?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

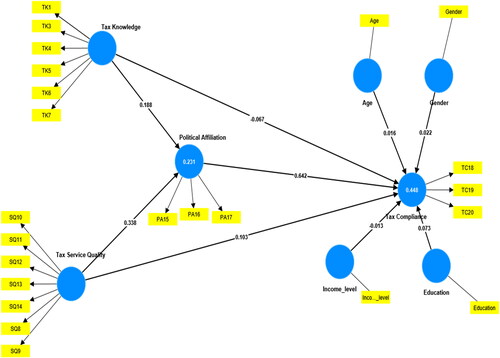

This study investigates the moderating role of political party affiliation in the relationship between tax knowledge, service quality, and tax compliance. The study gathered data from 450 respondents comprising informal sector traders within the Kejetia market through a structured questionnaire administered by the Ashtown Small Tax Office personnel. The demographic characteristics reveal age, income, and education as key control variables significantly influencing compliance. Using the Partial Least Square Structural Equation Model (PLS-SEM), the study finds a significant and direct positive relationship between tax knowledge and tax compliance. Additionally, service quality positively and significantly affects tax compliance. Meanwhile, the indirect results reveal that political affiliation positively mediates the relationship between tax knowledge and compliance. The same positive mediation effect was realized for the relationship between service quality and tax compliance. Further robustness checks using demographic segmentations reveal a significant positive correlation between young and old tax compliance groups. Also, low-income taxpayer groups exhibit a positive influence on compliance. The educated group has a significant positive effect on tax compliance. The indirect effect of political affiliation is also positively significant for all categories of demographic segmentation. These outcomes highlight the dynamic role of political party affiliation in enhancing national voluntary tax compliance. The study recommends that individual taxpayers perceive tax compliance as a civic duty and not based on partisanship through political party affiliation. However, the government should also ensure equitable distribution of national infrastructure.

1. Introduction

Taxation, as an integral part of fiscal policies, is a pivotal driver of economic growth, especially in developing and underdeveloped countries. Taxes are a vital gauge of these policies and play a significant role in fostering sustainable economic development (Gurdal et al., Citation2021). Irrespective of a nation’s economic standing, the fundamental goal of taxation remains consistent: to generate revenue for financing government expenditures on essential services and goods (Mpofu, Citation2022). When a country experiences unusually high annual expenses, taxes become a more appropriate and preferable method for funding the state budget. In light of the adverse impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the economies of developing and underdeveloped countries, Ghana has become increasingly reliant on external aid, even after several attempts to reform its tax system (Gallien et al., Citation2021). Tax revenue as a source of budgetary support remains challenging for most governments, stemming from excessive dependence on external aid, deficiencies in tax systems and regulations, and illicit practices (Abdu & Adem, Citation2023).

Over time, tax compliance challenges have persisted due to the inherent reluctance of individuals and corporations to pay taxes (Abdallah, Citation2014). In response, Ghana’s government has undertaken various tax reforms in recent decades to improve compliance (Nsubuga et al., Citation2017). These reforms have encompassed initiatives like tax education and incentives. In 1985, Ghana initiated its first significant tax reform to establish a flexible and efficient revenue structure, aiming for higher returns. The introduction of self-assessment through the Ghana Revenue Authority allowed taxpayers to calculate and submit taxes voluntarily, thereby promoting compliance (Abdallah, Citation2014). Subsequent reforms included the implementation of a communication service tax Act (Act 754) and vehicle income tax, alongside the creation of the Ghana Revenue Authority (GRA) and its digital integration with the Registrar General’s Department (RGD). Ghana’s taxation research has predominantly focused on administrative reforms and addressing corruption. Despite multiple tax reforms, studies by Ayee (Citation2007) and Terkper (Citation2007) revealed persistently low tax compliance levels in the informal sector. Adebisi and Gbegi (Citation2013) and Tanko (Citation2015) also confirmed this trend in developing countries like Ghana. In such nations as Ghana, tax compliance largely hinges on the substantial presence of the informal sector, comprising around 80% of employment, and deficiencies in the tax system (Ayee, Citation2007). Many informal sector entities in Ghana remain unregistered with tax authorities, leading to non-compliance (Carroll, Citation2011). Across countries, a direct correlation exists between revenue generation and tax compliance (Elmirzaev & Kurbankulova, Citation2016). Taxes in the informal sector are typically smaller and primarily indirect due to the limited number of registered informal businesses

Prior research has explored the connections between service quality and tax compliance (Susuawu et al., Citation2020) and tax education’s impact on compliance (Fagariba, Citation2016). Bruce-Twum (Citation2014) has noted the low public awareness concerning tax reforms and education. Kumi et al. (Citation2023) further extended research on voluntary tax determinants by examining trust, tax rates, and authority posed by tax authorities as potential voluntary tax compliance determinants in agrochemical SMEs. The study, through its findings, confirmed the slippery slope framework. The study by Nartey (Citation2023) also confirmed factors like the tax system’s fairness and isomorphic forces’ significant have a positive impacts on tax compliance among SMEs. Among the majority of global tax compliance determinants research, it is evident from previous literature on compliance determinants that service quality, trust, tax awareness/tax education, compliance cost, and tax rates have been the widely engaged variables within this research domain (Musimenta, Citation2020).

Theoretically, most tax compliance literature have extensively employed the theory of planned behavior. Studies of such resorted to intention as a measure of tax compliance. Several concerns have been raised about applying the theory of planned behavior, as differences seldom exist between real behavior and intentions. Sayidah and Assagaf (Citation2019) contend that situational factors can generate a positive intention for tax compliance among taxpayers. Consequently, they suggest that specific recommendations from such studies may not accurately reflect the real-life experiences of individuals dealing with taxation. Existing studies in Ghana have produced inconclusive results, often neglecting informal sector businesses registered with the Ghana Revenue Authority. Regarding methodology, extant literature predominantly used ordinary least squares (OLS) and partial least squares to examine the relationship between the variables. Others have extensively employed correlations to measure causal relationships, often giving misleading results.

Religion and politics are regarded as elements that Ghanaians hold in high esteem and, hence, highly inclined to. In some way, these institutions indirectly affect governance policies, such as tax compliance. The various religious doctrines and political affiliations that affect balance have contributed negatively or positively to total national tax revenue. Carsamer and Abbam (Citation2023) have recently investigated the role religion plays in selected Ghanaian SMEs’ tax compliance. However, the results contradicted the hypothesis of expecting a positively significant relationship. It explained that SMEs’ tax compliance and tax evasion attitudes were only regarded as ethical. Numerous research investigations reveal associations between political ideology and economic spheres, encompassing economic beliefs, perceptions, and consumer sentiment. Evans and Andersen (Citation2006) observed a significant influence of political preferences on everyday economic perceptions.

Moreover, there is a connection between politics and economic matters concerning consumer sentiment. Individuals aligning themselves with political parties anticipated to win upcoming elections tended to boost consumer confidence (Lozza et al., Citation2013). Within the Western Landscape, several studies have investigated how political party affiliation may impact the compliance attitude of taxpayers. In the United States, Hunt et al. (Citation2019) investigations highlighted how partisan reactions to post-presidential elections influence the affect balance of particular groups of people in their tax compliance behaviors. Also, Lozza et al. (Citation2013) assessed the relationship between political ideology and tax compliance attitude in Italy. This theme has not yet been investigated within the Ghanaian context, where politics is active in almost all other institutional activities.

