?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Destructive leadership behaviors and their effects on the organization have received little attention in terms of research & theory development. As a result, the purpose of this article is to investigate the prevalence and determinants of destructive leadership behavior from the quantitative data collected through questionnaire. A total of 947 sample employees were included in this study stratified sampling technique. Personal behavior, ineffective decision, management incompetency, and political behavior have a positive significance difference at p = 0.01 after the data has been analyzed through factor analysis and regression analysis. However, at the 1% significance level, the difference in political behavior and negotiation problem is negative. On the other hand, poor communication has a negative relationship with destructive leadership behavior, but it is statistically insignificant at a 5% alpha level. According to the findings, ∼65% of public-sector employees in the Awi zone are susceptible to destructive leadership. In this case, the researchers recommended that organizations intentionally and consistently need to promote an environment in which employees feel free to speak up about leaders’ behavior that they believe it violates not only their own but also the organization’s values.

IMPACT statement

For the success of any organization, good leaders are needed; but a mere focus on those good leadership traits is not enough to get the organization more effective and efficient. So, this study is intended to show the prevalence of destructive eadership and contributing factors in target public organizations. It is founded that Leaders may behave destructively for a variety of reasons, be it their personality, incompetence, inability to negotiate, perceived injustice or threat to their identity, ineffective decision-making, financial reasons, low organizational identification, Political behavior etc.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

Most academicians, organizations, and managers have traditionally sought to improve organizational performance through the study of good, effective, visionary, and charismatic leadership, according to Burke et al. (Citation2006). Understanding and avoiding destructive leadership, on the other hand, may be just as important, if not more so, than understanding and improving positive aspects of leadership (Ashforth, Citation1987).

Several authors and academics have recently called for a more in-depth examination of the characteristics and outcomes associated with such destructive leadership behavior by exploring it as a ‘dark side’ of leadership to contribute to a better understanding of leadership effectiveness and development (Einarsen et al., Citation2010). Those researchers and scholars clearly support the idea that destructive leadership is widespread in the workplace and is not limited to the absence of effective leadership behavior (Kelloway et al., Citation2006).

Different researchers have proposed several concepts that arguably fall within the domain of destructive leadership that is directed at subordinates, such as ‘abusive supervisors’ (Hornstein, Citation2016; Tepper, Citation2000), ‘health endangering leaders’ (Kile, Citation1990) as cited in the works of Tran et al. (Citation2014), ‘petty tyrants’ (Ashforth, Citation1987), ‘bullies’ (Brodsky, Citation1976).

According to Tran et al. (Citation2014), destructive leadership is defined as a leader’s, supervisor’s, or manager’s systematic and repeated behavior that undermines and/or sabotages the organization’s goals, tasks, resources, and effectiveness, as well as the motivation, well-being, or job satisfaction of subordinates. Destructive leaders may make repeated errors and/or act aggressively toward subordinates through sabotage, theft, and corruption (Kelloway et al., Citation2006).

Therefore, a focus that is just on a leader’s aggressive behavior (Hubert and van Veldhoven, 2001; or abusive supervision alone) or a focus that is overly narrowed (Tepper, Citation2007) may only provide a partial view of the multifaceted phenomena of destructive leadership. Destructive leadership is not something that exists apart from constructive leadership but is an integrated part of the behavioral toolbox of leaders, as evidenced by the moderate correlations that exist between the various forms of destructive leadership behavior and constructive leadership behavior.

An English research on manager harassment led to a similar outcome. Of the 72 supervisors rated by subordinates, only 11.1% were exclusively viewed as ‘tough managers’, whereas 9.7% of the managers were only viewed as ‘angels’. About 28% of the managers in the same survey were classified as ‘tough managers with supporters’, ‘middle’s with victims’, or ‘angels with victims’.

Consequently, leaders exhibit both destructive and constructive behavior, using a variety of behaviors and behavior combinations in response to various subordinates, each of whom may respond in a variety of ways. This has ramifications for leadership research, which in the past has mostly seen leadership as either being constructive or destructive, with the latter being an outlier. According to Duffy et al. (Citation2002) and Major et al., experiencing both constructive and destructive behavior from the same source may have more disturbing consequences on the target than only being exposed to destructive behavior.

Given the diversity of notions used to define destructive leaders, it is obvious that this form of leadership encompasses a variety of behaviors rather than just one type. The present study makes use of the broad concept of ‘destructive leadership’, which is defined as ‘systematic and repeated behavior by a leader, supervisor, or manager that violates the legitimate interest of the organization by undermining and/or sabotaging the organization’s goals, tasks, resources, and effectiveness and/or the motivation, well-being, or job satisfaction of subordinates’ (Einarsen et al., Citation2007, p. 208).

There are two main reasons for the growing interest in the dark side of leadership: First, there is the question of the prevalence of and costs as a result of destructive leaders. While Aryee et al. (Citation2004) consider abusive supervision, as the one concept that has dominated empirical research in this area, as a ‘low base rate phenomenon’ (p. 394), other studies report a strong prevalence of destructive leader behaviors in organizations. This case is similar to the context of Ethiopia.

