Abstract

This study investigates the relationship between internal audit function quality, Chief Executive Officer (CEO) power and earnings quality and how CEO power moderates the relationship between internal audit function quality and earnings quality. The study is correlational, cross-sectional, and perception-based that obtained 136 usable questionnaires from regulated firms in Uganda. Data was analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Scientists, Smartpls software, and Jose’s Modgraph. The results show that internal audit function quality is positive but not significantly related to earnings quality. The results revealed that internal audit function quality is negatively related to CEO power although the association is not significant. CEO power is significant and negatively related to earnings quality. The interaction effects of internal audit function quality and CEO power on earnings quality are significant, according to which the greater the power of the CEO, the lower the effect of the IAF on earnings quality. The current study adds to literature of internal audit function quality, CEO power and earnings quality and consequently, moderating role of CEO power in the relationship between internal audit and earnings quality. This study is relevant to policy makers and regulators who need to consider these results to identify the needed changes in their regulation of accounting practice and governance in Uganda.

1. Introduction

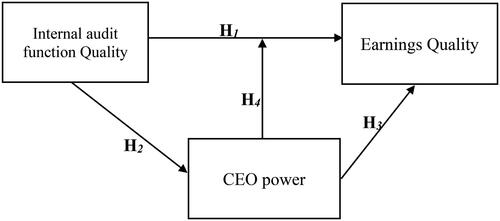

This paper aims to investigate the relationship between internal audit function quality (IAFQ), CEO power, and earnings quality (EQ), as well as the moderating role of CEO power in the relationship between internal audit function quality and earnings quality. In trying to do this, the current study specifically aims to address four research concerns. First, what is the relationship between internal audit function quality and earnings quality? Second, what is the relationship between internal audit function quality and CEO power? Third, what is the relationship between CEO power and earnings quality? Fourth, how does CEO power moderate the relationship between internal audit function quality and earnings quality?

Earnings quality are important to stakeholders because they serve as a foundation for decision-making, allow firms to secure funding, permit nations to draw in inexpensive capital, and guarantee effective resource allocation (Aggarwal et al., Citation2005; Dechow et al., Citation2010; Demerjian et al., Citation2013; Francis et al., Citation2008). Despite the importance of EQ, low-quality profits have continued to be a growing source of worry globally. For instance, Hertz Global Holdings, overstated transactions worth US$ 7.4 billion (PWC Report, Citation2019), Steinhoff firm overstated its pre-tax income worth US$ 235 million (SEC, Citation2019), and FTE Networks inflated its revenues by as much as 108% (SEC, Citation2021) among others. The phenomenon of doubtful earnings is also apparent in Uganda. Successive reports have adduced evidence in this direction (PriceWaterhouse Coopers Limited Nyonyi Report, Citation2016; HFB Audited Annual Reports, 2018; The Ogoola Judicial Commission Report-Government of Uganda, 2000; Mugisha, Citation2019). When the quality of earnings is doubted, it shines a spot light on the relevance of information contained in financial statements as a basis for decision making, and reduces their financial probity (Jouber & Fakhfakh, Citation2011).

Majority of the studies on earnings quality employed agency theory (Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976) perspective (see, Ismael & Kamel, Citation2021; Alzoubi, Citation2019; Melgarejo, Citation2019; Egbunike & Odum, Citation2018; Hashmi et al., Citation2018; Faricha, Citation2017; Hessayri & Saihi, Citation2015; Demerjian et al., Citation2013; Lyengar et al., Citation2010). However, these studies produce consistent results only in the context of developed capital markets where the major stakeholder is the shareholder. For instance, Ismael and Kamel (Citation2021) reported that internal audit quality is negatively associated with abnormal accruals. Similarly, Alzoubi (Citation2019) also concluded that internal audit function reduces discretionary accruals. But, in environments such as Uganda, where capital markets are not developed, agency perspective is less likely to be effective. From the stakeholder identification and salience (Mitchell et al., Citation1997) theory, there are several stakeholders who are interested in earnings quality. In this study, we consider a firm’s CEO to be a key internal stakeholder in less developed markets, where markets for control are weak. In the presence of such a powerful CEO, it is most likely that earnings quality will be low. Kalembe et al. (Citation2023) present empirical evidence that CEO power is negatively associated with earnings quality. Therefore, managerial incentives for poor earnings quality potentially mirror stakeholder attributes such as power to influence the firms’ outcomes (Cai & Mehari, Citation2015; Mitchell et al., Citation1997).

Existing empirical studies (Rezaee & Safarzadeh, Citation2022; Nalukenge et al., Citation2022; Kawaase et al., Citation2021; Elzahaby, Citation2021; Melgarejo, Citation2019; Abbott et al., Citation2016; Ege, Citation2015; Prawitt et al., Citation2009) present positive effects of internal auditing on earnings quality (management). Rezaee and Safarzadeh (2023) reported that internal audit improves EQ. Similarly, Elzahaby (Citation2021) stresses that internal audit function improves firm performance of Egyptian Listed firms. Melgarejo (Citation2019) argues that internal audits provide accounting reports that are more value-relevant, persistent, and conservative. Also, Prawitt et al. (Citation2009) concluded that internal audit quality is negative and significantly related to absolute abnormal accruals. Other studies (Lee et al., Citation2022; Baker et al., Citation2019; Jiang et al., Citation2010) documented a relationship between CEO power and earnings quality. For instance; Baker et al. (Citation2019) revealed that earnings management is greater when a CEO is powerful. Relatedly, Lee et al. (Citation2022) reported that powerful CEOs amplified earnings management in Vietnamese Listed companies. Majority of these studies were carried out in developed countries and, moreover, only tested for direct effects. Studies such as Nalukenge et al. (Citation2022) and Kaawaase et al. (Citation2021) were carried out in Uganda, but their focus was on specific industries such as statutory corporations and financial services firms respectively. But, how CEO power affects a firm’s financial reporting strategies’ outcomes such as earnings quality is rarely discussed in the corporate governance, management or accounting literature. Powerful CEOs tend to create an opaque accounting environment that limits disclosure of accurate earnings. As a result, low EQ is reported. Yet with the presence of a quality internal audit function, it is expected that such tendencies will be mitigated, because internal audit monitors the opportunistic behavior of the CEO. We, therefore, expect powerful CEOs to moderate the link between IAFQ and EQ, if earnings are to be enhanced. Further, despite the numerous studies on corporate governance and its impact on EQ being documented, little is known about the interplay of CEO power and internal audit function quality on earnings quality. This study therefore intends to fill this void in existing literature.

Other studies that try to address EQ adopt event study methodology (e.g. Faricha, Citation2017; Dutillieux et al., Citation2016) and have been informative but limited in application because the wealth effects of regulatory changes can be difficult to detect (Mackinlay, Citation1997). In the absence of the event or robust stock market model, other factors explaining earnings quality remain unearthed. Already, Athari and Bahreini (Citation2021, Athari, Citation2022a) indicate that profitability is shaped by, among others, context, including country-level governance quality (Athari, Citation2022b), and generally, context offers insights into decisions relating to earnings (Athari et al., Citation2016). Still, many studies measure EQ using different proxies such as Jones model of discretionary accruals, modified Jones model, and performance-matched discretionary accruals (Hashmi et al., Citation2018), earnings restatement, earnings persistence, errors in bad debt provision and mapping of accruals into cashflows (Demerjian et al., Citation2013), abnormal accruals and timely loss recognition (Dutillieux et al., Citation2016). The problem with the accrual component is its failure to accurately indicate the real driver of opportunism and failure to address directly perceived EQ that mirrors the behavior of users (Dechow & Dichev, Citation2002; Healy & Wahlen, Citation1999). This is contrary to the Framework for Financial Reporting 2018 that addresses quality in terms of qualitative characteristics of financial statements (information). Unlike previous studies (e.g. Rezaee & Safarzadeh, Citation2022) on earnings quality, which recommend a comprehensive earnings quality model (which includes all different aspects of this construct), we utilize the theoretical framework of financial accounting 2018, specifically the fundamental qualitative characteristics of relevance and faithful representation to measure earnings quality. As such, we aim to capture the perceptions of stakeholders on earnings quality using the above-mentioned measures because perception-based studies provide managerial motivations for improving earnings quality (Belal & Owen, Citation2007).

