?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The trade war between the United States and China since 2008 has opened strategic opportunities to increase the economic market in ASEAN countries. This research aims to answer whether the trade war led to an oligopoly or a systemic market structure as a strategy for increasing demands, especially in ASEAN countries. The research exploration refers to trade data between Indonesia and ASEAN at the start of the 2018 US-China trade war and compares it with the latest data for 2020. This research uses the Results Index of C5 Analysis of ASEAN Trading Partner Countries and the Herfindahl–Hirschman index to examine trade between China, America, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan in the ASEAN economy. Findings, in a way, empirically shows that the Results Index of C5 Analysis of ASEAN Trading Partner Countries before and after US-China trade made market concentration moderate and caused an increase in the value of C5 Analysis Results of ASEAN Trading Partner Countries. Discounts on Herfindahl–Hirschman the index needs to pay attention to import players in ASEAN before the trade war. However, after the trade war, there was an increase in the Herfindahl–Hirschman index, which has a trend toward a collusive oligopoly market structure.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

The US-China trade dispute has profoundly impacted global economic and political dynamics, especially in Southeast Asia and the ASEAN nations. Global supply chains have changed due to this war, forcing companies to diversify and move their manufacturing outside China and the US. Uncertainty in international trade has agitated the financial system and could impede economic expansion. Trade disputes may also affect commodity prices and exchange rates, affecting imports and exports. Due to the global turmoil, the conflict poses a risk to economic stability even though it can open up new commercial opportunities. The ASEAN countries are collaborating to address the area’s financial issues, but to minimize the conflict’s impact and take advantage of emerging prospects, they would need to adjust their investment and trade regulations.

A retreat from economic globalization and a rise in regional polarisation are the results of the US-China competition. Small nations with highly open economies, such as Malaysia, will maintain strategic ambiguity as long as their rivalry does not become a full-scale military confrontation. Economic performance is Malaysia’s key priority, particularly in the post-Covid-19 era. The current Russia-Ukraine situation presents issues for the state regarding managing food and economic instability. The US-sponsored ‘democracy versus autocracy’ division campaigns are met with indifference from Malaysia. However, a coordinated response to the growing Sino-American strategic rivalry requires regional cohesion. It is still being determined if the leaders of Malaysia and ASEAN can cooperate to manage the erratic and intensifying US-China competition (Chin, Citation2023).

More than final consumer goods, the Trump-China trade spat has upset global value chains and hurt the economy. The GTAP model assessed the dispute’s economic effects and found that the US would have lost minimal revenue from the 2018 tariff increases without a Chinese response. However, the tariff cuts in the 2020 Phase One Agreement more than made up for the losses. Removing the tariffs imposed by the Trump administration would improve macroeconomic outcomes, increase commerce between the US and China, and lower obstacles to efficient production (Zheng et al., Citation2023).

US policy propaganda over the past decade in the US-China trade war has disrupted the political and economic order of countries in the world. From a financial perspective, this policy triggers trade contractions in US trading partner countries, especially China, and other countries face trade-offs (Fetzer & Schwarz, Citation2021). World macroeconomic shocks blur the import trade liberalization scheme, and shifts and adjustments impact increasing trade consequences (Dullien, Citation2018). Meanwhile, US political results show that countries are more open to increasing import competition from China (Che et al., Citation2022). Trade liberalization aims to achieve seemingly limitless trade between countries, open domestic markets for trading partners, and gain access to international markets. Ultimately, the economic logic of multilateral tariffs and the promotion of global and regional trade underlies the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and the World Trade Organization (WTO) are still considered relevant (Sheldon et al., Citation2018).

Due to tariff disparities between the US and China, commerce between the two countries rose in 2018. Trade between the two nations has suffered due to the tariff disparity, but China is now more competitive. This has given rise to worries on how other nations, such as Indonesia, may affect the tax. Chinese products may become more expensive for US consumers if China raises tariffs on commodities coming from China. Nonetheless, from 65% in 2000 to 74% in 2014, more raw materials were exported from Indonesia. This suggests that tariffs on raw materials may have an impact on Indonesia’s exports if China and other Asian nations utilize Indonesian input to export raw materials to the US. The US’s increased tariffs on Chinese raw materials may have an impact on Indonesia’s exports. The US could stop importing raw materials from China if it starts consuming raw resources domestically and lowers tariffs on imports from China and other Asian nations.

Over the past ten years, in the perspective of the initial trade war benefiting the US economy, explained by the relatively weak Chinese retaliatory response, the US agricultural and automotive sectors are expected to suffer the most in the future (Žemaitytė & Urbšienė, Citation2020). The imposition of import tariffs on China impacts the macroeconomics of trade tariffs and the multilateral trading system; domestic events stabilize the macroeconomy (Chou et al., Citation2018). A trade war will be detrimental to the welfare of both parties. The diversion of US imports from China to other countries in various sectors causes the imposition of additional tariffs so that they are not completely diverted, such as oil commodity prices and Chinese stocks, which responsively impact aggregate demand (Bai & Koong, Citation2018). Meanwhile, the relatively large decline in total imports between the US and China has impacted the loss of welfare of the (US) machinery and electrical products sector, as well as Chinese soybeans and cars (Tu et al., Citation2020). Based on simulation results (Tu et al., Citation2020), US imports from China and Chinese imports from the US will decrease by $91.46 and $36.71 billion, respectively. The impact of the US-China war on trade was large, causing a reorganization of value chains in East Asia (Bekkers & Schroeter, Citation2020). The impact of US policy on Chinese import tariffs triggered a contraction in commodity trade in ASEAN countries, South Korea, Japan, China, Taiwan (Chong & Li, Citation2019).

In response to the US’s imposition of additional tariffs on imports, the Chinese government took similar actions on several commodities. China imposed retaliatory tariffs in three stages on certain products from the US. China’s activities, policies and practices regarding the transfer of technology, intellectual property and innovation are aimed at lowering the prices of US exports to China. Meanwhile, US policies that limit technology transfers to China and the business activities of several Chinese technology companies have caused a decoupling between the two parties (Kwan, Citation2020). However, the US believes that the retaliatory tariffs imposed by China are not in line with the rules set by the WTO and, therefore, opposes them.

above shows that the tariffs imposed by the US in September 2019 were around 21.2%, or an average increase of 6 times from January 2018 of 3.1%. Meanwhile, China increased retaliatory tariffs by 21.8% in September 2019 from 8% in January 2018. This means that China’s retaliatory policy against the US for imposing trade import tariffs increased by an average of 2.7 times and is approaching the US tariff policy import tariffs. A rising tariff trend occurred during the US-China trade war in 2018 and 2019. However, the US considered supporting global demand in setting trade tariffs would benefit its position.

