Abstract

This study considers the opportunity creation aspect of SMEs rather than taking a general view of threats posed by crises. Thus, this phenomenological study investigates how and what Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) have learned from previous crisis experiences to create knowledge within SMEs and apply such knowledge to deal with future crisis events. Using the Social Constructivist approach, the researchers investigate the experiential crisis learning behaviour of SMEs. Hence, it purposively selected 19 tourism SMEs to extract information about their crisis learning behaviour through their lived experiences. The real-time data collected during the height of the Covid-19 pandemic will likely prove highly influential and valuable for the study. The findings of the study reveal that SMEs have improved and applied knowledge successfully by adopting several strategic approaches, namely bricolage, financial management, market diversification, proactive posture, and developing solid business with embedded knowledge. These findings prompted the creation of a model of the SME's experiential crisis learning process that could be served as a benchmark.

Introduction

The survival of businesses is vital as they make positive and continuing contributions to the economy. However, businesses often cease their operations or close down permanently due to many reasons causing a significant negative impact on the economy. Among such businesses, SMEs are considered as forming the backbone of any economy (Gupta & Fernandez-Crehuet, Citation2021; Ligthelm, Citation2011; Mazzarol & Reboud, Citation2020; Priyadharsan & Lakshika, Citation2012). Thus survival of SMEs is vital for both developed and developing countries. Among various reasons for a business to fail, organisational crises will determine the life or death of an organisation (Doern, Citation2016; Pearson & Clair, Citation1998). Scholars highlight the higher vulnerability of SMEs to crisis as ‘while large corporations suffer from these disasters, small business owners are often hit twice; as local citizens and as business owners’ (Runyan, Citation2006). Hence, crisis management is important to ensure business survival (Pearson & Clair, Citation1998) which is also true with SMEs (Doern, Citation2016).

Among the various types of businesses, the tourism industry can be identified as one of the major revenue generators that has been impacted by a variety of crises. In Pakistan, the hospitality sector was badly hit during the Covid-19 pandemic, as foreign and domestic tourism fell sharply because of the travel restrictions and lockdowns imposed by the government (Burhan et al., Citation2021). Besides the COVID-19 pandemic has halted tourism due to international travel restrictions, such long-term crises have long-term consequences for the tourism industry (Eichelberger et al., Citation2021). The authors added that the industry has a significant impact as it focuses on short-haul tourism, and there are concerns about mass tourism, primarily due to health requirements. According to Lama and Rai (2021), the majority of small-scale tourism businesses have closed, and many middle and bottom line workforce have changed careers. To survive in such crises, the authors have identified the need for more innovative and novel strategies, such as the use of technology and online sources. However, the need to invest in technology, skilled labor, medical facilities, marketing, and promotion will be a challenge for resource-constrained tourism SMEs. Additionally, given that SMEs play a major role in the tourism sector, even in developed countries, empirical studies have highlighted the importance of examining the crisis susceptibility of the tourism sector (Toubes et al., Citation2021). Similarly, in Sri Lanka, the tourism industry has been highly impacted by various types of crises, such as the tsunami, floods, droughts, civil war, terrorism, pandemic, etc., over the last few decades. As the tourism industry served as the third largest source of foreign exchange earnings in Sri Lanka (Sri Lanka Tourism Development Authority [SLTDA], 2018), the various crises experienced by the country, such as those mentioned above, highly impacted the performance of business entities in the tourism sector, many of which were classified as SMEs (Sardana & Dasanayaka, Citation2013).

Moreover, previous studies have recognised that former crisis experiences positively contribute to effective crisis response and are beneficial for entrepreneurs to learn about crises and respond effectively to them (Doern, Citation2016). Nevertheless, the experiences accumulated by an organisation are the basis for organisational learning (Argote, Citation2011), which could even apply to SME crisis management. Being crisis learning directed towards isomorphic learning and vicarious learning through the experience of stakeholders, it is vital to explore the participatory learning approaches of SMEs through SME crisis learning. According to Haneberg (Citation2021) experiences at the first wave of the Covid-19 positively influenced the learning behavior of SME entrepreneurs which led to effective crises response in similar scenarios such as second wave of the pandemic. Lessons learnt during the first wave of Covid-19 were particularly beneficial, to increase their entrepreneurial resilience for upcoming crises, including the second pandemic wave (Schepers et al., Citation2021). Sharma et al. (Citation2021) discovered that past pandemics influence a country’s response in terms of reactive and proactive strategies. The authors emphasise that, based on previous pandemic experiences, most governments invest in short-term measures such as quarantining and social distancing, which are insufficient responses to pandemics to be more proactive. Furthermore, the authors emphasised the importance of proactive strategies when exposing the effects of governance, healthcare infrastructure and learning from previous pandemics.

Therefore, crisis learning is a promising approach for knowledge creation on crises, and hence, it can serve as an effective strategy for organisational crisis management. However, despite the wide range of crises that Sri Lankan tourism SMEs had to face during the past, they continue to demonstrate high vulnerability to crises.

Considering the importance of tourism SMEs to the Sri Lankan economy, this study focuses on organisational crisis management to investigate to what extent Sri Lankan tourism SMEs have used their former crisis experiences to develop their crisis knowledge. As such, the primary focus of this study is to answer the research question of what do tourism SMEs learn when they go through crises, and how they use their crisis learning experiences when called upon to deal with another crisis? The authors conducted an exploratory study with some selected Sri Lankan tourism SMEs to find answers to these questions. The tourism SMEs were identified according to the definition of the Ministry of Industry and Commerce (Citation2016) as firms in the service sector that had fewer than 200 employees and an annual turnover of less than LKR 750 million.

Literature review

Organisational crisis management and crisis management in SMEs

All organisations are vulnerable to crises (Etemad, Citation2020; Williams et al., Citation2017). Currently, organisational crises have increased in frequency and intensity (Mikušová & Copíkova, 2016). Despite the type of the crisis those characterise with low probability, high impact, threaten the organisational viability and hence need to obtain urgent decisions (Pearson & Clair, Citation1998; Shrivastava, Citation1993). Clearly, crises generate significant adverse effects, including loss of regular income, physical damage to assets and human resources, while making the affected parties highly depressed. Therefore, crisis management became an important task within organisations to effectively confront the challenges that crop up to ensure the long-term survival of the business.

Despite the significant contribution SMEs make to an economy SMEs demonstrate high vulnerability to crises owing to many reasons. Hence, this emphasises the importance of preparing for a variety of crises (Herbane, Citation2006). Previous studies note that SMEs were forced to cease operations temporarily or permanently due to various crises (Asgary et al., Citation2012). Therefore, effective crisis management is an essential requirement for the overall management of SMEs and for the long-term survival of the business.

Earlier empirical studies show that SMEs that possess prior crisis experience are better prepared, respond more effectively, and recover faster from a crisis than businesses without such experience (Asgary et al., Citation2012; Spillan & Hough, Citation2003). Due to a lack of prior crisis experience, SMEs underestimate the threat of emerging problems as they have not previously encountered them (Spillan & Hough, Citation2003). This lack of knowledge prevents them from implementing effective crisis management practices that would allow them to address the problem at an early stage (Pollard & Hotho, Citation2006). Furthermore, they tend to treat such crises passively since they believe they lack the resources to deal with them (Spillan & Hough, Citation2003). However, since SMEs have a limited resource base (Battisti & Deakins, Citation2015; Crick et al., Citation2018; Herbane, Citation2006, Citation2010; Macpherson et al., Citation2015; Parnell, Citation2009), improving existing resources may positively contribute to the survival and even development of SMEs during a crisis. Therefore, crisis learning could be an effective strategic approach to building the existing resources for effective crisis response.