The second reason for the interest in destructive leader behaviors stems from the findings that their effects on individual followers are quite severe. A large variety of outcomes have been studied in relation to destructive leadership behaviors. Examples include effects on job tension and emotional exhaustion (e.g. Martinko et al., Citation2007), resistance behavior (e.g. Bamberger & Bacharach, Citation2006), deviant work behavior (e.g. Zellars et al., Citation2002), reduced family well-being (e.g. Hoobler & Brass, Citation2006), and intention to quit and job satisfaction (e.g. Tepper, Citation2000). Both prevalence rates and potential serious effects of destructive leader behaviors make it a concept worthwhile of investigations.

Leadership researchers like Einarsen et al. (Citation2007), Bass et al. (Citation2003), and Birkland et al. (2008) argued that the extent to which destructive leadership prevail have relationship with the cultural and societal factors. Based on their argument, this study tries to investigate the prevalence of destructive leadership behaviour in the target area. As a result, this is the first empirical research paradigm to investigate the prevalence and content of destructive leadership in Awi work culture. Additionally, several academics have concentrated on the contribution of constructive (good) leaders to organizational performance, such as Ayalew et al. (Citation2018), Dea and Tekalign (Citation2022), and Mengistu and Lituchy (Citation2017). It appears that dealing with the positive side of leadership is the greatest way to succeed, particularly in the Ethiopian environment. The flip side of good leadership (i.e. destructive leadership) is missed.

University held a workshop for leaders titled ‘improving leadership competence’ (2019). When a series of questions were given out and scores were tallied, the majority of the participants in this training described themselves as democratic, but when a series of questions were given out and scores were tallied, their leadership style fell into the autocratic group. As a result of this disparity, the researchers came to the conclusion that even leaders are unaware of their own actions and that they may engage in destructive leadership behavior toward their subordinates.

Therefore, the objectives of this study were to:

Look into the prevalence of destructive leadership behavior in Awi zone.

Identify the destructive leadership behaviors that happened most frequently in the study area’s organizations.

Identify the most significant factors influencing the extent of destructiveness in organizational leadership in the research area.

2. Review of related literatures

McCleskey (Citation2013), leadership is an essential feature of human relations. He noted that the large number of studies on leadership is a testament to the importance of organizational research and the fundamental role it plays in human relations and interactions. While it is easier to downplay constructive leadership amidst the growing research trend of destructive leadership, scholars have begun to realize that most leaders display a combination of constructive and destructive behaviors during the leadership cycle (Skogstad et al., Citation2014). Pynnonen and Takala (Citation2013) used content and interpretive discourse analyzes to seek the core of good leadership, recognize the implicit existence of destructive leadership, and find improvements for effective leadership and governance. They noted that leadership consisted of partly overlapping elements in the ecology that included the leader, the follower, and the context (Pynnonen & Takala, Citation2013). Pynnonen and Takala’s study showed the dominating discourse was that a good leader was beyond the reach of ordinary people, a ‘superior human being’ (p. 14). Einarsen et al. (Citation2007) offered a typology of destructive leadership within an organizational context, which emphasized that most leaders did not fall on either one or the other side of the continuum as completely bad or good. Instead, leaders engaged in a mix of destructive and constructive behaviors influenced by workplace factors that encouraged productive and counterproductive behaviors. Therefore, destructive leadership is contextual in nature, as a non-static, dynamic, and socially constructed phenomenon that lies on a spectrum of constructive-destructive leadership behaviors (Krasikova et al., Citation2013). A leader who is initially constructive and begins the leadership cycle with basic skills to lead a complex organization may evolve through time to become a far different leader. Einarsen et al. (Citation2007) suggested that a leader who performs destructively on one dimension might not do so on another when the leader can compensate with corresponding constructive attributes. For example, derailment may occur during a leadership role occupancy, which may warrant the leader to change supervisory tactics over time. Alternatively, a contention could be made that it takes a combination of dysfunctional attributes lying on a spectrum to cause destructive leadership; the reverse, however, is not true. Destructive leadership prima facie does not cause dysfunctional attributes (Avolio & Walumbwa, Citation2014).

In a systematic review of recent leadership literature, Schilling and Schyns (Citation2014) gleaned theories from several studies to obtain a deeper understanding of the negative types of leadership. The analysts’ acknowledgement of the multiple ways that charismatic leadership could deteriorate if leaders abused their allure was of interest. For example, poor organizational outcomes can occur when charismatic leaders place their own needs ahead of the legitimate needs of their subordinates or the organization. Schilling and Schyns (Citation2014) results supported the complicated assumption that although destructive leadership was bad, and that ‘bad is stronger than good’ (p. 188), scientists must be cautious to avoid sweeping conclusions about the harmfulness of destructive leadership, or the usefulness of constructive leadership. Understanding the dynamics and contexts in which destructive leadership occurs requires exploration of the cognitive and implicit biases that propel the emergence of this destructive phenomenon. Burke and Page (Citation2017) suggested that a firm’s behavioral description of the actions of a destructive leader was a good start and argued that destructive leadership was not conducive to sustainable leadership. This important revelation was another factor that drove the rationale for the current project.

