampling method. We utilized structural equation modeling (SEM) to examine the data. A CMV model was used to evaluate the model’s fitness, validity, reliability and of the data, and an SEM technique was used to test the hypotheses. The study found that entrepreneurship education could boost students’ employability as well as their desire to start their own businesses. It shows how important entrepreneurship education is for learning the skills and knowledge needed to start a business. The study also suggests that having entrepreneurial intentions can enhance one’s employability. This study reveals a heightened understanding of how entrepreneurship education impacts on entrepreneurial intention and employability. These insights can guide improvements in entrepreneurship programs to align with local employment needs. Moreover, the identified mediator, entrepreneurial intentions, presents a targeted opportunity for intervention, suggesting practical ways to cultivate entrepreneurial skills and mindset, ultimately enhancing employability prospects in the region.

IMPACT STATEMENT

Unlocking the doors to career success and personal enterprise, our study delves into the transformative power of entrepreneurship education. We discovered that not only does such education enhance employability among students, but it ignites a passion for entrepreneurship itself. Picture a world where learning to start your own business not only opens doors to self-employment but also boosts your overall job prospects. Our findings shed light on the vital role entrepreneurial intentions play in this journey, offering a roadmap for educators and policymakers to refine programs that not only meet local employment needs but also foster a mindset of innovation and empowerment. Join us in envisioning a future where education becomes the key to unlocking both traditional job opportunities and the entrepreneurial spirit within us all.

1. Introduction

Nowadays, technological advancement and globalization rapidly changing the job market all over the world (Masud et al., Citation2021; Nhleko & Westhuizen, Citation2022). Particularly, the COVID-19 epidemic has resulted in far-reaching consequences on the worldwide labor market, upward trend in the rate of unemployment and creating an unstable social atmosphere that has negatively impacted university students’ career chances (Barba-Sánchez et al., Citation2023; Gazi et al., Citation2023; Zhu et al., Citation2022). The current scenario demands a boost in entrepreneurship education and employability skills which would not only help people start their own businesses but also make sure they have jobs, in order to combat the rising unemployment in the country (Pardo-Garcia and Barac, Citation2020; Ramadani et al., Citation2022). The Covid-19 pandemic has heightened unemployment rates in Bangladesh, as reported by the International Labor Organization (ILO) in 2022, with a 0.6% increase (Rahman et al., Citation2023). Despite annual graduations, only a small percentage of students aim to establish enterprises, preferring paid employment (Porfírio et al., Citation2023). The government’s 2021–2041 Perspective Plan (Vision 2041) targets poverty eradication and economic elevation (Rahman, Citation2023, Zakaria et al., Citation2023). The situation is concerning, prompting a focus on entrepreneurship. Opting for self-employment is the most effective alternative to seeking waged employment for sustaining oneself (Al‐Mamary & Alraja, Citation2022; Gazi et al., Citation2022).

Entrepreneurship acts as a catalyst for both economic development (Amorós et al., Citation2021; Barba-Sánchez et al., Citation2023; Porfírio et al., Citation2023) and the promotion of sustainable development (Bouncken et al., Citation2022; Porfírio et al., Citation2023). Entrepreneurship is considered an effective and promising strategy for addressing challenges such as employability (Al‐Mamary & Alraja, Citation2022; Molina-Ramírez & Barba‐Sánchez, Citation2021). Entrepreneurship can not only assist jobless students in finding employment but also aid to create additional jobs (Kostakis & Tsagarakis, Citation2022; Rahman et al., Citation2022). It is vital to gain exposure to entrepreneurship education in order to gain expertise and capabilities associated with entrepreneurship, in addition to developing other characteristics that are linked with becoming an entrepreneur (Vuorio et al., Citation2022; Zhang et al., Citation2014). In both developing and developed economies, graduate-level entrepreneurship is considered as important to a country’s ability to compete and as a powerful tool for reducing regional imbalances (Paul & Shrivastava, Citation2015), which helps the country grow on both a local and a national level (Gupta, Citation2022; Molina-Ramírez & Barba‐Sánchez, Citation2021; Nabi et al., Citation2017; Ramadani et al., Citation2022). It is essential for boosting economic growth, creating revenue, and creating jobs. An array of studies has examined the influence of entrepreneurial education on graduates’ intent to start their own businesses and on the acquisition of necessary skills (Bazan, Citation2022; Nabi et al., Citation2017; Scott et al., Citation2017). In a nutshell, increasing the stability of the economy through the creation of new jobs may be facilitated by entrepreneurial efforts.

Many academics believe that providing students with an education in entrepreneurship is one of the most effective ways to get them ready for the unstable and ever-changing job market (Killingberg et al., Citation2020). Nhleko and Westhuizen (Citation2022) recommended that universities incorporate Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) into entrepreneurship education to equip students with job-ready abilities. This emphasizes the importance of including the 4IR in the entrepreneurship education curriculum.

Few studies have evaluated the effect of entrepreneurship education on the employability of graduates in the job market (Mittal & Raghuvaran, Citation2021). A person’s employability—their skill set, body of knowledge, and level of competency—are all crucial factors in their success in the job market. Individuals are considered employable if they have the ability to join the workforce, adapt to, and thrive in, professional settings (Mezhoudi et al., Citation2023). The notion of entrepreneurial intentions is intricately linked to the notion of employability (Hodzic et al., Citation2015). Increasing entrepreneurial intentions is viewed as a way out of the issue of poor employability by some scholars (Cui et al., Citation2021; Wang et al., Citation2021). One’s personal aspirations towards entrepreneurship are more likely to try new things and face problems that call for a wide range of abilities and expertise (Mittal & Raghuvaran, Citation2021). People with strong entrepreneurial intentions are those who are equipped with the values, attitudes, knowledge, and abilities necessary to adapt to the ever-shifting demands of the business world and the job market (Hossain et al., Citation2021; Tentama & Yusantri, Citation2020).

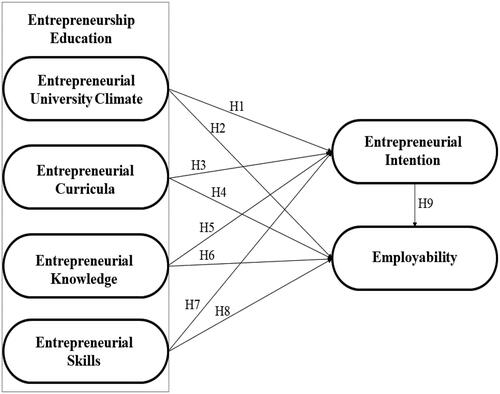

This topic is less researched and less comprehensive in the context of Asian countries like Bangladesh. The literature has identified certain shortcomings in the study of the impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurship intentions and employability. Firstly, based on our current knowledge, there is no single study that establishes a direct connection between the suggested variable in a specific study. Previous studies evaluated these variables separately e.g. (Adu et al., Citation2020; Mittal & Raghuvaran, Citation2021). Secondly, the concept that entrepreneurial intention could enhance employability, which has been infrequently studied. Thirdly, the mediating role of entrepreneurial intention in the relationship between entrepreneurship education and employability is unique and still rare, especially in the context of university students. This research aims to address these gaps by empirically investigating this impact with a unique model. Policymakers, educators, and academics in developing countries will greatly benefit from the study’s findings, specifically in relation to entrepreneurship education, as it will demonstrate the significance of such education in equipping university students with the necessary knowledge, confidence, and motivation to become successful business owners and enhance their employability. The study tries to find answers to the following questions: RQ1: Does entrepreneurship education in Bangladesh promote entrepreneurial intentions? RQ2: Does entrepreneurship education in Bangladesh increase the employability of students in universities? RQ3: Whether entrepreneurial intentions have a mediating effect in our model or not?

In our research, we employed structural equation modeling to examine how entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurial intentions, and employability are interconnected. We analyzed data from 397 participants, and our research fills a gap in the current literature on entrepreneurship education. Our findings offer both theoretical and empirical insights, and we suggest a framework for future investigations.

The following section of the paper conducts an evaluation of the current literature on the issue before presenting the study’s proposed research model and hypotheses. The study finishes with a discussion of the ramifications of the findings as well as a succinct explanation of the research methodology and empirical data. This investigation ultimately contributes to our comprehension of how entrepreneurship education affects employability and proposes ideas for future study.

