Abstract

This research article examines the implementation of service-dominant logic in technology-based business incubators, specifically focusing on Bandung Techno Park in Indonesia. The research examines the connection between service providers and clients, the function of technology-based business incubators in assisting enterprises, and the consequences of transitioning from a focus on products to a focus on services. This study offers an extensive literature analysis on technology-based business incubators, goods-dominant logic, and service-dominant logic. Additionally, it analyzes the business process structure and services provided by Bandung Techno Park. The study highlights the significance of comprehending service-dominant logic principles while evaluating and improving services in technology-based business incubators. Furthermore, it emphasizes the importance of collaborations between universities and industries, the transition to more participatory innovation models, and the involvement of service-dominant logic in generating value. The article recommends doing further research in this field, namely with larger sample sizes and longitudinal investigations.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

Introduction

Goods-Dominant Logic (G-D Logic) converts value propositions into interchangeable units like work time, service duration, rental terms, training quantities, development costs, information source capacity, and more (Gannage Jr., 2014). Actors recognize that services are more than simply units of trade value (Adner & Kapoor, Citation2010), but the services they provide, which typically include physical objects and integrated human activities, lack visibility. Extension may be described, but it has a lot to do with the customer as a static object and the service in return for an offer, like a product.

This research develops a service-dominant logic (S-D Logics) service orientation for a technology-based business incubator. This approach investigates several service orientation principles in the context of value generation through an incubator’s service-dominant logic lens. It is expected to help Indonesian technology-based companies shift from G-D logic to S-D logic. The aim of this study is to investigate service-dominant logic in technology-based business incubators, mainly focusing on Bandung Techno Park in Indonesia. The research seeks to comprehend the correlation between service providers and clients, the function of technology-based company incubators in assisting enterprises, and the consequences of transitioning from goods-dominant reasoning to service-dominant logic. In addition, the study aims to highlight the significance of collaborations between universities and industries, interactive models of innovation, and the role of service-dominant logic in value creation.

Industry conditions suggest a methodical strategy for startup and MSMEs development. The Indonesian government created the Business Incubator to help businesses thrive (Presidential Decree No. 27 of 2013). According to Bank Indonesia, Indonesia has fewer business incubators than the European Union (1100), Canada (1000), and China (1000). (450). (2016). Indonesia has 150 AIBI-member business incubators (2020). Indonesia has few ICT business incubators that can foster high-quality technology firms ().

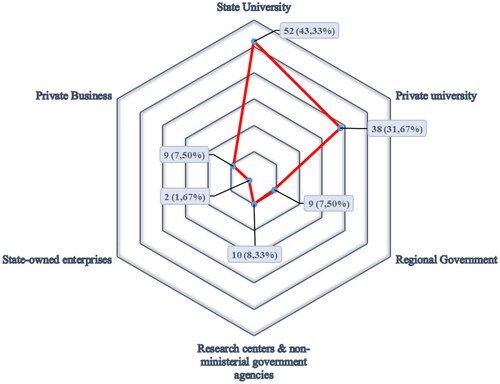

Figure 1. Distribution of Technology-based Business Incubator (TB-BI) based on ownership in Indonesia, Source: Indonesian Business Incubator Association (2021).

The National Forum for the Indonesian Business Incubator Association expects 120 technology-based business incubators by mid-2022. 1. Universities own 75% (90) of technology-based business incubators. Public universities account for 43.3% (52 institutions) and private universities for 35%. (38 institutional units). The regional government contributed 7.5% (9 institutional units), central and non-ministerial government institutions (LPNK) contributed 8% (10 institutional units), private incubators contributed 7.5%, and state-owned firms contributed the least, 1%. (2). Indonesia has 58% state-run technology-based business incubators and 42% private universities. Universities—public and private—dominate technology-based business incubator development, as seen above. Many Indonesian firms started at universities (Dikti, Citation2017). This study should focus on an Indonesian institution with a technology-based business incubator. Graduated incubators with programs. This study examines Bandung Techno Park. In 2010, the Indonesian Ministry of Industry, the Ministry of Research and Technology, the Ministry of Education and Culture, Industry, and the Regional Government founded a technology-based company incubator. Telkom Institute of Technology (now Telkom University). BTP incubation involves three stages: pre-incubation, incubation, and post-incubation. Startups graduate from these three phases into autonomous businesses in a year. Strat-ups were encouraged to accomplish incubation achievements to obtain intellectual property and property rights for their inventions and market-valid technology-based goods. However, all BTP business incubation situations that chase timetables and focus on outcomes are transactional. Special research is needed to improve service. shows the Bandung Techno Park business interaction process.

