Abstract

The purpose of this study was to investigate the numerous ways that entrepreneurship culture (EC) influences innovativeness. The conditional effect of EC on innovativeness is further examined in light of the various organizational tolerance levels and positioning levels. Data were gathered from 647 respondents chosen from the KZN Department of Education and quantitatively analysed using SEM conditional analysis and descriptive statistics. The results of the study demonstrate that EC has a substantial direct effect on innovativeness, but that it has no significant indirect effect through managerial support or work discretion. However, there is a conditional significant mediation with organizational tolerance even though there is no indirect influence of EC on innovativeness through work discretion. Therefore, it is advised that the administration of the Department of Education be expected to provide employees more flexibility and accept their (employees) mistakes in order to encourage them to work independently toward innovation.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

Being innovative can be defined as having the desire to develop fresh, practical solutions to problems or novel approaches to completing tasks (Escrig-Tena et al., Citation2022). According to Chebo and Kute (Citation2018), innovativeness is the ability to carry out a task in a novel and enhanced manner. Innovation and entrepreneurship ought to be viewed as continuous, supplementary endeavours. Scholars concur that innovation is essential to entrepreneurship and that it plays a critical role in business survival tactics (Kosa et al., Citation2018). Innovation is a key driver of entrepreneurship, while on the other hand, entrepreneurship promotes innovation and helps it achieve its full potential (Schmitz et al., Citation2017). In order to foster innovation, the organization must have a culture that encourages teamwork and allows employees to use their ideas (Pizarro et al., Citation2009). That is, firms that pursue innovation outcomes must have an organizational culture that strongly encourages and supports innovation because entrepreneurship is a driving force for economic and social development through the promotion of innovation (Leal-Rodríguez et al., Citation2016; Yun et al., Citation2020). According to Gjorevska (Citation2023), the cultivation of an entrepreneurial culture assumes a considerable influence in enhancing a firm’s standing by fostering the exploration of novel opportunities, embracing risk-taking, promoting innovation, facilitating proactive behavior in the market, endorsing autonomy, and instigating competitive aggressiveness.

A set of behaviours and practices through which individuals at various levels, autonomously produce and employ novel resource combinations to find and pursue opportunities is what is meant by entrepreneurial behavior (Escrig-Tena et al., Citation2022). Consequently, EC is defined as a combination of personal beliefs, managerial abilities, experiences, and behaviours that identify the entrepreneur in terms of their sense of initiative, risk-taking, ability for innovation, and management of firms’ operations (Nguyen et al., Citation2023). An organization with an EC is maintained by a dedication to innovation and experimentation (Cameron & Quinn, Citation1999). There is not however, enough research done on this kind of behavior in the literature (Escrig-Tena et al., Citation2022). Additionally, it is important to investigate the direct and indirect effects of entrepreneurial culture (EC) on innovation as this may help solve a number of issues that could guarantee improved innovation. Although the connection between EC and innovativeness has not been directly investigated, prior research has shown a positive correlation between organizational culture and individual invention outcomes (Liu et al., Citation2019). Despite the non-importance of EC’s direct influence on inventive work behavior, EC’s involvement in fostering innovation is significant in an indirect manner (Nguyen et al., Citation2023). To do this, it may be necessary to evaluate a number of variables as mediators between EC and innovativeness. Therefore, this study tests the mediating role of management support and work discretion on this supposed relationship. Besides, numerous scholars have emphasized the significance of managerial support in igniting entrepreneurial activities within the business (Baskaran, Citation2021). For instance, Endenich et al. (Citation2023) argued that EC has a positive relationship with management support and innovativeness. The support of top management is found to be a potent variable in promoting innovative work behavior (IWB) (Nguyen et al., Citation2023; Sultan et al., Citation2022). Previous research indicates that entrepreneurs need independent thinking to come up with new ideas. For instance, the presence of work discretion is anticipated to increase employees’ propensity to be more creative (Baskaran, Citation2021). Studies such as McMurray et al. (Citation2021) and Evans (Citation2020) revealed that work discretion plays a role in the relationship between EC and innovativeness. In particular, the study by McMurray et al. (Citation2021) found that work discretion is one of the factors that contribute to the corporate entrepreneurship climate (McMurray et al., Citation2021). These justifications encourage the researchers to examine the possible indirect effects of EC on inventiveness through work discretion. Workers’ psychological requirements need to be taken into account for individual creativity when the effect of organizational culture on employees’ inventive behavior is ambiguous and depends on particular circumstances and mechanisms (Liu et al., Citation2019). Thus, the role of work discretion is considered.

Research has shown that individual level factors, such as the employee’s job position, can influence their innovativeness (Parzefall et al., Citation2008). Besides, adopting tolerance has advantages such as fostering creativity through free exchange of ideas across a wide range of knowledge, respect, and interpersonal trust. Employees’ organizational tolerance has a significant impact on their innovativeness (Ul Haq et al., Citation2017). According to Kriegesmann et al. (Citation2005), organizations with a culture that discouraged creativity and fearlessness would become less adept at innovation. A culture that embraces failure tolerance, promotes open communication, encourages work discretion, and upholds fairness has the potential to foster innovative behaviours among employees (Khan, Citation2021). Nevertheless, there exists a dearth of substantial evidence to support the impact of employee job position and organizational tolerance on employee creativity (EC) with regards to innovativeness. Hence, it is imperative to conduct empirical investigations to determine the influence of organizational tolerance on employee creativity in the context of innovation. Additionally, the degree of the impact on EC and management support is anticipated to be determined by the various levels of management positions.

It might be argued that the Department of Education’s poor entrepreneurial propensity and culture account for its inability to change and perform better. It was discovered that developing nations’ EC value systems and business methods varied from those of the developed western nations’ entrepreneurs (Alwis & Senathiraja, Citation2005). Malan (Citation2016) indicates that the Department’s capability to foster change and sustainability within itself has been constrained by its low entrepreneurial tendency. This means that, the organization needs new entrepreneurial management with a revolutionary and innovative mindset. Despite the evidence of the benefits that can be generated by entrepreneurially-orientated strategies in improving organizational performance, the Department of Education in South Africa is still lagging behind other developing countries in the quality of the schooling system (Van der Berg et al., Citation2011). Furthermore, it can be argued that the limited entrepreneurial inclination by the Department of Education can account for its inability to adapt and perform better. However as indicated by Dhliwayo (Citation2017), public sector departments can and should be entrepreneurial.

This study contributes in many ways, first, most of the previous studies are conducted in business firms. In testing these relationships, focusing on a public sector institution makes this study unique. By examining the relationship between EC and innovativeness, this research can shed light on the factors that drive innovation within public sector organizations. Theoretically, this study draws on existing entrepreneurship literature and applies and adopts from it what is relevant for the Department of Education in terms of developing EC and innovativeness. In addition the study’s importance should be understood also in the context where, Shockley et al. (Citation2006) contents that existing theories of public sector entrepreneurship, are inadequate to account for observed entrepreneurial behaviour. Despite a dearth in the study of public sector entrepreneurship observed by Morris and Jones (Citation1999), not much activity has been observed some 20 years later. By analyzing the various circumstances in which the factors are related to one another and focusing on one African country, the study offers first-hand evidence of the relationship between EC and innovativeness.

Second, by clarifying the elements of EC and how it contributes to the enhancement of innovativeness, the research contributes to contemporary research and develops deeper knowledge. For example, by identifying the cultural elements that foster innovation, policy-makers and organizations have the ability to shape a culture that support the growth of start-ups and entrepreneurial ventures. However, it is important to note that the relevance of factors such as management support and work discretion in this relationship has not yet been statistically tested in a public sector context. Therefore, this study aims to examine the mediating role of management support and work discretion on the relationship between EC and innovativeness. This unique approach not only investigates the role of management in fostering innovation, but also delves into the dynamics of this relationship, providing actionable insights for organizations and informing efforts in management and leadership development. Additionally, the study explores how EC influences the level of discretion employees possess, and how this, in turn, impacts their ability to be innovative.