2. Literature review

2.1. Theoretical ground and research model

Entrepreneurship education encompasses a wide array of methodologies, including causal and linear planning, mindset cultivation, and process-oriented approaches. However, a definitive framework for associating specific outcomes with distinct types of entrepreneurship education remains elusive (Cui et al., Citation2021; Coetzee et al., Citation2016). An influential factor in the efficacy of entrepreneurship education is the individual’s intention to become an entrepreneur (Bozward et al., Citation2022). Current research is mostly about how Entrepreneurship Education (EE) affects entrepreneurial intentions (EI). This research often uses the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) (Ajzen, Citation1991) and the Entrepreneurial Event Model (EEM) (Shapero & Sokol, Citation1982), which are both based on theories of motivation. TPB is widely employed in the social and behavioral sciences to explore how entrepreneurship education influences students’ inclination to embark on entrepreneurial ventures. Known for elucidating intents and behaviors, TPB particularly shines in the realm of business initiation (Uddin et al., Citation2022; George & Bock, Citation2011).

As demonstrated by Krueger and Carsrud (Citation1993), the application of TPB gauges the likelihood of engaging in a particular behavior. This adaptable framework provides insights into the motivations underlying specific behaviors while accommodating personal and external factors (Al‐Mamary & Alraja, Citation2022; Entrialgo & Iglesias, Citation2016). Notably, TPB stands as one of the foremost psychological theories for understanding human behavior. According to TPB, behavioral display hinges on intent. It’s worth noting that TPB evolved from the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA), a concept introduced by Fishbein and Ajzen (Citation1975) that highlighted how attitudes toward behaviors influence intentions to undertake them. In TPB, an entrepreneur’s EI is shaped by attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control (Hair et al., Citation2012). However, EI is a multifaceted phenomenon (Wang et al., Citation2023), necessitating the exploration of diverse dimensions that can enhance the TPB model.

Our research introduces a specific modification to TPB, focusing on attitudes tailored to the entrepreneurial environment within a university. Our investigation aims to gauge individuals’ perceptions of the university’s entrepreneurial support, endorsement of entrepreneurial values, and the pros and cons associated with entrepreneurial engagement in an academic context. In traditional TPB, subjective norms encompass social pressure or expectations tied to a behavior (Al‐Mamary & Alraja, Citation2022). Our study innovatively substitutes conventional subjective norms with perceptions of entrepreneurial norms within the university milieu. We intend to evaluate how individuals perceive the backing, encouragement, and expectations related to entrepreneurship from peers, faculty, mentors, and influential stakeholders within the university. Furthermore, the conventional TPB’s notion of perceived behavioral control pertains to an individual’s self-assessed ability to execute a specific behavior (Al‐Mamary & Alraja, Citation2022; Karimi et al., Citation2016). In our work, we adapt perceived behavioral control to reflect confidence in entrepreneurial capabilities nurtured through university resources, courses, training, and experiences concerning entrepreneurial knowledge and skills. Hence, TPB offers a valuable framework for investigating the interplay between entrepreneurial intention (Wang et al., Citation2023), knowledge, skills, and other pertinent factors. This model aids researchers in comprehending the elements steering individuals toward entrepreneurship while informing the design of interventions to foster entrepreneurial pursuits (Barrios et al., Citation2021). Yet, by grounding this theory in the aspects of operation, this investigation makes a contribution to the field of TPB and entrepreneurial education research in the university setting.

2.2. Entrepreneurship education (EE) and entrepreneurial intention (EI)

Entrepreneurship education is a structured educational program that focuses on instructing students in the essential skills and attitudes required for entrepreneurship (Karimi et al., Citation2016). The key objective is to enhance students’ comprehension of entrepreneurship, develop their entrepreneurial competencies, and promote an entrepreneurial culture and mentality at personal, societal, and community levels (Ramadani et al., Citation2022). Entrepreneurship is a deliberate and systematic process (Loi et al.,Citation2016; Martínez-Cañas et al., Citation2023). Ajzen (Citation1991) defines intention as the willingness of an individual to perform a specific behavior and posits that it directly affects behavior. He contends that the greater the level of intention to participate in deliberate actions, the higher the probability that the person will execute it. Research shows that teaching individuals about entrepreneurship has a positive effect on their attitudes and skills, making them more likely to try to succeed in entrepreneurial activities., as suggested by Zhao et al. (Citation2005) and Mahmood et al. (Citation2020). Participation in intensive entrepreneurship education programs is directly correlated with an increase in the likelihood that an individual will pursue entrepreneurship (Ruiz‐Palomino & Martínez-Cañas, Citation2021; Heuer & Kolvereid, Citation2014). These relationships, on the other hand, are not so simple (Volery et al., Citation2013). Entrepreneurship programs aid students in developing skills related to entrepreneurial traits, such as modeling, mastering experience, social persuasion, and self-assessment (Westhead & Solesvik, Citation2016).

2.3. Entrepreneurship education (EE) and employability (EM)

Employability is frequently defined as a person’s potential in the national and/or international labor market. Three perspectives on this potential have been offered: (I) as personal qualities that boost employment potential; (II) as prospects for work recognized by the individual; and (III) as career adjustments as a means of realizing employment potential (Van Harten et al., Citation2021). Tertiary education can establish a reliable route to employment by establishing a suitable workplace with the necessary infrastructure, skills, and methods (Mittal & Raghuvaran, Citation2021). According to the ‘Entrepreneurship Action Plan, 2020’ launched by the European Commission, one of its primary initiatives was based on the premise that entrepreneurship is a teachable skill and that encouraging it in educational institutions has a positive impact. Research has shown that when young people participate in programs focused on entrepreneurship that assist individuals in developing their skills, knowledge, and attitudes, 15% to 20% of them start businesses three to five years after graduation. However, without such programs, the ratio drops to only 3% or 5% (Pardo-Garcia and Barac, Citation2020). According to Costa et al. (Citation2017), there is substantial evidence in the literature that establishes a direct and positive relationship between entrepreneurial education and the employability of graduates.

Entrepreneurship programs assist students in acquiring abilities associated with entrepreneurial characteristics like creating models, gaining expertise, effective communication, and evaluating oneself (Costa et al., Citation2017; Karimi et al., Citation2016). Individuals who possess enterprising skills are typically viewed as more desirable job candidates than those who lack such skills. As many of these skills align with entrepreneurial behaviors, it can be inferred that individuals with a greater natural inclination toward entrepreneurship are likely to exhibit greater levels of enterprising behavior (Malik et al., Citation2023; Rae, Citation2007). This, in turn, could enhance their employability and increase their chances of securing higher-level employment opportunities in the future. Employers value graduates with transferrable abilities such as teamwork, adaptability, strong communication, positive negotiation, etc (Scott et al., Citation2017).

2.4. Hypotheses development

2.4.1. Entrepreneurial university climate (EUC)

The formation of individuals’ beliefs, values, and attitudes is influenced by the social and cultural environment, thus impacting their behavior (Barral et al., Citation2018). ‘Entrepreneurial University Climate’ can be described as the environment, culture, and circumstances of a university that encourage and support entrepreneurial efforts, innovation, and the development of a startup-oriented and entrepreneurial mindset among students, faculty, researchers, and staffIn their study. EUC, grounded in the TPB, not only positively influences entrepreneurial intentions but also enhances employability. Sherkat and Chenari (Citation2020) discovered a notable and positive correlation between an entrepreneurial university climate and the goal intention of university students. According to Oftedal et al. (Citation2017), having specific values and standards in universities possesses the capacity to foster student involvement in entrepreneurial endeavors, resulting in positive outcomes. EUC encourages entrepreneurial intent by providing resources, guidance, and networking opportunities. Due to the encouragement and resources available at universities, it is observed that students have a higher propensity to contemplate initiating their own enterprises or embracing a more entrepreneurial mindset. (Bergmann et al., Citation2018; Salamzadeh et al., Citation2022). Therefore, universities must cultivate a supportive culture that fosters a passion for entrepreneurship and identifies potential business opportunities for all members (Sancho et al., Citation2021). Similarly, the EUC provides individuals with the necessary knowledge, abilities, and experiential insights that are crucial for entrepreneurship (Bazan, Citation2022; Salamzadeh et al., Citation2022), hence enhancing the employment opportunities for students. It equips them with valuable competencies and an entrepreneurial mindset, preparing them for various career paths, including entrepreneurship and intrapreneurship within organizations (Bergmann et al., Citation2018). This suggests that fostering entrepreneurship within academic institutions can lead to beneficial outcomes for students and graduates.

