Abstract

Zakat can be allocated to help the poor establish a sustainable income. Recipients may receive zakat assistance in the form of both capital and job equipment, coupled with suitable training. Traditionally, zakat distribution has adhered to classical principles, involving monthly financial aid or limited working capital. However, this method is perceived as less effective in eradicating poverty. This study emphasises the significance of directing zakat towards income generation as a more impactful approach to poverty alleviation. To this end, this study explores classical and modern models of zakat disbursements for income generation, drawing from scholars’ perspectives in their respective eras. A qualitative approach for data collection and analysis was adopted based on the evidence from classical and modern literature. There are several methods of zakat disbursement for income generation, namely capital grants, loans, and training. Based on a survey of classical and modern literature, it was found that some classical scholars have granted such disbursements. Recognising the efficacy of this approach in helping zakat recipients, modern scholars are inclined to support income generation programs, including zakat loan provision. The evolution of this concept, coupled with its successful implementation, positions zakat as a key player in eradicating poverty among Muslims globally.

Reviewing Editor:

1. Introduction

Zakat, an obligatory charity in Islam, plays an important role in the eradication of poverty. Payments which normally account for 2.5% of total wealth must be given to the categories of people specified in the Quran (Ali et al., Citation2020; Haneef, Citation2008; Mahmud & Haneef, Citation2008). Zakat can be collected from many sources of wealth, such as gold and silver, salaries, farm animals, agricultural produce, and business profits (Al-Qardawi, Citation1999; Sarif et al., Citation2020; Zayas, Citation2003). The eligible groups determined in the Quran are the poor, the destitute, the zakat worker, those who are new to Islam, the debt bondage, those in the cause of God, the borrower, and the traveller (Quran, 9:60). Traditionally, zakat has been distributed in money or in kind, and recipients can spend it to satisfy their urgent needs and relieve them from poverty. New disbursement methods have been introduced for income generation.

Income generation refers to an intervention program offered by the government or charitable bodies to assist poor people in improving their work skills and increasing their income. Muslim academics and scholars have called for the mechanism to be embraced in zakat disbursement, as they perceive that it could lead to better disbursement of the fund (Al-Qardawi, Citation1999; Sarif, Citation2013).

Scholars have suggested that the distribution of zakat for income generation (also known as productive disbursement) is more effective and sustainable than cash disbursement, because it makes recipients independent without constantly relying on zakat (Ayuniyyah et al., Citation2017; Khaliq et al., Citation2023). By contrast, cash disbursements (also known as consumptive disbursements) are only suitable for non-productive recipients, such as disabled and ill persons, to fulfil their basic lives for a specified period. Such disbursements cannot free them permanently from poverty but merely satisfy their basic needs temporarily (Ayuniyyah et al., Citation2017).

The able-bodied poor must also be independent. Hence, the disbursement for income generation is paired with other programs, such as monitoring and training, as discussed later (Talib & Ahmad, Citation2019). Apart from this, some scholars also argue that such a disbursement also can turn the recipients into zakat contributors, if they succeed in the future. This will help institutions collect more zakat in the long run (Talib & Ahmad, Citation2019; Wutsqah, Citation2021).

However, the distribution of funds must follow the rules and regulations of Islamic law. In this case, the disbursement must fulfil some requirements determined by scholars who refer to religious legal sources and employ the process of legal reasoning (ijtihad) to solve and justify a new type of disbursement to meet current demands.

Hence, this study demonstrates the concept of zakat disbursement for income generation and its application models. Referring to the previous literature, although there are writings about zakat distribution for productive purposes, not many have touched on a distribution model that combines material and non-material support. In addition, this article presents the legal justification for the use of zakat for income generation from an Islamic point of view.

This study adopted a qualitative methodology in which data collection mainly involved library research. All collected literature was then analysed using content analysis. In this case, an inductive analysis was employed to create a model of disbursements from various scholars’ views. The findings are presented in the form of disbursement models with relevant justifications. Finally, classical and contemporary models induced from scholars’ perspectives are compared.

The next Section discusses the concept of zakat in terms of income generation. It is then followed by Section 3 that discusses classical fiqh on the disbursement. Section 4 discusses the new ijtihad regarding disbursements, followed by the disbursement model. Section 6 discusses the future prospects of zakat for income generation.

2. Zakat for income generation as a new mechanism of disbursement

Income generation refers to a gain or increase in income. This refers to an intervention program offered by the government or charitable bodies to assist poor people in improving their working skills and increasing their income. Helping agencies provide funding, training, and other related services (Hurley, Citation1990; Ritchie, Citation2006). It has been proposed as a popular strategy for eliminating poverty since the 1970s. It is widely believed that poverty problems could be eliminated through capacity enhancement and income assistance. Capacity enhancements can be offered to those who are productive and capable of working. The opportunities created will help raise their income levels in the long term (Ahmed, Citation2002; Sarif, Citation2013, Restuningsih & Wibowo, Citation2019).

Income generation is a planned program that helps participants earn a better income. The program offers funding in the form of loans and grants. Grants are suitable options which involve substantial amounts–possibly to buy machinery–for which repayment is impossible. This is suitable for those who are susceptible to the risk of a loan (Hurley, Citation1990; Ritchie, Citation2006). Some income generation programs help recipients through loans, and the repayment fund can be utilised to help others. Providing recipient loans may be a better option, as practice can make recipients committed to their responsibilities (Ritchie, Citation2006; Sarif, Citation2013).

Training is another important aspect of income-generation programmes for developing beneficiary skills. There are several types of training, such as apprenticeship and vocational training. Apprenticeship is a method of transmitting job skills to the workplace. Initially, the employer monitors the trainee directly and may intervene if necessary. As the trainee becomes more experienced, the trainer will become more independent (Ferej, Citation1996). In contrast to apprenticeships, vocational training refers to the technical courses offered by vocational institutes that concentrate on high-demand skills in the industry (Grierson & Mc Kenzie, 1996).