Crisis learning as an effective mechanism for crisis management

The literature on crisis management emphasises the importance of finding a silver lining even in a challenging situation and working on it to create a better future for the organisation (Vargo & Seville, Citation2011; Branicki et al., Citation2017). Guided by this, the authors have emphasised the importance of using strategic approaches to create opportunities in times of crisis, acting imaginatively, and going beyond simply surviving the crisis.

Among the various approaches available for SME crisis management, social coping has been identified as playing a critical role as it has made it possible for SMEs to expand their limited resource base. Learning is a social process that occurs due to interactions between people and their environment (Kim, Citation2005). Learning from failures and/or previous experiences and developing knowledge for effective responses in future is critical for business survival in the long run. Crisis learning has been identified as critical for businesses because it provides opportunities to learn effective crisis management techniques. Although previous research has shown that crisis learning improves response to future crises (AlBattat & MatSom, Citation2014; Macpherson et al., Citation2015), this has not been adequately studied with SMEs.

Existing knowledge in SME crisis management

Crises are vivid, uncontrollable, and have serious and unexpected consequences for the subject. Businesses, particularly, must plan for such contingencies. Despite being more vulnerable to crises than larger organisations, less attention has been paid to SMEs from the crisis perspective (Fasth et al., Citation2021; Herbane, Citation2010). Empirical evidence is available on business failure caused by crises, even with SMEs (Asgary et al., Citation2012; Irvine & Anderson, Citation2005). Among various reasons for SME failure due to crises, limited resources possessed by SMEs were the most notable one (Eggers, Citation2020; Herbane, Citation2006, Citation2010; Parnell, Citation2009). Such resource constraints exercise an indirect effect by limiting access to finance (Hyun, Citation2017) and reducing the tendency for networking (Battisti & Deakins, Citation2015; Crick et al., Citation2018; Macpherson et al., Citation2015) during the crisis phase. Therefore, crisis management is important to ensure the survival of the business. As appropriate crisis response is one of the major requirements for effective crisis management, it should be treated by SMEs as an important factor necessary to ensure their survival.

Furthermore, Doern (Citation2016) stated that previous studies evaluated the entrepreneurs’ experiences in terms of entrepreneurial risk, learning, and business failure but did not pay attention to crisis studies. Recent reviews on SME crisis management have also highlighted the need for more research on how entrepreneurs and small businesses learn from crisis events (Doern et al., Citation2019). As learning begins with experiences (Argote & Miron-Spektor, Citation2011), the study’s findings also revealed that SMEs’ crisis experiences facilitate crisis learning and the creation of embedded knowledge within SMEs. Although the importance of learning for effective crisis response has been identified in the existing SME crisis management literature, it does not give any indication that the SMEs have adopted a proactive posture towards crisis learning.

The literature has further highlighted that during the crisis response stage, rather than considering the short-term recovery, it is necessary to adopt long-term strategic approaches (Branicki et al., Citation2017; Kottika et al., Citation2020; Toubes et al., Citation2021). Amidst such strategic approaches, scholars in the field have emphasised the importance of adopting more innovative approaches through bricolage (Alonso et al., Citation2021; Branicki et al., Citation2017), market diversity (Schepers et al., Citation2021), development of self-efficacy (Branicki et al., Citation2017), possession of a shared vision, and networking (Branicki et al., Citation2017; Doern, Citation2021; Kottika et al., Citation2020; Mikušová & Copíkova, 2016; Toubes et al., Citation2021) for effective crisis management. Although previous studies recognised that prior crisis experiences positively contributed to effective crisis response (Doern, Citation2016), they have not explored sufficiently their effect on crisis learning. More importantly, the networking and social coping strategies were discussed with a focus on resource mobilisation, while there was little discussion of knowledge creation, which is highly relevant for SMEs that must manage with limited resources. Hence, this study investigates the relationship between past experiences and the impact they have on crisis learning.

Furthermore, none of the existing studies has explored in depth the experiential learning aspect of those factors, such as what they learn, how they learn, and how that helps to embed knowledge within SMEs so they may effectively use it for future crisis response. Although some of the studies considered only one type of crisis (e.g. the Covid-19 pandemic) during its first and subsequent waves to understand the learning effect of past experiences and the application of that knowledge to future circumstances (Schepers et al., Citation2021), they did not consider the different types of crisis that SMEs faced over the period. More importantly, the networking and social coping strategies were discussed with the main focus on resource mobilisation, while there was little discussion of knowledge creation, which is highly relevant for SMEs that have to get by with limited resources.

Despite highlighting the high crisis vulnerability of SMEs in developing countries compared to SMEs in developed countries, hardly any research, particularly in-depth research, has been conducted in the developing economies (Asgary et al., Citation2012). More importantly, scholars have identified SMEs in the hospitality sector as being more vulnerable to the effects of unexpected crises (Burhan et al., Citation2021). Consequently, this study focused on the learning behaviour of SMEs, as it contributes to the generation of knowledge that SMEs can use to deal with future crises. Therefore, this study could fill a gap in the literature by identifying a crisis as an opportunity for SMEs to learn (Wang, Citation2008) from their experiences, thereby assisting them to respond more effectively to any future crisis rather than simply identifying it as a threat and leaving it at that.

Theoretical framework

The theoretical framework of the study is constructed by combining several theories to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the SME crisis learning behaviour. Accordingly, the experiential theory and the communities of practice theory aim to evaluate the learning approaches within and across SMEs. Conservation of Resources (CoR) theory (Hobfoll, Citation1989) is adopted to explain the learning behaviour of SMEs when dealing with both real and potential crises threats, while the knowledge creation theory shows how social coping can serve as an organisational resource. Moreover, David Rae’s (Citation2004) Triadic model is applied to understand the different sources available to SMEs for crisis learning and how to incorporate those learning sources to create the SME crisis learning model.

As the theoretical lens of learning is a social process based on experiences (Higgins & Aspinall, Citation2011), this research will adopt an experiential learning approach towards the learning process, which holds that ‘knowledge is created through the transformation of experience’ (Kolb, Citation1984). Thus, learning is the process of adaptation, and the transformation process includes the transaction between the individual and the environment as well as the process of knowledge creation. Therefore, this cyclical process consists of concrete experiences (learners go through new experiences), reflective observations (reflect on their concrete experiences from a different perspective), abstract conceptualisation (create generalisations or principles that integrate their observations into theories and develop informal theories) and active experimentation (where they test what they have learned in other more complex situations and use those theories to make decisions or solve problems). Hence, it is possible to identify here the application of the experiential learning processes of individuals and groups in an organisation in the context of organisational crises.

The incorporation of the Communities of Practice (CoP) Theory (Wenger, Citation1998) enables us to understand the possibility of establishing the social aspect of learning that creates a shared vision within and across organisations. According to the author, it allows groups of people who have a common way of doing things to learn how to do them better through frequent interaction. Hence, this strategic approach of the communities of practice can be utilised by the SMEs for crisis learning to enhance their strategic capabilities at the crisis response phase within and across organisational levels.

Furthermore, because of the stress caused by the crisis, the Conservation of Resources theory (Hobfoll, Citation1989) is used to understand the crisis response behaviour of SMEs through social coping (i.e. through experiential learning). In contrast to other theories, the CoR theory predicts psychological or behavioral action even when people are not exposed to stressors (Hobfoll, Citation1989). For this reason, the study considers the applicability of CoR theory for crisis learning because the emphasis was on using it for knowledge creation via self-experiences and social coping both during and before or after a crisis. Moreover, the study considers the possibility of identifying the crisis knowledge of SMEs as a resource within the organisation.

