Abstract

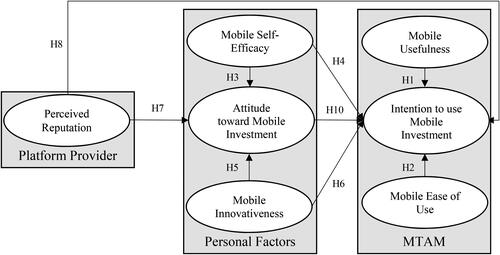

Mobile investment has been introduced with technological advancements and the enhancement of mobile device functions. However, relatively limited studies have been particularly focused on the determinants of adoption intention on mobile investment. Therefore, this study aimed at exploring the factors affecting investment intention (INT) to use mobile investment by considering the influence of personal factors (mobile self-efficacy [MSE], mobile innovativeness [MI], and attitudes [ATT]), and perceived reputation (PR) through an extended mobile technology acceptance model (MTAM). Purposive sampling was utilised to obtain 213 completed responses, which were then analysed using the partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM), and the importance-performance map analysis (IPMA). The results showed that mobile usefulness (MU), MI, PR, and ATT substantially affect INT usage, while MSE had no significant effect on INT usage. Additionally, both MSE and PR significantly influenced ATT, but MI had an insignificant influence on ATT. This study disclosed the missing information by identifying the critical factors of mobile investment adoption using a novel framework developed from the perspective of personal factors and platform providers’ PR. Furthermore, the study provided some significant practical implications, as the findings could be referred to by the stakeholders in formulating policies and strategies to stimulate consumers to adopt mobile investment as their investment platform.

reviewing editor:

Introduction

The advancement of technology and sophistication of mobile devices have resulted in the transformation of traditional business activities. For example, with technological innovation, more business activities have been shifted from offline to online modes, such as online shopping, internet banking, online investment, and the like. With the innovation of mobile devices, the mobile function has been extended from communications to become business purposes. Therefore, several business activities have been changed to mobile-based, such as mobile banking, mobile payment, mobile shopping, and others. Rapid development in mobile technology has led to an increase in mobile internet users (Chong et al., Citation2021). Technology innovation and evolution in financial services also disrupted conventional financial activities, changing the structure of financial institutions and consumers’ financial behaviour (Fan, Citation2022). These innovations and evolutions also increased the consumers’ accessibility to several business activities, including investment management (Chong et al., Citation2021). Therefore, mobile investment has been introduced, whereas investment management activities have been performed by utilising the functions of mobile devices.

Mobile investment or mobile investing is called investment transactions and investment information searching through robot advisors using mobile devices, such as smartphones or tablets (Fan, Citation2022). Investors can make the investment transaction instantaneously, and manage their investment portfolios anywhere just by using their mobile devices (Chong et al., Citation2021). Mobile investment also offers various financial services, and investment information can be accessed by using mobile devices at a lower cost (Hikida & Perry, Citation2020). Advancements in mobile technology would make investment activities faster, and increase flexibility and transparency (Chong et al., Citation2021). Additionally, mobile investment allowed investors to monitor their investment portfolios easily, as several functions could be done using mobile devices, such as placing orders, conducting an analysis of the company’s fundamental information, checking for stock performance, and performing technical analysis (Chong et al., Citation2021). Therefore, investors could easily manage their investment portfolio, and respond to the market instantaneously using mobile investment. Mobile investment platform also allows investors to stay connected with the market in real-time, especially for active traders, to make informed decisions. This will enable investors to make timely decisions and take advantage of opportunities.

In Malaysia, several mobile investment platforms have been introduced, such as GO+, introduced by Touch n Go; Raiz, a collaboration between Permodalan Nasional Berhad (PNB) and Raiz Invest Limited (Australia); StashAway, established by StashAway Malaysia Sdn Bhd; MYTHEO, operated by GAX MD Sdn Bhd; and other platforms that are introduced by the investment banks or fund management companies. Although several advantages are associated with mobile investment, the usage of mobile investment applications, such as mobile trading or online trading participation in Malaysia is still at a lower level. Chong et al. (Citation2021) mentioned that nearly 77% of Malaysians used the internet, and 89% used smartphones to surf the internet. However, the statistics of Bursa Malaysia further showed that the Malaysian online trading participation rate was approximately 43% in 2020. This has raised doubts, as mobile investment adoption was at a lower level, despite the fact that it provided numerous advantages, and the percentage of access to the internet using smartphones was relatively high.

Although many studies have examined the adoption of mobile technology, such as mobile payment (Al-Saedi et al., Citation2020; Handarkho & Harjoseputro, Citation2020; Yan et al., Citation2021), mobile tourism (Wan et al., Citation2022), mobile shopping (Ng et al., Citation2022), mobile banking (Ho et al., Citation2020; Purohit & Arora, Citation2023; Singh & Srivastava, Citation2020), and others, there is still a gap in the literature on mobile investment adoption, whereas the empirical evidence on this area is still scarce. To date, only a few studies related to mobile technology application in investment were found, such as stock trading application adoption (Chong et al., Citation2021), investment intention (INT) in online peer-to-peer lending (Lin & Huang, Citation2021), mobile financial service (Yan et al., Citation2023), and mobile investment technology adoption (Fan, Citation2022; Nair et al., Citation2023). Additionally, evidence is deficient on impact of the platform provider’s perceived reputation (PR) on mobile investment adoption. To close the gap, this study examines the underlying factors that predict mobile investment adoption by focusing on the investors’ personal factors and platform providers’ PR to offer a new shred regarding INT to use mobile investment. Therefore, the study objective is to identify the factors that significantly influence INT to adopt mobile investment amongst Malaysian investors by considering the investors’ personal factors and platform provider’s PR.

To better examine mobile investment adoption, the mobile technology acceptance model (MTAM) has been used as the foundation model for this study. Literature showed that most of the previous studies used the technology acceptance model (TAM) (Bailey et al., Citation2020; Purohit & Arora, Citation2023; Sarmah et al., Citation2021), unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT) or UTAUT2 (Al-Saedi et al., Citation2020; Dhiman et al., Citation2020), and the theory of planned behaviour (TPB) model, or integrated these models (Ariffin et al., Citation2021; Chong et al., Citation2021; Flavian et al., Citation2020; Ho et al., Citation2020), as their framework to study the factors of mobile technology adoption. However, these models are not explicitly designed for mobile technology adoption. Therefore, MTAM was chosen for this study, as the model was introduced mainly for mobile technology adoption. Moreover, three additional variables that reflect the personal factors, namely mobile self-efficacy (MSE), mobile innovativeness (MI), and attitudes (ATT) were included as exogenous variables to predict INT to use mobile investment. In the initial MTAM model, only two predictors were suggested (mobile usefulness [MU] and mobile ease of use [MEOU]), and it was required to include other related predictors to provide better insight into mobile technology adoption (Lew et al., Citation2021). Additionally, the platform provider’s PR was also included in the model due to its significant role in nurturing mobile investment usage.