The role of variables including the relationship between employees and their supervisors, leadership style, workplace interactions, and individual psychological aspects was emphasized by studies on private sector situations (Wynen et al., Citation2020). However, the role of organizational tolerance and organizational position level are understudied. Thus, testing the moderating role of job rank and organizational tolerance is an important contribution this study makes. That is, the study contributes to the development of the theory by debating the significance of these factors and by elaborating the logics behind the contribution. Examining these effects is important for several reasons. Examining the job rank as a moderator between EC and innovativeness provides distinctive perspectives on the effect of position level, reveals impediments within organizations, customizes interventions, and enhances comprehension of power dynamics in EC and innovation. Additionally, investigating organizational tolerance as a moderator between EC and innovativeness yields exclusive insights into the influence of cultural norms, and risk tolerance.

Thirdly, the study will guide policy makers and top management in inclining their organisations to develop an EC, which serves to cultivate innovativeness and improve public service delivery. The EC’s significance, creativity and passionate innovation are embedded in the entrepreneurial approach which can contribute to the Department of Education improving its performance. Above all, the study advises a strategy where managers tend to develop EC themselves and be focused more on seeking opportunities within the rest of the education department in order to build innovativeness. Thus, this study tends to answer three research questions; (1) To what extent EC influences innovativeness in the Department of Education? (2) How does management support and work discretion mediate the effect of EC on innovativeness? (3) To what extent does organizational tolerance moderate the effect of EC on innovativeness? (4) To what extent does position level moderates the effect of EC on innovativeness? Given this, the study tends to test both direct and indirect effect of EC on innovativeness.

2. Theory and hypotheses

2.1. Theoretical foundations

The study of EC and innovativeness is founded on several theoretical underpinnings that aid in comprehending and analysing the interrelationship between these constructs. Some commonly employed theoretical frameworks in this realm of inquiry include institutional theory, innovation diffusion theory, resource-based theory, and prospect theory. For instance, institutional theory and innovation diffusion theory propose that the motivators for adopting an organizational innovation may vary among organizations and may be contingent on the timing of the innovation. Despite the prevalence of research investigating the post-adoption diffusion stages of acceptance, routinisation, and assimilation in academic fields, there remains a dearth of studies that integrate these constructs and their constituent dimensions into a cohesive framework (Martinsuo et al., Citation2006). Furthermore, the resource-based theory, when combined with institution-based theory, facilitates the comprehension of the relationship between political connections, acquisition of entrepreneurial resources, the institutional environment, and corporate re-entrepreneurial performance (Zhao et al., Citation2019).

Institutional theory is closely intertwined with the examination of EC and innovation. Institutions, encompassing the normative, regulative, and cognitive facets of social life, exert a formidable influence on entrepreneurial processes and outcomes (Hoogstraaten et al., Citation2023). They shape who assumes the role of an entrepreneur and how opportunities are generated and recognized (Sine et al., Citation2022). However, scant research has shed light on how alterations in the institutional environment can substantially transform these undertakings’ processes and outcomes. Webb et al. (Citation2011) endeavour to bridge this gap by integrating research on marketing activities, the entrepreneurship process, and institutional theory. By employing institutional theory as a theoretical framework, Audretsch and Belitski (Citation2017) shed light on organizational changes resulting from institutional pressures to innovate.

The alternative theoretical framework for the investigation of electronic commerce and innovation, for example, is Resource-based theory, which highlights the significance of a firm’s internal resources in attaining sustainable competitive advantage (Alvarez & Busenitz, Citation2001). It has become increasingly paramount in comprehending entrepreneurship and its outcomes, such as innovation (Carnes & Ireland, Citation2013). According to the Resource-based theory, entrepreneurial enterprises encounter challenges in acquiring innovation resources due to inadequate production, operations, management experience, and limited social reputation (Li et al., Citation2023). Furthermore, this theory offers a firm-oriented perspective that aligns with entrepreneurial theory (Aragón-Sánchez et al., Citation2017). Consequently, Resource-based theory plays an indispensable role in comprehending the correlation between EC and innovation, providing valuable insights into the internal resources and capabilities that drive entrepreneurial success.

The other underpinning theories in EC and innovation studies is innovation diffusion theory. Research indicates that there are additional, more detailed factors within the realm of innovation diffusion theory that influence the adoption of technological innovations (Wu et al., Citation2013). The findings support theoretical development and suggest synergies between innovation diffusion theory and the information processing perspective. The objective of Laforet (Citation2016) to examine the impact of organizational culture on organizational innovation performance concluded that, an inwardly focused culture, such as the founder culture, hinders innovation, whereas an outwardly focused culture, such as an external orientation culture, has a positive effect on innovation performance. Additionally, Joseph and Wood (Citation2020) propose a framework for analyzing the innovation behavior of established organizations in the space sector, aiming to achieve Disruptive Innovation. According to the diffusion of innovation theory, perceptions of an innovation are predictive of whether an individual or organization will adopt or reject it, and these perceptions are influenced by internal and external factors that shape the decision-making unit’s knowledge of the innovation.

Prospect theory, formulated by Kahneman and Tversky, has found extensive application in diverse domains, including the realms of entrepreneurship and innovation. This theory offers a descriptive framework for understanding decision-making in situations involving risk (Evstigneev et al., Citation2013). Within the context of EC and innovation, prospect theory has been employed to investigate the incentive culture that foster collaborative innovation, taking into account the influence of equity on the design of such mechanisms (Liu & Zhou, Citation2022). Furthermore, it has been utilized to scrutinize the decision-making behavior of enterprises engaged in green technology innovation, using parameter variations to simulate their behavioural outcomes (Wu et al., Citation2013). Additionally, prospect theory has been leveraged to construct decision-making models for both participants and initiators in the realm of innovation, exploring the ramifications of loss aversion and incentive levels on their conduct (Wang et al., Citation2019).

2.2. Entrepreneurial culture and innovativeness

One of the factors that determines innovative behavior in organizations is organizational culture (Pizarro et al., Citation2009). EC exerts a significant influence on the capacity for innovativeness within an organization by fostering an environment that supports continuous innovation (Tehseen et al., Citation2023). The establishment of an EC within the workplace not only encourages and nurtures entrepreneurial behavior but also cultivates organizational innovation (Danish et al., Citation2019). Empirical evidence from various studies highlights the positive impact of EC on innovativeness (Ahmetoglu et al., Citation2018; Ezeh & Abdulrahman, Citation2022; Sinaga & Candra, Citation2022). However, in order to assert that EC plays a pivotal role in promoting innovation within a company, it is imperative to distinguish between traditional innovation and the impact of EC (Pizarro et al., Citation2009). Leal-Rodríguez et al. (Citation2016)’s research also highlights the growing significance of cultivating an EC to produce innovative processes. Therefore, an entrepreneurially inclined organizational culture is necessary for continuous innovation and achieving a distinct competitive advantage.

EC encourages creative business practices across all of its sectors, which enables the foresight of market trends and possibilities (Leal-Rodríguez et al., Citation2016). However, Nguyen et al. (Citation2023), claimed that EC has no direct influence on employees’ inventive behavior. This finding requested the researchers to further test the relationship in order to clarify the direction and extent of EC effect on innovativeness. Besides, the findings of Ahmetoglu et al. (Citation2018), stated that EC has an indirect impact on employee innovation outcomes. Since the EC has no direct impact on innovation, Pizarro et al. (Citation2009) stated that it is impossible to demonstrate a positive relationship between the EC and innovation. This suggests that it is necessary to clarify these conflicting and contradicting findings. Therefore, it’s proposed that;

H1: EC has a positive and significant influence on the innovativeness of employees.