Finally, the triadic model (Rae, Citation2004, Citation2005) acts as a guide to identify the different sources of entrepreneurial learning by considering the crisis learning of SMEs. It takes into consideration entrepreneurial learning, which involves gaining access to the SMEs’ actions, environment, interactions with others, and narrative accounts of their personal and business ventures. These accounts should describe how individuals (including businesses in this instance), may connect with social context, namely personal and social emergence (learning experience from the families), contextual learning (participation in community, industry and other networks where shared meaning is constructed), and the negotiated enterprise (the interactive process of exchange with others within and around the organisation).

Methodology

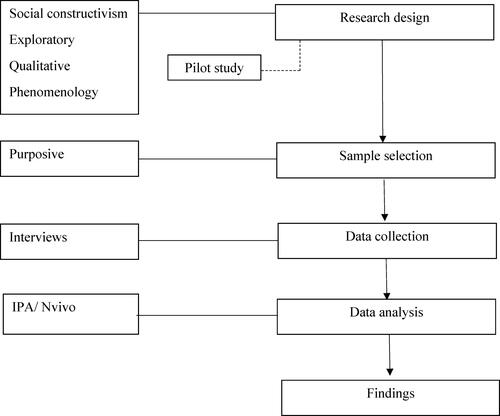

This qualitative study is based on the social constructivism approach, which established the foundation for qualitative research (Ponterotto, Citation2005). Typically, phenomenological studies are based on the social constructivism philosophy and are intended to investigate socially constructed subjects or socially influenced issues (see Bolas et al., Citation2007; Pride, Citation2019; Siddiqi, Citation2021). This phenomenological study aims to investigate the impact of the crisis phenomenon through the lived experiences of several people (Creswell, Citation2007). Despite the difficulty of obtaining data during a crisis, the researchers were able to conduct the study using real-time data, which has been overlooked in most previous studies. Accordingly, summarises the entire process followed by the researchers.

Although Sri Lankan SMEs operate in a variety of industries, this study focuses on those in the tourism industry. The sample consists of 19 tourism SMEs in Sri Lanka’s Southern Province. The tourism industry’s significant contribution and the representation of SMEs in the tourism sector in Sri Lanka compel the inclusion of the industry in the study. The importance of context in a phenomenological study is considered by selecting SMEs in Sri Lanka’s Southern Province, which have turned out to be highly vulnerable to various types of crises over the last few decades. Also, tourism is one of the major industries in which many SMEs located in the southern coastal area of the country are engaged.

This study conducted face-to-face interviews with selected SMEs with an average interview time of approximately one and a half hours for each participant. Adhering to the health guidelines, the second interviews were conducted over the phone to obtain a more holistic understanding of the subject. As a phenomenological study, participants with relevant experiences had to be included (Alase, Citation2017; Smith, Citation2011). Hence, the sample was purposively selected to include only those participants who had relevant crisis experiences. Multiple discussions and close relationships maintained with participants enabled the researcher to identify those who were more relevant to the study. The researcher contacted each respondent in advance to know his/her willingness to participate in the study, agree on a convenient date, time, location, etc. The reduced business volume and fewer customers due to the Covid outbreak allowed more freedom for SME entrepreneurs to participate in discussions, provide real time data, and recount recent experiences. The interviews were conducted at the business premises of the SMEs as it was more convenient for the participants while also allowing the researcher to get more information through direct observation. Given the study’s goal of investigating SMEs’ previous crisis experiences and the creation of knowledge within the business over time, the sample was drawn from SMEs that have been in operation at least since 2010. The respondents in this Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) study were carefully chosen to be homogeneous in terms of business type (tourism), gender (only two females), marital status (all married), level of education (above advanced level except two), and so on. However, the sample’s exclusion criteria could be identified as entrepreneurs who had recently entered the business and those who were unable to communicate in either English or Sinhala. Therefore, the participants were selected those who started their business operations prior to 2010. Hence, those businesses should possess the former crisis experiences that occurred in the country.

The researcher followed the ethical guidelines prescribed for qualitative research. The researcher also obtained the consent of the study participants for the use of data collected for this study. The interviews were audio recorded with the participant’s permission and then transcribed and translated. The data were then analysed following the principles of IPA. The author read and re-read the transcripts several times while listening to the recordings to extract the meaning and implications of the data. Each additional reading offered a new insight on the data, and improved the understanding about important data and made things much clearer. Then the initial noting was then directed to develop immerging themes by writing notes in the margin. The researcher conducted cross-sectional analyses directly to identify the study’s major themes and sub-themes. It continued for searching for connections across emergent themes by abstracting and integrating themes with each new case up to the 19th interview. Finally the data were interpreted to deeper levels through the use of metaphors and temporal references, and by importing other theories as a lens through which to view the analysis. The qualitative data analysis software NVivo was also used to organise the data to improve the process’s transparency. Prior to the main study, a pilot study was conducted to improve the researcher’s skills and experience before conducting a full-scale qualitative study. Interviewing key informants, maintaining a diary, keeping field notes and making observations enhanced the trustworthiness of the research. This allowed the researcher to look at the same phenomenon using different sources (Decrop, Citation1999).

Findings

The ‘opportunity-centric’ perspective is critical if SMEs are to find the silver lining even in a highly challenging environment such as a crisis. One of the most significant benefits that SMEs can gain from crises is the opportunity to learn something useful from them. As there is no additional resource utilisation in the process, such behaviour could address the challenge of SMEs’ resource limitation. Furthermore, this study looks beyond the cognitive learning behaviour of SME entrepreneurs and looks into the organisational learning behaviour of SMEs to create embedded knowledge within the SME. This emphasises that what SMEs learn is highly influenced by how they learn. Due to this, networking has been identified as a key factor through which SMEs can gain a wealth of knowledge from both within and outside of their own business entity. In the light of these findings, it can be said that SMEs’ learning behaviour is shaped by their own experiences as well as the experiences of other stakeholders such as family members, friends, other businesses, and so on. Due to resource constraints, SMEs must effectively manage their existing limited resources. However, networking has the potential to broaden the firm’s resource base to some extent (Eriksson, Citation2014).

As a social process, entrepreneurs can learn from a variety of sources and what they learn is highly interconnected to how they learn. Accordingly, the study has applied David Rae’s (Citation2004) triadic model to interpret the different sources from which SMEs can learn more about crises (Refer to ).

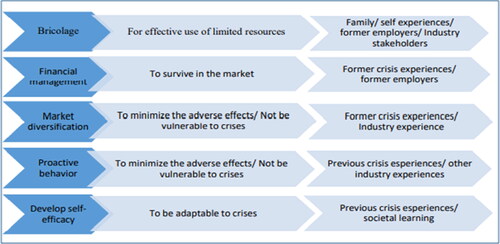

Finally, the IPA found five major themes and ten sub-themes on what SMEs learned from previous crisis experiences and how they used such experiences to create knowledge within their organisation for effective future crisis response. The findings revealed that the SMEs applied their knowledge so they could follow strategic approaches by applying their previous experiential crisis learning in following areas (Refer to ).

Table 1. Major themes and sub themes.

