Abstract

Impulse buying decisions are influenced by external stimuli, which give rise to internal stimuli to encourage impulsive buying decisions. Previous research has revealed that external stimuli such as popularity and scarcity claims encourage impulse buying decisions. However, the influence of popularity and scarcity on impulsive buying decisions should involve the influence mechanism of the urge to buy impulsively as a mediator. Validating the role of the urge to buy impulsively as a mediator on the influence of popularity and scarcity claims on impulsive buying decisions is the primary motivation for this research. This motivation is based on the consideration that impulse buying decisions provide economic benefits for sellers, so exploring what external and internal factors can influence impulse buying decisions is essential. The results of testing and analyzing using Partial Least Squares (PLS) for a more robust model on 310 respondents validate that the urge to buy impulsively mediates the influence of both popularity and scarcity claims on online grocery impulse buying decisions.

Introduction

Consumers expect flexibility and convenience in the shopping process, including on-time delivery service, because they want to make sure the products they buy are fresh (Singh, Citation2019). The lack of flexibility and convenience will cause consumers to switch purchasing behavior (Dholakia et al., Citation2005; Singh, Citation2019). In terms of purchasing grocery products, consumers still rely on direct purchases through offline retail stores compared to purchases through online retail stores. In buying groceries, consumers want to see, select, and buy essential food products directly (Huyghe et al., Citation2017). Practically, in the purchasing process via online media, consumers tend to rely on external stimuli, one of which is visually appealing external stimuli, such as persuasion claims (Paul et al., Citation2022). There are two types of persuasion claims, namely scarcity claims and popularity claims (Jeong and Kwon, Citation2012). Previous research focused more on examined the influence of persuasion claims on purchase intention (Jeong and Kwon, Citation2012; Xu et al., Citation2021; Teubner and Graul, Citation2020). Meanwhile, this research examines the influence of persuasion claims on impulse buying decisions. One of the reasons impulse buying decisions are the focus of this research is because, from the company’s point of view, impulse buying decisions provide economic benefits for sellers (Hausman, Citation2000).

Previous studies examined the influence of external stimuli on the urge to buy impulsively. Through the mediator of impulse buying tendency, social commerce can give rise to UTBI (Herzallah et al., Citation2022; Chung et al., Citation2017; Wells et al., Citation2011; Liu et al., Citation2013). Meanwhile, previous research also stated that the urge to buy impulsively positively influences impulse buying (Beatty & Elizabeth Ferrell, Citation1998; Bao and Yang, Citation2022; Zhang et al., Citation2018; Leong et al., Citation2018). Individuals with a good and positive mood when shopping tend to have an increased urge to buy impulsively (Bao and Yang, Citation2022). However, although several previous studies have produced findings of a positive relationship between external stimuli on UTBI and the relationship between UTBI and impulsive buying decisions, not many studies have examined the influence of external stimuli on impulsive buying decisions with UTBI as a mediator, including external stimuli in the form of popularity and scarcity claims.

Previous studies mainly tested UTBI as a consumer response (dependent variable) due to the influence of external stimuli by including other mediator variables such as impulsiveness (Wells et al., Citation2011; Zhang et al., Citation2006), impulse buying tendencies (Zhang et al., Citation2006) or shopping values (Chung et al., Citation2017). However, research by Badgaiyan and Verma (Citation2015) shows that UTBI positively influences impulse buying behavior, while sales promotion, store environment, and store music also positively influence UTBI. In this case, UTBI is a mediator in the influence of external stimulus on impulse buying behavior. The role of UTBI in impulse buying decisions is quite essential. When exposed to external stimuli, consumers will feel a strong urge to have a product immediately and even imagine owning it (Rook, Citation1987). The UTBI will encourage consumers who do not have a purchase plan to suddenly, intensely, and immediately make a purchase decision (Setyani et al., Citation2019). One of the sellers’ goals in applying external stimuli, apart from causing arousal, is to cause UTBI, which impacts impulse buying decisions. Apart from that, not many have focused research on the context of purchasing grocery products via online media.

Age and gender are essential personality traits that can predict a consumer’s impulse buying decisions (Amos et al., Citation2014). However, not many studies that examine UTBI and impulse buying decisions have included age and gender as control variables, both to examine the influence of age and gender on UTBI and impulse buying decisions and to test the robustness of the model. Apart from that, there are still inconsistencies in testing the influence of age and gender, especially on impulse buying decisions.

Based on the identified theoretical gaps and the problems that occur in practical aspects, this study aims to answer three research questions as follows: (1) Does UTBI play a role in mediating the influence of scarcity and popularity on impulse buying decisions? (2) What is the role of gender and age in influencing persuasion claims on impulse buying decisions with UTBI as a mediator variable? This research contributes to the development of theoretical and practical contexts. The contribution to the development of the theory is the validation of antecedent factors that can influence impulse buying decisions in the form of persuasion claims, with the UTBI as a mediator variable. Meanwhile, the contribution to the practical context is in the form of a mechanism for enforcing persuasion claims in the context of grocery products sold in online media.

Literature review

Arousal theory

Arousal is defined as the degree to which a person feels active, stimulated, happy, and alert in a situation (Mehrabian and Russell, Citation1974; Hashmi et al., Citation2020; Guo et al., Citation2017) There are two types of arousal, namely, competitive arousal and excited arousal. Competitive arousal can arise due to competition, time pressure, and the desire to win (Ku et al., Citation2005). Wu et al. (Citation2021) explain that competitive arousal is when different factors (e.g. perceived rivalry and time pressure) fuel arousal, which impacts a person’s decision.

Meanwhile, excited arousal is a feeling of joy that arises due to high levels of arousal combined with high levels of pleasure and joy (Guo et al., Citation2017). Environmental cues such as aroma, color, and music can activate excited arousal (Guo et al., Citation2017; Wu et al., Citation2008). Individuals in a good mood and with positive feelings when they shop are more likely to have an increased urge to impulse buy (Beatty & Elizabeth Ferrell, Citation1998; Bao and Yang, Citation2022). Consumers’ cognitive and affective reactions (consumer’s state of mind) are aroused due to the influence of external stimuli that cause UTBI (Cui et al., Citation2022), which leads to impulse buying behavior (Mohan et al., Citation2013; Saad and Metawie, Citation2015).

