?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Traditional financial performance metrics have served well throughout the inclusion era, but they are no longer in sync with the skills and competitiveness that organizations are attempting to learn. This study examined the role of intellectual capital disclosure (ICD) in mediating the relationship between financial performance and firm value. The sample consists of 39 firms listed on the Nairobi Securities Exchange (NSE) in Kenya. They represent 67% of firms listed on NSE during the period (2010–2022). Data were extracted from individual companies’ audited annual reports. The study hypotheses were tested on a fixed and random effects model with the aid of the Stata student version. The results reveal that financial performance has a positive and significant effect on firm value. Furthermore, financial performance has a negative effect on ICD. Finally, ICD was found to have a mediating effect on the relationship between financial performance and firm value. The results confirm that intellectual capital disclosure is an important mediator in the relationship between financial performance and firm value; firm managers should use ICD as a winning edge. Additionally, firms with high intellectual capital are likely to engage in voluntary disclosure to legitimize their success.

IMPACT STATEMENT

The study examine whether or not listed companies’ disclosure of intellectual capital is value-relevant in share markets? The difference between a high-, average-, or mediocre-valued firm is not a huge difference in the ability of the CEO, but a few small things done consistently and repeatedly, such as the presentation of intangible assets in financial reports. Thus, organizations disclose intellectual capital to legitimize their success away from the traditional symbol of firm success based on tangible resources.

JEL CLASSIFICATION:

1. Introduction

High firm value is attributed to organizational financial performance as post operation information content, which acts as a signal to investors regarding future prospects. Financial performance serves as a signal to investors on firm ability to use its resources to generate more revenue and manages its assets, liabilities, and the financial interests of its stakeholders and stockholders. There is empirical evidence that organization investments in intangibles such as employee knowledge or brands are economically beneficial to firms (Corrado et al., Citation2022; Fraser & Monteiro, Citation2009; Heiens et al., Citation2007; Kamasak, Citation2017) and economies in general (Edquist, Citation2011). Often, the intangibles are summarized as intellectual capital (IC) (Bellucci et al., Citation2021; Keong Choong, Citation2008; Qureshi & Siddiqui, Citation2021). Intellectual capital disclosure is regarded as ‘good news’ by capital markets and restrictive disclosure as ‘bad news’. Voluntary intellectual capital disclosure (ICD) can lead to a favorable reassessment of the firm and attract new investors by signaling attractive investment opportunities. Hence, intellectual capital disclosure is value relevant as it reduces information asymmetry which in turn increases equity value as it is argued from agency theory and signaling theory. Despite the increase in relevance, accounting regulations have been reluctant in capitalizing intellectual capital as a value relevance of accounting information for investors (Rieg & Vanini, Citation2023; Ciftci et al., Citation2014; Hail, Citation2013; Basu & Waymire, Citation2008). It has also been established that the significant difference between market and book value is caused by the intangible assets often undisclosed under traditional financial reporting (Dashti, Citation2016; Brand Finance Institute, Citation2017)

Consequently, firm investment decisions are concerned with enhancing firm’s value (Suteja et al., Citation2023: Suteja et al., Citation2016). Previous studies have attributed high firm valuations to increase in stock price, through profit maximization (Gharaibeh & Qader, Citation2017; Ilmi et al., Citation2017; Jallo & Mus, Citation2017; Sucuahi & Carbarihan, Citation2016; Yanto, Citation2018). Thus, there is a growing recognition that financial performance is one of the most important factors in determining corporate value (Ghosh & Ghosh, Citation2008; Abdi et al., Citation2022b; Dewi & Maulana, Citation2022; Sari & Sedana, Citation2020; Purbawangsa et al., Citation2020). Studies have established a positive relationship between financial performance affect firm value positively (Firdaus et al., Citation2018; Gharaibeh & Qader, Citation2017; Husna & Satria, Citation2019; Ilmi et al., Citation2017; Jallo & Mus, Citation2017; Sucuahi & Carbarihan, 2016; Yanto, Citation2018). However, Pascareno and Siringoringo (2016) and Luqman Hakim and Sugianto (Citation2018), established that financial performance had no effect on firm value. Considering that contradictory results still exist between financial performance and firm value, there are other factors/variables that have a contingent effect on firm value. Therefore, we add intellectual capital disclosure as a mediating variable.

Intellectual capital disclosure is valuable since it affects investor’s behaviors in their decision-making (Alfraih, Citation2017; Anifowose et al., Citation2016–Citation2017; Dashti, Citation2016; Ferchichi & Paturel, Citation2013; Salehi et al., Citation2014; Williams, Citation2001). Signaling theory propose the when a firm signals its potentials to the market, investors will re-evaluate and [hence] make a more favorable decision on its value (Whiting & Miller, Citation2008). The era of knowledge-based economy acknowledge-based economy acknowledge firms intellectual capital as the essential foundation for firms‟ future success (Williams, Citation2001), which is used to create and apply knowledge within the firms, thereby enhancing their value (Cabrita & Vaz, Citation2006). Given that a firm’s intellectual capital determines its future wealth creation, its [voluntary] disclosure in the annual report communicates the firm’s superior value to the capital market (Whiting & Miller, Citation2008; Haji & Anifowose et al., Citation2017). Information disclosure required by stakeholders is expected to increase firm value. According to a study by Jihene (Citation2013) on the influence of intellectual capital on firm value among 50 companies registered on the Tunisian Stock Exchange in 2006–2009, it was established that intellectual capital disclosure has a positive effect on firm value. Additionally, Orens et al. (Citation2009) established similar results, that intellectual capital disclosure has a positive effect on firm value.

In line with this, previously, studies have found conflicting results pertaining to financial performance, intellectual capital disclosure and firm value nexus. In line with this, studies have established that financial performance have impact on intellectual capital disclosure (Mamun & Aktar, Citation2020; Rahim et al., Citation2011; Tran & Vo, Citation2020). Ousama et al. (Citation2012), Suhardjanto and Wardhani, (Citation2010) showed that profitability had a positive and significant effect on intellectual capital disclosure. However, Ferreira et al. (Citation2012), Ibikunle and Damagum (Citation2013), and Kateb (Citation2015) established that profitability has no effect on intellectual capital disclosure. Consequently, a negative relationship between organizational performance and intellectual capital disclosure has been established (Mawardi et al., Citation2020; Ramadan and Majdalany (Citation2013). Mixed findings were also established on the relationship between financial performance and firm value (Gharaibeh & Qader, Citation2017; Ilmi et al., Citation2017; Jallo & Mus, Citation2017). While, Pascareno and Siringoringo (Citation2016) and Luqman Hakim and Sugianto (Citation2018) firm financial performance does not affect firm value. Regarding the empirical evidence of intellectual capital disclosure on firm value is limited in certain industries (Soukhakian & Khodakarami, Citation2019).

Hence, intellectual capital has a positive effect on firm value (Bayraktaroglu et al., Citation2019; Wang, Citation2008). While, Yamola et al. (Citation2013), intellectual capital has a negative effect on value creation. Therefore the study sought to establish the effects of financial performance, intellectual capital disclosure, and firm value from the perspective of signaling theory. In line with this, higher performance is a signal to investors because it contributes to a better reputation. Therefore, high firm value is attributed to organizational financial performance, which acts as a signal to investors regarding future prospects. This position is supported by the signaling theory. Hence, high financial performance serves as a signal to investors on firm ability to use its resources to generate more revenue and manages its assets, liabilities, and the financial interests of its stakeholders and stockholders. Consequently, intellectual capital disclosure is expected to affect the relationship between financial performance and firm value. Also, signaling theory states that intellectual capital disclosure is regarded as ‘good news’ by capital markets. Therefore, ICD can lead to a favorable reassessment of the firm and attract new investors by signaling attractive investment opportunities.