The study’s findings are crucial, as they could contribute to the literature on behavioural finance and mobile technology adoption. This is because the study identifies the factors that determine investors’ adoption of mobile investment platform in managing their investment. This finding could fill the research gaps in this area, as there were deficient studies on mobile investment adoption in literature from the perspective of the personal factors and platform provider’s PR. Additionally, the study’s findings are important for stakeholders, such as the government authorities and businesses, especially for the securities commission, investment management companies, and securities firms. This enables them to leverage their limited resources to attract more investors to use mobile investment platforms, in correspondence to the national digital economy agenda. Moreover, this study discovers the PR effect of the mobile investment platform providers. The platform providers should increase their adoption by enhancing their reputation, which significantly affect the investors’ ATT and INT to adopt mobile investment.

Literature review

Mobile technology acceptance model (MTAM)

The MTAM was introduced by Ooi and Tan (Citation2016) to predict INT of an individual to adopt mobile technology. This model was proposed due to the limitations in several prominent models in literature that were used to explain the adoption of new technology. For example, the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) was introduced to describe an individual’s usage of electronic email in an organisational context. Therefore, adopting technology is mandatory for work purposes, and the organisation bears the associated costs. Similarly, UTAUT model has been criticised, as this model was used to predict the behavioural INT of an employee to apply the technology while at work. By acknowledging the difference in an individual’s INT to use the technology in the mobile context, Ooi and Tan (Citation2016) proposed MTAM that was tailored for mobile technology, whereas previous models were mainly designed for other settings. Two primary variables were suggested in MTAM, namely MU and MEOU. Theoretically, MU in MTAM is similar to the perceived usefulness, and performance expectancy in TAM and UTAUT. At the same time, MEOU is identical to the perceived ease of use, and effort expectancy in both models.

However, due to limited explanatory power of the two initial variables, as suggested in MTAM, several additional variables are integrated into MTAM to increase the model comprehension. For example, optimism and personal innovativeness were added into MTAM for the study of mobile payment (Yan et al., Citation2021), and MI, MSE, perceived financial cost, and perceived risk were also included in MTAM to study the consumer’s INT to use wearable payment (Loh et al., Citation2022). Therefore, MTAM was determined to be the most appropriate model in this research context. It was extended with three personal factors (ATT, MSE, and MI), which were proven to be important in determining INT to use mobile technology (Chong et al., Citation2021; Lew et al., Citation2021; Loh et al., Citation2022). Meanwhile, evidence of the mobile investment platform providers’ PR, as an exogenous factor towards INT to use mobile investment is still scarce.

Hypotheses development

Mobile usefulness (MU)

Mobile usefulness (MU) is an individual’s perception of the enhancement in performance from using mobile technology (Ooi & Tan, Citation2016). With the advancement of mobile devices, the adoption of mobile technology, such as mobile investment is perceived to improve usefulness of the technology. When individuals perceive that mobile technology could enhance their performance, they will most likely adopt it. The significant role of usefulness in technology adoption was established in prior studies, but in different settings. For example, Lau et al. (Citation2021) revealed the significant influence of MU on INT to use mobile taxi booking. Wan et al. (Citation2022) found that MU significantly impacted mobile tourism shopping INT. Similarly, Ng et al. (Citation2022) remarked on the significant effect of MU on INT to use mobile fashion shopping. Loh et al. (Citation2022) revealed that MU significantly influenced wearable payment adoption INT. However, inconclusive findings on the role of usefulness on the behavioural INT to adopt technology were also revealed in some studies. For example, Sarmah et al. (Citation2021) found insignificant role of perceived usefulness on mobile wallet adoption INT of the millennials in India. Therefore, further studies should be conducted to investigate the effect of MU on INT to adopt mobile investment. The following hypothesis is proposed, as investors tend to use mobile investment if it provides more usefulness.

H1: MU has a positively significant relationship with INT to use mobile investment.

Mobile ease of use (MEOU)

According to Ooi and Tan (Citation2016), MEOU refers to an individual’s perception regarding the difficulty of learning and adopting mobile technology, such as mobile investment in this study. An individual is likely to use mobile technology if it does not need an extra effort to adopt such technology (Yan et al., Citation2021). Therefore, technology usage will increase if it does not require additional actions (Ng et al., Citation2022). Empirically, several studies examined the influence of MEOU on mobile technology adoption, and found a significant effect. Ng et al. (Citation2022) found that MEOU was substantially related to mobile fashion shopping use INT. Similarly, Loh et al. (Citation2022) also remarked on the same effect on wearable payment. The significant role of MEOU was also revealed in the mobile tourism shopping adoption INT (Wan et al., Citation2022). Lew et al. (Citation2021) further found that INT to use mobile wallets was also significantly influenced by MEOU. Unfortunately, contrary findings were also reported in some other studies (Ooi & Tan, Citation2016; Lau et al., Citation2021; Yan et al., Citation2021). According to Lau et al. (Citation2021), the effect of MEOU on INT to use technology was diminished due to the increased familiarity with mobile devices and simplicity of mobile services. With the inconclusive findings on the role of MEOU on INT, there is a need for further studies to examine this relationship again. The following hypothesis is suggested, as the investors are expected to be more likely to use mobile investment if it only requires minimal efforts.

H2: MEOU has a positively significant relationship with INT to use mobile investment.