Consequently, the current research seeks to make the following contributions to existing literature. First, this study adds to existing literature by documenting the relationship between internal audit function quality, CEO power and earnings quality in Uganda. Second, the study articulates the moderation effect of CEO power in the relationship between internal audit function quality and earnings quality. This is because available studies (e.g Rezaee & Safarzadeh, Citation2022; Lee et al., Citation2022; Elzahaby, Citation2021) investigated the direct relation between internal audit and earnings quality, ignoring the role of a third variable-CEO power as a moderator in the Ugandan context. Third, this study uses a multi-theoretical approach to understand earnings quality in a developing country like Uganda. It is evident that previous studies (e.g Ismael & Kamel, Citation2021; Alzoubi, Citation2019; Melgarejo, Citation2019) used a single theory; which may not adequately explain EQ. The findings provide clear policy implications to the regulators and standard setters who may need to ensure that firms comply with international financial reporting standards in order to report high earnings quality.

The next section of the paper includes a study setting, theoretical literature review, empirical literature review and hypotheses development, research design, empirical results and discussion, and summary and conclusion.

2. Background

Uganda is a developing landlocked country lying on the equator in East Africa. Uganda gained independence in 1962 from the British colonialists but thereafter suffered civil wars and political unrest (Nkundabanyanga et al., Citation2013). The country is endowed with substantial resources, including fertile soils, regular rainfall, copper, gold, cobalt and the recently discovered oil reserves. The main exports are coffee, fish, flowers, horticultural products, minerals, tobacco and tea, making it an investment hub (Uganda National Investment Policy, Citation2018). With the Country’s industrial and trade policy in place, there has been a robust flow of investors into the country who have invested in different sectors given its favorable investment policies. This contributes to the economic growth and development of the country.

To enhance the sustained growth agenda by the government of Uganda, robust financial reporting by companies is required (Uganda National Investment Policy, Citation2018). This has led to enactment of sound financial reporting infrastructure consisting of legal enforcement mechanisms. We begin to see the enactment of laws by the government of Uganda during colonial times. Others were enacted immediately after independence, such as the Companies Act of 1961. More regulations came on board around 2000, such as the Financial Institutions Act of 2004. This was later amended in 2016 to include agency banking, bancassurance, special access to the Credit Reference Bureau, and reform Deposit Protection Fund, among others. Since then, other regulations have come on board such as the Companies Act (Citation2012), the Accountants Act (Citation2013), The Micro Finance and Deposit-taking Institutions Act (2003), The Uganda Securities Listings Rules (Citation2003), Insurance Act (Citation2017), National Coffee Act (Citation2021), Uganda Communications Act (2013), Uganda Retirement Benefits Scheme Act (Citation2011), Electricity Act (Citation2022) among others. These regulations provide policies that regulated firms should follow in order to report high earnings quality. For instance, the Companies Act (Citation2012), section 154(1), requires regulated firms to prepare books of accounts that give a true and fair view of the state of affairs of the firm. Similarly, the Accountants Act (Citation2013), section 54(2) necessitates heads of accounts and finance and internal auditors working with public interest firms to be members of the Institute of Certified Public Accountants (ICPAU) of Uganda. Moreover, for one to be a member of ICPAU, he/she must have passed the qualifying examinations conducted by the examinations board or be a full member of any accountancy body recognized by ICPAU (Accountants Act, Section 5(2a). Further, the international financial reporting standards, as ratified by ICPAU, also guide on the preparation and presentation of accounting information in financial reports. But also, the presence of regulatory authorities who supervise these regulated firms in Uganda offer a fertile ground for transparency, accountability as well as sound and sustainable financial reporting practices.

Although regulations are in place, Uganda’s earnings quality is still far from desirable, despite its adoption of international financial reporting standards (IFRS). For instance, the Bank of Uganda Supervision Report (Citation2022) indicates that commercial banks still have financial reporting gaps, corporate governance lapses, threatened independence of the second line of defence by the CEOs, and non-compliance with the requirements of the Financial Institutions Act 2004. Similarly, the Ogoola Judicial Commission report (2000) presented three commercial banks that failed as a result of false revenue statements. In order to escape paying income tax, Mugisha (Citation2019) observed that businesses in Uganda ‘force’ deficits into their books of accounts. Furthermore, errors have been found in financial reports of some Ugandan commercial institutions (see, Housing Finance Bank’s annual financial reports from 2017/2016 and 2018/2017). In addition, there has been evidence of top management usurping board powers in commercial institutions (see, Bank of Uganda Annual Supervision Report, Citation2020). The Companies Act (Citation2012), Section 14, Table F, mandates firms that are either public or private to adopt the code of corporate governance at the time of registration of its articles because the presence of good corporate practices mitigate fraud and errors resulting in high earnings quality. It is thus reasonable to expect that many parties begin to doubt the accurate depiction of Uganda’s earnings data in the wake of such incidents despite the presence of regulations. Thus, Uganda presents a unique environment for this examination.

3. Theoretical literature review

In this study, we use the agency and stakeholder identification and salience theories. The agency theory (Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976) addresses the paradigm of divergent interests between the agent (managers) and principal (owners) in a contractual relationship. Because of the separation of ownership and control, potential conflicts such as information asymmetry arise between agent(management) and shareholders, especially if management aims to maximise utility. The agent is familiar with the firm’s business operations and financial reporting processes and as a result, he fails to disclose accurate earnings information. This leaves the shareholders unable to evaluate the firm’s true performance. It is worse when, in real practice, the manager shirks in the Job (Choi, Citation2015), as this leads to reporting low earnings. Moreover, all this is done to mislead stakeholders about the underlying economic performance of the firm (Healy & Wahlen, Citation1999). To mitigate the self-interest behaviours of the agent, shareholders institute a quality internal audit function to enhance earnings. The ability of IAFQ to mitigate the opportunistic behaviour of the agent largely depends on IA organization status, IA investment, IA competence and IA role performance. For instance, Ismael and Kamel (Citation2021) argue that IAFQ negatively reduces instances of committing earnings management. This suggests that in the presence of IAF, financial information data becomes subject to scrutiny to ensure that it is free from any material misstatements. Accordingly, the CEO, as a key internal stakeholder, has the potential to reconstruct the rules, norms, beliefs, and policies that guide IA’s actions (Kalembe et al., Citation2023; Cai & Mehari, Citation2015).

The agency theorists emphasize two views. First, that internal auditors are agents of shareholders, reporting to the audit committee. Another view is that internal auditors are mere employees of the CEO and not agents of shareholders. The latter view is appropriate for environments with less developed capital markets and, therefore, the agency’s theoretical position suggesting a connection between internal audit function quality and earnings quality needs to additionally consider the effect of the third variable – CEO power. Yet, the influence of CEO power on earnings quality and its moderating effect on the link between internal audit function quality and earning quality has been omitted in prior studies.

The stakeholder identification and salience theory (Mitchell et al. Citation1997) assumes that stakeholders can be identified if they possess power to influence the firm. A stakeholder is defined as a person or group of persons who can affect or be affected by the achievement or realization of an organization’s purpose (Freeman, Freeman et al., Citation2010), such as the CEO. Deegan (Citation2014) in his attempt to define financial accounting theories presents two contrasting positions of stakeholder theory, namely; the managerial position and normative position. This study follows the managerial perspective because of its ability to address issues of stakeholder (in this case, the CEO as a key internal stakeholder) power and how this power affects the ability of the CEO to comply with other stakeholders’ expectations, such as high-quality earnings, known to be one of their primary interests in the firm.