Many countries such as Bangladesh, Pakistan, the Philippines, and Indonesia have started income-generation programs for the poor. Since the 1970s several organisations have been founded, such as the Self-Employed Women Association (SEWA), Grameen Bank, and the Aga Khan Rural Support Program. These organisations have been supporting thousands of the poor, especially in rural areas, by offering much aid for the able-bodied poor, such as loans, grants, and training, to improve their talent and skills (Nurzaman & Kurniaeny, Citation2019; Sarif, Citation2013).

Considering this development strategy, many writers and scholars proposed zakat as a funding source for income generation. However, eligible recipients need to be guided strictly on how to spend time wisely and be properly trained to enhance their capability to flourish. This is important, as they tend to spend zakat aid on non-essential goods because of bad habits. Mannan (Citation1989) mentioned that many poor families will spend the given cash aid for something which is not meant for them because of their personal needs. Hence, to solve this problem, he suggests that funds should be given in the form of professional necessities such as tools, fertilisers, or free education and training.

Similarly, Fauzee (Citation2004) reported a case in which zakat funds were dedicated to programs to help recipients run businesses. Unfortunately, the programme has stopped because the funds given have been spent on other things (Md Ramli et al., Citation2011; Fauzee, Citation2004). Such incidents clearly demonstrate the urgency of a more structured and guided approach to the disbursement of zakat funds.

In general, the distribution of zakat for income generation can be considered more strategic than monthly stipends or one-off contributions. As their income increases, recipients tend to give zakat to help others. This mechanism is especially suitable for young recipients and those with a bright future. To prevent them from misusing funds for consumption, they could be aided by an additional monthly allowance. Additionally, they must be closely monitored and properly trained. From this explanation, it appears that production-based zakat distribution programs could empower eligible recipients to achieve better livelihoods, whereas consumption-based programs mainly aim to fill out their basic necessities (Ayuniyyah et al., Citation2017).

While the idea of zakat distribution for income generation has been widely suggested by modern scholars, the development of this concept can be traced back to the early formation of the school of thought, as shown in the following sections. The basic idea in classical literature was later the motivation for modern scholars to suggest a rather comprehensive mechanism which suits current needs.

In short, this study depicts the zakat distribution for income generation in classic and modern models. Compared to previous literature, this study not only explores the mechanism of zakat disbursement for income generation, but also compares the models advocated by classical and modern scholars.

3. Classical Fiqh on Zakat distribution for earning income

The issue of zakat disbursement for income generation has been briefly touched upon by classical jurists, although such a disbursement is yet to be practiced. As for the discussion in this article we can loosely refer ‘classical fiqh’ as opinions which are derived from literatures written by Muslim jurists from earlier school of thought (madhhab) prior to the European colonisation period (Khan, Citation2003). Although it is widely understood that after the fourth century of hijra, the ijtihad activities became comparably slower than before, younger jurists still produced new judgements, although a new school of thought was no longer formed (Hallaq, Citation1984). In this section, we refer to well-known scholars who deal with zakat disbursements in their writings.

The issue of giving zakat to generate income is associated with the main issue of whether zakat funds can be provided to able-bodied people. Many scholars prefer that zakat to not be offered to any person whose income would be sufficient for him and his family or a person capable of work (Al-Nawawi, Citation1980; Al-Shafi’i, Citation2001; al-Baji, 1332H). Prophet says: ‘Alms are unlawful (both) for those materially self-sufficient and for those mentally and physically fit (and able to find work)’ (Al-Tirmidhi, Citation1417H; Al-Nasa’i, Citation2001; Al-Nawawi, Citation1980).

In this respect, Hanafites use the ownership of nisab (minimum amount of wealth that is liable to zakat) to differentiate between the rich and poor. They regard the rich as possessing a nisab value of property over their personal needs; therefore, zakat is payable to them. By contrast, having less than that is considered poor and, hence, eligible to receive zakat. This is consistent with their view of forbidding the same individual to be both a payer and beneficiary at the same time (Ibn Humam, Citation1970; Ibn ‘Abidin, Citation1994; Al-Sarakhshi, Citation1989). Hence, considering Hanafi’s opinion, the poor may receive only a small amount to relieve their temporary necessities. As a large amount of funds is needed to help the poor generate sustainable income, such an opinion may not help realise this.

Although as mentioned above that the majority of classical scholars (including Shafi’is) opine that the rich and able-bodied working persons are not entitled to zakat aid, they are slightly critical in their explanation (Al-Shafi’i, Citation2001). Some, such as al-Shirazi and al-Nawawi, think that those who are temporarily unemployed or do not have a stable income due to loss of business could be helped to recover. Al-Nawawi further explained that a person is only considered rich when they can satisfy all the expenditures of their lifestyle to which they and their family are accustomed. According to him:

A craftsman would be offered an adequate amount to acquire tools and equipment that enable him to work and earn his sustenance. This surely varies according to the time, place and capability of a person. Our colleagues give examples that a vegetables seller might be given five or ten dirhams, while a jeweller might be given ten thousand dirhams (translated)… (Al-Nawawi, Citation1980).

Apart from the issue of eligibility and disbursement limits, ownership (al-tamlik) is another issue that needs to be clarified. Al-Tamlik refers to the shift in ownership of zakat wealth from its initial owner (payer) to beneficiaries (Ibn Nujaym, Citation1993). Usually, the zakat payer surrenders the payment to eligible recipients in person, so that the latter can own the wealth completely. Subsequently, beneficiaries can spend what they obtained without restrictions. This can be understood from the word ‘ita’’ (Arabic word means ‘give’) as mentioned in the Quran in verses (2:43) and (2:110).

The issue of ownership transfer could also be understood from the use of ‘lam al-tamlik’ (the Arabic word pronounced as ‘li’ which means ‘for’) in verse (9:60). The word in the verse is considered a preposition to denote the transfer of rights from initial owner to the eight designated beneficiaries of zakat (Al-Buhuti, Citation1997; Al-Kasani, Citation1986; Ibn ‘Abidin, Citation1994). In this regard, Hanafi scholars believe that full ownership is a pillar (rukn) to ensure the validity of zakat payments, which must always be conferred on all designated recipients (Al-Kasani, Citation1986). Hence, the following conditions must be completely fulfilled: (a) full entitlement must be awarded to the recipients without any restriction of spending (b) the fund can only be distributed in tangible form, as Hanafis do not recognise intangible assets or benefits as wealth. Hence, giving intangible wealth, such as offering the right to stay in a property for free cannot be considered as zakat payment (c) The beneficiaries must be sensible (‘aqil) and have capability to keep the wealth (ahl al-tamalluk) (d) The payer (previous wealth owner) cannot interfere in the fund spending. Therefore, a father cannot pay zakat to his children because the former normally determines where to spend the money (Al-Kasani, Citation1986; Ibn Abidin, 1994).