Bricolage

As SMEs are characterised as firms with limited resources, in a crisis situation they will be subject to more resource constraints. Consequently, effective utilisation of existing resources is critical if SMEs are to overcome and survive the crisis (Etemad, Citation2020). Bricolage would be an ideal strategy for SMEs to combine resources at hand to tackle new problems and make use of such opportunities as a ‘muddling-through’ strategy (Branicki et al., Citation2017). Accordingly, this study identified the strategy of bricolage as based on the following aspects:

Dual role of the entrepreneur

The dual role of SME entrepreneurs is reflected by the fact that the operations manager also serves as the risk manager (Khan et al., Citation2020) whereas in the case of women entrepreneurs, they must act as dutiful mothers while being engaged in the business (Surangi, Citation2018). The entrepreneur’s dual role as a business owner and an employee in the firm is advantageous, especially during a crisis. Although entrepreneurs tend to reduce their involvement in day-to-day operations and take on more strategic responsibilities, as the business grows, they may need to take on operational responsibilities during a crisis to keep the operations running smoothly (Schepers et al., Citation2021). Many entrepreneurs stated that previous experience gained from their biological families and early carries on dealing with such situations proved useful later for crisis management when difficult situations arose in their own businesses.

In 1971, when the JVP insurgents started attacking police stations, the government had to bring the situation under control. It did this by imposing a curfew. I was a teenager then, and my mother who was a doctor was running a nursing home. The patients in the hospital had to be fed, so my mother started cooking meals for the patients too at home. We could not go to school, and I had to stay at home. Me and my siblings then became involved in helping her run the hospital. So, at that age it was a big experience because we learned from our parents how to manage a crisis (Saman).

Moreover, to limit their employee costs during crises, SME entrepreneurs practiced the dual role of owner-manager, especially during the period of the Easter attack and Covid-19. Kosala stated that he participates in kitchen activities by helping and assisting as needed and providing customer service. He used his previous experiences gained through industry engagement and applied it later soon after the Easter attack. He even managed to keep nearly half of his total employees working during the Covid pandemic.

Although I was linked closely with the tourism industry and tourists, I could not work as a cook, but I could serve the meals, and I did that often. Even after engaging 12 people to do the work (at the Easter attack), I continued to do my part. That is because when the crowd is coming, I had to help them. I was the Steward. Even then, I would sometimes go to the kitchen, and help the kitchen staff.

Such constructive intervention was made possible by their previous employment and career experiences.

Networking with close-ties and industry stakeholders

In a crisis, the flexibility of family-owned SMEs with family members holding key management positions can prove highly advantageous (Giannacourou et al., Citation2015). Due to the shared knowledge of family members, close friends, and even some employees, particularly the more loyal employees, the social coping approach appears useful for effective crisis response. To deal with the second and third wave of the pandemic, most of the entrepreneurs stated that they simply re-applied the experiences they had gained from the tsunami, the Easter attack, and even the first wave of the Covid pandemic. As mentioned by Prabath,

I learned to cook as well. When the chefs returned after the Easter attack and the Corona pandemic, I did not have any work to do. At times when the chefs were unable to come to work, a friend of mine and I did the cooking. We started working together and catered to the needs of the visitors who came here.

Apart from family experiences and their own experiences, lessons learned at their first job, as well as vocational or professional learning obtained from a variety of institutions, provide entrepreneurs with formative experience that contributes significantly to their overall learning (Rae & Carswell, Citation2001). The findings of this study show that the experiential learning behaviour of SMEs is critically important to the owner-manager. Aside from cognitive learning, it was discovered that SMEs obtain knowledge through vicarious learning, primarily through close relationships with tradespeople. SME entrepreneurs also learned how to manage a crisis effectively through their early career and minor crisis experiences. Persuading existing labor to work long hours and resorting to networking as a social coping strategy were skills that Saman learned early in his career while working for a large organisation.

Most of the meat items stored there had to be salvaged. So, we were instructed to move the meat products to the Beruwala fishery harbour that had a large cool room, which they allowed us to use until we got our cool room fixed. When this happened, I worked for about 16 hours at a stretch. We could not give up. We had to check all the meat and fish and discard whatever was going bad and save the rest. That was like a minor crisis for us, but there again, we watched to see how the chef would manage it. The hotel management planned it well and the operation worked smoothly. The whole thing can be seen as a good example of how to manage a crisis.

Respondents said they shared their experiences and knowledge mostly with family and close friends. It is notable that after the long illness or death of their parents, who were the business owners at the time of the crisis, the offspring would usually inherit the business. When the original entrepreneur happened to perish in the tsunami, the family’s elder son or daughter would usually take over and become the new owner. They would already be actively involved in the business by that point. Sahan described the involvement of his relatives in developing the business after his father’s death.

I sat for the Advance Level examination in 1981. Made only the 1st attempt. Did not make further attempts and simply joined the business. Father’s brother was there to help. He was not married. He and my mother developed the business after that.

His experience while working with his mother and the relatives helped him to manage the business operations by himself after his mother was caught in the tsunami and died. Thereafter he took the responsibility for the business as the Managing Partner and developed the business with his siblings. This is a typical occurrence, as in similar circumstances such as the illness or death of the owner, the children take over the responsibility and continue the business with a few key employees.

I have handed over control of the business to my daughter. I just oversee the general state of affairs now and then (Rasika).

Moreover, the respondents emphasise that SMEs do not restrict their relationships only to their family members but extend it to include their employees.

As for all the knowledge and experience I have accumulated, I am not just keeping it in my head. I have shared this with my family members, and I share it with my employees too (Udara).

According to Schepers et al. (Citation2021), regular communication with employees is vital because besides making them aware of better business practices it also does much to build trust and confidence with them. The authors mentioned that such communication should not be one-way (top to bottom) but should be two-way communication where the top management gets feedback from the employees.

A well-developed relationship with outside actors other than the employees may enable better access not only to physical resources but also to information and emotional resources (Fasth et al., Citation2021). Long-term relationships through networking can provide social support in a crisis (Branicki et al., Citation2017), facilitating the mobilising of resources through networks and it allows SMEs to minimise the damage and protect them from crisis (Doern, Citation2021). More importantly, information sharing may enhance an SME’s knowledge of crisis management, giving it high weightage in the organisational context, thereby enabling the firm to be resilient in the face of crises. Therefore, experiences and opinions gained through networking will play a vital role in the organisational learning process, making up for the reduced opportunities currently available to SMEs for obtaining formal training in the tourism industry (Toubes et al., Citation2021). The potential for SMEs to share experience at the industry level was discussed, and the entrepreneurs emphasised the importance of participatory learning for dealing effectively with the various crises they may face in future. They took this further by emphasising the need for networking if they are to engage successfully in collective bargaining to obtain assistance from support organisations so they may remain resilient during the crisis phase.

We requested and obtained a grace period of 6 to 7 months to repay our loans at the Easter attack. Even during this pandemic, we requested a moratorium on the loan repayments (Madura).

Respondents described how they communicate with other industry members, both formally and informally, and how they exchange information. Formal associations, such as Trade Associations, appear to play an important role in such networking forums. Respondents stated that they collectively bargain to obtain moratoriums and concessions from the support organisations. They practised this even during the recent major crises they had to face, namely the Easter attacks, and the pandemic.

Yes, we get our ideas from a variety of sources. How do we deal with this? When will we get a loan if we apply now? Which bank will give money at the lowest interest rate? (Siril)

Previous empirical studies have noted that interaction with the customer as an external stakeholder is important for organisational learning behavior although the SMEs have demonstrated a diminished tendency for such learning (Xie et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, for SMEs to take important business decisions it is necessary for them to deal with customers who live outside the country’s borders.

Some foreigners want to come here and live. For example, there is an English family here. It has been 2 years now since they settled here. They have now bought a piece of land and are building a villa. They are presently staying in a rented apartment. The family now prefers to live here because the crises in their home country are more severe (Kumara).

Hence, the findings highlighted that networking with the relevant stakeholders within and across the business positively contributes to the development of crisis learning while facilitating the creation of shared knowledge within the organisation.