These major gaps, particularly in political party affiliation, have set the tone for this research. As a minor factor, political party affiliation tends to affect several determinants of tax compliance, particularly for informal sector traders. Primarily, this study examines the effect of the mediating role of political affiliation on the relationship between tax knowledge, service quality, and tax compliance. This study offers a vast contribution to the extant literature on tax compliance. First, partisan politics remains a treat to the development of many developing countries, particularly in Africa. Hence, if political affiliation tends to impact the compliance attitude of a particular group of people, then there is a need to worry. Our results will provide new evidence to policy makers on the need to strengthen a wholistic tax education campaign and not remain partisan. African politics have mainly produced unequal resource distribution and infrastructure, adversely affecting the revenue needed for development.

Given their limited exploration in previous research, a novel perspective will be established by introducing the slippery slope framework and social identity theory into the Ghanaian context. Emphasizing the informal sector through these frameworks will contribute to more informed policy decisions. This approach encourages collaboration between parliament and tax authorities to treat the country’s tax system as impartial and independent, preventing it from being influenced by partisanship. This is particularly crucial for taxpayers in the informal sector, especially those with lower levels of education. Ultimately, the study aims to dispel the notion that politics fosters hostility.

2. Background

The informal sector has dominated chiefly the economic landscape of Ghana. Yet, mechanisms to effectively inculcate these sectors into this tax system remain burdensome, leaving many individuals from these sectors not complying with tax. The informal sector plays a substantial role in the economic activities of developed and developing nations, serving as a source of livelihood and employment for most people worldwide (La Porta & Shleifer, Citation2014). Statistical report from the Ghana Statistical Service revealed that of the total recorded figures for SMEs, approximately 91% were within the informal sectors and contributed immensely to the nation’s GDP and employment (Abor & Quartey, Citation2010). Ghana’s political culture has placed a little premium on the activities of informal sector traders. Hence, not much attention has been focused on policy reforms that could draw more revenue from these sectors. The partisan behavior of traders within these sectors, coupled with their low level of education, fuels a certain affect balance that tends to influence tax compliance behavior. Research on tax compliance attitudes within the Ghanaian setting has covered various variables. Within the context of SMEs, (Ernest et al. (Citation2022) focused on tax drivers of tax compliance cost and identified the size and age of enterprises as potential drivers. Vincent et al. (Citation2023) investigated the influence of sociodemographic traits as drivers of tax compliance. (Amoah et al. (Citation2023) examined trust in government and the use of electronic levy payment in shaping taxpayers’ compliance behavior. No study conducted within the Ghanaian context investigated the role of political party affiliation in reshaping taxpayers’ tax knowledge prowess and perceived service quality on tax compliance. Until empirical investigations are conducted and these hypotheses tested, one can only believe from assumptions.

Imagine that you have recently exercised your voting right for the president of your country. After a prolonged campaign season, you firmly believe that the candidate you supported aligns closely with your political ideology and perspectives. If your chosen candidate emerges victorious, you will feel jubilant and appreciative, anticipating a substantial impact on forthcoming legislative policies that resonate with your beliefs. Conversely, if your candidate fails, you will grapple with negative emotions, bracing yourself for legislative decisions that may not align with your views. Considering the emotional impact of these outcomes, how might they shape your overall sentiments toward the government and potentially influence your decisions regarding tax compliance? These aspects of tax compliance remain unresearched even though they exist in practicality. The democratic system of governance within Ghana has paved the way for a multiparty system, permitting individuals to freely choose their party of affiliation (Abdulai & Crawford, Citation2010). Despite adopting multiparty democracy in the country, a pattern has emerged in the fourth republic since 1992, where only two political parties have consistently secured victory in successive elections. This trend has given rise to a culture of partisan politics and clientelism, potentially exerting a notable influence on the implementation of government programs and projects in Ghana, influencing the citizenry’s decision to even comply with tax ((Akwei et al., Citation2020).

Furthermore, an insightful observation made by Asunka (Citation2016) reveals a significant correlation in various regions where voter allegiance to political parties is less entrenched. There is a discernible uptick in Ghanaians’ conscientious adherence to formal rules and procedures in these areas. This phenomenon implies that the execution of government programs and policies might encounter deficiencies concerning compliance with established protocols. As a result of these potential shortcomings in the implementation process, a considerable window of opportunity arises for politicians to exploit vulnerabilities within the tax system. This exploitation could manifest in voluntary negligence for personal gain, thereby underscoring the critical importance of addressing and rectifying these systemic weaknesses to ensure the integrity and equitable execution of public initiatives. With no exploration into the impact of political affiliation in the Ghanaian context and insufficient evidence-based studies, policymakers might find it tempting to depend on studies conducted in different geographical areas. Methodological challenges and variations in regional characteristics could undermine this. This study investigates the influence of political party affiliation on the relationship between tax knowledge, service quality, and tax compliance among informal sector traders in Ghana’s "Kumasi-Kejetia" market. The rest of the paper follows a sequential order: theoretical review of literature, empirical review of literature and hypotheses development, research design, empirical results and discussion, and summary and conclusion.

3. Theoretical framework

Research on tax compliance behavior has over the past decades used the theory of planned behavior to investigate the relationship between several ranges of variables proxied as determinants or drivers of tax compliance behavior (Bani-Khalid et al., Citation2022; Taing & Chang, Citation2021). The same is said of the economic deterrence model (Murphy, Citation2008). Our study introduces quite a new perspective of theories and framework to explain the importance of political party affiliation on the relationship between tax knowledge and service quality on compliance. The current study is based on the slippery slope framework and social identity theory. The slippery slope framework has extensively been used in the Western world to investigate political ideology through party affiliation’s impact on tax compliance behavior. The comprehensive slippery slope model was conceived as an all-encompassing framework, consolidating various facets of research on tax compliance (Kirchler et al., Citation2008). The framework is premised on trust in governance, which transcends to tax authorities as a governmental institution. Thus, it is built on the idea that the socio-political ethos within a society shapes the pathway to achieving collaboration among its members. When the interaction between authorities and taxpayers is marked by mutual reliance and a prevailing service-client approach, fostering a harmonious atmosphere, taxpayers are prone to abide by the law and willingly fulfill their tax obligations. As a result, there is a manifestation of voluntary adherence to tax regulations, driven by a sense of duty to meet societal needs when trust is robust.

The theoretical framework views trust through a relational lens emphasizing the aspect of ‘social trust’. In this context, trust is not seen as a calculated concept. Trust as a calculated concept occurs by rationalizing gains and losses to maximize outcomes. Trust, approached as a calculated concept, arises from a rational assessment of potential gains and losses to optimize outcomes. Social trust is the overall perception individuals and social groups hold that tax authorities are benevolent and actively contribute to the common welfare. Trust and knowledge co-exist indirectly. Trust instills confidence in the accuracy and fairness of the tax system, motivating individuals to seek out and understand tax regulations proactively. In such an environment, governments can effectively communicate the rationale behind tax policies, provide clear guidance on compliance procedures, and offer educational programs that contribute to citizens’ overall tax literacy. Several studies have explained how trust favorably influences tax compliance (Richardson, Citation2008; Torgler & Schneider, Citation2005). The designation ‘slippery slope framework’ stems from the analogy that ensuring or attaining heightened tax compliance within a societal structure is akin to navigating a slippery slope. In a societal context, individuals are shaped by their belief and trust in their social group, in this case, their party of political affiliation. As such, any attempt to displease these groups will mean their dissociation or interest, regardless of whether the issues are of national concern.