The previous research showed the role of UTBI as a mediating variable between external stimulus and impulse buying behavior. Previous studies explored the role of UTBI as a mediating variable in the store environment and external stimulus for impulse buying decisions (Zafar et al., Citation2023; Djafarova and Bowes, Citation2021; Setyani et al., Citation2019). Specifically, in a flash sale event, impulse buying is influenced by the existence of arousals that arise due to the influence of scarcity claims (Lamis et al., Citation2022).

UTBI and impulse buying decisions

Impulse buying decisions are sudden, immediate, non-planned purchase decisions (Rook and Hoch, Citation1985). One characteristic of an impulse buying decision is the influence of external stimuli (Mattila & Wirtz, Citation2008; Piron, Citation1991). Online impulse purchasing is defined as a mental response to external stimuli that exist in online media without any previous desire to make purchases (Yue et al., Citation2023). The UTBI and impulse buying differ entirely (Beatty & Elizabeth Ferrell, Citation1998), because the UTBI arises from exposure to external stimuli before impulse buying occurs (Zheng et al., Citation2019).

Specifically, the UTBI is described as a desire that consumers have when they see a product, model, or brand in a retail store (Rook, Citation1987; Badgaiyan and Verma Citation2015; Utama et al., Citation2021). Impulse buying often occurs and involves two processes, namely desire and behavior. Consumers will usually be urged to purchase something and then show actual behavior, one of which is impulse buying (Beatty & Elizabeth Ferrell, Citation1998; Bao and Yang, Citation2022).

When consumers explore a store and are exposed to multiple external stimuli, there will be a greater desire to purchase at that time, reinforcing the notion that impulse buying occurs because of a UTBI (Beatty & Elizabeth Ferrell, Citation1998; Foroughi et al., Citation2013). External stimuli in the form of online bundle promotions and contextual interactions have a positive effect on the emergence of the UTBI, which in turn influences impulse buying decisions in consumers Zafar et al. (Citation2021). The UTBI can also be categorized as an emotional aspect influencing impulse buying decisions (Bao and Yang, Citation2022). This urge prevents consumers from looking for alternative products, resulting in decisions to buy a product immediately (Lee et al., Citation2009). Thus, the authors propose that:

H1. The urge to buy impulsively (UTBI) positively influences impulse buying decisions.

The effect of popularity claims on impulse buying decisions

Two theories exist as the main foundation of popularity claims, namely, the herding theory and the bandwagon effect theory. The bandwagon effect theory describes an individual tendency to select something that is also the decision of many other individuals (Leibenstein, Citation1950; Nelson, Citation1974; Sundar et al., Citation2008). The herding theory reveals that individuals tend to do something that is done by many people (Banerjee, Citation1992). Psychologically speaking, consumers’ perception of their rights as individuals could be affirmed by seeing similar actions carried out by others, which is supported by social comparison theory (Inthuyos et al., Citation2021).

Popularity claims emphasize the number of individuals who give a positive judgment; the more consumers who give a favorable judgment of a product, the more convinced other consumers are to buy the same product (Huang and Chen, Citation2006; Bonabeau, Citation2004; Jeong and Kwon, Citation2012). Therefore, these products have become popular and are talked about by many people (Jeong and Kwon, Citation2012). If there are many buyers, it serves as a social validation (Cialdini, Citation2007). Humans tend to imitate other human behavior because humans not only want to be accepted but also for security (Huang and Chen, Citation2006). Claims or information that states the number of previous buyers can influence purchase intention (Chen et al., Citation2016). Many buyers become an assessment of the product for other consumers, influencing the desire to buy (Hellofs and Jacobson, Citation1999; Huang and Chen, Citation2006). A large group of buyers who simultaneously buy the same product creates a shopping frenzy among other buyers (Park et al., Citation2020).

Therefore, marketers need to take advantage of the power of the crowd (Huang and Chen, Citation2006). In the context of the online environment, three aspects can shape herding behavior, namely: 1). Sales volume, 2). Customer reviews, and 3). Consumer recommendation. Premises such “only 5 of 10 left”, “User Favorite”, and “Other Recommendations” are applications of popularity claims that are part of herding behavior. Furthermore, the social validation that consumers obtain due to popularity claims creates enthusiasm and pleasure in consumers, which in turn creates an urgency to change systematic information processing into heuristic information processing that increases consumers’ desire to engage in impulse buying (Chan et al., Citation2017; Jeong and Kwon, Citation2012). Thus, the authors propose that:

H2a: Popularity claims positively and directly affect impulse buying behavior.

H2b: Popularity claims positively and directly affect the UTBI.

The effect of scarcity claims on impulse buying decisions

Scarcity claims are another form of persuasion where the number of products or the time to buy a product is limited (Gierl et al., Citation2008). Commodity theory is a theory used to explain the application of scarcity claims. Commodity theory stated that product scarcity will increase the value of a product (Lynn, Citation1991). Apart from that, scarcity will also increase the perception of the quality of a product (Lynn, Citation1991).

Scarcity claims are defined as written statements or visual icons that indicate the quantity or time limit set on the product’s availability (Balachander and Stock, Citation2005). Scarcity claims have been proven to create urgency for consumers to buy more goods, conduct shorter searches, and derive satisfaction from purchased products (Wu et al., Citation2021). Consumers who directly see the availability of goods diminishing and have less time to buy a particular product will feel pressured to buy it right away. The scarcity claim works effectively as a heuristic persuasion that makes consumers value an object (Lee et al., Citation2018). Some individuals often perceive rare objects as valuable because the amount and resources available to obtain them are limited.

Good value and increased perceptions of quality due to scarcity generate enthusiasm and pleasure in consumers that form an urge to change systematic information processing within them into a heuristic information processing that increases consumers’ desire to make purchases impulsively (Lynn, Citation1991; Cialdini, Citation2007; Chan et al., Citation2017; Jeong and Kwon, Citation2012). Thus, the authors propose that:

H3a: Scarcity claims positively and directly affect impulse buying behavior.

H3b: Scarcity claims positively and directly affect the UTBI.