H1:

EUC Positively Affects EI

H2:

EUC Positively Affects EM

2.4.2. Entrepreneurial curricula (EC)

Fayolle et al. (Citation2006) conducted a novel study to conceptually understand how entrepreneurship education affects students’ willingness to start enterprises. Using Ajzen’s (Citation2005) TPB framework, the authors looked into the relationship between entrepreneurship education and students’ intention to become entrepreneurs and discovered a substantial correlation between perceived behavioral control or self-efficacy and a three-day entrepreneurship program that concentrated on appraising new venture concepts. Several research (e.g. Ahmad et al., Citation2018; Iwu et al., Citation2021) have linked student entrepreneurship intentions more and more to how relevant and adequate they think course material is. Passaro et al. (Citation2018) reported that EC promotes EI among students by exposing them to entrepreneurial principles and practices. Integration of EC in educational institutions equips students with innovative concepts and professional skills. Learning about business planning, opportunity identification, innovation, and risk management inspires students to pursue entrepreneurship, cultivating a stronger entrepreneurial intention (Foss & Klein, Citation2020; Salamzadeh et al., Citation2022). Charney and Libecap (Citation2000), performed a comparison between students who chose courses that included entrepreneurship and those that did not. The authors came to the conclusion that students whose courses focused on entrepreneurship modules were more likely to get a full-time job with a company. Furthermore, EC enhances students’ employability by cultivating a diverse range of transferable skills highly valued in the job market, including creativity, problem-solving, adaptability, leadership, and opportunity recognition (Foss & Klein, Citation2020). By this student improves their employability prospects, positioning themselves as desirable candidates for both entrepreneurial ventures and traditional employment opportunities (Costa et al., Citation2017).

H3:

EC positively affect EI

H4:

EC positively affect EM

2.4.3. Entrepreneurial knowledge (EKN)

By entrepreneurial knowledge, we mean an awareness of and familiarity with entrepreneurship and the crucial role that entrepreneurs play in advancing economic development and social progress (Christian et al., Citation2020). Karyaningsih et al. (Citation2020) made the argument that the entrepreneurial knowledge impacted by entrepreneurship education. Having knowledge in entrepreneurship can provide individuals with the essential qualities and skills needed to create and run their own businesses. This includes fostering an innovative and creative mindset, promoting risk-taking, improving communication skills, providing knowledge of science and technology, and instilling a strong sense of ethical business practices (Ibrahim & Soufani, Citation2002). According to Christian et al. (Citation2020), by enhancing students’ knowledge and self-confidence, entrepreneurship education should enhance the possibility of more entrepreneurs. Moreover, entrepreneurial knowledge fosters a proactive and entrepreneurial mindset, which is increasingly sought after by employers (Lim et al., Citation2021). This mindset encourages individuals to take initiative, think creatively, and they are ready to take well-considered chances in order to accomplish their objectives employers are often attracted to candidates who possess such qualities, as they are generally more self-motivated, resilient, and adaptable to change. Therefore, it is crucial to provide individuals with the essential entrepreneurial knowledge to foster economic progress and societal advancement while instilling the skills and mindset required creating and managing successfully businesses as well as acquiring employability.

H5:

EKN positively affects EI.

H6:

EKN positively affects EM.

2.4.4. Entrepreneurial skills (ES)

The abilities required for transforming ideas into tangible results are referred to as entrepreneurial skills (Christian et al., Citation2020). Entrepreneurship has become a popular topic in higher education, with many colleges and universities offering courses on the subject. As a result, there has been an increase in the amount of entrepreneurship-related research and new thoughts incorporated into the field (Mittal & Raghuvaran, Citation2021). The courses offered have extended in terms of both contents and specialized skills, with new ideas being incorporated both vertically and horizontally (Malik et al., Citation2023, Nordin et al., Citation2023)). Entrepreneurship skills turn ideas into action. They are taught in higher education to develop a mindset and attitude towards entrepreneurship. This goes beyond personality traits (Christian et al., Citation2020). Entrepreneurial education has been linked to better graduate employability. In light of changes in the job market, entrepreneurship programs now emphasize teaching skills that enhance students’ employability, such as self-awareness, analytical thinking and problem-solving, adaptability, communication, collaboration, and resource management. This strategy aims to cultivate students who are creative, versatile, and able to make effective use of available resources (Costa et al., Citation2017). According to Scott et al. (Citation2017), employers have a tendency to favor job applicants who possess entrepreneurship skills such as effective communication, adaptability, teamwork, and positive negotiation abilities. In a comparative study by Charney and Libecap (Citation2000), students who had taken courses with entrepreneurship components were found to have a higher likelihood of being employed in full-time positions and demonstrated greater levels of self-esteem, team spirit, morale, and job satisfaction in individuals with entrepreneurship education compared to those without (Foss & Klein, Citation2020).

H7:

ES positively affects EI.

H8:

ES positively affects n EM.

2.4.5. Entrepreneurial intention (EI) and employability (EM)

As we just covered in the previous part, entrepreneurship education can strengthen individuals’ intentions to create and run their own enterprises by arming them with the knowledge, abilities, and mentality needed to do so. Additionally, there is a close relationship between entrepreneurial intentions and employability (Hodzic et al., Citation2015). However, based on our knowledge, there is no single study that demonstrates the mediating effect of entrepreneurial intention in the relationship between EE and EM. But authors believe that individuals with a significant aspiration to initiate their own enterprises usually exhibit specific characteristics, including entrepreneurial principles, mindsets, expertise, and skills that enable them to adjust to changing requirements in the employment industry. Increasing the inclination towards entrepreneurship is seen as a viable solution to tackle the issue of poor job prospects (Martínez-Cañas et al., Citation2023; Tentama & Yusantri, Citation2020). These abilities can increase a person’s attractiveness to employers, increase their capacity to adapt to shifting employment marketplaces, and enhance their possibilities for overall career advancement (Van Holm, Citation2021). Therefore, we conducted trials to examine the effect of entrepreneurial intention on employability directly as well as its role in fostering a beneficial mediating link between entrepreneurship education and employability.

H9:

EI mediate the relationship between EE and EM.

Drawing from the discussion of theory and the development of hypotheses, the current study has come up with the following conceptual framework ().

3. Methodology

3.1. Measurement instruments

This study is definitive in nature, with hypotheses developed to validate the relationship between variables. To evaluate the research hypotheses empirically, a structured questionnaire was formulated for gathering data from university students. Using a three-step process, we constructed our survey questionnaire based on the existing literature. First, an extensive literature review was employed to identify the questionnaire items partially. Following that, the researchers who have made important contributions to the subject of education administrated the new questions. Minor alterations and revisions were made to enhance the readability and clarity of the selected questions prior to the finalization of the questionnaire. The questionnaire related to entrepreneurship education (EUC, EC, EKN, and ES) partially administrated by the authors of this study and were adapted from existing studies by Sherkat and Chenari (Citation2020), Agarwal et al. (Citation2020), Miralles et al. (Citation2015), and Aznar et al. (Citation2013). The measures for Entrepreneurial Intentions (EI) and Employability (EM) were selected and adapted from studies by Hossain et al. (Citation2020), Ahmed et al. (Citation2017), Miralles et al. (Citation2015), and Saad et al. (Citation2013). The questionnaire contained 20 items in total, eliminating those that were required to determine the demographic profile. In the context of the study, the measures appeared to be applicable. Data normality and multicollinearity were examined, and the results show that our data is ready for analysis. The reliability test was conducted using Cronbach’s Alpha cutoff values of 0.70 (α > 0.70) for each construct, yielding good findings.