Various empirical studies examining the premises of the slippery slope framework have yielded encouraging findings. Wahl et al. (Citation2010) investigated how trust relates to voluntary compliance and how power relates to enforced compliance. Kogler and Kirchler (Citation2020) used scenario planning to manipulate trust and perceived power in Austria, Hungary, Romania, and Russia. This involved portraying the political and tax climates of a hypothetical country. The outcomes indicated that elevated trust increased voluntary tax compliance, while heightened power led to greater enforced tax compliance. Prinz et al. (Citation2014) assessed the potency of the slippery slope framework to investigate the attitude of compliance-minded and evasion-minded taxpayers. Investigations into tax compliance initially operated within the confines of the classical economic paradigm.

Nevertheless, numerous studies have shown that the ‘crime paradigm’ only partially explains taxpayer behavior. The slippery slope framework introduces a novel perspective, denoted as the "service paradigm", which posits that taxpayers are not solely rational actors driven by utility maximization. Instead, they are individuals expecting fair treatment and high-quality public services in exchange for their tax contributions. This dimension was evident from the research of da Silva et al. (Citation2019). The findings validate the presence of trust-oriented interactions between taxpayers and public administration, fostering voluntary compliance. Conversely, strategies centered on the exercise of authority lead to obligatory compliance. In investigating the slippery slope framework, introducing political party affiliation brings an additional layer of complexity. As the introduction and background mentioned, various studies have connected political party affiliation to backing specific tax policies or harboring general attitudes toward taxation. These observations prompt an exploration into the correlation between political affiliation and perspectives on tax compliance. For instance, it is anticipated that individuals aligning with the ruling party may exhibit greater responsiveness to voluntary tax compliance due to their positive affect balance. Conversely, those associated with opposing ruling parties might manifest higher levels of compelled cooperation (rather than voluntary tax compliance) owing to their more antagonistic stance toward taxation.

The social identity theory is a comprehensive theoretical framework originally propounded by Tajfel et al. (Citation1979). At its essence, the theory posits that in numerous social contexts, individuals tend to view themselves and others through the lens of group membership rather than as distinct individuals. This theory contends that social identity plays a foundational role in shaping intergroup behavior, and it distinguishes such behavior as qualitatively different from interpersonal interactions. Moreover, it outlines the conditions in which social identities are prone to assume significance, becoming the foremost determinants of social perceptions and behaviors. Political psychology research has concentrated on elucidating the characteristics of political identities, encompassing affiliations with major political parties or adopting an ideological label for self-identification. In their study, Duck et al. (Citation1998) delved into the social aspects of political identities, such as conservatism, environmentalism, liberalism, pacifism, radicalism, and socialism. Their conclusion emphasized that predictions stemming from social identity theory are most likely to be relevant to identities of an ethnic, religious, or political nature because they possess a more "collective in nature" essence compared to other individual facets of identity.

Drawing insights from social identity theory, one can infer that political party affiliation probably plays a significant role in shaping the emotions political partisans may experience in relation to compliance. Sloan (Citation1989) has identified that the conduct of sports fans is frequently guided by achievement theory, proposing that an individual perceives personal accomplishments align with the successes of their favorite team. Research has delved into the connection between trust and social identity theory, as Robbins (Citation2017) indicated. Numerous scholars have directed their attention to understanding the factors influencing trust in government (Keele, Citation2005). A common observation is that citizens tend to be more trusting when their political party holds the presidency, and such trust shapes their knowledge of fiscal policies. Data from the United States illustrates a consistent pattern where Republicans exhibit higher trust when a Republican president is in office, and Democrats express greater trust during Democratic presidencies (Pew Tan et al., Citation2007). In essence, citizens are inclined to trust the government when they believe its policies align with their preferences. Partisans, driven by an affective attachment to their political party, believe their party will advocate for their policy preferences or consider their well-being in policymaking, thereby influencing compliance responsiveness (Campbell et al., Citation1960). This affective attachment is a consequential factor.

In the study of Dwianika et al. (Citation2023), the focus was on community and memberships as elements within the social identity theory influencing compliance behavior. Consequently, enhancing these social identity factors contributes to an improvement in overall corporate tax compliance. Wenzel (Citation2007) expanded the social change theory to examine identity and its repercussions on tax ethics and compliance. The exploration delved into taxpayers’ identities at various levels and their interconnection with attitudes toward tax ethics. Within the Ghanaian context, the theory of social change may be applied to studies on tax compliance since extant investigations have considered how social identity shapes the knowledge behavior, and perception of a group (being identified with a political party). The predominant nature of ascribed social identity, particularly among illiterates, explains their affect balance and gross attachment to policies that shape the image of their social group.

4. Empirical literature review and hypothesis development

4.1. Tax knowledge and tax compliance

Compliance with tax within the context of the theories discussed is viewed as voluntary or enforced depending on the perceived trust in government and authorities and partisanship stemming from social identity (Robbins & Kiser, Citation2020). The authors believe that tax knowledge as a driver of tax compliance behaviors is influenced by the repository of trust a particular group of people places in the government and the authorities. Tax knowledge is associated with the steps put in place to effect change in the attitude and behavior of a taxpayer or group of taxpayers. This step is usually taken through teaching, education, and training efforts. Knowledge of tax enhances tax literacy, which has a rippling effect of positively strengthening taxpayers’ efforts to be willing to pay tax (Nichita et al., Citation2019). This will help increase taxes and improve economic growth (Abuselidze, Citation2020). Gaining knowledge of tax laws and regulations through informal and formal education takes such forms as tax campaigns, counseling, and tax clinics. Over the years, the Ghana Revenue Authority has embarked on tax education campaigns, mainly targeting those within the informal sectors.

From a patriotic standpoint, individual taxpayers should, as part of their civic duty, seek tax information as this will enhance their compliance level. Tax knowledge has been argued to be an effective measure for mitigating tax evasion. Knowledge about tax through tax literacy helps arouse tax-paying consciousness, thereby allowing taxpayers to recognize what is expected of them as their tax obligation. How taxpayers willingly seek tax information and are knowledgeable about them is seen to be influenced by several factors as trust (Rachmawan et al., Citation2020; Sakirin et al., Citation2021), power (Hasseldine et al., Citation2011; Mas’ud et al., Citation2019), partisanship (McGowan, Citation2000; Shin, Citation2017). Expanding the literature on tax knowledge and tax compliance premised on our research theories, Sithebe (Citation2022) investigated the relationship between tax knowledge and tax compliance using collected primary data from selected SME respondents. The study employed both inferential and descriptive to analyze the collected data. Results reveal a positive link between the two variables. However, this study was limited in its methodology as more descriptive and inferential analysis may be misleading. In the same line of research, Djawadi and Fahr (Citation2013) examined the factors influencing tax compliance, including controls for tax commitment, risk attitude, income, and effort expended, drawing on insights from previous research. The non-parametric statistical analyses and multivariate regressions reveal that higher tax compliance is associated with reduced authority power in tax systems. Additionally, increased compliance is observed in contexts with transparent public expenditures and where taxpayers have a role in determining the allocation of their taxes.

