?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study examined the effects of corporate social responsibility (CSR) behaviours, mechanisms, and initiatives on the involvement of mining companies in Ghana. Longitudinal data was collected from the Ghana Chamber of Mines and Industry between 2012 to 2022. Using a co-integration approach, the study examines the relationship between various factors and CSR engagement in the Ghanaian context. The study adopted a probabilistic model to measure the robustness of CSR behaviour on CSR mechanisms and initiatives. However, no positive correlation existed between partnerships and CSR engagement, implying that any discrepancy could be attributed to contextual factors in the studied industries. While this study identifies a negative relationship with partnerships, it also highlights the positive impact of voluntary programmes on CSR engagements. Therefore, it is recommended that aligning CSR initiatives with appropriate mechanisms would enable companies to effectively and efficiently pursue their CSR objectives since CSR is integral to modern business practices.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

In recent studies, the landscape of management systems and technological adoption have been a focus, shedding light on the transformative impact of Industry 4.0 and crisis contexts on various industries (Rehman et al., Citation2023). Furthermore, research by Yu et al. (Citation2022) emphasizes the evolving role of social media applications, particularly in the context of crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic, and their influence on communication paradigms within the business sphere. While these studies provide valuable insights into management adaptations, technological adoption, and the influence of crisis contexts on business paradigms, there remains a notable gap concerning the specific interrelation of these factors in driving Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) behaviours in specific regions, such as Ghana. Similarly, the study by Yu et al. (Citation2022) delves into the role of social media applications in altering business communication paradigms, particularly amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Although insightful, the direct implications of these communication shifts on CSR initiatives in specific regional contexts, such as Ghana, are not explicitly addressed. Rehman et al. (Citation2023) focused on the use of technology in reshaping human management systems in the face of financial crises and the onset of industry studies. Many of the studies also suggest that CSR is a significant contributor to or challenge to an organization’s competitive competency (Amran et al., Citation2014; Friedman, Citation2007; Jamali et al., Citation2015). Some of these studies saw CSR as an altruistic gesture that went against the organization’s financial interests (Porter & Kramer, Citation2006; Yasin et al., Citation2023). This happens because it aims to redirect lawful resources from shareholders to enterprises that do not immediately benefit from them (Shah et al., Citation2023), aligning with the stockholder theory of CSR as advocated by (Barlow, Citation2022; Marfo et al., Citation2015; Thien, Citation2015; and Turker, Citation2015).

Other researchers, on the other hand, consider CSR as a voluntary activity that goes beyond a company’s legitimate and legal obligations and financial motives (Lim & Varottil, Citation2022; Amahalu & Okudo, Citation2023). It is regarded from the perspective of strategic thinking, in which the organization utilizes CSR as an opportunity to obtain social legitimacy. This legitimacy can then be used to elicit social support for its products and services in an increasingly competitive commercial climate. This perspective does not prejudice the fact that some parts of corporate social responsibility are backed by legislation and enforced with the utmost vigour in particular jurisdictions (Hickman, Citation2014; Klettner et al., Citation2014; Lim & Varottil, Citation2022; Macdonald, Citation2011).

In another sense, the individuals who see CSR from a simply willful and vital perspective consider it to be a responsibility for future return that reflects both hierarchical norms and the most common way of making esteem opportunity for innovation-enhancing competitiveness (Fekete & Boda, Citation2012; Griffin & Prakash, Citation2014; Kim et al., Citation2012; Portalanza-Chavarría & Revuelto-Taboada, Citation2023). It is important to point out that Abbas et al. (Citation2022) studied how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected the tourism and hospitality sectors, paying particular attention to how hospitality businesses might reinvent themselves in response to the pandemic’s obstacles and develop new business models to support affected host societies. Wang et al. (Citation2023) explored how economic corridors and tourism affected the standard of living in nearby towns using the framework of the One Belt One Road plan. It probably explores how significant infrastructural improvements and tourism growth impact the lives and livelihoods of local communities. Li et al. (Citation2022) discussed how cultural tourism can be a catalyst for social entrepreneurs to contribute to environmental conservation while creating social value. Yu et al. (Citation2022) explored the evolving landscape of business communication in the context of social media applications, with a particular focus on the impact of COVID-19 knowledge, social distancing measures, and preventive attitudes. It further discussed how businesses have adapted to the changing communication paradigm during the pandemic and the psychological factors influencing these adaptations.

A cursory look at relevant literature suggests that CSR practices, especially within a developing economic context like Ghana, remain an unexplored domain. Hence, this present study seeks to bridge this gap by examining the effects of diverse CSR mechanisms and initiatives on CSR involvement by Ghana mining companies using an ensemble of statistical techniques on longitudinal data collected from the Ghana Chamber of Mines and Industry from 2012 to 2023. The specific initiatives include functional initiatives such as human resource, marketing, and supply chain and cross-functional initiatives such as initiatives development of corporate governance and environment. Also, the CSR Mechanisms of interest include unilateral mechanisms such as firm directed and foundations together with collaborative mechanisms such as partnerships and voluntary programmes. Thus, this present study seeks to move the CSR debate to a new paradigm, by examining the effects of CSR mechanisms and initiatives on the CSR involvement of mining companies in Ghana. Therefore, the objective of this study is to test if there is a positive relationship between firm-directed, foundational-directed, and involvement in CSR.

2. Literature review

2.1. What is CSR

Bowen (Citation1953) indicated that the definition of CSR describes the fact that businessmen and academicians are assisted in making decisions regarding policies and programmes that are acceptable activities as they pursue societal values and their goals (Bowen Citation1953; Park & Levy, Citation2014). The influential work Bowen conducted earlier in academic literature, as well as researchers such as Okpara and Idowu (Citation2013), and others confirm Bowen’s title of father of CSR. Over the last six decades, Carroll’s definitional framework has dynamically evolved to align with the evolving landscape of CSR within the business realm (Pedersen, Citation2015). According to Carroll, the evolution of CSR includes themes such as corporate social performance (CSP), business ethics, and stakeholder theories. Additionally, Carroll’s description of CSR themes was based on a developed economy perspective. The primary source for the definition of CSR used in this study is the United Nations Industrial Development Organization definition. According to this organization, corporate social responsibility refers to the way an organization integrates environmental and social concerns into its business operations with stakeholders (Kramar, Citation2014). In putting up a definition like this, the managers hope to assist companies in achieving unbiased social intervention issues like economic, environmental, health, and social imperatives to create an equitable distribution of wealth in society. However, upon examination of the current corporate social responsibility literature, it becomes evident that the subject presents itself as a highly complex endeavour. Its specific parameters are not entirely clear for ordinary understanding, especially concerning the extent to which it encompasses business operational behaviours. The nature of this complex system has been the factor influencing a range of definitions that have been ideal for many researchers in the corporate social responsibility arena (Carroll et al., Citation2014). Despite the challenges in putting the programme into practice, there is no doubt that a fundamental system of beliefs underlies the study of corporate social responsibility and defines or organises the activities and efforts of the subject into clear considerations of ‘what is’ and ‘what is not’ corporate social responsibility (Ullah, Citation2014).

Al Halbusi et al. (Citation2023) examined how tourists’ online information influences their dine-out behaviour, highlighting the moderating effects of country of origin in decision-making processes. Micah et al. (Citation2023) provide insights into global investments in pandemic preparedness, specifically focusing on the allocation of resources toward health systems and pandemic response. In the context of Corporate Social Responsibility, these technological innovations become crucial tools for disseminating information, engaging stakeholders, and implementing initiatives. By incorporating the insights from Micah et al. (Citation2023) and Al Halbusi et al. (Citation2023), this study aims to examine the influence and potential of technological and virtual platforms in shaping CSR initiatives within the specific socio-economic landscape of Ghana. The integration of these findings will not only contribute to the existing literature but will also provide an understanding of the interplay between technological innovations and CSR behaviours amid crisis contexts.