According to the agency theory high performance makes it easier for managers to persuade shareholders that their managerial abilities are superior. Therefore, high financial performance serves as a signal to investors on firm ability to use its resources to generate more revenue and manages its assets, liabilities, and the financial interests of its stakeholders and stockholders. This position is supported by the signaling theory, which echoes that the selected signal must contain the power of information (information content) to be able to change the assessment of the company’s external parties. Based on this discussion, this study sought to examine and analyze: [1] the effect of financial performance on intellectual capital disclosure. [2] The effect of financial performance on firm value. [3] Intellectual capital disclosure on firm value. [4] Mediating effect of intellectual capital disclosure on the relationship between financial performance and firm value.

2. Background of the study

The difference between market and book value is the portion of intangible assets often undisclosed under traditional financial reporting (Brennan & Connell, Citation2000; Hulten & Hao, Citation2008; Iranmahd et al., Citation2014; Rieg & Vanini, Citation2015; Ferchichi & Paturel, Citation2013; Boujelbene & Affes, Citation2013; Anifowose et al. Citation2016–2017; Dashti, Citation2016; Brand Finance Institute, Citation2017). To achieve high valuation, firms must increase stock price, through profit maximization. Previous research has investigated the effect of financial performance on firm value and financial performance on intellectual capital disclosure. Independently, the current study links the three variables financial performance, intellectual capital disclosure, and firm value as an integrated research framework comprised of the three focal issues, with intellectual capital disclosure acting as mediating variables. The study bridges the gap by investigating the impact of firms’ disclosure of intangible information on reducing information asymmetry and lowering the cost of capital, resulting in increased firm value. Therefore, the main objective of firm is profit maximization, while the ultimate goal is to enhance business value. To achieve the goals, firms need additional capital to enhance their operations. The additional capital is normally obtained from investors outside the company.

Sourcing additional funds from the capital market enables firms to reduce risk and expenses in acquiring financial capital, since they have reliable markets where they obtain funding. Generally, the capital markets allow traders and investors to buy and sell stocks and bonds, and business to raise the financial capital to grow. However, when the potential investors invest in a company, they always require information regarding to how well the company has been managed. Financial reporting is crucial for companies’ investors, as it provides Key information that shows financial performance over time. Hence, it is necessary to ensure that companies engage in fair trade, especially when it comes to financial reporting, to ensure that investors are not misled. Through the capital market authority (CMA), the Kenyan government, in partnership with private regulatory institutions, can monitor and ensure fair trade, compensation, and financial activities (Mwangi, Citation2016). Generally, the external challenges facing the Nairobi Security Exchange; Political instability, and intolerance have reduced investor confidence. The study examines the implications of financial performance on intellectual capital disclosure and firm value between 2010 and 2022 post-election violence, and how firm performance impacts firm value. The post-election chaos resulted from the 2007 to 2008 election affected nearly all sectors of the economy. For instance, in 2007, foreign direct investment (FDI) was $729 m and dropped by almost 75% to $183 m in 2008 as a result of election violence (KRA, Financial report 2009/2010). Currently, foreign direct investment (FDI) increased by $ 394 m in December 2022 (KRA, Financial report 2021/2022), indicating that the economy is growing as a result of easing political tensions. Addition during the period the COVID 19 pandemic has caused a considerable amount of damage to every facet of life, including financial markets (Baker et al., Citation2020).

Hence, it is necessary to ensure that companies engage in fair trade, especially when it comes to financial reporting, to ensure that investors are not misled. Through the capital market authority (CMA), the Kenyan government, in partnership with private regulatory institutions, can monitor and ensure fair trade, compensation, and financial activities (Mwangi, Citation2016). Generally, the external challenges facing the Nairobi Security Exchange; Political instability, and intolerance have reduced investor confidence. Previous studies have established a positive and significant effect of political tensions on firm performance (Kithinji & Ngugi, Citation2005; Menge, Citation2013). Similarly, Irungu (Citation2012) finds a negative relationship. Hence, with the current political stability, we expect that stock prices will be high, hence high firm value as a result of better performance. However, managerial incentives differ depending on whether managers are assumed to act opportunistically or to provide information relevant to discretionary disclosure. Additionally, the majority of problems experienced by firms in developing countries are mainly attributed to poor governance, leading to a loss of investor confidence in the stock market. Generally, shareholders’ well-being is demonstrated by the market price per share of the company, which also reflects funding, asset management, and investment decisions (Awais et al., Citation2016). Investors will react differently to information available in the market, which is as a result of rational and irrational investor behavior. The credibility of the information disclosed adds to the value of the enterprise, as the details are released to assist in reducing the risk associated with an investor’s decision-making process. Lack of intellectual capital disclosure reporting is a risk that intellectual capital does not receive sufficient attention from management and other stakeholders (Petty & Guthrie, Citation2000), thereby diluting firm value. Failure to disclose important intellectual capital information can lead to low valuation in the capital market (Mubarak & Mousa Hamdan, Citation2016).

Consequently, companies must report more intellectual capital disclosures to enhance firm value. According to Sheu et al. (Citation2010), the market rewards corporations that choose to disclose full details with higher valuation. Furthermore, the level of organizational disclosure has a significant effect on firm value (Anam et al., Citation2011; Dhaliwal et al., Citation2011; Garay et al., Citation2013). Given the inconclusive empirical results on financial, we attribute firms with high valuations to small differences in the ability of CEOs, which could lead to enormous differences in the results. The difference between a high-, average-, or mediocre-valued firm is not a huge difference in the ability of the CEO, but a few small things done consistently and repeatedly, such as the presentation of intangible assets in financial reports.

3. Theoretical literature review

The study is underpinned by signaling theory, agency theory, and legitimacy theories. Agency theory explains the connection between the agent and the principal. Hence, the principal (management) is responsible for completing the principal (stakeholder) task (Fama & Jensen, Citation1983). Michael Spence developed the signaling theory in 1978 to form signal models in the work environment between employees and the employer. Hence, signaling theory explains the importance of one party disclosing some information to another party to provide positive signals about itself. The legitimacy theory, on the other hand, describes the generalized perception that the actions of an entity are desirable or appropriate within a socially constructed system of norms, values, and beliefs (Suchman, Citation1995). The agency theory argues that firm value cannot be maximized if appropriate incentives or adequate monitoring are not effective enough to restrain firm managers from using their own discretion to maximize their own benefits. Therefore, agency problems arise from information asymmetry; hence, management seeks to reduce information asymmetry to lower agency costs (Donnelly & Mulcahy, Citation2008).

Agency theory proposes that organizations should be motivated to provide more information and voluntary disclosures to reduce information asymmetry and eventually agency costs (Omran & El-Galfy, Citation2014). The information asymmetry between the principal and agent has long been a concern in many studies (Spence, Citation2002; Gul & Leung, Citation2004; Zaigham et al., Citation2019), which explains that the information gap between the principal and agent can be reduced if the party with information can send a signal to a related party with no information. From agency theory perspective, companies (management) are motivated to disclose more intellectual capital to convince stakeholders that they are behaving optimally on stakeholder’s behalf as a result reduces agency cost/conflicts (Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976; Vitolla et al., Citation2020). Similarly, the value of the firm is reflected in terms of stock prices, which are economic consequences of business activities in the market. Hence, signaling theory posits that investors rely on information delivered by firms (Abhayawansa & Abeysekera, Citation2009; Vanini & Rieg, Citation2019). Signaling theory has been applied in events of information asymmetry where outsiders usually do not have access to the internal information regarding the company that is only available to the managers. In line with this disclosure can curtail agency problem by decreasing information asymmetry, and thus enhancing firm value. Hence, CEOs and managers disclose information regarding financial performance and intellectual capital to signal that the company will have better prospects in the future.