2.3. The mediating role of management support

Entrepreneurial culture has a positive relationship with management support and innovativeness (Endenich et al., Citation2023). In particular, management support is strongly associated with innovativeness (McMurray et al., Citation2021). That is, the support of top management is found to be a potent variable in promoting innovative work behavior (Nguyen et al., Citation2023; Sultan et al., Citation2022). Besides, studies have shown that the EC has no direct impact on innovativeness (eg., Nguyen et al., Citation2023). For instance, according to Ahmetoglu et al. (Citation2018), EC has an indirect impact on employees’ innovation results because managerial and psychological elements are involved in its development and on how inventive the organization is. In order to encourage and support entrepreneurial initiatives, management support has a crucial role to play, according to Morris et al. (Citation2008). Even though EC has an influence on creativity and innovation, without the assistance of management, entrepreneurial efforts will not produce the desired results on their own. Given this, managerial support is seen as one of the essential components that will enable the organization’s people to behave in an entrepreneurial manner (Baskaran, Citation2021a).

According to Janssen (Citation2005), organizational features, particularly management support, have an impact on employees’ innovative behavior. Since management support itself can be thought of as a part of EC, it is expected that the entrepreneurial roles already present in the organization will play a part in developing such a strategy and structure (Pizarro et al., Citation2009). This evidence indicates the need to test the role of management support in the relationship between EC and innovativeness. The degree to which management is willing to assist its employees in their entrepreneurial endeavours is thought to be the best way to stimulate entrepreneurial activity, including innovation, according to Bhardwaj et al. (Citation2007). However, Holt et al. (Citation2007) noted that there are still substantial variances in the management support construct when it comes to encouraging entrepreneurial activities like innovation.

Multiple studies have been conducted to examine the role of management support in relation to innovativeness. For instance, Pratama et al. (Citation2020) discovered a clear correlation between corporate entrepreneurship and customer satisfaction in the context of public sector banks. They also highlighted the significant impact of top management support in enhancing corporate entrepreneurship and ultimately leading to customer satisfaction. Similarly, Marra and Meng (Citation2023) determined that top management support plays a moderating role in the relationship between innovativeness and firm growth (FG). However, there is currently no empirical study that has investigated the mediating role of management support in the relationship between EC and innovativeness. This necessitates the clarification of the role of management support in the relationship between EC and innovativeness. Therefore,

H2: Management support positively mediates the relationship between EC and innovativeness.

2.4. The mediating role of work discretion

Job autonomy and employee work discretion have been examined in previous literature. In innovation research, autonomy has likely attracted the greatest attention (Parzefall et al., Citation2008). The study finds that various work environments link with the aspects of entrepreneurial activity in various ways (Escrig-Tena et al., Citation2022). That is to say, workplace autonomy, sometimes referred to as work discretion, is a powerful signal for supporting innovative behaviours among employees (De Spiegelaere et al., Citation2015). The role of work discretion in the relationship between EC and innovativeness has been established by McMurray et al. (Citation2021) and Evans (Citation2020). McMurray et al. (Citation2021) conducted a study and found that work discretion is a significant factor contributing to the corporate entrepreneurship climate. However, the mediating effect of work discretion between EC and innovation has not been thoroughly tested. Besides, Ahmetoglu et al. (Citation2018) conducted a study that revealed work engagement as a full mediator between EC and innovation output. Nevertheless, theoretical evidence suggests the need to examine the mediating role of work discretion in this relationship. This is because work discretion acts as a mechanism through which EC exerts its influence on innovativeness.

The association between autonomy and innovation is supported by other empirical data (Parzefall et al., Citation2008). In particular, employees who work in an environment where innovation and proactivity are valued, like EC, are more likely to be innovative (Nguyen et al., Citation2023). In exchange, Sia and Appu (Citation2015) reiterated that workplace liberty would foster creativity, noting that entrepreneurship is all about creating something new and that novelty is a by-product of innovation. According to Ahmetoglu et al. (Citation2018), EC has an indirect impact on employee innovation results because all employees must be involved for innovation behavior to be implemented successfully. Despite the non-importance of EC’s direct influence on innovative behavior, EC’s indirect promotion of innovation through psychological engagement is crucial (Nguyen et al., Citation2023). Therefore, there is a necessity to test the indirect effect of EC on innovativeness through variables such as work discretion. Following this line of reasoning, it is hypothesized that:

H3: Work discretion positively mediates the relationship between EC and innovativeness.

2.5. The role of organizational position level

Research has shown that individual level factors, such as the employee’s job position, can influence their innovativeness (Parzefall et al., Citation2008). Top management, co-workers, and resources like efficient information and communication technologies provide support for corporate norms and values (Nguyen et al., Citation2023). It should be noted that intermediate managers are more inclined to act entrepreneurially when upper management encourages it, and vice versa (Karyotakis & Moustakis, Citation2016). However, organizational level impacts alone are insufficient to promote innovation outcomes (Yadav et al., Citation2007). This highlights the need to comprehend the mechanism by which psychological engagement at a lower level of group impacts, acts as a bridging factor in converting organizational culture to individual innovative behavior (Nguyen et al., Citation2023). Entrepreneurial activities will not yield an expected outcome without an organization’s management intervention. A crucial component in developing such environments is the top management team’s strategic orientation toward entrepreneurial activities (Ireland et al., Citation2009). The research conducted by Ahmetoglu et al. (Citation2018) demonstrated that an EC plays a positive moderating role in the connection between an individual’s entrepreneurial personality and their output of innovation (Jankelová, Citation2022). Nonetheless, it is important to consider that employees’ job rank or position and EC may jointly have an effect on their level of innovativeness. Therefore, further investigation is necessary to comprehensively understand the specific mechanisms through which job rank or position may influence this relationship. Thus, it’s hypothesized that;

H4a: Organizational job rank positively moderates the effect of EC on workers innovativeness.

According to Kuratko et al. (Citation2005), management support includes providing employees with the resources they need to start their own businesses in addition to facilitating and fostering entrepreneurial behavior. While board room conversations pique the interest of top executives (Morris et al., Citation2011), management support has also been found to be helpful in motivating the organizational workforce to meet company goals. The significance of middle managers in fostering and enhancing entrepreneurial behavior among employees such as innovativeness has been proven (Escrig-Tena et al., Citation2022). Rutherford and Holt (Citation2007) noted that in order to spur innovation inside a business, senior management must grant employees sufficient freedom and discretion so that they can engage in entrepreneurial endeavours. Thus, it is important to test the role of the different levels of management within the organizations in shaping the effect of management support on innovativeness. Therefore, it’s hypothesized that;

H4b: Organizational job rank positively moderates the effect of management support on employees innovativeness.

2.6. The role of organizational tolerance

Adopting tolerance has advantages such as fostering creativity through free exchange of ideas across a wide range of knowledge, respect, and interpersonal trust. According to Kriegesmann et al. (Citation2005), organizations with a culture that discouraged creativity and fearlessness would become less adept at innovation. The organizational tolerance of employees is known to exert a considerable influence on their level of innovativeness (Ul Haq et al., Citation2017). It has been suggested that a culture that prioritizes failure tolerance, open communication, work discretion, and fairness can effectively foster innovative behaviours among employees (Khan, Citation2021). This implies that organizations should strive to create a supportive environment that not only encourages employees to take risks and learn from their failures but also grants them the autonomy to explore novel ideas and seize new opportunities (Tuksinnimit et al., Citation2015). Additionally, employees who engage in entrepreneurial activities should not be criticized when they make mistakes (Baskaran, Citation2021; Hornsby et al., Citation2002).

Early studies on innovation focused mostly on how well organizations could respond to and adapt to changes brought about by internal and/or external influences (Wynen et al., Citation2020). Considering the internal factors, a firm must be able to accept failure brought on by entrepreneurial initiatives in general, and the management team in particular (Wynen et al., Citation2020). However, these studies did not clearly test the effect of organizational tolerance in building positive EC that supports the development of innovation. This shows the need for further explanation on whether organizational tolerance for failure support building positive EC which can enhance innovation. This is because, a tolerant structural design is more likely to promote employees’ free and open exchange of ideas, which aids in the successful growth of innovative corporate entrepreneurial initiatives and produces more innovation (Jaworski & Kohli, Citation1993; Van de Ven & Poole, Citation1995). Besides such theoretical foundations, there is no sufficient studies that tested the moderating effect of organizational tolerance in the relationship between EC and innovation. Thus, it’s hypothesized that;

H5a: Organizational tolerance positively moderates the effect of EC on employees innovativeness.