Saad (Citation2014) utilized telephone interviews in New Zealand to establish the relationship between tax knowledge and compliance. The data analysis utilized a thematic focus, revealing that taxpayers possess limited technical understanding and view the tax system as intricate. Concerning compliance behavior, participants generally opined that factors such as attitude, perceived behavioral control, complexity, and fairness perceptions have contributed, in part, to taxpayers’ non-compliance. According to Alm (Citation2019), there is a clear assertion that taxpayers’ level of knowledge about the tax system influences compliance, although the specific impacts remain inconclusive. The author emphasizes that taxpayers exhibit significant diversity in their understanding of tax requirements, ability to acquire knowledge about their obligations, perceptions of the consequences of non-compliance, and awareness of available services to aid them in tax matters. Tax knowledge was employed as a moderating variable on VAT compliance to explain tax compliance behavior within the retail industry (Lutfi et al., Citation2023).

Few studies exist that explain the mechanism of political party affiliation as a mediation between tax knowledge and tax compliance, and these have been outside the African context. The mediation role explains how political party affiliation indirectly influences the nexus between tax knowledge and compliance. In a study conducted by Evans and Andersen (Citation2006), it was discovered that political choices had a considerable influence on ordinary economic perceptions. Moreover, consumer opinion connects political and economic concerns. Other studies also concluded that consumer preferences will likely increase pending the expectation of their party winning elections (Kleine & Minaudier, Citation2019). Among studies focusing on political ideology, the majority have only investigated the correlation between tax ideology and specific tax policies and reforms, preference for fiscal policies, and tax cut supports. Hunt et al. (Citation2019) examined the role of political affiliation on tax compliance resulting from election outcomes. The study dwelled on the affect balance mechanism to explain how partisanship could influence tax compliance. If individuals have a positive affect balance toward their political party, they may be more inclined to align with the party’s perspectives on taxation. This alignment can lead to a greater interest in acquiring tax-related knowledge, as individuals may view it as integral to supporting their party’s positions. On the other hand, a negative affect balance might create disinterest or skepticism, potentially resulting in a lower motivation to stay informed about tax matters. Their research findings suggest that election results evoke substantial positive or negative emotions among partisans. These emotions, in turn, impact their perceptions of trust in the government, shaping their acquired tax knowledge and subsequently influencing their intentions regarding tax compliance.

In substantiating the conclusions put forth by Hunt et al. (Citation2019), the comprehensive investigations conducted by Lozza et al. (Citation2013) meticulously scrutinized the intricate dynamics of how political ideology exerts its influence on taxpayers’ attitudes toward compliance. It was observed that individuals harboring left-leaning views not only showcased a discernible bias towards greater voluntary cooperation but also explicitly manifested resistance to the authoritative exercise of power. Conversely, taxpayers espousing right-leaning perspectives exhibited a pronounced and heightened commitment to enforced tax compliance, thereby unequivocally articulating a more robust stance against tax evasion. Embarking on a thorough examination of the influence of political factors, particularly the intricate partisanship, over a considerable duration spanning three decades, the scholarly work undertaken by Osterloh and Debus (Citation2012) is brought to light. This in-depth exploration involved employing an innovative measure of ideology, meticulously derived through content analysis of party manifestos, seamlessly woven into the fabric of public finance literature. The findings of this research lend robust support to the hypothesis positing that partisanship, rooted in political ideology, has a discernible impact on tax knowledge among individuals. It is worth noting that the outcomes of significance also underscore a noteworthy trend: the partisan effect on tax knowledge exhibits a diminishing trajectory over the unfolding course of time. The elaborated literature brings us to the following hypotheses;

H1a: There is a significant positive relationship between tax knowledge and tax compliance

H1b: Political affiliation mediates the relationship between tax knowledge and tax compliance.

4.2. Service quality and tax compliance

Taxes constitute a significant part of government revenue, of which state infrastructure expenditures are majorly financed (Mallick, Citation2021). Customer satisfaction has been viewed to be one of the major ingredients of excellent service. Anytime an organization operates as expected to meet customers’ needs, it delivers excellent service. Parasuraman et al. (Citation1988) iterate that service quality denotes the envisioned standard of excellence that taxpayers anticipate during service reception, fulfilling their expectations in the delivery of services. In developing countries like Ghana, the issue of tax authorities’ service quality has become increasingly crucial due to poor revenue performance (Amoh & Ali-Nakyea, Citation2019). The willingness of taxpayers to pay taxes is mostly attributed to how fair they view the tax system. Taxpayers always expect the state government to diligently account for the taxes by providing them with the needed social amenities and infrastructure. Seralurin et al. (Citation2021) explored the impact of tax service quality on the compliance behavior of taxpayers in Jayapura City, Indonesia. The study involved a sample of 99 taxpayers as respondents. The SmartPLS results revealed a substantial connection between the quality of tax services and taxpayers’ compliance. On the far end, Sugiyarti et al. (Citation2021) observed a noteworthy adverse impact of tax service quality on tax compliance among taxpayers. The research, characterized by a qualitative approach, posits that enhancing public trust is worthwhile for improving tax compliance.

The tone of partisanship within Ghana’s political framework has created a series of problems regarding resource distribution. The prevalence of partisan politics and the embrace of a ‘winner takes all’ approach has indirectly resulted in the widespread practice of clientelism in Ghana. Consequently, citizens align themselves with political parties, enticed by various incentives such as survival tactics, tangible outcomes, immediate or future rewards, and social and individual advantages within the Ghanaian context (Bob-Milliar, Citation2012). The extensive prevalence of clientelism in the nation has given rise to institutional impediments within the public administration framework (Amoako & Lyon, Citation2014). Resources distribution across the regions of Ghana has been considered unfair and politically favored. Mostly, districts or areas receiving the benefits they deem fit are politically motivated to comply with tax (Fershtman & Lipatov, Citation2009). Two dominant political parties have always been on the herms of affairs during constitutional elections. These two major parties have their powerhouses (strongholds) attributed to specific regions and cities of the country. Aside from being favored by their parties when distributing the national cake, these cities or regions are seen as being so subjective regarding matters involving their political party, regardless of how neutral they may have to be for the national interest.

In furtherance, the study of Prinz et al. (Citation2014), through the application of the slippery slope framework, confirmed that the perceived service quality from the government and their respective tax authorities enhances compliance. To support this assertion, Ayuba et al. (Citation2018) conducted a study in Nigeria on taxpayers within SMEs. The study employed the PLS-SEM to observe the relationship between perceived service orientation and tax compliance. The results indicate that the interplay between perceived corruption and perceived service orientation significantly contributes to unraveling the contradiction associated with tax compliance. From the discourse put forth, we therefore proposed the below hypotheses;

H2a: Service quality and tax compliance have a significant positive relationship.

H2b: political affiliation mediates the relationship between service quality and tax compliance.

5. Research design

The study employed the cross-sectional survey and correlational design as employed by Khozen and Setyowati (Citation2023) and Trawule et al. (Citation2022) to gather, analyze, and interpret the data. Our choice of research design was motivated by the research objective that sought to investigate the mediating role of political party affiliation on the relationship between tax knowledge, service quality, and tax compliance. Creswell and Creswell (Citation2017) opine that using a cross-sectional survey design enables the efficient gathering of extensive data from the population in a cost-effective manner. This approach is particularly advantageous as the characteristics of the measured variables are less likely to undergo significant changes during the relatively brief data collection period. Conversely, correlational research entails the examination of two variables to identify and establish a statistically correlated relationship between them (Gadzo et al., Citation2019). The Justification of the correlational design is premised on the quest to examine the statistical relationship between service quality, tax knowledge, and tax compliance, mediated by political party affiliation.