Therefore, high profitability signals to investors that the firm has the potential to perform better in the future. Similarly, legitimacy theory asserts that organizations operate in a continuously changing environment and always attempt to pursue a society in which their activities are within set standards (Brown & Deegan, Citation1998). Organizations present annual reports to legitimize the operations and activities of corporations. Hence, intellectual capital disclosure is applied as an explanatory framework to analyze firms facing legitimacy as a result of high and unjustified profits. Essentially, agency theory considers CEOs or managers to use impression management (opportunistic behavior) to select a style of presentation and choice of content to be reported, as it will be beneficial to them and provide information relevant to discretionary disclosure (Clatworthy & Jones, Citation2006; Heider, Citation1958; Kelley, Citation1967). Hence, CEOs disclose more intellectual capital with opportunistic behaviors to justify themselves. Additionally, management might also report high performance by deferring some expenses to signal better prospects in the future. The overall goal of an organization is to provide useful information to stakeholders. From the legitimacy theory perspective, organizations take actions to guarantee that their operations are viewed as legitimate as part of a social contract. Therefore, organizations with high levels of intellectual capital will engage in voluntary disclosure since they cannot legitimize their status through the traditional symbols of corporate success using tangible assets (Guthrie et al., Citation2004; Olateju et al., Citation2021).

3.1. Conceptual framework

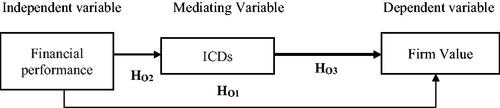

represents the mediating effect of intellectual capital disclosure on the relationship between financial performance and the value of firms listed on the Nairobi Security Exchange. The independent variable in this study was financial performance. The mediating variable is intellectual capital disclosure (ICD) and the dependent variable is firm value, as illustrated in .

4. Empirical literature review and hypotheses development

4.1. Financial performance and firm value

Financial performance is a periodic determination of an organization’s operational effectiveness. Generally, financial performance has been considered a prospect for future growth and potentially good development for the company (Barlian, Citation2003; Hasanudin et al., Citation2020). Firm value is an indication of management effectiveness and efficiency in managing organization resources (Husnan & Enny, Citation2006; Wijaya & Sedana, Citation2020). Therefore, company performance is significantly associated to firm value (Chen & Chen, Citation2011; Hassan & Halbouni, Citation2013; Ketut, Citation2016; Muliani et al., Citation2014). This position is supported by the signaling theory. Therefore, financial performance serves as a signal to investors on firm ability to use its resources to generate more revenue and manages its assets, liabilities, and the financial interests of its stakeholders and stockholders. According to Chen and Chen (Citation2011) established that financial performance influenced the value of green energy companies in China for a period of (2008–2017).

Similarly, Muliani et al. (Citation2014), Ketut (Citation2016), and Kevin and Omagwa (Citation2017) find that profitability (ROA) influences company value. Consequently, Luthfiah and Suherman (Citation2018), Murpradana (Citation2015), Rosikah et al. (Citation2018), and Sudiyatno et al. (Citation2020) found that return on assets has a positive significant effect on firm value. Hence, a better financial performance, implies theoretically means a good ROA value, will increase stock price and finally increase firm value. However, Sigit Hermawan, (Citation2014) established that organizational profitability does not influence firm value. Handley and Li (Citation2018) and Karima (Citation2016) established that there is no relationship between financial performance and firm value. The inconsistency in the results is attributed to measurement faults of indicators based on accounting data that are historical and do not consider expected cash flows in the future. Hence, there is a need to re-examine the effect of financial performance on firm value by first ensuring the most appropriate financial performance measurement model and whether better financial performance contributes to a positive reputation as it sends signal asymmetry.

H01 Financial performance has a positive and significant effect on firm value.

4.2. Financial performance and intellectual capital disclosure

A company’s success is generally measured by its financial performance: companies with higher earnings are more vulnerable to regulations that require more detailed information to be disclosed in annual reports to justify financial performance (Mondal & Ghosh, Citation2014). Therefore, disclosure level can be used to differentiate firms’ profitability. According to Purnomosidhi (Citation2005), an organization’s financial performance is an indicator used to differentiate between companies with high and low voluntary disclosure. Essentially, the level of disclosure is positively associated with an organization’s profitability (Williams, Citation2001). Similarly, good financial positions intensify the credibility of an organization’s information (Scott, Citation1994). Two theoretical perspectives justify the relationship between financial performance and firm value. From an agency theory perspective, high financial performance makes it easier for managers to persuade shareholders that their managerial abilities are superior. Firms use voluntary disclosure to gain investor trust. Second, signaling theory attributes highly profitable companies to the benefit of signaling that they are better in the industry.

Therefore, profitable companies have a greater incentive to disclose more information regarding intellectual capital disclosure. Organizational profitability enhances intellectual capital disclosure (Ousama et al., Citation2012). Additionally, companies that report higher earnings are subject to more rules that require them to provide additional information to justify their high performance (Mondal & Ghosh, Citation2014). Firms’ willingness to disclose more voluntary information (intellectual capital) is attributed to high financial performance (Hamrouni et al., Citation2015). According to Rahim et al. (Citation2011), profitability influences intellectual capital disclosures. Similarly, Ousama et al. (Citation2012) and Suhardjanto and Wardhani (Citation2010) attribute intellectual capital disclosure to high financial performance. However, (Ferreira et al., Citation2012; Ibikunle & Damagum, Citation2013; Kateb, Citation2015) demonstrate that profitability does not affect intellectual capital disclosure. Moreover, Ramadan and Majdalany (Citation2013) established a negative and significant relationship between financial performance and intellectual capital disclosure. The inconsistent results from previous studies have necessitated the need to re-examine the effect of financial performance on intellectual capital disclosure by first ensuring the most appropriate intellectual capital disclosure.

H02 Financial performance has a positive and significant effect on intellectual capital disclosure.

4.3. Intellectual capital disclosure and firm value

Intellectual capital is widely recognized as an important resource for creating value (Mention & Bontis, Citation2013). Intellectual capital disclosure is designed to meet stakeholders’ information needs of the stakeholders about intellectual capital (Musfiqur et al., Citation2019). Generally, the disclosure of intangible assets assists stakeholders in understanding managers’ perspectives, as well as the source and development of intellectual capital among the firm’s current and future achievements (McCracken et al., Citation2018). Generally, the disclosure of intellectual capital enhances transparency and increases faith among stakeholders (Taliyang & Jusop, Citation2011). According to Vanini and Rieg (Citation2019) numerous studies have analyzed the value relevance of voluntary intellectual capital disclosure (ICD). In addition, other studies have used intellectual capital disclosure for valuation (Flöstrand & Ström, Citation2006; Petty et al., Citation2008). Thus, voluntary ICD have been established to reduce analysts’ forecast errors (Hsu & Sabherwal, Citation2011; Maaloul et al., Citation2016). Therefore analysts will give favorable recommendations when they are informed better about firms intellectual capital disclosure (Farooq & Nielsen, Citation2014; Maaloul et al., Citation2016).

Intellectual capital disclosures (ICD) reduce information asymmetries between a firm’s management and its investors (Anifowose et al., Citation2017; Orens et al., Citation2010). Previous studies have established a positive and significant effect of the organizational disclosure level on firm value (Anam et al., Citation2011; Garay et al., Citation2013; Gordon et al., Citation2010). Generally, an increase in the level of disclosure is associated with a reduction in mispricing, cumulative profitability and enhanced firm value (Botosan & Plumlee, Citation2002). ICD is regarded as ‘good news’ by capital markets and restrictive disclosure as ‘bad news’ because it is assumed that firms only disclose information voluntarily if this information is positive. Thus, favorable assessment of the firm and attracting new attract new investors by signaling investment opportunities (Castilla-Polo & Gallardo-Vázquez, Citation2016; Healy & Palepu, Citation2001). Thus, intellectual capital disclosure is expected to positively influence firm value as it reduces information asymmetry which in turn increases equity value as it is argued from agency theory and signaling theory.

However, the direction and magnitude of the relationship between intellectual disclosure and firm value vary depending on the type of disclosure (Hassan et al., Citation2009) and proxy used for firm value (Uyar & Kılıç, Citation2012). This study sought to establish the effect of intellectual capital disclosure on firm value in the context of the Nairobi Security Exchange in Kenya across all sectors. Considering that previous studies looked at the relationship between intellectual capital disclosure and firm value in specific sectors (Pratama et al., Citation2019). As a result, it is necessary to determine whether intellectual capital disclosure has an impact on firm value. Therefore, there is a need to establish a relationship between intellectual capital disclosure and firm value.