Entrepreneurial-oriented work discretion includes the capacity to tolerate failure, granting decision-making authority without overbearing supervision and distributing power and responsibility (Ireland & Webb, Citation2007). Employees will be inspired to take chances and pursue their entrepreneurial aspirations as a result (Hornsby et al., Citation2002). In order to encourage employees to adopt innovative behavior, organizations should let individuals decide how their own job is done and refrain from criticizing them when they fail (Ireland et al., Citation2009). Because of this, employees should be more willing to innovate. Thus, it’s crucial to clarify the role of organizational tolerance in enhancing work discretion towards innovativeness.

H5b: Organizational tolerance positively moderates the effect of work discretion on employees innovativeness.

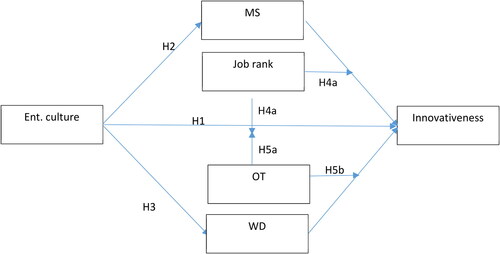

presents the conceptual framework and proposed hypotheses

3. Methodology

3.1. Research design

This research was designed as a formal study. The goal of a formal research design, according to Cooper and Schindler (Citation2008), is to test the hypotheses posed by the research questions. Accordingly, explanatory research design is employed. The time design of the study is cross-sectional. There is no time ordering to variables, because the data on them are collected more or less simultaneously and the researcher does not manipulate any of the variables. This research was conducted in 12 education districts of the KwaZulu-Natal Department of Education, South Africa.

3.2. Sampling design

The population of this study is those individuals employed in post level 2 to 6 in a managerial capacity. These individuals are permanently employed in the 12 education districts in the KwaZulu-Natal Department of Education (KZNDoE). According to KwaZulu-Natal Department of Education, Annual Performance Plan, 2020/21, the employee population of targeted managers in this department is 10 671 departmental heads, 4 605 deputy principals, 6000 principals, and 1 589 education specialists (chief, deputy and senior education specialists and circuit managers). That is, the total population is 22865 managers targeted for this study.

The sample size was determined by using a sample size calculator. A confidence level of 99%, a population proportion of 50%, and a margin of error of 5% were used in calculating the sample size. The targeted participants were put into four groups of Chief Education Specialist/Deputy Directors, Deputy Chief Education Specialist/Circuit Managers, Principals/Deputy Principals and Senior Education Specialists/Departmental Heads. A random quota convenience sample was drawn from people identified from middle management in the 12 districts in KZNDoE. A random sampling frame was used to minimize sampling bias. Out of the total population of 22 865 that was identified for the study, the sample size calculator came up with the sample size of 647 participants. Thus, using convenience sampling technique, middle management service members were selected and invited to participate. Questionnaires were distributed by the researcher to the 647 participants that were purposively identified from each of the 12 districts.

3.3. Measures and data collection instrument

In this study, perceptual measures were formulated based on prior studies documented in the literature review. The research instrument consisted of 4 sections. The first section of the questionnaire contains general biographical information, such as; gender, age, ethnic group and present job title in the Department of Education.

The second section contains EC items. Regarding this instrument, previous studies developed instruments for measuring EC. For instance, Bau and Wagner (Citation2015) developed an EC instruments consisting of 29 items, which contains LQE items, CII items, product and market know-how items, and task and responsibility items. Leal-Rodríguez et al. (Citation2016) also measured EC by adapting six items from a study performed by Cameron and Quinn (Citation1999), measured on seven point Likert scale 1 = I completely disagree with the statement; 7 = I completely agree with the statement. Further, Pizarro et al. (Citation2009) developed 14 items which can be categorized under two dimensions, innovation as new idea generator and culture as a vision of the future in the work place. By comparing these items, we have used 8 items to measure the EC construct, which is measured on a five-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. The sample item is ‘the organization embraces entrepreneurial behavior’.

The third section of the instrument contains constructs measured on multiple items rated on a 1–5 Likert scale, ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. It includes variables such as, management support (5 items), work discretion (5 items), and organizational tolerance (6 items). This instrument was originally designed by Kuratko and refined by Hornsby et al. (Citation2002). Thus, the items for management support, work discretion, and organizational tolerance were adopted from the items modified by Hornsby et al. (Citation2002) and used for this study.

The fourth section of the questionnaire measures the innovativeness construct. De Jong and Den Hartog (Citation2010) developed the innovative work construct that contains 10 items categorized under four dimensions. They asked participants to indicate their perceived innovative behaviour on a Likert scale, ranging from 1 = ‘never’ to 7 = ‘always’ (Nguyen et al., Citation2023). Besides, Leal-Rodríguez et al. (Citation2016) measured innovation outcome using 8 items on seven point likert scale ranging from 1 = I completely disagree with the statement; to 7 = I completely agree with the statement. Pizarro et al., Citation2009) used eight items to measure innovation. Given these items, we have modified the instruments to fit the education sector and used 8 items measured on a five-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. The sample item is ‘the department of education encourages development of new ideas that promote improved learner performance’.

3.4. Validity and reliability of the instruments

To check the validity and reliability of the questionnaire in gathering the data required for purposes of the study, a pilot test was carried out. The purpose of a pilot testing is to establish the accuracy and appropriateness of the research design and instrumentation. In this study, the data collection instrument (a questionnaire) was tested on 15 respondents to ensure that it was relevant and effective. They were not included in the final study in order to control response bias.

This study used both construct validity and content validity. For construct validity, the questionnaire was divided into several sections to ensure that each section assessed information for a specific objective, and also ensured that it was closely tied to the conceptual framework for this study. To ensure content validity, the questionnaire was subjected to examination by four randomly selected managers. They were asked to evaluate the statements in the questionnaire for relevance and whether they were meaningful, clear and impartial. On the basis of the comments and advice of participants during the pilot test, the instrument was adjusted appropriately before using it for the final data collection exercise. Their review comments were used to ensure that content validity was enhanced.

To assure the data reliability, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is used. The result is 0.913 for EC, 0.931 for innovativeness, 0.846 for management support, and 0.793 for work discretion. Besides, factor loadings were checked using exploratory factor analysis. The result indicates that all factor loads are above 0.7 which fulfilled the threshold.

3.5. Data collection and analysis procedures

Primary data was collected through the administration of questionnaires on departmental heads, senior education specialists, principals, deputy principals, assistant directors, deputy chief education specialists, circuit managers, chief education specialists and deputy directors in the twelve education districts in the KwaZulu-Natal Department of Education. The questionnaires were distributed by the researchers to twelve chief education specialists in the twelve education districts in KZN for filling in by the identified respondents, as discussed in the sampling procedure above. A total of 648 questionnaires were distributed by the researchers. The researchers collected the completed questionnaires four weeks after they had been distributed. A total of 426 questionnaires were collected. This represented an overall successful response rate of 65.7%. According Cooper and Schindler (Citation2008), a response rate of 50% or more is adequate. Babbie (Citation2004) also asserted that return rates of 50% are acceptable.