In the context of Uganda, salient stakeholders such as the Uganda Revenue Authority, Banks, and investors expect powerful CEOs to report high earnings quality to enable them make valid economic decisions. In a firm setting, the CEO is one of the preparers of the financial reports and can therefore use his power to influence earnings quality. This is possible especially if such a CEO is knowledgeable and has a rich background in accounting. It is thus expected that the internal audit function mitigates any intentions of the CEO to manage earnings. In an environment like Uganda, stakeholders have differing accounting earnings needs. For example, banks are interested in high-earnings quality because this acts as a signal that the firm can finance its cost of borrowing (Waweru et al., Citation2011). URA’s interest entails the assessment of correct taxes to levy from regulated firms. Moreover, the demands of these stakeholders are usually urgent and may require immediate attention from powerful CEOs (Mitchell et al. Citation1997). Thus, a powerful CEO, as a preparer of financial statements, assesses the importance of meeting stakeholder demands because their needs’ differentials create a lot of contradictions. This leaves the CEO with the task of fulfilling these multiple objectives. As such, he/she is propelled to choose an accounting policy to report earnings that may suit the needs of different stakeholders, including his/hers.

4. Empirical literature review and hypotheses development

4.1 The concept of earnings quality

Dechow and Schrand (Citation2004) define high earnings quality as those that accurately reflect the firm’s current operating performance. Dechow et al. (Citation2010) indicate that high earnings quality provides more information about the features of the firm’s financial performance that are relevant for a specific decision made for a specific decision maker. According to Schipper and Vincent (Citation2003), earnings are of high quality if they faithfully represent the Hicksian income.

Earnings quality is a multifaceted concept (Gutiérrez & Rodríguez, Citation2019). For instance; Dechow et al. (Citation2010) used three broad proxies for earnings quality such as properties of earnings (earnings persistence and accruals; earnings smoothness; asymmetric timeliness and timely loss recognition and target beating), investor responsiveness to earnings (earnings response coefficient), and external indicators of earnings misstatements (restatements and internal control procedure deficiencies). Also, Francis et al. (Citation2008) used accounting-based constructs (accrual quality, persistence, predictability, and smoothness) and market-based constructs (value relevance, timeliness and conservatism). Scholars like Adams et al. (Citation2005) developed a power index comprising CEO founder, tenure, president, compensation, and chair. Likewise, Bebchuk et al. (Citation2011) utilized CEO pay slice. Other stock market studies proxied for earnings quality using panel data in terms of faithful representation and relevance to assess earnings quality (Benkraiem et al., Citation2021; Brahem et al., Citation2022). For instance, Benkraiem et al. (Citation2021) measured earnings quality using a composite of accurate depiction (accrual quality) and relevance (persistence, predictability, value relevance, and timeliness). Discretionary accruals and earnings informativeness were used by Brahem et al. (Citation2022) as alternate metrics for faithful representation and relevance, respectively.

In Uganda, Nkundabanyanga et al.’s (Citation2013) study on accounting quality focused on comparability, accuracy, reliability, relevance, and understandability of financial information in a government Ministry. However, we fail to generalise these findings because of the differences in firms’ internal structures. Therefore, the current study proxies for earnings quality in terms of the fundamental qualitative characteristics of relevance and faithful representation of accounting information as enshrined in the Conceptual Framework for Financial Reporting, 2018. Earnings information is relevant if it is capable of creating a difference in the decisions made by the user. Such information should either have predictive or confirmatory value. Earnings with predictive value has the ability to predict future events, while earnings with confirmatory value enable users to confirm past or earlier earnings. On the other hand, faithful representation means that the information should be free from any error, unbiased and should be complete.

4.2. Internal audit function quality and earnings quality

The Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA, Citation2022) defines internal audit (IA) as an independent, objective assurance and consulting activity that is designed to add value and improve an organization’s objectives. Abbott et al. (Citation2016) indicates that an internal audit (IA) function is of quality if it has the ability to prevent or detect material misstatements and its inclination to report such misstatements to the audit committee or the external auditor. Consistent with the agency theory (Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976), internal audit function is a monitoring mechanism that mitigates low earnings quality. The proponents of the agency theory argue that internal auditors are agents of shareholders, reporting to the audit committee. In this view, it is expected that financial statement data is subjected to adequate disclosure and scrutiny by audit committee members since these are responsible for financial reporting process.

Previous studies on IAFQ and EQ have found inconsistent results (Nalukenge et al., Citation2022; Kaawaase et al., Citation2021; Ismael & Kamel, Citation2021; Prasad et al., Citation2021; Tumwebaze et al., Citation2018; Abbott et al., Citation2016; Ege, Citation2015; Johl et al., Citation2013; Sierra Garcia et al., Citation2012; Prawitt et al., Citation2009; Davidson et al., Citation2005). For example, Tumwebaze et al. (Citation2018) found that internal audit improves accountability in statutory corporations of Uganda. In addition, Nalukenge et al. (Citation2022) revealed that internal audit quality is positively related to accountability of which earnings quality is part. Also, Kaawaase et al. (Citation2021) documented that internal audit quality improves financial reporting quality among financial services firms in Uganda. Accordingly, Madawaki et al. (Citation2022) finds a positive and significant relationship between internal audit and financial reporting quality among listed firms in Nigeria. Prawitt et al. (Citation2009) found that quality internal audit function is negatively associated with lower levels of earnings quality. Ege (Citation2015) posits that quality internal audit function reduces management misconduct. Also, Sierra García et al. (Citation2012) revealed that internal audit function has a negative relation with earnings management. Contrarily, Davidson et al. (Citation2005) found that internal audit function is not associated with low accruals earnings management. Further, Prasad et al. (Citation2021) reported no significant relationship between internal audit use and earnings quality. Similarly, Ismael and Kamel (Citation2021) documented that internal auditor’s independence does not reduce abnormal accruals among listed firms in UK. Ardianto et al. (Citation2023) revealed that the internal audit function does not efficiently enhance the efficiency of corporate investment decisions in Indonesian public companies. A study by Kabuye et al. (Citation2018) revealed that internal audit activities do not significantly predict fraud management in Uganda’s financial services sector. Kalembe et al. (Citation2023) provides evidence that IAF is a ceremonial function, and its focus is on internal controls, risk management and compliance but not financial statement reviews. This leaves material misstatements go undetected. Similarly, lapses and laxity in corporate governance mechanisms including internal audit, are evident making the internal audit function ineffective in commercial Banks in Uganda (Bank of Uganda supervision report, Citation2022). This suggests that internal audit may not be a disciplining mechanism in Uganda. We hypothesize that;

H1: A relationship exists between IAFQ and EQ.

4.3. Internal audit function quality and CEO power

Consistent with the managerial branch of stakeholder theory (Mitchell et al., Citation1997), internal auditors can be treated by the CEO in the same way as any other employee. As a result, they succumb to social pressure and familiarity from CEOs to perform in their interests (Kabuye et al. Citation2018), despite their code of ethics. This suggests that the internal auditors may not find it possible to add value to firms through provision of assurance and advisory roles in the presence of a powerful CEO (Roussy & Brivot, Citation2016).

Studies that empirically examine the relationship between internal audit function quality and CEO power report consistent results (for instance, Jiang et al., Citation2018; Prawitt et al., Citation2009; Hermalin & Weisbach, Citation1998). For instance, Jiang et al. (Citation2018) reported that IAFQ is negatively associated with CEO power. Similarly, Hermalin & Weisbach (Citation1998) indicated that IAFQ can be reduced by an opportunistic powerful CEO since he/she has the discretion to bargain with the board to reduce its potential monitoring. Prawitt et al. (Citation2009) documented that a high-quality internal audit function deters earnings manipulation and fraud that would have been committed by a powerful CEO. Literature concurs with the current situation in Uganda. The Bank of Uganda Supervision Report (Citation2022) adduced evidence that internal auditors have continued to face threatened independence from CEOs in commercial Banks. In addition, it is also indicated that CEOs usurp powers of the board and as a result, they become ineffective in monitoring the internal auditors (Bank of Uganda Supervision Report, Citation2022). We thus hypothesise that;

H2: A negative relationship exists between IAFQ and CEO power.