H03 Intellectual capital disclosure has a positive and significant effect on firm value.

4.4. Mediating effect of intellectual capital disclosure on the relationship between financial performance and firm value

Intellectual capital disclosure levels can be used to differentiate between firms’ profitability. Previous studies established that financial performance is an indicator used to differentiate between companies with high and low voluntary disclosure. Hence, it is expected to be enhanced at a higher level of financial performance. Generally, the level of disclosure is positively associated with an organization’s financial profitability of an organization (Williams, Citation2001). Intellectual capital disclosure (ICD) describes the outcome of a company’s knowledge-based activities. Hence, a CEO will disclose intellectual capital as a statement to stakeholders to legitimize company activities (Striukova et al., Citation2008). Similarly, good financial positions intensify the credibility of an organization’s information (Scott, Citation1994). Companies with high profitability tend to disclose more human resource accounting information to justify their source of effectiveness and efficiency (Syed & Özbilgin, Citation2009). Therefore, based on previous studies, the relationship between financial performance and intellectual capital disclosure varies. According to Rahim et al. (Citation2011), profitability influences intellectual capital disclosures. Similarly, Ousama et al. (Citation2012) and Suhardjanto and Wardhani (Citation2010) attribute intellectual capital disclosure to high financial performance.

However, Ferreira et al. (Citation2012), Ibikunle and Damagum (Citation2013), and Kateb (Citation2015) demonstrate that profitability does not affect intellectual capital disclosure. Ramadan and Majdalany (Citation2013) establish a negative and significant effect of financial performance on intellectual capital disclosure. The inconsistency in the results between financial performance and firm value may be attributed to intellectual capital disclosure. Generally, financial performance has a positive and significant effect on firm value (Ketut, Citation2016; Kevin & Omagwa, Citation2017). Similarly, Pascareno and Siringoringo (2016), Luqman Hakim and Sugianto (Citation2018), and Sigit Hermawan (Citation2014) establish that financial performance does not affect firm value. However, Al-Nawaiseh, (Citation2017) revealed that financial performance has no statistically significant effect on a firm’s value, citing a lack of appropriate measures to measure financial performance. However, there are still contradictory results regarding intellectual capital disclosure (ICD) and firm value. According to Abdolmohammadi (Citation2005), intellectual capital disclosure influences market capitalization value among the 500 comp financial performance, firm value, intellectual capital disclosure, and firm value.

Similarly, Vafaei et al. (Citation2011) established that intellectual capital disclosure has a positive effect on firm value-based control for country and industry characteristics. Additionally, intellectual capital disclosure has a positive and significant effect on firm value in cross-sectional analysis (Orens et al., Citation2009). Based on this description, the relationship between financial performance, intellectual capital disclosure, and firm value has sufficient theoretical and empirical support to propose the following hypothesis:

H04 We hypothesize that intellectual capital disclosure does not mediate the relationship between financial performance and firm value.

5. Research design

5.1. Sample and data collection

The study considered 63 listed firms on the Nairobi Security Exchange (NSE), and few studies have sought to investigate the association between financial performance, intellectual capital disclosure, and firm value in NSE, which has the most efficient, active, and capitalized stock market in East Africa (Capital Markets Authority of Kenya, Citation2019). Additionally, NSE offers great insight because it is composed of firms from different sectors. For accurate analysis, we trimmed the sample through the following ways to enable the testing of the research hypothesis, we excluded (9) firms that did not have complete audited published reports on their website, as well as (15) that had missing CEOs statements and at one point they were discontinued from trading their shares in NSE during the period (2010–2022), Post-election Violence 2007/2008 and at high market uncertainty during the pandemic of COVID 19, that the capital market witness a lot of turbulent and low efficiency. Consequently, we deleted 312 observations from 819 observations, and the remaining 507 observations from 39 firms were used for the analysis. This study adopted a balanced panel data approach for analysis based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The balanced approach was adopted since it allows observations of same units in every time period, which reduces heterogeneity (Liu et al., Citation2022). shows the sampled firms classified based on classification standards by the NSE. We extracted data from published financial reports on various company websites and databases.

Table 1. Sample selection and industry cluster.

5.2. Measure

5.2.1. Dependent variable

Firm value is the ability of a firm to give its stakeholders a satisfactory return on investment. The study measured firm value using Tobin’s Q. Tobin’s Q has been widely utilized in previous studies (Brainard & Tobin, Citation1968; Gompers et al., Citation2003; Nsour & Al-Rjoub, Citation2022; Tobin, Citation1969). Tobin’s Q is the ratio of the firm’s market value to the asset replacement cost. Therefore, Tobin’s Q parameter used for the study was expressed using the following formula (Balagobei, Citation2018):

(1)

(1)

where

is equity book value and

is the equity market value

5.2.2. Mediating variable

Intellectual capital disclosure was the mediating variable. This study measures intellectual capital disclosure using a content analysis index approach (see Appendix I for the items). This is in accordance with previous studies (Sardo & Serrasqueiro, Citation2017; Tejedo-Romero et al., Citation2017). Data regarding intellectual capital disclosure were obtained from the corporate website and NSE in the HTML format. The data were utilized for analysis because they were comprehensive and available to all stakeholders at a lower cost. The HTML web pages of the sample firms were analyzed based on the presence of intellectual capital disclosure on CEO statements. Additionally, the study adopted an unweighted approach, assigning similar weights for each intellectual capita item analyzed. It allowed all disclosed items to get an equal level of importance, which helped to avoid unforeseen subjectivity in the analysis (Cooke, Citation1989). Generally, we assign a score of 1 if the item is disclosed in the CEO statement and 0 otherwise. We calculate the ICD indices (HC, SC, and RC) and the overall ICDs for the firm as follows:

(2)

(2)

(3)

(3)

(4)

(4)

(5)

(5)

where

is the score conferred on each IC item (1 if the item is disclosed in the CEO statement and 0 otherwise), and h, s, and r represent the number of IC items disclosed in the HC, SC, and RC categories, respectively. M denotes the total number (36) of IC items.

5.2.3. Independent variable

Financial performance is attributed to a company’s ability to make a profit (Nurazi et al., Citation2020). Thus, financial performance was measured as the return on assets (ROA), which is the ratio of a firm’s earnings (before tax) to total assets. ROA shows the extent to which a firm is utilizing its assets. A high ROA means that the firm utilizes its assets efficiently for value (Chiu & Chen, Citation2017; Gul et al., Citation2011; Shaw et al., Citation2013; Van Vu et al., Citation2018). Previous studies Cindiyasari et al. (Citation2022); Firer and Williams (Citation2003); Chen et al. (Citation2005), relied upon ROA measuring financial performance as operating performance defined as (Operating Income Before Depreciation (OIBD)/Total Assets). The measure was appropriate because it does not penalize firms for use of leverage in their capital structure and excludes the effects of taxation (Barber & Lyon, Citation1996; Ji et al., Citation2020; Loughran & Ritter, Citation1997). Thus, a high return on assets is a sign of solid financial and operational performance. ROA was computed as shown below:

(6)

(6)

where,

is return on assets,

is profits before intrest, tax and depreciation and

is the total assets.

5.2.4. Control variables

Thus, following previous researches, we included several control variables, based upon the benchmark papers on area of study, which are related to the characteristics of the company and its environment in the study model. The study has not used all the controls as identified in the benchmark papers which could have caused an unmanageable scope of the study (Hashmi et al., Citation2020). The benchmark paper for institution ownership (Navissi & Naiker, Citation2006; Pirzada et al., Citation2015; Tsouknidis, Citation2019); for firm size (Fama & French, Citation1992; Haniffa & Cooke, Citation2002; Putra & Lestari, Citation2016); Hanafi and Halim (Citation2009) for leverage; and liquidity Alsaeed (Citation2006). These variables are estimated through:

5.3. Data processing and analysis

The data was analyzed using Stata Student version 13. The Hausman test was carried out to determine the choice between the fixed effect model (FEM) and the random effect model (REM) (Green, Citation2008). To test the suitability of the model, the study utilized the ANOVA (F-statistics) and rANOVa (Wald chi2). The hypothesis path was tested using multiple regression models, and the mediation index was calculated using the 2 × 2 conditional process analysis design of Igartua and Hayes (Citation2021). Where Ɵх→y = ab at [5000 bootstrap] sample.