5.1. Population and sampling procedure

Traders occupying various stalls in the Kumasi central market were chosen as the study population. With the focus on political partisanship, these categories of traders were deemed appropriate. The market is estimated to have been occupied by about 10000 stalls and shop owners (Newman & Alvarez, Citation2022). This study applied the non-probability sampling method and adopted the purposive sampling technique. The purposive sampling technique is appropriate when researchers must effectively map samples to the research objective to improve data rigor and trustworthiness ((Thomas, Citation2022). The sample was targeted at informal traders within the market. Informal here refers to traders who have not registered their business with the Registrar General Department and do not have taxpayer identification number (TIN). Most of these individuals are known to have a low level of education. These categories of individuals trade in items and commodities ranging from foodstuffs, clothes, assorted beads, kente, locally manufactured slippers and sandals, toiletries, cooking wares, electronics, cosmetics, stationeries, batik, dressmaking, and jewelry. The study adopted the sample size formula developed by Yamane (Citation1967). EquationEquation 1(1)

(1) depicts Yamane’s formula for sample size calculation.

(1)

(1)

where:

n is the sample size

N is the size of the population

e the level of precision or margin of error.

The sample size was calculated below by employing a precision of 5% (95% level of confidence).

(2)

(2)

A sample of 384 out of a total population of 10000 was deemed appropriate per Yamane’s formula. The sample is also consistent with the study of Field (Citation2013), who recommends that a study of our nature should have a minimum sample size of 384. Regardless, our study gathered data from a total of 450 respondents. To prove the adequacy of our sample size, this current study draws motivation from the propositions of Wolf et al. (Citation2013), who believe a sample size of between 100 and 150 is appropriate when using the SEM.

5.2. Data collection instrument and measurements

The study utilized a structured questionnaire with predetermined response options, incorporating a scale adapted from established and validated measures. This type of questionnaire employs a fixed set of closed-ended questions with predetermined response options, facilitating a straightforward and consistent approach to data collection (Blair et al., Citation2013). The questions were carefully crafted to address specific research objectives, ensuring each participant is presented with the same set of inquiries. This uniformity enhances the reliability and comparability of the gathered data. They enable researchers to efficiently gather and analyze data, making them a valuable instrument for understanding patterns, trends, and relationships within a given research context. The study administered a printed questionnaire through the survey method to collect data from informal sector traders. The questionnaires were administered by a team of 4 (four) trained national service personnel at the Ashtown small tax office. Taxpayers were assured of the confidentiality of any information they gave out as it was strictly for academic purposes. The team members assisted taxpayers in filling out the questionnaire clearly and objectively. These approaches sought to eliminate missing data issues and ensure complete accuracy. The questionnaire was divided into two parts. The first part contained statements about the demographical characteristics of respondents, whereas the second part contained statements about tax compliance variables. All constructs were measured using a 5-point Likert scale to test the research hypothesis. Respondents were allowed to select appropriate numbers ranging from ‘strongly disagree = 1 to strongly agree = 5’ (see Appendix A). In total, the team took four weeks to administer the questionnaires. presents the study variables and their measurements, including their respective sources. The study employs four main variables, aside from the demographics, which are used as control variables to answer the research questions as explained below;

Table 1. Variables measurement.

Tax knowledge: As an independent variable, tax knowledge may refer to an individual’s or entity’s understanding of various taxation-related aspects. Recent global research indicates that the most significant factor influencing taxpayers’ compliance behavior is their level of tax knowledge. Within the context of operationalization, tax knowledge was operationalized by general tax knowledge gleaning on the affect balance from partisanship (Fauziati et al., Citation2020; Hunt et al., Citation2019).

Service quality: As an independent variable, service quality encompasses how tax authorities and government offer convenient and equitable service to taxpayers. On a governmental tone, the effective redistribution of infrastructure influences how individual taxpayers respond to compliance. Service quality is therefore operationalized by general knowledge of infrastructure provision and service delivery of tax authorities (Abasili & Akinboye, Citation2019; James Alm & Gomez, Citation2008).

Tax compliance: Tax compliance as the dependent variable is attributed to the degree to which individuals or entities adhere to the government’s tax laws and regulations, voluntarily or unforcefully. For our research objective, compliance is operationalized by the induced voluntary payment of tax obligations (Ayuba et al., Citation2018; Lozza et al., Citation2013; Musimenta, Citation2020).

Political party affiliation: Political party affiliation relates to an individual’s formal association or alignment with a specific political party. It signifies the person’s support for the values, policies, and candidates endorsed by that party, which sometimes transcend to partisanship. Party affiliation is operationalized by partisanship (Bodea & LeBas, Citation2016; Hunt et al., Citation2019).

5.3. Pre-test

Specific instruments were created using validated scales and constructs to ensure content validity. A pre-test was conducted to address potential readability issues, and feedback was used to adjust wording and format. A pilot study was conducted to confirm readability and assess the response rate. Feedback from the pilot study led to removing specific instruments to improve readability. Opinions from four experts were taken to enhance comprehensiveness. Two were industry professionals with over ten years of experience in the topic, and two were academic researchers with over ten years of experience. Ultimately, 20 instruments were prepared through a step-by-step rectification process, with details provided in the Appendix.

The reliability of the questionnaire was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha, which yielded a reliability coefficient of 0.833. This coefficient is deemed appropriate for the research as a reliability coefficient of ≥ 0.70 on a range of 0–1 indicates good internal consistency reliability, as recommended by Adamson and Prion (Citation2013) and Ursachi et al. (Citation2015). To conduct the pilot test, only a fraction of the actual sample size, 20%, was selected as participants. Following Johanson and Brooks (Citation2010) recommendation, recruiting a sample size of 10–20% of the actual study’s sample size is sufficient for a pilot test. The instrument’s internal consistency, reflecting its reliability, was measured using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. A few weeks after the pilot testing of the instruments, the actual data collection commenced. presents the detailed subscales of Cronbach’s alpha.

Table 2. Reliability of the instrument.

5.4. Common method biased test (CMB)

The common biased method is a predominant issue in most survey research. As the name implies, this bias mostly occurs when the same response method measures multiple variables within a single survey, leading to spurious relationships among the variables (Ketokivi, Citation2019). One cannot overwrite how detrimental this common bias issue affects the validity of a study. This current research employs the 5-point Likert scale to measure the dependent and independent variables (hence the presence of common bias). To statistically detect and control for the common method bias (CMB), several proponents have mentioned the variance inflation factor (VIF), Harman’s single-factor test, and the common latent factor technique as reliable diagnostic tests. The PLS-SEM can incorporate control variables to control for a common method (Maheshwari & Kha, Citation2022). The current research employs participants’ gender, age, education, and salary as a control variable to help control the common method bias. By controlling for these demographic variables, the research seeks to reduce the potential impact of common method bias on the study’s findings. Using control variables is a common statistical technique to increase a study’s internal validity and ensure that any observed effects are attributable to the intended independent variables rather than extraneous factors.