4.4. CEO power and earnings quality

The theory of stakeholder identification and salience (Mitchell et al., Citation1997) indicates that a CEO is a key internal stakeholder who has power to influence organizational outcomes, hence making him the most powerful figure in a firm (Li et al., Citation2016). French and Raven (Citation1959) define power as a relationship between two or more people where one person has more influence than the other, translating into psychological change. CEO power is a relational construct, implying that it arises out of social relations and networks (Cormier et al., Citation2016; Tang et al., Citation2011). This power can be disastrous to the firm especially when its exercise can be abused for example, through manipulation of earnings (Cormier et al., Citation2016) and also when such a CEO may not value any independent advice or have his decisions scrutinized (Han et al., Citation2016).

Literature conceptualizes CEO power as structural power, expert power, ownership power, prestige power and formal power (Sheikh, Citation2019; Lisic et al., Citation2016; Finkelstein, Citation1992; Pearce & Zahra, Citation1991). CEO’s structural power comes from CEO’s legitimate authority, in terms of his relative compensation (CEO Pay slice) (Shiah-Hou, Citation2021; Sheik, Citation2019; Lisic et al., Citation2016; Bebchuk et al., Citation2011; Finkelstein, Citation1992). Expert power emanates from CEO’s financial experience, the number of positions (functional positions) served in, and CEO Tenure. CEO ownership is understood in terms of a CEO founder, relative and his shareholdings in a firm (Sheikh, Citation2019; Finkelstein, Citation1992). Formal power entails power of the CEO relative to that of the board (Pearce & Zahra, Citation1991). The majority of these studies (See, Shiah-Hou, Citation2021; Sheikh, Citation2019; Lisic et al., Citation2016; Bebchuk et al., Citation2011) conceptualised CEO power in terms of structural power, ownership power and expert power, and ignored prestige power, arguing that it is not a proximal measure of CEO power and, that its hard to obtain data using secondary sources (Han et al., Citation2016; Tang et al., Citation2011). This gap is closed in this study because it is easier to understand the perceptions of the respondents using a survey instrument.

Consistent with stakeholder identification and salience theory (Mitchell et al., Citation1997), powerful CEOs create an opaque environment which lowers the quality of earnings profitability. This aligns with existing empirical stock market studies (Arif et al., Citation2023; Kalembe et al., Citation2023; Shiah-Hou, Citation2021; Cormier et al., Citation2016; Friedman, Citation2014; Bebchuk et al., Citation2011; Feng et al., Citation2011; Malmendier & Tate, Citation2009; Adams et al., Citation2005) that documented a relationship between CEO power and earnings quality. For instance, Arif et al. (Citation2023) reported that CEOs with political, structural and expert power have significant detrimental effect on earnings quality. Relatedly, Kalembe et al. (Citation2023) reported that CEO power significantly reduces earnings quality in Uganda. Shiah-Hou (Citation2021) revealed that CEO power significantly lowers earnings quality in U.S. Also, Cormier et al. (Citation2016) noted that firms that are accused of financial misreporting exhibit strong CEO power in Canada. Friedman (Citation2014) revealed that powerful CEOs pressure CFOs to bias financial statement results, which consequently lowers the financial reporting quality. According to Feng et al. (Citation2011), accounting manipulations are more likely when CEO power is high. Bebchuk et al. (Citation2011) documented that CEO pay slice is associated with lower accounting profitability. In another study by Malmendier and Tate (Citation2009), it was found that superstar CEOs are more likely to influence reported performance by managing earnings to meet the market’s higher expectations. Further, Adams et al. (Citation2005) reported that CEOs who have more decision-making power experience more variability in firm performance. This may not be any different in Uganda where gaps in financial reporting and non-compliance with implementation of IFRS as per the requirements of Financial Institutions Act 2004 are instigated by powerful CEOs (Bank of Uganda Supervision Report, Citation2022). It is then likely, that the quality of reported earnings will be low. We note that previous studies that have tested the association of all five dimensions (structural, expert, ownership, formal, and prestige power) of CEO power on earnings quality are few. Moreover, Prawitt et al. (Citation2009) also calls for further studies to explore the association between CEO power and earnings quality (Earnings management) using larger samples in different contexts. This study responds to this call. We therefore hypothesize that;

H3: A negative relationship exists between CEO power and EQ.

4.5. Internal audit function quality, CEO power and earnings quality

One of the objectives of this paper was to present evidence on the moderating role of CEO power in the relationship between IAFQ and EQ. Indeed, studies that have explored this relationship are scarce. The available studies that have attempted to investigate the moderating role of CEO power focused on executive pay and performance (Ntim et al., Citation2019), corporate social responsibility and performance (Javeed & Lefen, Citation2019), internal control quality and audit committee effectiveness (Lisic et al., Citation2016) among others.

Consistent with the agency theory, high earnings quality is reported when internal audit evaluates the integrity and reliability of financial statement data. On the other hand, the stakeholder theory of identification and salience (Mitchell et al., Citation1997) notes that a powerful CEO can influence earnings quality. However, when CEO power interacts with internal audit function, the quality of reported earnings improves. Thus, the framework put forward by the agency and stakeholder identification and salience theories suggest that when a CEO is powerful, he/she can decide to affect the relationship between internal audit function quality and earnings quality. The strength or direction of the relationship between internal audit function quality and earnings quality is likely to be affected by CEO power. This paper therefore, aims at answering the research question of whether the effect of internal audit function quality on earnings quality changes with CEO power, speaking of which it is required to test the hypothesis that internal audit function quality interacts with CEO power to influence earnings quality. Conflating the positions of agency theory and stakeholder identification and salience theory suggest that the strength or direction of the relationship between IAFQ and EQ is affected by CEO power. Hence, we hypothesise that:

H4: IAFQ interacts with CEO power to influence EQ.

5. Research design

5.1. Design, population and sample

This study is cross-sectional and correlational. The study population comprised 284 regulated firms (see, ) (Bank of Uganda (BOU) website, Citation2020; IRA Website, 2021; CMA Website, 2020; UCC Annual report, 2020; Uganda Media Landscape report, 2019; URBRA Website, 2020; ERA Website, 2020; UCDA Monthly report January 2020). The firms selected for the study were public interest firms that are regulated. We utilize Yamane’s (Citation1967) approach to obtain a sample of 166 firms. We employed proportionate stratified sampling to generate the number of subjects per stratum and employed lottery method without replacement to obtain the subjects. The stratas included financial institutions, insurance firms, utility firms and others (pension schemes and coffee export companies). We aimed to enlist responses from both Chief Finance Officers (CFOs) and Chief Internal Auditors (CIAs) who formed our units of inquiry because they were reachable. Therefore, data are obtained from 130 CFOs and 44 CIA. The unit of analysis was a regulated firm, and data was aggregated at a firm level. Usable questionnaires were collected from 136 firms – a response rate of 82%. According to Mellahi and Harris (Citation2016), this response rate is sufficient and far above the recommended response rate of 50%.

Table 1. Sample selection process.

In terms of respondent characteristics, the majority, represented by 68.4%, were male compared to 31.6% who were females. This implies that the males are more dominant in the positions of CFO and Heads of internal audit. With respect to age, 42.5% represented majority of the respondents between 36 and 45 years, 36.2% were less than 35 years, 19% were between 46 and 55 years. In terms of education, the majority represented by 53.4% hold a Bachelors’ degree, 45.4% hold a masters’ degree and the least represented by 1.1% had a PhD. In relation to professional qualification, majority of the respondents represented by 62.6% were CPAs, 31% had ACCA, 5.7% belonged to Institute of Internal Auditors, and 1% belonged to Chartered Institute of Accountants. Accordingly, 39.7% majority worked for a period between 5 and 10 years, 33.3% for a period less than 5 years, 14.9% worked between 11 and 15 years while 12.1% worked for a period above 16 years.

Relating to firm characteristics, majority represented by 60% finance their operations using equity, 38.2% use equity and debt while 1% use only debt. Also, 46% of the firms have existed for a period above 16 years, 26% between 11 and 15 years, 19% have been in existence between 5 and 10 years while the least represented by 9% have been in existence for less than 5 years. In terms of auditor size, majority represented by 52% are audited by small and medium practices yet, 48% are audited by BIG 4s. It was also observed that 53%, majority of the firms are indigenous firms, and only 47% are foreign owned firms. With respect to board size, majority represented by 53% have large boards while 47% have small boards. Finally, 74% majority of the firms were interlocked and 26% were not interlocked. Over all, reliable responses were collected from the respondents. Details of the respondent and firm characteristics are presented in .