After data collection, information was sorted, coded and input into the statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) for the analysis and production of descriptive statistics and inferential statistics. Descriptive statistics such as mean and standard deviation is used to overview the existing practices and intentions. SEM conditional process analysis was used to test the significance of the influence of the independent variables on the dependent variable as well as the factor loading of indicators on the latent variable. This is because, currently the most widely accepted and cutting-edge techniques in use is PLS-SEM (Ahmed et al., Citation2020). PLS-SEM is extensively acknowledged in the realm of social sciences (Hair et al., Citation2019; Qalati et al., Citation2021, Citation2022). Additionally, the favourable aspects of utilizing SMART-PLS software encompass its comprehensive appeal and appropriateness for application, as well as its ability to provide thorough information regarding variables (Ahmed et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, PLS-SEM is commonly utilized when dealing with intricate models that involve intricate relationships, including direct, indirect, intervening, and causal mechanisms (i.e. mediation and moderation) (Qalati et al., Citation2022). Given these circumstances, we have employed PLS-SEM to examine the data and test the hypotheses.

4. Results and findings

This section presents the statistical results as well as its interpretation and discussions of the key findings. Quantitative data was analysed using various statistical methods including mean, standard deviation, and SEM conditional process analysis using SMART PLS PROCESS to test the statistical significance of the various independent variables on the chosen dependent variable.

4.1. Existing practices in the Department of Education

A Likert scale was used to assess all the variables except the positional level in the Department of Education in KZN. In respect of each statement, participants had to indicate their degree of agreement (5) or disagreement (1) with the statement’s content. Thus, a higher number agreeing with the statement suggests that the statement is perceived to be true. Likewise, a high number disagreeing suggests that the statement is perceived to be untrue. The Likert scale results were analysed using descriptive statistics and it was assumed that a score of greater than three out of five is an indication of a positive inclination towards the statement.

The outcome of the survey suggests that there is good practices in terms of EC, innovativeness, management support, organizational tolerance and work discretion. All the elements have an average mean score that is above three out of five (). Thus, it would seem that the elements for an entrepreneurial climate have a fairly strong presence, but there is still room for improvement. Comparatively, the constructs with highest mean scores were innovativeness (mean =3.817) and EC (mean = 3.606). The results indicate that these elements were perceived by participates to have a strong presence in the department. In general, the results in indicate that practices such as innovativeness, management support, organizational tolerance and work discretion are present in the Department of Education in KZN.

Table 1. Entrepreneurial climate survey results.

4.2. Entrepreneurial culture and innovativeness

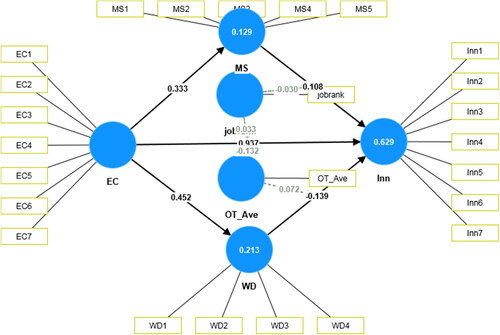

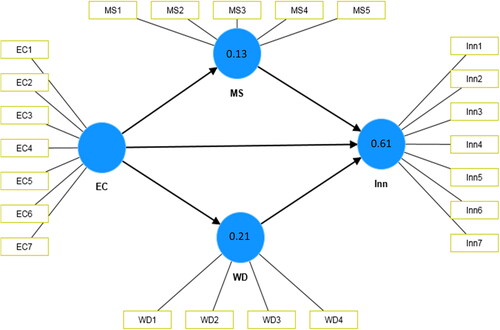

The results of adjusted R2 indicates that the independent variables influences the dependent variable innovativeness about 61%. Besides, MS and WD is explained by EC 13% and 21% respectively (). Regarding the coefficients of independent variables, the results are presented in .

Figure 2. Influence of entrepreneurial culture, management support and work discretion on innovation.

Table 2. Estimates of total effect.

The results of this study indicates that entrepreneurial culture significantly and positively affects innovativeness (β = 0.656; t = 15.624; P=.000). That is, hypothesis 1 is supported. This indicates that as the EC is developed within the organization, the innovativeness of employees will be enhanced. The entrepreneurial culture involves taking actions intelligently and pro-actively, as well as avoiding fear of failure which encourage individuals to try different and unique things. This leads to the enhancement in the innovativeness of workers in the Department of Education. Consistent with this study, previous studies supported this significant relationship. For instance, according to Leal-Rodríguez et al. (Citation2016), encouraging an entrepreneurial culture may help the organization make radical innovations. Investing in an EC will benefit businesses in terms of new technology, goods, services, or processes. In other words, employees’ innovative behavior increases in proportion to how highly they regard innovation and EC (Park & Jo, Citation2018). According to Pizarro et al. (Citation2009), businesses must have a culture that allows people to use their initiative and creativity to generate active knowledge, offering them the chance to develop ideas, and supporting learning (Pizarro et al., Citation2009). Thus, EC is a culture that enables employees to create and innovate. Because, EC includes the activities of performing tasks autonomously without close control of bosses, organizing resources innovatively to exploit opportunities, trying new ways of doing things by taking calculate risks, and introducing new products, markets and technologies, this frees more time for senior management to focus on other areas ().

Based on the aforementioned evidence, it is plausible to deduce that EC assumes a pivotal function in promoting innovation. This is due to the fact that a robust EC framework within an organization stimulates individuals to undertake daring endeavours, engage in imaginative thinking, and pursue new ideas. Consequently, EC facilitates an environment conducive to the flourishing of innovative practices by embracing risk-taking, cultivating a growth-oriented mindset, nurturing collaboration and networking, and offering substantial resources and support. These elements are indispensable for propelling innovation and expanding the horizons of what can be achieved.

4.3. The role of management support and work discretion

The result in indicate that EC significantly affects MS (β = 0.333; t = 7.118; P=.000), while MS has no significant effect on innovativeness (β = 0.053; t = 1.363; P=.173). However, the indirect effect of EC on innovativeness through MS is not significantly affecting innovativeness. Besides, shows that EC significantly affects WD (β = 0.452; t = 8.842; P=.000), while WD has also significant effect on the innovativeness (β = 0.116; t = 2.822; P=.005). However, the indirect effect of EC on innovativeness through WD is not significantly affecting innovativeness.

Management support is expected to entail a clear direction from the top of the organization that permeates throughout the organization to motivate, support, and reward innovation and entrepreneurial behavior. However, the result of the study shows that EC is not indirectly affecting innovativeness through management. This is because, the existing level of management support is not sufficiently enhancing innovativeness by taking lessons from the existing EC practices. However, EC is significantly enhancing the management support and innovativeness directly. The argument behind the insignificant indirect effect is the weakness in converting the benefits obtained from EC towards innovativeness by providing appropriate management support. It is therefore important to understand how management in education support innovation. Because, public sector organisations are known to be bureaucratic with standard rules and procedures, such organizations fail to identify innovation and lack a systematic method for producing, capturing, and executing creative ideas, according to Ernest and Young Global Limited (Citation2016). As pointed out by Kuratko and Audretsch (Citation2009), such behavior, which represents managerial support, includes supporting staff who offer ideas, supporting modest experimental ventures, and providing the resources necessary to engage in entrepreneurial activities. Whipple and Peterson (Citation2009), note that, institutionalizing the entrepreneurial activity within the organization’s systems and processes and providing knowledge are both examples of management assistance. According to Scheepers et al. (Citation2008), this form of managerial assistance encourages staff members to take on projects that are moderately hazardous and to solve problems in novel ways.

Conversely, studies in the past have shown that management support encourages entrepreneurial behavior, particularly the promotion of creative ideas (Bhardwaj et al., Citation2007). According to the findings of Kuratko et al. (Citation2014), management support for CE is directly related to the organization’s entrepreneurial outcomes, such as innovativeness. Without a doubt, each organization’s innovation vehicle is its support system for employees (Karyotakis & Moustakis, Citation2016). Still, the indirect effect of EC on innovativeness through management support is not ensured conditionally with different level of positions in the organizations. According to Whipple and Peterson (Citation2009), it is important for top level managers to also give inputs, get involved and encourage employees to take entrepreneurial actions. Besides encouragement, managers must be in a position to assist employees in dealing with the stigma associated with failure, as it discourages employees from trying something new. Failure should be seen as an integral part of innovation and corporate entrepreneurship.