Mobile self-efficacy (MSE)

The MSE is individuals’ perception of their ability to learn and use mobile technology (Lew et al., Citation2021). Individuals who believe they can perform the technology will have a favourable ATT towards the platform. This is aligned with Zhu et al. (Citation2010), who remarked that a higher self-efficacy could form a livelier ATT for m-auction. Similarly, in the context of self-service technology in libraries, Hsiao and Tang (Citation2015) also found that self-efficacy significantly influenced ATT. This postulated the effect of MSE on ATT, whereas ATT towards mobile investment could be enhanced through their self-efficacy. The investors are expected to have positive and favourable ATT if they have sufficient self-efficacy on mobile devices. Moreover, if individuals perceive that they have such efficacy to perform their investment through the mobile platform, they tend to use the mobile investment platform to manage their investments. The influence of MSE has been revealed in literature, such as Singh and Srivastava (Citation2020) who found that MSE significantly affected mobile banking usage. Similarly, Lew et al. (Citation2021) also showed a significant positive effect of MSE on INT to use a mobile wallet. Al-Saedi et al. (Citation2020) also found that mobile payment adoption INT was significantly influenced by self-efficacy. Nevertheless, literature also documented the insignificant influence of self-efficacy on ATT and INT. For example, Loh et al. (Citation2022) found that MSE did not significantly influence the wearable payment adoption INT. Besides the MSE, the insignificant impact of self-efficacy on technology adoption was also found in other contexts, such as smartphone fitness applications (Dhiman et al., Citation2020), mobile commerce (Tarhini et al., Citation2019), mobile payment (Lui et al., Citation2021), and the like. Therefore, the following statements are hypothesised to further investigate the effect of MSE on ATT and INT.

H3: MSE has a positively significant relationship with ATT to use mobile investment.

H4: MSE has a positively significant relationship with INT to use mobile investment.

Mobile innovativeness (MI)

The level of an individual’s willingness to try a new mobile technology is referred to as MI (Loh et al., Citation2022). When individuals are highly willing to try a new mobile technology, this could indicate that their MI is increased (Boateng et al., Citation2016). Therefore, they may have a good perception or positive ATT towards the mobile investment platform when innovativeness enhances their curiosity. This postulation is supported by studies of Boateng et al. (Citation2016) and Patil et al. (Citation2020), who revealed the positive significant influence of personal innovativeness on ATT towards mobile advertising and mobile payment, respectively. For that reason, MI is predicted to have a significant influence on ATT. Moreover, individuals could have a higher INT when they are highly innovative in using mobile technology. The substantial effect of individuals’ innovativeness towards their INT has been well documented. For example, Loh et al. (Citation2022) revealed that INT to use wearable payment was significantly influenced by MI. Similarly, the influence of an individual’s innovativeness on INT to adopt the technology was also found in other studies, such as live streaming service (Singh et al., Citation2021), mobile payment (Handarkho & Harjoseputro, Citation2020), mobile banking (Ho et al., Citation2020), and smartphone fitness application (Dhiman et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, insignificant influence of an individual’s innovativeness towards INT to use mobile payment was found by Yan et al. (Citation2021) and Lui et al. (Citation2021). Therefore, further studies should be conducted to explore the effects of MI on ATT and INT. The following hypotheses are proposed to be investigated in this study.

H5: MI has a positively significant relationship with ATT to use mobile investment.

H6: MI has a positively significant relationship with INT to use mobile investment.

Perceived reputation (PR)

Mobile investment is a platform designed for managing investment portfolios using mobile devices. Therefore, the mobile investment platform provider’s PR is expected to influence INT to use mobile investment platforms. As defined by Xin et al. (Citation2015), the service providers’ PR was the degree of an individual’s belief in the service provider regarding their competency, honesty, and benevolence. This signified that if the service provider has a good reputation, it will strengthen the individual’s ATT towards the platform. The user tends to adopt the platform that has a high reputation. Moreover, this PR is crucial for mobile technology, whereby the transaction is virtually done. Therefore, the platform provider’s PR is crucial for an individual to adapt its technology. The success of mobile transactions relies on the faithful and ethical practices of the mobile service providers and their technology (Xin et al., Citation2015). Dahlberg et al. (Citation2003) found that an individual was likely to use mobile payment if the vendors are well-known and established companies. Similarly, Warsame and Ireri (Citation2018) and Nguyen et al. (Citation2022) remarked on the crucial impact of reputation on Islamic banking and mobile banking adoption, respectively. Consequently, the following hypotheses are postulated.

H7: PR has a positively significant relationship with ATT to use mobile investment.

H8: PR has a positively significant relationship with INT to use mobile investment.

Attitude (ATT) toward mobile investment

Attitude (ATT) is the magnitude of an individual having a favourable or unfavourable assessment of technology. In this study, the ATT towards mobile investment is referred to as the individuals’ perception towards mobile investment platform, whether the perception is positive or negative. Theoretically, if an individual has a positive or favourable ATT towards technology, the INT to use that technology is higher than the negative or unfavourable perception. Significant influence of ATT towards INT has been widely recognised in literature. For example, Ho et al. (Citation2020) and Purohit and Arora (Citation2023) revealed that ATT significantly influenced INT to use mobile banking. Similarly, Chong et al. (Citation2021) also found that the individual’s INT to adopt mobile stock trading was significantly affected by ATT. The significant impact of ATT on mobile payment technology was also revealed by Bailey et al. (Citation2020), Flavian et al. (Citation2020), and Teng et al. (Citation2020). Therefore, the following hypothesis is suggested.

H9: ATT has a positively significant relationship with INT to use mobile investment.

The proposed research framework is provided in , developed from the discussion above.

Research methodology

The targeted population for this study was the investors in Malaysia, as this study aimed at examining the determinant factors that might significantly influence INT to use mobile investment platforms. Therefore, purposive sampling technique was used to gather the primary responses from the public. A screening question was included to ensure that only Malaysian investors participated in this study. A total of 213 completed responses were gathered through the survey. As suggested by the power analysis using G*Power software, 146 respondents were the minimum sample size for the proposed research model in this study. This sample size was determined through the priori power analysis using a medium effect size of 0.15, an alpha value of 0.05, and a power level of 0.95. Therefore, a final sample of 213 was sufficient to examine the framework of the study, as the number was greater than the suggested minimum sample size.

For the measurement items of the proposed model, a total of 28 measurement items were adapted from prior studies, and used to develop the study questionnaire. Specifically, four items each for MU and MEOU were adapted from a study by Lau et al. (Citation2021), while four items each for MSE, MI, and INT to use mobile investment were adapted from a study by Loh et al. (Citation2022). Additionally, four items for ATT towards mobile investment were adapted from Bailey et al. (Citation2020), and three items for the platform providers’ PR were adapted from Chandra et al. (Citation2010). However, three items were deleted due to the lower outer loading than 0.708, including MEOU1, MSE4, and MI3. The seven-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 to 7 for strongly disagree to strongly agree was used for respondents to measure the level of agreement on the measurement items.