Liu et al. (Citation2022) provide crucial insights into how businesses navigate challenging periods like the COVID-19 crisis. Their study underscores the essential role of innovation and adaptability in not just surviving but thriving amidst adversity. The research highlights how important it is for businesses to adapt to new ideas and think creatively like entrepreneurs. This helps them stay strong during tough financial times and come out even stronger. However, the study mainly looks at how businesses can change in general but does not directly look into how this affects CSR initiatives or how it applies to a specific place like Ghana. Shah et al. (Citation2023) explore the relationship between waste management, renewable electricity generation, and the influence of environmental policies. Their research emphasizes the critical role of effective policies in shaping environmental practices and resource utilization for sustainable energy creation. However, the study primarily focuses on environmental aspects and lacks a direct connection to the field of Corporate Social Responsibility in the Ghanaian context. While environmental sustainability is a significant aspect of CSR, the study does not explicitly address the broader CSR practices, community engagement, or the socio-economic implications of their findings.

Mubeen et al. (Citation2021) investigate the relationship between product market competition, firm performance, and the influence of capital structure and firm size. The study underscores the importance of understanding market dynamics and adapting business strategies to compete effectively. Although it offers valuable insights into how businesses respond to competitive environments, it lacks direct implications for CSR practices. Understanding how innovation and adaptive strategies in competitive markets might influence CSR initiatives and business behaviours in the Ghanaian context would further enrich the applicability of their findings. While these studies provide valuable insights into specific aspects of business adaptability, environmental sustainability, and market competition, there is a gap in directly addressing the impact of these factors on Corporate Social Responsibility practices in the context of Ghana.

CSR has emerged as a significant strategic tool for companies, offering multifaceted competitive advantages. Studies such as the work by Aguilera-Caracuel and Guerrero-Villegas (Citation2012) examining the risk and return characteristics of socially responsible firms, consistently reinforce the idea that investing in CSR can contribute to enhanced financial performance and stability. According to Moneva et al., (Citation2014), firms engaging in CSR practices tend to cultivate a positive corporate image and reputation, fostering trust among stakeholders, which can result in increased customer loyalty and a stronger market position. This research underscores how firms engaging in CSR practices tend to exhibit more robust financial performance, demonstrating lower volatility and greater resilience in challenging economic periods. Such stability in financial performance is a key competitive advantage, as highlighted by these earlier studies. One fundamental aspect contributing to competitive advantage is the enhancement of a company’s reputation and brand image. Additionally, the research by Garriga and Melé (Citation2004), emphasizes the importance of CSR in attracting and retaining talent. Companies actively engaged in CSR initiatives tend to attract skilled employees who seek purpose-driven workplaces. The retention of talented individuals translates into a more motivated and productive workforce, fostering a competitive advantage through human capital. Also, studies, such as the work by González-Benito and González-Benito (Citation2006), highlight CSR’s role in stimulating innovation. Firms committed to CSR often invest in sustainable and innovative practices, enabling them to adapt to market changes effectively. This innovative edge positions them competitively by differentiating their products and services in the marketplace.

Furthermore, the study conducted by Lozano-García et al. (Citation2009), emphasizes that CSR investments offer an avenue for bolstering reputation and brand image. Companies actively involved in CSR initiatives tend to cultivate positive brand perceptions, trust, and goodwill among stakeholders, resulting in increased customer loyalty and a competitive edge in the market. This aligns with more recent literature suggesting that a positive reputation garnered through CSR can serve as a differentiator, attracting customers and stakeholders who value socially responsible practices (Carroll & Shabana, Citation2010). Moreover, such as the work by Rodriguez-Dominguez et al. (Citation2009), highlight the link between CSR investments and access to capital. Firms that prioritize CSR activities may enjoy better access to financial resources and lower costs of capital due to heightened investor confidence. Investors increasingly consider environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors in their decision-making processes, favouring companies with strong CSR profiles, thus providing a competitive advantage through easier access to funds.

Moreover, the financial performance of companies investing in CSR appears to exhibit greater stability, as highlighted in research by Cuadrado-Ballesteros and Peña (Citation2019). During periods of economic uncertainty or downturns, firms that integrate CSR into their core strategies tend to display more resilient financial performance, experiencing lower volatility in stock prices and demonstrating a degree of insulation from certain risks. This underscores CSR’s role as a risk mitigation tool and suggests that it can contribute to a competitive edge by enhancing financial robustness. Besides, the connection between CSR investments and access to capital is emphasized in studies such as the work of Fernandez-Feijoo et al. (Citation2014). The research indicates that socially responsible firms may have better access to capital markets and potentially lower costs of capital. Investors increasingly consider environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors, making firms with strong CSR profiles more attractive investment options, thereby granting a competitive advantage through easier access to funding. In addition to financial benefits, CSR initiatives impact employee attraction and retention, as outlined in the research by Abdelfattah and Aboud (Citation2020). Companies committed to CSR tend to attract and retain top talent more effectively, enhancing employee satisfaction and motivation. Employees align themselves with organizations that demonstrate a commitment to societal and environmental causes, leading to a more engaged and productive workforce. This advantage in human capital contributes significantly to overall competitiveness. Lastly, CSR investments foster innovation and effective risk management strategies within organizations. Studies, indicate that engaging in CSR encourages companies to develop innovative and sustainable products and processes. Moreover, by proactively addressing societal and environmental concerns, firms can mitigate operational risks and navigate regulatory uncertainties more effectively, positioning themselves competitively within their industries.

2.2. CSR initiatives

To enhance the applicability of their findings, studying how innovation and adaptive strategies in competitive markets could influence CSR initiatives and business behaviours in the Ghanaian context is crucial. Drives can combine accomplice/partner and issue-arranged activities. Again, CSR initiatives might begin from issues considering the method of the business, for instance, contamination from enormous scope mining creation processes or the need to shield the most minimal expense from a worldwide inventory network in light of outrageous serious powers. The study ordered drives into cross-functional and functional classes to check out the far-reaching extent of CSR experts and associations might associate with (Fernie et al., Citation2015; Johnson & Schaltegger, Citation2015; Marfo, Citation2019; Sroufe et al., Citation2014; West et al., Citation2015; Wu et al., Citation2014).

CSR has become a pivotal aspect of modern business strategy, with chief executive officers (CEOs) playing a crucial role in shaping their organizations’ ethical orientation. The inclination of CEOs towards CSR initiatives significantly influences firms’ behaviours, especially in international contexts. According to Porter and Kramer (Citation2011), companies integrating social and environmental concerns in their strategies tend to foster cooperative relationships by aligning values with stakeholders’ interests. CEOs with a strong CSR orientation not only prioritize profitability but also consider the impact of their actions on society, thereby enhancing the firm’s reputation and fostering collaboration with international partners. Ethics-oriented companies, driven by a robust set of values, possess a competitive advantage in international scenarios (González-Moreno et al., Citation2019; Ruiz Palomino et al., Citation2011). Such firms establish a strong ethical framework that guides decision-making and shapes organizational culture. Freeman (Citation2010) contends that ethical values create a foundation for trust-building among diverse stakeholders, which is crucial for successful cooperation in global markets. CEOs leading morally conscious companies set standards that resonate across borders, attracting partners who share similar values, thereby strengthening cooperation and collaboration on an international scale. Morality within business organizations transcends a mere philosophical concept; it serves as a strategic asset for effective management. Schwartz (Citation2020) argues that embedding ethics within the organizational fabric creates resilience and sustainability, offering a strategic edge in navigating complex international landscapes. CEOs focusing on strategic CSR initiatives develop resilient business models that not only generate profits but also contribute positively to societal well-being. This strategic alignment of values not only fosters cooperation but also helps companies adapt and thrive amidst diverse international challenges.