Although some jurists, especially Hanafites, strongly hold the concept of al-tamlik, they do not completely reject the idea of spending zakat funds for income generation. Nevertheless, as they set the distribution limit to the amount of nisab, the distributed sum of zakat may not be sufficient for recipients for a long period of time. On the other hand, Shafi’ ites are very supportive towards this kind of disbursement. They do not specify any maximum amount that can be given to an individual which clearly allows the zakat body to distribute funds as they wish for the benefit of the poor.

Therefore, it is clear that during this era, classical jurists merely question the distribution of able-bodied persons and related issues. Their focus was perhaps only on ensuring that the disbursement of zakat must be made swiftly to avoid any misuse in the process. Hence, the objective of zakat at the time was to immediately relieve recipients who were in dire need. Although there is merely a brief discussion on the distribution of income generation, the idea remains widely referred to by modern scholars. In this regard, classical scholars are considered mujtahid (authoritative interpreters of religious law), and have become the main references for modern scholars seeking new solutions to modern cases.

4. The realization of Zakat disbursement for income generation through new Ijtihad

After the Muslim empires ended, and Western influence deeply penetrated the entire Muslim world, there was a need for new solutions to many emerging modern problems (al-’Alwani, Citation1991; Khan, Citation2003). Khan (Citation2003) argued that at this stage, the legal methods of classical fiqh are being reformulated to reflect contemporary realities. Furthermore, unlike classical jurists, who generally make decisions individually, modern scholars normally make decisions collectively through the institutional structure of ijtihad (Khan, Citation2003).

There are two types of ijtihad: selective and creative. Selective ijtihad involves choosing one of the classical opinions that provides sound judgement after drawing an analogy between different examples of textual evidence. Eventually, modern jurists choose the most conclusive evidence after considering the need to issue practical rulings. Creative ijtihad is employed in most situations related to completely new issues (Al-Qardawi, Citation1996). In the process of finding answers to new issues, the Quran and hadiths, as the main religious sources, should be understood using specific methods. The ijtihad is a constant process that considers all the needs of the contemporary world and should not be tightly bound by traditional understanding (Albayrak, Citation2022).

Modern scholars have expressed their views on zakat allocation for income generation as follows:

4.1. Capital grant

One of the important aspects of the realisation of zakat aid for income generation is the technique of distributing funds. Scholars suggest that zakat can be given to recipients (income-generating participants) as a grant or, alternately, as a loan. The decision is up to the amil (zakat workers), as they really understand the needs of the recipients (Al-Qardawi, Citation1999).

There is no objection from any scholar to disburse the zakat fund for grant provision. This affirmative view of classical scholars, especially Shafiites, has resulted in modern scholars to be more accepting towards the idea of using zakat for income generation. For example, the Indonesian Council of Muslim Scholars decided to use zakat in 1982 for productive purposes. They agree to give zakat to the poor as business capital or essentials for farming activities, as they referred to their opinion of classical jurists such as al-Nawawi and al-Bayjuri, who, as mentioned before, suggested a similar approach (Majelis Ulama Indonesia, Citation2021). Later, in 1989, Nahdatul Ulama (one of Indonesia’s largest Islamic organisations) approved a similar rule. Brief interviews with several ‘ulama in the country were also held by an academician in 1999, regarding the zakat disbursement practice in Aceh. All respondents agreed that zakat could be disbursed for income generation when all basic consumption needs were completely satisfied (Wahid, Citation1999).

Islamic rulings regarding the use of zakat for income generation were first announced in Malaysia in 1994. Selangor, one of the most developed states with the highest zakat collection in the country, stipulates that zakat can be distributed as business capital or to buy necessary tools to help poor farmers or fishermen (Jabatan Mufti Negeri Selangor, Citation1994). Looking at the current distribution, capital grants have been actively offered in many other states, such as the Federal Territory, Kedah, Negeri Sembilan, and Penang. Understandably, such a grant was offered only after religious approval was granted by each state’s religious council (Ismail et al., Citation2021).

4.2. Loan

Scholars disagree on the issue of lending zakat to generate income. Al-Qardawi (Citation1999) argues that zakat can be lent to a recipient because a debtor is one of the groups eligible for zakat. He says that providing zakat as a loan will not merely relieve the recipients from poverty but can also help eliminate riba (interest) (widely practiced in bank loan systems), as the repayment amount will not be compounded. The elimination of interest is one of the main goals of Islamic economics and the broader role of zakat (Al-Qardawi, Citation1999).

Didin Hafidhuddin, an Indonesian scholar and former President of National Zakat Bodies of Indonesia (2004–2015) says that the zakat funds should be given to as many recipients as possible. If the collected zakat amount is small, it could be lent to eligible recipients so that more people can benefit from the fund compared to a non-repayable distribution. He added that the shift in ownership (al-tamlik) in this case was still achieved, as the fund was rightfully owned by them and no longer belonged to the zakat payer. However, wealth is not owned by a specific individual but belongs to many beneficiaries in the collective (Hafidhuddin, Citation2003).

Eventually, Indonesian Ulama Council (Majelis Ulama Indonesia) in 2021 produced a fatwa that approved the use of zakat funds for al-Qard al-Hasan (interest-free loans) for the broader benefit of the recipients (kemaslahatan yang lebih luas). This decision clearly sanctified zakat institutions in the country to offer such a mechanism. Approval is also obtained from certain provisions.

The zakat funds must only be surrendered to the eligible recipients (mustahik),

The funds received by recipients must be used for income generation (usaha).

The amil must be selective in distributing zakat funds,

The recipients must make repayment according to the sum received,

If recipients are unable to repay, a postponement may be granted (Majelis Ulama Indonesia, Citation2021).