The US’s important role in regulating trade policy is related to financial regulation and the ownership of the US central bank, which de facto acts as the world’s lender of last resort. The US benefits more because it can borrow and pay for imports in its currency, so the possibility of burdensome balance of payments burdens can be minimized (James, Citation2013). This position allowed the US to consistently experience large and sustainable current account deficits since the early 1980s. However, China has attracted world attention to the global trade cooperation system and reform of the WTO system. Trade leads to compromise even though China is seen as weakening international cooperation and offering a policy of subsidizing trade tariffs. China benefits from implementing technology transfer to foreign companies as a prerequisite for accessing the Chinese market. At the same time, the incompatibility of the WTO framework with China’s economic model causes capitalism to weaken the WTO’s ability to reduce emerging tensions (Mavroidis & Sapir, Citation2021).

China is interested in maintaining its global trade position as a country with a high export capacity. This position strengthens the important role of Chinese trade in influencing other global economies, such as the ASEAN economy. Meanwhile, the steps taken by the US were to move its operations to other Asian economic markets (India and Vietnam). The dispute between both parties brought international trade relations to the economic protectionism of each country and sparked criticism in various parts of the world. The consequences and trade tariff policies related to US economic sanctions against China are considered in China’s position rather than the US (Dorsey, Citation2019). This position is reinforced by the results of Harvard’s CAPS/Harris Poll survey, which showed that 63% stated that the imposition of tariffs on Chinese products ultimately harmed the US, and 74% said that US consumers enjoyed most of the tariff burden. Even though the competition and great power of the two countries both influence cooperative relations in other East Asian regions such as Vietnam and Laos (Bekkevold, Citation2020).

China’s policy during the trade war referred to capitalist economics and market reform, and it is reasonable to suspect that their trading power led to oligopoly conditions. Several reasons cause this condition. First, China is considering countermeasures in the form of additional tariff policies and increasing tariffs by an average of 20%, covering 50% of bilateral trade. Second, the inconsistency of the US-China trade policy impacts national security in the political and economic fields. Third, what about other policy changes to restore bilateral trade relations by excluding certain product commodities? The three assumptions above were built to become the basis for this paper as a research gap and lead to an analysis of economic trade conditions in ASEAN. In other cases, the US reduced its growing trade deficit with China. The imposition of additional tariffs has harmed China and made China implement individual country-specific counter-export policies. Ultimately, China only purchased exports worth US$200 billion (Bown, Citation2021). This strengthens the suspicion that the trade commitment of both parties is in an oligopoly or collusive oligopoly condition, which has a systemic impact on the economies of alternative countries in the ASEAN region.

This research aims to answer whether the trade war led to an oligopoly or a systemic market structure as a strategy for increasing markets, especially in ASEAN countries. The US-China trade war has thrown global market conditions into uncertainty. For countries in the ASEAN region, firstly, market movements have shown few significant changes overall. Second, superior commodities are a concern for supply and demand prices in regional markets (prices remain the same). Meanwhile, thirdly, the position of ASEAN’s trading partners in other Asian regions, such as Japan and Korea, trade stability slightly affects the existence of incumbent players. Fourth, China’s rapid maneuvering in market shifts in ASEAN shows that the relationship between investment and production of goods with Vietnam is strong because China and Vietnam are very close geo-regional factors.

This research aims to answer whether the trade war led to an oligopoly or a systemic market structure as a strategy for increasing markets, especially in ASEAN countries. The US-China trade war has thrown global market conditions into uncertainty. For countries in the ASEAN region, firstly, market movements have shown few significant changes overall. Second, superior commodities are a concern for supply and demand prices in regional markets (prices remain the same). Meanwhile, thirdly, the position of ASEAN’s trading partners in other Asian regions, such as Japan and Korea, trade stability slightly affects the existence of incumbent players. Fourth, China’s rapid maneuvering in market shifts in ASEAN shows that the relationship between investment and production of goods with Vietnam is strong because China and Vietnam are very close geo-regional factors (Grundke & Moser, Citation2019). Hidden agreements led to differences in patterns formal and informal economic relations (Henry & Milovanovic, Citation1996). Indirectly, the two warring countries violated the rules implemented by the WTO. In particular, the US feels capable of influencing WTO trade policy, and China is trying to use the influence of its global market power to reform the WTO’s markets and regulatory system. As a result, aggregate demand may be unstable (market disruption), and market conditions are unclear. Dynamic macroeconomic models should respect clear market principles, and dynamics should not give rise to new problems in the global and bilateral trading system. Market uncertainty is not the only way to reconcile macroeconomics in the US-China trade war, especially in ASEAN (McCallum, Citation1983). This is the first paper to analyze and compare the scope of China-US market concentration in ASEAN, making it possible to find more detailed findings and implications for policymakers.

2. Literature review

2.1. Impact of import tariffs from the US-China trade war on the ASEAN region

The direct view in the context of developing countries is protectionism and nationalism by comparing developed countries with the response to the rise of China’s economic trade, such as technology transfer, industrial and trade subsidies, as well as investment distortions, which are a concern regarding the unequal distribution of benefits (Pangestu, Citation2019). Developing countries like Indonesia do not benefit from the US-China trade war. To increase regional economic integration, especially the core issue of trade wars, Indonesia faces uncertain competitive conditions, and the impact of uncertainty far outweighs the benefits. States that require Indonesia to participate in the multilateral trading system in the ASEAN region require industrial subsidies, strengthening intellectual property rights, and handling investment issues, especially technology transfer and trade policy. Meanwhile, from an economic and political perspective, trade wars are principally related to trade imbalances and competition for control of the global economy (Chong & Li, Citation2019). However, according to (Nugroho et al., Citation2021), the impact of the trade war increased real household income. It reduced poverty in Indonesia through trade diversion, expanding its trade exchange rate and ultimately increasing revenue the main household factor. Although income inequality in Indonesia is expected to increase because the real income of high-income households exceeds the real income of low-income families, import tariffs do not affect poverty or income inequality in rural and urban developing countries (Mahadevan et al., Citation2017).