Table 2. Respondent and firm characteristics.

5.2. Questionnaire and variable measurement

We used a self- administered closed ended questionnaire anchored on a four-point Likert scale, ranging from Strongly Disagree (1), Disagree (2), Agree (3) and Strongly Agree (4). We used closed-ended questions because of the intent of calculating the mean rating of the extent of agreement with each statement (Bradburn et al., Citation2004). The researchers reviewed literature on the study variables from previous researchers. This was modified to suit the study context.

In this study, internal audit function quality was treated as the independent variable. This was conceptualized in terms of IA competence, IA organizational status, IA investment and IA role performance (Johl et al., Citation2013; Ousii & Taktak, Citation2018).

The moderating variable was CEO power. CEO power was operationalized in terms of structural power, prestige power, expert power, ownership power and formal power (Finkelstein, Citation1992; Pearce & Zahra, Citation1991). We use Jose’s Modgraph (2008) to test for moderation. Moderation requires the estimation of the interaction terms between the independent variable (internal audit function quality) and the moderating variable (CEO power). Given that the interaction term is a product of two variables, we centre both the independent and moderating variables (Aiken & West, Citation1991). This is achieved by subtracting their respective means and computing the interaction term as the product of the centred variables. variables are centred to avoid potentially problematic high multi-collinearity with the derived interaction terms.

Earnings quality was the dependent variable. This was measured using relevance and faithful representation as enshrined in the Conceptual Framework for Financial Accounting, 2018.

Control variables: According to Bartov et al. (Citation2000), failure to control for confounding variables could falsely lead to rejecting the hypotheses that would have been accepted. We follow Dechow et al. (Citation2010) to classify the study’s control variables in terms of governance and controls, auditors and external characteristics. Control variables classified as governance and control include board size (Cormier et al., Citation2016; Lyengar et al., Citation2010), firm ownership (Krismiaji et al., Citation2016) and CEO interlock (Lyengar et al., Citation2010); external factors include a firm’s capital structure (Alzoubi, Citation2019), while auditor type (Alzoubi, Citation2019; Abdullah & Ismail, Citation2016) is under the category of auditors. The study also controls for firm age (Nkundabanyanga et al., Citation2013; Abbott et al., Citation2016). However, this is not included in the categorisation index by Dechow et al. (Citation2010). Variables, their operationalization, and measurements are indicated in . The study’s conceptualization is depicted in the Conceptual Framework presented as .

Table 3. Variable operationalisation and measurement.

is a conceptual and theoretical model that guided the study. The model made an assertion that IAFQ directly explains variances in EQ. IAFQ is directly linked to CEO power while CEO power is linked to EQ. Likewise, CEO power moderates the relationship between IAFQ and EQ. The arrows in the model show the direction of the hypothesised relationships.

We further controlled for both item and unit non-response. Item non- response is when certain questions in a survey are not answered by a respondent while unit non-response is where the firms expected to participate in the study deliberately refuse to participate. This study adopted Dillman’s strategies (1991) such as seeking for permission to collect data from Human Resources Manager, attaching a cover letter on a questionnaire with clear instructions, and making follow ups in order to retrieve the questionnaires. The researchers also tested for common methods bias (CMB), using Harman’s single factor test. All factors where loaded into exploratory factor analysis (EFA) using principal component analysis to determine the number of factors that could account for variance in the variables. Many factors emerged for each variable as shown in factor analysis results in , suggesting absence of common method variance. Coefficients of 0.5 and above, were considered sufficient in determining reliable scales (Field, Citation2013).

5.3. Tests of factorability, reliability and validity

We follow the recommendations of Field (Citation2013) in preparing data for analysis. Before performing principal component analysis (PCA) for scales, we assessed the suitability of the data for factor analysis based on sample size adequacy, Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) (Kaiser, 1974) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (Bartlett, 1954) and all scales reached statistical significance (p < 0.05) (significant value was 0.00 for each scale). The analysis returned KMO values of .789, .849, and .749 for CEO power, internal audit function quality, and earnings quality respectively. We run PCA and varimax rotation with Kaiser Normalization, suppress loadings <0.50 (Field, Citation2013), and cut-off factors with an Eigen value of less than 1 (Kaiser, 1974). The results for CEO power show that it has five components: structural, ownership, prestige, formal, and expert power. All these components explain a total variance of 63% in CEO power (Appendix, ). Similarly, internal audit function quality has four components, namely, IA organization status, investment, IA competence, and IA role performance, which implies that convergent validity was achieved. Overall, the factors account for 55% of the total variance explained in the latent variable IAFQ (Appendix, ). For earnings quality, two components loaded; faithful representation and relevance. These collectively account for 63% of total variance explained in earnings quality (Appendix, ). Collectively, these results which are presented in Appendices, supported the factorability of the correlation matrices which are significantly different from the identity matrices in which the variables would not correlate with each other.

After performing EFA using SPSS V.25, the items retained were imported into Smart PLS software for confirmatory composite analysis. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to detect observable variables that measure each construct or factors (Kalembe et al. Citation2023). We apply variance-based SEM using SmartPLS V4.0 to conduct reliability and validity assessments of the constructs and assess the hypothetical relationships between the constructs. SEM was selected because of its predictive power and ability to work well with medium and small samples (Hair et al., Citation2017; Kalembe et al., Citation2023) such as ours. The results of confirmed factors, reliability as well as convergent and discriminant validity assessments are reported in . The results for CEO power are α coefficient after CFA =.840, rho A = .850, and Composite reliability (CR) after CFA = .868. Also, results for IAFQ are α coefficient =.911, rho A = .915, and composite reliability (CR) after CFA = .925. Finally results for EQ are α coefficient =.812, rho A = .823, and composite reliability (CR) after CFA = .861. Collectively, these results show that reliability for all our variables meets the threshold requirements per Hair et al. (Citation2017). The results for convergent validity indicate average variance extracted (AVE) for CEO power = .684, IAFQ = .729, and EQ = .647. Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981) suggest that these values should be above .5 for acceptable convergent validity. The study also assessed for multicollinearity and found that tolerance values were below 0.2 and VIF above 0.5 suggesting absence of multi-collinearity (Hair et al., Citation2017).

Table 4. Summary of factors, validity and reliability tests for earnings quality and path coefficients -the measurement model for earnings quality.

Table 5. Summary of loading estimates, validity and reliability tests for internal audit function quality and path coefficients -the measurement model for internal audit function quality.

Table 6. Summary of Loading estimates, validity and reliability tests for CEO Power and path coefficients -the measurement model of CEO power.

6. Empirical results and Discussion

In terms of descriptive statistics, results in indicate that the mean scores for IAFQ and standard deviations (SD) are 3.12 and 0.03 on a four-point Likert scale respectively. This means that the respondents agree that IAF in regulated firms in Uganda is perceived to be better. Also, the mean and SD for CEO power are 2.28 and 0.04, respectively, suggesting that respondents agree that CEO power in regulated firms in Uganda is perceived to be moderate. The mean value for EQ is 2.92, indicating that the current status quo of earnings quality in Uganda is low. As observed, the SDs are low for all the constructs, indicating that the data points are close to the means (Field, Citation2013), hence representing the observed data.

Table 7. Descriptive statistics.

To determine whether firm differences influenced the study variables, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine the impact of firm sector on the study variables. The results of the one-way ANOVA in show that the p-values of all the study variables are above 0.05. This suggests that the group differences between firms did not significantly influence their responses between the study variables. Also, the overall differences between respondents did not bias the results of the study (see, ).

Table 8. ANOVA Global variables and firm sector.

Table 9. Global variables and position of respondents in a firm.