Multiple researchers of destructive leadership have focused on the negative effects on followers (Aasland et al., Citation2010; Nyberg et al., Citation2011; Tavanti, Citation2011). However, organizational scientists overall disagree on the prevalence of destructive leadership. For example, some analysts reported that destructive leadership was quite rare (Vogel et al., Citation2015), while others believed it was rampant within organizations (Antoniou et al., Citation2016; Meuser et al., Citation2016). Despite this ambiguity, dysfunctional leadership may be a bigger setback than many organizational scientists believe (Aasland et al., Citation2010; Tavanti, Citation2011). Aasland et al. (Citation2010) concluded that destructive leadership behavior was not a rare or unique phenomenon, but a typical experience during the working cycle of subordinates. Schyns and Schilling (Citation2014) concurred, reporting an estimated 13.6% prevalence rate for U.S. workers affected by abusive supervision in their study. These examiners also acknowledged that the results of their meta-analysis indicated a high correlation between destructive leadership and 34 counterproductive work behavior, also known as the dark side of performance. Namie and Namie (Citation2000) reported that ∼10–16% of employees have experienced abusive supervision, a subset of destructive leadership. In response to conflicting research on the prevalence of destructive leadership, Aasland et al. (Citation2010) investigated the prevalence of four forms of destructive leadership, including tyrannical, derailed, supportive-disloyal, and laissez-faire. Aasland et al. gathered questionnaire data on leadership behaviors of respondents’ superiors and respondents’ exposure to bullying behaviors, job satisfaction, health complaints, and psychosocial aspects of their work environments. The findings of Aasland et al.’s team indicated that almost 33% of employees reported experiencing destructive leadership on a frequent basis. Overall, analysis of survey data indicated that destructive leadership behaviors were commonplace. A nationwide workforce survey revealed that up to 67% of employee participants were disengaged because of bad management and destructive leadership practices (Gallup, Citation2017).

The purpose of this study is to identify the prevalence of destructive leadership in the Awi zone of North West Ethiopia, to contribute by demonstrating that such behavior is prevalent, and to provide a roadmap for organizational researchers to explore the causes of and/or the extent to which such leadership behavior may have an impact on organizational performance.

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Research approach and design

Because the data was collected through a questionnaire, a quantitative research approach was used in this study. Also, to describe the leadership behavior in the study area, the research design was descriptive, regression, and factor analysis.

3.2. Population and sampling procedure

The participants in this study were all employees of public organizations in Awi Zone, including all woredas and town administrations.

There were a total of 28,663 government workers, according to the Awi Zone Administration Human Resource Development Office (Citation2020). The researcher chose 1069 samples from this entire target population using Yamane’s formula, as shown below. Finally, depending on their woreda, stratified sampling procedures were employed to calculate the sample size (), and convenience sampling was utilized to choose samples from each woreda.

Table 1. Sample size determination.

At a confidence level of 97% and a precision level of 0.03, the sample size was estimated using the (Yamane, Citation1967) sample size determination formula as follows:

Where: n is the sample size

N is the population sizee is the level of precision.

The overall sample size was 1069 as a result of the above calculation. Finally, according to their proportion, a structured questionnaire has been developed and distributed to employees in each woreda.

3.3. Data collection methods

Primary and secondary data sources were used by the researcher. The respondents’ primary data was collected using a structured questionnaire which is adapted from Erickson et al. (Citation2015). The Likert Scale was used as the measurement method, which consists of statements in which respondents rate their level of agreement or disagreement on a five-point scale. 0 = Do not engage in this behavior, 1 = Very Infrequently Engage, 2 = Occasionally Engage, 3 = Frequently Engage, and 4 = Very Frequently Engaged, where 0 = Do not engage in this behavior, 1 = Very Infrequently Engage, 2 = Occasionally Engage, 3 = Frequently Engaged, and 4 = Very Frequently Engaged. Secondary data was gathered from books, journals, articles, and reports to supplement the primary data.

3.4. Reliability and validity

The issue of measure consistency is at the heart of reliability (Patton, Citation2002). It was considered and tested in this study using SPSS software and Cronbach’s alpha method. A score of 0.7 or higher indicates an acceptable level of internal consistency (Nunnally & Bernstein, Citation1994) as cited by Saleem et al. (Citation2021). In this regard, the Cronbach’s Alpha value for this study is 0.73, indicating that the items representing destructive leadership behavior have a high level of overall internal consistency.

‘Validity is about how well a test does the job it is employed to do’, according to Cureton. This statement denotes that the term validity refers to the extent to which any measuring instrument measures what it is designed to measure. This study had tested its face (content) validity in this regard. The questionnaires for 50 respondents were pre-tested before being administered to avoid ambiguity, confusion, and poorly prepared items.

3.5. Data analysis

As a result, 947 cases out of a total of 1069 were processed in this study. Due to missing values, the remaining cases were excluded from the analysis (list-wise exclusion of cases).

Using SPSS software version 20 and frequency distribution tables, descriptive analysis was used to describe the characteristics of destructive leadership behavior. The technique of principal component analysis (PCA) was also used because it is a useful multivariate technique of analysis in the variable reduction procedure (i.e. when we have data on a large number of redundant variables) (Jolliffe, Citation2002). Then, using regression analysis, it was possible to predict how subordinates felt about their bosses, as measured by an overall good-bad scale. Importantly, the PCs are thus used as input variables for the upcoming regression analysis, which will be used to further analyze the data.

In general, the model can be represented as:

(1)

(1)

Where ;

= the component loading which represents the

PC and the

Constraint; and

= the k variables or factors.