Although the initiative is still not widely practiced in Malaysia, several states have issued rulings. Terengganu, in the mid-2000s, conditionally approved the initiative by stating that any annual leftover from Zakat funds could be used for any project that benefited the eligible group of recipients, including investments for their development. The brief fatwa could be understood as the initiative of funding the poor to run a business as one of many forms of investment (Jabatan Kemajuan Islam Malaysia [JAKIM], 2021a; Wan Ahmad, Citation2022).

Another fatwa (religious ruling), produced in Melaka in 2011, stipulated that zakat disbursement to help poor entrepreneurs is permissible in Shariah. According to fatwa, funds must be surrendered without repayment. The fatwa further argued that poor people had the right to receive funds. If the zakat institution still preferred to lend zakat aid to the entitled recipients (perhaps as an additional sum on top of what was provided earlier), the fatwa recommended that the loan be granted from the debtor’s (al-gharimin) portion (JAKIM, Citation2021b).

It appears that the Religious Authority of Melaka and its Mufti (Islamic Jurist of the state) have approved the use of zakat for loans, provided that the money is not from the poor, but from the debtors. This indicates that authority in the states still refers to the rulings that al-tamlik must fulfil in the case of disbursements for the poor. In contrast, Penang, another state in Malaysia, clearly rejects the initiative, as the zakat must be surrendered completely to the recipients without any condition that the money be repaid (Jabatan Mufti Negeri Pulau Pinang, Citation2020). However, other states have remained silent on this issue.

Although treating zakat as a loan is not unanimously accepted by scholars, many organisations have offered such loans because of the limited funds collected amidst the larger amount of poor eligibility for zakat. For example, the National Zakat Bodies of Indonesia (BAZNAS) introduced the Baitul Qiradh BAZNAS which has given recipients benevolent loans (qard al-hasan) since 2010. Each participant is given between Rp 2,000,000 (USD 127.91) and Rp 7,000,000 (USD 447.68) worth of loans to help them do business. It has also been reported that 40% manage to make repayments (Nurcahaya et al., Citation2019). Other private zakat bodies such as Dompet Dhuafa also offer zakat as a form of microfinancing based on loans to the poor. Similarly, Baitul Mal Aceh distributes zakat funds for working capital based on profit- and loss-sharing agreements (mudharabah). Kuwait has also used Zakat funds for microfinance. For example, the Kuwait Zakat House reported that zakat was given as a benevolent loan to the poor and students (Ali, Citation2022). Although disbursements are not widely implemented in Muslim countries, such an initiative may be emulated by other countries, especially where the collection is unsatisfactory and the number of recipients is high.

In sum, many scholars agree that zakat can be utilised as a loan to help the poor. They viewed this from the perspective of better disbursements amid limited funding. Scholars from Indonesia, for example, are more positive about such disbursements, since zakat collection in Indonesia is still low despite the huge number of needy people. In addition, the fact that they are predominantly Shafiites may also contribute to their affirmative opinion, as madhhab may be lenient towards disbursements.

4.3 Training

As mentioned earlier, training is an important aspect in elevating recipients’ skills. In this case, training and related courses can be offered using a zakat aid (Hassan, Citation1986; Siddiqi, Citation1986). However, Obaidullah (Citation2008a) believed that training should be provided when the basic consumption needs of recipients have been fulfilled.

The probability of poor spending on zakat aid for non-intended reasons can be minimised if they have sufficient skills. According to Ahmed (Citation2002), this tendency is stronger when the recipient does not have the necessary skills to run a business. For example, potential recipients may request zakat aid from small cottage industries, such as basket weaving or sewing clothes. Nevertheless, if they do not understand how to weave, funds will almost certainly be diverted to others.

Providing training to zakat recipients is something that jurists do not have a consensus on. Classical scholars do not discuss this as such an initiative; understandably, it remains unknown. However, it can be expected that such a provision will not be accepted by Hanafi scholars because it is considered an intangible disbursement.

In contrast, contemporary scholars believe that intangible disbursements to the poor are also permissible. Many scholars have suggested that Zakat funds can be used to pay training fees to improve recipient skills. In Malaysia, there is clear permission from the Selangor Mufti to spend. According to the fatwa it is permissible for the zakat body in the state to offer courses or training to develop recipients’ knowledge and skills. The fatwa refers to a hadith narrating that the prophet used to give consent to a group of people to milk a herd of camels offered as zakat (without physically owning them) (Al-Bukhari, Citation2021). The hadith indicates that the intangible wealth of zakat is permissible (Jabatan Mufti Negeri Selangor, Citation2008).

The fatwa also stated that zakat must be disbursed for the public interest (maslaha). As for the best way to preserve the interests of beneficiaries, Zakat bodies are allowed to determine how funds must be allocated (Jabatan Mufti Negeri Selangor, Citation2008). Apart from Selangor, Melaka also supports the use of zakat for training and technical courses for zakat recipients (JAKIM, Citation2021b). As is evident from the above discussion, modern scholars have accepted intangible disbursements, incomplete ownership, and the unsettled issues debated by their predecessors. Consent inspires zakat bodies to creatively improve their disbursement system to enhance zakat effectiveness.

Unlike other countries, in Pakistan, the opinion that the al-tamlik principle must be completely fulfilled is still strongly held by local scholars (Khan, Citation1993). Taqi Uthmani, a prominent scholar (who was a Federal Shariah Court Judge and Shari’a Appellate Bench of the Supreme Court of Pakistan), has strongly adhered to this principle. Although he allowed productive distribution for recipients, this must be done without neglecting this principle (Organisation of Islamic Cooperation [OIC], 1987).

To solve this issue, there are suggestions that zakat may work in partnership with other organisations, such as micro-financial institutes, which frequently organise this kind of program. For example, Ahmed (Citation2002) and Obaidullah (Citation2008b) recommend that zakat should complement the efforts of microfinancial institutions or technical colleges. In this case, zakat can be spent to help beneficiaries fulfil the participants’ needs by supplying food, clothing, and daily allowances to them, while the colleges will provide them with essential training. By providing training and mentoring, the chances of the poor becoming successful entrepreneurs will increase (Setiawan et al., Citation2018).