Financial management

Financial management of a SME can be assessed by studying two aspects, namely cash flow management and cost reduction. Reduction of operating costs, which is also known as ‘blocking’, is identified as a successful strategy that is employed to reduce future expenses and thereby enable the business to continue its operations and survive while experiencing minimal adverse impact (Doern, Citation2021).

Cash flow management

With any type of crisis, organisations will have to deal with financial issues, such as a sudden drop in the market, as this sort of thing is bound to happen during a difficult period (Hossain et al., Citation2022). The market slump that SMEs were experiencing during the pandemic is similar to the previous experiences they faced during earlier crisis situations. Mahesh states that a sudden drop in business income is an unpleasant occurrence in the country and it harms the economy. According to him, the tourism industry gradually recovered after the tsunami, but again other crises hit the industry after it had managed to restore normalcy.

The business evolved gradually after the tsunami and the 1983-2009 war. Then there were the Easter bombings. That was a regrettable occurrence because the year 2018 recorded the highest number of tourists ever. Furthermore, it was the year with the greatest increase in tourist arrivals. But in April of 2019, they were confronted with this calamity.

Respondents identified cost concerns during the crisis as a primary factor they should consider. They realised that borrowing is not an option if there is no guarantee of future earnings, which is required to ensure their ability to repay.

One thing that I learnt is not to borrow. If you borrow money, you are going to be down in the dough. One thing I feel strongly about is that I will not borrow unless I know my cash flow will be strong enough to repay that. We faced a crisis like that when we borrowed during the tsunami period (Saman).

Accordingly, the findings revealed that SMEs used their previous crisis experiences to better manage their business cash flow during a subsequent crisis. However, it is necessary to assess the benefits of obtaining financial assistance since risk aversion may not always be appropriate because it limits SMEs’ ability to expand their resource base. Therefore, the risk of borrowing should be carefully considered after weighing it against the benefits and the feasibility of repaying over time without interruption.

Cost management

During a crisis even the routine expenditure must be controlled because that can assist in keeping the business running at minimal operating cost, allowing it to survive the crisis. Respondents indicated that their experience of cost management during previous employment and lessons learned through industry immersion proved significantly helpful to survive any crisis that arose later. It was normal to run the business with a skeleton staff with only the key employees and removing the temporary workers during a crisis. Regarding this, Nihal made the following observation:

To be honest, this property had 25 staff earlier. Now this entire property is managed by just 11 people. (Nihal).

The staff work in two groups. Pay as they work because if I follow the earlier system, there will be an issue in the future. It may even become the norm in future. Therefore, pay on a daily basis. That means each worker will be working only for about 15 days per month. Therefore, work on such a plan now (Kumara).

Moreover, the entrepreneurs stressed the necessity of reducing other operating costs such as rent, electricity, water, etc. Prabath explained that it was difficult for him to bear the operational costs as he was running the business in premises he had taken on lease. Due to this, he had lost his usual income and therefore decided to move to his own premises where he will not need to pay any rent.

Finally, I started here with the experience I got following the Easter attack. When my business dropped by 50%, I realised that I could not pay the electricity bill, water bill, rent, salary, and all. Then I decided to come here, to my own place. So, I do not have to pay the rent as well, which is a big help. It is due to the experience I got that I was able to continue the business at this level.

The findings buttress the former empirical evidence regarding the importance of managing financial resources, primarily cash flow and liquidity, budgetary control, and financial reserves prudently, during a financial crisis (Pal et al., Citation2014). Moreover, during a crisis, SME entrepreneurs are more inclined to seek short-term recovery approaches (Branicki et al., Citation2017) than long-term approaches. Thus, it follows that reducing the costs of the business, particularly the operating costs, will have a significant impact on the chances of surviving a crisis.

Market diversification

In addition to contending with the off season, when a crisis crops up there is a significant loss in sales and operation in the tourism industry, which will badly affect the regular income. Hence, scholars have stated that entrepreneurs need to consider setting up new and more innovative income sources to remain resilient during the hard times (Schepers et al., Citation2021). When the Covid pandemic was raging in the UK, SMEs were engaged in opportunity seeking strategies rather than engage in defensive tactics against the impact of this crisis (Doern, Citation2021). In this study, all participants considered market diversification as the most important strategy to be followed during a crisis. During sustained crises like Covid-19, SMEs had to survive by engaging temporarily in related businesses or even entirely new lines of business (Liguori & Pittz, Citation2020).

Serving both local and international markets

Although the tourism industry does not offer diverse possibilities, there are opportunities to cater to the domestic market, which can help to lighten the negative effects of the crisis. According to the findings of previous studies, tourism-based SMEs in the domestic market generally had a good potential for survival. However, due to the exceptional severity of the Covid-19 pandemic, they found survival rather challenging during this period. Jane relates her experiences as follows:

Anyway, we cannot depend entirely on tourists alone. To survive in this sector, we need to cater to the locals as well. If we serve only foreigners we will be forced to close during the off season and operate only during the main tourist season. There is no sustainability in that.

Then I brought that chef even during the Covid-19 situation… The restaurant was closed for only about one month and then we re-opened it. We put two big boards in Sinhala at the front, saying that rice, kotthu and noodles are available. Earlier, we served only foreigners but not the locals. People came from Colombo to our restaurant. Later we started the takeaway service for rice, kotthu, and noodles. We created a name for our food here and have recovered slightly. Now it is well-established so there is no doubt that it will survive (Prabath).

A very common approach would be to cater to the local market at a lower (discounted) price (Kottika et al., Citation2020).

Changes are also required in the way of doing business from time to time. For example, a room let out for Rs. 7000 is provided for Rs. 3500 with a 50% discount.

In view of this reality, tourism SMEs have learned to diverse markets in both scenarios. They learned all these from the various crises their firms have faced.

Engaging in different markets to survive during a sustained crisis

In the event of a long disruption, such as a pandemic, SMEs engage in other businesses until the situation returns to normal.

Although this is my preferred trade, this is a high-risk business. And it will continue to be like that. It would be a smart thing to engage in another business too in parallel. In fact, I have already started one (Udara).

Being innovative is essential for resource constrained SMEs to be resilient in a changing environment such as one caused by a crisis (Burhan et al., Citation2021; Giannacourou et al., Citation2015). Although they were able to overcome the challenges of previous crises that only lasted for short periods, long-term crises convinced SMEs that they needed to adopt a different approach such as catering to alternative markets by expanding beyond their regular business operations. Mahesh, with his 40-plus years of business experience, explains the importance and the necessity of business diversification as follows.

There is a saying that when we make an omelette, we mix all the eggs together, and if one egg is rotten, the omelette will also be rotten. Similarly, rather than investing all our resources in one industry, there should be something different for entrepreneurs to pursue.

Adaptive capacity of SMEs in the post-crisis phase effectively enabled them to deal with the crisis and minimise its adverse effects (Fang et al., Citation2020). Earlier empirical studies have asserted the need for SMEs to be more adaptive and innovative in all areas, including new technologies, product diversification, company conscientiousness, and internal restructuring, while withdrawing from non-profitable activities to be resilient to crises (Burhan et al., Citation2021; Giannacourou et al., Citation2015). Furthermore, the SMEs’ flexible nature made it possible to re-order the SMEs’ priorities within a short period. This study reveals how SMEs learn to use such flexibility for market diversification during a crisis.