Finally, to examine the understandability of the measuring items, a pilot test with a convenient sample of 30 respondents was conducted. After conducting the pilot test, we collected data through an online survey questionnaire. We collect data within three weeks in the month of September 2022. Unless otherwise noted, participants rated each item on a 7-point Likert scale from ‘1’ for ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘7’ for ‘strongly agree’. A higher score on the scale reflected a greater level of the construct being measured.

3.2. Samples and sampling

The participants are mainly university students. The study initially began with a sample size of 413 participants (). Then, during the data screening process, it was discovered that 16 respondents had provided unengaged responses, which means that their answers had a standard deviation of zero.

Table 1. Comparative demographics between the population and sample.

Therefore, their observations were not included in the final analysis to prevent misleading results. Consequently, we were able to keep 397 valid samples for further examination to be enough for using SEM in social science research, per Hair et al. (Citation2010) recommended procedures. This study has been used a convenience sampling method for selecting respondents. Among respondents, 222 are graduate students (55.9%) and 170 are postgraduates (42.8%), while the remaining 1.3% (5) earn their doctorate (). Most of the participants were between the ages of 20 to 24 (51.1%), and over half were female (50.6%).

Table 2. Demographic Information (n = 397).

3.3. Common method variance (CMV)

This study tested CMVs using Harman’s single-factor test. As stated by Podsakoff et al. (Citation2003), if a single factor accounts for more than 50% of the variance or if all items load on the same factor, then it signifies the existence of CMV problems. However, the findings of this study revealed that the initial factor only explained 28% of the total variance, and multiple factors had eigenvalues greater than 1, indicating the absence of any CMV issues (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003).

3.4. Overview of analyses

The research adopted a three-fold methodology to analyze the data. Firstly, the exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) were employed to evaluate the constructs’ reliability, validity, multicollinearity, and common method variance (CMV). Secondly, well-established fit indices were utilized to assess the measurement and structural models’ representativeness of the data. Finally, path analysis was conducted using the structural equation modeling (SEM) program, AMOS (version 24), to test the research hypotheses. SEM was preferred due to its ability to predict exogenous variables in the model, demonstrate the association among constructs and its strong predictive power ().

Table 3. Technical specifications of the study.

4. Analysis and results

4.1. Measurement model Analyses

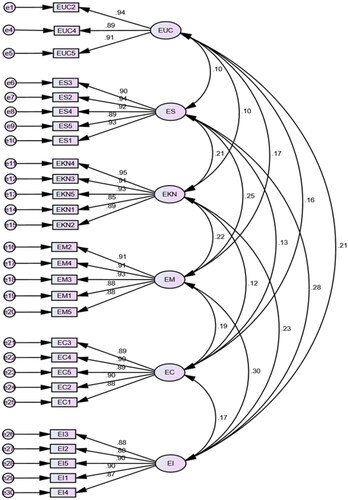

illustrates the measurement model, with its validity and reliability explained in . The findings indicate that both Cronbach’s alpha () and CR scores surpass the recommended cutoff value of 0.70, ranging from 0.935 to 0.963, demonstrating strong internal consistency. The AVE scores, which range from 0.787 to 0.839, also exceed the acceptable threshold of 0.50, and the factor loads range from 0.875 to 0.948 (), all surpassing the recommended cutoff of 0.70. Furthermore, there is both divergent and discriminant validity because the value of the inter-construct correlation is less than the square root of the AVEs, as suggested by Hair et al. (Citation2010) and Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981). The VIF values, ranging from 1.045 to 1.152, demonstrate that the model does not display multicollinearity problems, as stated by Hossain et al. (Citation2023).

Table 4. Validity and reliability.

Table 5. Standardized regression weights.

To evaluate the overall model fit, various commonly utilized fit indices, including chi-square of degrees of freedom (X2/d > 3), CFI (>0.90), GFI (>0.85), AGFI (>0.80) and RMSEA (<0.05), were evaluated, and the model demonstrated good fit according to these criteria (Hair et al., Citation2010; Hu & Bentler, Citation1999).

4.2. Structural model analysis

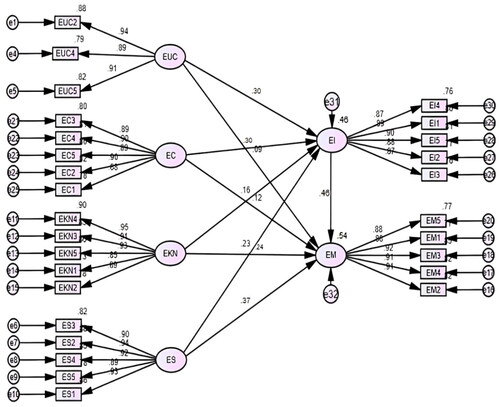

This research utilizes structural model analysis to evaluate the satisfaction of measurement models and examine theoretical connections between entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurial intention, and employability ().

According to the depicted in , the SEM model demonstrates a satisfactory model fit with respect to the data (X2/df. = 1.648, AGFI = 0.887, GFI =.905, CFI = .981, TLI = .979, IFI = .981, RMSEA = 0.040, Pclose = .997). The data indicate that the model explained (e.g. R2 value) 46% and 54% of the variance in entrepreneurial intention and employability, respectively. According to the study, hypotheses H1 and H2 suggest that creating an entrepreneurial environment in universities can have a positive impact on both EI and EM prospects. This study found that a favorable entrepreneurial climate was significantly associated with higher EI (p < 0.001) and increased EM prospects (p = 0.046), supporting H1 and H2. Additionally, this study assessed the impact of EC on both EI and EM (H3 and H4). The data demonstrated that being exposed to EC had a constructive and noticeable influence on EI (p = 0.036) and EM (p = 0.020), supporting the validity of H3 and H4. Furthermore, hypotheses H5 and H6 investigated the effect of EKN on EI and EM. This study found that EKN had a favorable and noteworthy impact on both EI (p < 0.001) and EM prospects (p = 0.005), supporting H5 and H6. Finally, in hypotheses H7 and H8, the influence of ES on EI and employability was investigated. The findings indicated a notable positive effect of ES on both EI (p < 0.001) and prospects for employability (p = 0.006), thus providing confirmation for H7 and H8.

Table 6. Summary of the SEM results.

4.3. Mediation analysis

This study explores the connection between EE, EI, and EM with a focus on the mediating role of entrepreneurial intentions ().

Table 7. Mediating effects.

The study adopts the concept of partial mediation and employs bootstrapping with a sample size of 397 and a 95% confidence interval, repeated 5,000 times, to assess the mediating effects. The results indicate significant mediation effects of EI on the relationship betwixt EE (EUC, EC, EKN, and ES) and EM. All pathways were found to be significant at a probability level of less than 0.001 (Baron & Kenny, Citation1986), supporting Hypothesis H9 and indicating significant partial mediation effects.

5. Discussion

We have developed a structural framework to investigate three main aspects related to entrepreneurship education. Firstly, we aimed to determine whether providing entrepreneurship education to students has an influence on their entrepreneurial intention aligning with the TPB (Ajzen, Citation1991). To measure this, we tested hypotheses H1, H3, H5, and H7. The results supported our indicating hypotheses and were consistent with findings from other studies such as Ashari et al. (Citation2021); Christian et al. (Citation2020); Georgescu and Herman (Citation2020); Ahmed et al. (Citation2017); Singh and Singh (Citation2017); Nowiński et al. (2017); and Jackson (Citation2014). Secondly, our objective was to ascertain if the provision of entrepreneurial education impacts the employability of students. To measure this, we tested hypotheses H2, H4, H6, and H8. The results supported our indicating hypotheses and were consistent with findings from other studies such as Mittal and Raghuvaran (Citation2021); Herrera et al. (Citation2018); Singh and Singh (Citation2017); Jones et al. (Citation2017); Jackson (Citation2014). Lastly, our goal was to determine if there was mediation between entrepreneurial intention and employability. We found that there were gaps in the direct/moderation/mediation effect of diverse contexts on entrepreneurial education, as highlighted in various research studies. Therefore, we wanted to fill this gap by examining the mediating effect of entrepreneurial intention and employability. The results supported our indicating hypothesis H9 that there is a mediating effect between entrepreneurship education and employability. That means entrepreneurial intention can enhance employability. Although there were gaps in previous research, several studies such as Bell (Citation2016); Fulgence (Citation2016); Komulainen et al. (Citation2009) indicate that employability is influenced by entrepreneurial intention.

