Abstract

This study examines the effect of pricing practices and other factors on consumers’ buying behavior in the UAE in the post-Covid-19 era. The focus is on buying from hypermarkets. Other factors such as product quality, the possibility of paying with cards, convenient hypermarket layout, near location, not-crowded hypermarkets, and the way prices are written are also investigated. The effects of factors such as gender, marital status, age, income, education, and shopping frequency were examined. A questionnaire built based on a literature review was used to collect data from 180 respondents in the UAE. Statistical methods such as the one-sample t-test, two-sample t-test, ANOVA, and correlation were utilized. R statistical tool was used for data analysis. Results showed that product quality is more important than lower prices. However, lower prices are still a key factor that determines where consumers will buy from and how much they will buy. Highly educated consumers place more importance on a well-designed hypermarket with wide aisles and not being crowded. Generally, factors other than prices are also important. Men and married people care more about prices than other respondents. For this reason, they look for good prices in distant hypermarkets. Decision-makers need to consider such factors and focus on improving customer service to increase customer loyalty. It is also essential for them to keep up with the changing preferences and needs of their customers.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

After the COVID-19 era, customers’ expectations started to change. In the post-COVID era, the tendency for online shopping has increased. However, this tendency is different from one country to another (Higueras-Castillo et al., Citation2023). People still need to come to traditional physical hypermarkets. However, because of the pandemic, many people lost their jobs, and others had salaries reductions. Therefore, people are more sensitive to prices. Retailers need to offer the best prices (Fares et al., Citation2023). Besides the prices, the product’s quality is very important in the post-COVID era (De & Singh, Citation2023). Retailers must cope with the changes in these expectations. For example, changes in the layout of the hypermarkets to highlight hygiene products were necessary (Wang et al., Citation2020). Customers started to prefer hypermarkets with wide aisles to reduce the probability of being infected. Customers started to depend more on new technologies such as touch-free and highly automated shopping (Díaz-Martín et al., Citation2021). The tendency for impulse buying has increased. The frequency of buying and buying patterns were changed because of the psychological effect of COVID-19 (Naeem, Citation2020). Recent inflation of oil prices made customers more sensitive to traveling for long distances (Kurniawan et al., Citation2022), therefore, the location of the hypermarket became more important.

Consumers in the GCC countries are increasingly turning to modern retail formats, especially hypermarkets, to satisfy their needs (Belwal & Belwal, Citation2017). In hot weather, especially in the summer, people tend to look for malls as one option to spend time, and for friends to meet. Customers are attracted to hypermarkets through special offers and product promotions. Hypermarkets provide customers with a wide range of products at competitive prices, making them a preferred choice for many shoppers. Their features provide convenience for consumers, as they can find a wide variety of items in one place. Hypermarkets also have large spaces, making them an ideal place to shop for large quantities of items (Ghaffarkadhim et al., Citation2019). Some consumers prefer to come frequently and buy a few items, and others prefer to come only once a week and make large purchases. Retailers must be aware of these different types of shoppers and adjust their strategies accordingly. Retailers should tailor their marketing and promotional efforts to these different types of shoppers.

Price promotions can help to increase sales by increasing customer loyalty, as consumers are more likely to purchase items if they are offered at discounted prices (Hallikainen et al., Citation2022). As a collection of decision-making processes, consumer-buying behavior is determined by both internal and external factors. Internal factors include personal needs and motivations, while external factors include social and economic influences (Sharma & Sonwalkar, Citation2013). For example, consumers prefer not-crowded hypermarkets. This is because they can easily find what they need without having to wait in long queues. Shopping in not-crowded hypermarkets also reduces stress and helps customers feel more relaxed. One form of increasing sales is impulse buying, which usually occurs when a person is exposed to a product, a promotional offer, or a temptation. It can be a quick decision, usually unplanned, and is driven by the desire to have immediate gratification. It is often triggered by an emotional response or an attractive product display. For instance, when a store offers a discount on a product, it is likely to lead to an impulse buy from a customer who was not planning to purchase it before (Bhakat & Muruganantham, Citation2013). Additionally, customers may be more likely to return to the store in the future, knowing that they can find discounted items. This could lead to repeat customers and increased sales.