5.5. Data analysis

For a more robust data analysis and results, the Partial Least Square Structural Equation Model (PLS-SEM) was used to test the study’s hypotheses. Judging from the distribution of our research data, the PLS-SEM was much more appropriate as it makes no assumptions concerning how data should be distributed. Also, the PLS-SEM is considered to better handle both reflective and formative measurement models without requiring strict assumptions about their nature and relationships with other variables, such as those of the current study. As a second-generation multivariate method of data analysis, the Partial Least Square Structural Equation Model (PLS-SEM) tends to provide both direct and indirect impacts on interrelated research variables. This makes it more ideal and preferred to multiple regression. As a primary advantage, the PLS-SEM has the greatest effectiveness in measuring complicated model relationships between latent variables in small and moderate samples, such as tax compliance, service quality, tax compliance cost, tax knowledge, and political affiliation (Rasoolimanesh et al., Citation2021). Thus, the PLS-SEM provides the best avenue to explore the complexity of the association between tax compliance, tax knowledge, political party affiliation, and tax service quality, as illustrated in with a detailed representation of the model using Smart PLS-4.0.

6. Empirical results and discussions

6.1. Research participants

With regards to the gender of the respondents involved in the study, the results showed from the findings that 74% of the traders at the Kejetia market engaged in the study were females (n = 333), while 26% were male (n = 117). This affirmed female dominance in the Ghanaian markets. The study found a significant difference between male and female traders on tax compliance in Ghana (t (450) = 2.12, p= .002, two-tailed), as seen in .

Table 3. Respondents’ demographics.

further revealed that the majority (n = 187) of the traders at the market fall within the age range (22–35 years), representing 42% of total participants, indicating the majority of the active force are in this market. This was followed by traders (n = 128), representing 28% aged 36 to 45 years. The study found that a few traders (n = 66) were above 66 years. We further investigated whether age matters in terms of tax compliance among traders in Ghana. There appears to be a significant difference between traders’ ages and their perceived tax compliance in Ghana. This was amply shown in their statistics (t (450) = 3.03, p= .001, two-tailed). The study further analyzed traders’ educational qualifications. As seen in , most respondents (n = 259) had acquired a High school Examination certificate. Only a few traders had tertiary degrees, representing 15% of the respondents. Further analysis of the educational level demography revealed a significant difference in traders’ tax compliance level (t (450) = 2.016, p= .002, two-tailed). The percentage distribution of the estimated monthly salary also shows that 40% of the respondents are in the 1201 to 1800 cedis category, representing the salary range with the highest percentage.

6.2. Descriptive statistics

Before proceeding with structural equation modeling, it is essential to ensure that the normality assumption is met. Normality refers to a symmetrical curve defined by the mean and variance parameters. It is widely acknowledged that larger sample sizes tend to approximate normality. Most statistical tests rely on the normality assumption, and parametric tests are specifically designed for data that follow a normal distribution. Researchers typically examine the data for outliers and missing values to ensure normality, a prerequisite for multivariate data analysis. The descriptive statistics for the study are presented in . Demir (Citation2022) states that assessing normality alone is insufficient; skewness and kurtosis values should also be investigated. Skewness and kurtosis tests are applied to each metric variable’s distribution outline to identify deviations from normalcy. Positive skewness suggests a left-skewed distribution, while negative skewness represents a right-skewed distribution. Positive kurtosis values indicate a peaked distribution and negative kurtosis values indicate a flat distribution. Hair et al. (Citation2010) suggest significant values for evaluating skewness and kurtosis, and after analyzing the data, it was found suitable for conducting the PLS test.

Table 4. Descriptive statistics.

6.3. Multicollinearity and autocorrelation

Multicollinearity is among the preliminary issues affecting the accuracy and consistency of results in PLS-SEM. In our study, we took steps to evaluate these issues by examining the correlation matrix values for each construct in . The correlation matrix in reveals significant relationships among various constructs. Notably, higher education positively correlates with age, while income is negatively associated with education. Political affiliation shows a positive connection with age. Service quality is positively correlated with gender and strongly with tax compliance. Tax knowledge is positively associated with income and strongly with service quality. These findings suggest complex interdependencies between demographic factors, political affiliation, and constructs like service quality and tax compliance, providing valuable insights for further analysis and interpretation in the context of the study. The study’s examination of multicollinearity and autocorrelation found no noteworthy issues, affirming the robustness of the results (Sarpong et al., Citation2023)

Table 5. Correlation matrix.

6.4. Validity and reliability

In this study, we used several measures to assess the convergent validity of our constructs (TK, SQ, PA, and TC) based upon indicators such as factor loading (FL), Cronbach’s alpha (CA), composite reliability (CR), rho ACP, and the average variance extracted (AVE) as seen in . We found that most constructs met or exceeded the minimum threshold values for convergent validity, indicating that the items measured the same underlying construct.

Table 6. Results of validity and reliability of items constructs.

Firstly, we evaluated the content validity of each instrument by estimating the loading factor (LF). All the estimated LF values exceeded the lowest acceptable value of 0.7, indicating that the instruments had sufficient content validity. Secondly, we assessed the validity, reliability, and internal consistency of each construct using the average variance extracted (AVE), composite reliability (CR), and Cronbach’s alpha (α). All estimated values were within the allowable range, with all AVE values higher than the lowest permissible value of 0.566, ranging from 0.614 to 0.664. These findings indicate that our PLS-SEM model has high validity and reliability, with minimal concerns regarding multicollinearity or autocorrelation. The study further analyzed the impact of multicollinearity on coefficient variance using VIF values, as indicated in . The results suggest that the VIF values ranged between 1.202 and 2.563, below the threshold of 5, supporting the idea that multicollinearity did not significantly affect the model.

To assess the distinctiveness of each construct, a discriminant validity analysis was conducted using both the Fornell-Larcker criteria and the Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratio. The Fornell-Larcker criteria evaluate whether each construct’s average variance extracted (AVE) exceeds the shared variance between that construct and other constructs in the model. The results of the study, presented in , revealed that all constructs met the Fornell-Larcker criteria, demonstrating that each construct is distinguishable from the others. Per the Fornell-Larcker criterion, each construct’s square root of the average variance recovered should exceed its maximum correlation with any other construct (Henseler et al., Citation2015). The HTMT ratio was also examined to verify the discriminant validity analysis further. displays the results of the Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio analysis, which measures discriminant validity. This ratio examines the correlation between indicators within a single construct or the average correlation between indicators across constructs. The HTMT score is commonly used to estimate the correlation between constructs and is calculated using the absolute values of the correlations. When the HTMT score is less than 0.90, it indicates that discriminant validity has been established between two reflective notions. In , the data reveals a significant level of discriminant validity, as evidenced by the HTMT scores below 0.90.

Table 7. Discriminant validity.

6.5. Measure of the model: Model fitness and significance

The model’s fitness was evaluated through multiple indices, including Chi-square ratio (X2-ratio), Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), Normed Fit Index (NFI), and SRMR. Model fitness refers to how well the model fits the observed data using Structural Equation Modeling. According to Perry et al. (Citation2015), suitable indices for determining model fitness include RMSEA, CFI, and SRMR when presenting findings for structural equation models. A model is considered fit if the X2-ratio is less than three and the TLI is greater than 0.90. RMSEA and SRMR should be less than 0.05 for a good model fit and less than 0.08 for an acceptable model fit. The GFI and NFI must be more than 0.95 for a successful model fit. The model met all the necessary fitness indicators, as shown in .

Table 8. Model goodness and significance.