Furthermore, the ethical stance of CEOs influences stakeholder perceptions, impacting the firm’s relationships and cooperation in international markets. A study by Agle et al. (Citation2019) emphasizes that stakeholders are more inclined to engage with companies that demonstrate a commitment to ethical principles, fostering long-term partnerships in international business endeavours. CEOs championing CSR initiatives create a positive image for their firms, attracting like-minded partners interested in collaborating with socially responsible entities. Consequently, such partnerships are more likely to flourish due to shared values and a mutual understanding of ethical responsibilities. CEOs’ emphasis on Corporate Social Responsibility significantly impacts firms’ cooperation in international scenarios. Ethical orientation not only enhances a firm’s reputation and stakeholder trust but also creates a strategic advantage in global markets. Companies led by morally-conscious leaders foster collaboration by aligning values with partners, thereby contributing to sustainable and mutually beneficial relationships across borders. This underscores the critical role of CEOs in shaping organizational ethics and steering firms towards responsible and cooperative behaviours in international settings.

2.3. Functional initiatives

Functional initiatives encompass targeted strategic efforts aimed at optimizing specific functional areas within organizations to achieve enhanced performance and efficiency. For instance, initiatives like ‘Talent Development Programmes’ in Human Resources (Smith, Citation2020) focus on honing employee skills to align with organizational goals, while ‘Customer Relationship Management (CRM)’ systems in Marketing (Johnson et al., Citation2019) prioritize personalized customer interactions and retention. Additionally, within Operations Management, the adoption of ‘Lean Manufacturing’ methodologies (Brown, Citation2021) emphasizes process optimization and waste reduction to bolster productivity, minimize costs, and uphold quality standards. These initiatives serve as instrumental drivers in propelling organizational advancement by refining functional capabilities and fostering continuous improvement.

2.3.1. Human resource (HR)

These drives are facilitated by suspending the social, political, and monetary entryways for the company’s representatives, contractors, and expected labourers in the workspace and through its stock and circulation chains (Lindblom & Martins, Citation2022; Spalding, Citation2023; Zhai & Shi, Citation2022). These efforts could attempt to work on the worries of the workers of firms; give representative advantages, living wages, and proportions of safe workplaces; encourage volunteerism; or eradicate the smuggling of people. These specialists-based drives routinely have specific quantifiable outcomes: maintenance, steadfastness, certainty, and ego. Some of these initiatives might target a particular category of employees or a specific topic, such as the portrayal of women, labour unions, group traits, and disgrace, racial, social, or linguistic abilities (Azizi et al., Citation2021). Routinely planned toward partners inside the firm, the part played by the institutional accomplices (e.g. socially capable monetary experts financial backers, states) in really looking at interior workplace/work practices or giving oversight of CSR exercises bids is a piece of these valuable (HR) drives (Carroll, Citation2011; Idowu et al., Citation2014; Kaplan, Citation2015).

2.3.2. Marketing/product

Consumer-oriented CSR includes goods and services through innovative processes as well as marketing, and publicity. Green campaigns, strategic marketing, altruistic-centred donations given to specific clients, improved product usefulness (and fresh goods and services (e.g. hybrid autos, ultralight or concentrated formulations) are frequently the most visible proof of consumer-oriented CSR (Abbas et al., Citation2021). One of the important questions, which is frequently concentrated around unique and premium goods and services, is if buyers are willing to pay for true (or supposed) exhibits of the organization’s obligation.

2.3.3. Supply chain

The abovementioned efforts are meant to make sure that the required assets are bought, collected, or sold. Some examples of assets are materials, mechanicals, plants, humans, money-related properties, and some equipment. A distribution system retail or supply chain network CSR initiatives combine provider oversight with supplier codes of conduct, ethical sourcing, marking of sourced materials requirements for government Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), and carbon offsets for conveyance and transportation requirements from socially conscious financial backers. Once claimed or managed by vertically integrated enterprises, the inventory supply network project can span labour/working environment, purchaser/advancing, improvement, and ecological drives (Barrientos, Citation2013; Bowen, Citation2013; Lee, Citation2011).

2.4. Cross-functional/corporate

Cross-functional or corporate initiatives are collaborative endeavours transcending departmental boundaries to achieve overarching strategic objectives within organizations. For instance, the integration of ‘Agile Methodologies’ (Jameson, Citation2023) fosters adaptability and collaboration across departments like Marketing, IT, and Operations, promoting rapid innovation and customer-centricity (Chang et al., Citation2022). Another vital initiative is the adoption of ‘Integrated Performance Management Systems’ (Smithson & Patel, Citation2024), aligning diverse performance metrics to ensure individual goals coincide with broader organizational objectives. By amalgamating financial, operational, and strategic measures, these systems promote transparency and accountability (Brown, Citation2023), facilitating informed decision-making and resource allocation per the corporate strategy.

2.4.1. Initiatives development

These programmes are typically organized to increase social capital, empower individuals, strengthen family and business infrastructures in communities and societies, and improve general healthcare, education, and the welfare of the public. These projects may be coordinated at the neighbourhood level, among geographically adjacent groups, or among underserved portions of the general public who are not directly touched by the organization (e.g. debacle relief). The goals include the following: (1) to enhance human capacity or provide a basis for the impoverished to influence their human capital, and (2) to improve a society’s social capital (Coppa & Sriramesh, Citation2013; El Ghoul et al., Citation2011; Hilson, Citation2012; Putrevu et al., Citation2012).

2.4.2. Environment

These programmes aim to produce positive environmental externalities or externalities that benefit people and lessen the generation of negative ecological externalities connected with delivering the company’s products. These initiatives can be coordinated with particular stakeholders, for example, neighbourhood groups affected by polluted water streams or institutions comprising legislative offices, government bureaus, financial specialists, investors, or regulators (Santos, Citation2012; Schoenherr et al., Citation2014).

2.4.3. Corporate governance

These initiatives try to enhance the administration of an organization, a community of the organisations, or the industry. This is because many organisations voluntarily adopt new rules on how to do business and/or distribute extra profits. These governance activities, which are frequently started or supported by institutions, may help to protect investors, provide guidelines on corporate codes, compel financial information, reduce executive benefits, give data on stakeholder activities, or put up strict measures laying out expected corporate conduct (Epstein & Buhovac, Citation2014; Garriga & Melé, Citation2013).

2.5. CSR mechanisms

Within the classification of CSR initiatives, an assortment of mechanisms can be utilized to accomplish CSR results. CSR mechanisms decipher a company’s CSR purposes and convictions into concrete responsibilities. The basis of CSR methods is how organisations choose to apply CSR. Corporations may have a chosen method of interaction, such as internal methods and official collaboration through claims, or they may wish to collaborate with like-minded companies to change rules (Eastwood et al., Citation2022; Westman et al., Citation2023). Public-private partnerships (PPPs) and various multi-actor community-oriented causes of action have become more popular vehicles for CSR investments. This paper attempts to distinguish between unilateral firm-focused CSR systems and cooperative CSR mechanisms.

2.5.1. Unilateral mechanisms

Unilateral mechanisms encompass independent actions taken by singular entities, such as nations, to address various issues or pursue specific goals. For instance, ‘Trade Tariffs’ are imposed to rectify trade imbalances or protect domestic industries (Watson, Citation2023), often leading to trade tensions and retaliatory measures that impact global commerce (Garcia et al., Citation2022). Similarly, ‘Sanctions’ serve as tools for governments to influence behaviour or express disapproval, employing economic restrictions or diplomatic actions (Lee, Citation2024). Additionally, ‘Military Interventions’ represent unilateral actions undertaken for national security or humanitarian objectives, yet these interventions can spark geopolitical tensions, complexities in conflict resolutions, and international criticism (Adams, Citation2021; Baker et al., Citation2023). These unilateral strategies, while addressing specific concerns, often raise ethical, legal, and geopolitical dilemmas due to their unilateral nature and potential global repercussions.