Since the customers’ expectations can vary from one country to another, this study aims to examine the effect of promotions in hypermarkets in the UAE on the behavior of consumers. It considers the effect of pricing strategies and other factors such as proximity to consumers, good layout of the place, high-quality products, and others. The study examines if discounts and other factors really affect customer preferences. The study also checks the effect of factors such as gender, education, marital status, frequency of shopping, and income on the buying behavior of consumers. Such a study with this objective was not conducted in the UAE, not before, and not even after the pandemic. Therefore, the study investigates this research gap. The study can be a guide for hypermarkets management to make the right decisions regarding variables that affect the behavior of consumers. This knowledge can help optimize the marketing strategies of hypermarkets and understand the changing needs of their customers. Retailers need to take some actions to respond to changes in the expectations of customers, to survive in the market.

2. Literature review

In this section, first, the literature about the factors that affect shopping behavior is presented. Then the effect of economic crises, Covid-19, and political conflict is written. After that, the effecting factors on shopping behavior in the region in general and the UAE, in particular, are presented. Then other regions such as India and Pakistan are examined. Then, a literature review about promotions’ effect on healthy and unhealthy food demand was presented. Finally, more about the gap in the research is discussed.

Different factors can affect the choices of consumers. Customer perception of mall value is influenced by the mall environment (El-Adly & Eid, Citation2016). For example, Zhou and Wong (Citation2004) examined the impact of retail store environment variables such as music, lighting, and social interaction on consumer impulse buying behavior. Moreover, five variables were considered in a study by Fikri et al. (Citation2020), including purchase decision, price, service quality, promotion, and lifestyle. Retail IJC Mart purchasing decisions were influenced by these variables during the Coronavirus pandemic. A positive relationship was found between price and service quality when it comes to purchasing decisions. According to Hernández et al. (Citation2011), socioeconomic characteristics such as age, gender, and income do not affect online shopping. Furthermore, a study by Maulana and Novalia (Citation2019) examined the effect of shopping lifestyle and positive emotions on impulse buying of customers at the Palembang City hypermarket. The data was from a sample of 150 people. Both variables were found to have a significant effect on impulse buying. Noor (Citation2020) also found that price discount has a positive significant impact on impulse buying. Greenacre and Akbar (Citation2019) examined the effect of payment methods on low-income shoppers’ shopping behavior. They found that Cashless Debit Cards made the overall grocery market more inelastic, while in-store spending remained stable. In a study by Cakici and Tekeli (Citation2022), the price level perceptions and emotional responses of consumers to supermarkets were examined as mediators. According to that study, consumers’ price sensitivity, perceptions of cheapness, perceptions of expensiveness, and positive feelings toward supermarkets affected their purchase intention.

Consumer purchasing habits changed during the global economic crisis of 2007/2008, according to a study by Sharma and Sonwalkar (Citation2013). As a result, consumers became more responsible, economical, and demanding. This behavior increased during the pandemic because many people lost their jobs, or suffered from the reduction of salaries (Fares et al., Citation2023). The financial dimension has been found more critical recently, especially during the conflict of Russia and Ukraine, where prices of food witnesses unprecedented price hikes. McColl et al. (Citation2020) evaluated the financial impact of supermarket sales promotions based on the amount of new demand generated from cannibalizing the base product. The impact of price cuts was examined. In a study by Bashir et al. (Citation2020), lean concepts were applied to the warehouse shipping process in a major supermarket chain. They found that lean concepts emphasize streamlining processes and eliminating waste. This reduces the amount of time and resources needed to complete the process, resulting in time and cost savings. These savings give the hypermarkets the possibility to make further price reductions. Besides looking for better prices, consumers have new shopping behaviors such as looking for wide-aisle and nearby hypermarkets (Wang et al., Citation2020).

Some studies focus on the GCC region in general and the UAE in particular. For example, in a study by Joghee et al. (Citation2021), a special focus was placed on malls in the UAE to study impulse buying behavior among expats. 450 respondents were selected by purposive sampling for this purpose. According to their findings, respondents in the 30–40-year-old age group, businessmen, who visit the mall every day and shop with their siblings, have the highest level of perception of impulse buying behavior. The researchers also found that external factors greatly influenced expats’ impulsive purchases in malls in the UAE. Moreover, to analyze and determine the company’s success, Sandybayev (Citation2019) examined Carrefour in the UAE by implementing supply chain management. Bhalla and Bhalla (Citation2023) found that Carrefour in the UAE gained a new strategic perspective due to the COVID-19 pandemic that exposed its updated marketing plans. For example, there were heavy discounts on products at Carrefour. A study by Belwal and Belwal (Citation2014) examined consumer behavior toward hypermarket preferences in Oman. Their study was conducted using 164 completed questionnaires. They found that hypermarkets are not only visited by consumers for purchases but also for recreation. They also found that customers are willing to spend more time in hypermarkets. Choosing hypermarkets is influenced by factors such as cleanliness, quality, payment counter efficiency, variety, and parking facilities. A study by Gaytan et al. (Citation2020) examined the impact of promotional variables on consumer buying behavior in Oman. Consumer buying and decision-making behavior are significantly influenced by all promotion-mix variables. Consumer psychology and buying behavior and their relationship to prices were examined in a study by Al-Salamin and Al-Hassan (Citation2016). Al-Hassa region participants in Saudi Arabia were asked to fill out a questionnaire. There were 433 responses with a 43.3% response rate. The findings show that prices and consumer buying behavior are positively related. Another study in Saudi Arabia is the one by Rahman (Citation2023), where the effect of services, price, location, atmosphere, and convenience on shopping behavior was examined. They found that gender, age, ethnicity, and social stratification have effects on the perception of the respondents.