In general, training for income generation has yet to be discussed seriously. This is likely because training is an integral part of education. According to most scholars, providing education to zakat recipients is permissible. Zakat must be provided to needy students so that they can focus on learning. Some scholars consider pursuing education to be part of the act of fi sabilillah (the cause of God) (Al-Qardawi, Citation1999; Majelis Ulama Indonesia, Citation2021). The initiative is similar to providing scholarships or educational assistance to schools or university students.

Perhaps this question pertains to the implementation method. The training participants must be those who need to improve their skills. Only those qualified and capable of learning should receive training. For those in business, training in advancements such as management and marketing can be provided. In this case, if zakat money is not adequate, training can be obtained from government training institutions that can cooperate with zakat management, as suggested by some scholars.

5. Model of zakat distribution for income generation: a more sustainable mechanism

From the classical opinions discussed earlier, the use of zakat funds to help the poor become more productive is permissible. Scholars in their discussions only suggested that recipients should be given money or other tangible assets, such as fishing nets or business capital. At this juncture, opinions on how much a person is allowed to receive from zakat funds vary. Scholars from Hanafi school of law are of the opinion that they can only receive an amount of less than nisab while majority jurists from other sects especially Shafi’is, suggest that there is no such a limit.

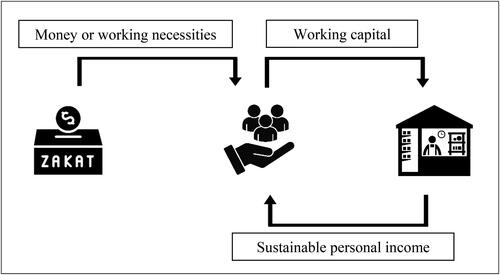

Looking at their overall opinions, there is no objection from any classical jurist to zakat being used to fund income-generation programs. The only issue is that some scholars allow only a small sum of money to be spent on such purposes. Should this stricter ruling be followed by zakat, it may only be suitable for temporary relief, such as helping small traders regain the strength to continue doing business after suffering a loss. At this stage, there is no suggestion that the recipients should be trained to equip themselves with certain knowledge or skills to help them flourish. illustrates the classical disbursement model for income generation ().

Based on the entire process of zakat disbursement, classical scholars understand that the idea of helping the able-bodied poor is to enable them to earn adequate income. Zakat workers can give them capital or any necessary tools relevant to their vocations that they can use to earn a living. According to some scholars, recipients are entitled to a sum that ensures their sufficiency according to their professions and based on their needs (Al-Nawawi, Citation1980).

In this case, the classical model shows that zakat workers need to promptly disburse aid to recipients according to their needs. They believe that aid from zakat should enable recipients to reach a state of sufficiency (kifayah). At this stage, the question of the effectiveness of zakat disbursements has yet to be addressed. Hence, classical scholars have yet to discuss the possibility of zakat workers being actively involved in recipients’ affairs by utilising the distributed fund.

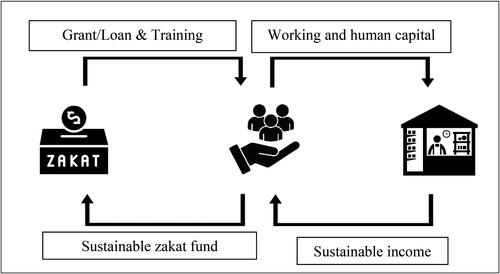

Referring to the modern literature, contemporary Muslim scholars have developed the idea further, suggesting that zakat spending for the poor should include training services. They referred to other popular income-generation programs and suggested that Zakat should be used to support similar initiatives. Some suggest that zakat must join other institutions, such as training or financial institutions, if funds are insufficient.

Another creative strategy proposed by modern scholars is the use of Zakat for loans. As zakat funds are limited, and recipients continue to increase over time, lending zakat money is a strategic move to ensure that the repayment amount can be lent to other eligible recipients. Such a strategy is perhaps suitable in the current situation where income generation programs need a bigger zakat allocation compared to other disbursements, such as food aid or monthly stipends to non-productive recipients. Giving aid in the form of loans could also strengthen the personal discipline of recipients, as they need to fulfil their monthly payment commitment.

Modern scholars also suggest that zakat institutions play more active roles in fund disbursement than the classical model. The recipients need to be guided and monitored closely so that they will manage to utilize the received aid effectively. The recipients can be given proper training so that they can become experts in the area they are working in, and eventually earn a better income. If the recipients are given the fund in the form of loan, they need to make repayment should they are able to do so. Now, zakat institutions do not merely disburse funds but are also responsible for their effectiveness after disbursement. Eventually, it is hoped that the zakat fund will be maintained and utilised by as many recipients as possible. To ensure that all of these initiatives can be executed, modern scholars, as mentioned earlier, are more affirmative than their predecessors. Looking at the overall process of modern income generation through zakat (), the aim of the initiative is not merely to achieve sustainable personal income but also to achieve sustainable zakat funds.

6. Future perspective of Zakat to the global sustainable economics and income generation

As discussed previously, zakat is a monetary religious duty which potentially helps reduce poverty and improve income equality. Studies have shown that zakat has increased poor income and reduced income inequality in many countries such as Pakistan (M. Akram & Afzal, Citation2014), Malaysia (Suprayitno et al., Citation2013) and Indonesia (Latief & Niu, Citation2020). Debnath et al. (Citation2013) reveal that zakat is a better alternative to microcredit programs for eradicating poverty in Bangladesh. The study noted that zakat recipients, compared to other microcredit participants, earned a better income and managed to spend more on necessities.

Zakat has also been reported to have a positive impact on the livelihoods of people in Sri Lanka, a country where Muslims are a minority. It helps people gain better access to basic needs and generate better income (Salithamby et al., Citation2022). In Indonesia, zakat has served as a tool to help poor people change their lives. Through several empowerment programs and business aid, the fund enables recipients to grow and flourish (Ismail et al., Citation2022; Mahomed, Citation2022; Mawardi et al., Citation2022; Widiastuti et al., Citation2021).