6.1. Correlation analysis

The results in revealed that IAFQ is positive but not significantly related to EQ (r = .025, p > 0.01). The results imply that a unit change in IAFQ in terms of competence for example, may lead to a unit change in earnings quality. The correlation between IAFQ and CEO power is negative but not statistically significant (r = –.056, p > 0.01). The finding implies that IAFQ diminishes when the CEO is powerful. The results reveal that all the dimensions of IAFQ are negative but not significantly related to CEO power. Further, the results also indicated that CEO power (CEOP) is negative and significantly related to EQ (r = –.349**, p < 0.01). The finding implies that CEOP causes a reduction in earnings quality. Amongst all the dimensions of CEOP, expert power and prestige power are significant and negatively related to EQ. In terms of control variables, only firm age is negative and statistically significant with EQ. Other control variables such as ownership, capital structure, employee size, CEO interlock, auditor type, and Board size are not significantly related to earnings quality.

Table 10. Zero order matrix.

6.2. Regression analysis results

The regression analysis results are obtained from an estimated PLS-SEM model that was run to establish the extent of the relationships between the independent variable and dependent variable.

We used the standardised beta values because they take on real values without a standard measurement and are easier to interpret (Field, Citation2013). The results in indicate that IAFQ is positive but not significantly related with EQ at this level of analysis (β = 0.102, t = 0.594, p > 0.05), hence H1 was not supported. The model returned an NFI of 0.100, which is an indication that there is strong convergent validity. Other model fit indices such as SRMR are assessed and this returns 0.000, a signal that the model fits the data well. Relatedly, the path coefficient between IAFQ and CEOP revealed a negative relation although this association was not significant (β= –0.341, t = 1.070, p > 0.05). Thus, H2was supported. The model returned an NFI = 1.000, chi-square is non-significant at 0.05 level of significance, and SRMR = 0.000. This implies that the model acceptably fits the data well. The results further indicate that CEOP is statistically significant and negatively related to EQ (β = –0.360, t = 4.477, p < 0.05), hence H3 was substantiated. These results suggest that increases in CEOP causes negative variations in EQ. Fit indices for this model are NFI = 1.000 and SRMR = 0.000. According to the results, CEO power explains 11.7% of variations in earnings quality.

Table 11. Direct paths and hypothesized relationships.

Further, results in revealed that CEOP is the most significant predictor of EQ in Uganda relative to IAFQ. Overall, the model, which also controls for firm age, employee size, auditor type, board size, CEO interlock, capital structure, and firm ownership, accounts for 12.5% of the variations in earnings quality. However, the position of this study has been that the relationship between IAFQ and EQ is moderated by CEOP, according to which H4 was put forward. We use multivariate regression analysis to test the extent to which CEOP and its interactions with IAFQ significantly predict EQ. Using SmartPLS, we initially tested for the influence of internal audit function and found that it accounts for 4.2% variations in earnings quality (). We also tested for the influence of CEOP and found that it accounts for 11.7% of significant variances in EQ (See ). Using SPSS (see, ), CEOP is the only significant predictor of EQ, accounting for 10% of variations in EQ. We then add the interaction term (CEOP * IAFQ) to test for H4. With the addition of the interaction term, the variances explained improved to 12.1% (see, ). The interaction term is significant (β = –.494, p<.000). This means that the interaction of IAFQ and CEOP explains more of the variances in overall EQ than the direct influence of IAFQ or CEO power on their own. As earlier indicated, the strength or direction of the relationship between IAFQ and EQ should be affected by CEOP for the moderation effect to be claimed. As can be seen from , without the interaction term, IAFQ is not a significant predictor of EQ but when the interaction term is included, it becomes a significant predictor (β = 1.213, p<.05). The results show that the interactive-term boosts the main effects (IAFQ and CEOP) to explain the variances in EQ. Since the interaction term is significant it is maintained that H4 is supported. This supports the assertion of the existence of a moderating effect of CEOP in the relationship between IAFQ and EQ in Uganda.

Table 12. The moderation effect of CEO power in the relationship between internal audit function quality and earnings quality.

As an additional check, we examine the slopes of graphs to determine the moderating effect of the variables using Jose’s (Citation2008) Modgraph. The graph (See, Appendix, ) shows that the lines are not parallel but do cross each other at some point. This is in line with Aiken and West (Citation1991), who argue that for the interaction to be significant and interpretable and for moderation to have taken place, the graphs should not be parallel or must have different gradients or slopes, implying that the magnitude of an effect is greater at one level of a variable than at another level. We, therefore, conclude that CEOP significantly interacts with IAFQ. The graph (Appendix, ) suggests that the greater the power of the CEO, the lower the effect of IAF on EQ. This proves the inverse relationship between CEOP and EQ even with increasing IAFQ. The results from multivariate analysis further confirm the assertion that the interaction term is causing significant variances in EQ and that the consistency of results even in the face of the control variables is further testimony of the predictive validity of the interaction.

So, in closing, the results show that CEOP is negatively related to and a significant predictor of EQ. IAFQ while related to EQ is not a significant predictor of EQ. The interaction effects of IAFQ and CEOP on EQ are significant, according to which when CEOP is high, the effect on IAF and EQ is low.

6.2.1. Additional analyses

We further check whether CEOP can mediator in the relationship between IAFQ and EQ. The results reveal that CEOP does not mediate the relationship between IAFQ and EQ (β = 0.087, t = 0.096, p > 0.05). This suggests that in Uganda’s environment, CEOP is a moderator and not a mediator, hence confirming H4. Further, we subject our data to endogeneity bias test using Gaussian Copula beta coefficients (Hult et al., Citation2018). The results in reveal that beta coefficients for all the study variables are not significant (p-values >0.05), indicating the absence of endogeneity issues in our data.

Table 13. Endogeneity Test.

6.3. Discussion

The results of the current study indicate that CEOP is statistically significant and negatively related to EQ. As CEOP is a negative element in EQ, Uganda’s earnings are perceived to be low. This factor is likely to be unique to Uganda’s environment and other similar environments. The finding arguments the theory of stakeholder identification and salience (Mitchell et al., Citation1997) that suggests that powerful CEOs create an opaque financial reporting environment which limits disclosure of accurate financial statement data. This potentially creates problems of accountability leaving stakeholders unable to evaluate the performance of the firm. The finding may suggest that CEOs who are knowledgeable accountants are likely to report values that are not accurate and justifiable. This finding is in line with previous scholars (e.g, Kalembe et al., Citation2023; Shiah-Hou, Citation2021; Duong et al., Citation2020; Ngo & Nguyen, Citation2022). Kalembe et al. (Citation2023) reported that CEO power is negative and significantly related to EQ. Also, Shiah-Hou (Citation2021) documented a negative and significant relationship between CEOP and EQ. Also, Duong et al. (Citation2020) found out that powerful CEOs magnify the negative impact on EQ especially if the CFO is a board member. Further, Ngo and Nguyen (Citation2022) concluded that firms with CEOs who have financial and accounting experience have more influence and intervention on earnings management which consequently affects financial reporting quality. Similarly, Arif et al. (Citation2023) documented that CEOs with political, structural and expert power have significant detrimental effect on earnings quality.

Internal audit function quality is positive and not significantly related to earnings quality. This finding is consistent with the agency theoretical position suggesting a connection between internal audit function quality and earnings quality. This finding is in line with Tumwebaze et al. (Citation2018) who found that IA improves accountability in statutory corporations of Uganda. Similarly, Nalukenge et al. (Citation2022) revealed that internal audit quality is positively related to accountability of which earnings quality is part. Also, Kaawaase et al. (Citation2021) documented that internal audit quality improves financial reporting quality among financial services firms in Uganda. Accordingly, Madawaki et al. (Citation2022) revealed a positive and significant relationship between internal audit and financial reporting quality among listed firms in Nigeria. A similar study by Ege (Citation2015) found out that quality internal audit function reduces management misconduct. These previous studies extend the debate that internal audit is a key monitoring mechanism in regulated firms in Uganda. This renders this function a disciplining mechanism that mitigates fraud, errors and financial misreporting. However, contradictory findings have also been found (see, Ismael & Kamel, Citation2021 and Ardianto et al., Citation2023; Prasad et al., Citation2021).