3.6. Ethical considerations

To protect the research subjects, the researcher noticed ethical concerns. Before respondents consented to engage in the study, the researcher sorts their informed consent. The researcher also informs them that they have the only right to leave the study at any point during the data gathering process. Furthermore, the researcher guaranteed respondents of confidentiality and anonymity, as well as the fact that the information gathered was solely for academic purposes and would not be shared with anyone else.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Results of descriptive statistics

According to the table (), 12.9% of respondents confirm that their leaders do not engage in destructive leadership behavior, 22% of the time leaders engage in destructive leadership behavior very infrequently, 27.2% occasionally engage, 21.3% frequently engage, and 16.6% of the time leaders engage in destructive leadership behavior very frequently. As a result, it can be concluded that employees are exposed to destructive leadership behavior in the workplace 65% of the time.

Table 2. Frequency of destructive leadership behavior through multiple response method.

The Destructive Leadership Questionnaire (DLQ) is one of several surveys that ask subordinate employees to identify specific destructive behaviors that a leader exhibits to identify dysfunctional or toxic leadership. The short version of the DLQ lists 22 discrete behaviors that are frequently cited as characteristics of destructive leaders, and employees rate the frequency with which they engage in these behaviors (Do It) or have seen others engage in them (Seen It), with 0 indicating that you do not engage in this behavior, 1 indicating that you engage in this behavior very infrequently, 2 indicating that you engage in this behavior Occasionally, 3 indicating that you engage in this behavior Frequently, and 4 indicating that you engage in this behavior very Frequently.

The more destructive the leader is, the higher the score (>2). As shown in , all leaders in the Awi Zone exhibit destructive leadership, with the exception of those elements of Micro-Manage and Over-Control [mean score 1.9366 (SD = 1.20876)], Tell People Only What They Wanted to Hear [mean score 1.9609 (SD = 1.30520)], Lie or Engage in Other Unethical Behaviors [mean score 1.9609 (SD = 1.3095)], and unwillingness to change their mind [mean score 1.9683 (SD = 1.27798)].

Table 3. Descriptive results of destructive leadership behavior.

4.2. Results of multivariate analysis

4.2.1. Component factor analysis

When we use multiple measures to overcome measurement error by multivariable measurement, factor analysis is an interdependence technique whose primary purpose is to define the underlying structure among the variables in the analysis; and the researchers even strive for correlation among the variables.

As the variables become more correlated, the researcher will need to find new ways to manage them, such as grouping highly correlated variables together, labeling or naming the groups, and possibly even developing a new composite measure to represent each group of variables and test hypotheses about which variables should be grouped together on a factor or the exact number of factors (Yekkalam et al., Citation2019).

The goal of factor analytic techniques is to find a way to condense (summarize) the information contained in a large number of original variables into a smaller number of new, composite dimensions or variates (factors) with the least amount of information loss—in other words, to find and define the fundamental constructs or dimensions assumed to underpin the original variables (Kim & Mueller, Citation1978).

The only time high correlations aren’t indicative of a bad correlation matrix is when two variables are highly correlated and have significantly higher loadings on that factor than other variables. Then their partial correlation may be high because the other variables don’t explain them very well, but they do explain each other. This is also to be expected when a factor only has two highly loaded variables. A high partial correlation is one that has both practical and statistical significance, and partial correlations above 0.7 are considered high.

Another way to see if factor analysis is appropriate is to look at the entire correlation matrix. One such measure is the statistical test for the presence of correlations among variables. It indicates that at least some of the variables in the correlation matrix have statistically significant correlations.

The measure of sampling adequacy is a third way to quantify the degree of inter-correlations among variables and the appropriateness of factor analysis (MSA). This index ranges from 0 to 1, with 1 indicating that each variable is perfectly predicted by the other variables with no errors. The following guidelines can be used to interpret the measure: Meritorious is a score of 0.80 or higher; middling is a score of 0.70; mediocre is a score of 0.60; miserable is a score of 0.50; and unacceptable is a score of 0.50 or lower (Nkansah, Citation2011). Before proceeding with the factor analysis, the researcher should always have an overall MSA value of at least 0.50. If the MSA value falls below 0.50, the variable-specific MSA values can be used to identify variables that should be deleted to achieve a 0.50 overall value. However, KMO is 0.785 in this study, and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity (Bartlett, Citation1951) is significant (<0.05).

The loading coefficients for the items unable to deal with new technology and change, act insularly, tell people only what they want to hear, exhibit inconsistent, erratic behavior, and act in a brutal or bullying manner are all <0.4 in principal component analysis. As a result, the researcher removed these items from the list with lower loading and ran the analysis again, finding that the six factors had better explanatory power ().

Table 4. Measure of sampling adequacy result and pattern matrix.

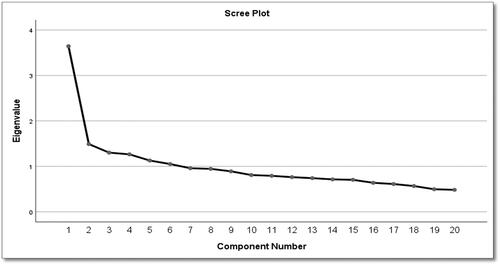

As shown in , all of the remaining 17 items are condensed into six factors with Eigen values >1.

Examining the eigenvalues associated with the factors can help you decide how many to extract to represent the data (see ). The first six factors will be rotated based on the criterion of retaining only factors with eigenvalues of 1 or greater. These six factors account for 18.59, 8.36, 7.75, 6.90, 6.46, and 5.94%, respectively, of the total variance. This means that these six factors account for nearly 54% of the total variance. The remaining variables combine to account for only about 46% of the variation. As a result, a six-factor model may be sufficient to represent the data.