Based on the aforementioned findings, it can be deduced that while management support plays a vital role in the relationship between EC and innovativeness, the current reality within the Department of Education contradicts this notion. Consequently, there arises a necessity to furnish enhanced management support that facilitates the advancement of EC towards innovativeness. This imperative can be achieved by establishing a framework within the organization that promotes and cultivates an EC, allocating resources to bolster innovation endeavours, eliminating impediments that may impede innovation, providing guidance and mentorship, as well as furnishing other forms of management support that foster a positive EC.

The existence of work discretion is expected to enhance willingness among employees to be more innovative. For instance, work discretion, or workplace autonomy, according to De Spiegelaere et al. (Citation2015), is a powerful indicator for exposing employees’ creative actions. The existence of organizational tolerance, however, will make this possible. In support of this, Kuratko and Hodgetts (Citation2007) state that it is crucial when fostering entrepreneurial orientation, such as innovativeness, to give employees the freedom to make their own decisions in their work processes without being overly micromanaged. They also advise against criticizing potential errors and mistakes made during entrepreneurial endeavours (Baskaran, Citation2021). However, the finding revealed that EC is not significantly indirectly affecting innovativeness through work discretion. The result also shows that work discretion has no effect on innovativeness, while EC has significant effect on WD. This indicates that, even though EC is enhancing work discretion innovativeness directly, the existing level of EC is not sufficiently enhancing the extent of work discretion towards innovativeness.

Studies have revealed a considerable relationship between job discretion and innovativeness (Baskaran, Citation2021). This is supported by Nguyen et al. (Citation2023) who claim that when given the freedom to decide and a choice in beginning and directing actions, employees feel inspired to perform in a creative manner. Bos-Nehles et al. (Citation2017) disagreed with this conclusion and claimed that giving employees the freedom to carry out their responsibilities while also allowing them to participate in decision-making can raise employee accountability, which may result in stress or overwork (Bos-Nehles et al., Citation2017). Their creativity thus suffer as a result (Nguyen et al., Citation2023). However, it is found that, surprisingly, work discretion is not significantly mediating the relationship between EC and innovativeness in the Department of Basic Education. This finding is different from previous studies findings because work discretion in the education sector is not enhancing the employee’s innovativeness. Even though EC is not indirectly effecting innovativeness through work discretion, the conditional effect shows a significant indirect influence of EC on innovativeness. That is, when organizational tolerance is high, EC affects innovativeness indirectly through the work discretion. This implies that the different elements of an EC have to be present for it (EC) to directly influence innovativeness. It has to be borne in mind that work discretion is one key element of EC.

This result is recorded because, work discretion practised in the department may be limited by the bureaucratic nature of the public sector. Besides, while work discretion can serve as a crucial element in the relationship between EC and innovativeness, it may not consistently function as a mediating factor. Specifically, the mediation of work discretion may be insufficient in fully capturing the intricacies of these influences and their collective impact on innovativeness. Additionally, the association between EC and innovativeness is susceptible to the influence of diverse contextual factors, among which work discretion holds significance. However, it is imperative to acknowledge that work discretion does not exist in isolation. Consequently, in comprehending the relationship between EC and innovativeness more comprehensively, it is imperative to consider the dynamic interplay of numerous factors, including but not limited to work discretion. Work discretion should be viewed not only as an inevitable but also a potentially highly beneficial feature of a bureaucratic organization (Du Gay & Pedersen, Citation2020). The authors suggest that discretion is an invaluable characteristic of senior managers and they describe it as ‘administrative statecraft’, and that the classic bureaucratic capacities are not located in opposition to the exercise of professional discretion. They point out that discretionary capabilities can inseparably be linked to the establishment of clear lines of command, delineated and well-defined distribution of responsibilities and obligations as well as a high degree of formalization and rule-based conduct in a state institution such as the Department of Education ().

Table 3. Estimates of total and indirect effects.

4.4. The conditional effect of job rank and organizational tolerance

Besides testing the direct and indirect effect of EC on innovativeness of employees, this study determines the moderating role of job rank and organizational tolerance.

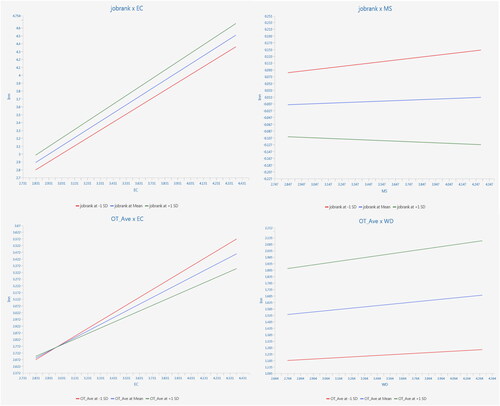

The finding of the study shows that the interaction of EC with organizational tolerance will significantly indirectly affects innovativeness (β=-.132; t = 2.151; p=.031). However, the interaction of EC and job rank has no significant effect on innovativeness (β=-.072; t = 1.175; p=.240). This result signifies that organizational tolerance plays a pivotal moderating role in the association between EC and innovativeness. Specifically, when an organization cultivates a culture of tolerance and encourages its employees to embark on new ideas, take risks, and learn from failures, it establishes a supportive EC and environment that fosters innovativeness. This supportive environment consequently enables employees to feel more at ease when expressing their entrepreneurial mindset and engaging in innovative behaviours. Organizational tolerance can effectively alleviate the fear of failure by creating a psychological safety net, where employees feel supported and encouraged even in the absence of successful innovative ideas. This, in turn, enhances their confidence to experiment and explore new opportunities. Additionally, in an environment characterized by high levels of tolerance, employees feel more comfortable sharing their creative ideas without the apprehension of being judged or facing negative consequences. This freedom to express and explore ideas can significantly contribute to a heightened level of innovativeness within the organization. Furthermore, when employees perceive their ideas and suggestions to be valued and supported, they are more inclined to engage in collaboration with others, exchange knowledge, and participate in collective problem-solving endeavours. This collaborative environment can substantially enhance the generation and implementation of innovative ideas ().

Table 4. Conditional indirect effects.

The finding in indicates that EC conditionally and significantly affects innovativeness with the change of employees’ positional level in the organization (β=.604; t = 14.339; p=.000). That is, the extent of influence of EC on innovativeness is dependent on the extent of organizational position level and organizational tolerance. An improvement in both organizational tolerance and organizational positional level will intensify the effect of EC on innovativeness. In this regard, the findings of Jaworski and Kohli (Citation1993) stated that organisational tolerance encourages successful development of innovative corporate entrepreneurial actions. This finding suggests that enhancements in both organizational tolerance and organizational job rank have the potential to significantly enhance the effect of EC on innovativeness in various ways. For instance, enhancements in organizational tolerance enhance the influence of EC on innovativeness by fostering a culture that values and actively supports entrepreneurial behaviours. Consequently, this cultivates motivation among employees to engage in more innovative practices and boosts their confidence in exploring novel opportunities. Moreover, when organizations empower individuals across various hierarchical levels, it grants them greater autonomy and authority to make decisions and contribute their innovative ideas. This empowerment facilitates the translation of employees’ entrepreneurial mindset into action, thereby driving innovation within the organization. Additionally, improvements in organizational positional level also enable organizations to become more agile and responsive to market fluctuations and customer demands. This agility, when combined with an EC and organizational tolerance, fosters an environment that consistently promotes innovation and adaptability. Thus, by concurrently enhancing organizational tolerance and organizational positional level, the effect of EC on innovativeness is heightened. This creates a culture that encourages risk-taking, empowers employees, embraces a wide range of diverse ideas, and nurtures agility. Collectively, these factors contribute to the establishment of a more innovative organization that can effectively leverage EC.

Table 5. Conditional direct effects.