The Republic of Indonesia, Ministry of Trade Data Indonesia, noted that from October 2017, Indonesia’s trade value in 6 ASEAN countries (Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines, Vietnam and Brunei Darussalam) increased. The trend is around 14.43% or $6.289 billion from 2015. The highest trade value between Indonesia and Singapore was recorded at $24.08 billion, with Malaysia at $14.01 billion or growing by 20.4%, Thailand at $13.04 billion or growing by around 10.9%, the Philippines at $6.07 billion or growing 21.89%, and Vietnam at $5.59 billion or continuing to grow 13.36%. However, the trade value between Indonesia and Brunei Darussalam was recorded to have decreased by around 29.37% or $96.1 million. The trend of increasing the value of Indonesia’s trade with ASEAN countries proves that the impact of the US-China trade war has not sufficiently affected the fundamentals of bilateral trade relations in the 6 ASEAN countries.

Reports and analysis published by the Financial Times (England) show that Vietnam is the biggest beneficiary of the trade war, with China-based companies taking action or choosing their production operations abroad and in Vietnam. Meanwhile, Vietnam’s exports to the US were recorded at US$20.7 billion. Vietnam’s economy increased by almost 8% as it became one of the 40 largest exporting countries to the US in the first four months of 2019. Foreign investment and trade growth in Vietnam increased significantly in 2018–2019. The success of economic reform policies since 1986 has supported political stability, and Vietnam is an impact of the US-China trade war. Another fact highlights the obstacles that Vietnam faced during the trade war in maintaining and exploiting its economic opportunities in the future (Iseas, Citation2019).

2.2. Exchange rates and exchange rates are a form of protectionism

US-China relations have been mired in a trade confrontation since March 2018, marked by huge retaliatory tariffs. The experience of failed US trade with Japan over the past 50 years (textiles, steel, automobiles, semiconductors and agricultural products) continues to impact China (Urata, Citation2020). The US implemented a policy of limiting Japanese exports to the US and opening up the Japanese market with its exports. Something similar is now happening in China. US import and export tariff policies to China put pressure on the trade axis between the two countries, which is experiencing bottlenecks, and each country carries out strict trade protection. However, in contrast to Japan, China is considered to have a worse role in US trade. China imposed retaliatory tariffs on US products, and the US also retaliated against Chinese products. The mutual policies of the two countries have created trade uncertainty and have an impact on the entire world’s global trade. The US accusations underlie the country’s security side in the political and economic fields. Meanwhile, China wants to strengthen its financial side on the global stage.

Protectionism leads to protecting the economic welfare of each country. The appreciation of the USD against the target currency and the risk of a global economic downturn due to trade wars might drive changes in exchange rates and dependence between the Chinese Yuan (CNY) and the currencies of major trading partners (Xu & Lien, Citation2020). Meanwhile, in March 2020, residual tariff increases after a one-tier trade deal lowered China’s welfare by 1.7% and the US by 0.2%, with the value of China’s imports and exports to the US decreasing by 49.3% and 52.3%. %, and transfer to respective trading partners (Li et al., Citation2019). Tariff increases and exchange rate appreciation have the same effect on export volume. For Chinese companies, export tariffs and exchange rates aim to maintain the elasticity of their trade scale. Although protectionism poses risks for Chinese companies, rising taxes hinder exports by nearly three times the equivalent exchange rate appreciation (Thorbecke, Chen, & Salike, Citation2021).

2.3. Imposition of tariffs

Tariffs are used to protect goods from abroad entering the country. With a tariff approach, price protection will make local products cheaper than foreign products for the same commodity. This ensures that imports do not disturb local producers. Countries that do not have advantages will depend more on countries with higher competitive advantages. When foreign commodities have an advantage over domestic producers, neither producers nor new entrants can compete with incumbents. Industries with low economies of scale tend to have limited competition, giving rise to imperfect competition, such as monopolistic competition. This situation provides players more advantages to compete with foreign players, gain monopoly power, and earn more profits (Krugman, Obstfeld, & Melitz, Citation2018). The WTO emphasizes the principle of fairness in trade, and this fairness includes the conduct of business without discrimination in any form (Barlow & Stuckler, Citation2021).

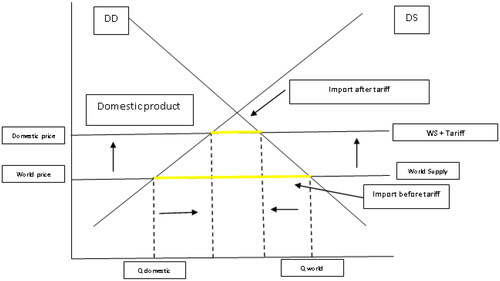

above shows the effect of tariffs on imports, where the DS graph shows domestic supply while the DD shows domestic demand. Domestic consumers will consume goods worth Q world at a lower price because the home country can only produce so much Q domestically and must import goods worth Qw-Qd. When tariffs or other trade barriers are imposed, prices increase, import volumes decrease, and prices rise along with domestic prices. Because prices increase, domestic producers produce Q so that domestic Q moves to the right, and this has the impact of shifting world Q to the left. This mechanism creates a decrease in imports, an increase in domestic production, and higher prices paid by consumers.

Tariffs cause an increase in the price of imported goods. As a result of price increases, domestic producers are not forced to compete directly with competitors on price, so domestic consumers have to pay higher costs. Tariffs also reduce efficiency by allowing firms not in more competitive markets to remain open. Variations in the application of various tariff models have caused tariffs to be used as an instrument capable of regulating the import and export of a commodity. A form of price discrimination where the price of a product or service consists of two parts: lump-sum costs and unit costs (Pindyck & Rubinfeld, Citation2017). Tariff adjustments allow price differentiation in several ASEAN countries with the same commodities.

The existence of import tariffs due to the US-China trade war can affect economic growth and economic prosperity in ASEAN countries. On the other hand, in conditions of free trade and reduced trade barriers, the positive impact is encouraging economic growth. The potential for disruption to economic growth occurs when there are trade barriers in the form of tariffs in trade relations. The Chinese government first created the original innovation concept in 2006 to promote innovation among local businesses (Mankiw, Citation2015).