5.3.1. Research model

The study employed Baron and Kenny (Citation1986) approach to establish the mediating effect of intellectual capital disclosure on the relationship between financial performance and firm value. Intellectual capital disclosure is considered a mediator because it extends the relationship between financial performance and firm value. According to Baron and Kenny (Citation1986), to establish a mediating effect, the independent variable must affect the mediator. Second, the independent variable must affect the dependent variable. Third, the mediator has to have an effect on the dependent variable. The four steps of mediation followed by the study are as follows (Kenny et al., Citation1998; Koubaa & Jarboui, Citation2017; Salhi et al., Citation2019):

Step 1: the independent variable must affect the dependent variable (M.1).

Step 2: the independent variable must affect the mediating variable (M.2).

Step 3: the mediating variable to affect the dependent variable (M.3).

Step 4: To determine if the mediating variable completely mediates XY, the effect of X on Y Controlling for M should be zero (estimate and test path c’) (M.4).

The study developed the 4 multiple regression model to test the study hypothesis:

(M.1)

(M.1)

(M.2)

(M.2)

(M.3)

(M.3)

(M.4)

(M.4)

The study model (M.4) is equivalent to

where the

are the Intellectual Capital Disclosure (mediating variable),

is firm value (dependent variable),

is financial performance (independent variable), LEV is Leverage, LIK is Liquidity, SIZE is firm size (ln TA) and IO is Institution ownership.

6. Empirical results and discussion

6.1. Robustness checks

The study carried out the robustness analysis to examine how certain ‘core’ regression coefficients estimates behave when the regression specification is modified by adding or removing regressors. The study carried out normality, multicollinearity, unit root test for heteroscedasticity, autocorrelation, and specification error.

6.1.1. Test of normality

presents the skewness and kurtosis of the study variables. Skewness/kurtosis shows the number of observations and the probability of skewness (ρ = value of skewness <0.05). While, (Kurtosis) indicated that kurtosis was asymptotically distributed (ρ value of kurtosis <0.05). The results show that the hypothesis that firm value is normally distributed was not rejected, at least at the 9.2% level, in the joint Prob [chi (2)=4.677, ρ > 0.05 (ρ = 0.092)]. The kurtosis for firm value is 2.3, and the p-value of 0.0312 is significantly different from the kurtosis of the normal distribution at the 5% significance level. Further, the results indicate that we cannot reject the hypothesis that financial performance (ROA) is normally distributed, at least at 12.3% of the joint Prob [chi (2) = 4.190, ρ > 0.05 (ρ = 0.123)]. The kurtosis for financial performance is 1.885 and the p-value of 0.0445 is significantly different from the kurtosis of a normal distribution at the 5% significance level. Lastly, the hypothesis that intellectual capital disclosure (ICD) is normally distributed was not rejected, at least at the 11.8% level, the joint Prob [chi (2) = 4.027, ρ > 0.05, ρ = 0.118)]. The kurtosis for intellectual capital disclosure is 1.602, and the ρ-value of 0.0428 is significantly different from the kurtosis of a normal distribution at the 5% significance level. Regarding the control variables, the hypothesis of normality was not rejected for firm size, leverage, liquidity, and institutional ownership (asymptotically distributed) (p > 0.05).

Table 2. Skewness/Kurtosis tests for normality.

6.1.2. Test of heteroskedasticity

The Breusch-Pagan/Cook-Weisberg test was used to test for heteroskedasticity, and the results are presented in . The test uses a cluster-robust standard error estimator to control heteroskedasticity. Using this robust standard error estimator (cluster), the study assumed that observations should be independent across clusters (Abdul-Hameed & Matanmi, Citation2021; Gould & Rogers, Citation1994; Martin, Citation2023). Generally, Breusch–Pagan test statistic requires prob [chi (2)], p > 0.05. If the test statistics has a p-value below the appropriate threshold (p > 0.05), then the null hypothesis of homoskedasticity is rejected and heteroskedasticity assumed. The findings in indicated that the prob [chi (2) = 3.21, p > 0.733 (p = 0.099)], revealing that the null hypothesis was not rejected.

Table 3. Breusch-Pagan/Cook–Weisberg test for heteroskedasticity.

6.1.3. Test of autocorrelation

presents the results of the autocorrelation test using the Wooldridge test, as recommended by Drukker (Citation2003). The results showed that the null hypothesis could not be rejected at the 5% significance level based on the p-values [F (1, 506) = 176.60, ρ > 0.05, 95% CI (−0.0108, 0.01238)]. Hence, the null hypothesis was rejected because there was no serial correlation at the 5% level of significance.

Table 4. Wooldridge test for autocorrelation in panel data.

6.1.4. Test of specific error

presents the results of the specific error test using the Ramsey RESET test. Ramsey RESET test was used to test whether the relationship between the dependent variable and the independent variables should be linear or whether a non-linear form would be more appropriate (Domínguez & Lobato, Citation2020; Peters, Citation2000). From the findings, the test displayed an insignificant probability of 0.4576 at the 5% level of significance [F (6, 501) = 10.50, ρ > 0.05, (ρ = 0.4576)]. We thus accept the null hypothesis that the regression model adopted is linear, best fit, and reliable.

Table 5. Ramsey RESET test using powers of the fitted values of firm value.

6.2. Results and discussion

6.2.1. Descriptive results

The study presented descriptive data such as the mean; minimum; maximum; and standard deviation as shown in . The mean of financial performance, measured by return on asset (ROA), was, 0.070471, representing 7.05% (minimum = −1.38569 and maximum = 0.92807; standard deviation = 0.12832. Generally, a ROA of over 5% is generally considered good and over 20% is always considered excellent (Talha et al., Citation2022). However, return on assets (ROAs) should be compared among firms in the same sector. Additionally, the mean of firm value, proxy as Tobin’s q, was 0.607483 (minimum = 0.10064 and minimum = 1.60517; standard deviation =0.12832). Tobin’s q measures whether a firm or aggregate market is relatively overvalued or undervalued. Generally, if Tobin’s q is greater than 1.0, then the market value is greater than the value of the company’s recorded assets (Thomas, Citation2021). However, the study average across the 11 sectors was 0.6075. Thus, the market value of firms listed at the Nairobi Securities Exchange [NSE] dint reflects unmeasured or unrecorded assets in their financial statements since the book value was greater than the market value [Tobin’s q is less than 1.0] (Al-Shatnawi & Al-Dalabih, Citation2019). Further, intellectual capital disclosure had a mean of 0.093378 (minimum =0.00000 and maximum =1.95371; standard deviation = 0.22872). Generally, disclosure is a way to report the nature of intangible value that is owned by the company (Susanto et al., Citation2019).

Table 6. Descriptive statistics.

While the mean institution ownership was at 0.690935 (69.09%) (Minimum = 0.10148 and maximum = 0.96932; standard deviation = 0.16545). In line to Modigliani and Miller (Citation1958), company’s funding decisions related to company’s capital structure can affect the firm’s value (Brusov et al., Citation2021). Hence, it is perfectly normal for 70% or more of any individual stock to be held by institutional investors (Sarpong-Danquah et al., Citation2023). Leverage had a mean value of 2.00880 (minimum = 0.08497 and maximum =9.13304; standard deviation =1.89080). Hence, a financial leverage ratio of 1.5 indicates that a company is using a fair amount of debt to finance its assets. While, a low average ratio indicates that the company is financing its assets with only equity capital and no debt. Thus, a 2.0 on average leverage ratio imply that for every 1 percent change in its EBIT, the firm’s EPS will change by 2 percent (Lee et al., Citation2023).