Additionally, our findings exhibit consistency with the TPB (Ajzen, Citation1991). In this case, creating an entrepreneurial environment, exposure to entrepreneurial curricula, entrepreneurial knowledge, and entrepreneurial skills can influence the intention towards starting one’s own business, ultimately leading to higher entrepreneurial intentions and employability prospects.

5.1. Theoretical contribution

Firstly, the theoretical contribution of this research comes from the fact that it creates a unique framework that connects three important factors: entrepreneurial education, intentions, and employability. Secondly, previous research has looked at the effects of EE on EI and EM separately. We integrated these three variables and evaluated their effects. Thirdly, the research model of this study shows how entrepreneurship education can lead to stronger entrepreneurial intentions, which in turn can lead to better employability outcomes. Additionally, the research demonstrates that entrepreneurial intentions mediate the connection between entrepreneurship education and employability. This is a new and unique concept in the literature of entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurial intention, and employability because, before this study, there were no studies that had shown or analyzed the mediation effect of intention between entrepreneurship education and employability. These findings indicate that entrepreneurship education can indirectly enhance employability outcomes by increasing entrepreneurial intentions. This means that people who want to be entrepreneurs are more likely to be employable and able to do their jobs well and efficiently. This could be because they like to try new things, take risks, and be proactive, all of which are valued in the job market right now. Employers may value these qualities and seek out candidates with high entrepreneurial intentions. Lastly, Variables such as entrepreneurial university climate, knowledge, skills, and curricula are integrated into TPB, enabling us to examine the interplay of these factors and their impact on entrepreneurial outcomes within the university setting. This approach makes a notable theoretical contribution to entrepreneurship research by providing a more comprehensive framework for studying entrepreneurial intentions and their determinants.

6. Conclusion

Entrepreneurship education, as supported by theoretical foundations such as the TPB (Ajzen, Citation1991), provides a unique avenue for individuals to explore and develop their genuine entrepreneurial identity (Byrne et al., Citation2022). This research emphasizes the meaning of teaching entrepreneurship in universities in shaping the entrepreneurial aspirations of students in Bangladesh. It demonstrates the many beneficial outcomes associated with entrepreneurial education, such as fostering a favorable attitude towards entrepreneurship, raising the probability of students opting for entrepreneurship as a career, and enhancing their employability prospects. All signs point to the necessity of entrepreneurship education in addressing Bangladesh’s high unemployment rate. Based on these findings, universities and decision-makers in Bangladesh should prioritize adding entrepreneurship education to their academic programs to better equip students for the competitive job market.

6.1. Practical implications

Policymakers, educators, and academics in Bangladesh can greatly benefit from the study’s findings, particularly with regard to entrepreneurship education. The results show that EUC, EC, EKN, and ES had a favorable impact on both EI and EM; this study also showed that EI can promote EM. This exemplifies the significance of EE in equipping university students with the knowledge, confidence, and drive to become successful business owners and increase their employability. To leverage these findings effectively, it is advisable for institutions in Bangladesh to incorporate entrepreneurship courses into their curriculum, aiming to nurture students’ entrepreneurial aspirations and enhance their employability. For example, universities can create an entrepreneurial environment and offer dedicated courses that empower students to actively participate in entrepreneurial endeavors, thereby increasing their prospects of establishing successful businesses. Such initiatives would foster the development of crucial skills and mindsets, consequently improving employability across various career trajectories. By providing students with essential knowledge, practical training, and valuable networking opportunities, universities can effectively cultivate an entrepreneurial mindset among their students and equip them to thrive in today’s competitive job market. Furthermore, this study found a positive association between EI and EM. This implies that universities in Bangladesh should push their students towards choosing entrepreneurship as a career path due to the benefits it can bring in terms of employment and professional advancement. Mentorship programs, internships, and other entrepreneurship experiences can be integrated into the curriculum to provide practical exposure and guidance to students in their entrepreneurial endeavors.

6.2. Limitations

Even though this study made significant contributions, it still has some limitations, which pave the way for further research. Firstly, a survey-based study has the inherent constraint that respondents might not always express themselves exactly as they intend. Secondly, the sample size used may not be big enough to accurately represent the entire population of university students in Bangladesh, which could lead to limitations in generalizing the consequences for the larger population. Thirdly, results may be limited to the cultural context of Bangladeshi higher education and may not generalize to other nations. Forthly, the study is limited in that it is only a cross-sectional analysis, which implies that it solely investigates the connection between the variables at a specific instant. As a result, it becomes challenging to establish cause-and-effect relationships and gain insights into how the connection between the variables evolves over time. Lastly,

6.3. Future research

A suggestion is to carry out additional investigations into how entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurial intentions, and employability are interrelated in various countries, considering their distinctive cultural and economic attributes. Conducting a longitudinal study would offer a more profound comprehension of causation and how things develop over time. In addition, it is important to factor in other control variables such as gender, socio-economic background, and previous business experience. Entrepreneurship education can be used as a second-order construct. The present investigation centered on a particular group of university students; thus, it is recommended that forthcoming studies make an effort to incorporate a broader range of participants to achieve a more holistic grasp of the topic.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization, Md. Abu Issa Gazi, Abdullah Al Masud, and Md. Kazi Hafizur Rahman; Data curation, Mohd Faizal Yusof, Abdul Rahman bin S Senathirajah and Md. Kazi Hafizur Rahman; Formal analysis, Md. Kazi Hafizur Rahman and Abdullah Al Masud; Funding acquisition, Mohd Faizal Yusof and Abdul Rahman bin S Senathirajah; Investigation, Mohd Faizal Yusof, Abdul Rahman bin S Senathirajah and Md. Alamgir Hossain; Methodology, Md. Abu Issa Gazi and Abdullah Al Masud; Project administration, Md. Abu Issa Gazi; Resources, Mohd Faizal Yusof, Abdul Rahman bin S Senathirajah, Md. Aminul Islam and Md. Kazi Hafizur Rahman; Supervision, Md. Aminul Islam; Validation, Mohd Faizal Yusof and Md. Alamgir Hossain; Writing – original draft, Md. Kazi Hafizur Rahman and Abdullah Al Masud; Writing – review & editing, Md. Abu Issa Gazi, Abdullah Al Masud, Md. Aminul Islam, Abdul Rahman bin S Senathirajah and Md. Alamgir Hossain

Public Interest Statement.docx

Download MS Word (19.2 KB)Author Biography_.docx

Download MS Word (16.1 KB)Disclosure statement

Authors declare that there is no potential conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

The corresponding author will provide the data upon request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Md. Abu Issa Gazi

Dr. Md. Abu Issa Gazi is a Research Fellow at INTI international University and an Associate Professor of Management at School of Management, Jiujiang University, China (JJU-CN). In addition, Dr. Gazi is the Post-doctorate Awardee from Universiti of Malaysia Perlis, Malaysia. Prior to that, he worked as an Assistant Professor, Senior Lecturer and Lecturer at Department of Business Administration in different Universities in Bangladesh. He has also successfully performed various administrative responsibilities. He received his PhD, MBA and BBA with outstanding performance in Management. Dr. Gazi is a confident in face of challenges diligent postgraduate faculty and having a strong critical thinking ability as an exceptionally talented researcher with greater insights, more perspectives and stronger research skills. He has great passion in teaching and research in the field of Business and Management. His research focuses on industrial workers’ job satisfaction and job stress, international trade, Human Resources Management, Supply Chain Management, Entrepreneurship, e-commerce and broadly on the field of Business, Economics and Management.

Md. Kazi Hafizur Rahman

Md. Kazi Hafizur Rahman is a dedicated MBA student majoring in Human Resource Management at the Department of Management Studies, University of Barishal. With a stellar academic record in completing his BBA, he has emerged as an aspiring academician and prominent researcher. His passion for research is evident in his keen interest in areas such as HRM, management, leadership, entrepreneurship, career development and tourism. Mr. Rahman possesses advanced knowledge of statistical tools like SPSS, AMOS, and Smart PLS, showcasing his proficiency in data analysis. As an emerging researcher, he is actively engaged in various research activities. The research presented by Mr. Rahman not only reflects his individual commitment but also connects to broader projects and issues in the academic landscape, demonstrating his potential impact on the scholarly community.