There are other studies conducted in other regions, and similar main results were found in such regions. For example, a study by Khan et al. (Citation2019) examined the effect of various sale promotion strategies on consumer buying behavior. They used a sample of 297 by choosing customers at 25 supermarkets/hypermarkets in Pakistan. The study discovered that all of the promotional tools have important roles in motivating consumers. A study by Pallikkara et al. (Citation2021) was conducted in India’s leading food and grocery modern retail stores. A total of 385 respondents provided the data. During checkout, impulse purchases were found to be minimal. Some factors contribute to impulse buying at the checkout, including store environment, credit card accessibility, and promotions.

However, some promotions can have some disadvantages to public health. In other words, promotions affect shopping behavior even when they don’t involve healthy food. A study by Katt and Meixner (Citation2020) was conducted to determine what factors influence discount grocery shoppers’ purchase intentions for organic food. Organic food purchase intentions were negatively correlated with price consciousness. Moreover, Hoenink et al. (Citation2020) examined the efficiency of nudging and pricing strategies for increasing healthy food purchases. Information from a sample of 455 people was used. Their study suggested that combining both methods could be an effective tool to promote healthy food choices. An analysis of 50 weeks’ worth of beverage price promotions from two major Australian supermarket chains was conducted by Zorbas et al. (Citation2019). Prices for beverages are frequently promoted in Australian supermarkets, undermining dietary promotion efforts. These promotions are considered to have a negative impact on public health. More studies were conducted on food shoppers. Consumers at supermarkets were examined for their food purchasing behavior in a study by Sanlier and Karakus (Citation2010). In order to determine the criteria consumers considered when purchasing food, they conducted a survey. The researchers discovered that women put more importance on nutrition and reliability than men did. Roslan et al. (Citation2016) examined consumer decisions during food and grocery shopping. An empirical study of about 400 grocery shoppers was conducted. Among the demographic characteristics, only marital status influenced shopping decisions significantly.

There are indeed some recent studies in the GCC region about consumers’ behaviors. However, none of the research mentioned above investigated shopping behavior in the UAE, not before, not during, and not after COVID-19. The study by Joghee et al. (Citation2021) was about impulse buying. Moreover, the study by Bhalla and Bhalla (Citation2023) was about Carrefour in particular. However, our study is about shopping behavior in the UAE in general. Decision makers need to know which strategies to follow in the post-Covid-19 era to satisfy consumers’ needs. If not, customers might opt for online shopping or turn to competitors. Therefore, we need to bridge this gap.

3. Methodology

The study methodology starts with a literature review of factors affecting consumers’ behavior in general and in the GCC countries in particular. Recent studies during the pandemic and the political conflict took more attention. Then a gap was found in the UAE in which the authors work. The objectives of the study were set based on the gap and based on the recent challenges the retailers face. The method of data collection was chosen and the sampling method was determined. The method of data collection in this study is a survey because it helps get information from a large number of consumers. The study focuses on analyzing a questionnaire about the effect of pricing and other factors on shoppers’ behavior. The items in the questionnaire are based on a recent literature review. Three hypotheses were chosen to test. Data analysis methods that are appropriate for our study hypotheses were conducted using R, and findings were discussed.

The empirical data collected from different sectors of consumers give hypermarket decision-makers a clear vision of the most appropriate decisions to make. This data can be used to understand customer needs and preferences and adjust product offerings accordingly. The sampling technique used was random sampling. The questionnaire was sent online to about 300 people in the UAE. The number of respondents is 180, which is an acceptable number of respondents and accounts for 60% of the total number of people who received the questionnaire. According to Lund (Citation2023), the typical survey study received between 136 and 374 respondents, based on the survey sample sizes he examined in 842 articles about systems research. By avoiding non-response bias, we prevented survey participants from refusing or being unable to answer survey questions. Individuals have different reasons for not responding. Therefore, we kept our questionnaire short and simple. We also translated the questions into Arabic. Moreover, gentle reminders were sent to respondents.