The primary responses from participating respondents were collected using the online survey platform Google Forms from the Malaysian investors. The proposed research model was then analysed by utilising the partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) approach using the SmartPLS software. The Mardia’s multivariate normality test results showed that the data was not normally distributed, as the kurtosis coefficient (113.1198) was greater than 20 (Byrne, Citation2013; Kline, Citation2011). Therefore, PLS-SEM was the most appropriate technique for this study (Hair et al., Citation2019).

Data analysis

As presented in , 64% and 36% of the respondents were females and males, respectively. Regarding the age range, around one-fourth of the respondents were between 19- to 24-year-old, followed by 24% were between 25- to 29-year-old, and 30- to 34-year-old. At the same time, the other age range accounted for the remaining 27%. Moreover, around 64% of the respondents were single, and the remaining were married. Majority of the respondents were employees (59%), followed by students (24%), self-employed (15%), and others (2%). For the highest education level, 73% of respondents had at least a certificate, diploma, or bachelor’s degree, 16% had postgraduate degrees, and the remaining 11% only had primary or secondary education.

Table 1. Profiles of the respondents.

Assessment of measurement model

The two-stage analysis involved the measurement assessment, and structural models were performed. In the first measurement model assessment, some necessary reliability and validity tests were performed, and the results are provided in . Firstly, both the average variances extracted (AVE) and outer loading were used to assess the validity for both constructs and items level. The results showed that the convergent validity for both constructs and items was established, as the AVE value was greater than 0.5000 (Flavian et al., Citation2020). Additionally, all items had a loading value of greater than 0.7080 (Hair et al., Citation2017), except for three items (MEOU1, MSE4, and MI3) with loading values of lower than 0.7080, and thus were deleted. Both the composite reliability (CR) and Cronbach’s alpha were adopted, and all constructs had values of higher than 0.7000, indicating that reliability was also achieved. Additionally, the Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) correlation ratio was also performed to assess the discriminant validity. The result in showed that all values were lower than 0.9000, and the discriminant validity was also satisfactory (Henseler et al., Citation2015). Meanwhile, the variance inflation factor (VIF) for all the study constructs obtained from the full collinearity test suggested by Kock (Citation2015) is also presented in . The result showed that the data was absent from multicollinearity, as the VIF value was lower than 5 (Anwar et al., Citation2021; Hair et al., Citation2017).

Table 2. Results of reliability and validity tests.

Table 3. Discriminant validity using HTMT.

Assessment of structural model

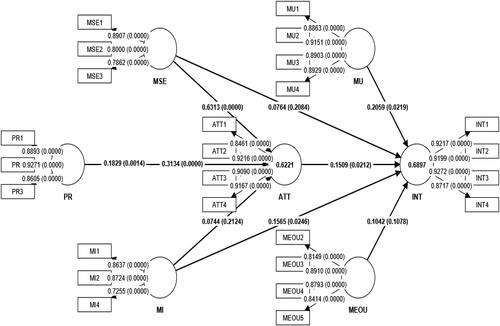

The study continued with the second stage of PLS-SEM by assessing the structural model. As shown at the bottom of , 62% of the variance in ATT was successfully explained by MSE, PR, and MI, while MU, MEOU, ATT, MSE, PR, and MI explained 69% of the variance in INT. Moreover, the predictive relevance (Q2) value of greater than zero also indicated the model predictive validity (Hair et al., Citation2017). According to Cohen (Citation1988), f2 was used to assess the effect size of the predictor. The result showed that MEOU and MSE did not affect INT, as f2 value was lower than 0.02, while MU, MI, and ATT showed a medium effect on INT, and PR significantly impacted INT. Similarly, MI did not affect ATT, while PR showed a medium effect, and MSE revealed a large effect on INT.

Table 4. Path coefficients and hypotheses testing.

As shown in and , three of the nine hypotheses were unsupported (H2, H4, and H5), while the remaining six were supported (H1, H3, H6, H7, H8, and H9). For example, two hypotheses that directed the relationship of MEOU (β = 0.1042) and MSE (β = 0.0764) to INT were not supported (H2 and H4), as the significant value was greater than 0.05 with a significance level (p > 0.05). Additionally, other predictors like MU (β = 0.2059), MI (β = 0.1565), PR (β = 0.3134), and ATT (β = 0.1509) had a significance value that was lower than 0.05 with a significance level (p < 0.05), and showed a significant relationship towards INT. Furthermore, the results showed MSE (β = 0.6313, p < 0.05) and PR (β = 0.1829, p < 0.05) had a significant influence on ATT, while insignificant for MI (β = 0.0744, p > 0.05). This result proved that additional factors, such as MI, PR, and ATT played a significant role in INT. Furthermore, the results demonstrated the substantial role of MSE and PR on ATT, before ATT significantly influenced INT.

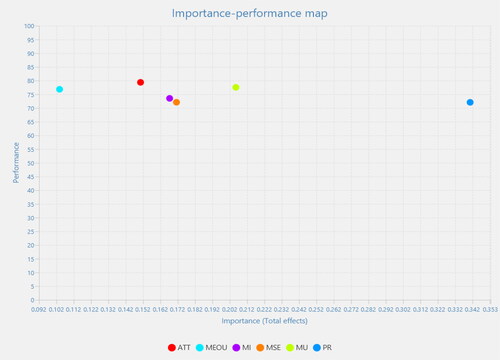

In addition to the path coefficient test through PLS-SEM, the study further examined each predictor’s importance and performance towards INT using the importance-performance map analysis (IPMA), and the results are provided in and . The IPMA result showed that only two constructs had an important value greater than the average, namely MU and PR. Three constructs performed better than the average performance value for the performance level: MU, MEOU, and ATT. The result indicated that although MEOU and ATT performed better than the average, their importance value was relatively low. This showed that the stakeholders should focus on improving performance of the crucial constructs that performed poorly, such as PR, MSE, and MI, but not on MEOU and ATT.

Table 5. Result of IPMA.