2.5.1.1. Firm directed

Beyond compliance exercises, CSR indicates recognition of the allotment of a company’s unique resources (for example, money, material, and worker expertise) to some enterprises. Some of these unilateral CSR performances may be lengthy, while others too appear at regular intervals. For instance, an organization may sponsor an annual parade, employee volunteering day, fireworks, or a representative volunteerism service as an example of occasional community activities. Unilateral CSR measures can be integrated to raise product quality, make process changes (such as using less water or carbon), record and track CSR projects, or ensure moral suppliers realistically.

2.5.1.2. Foundations

Foundations aim to provide an established institutional structure that enhances developmental, ecological, general health, and other activities in developing economies. By establishing a foundation, a business entity often tries to protect its duties and pursue CSR activities outside of the corporate structure. Additionally, foundations like this are typically managed by experts who come from the nonprofit sector. Although Carnegie is recognized as the first industrialist to organise corporate donations the practice has become scattered over the globe. The Gates Foundation and the Tata Trusts and Foundations are two popular examples as far as the categorisation of CSR mechanisms is concerned (Bouilloud & Deslandes, Citation2015). The importance of individual firms is emphasised via unilateral processes. Although partners may be advised, CEOs are in charge of determining the scale and purpose of CSR. Companies, on the other hand, may endeavour to pursue CSR in a dynamic collaborative effort with other performing practitioners, as discussed below.

2.5.2. Collaborative mechanisms

Collaborative mechanisms embody collective strategies involving multiple entities or nations to address global challenges and achieve common objectives. For instance, ‘International Treaties and Agreements’ formalize mutual commitments on issues like trade, climate change, or security, fostering diplomacy and cooperation among nations (Robert, Citation2023; Nguyen & Kim, Citation2024). ‘Multilateral Alliances and Organizations’ such as the United Nations or regional blocs enable joint decision-making and resource-sharing, promoting stability and progress on a global scale through collective efforts (Perez, Citation2022; Gupta et al., Citation2023). Additionally, ‘Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs)’ leverage government and private sector strengths to deliver efficient services and innovative solutions in sectors like infrastructure and healthcare (Smith & Jones, Citation2023; Brown et al., Citation2024). These collaborative frameworks foster innovation, enhance project efficiency, and address complex societal challenges, showcasing the power of collective action in achieving sustainable development and societal progress.

2.5.2.1. Partnerships

Governments, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), and multilateral corporations could enter into joint-partnership contracts. These compacts are inclined to be contractual-concept relationships concentrated in light of accomplishing a particular goal (e.g. access to capital, streets and road building, number of individuals trained) empowering practitioners, institutions, and companies to collaborate, coordinate professionals, and give responsibility in specific regions. The goals might range from empowering local communities to aiding international programmes with budgetary growth. An organization, for instance, may collaborate with community agribusiness cooperatives and local governments to give manures, subsidise seed prices, and education on practical cultivating for sustainable farming, while guaranteeing a specified price if product standard requests are met (Epstein & Buhovac, Citation2014; Gmelin & Seuring, Citation2014; Perry et al., Citation2014).

2.5.2.2. Voluntary programmes

These are efforts that a group of firms consents to join that go beyond compliance standards (Bowen, Citation2013; Islam, Citation2015). These frameworks can be built up or managed by an industry affiliation, for example, Fair Trade, Responsible Care, The Forest Stewardship Council optional programme, the Energy Star program, the Extractive Industry Transparency Initiative (EITI), NGOs, governments, and the Equator Principles. Typically, voluntary programmes persuade businesses to adopt practices that go beyond compliance, resulting in the development of positive externalities. Instead of supporting magnanimous or altruistic objectives, these projects tend to be built up with regulatory prerequisites as the benchmark.

2.6. Relationship between firm-directed unilateral CSR mechanisms and involvement in CSR

One fundamental aspect of CSR is the choice of mechanisms through which a firm engages in socially responsible activities. Among these mechanisms, firm-directed unilateral CSR initiatives have garnered significant attention due to their potential to drive greater involvement in CSR. Firm-directed unilateral CSR mechanisms involve initiatives taken independently by a company without external pressures or collaborations. These initiatives are often proactive, driven by the firm’s internal values and commitment to societal and environmental well-being. Several studies have highlighted the propensity of such initiatives to engender a culture of CSR within organisations (Aguinis & Glavas, Citation2012). This internal commitment is a catalyst for increased involvement in CSR. Epstein and Buhovac (Citation2014) have shown that firm-directed CSR mechanisms tend to promote long-term sustainability in CSR practices. They argued that companies that take autonomous initiatives are more likely to integrate CSR into their core business strategies, making CSR a sustained, rather than ad-hoc endeavour (Abbas et al., Citation2020). This longevity in CSR involvement contributes to a positive impact on society and the environment. Stakeholders, including customers, investors, and employees, tend to view companies that take the lead in CSR as socially responsible and ethical. Griffin and Prakash (Citation2014) suggest that firm-directed CSR mechanisms can also have positive financial implications. They emphasized that companies that are actively involved in CSR tend to attract socially conscious investors and customers, potentially leading to increased revenues and shareholder value. Thus, this financial incentive further encourages companies to engage in CSR. Hence the study hypothesises that:

H1a: There is a positive relationship between firm-directed unilateral CSR mechanisms and involvement in CSR.

2.7. Relationship between foundation-directed unilateral CSR mechanism and involvement in CSR

Empirical studies have consistently demonstrated that organisations with dedicated CSR foundations or arms tend to exhibit a higher level of commitment to CSR initiatives (Amahalu & Okudo, Citation2023). These foundations specifically allocate significant financial and human resources for CSR activities. These financial and human commitments are often translated into more substantial and sustained involvement in CSR. This relationship is characterised by an enhanced commitment to CSR initiatives, alignment with organisational values, long-term sustainability, positive stakeholder perceptions, reputation building, brand enhancement, and collaborative partnerships (Mubeen et al., Citation2021). As organisations seek to make meaningful contributions to society and the environment, the understanding of the empirical evidence supporting the value of foundation-directed CSR mechanisms becomes increasingly important.

Firm-directed, foundational-directed, and partnership-directed orientations represent distinct approaches to corporate social responsibility (CSR) and ethical conduct within organizations. Firm-directed CSR focuses on aligning social responsibility efforts with the company’s core business activities, seeking to enhance operational efficiency and competitiveness while addressing societal concerns. According to McWilliams and Siegel (Citation2001), firm-directed CSR initiatives often involve integrating social and environmental considerations into business strategies, emphasizing initiatives that benefit both the company and society. This approach aims to generate value for stakeholders while concurrently pursuing corporate objectives, positioning the firm as a responsible and sustainable entity in the eyes of consumers, investors, and communities. Foundational-directed CSR, on the other hand, centres on embedding ethical values and principles into the foundational structure and culture of the organization. Carroll (Citation1991) underscores that foundational-directed initiatives focus on developing a strong ethical framework that permeates the entire organizational ethos, guiding decision-making processes and employee behaviours. This orientation prioritizes fostering an ethical climate within the company, emphasizing values such as integrity, fairness, and accountability. By institutionalizing ethical principles, foundational-directed CSR aims to create a corporate culture where ethical considerations become intrinsic to day-to-day operations and guide interactions with all stakeholders, thereby nurturing a reputation for ethical leadership and trustworthiness. Partnership-directed CSR represents a collaborative approach where businesses engage in mutually beneficial relationships with external stakeholders to address social and environmental issues. Kolk and Van Tulder (Citation2004) highlight that partnership-directed initiatives involve collaborating with NGOs, governments, other companies, or local communities to address complex societal challenges. This approach emphasizes joint efforts aimed at creating shared value by leveraging diverse expertise and resources. Partnership-directed CSR fosters cooperation and collective action, allowing companies to have a broader impact beyond their capacities, thereby contributing to more sustainable solutions to societal issues through collective efforts.

This study therefore hypothesises that:

H1b: There is a positive relationship between foundation-directed unilateral CSR mechanisms and involvement in CSR.