UTBI mediates popularity and scarcity claims on impulse buying decisions

Previous studies examined the influence of external stimuli on the urge to buy impulsively. Through the mediator of impulse buying tendency, social commerce can give rise to UTBI (Herzallah et al., Citation2022); scarcity messages can increase consumers’ perception of utilitarian and hedonic shopping values, which in turn can encourage the emergence of UTBI (Chung et al., Citation2017), visual appeals are also able to cause UTBI (Wells et al., Citation2011; Liu et al., Citation2013) with normative evaluation and instant gratification (Liu et al., Citation2013), while personalized advertising is also able to cause UTBI with impulse buying tendencies as a mediator. Meanwhile, previous research also revealed that the UTBI positively influences impulse buying (Beatty & Elizabeth Ferrell, Citation1998; Bao and Yang, Citation2022; Zhang et al., Citation2018; Leong et al., Citation2018).

Bao and Yang (Citation2022) explained that individuals with a good and positive mood when shopping tend to have an increased UTBI. The connection between previous research regarding the influence of external stimulus on UTBI and UTBI on impulse buying decisions shows that UTBI is a mediator of external stimulus on impulse buying decisions. In the context of purchasing via online media, consumers tend to rely on external stimuli that the eye can identify, including persuasion claims in the form of popularity and scarcity claims.

Popularity claims encourage more individuals to assess a product or service positively. The more consumers give positive assessments, the more consumers believe that the product or service has good quality, Cialdini (Citation2007) says this is social validation. The number of buyers who buy a product or service is the basis for evaluating other consumers regarding that product or service (Hellofs and Jacobson, Citation1999; Huang and Chen, Citation2006). The large number of consumers who buy a product or service creates a shopping frenzy (Park et al., Citation2020), which can lead to UTBI, and UTBI can encourage consumers to decide on impulse buying (Beatty & Elizabeth Ferrell, Citation1998; Bao and Yang, Citation2022; Zhang et al., Citation2018; Leong et al., Citation2018). Thus, the authors propose that:

H4a: UTBI mediates Popularity Claims on Impulse Buying Decisions

Meanwhile, consumers perceive rare products as valuable and good quality products (Lee et al., Citation2018). Scarcity claims have been proven to create urgency for consumers to buy more goods, conduct shorter searches, and derive satisfaction from purchased products (Wu et al., Citation2021). If consumers see a product shortage, they will feel pressured to buy it immediately. The scarcity claim works effectively as a heuristic persuasion that makes consumers value an object (Lee et al., Citation2018). The perception that a product is valuable and has good quality will increase consumer enthusiasm and create excitement and a positive mood (Cialdini, Citation2007; Chan et al., Citation2017; Jeong and Kwon, Citation2012), and a positive mood creates an urge to buy impulsively which in turn encourage impulse buying decisions (Bao and Yang, Citation2022). Thus, the authors propose that:

H4b: UTBI mediates Scarcity Claims on Impulse Buying Decisions

Age and gender as the control variable on UTBI and impulse buying decisions

This research was conducted to test the robustness of the model for the effect of persuasion claims on impulse buying decisions with the UTBI as a mediator variable. Thus, the authors added two control variables to the test in the form of age and gender. Research by Shamim et al. (Citation2024) and Badgaiyan and Verma (Citation2015) found that age and gender differences do not affect UTBI. Meanwhile, concerning impulse buying decisions, previous studies have acknowledged the inconsistencies in the influence of age and gender on impulse buying decisions. The consumer report by Deloitte (Citation2021) states that older consumers are more impulsive than younger consumers. During the COVID-19 pandemic, older consumers learned a lot about online media, including using it for shopping. In addition, older consumers are a generation with a reasonably high value of wealth nowadays, one source of which is their pensions.

However, previous studies show contrasting results; younger consumers tend to be more impulsive than older consumers (Badgaiyan and Verma, Citation2015). More specifically, Bellenger et al. (Citation1978) state that shoppers under 35 are more prone to engage in impulse buying than those over 35 years old. Younger consumers have lower self-control and higher emotions than older consumers (Utama et al., Citation2021). Thus, lower self-control and higher emotions in younger consumers can also lead to a higher UTBI and influence consumers to buy impulsively.

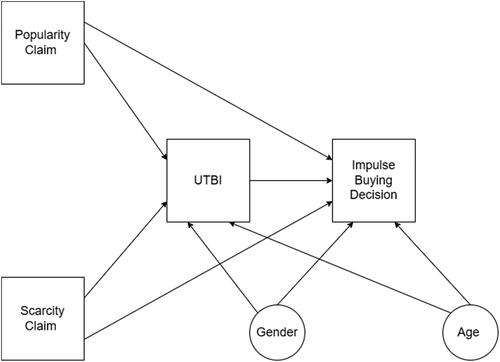

Apart from age, gender is also an essential aspect of personality traits that can predict impulse buying decisions in a consumer. Previous studies have found that women tend to be more impulsive than men (Dittmar et al., Citation1995). Meanwhile, Djafarova and Bowes (Citation2021) confirmed that males have lower impulsivity traits than women, so external stimuli encourage more impulse buying decisions in women. Several studies have found that gender significantly influences impulse buying decisions (Rook and Hoch, Citation1985; Paul and Gutierrez, Citation2004). However, other recent research on the effect of gender on impulse-buying decisions argues that women and men show equal tendencies toward impulse-buying decisions due to social equality (Badgaiyan and Verma, Citation2015). The difference in findings from previous research is one of the fundamental reasons for including gender as a control variable to test the effect of persuasion claims on impulse buying decisions; the overall research model is illustrated in below:

Methods

Respondents’ profile

Data collection for this research was carried out in Indonesia by distributing questionnaires to the Indonesian people in September 2021. Data collection was carried out for two months. The survey with printed images containing the popularity and scarcity claims and no claim adapted by Jeong and Kwon (Citation2012) is distributed through social media, covering potential respondents according to established criteria. In data collection, Jeong and Kwon (Citation2012) used Web pages media to display pages containing content in the form of product images with persuasion claims; then respondents were asked to review the page and answer the question “What Do Customers Utimately Buy After Viewing This Item?”. Jeong and Kwon’s research (2012) became the basis for preparing a questionnaire to measure the influence of persuasion claims in this study, which is why the questions to measure the influence of persuasion claims in this study only consisted of 2 question items. Both questions are the same, only differentiated by the type of each persuasion claim.