Our model’s significance was measured using R-squared, Adjusted R-squared, F2, and Q2, which may vary depending on the study design and PLS-SEM software utilized. We used adjusted R2, Q2, and F2 metrics to assess the model’s efficacy. Using bootstrapping techniques, summarizes the statistical analysis findings of the relationship between endogenous and exogenous components. The strength of the relationship between model components was evaluated by interpreting t-statistics and the correlation between the constructs by thoroughly analyzing the path coefficient values. The t-statistics must be greater than 1.96 to be deemed significant (Pew Tan et al., Citation2007).

Upon completing the assessment of the measurement model’s validity and reliability, we used structural model analysis to estimate the explanatory power of our conceptual model and evaluate our hypotheses. The coefficient of determination (R2) was employed to measure the research model’s explanatory capability, while path coefficient values were utilized to evaluate the strength of the cause-effect relationship. The bootstrapping approach with a 95% confidence level was adopted to assess each step’s impact. Additionally, the t-test was utilized to ascertain the statistical significance of path coefficients. The relationship strength between the two variables was determined using the effect size, a statistical parameter. The effect size results are presented in , indicating that tax knowledge, service quality, tax compliance cost, and political affiliations significantly impact tax compliance. Moreover, the study revealed that the explanatory variables in tax compliance possess predictive relevance, as evidenced by a Q2 value exceeding 0. Additionally, the results obtained from the blindfolding process confirmed that the structural model is characterized by predictive relevance.

6.5.1. Hypothesis testing

Four main hypotheses guided the study. Three main models were constructed to investigate the relationship between tax knowledge, tax service quality, and political affiliation on tax compliance, as presented in . The study adopted mediation tools to analyze the mediation role of political affiliation on the relationship between tax knowledge and service quality on tax compliance in Ghana.

Table 9. Hypothesis testing.

To enhance the model’s internal validity and reliability, Model 1 revealed that participants’ age, gender, and income level were important control variables on the impact of tax knowledge, service quality, and political affiliation on tax compliance. Model 1, which includes control variables, reveals significant associations between certain demographic factors and tax compliance (TC). Specifically, age exhibits a positive relationship with tax compliance (β = 0.016, t = 1.105, p < 0.05), indicating that age as a demographic trait matters for tax compliance. Education also positively impacts tax compliance (β = 0.073, t = 1.255, p < 0.05). On the other hand, income level demonstrates a negative association with tax compliance (β = -0.013, t = 0.638, p < 0.05), suggesting that individuals with lower income levels exhibit higher tax compliance. Gender does not significantly influence tax compliance (β = 0.022, t = 0.220, p < 0.05). Overall, the control variables provide insights into the model’s demographic factors that affect tax compliance.

Several key findings emerge in Model 2, which explores the direct effects based on two of our hypotheses (H1a and H2a). Firstly, Tax Knowledge (TK) exhibits a positive association with tax compliance (TC) (β = 0.067, t = 1.836, p = 0.004). This suggests that taxpayers are more likely to comply when they possess knowledge of tax laws and regulations, viewing tax payment as a civic duty. In Ghana, government efforts, such as the national tax campaign and social media advertisements, have boosted compliance. Specifically, within our study area, regular meetings between tax authorities and Kejetia market traders to educate them on tax laws have positively influenced compliance. This finding aligns with the study of Musimenta (Citation2020) in Uganda and similar research in Indonesia, Ababio and Gnonsio Mangueye (Citation2021) in Ghana, and Kaghazloo and Borrego (Citation2022) in Iran, all supporting the positive relationship between tax knowledge and tax compliance. Notwithstanding the consistency of the above literature with our study findings, others deviate from the findings of our study. Studies of such include that of Natariasari and Hariyani (Citation2023), which revealed no significant relationship between tax knowledge and tax compliance. In addition to the previously provided comparative explanations for the study’s outcomes, one can logically infer the significance and validity of the findings.

Within the theoretical framework, an individual’s grasp of any subject matter is intricately linked to the concept of trust, as delineated by the perspective of the slippery slope framework and social identity theory. This theoretical lens posits that trust is foundational in how individuals assimilate and interpret information. In the context of our study, we delve into the exploration of trust, specifically concerning political party affiliation, offering a unique angle to understand how individuals actively pursue information. This investigation sheds light on how trust influences their willingness to seek tax knowledge and, consequently, their depth of understanding regarding specific fiscal policies. Sakirin et al. (Citation2021) study significantly contributes to this discourse, providing valuable insights into the intricate relationship between trust and political party affiliation in the context of tax knowledge-seeking behavior. Their findings serve as a crucial piece of empirical evidence, enriching our study’s framework and contributing depth to our understanding of trust’s role in shaping information-seeking behavior. Furthermore, empirical support from other studies, such as Saad (Citation2014) research in New Zealand and Lozza et al. (Citation2013) investigation in Italy, adds additional layers of theoretical backing to our study. These studies offer valuable insights into the complex connections between trust, political affiliations, and the proactive pursuit of knowledge.

Service Quality (SQ) positively impacts tax compliance (β = 0.103, t = 5.512, p = 0.000), suggesting that improved service quality is associated with increased tax compliance. In Ghana, taxes form a major source of revenue and are mostly used to provide infrastructure to the populace. As such, enhanced compliance will mean increased tax revenue. Individuals’ perception of their community benefiting from social amenities greatly influences their compliance level (Ayuba et al., Citation2018). The renovation of the market easing trade activities could be among the reasons for the outcome of our study. Over the years, there has been improved service quality from tax authorities within the jurisdiction of the market, creating a welcoming environment for taxpayers, which is also a possibility that backs our findings (Bani-Khalid et al., Citation2022; Seralurin et al., Citation2021). Although complete satisfaction remains a goal, these commitments foster a positive shift in taxpayers’ attitudes toward compliance. However, Sebele-Mpofu (Citation2020) presents contrasting governance impacts on compliance, and Taing and Chang (Citation2021) find no significant relationship between service quality (governance) and tax compliance. While the research highlights the potential for SQ improvements to enhance compliance, it acknowledges the complexity of the governance-tax compliance nexus (Savitri & Musfialdy, Citation2016). Compliance with tax within the Ghanaian tax environment has existed for decades, with successive governments developing several measures to address it. The country suffers from basic infrastructural facilities, which influence the tax compliance attitude of certain jurisdictions with poor facilities. The service paradigm, an extension of the slippery slope framework, provides a delicate insight into our findings. The positive significant relationship between service quality and tax compliance adds more evidence to this paradigm. Distinctively, the service paradigm goes beyond considerations of trust and power, proposing that taxpayers are not exclusively rational actors motivated solely by utility maximization. Instead, they anticipate equitable treatment and the provision of high-quality public services as reciprocation for their contributions to taxes (da Silva et al., Citation2019).

In model 3, the mediating effect of political party affiliation on the relationship between tax knowledge and service quality on tax compliance supports our proposed hypotheses that political party affiliation indirectly and significantly influences the positive relationship between tax knowledge and service quality. The findings are noteworthy, with TK demonstrating a positive indirect effect on TC through its influence on PA (β = 0.610, t = 3.199, p = 0.001). Similarly, SQ positively impacts TC indirectly through its impact on PA (β = 0.420, t = 2.579, p = 0.010). These findings were of significant interest to our study due to the country’s domineering nature of partisan politics. The study of Sritharan and Salawati (Citation2019) corroborates our results. For tax knowledge, presented positively significant results for political affiliation as a mediation variable. Political affiliation connotes trust in authorities, and with authority comes power (Best et al., Citation2003). Power can also fuel trust.