To be proactive in the face of a crisis

SMEs demonstrate a proactive posture due to many reasons such as limited resources, a narrow focus on money, reduced awareness, poor perception of risk, insufficient experience, etc. (Doern, Citation2016; Toubes et al., Citation2021). Usually, SMEs do not have any proactive measures in place to deal with future disasters, such as a crisis management plan (Fasth et al., Citation2021; Runyan, Citation2006; Schepers et al., Citation2021). Although most SMEs have demonstrated nothing more than ad hoc behaviour as a response to crises (Fasth et al., Citation2021; Schepers et al., Citation2021), scholars have argued that organisations may in fact be able to use adversity to their advantage if they have a good plan in place (Fasth et al., Citation2021).

However, the findings of this study indicate that SMEs have improved their proactive behaviour lately. Due to previous crisis experiences, many SMEs are now well equipped to make use of proactive crisis management mechanisms, even to deal with unexpected natural disasters that have never been experienced before. Repeated exposure to such extreme events has convinced SMEs to adopt possible mitigating measures and be prepared to face such dangers. Even though SMEs may claim they are adopting a proactive attitude, most entrepreneurs are able to arrange only the minimal safeguards as precautionary measures against crises due to various reasons. None of them claimed to have in place a crisis plan, crisis team, or regular training program for crisis management.

Risk transfer mechanism through insurance

Most of the entrepreneurs stated that they have obtained insurance coverage for their properties, having learned hard lessons from previous disasters such as tsunamis. Following the tsunami, SMEs learned a lot about the bare minimum of proactive measures they should take.

Yes, the tsunami taught us a good lesson. When it struck, Rupees 50 Mn worth of goods, building, vehicle and all were lost. Now, whatever the things we do, we get the insurance first (Nihal).

As Chairman of the Tourism Traders Association, Mahesh described how, following the tsunami, he encouraged members to obtain comprehensive insurance coverage. He went on to say that businesses have benefited greatly from insurance because it has vastly improved their capacity to recover from a disaster.

So, I got the insurance and advised our members also to do the same. They benefited from it because, after three years, the sea water and the floods that occurred in the Madilla area caused damage to some properties. The affected parties received the insurance benefits and that was sufficient for them to return to normal. It was indeed a big relief to them. They may not have recovered if they had not been insured. Such incidents have happened to others. What we must learn is that we will be vulnerable to the crisis without insurance.

According to him the tsunami was the main reason he purchased business insurance.

Precautionary measures against vulnerability to crisis

Past experiences improve people’s thinking, creativity, and desire to learn new skills by stimulating them intellectually (Alonso et al., Citation2021). It is critical that SMEs take the necessary precautionary measures to deal with and respond effectively to crises. Former crisis experiences alter SMEs’ perceptions of the crisis and the risks associated with crises. SMEs report an increase in uncertainty following the outbreak of a crisis compared to the pre-crisis phase (Giannacourou et al., Citation2015), owing to the disagreeable experience of dealing with the crisis; inevitably, this greatly influences one’s perception of the risks associated with a crisis. Other than the different types of crises, SMEs have practised what they learned during the initial stages of sustained crises. Siril described how they were able to continue business operations in the latter phases of the pandemic due to the experience gained during the 1st wave of Covid-19.

During the second wave, as we had already gone through the health rituals, we never closed this restaurant. We opened it for just 4 hours and did the business only during those hours. These are the experiences that we actually went through. That is all I have to say.

Several respondents stated that they had trained their employees to deal with specific types of crises. Especially after the tsunami, entrepreneurs, particularly those operating near the beach, trained their staff to deal with any tsunami crisis with the limited resources available.

Then of course, we had an alert system that issues warnings to the manager through his phone. He can connect to this international website that gives early warning of impending disasters. That was another useful thing (Saman).

Accordingly, the findings indicate that many SMEs had adopted specific proactive measures based on previous crisis experiences to respond more effectively to future crises.

If something unexpected happens, we know how to control it by making suitable adjustments. It was not like that earlier. Just take the staff salary… we have to make provisions for it every day. With the experience we have gained, we know if we did not reserve some funds for that purpose today, it will be impossible to pay their salaries tomorrow (Prabath).

This indicates that although SMEs are not generally involved in formal crisis planning, they had taken certain steps to prepare for such contingencies, due to their prior crisis experiences.

Experience in dealing with crises create embed knowledge in SMEs and help build a solid business

SME owners developed their self-efficacy through previous crisis experiences (Alonso, et al., Citation2021). The experiences of SMEs that had previously gone through a crisis and successfully overcome them helped them to attain high self-efficacy. Some people may use emotional coping mechanisms due to low self-efficacy and a lack of control over the crisis (Fang et al., Citation2020). SME entrepreneurs develop a positive attitude and a problem-focused coping mechanism to deal with a stressful situation caused by a crisis phenomenon. There is also the option of an emotional-coping mechanism (ignore the problem or pray). This has the potential to improve crisis response effectiveness and reduce post-crisis distress. SME owner-managers have experienced various crises throughout their careers, and the findings indicate that they have confidence in their ability to recover from crises. However, because of the rapidly changing business environment, it would be prudent for SMEs to avoid their general tendency to over-optimise decision making (Gruman et al., Citation2011). Learning from former crisis experiences may assist SMEs to develop a positive attitude and foresee the potential crisis vulnerability of SMEs (Schepers et al., Citation2021).

Developing self-efficacy by learning from previous crisis experiences

Self-efficacy is an essential characteristic necessary to build individual resilience that contributes to the collective organisational resilience required to cope with the uncertain environment created by such crises (Branicki et al., Citation2017). Learning through their own trade experience helped entrepreneurs to develop their self-efficacy, making them resilient enough to prevail in a crisis environment. Based on their experience in the industry, most entrepreneurs believe they should be able to deal with crises, even if they last for a few years, as in the case of the Covid crisis.

Even during the Covid period, I learned that the tourism industry would not collapse. Therefore, we should not give up. We must seize the opportunity to move forward at this time (Mahesh).

As entrepreneurial learning is a social process in which the learning takes place through interaction with the environment, it is vital for businesses to learn from crises (Schepers et al., Citation2021). The prior crisis experiences of entrepreneurs highly influence their perception of crises and their reactions towards crises (Schepers et al., Citation2021).

When we face a crisis, we should not go behind others seeking their support. We should have the courage to recover on our own. (Dakshi).

The findings revealed that SMEs use various mechanisms to cope with crises based on self-efficacy and in the process have learned to deal with crises more effectively.

Positive thinking backed by the country’s religious teachings

Crisis usually generates negative emotions such as fear (Fasth et al., Citation2022) and anxiety (Coombs, Citation2015; Fasth et al., Citation2022). Usually, emotions would run high during the first few months of a crisis, then gradually wane (Doern, Citation2021). Hence, individuals who are easily upset may find it difficult to cope, while those who are more stoic will react mildly and cope better. The ability to make quick and sound decisions while under pressure is the key trait required for effective crisis management (Fasth et al., Citation2021). In addition, positive thinking on the part of entrepreneurs will make it easier for them to manage any crisis more effectively. This positive thinking appears to have a link with the country’s religious culture. When asked to explain the reasons for the quick recovery from crises, the respondents usually pointed to Buddhist cultural beliefs. Through former crises experiences, entrepreneurs had developed positive thinking by assuming that it will be possible to recover soon, regardless of the nature of the crisis. Such beliefs may positively contribute to effective crisis response. Jane draws her strength from the religious teachings of our culture and Lord Buddha’s teaching on cause and effect, known as ‘Karma’.

Yes…. From my observations I can say that when something bad happens in this country, we recover quickly. We handle the situation fairly well and manage to get out of a disaster eventually in Sri Lanka. After every crisis in the past we were able to recover quite soon. The country managed to escape from every situation gradually. Maybe it was some kind of blessing for the country.