Discussions

This study examined the role of personal factors (MSE, MI, and ATT) and platform provider’s PR in INT to use a mobile investment platform. The results revealed that all four additional factors played different significant roles. For example, the result found that MU significantly influenced INT, which agreed with most prior studies and revealed similar findings in other contexts (Loh et al., Citation2022; Ng et al., Citation2022; Wan et al., Citation2022). The significant influence of MU on INT indicated that investors tend to use mobile investment platforms to invest if they perceive that using these platforms could enhance their usefulness in investment. However, the insignificant association of MEOU with INT was contradicted by Ng et al. (Citation2022), Lew et al. (Citation2021), Wan et al. (Citation2022), and others. Nevertheless, it was in line with Lau et al. (Citation2021) and Yan et al. (Citation2021), who also documented similar insignificant influence of MEOU on INT in different platforms. A possible reason for this insignificant finding was that the study respondents were mainly focused on existing investors, and dominated by working adults and the young generation, like Generation Z, who usually have a certain level of knowledge and technology savvy (Ling et al., Citation2023). These groups of respondents usually are those who have experience in using other mobile technologies, and thus operating a mobile investment platform is a simple task for them. According to Lau et al. (Citation2021), familiarity of users on mobile platforms and simplicity of mobile technology had diminished the role of MEOU on INT. Therefore, investors will perceive that using a mobile investment platform to make their investment is relatively easy, and they do not require additional effort or cost when investing through a mobile investment platform. Consequently, ease of using mobile investment platforms is not the significant factor driving them to use the technology.

The significant relationship between MSE on ATT provided new evidence in literature, as this association is limited in previous studies. This signified that the investors’ self-efficacy could enhance their ATT towards mobile investment platform if they can invest using it. However, an unexpected finding was derived in this study, as the result showed that MSE did not significantly impact the investor’s INT to use mobile investment platforms, and it was opposed in several studies (Al-Saedi et al., Citation2020; Lew et al., Citation2021; Singh & Srivastava, Citation2020). The result showed that the investors’ self-efficacy did not improve the likelihood of using mobile investment. This could be due to the study population was focused on the investors, and the study respondents’ composition was dominated by the working adult and young generation. Therefore, they tend to have a high ability to perform such mobile technologies, such as mobile payment, mobile commerce, and the like. With the high abilities of such mobile technologies, the investors may be self-confident in adopting this innovative platform. When investors have much higher ability and confidence in adopting any mobile technologies, it may offset the influence of self-efficacy on their INT to use. This finding was unlike the conventional assumption, whereby individuals were inclined to use certain technologies when they were highly self-efficacy, as the focus of the study was on the existing investors, and not the ordinary people. Therefore, the insignificant influence of MSE on INT to use mobile investment platforms could be expected.

The result also showed that MI influenced ATT and INT differently. It revealed the insignificant relationship of MI on ATT, and proved that the investors’ innovativeness did not impact the investors’ ATT on mobile investment platforms. This result is quite surprising, as individuals usually will have positive ATT towards certain technologies or platforms if they are more innovative. The findings showed that even though the investors were willing to try a new technology, such as mobile investment platforms, when they were more innovative, it would not be established as a favourable ATT towards the platform. This result signified that the investors may perceive that the practicality of mobile investment platforms is more realistic compared to the favourability. As the main objective of the investors is to generate profits from their investment, the usefulness of the platform is their main concern, not the favourability of the platform, as found in this study. Investors generally have high self-confidence in their investment decisions, and thus their innovativeness do not affect their favourability of the mobile investment platform. Moreover, investors have sufficient information on the advantages of mobile investment platform; their innovativeness do not impact their favourability. However, the significant influence of MI on INT was found in this study, and it was paralleled with previous evidence in different contexts (Dhiman et al., Citation2020; Ho et al., Citation2020; Loh et al., Citation2022). The significant relationship between MI on INT denoted that the investors are likely to use mobile investment platforms if they are highly innovative with new technology.

The result further proved the significant influence of PR on ATT and INT. A mobile investment platform is a platform that uses mobile devices to perform an investment. Therefore, the platform providers’ reputations are considered to be critical to the adoption decision. As postulated in this study, the result proved that the platform providers’ PR significantly influenced ATT, as favourable ATT could be built if the platform providers have good reputations. Additionally, a good reputation of the platform providers created a good and favourable ATT. It significantly influenced the investors’ INT to use the mobile investment platform (Dahlberg et al., Citation2003; Nguyen et al., Citation2022; Warsame & Ireri, Citation2018). Investors are highly willing to invest in mobile platforms if the platform providers have good reputations. Lastly, the study also proved the significant association of ATT-INT (Bailey et al., Citation2020; Chong et al., Citation2021; Teng et al., Citation2020). The investors are more likely to invest in using mobile investment platforms with the favourable and positive ATT towards mobile investment.

Implications

Despite the research gap in literature, this study aimed at discovering this unknown information through a novel research framework. Therefore, this study theoretically expanded the stage of knowledge in mobile technology adoption and behavioural finance as the new shred of evidence provided in this study. Firstly, the study contributed to the extant knowledge of mobile technology adoption in the mobile investment platform context. Previous studies mostly focused on mobile technology adoption in other contexts, such as mobile payment, mobile tourism, and mobile shopping, but deficiency in mobile investment platforms. Therefore, this study could enrich the literature by disclosing this perspective. Additionally, given that MTAM was only limited to two variables, MU and MEOU, these two variables were referred to as the technology factors. Therefore, the additional factors that might influence investors to use mobile investment platforms should be added. In this study, MTAM was integrated with three personal factors, namely MSE, MI, and ATT. Technology adoption is usually influenced by diverse factors, not only technology factors, as suggested in MTAM, but also personal factors. Additionally, influence of the platform providers’ reputations on their adoption should not be neglected, as the investors will only use reputable platforms. Therefore, the three personal factors and platform provider’s PR were integrated into MTAM to form a novel research framework that could predict mobile investment adoption comprehensively. As proven in this study, all additional constructs were crucial in determining INT to use a mobile payment platform. These significant findings showed that by adding other constructs in the initial model (MTAM) was vital as it did not capture the special and unique features of the subject matter.

Moreover, this study offered practical implications to stakeholders, such as the regulators, platform providers, investment companies, and others. According to the study, these stakeholders could design some effective strategies and policies to encourage the adoption of mobile investment. For example, platform providers should increase the platform usefulness to enhance usage of the mobile investment platform. Numerous analytic features, including fundamental and technical analysis could be embedded in the mobile investment platform to ease investment decision-making, especially in selecting stocks, and also in determining the timing of investing. Additionally, the development of artificial intelligence, robotic advisory, and big data analytics may be integrated into the mobile investment platform to increase the platform usefulness. As proven in this study, investors are more likely to use mobile investment platforms if the platforms can offer some benefits and provide them with more usefulness.