2.8. Relationship between partnership-directed collaborative CSR mechanisms and involvement in CSR

Several empirical studies have consistently found a positive relationship between partnership-directed collaborative CSR mechanisms and an organization’s involvement in CSR (Maas & Reniers, Citation2014). Collaborative initiatives involving partnerships with other organizations, including non-profits and government agencies, have been shown to enhance CSR engagement. These partnerships often bring diverse resources, expertise, and perspectives to CSR efforts and motivate companies to become more actively involved. In collaborative CSR programmes, multiple stakeholders jointly work toward common CSR goals. This shared commitment leads to a higher level of involvement as organisations feel accountable not only to themselves but also to their partners. Consequently, it is hypothesised in this paper that:

H2a: There is a positive relationship between partnership-directed collaborative CSR mechanisms and involvement in CSR.

2.9. Relationship between voluntary program-directed collaborative CSR mechanisms and involvement in CSR

Some studies have consistently shown that voluntary program-directed collaborative CSR mechanisms motivate organisations to broaden their involvement in CSR (Barlow, Citation2022). Voluntary programmes often encourage companies to extend their CSR efforts beyond their core operations. This broader scope of engagement is a direct result of participating in collaborative initiatives. Lee (Citation2011) reported that collaborative CSR mechanisms, particularly voluntary programmes, facilitate learning and knowledge sharing among organizations. Companies involved in such programmes tend to learn from each other’s experiences and best practices. This knowledge-sharing fosters a deeper understanding of CSR issues and motivates further involvement. Kim et al. (Citation2012) found that the positive outcomes achieved through voluntary programme-directed collaborative CSR mechanisms enhance an organization’s commitment to CSR involvement. When organisations witness tangible benefits from their collaborative efforts, such as improved reputation or community impact, they are more likely to continue and expand their CSR initiatives. These relationships are characterised by enhanced engagement, shared responsibility, resource pooling, motivation for broader involvement, learning, knowledge sharing, and positive outcomes that enhance commitment. It is very crucial to understand these positive relationships for organisations seeking to maximize their CSR impact through collaboration with other stakeholders. Taking inspiration from these papers, the study hypothesises that:

H2b: There is a positive relationship between voluntary programme-directed collaborative CSR mechanisms and involvement in CSR.

3. Methodology

For this study, the data was gathered from the Ghana Chamber of Mines and Industry’s Annual National CSR survey from 2012 to 2023. The rationale for targeting this group is that the mining sector is a significant contributor to Ghana’s GDP and plays a substantial role in the country’s economic development. The data from this sector holds relevance and importance due to its impact on the national economy and society. The extended duration of the data, from 2012 to 2023, provides a longitudinal perspective, allowing for the examination of trends, changes, and developments in CSR practices within the mining industry over a considerable period. This breadth of data enables a comprehensive analysis of how CSR initiatives have evolved and been implemented over time. Thus, given the significant economic and social impact of the mining industry on the national level, analyzing CSR practices within this industry offers insights into how these initiatives contribute to the well-being of local communities, environmental sustainability, and broader societal development in Ghana.

The co-integration approach was adopted to identify the factors that influence CSR involvement. On the level of CSR involvement, this is accomplished by examining the effects of various functional initiatives (human resource, marketing/product, supply chain), cross-functional/corporate initiatives (initiatives development, environment, corporate governance, and CSR mechanisms), unilateral mechanisms (firm directed and foundations), and cooperative mechanisms (partnerships and voluntary programmes.

3.1. Model specification

The empirical approach is based on the current study on the effect of CSR initiatives and mechanisms on CSR involvement (Aguinis & Glavas, Citation2012; Brammer et al., Citation2012; Garriga & Melé, Citation2013). The broad specification of the CSR participation Equationequation (4.1)(4.1)

(4.1) is given in the equation, which follows the literature.

(4.1)

(4.1)

Where: Y is CSR involvement; RF is variables of different CSR initiatives and mechanisms; Xn is a conditioning set of information. In this study, the major variable of interest is RF. It includes a measure of different CSR initiatives and mechanism variables which are included in the equation that measures the impact of different CSR initiatives and mechanisms on CSR involvement. This is a risk factor dummy variable (CLMDUMMY). Operational efforts (human resource marketing/product, supply chain), corporate initiatives (environment, corpkorate governance, CSR mechanisms), unilateral methods (firm-directed, foundations), and cooperative mechanisms (partnerships and volunteer programmes) are used as control variables to measure CSR involvement, according to the CSR literature. The study estimates the equation based on the prior discussion as follows:

(4.2)

(4.2)

Where: CSR efforts are represented by Y; CLDUMMY as a dummy variable representing risk factors, ε, and ξ are stochastic error terms. CIGFI is the composite score of functional initiative which is divided into three categories: human resource, marketing/product, and supply chain (Raza et al., Citation2019). CF is a cross-functional initiative that is also divided into four categories namely; initiatives development, environment, corporate governance, and CSR Mechanisms; LIUM refers to a unilateral mechanism. This is divided into two categories namely; Firm directed and Foundations. Further, LNCM refers to a collaborative mechanism. This is also divided into two categories namely; partnerships and collaborative programmes. Last but not least is the LN which stands for natural logarithm.

The characteristics of the time series variables stationarity are examined using the Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) method. When the regression models are usually non-stationary, ADF is done to avoid erroneous regressions. Thus, the order of integration will be dictated by various times when the data series are non-stationary at specific levels, such as I (0). The probability ratio test and the unit root test are both part of the co-integration test. Except for CSR involvement (Y), which is stationary at level (1), all of the variables in the units and the results in Table can be seen to be integrated in the same way. This indicates that since the time series variables are co-integrated in the same order, namely I (1), the long-run combination of the non-stationary variables may be built. To test for the number of co-integrating vectors, the study uses the (Wang’ombe, Citation2013) maximum likelihood (ML) approach, which also provides inferences on parameter restriction. H0 = Πq = αβ! is the hypothesis, where α and β! are n x r loading matrices and Eigenvectors respectively. This method’s objective is to determine the number of r co-integrating vectors β1, β2 …. βr that produce r stationary linear patterns of c.

For hypothesis testing, the linear likelihood ratio (LR) statistic is used. H0 = Πq = αβ! is a test to see if there are at least r co-integrating vectors.

4. Presentation of results

4.1. Unit root analysis

The subsequent stage presents the analysis of an error correction model after the co-integrating relationship has been established. VECM was selected because it produces more efficient co-integrating vector estimators than alternative models that could have been utilized. VECM helps to test for co-integration in an entire system of equations in one step, without having to normalise a single variable. Also, VECM has no previous assumption of endogeneity or exogeneity of the variables. Furthermore, VECM helps the study investigate Granger-sense causality. The study used a t-test to assess the error correction term, whereas the F-test was used to evaluate the lagged first-differenced term of each variable.

In this section, the study uses current time series econometric analysis of CSR engagement statistics acquired from the Ghana Chamber of Mines from 2012 to 2022 to assess the influence of different CSR initiatives and mechanism factors on CSR involvement. For empirical analysis, the study uses current econometric models such as unit root testing, co-integration, and Vector Error Correction (VECM). The short- and long-term effects of CSR activities, as well as mechanism factors, were investigated.

The results of the ADF unit root tests are shown in . Except for CSR engagement, the ADF test classifies all the examined variables as I (1), indicating that they are non-stationary at levels but become stationary after first differencing. On the other hand, CSR participation remains stationary at all levels.

Table 1. Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test results.

4.2. Co-integration test results

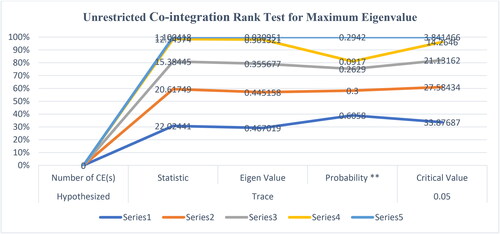

The co-integration test results are shown in and . The results, as shown below, are contradictory. The results of the trace test () demonstrate the existence of at least two co-integration equations. at 5% levels. There are two main points that this test identifies. The chosen variables will first move in lockstep over the long period, and any short-term deviations will be corrected in the direction of equilibrium. Second, co-integration establishes at least one direction of causality. On the other hand, the Rank Test (Maximum Eigenvalue: ) shows no co-integration at the 5% level. The study relies on the VECM findings to validate whether there is the existence or otherwise of the variables’ co-integration

Table 2. Unrestricted co-integration rank test (trace).