A list of the different questions in includes the study’s constructs and their detailed dimensions. The short form in the second column will be used later in the results section. Constructs are groups of related dimensions. Each dimension represents a question in the questionnaire. The questionnaire is two parts: The first one is about information about the respondents such as age, education, gender, marital status, income, and frequency of shopping. The second part is about the 14 dimensions shown in . Respondents should answer the second part using a Likert scale of 1 to 5, where 5 means strongly agree, and 1 means strongly disagree. Therefore, the total number of questions in the questionnaire is 21.

Table 1. Study constructs and dimensions.

It is possible to have several malls and hypermarkets in a small region. Therefore, the dimensions 7 and 9 are not the same. The following hypotheses are investigated:

H1: There is a positive relationship between discounts and lower prices and the tendency of consumers to select the hypermarket and buy more.

H2: Other factors affect the buying behaviors of consumers such as quality of products, good location of hypermarket, and wide aisles.

H3: Several characteristics of consumers can affect their perception of buying behavior such as gender, marital status, age, education, income, and frequency of shopping.

shows the main framework of the study. The characteristics of the consumers are age, marital status, education, gender, number of shopping times in the week, and income. The other three factors affecting shopping behavior are related to the main constructs in .

To check these hypotheses, different tests are conducted. The first hypothesis can be examined using the one-sample t-test. For example, for the question ‘I look for products with lower prices’, the test will be if the average is larger than 3 or not. Being more than 3 means that most of the respondents provided the answer of agree or strongly agree. Some studies use ‘3’ and others use ‘3.5’. The second hypothesis can also be examined using the one-sample t-test. We also use 3 as the benchmark number. The third hypothesis needs two different tests. The first one is for gender and marital status, which needs the two-sample t-test. This is because we can classify respondents as males and females. Therefore, there are only two samples. Here, we do not have any number to test against. The effect of the rest of the factors needs to be checked using the Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) test. This is because they have more than two options. For example, age can be divided into five groups: Less than 25, between 25 and 34, between 35 and 44, between 45 and 54, and 55 or more. For all the different tests, we use p-values to check if the null hypothesis should be rejected or not. In other words, if the p-value is less than 0.05 for any one of the above hypotheses in the list, then that hypothesis is accepted. Before making these tests, the internal consistency needs to be checked first using Cronbach Alpha. For example, all the dimensions of the construct ‘The importance of prices’ are going in the same direction. Therefore, the value of Cronbach’s Alpha must be at least 0.6. We will also use the Spearman correlation coefficient to test the correlation of different types of questions. The coefficient can be from 0 to 1. The closer the correlation to 1, the stronger it is, and the closer to 0, the weaker it is.

4. Results

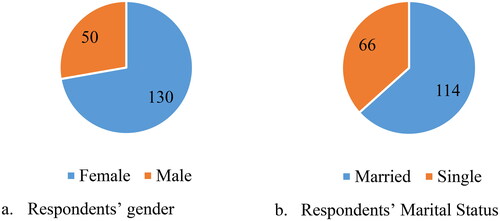

Information about the demographic profile of respondents and frequency of shopping is shown in and . shows pie charts representing the gender and marital status of respondents.

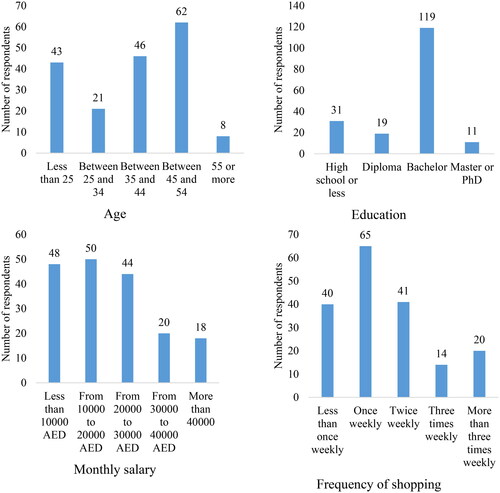

shows other data about the respondents, which are age education, frequency of shopping, and monthly salary. The respondents represent all the different types of consumers with different education levels, salaries, and ages. This is important to generalize the results of the study.