At the international trade level, countries are assumed to be suppliers or players in the world trade market. This condition makes the world market have a structure similar to the concept of industrial market structure; namely, countries with competitive advantages seem to dominate the market. Countries with superior competitiveness can influence the trade of other trading partner countries, such as ASEAN. Referring to market structure, there is a clause that states that in the case of an oligopoly market structure, old players will depend on several main players, and new players will have difficulty entering the market, especially if their competitiveness is mediocre (Cominetti et al., Citation2009). And some possible interactions between the main players in the market may lead to tighter dominance.

2.4. Market structure

The trade war provides evidence of the large influence of policy uncertainty on economic activity and the importance of agreements to reduce it (Handley & Limão, Citation2017). Political and policy uncertainty regarding the direction of trade policy is starting to impact trade growth (Pangestu, Ing, & Hadiwidjaja, Citation2018). The trading system is on the verge of market imperfection. The increasing bilateral and international trade imbalance due to the US-China trade war has harmed global and Asian markets. Management of free trade tariffs causes changes in monopoly and oligopoly market structures. Meanwhile, reduced trade between the US and China in 2018 and 2019 had trade consequences for both countries by shifting their business to East Asian countries. Weakening economic and geopolitical relations have forced both countries to carry out policies to restructure value chains in the region. The trend brings new deals into the market structure and requires the adaptation of trading model solutions.

The solution to the Cournot model is that in the long run, prices and output will be stable and stable without any tendency to change production or prices. In the context of countries in the Cournot model, there are n countries that produce (and, in this context, export) to maximize their trade profits. With this assumption, states are denoted i with the number of states i = n. The country exports q i > 0 for sale and incurs costs c i (q i). The Cournot model provides a clearer picture of interactions in terms of output. The model shows that price, in most cases, will not equal marginal cost. This difference causes Pareto efficiency not to be achieved. In addition, the extent to which a company’s price exceeds its marginal cost is directly proportional to its market share and inversely proportional to the elasticity of market demand (Khemani & Shapiro, Citation1993). In the context of a country, a representation of how another country might absorb one country’s products can at least show how assumptions built on costs reflect lower prices. This means importing countries have lower competitiveness (in cost or price competition) than exporting countries. Thus, as the number of firms increases, the equilibrium approaches what would occur in a perfect match (Perry, Citation1984). General equilibrium analysis applies to small, open economies with economies of scale and imperfect competition (Harris, Citation1984).

Short-term and long-term impacts of a prolonged trade war in different market scenarios in the ASEAN Region (describing tariffs imposed by the US and China). Trade wars in the free trade market are no longer based solely on the relationship between the two countries but rather on fraudulent agreements that lead to an oligopoly market pattern. Considering that the ASEAN market is a combination of large growth in developing countries in Asia, the two countries (US and China) have other assumptions to strengthen and unlock their great potential in ASEAN, US-Singapore and China-Vietnam. Market. Both countries maximize each other by setting import tariffs and export taxes. Nash equilibrium in trade policy results in each country gaining prosperity. However, there is an asymmetry of costs compared to unlimited Nash profits. In that case, trade can only be sustained temporarily and repeatedly, although countries with uncompetitive firms may benefit if the asymmetry is large enough (Collie, Citation2019) and the dynamic scenario of heterogeneity between players affects the stability properties of the Cournot-Nash equilibrium (Cerboni Baiardi & Naimzada, Citation2019).

n -the firm is assumed to have a limited budget to cover production costs (assumed no product differentiation). If production costs exceed the budget, the company must borrow additional unit costs and carry out a more complex balance analysis or adjust production costs. Countries whose companies have minimal budgets due to the US-China trade war will have their production targets disrupted for their export needs, while the import tariffs imposed on products will result in companies needing help to meet their production of finished goods. This condition impacts the value and production costs, which are quite high while meeting the needs of the global trade market, which is experiencing uncertainty (additional import and export tariffs). The market structure has become unhealthy, and the trade policies of the warring countries have created economic pressure to become capitalist, and this has had an impact on the trade market in ASEAN. In response to the imposition of tariffs on China’s average exports increased by 20% from 8%, and import tariffs decreased by 6% from 8% in 2020, while the US import tariff policy against China from 7% increased by 2.5% (Bown, Citation2021). The impact of long-term tariff barriers on the ASEAN market gives rise to the assumption that the two countries are carrying out a collusive oligopoly trade scheme to secure their trade in the ASEAN region. Finally, the ASEAN trade market is indirectly predicted in this study to be pragmatic in the systemic collusive oligopoly trade tariff scheme resulting from the US-China trade war.

3. Research methodology

This research analyzes the market structure before and after the US-China trade war using Concentration 5 and the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index. The aggregate market share of the leading n-firms in the market is represented by the n-firm concentration ratio, which is a general indicator of market structure. The Herfindahl–Hirschman Index is used to measure market concentration. As concentration increases, industry performance increasingly deviates from the structure of perfect competition.

3.1. Source of research data

This research data was taken from the International Trade Center (Intracen) in collaboration with UNCTAD and the WTO World Bank Group. This database is accessed at trademap.org. The data includes exports and imports involving the US and China, with other countries for comparison for various times set in 2018 and 2020. The countries selected based on actual trade war events and important ASEAN partner countries are China, the US, Japan and South Korea ().

Table 1. Concentration level.

3.2. Measurement of the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI)

Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) is a concentration index that describes the extent to which companies dominate the market for a commodity. In this research, the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) approach is used in the context of a country to determine the extent to which the two countries dominate the ASEAN market.

Where is the company’s export share (in the country context), i and N are the number of companies (in the country context). The Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) Index then classifies the range of Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) values to see how a country’s concentration in the world market refers to the United States Trade Commission and is announced by Esquivias et al. (Citation2020). An overview of the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) formulation from the initial formula is as follows:

The quadratic method can show how big the market share of each square is. This logic makes the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) value look large, especially if the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) is calculated using a non-percentage approach. The HHI score is then compared with the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) classification value, which is explained in below to see the extent to which a few players dominate the market.

Table 2. Classification of Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) values.

According to Shepherd and Shepherd (Citation2003), the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) focuses on certain large market shares within an industry. As an indicator to determine the level of competition, grouping is carried out based on the highest sales ranking to be categorized based on structure and behavior. The Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) results have a pattern identical to the ratio analysis that approaches the concentration.