Table 3. Unrestricted co-integration rank test for maximum Eigen value.

This is because the two test results could not be validated based on the co-integration among the variables that were selected. The error correction term and its significance will determine whether or not co-integration exists. When the error correction term’s sign is negative and significant at 5%, the time series data are co-integrated with the first order I. (1). If the term of error correction sign is positive, it can be argued that the data series are not co-integrated, regardless of the significance level ().

4.3. Short-run relationship analysis

presents the initial differenced outcomes, which illustrate the short-term association between the chosen factors and CSR engagement. At both one and two-period delays, the variables of unilateral CSR mechanism have a positive short-run connection with CSR engagement. However, the focus of this research is on the one-period lag factors in the yearly series. At this time lag, a 10% increase in collaborative CSR mechanisms will result in a comparable rise in CSR engagement of around 17% in the short term. Furthermore, the functional initiative of the one-period lag variable demonstrates a positive but negligible short-run connection with CSR engagement. This means that the CSR engagement has a negative short-run relation with all of the other variables in the model. In the near term from below, a 10% rise in cross-functional CSR activities results in a 9% decrease in CSR activity in Ghana. The remaining factors were not statistically significant at one-period delays. The efficiency of the model was evaluated and determined to be reliable.

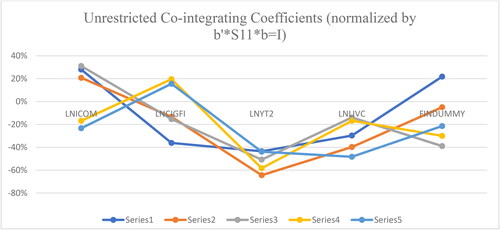

Table 4. Unrestricted co-integrating coefficients (normalized by b’*S11*b = I).

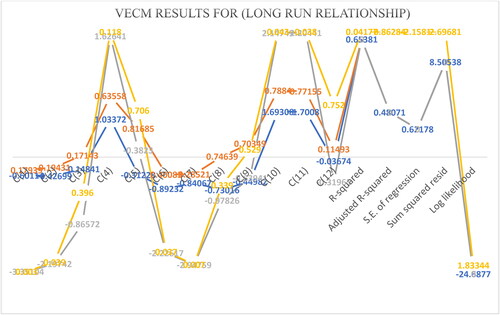

4.4. Long-run relationship analysis

The results in show that the factors have a long-term association. The value of (C1) shows the error correction term in the VECM. For a long-run association to exist, the C1 value should be negative, and its corresponding P-value should be significant at a 5% level. This is because, in , the C1 has a value of -0.60114 and a P-value of 0.003 at the 5% level of significance. As a result, the variables that are in the model match together in the long run. The implication is that the independent factors influence CSR engagement in the long run (Dependent variable). Firm-directed mechanisms and foundations have a statistically significant relationship with CSR engagement as compared to collaborative CSR mechanisms (Partnerships, Voluntary initiatives). Partnerships, on the other hand, have a negative correlation with corporate social responsibility. In the context of co-integration, a 10% increase in voluntary programmes will result in a similar rise of 18.7% in CSR activity in the long run. Furthermore, a 10% increase in firm-driven mechanisms increases CSR engagement by around 7% and 1%, respectively. Only the estimated association between Partnerships and CSR participation is meaningful. That is, while there is a long-term beneficial association between voluntary programmes and CSR participation, the relationship is statistically insignificant. The long-run estimates also show a strong negative link between the Firm-Directed Mechanism and CSR participation. CSR engagement is roughly reduced by 16.1% when Firm-driven mechanisms are increased by 10% ().

Table 5. VECM results for (Long run relationship).

5. Discussion of findings

The findings of this study corroborate with previous studies (Aguinis & Glavas, Citation2012; Amran et al., Citation2014) that firm-directed mechanisms and foundations have a positive relationship with CSR engagement. The implication here is that firm-driven CSR initiatives as a means to enhance CSR engagement play a pivotal role in harnessing CSR in organisations. Hence, it stands to reason that organisations that take the lead and decide on their own to do good things seem to have a positive impact on society. This means that companies in Ghana can play a big role in making their communities and the environment better (Ge et al., Citation2022).

However, it was found that there was no positive correlation between partnerships and CSR engagement, contrasting with the findings of Griffin and Prakash (Citation2014). Their research suggested that corporate responsibility initiatives involving collaborations can lead to an increase in CSR engagement. This implies that any discrepancy could be attributed to contextual factors or differences in the industries that were involved in the study. The exploration of collaborative CSR mechanisms used in this study such as partnerships and voluntary initiatives, builds upon the CSR model developed by Maas and Reniers (Citation2014). While this study identifies a negative relationship with partnerships, it also highlights the potential positive impact of voluntary programmes on CSR engagement. In extending the findings of Epstein and Buhovac (Citation2014) to this present study, it is important to note that there is a need to emphasise the long-term associations between CSR mechanisms and CSR engagement. The focus on managing and measuring CSR impacts in organisations aligns with the exploration of mechanisms influencing CSR behaviour in this study. Similarly, the results confirm the research by El Ghoul et al. (Citation2011) who investigate the effect of corporate social responsibility on the cost of capital. Al Halbusi et al. (Citation2023) also focused on the factors influencing technology adoption for online purchasing amid COVID-19 in Qatar. Thus, these studies affirm that there is a positive relationship between firm-directed mechanisms and CSR engagement suggesting that CSR activities can positively impact financial aspects as well.

The present study’s alignment with previous literature regarding the positive relationship between firm-directed mechanisms and CSR engagement further underlines the significance of proactive organizational initiatives in fostering societal welfare and environmental sustainability. However, the discrepancy between this study’s negative correlation with partnerships and Griffin and Prakash’s contrasting findings emphasizes the nuanced influence of context and industry dynamics on CSR engagement strategies. Additionally, the implications of long-term associations between CSR mechanisms and their measurable impacts in organizations underscore the necessity of not only implementation but continuous evaluation of CSR strategies. Furthermore, the relationship between CSR activities and financial aspects, as noted by El Ghoul et al. (Citation2011) suggests a broader impact of CSR practices on organizational performance, including financial elements. Expanding the understanding of contextual factors influencing CSR engagement and technological adoption, as hinted by Al Halbusi et al. (Citation2023) could contribute to a more comprehensive framework for integrating CSR practices within specific industries. Hence, while this study corroborates various existing research on certain aspects, it also highlights the contextual specificity and diverse influences shaping CSR engagement strategies.

6. Conclusion

This study has provided valuable insights into the dynamics of CSR practices among companies operating in Ghana, particularly within the mining sector. The study has confirmed among other things that there is a positive relationship between firm-directed, foundational-directed, and involvement in CSR. It has emphasized the critical role of responsible corporate behaviour and decision-making in impacting the well-being of the communities in which these companies operate. By utilizing a co-integration analysis framework, this research has shed light on the complex interplay of factors influencing CSR participation within these mining companies. The study emphasized the pivotal role of institutional factors in shaping specific CSR decisions, highlighting the significance of responsible corporate management practices. Furthermore, amidst the challenging landscape posed by the COVID-19 pandemic the importance of CSR in corporate strategies has been magnified. The pandemic has heightened the expectations for businesses to contribute to societal well-being during crises, emphasizing the need for companies to integrate CSR into their core strategies and operations.