Therefore, the income-generation strategy is consistent with the aim of sustainability. Sustainability is associated with progress in satisfying current needs without jeopardising future generations. It is clearly expressed in the meaning of sustainability which is a multidimensional development activity that enhances the quality of life. In this context, economic, social, and environmental protection are interdependent, and mutually reinforcing components should be achieved (Kuhlman & Farrington, Citation2010).

In economic and social contexts, income generation through zakat has the potential to improve the economic well-being of the community. There is also evidence that its implementation enables recipients to earn a better income. As they manage to lift themselves out of poverty, zakat aid is no longer needed, resulting in funds not being depleted quickly. Furthermore, if zakat is offered as a loan, the repayment sum is used to help other recipients. Hence, funds eventually become more sustainable.

Training for income generation will also help improve people’s well-being. As trainees become more creative and innovative, they can explore new businesses and serve their customers better. Training also encourages trainees to share resources such as knowledge, experience, and capital. Such a sharing resource mechanism may enable society to better protect its environment and, hence, could be environmentally sustainable.

In summary, income generation through zakat will enhance the capabilities of recipients, minimise inequalities, and eventually generate more sustainable communities. To improve its implementation, Zakat can cooperate with other institutions such as waqaf (endowments) or other sources of donation funds. Furthermore, funds may not merely be confined to local sources but can also be obtained internationally.

7. Conclusion

In conclusion, income generation is a mechanism that helps the poor to be productive and have a sustainable income. Aid includes the provision of support which normally consists of capital grants, loans, and training.

Although some articles have discussed the practice of zakat disbursement for productive purposes, the emergence of this idea and its development, as well as its related issues, have never been addressed. Hence, this is the focus of the present study.

This article has presented discussions of classical and contemporary scholars on the use of zakat to help the poor become more productive. The majority of classical scholars agree that zakat can be used to help the able-bodied poor perform their vocations. At this stage, the idea is still limited to simple tangible aid, such as giving eligible recipients little capital to start a business, or providing fishing nets for fishermen.

Current scholars, however, are clearly aware that income generation programs can help zakat recipients. Hence, they suggest that zakat could be used to fund capital grants and provide specific training. Another creative invention at this stage is the introduction of loans to generate income. Modern scholars have come up with new justifications to enable zakat funds to be lent to the eligible poor. They used their ijtihad to solve the current problem, especially with the reality of limited zakat funds amid the increasing number of recipients. Their aim is to ensure the sustainability of the zakat fund, while simultaneously helping recipients sustain themselves.

As we found in the discussion, zakat can be disbursed in both tangible and intangible forms. Indeed, many other initiatives besides income generation could be introduced in the future to strengthen the distribution of zakat. The current implementation of income generation through zakat also needs to be assessed so that any weaknesses can be identified and rectified. All of these are important measures to ensure that the disbursement of zakat is more effective and sustainable.

Acknowledgements

The author(s) thank the Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia and Universiti Malaya for their financial support in conducting this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Suhaili Sarif

Suhaili Sarif is currently a Senior Lecturer at the Department of Shariah and Management, Academy of Islamic Studies Universiti Malaya. He obtained his Bachelor Degree in Shariah (BSh) in 1999 and Master in Business Administration (MBA) in 2002 both from Universiti Malaya. He then received his PhD in Islamic Studies (2014) from the University of Edinburgh UK. He specializes in Islamic Management, Islamic Wealth Management and Halal Management. He teaches both the undergraduate and postgraduate programmes covering many subjects within his related expertise. He has been researching on many topics related to the areas of Halal Industry, Zakat and poverty eradication, Mosque institution and Islamic Tourism Industry.

Nor Aini Ali

Nor Aini Ali is currently a Senior Lecturer at the Department of Shariah and Economics, Academy of Islamic Studies Universiti Malaya. She obtained her Bachelor Degree in Shariah (BSh) in 1999 from Universiti Malaya and Master in Economics in 2001 from Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. She then received her PhD (2013) from Universiti Malaya. She specializes in Islamic Economics, Zakat and Development Economics. She teaches both the undergraduate and postgraduate programmes covering many subjects within her related expertise. She has been researching on many topics related to the areas of zakat, poverty, Islamic accounting, halal industry and Islamic tourism industry.

Nor ‘Azzah Kamri

Nor ‘Azzah Kamri is currently a Senior Lecturer at the Department of Shariah and Management, Academy of Islamic Studies Universiti Malaya. She obtained her Bachelor Degree in Shariah (BSh) in 1999 and Master in Shariah (MSh) in 2002 both from Universiti Malaya. She then received her PhD in Islamic Development Management (2008) from Universiti Sains Malaysia. She specializes in Islamic management, Islamic ethics, Islamic wealth management and Halal management. She teaches both the undergraduate and postgraduate programmes covering many subjects within her related expertise. She has been researching on many topics related to the areas of Islamic ethics, Halal industry, Islamic tourism and zakat management.

References

- Ahmed, H. (2002). Financing microenterprises: An analytical study of Islamic microfinance institutions. Islamic Economic Studies, 4(2), 1–13.

- Al-’Alwani, T. J. (1991). Taqlid and Ijtihad. The American Journal of Islamic Social Sciences, 8(1), 129–142.

- Al-Baji, S. I. K. (1332H). Kitab al-Muntaqa Sharh Muwatta (Vol. 2). Matba’ah al-Sa’ada.

- Al-Buhuti, M. I. Y. I. I. (1997). Kashaf al-Qina’ ‘an Matni al-Iqna’ (Vol. 2). ‘Alim al-Kutub.

- Al-Bukhari. (2021). Sahih Bukhari. Retrieved March 21, 2021, from http://www.usc.edu/schools/college/crcc/engagement/resources/texts/muslim/hadith/bukhari/024.sbt.html

- Albayrak, I. (2022). Modernity, its impact on Muslim world and general characteristics of 19–20th-century revivalist–reformists’ re-reading of the Qur’an. Religions, 13(5), 424. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13050424

- Ali, M. M. (2022). Qard-Based Zakat financing: A Fiqhi analysis. Islamic and Civilization Renewal Journal, 13(1), 153–156. https://doi.org/10.52282/icr.v13i1.913

- Ali, N. A., Sarif, S., Mohd Balwi, M. A. W. F., & Kamri, N. A. (2020). Assessment of zakat: A case study of selected Islamic banks in Malaysia. International Journal of Economics, Management and Accounting, 28(2), 431–456.