The Cronbach alpha values were given in . The first construct ‘Buying habits’ contains only two dimensions, and they are about two different things. Therefore, they are not included in . The results in are in the acceptable range.

Table 2. Cronbach Alpha of study construct.

shows the average, standard deviation, and one-sample t-test for the dimensions of the study. The hypothesis tested here is if the average of the responses is greater than 3 or not.

Table 3. Basic statistics and one sample t-test for study dimensions.

It is very clear from the p-values that they are less than .05, except for two dimensions. That reveals the importance of prices and other factors such as the quality of products, hypermarket layout, and hypermarket locations. However, consumers are not looking for goods at the end of the season. Only 25% of respondents buy cheaper goods at the end of the season. It is important for decision-makers to try to sell products at the right time. The last question about buying without considering prices reveals that most customers care about prices regardless of their income. However, 21% of the respondents answered with agree or strongly agree. The percentage of females who do not look at prices is 20% and the percentage of males is 24%. That means that men care more about prices than women do. From , and based on the average values, we can say that product quality is more important than prices. This is because the average value of dimension 11 is the maximum with a value of 4.23. The order of important factors based on respondents’ opinions is as follows: Low-priced products, the possibility of paying using the card, the way of writing prices, stable prices, not-crowded hypermarkets, the width of the aisles, and hypermarket location.

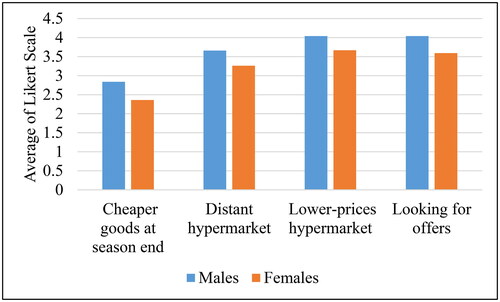

The two-sample t-test was used to examine the difference in the perspective of respondents based on gender. Only four dimensions showed differences between males and females. In this case, the p-values are less than .05. shows these dimensions. In all these dimensions, male averages are larger than female averages. This means that, for example, males are more likely to travel to distant hypermarkets seeking lower prices. Generally, males are more price-sensitive than females.

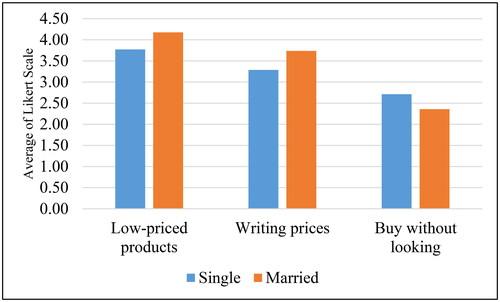

For marital status, it only affected three dimensions which were found with p-values less than .05. These three dimensions are shown in .

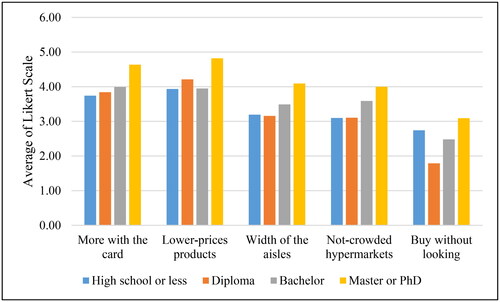

Married people care more about prices and the way they are written. This is expected because they have more responsibilities. For the effect of other variables, which are age, salary, education, and frequency of buying, the ANOVA test is used as shown in . Most of the p-values are larger than .05, indicating that these factors have a limited effect on respondents’ perceptions. Both age and frequency of buying do not have any effect on results. On the other hand, education has the largest effect on results.

Table 4. ANOVA test for the effect of age, salary, education, and frequency of buying.

shows the effect of education on the perceptions of respondents. It is clear that those with higher degrees (Master’s or Ph.D.) care about other factors such as buying more with cards, hypermarkets with wide aisles, and not being crowded. This is because higher educated people have larger salaries but less time to wait in cashier lines.

Spearman correlation was calculated for some of the constructs and the dimensions. shows the correlation between the three constructs. The correlation is significant between the first and the second constructs because both are about better prices.

Table 5. Correlation of constructs.

The dimension of travelling to distant hypermarkets looking for better prices is a good example of showing the priorities of different people. The correlation between this dimension and some others is shown in . It is very clear that those consumers, who are willing to drive to distant hypermarkets looking for better prices, place less importance on finding hypermarkets with stable prices and high-quality products.

Table 6. Correlation between the dimension of ‘Distant hypermarket’ and some others.