It is strongly recommended that businesses align their CSR initiatives with effective implementation mechanisms. This alignment is crucial not only for navigating crises such as the ongoing pandemic but also for creating a sustainable and positive impact on society and organizations in the long term. The study’s findings underscore the significance of integrating CSR practices into the core fabric of businesses, not just as a reactionary measure in times of crisis, but as an intrinsic and enduring element of corporate strategy. Expanding on these findings and aligning CSR initiatives with robust implementation strategies would not only assist companies in managing and responding to crises like the COVID-19 pandemic, but also contribute to fostering resilient and socially responsible businesses. This alignment is essential for the enduring success and resilience of businesses, not only in Ghana but also in a broader global context.

6.1. Policy recommendations

The implementation of these policy recommendations for Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) in Ghana involves the collaboration and effort of various key actors. These may include:

Government bodies and regulatory authorities: Government institutions play a significant role in enacting and enforcing policies that incentivize CSR practices. They can provide regulatory frameworks, tax incentives, and legal structures that encourage businesses to engage in CSR initiatives.

Private businesses and corporations: Businesses themselves are crucial actors in implementing CSR initiatives. They are encouraged to take the lead in adopting and implementing CSR policies, not only as a social responsibility but also for sustainable business practices.

Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) and civil society: NGOs and civil society organizations often work in collaboration with businesses and government bodies to address social and environmental issues. They can partner with businesses to develop and implement CSR programmes that address specific community needs.

Industry associations and trade groups: Associations and industry groups can play a significant role in promoting and sharing best practices for CSR within specific sectors. They can facilitate knowledge sharing and collaboration among businesses, encouraging them to adopt and implement CSR initiatives.

Educational institutions and research organizations: These entities can contribute by conducting research, sharing knowledge, and providing training programmes that could focus on CSR. They can educate future business leaders and employees about the importance and strategies of CSR.

Media and public influencers: They can create awareness and highlight the importance of CSR practices. Through their influence, they can encourage businesses and the public to engage in responsible and sustainable practices.

Collaboration among these key actors is vital for the successful implementation of CSR policies and initiatives. Their concerted efforts and partnerships can contribute to a more comprehensive and effective integration of CSR practices within Ghana’s business landscape.

6.2. Limitations and suggestions for future research

It is important to point out that the study has focused on a specific sample of companies or industries in Ghana, which may not be representative of the entire corporate landscape. This could lead to selection bias and limit the generalisability of findings.

Given the nature of this study, it is recommended that future researchers consider a longitudinal study that examines the long-term impact of CSR initiatives in Ghana. This could involve tracking the social and environmental outcomes of CSR practices over several years to assess their sustainability and effectiveness. Such studies could investigate how CSR mechanisms and initiatives vary across different sectors and their implications for sustainable development. There is potential for diverse research analyzing how global events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic or climate change, may influence CSR practices and priorities in Ghana.

Ethical approval

The research activities that involved human behaviours complied with both institutional and national standards of research in Ghana.

Acknowledgement

I would like to express my appreciation to the Ghana Chamber of Mine and Industry.

Disclosure statement

Author has no potential conflict of interest to report.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Emmanuel Opoku Marfo

Emmanuel Opoku Marfo (Ph.D, FCMC. FChPA) is the Acting Dean of the School of Arts and Social Sciences at the University of Energy and Natural Resources, Sunyani, Ghana. Commissioner, at the National Development Planning Commission. I earned my Bachelor of Arts degree in Accounting and Finance from the University of Lincoln, England, in the United Kingdom in 2004. Subsequently, I pursued a Master of Business Administration in Finance at the same University of Lincoln. In 2016, I earned a PhD in Management Science and Engineering with a major in Corporate Finance from Jiangsu University, China. I have been trained as an Associate Member of the Institute of Chartered Management, UK, and a Fellow Chartered Management Consultant, in Ghana.

Reference

- Abbas, J.,Mubeen, R.,Iorember, P. T.,Raza, S., &Mamirkulova, G. (2021). Exploring the impact of COVID-19 on tourism: transformational potential and implications for a sustainable recovery of the travel and leisure industry. Current Research in Behavioral Sciences, 2, 1 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crbeha.2021.100033

- Abbas, J., Al-Sulaiti, K., Lorente, D. B., Shah, S. A. R., & Shahzad, U. (2022). Reset the industry redux through corporate social responsibility: The COVID-19 tourism impact on hospitality firms through business model innovation. In Economic growth and environmental quality in a post-pandemic world (pp. 1–24). Routledge.

- Abbas, J., Mahmood, S., Ali, H., Ali Raza, M., Ali, G., Aman, J., Bano, S., & Nurunnabi, M. (2019). The effects of corporate social responsibility practices and environmental factors through a moderating role of social media marketing on sustainable performance of business firms. Sustainability, 11(12), 3434. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11123434

- Abbas, J., Zhang, Q., Hussain, I., Akram, S., Afaq, A., & Shad, M. A. (2020). Sustainable innovation in small medium enterprises: the impact of knowledge management on organizational innovation through a mediation analysis by using SEM approach. Sustainability, 12(6), 2407. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062407

- Abdelfattah, T., & Aboud, A. (2020). Tax avoidance, corporate governance, and corporate social responsibility: The case of the Egyptian capital market. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, 38, 100304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intaccaudtax.2020.100304

- Adams, R. (2021). Military interventions and global politics. International Relations Journal, 25(3), 87–102.

- Agle, B. R., Mitchell, R. K., & Sonnenfeld, J. A. (2019). Who matters to CEOs? An investigation of stakeholder attributes and salience, corporate performance, and CEO values. Academy of Management Journal, 42(5), 507–525. https://doi.org/10.2307/256973

- Aguilera-Caracuel, J., & Guerrero-Villegas, J. (2012). How corporate social responsibility helps MNEs to improve their reputation. The moderating effects of geographical diversification and operating in developing regions. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 25(4), 355–372. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1465

- Aguinis, H., & Glavas, A. (2012). What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility a review and research agenda. Journal of Management, 38(4), 932–968. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311436079

- Al Halbusi, H.,Al-Sulaiti, K.,AlAbri, S., &Al-Sulaiti, I. (2023). Individual and psychological factors influencing hotel employee’s work engagement: The contingent role of self-efficacy. Cogent Business and Management, 10(3), 2254914.

- Amahalu, N. N., & Okudo, C. L. (2023). Effect of corporate social responsibility on financial performance of quoted oil and gas firms in Nigeria. Research Journal of Management Practice, 3(3), 25–38. ISSN, 2782, 7674.

- Amran, A., Lee, S. P., & Devi, S. S. (2014). The influence of governance structure and strategic corporate social responsibility toward sustainability reporting quality. Business Strategy and the Environment, 23(4), 217–235. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.1767

- Azizi, M. R.,Atlasi, R.,Ziapour, A.,Abbas, J., &Naemi, R. (2021). Innovative human resource management strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic narrative review approach. Heliyon, 7(6).

- Baker, M.,Peterson, S., &Campbell, L. (2023). Geopolitical implications of unilateral military actions. Global Affairs Review, 18(2), 145–160.

- Barlow, R. (2022). Deliberation without democracy in multi-stakeholder initiatives: A pragmatic way forward. Journal of Business Ethics, 181(3), 543–561. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-04987-x

- Barrientos, S. W. (2013). ‘Labour chains’: analysing the role of labour contractors in global production networks. Journal of Development Studies, 49(8), 1058–1071. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2013.780040

- Bouilloud, J.-P., & Deslandes, G. (2015). The Aesthetics of Leadership: Beau Geste as Critical Behaviour. Organization Studies, 36(8), 1095–1114. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840615585341

- Bowen, H. R. (1953). Graduate education in economics. The American Economic Review, 43(4).

- Bowen, H. R. (2013). Social responsibilities of the businessman. University of Iowa Press.

- Brammer, S., Jackson, G., & Matten, D. (2012). Corporate social responsibility and institutional theory: New perspectives on private governance. Socio-Economic Review, 10(1), 3–28. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwr030

- Brown, E.,Garcia, R., &Martinez, C. (2024). Public-private partnerships: Innovations in collaborative development. Journal of Public Policy and Development, 20(3), 150–165.