Table 5. Total variance in principal component analysis under Eigen value.

Component Factor Analysis is critical when variables become correlated, as explained in the previous section of this paper, to group highly correlated variables together, labeling or naming the groups. Those highly correlated variables were grouped () and labeled in the following way based on the Eigen value result:

Table 6. Pattern matrix under Eigen value.

Item saying Act Inappropriately in Interpersonal Situations; Ineffective at co-coordinating & managing; Lie or Engage in Other Unethical Behaviors; Engage in Behaviors That Reduced Their Credibility and Unwilling to Change Their Mind were labeled as Personal behavior. Item saying Unclear about Expectations; Unable to Develop and Motivate Subordinates; Micro-Manage and Over-Control, and fail to seek appropriate information were labeled as management incompetency. Items saying communicate ineffectively, and make decisions without adequate information were labeled as poor communication. Items saying ineffective in negotiation, and Play Favorites were labeled as poor in negotiation. Items saying unable to understand a long term view, and Exhibit a Lack of Skills to Do Their Job were labeled as ineffective in decision. Items saying unable to make an appropriate decision, and unable to prioritize and delegate were labeled as political behavior.

The six factors are not strongly correlated (all coefficients are <0.20), so the varimax (orthogonal) matrix should be interpreted. If the oblimin rotated matrix is to be interpreted, the Pattern Matrix or the Structure Matrix must be interpreted as well. The correlations between variables and factors are shown in the structure matrix, but these can be muddled by factor correlations (). The pattern matrix is a tool for interpreting factors that shows uncontaminated correlations between variables and factors.

Table 7. Component correlation matrix under Eigen value.

4.2.2. Multiple regression analysis

4.2.2.1. Assumptions of linear regressions

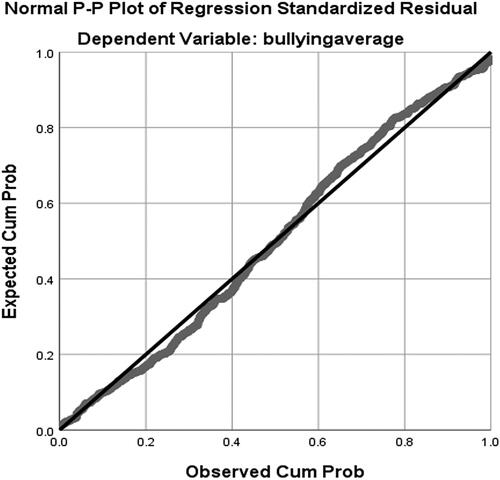

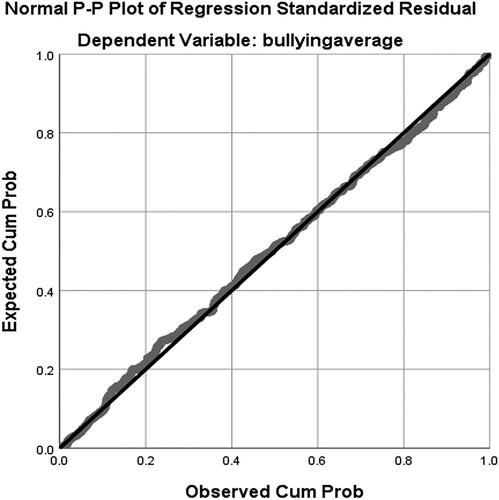

Let’s start with the normality. The residuals of your regression should follow a normal distribution to make valid inferences from it. We can tell if the residuals are normally distributed by looking at a normal Predicted Probability (P-P) plot. If they are, the diagonal normality line, as shown in the plot below, will be followed. The little circles will not follow the normality line if your data is not normal.

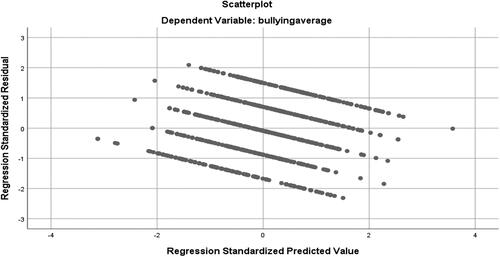

Homo-scedasticity refers to whether the residuals are evenly distributed, or if they tend to cluster at some values while spreading widely at others. If your data looks like a shotgun blast of randomly distributed data, it’s homo-scedasticity. In the output (), the residuals scatter-plot will appear just below the normal P-P plot. Ideally, you’ll end up with something similar to the plot below. The data looks like it was shot out of a shotgun—there is no discernible pattern, and points are evenly distributed above and below zero on the X axis, as well as to the left and right of zero on the Y axis.

The predictor variables in the regression have a straight line relationship with the outcome variable, which is known as linearity. You don’t have to worry about linearity if your residuals are normally distributed and homoscedastic (), which is true for this analysis.

When your predictor variables are highly correlated with each other, you have multi-collinearity. Correlation coefficients and variance inflation factor (VIF) values are two ways to check for multi-collinearity. Simply throw all your predictor variables into a correlation matrix and look for coefficients with magnitudes of.80 or higher to see if it’s true. Your predictors will be strongly correlated if they are multi-collinear. However, using VIF values, which we’ll show you how to generate below, is an easier way to check. You want these values to be <10.00, and the best case scenario would be if they were <5.00 ().