Further, internal audit function quality is negative but not related significantly to CEO power. The finding is consistent with agency’s theoretical perspective that argues that the principal’s additional monitoring costs in form of an IA are potentially futile with very powerful CEOs. This finding also contradicts the theory towards stakeholder identification and salience (Mitchell et al., Citation1997), specifically the managerial perspective (Deegan, Citation2014), which suggests that the internal auditor is considered as just any other stakeholder to manage by the CEO. This is intuitively sensible because a powerful CEO has the potential to reconstruct the rules, norms, beliefs, and policies that guide his or her action (Cai & Mehari, Citation2015). The findings are consistent with previous studies such as Hermalin & Weisbach (Citation1998) who argue that IAQ can be reduced by powerful CEOs especially when he/she can bargain with the board to reduce its potential monitoring role. Similarly, Jiang et al. (Citation2018) also reported that IAFQ is negatively associated with CEOP.

Finally, the interaction of IAFQ and CEO power explains more variances in overall earnings quality than the direct influence of IAFQ or CEOP on their own. This finding potentially clears the ambivalence existing in literature (see, Davidson et al., Citation2005; Ege, Citation2015; Johl et al., Citation2013; Prawitt et al., Citation2009) on the role of IAF in enhancing EQ by showing that the greater the power of the CEO, the lower the effect of IAF on EQ. Because of this interplay, ambivalent results on the efficacy of internal audit function quality on earnings quality will continue to surface in studies that do not address the moderating role of CEOP. The current results support the idea that a research design involving at least two independent variables should consider examining the main effects of each of the independent variables (Friedrich, Citation1982) and also the multiplicative effects. IAFQ will influence earnings quality given a level of the firm’s CEOP and CEOP will influence EQ given a level of IAFQ. These results indicate that CEOP and IAFQ cause a magnitude effect on EQ hence the assumption of non-additivity is met (Aiken & West, Citation1991; Friedrich, Citation1982; Jose, Citation2008). It signifies that the two coexist to influence EQ in Uganda’s regulated firms. In the present case, EQ reduces as CEOP goes up and internal audit function quality is enhanced, suggesting that an interactive effect of CEOP and IAFQ is significant in Uganda’s regulated firms.

The finding that CEO power interacts with IAFQ to cause significant variations in earnings quality upholds the framework put forward by agency and stakeholder identification and salience theories suggesting that when a CEO is powerful, he can decide to negatively affect the relationship between internal audit function quality and earnings quality. This supports the view that in environments where market disciplining mechanisms are weak, internal auditors are likely to be mere employees of the CEO and not agents of the principal.

7. Summary and conclusions

The aim of the study was to establish the relationship between internal audit function quality, CEO power and earnings quality. The study also examined how CEO power moderates the relationship between internal audit function quality and earnings quality. The findings revealed that internal audit function quality has a positive but not significant relationship with earnings quality. The results also found that internal audit function quality and CEO power are negatively related but the relationship is not significant. Also, CEOP is statistically significant and negatively related to EQ. Similarly, the interaction effects of CEO power in the link between internal audit function quality and earnings quality are significant to the extent that the greater the power of the CEO, the lower the effect of IAFQ on earnings quality.

The results of this study offer some important implications for the academic community, practitioners, standard setters, and the regulators. For academics, the results suggest that CEO power is more important for earnings quality than internal audit, and this maybe the reason for poor earnings quality. This is because powerful CEOs have the discretion to influence the quality of reported earnings. Accordingly, the study unearthed the use of perceptions in understanding earnings quality contrary to previous studies that used panel data. As regards theory, this study has shown that the relationship between internal audit function quality, CEO power and earnings quality and the multiplicative effect of CEO power and internal audit function quality can be investigated following a multi-theoretic approach of agency, stakeholder identification and salience theories. In terms of practice, the results offer a sensitivity of earnings quality (proxied by relevance and faithful representation) to internal audit function quality and CEO power. Importantly, the relationship between internal audit and earnings quality is a function of CEO power when internal audit staff are regarded as employees responsible to the CEO and not agents of the principal (Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976). Also, the results are of interest to the standard setters-International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) since powerful CEOs appear to be a negative element in their interaction with internal audit function that ensures compliance with accounting policies such as compliance with IFRS. The paper has shown that CEO power is one of the ills vitiating earnings quality. In this regard, it is meaningful to identify the significant multiplicative effects of CEO power and internal audit function quality to uncover what needs to be done to improve earnings quality in Uganda. The regulators such as the Institute of Corporate Governance of Uganda could consider these results to identify the needed changes in their regulation of accounting practice and governance in Uganda. Primarily, the measurement models of earnings quality, CEO power, and internal audit quality reported in this paper allow governments and the institute of internal auditors to evaluate the effectiveness of current firm governance provisions and internal audit status. The salient stakeholders of earnings information such as the Uganda Revenue Authority, Banks, and investors should take note of these findings.

As with any study, there are several limitations with the present one. First, the questionnaire was self-administered and we did not undertake follow-up interviews which would have informed me of the reasons why the respondents held certain views. Second, the present study is cross-sectional; the views held by individuals may change over the years. Finally, although there is an attempt at controlling CMV in particular with proactive instrument design, testing the influence of CMV may not have been dealt away completely owing to the failure to find a plausible common marker variable. Well, policymakers of Uganda dealing with public interest firms, academicians, company owners, and even general readers interested in the field of corporate governance and audit, in particular, might find this study useful. Future research may wish to test this study’s model in predicting earnings quality using the framework for financial reporting 2018 in developed economies.

Author contribution

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Ms. Dorcus Kalembe, Prof. Stephen K. Nkundabanyanga and Prof. Twaha Kigongo Kaawaase: Data collection: Ms. Dorcus Kalembe: Data analysis and interpretation: Ms. Dorcus Kalembe, Prof. Prof. Stephen K. Nkundabanyanga: Data manuscript and preparation: Ms. Dorcus Kalembe, Prof. Stephen K. Nkundabanyanga, Prof. Twaha Kigongo Kaawaase, Dr. Kayongo Isaac. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of manuscript.

Explanation for use of the same dataset and why the study has been separated into different publications

This manuscript ‘Submission ID 232677893’ is an extract from my PhD thesis. Already, one paper has so far been published from this thesis, and the same data set is also being used for this submitted manuscript. We thus disclose as authors previous publication of data since these publications are from the same PhD thesis.

Second, as a university requirement, I am required to have at least two publications from my PhD thesis. The manuscript submitted to your journal will be the second publication. All these publications are aimed at disseminating Knowledge.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

I confirm that the data set is available upon request.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Dorcus Kalembe

Dorcus Kalembe is a Lecturer at Makerere University Business School, Department of Accounting and Finance. She is currently persuing her PhD in the area of accounting. Her research interests are in the areas of financial accounting, auditing, corporate governance and sustainability reporting.

Stephen Korutaro Nkundabanyanga

Stephen Korutaro Nkundabanyanga is a reknowned researcher and a professor of accounting at Makerere University Business School, Department of accounting. He has vast knowledge and research interests in financial accounting, corporate governance, taxation, sustainability reporting among others.

Twaha Kigongo Kaawaase

Twaha Kigongo Kaawaase is a professor at Makerere University Business School, Department of auditing and taxation. His research interests are in the areas of auditing, financial reporting and accounting, taxation and corporate governance.

Isaac Newton Kayongo

Isaac Newton Kayongo is a PhD holder and a senior lecturer in the Department of Finance. His research interets are in behavioural finance, accounting and corporate governance.

References

- Abbott, L. J., Daugherty, B., Parker, S., & Peters, G. F. (2016). Internal audit quality and financial reporting quality; the joint importance of independence and competence. Journal of Accounting Research, 54(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-679X.12099

- Abdullah, N. S., & Ismail, K. I. N. (2016). Women directors, family ownership and earnings management in Malaysia. Asian Review of Accounting, 24(4), 525–550. https://doi.org/10.1108/ARA-07-2015-0067

- Adams, R. B., Almeida, H., & Ferreira, D. (2005). Powerful CEOs and their impact on corporate performance. Review of Financial Studies, 18(4), 1403–1432. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhi030

- Aggarwal, R., Klapper, L., & Wysocki, P. D. (2005). Portfolio preferences of foreign institutional investors. Journal of Banking & Finance, 29(12), 2919–2946. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2004.09.008

- Alzoubi, E. S. S. (2019). Audit committee, internal audit function and earnings management: Evidence from Jordan. Meditari Accountancy Research, 27(1), 72–90. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-06-2017-0160

- Arif, H. M., Mustapha, M. Z., & Abdul Jalil, A. (2023). Do powerful CEOs matter for earnings quality? Evidence from Bangladesh. PloS One, 18(1), e0276935. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0276935

- Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Testing and interpreting interactions. SAGE.