5. Analysis

This study analyzes the effect of hypermarket pricing strategies on consumers’ shopping behavior. It also shows that other factors such as product quality, not crowded hypermarkets, and locations are also important. The study shows that product quality is more important than prices. The least important factor is the location of the hypermarket. This is because the UAE is an oil-exporting country, and fuel prices in the UAE are generally lower than fuel prices in other countries. The study shows that there are differences in the perception of respondents based on gender, marital status, and education. For example, well-educated people tend to prefer not crowded hypermarkets. The effects of other factors such as age, frequency of shopping, and salary are almost negligible. These results are important for decision-makers to decide which strategies to take into consideration. This study has managerial implications. Retailers must pay more attention to product quality. Discounts need to be done frequently to attract more consumers. Making price reductions at the end of the season is usually not so useful. However, men showed more interest than women in such end-of-season sales. Therefore, retailers can concentrate on discounts on products needed by them. Furthermore, Retailers need to be aware of changing customer preferences and stay competitive. If a hypermarket is not in the center of the city, more price reductions are required to attract consumers from relatively distant regions. Changes in the layout and allocation of different items, when demand changes over the year, are also needed. Because married males care more about prices than other consumers do, products such as baby toys, children’s clothes, and hygiene products should be offered at reasonable prices. Not only are discounts important, but the way they are written is also important. Therefore, appropriate banners are a wise choice. On the national level, the UAE had price inflation recently, but it was not as high as in many other countries. This is important to keeping the economy running.

The results generally agree with the main findings of the literature (Cakici & Tekeli, Citation2022; Fikri et al., Citation2020), with some exceptions, based on the UAE condition. For example, according to Roslan et al. (Citation2016), only marital status has an effect on the perception of respondents. On the other hand, Hernández et al. (Citation2011) found that age, gender, and income have no effect on buying behavior. In our study, age and income have almost no effect on the results. However, gender affects the results of our study. The study also aligns with what was found in the literature about buying more goods with a card than with cash. This is such as the results in the study by Greenacre and Akbar (Citation2019). Our study also agrees with the findings of Rahman (Citation2023) about the effect of pricing and location on consumers’ shopping behavior. It also agrees with the effect of gender on the perception of respondents. However, Rahman (Citation2023) found that age affected the perception of respondents. This, however, is not the case in our research; age has no effect at all. The study agrees with Isabella et al. (Citation2012) about the importance of the way of writing discounts and how it can attract the attention of consumers. However, there were no previous studies in the UAE about consumers’ preferences before Covid-19 to compare our study with.

6. Conclusion

This study examines the positive effect of effective pricing strategy, way of writing prices, quality of products, near hypermarkets, wide-aisle hypermarkets, and not-crowded hypermarkets on consumers’ choices. Statistical methods of a survey in the UAE were utilized to achieve the study objectives. Results showed that consumers give more weight to quality than cheap prices. Factors such as marital status, gender, and education affect the results. Males and married people generally care more about better prices than females and single people. Highly educated people value product quality, calm, and convenient shopping environments. The study is the first of a kind in the UAE. It provides retailers with valuable insights about the importance of price reduction, product quality, facility location and layout, and others. For example, retailers can concentrate on a segment of consumers interested in discounts such as married men. However, the study has some limitations. For example, even though the sample size of 180 respondents is reasonable, larger samples can be better to represent more respondents. Further research is still needed on the most effective ways to utilize the results of this study. This research is needed to translate its findings into strategies for selecting the most suitable location, design, and supply chain options for hypermarkets. Additionally, research should focus on how to improve customer satisfaction at a specific hypermarket. Understanding customer needs and preferences is essential for the success of any business, particularly in the retail industry. The current study investigated consumers’ perceptions. There is a need for additional research into the perception of hypermarket management staff. Empirical studies are needed to track the changes and actions taken by these hypermarkets to cope with consumer perception changes.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Mohammed Alnahhal

Mohammed Alnahhal holds a PhD degree from Germany. He is working at the American University of Ras Al Khaimah. His research includes supply chain management, Simulation, Operations Research, data analysis, and Project Management.

Easa Aldhuhoori

Easa Aldhuhoori has just finished his bachelor degree of industrial engineering from the American University of Ras Al Khaimah.

Mohammad Ahmad Al-Omari

Mohammad Ahmad Al-omari is working as Assistant Professor at the College of Business, Al Ain University, UAE. He has published many papers in journals of repute.