Where there is trust, individuals become familiar with various aspects of governance and matters of national concern, including knowledge of tax. The degree of patronage with which these taxpayers participate in tax campaigns and exercise reflects their political ideology, increasing compliance. To ensure the highest votes retain power, political parties tend to provide adequate infrastructure and service to such vicinities (Patay et al., Citation2023). The government becomes perceived as accountable; taxpayers increase tax compliance to help their party succeed. The effect of increased compliance will be increased tax revenue for national development. There have also been instances when politically inclined taxpayers’ complaints have led to the transfer of tax officials perceived as corrupt and replaced with diligent ones. As taxpayers perceive their grievances have been attended to on the probability of political affiliation, compliance becomes voluntary and induced as tax officials are perceived to render quality services. The findings of our study are consistent with the studies of DeZoort et al. (Citation2018) and Okafor et al. (Citation2022).

Politically, individuals are affected by the ‘affect balance’ syndrome, which according to Hunt et al. (Citation2019), influences major decisions of taxpayers judging from loyalty to their party. This affect balance is likely to produce an overall negative level of compliance to the left-wing party affiliation, which is also influenced by partisanship. This negative trend will not auger well for the country as it will constantly lead to an increased level of unequal distribution of infrastructure and a decrease in tax revenue. Political affiliation studies as a mediating variable have been scant, and no empirical evidence exists within the African context, hence the limited empirical backing. In Uganda, the findings of the study of Nkundabanyanga et al. (Citation2017) explained how the distribution of public expenditure on infrastructure significantly influences tax compliance attitudes among citizens.

6.6. Robustness checks

The study meticulously ensured the reliability and depth of its findings by implementing several methodological strategies, particularly in investigating the intricate relationship between tax service quality, tax knowledge, and tax compliance mediated by political affiliation among informal sector traders in the Kejetia market. Respondents were systematically categorized based on key demographic variables to capture the multifaceted nature of this relationship. First, age served as a pivotal factor, with participants divided into two distinct groups: the young-tax-compliant group (ages <35 years) comprising 187 individuals and the old-tax-compliant group (ages >35 years) consisting of 263 respondents. This segmentation facilitated a comparative analysis of tax compliance behavior across different age brackets, shedding light on potential generational differences in attitudes toward tax compliance.

Furthermore, educational level and monthly income were critical dimensions examined in the study. Participants were stratified based on their educational attainment, with 327 respondents classified as literate (possessing high school education and above) and 123 as illiterate (lacking formal education). Additionally, monthly income levels were considered, with 102 respondents identified as high-income earners (with monthly income above 1800 GH cedis) and 348 respondents characterized as low-income earners (earning less than 1800 GH cedis per month). This meticulous categorization allowed for a nuanced exploration of how educational background and income levels influence tax compliance behaviors among informal sector traders, thereby enriching the depth and breadth of the study’s findings and ensuring a comprehensive understanding of the dynamics at play within the Kejetia market. provides a comprehensive robustness check based on respondents’ demographic classifications. The findings reveal that age positively correlates with tax compliance (TC) for young and old taxpayers.

Table 10. Robust check based upon respondents’ demographic classification.

Additionally, education positively influences tax compliance for the educated group, while income level positively impacts tax compliance, specifically among low-income taxpayers. Examining the direct effects, tax knowledge (TK) positively impacts tax compliance for both the young and high-income segments. On the same note, service quality (SQ) positively affects tax compliance for the young, high-income, and educated groups. Analyzing the mediation effects, the indirect influence of tax knowledge (TK) through political affiliation (PA) is positively associated with tax compliance for the young and low-income cohorts. Similarly, the indirect impact of service quality (SQ) through political affiliation (PA) is positive for the young and high-income groups. These findings validate the ascribed affect balance individuals derived from political party affiliation, which has increased the occurrence of partisanship activities. Overall, the model accounts for a substantial proportion of the variance in tax compliance across diverse demographic groups.

7. Conclusion and limitations

The study purposely investigates the mediating role of political affiliation on the relationship between tax knowledge, service quality, and tax compliance premised on the Social Identity Theory and Slippery Slope Framework. The study used a questionnaire to gather data from 450 respondents (taxpayers). The collected data was analyzed with SmartPLS version 4. The first part of the results reaffirms the prior research hypothesis that tax knowledge and service quality (tax authority and government) positively influence tax compliance. Also, the result of the mediating variable, "political affiliation", is positively related to tax compliance and also provides significant positive results as a mediator based on the effect of partisanship and affect balance.

Considering how partisan politics plays an active role in policy implementation and compliance, it is quite surprising that the influence of political affiliation has received no attention in tax compliance literature in Ghana. The results of our study provide key practical policy implications that have the potential to increase compliance to raise government tax revenue. First, the sampled taxpayers’ compliance nature indicates enhanced revenue from these jurisdictions, while the opposite may be said of other jurisdictions with fewer affiliations to the sitting government. Compliance with tax is a national fiscal policy aimed at shaping a country’s economy and should not be politicized. As such, governments should consider implementing targeted enforcement strategies that focus on the entire population. There have been several instances where specific communities have allegedly perceived particular political parties as uninterested in developing their vicinities. If these allegations prove right, tax compliance will likely be an issue for taxpayers within such communities, which will not auger well for revenue generation and economic growth. The government should not consider those areas that are devoid of their votes as aliens but as a citizen who needs to understand the reasons for paying taxes. There is also the need to leverage the influence of political parties and their leaders to encourage their party affiliates to comply with tax regulations. For example, political parties could prioritize universal tax compliance as part of their messages delivered occasionally. Leaders of political parties could also use their platform to advocate publicly for tax compliance and encourage their supporters to pay their taxes. The interaction between trust and power is quite complex; therefore, achieving or maintaining a high level of compliance in a social system is like operating on a slippery slope.

Moreover, it is imperative to establish robust educational and outreach initiatives to effectively bridge the longstanding partisan politics gap that has persisted for years. Ghanaian laws rightfully endorse freedom of association, allowing individuals to align themselves with their chosen political party. It is essential to dispel the misconception that being a member of the opposition automatically equates to being an adversary of the ruling government. In reality, all citizens play a vital role in the collective effort of nation-building. Recognizing the urgency of the matter, there is a pressing need for comprehensive civic education to instill a strong sense of civic duty among the populace. This educational endeavor should particularly emphasize the detrimental consequences of partisan politics, including its contribution to community underdevelopment, abandoned projects, and the reduction of total tax revenue. Activists, as influential voices in society, should take on the responsibility of regularly conducting civic education sessions. These sessions can serve as a platform to elucidate the broader implications of partisan politics, fostering a more informed and engaged citizenry. Activists can contribute significantly to promoting a more politically aware and responsible society in Ghana by actively participating in such educational efforts. Going forward, the concept of taxation ought to be incorporated into the curriculum across all educational tiers, ranging from primary to secondary schools and extending up to the university level. The focus should be on cultivating a culture of voluntary tax compliance. Presently, taxation is confined to being a subject within the realm of economics, primarily for students with a business orientation during high school and university studies. This limited approach overlooks the significance of imparting taxation knowledge to students at lower academic levels and across diverse fields, even though these foundations are integral to the understanding and application of tax principles.