The respondents’ criteria include consumers who have purchased grocery products using online media such as websites, mobile applications, and e-marketplaces. After filling in the screening questions, respondents were then asked to fill in questions related to the primary constructs, namely the influence of popularity claims, scarcity claims, the influence of urgency to buy impulsively, and impulse buying decisions. This study determined the sample based on non-probabilistic purposive sampling with specific characteristics (Malhotra and Birks, Citation2007). This research uses multivariate analysis techniques so that the number of respondents 310 meets sufficient criteria because it has exceeded the number of respondents in the formula of 20 x number of variables (Joseph et al., Citation2010). So, the basis for determining the sample = 20 x 6 (6 variables include popularity claims, scarcity claims, urge to buy impulsively, impulse buying decision, age, and gender) = 240, 240 < 310 respondents.

Based on age, the respondents in this study were predominantly female (68%), followed by male (32%). The number of respondents over 35 years of age was higher than respondents aged under 35. This research uses Bellenger et al. (Citation1978) to form the basis for grouping respondents based on age. Respondent under 35 were categorized as young consumers, while respondents over 35 were categorized as old consumers. Therefore, the description of the respondents’ profiles in this study focuses only on the description of the age and gender of the respondents (see ).

Table 1. Respondent profile.

Instrument assessment

The questionnaire is divided into four parts (see ). The first part consists of questions about popularity claims adapted from Jeong and Kwon (Citation2012). The scale used to evaluate questions in the first part is a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). The second part consists of questions about scarcity claims adapted from Jeong and Kwon (Citation2012) and Guo et al. (Citation2017). The scale used to evaluate questions in the first part is a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree).

Table 2. Items descriptive and reliability test results.

The third part includes a question regarding the UTBI developed by Badgaiyan and Verma (Citation2015). The scale used to evaluate questions in the third part is a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). The last part includes two questions about impulse buying decisions developed by Mattila & Wirtz (Citation2008). The scale used to evaluate questions in the last part is a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree).

Validity and reliability tests were carried out on the measurements used in this research. Internal consistency tested using Composite Reliability produces scores above 0.7, indicating high reliability (Hair et al., Citation2019). Convergent validity is checked using the outer loading score of each indicator. All indicators have outer loadings above 0.5, which can be used in further testing (Hair et al., Citation2019). Apart from that, convergent validity is also measured using average variance extracted (AVE). The AVE value in this study exceeds 0.5, which is considered acceptable (Hair et al., Citation2019) (Please see for detailed information). Discriminant validity was tested by looking at the value of cross-loading indicators. Cross-loading indicators show that each item loads the most on its related construct but not on other constructs of interest (Henseler et al., Citation2015). shows that the cross loadings on the assigned constructs are the highest, so the constructs are different from each other.

Table 3. Cross Loading.

As seen in , the HTMT ratio is assessed for each construct, resulting in an HTMT value below the threshold of 0.9, indicating that each construct is different from other constructs (Henseler, et al., Citation2015), except for the scarcity claim variable, which has an HTMT value of 0.983, it is still tolerable because the cross-loading value shows the most extensive loading on its related construct. The results of the correlation analysis presented in show no substantial multicollinearity problems between the constructs because the AVE root in each construct is greater than the correlation value. (Hair et al., Citation2019). Lastly, Harman’s single factor test was conducted to check for the presence of common method bias, which resulted in 45.76% of the variance, indicating the absence of substantial common method variance in the data (Fuller, et al., Citation2016).

Table 4. HTMT Ratio.

Table 5. Mean, Standard Deviation, and Fornell-Larcker.

Hypotheses testing

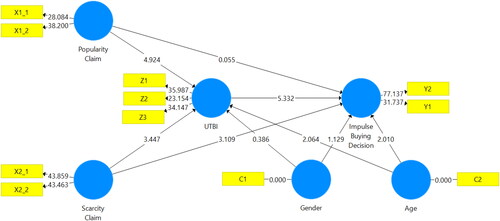

PLS-SEM using Smart-PLS version 3.0 was employed to test the relationship between the variables. The results are presented in . As such, the direct relationship between UTBI and Impulse Buying Decisions is significant (β = 0.326; p = 0.000), hence H1 is supported. The direct relationship between Popularity Claims and Impulse Buying Decisions is insignificant (β = 0.005; p = 0.950), hence H2a is not supported. The direct relationship between Popularity Claims and Urge to Buy Impulsively is significant (β = 0.368; p = 0.000), hence H2b is supported. The indirect relationship testing on the relationship between the influence of Popularity Claims on Impulse Buying Decisions with UTBI as a mediator shows significant results (β = 0.120; p = 0.000). Therefore, H4a is supported. The results of this test confirm the full mediating role of UTBI on the influence of Popularity Claims on Impulse Buying Decisions.

Table 6. Results of hypotheses testing.

The direct relationship between Scarcity Claims and Impulse Buying Decisions is significant (β = 0.258; p = 0.002), hence H3a is supported. The direct relationship between Scarcity Claims and Urge to Buy Impulsively is significant (β = 0.255; p = 0.000), hence H3b is supported. The indirect relationship testing on the relationship between the influence of Scarcity Claims on Impulse Buying Decisions with UTBI as a mediator shows significant results (β = 0.083; p = 0.000). Therefore, H4b is supported. The results of this test confirm the partial mediating role of UTBI on the influence of Scarcity Claims on Impulse Buying Decisions.

Discussion

The results of the research analysis can answer all research questions. First, UTBI play a role in mediating the influence of scarcity and popularity on impulse buying decisions. The role of the UTBI as a mediator is evident in the effect of popularity and scarcity claims on impulse buying decisions. The UTBI is vital to impulse buying decisions (Beatty & Elizabeth Ferrell, Citation1998). The UTBI will arise if there is a strong influence from external stimuli around consumers (Beatty & Elizabeth Ferrell, Citation1998), leading to impulse buying decisions (Iyer et al., Citation2020).