Mosab I. Tabash

Mosab I. Tabash is currently working as MBA Director at the College of Business, Al Ain University, UAE. His research interests include Islamic banking, monetary policies, financial performance, and investments.

References

- Al-Salamin, H., & Al-Hassan, E. (2016). The Impact of pricing on consumer buying behavior in Saudi Arabia : Al-Hassa case study. European Journal of Business and Management, 8(12), 1–13. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301753990

- Bashir, H., Alsyouf, I., Shamsuzzaman, M., & Haridy, S. (2020). Lean warehousing: A case study in a retail hypermarket. Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management (pp. 1599–1607). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344332359

- Belwal, R., & Belwal, S. (2014). Hypermarkets in Oman: A study of consumers’ shopping preferences. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 42(8), 717–732. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-02-2013-0043

- Belwal, R., & Belwal, S. (2017). Factors affecting store image and the choice of hypermarkets in Oman. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 45(6), 587–607. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-06-2015-0086

- Bhakat, R. S., & Muruganantham, G. (2013). A review of impulse buying behavior. International Journal of Marketing Studies, 5(3), 149–160. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijms.v5n3p149

- Bhalla, R., & Bhalla, V. (2023). A study on key retailing strategies of Carrefour and its intervention plan during the pandemic (Covid-19): UAE. European Journal of Marketing and Economics, 6(1), 123–138. https://doi.org/10.2478/ejme-2023-0010

- Cakici, A. C., & Tekeli, S. (2022). The mediating effect of consumers’ price level perception and emotions towards supermarkets. European Journal of Management and Business Economics, 31(1), 57–76. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJMBE-12-2020-0344

- De, A., & Singh, S. P. (2023). A resilient pricing and service quality level decision for fresh agri-product supply chain in post-COVID-19 era. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 34(4), 1101–1140. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLM-02-2021-0117

- Díaz-Martín, A. M., Quinones, M., & Cruz-Roche, I. (2021). The post-COVID-19 shopping experience. In Thoughts on the role of emerging retail technologies (vol. 205, pp. 55–67). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-33-4183-8_6

- El-Adly, M. I., & Eid, R. (2016). An empirical study of the relationship between shopping environment, customer perceived value, satisfaction, and loyalty in the UAE malls context. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 31, 217–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2016.04.002

- Fares, N., Lloret, J., Kumar, V., Frederico, G. F., Kumar, A., & Garza-Reyes, J. A. (2023). Enablers of post-COVID-19 customer demand resilience: evidence for fast-fashion MSMEs. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 30(6), 2012–2039. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-11-2021-0693

- Fikri, M. E., Andika, R., Febrina, T., Pramono, C., & Pane, D. N. (2020). Strategy to enhance purchase decisions through promotions and shopping lifestyles to supermarkets during the coronavirus pandemic: A case study IJT Mart, Deli Serdang Regency, North Sumatera. Saudi Journal of Business and Management Studies, 5(11), 530–538. https://doi.org/10.36348/sjbms.2020.v05i11.002

- Gaytan, J., Sakkthivel, A., Desai, S., & Ahmed, G. (2020). Impact of internal and external promotional variables on consumer buying behavior in emerging economy – An empirical study. Skyline Business Journal, 16(1), 45–54. https://doi.org/10.37383/SBJ160104

- Ghaffarkadhim, K., Harun, A., & Othman, B. A. (2019). Hypermarkets in Malaysia: Issues of expansion, distribution and corporate social responsibility. International Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation, 23(2), 659–670.

- Greenacre, L., & Akbar, S. (2019). The impact of payment method on shopping behaviour among low income consumers. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 47, 87–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2018.11.004

- Hallikainen, H., Luongo, M., Dhir, A., & Laukkanen, T. (2022). Consequences of personalized product recommendations and price promotions in online grocery shopping. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 69, 103088. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2022.103088

- Hernández, B., Jiménez, J., & Martín, M. J. (2011). Age, gender and income: Do they really moderate online shopping behaviour? Online Information Review, 35(1), 113–133. https://doi.org/10.1108/14684521111113614

- Higueras-Castillo, E., Liébana-Cabanillas, F. J., & Villarejo-Ramos, Á. F. (2023). Intention to use e-commerce vs physical shopping. Difference between consumers in the post-COVID era. Journal of Business Research, 157, 113622. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.113622

- Hoenink, J. C., Mackenbach, J. D., Waterlander, W., Lakerveld, J., Van Der Laan, N., & Beulens, J. W. J. (2020). The effects of nudging and pricing on healthy food purchasing behavior in a virtual supermarket setting: A randomized experiment. The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 17(1), 98. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-020-01005-7

- Isabella, G., Pozzani, A. I., Chen, V. A., & Gomes, M. B. P. (2012). Influence of discount price announcements on consumer’s behavior. Revista de Administração de Empresas, 52(6), 657–671. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0034-75902012000600007

- Joghee, S., Al Kurdi, B., Alshurideh, M., Alzoubi, H., Vij, A., Muthusamy, M., & Hamadneh, S. (2021). Expats impulse buying behaviour in UAE: A customer perspective. Journal of Management Information and Decision Sciences, 24(1), 1–24.