Table 8. Coefficients of the model.

4.2.2.2. Regression results and interpretation

The Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) is used to test the hypothesis that there is no linear relationship between the predictor and dependent variables, i.e. R-square = 0. The results of this test are presented in the ANOVA table in this study (). The F value is used to see if the regression model fits the data well. The hypothesis that R-square = 0 is rejected if the probability associated with the F statistics is small. The computed F statistic for this result is 265.546, with an observed significance level of <0.001. As a result, the hypothesis that there is no linear relationship between the predictor and dependent variables is rejected [F (943) = 265.546, p = .001].

Table 9. The ANOVA explained.

The explanatory powers of the variables used in the model are equal to 63% based on the R-squared values. This means that the variables used in this study’s model successfully explain 63% of the changes in leadership behavior. However, other factors not included in the study’s models are responsible for the remaining 37% of the changes.

The Coefficients table contains the necessary data for calculating the predicted responsibility attribution. Personal behavior, ineffective decision, negotiation problem, management incompetency, and political behavior are all significant predictors of destructive leadership behavior, as evidenced by the fact that all six predictor variables were entered into the prediction equation. R square is 62.7% adjusted (i.e. this amount of percentage of destructive leadership is explained by the factors included in this model) ().

Table 10. Regression model of the study.

Prediction Equation (Predicting the Level of destructiveness from the six factors of destructive leadership behavior); the prediction equation is:

where Y′ = the predicted dependent variable, A = constant, B = un standardized regression coefficient, and X = value of the predictor variable.

The prediction equation using the Constant and B (Unstandardized coefficient) values would be:

R-square, also known as the coefficient of determination is a measure of the strength of the computed prediction equation. The square of the correlation coefficient between Y, the observed value of the dependent variable, and Y′, the predicted value of Y from the fitted regression line, is R-square in the regression model. An R-square of 0 indicates that the predictor and dependent variables have no linear relationship.

Furthermore, the model’s overall significance, as measured by their respective F-Statistics F (943) = 265.546, p = .001, indicates that the model is well-fitted at the 1% level of significance. The results of R-squared and F-statistics show that the research model is well-fitting and that the mentioned factors have a significant impact on the behavior of leaders in the Awi zone ().

As a result, the researcher can identify possible determinant factors of destructive leadership behavior that affect success and analyze the way (direction of relationship) in which dependent variables are related to independent variables in the following section of the analysis. At p = 0.01, there is a positive significance difference between personal behavior, ineffective decision making, management incompetency, and political behavior. However, at the 1% significance level, the difference between political behavior and negotiation problem is negative. Poor communication, on the other hand, has a negative correlation with destructive leadership behavior, but the correlation is statistically insignificant at a 5% alpha level.

4.2.2.3. Results of correlation analysis

As shown in the table (see ), all of the independent variables, namely personal behavior, ineffective decision-making and management incompetency, political behavior, negotiation issues, and poor communication, are positively correlated and statistically significant at the 1% significance level.

Table 11. Correlation coefficient.

5. Discussion, conclusion, and recommendation

5.1. Discussion

For the purpose of identifying the prevalence of destructive leadership and its determining factors, the researchers had collected data from participant employees of the target organizations. Multiple researchers including Makin, and Corman indicates that even if numerous organizational researchers had focus on the constructive leadership behaviour to scaled to get the desired organizational performance, the another aspect of leadership in organization needs to be researched as fair as the constructive one. In this regard, this study identified the higher prevalence of destructive leadership behaviour in the selected organization of Awi zone, North West Ethiopia. According to the result of the statistical analysis, the prevalence of destructive leadership is attributed to factors of political and personal behaviour of a leader, poor communication, management incompetency, and poor decision making skill. This result is consistent with the finding of the study conducted by Shaw et al. (Citation2014) titled ‘Destructive leader behaviour: A study of Iranian leaders using the Destructive Leadership Questionnaire. Leadership’. In this same study, the researcher concluded that leader related concepts; organization related concepts and follower related concepts were the major factors that can determine the destructiveness of leaders in organizational settings.

5.2. Conclusions

The prevalence of destructive leadership behavior in Awi Zone was investigated in this study. After collecting the necessary data and analyzing it, the following major conclusions that are related to the objectives of the study were made.

According to the descriptive statistic result of the analysis, it was concluded that more than 65% of employees in the zone are vulnerable to destructive leadership behaviour. This result indicates that even if most of the time scholars and practitioners in Ethiopia and other areas of the world give due attention to good leadership for better organizational performance, this study indicates that organizations were experiencing destructive leadership practices that will hinder their productivity.

As it was indicated by different researchers, destructive leadership is not a separate leadership style rather it is behaviour that leader may consistently exhibits in the work place. From those behaviours identified by researchers, political behavior, ineffective in decision making, unable to negotiate, poor communication, management incompetency, and personal behavior were the behaviours the target public organizations’ leaders frequently exhibits. Those six factors were the most prevalent leadership behaviour in Awi zone.