Scarcity seems to create a sense of urgency among buyers that results in increased quantities purchased, shorter searches, and greater satisfaction with the purchased products, therefore accompanying impulse buying (Guo et al., Citation2017). The research resulted the same thing: the urge that arises in consumers results from exposure to scarcity claims. Badgaiyan and Verma (Citation2015) finds nine situational factors that cause the relationship between UTBI and impulse buying. These factors are split into personal and in-store factors, such as sales promotion and store environment (Badgaiyan and Verma, Citation2015). It is believed that the situational factors related to the person and those related to the store will impact the individual’s urge and impulse behavior (Badgaiyan and Verma, Citation2015).

Popularity creates a shopping frenzy (frenzy shopping), which encourages consumer urgency to buy the product immediately (Park et al., Citation2020). In a purchasing context with high consumer involvement, previous purchase number has a negative effect on purchase intention (Kim and Min, Citation2014). However, in the context of purchasing grocery products in this research, the popularity claims in another form, namely: “User Favorite,” can encourage the creation of an urge to buy impulsively, which encourages impulse buying decisions. Consumers tend to buy products that are also bought by many people (Huang and Chen, Citation2006). When consumers believe that sales volume is high, their perceived quality is increasing (Kim and Min, Citation2014).

In the context of the online environment, scarcity messages can maximize impulsive behavior when arousal is stimulated through the provision of scarcity messages (Guo et al., Citation2017). This study also supports previous studies that UTBI are essential mediators of impulse buying behavior (Mohan et al., Citation2013; Saad and Metawie, Citation2015).

The role of popularity and scarcity claims on impulse buying decisions are supported in this research. Popularity and scarcity claims are potential external stimuli to shorten purchase delay periods, and they can encourage consumers to commit to impulse buying (Jeong and Kwon, Citation2012; Coulter and Roggeveen, Citation2012). The role of popularity and scarcity claims on impulse buying decisions in this research is explained through the results of their application in different contexts. In the role of scarcity claims, commodity theory states that product scarcity indicates the high quality of a product. However, in the context of hotel room bookings (an intangible product), Park et al. (Citation2020) stated that scarcity claims do not affect consumer decisions when booking a hotel room. In choosing a hotel room, consumers consider credibility, one of which is marked by the popularity of a hotel (Park et al., Citation2020).

In the context of purchasing a tangible product object in the form of USB flash drives, scarcity claims cannot demonstrate the credibility of a product; consumers also do not feel that their freedom is threatened because of scarcity claims, so they fail to encourage psychological-reactance aspects (Jeong and Kwon, Citation2012). However, in the context of selling grocery products via online media, scarcity claims have an enormous influence on encouraging consumers to decide on impulse buying.

Meanwhile, popularity claims encourage consumers to decide on impulse buying because popularity claims not only cause pleasure and a shopping frenzy (Park et al., Citation2020) but also increase the perceived value and quality of the product (Jeong and Kwon, Citation2012). In the context of purchasing grocery products, perceived value and quality are important things for consumers because grocery products are products that are directly consumed by the body. So, the quality and positive value of grocery products are the primary considerations for consumers when making purchases.

The test results reveal that differences in age can influence impulse buying decisions better than gender, while gender can influence the urge to buy impulsively better than age. People of a younger age are more likely to make impulse buying (Tifferet and Herstein, Citation2012). However, Deloitte’s research (2021) revealed that, during the pandemic, it was the senior generation who decided to buy impulsively because, in those circumstances, the senior generation had more time to study digital technology, including the shopping process through e-commerce, also having better financial ability to decide on a purchase, so that they tend to decide to engage in a higher number of impulse buying. As for gender influence, gender differences influence the emergence of UTBI more than impulse buying decisions. From the individual’s internal aspect (Işler and Atilla, Citation2013) stated that females were more inclined to do instinctive shopping than lazy shopping, which might be attributed to the differences in emotional expression (Fisher and Dubé, Citation2005), while Badgaiyan and Verma’s (Citation2015) research stated that gender differences do not influence the emergence of UTBI; in other words, when exposed to external stimuli, UTBI will arise in both women and men.

Implications for academicians and practitioners

Theoretical implication

From a theoretical point of view, this study fills the gap. It supports previous research such as the arousal (Mehrabian and Russell, Citation1974; Hashmi et al., Citation2020; Guo et al., Citation2017), the commodity (Lynn, Citation1991), the herding behavior theory (Banerjee, Citation1992), the bandwagon effect concept (Leibenstein, Citation1950) and also the strength of social validation mechanism in influencing impulse buying decisions (Cialdini, Citation2007). Arousal theory explained that external stimuli around consumers produce an urge to buy impulsively, which is closer to an impulse buying decision (Liao et al., Citation2016). This research confirmed that external stimulus in the form of persuasion claims influences impulse buying decisions if there is UTBI as a mediator. This study supports the standpoint arousal theory regarding the influence of external stimuli that cause UTBI on the consumer’s state of mind (Cui et al., Citation2022).

The commodity theory reveals that a signal of scarcity will indicate the quality of a product; a product that seems increasingly rare indicates that the product has high quality. However, scarcity claims could not demonstrate product credibility in the moderated involvement product category to encourage purchase intention (Jeong and Kwon, Citation2012). However, in the context of purchasing grocery products, this study shows that scarcity claims tremendously influence impulse buying decisions, although UTBI still has a role as a mediator. So, the perception of credibility arises in consumers because the application of scarcity claims can be different, depending on the product category and the category of consumer involvement in the purchase.

The bandwagon effect concept stated that consumers will tend to do and decide things that are also the decisions of many other individuals (Chen et al., Citation2016), meanwhile herding behavior explained that imitating the behavior of other individuals is a natural human trait, and one’s judgment is often influenced by the opinion of a group (Huang and Chen, Citation2006). Both theoretical mechanisms can be used to base the view that popularity claims are social validation. Popularity claims can be an embodiment of social validation that can encourage consumers to decide to engage in impulse buying (Cialdini, Citation2007; Jeong and Kwon, Citation2012). In the context of purchasing grocery products, social validation from popularity claims can have a more substantial influence on impulse buying decisions if there is UTBI as a mediator. Overall, the results of this research support theoretical mechanisms of the influence of popularity and scarcity claims on impulse buying decisions.

Regarding the influence of age and gender, in the context of purchasing grocery products, age differences can influence impulse buying decisions better than gender, while gender can influence the urge to buy impulsively better than age. Theoretically, these findings support previous research regarding demographic differences in consumer responses, both in the form of UTBI and impulse buying decisions.