Liquidity had a mean of 1.87682, (minimum = 0.08497 and maximum = 9.63869; standard deviation =13.69782). In short, a ‘good’ liquidity ratio is anything higher than 1. A liquidity ratio of 1 is unlikely to prove that the business is worthy of investment. Generally, creditors and investors look for an accounting liquidity ratio of around 2 or 3 (Bordeianu & Radu, Citation2020). Therefore a ‘good’ liquidity ratio is anything higher than 1. The mean size was 7.33757 (minimum= 3.5117 and maximum = 15.761; standard deviation = 1.84722). According to Jogiyanto (Citation2000), a firm size measurement is relevant by applying the natural log of total assets since it has a better stability level than applying other proxies.

6.2.2. Correlation results

presents results on correlation analysis between the studied variables variable and Variance Inflected Factor (VIF) for respective variable. The results are as shown in , showed that VIF statistic values were within the recommended range of value of VIF is ˂10 and Tolerance ˂1 (Lavery et al., Citation2019; Stevens, Citation2009). And values of correlation among variables are r ˂ 0.9 (Hair et al., Citation2010). This implies that the assumption of multicollinearity was not violated. In addition, presents results for correlation statistics between the studied variables. It was established that firm value and financial performance are positively correlated (r = 0.267; ρ < 0.05). Therefore, financial performance is suitable in predicting firm value. Thus, a high financial performance is a positive signal that the company will have better prospects in the future. Similar, findings were established by Sucuahi and Carbarihan (2016) and Yanto (Citation2018). Additionally, the study found that intellectual capital disclosure and firm value were positively correlated (r = 0.175; ρ < 0.05). Thus, intellectual capital disclosure is expected to influence firm value positively. The findings are consistent to Mansour et al. (Citation2014), Alfraih and Almutawa, (Citation2017) and Mardiati and Katarina, (Citation2018) attributed that disclosure of intellectual capital in the annual financial statement influences firm value positively. The study also found that financial performance (r = 0.262; ρ < 0.05) positively correlated to intellectual capital disclosure. Lastly, in relation to the control variables; firm size and firm value had a negative and significant correlation (r = −0.507; ρ < 0.05). Secondly, leverage and firm value also had a negative and significant association (r = −0.663; ρ < 0.05). Finally, institution ownership and firm value had positive association based on the coefficient of correlation (r = 0.053; ρ > 0.05), however the association was not significant. Lastly, liquidity and firm value also had a negative and significant association (r = −0.230; ρ < 0.05).

Table 7. Correlation matrix between variables and VIF values.

6.3. Hypothesis testing

Hausman test was carried out to determine the choice between the fixed effect model (FEM) and the random effect model (REM). The null hypothesis was rejected when ρ-value >0.05 of the chi-square (Green, Citation2008). Based on the result in , models 1a, 3b, and 4a had chi-square ρ-value ˂0.05, thus, the study utilized the fixe effect model (FEM). Additionally, based on the results in model 2a had a chi-square ρ-value >0.05 (ρ = 0.890) of the chi-square greater than 0.05. Hence the study utilized the random effect model to establish the relationship between intellectual capital disclosure and firm value.

Table 8. Financial performance, intellectual capital disclosure and firm value.

Mode 1a shows the relationship between financial performance and firm value. The results depicts a coefficient estimate of financial performance that is positive and significant [β1=0.112, ρ˂0.05 (ρ>│t│=0.000)] on firm value. The results indicate that the financial performance is positively associated with firm value. Thus, the null hypothesis (H01) was rejected. We conclude that financial performance is positively associated with firm value. Further, a unit change in financial performance leads to a 0.112 unit change in firm value. Regarding the control variable introduced in the model, the results showed that only firm size (β= −0.0550, ρ˂.005) had a negative and significant effect on the study phenomenon.

Model 2a relates to the effect of intellectual capital disclosure (ICDs) on firm value, revealing that ICD had a positive and significant effect on firm value based on the coefficient estimate [β1=0.07503, ρ˂0.05 (ρ>│t│=0.010)]. Thus, intellectual capital disclosure positively influences firm value. Thus, the null hypothesis (H02) was rejected. We conclude that intellectual capital disclosure (ICDs) is positively associated with firm value. Therefore, a unit increases in intellectual capital disclosure results in 0.07503 units changes in firm value. Regarding the control variables introduced in the model, the results showed that only firm size (β= −0.06413, ρ˂.005) and leverage (β= −0.02003, ρ˂.005) had negative and significant effect on the study phenomenon respectively.

Model 3a shows the effect of financial performance on intellectual capital disclosure. The study findings indicated that financial performance had a negative and significant effect on intellectual capital disclosure, based on the coefficient estimate [β1 = −0.188, ρ˂0.05 (ρ>│t│ =0.039)]. Hence, H03 is rejected, and we conclude that financial performance is negatively and significantly associated with intellectual capital disclosure. Further, a unit change in financial performance leads to a −0.188 unit change in intellectual capital disclosure. Regarding the control variables introduced in the model, the results showed that all the control variables had no significant association on the study phenomenon.

Model 4a relates to the combined effect of financial performance and intellectual capital disclosure on firm value. The result depicted a coefficients of the indirect effect [c" = 0.1264, ρ < 0.05 (ρ>│t│=0.002)], was significant, which the effect of financial performance on firm value controlling for intellectual capital disclosure and indirect effect [β1=0.0769, p˂0.05 (p>│t│=0.005)] was also significant, the effect of intellectual capital disclosure on firm value controlling for financial performance. The study results established a mediating effect of intellectual capital disclosure on the relationship between financial performance and firm value among firms listed on the Nairobi Security Exchange, since all four steps have significant effects, as suggested by Kenny et al. (Citation1998) (Koubaa & Jarboui, Citation2017; Salhi et al., Citation2019).

Additionally, to establish the mediating index, we adopted the 2 × 2 condition process analysis design of Igartua and Hayes (Citation2021). Where Ɵх→y = ab at [5000 bootstrap] sample, the index −0.0144572 = [−0.188*0.0769], the indirect effect at 5000 bootstrap ranged from CI (−0.79000, 3.006). Generally, a decrease of 0.014193 units of intellectual capital disclosure, on average, resulting from increase in financial performance is associated with high firm value. The findings show an indirect effect at 5000 bootstrap ranged from CI (−0.79000, 3.006). The estimated mediating effect index (−0.014193) lies between the interval range and, hence, is not equal to zero. The study concluded that the indirect effect is significant; hence, partial mediation exists (Igartua & Hayes, Citation2021). Therefore, we reject Hypothesis (H04) that states that intellectual capital has no significant mediating effect on the relationship between financial performance and firm value. Hence, intellectual capital disclosure partially mediates the relationship between financial performance and firm value.

6.4. Discussion

Financial performance and firm value link, as well as financial performance and intellectual capital disclosure on firm value link, have developed into research focus areas for both academia and industry practitioners over years. However, previous researchers on both links have not examined the mediating role of intellectual capital disclosure in financial performance and firm value nexus.

Firstly, the study found that there is a significant positive relationship between financial performance and firm value. The study findings are in line with those of (2016; Gharaibeh & Qader, Citation2017; Yanto, Citation2018). They attribute high firm value to better financial performance. However, the results contradict the findings of Pascareno and Siringoringo (2016) and Luqman Hakim and Sugianto (Citation2018), who found no significant association between financial performance and firm value. Therefore, high firm value is attributed to organizational financial performance, which acts as a signal to investors regarding future prospects. Therefore, high financial performance is a positive signal that a company will have better prospects in the future from the perspective of signaling theory. Hence, high financial performance serves as a signal to investors on firm ability to use its resources to generate more revenue and manages its assets, liabilities, and the financial interests of its stakeholders and stockholders. With regard to the control variable introduced in the model, the results showed that all the other control variables had no significant effect on the study phenomenon, except firm size (In TA), which is negatively associated with firm value. Similar findings were established by Bhabra (Citation2007) and Hirdinis (Citation2019), who found that large firms had lower values due to inefficiencies in operations. Hence, investors should not consider firm size when making investment decisions.