Furthermore, the investor’s factors played an important role, and thus stakeholders should be focused when they wish to increase the usage of mobile investment platform. For example, stakeholders have to increase the investors’ innovativeness through several programmes and campaigns. Sometimes, the investors are unwilling to accept the new technology, as they are unfamiliar and afraid to use it. Several programmes and campaigns may increase understanding of the technology and improve its innovativeness, thereby encouraging investors to accept the technology. Mobile investment platform providers should consider implementing features that cater to the investors’ ATT towards investing, as ATT significantly affects investors’ INT to use the platform. Providers may consider offering innovative and unique features that differentiate their platforms from the competitors. To reduce perceived financial costs, providers could consider offering lower fees or discounts for using the mobile platform over other investment channels, which could increase investors’ INT to use the platform. Therefore, investors will use those platforms to manage their investments. Moreover, establishing a favourable ATT on mobile investment is also essential to increase the adoption of mobile investment.

Additionally, platform providers should increase their reputations, as it was an essential factor driving investors to use their platforms. A good reputation usually directly affects users’ confidence in the platform they are about to adopt. The higher the reputation, the more confidence the users generally have; they feel more comfortable using that platform. Therefore, platform providers should constantly enhance and improve the platform to prevent any unexpected issues, such as scams and fraud that may reduce the investor’s confidence in them. Furthermore, privacy and confidentiality of the platform investors should be a priority to the platform providers. Moreover, regulatory agencies have to offer more laws and regulations to protect the investors that use mobile investment as their investment platforms. Investors may have a positive ATT on mobile investment if the platform providers have good reputations. Eventually, investors will be more confident about the platform if they perceive that using a mobile investment platform is safe and secure for their investment management. This could increase their INT to use the platform for their investment.

Stakeholders are urged to increase the investors’ self-efficacy to form a favourable ATT towards mobile investment. Training and programmes could improve the investors’ abilities and skills. Moreover, the platform may provide some trial versions for the investors to perform investment trials to get them familiar with the portal, and interfaces of the mobile platform before they engage in the actual investment. This could enhance the investors’ abilities and skills to invest through mobile investment platforms, as the portal and interfaces of mobile investment might be slightly different from the internet or online investment. When investors are perceived to have such ability in performing investment using the mobile investment platform, this would lead to establishing a more favourable ATT on mobile investment, and could encourage the investors to use mobile investment platform.

Conclusions, limitations, and suggestions for future study

The advancement of mobile technology has raised the research in these areas, such as mobile payment, mobile tourism, mobile shopping, and the like. However, the adoption of mobile investment platform is still under-researched, especially from the perspective of the investors’ personal factors and platform providers’ PR. Therefore, this study investigated the factors determining INT to use mobile investment platforms by considering the role of personal factors (MSE, MI, and ATT), and platform provider’s PR. An extended MTAM model was developed in this study to propose a novel framework that could examine this matter comprehensively. Using purposive sampling, 213 investors in Malaysia participated in this study. PLS-SEM was subsequently used to analyse the data, as the collected responses were not normally distributed. The results showed that personal factors (MSE, MI, and ATT) and PR played crucial roles in determining INT to use mobile investment platforms. Specifically, ATT was significantly impacted by MSE and PR, while MU, MI, PR, and ATT influenced INT to adopt mobile investment considerably. This finding proved that all additional constructs that represented personal factors and the platform provider’s PR were essential to promote the usage of mobile investment, either directly to INT or directly to ATT. However, the findings also revealed insignificant influence of MEOU on INT, MSE on INT, and MI on ATT. The possible reasons for these insignificant findings could be due to that the study targeted respondents was mainly focused on existing investors and not the general public. Moreover, the respondents’ composition in the study was mainly dominated by highly educated and young investors, with easiness and self-efficacy seen to be less important in cultivating their INT to use mobile investment platforms. Similarly, although innovativeness was crucial in driving investors to use mobile investment platforms, this innovativeness did not form a favourable ATT on the mobile investment platform.

Although this study offered some important contributions and implications theoretically and practically, several limitations are still present in this study. For example, this study examined the investors’ INT to adopt a mobile investment platform for their investment by using an extended MTAM model, with three constructs, representing personal factors (MSE, MI, and ATT) and the platform providers’ PR. Some other essential constructs that may represent different perspectives are not included in the current research framework. Therefore, further studies are suggested by using different perspectives, such as self-determination theory or push-pull motivation theory to study the matter comprehensively. Additionally, the study only focused on direct relationships of the constructs, and this might limit valuable information of the findings. Examining the indirect relationships through mediators, or investigating the moderating role in the study could be considered in future studies, as human decision-making is more complex than direct relationships. For instance, evidence in prior studies revealed and proposed the mediating effect of several personal-factor in different contexts, such as perceived experience (Sinha & Singh, Citation2023), empathy (Elche et al., Citation2020), ethical values, and transcendent motives (Martinez-Canas et al., Citation2016), and the like. By including some of these mediators in the study, it could further explain the sequential mechanism that usually involved in complex human decision making process. Furthermore, this study only concentrated on investors in Malaysia, and thus it might limit the generalisability of the study. Therefore, further investigation is recommended to include the perspective of other participants, such as the non-investors, older investors, and others, to provide more solid findings. Moreover, quite a number of investors still prefer to invest traditionally. Consequently, examining the barrier that inhibit investors from using mobile investors’ platforms could complete the literature regarding mobile investment. Lastly, as the respondents were assumed to be homogeneous, the differences between the respondents were not explored in this study. It would be interesting if future studies could examine the differences between the respondents by comparing the result of the respondents’ sub-groups, such as male vs female, younger generation vs older generation, and others to offer a more comprehensive evidence, as the sub-groups of the respondents might behave differently.

Measurement items

Mobile Usefulness – Adapted from Lau et al. (Citation2021)

Using mobile investment platforms enhances my investment experience.

Using mobile investment platforms helps me save time.

I find mobile investment platforms useful in my daily life.

Using a mobile investment platform gives me greater control over my investment portfolio.

Mobile Ease of Use – Adapted from Lau et al. (Citation2021)

Interaction with mobile investment does not require a lot of intellectual effort.

It would be easy for me to become skilful at using mobile investment.

Learning how to use mobile investment would be easy for me.

Mobile investment is flexible to interact with.

Overall, I find mobile investment easy to use.

Mobile Self-Efficacy – Adapted from Loh et al. (Citation2022)

I feel confident using the mobile investment to complete my investment efficiently.

I feel confident using the mobile investment to make my investment even if there was no one around to tell me how it works.

I feel confident using the mobile investment to make my investment if I had only the step-by-step manual for reference.

I feel confident using the mobile investment to make my investment if I had just the built in-help facility for assistance (e.g. Apple, Siri, Google Assistant).