Practical implication

The effect of scarcity claims was able to generate the urgency that drives impulse buying decisions. However, this research also revealed that scarcity claims is powerful because even without any urgency, scarcity claims are still able to encourage consumers to make impulse buying decisions. However, applying scarcity claims has different effects when purchasing products with different categories and levels of consumer involvement. So, sellers must first look at the product category and the level of consumer involvement in purchasing the product before applying scarcity claims.

For example, sellers can apply scarcity claims when selling grocery products, but this should not be used in hotel room booking services. Instead, sellers can apply popularity claims to sell room booking services. In booking hotel rooms, consumers rely more on popularity claims because consumers do not consider that limited hotel rooms are something of high value (Teubner and Graul, Citation2020). Consumers pay attention to the credibility of the hotel room they want to book, and popularity claims reflect the credibility aspect more than scarcity claims (Cialdini, Citation2009; Cialdini and Goldstein, Citation2004; He and Oppewal, Citation2018). If the seller wants to create an urge to buy impulsively, which can encourage impulse buying decisions in consumers, then the seller can apply a popularity claims.

In the context of purchasing grocery products, age differences can influence impulse buying decisions better than gender, while gender can influence the urge to buy impulsively better than age. The study results show that UTBI fully mediates the influence of popularity claims on impulse buying decisions, so in practice, to cause UTBI, sellers need to apply popularity claims to genders whose UTBI aspect is more accessible to buy impulsively. So, in encouraging the emergence of UTBI, the application of popularity claims to the correct gender are two things that need to be carefully considered. Meanwhile, UTBI partially mediates the influence of scarcity claims on impulse buying decisions, so in practice, to be able to encourage impulse buying decisions, sellers need to apply scarcity claims to age groups who are more easily encouraged to make impulsive buying decisions. So, in encouraging impulse buying decisions, applying scarcity claims to the right age group are two things that must be carefully considered.

Conclusion and future research

In the context of purchasing grocery products via online media, popularity, and scarcity claims significantly influence the emergence of an urge to buy impulsively, which can encourage impulse buying decisions. This research examines the influence of popularity and scarcity claims on impulse buying decision. However, Knemeyer and Naylor (Citation2011) stated that impulse buying decisions should be researched using experimental research methods. Therefore, further research needs to be carried out using experimental methods. Practically, in the context of purchasing grocery products, sellers can apply scarcity claims, such as: “only available today” and “only 5 of 10 left”, and popularity claims, such as: “user’s favorite!

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ina Melati

Ina Melati is a doctoral candidate in the Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

Bernardinus M. Purwanto

Assoc Prof. Dr. Bernardinus. M. Purwanto (corresponding author) is currently working as a faculty member at Faculty of Economic and Business, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia. He obtained his Ph.D. from the University of The Philipines.

Yessy Caturyani

Yessy Caturyani and Pinkan Olivia Irliane are alumni of Global Business Marketing, BINUS Business School, BINUS University, Jakarta, Indonesia.

Yulia Arisnani Widyaningsih

Yulia Arisnani Widyaningsih is currently working as a faculty member at Faculty of Economic and Business, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia. She obtained her Ph.D. from the University of Queensland, Australia.

References

- Amos, C., Holmes, G. R., & Keneson, W. C. (2014). A meta-analysis of consumer impulse buying. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 21(2), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2013.11.004

- Badgaiyan, A. J., & Verma, A. (2015). Does urge to buy impulsively differ from impulse buying behaviour? Assessing the impact of situational factors. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 22, 145–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2014.10.002

- Balachander, S., & Stock, A. (2005). The making of a “hot product”: A signaling explanation of marketers’ scarcity strategy. Management Science, 51(8), 1181–1192. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1050.0381

- Banerjee, A. V. (1992). A Simple Model of Herd Behavior. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107(3), 797–817. https://doi.org/10.2307/2118364

- Bao, Z., & Yang, J. (2022). Why online consumers have the urge to buy impulsively: roles of serendipity, trust and flow experience. Management Decision, 60(12), 3350–3365. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-07-2021-0900

- Beatty, S. E., & Elizabeth Ferrell, M. (1998). Impulse buying: Modeling its precursors. Journal of Retailing, 74(2), 161–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4359(99)80092-X

- Bellenger, D. N., Robertson, D. H., & Hirschman, E. C. (1978). Impulse Buying Varies by Product. Journal of Advertising Research, 18(6), 15–18.

- Bonabeau, E. (2004). The perils of the imitation age. Harvard Business Review. https://https://hbr.org/2004/06/the-perils-of-the-imitation-age

- Chan, T. K., Cheung, C. M., & Lee, Z. W. (2017). The state of online impulse buying research: A literature analysis. Information & Management, 54(2), 204–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2016.06.001

- Chen, L. D., Lai, X., Wang, N. M., & Huang, W. (2016). Research in Progress: the Snob and bandwagon effects on Consumers’ Purchase Intention under Different Promotion Strategies. In PACIS (p. 118).

- Chung, N., Song, H. G., & Lee, H. (2017). Consumers’ impulsive buying behavior of restaurant products in social commerce. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(2), 709–731. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-10-2015-0608

- Cialdini, R. B., & Goldstein, N. J. (2004). Social influence: conformity and compliance. Annual Review of Psychology, 55(1), 591–621. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142015

- Cialdini, R. B. (2007). Descriptive social norms as underappreciated sources of social control. Psychometrika, 72(2), 263–268. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11336-006-1560-6

- Cialdini, R. B. (2009). Influence: Science and Practice (4th ed.). Pearson.