- Katt, F., & Meixner, O. (2020). Is it all about the price? An analysis of the purchase intention for organic food in a discount setting by means of structural equation modeling. Foods, 9(4), 458. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9040458

- Khan, M., Tanveer, A., & SohaibZubair, S. (2019). Impact of sales promotion on consumer buying behavior: A case of modern trade, Pakistan. Governance and Management Review, 4(1), 38–53.

- Kurniawan, A. N., Rifai, A. I., & Rizal, M. (2022). Phenomena of transportation to work mode choice, due to the increase of oil prices in Indonesia: A case light rail transit depot project office-Jakarta. Citizen, 2(5), 785–793. https://doi.org/10.53866/jimi.v2i5.193

- Lund, B. (2023). The questionnaire method in systems research: An overview of sample sizes, response rates and statistical approaches utilized in studies. VINE Journal of Information and Knowledge Management Systems, 53(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1108/VJIKMS-08-2020-0156

- Maulana, A., & M., Novalia, N. (2019). The effect of shopping life style and positive emotion on buying impulse (case study of the Palembang City Hypermarket). Information Management and Business Review, 11(1), 17–23. https://doi.org/10.22610/imbr.v11i1.2844

- McColl, R., Macgilchrist, R., & Rafiq, S. (2020). Estimating cannibalization effects from sales promotions: the impact of price cuts and store type. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 53, 101982. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.101982

- Naeem, M. (2020). Understanding the customer psychology of impulse buying during COVID-19 pandemic: implications for retailers. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 49(3), 377–393. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-08-2020-0317

- Noor, Z. Z. (2020). The effect of price discount and in-store display on impulse buying. Sosiohumaniora, 22(2), 133–139. https://doi.org/10.24198/sosiohumaniora.v22i2.26720

- Pallikkara, V., Pinto, P., Hawaldar, I. T., & Pinto, S. (2021). Impulse buying behaviour at the retail checkout: An investigation of select antecedents. Business: Theory and Practice, 22(1), 69–79. https://doi.org/10.3846/btp.2021.12711

- Rahman, M. N. (2023). Analytical study of correlation between retail store image and shopping behaviour of Saudi Arabian consumers. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues, 10(3), 123–132. https://doi.org/10.9770/jesi.2023.10.3(9)

- Roslan, A. R., Jani, R., & Fauzi, R. (2016). Understanding consumer decision during shopping food and grocery in hypermarket: Demographic and trip characteristic. Scholars Bulletin, 2(1), 43–51. http://scholarsbulletin.com/

- Sandybayev, A. (2019). How Carrefour revolutionizing supply chain management: Case from the United Arab Emirates. International Journal of Afro-Eurasian Research, 4(7), 210–220.

- Sanlier, N., & Karakus, S. S. (2010). Evaluation of food purchasing behaviour of consumers from supermarkets. British Food Journal, 112(2), 140–150. https://doi.org/10.1108/00070701011018824

- Sharma, V., & Sonwalkar, J. (2013). Does consumer buying behavior change during economic crisis? International Journal of Economics and Business Administration, 1(2), 33–48. https://doi.org/10.35808/ijeba/9

- Wang, Y., Xu, R., Schwartz, M., Ghosh, D., & Chen, X. (2020). COVID-19 and retail grocery management: Insights from a broad-based consumer survey. IEEE Engineering Management Review, 48(3), 202–211. https://doi.org/10.1109/EMR.2020.3011054

- Zhou, L., & Wong, A. (2004). Consumer impulse buying and in-store stimuli in Chinese supermarkets. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 16(2), 37–53. https://doi.org/10.1300/J046v16n02_03

- Zorbas, C., Gilham, B., Boelsen-Robinson, T., Blake, M. R. C., Peeters, A., Cameron, A. J., Wu, J. H. Y., & Backholer, K. (2019). The frequency and magnitude of price-promoted beverages available for sale in Australian supermarkets. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 43(4), 346–351. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.12899