Mohd Faizal Yusof

Mohd Faizal Yusof is a Lecturer-Associate Applied Researcher at the Faculty of Resilience of the Rabdan Academy Abu Dhabi of United Arab Emirates. He is an experienced blockchain researcher, university technology transfer officer, professional software developer, and former start-up entrepreneur. He has moved up the levels in several software technology companies from software engineer to chief technology officer of a university technology transfer company. He has published a good number of journal articles indexing in Scopus and WOS. His research area includes Blockchain, information security management, marketing, and internet governance.

Abdullah Al Masud

Dr. Abdullah Al Masud, Associate Professor, Department of Management Studies and Dean Faculty of Business Studies, University of Barishal. He has established a significant presence in the academic world, with his research making appearances in reputable journals covering a range of fields, including engineering and social sciences. Some noteworthy publications include the Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, Sustainability-MDPI (indexed in SSCI, WOS, and SCOPUS), Social Sciences & Humanities Open (SSHO) on Elsevier and ScienceDirect (indexed in SCOPUS), Environmental Research Communications and others. Furthermore, Dr. Abdullah Al Masud is an ardent proponent of innovation through the application of Social Science Information Technologies as the primary instrument for competitive advantage and entrepreneurial competitive advantage. His research interests are wide-ranging and encompass management, leadership, human resource management (HRM), Green HRM (GHRM), technology, tourism, sustainability, and various other areas. His expertise and contributions have earned recognition and respect within both academic and practical circles.

Md. Aminul Islam

Dr. Md. Aminul Islam is a Professor in Finance at the Department of Business in the Faculty of Business and Communication of Universiti Malaysia Perlis. He received his bachelor’s degree from the International Islamic University Malaysia; MBA and Doctor of Philosophy from Universiti Sains Malaysia. He also completed an advanced diploma in teaching in higher education from the Nottingham Trent University. He has authored and co-authored about 170 journal papers and 64 conference papers. He has also authored and co-authored five books and three book chapters. He is a certified trainer of Human Resource Development Corporation of Malaysia. He is a member of Asian Academy of Management, Malaysian Institute of Management, and an associate member of Malaysian Finance Association. He is a visiting Professor of Ubudiyyah University Indonesia, Daffodil International University and East Delta University. His research areas of interest include FinTech, Blockchain, Econometrics, Islamic Banking, Sukuk, and Management.

Abdul Rahman bin S. Senathirajah

Abdul Rahman bin S Senathirajah is currently working Associate Professor at Faculty of Business and Communications at INTI International University. Chief Editor of Asian Journal of Management, Engineering and Technology (AJMET). Published a number of papers in ISI, Scopus and international refereed journals in quality management. MQA, Malaysian Quality Assurance Panel Chairman/Member (2009- Current). Served as the Senior Manager - for Quality Assurance and Regulatory. Liaised with MQA and MOHE and various regulatory bodies. Working knowledge of SETARA and MyQuest. Lead Auditor CQI & IRCA Certified ISO 9001:2015. Expert in University KPI design based on Balanced Scorecard. Expertise in Quality Management System Development for Industry and Universities.

Md. Alamgir Hossain

Md. Alamgir Hossain is a Professor of Management at Hajee Mohammad Danesh Science and Technology University, Bangladesh. He obtained his PhD in Economics from the Department of International Trade at Jeonbuk National University, Korea. His research interests lie in the areas of technology acceptance model, human-computer interaction, online consumer behavior, new digital social media and marketing, e-commerce, structural equation modeling, multivariate data analysis, data mining and big data analysis. He has published articles in Computational Economics, Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration, International Journal of Emerging Markets, SAGE Open, Social Science and Humanities Open, FIIB Business Review, PSU Research Review, Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, International Journal of e-Collaboration, International Journal of Information and Learning Technology and so on.

References

- Adu, I. N., Boakye, K. O., Suleman, A. R., & Bingab, B. B. B. (2020). Exploring the factors that mediate the relationship between entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial intentions among undergraduate students in Ghana. Asia Pacific Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 14(2), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJIE-07-2019-0052

- Agarwal, S., Ramadani, V., Gerguri-Rashiti, S., Agrawal, V., & Dixit, J. K. (2020). Inclusivity of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial attitude among young community: Evidence from India. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 14(2), 299–319. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEC-03-2020-0024

- Ahmad, S. Z., Bakar, A. R. A., & Ahmad, N. (2018). An evaluation of teaching methods of entrepreneurship in hospitality and tourism programs. The International Journal of Management Education, 16(1), 14–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2017.11.002

- Ahmed, T., Chandran, V., & Klobas, J. (2017). Specialized entrepreneurship education: Does it really matter? Fresh evidence from Pakistan. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 23(1), 4–19. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-01-2016-0005

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-t

- Ajzen, I. (2005). Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32(4), 665–683. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb00236.x

- Al‐Mamary, Y. H., & Alraja, M. M. (2022). Understanding entrepreneurship intention and behavior in the light of TPB model from the digital entrepreneurship perspective. International Journal of Information Management Data Insights, 2(2), 100106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jjimei.2022.100106

- Amorós, J. E., Cristi, O., & Naudé, W. (2021). Entrepreneurship and subjective well-being: Does the motivation to start-up a firm matter? Journal of Business Research, 127, 389–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.11.044

- Ashari, H., Abbas, I., Abdul-Talib, A., & Zamani, S. N. M. (2021). Entrepreneurship and sustainable development goals: A multigroup analysis of the moderating effects of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intention. Sustainability, 14(1), 431. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010431

- Aznar, F. J., Córdoba, A., Fernández, M., Raduán, M. Á., Balbuena, J. A., Blanco, C. M., & Raga, J. A. (2013). How students perceive the university’s mission in a Spanish university: Liberal versus entrepreneurial education? Cultura y Educación, 25(1), 17–33. https://doi.org/10.1174/113564013806309055

- Barba-Sánchez, V., Salinero, Y., Jiménez Estévez, P., & Ruiz-Palomino, P. (2023). How entrepreneurship drives life satisfaction among people with intellectual disabilities (PwID): A mixed-method approach. Management Decision, https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-11-2022-1568

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

- Barral, M. R. M., Ribeiro, F. G., & Canever, M. D. (2018). Influence of the university environment in the entrepreneurial intention in public and private universities. RAUSP Management Journal, 53(1), 122–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rauspm.2017.12.009

- Barrios, G. R., Rodriguez, J. J., Plaza, A. G., Zapata, C. E., & Zuluaga, M. C. (2021). Entrepreneurial intentions of university students in Colombia: Exploration based on the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Education for Business, 97(3), 176–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2021.1918615

- Bazan, C. (2022). Effect of the university’s environment and support system on subjective social norms as precursor of the entrepreneurial intention of students. SAGE Open, 12(4), 215824402211291. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440221129105

- Bell, R. (2016). Unpacking the link between entrepreneurialism and employability. Education + Training, 58(1), 2–17. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-09-2014-0115

- Bergmann, H., Geissler, M., Hundt, C., & Grave, B. (2018). The climate for entrepreneurship at higher education institutions. Research Policy, 47(4), 700–716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2018.01.018

- Bouncken, R. B., Lapidus, A., & Qui, Y. (2022). Organizational sustainability identity: ‘New Work’ of home offices and coworking spaces as facilitators. Sustainable Technology and Entrepreneurship, 1(2), 100011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stae.2022.100011

- Bozward, D., Rogers-Draycott, M. C., Smith, K. M., Mave, M., Curtis, V., Aluthgama-Baduge, C., Moon, R., & Adams, N. G. (2022). Exploring the outcomes of enterprise and entrepreneurship education in UK HEIs: An Excellence Framework perspective. Industry and Higher Education, 37(3), 345–358. https://doi.org/10.1177/09504222221121298

- Bureau. (2023). B. Bangladesh Education Statistics 2022. https://banbeis.portal.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/banbeis.portal.gov.bd/page/6d10c6e9_d26c_4b9b_9c7f_770f9c68df7c/Bangladesh%20Education%20Statistics%202022%20%281%29_compressed.pdf

- Byrne, J., Shantz, A., & Bullough, A. (2022). What about Us? Fostering Authenticity in Entrepreneurship Education. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 22(1), 4–31. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2020.0512

- Charney, A., & Libecap, G. D. (2000). The economic contributional entrepreneurship education: An evaluation with an established program. Advances in the Study of Entrepreneurship, Innovation, and Economic Growth, 12, 1–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1048-4736(00)12002-8

- Christian, U. C., Ifeoma, N., Ikechukwu, A., & Ukpere, W. I. (2020). A relationship between sustainable entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions among students: A developing country’s perspective. Psychology and Education Journal, 57(7), 516–524.