- Al-Kasani, ‘A-D A. B. I. M. (1986). Bada’i Sana’i fi Tartib al-Shara’i (Vol. 2). Dar al-Kutub al-’Ilmiyya.

- Al-Nasa’i, A. A-R. A. I. S. (2001). Kitab al-Sunan al-Kubra (Vol. 3). Muassasa al-Risala.

- Al-Nawawi, A. Z. M. A-D. (1980). Kitab al-Majmu (Vol. 6). Maktaba al-Irshad.

- Al-Qardawi, Y. (1996). al-Ijtihad fi Shari’at al-Islam. Dar al-Qalam.

- Al-Qardawi, Y. (1999). Fiqh az-Zakah. Translated by Monzer Kahf. Dar-al-Taqwa.

- Al-Shafi’i, M. I. I. (2001). Kitab al-Umm (Vol. 3). Dar al-Wafa’ li al-Taba’ah wa al-Nahsr wa al-Tawzi’.

- Al-Tirmidhi, M. I. I. S. (1417H). Sunan al-Tirmidhi. Maktaba al-Ma’arif li al-Nashr wa- al-Tawzi’.

- Al-Sarakhshi, S. A.-D. (1989) al-Mabsut (Vol. 3). Dar al-Ma’rifa.

- Ayuniyyah, Q., Pramanik, A. H., Md. Saad, N., & Ariffin, M. I. (2017). The comparison between consumption and production-based Zakat distribution programs for poverty alleviation and income inequality reduction. International Journal of Zakat, 2(2), 11–28. https://doi.org/10.37706/ijaz.v2i2.22

- Debnath, S. C., Islam, M. T., & Mahmud, K. T. (2013). The Potential of Zakat Scheme as an Alternative of Microcredit to Alleviate Poverty in Bangladesh [Paper presentation]. 9th International Conference on Islamic Economics and Finance, QFIS, Doha, Qatar, 9–11 September.

- Fauzee, A. A. (2004). Aplikasi Pengurusan Sumber Aset: Analisis Terhadap Harta Zakat di Negeri Perak [Master dissertation]. Universiti Malaya.

- Ferej, A. K. (1996). The use of traditional apprenticeships in training for self-employment by vocational training institutions in Kenya. In J. P. Grierson & M. Iain (Eds.), Training for self-employment through vocational training institutions (pp. 99–108). International Labour Office.

- Grierson, J. P., & McKenzie, I. (1996). Introduction. In J. P. Grierson & M. Iain (Eds.), Training for self-employment through vocational training institutions (pp. 11–18). International Labour Office.

- Hafidhuddin, D. (2003). Islam Aplikatif. Gema Insani.

- Hallaq, W. B. (1984). Was the gate of Ijtihad closed? International Journal of Middle East Studies, 16(1), 3–41. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020743800027598

- Haneef, S. S. S. (2008). Issues in Fiqh Az-Zakah: Implications for Islamic banking and finance. The Islamic Quarterly, 52(2), 97–129.

- Hassan, Z. (1986). Distributional equity in Islam. In M. Iqbal (Ed.), Distributive justice and need fulfillment in an Islamic economy (pp. 35–62). The Islamic Foundation.

- Hurley, D. (1990). Income generation schemes for the urban poor. Oxfam.

- Ibn ‘Abidin, M. A. (1994). Radd al-Mukhtar ‘Ala al-Durr al-Mukhtar Sharh Tanwir al-Absar (Vol. 3). Dar al-Kutub al-’Ilmiyya.

- Ibn Humam, K. A.- M. A. A. (1970). Sharh Fath al-Qadir (Vol. 2). Maktaba wa Matba’a Mustafa al-Halabi.

- Ibn Nujaym, Z. A.- I. I. (1993). al-Ashbah wa al-Nazair ‘ala Madhhab Abi Hanifa al-Nu’man. Dar al-Kutub al-’Ilmiyya.

- Ismail, Gea, D., Majid, M. S. A., Marliyah, & Handayani, R. (2022). Productive zakat as a financial instrument in economic empowerment in Indonesia: A literature study. International Journal of Economic, Business, Accounting, Agriculture Management and Sharia Administration (IJEBAS), 2(1), 83–92. https://doi.org/10.54443/ijebas.v2i1.122

- Ismail, M., Shariff, S., & Hussin, H. (2021). Pemerkasaan program pembangunan ekonomi usahawan asnaf melalui dana zakat. Journal of Islamic Philanthropy and Social Finance, 3(2), 52–65. https://doi.org/10.24191/JIPSF/v3n22021_52-65

- Jabatan Kemajuan Islam Malaysia (JAKIM). (2021a). Wang Zakat Terkumpul. Retrieved July 31, 2021, from http://e-smaf.islam.gov.my

- Jabatan Kemajuan Islam Malaysia (JAKIM). (2021b). Agihan Zakat MAIM: Isu Skim Bantuan Perkahwinan dan Pinjaman Perniagaan. Retrieved July 31, 2021, from http://e-smaf.islam.gov.my

- Jabatan Mufti Negeri Selangor. (1994). Fatwa Tentang Sistem Agihan Zakat Negeri Selangor. Retrieved July 31, 2021, from https://www.muftiselangor.gov.my

- Jabatan Mufti Negeri Selangor. (2008). Meeting Minute of Fatwa Committee, File no. Mesyuarat Jawatankuasa Fatwa 6/2008.

- Jabatan Mufti Negeri Pulau Pinang. (2020). Fatwa Mengenai Zakat Sebagai Pinjaman. Retrieved July 31, 2021, from https://mufti.penang.gov.my/

- Khaliq, A., Lutfi, M., Muin, R., & Jaya, A. (2023). Use of Zakat for productive purposes in Indonesia. Jurnal Ekonomi Islam, 6(1), 39–44.

- Khan, A. (2003). The reopening of The Islamic Code: The second era of Ijtihad. University of St. Thomas Law Journal, 1(1), 341–385.

- Khan, M. A. (1993). An evaluation of Zakah control systems in Pakistan. Islamic Studies, 32(4), 413–432.