An analytical instrument used to gauge an industry’s degree of market concentration is the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (IHH). The Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (IHH) gauges how much a few enterprises control a specific market. The squares of the market shares of each company in the industry are added to determine this index. The Herfindahl–Hirschman Index’s Significance in Market Structure Analysis. Measuring Market Concentration: An industry’s Level of market concentration can be estimated using the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (IHH). The degree of market concentration increases with a more excellent value of the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (IHH), and vice versa. Finding the Potential for Oligopoly or Monopoly: The Herfindahl–Hirschman (IHH) Index can be used to determine whether a market structure is more likely to be oligopolistic—dominated by a small number of major companies—or monopolistic—dominated by a single enterprise. Measuring the Level of Competitiveness: The industry’s Level of competitiveness is inversely correlated with the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (IHH) score. On the other hand, a low Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (IHH) number denotes more competitiveness.

Important for Regulators and Supervisors: Regulators and supervisory bodies frequently use this index to track the degree of competition and spot possible problems that could hurt consumers. Causes of the Trade War-Related IHH Uptrend: Trade wars have the potential to cause industry consolidation, in which smaller businesses may encounter challenges or be compelled to amalgamate in order to weather unpredictable economic conditions. Entrance Barriers: Trade conflicts have the potential to raise obstacles to entrance for new businesses, which may result in a concentration of the market. Alliances and Collusion: In order to maintain their market share, businesses may be more likely to establish alliances or participate in collusive tactics as a result of the effects of trade wars and economic uncertainty.

4. Results and discussion

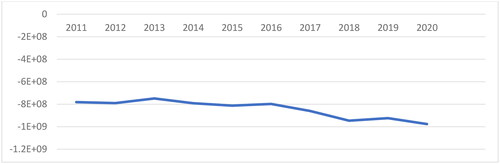

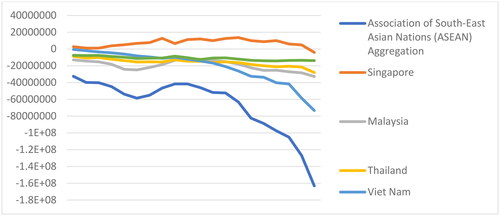

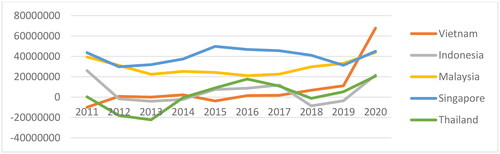

From data from 2011 to 2020, which is shown in below, It can be seen that after 2018 or the start of the US-China trade war, there was an increase in the Trade Balance (BoT) in 5 ASEAN countries (Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand). Vietnam experienced the most significant growth since 2018; this increase is initial evidence of how Vietnam benefits from this trade war.

Figure 3. Trade balance of Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand 2011–2020 Source: Data extracted and processed from Trademap https://www.trademap.org/.

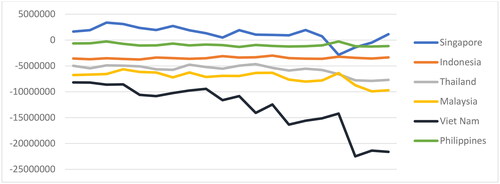

Analyze industry strength in dominating the market using C5 analysis. This research uses secondary data from the trademap.org database. The C5 analysis () shows an increase in the concentration of 5 ASEAN importing countries from 2017 to 2020. In 2017, the attention of these five countries accounted for 49.87% of ASEAN imports. The import share value of C5 countries increased 3.57%–53.3%. China and US market shares rose by 3% and 0.3%, respectively. Taiwan’s market share with ASEAN also increased by 1.1%. Meanwhile, ASEAN’s other trading partners, Japan and South Korea, weakened 0.9% and 0.2%, respectively. The results obtained indicate an oligopoly market structure.

Table 3. Analysis results of C5 ASEAN trading partner countries.

This research shows that markets do not function as neoclassical economics textbooks indicate once they have stabilized. Rather, they function inside intricate and systemic institutions like oligopolies. An oligopoly occurs when a few interdependent players control the market and exert influence over others by their decisions and deeds. A landmark work in this area (Stigler, Citation1964), ‘The Theory of Oligopoly’ emphasizes the strategic relationships between companies in an oligopolistic market. The results demonstrate how market structures are related to established economic theories like individual rationality and price-based market behavior within a broader system. Businesses operating in oligopolistic markets are nonetheless logical players, looking to maximize profits while taking their rivals’ moves and responses into account. The study highlights how crucial it is for market participants to engage strategically and how important it is to take power into account in oligopoly marketplaces.

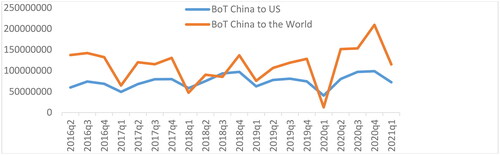

Regarding China’s response in response to what the US did, China’s trade was not too affected. The pattern formed matches the two charts for the US and world trading partners. This concordance indicates that the trade war has no impact on China’s overall trade. The minimal effect of the trade war on China’s BoT shows that with the implementation of high barriers by the US, China can still improve its export performance. shows how China’s BoT stacks up against the US and China’s BoT stacks up against the world.

In the trade war that occurred in the first and second quarters of 2018, from the US perspective, the trade balance showed a pattern similar to the US trade balance towards the world. However, the US BoT chart shows a decline in net imports after 2018, which means the US benefited from the trade war by reducing its implications for China. shows the decrease in the trade deficit after 2018. This decline in the debt is a signal that the trade war waged by the US was able to reduce the US trade deficit with China. The advantage is that there has been a decline in the US trade balance with the world, even though the net BoT decreased significantly in the first quarter of 2021.

In addition, the overall US Trade Balance did not improve after the imposition of several tariffs from China but worsened the US trade balance. shows that the US BoT has decreased, and there is evidence that implementing US tariffs on China does not improve the US BoT. Initial evidence that the US does have a mission to reduce dominance and imports from China.

shows that the value of US exports to China has decreased, but the more significant decline in imports shows that this trade war effectively reduces US dependence on China.