- Coetzee, M., Oosthuizen, R. M., & Stoltz, E. (2016). Psychosocial employability attributes as predictors of staff satisfaction with retention factors. South African Journal of Psychology, 46(2), 232–243. https://doi.org/10.1177/0081246315595971

- Costa, S. F., Santos, S. C., Wach, D., & Caetano, A. (2017). Recognizing opportunities across campus: The effects of cognitive training and entrepreneurial passion on the business opportunity prototype. Journal of Small Business Management, 56(1), 51–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12348

- Cui, J., Sun, J., & Bell, R. (2021). The impact of entrepreneurship education on the entrepreneurial mindset of college students in China: The mediating role of inspiration and the role of educational attributes. The International Journal of Management Education, 19(1), 100296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2019.04.001

- Entrepreneurship 2020 Action Plan. (2018). European Economic and Social Committee. Retrieved October 13, 2022, from https://www.eesc.europa.eu/en/our-work/opinions-information-reports/opinions/entrepreneurship-2020-action-plan

- Entrialgo, M., & Iglesias, V. (2016). The moderating role of entrepreneurship education on the antecedents of entrepreneurial intention. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 12(4), 1209–1232. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-016-0389-4

- Fayolle, A., Gailly, B., & Lassas-Clerc, N. (2006). Assessing the impact of entrepreneurship education programmes: A new methodology. Journal of European Industrial Training, 30(9), 701–720. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090590610715022

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention and behaviour: An introduction to theory and research. Addison-Wesley.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 382–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800313

- Foss, N. J., & Klein, P. G. (2020). Entrepreneurial opportunities: Who needs them? Academy of Management Perspectives, 34(3), 366–377. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2017.0181

- Fulgence, K. (2016). University of Siegen. Employability of higher education institutions graduates : Exploring the influence of entrepreneurship education and employability skills development program activities in Tanzania. Dissertation

- Gazi, M. A. I., Masud, A. A., Sobhani, F. A., Dhar, B. K., Hossain, M. S., & Hossain, A. I. (2023). An empirical study on emergency of distant tertiary education in the Southern Region of Bangladesh during COVID-19: Policy implication. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(5), 4372. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054372

- Gazi, M. A I., Nahiduzzaman, M., Harymawan, I., Masud, A. A., & Dhar, B. K. (2022). Impact of COVID-19 on financial performance and profitability of banking sector in special reference to private commercial banks: Empirical evidence from Bangladesh. Sustainability, 14(10), 6260. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14106260

- George, G., & Bock, A. J. (2011). The business model in practice and its implications for entrepreneurship research. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 35(1), 83–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00424.x

- Georgescu, M., & Herman, E. (2020). The impact of the family background on students’ entrepreneurial intentions: An empirical analysis. Sustainability, 12(11), 4775. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114775

- Gupta, R. K. (2022). Does university entrepreneurial ecosystem and entrepreneurship education affect the students’ entrepreneurial intention/startup intention? Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering, 355–365. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-0561-2_32

- Hair, J., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective. Pearson Education, Cop.

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2012). (Theory). Partial least squares: The better approach to structural equation modeling? Long Range Planning, 45(5-6), 312–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2012.09.011

- Herrera, F. A., Guerrero, M., & Urbano, D. (2018). Entrepreneurship and Innovation Ecosystem’s Drivers: The role of higher education organizations (pp. 109–112). Springer International Publishing EBooks. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-71014-3_6

- Heuer, A., & Kolvereid, L. (2014). Education in entrepreneurship and the theory of planned behaviour. European Journal of Training and Development, 38(6), 506–523. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJTD-02-2013-0019

- Hodzic, S., Ripoll, P., Lira, E. M., & Zenasni, F. (2015). Can intervention in emotional competences increase employability prospects of unemployed adults? Journal of Vocational Behavior, 88, 28–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2015.02.007

- Hossain, M. M., Alam, M., Alamgir, M., & Salat, A. (2020). Factors affecting business graduates’ employability–empirical evidence using partial least squares (PLS). Education + Training, 62(3), 292–310. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-12-2018-0258

- Hossain, M. D. S., Hossain, M. D. A., Al Masud, A., Islam, K. M. Z., Mostafa, M. D. G., & Hossain, M. T. (2023). The integrated power of gastronomic experience quality and accommodation experience to build tourists’ satisfaction, revisit intention, and word-of-mouth intention. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/1528008X.2023.2173710

- Hossain, M. M., Zahidul Islam, K. M., Masud, A. A., Biswas, S., & Hossain, M. A. (2021). Behavioral intention and continued adoption of Facebook: An exploratory study of graduate students in Bangladesh during the Covid-19 pandemic. Management, 25(2), 153–186. https://doi.org/10.2478/manment-2019-0078

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Ibrahim, A. B., & Soufani, K. (2002). Entrepreneurship education and training in Canada: A critical assessment. Education + Training, 44(8/9), 421–430. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400910210449268

- Iwu, C. G., Opute, P., Nchu, R. M., Eresia-Eke, C. E., Tengeh, R. K., Jaiyeoba, O., & Aliyu, O. A. (2021). Entrepreneurship education, curriculum and lecturer-competency as antecedents of student entrepreneurial intention. The International Journal of Management Education, 19(1), 100295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2019.03.007

- Izedonmi, P. F. (2010). The effect of entrepreneurship education on students’ entrepreneurial intentions. Global Journal of Management and Business Research, 10(6).

- Jackson, D. (2014). Employability skill development in work-integrated learning: Barriers and best practice. Studies in Higher Education, 40(2), 350–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2013.842221

- Jones, P., Pickernell, D., Fisher, R. J., & Netana, C. (2017). A tale of two universities: Graduates perceived value of entrepreneurship education. Journal of Education + Training, 59(7/8), 689–705. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-06-2017-0079

- Karimi, S., Biemans, H. J., Lans, T., Chizari, M., & Mulder, M. (2016). The impact of entrepreneurship education: A study of Iranian students’ entrepreneurial intentions and opportunity identification. Journal of Small Business Management, 54(1), 187–209. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12137

- Karyaningsih, R. P. D., Wibowo, A., Saptono, A., & Narmaditya, B. S. (2020). Does entrepreneurial knowledge influence vocational students’ intention? Lessons from Indonesia. Entrepreneurial Business and Economics Review, 8(4), 138–155. https://doi.org/10.15678/EBER.2020.080408

- Killingberg, N. M., Kubberød, E., & Blenker, P. (2020). Preparing for a future career through entrepreneurship education: Towards a research agenda. Industry and Higher Education, 35(6), 713–724. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950422220969635

- Komulainen, K., Korhonen, M., & Räty, H. (2009). Risk‐taking abilities for everyone? Finnish entrepreneurship education and the enterprising selves imagined by pupils. Gender and Education, 21(6), 631–649. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540250802680032

- Kostakis, I., & Tsagarakis, K. P. (2022). The role of entrepreneurship, innovation and socioeconomic development on circularity rate: Empirical evidence from selected European countries. Journal of Cleaner Production, 348, 131267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.131267

- Krueger, N. F., & Carsrud, A. L. (1993). Entrepreneurial intentions: Applying the theory of planned behaviour. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 5(4), 315–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985629300000020

- Lim, W. M., Lee, Y. C., & Mamun, A. A. (2021). Delineating competency and opportunity recognition in the entrepreneurial intention analysis framework. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 15(1), 212–232. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEEE-02-2021-0080

- Loi, M., Castriotta, M., & Di Guardo, M. C. (2016). The theoretical foundations of entrepreneurship education: How co-citations are shaping the field. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 34(7), 948–971. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242615602322