Mobile Innovativeness – Adapted from Loh et al. (Citation2022)

I am interested in exploring new mobile investment technologies.

If I hear about a new mobile investment technology, I will look for ways to experiment with it.

Among my peers, I am usually the first to explore new mobile investment technologies.

I think I will use the mobile investment to make my investment even if I do not know anyone else who has done it before.

Perceived Reputation of Mobile Investment Service Provider – Adapted from Chandra et al. (Citation2010)

I believe this mobile service provider (such as Touch n Go, Raiz, etc.) has a good reputation.

I believe this mobile service provider (such as Touch n Go, Raiz, etc.) has a reputation for being fair.

I believe this mobile service provider (such as Touch n Go, Raiz, etc.) has a reputation for being honest.

Attitude toward Mobile Investment – Adapted from Bailey et al. (Citation2020)

Using a mobile investment platform is a good idea.

Using a mobile investment platform is beneficial.

I have a positive attitude toward using mobile investment platforms.

I have a positive attitude toward using mobile investment platforms.

Intention to use Mobile Investment – Adapted from Loh et al. (Citation2022)

I am open to use a mobile investment to make my investment in the near future.

Given the opportunity, I will use the mobile investment to make my investment.

I am likely to use the mobile investment to make my investment in the near future.

I intend to use the mobile investment to make my investment if the opportunity arises.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Pick-Soon Ling

Pick-Soon Ling is a Lecturer at the School of Business and Management, University of Technology Sarawak (UTS). He graduated with a PhD, a Master of Economics, and a Bachelor of Business Administration with Honours from the National University of Malaysia (UKM).

Kelvin Yong Ming Lee

Kelvin Yong Ming Lee is a Senior Lecturer at the School of Accounting and Finance, Taylor’s University. He graduated with a PhD (Finance), MSc (Finance) and a Bachelor of Finance with Honours from the Universiti Malaysia Sarawak (UNIMAS).

Liing-Sing Ling

Liing-Sing Ling is a Lecturer at the School of Business and Management, University of Technology Sarawak (UTS). Besides she is also a Fellow member of the Association of Chartered Certified Accountants (ACCA) and member of the Malaysian Institute of Accountants.

Mohd Kamarul Anwar Mohd Suhaimi

Mohd Kamarul Anwar Mohd Suhaimi is a Law Lecturer at the School of Business and Management, University of Technology Sarawak. He was formerly admitted as an advocate and solicitor of the High Court of Malaya.

References

- Al-Saedi, K., Al-Emran, M., Ramayah, T., & Abusham, E. (2020). Developing a general extended UTAUT model for M-payment adoption. Technology in Society, 62, 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101293

- Anwar, R.H., Zaki, S., Thurasamy, R., & Memon, N. (2021). Trait emotional intelligence and ESL teacher effectiveness: Assessing the moderating effect of demographic variables using PLS-MGA. Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues, 24(6), 1–17. https://www.abacademies.org/articles/trait-emotional-intelligence-and-esl-teacher-effectiveness-assessing-the-moderating-effect-of-demographic-variables-using-plsmga-12943.html

- Ariffin, S.K., Rahman, M.F.R.A., Muhammad, A.M., & Zhang, Q. (2021). Understanding the consumer’s intention to use the e-wallet services. Spanish Journal of Marketing ESIC, 25(3), 446–461. https://doi.org/10.1108/SJME-07-2021-0138

- Bailey, A.A., Pentina, I., Mishra, A.S., Mimoun, M.S.B. (2020). Exploring factors influencing US millennial consumers’ use of tap-and-go payment technology. International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 30(2), 143–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593969.2019.1667854

- Boateng, H., Okoe, A.F., & Omane, A.B. (2016). Does personal innovativeness moderate the effect of irritation on consumers’ attitudes towards mobile advertising? Journal of Direct, Data and Digital Marketing Practice, 17, 201–210. https://doi.org/10.1057/dddmp.2015.53

- Byrne, B.M. (2013). Structural equation modelling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications and programming. Routledge.

- Chandra, S., Srivastava, S.C., & Theng, Y.L. (2010). Evaluating the role of trust in consumer adoption of mobile payment systems: An empirical analysis. Communications of the Association for Information System, 27(1), 561–588. https://doi.org/10.17705/1CAIS.02729

- Chong, L-L., Ong, H-B., & Tan, S-H. (2021). Acceptability of mobile stock trading application: A study of young investors in Malaysia. Technology in Society, 64, 101497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101497

- Cohen, E. (1988). Authenticity and commoditisation in tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 15(3), 371–386. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(88)90028-X

- Dahlberg, T., Mallat, N., & Oorni, A. (2003). Trust enhanced technology acceptance model consumer acceptance of mobile payment solutions: Tentative evidence. Stockholm Mobility Roundtable, 22(1), 145.

- Dhiman, N., Arora, N., Dogra, N., & Gupta, A. (2020). Consumer adoption of smartphone fitness apps” an extended UTAUT2 perspective. Journal of Indian Business Research, 12(3), 363–388. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIBR-05-2018-0158

- Elche, D., Ruiz-Palomino, P., & Linuesa-Langreo, J. (2020). Servant leadership and organizational citizenship behavior: The mediating effect of empathy and service climate. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 32(6), 2035–2053. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-05-2019-0501

- Fan, L. (2022). Mobile investment technology adoption among investors. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 40(1), 50–67. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-11-2020-0551

- Flavian, C., Guinaliu, M., & Lu, Y. (2020). Mobile payments adoption – Introducing mindfulness to better understand consumer behavior. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 38(7), 1575–1599. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-01-2020-0039

- Hair, J.F., Hult, G.T.M., Ringle, C.M. & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Hair, J.F., Risher, J.J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C.M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Handarkho, Y.D., & Harjoseputro, Y. (2020). Intention to adopt mobile payment in physical stores: Individual switching behaviour perspective based on Push-Pull-Mooring (PPM) theory. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 33(2): 285–308. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEIM-06-2019-0179

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C.M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modelling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Hikida, R., & Perry, J. (2020). FinTech trends in the United States: Implications for household finance. Public Policy Review, Policy Research Institute, Ministry of Finance Japan, 16(4), 1–32. https://www.mof.go.jp/english/pri/publication/pp_review/ppr16_04_03.pdf

- Ho, J.C., Wu, C-G., Lee, C-S., & Pham, T-T. (2020). Factors affecting the behavioural intention to adopt mobile banking: An international comparison. Technology in Society, 63, 101360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101360