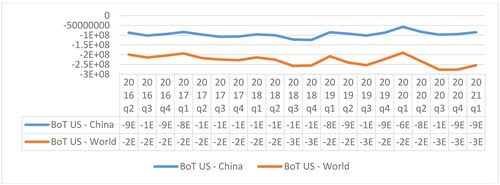

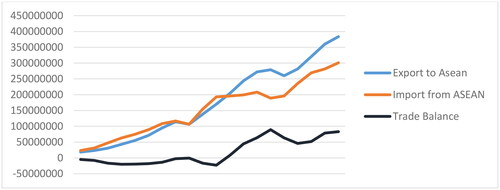

From 2016 to 2021, the US will make net imports from ASEAN. shows the US BoT towards ASEAN and 5 ASEAN countries in 2001–2020, showing that net imports from the US increased sharply after 2018, and this sharp increase is evidence that there has been a shift in imports from China, one of which is to ASEAN countries.

China’s export growth has slowed down due to the US-China trade dispute. The US has slapped tariffs on many Chinese items, increasing the cost of those goods for US customers and decreasing their ability to compete in the US market. China’s export industry may suffer, particularly in sectors where tariffs are directly felt. The taxes imposed by the US impact China’s imports. Some US businesses might go outside of China to get around rising tariffs for substitute suppliers. Companies may also buy or manufacture domestic goods to lessen their reliance on imports from China. Trade dynamics between the US and China can be significantly impacted by changes in trade policy, particularly when it comes to agreements or discussions between the two countries.

In terms of aggregate US BoT to ASEAN countries, there has been a significant increase in net imports to several ASEAN countries in the last ten quarters. After 2018, it can be seen that the US BoT towards Vietnam has increased significantly. Vietnam’s geographic location close to China, as well as commodities that can be substituted from China by Vietnam, is one reason Vietnam has benefited from the ongoing trade war. shows the US BoT against 6 ASEAN countries from the second quarter of 2016 to the first quarter of 2021.

Several essential elements contributed to Vietnam’s economic development that may be used to explain the country’s economic growth following the commencement of the trade war between the US and China. Many businesses have started to relocate their manufacturing bases from China to other nations to avoid tariffs and reduce risks due to the US-China trade conflict. Vietnam is among the top options due to its rising infrastructure and cheap labor prices. Vietnam’s economic growth has benefited from this production relocation. Vietnam has successfully grown the amount of goods it exports, particularly in the manufacturing industry. Production was transferred, which enhanced Vietnam’s ability to export goods and raised national income.

Furthermore, Vietnam has successfully utilized free trade agreements with several nations and areas, including the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement, which promotes the expansion of exports. Significant FDI inflows have resulted from growing investor confidence in Vietnam as an investment destination. The pro-business policy reforms of the Vietnamese government, which aim to improve the business environment, support this requirement. The Vietnamese government is crucial in this regard since it prioritizes infrastructure development and raises the standard of human resources via education. As a result, there is a solid basis for future growth and higher economic competitiveness. After the US-China trade war began, Vietnam’s economy expanded due to several factors, including shifting production, rising exports, foreign investment, and government backing for the construction of infrastructure and educational programs. These elements work together to produce an environment that fosters the nation’s significant economic growth.

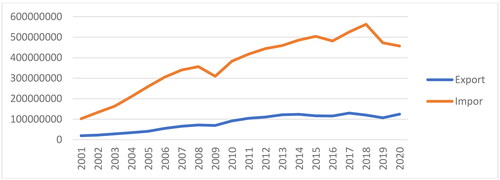

China’s export performance to ASEAN is quite promising. Trade the balance from 2001 to 2009 shows a balanced relationship between exports and imports from China. After 2009, China’s trade performance with ASEAN tended to improve significantly. This increase can be seen from the rise in the value of China’s exports and imports to ASEAN each year. China, a country geographically located in the north of ASEAN, can play its role as an economic giant in carrying out more intense trade relations with ASEAN. Regional trade agreements with countries in the AFTA region also drive this trade. shows China’s trade performance with ASEAN from 2001 to 2020.

The empirical findings’ conclusions are connected to economic theory, which explains why Indonesia’s trade improvements were negatively impacted by the trade diversion that resulted from the US-China trade war. This condition affects the competitiveness of domestic industries, which in turn affects how competitive these industries are and how much they produce. According to the general equilibrium theory, the economy is not affected at this point. Welfare for households is impacted by consumption as well as income. The demand for labor and the capital needed for manufacturing rises or falls in tandem with the output of a given industry. He will alter the costs of the components of production, which will have an impact on real returns on capital and real salaries for both skilled and unskilled labor. The distribution of household income among income categories is subsequently altered as a result. Ultimately, there will be a change and an increase in the poverty rate ().

The empirical results of this study inform the policy of ASEAN nations about economic development. The empirical results show that a trade war can only do minor damage in terms of increasing the concentration of competing countries in their trading partner countries. Thus, the US campaign messaging (Trump) was a political access at the start of the trade war. The Herfindahl–Hirschman Index’s empirical results show that there needs to be a concentration of import players in ASEAN. On the other hand, the Herfindahl–Hirschman index, which often indicates an oligopoly market structure, increased following the trade war. The ASEAN market area was larger a year before the trade war, according to the findings of the C5 Analysis of ASEAN Trading Partner Countries and the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index. The C5 Index demonstrates that market concentration was modest both before and after the US-China trade war, which contributed to a rise in the C5 Analysis Results of ASEAN Trading Partner Countries.

For US businesses importing goods from China, tariffs levied by the US on Chinese imports raise import costs. Businesses may decide to increase product pricing or look for suppliers outside of China in order to pass on these higher expenses to customers. According to some analyses, Chinese shipments to the US have decreased across a number of industries, particularly those that are immediately impacted by the tariffs. To get around tariffs, some businesses might look for alternatives to the global supply chain, like shifting production to nations with lower tariffs. But keep in mind that these effects might differ based on the economic sector, and certain businesses might be able to modify their tactics to lessen the effects of tariffs. The trade and economic landscape may shift over time, and the United States’ tariff policy towards China may have also changed or been revised.

Utilizing the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI), one can gauge how concentrated a market or sector is. Following the trade war, a rise in HHI might indicate a tendency toward an oligopoly market structure and increasing market concentration. An oligopoly occurs when a few major enterprises control a large portion of the market. Large market-dominating corporations may give their nations a competitive edge when influencing legislation and supply management. This could lead to disparities in the economic gains of ASEAN nations. Oligopolies can erect significant entry barriers for new businesses, hindering innovation and competition. This may hamper the expansion of small and medium-sized businesses from ASEAN members need to be improved. In the context of international trade, firms operating in an oligopoly structure may be able to engage in collective negotiations. As a result, ASEAN members may be better positioned to influence trade policy and negotiate with trading partners. It is crucial to remember that the effects of an oligopoly market structure differ based on a wide range of variables, such as the particular industry sector, the degree of economic integration, and governmental policies.