- Coulter, K. S., & Roggeveen, A. (2012). Deal or no deal? How number of buyers, purchase limit and time-to-expiration impact purchase decisions on group buying websites. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 6(2), 78–95. https://doi.org/10.1108/17505931211265408

- Cui, Y., Zhu, J., & Liu, Y. (2022). Exploring the social and systemic influencing factors of mobile short video applications on the consumer urge to buy impulsively. Journal of Global Information Management, 30(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.4018/JGIM.301201

- Deloitte. (2021). Indonesia consumer insight: Adapting to the new normal in Indonesia. Delloitte. https://www2.deloitte.com/th/en/pages/consumer-business/articles/consumer-insights-id-2021.html

- Dholakia, R. R., Zhao, M., & Dholakia, N. (2005). Multichannel retailing: A case study of early experiences. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 19(2), 63–74. https://doi.org/10.1002/dir.20035

- Dittmar, H., Beattie, J., & Friese, S. (1995). Gender Identity and Material Symbols: Objects and Decisions Considerations in Impulse buying. Journal of Economic Psychology, 16(3), 491–511. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-4870(95)00023-H

- Djafarova, E., & Bowes, T. (2021). ‘Instagram made Me buy it’: Generation Z impulse purchases in fashion industry. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 59, 102345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102345

- Fisher, R. J., & Dubé, L. (2005). Gender differences in responses to emotional advertising: A social desirability perspective. Journal of Consumer Research, 31(4), 850–858. https://doi.org/10.1086/426621

- Foroughi, A., Buang, N. R., Senik, Z. C., et al. (2013). Impulse buying behavior and moderating role of gender among Iranian shoppers. Journal of Basic and Applied Scientific Research, 3(4), 760–769.

- Fuller, C. M., Simmering, M. J., Atinc, G., Atinc, Y., & Babin, B. J. (2016). Common methods variance detection in business research. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), 3192–3198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.12.008

- Gierl, H., Plantsch, M., & Schweidler, J. (2008). Scarcity effects on sales volume in retail. International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 18(1), 45–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593960701778077

- Guo, J., Xin, L., & Wu, Y. (2017). Arousal or Not? The Effects of Scarcity Messages on Online Impulsive Purchase [Paper presentation]. HCI in Business, Government and Organizations. Supporting Business: 4th International Conference, HCIBGO 2017, Held as Part of HCI International 2017, Vancouver, BC, Canada, July 9-14, 2017, Proceedings, Part II 4, 29-40. Springer International Publishing.

- Paul, B., & Gutierrez, B. P. (2004). Determinants of Planned and Impulse Buying: The Case of the Philippines. Asia-Pacific Management Review, 9, 1061–1078.

- Joseph, H. F., Iain, B. R., Barry, B. J., & Rolph, A. E. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective (7th ed.). Pearson Education.

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Hashmi, H. B. A., Shu, C., & Haider, S. W. (2020). Moderating effect of hedonism on store environment-impulse buying nexus. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 48(5), 465–483. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-09-2019-0312

- Hausman, A. (2000). A multi-method investigation of consumer motivations in impulse buying behavior. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 17(5), 403–426. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363760010341045

- He, Y., & Oppewal, H. (2018). See how much we’ve sold already! Effects of displaying sales and stock level information on consumers’ online product choices. Journal of Retailing, 94(1), 45–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2017.10.002

- Hellofs, L. L., & Jacobson, R. (1999). Market share and customers’ perceptions of quality: when can firms grow their way to higher versus lower quality? Journal of Marketing, 63(1), 16–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022242999063001

- Herzallah, D., Muñoz Leiva, F., & Liébana-Cabanillas, F. (2022). To buy or not to buy, that is the question: understanding the determinants of the urge to buy impulsively on Instagram Commerce. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 16(4), 477–493. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIM-05-2021-0145

- Huang, J. H., & Chen, Y. F. (2006). Herding in online product choice. Psychology & Marketing, 23(5), 413–428. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20119

- Huyghe, E., Verstraeten, J., Geuens, M., & Van Kerckhove, A. (2017). Clicks as a healthy alternative to bricks: how online grocery shopping reduces vice purchases. Journal of Marketing Research, 54(1), 61–74. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.14.0490

- Inthuyos, N., Chaiwutikornwanich, A., & Pornphrasertmani, S. (2021). Everyone else does it”: Influence of colleagues’ cheating and psychological mechanisms on individuals’ cheating in an organization. Kasetsart Journal of Social Sciences, 42(4), 770–778.

- Işler, D. B., & Atilla, G. (2013). Gender differences in impulse buying. International Journal of Business and Management Studies, 2(1), 176–182. https://doi.org/10.1108/13612020310484834

- Iyer, G. R., Blut, M., Xiao, S. H., & Grewal, D. (2020). Impulse buying: A meta-analytic review. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 48(3), 384–404. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-019-00670-w

- Jeong, H. J., & Kwon, K. N. (2012). The Effectiveness of Two Online Persuasion Claims: Limited Product Availability and Product Popularity. Journal of Promotion Management, 18(1), 83–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/10496491.2012.646221

- Kim, J. H., & Min, D. (2014). The effects of brand popularity as an advertising cue on perceived quality in the context of internet shopping. Japanese Psychological Research, 56(4), 309–319. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpr.12055

- Knemeyer, A. M., & Naylor, R. W. (2011). Using behavioral experiments to expand our horizons and deepen our understanding of logistics and supply chain decision making. Journal of Business Logistics, 32(4), 296–302. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0000-0000.2011.01025.x

- Ku, G., Malhotra, D., & Murnighan, J. K. (2005). Towards a competitive arousal model of decision-making: A study of auction fever in live and internet auctions. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 96(2), 89–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2004.10.001

- Lamis, S. F., Handayani, P. W., & Fitriani, W. R. (2022). Impulse buying during flash sales in the online marketplace. Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 2068402. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2068402

- Lee, S. M., Ryu, G., & Chun, S. (2018). Perceived control and scarcity appeals. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 46(3), 361–374. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2068402

- Lee, M., Kim, Y., & Fairhurst, A. (2009). Shopping value in online auctions: their antecedents and outcomes. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 16(1), 75–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2008.11.003

- Leibenstein, H. (1950). Bandwagon, Snob and Veblen Effects in the Theory of Consumers’ Demand. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 64Issue(2), 183. https://doi.org/10.2307/1882692

- Leong, L. Y., Jaafar, N. I., & Ainin, S. (2018). The effects of Facebook browsing and usage intensity on impulse purchase in f-commerce. Computers in Human Behavior, 78, 160–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.09.033

- Liao, C., To, P.-L., Wong, Y. C., Palvia, P. C., & Kakhki, M. D. (2016). The Impact of Presentation Mode and Product Type on Online Impulse Buying Decisions. Journal of Electronic Commerce Research, 17, 153.