- Hsiao, C-H., & Tang, K-Y. (2015). Investigating factors affecting the acceptance of self-service technology in libraries: The moderating effect of gender. Library Hi Tech, 33(1), 114–133. https://doi.org/10.1108/LHT-09-2014-0087

- Kline, R.B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

- Kock, N. (2015). Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. International Journal of e-Collaboration, 11(4), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijec.2015100101

- Lau. A.J., Tan, G. W-H., Loh, X-M., Leong, L-Y., Lee, V-H., & Ooi, K-B. (2021). On the way: Hailing a taxi with a smartphone? A hybrid SEM-neural network approach. Machine Learning with Applications, 4, 100034. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mlwa.2021.100034

- Lew, S., Tan, G.W-H., Loh, X-M., Hew, J-J., & Ooi, K-B. (2021). The disruptive mobile wallet in the hospitality industry: An extended mobile technology acceptance model. Technology in Society, 63, 101430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101430

- Lin, C-P., & Huang, H-Y. (2021). Modeling investment intention in online P2P lending: An elaboration likelihood perspective. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 39(7), 1134–1149. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-12-2020-0594

- Ling, P-S, Chin, C-H, Yi, J., & Wong, W.P.M. (2023). Green consumption behaviour among Generation Z college students in China: The moderating role of government support. Young Consumers. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1108/YC-01-2022-1443

- Loh, X-M., Lee, V-H., Tan, G.W-H., Hew, J-J., & Ooi, K-B. (2022). Towards a cashless society: The imminent role of wearable technology. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 62(1), 39–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/08874417.2019.1688733

- Lui, T.K., Zainuldin, M.H., Yii, K-Y., Lau, L-S., & Go, Y-H. (2021). Consumer adoption of Alipay in Malaysia: The mediation effect of perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness. Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences & Humanities, 29(1), 389–418. https://doi.org/10.47836/pjssh.29.1.22

- Martinez-Canas, R., Ruiz-Palomino, P., Linuesa-Langreo, J., & Blazquez-Resino, J. (2016). Consumer participation in co-creation: An enlightening model of causes and effects based on ethical values and transcendent motives. Frontiers in Psychology, 7(793). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00793

- Nair, P.S., Shiva, A., Yadav, N., Tandon, P. (2023). Determinants of mobile apps adoption by retail investors for online trading in emerging financial markets. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 30(5), 1623–1648. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-01-2022-0019

- Ng, F. Z-X., Yap, H-Y., Tan, G. W-H., Lo, P-S., & Ooi, K-B. (2022). Fashion shopping on the go: A dual-stage predictive-analytics SEM-ANN analysis on usage behaviour, experience response and cross-category usage. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 65, 102851. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102851

- Nguyen, Y.T.H., Tapanainen, T., & Nguyen, H.T.T. (2022). Reputation and its consequences in Fintech services: The case of mobile banking. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 40(7), 1364–1397. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-08-2021-0371

- Ooi, K-B., & Tan, G.W-H. (2016). Mobile technology acceptance model: An investigation using mobile users to explore smartphone credit card. Expert Systems with Applications, 59, 33–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2016.04.015

- Patil, P., Tamilmani, K., Rana, N.P., & Raghavan, V. (2020). Understanding consumer adoption of mobile payment in India: Extending Meta-UTAUT model with personal innovativeness, anxiety, trust and grievance redressal. International Journal of Information Management, 54, 102144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102144

- Purohit, S., & Arora, R. (2023). Adoption of mobile banking at the bottom of the pyramid: An emerging market perspective. International Journal of Emerging Market, 18(1), 200–222. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOEM-07-2020-0821

- Sarmah, R., Dhiman, N., & Kanojia, H. (2021). Understanding intentions and actual use of mobile wallets by millennials: An extended TAM model perspective. Journal of Indian Business Research, 13(3), 361–381. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIBR-06-2020-0214

- Singh, S., & Srivastava, R.K. (2020). Understanding the intention to use mobile banking by existing online banking customers: an empirical study. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 25, 86–96. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41264-020-00074-w

- Singh, S., Singh, N., Kalinic, Z., Liebana-Cabanillas, F.J. (2021). Assessing determinants influencing continued use of live streaming services: An extended perceived value theory of streaming addiction. Expert Systems with Applications, 168, 114241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2020.114241

- Sinha, N., & Singh, N. (2023). Moderating and mediating effect of perceived experience on merchant’s behavioral intention to use mobile payments services. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 28, 448–465. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41264-022-00163-y

- Tarhini, A., Alalwan, A.A., Shammout, A.B., & Al-Badi, A. (2019). An analysis of the factors affecting mobile commerce adoption in developing countries: Towards an integrated model. Review of International Business and Strategy, 29(3), 157–179. https://doi.org/10.1108/RIBS-10-2018-0092

- Teng, P.K., Heng, B.L.J., Abdullah, S.I.N.W., Ping, W.T., & Yao, X.J. (2020). Consumer adoption of mobile payments: A distinctive analysis between China and Malaysia. International Journal of Business Continuity and Risk Management, 10(2/3), 207–223. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBCRM.2020.108505

- Wan, S-M., Cham, L-N., Tan, G.W-H., Lo, P-S., Ooi, K-B., & Chatterjee, R-S. (2022). What’s stopping you from migrating to mobile tourism shopping? Journal of Computer Information Systems, 62(6), 1223–1238. https://doi.org/10.1080/08874417.2021.2004564

- Warsame, M.G., & Ireri, E.M. (2018). Moderation effect on Islamic banking preferences in UAE. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 36(1), 41–67. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-08-2016-0121

- Xin, H., Techatassanasoontorn, A.A., & Tan, F.B. (2015). Antecedents of consumer trust in mobile payment adoption. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 55(4), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/08874417.2015.11645781

- Yan, C., Siddik, A.B., Akter, N., & Dong, Q. (2023). Factors influencing the adoption intention of using mobile financial service during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of FinTech. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30, 61271–61289. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-17437-y

- Yan, L-Y., Tan, G. W-H., Loh, X-M., Hew, J-J-., & Ooi, K-B. (2021). QR code and mobile payment: The disruptive forces in retail. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 58, 102300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102300

- Zhu, G., Sangwan, S., & Lu, T-J. (2010). A new theoretical framework of technology acceptance and empirical investigation on self-efficacy-based value adoption model. Nankai Business Review, 1(4), 345–372. https://doi.org/10.1108/20408741011082543