5. Conclusion

Market shifts occurred in the year following the outbreak of the trade war but were concentrated in just a few players. The empirical findings show that, in reality, trade wars do not cause much harm in terms of increasing the concentration of competing countries in their trading partner countries. In the beginning, the trade war was due to political access due to US (Trump) campaign propaganda. Meanwhile, the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index value provides empirical evidence that there is no concentration of import players in ASEAN. However, after the trade war, there was an increase in the Herfindahl–Hirschman index, which tends to have an oligopoly market structure. Index Result of C5 Analysis of ASEAN Trading Partner Countries and the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index provides empirical evidence that a year before the trade war occurred, the market area in ASEAN was slightly more comprehensive. The C5 Analysis Results Index for ASEAN Trading Partner Countries provides empirical evidence that before the US-China trade war and after the trade war, market concentration was at a moderate level and caused an increase in the value of the C5 Analysis Results for ASEAN Trading Partner Countries.

6. Research implication

This research has several implications for economics theory, practice and policy formulation. This research provides theoretical and practical implications: It provides empirical evidence in the economic field of ASEAN countries. Based on these empirical findings, it is supported by the concept of the Impact of Import Tariffs from the US-China Trade War on the ASEAN Region, Exchange Rates, and Exchange Rates Are a Form of Protectionism, Tariff Imposition, and Market Structure.

The results of this research provide input for economic development in ASEAN countries. The empirical findings show that, in reality, trade wars do not cause much harm in terms of increasing the concentration of competing nations in their trading partner countries. The start of the trade war was political access due to US (Trump) campaign propaganda. Herfindahl–Hirschman’s empirical findings The index shows no concentration of import players in ASEAN. Still, after the trade war, there has been an increase in the Herfindahl–Hirschman index that tends to an oligopoly market structure. Results of C5 Analysis of ASEAN Trading Partner Countries and Herfindahl–Hirschman The index shows that a year before the trade war occurred, the market area in ASEAN was slightly wider. The C5 index shows that before the US-China trade war and after the trade war, market concentration was at a moderate level and led to an increase in Results of the C5 Analysis of ASEAN Trading Partner Countries.

7. Limitations research

The limitations of this research include how trade is carried out by two countries experiencing a trade war and looking at it only at total transactions (exports and imports). In the future, it is necessary to conduct research that directly covers the commodity level to examine which commodities are concentrated because this research only covers the aggregate trade level. To prevent possible dependency and lead to a systemic collusive oligopoly trade structure, ASEAN must not depend solely on these countries and needs to increase cooperation with new and potential partner countries, such as Latin America and Africa. With a more intensive and comprehensive partnership, the concentration of ASEAN trading partner countries can be further reduced and lead to the creation of fair and mutually beneficial relations between countries.

Authors contribution

IMH, R performed conceptualization, supervision, and validation; PP handled the methodology and formal analysis. MAE focuses on investigation, data curation, and original drafting. IY, R did the writing—review and editing. All authors have read and approved the published version of the manuscript.

Thank you note

The author is grateful to the Editor, and anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ignatia Martha Hendrati

Ignatia Martha Hendrati is an associate professor in Development Economics Department, National Development University ‘Veteran’ East Java, Indonesia. She teach international trade. Her research interests are economics, public policy.

Miguel Angel Esquivias

Miguel Angel Esquivias is a lecturer and researcher at Airlangga University. He has published and reviewed various articles in indexed journals WoS and Scopus.

Putra Perdana

Putra Perdana is lecturers at the Development Economics Department, National Development University ‘Veteran’ East Java, Indonesia. His research interests are international trade, economics.

Indrawati Yuhertiana

Indrawati Yuhertiana is a professor of public sector accounting at the National Development University ‘Veteran’ East Java, Indonesia. He has published and reviewed various articles in indexed journals Scopus. He teaches seminars on public policy, public sector accounting and budgeting. His research interests are behavioral accounting.

Rusdiyanto Rusdiyanto

Rusdiyanto is an Assistant Professor accountancy behavior at Gresik University Indonesia. He has publish and review various articles in journals Scopus indexed. He teaching accounting seminars behavior. Interest his research is accountancy behavior.

Reference

- Bai, S., & Koong, K. S. (2018). Oil prices, stock returns, and exchange rates: Empirical evidence from China and the United States. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance, 44, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.najef.2017.10.013

- Barlow, P., & Stuckler, D. (2021). Globalization and health policy space: Introducing the WTOhealth dataset of trade challenges to national health regulations at World Trade Organization, 1995–2016. Social Science & Medicine, 275, 113807. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113807

- Bekkers, E., & Schroeter, S. (2020). An economic analysis of the US-China trade conflict. World Trade Organization.

- Bekkevold, J. I. (2020). The international politics of economic reforms in China, Vietnam, and Laos. In A. Hansen, J. I. Bekkevold, & K. Nordhaug (Eds), The socialist market economy in Asia (pp. 27–68). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-6248-8_2

- Bown, C. P. (2021). The US–China trade war and phase one agreement. Journal of Policy Modeling, 43(4), 805–843. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpolmod.2021.02.009

- Cerboni Baiardi, L., & Naimzada, A. K. (2019). An oligopoly model with rational and imitation rules. Mathematics and Computers in Simulation, 156, 254–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matcom.2018.09.005

- Che, Y., Lu, Y., Pierce, J. R., Schott, P. K., & Tao, Z. (2022). Did trade liberalization with China influence US elections? Journal of International Economics, 139, 103652. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2022.103652

- Chin, K. F. (2023). Malaysia in changing geopolitical economy: Navigating great power competition between china and the United States. The Chinese Economy, 56(4), 321–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/10971475.2022.2136697

- Chong, T. T. L., & Li, X. (2019). Understanding the China–US trade war: causes, economic impact, and the worst-case scenario. Economic and Political Studies, 7(2), 185–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/20954816.2019.1595328

- Chou, C.-H., Shrestha, S., Yang, C.-D., Chang, N.-W., Lin, Y.-L., Liao, K.-W., Huang, W.-C., Sun, T.-H., Tu, S.-J., Lee, W.-H., Chiew, M.-Y., Tai, C.-S., Wei, T.-Y., Tsai, T.-R., Huang, H.-T., Wang, C.-Y., Wu, H.-Y., Ho, S.-Y., Chen, P.-R., … Huang, H.-D. (2018). miRTarBase update 2018: a resource for experimentally validated microRNA-target interactions. Nucleic Acids Research, 46(D1), D296–D302. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkx1067

- Collie, D. R. (2019). Trade wars under oligopoly : Who wins and is free trade sustainable ? Cardiff University.