Personal behavior, ineffective decision making, management incompetence, and political behavior all have a positive significance difference at p = 0.01 according to the regression results. However, at the 1% significance level, political behavior and negotiation problem are negative. Poor communication, on the other hand, has a negative correlation with destructive leadership behavior, but the correlation is statistically insignificant at a 5% alpha level. Accordingly, this statistical output shows that from the behaviours indicating the prevalence destructive leadership in the target research area, poor communication has no direct relation with the presence and absence of destructive leadership practice in organizations. So, it can be concluded that a leader who is not good at communication with others may not show his/her destructive leadership behaviour.

5.3. Recommendations

After all, as evidenced by this and other researches in the field, harmful leadership is common, and dealing with problematic leaders is a difficult task. The organization can, however, take several steps to prevent, manage, and hopefully eliminate this toxic leadership style. It was thought that the best way for organizations to avoid destructive leadership is for them to be selective in their hiring and promotion practices (personal behavior is the most important factor in destructive leadership behavior), as well as to clearly state and model the positive leadership values and behaviors that the organization values.

Furthermore, businesses should actively and consistently foster a climate in which workers feel free to speak out about circumstances that they believe violate not just their own, but also the company’s values. Senior management is responsible for aiding those who have reported such problems and ensuring that they are addressed properly and quickly once they have been raised.

Acknowledgements

I’d like to express my gratitude to everyone who supported me during the research process, particularly the employees in each woreda who gave up their time to participate in the study and share their perspectives and practices.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Eshetu Mebratie

Eshetu Mebratie Muluneh is a lecturer at Injibara University, Ethiopia. His current area of interest is leadership, human resource management and business administration.

Birhanu Shanbel

Birhanu Shanbel Andargie is a lecturer at Injibara University, Ethiopia. His current research interests are business management, organizational leadership and organizational behavior.

References

- Aasland, M. S., Skogstad, A., Notelaers, G., Nielsen, M. B., & Einarsen, S. (2010). The prevalence of destructive leadership. British Journal of Management, 21(2), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2009.00672.x

- Anjum, A., & Muazzam, A. (2018). The gendered nature of workplace bullying in the context of higher education. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research, 33.

- Antoniou, A. S., Burke, R. J., & Cooper, S. C. L. (Eds.). (2016). The aging workforce handbook: individual, organizational, and societal challenges. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Aryee, S., Chen, Z. X., Sun, L. Y., & Debrah, Y. A. (2004). Examining the mediating and moderating influences on the relationships between abusive supervision and contextual performance in a Chinese context [Paper presentation]. Paper presented at the 4th Asia Academy Management Conference, December 16–18, Shanghai, China.

- Ashforth, B. E. (1987). Petty tyranny in organizations: An exploratory study [Paper presentation]. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Academy of Management, New Orleans, LA, USA.

- Avolio, B. J., & Walumbwa, F. O. (2014). Authentic leadership theory, research and practice: Steps taken and steps that remain. In D. V. Day (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of leadership and organizations (pp. 331–356). Oxford University Press.

- Awi Zone Administration Human Resource Development Office (2020). Annual employment opportunity creation performance in Awi Zone public organizations. Annual report, Awi Zone Human Resource Development Office, Injibara.

- Ayalew, S., Manian, S., & Sheth, K. (2018). Discrimination from below: Experimental evidence on female leadership in Ethiopia. Technical report, Mimeo.

- Bamberger, P. A., & Bacharach, S. B. (2006). Abusive supervision and subordinate problem drinking: Taking resistance, stress and subordinate personality into account. Human Relations, 59(6), 723–752. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726706066852

- Bartlett, M. S. (1951). A further note on tests of significance in factor analysis. British Journal of Statistical Psychology, 4(1), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8317.1951.tb00299.x

- Bass, B. M., Avolio, B. J., Jung, D. I., & Berson, Y. (2003). Predicting unit performance by assessing transformational and transactional leadership. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(2), 207–218. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.2.207

- Brodsky, C. M. (1976). The harassed worker. Lexington Books, DC Heath.

- Burke, C. S., Stagl, K. C., Klein, C., Goodwin, G. F., Salas, E., & Halpin, S. M. (2006). What type of leadership behaviors are functional in teams? A meta-analysis. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(3), 288–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2006.02.007

- Burke, R. J., & Page, K. M. (Eds.). (2017). Research handbook on work and well-being. Edward Elgar Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781785363269

- Dea, T., & Tekalign, T. F. (2022). The practice of managerial leadership roles and its effect on building human resource capability: The case of North Wollo Zone, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. Asia-Pacific Journal of Management Research and Innovation, 18(3–4), 131–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/2319510X221148617

- Einarsen, S., Aasland, M. S., & Skogstad, A. (2007). Destructive leadership behaviour: A definition and conceptual model. The Leadership Quarterly, 18(3), 207–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2007.03.002

- Einarsen, S., Skogstad, A., & Aasland, M. S. (2010). The nature, prevalence, and outcomes of destructive leadership: A behavioral and conglomerate approach, 145–171.

- Erickson, A., Shaw, B., Murray, J., & Branch, S. (2015). Destructive leadership: Causes, consequences and countermeasures. Organizational Dynamics, 44(4), 266–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2015.09.003

- Gallup (2017). State of the American workplace. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/y8f9cct2

- Hornstein, H. A. (2016). Boss abuse and subordinate payback. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 52(2), 231–239. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886316636308

- Hoobler, J. M., & Brass, D. J. (2006). Abusive supervision and family undermining as displaced aggression. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(5), 1125–1133. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.5.1125

- Jolliffe, I. T. (2002). Principal components analysis. Springer.