Secondly, the study found that intellectual capital disclosure has a positive and significant effect on firm value of listed companies in NSE. This finding is consistent with other studies with similar outcomes (Alfraih & Almutawa, Citation2017; Mansour et al., Citation2014; Subaida et al., Citation2018; Sudibyo & Basuki, Citation2017). However, it contradicted the findings of Curado et al. (Citation2011) who found no significant relationship between intellectual capital disclosure and firm value. In addition, voluntarily disclosed information about a firm’s intellectual capital (IC) will enhance firm value. This position is supported by the signaling theory, which states ICD is regarded as ‘good news’ by capital markets and restrictive disclosure as ‘bad news’. Thus, voluntary ICD lead to a favorable reassessment of the firma and attract new investors by signaling attractive investment opportunities (Castilla-Polo & Gallardo-Vázquez, Citation2016; Healy & Palepu, Citation2001). Hence, we postulate that ICD is value relevant as it reduces information asymmetry which in turn increases equity value as it is argued from agency theory and signaling theory. ICD obviously reduces information asymmetry on capital market and is associated with higher market value, lower cost of equity and higher accounting returns. Firm size affects intellectual capital disclosure and firm value nexus, because large companies provide more information to stakeholders. Generally, larger companies are managed by competent managers. Hence, smaller firms disclose less intellectual, resulting in low firm value. The higher the leverage, the higher the transaction cost as a percentage of trading capital.

Third, the study again found that financial performance has a negative and significant effect on the intellectual capital disclosure of listed companies in the NSE. The findings are consistent with existing studies that found similar conclusions (Ramadan and Majdalany (Citation2013), who establish a negative and significant effect between financial performance and intellectual capital disclosure). However, this contradicts the findings of Falikhatun et al. (Citation2010), who found no statistically significant relationship between profitability and intellectual capital disclosure (ICD). In addition, since the coefficient of profitability is negative in the present study, it also contradicts the studies by Barako et al. (Citation2006), Hossain and de Lasa, (Citation2008), Ousama et al. (Citation2012), and Suhardjanto and Wardhani (Citation2010) that found that profitability had a positive influence on intellectual capital disclosure. Further, increases in financial performance result in a decrease in intellectual capital disclosure. This position is supported by the signaling theory, which echoes that the selected signal must contain the power of information (information content) to be able to change the assessment of the company’s external parties.

Hence, financial performance contains the power of information a company needs to signal to its stakeholders and stockholders. Therefore, firms will legitimize their status through the traditional symbol of corporate success using tangible assets when high financial performance is reported (Guthrie et al., Citation2004; Olateju et al., Citation2021). A firm’s willingness to disclose more intellectual capital is determined by its financial performance. From a strategic point of view, the disclosure of intellectual capital information reflects the effectiveness of a firm’s management. Hence, a CEO discloses more intellectual capital with opportunistic behavior to justify themselves. With regard to the control variable introduced in the model, the results showed that only firm size had a negative and significant association with the study phenomenon. The findings contradicted Rudiawarni et al. (Citation2017), who established that firm size enhances disclosure since it reduces agency costs (Nurunnabi, Citation2016). Therefore, a highly profitable firm will not need to disclose its intellectual capital to legitimize its activities and future prospects.

Lastly, the study found that intellectual capital disclosure mediates the relationship between financial performance and firm value nexus. The study concludes that intellectual capital disclosure is a strong reputation capability. As an organizational capability, firms can effectively utilize financial performance and intellectual capital disclosure by transforming them into imperfect intangible resources to enhance firm value. This result means that financial performance does not directly affect firm value but rather indirectly through intellectual capital disclosure. Therefore, intellectual capital disclosure can be used by company management to gain investor trust, which can be reflected in higher compensation. ICD can lead to a favorable reassessment of the firm and attract new investors by signaling attractive investment opportunities (Castilla-Polo & Gallardo-Vázquez, Citation2016; Healy & Palepu, Citation2001). According to the agency theory, high performance makes it easier for managers to persuade shareholders that their managerial abilities are superior. Therefore, high financial performance serves as a signal to investors about a firm’s ability to use its resources to generate more revenue and manage its assets, liabilities, and the financial interests of its stakeholders and stockholders.

7. Summary and conclusion

Intellectual capital disclosure has emerged as an issue in emerging economies and has become a critical intangible asset for enhancing firm value. Generally, intellectual capital disclosure can lead to a favorable reassessment of the firm and attract new investors by signaling attractive investment opportunities.

This position is supported by the signaling theory, which echoes that the selected signal must contain the power of information (information content) to be able to change the assessment of the company’s external parties. Consequently, high performance is a signal to investors because it contributes to a better reputation. Drawing from agency theory, high performance makes it easier for managers to persuade shareholders that their managerial abilities are superior. Hence, high financial performance serves as a signal to investors about a firm’s ability to use its resources to generate more revenue and manage its assets, liabilities, and the financial interests of its stakeholders and stockholders. Further, drawing from the legitimacy theory, if a firm is rich in intellectual capital, it has no option but to disclose information about its intellectual capital so that stakeholders’ (particularly those who are less powerful) need for information is satisfied and eventually firm value is enhanced. Thus, organization disclose intellectual capital to legitimize their success away from the traditional symbol of perspective, we attribute the high valuation of firms to CEOs’ ability to present intangible assets in their statements as a way to present management in the most favorable light possible to enhance firm reputation and impact stakeholder perceptions in relation to key value drivers. Consistent with agency theory, this study contributes to the literature by providing evidence that intellectual capital disclosure in CEOs’ statements reduces information asymmetry.

Thus, we attribute high firm value to intellectual capital disclosure (ICD) by organizations. Annual reports are generally presented to legitimize their operations and corporate activities to legitimize treats as a result of high or unjustified profits. With regard to policymaking, due to the weak oversight of intellectual capital disclosure, managers might manipulate it to suit their needs. Consistent with agency theory, this study contribute to the literature by providing evidence that intellectual capital disclosure in CEOs’ statements reduces information asymmetry. Thus, organizations disclose intellectual capital to legitimize their success away from the traditional symbol of firm success based on tangible resources. Hence, firms with a high level of intellectual capital disclosure should engage in voluntary disclosure of intellectual capital to legitimize their status. Secondly, this study recommends that firm managers of listed companies should focus on voluntary disclosure of intangible assets for enhanced firm value. Implementation of voluntary disclosure should be in terms of intellectual capital. Also, firm management should focus on short-term goals such as financial performance, which will lead to a positive reputation and hence the achievement of a high long-term goal of firm value. Lastly, from a managerial point of view, our findings highlight the importance of disclosure. We contribute to the literature by providing evidence of the relative importance of firm characteristics in determining levels of disclosure and firm value.

Author contributions

Charles Keter made significant contributions to the article’s design, data analysis, intellectual content and interpretation.

Cheboi Yegon - contributed significantly to the critical revision for important intellectual content and approved the version to be published.

David Kosgei - significantly to the article’s drafting/critical revision for important intellectual content and approved the version to be published.

Acknowledgment

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s). All co-authors have seen and agree with the contents of the manuscript and there is no financial interest to report. We certify that the submission is original work and is not under review at any other publication.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Charles Kiprono Sang Keter

Charles Kiprono Sang Keter, PhD, Department of Accounting and Finance, School of Business And Economics, Moi University, Eldoret, Kenya.

Josephat Yegon Cheboi

Josephat Yegon Cheboi, Professor, Department of Accounting and Finance, School of Business And Economics, Moi University, Eldoret, Kenya.

David Kosgei

David Kosgei, Professor, Department of Agricultural Economics and Resource Management, School of Agriculture & Natural Resources, Moi University, Eldoret, Kenya.

References

- Abdi, Y., Li, X., & Càmara-Turull, X. (2022). Exploring the impact of sustainability (ESG) disclosure on firm value and financial performance (FP) in airline industry: The moderating role of size and age. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 24(4), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-021-01649-w

- Abdi, Y., Li, X., & Càmara-Turull, X. (2022). How financial performance influences investment in sustainable development initiatives in the airline industry: The moderation role of state-ownership. Sustainable Development, 30(5), 1252–1267. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.2314

- Abdolmohammadi, M. J. (2005). Intellectual capital disclosure and market capitalization. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 6(3), 397–416. https://doi.org/10.1108/14691930510611139

- Abdul-Hameed, A. B., & Matanmi, O. G. (2021). A modified Breusch–Pagan test for detecting heteroskedasticity in the presence of outliers. http://article. pamathj. net/pdf/10.11648. j. pamj, 20211006.