In contrast to that, sometimes respondents accept any crisis they cannot avoid philosophically and resign themselves to the reality of the situation they face with courage.

The most disruptive incident was the Covid-19 pandemic. Prior to that, the biggest one was Saharan’s attack. Those two events had the greatest impact on tourism. Other than those, there were no critical incidents. That does not mean I am a rich person but I can bear both loss and profit (Prabath).

According to the findings, some entrepreneurs quote certain religious teachings to explain the incidents they have encountered in their business careers. They primarily attempt to develop a positive attitude by following Buddhist teachings. More importantly, entrepreneurs have developed their self-confidence by dealing regularly with crises and devised practical problem-focused coping mechanisms rather than relying on emotional coping mechanisms.

Discussion

According to the findings, Sri Lankan tourism SMEs have proved vulnerable to various types of crisis over the last few decades. Much like the findings of Doern (Citation2021), the findings of this study indicate that SMEs have improved their survival capacities over time. The findings confirm that experiencing crises tends to create knowledge in SMEs that can be used effectively to cope with future crises phenomena. Hence, this section evaluated the findings by applying several selected theories.

In keeping with the experiential learning process that assumes ‘knowledge is created through the transformation of experience’ (Kolb, Citation1984), entrepreneurs described their experiences that created their knowledge on crisis. The characteristics of experiential learning were described by Kolb and Kolb (Citation2009), who stated that learning is best conceived as a process rather than as an outcome. According to them, all learning is re-learning, where learning is the process of adaptation to the world, involving transactions between the person and the environment. Accordingly, this study’s findings emphasised the organisational context of learning. It considers individuals as the only entities capable of learning within an organisation, particularly those playing the role of owner-manager and other employees. Based on that, the study discussed the importance of the cognitive perspective within organisations, which refers to acquiring, storing, and applying entrepreneurial knowledge and embedding such knowledge for future use, such as for problem-solving (Young & Sexton, Citation1997), where it considers the organisational crisis response. Besides SMEs learning from their own experiences (such as from own business and previous job), vicarious learning from their close relationships (with family and friends/strong bonds) plays an important part. The experiences of immediate family members (close ties) can have a significant influence on the SMEs’ crisis learning and knowledge creation process. Moreover, the study presents new material on the experiential learning of organisations by identifying learning as the process of adaptation and transformation, which involves a transaction between the ‘individual and environment’, as well as a process of knowledge creation (Kolb, Citation1984). SME crisis learning can also be seen as a social activity as it is influenced by the religious and cultural sentiments of society.

At the organisational and industrial level crisis learning allows SMEs to share their experiences and create a shared understanding of crisis management that complies with the CoP theory. The study has assessed how entrepreneurs view the collaboration between three levels of employees within SMEs, namely at the individual, group, and organisational levels (Crossan et al., Citation1999), as this learning is an evolving process that facilitates the exchange of knowledge on crisis among employees over time (Romme & Dillen, Citation1997) Furthermore, the tourism business community gathers formally (through associations) and informally (such as at weddings). Hence, the application of CoP theory could be identified as the expansion of collective responsibility for managing the knowledge possessed by different groups within the SMEs for better crisis response. Thus, links between various parties help transfer knowledge among people across organisations and even geographic boundaries. Furthermore, networking is likely to enhance knowledge by expanding the resource base of SMEs, particularly during times of crisis, as it creates new opportunities for vicarious learning.

Several aspects of the CoR theory are supported by the findings, namely by the different behaviours manifested as a response to stressors and through the identification of SMEs’ resources. The findings contribute towards defining the ‘energy’ type of resources. It is the type of resource that organisations could use to acquire other types of resources. According to the findings of this study, SMEs can get more of the same kind of resources through the energy type of resources (e.g. acquire crisis knowledge through the experiences obtained during a crisis). Nevertheless, the CoR theory has been criticised as the theory defines resources too broadly (Halbesleben et al., Citation2014) as anything that could be valuable. Scholars stated it should value organisational component of resources are necessary to link the strategic approach to resource identification. Hence, this study has identified organisational resources as anything that helps with achieving goals. Due to its emphasis on the strategic role that crisis learning and knowledge play in organisational survival (goal), this study has added to the theory in this regard as it aligns with the organisational strategic perspective that has been defined. Furthermore, it is possible to identify knowledge and experience of crises as valuable resources that help SMEs to realise their organisational objective of effective crisis management and long-term survival. This study distinguishes between the different behaviours of SMEs in actual and potential crisis situations such as when there is a real loss of resources and when there is a threat of the loss of resources. The extant theory is also criticised as it does not differentiate between these two circumstances and neither does it consider the difference in behaviour. Therefore, scholars have stressed the importance of detecting the differences in the SMEs’ involvement between these two scenarios (Halbesleben et al., Citation2014), which is a matter addressed by this study. The reactive behaviour of SMEs becomes evident when the entrepreneurs become increasingly concerned during the actual phase of crisis as they experience the steady loss of their resources. It also turns out that they are more eager to learn about a crisis only when they really experience it. Accordingly, this study recognises that SME business owners feel compelled to encourage knowledge sharing among their employees after suffering the loss of resources brought on by crises. As witnessed comparatively a higher level of involvement could be seen in staff training on tsunami and tsunami warning systems and communicate with employees during the Covid-19 pandemic.

The findings align with the triadic model of Rae (Citation2004) due to the high interdependence between the source of learning and what SMEs learn during crises. Entrepreneurs acknowledged the importance of the learning process for them in their capacity as the owner-managers of SMEs. Thus, the findings revealed that SMEs rely heavily on their own experiences of previous crises and their early career experiences. By early career is meant the previous employment as well as vocational and professional training (Rae & Carswell, Citation2001). As such, previous crises faced by SMEs during their early career engagements appear to be important. Although networking for SMEs’ resource expansion was discussed during the crisis period (Herbane, Citation2019), networking for learning was rarely discussed with SMEs. However, this study emphasised the contribution of close ties in a crisis as that enabled the management and staff to better respond through their knowledge and skills compared to weak ties. SMEs must maintain strong relationships with their close ties due to the nature of the business. Furthermore, the contribution of family members and close friends became vital during a crisis, as the regular employees often had to be laid off or lost. The participatory learning approach has the potential to expand learning opportunities for SMEs while alleviating resource constraints. In some instances, such as Sahan’s and Shammika’s businesses, they had to rely on experience sharing and embedded knowledge after the sudden death of the original owners. Rasika’s daughter took over the business and ran it with the help of other employees during her father’s illness. Aside from such proven networking of close ties, it is critical for SMEs in the learning process to establish an industry network outside of their close ties as well. However, when it came to the group and organisational levels, respondents stated that there was the potential for experience sharing and knowledge creation at each organisational level, though there were some limitations. Respondents expressed their willingness to share knowledge and experiences including crisis management knowledge with their family members. Thus, the findings contribute to the CoR theory’s problem-focused strategies by confirming how entrepreneurs are compelled to generate knowledge based on previous crisis experiences and how they act accordingly. Hence, this distinguishes between the entrepreneurs’ behaviours during actual and potential loss of resources.

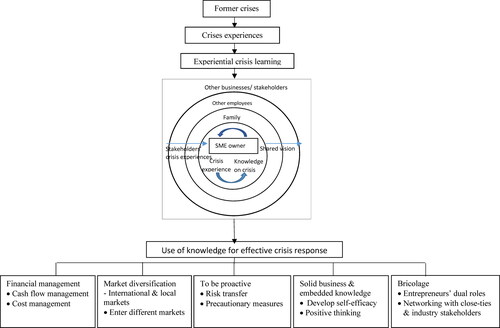

Finally, the findings of the study were used to develop a model of the SME’s experiential crisis learning process (refer to and ).