Even though work discretion is not directly affecting the innovativeness, it is conditionally affecting the innovativeness with the change of organizational tolerance (β=.098; t = 2.388; p=.017), because, organizational tolerance demonstrate the management’s willingness to augment and develop exploration in enhancing EC towards innovation. Organizational tolerance, according to Van de Ven and Poole (Citation1995), is essential for any innovation that encourages an organization’s entrepreneurial initiative. In this context, Kriegesmann et al. (Citation2005) argued that organizations with a culture that discouraged risk-taking and creative activity would become incompetent at innovation. According to McGrath (Citation2011), managers need to be aware of the necessity of lowering employees’ fear of failure. Employees should experience failure earlier so that they can get as much knowledge as possible (McGrath, Citation2011). The results of this study indicate that the respondents are of the view that organizational tolerance in the Department of Education in KZN would support innovativeness by enhancing EC. This is because, organizational tolerance improves the extent of employees reaction to situational changes which plays a great role in enhancing entrepreneurial culture towards innovativeness. Thus, organizations that adopt and practice organizational tolerance will have an effective EC that build strong innovative behavior.

Work discretion and organizational tolerance play crucial roles in influencing the effect of entrepreneurial culture (EC) on innovativeness. Incorporating a substantial degree of task autonomy for employees, alongside an organization that exhibits a disposition of entrepreneurial tendencies, engenders a synergistic outcome. This union cultivates an innovation-oriented culture while simultaneously magnifying the impact of entrepreneurial cognition on the capacity for innovation. Furthermore, the convergence of task autonomy and organizational acceptance generates an atmosphere of psychological security within the organization. This psychological security further augment the degree of innovativeness. By nurturing these elements, organizations can unleash the full potential of entrepreneurial cognition and propel innovation to unprecedented levels.

Besides, the simple slopes of each interaction are provided in . The results indicates that only the interaction between organizational tolerance and EC significantly influences innovativeness. Other interactions show no significant effect on innovativeness.

5. Conclusion and implications

This research found that there is above average practices of innovativeness, entrepreneurial culture, management support, work discretion, and organizational tolerance in the department since the mean value of all the constructs is between 3.00 and 4.00 (on a 5 point Likert scale). The study shows EC significantly affect innovativeness, management support, and work discretion. Therefore, the department has to establish and develop strong EC in order to improve the extent of innovativeness among employees. Further, even though work discretion does not mediate the relationship between EC and innovativeness, (conditionally depending on organizational tolerance), EC indirectly affect innovativeness through work discretion. Thus, it’s suggested that the management of the Department of Education should provide more freedom to the employees and tolerate their failures. This will enable employees to work more autonomously, which will lead to better innovativeness.

Regarding the future research direction, first, the studies on entrepreneurship and innovation in the public sector particularly in developing countries are scarce. Thus, future researchers has to give focus on the subject of entrepreneurship and innovation in the public sectors of developing countries. Second, this study focuses only on the Department of Educations among the public sectors, which might be difficult to generalize the findings for the public sector. Therefore, it is recommended that future researchers study the subject in different public sectors. Besides, it is more important to compare the public and private sectors when examining the relationship between EC and innovativeness. Verhoest et al. (Citation2007) discovered that political pressures brought on by challenges to an organization’s perceived legitimacy had an impact on public managers’ innovative conduct. However, despite the fact that these studies demonstrate how institutional conditions encourage bureaucrats to innovate, they provide little detail regarding how innovative behavior evolves (Wynen et al., Citation2020). Thus, it’s crucial for future researchers to test both institutional and external factors that relate with workers innovativeness.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Michael Msawenkosi Thabethe

Michael Msawenkosi Thabethe is a chief education specialist in the Department of Education, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. His research interests are in curriculum development and entrepreneurship.

Abdela Kosa Chebo

Abdela Kosa Chebo is currently an assistant professor at the Kotebe University of Education, Ethiopia and a visiting scholar at the University of Johannesburg, South Africa. Abdella is also serving as an academic vice president of Sheger College, Ethiopia. His research interest is in strategic management, entrepreneurship, and small firm growth.

Shepherd Dhliwayo

Shepherd Dhliwayo is a professor at the University of Johannesburg. He researches in the field of strategy, entrepreneurship, and small business development.

References

- Ahmetoglu, G., Akhtar, R., Tsivrikos, D., & Chamorro-Premuzic, T. (2018). The entrepreneurial organization: The effects of organizational culture on innovation output. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 70(4), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1037/cpb0000121

- Ahmed, R. R., Romeika, G., Kauliene, R., Streimikis, J., & Dapkus, R. (2020). ES-QUAL Model and customer satisfaction in online Banking: Evidence from multivariate analysis techniques. Oeconomia Copernicana, 11(1), 59–93. https://doi.org/10.24136/00/2020.003

- Alvarez, S., & Busenitz, L. (2001). The entrepreneurship of resource-based theory. Journal of Management, 27(6), 755–775. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920630102700609

- Alwis, G., & Senathiraja, R. (2005). The entrepreneurial culture value patterns and business practices of small and medium enterprises in Sri Lanka based on selected case studies. Journal of Management, 3(1), 20–25.

- Aragón-Sánchez, A., Baixauli-Soler, S., & Carrasco-Hernandez, A. J. (2017). A missing link: The behavioral mediators between resources and entrepreneurial intentions. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 23(5), 752–768. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-06-2016-0172

- Audretsch, D. B., & Belitski, M. (2017). Entrepreneurial ecosystems in cities: Establishing the framework conditions. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 42(5), 1030–1051. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-016-9473-8

- Babbie, E. (2004). Laud Humphreys and research ethics. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 24(3/4/5), 12–19. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443330410790849

- Baskaran, S. (2021). The role of work discretion in activating entrepreneurial orientation among employees. Journal of Entrepreneurship and Business, 5(2), 11–24. https://doi.org/10.17687/jeb.v5i2.115

- Bau, F., & Wagner, K. (2015). Measuring corporate entrepreneurship culture. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 25(2), 231–244. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJESB.2015.069287

- Bhardwaj, A., Dietz, J., & Beamish, P. W. (2007). Host country cultural influences on foreign direct investment. Management International Review, 47(1), 29–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-007-0003-7

- Bos-Nehles, A., Renkema, M., & Janssen, M. (2017). HRM and innovative work behaviour: A systematic literature review. Personnel Review, 46(7), 1228–1253. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-09-2016-0257

- Cameron, K., & Quinn, R. (1999). Diagnosing and changing organizational culture: Based on the competing values framework. Addison-Wesley.

- Carnes, C., & Ireland, R. (2013). Familiness and innovation: Resource bundling as the missing link. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 37(6), 1399–1419. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12073

- Chebo, A. K., & Kute, I. M. (2018). Uncovering the unseen passion: A fire to foster ambition toward innovation. World Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development, 14(2), 126–137. https://doi.org/10.1108/WJEMSD-03-2017-0013

- Cooper, D. R., & Schindler, P. S. (2008). Business research methods (10th ed.). Mcgraw-hill.