- Cominetti, R., Correa, J. R., & Stier-Moses, N. E. (2009). The impact of oligopolistic competition in networks. Operations Research, 57(6), 1421–1437. https://doi.org/10.1287/opre.1080.0653

- Dorsey, J. M. (2019). Trump’s Trade Wars: A New World Order?. Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies. Mideast Security and Policy Studies No. 166. http://www.jstor.com/stable/resrep24339

- Dullien, S. (2018). Shifting views on trade liberalisation: Beyond indiscriminate applause. Intereconomics, 53(3), 119–124. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10272-018-0733-8

- Esquivias, M. A., & Harianto, S. K. (2020). Does competition and foreign investment spur industrial efficiency?: Firm-level evidence from Indonesia. Heliyon, 6(8), e04494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04494

- Fetzer, T., & Schwarz, C. (2021). Tariffs and politics: Evidence from Trump’s trade wars. The Economic Journal, 131(636), 1717–1741. https://doi.org/10.1093/ej/ueaa122

- Grundke, R., & Moser, C. (2019). Hidden protectionism? Evidence from non-tariff barriers to trade in the United States. Journal of International Economics, 117, 143–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2018.12.007

- Handley, K., & Limão, N. (2017). Policy uncertainty, trade, and welfare: Theory and evidence for China and the United States. American Economic Review, 107(9), 2731–2783. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20141419

- Harris, R. (1984). Applied General Equilibrium Analysis of Small Open Economies with Scale Economies and Imperfect Competition. The American Economic Review, 74(5), 1016–1032. http://www.jstor.org/stable/559

- Henry, S., & Milovanovic, D. (1996). Constitutive criminology.

- Iseas, R. A. T. (2019). The US-China trade war : Impact on Vietnam. (Vol. 102, pp. 1–13). ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute.

- James, H. (2013). Growing stronger: What way out for Europe? CESifo Forum, 14(3), 35–43.

- Khemani, R. S., & Shapiro, D. M. (1993). An empirical analysis of Canadian merger policy. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 41(2), 161–177. https://doi.org/10.2307/2950434

- Krugman, P. R., Obstfeld, M., & Melitz, M. J. (2018). International economics: Theory and policy. (11th ed.). Princeton University.

- Kwan, C. H. (2020). The China–US trade war: Deep-rooted causes, shifting focus and uncertain prospects. Asian Economic Policy Review, 15(1), 55–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/aepr.12284

- Li, M., Balistreri, E. J., & Zhang, W. (2019). The U. S. – China trade war : tariff data and general equilibrium analysis. Journal of Asian Economics, 69, 101216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asieco.2020.101216

- Mahadevan, R., Nugroho, A., & Amir, H. (2017). Do inward looking trade policies affect poverty and income inequality? Evidence from Indonesia’s recent wave of rising protectionism. Economic Modelling, 62, 23–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2016.12.031

- Mankiw, B. N. G. (2015). Economists actually agree on this : The wisdom of free trade. New York Times.

- Mavroidis, P. C., & Sapir, A. (2021). China and the WTO: why multilateralism still matters. Princeton University Press.

- McCallum, B. T. (1983). A reconsideration of Sims’ evidence concerning monetarism. Economics Letters, 13(2-3), 167–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1765(83)90080-0

- Nugroho, A., Irawan, T., & Amaliah, S. (2021). Does the US–China trade war increase poverty in a developing country? A dynamic general equilibrium analysis for Indonesia. Economic Analysis and Policy, 71, 279–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eap.2021.05.008

- Pangestu, M. (2019). China–US trade War: an Indonesian perspective. China Economic Journal, 12(2), 208–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/17538963.2019.1611084

- Pangestu, M., Ing, L. Y., & Hadiwidjaja, G. (2018). The future of East Asia’s Trade: A call for better globalization. Asian Economic Policy Review, 13(2), 219–238. https://doi.org/10.1111/aepr.12220

- Perry, M. K. (1984). Scale economies, imperfect competition, and public policy. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 32(3), 313. https://doi.org/10.2307/2098020

- Pindyck, R., & Rubinfeld, D. (2017). Microeconomics (9th ed.). Pearson.

- Sheldon, I. M., Chow, D. C. K., & McGuire, W. (2018). Trade liberalization and constraints on moves to protectionism: Multilateralism vs. Regionalism. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 100(5), 1375–1390. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aay060

- Shepherd, W. G., & Shepherd, J. M. (2003). The economics of industrial organization. Waveland Press.

- Stigler, G. J. (1964). A theory of Oligopoly. Journal of Political Economy, 72(1), 44–61. https://doi.org/10.1086/258853

- Thorbecke, W., Chen, C., & Salike, N. (2021). China’s exports in a protectionist world. Journal of Asian Economics, 77, 101404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asieco.2021.101404

- Tu, X., Du, Y., Lu, Y., & Lou, C. (2020). US-China trade war: Is winter coming for global trade? Journal of Chinese Political Science, 25(2), 199–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-020-09659-7

- Urata, S. (2020). US–Japan trade frictions: The past, the present, and implications for the US–China trade war. Asian Economic Policy Review, 15(1), 141–159. https://doi.org/10.1111/aepr.12279

- Xu, Y., & Lien, D. (2020). Dynamic exchange rate dependences: The effect of the U.S.-China trade war. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 68, 101238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intfin.2020.101238

- Žemaitytė, S., & Urbšienė, L. (2020). Macroeconomic effects of trade tariffs: a case study of the US-China trade war effects on the economy of the United States. Organizations and Markets in Emerging Economies, 11(22), 305–326. https://doi.org/10.15388/10.15388/omee.2020.11.35

- Zheng, J., Zhou, S., Li, X., Padula, A. D., & Martin, W. (2023). Effects of eliminating the US–China trade dispute tariffs. World Trade Review, 22(2), 212–231. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474745622000271