Accordingly, the model demonstrates that previous crisis experiences direct SMEs to learn about crisis management. The central part of the model illustrates the experiential learning/knowledge creation process within SMEs, highlighting the main contributing parties to the process. Accordingly, the inner circle represents the core of the SMEs, which is centred on the SME owner-managers. This circle primarily represents the SME owners’ experiences, which are used to create knowledge for the organisation. Furthermore, it is at the core of the process that embedded knowledge is gathered. The circles at the next level represent the SME owners’ family members. According to the respondents, SME owner-managers primarily gather experiences from their parents. Similarly, family members are a group of people within SMEs who are conversant with SME operations, including crisis management, and know the owner/manager. Then, the third level represents the organisation’s other employees, who are more distant from the owner-manager. The final level consists of other businesses with which SMEs could share their experiences. Due to the nature of the SME the close ties are more involved in the learning process while the influence of other employees (except the more loyal employees and employees who have been working for a long time) and industry stakeholders is low compared to the close ties. All of this demonstrates that the knowledge created through former crisis experiences can be very useful to the SMEs as they will be able to apply such knowledge for effective crisis response in future.

Managerial and research implications

The study offers a comprehensive picture of SME crisis learning behavior when confronted with the wide range of crises to which they are highly vulnerable. SMEs gain a better understanding of the need for competent crisis management practices for SMEs to survive in the long run. Armed with such knowledge, SMEs may be able to adapt to the situation strategically. The study stresses the relevance of crisis learning, which would be a good strategy for SMEs to overcome resource constraints and improve their crisis resilience. Supporting organisations will be assisted to identify the actual requirements of crisis management services that SMEs might require them to provide. Hence, supporting organisations would encourage the crisis learning of SMEs and assist them accordingly. The government and policymakers could use the information to better understand the issues that need to be addressed and the policy implementation or revisions that are required.

Conclusion

The purpose of this study is to investigate what Sri Lankan Tourism SMEs have learned from the various and frequent crises that they confronted and how the SMEs used their knowledge and experiential learning to come up with effective responses for subsequent occurrences of crises. The qualitative inquiry found that the SMEs used their knowledge to implement strategic approaches based on prior crisis learning, such as bricolage, financial management, market diversification, developing a proactive posture, and building a more solid business.

This study contributes to the existing literature in several ways. First, this is one of the major studies based on real time data collected on various crises faced by SMEs. An in-depth analysis of the subject will constitute a qualitative study on SME crisis management, of particular relevance to developing economies (Asgary et al., Citation2012), of which there are very few in the existing literature. Second, rather than considering a single type of crisis this study evaluated several types that have badly disrupted the business activities of SMEs. Third, the study evaluates the opportunistic view, which is mostly overlooked in formal crisis studies. More importantly, the study evaluated how the stress of dealing with crises provided the impetus for SMEs to learn more about crises to create the knowledge that could be used effectively for future crisis response. Fourth, the dual aspect of the SMEs’ entrepreneurship was applied to evaluate the learning opportunities available for them to learn about crisis both as an entrepreneur as well as a community member (Runyan, Citation2006). Thus, this study has explored the learning approaches adopted for both individual and participatory learning in the organisational context, information about which is currently lacking in the literature on SME crisis management. Therefore, the study’s findings positively contribute to SMEs’ organisational learning while also strengthening the dynamic capabilities of tourist SMEs, allowing them to expand their resource base through a social coping mechanism (participatory learning) and thus survive in the long run. In general, this research may fill a gap in the literature identified by Wang (Citation2008) regarding how learning can be applied to contribute to effective crisis management. Furthermore, as it evaluates the impact of resource loss on the physical and psychological well-being of entrepreneurs, the CoR theory will be enriched by the findings of this research. The findings of the study may prove helpful to SMEs and other stakeholders to better understand how to cope with crises and the potential benefits of adopting an experiential learning process.

The inherent limitation of this qualitative study is in generalising the findings, but this is a matter that could be addressed by scholars in the field. Hence, future researchers can apply the proposed model in their studies and test it further. Alternative study methodologies, such as Action research, might be used to investigate and assess the potential remedies. Furthermore, the study is mainly based on cross sectional data. Besides, longitudinal data may provide more informative findings that show behavioural changes over a period. This study is based on a single country, even limited to a single province of the country. These could be used to compare the data in different contexts by extending the investigation to cover different geographical locations, which could even include other countries.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Kalutara Koralalage Nilanthi Britto Adikaram

Dr. K. K. N. B. Adikaram is a Lecturer at the University of Ruhuna, Sri Lanka. She earned her PhD from the University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka. Her research interests include crisis management, organizational learning, SMEs and tourism business.

Hapugoda Achchi Kankanamge Nadee Sheresha Surangi

Professor H. A. K. N. S. Surangi is a Senior Lecturer at the University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka. She completed her PhD at the University of Lincoln, United Kingdom. She has a longstanding interest in female entrepreneurship, gender, ethnic minority entrepreneurship, entrepreneurial networking and small business development in Asian countries.

References

- Alase, A. (2017). The Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA): A guide to a good qualitative research approach. International Journal of Education and Literacy Studies, 5(2), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijels.v.5n.2p.9

- AlBattat, A. R., & MatSom, A. P. (2014). Emergency planning and disaster recovery in Malaysian hospitality industry. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 144, 45–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.07.272

- Alonso, A. D., Bressan, A., Kok, S. K., Sakellarios, N., Koresis, A., O’Shea, M., Buitrago Solis, M. A., & Santoni, L. J. (2021). Facing and responding to the Covid-19 threat – an empirical examination of MSMEs. European Business Review, 33(5), 775–796. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-09-2020-0231

- Argote, L. (2011). Organizational learning research: Past, present and future. Management Learning, 42(4), 439–446. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350507611408217

- Argote, L., & Miron-Spektor, E. (2011). Organisational learning: From experience to knowledge. Organisation Science, 22(5), 1123–1137. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1100.0621

- Asgary, A., Imtiaz, M., & Azimi, N. (2012). Disaster recovery and business continuity after the 2010 flood in Pakistan : Case of small businesses. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 2, 46–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2012.08.001

- Battisti, M., & Deakins, D. (2015). The relationship between dynamic capabilities, the firm’s resource base and performance in a post-disaster environment. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 35(1), 78–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242615611471

- Bolas, H., Wersch, A., & Flynn, D. (2007). The well-being of young people who care for a dependent relative: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Psychology & Health, 22(7), 829–850. https://doi.org/10.1080/14768320601020154

- Branicki, L. J., Sullivan-Taylor, B., & Livschitz, S. R. (2017). How entrepreneurial resilience generates resilient SMEs. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 24(7), 1244–1263. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-11-2016-0396

- Burhan, M., Talha, M., Omar, S., & Hamda, A. (2021). Crisis management in the hospitality sector SMEs in Pakistan during COVID-19. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 98, 103037. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.103037

- Coombs, W. (2015). The value of communication during a crisis: Insights from strategic communication research. Business Horizons, 58(2), 141–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2014.10.003

- Creswell, J. (2007). Qualitative inquiry & research design (2nd ed.). Sage Publications, Inc.

- Crick, F., Eskander, S. M. S. U., Fankhauser, S., & Diop, M. (2018). How do African SMEs respond to climate risks ? Evidence from Kenya and Senegal. World Development, 108, 157–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.03.015

- Crossan, M. M., Lane, H. W., White, R. E., & White, E. (1999). An organisational learning framework: From intuition to institution. The Academy of Management Review, 24(3), 522–537. https://doi.org/10.2307/259140