- Kuhlman, T., & Farrington, J. (2010). What is sustainability? Sustainability, 2(11), 3436–3448. https://doi.org/10.3390/su2113436

- Latief, N. F., & Niu, F. A. L. (2020). Utilization of productive Zakat in improving Mustahik economic empowerment (study at BAZNAS of Manado City). International Journal of Accounting & Finance in Asia Pasific, 3(2), 13–25. https://doi.org/10.32535/ijafap.v3i2.761

- M. Akram, M., & Afzal, M. (2014). Dynamic role of Zakat in alleviating poverty: A case study of Pakistan. University Library of Munich.

- Mahmud, M. W., & Haneef, S. S. S. (2008). Debatable issues in Fiqh al-Zakat: A jurisprudential appraisal. Jurnal Fiqh, 5, 117–141. https://doi.org/10.22452/fiqh.vol5no1.6

- Mahomed, Z. (2022). Modelling effective Zakat management for the ‘stans’ of Central Asia and establishing pandemic resilience. In M. K. Hassan, A. Muneeza, & A. M. Sarea (Eds), Towards a post-covid global financial system (pp. 143–159). Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Majelis Ulama Indonesia. (2021). Himpunan Fatwa Zakat Majelis Ulama Indonesia 1976-2021. Retrieved March 21, 2021, from http://www.mui.or.id

- Mannan, M. A. (1989). Effect of Zakah assessment and collection on the distribution of income in contemporary Muslim countries. In I. A. Imtiazi (Eds.), Management of Zakah in modern Muslim society (pp. 29–50). IDB.

- Mawardi, I., Widiastuti, T., Al Mustofa, M. U., & Hakimi, F. (2022). Analyzing the impact of productive zakat on the welfare of zakat recipients. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research, 14(1), 118–140. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIABR-05-2021-0145

- Md Ramli, R., Ahmad, S., Wahid, H., & Harun, F. M. (2011). Understanding Asnaf attitude: Malaysia’s experience in quest for an effective Zakat distribution programme [Paper presentation]. International Zakat Conference, Bogor Agricultural University, 19-21 July 2011.

- Nurcahaya, Yusrialis, Akbarizan, Srimuhayati & Hayani, N. (2019). Al-Qardh Zakat treasure to mustahik and its implementation in Indonesia BAZNAS and PPZ Malaysia. Journal of Fatwa Management and Research, 17(2), 202–220. https://doi.org/10.33102/jfatwa.vol0no0.283

- Nurzaman, M. S., & Kurniaeny, F. K. (2019). Achieving sustainable impact of Zakāh in community development programs. Islamic Economic Studies, 26(2), 95–123. https://doi.org/10.12816/0052996

- Obaidullah, M. (2008a). Introduction to Islamic microfinance. International Institute of Islamic Business and Finance.

- Obaidullah, M. (2008b). Islamic microfinance development: Challenges and initiatives. International Development Bank.

- Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC). (1987). Majalla Majma’ al-Fiqh al-Islami al-Dawr al-Thalitha li Mu’tamar Majma’ al-Fiqh al-Islamiy (Vol. 1, no. 3). Mu’assasa al-Tiba’a wa Saffa wa al-Nashr.

- Restuningsih, W., & Wibowo, S. A. (2019). The effectiveness of productive zakat funds on the development of micro-businesses and the welfare of Zakat recipient (Mustahiq) (a case study at Rumah Zakat, Dompet Dhuafa, and Lazismu in Yogyakarta City). Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research, 102, 139–143.

- Ritchie, A. (2006). Grant for income generation. In Agricultural and rural development notes, issue 20. World Bank.

- Salithamby, A. R., A., Hatta, Z., & Fahrudin, A. (2022). Institutionalized Zakah in addressing well-being problems in non-Muslim Majority Sri Lanka. Journal of King Abdulaziz University: Islamic Economics, 35(2), 42–53.

- Sarif, S., Ali, N. A., & Kamri, N. A. (2020). The advancement of zakat institution in Malaysian post Islamic revivalism era. Journal of Al-Tamaddun, 15(2), 71–79. https://doi.org/10.22452/JAT.vol15no2.6

- Sarif, S. (2013). Income generation through Zakat: The Islamization impact on Malaysian religious institution [PhD thesis]. The University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom.

- Setiawan, D., Mayes, A., & Zuryani, H. (2018). Analysis of the role of productive zakat funds on the development of zakat (mustahik) micro business development in Dumai City (Case study of the Amil Zakat Nasional City of Dumai City). American Journal of Economics, 8(6), 237–243.

- Siddiqi, M. N. (1986). The guarantee of a minimum level of living in an Islamic state. In M. Iqbal (Ed.), Distributive justice and need fulfillment in an Islamic economy (pp. 251–286). The Islamic Foundation.

- Suprayitno, E., Kader, R. A., & Harun, A. (2013). The impact of Zakat on aggregate consumption in Malaysia. Journal of Islamic Economics, Banking and Finance, 9(1), 39–62. https://doi.org/10.12816/0001592

- Talib, A. R., & Ahmad, H. (2019). Effectiveness of TVET training and equipment capital assistance to asnaf groups in increase of income in Pahang. Jurnal Dunia Pengurusan, 1(1), 10–17.

- Wahid, N. A. (1999). Agihan dan Manfaat Zakat Jasa (Gaji, Pelaburan dan Upah Kepakaran) Kajian Kes di Propinsi Aceh [Master dissertation]. National University of Malaysia.

- Wan Ahmad, W. M. (2022). Fatwas on zakat in Malaysia –trends and issues. Journal of Ifta and Islamic Heritage, 1(1), 66–87.

- Widiastuti, T., Auwalin, I., Rani, L. N., & Al Mustofa, M. U. (2021). A mediating effect of business growth on Zakat empowerment program and Mustahiq’s welfare. Cogent Business & Management, 8(1), 1882039. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2021.1882039

- Wutsqah, U. (2021). Productive Zakat for community empowerment: An Indonesian context. Journal of Sharia Economics, 3(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.35896/jse.v3i1.179

- Zayas, F. G. d. (2003). The law and institution of Zakat. The Other Press.