- Liu, Y., Li, H., & Hu, F. (2013). Website attributes in urging online impulse purchase: An empirical investigation on consumer perceptions. Decision Support Systems, 55(3), 829–837. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2013.04.001

- Lynn, M. (1991). Scarcity effects on value: A quantitative review of the commodity theory literature. Psychology & Marketing, 8(1), 43–57. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.4220080105

- Malhotra, N., & Birks, D. F. (2007). An applied approach. Marketing Research. Prentice Hall.

- Mattila, A. S., & Wirtz, J. (2008). The role of store environmental stimulation and social factors on impulse purchasing. Journal of Services Marketing, 22(7), 562–567. https://doi.org/10.1108/08876040810909686

- Mehrabian, A., & Russell, J. A. (1974). An Approach to Environmental Psychology. The MIT Press.

- Mohan, G., Sivakumaran, B., & Sharma, P. (2013). Impact of store environment on impulse buying behavior. European Journal of Marketing, 47(10), 1711–1732. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-03-2011-0110

- Nelson, P. (1974). Advertising as Information. Journal of Political Economy, 82(4), 729–754. https://doi.org/10.1086/260231

- Park, S., Rabinovich, E., Tang, C. S., Yin, R., & Yu, J. J. (2020). Should an online seller post inventory scarcity messages? Decision Sciences, 51(5), 1288–1308. https://doi.org/10.1111/deci.12402

- Paul, J., Kaur, D. J., Arora, D. S., & Singh, M. S. V. (2022). Deciphering ‘Urge to Buy’: A Meta-Analysis of Antecedents. International Journal of Market Research, 64(6), 773–798. https://doi.org/10.1177/14707853221106317

- Piron, F. (1991). Defining impulse purchasing. Advances in Consumer Research. http://acrwebsite.org/volumes/7206/volumes/v18/NA-18%0AAdvances

- Rook, D. W., & Hoch, S. J. (1985). Consuming Impulses. Advances in Consumer Research. https://www.acrwebsite.org/volumes/6351/volumes/v12/NA-12/full

- Rook, D. W. (1987). The buying impulse. Journal of Consumer Research, 14(2), 189. https://doi.org/10.1086/209105

- Saad, M., & Metawie, M. (2015). Store environment, personality factors and impulse buying behavior in Egypt: The mediating roles of shop enjoyment and impulse buying tendencies. Journal of Business and Management Sciences, 3(2), 69–77. https://doi.org/10.12691/jbms-3-2-3

- Setyani, V., Zhu, Y. Q., Hidayanto, A. N., Sandhyaduhita, P. I., & Hsiao, B. (2019). Exploring the psychological mechanisms from personalized advertisements to UTBI on social media. International Journal of Information Management, 48(4), 96–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.01.007

- Shamim, K., Azam, M., & Islam, T. (2024). How do social media influencers induce the urge to buy impulsively? Social commerce context. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 77, 103621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2023.103621

- Singh, R. (2019). Why do online grocery shoppers switch or stay? An exploratory analysis of consumers’ response to online grocery shopping experience. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 47(12), 1300–1317. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-10-2018-0224

- Sundar, S. S., Oeldorf-Hirsch, A., & Xu, Q. (2008). The bandwagon effect of collaborative filtering technology [Paper presentation]. CHI’08 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 3453–3458). https://doi.org/10.1145/1358628.1358873

- Teubner, T., & Graul, A. (2020). Only one room left! How scarcity cues affect booking intentions on hospitality platforms. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 39, 100910. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap.2019.100910

- Tifferet, S., & Herstein, R. (2012). Gender differences in brand commitment, impulse buying, and hedonic consumption. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 21(3), 176–182. https://doi.org/10.1108/10610421211228793

- Utama, A., Sawitri, H. S. R., Haryanto, B., & Wahyudi, L. (2021). Impulse Buying: The Influence of Impulse Buying Tendency, Urge to Buy and Gender on Impulse Buying of the Retail Customers. Journal of Distribution Science, 19-7, 101–111.

- Wells, J. D., Parboteeah, V., & Valacich, J. S, University of Massachusetts Amherst. (2011). Online impulse buying: understanding the interplay between consumer impulsiveness and website quality. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 12(1), 32–56. https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00254

- Wu, C. S., Cheng, F. F., & Yen, D. C. (2008). The atmospheric factors of online storefront environment design: An empirical experiment in Taiwan. Information & Management, 45(7), 493–498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2008.07.004

- Wu, Y., Xin, L., Li, D., Yu, J., & Guo, J. (2021). How does scarcity promotion lead to impulse purchase in the online market? A field experiments. Information & Management, 58(1), 103283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2020.103283

- Xu, W., Jin, X., & Fu, R. (2021). The influence of scarcity and popularity appeals on sustainable products. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 27, 1340–1348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2021.03.014

- Yue, X., Abdullah, N. H., Ali, M. H., & Yusof, R. N. R. (2023). The impact of celebrity endorsement on followers’ impulse purchasing. Journal of Promotion Management, 29(3), 338–358. https://doi.org/10.1080/10496491.2022.2143994

- Zafar, A. U., Shahzad, M., Ashfaq, M., & Shahzad, K. (2023). Forecasting impulsive consumers driven by macro-influencers posts: Intervention of followers’ flow state and perceived informativeness. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 190, 122408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2023.122408

- Zafar, A. U., Qiu, J., Shahzad, M., Shen, J., Bhutto, T. A., & Irfan, M. (2021). Impulse buying in social commerce: bundle offer, top reviews, and emotional intelligence. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 33(4), 945–973. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-08-2019-0495

- Zhang, X., Prybutok, V. R., & Koh, C. E. (2006). The role of impulsiveness in a TAM based online purchasing behaviour model. Information Resources Management Journal, 19(2), 54–68. https://doi.org/10.4018/irmj.2006040104

- Zhang, K. Z., Xu, H., Zhao, S., & Yu, Y. (2018). Online reviews and impulse buying behavior: the role of browsing and impulsiveness. Internet Research, 28(3), 522–543. https://doi.org/10.1108/IntR-12-2016-0377

- Zheng, X., Men, J., Yang, F., & Gong, X. (2019). Understanding impulse buying in mobile commerce: An investigation into hedonic and utilitarian browsing. International Journal of Information Management, 48, 151–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.02.010