- Abhayawansa, S., & Abeysekera, I. (2009). Intellectual capital disclosure from sell-side analyst perspective. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 10(2), 294–306. https://doi.org/10.1108/14691930910952678

- Ahmed Haji, A., & Anum Mohd Ghazali, N. (2013). The quality and determinants of voluntary disclosures in annual reports of Shari’ah compliant companies in Malaysia. Humanomics, 29(1), 24–42. https://doi.org/10.1108/08288661311299303

- Ahmed Haji, A., & Anifowose, M. (2017). Initial trends in corporate disclosures following the introduction of integrated reporting practice in South Africa. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 18(2), 373–399. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-01-2016-0020

- Alfraih, M. M. (2017). The value relevance of intellectual capital disclosure: Empirical evidence from Kuwait. Journal of Financial Regulation and Compliance, 25(1), 22–38. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFRC-06-2016-0053

- Alfraih, M. M., & Almutawa, A. M. (2017). Voluntary disclosure and corporate governance: Empirical evidence from Kuwait. International Journal of Law and Management, 59(2), 217–236. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLMA-10-2015-0052

- Al-Nawaiseh, M. A. L. I. (2017). The impact of the financial performance on firm value: Evidence from developing countries. International Journal of Applied Business and Economic Research, 15(1), 241–253.

- Alsaeed, K. (2006). The association between firm-specific characteristics and disclosure: The case of Saudi Arabia. Managerial Auditing Journal, 21(5), 476–496. https://doi.org/10.1108/02686900610667256

- Al-Shatnawi, H. M., & Al-Dalabih, F. A. (2019). Role of bank characteristics in determining the effect of non-financial information disclosure on bank’s value on Tobin’s Q Scale: An applied study on the Jordanian commercial banks. International Journal of Business Administration, 10(4), 46. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijba.v10n4p46

- Anam, O. A., Fatima, A. H., & Majdi, A. R. H. (2011). Effects of intellectual capital information disclosed in annual reports on market capitalization: Evidence from Bursa Malaysia. Journal of Human Resource Costing & Accounting, 15(2), 85–101.

- Anifowose, M., Abdul Rashid, H. M., & Annuar, H. A. (2017). Intellectual capital disclosure and corporate market value: Does board diversity matter? Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies, 7(3), 369–398. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAEE-06-2015-0048

- Anifowose, M., Rashid, H. M. A., & Annuar, H. A. (2016–2017). The moderating effect of board homogeneity on the relationship between intellectual capital disclosure and corporate market value of listed firms in Nigeria. International Journal of Economics, Management and Accounting, 25(1), 71–103.

- Awais, M., Laber, M. F., Rasheed, N., & Khursheed, A. (2016). Impact of financial literacy and investment experience on risk tolerance and investment decisions: Empirical evidence from Pakistan. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 6(1), 73–79.

- Baker, H. K., Kumar, S., & Pandey, N. (2020). A bibliometric analysis of managerial finance: A retrospective. Managerial Finance, 46(11), 1495–1517. https://doi.org/10.1108/MF-06-2019-0277

- Baker, S. R., Bloom, N., Davis, S. J., & Terry, S. J. (2020). COVID-induced economic uncertainty (No. w26983). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Balagobei, S. (2018). Corporate governance and firm performance: Empirical evidence from emerging market. Asian Economic and Financial Review, 8(12), 1415–1421. https://doi.org/10.18488/journal.aefr.2018.812.1415.1421

- Barako, D. G., Hancock, P., & Izan, H. Y. (2006). Factors influencing voluntary corporate disclosure by Kenyan companies. Corporate Governance, 14(2), 107–125. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8683.2006.00491.x

- Barber, B. M., & Lyon, J. D. (1996). Detecting abnormal operating performance: The empirical power and specification of test statistics. Journal of Financial Economics, 41(3), 359–399. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(96)84701-5

- Barlian, R. S. (2003). Manajemen Keuangan. Literata Lintas Media.

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social Psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173

- Basu, S., & Waymire, G. (2008). Has the importance of intangibles really grown? And if so, why? Accounting and Business Research, 38(3), 171–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/00014788.2008.9663331

- Bayraktaroglu, A. E., Calisir, F., & Baskak, M. (2019). Intellectual capital and firm performance: an extended VAIC model. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 20(3), 406–425. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-12-2017-0184

- Bellucci, M., Marzi, G., Orlando, B., & Ciampi, F. (2021). Journal of Intellectual Capital: A review of emerging themes and future trends. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 22(4), 744–767. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-10-2019-0239

- Bhabra, G. S. (2007). Insider ownership and firm value in New Zealand. Journal of Multinational Financial Management, 17(2), 142–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mulfin.2006.08.001

- Bordeianu, G.-D., & Radu, F. (2020). Basic types of finan-cial ratios used to measure a company’s perfor-mance. Economy Transdisciplinarity Cognition, 23(2), 53–58.

- Botosan, C. A., & Plumlee, M. A. (2002). A re-examination of disclosure level and the expected cost of equity capital. Journal of Accounting Research, 40(1), 21–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-679X.00037

- Boujelbene, M. A., & Affes, H. (2013). The impact of intellectual capital disclosure on cost of equity capital: A case of French firms. Journal of Economics Finance and Administrative Science, 18(34), 45–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2077-1886(13)70022-2

- Bozzolan, S., Favotto, F., & Ricceri, F. (2003). Italian annual intellectual capital disclosure: An empirical analysis. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 4(4), 543–558. https://doi.org/10.1108/14691930310504554

- Brainard, W. C., & Tobin, J. (1968). Pitfalls in financial model building. The American Economic Review, 58(2), 99–122.

- Brand Finance Institute. (2017). Global intangible finance tracker 2017: An annual review of the world’s intangible value. Brand Finance Institute.

- Brennan, N., & Connell, B. (2000). Intellectual capital: Current issues and policy implications. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 1(3), 206–240. https://doi.org/10.1108/14691930010350792

- Brown, N., & Deegan, C. (1998). The public disclosure of environmental performance information—a dual test of media agenda setting theory and legitimacy theory. Accounting and Business Research, 29(1), 21–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/00014788.1998.9729564

- Brusov, P., Filatova, T., Orekhova, N., Kulik, V., Chang, S. I., & Lin, G. (2021). Generalization of the Modigliani–Miller theory for the case of variable profit. Mathematics, 9(11), 1286. https://doi.org/10.3390/math9111286

- Cabrita, M. R., & Vaz, J. L. (2006). Intellectual capital and value creation: Evidencing in portuguese banking industry. Electronic Journal on Knowledge Management, 4(1), 11–19.

- Capital Markets Authority of Kenya. (2019). Keynote address by Mr Paul Muthaura. MBS Regulatory Sandbox PGN Validation Workshop, 20–21 February. https://cma.or.ke/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=529:keynoteadress-by-mr-paul-muthaura- mbs-regulatory-sandbox-pgn-validation-workshop-feb-20-2019&catid=13&Itemid=208

- Castilla-Polo, F., & Gallardo-Vázquez, D. (2016). The main topics of research on disclosures of intangible assets: A critical review. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 29(2), 323–356. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-11-2014-1864

- Cerbioni, F., & Parbonetti, A. (2007). Exploring the effects of corporate governance on intellectual capital disclosure: An analysis of European biotechnology companies. European Accounting Review, 16(4), 791–826. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638180701707011

- Chen, X., Vierling, L., & Deering, D. (2005). A simple and effective radiometric correction method to improve landscape change detection across sensors and across time. Remote Sensing of Environment, 98(1), 63–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2005.05.021

- Chen, Z. M., & Chen, G. Q. (2011). An overview of energy consumption of the globalized world economy. Energy Policy, 39(10), 5920–5928. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2011.06.046