- Ardianto, A., Anridho, N., Ngelo, A. A., Ekasari, W. F., & Haider, I. (2023). Internal audit function and investment efficiency: Evidence from public companies in Indonesia. Cogent Business & Management, 10(2), 2242174. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2242174

- Athari, S. A. (2022b). Does investor protection affect corporate dividend policy? Evidence from Asian Markets. Bulletin of Economic Research, 74(2), 579–598. https://doi.org/10.1111/boer.12310

- Athari, S. A., Adaoglu, C., & Bektas, E. (2016). Investor protection and dividend policy: The case of Islamic and conventional banks. Emerging Markets Review, 27, 100–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ememar.2016.04.001

- Athari, S. A. (2022a). Examining the impacts of environmental characteristics on Shariah-Based Bank’s Capital Holdings: Role of country risk and governance quality. The Economics and Finance Letters, 9(1), 99–109. https://doi.org/10.18488/29.v9i1.3043

- Athari, S. A., & Bahreini, M. (2021). The impact of external governance and regulatory settings on the profitability of Islamic banks. Evidence from Arab Markets. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 2021, 1–24.

- Bank of Uganda Supervision Report. (2022). Retrieved from https://www.bou.or.ug/bouwebsite/Supervision/.

- Bank of Uganda Annual Supervision Report. (2020). Retrieved March 27, 2020, from https://www.bou.or.ug/bou/ bouwebsite/bouwebsitecontent/Supervision/Annual_Supervision_Report/asr/Annual- Supervision-Report-2021.pdf.

- Bank of Uganda (BOU) website, (2020). https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.bou.or.ug%2Fbou%2Fbouwebsite%2FRelatedPages%2FPublications%2Farticle-v2%2F.

- Baker, T. A., Lopez, T. J., Reitenga, A. L., & Ruch, G. W. (2019). The influence of CEO and CFO power on accruals and real earnings management. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, 52(1), 325–345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-018-0711-z

- Bartov, E., Gul, F. A., & Tsui, J. S. L. (2000). Discretionary accruals models and audit qualifications. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 30(3), 421–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-4101(01)00015-5

- Bebchuk, L. A., Cremers, K. M., & Peyer, U. C. (2011). The CEO pay slice. Journal of Financial Economics, 102(1), 199–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2011.05.006

- Belal, A. R., & Owen, D. (2007). The views of corporate managers on the current state of, and future prospects for, social reporting in Bangladesh: An engagement-based study. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 20(3), 472–494. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513570710748599

- Bradburn, M. N., Sudman, S., & Wansik, B. (2004). Asking Questions: The Definitive guide to questionnaire design-for Market Research, Political polls and Social and Health Questionnaires. Revised ed, Jossey-Bass.

- Benkraiem, R., Ben Saad, I., & Lakhal, F. (2021). New insights into IFRS and earnings quality: What conclusions to draw from the French experience. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 22(2), 307–333. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAAR-05-2020-0094

- Brahem, E., Depoers, F., & Lakhal, F. (2022). Corporate social responsibility and earnings quality in family firms. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 23(5), 1114–1134. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAAR-05-2021-0139

- Cai, Y., & Mehari, Y. (2015). The use of institutional theory in higher education research. Theory and Method in Higher Education Research (Theory and Method in Higher Education Research, Vol. 1, pp. 1–25), Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Choi, H. (2015). Agency Dilemma: A theory of shirking, embezzlement, and bribery prevention: A theory of out-sourcing and privatization: A theory of cooperation. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2618155

- Cormier, D., Lapointe-Antunes, P., & Magnan, M. (2016). CEO Power and CEO hubris: A prelude to financial misreporting. Management Decision, 54(2), 522–554. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-04-2015-0122

- Davidson, R., Goodwin-Stewart, J., & Kent, P. (2005). Internal governance structures and earnings management. Accounting and Finance, 45(2), 241–267. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-629x.2004.00132.x

- Dechow, P. M., & Schrand, C. M. (2004). Earnings quality. The Research Foundation of CFA Institute. https://doi.org/10.2469/cp.v2004.n3.3394

- Dechow, P., Ge, W., & Schrand, C. (2010). Understanding earnings quality: A review of the proxies, their determinants and their consequences. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 50(2–3), 344–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2010.09.001

- Dechow, P. M., & Dichev, I. D. (2002). The quality of accruals and earnings: The role of accrual estimation errors. The Accounting Review, 77(s-1), 35–59. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2002.77.s-1.35

- Deegan, C. (2014). Financial accounting theory (4th Ed.). McGraw Hill.

- Demerjian, P. R., Lev, B., Lewis, M. F., & McVay, S. E. (2013). Managerial ability and earnings quality. The Accounting Review, 88(2), 463–498. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-50318

- Dillman, D. A. (1991). The design and administration of surveys. Annual Review of Sociology, 17(1), 225–249. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.so.17.080191.001301

- Duong, L., Evans, J., & Truong, T. P. (2020). Getting CFO on board – Its impact on firm performance and earnings quality. Accounting Research Journal, 33(2), 435–454. https://doi.org/10.1108/ARJ-10-2018-0185

- Dutillieux, W., Francis, R. J., & Willekens, M. (2016). The spillover of SOX on earnings quality in Non-U.S. Jurisdictions. Accounting Horizons, 30(1), 23–39. https://doi.org/10.2308/acch-51241

- Ege, M. S. (2015). Does internal audit function quality deter management misconduct? The Accounting Review, 90(2), 495–527. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-50871

- Egbunike, C. F., & Odum, A. N. (2018). Board leadership structure and earnings quality: Evidence from quoted manufacturing firms in Nigeria. Asian Journal of Accounting Research, 3(1), 82–111. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJAR-05-2018-0002

- Electricity Act. (2022). Retrieved December 2, 2022, from https://www.parliament.go.ug/cmis/views/55f31964-4064- 4a6a-97bd-adeae2d195cb%253B1.0.pdf.

- Endaya, K.A., & Hanefah, M.M. (2016). Internal auditor characteristics, internal audit effectiveness, and moderating effect of senior management. Journal of Economic and Administrative Sciences, 32(2), 160–176. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEAS-07-2015-0023.

- Elzahaby, A. M. (2021). How firm Performance mediates the relationship between corporate governance quality and earnings quality. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies, 11(2), 278–311. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAEE-09-2018-0100

- Faricha, F. (2017). Relationship of earnings management and earnings quality before and after IFRS Implementation in Indonesia. European Research Studies Journal, XX(4B), 70–81.

- Feng, M., Ge, W., Luo, S., & Shevlin, T. (2011). Why do CFOs become involved in material accounting manipulations? Journal of Accounting and Economics, 51(1–2), 21–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2010.09.005

- Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics (4th ed.). SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Finkelstein, S. (1992). Power in top management teams: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Academy of Management Journal, 35(3), 505–538. https://doi.org/10.2307/256485

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Francis, J., Huang, A. H., Rajgopal, S., & Zang, A. Y. (2008). CEO reputation and earnings quality. Contemporary Accounting Research, 25(1), 109–147., https://doi.org/10.1506/car.25.1.4

- Francis, J., Olsson, P., & Schipper, K. (2006). Earnings Quality. Foundations and Trends® in Accounting, 1(4), 259–340. https://doi.org/10.1561/1400000004

- Freeman, R. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Pitman.

- Freeman, R. E., Harrison, J. S., Wicks, A. C., Parmar, B., & de Colle, S. (2010). Stakeholder theory: The state of the art. Cambridge University Press.