- Kellerman, B. (2004). Bad leadership: What it is, how it happens. Why It, 282.

- Kelloway, E. K., Mullen, J., & Francis, L. (2006). Divergent effects of transformational and passive leadership on employee safety. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 11(1), 76–86. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.11.1.76

- Kile, S. (1990). Health endangering leadership. Universitetet I Bergen.

- Kim, H. T. (2020). Linking managers’ emotional intelligence, cognitive ability and firm performance: Insights from Vietnamese firms. Cogent Business & Management, 7(1).

- Kim, J.-O., & Mueller, C. W. (1978). Factor analysis: Statistical methods and practical issues.

- Krasikova, D. V., Green, S. G., & LeBreton, J. M. (2013). Destructive leadership: A theoretical review, integration, and future research agenda. Journal of Management, 39(5), 1308–1338. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206312471388

- Martinko, M. J., Harvey, P., & Douglas, S. C. (2007). The role, function, and contribution of attribution theory to leadership: A review. The Leadership Quarterly, 18(6), 561–585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2007.09.004

- McCleskey, J. (2013). The dark side of leadership: Measurement, assessment, and intervention. The Business Renaissance Quarterly: Enhancing the Quality of Life at Work, 8(2/3), 35–53.

- Mengistu, A. B., & Lituchy, T. R. (2017). Leadership in Ethiopia. In LEAD: Leadership effectiveness in Africa and the African Diaspora (pp. 177–199).

- Meuser, J. D., Gardner, W. L., Dinh, J. E., Hu, J., Liden, R. C., & Lord, R. G. (2016). A network analysis of leadership theory: The infancy integration. Journal of Management, 42(5), 1374–1403. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316647099

- Namie, G. (2003). Workplace bullying: Escalated incivility. Ivey Business Journal.

- Namie, G., & Namie, R. (2000). Workplace bullying. USA research. www.workplacebullying.org/multi/pdf/NN-2000.pdf.

- Nkansah, B. K. (2011). On the Kaiser-Meier-Olkin’s measure of sampling adequacy. Mathematical Theory and Modeling, 8, 52–76.

- Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Nyberg, A., Holmberg, I., Bernin, P., Alderling, M. (2011). Destructive managerial leadership and psychological well-being among employees in Swedish, Polish, and Italian hotels. Work, 39(3), 267–281. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-2011-1175

- Patton, M. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods. Sage.

- Pynnönen, A., & Takala, T. (2013). Recognised but not acknowledged: Searching for the bad leader in theory and text. Electronic Journal of Business Ethics and Organizational Studies.

- Saleem, F., Malik, M. I., & Malik, M. K. (2021). Toxic leadership and safety performance: Does organizational commitment? Congent Business & Management.

- Schilling, J., & Schyns, B. (2014). The causes and consequences of bad leadership. Zeitschrift für Psychologie, 222(4), 187–189. https://doi.org/10.1027/2151-2604/a000185

- Schyns, B., & Schilling, J. (2013). How bad are the effects of bad leaders? A meta-analysis of destructive leadership and its outcomes. The Leadership Quarterly, 24(1), 138–158.

- Shaw, J. B., Erickson, A., & Nassirzadeh, F. (2014). Destructive leader behaviour: A study of Iranian leaders using the Destructive Leadership Questionnaire. Leadership, 10(2), 218–239. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742715013476082

- Skogstad, A., Aasland, M. S., Nielsen, M. B., Hetland, J., Matthiesen, S. B., & Einarsen, S. (2014). The relative effects of constructive, laissez-faire, and tyrannical leadership on subordinate job satisfaction. Zeitschrift für Psychologie, 222(4), 221–232. https://doi.org/10.1027/2151-2604/a000189

- Tavanti, M. (2011). Managing toxic leaders: Dysfunctional patterns in organizational leadership and how to deal with them. Human Resource Management, 2011, 127–136.

- Tepper, B. J. (2000). Consequences of abusive supervision. Academy of Management Journal, 43(2), 178–190. https://doi.org/10.2307/1556375

- Tepper B. J. (2007). Abusive supervision in work organizations: Review, synthesis, and research agenda. Journal of Management, 33(3), 261–289. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206307300812

- Tran, Q., Tian, Y., Li, C., & Sankoh, F. P. (2014). Impact of destructive leadership on subordinate behavior via behavior, loyalty and neglect in Hanoi, Vietnam. Journal of Applied Sciences, 14(19), 2320–2330. https://doi.org/10.3923/jas.2014.2320.2330

- Vogel, R. M., Mitchell, M. S., Tepper, B. J., Restubog, S. L., Hu, C., Hua, W., & Huang, J. C. (2015). A cross-cultural examination of subordinates’ perceptions of and reactions to abusive supervision. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(5), 720–745. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1984

- Yamane, T. (1967). Statistics, an introductory analysis (2nd ed.). Harper and Row.

- Yekkalam, N., Coello, E., Mikaela, E., Hajer, J., Nikolaos, C., & Ernberg, M. (2019). Could reported sex differences in hypertonic saline-induced muscle pain be a dose issue? Dental Oral Biology and Cranofacial Research, 2(5), 3–8.

- Zellars, K. L., Tepper, B. J., & Duffy, M. K. (2002). Abusive supervision and subordinates’ organizational citizenship behavior. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(6), 1068–1076. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.6.1068