- Mahmood, T. M. A. T., Mamun, A. A., & Ibrahim, M. D. (2020). Attitude towards entrepreneurship: A study among Asnaf Millennials in Malaysia. Asia Pacific Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 14(1), 2–14. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJIE-06-2019-0044

- Malik, A., Onyema, E. M., Dalal, S., Kumar, U., Anand, D., Sharma, A., & Simaiya, S. (2023). Forecasting students’ adaptability in online entrepreneurship education using modified ensemble machine learning model. Array, 19, 100303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.array.2023.100303

- Martínez-Cañas, R., Ruiz‐Palomino, P., Jiménez-Moreno, J., & Linuesa-Langreo, J. (2023). Push versus Pull motivations in entrepreneurial intention: The mediating effect of perceived risk and opportunity recognition. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 29(2), 100214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iedeen.2023.100214

- Masud, A. A., Hossain, M. A., Roy, D. B., Hossain, M. S., Nabi, M. N., Ferdous, A., & Hossain, M. T. (2021). Global pandemic situation, responses and measures in Bangladesh: New normal and sustainability perspective. International Journal of Asian Social Science, 11(7), 314–332. https://doi.org/10.18488/journal.1.2021.117.314.332

- Mezhoudi, N., Alghamdi, R., Aljunaid, R., Krichna, G., & Düştegör, D. (2023). Employability prediction: A survey of current approaches, research challenges and applications. Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized Computing, 14(3), 1489–1505. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12652-021-03276-9

- Miralles, F., Giones, F., & Riverola, C. (2015). Evaluating the impact of prior experience in entrepreneurial intention. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 12(3), 791–813. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-015-0365-4

- Mittal, P., & Raghuvaran, S. (2021). Entrepreneurship education and employability skills: The mediating role of e-learning courses. Entrepreneurship Education, 4(2), 153–167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41959-021-00048-6

- Molina-Ramírez, E., & Barba‐Sánchez, V. (2021). Embeddedness as a differentiating element of indigenous entrepreneurship: Insights from Mexico. Sustainability, 13(4), 2117. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042117

- Nabi, G., Liñán, F., Fayolle, A., Krueger, N. F., & Walmsley, A. (2017). The impact of entrepreneurship education in higher education: A systematic review and research Agenda. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 16(2), 277–299. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2015.0026

- Nhleko, Y., & Westhuizen, T. (2022). The role of higher education institutions in introducing entrepreneurship education to meet the demands of Industry 4.0. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 28, 1–23.

- Nordin, M. N., Abet, M., Maying, D., Moi, T. H., & Abbas, M. S. (2023). Blind special education students learning: Preparing future teachers psychology. Journal for Reattach Therapy and Developmental Diversities, 6(3s), 21–30. Retrieved from https://www.jrtdd.com/index.php/journal/article/view/317

- Oftedal, E. M., Iakovleva, T., & Foss, L. (2017). University context matter. Education + Training, 60(7/8), 873–890. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-06-2016-0098

- Pardo-Garcia, C., & Barac, M. (2020). Promoting employability in higher education: A case study on boosting entrepreneurship skills. Sustainability, 12(10), 4004. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104004

- Passaro, R., Quinto, I., & Thomas, A. (2018). The impact of higher education on entrepreneurial intention and human capital. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 19(1), 135–156. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-04-2017-0056

- Paul, J., & Shrivastava, A. (2015). Comparing entrepreneurial communities. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 9(3), 206–220. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEC-06-2013-0018

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Porfírio, J., Felício, J. A., Carrilho, T., & Jardim, J. (2023). Promoting entrepreneurial intentions from adolescence: The influence of entrepreneurial culture and education. Journal of Business Research, 156, 113521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.113521

- Rae, D. (2007). Connecting enterprise and graduate employability. Education + Training, 49(8/9), 605–619. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400910710834049

- Rahman, M. M. (2023). Impact of taxes on the 2030 agenda for sustainable development: Evidence from organization for economic co-operation and development (OECD) countries. Regional Sustainability, 4(3), 235–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsus.2023.07.001

- Rahman, M. M., Hasan, J., Deb, B. C., Rahman, M. S., & Kabir, A. (2023). The effect of social media entrepreneurship on sustainable development: Evidence from online clothing shops in Bangladesh. Heliyon, 9(9), e19397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e19397

- Rahman, M. M., Salamzadeh, A., & Tabash, M. I. (2022). Antecedents of entrepreneurial intentions of female undergraduate students in Bangladesh: A covariance-based structural equation modeling approach. JWEE, (1-2), 137–153. https://doi.org/10.28934/jwee22.12.pp137-153

- Ramadani, V., Rahman, M. M., Salamzadeh, A., Rahaman, S., & Abazi-Alili, H. (2022). Entrepreneurship education and graduates’ entrepreneurial intentions: Does gender matter? A multi-group analysis using AMOS. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 180, 121693. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2022.121693

- Ruiz‐Palomino, P., & Martínez-Cañas, R. (2021). From opportunity recognition to the start-up phase: The moderating role of family and friends-based entrepreneurial social networks. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 17(3), 1159–1182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-020-00734-2

- Saad, M., Shamsuri, M., Robani, A., Jano, Z., & Majid, I. (2013). Employers’ perception on engineering, information and communication technology (ICT) students’ employability skills. Global Journal of Engineering Education, 15, 42–47.

- Salamzadeh, Y., Sangosanya, T. A., Salamzadeh, A., & Braga, V. (2022). Entrepreneurial universities and social capital: The moderating role of entrepreneurial intention in the Malaysian context. The International Journal of Management Education, 20(1), 100609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2022.100609

- Sancho, M. P. S., Ramos-Rodríguez, A. R., & Vega, M. L. R. (2021). Is a favorable entrepreneurial climate enough to become an entrepreneurial university? An international study with GUESSS data. The International Journal of Management Education, 19(3), 100536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2021.100536

- Scott, F. J., Connell, P., Thomson, L. A., & Willison, D. (2017). Empowering students by enhancing their employability skills. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 43(5), 692–707. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2017.1394989

- Shapero, A., & Sokol, L. (1982). The social dimensions of entrepreneurship. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign’s academy for entrepreneurial leadership historical research reference in entrepreneurship.

- Sherkat, A., & Chenari, A. (2020). Assessing the effectiveness of entrepreneurship education in the universities of Tehran province based on an entrepreneurial intention model. Studies in Higher Education, 47(1), 97–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1732906

- Singh, A., & Singh, L. B. (2017). E-learning for employability skills: Students perspective. Procedia Computer Science, 122, 400–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2017.11.386

- Tentama, F., & Yusantri, S. D. (2020). The role of entrepreneurial intention in predicting vocational high school students’ employability. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education (IJERE), 9(3), 558. https://doi.org/10.11591/ijere.v9i3.20580

- Uddin, M., Chowdhury, R. A., Hoque, N., Ahmad, A., Mamun, A., & Uddin, M. N. (2022). Developing entrepreneurial intentions among business graduates of higher educational institutions through entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial passion: A moderated mediation model. The International Journal of Management Education, 20(2), 100647. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2022.100647

- Van Harten, J., De Cuyper, N., Knies, E., & Forrier, A. (2021). Taking the temperature of employability research: A systematic review of interrelationships across and within conceptual strands. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 31(1), 145–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2021.1942847

- Van Holm, E. J. (2021). Making entrepreneurs? Makerspaces and entrepreneurial intent among high school students. The Journal of Entrepreneurship, 30(2), 249–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/09713557211025652

- Volery, T., Müller, S., Oser, F., Naepflin, C., & del Rey, N. (2013). The impact of entrepreneurship education on human capital at upper-secondary level. Journal of Small Business Management, 51(3), 429–446. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12020

- Vuorio, A., Zichella, G., & Sawyerr, O. (2022). The impact of contingencies on entrepreneurship education outcomes. Entrepreneurship Education and Pedagogy, 6(2), 299–330. https://doi.org/10.1177/25151274221104702

- Wang, C., Mundorf, N., & Salzarulo-McGuigan, A. (2021). Entrepreneurship education enhances entrepreneurial creativity: The mediating role of entrepreneurial inspiration. The International Journal of Management Education, 20(2), 100570. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2021.100570