- Brown, D. (2023). Transparency and accountability through integrated performance management system. Journal of Corporate Governance, 22(1), 55–68.

- Brown, R. (2021). Lean manufacturing initiatives: Optimizing operations for increased productivity and quality. Operations Management Journal, 25(4), 210–225.

- Carroll, A. B. (1991). The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Business Horizons, 34(4), 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/0007-6813(91)90005-G

- Carroll, C. E. (2011). Media relations and corporate social responsibility. In Handbook of communication and corporate social responsibility (pp. 423–444). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Carroll, R., Metcalfe, C., & Gunnell, D. (2014). Hospital presenting self-harm and risk of fatal and non-fatal repetition: systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One, 9(2), e89944. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0089944

- Carroll, A. B., & Shabana, K. M. (2010). The business case for corporate social responsibility: A review of concepts, research and practice. International Journal of Management Reviews, 12(1), 85–105. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2009.00275.x

- Chang, L.,Martinez, R., &Rodriguez, J. (2022). Agile frameworks in diverse departments: Fostering innovation and customer-centricity. Journal of Business Collaboration, 12(3), 78–92.

- Coppa, M., & Sriramesh, K. (2013). Corporate social responsibility among SMEs in Italy. Public Relations Review, 39(1), 30–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2012.09.009

- Cuadrado-Ballesteros, B., & Peña, M. N. (2019). Is privatization related to corruption? An empirical analysis of European countries. Public Management Review, 21(1), 69–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2018.1444192

- Eastwood, A., Fischer, A., Hague, A., & Brown, K. (2022). A cup of tea?—The role of social relationships, networks and learning in land managers’ adaptations to policy change. Land Use Policy, 113, 105926. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105926

- El Ghoul, S., Guedhami, O., Kwok, C. C., & Mishra, D. R. (2011). Does corporate social responsibility affect the cost of capital? Journal of Banking & Finance, 35(9), 2388–2406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2011.02.007

- Epstein, M. J., & Buhovac, A. R. (2014). Making sustainability work: Best practices in managing and measuring corporate social, environmental, and economic impacts. (2nd ed., pp. 324). Routledge.

- Fekete, L., & Boda, Z. (2012). Knowledge, sustainability and corporate strategies in the European energy sector. International Journal of Environmental Studies, 69(2), 360–377. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207233.2012.663542

- Fernandez-Feijoo, B., Romero, S., & Ruiz, S. (2014). Commitment to corporate social responsibility measured through global reporting initiative reporting: Factors affecting the behavior of companies. Journal of Cleaner Production, 81, 244–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.06.034

- Fernie, J., Fernie, S., & Moore, C. (2015). Principles of retailing (2nd ed., pp. 368). Routledge.

- Freeman, R. E. (2010). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Cambridge University Press.

- Friedman, M. (2007). The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. In: Zimmerli, W.C., Holzinger, M., Richter, K. (eds.), Corporate Ethics and Corporate Governance (pp. 173-178). Springer.

- Garcia, E.,Martinez, P., &Nguyen, T. (2022). Trade tariffs and their impacts on global commerce. International Trade Perspectives, 12(4), 220–235.

- Garriga, E., & Melé, D. (2004). Corporate social responsibility theories: Mapping the territory. Journal of Business Ethics, 53(1/2), 51–71. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:BUSI.0000039399.90587.34

- Garriga, E., & Melé, D. (2013). Corporate social responsibility theories: Mapping the territory. In Citation classics from the journal of business ethics (pp. 69–96). Springer.

- Ge, T., Abbas, J., Ullah, R., Abbas, A., Sadiq, I., & Zhang, R. (2022). Women’s entrepreneurial contribution to family income: innovative technologies promote females’ entrepreneurship amid COVID-19 crisis. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 828040. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.828040

- Gmelin, H., & Seuring, S. (2014). Determinants of a sustainable new product development. Journal of Cleaner Production, 69, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.01.053

- González-Benito, J., & González-Benito, Ó. (2006). A review of determinant factors of environmental proactivity. Business Strategy and the Environment, 15(2), 87–102. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.450

- González-Moreno, Á., Ruiz-Palomino, P., & Sáez-Martínez, F. J. (2019). Can CEOs’ Corporate social responsibility orientation improve firms’ cooperation in international scenarios? Sustainability, 11(24), 6936. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11246936

- Griffin, J. J., & Prakash, A. (2014). Corporate responsibility initiatives and mechanisms. Business & Society, 53(4), 465–482. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650313478975

- Gupta, A.,Singh, S., &Khan, M. (2023). Multilateral alliances and global cooperation: Case studies in collective decision-making. Global Governance Perspectives, 15(4), 210–225.

- Hickman, E. (2014). Boardroom gender diversity: A behavioural economics analysis. Journal of Corporate Law Studies, 14(2), 385–418. https://doi.org/10.5235/14735970.14.2.385

- Hilson, G. (2012). Corporate Social Responsibility in the extractive industries: Experiences from developing countries. Resources Policy, 37(2), 131–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2012.01.002

- Idowu, S. O., Capaldi, N., Fifka, M., Zu, L., & Schmidpeter, R. (2014). Dictionary of corporate social responsibility. Springer.

- Islam, M. T. (2015). Social audit for raising CSR performance of banking corporations in Bangladesh. In Social audit regulation (pp. 107–130). Springer.

- Jamali, D. R., El Dirani, A. M., & Harwood, I. A. (2015). Exploring human resource management roles in corporate social responsibility: the CSR-HRM co-creation model. Business Ethics: A European Review, 24(2), 125–143. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12085

- Jameson, S. (2023). Agile methodologies: Promoting collaboration and adaptability in cross-functional teams. Organizational Dynamics, 18(4), 235–248.

- Johnson, A.,Williams, B., &Garcia, C. (2019). Customer Relationship Management (CRM) systems: Personalizing interactions for enhanced retention. Marketing Innovations Quarterly, 8(2), 45–58.

- Johnson, M. P., & Schaltegger, S. (2015). Two decades of sustainability management tools for SMEs: how far have we come? Journal of Small Business Management, 54(2), 481–505. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12154

- Kaplan, R. (2015). Who has been regulating whom, business or society? The mid-20th-century institutionalization of ‘corporate responsibility’in the USA. Socio-Economic Review, 13(1), 125–155. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwu031

- Kim, D.-Y., Kumar, V., & Kumar, U. (2012). Relationship between quality management practices and innovation. Journal of Operations Management, 30(4), 295–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2012.02.003

- Klettner, A., Clarke, T., & Boersma, M. (2014). Strategic and regulatory approaches to increasing women in leadership: multilevel targets and mandatory quotas as levers for cultural change. Journal of Business Ethics, 133(3), 395–419. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2069-z

- Kolk, A., & Van Tulder, R. (2004). Ethics in international business: Multinational approaches to child labor. Journal of World Business, 39(1), 49–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2003.08.014

- Kramar, R. (2014). Beyond strategic human resource management: is sustainable human resource management the next approach? The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(8), 1069–1089. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.816863

- Lee, H. (2024). Unilateral sanctions: Their use and effects on international relations. Diplomatic Studies Quarterly, 28(1), 45–58.

- Lee, K. H. (2011). Integrating carbon footprint into supply chain management: the case of Hyundai Motor Company (HMC) in the automobile industry. Journal of Cleaner Production, 19(11), 1216–1223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2011.03.010

- Li, X., Abbas, J., Dongling, W., Baig, N. U. A., & Zhang, R. (2022). From cultural tourism to social entrepreneurship: Role of social value creation for environmental sustainability. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 925768. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.925768

- Lim, E., & Varottil, U. (2022). Climate risk: enforcement of corporate and securities law in common law Asia. Journal of Corporate Law Studies, 22(1), 391–430. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735970.2022.2093833