- Danish, R. Q., Asghar, J., Ahmad, Z., & Ali, H. F. (2019). Factors affecting “entrepreneurial culture”: The mediating role of creativity. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 8(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13731-019-0108-9

- De Jong, J., & Den Hartog, D. (2010). Measuring innovative work behaviour. Creativity and Innovation Management, 19(1), 23–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8691.2010.00547.x

- De Spiegelaere, S., Van Gyes, G., De Witte, H., Niesen, W., & Van Hootegem, G. (2015). Job design, work engagement and innovative work behavior: A multi-level study on Karasek’s learning hypothesis. Management Revu, 26(2), 123–137. https://doi.org/10.5771/0935-9915-2015-2-123

- Dhliwayo, S. (2017). Public sector entrepreneurship. A conceptual operational construct. The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 18(3), 153–163. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465750317709708

- Du Gay, P., & Pedersen, K. Z. (2020). Discretion and bureaucracy. In T. Evans & P. Hupe (Eds.), Discretion and the quest for controlled freedom (pp. 221–236). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-19566-3_15

- Endenich, C., Lachmann, M., Schachel, H., & Zajkowska, J. (2023). The relationship between management control systems and innovativeness in start-ups: Evidence for product, business model, and ambidextrous innovation. Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change, 19(5), 706–734. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAOC-06-2022-0087

- Ernest and Young Global Limited. (2016). Transparency Report 2016 South Africa. https://assets.ey.com/content/dam/ey-sites/ey-com/en_za/article/ey-tr-south-africa-2016.pdf

- Escrig-Tena, A. B., Segarra-Ciprés, M., García-Juan, B., & Badoiu, G. A. (2022). Examining the relationship between work conditions and entrepreneurial behavior of employees: Does employee well-being matter? Journal of Management & Organization, 2022, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2022.9

- Evans, T. (2020). Discretion and professional work. In T. Evans & P. Hupe (Eds.), Discretion and the quest for controlled freedom (pp. 357–375). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Evstigneev, I. V., Schenk-Hoppé, K. R., & Ziemba, W. T. (2013). Introduction: Behavioral and evolutionary finance. Annals of Finance, 9(2), 115–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10436-013-0229-2

- Ezeh, P. C., & Abdulrahman, R. M. (2022). The effect of innovativeness and internal locus of control on agro-entrepreneurial intention: A mediating role of innovativeness. International Journal of Management & Entrepreneurship Research, 4(9), 372–384. https://doi.org/10.51594/ijmer.v4i9.365

- Gjorevska, E. (2023). Entrepreneurial culture as threat to SMEs’ entrepreneurial orientation-success relationship in developing countries – The case of private healthcare sector in Macedonia. Journal of Economics and Public Finance, 9(3), p39. https://doi.org/10.22158/jepf.v9n3p39

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Holt, D. T., Rutherford, M. W., & Clohessy, G. R. (2007). Corporate entrepreneurship: An empirical look at individual characteristics, context, and process. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 13(4), 40–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/10717919070130040701

- Hoogstraaten, M. J., Frenken, K., & Boon, W. (2023). Mixing and matching institutions: On institutional hybridization processes in innovation and transition studies [PhD diss., University Utrecht]. Utrecht University Repository. https://dspace.library.uu.nl/handle/1874/427222

- Hornsby, S., Kuratko, D. F., & Zahra, S. A. (2002). Middle managers’ perception of the internal environment for corporate entrepreneurship: Assessing a measure scale. Journal of Business Venturing, 17(3), 253–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(00)00059-8

- Ireland, R. D., & Webb, J. W. (2007). Strategic entrepreneurship: Creating competitive advantage through streams of innovation. Business Horizons, 50(1), 49–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2006.06.002

- Ireland, R. D., Covin, J. G., & Kuratko, D. F. (2009). Conceptualizing corporate entrepreneurship strategy. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(1), 19–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2008.00279.x

- Jankelová, N. (2022). Entrepreneurial orientation, trust, job autonomy and team connectivity: Implications for organizational innovativeness. Engineering Economics, 33(3), 264–274. https://doi.org/10.5755/j01.ee.33.3.28269

- Janssen, O. (2005). The joint impact of perceived influence and supervisor supportiveness on employee innovative behaviour. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 78(4), 573–579. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317905X25823

- Jaworski, B., & Kohli, A. K. (1993). Market orientation: Antecedents and consequences. Journal of Marketing, 57(3), 53–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299305700304

- Joseph, C., & Wood, D. (2020). Fostering innovation via ambidexterity in aerospace organizations. Acta Astronautica, 168, 37–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actaastro.2019.10.014

- Karyotakis, K. M., & Moustakis, V. S. (2016). Organizational factors, organizational culture, job satisfaction and entrepreneurial orientation in public administration. The European Journal of Applied Economics, 13(1), 47–59. https://doi.org/10.5937/ejae13-10781

- Khan, S. (2021). Exploring the firm’s influential determinants pertinent to workplace innovation. Problems and Perspectives in Management 19(1), 272–280. https://doi.org/10.21511/ppm.19(1).2021.23

- Kosa, A., Mohammad, I., & Ajibie, D. (2018). Entrepreneurial orientation and venture performance in Ethiopia: The moderating role of business sector and enterprise location. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 8(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-018-0110-x

- Kriegesmann, B., Kley, T., & Schwering, M. G. (2005). Creative errors and heroic failures: Capturing their innovative pontential. Journal of Business Strategy, 26(3), 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1108/02756660510597119

- Kuratko, D. F., & Hodgetts, R. M. (2007). Entrepreneurship: Theory, process, practice (7th ed.). Thomson/SouthWestern Publishing.

- Kuratko, D. F., Ireland, R. D., Covin, J. G., & Hornsby, J. S. (2005). A model of middle level managers’ entrepreneurial behavior. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(6), 699–716. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2005.00104.x

- Kuratko, D. F., & Audretsch, D. B. (2009). Strategic entrepreneurship: Exploring different perspectives of an emerging concept. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2008.00278.x

- Kuratko, D., F., Hornsby, J. S., & Covin, J. G. (2014). Diagnosing a firm’s internal environment for corporate entrepreneurship. Business Horizons, 57(1), 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2013.08.009

- KwaZulu Natal Department of Education. The annual performance plan 2021/22. https://www.kzneducation.gov.za/images/documents/AnnualPerformancePlans/KZNDOE_APP_2021-22_Online_version.pdf.

- Laforet, S. (2016). Effects of organizational culture on organizational innovation performance in family firms. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 23(2), 379–407. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-02-2015-0020

- Leal-Rodríguez, A. L., Albort-Morant, G., & Martelo-Landroguez, S. (2016). Links between entrepreneurial culture, innovation, and performance: The moderating role of family firms. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 13(3), 819–835. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-016-0426-3

- Li, W., Li, D., Li, C., Feng, H., & Wang, S. (2023). Incremental innovation, government subsidies, and new venture growth. Journal of Global Information Management, 31(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.4018/JGIM.320818

- Liu, Y., Wang, W., & Chen, D. (2019). Linking ambidextrous organizational culture to innovative behavior: A moderated mediation model of psychological empowerment and transformational leadership. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2192. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02192

- Liu, N., & Zhou, G. (2022). Analysis of collaborative innovation behavior of megaproject participants under the reward and punishment mechanism. International Journal of Strategic Property Management, 26(3), 241–257. https://doi.org/10.3846/ijsqm.2022.17151

- Malan, J. H. (2016). An assessment of the impact of entrepreneurial orientation on the success of selected public secondary schools [Doctoral dissertation, North-west University]. https://repository.nwu.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10394/25524/Malan_JH_2016.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Marra, P. R., & Meng, W. (2023). Role played by innovativeness of biotechnology firms in firm growth: Identifying the moderating roles of top management support and team innovation orientation. Journal of Commercial Biotechnology 27(4), 238–249. https://doi.org/10.5912/jcb1525

- Martinsuo, M., Hensman, N., Artto, K., Kujala, J., & Jaafari, A. (2006). Project-based management as an organizational innovation: Drivers, changes, and benefits of adopting project-based management. Project Management Journal, 37(3), 87–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/875697280603700309

- McGrath, R. G. (2011). Failing by design. Harvard Business Review, 89(4), 76–83, 137.

- McMurray, A., de Waal, G. A., Scott, D., & Donovan, J. D. (2021). The relationship between corporate entrepreneurship climate and innovativeness: A national study. In A. McMurray, N. Muenjohn, & C. Weerakoon (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of workplace innovation (pp. 101–121). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Morris, M. H., & Jones, F. F. (1999). Entrepreneurship in established organizations: The case of the public sector. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 24(1), 71–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879902400105

- Morris, M. H., Kuratko, D. F., & Covin, J. G. (2008). Corporate entrepreneurship & innovation (2nd ed.). Thomson South Western.

- Morris, M. H., Kuratko, D. F., & Covin, J. G. (2011). Corporate entrepreneurship & innovation. (3rd ed.). South Western Cengage.