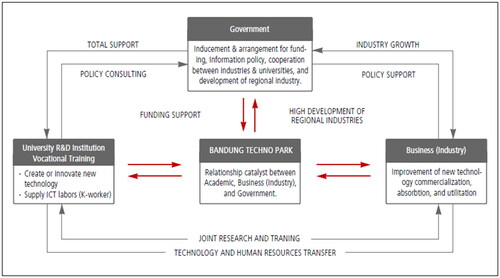

Figure 2. Bandung Techno Park Quadruple Helix Model (Source: Bandung Techno Park Presentation, Unesco-WTA Training Workshop).

illustrates the multi-way relationship between Bandung Techno Park (BTP), a platform for incubation organizers and coaches, and academics, business sector/industry, government, and society in a quadruple helix, known as ABGC. BTP’s business incubation services help entrepreneurs and renters grow: Mediation. (2) Production Support. (3) Innovation Center. BTP provides multiple facilities for the ICT community to develop and innovate; and (4) training and consultation. BTP offers ICT-specific training and consultancy. This service is public. BTP, Central and Regional Government (limited to the Ministry of Industry, Ministry of Research and Technology, and Ministry of Education), Industry (Telecommunication, Medical Technology Manufacturing, and Defense), Telkom University under the supervision of the Telkom Education Foundation, and partner universities were the main parties involved in BTP activities until this observation. BTP acts as an intermediary to foster ICT-based industry synergy in Indonesia.

Service science provides a fresh viewpoint on Bandung Techno Park’s incubation program’s business process structure in this research. Business management uses the dominant logic of goods (G-D logics) (Vargo & Lusch, Citation2004a, Citationb; Vargo & Lusch, Citation2008). Throughout the industrial era, when economic development depended on an institution’s ability to produce surplus goods and export them for a profit, it became a common corporate philosophy (Vargo & Lusch, 2008). The fundamental philosophy explains the prevailing value viewpoint as transaction, trade, and interest in growing that value for company transformation, survival, and competitive advantage (Lusch et al., Citation2007). Thinking in service is a two-way connection that adds value, according to numerous service papers (Vargo, Citation2009). This partnership has selling value as a track record of building a company environment that builds on each other (Akaka & Vargo, Citation2014).

Various institutions in Indonesia often utilize BTP as a reference for all of the pictures and qualities that it has as a technology-based business incubator. Is the service model used by BTP a good concept? How can the standpoint of service-dominant logic describe the idea of technology-based business incubation services? How many critical elements, such as service competencies, must technology-based incubators alter at universities in order to develop a good system throughout the incubation period? The three issues that will be explored using the SD-L viewpoint will be essential to this research.

This research article examines the implementation of service-dominant logic in technology-based business incubators, explicitly focusing on Bandung Techno Park in Indonesia. The text examines the correlation between service providers and clients, the function of incubators in assisting startups, and the transition from a focus on products to services. The study highlights the significance of comprehending service-dominant logic principles while evaluating and improving services in technology-based business incubators.

The study suggests that using service-dominant logic in technology-based business incubators, especially at Bandung Techno Park in Indonesia, will cause a shift from goods-dominant logic to service-dominant logic. This will lead to better support for startups, better performance management for technology-based incubators, and the formation of long-lasting innovation networks. This shift is expected to emphasize the importance of university-industry partnerships, interactive innovation models, and the role of service-dominant logic in creating value. The study also suggests that focusing on education and human resources support, along with ongoing evaluation, will be important for putting service-dominant logic into action in technology-based business incubators.

In order to further enrich the viewpoint of service-dominant logic in this study, it would be beneficial to formulate many research questions: How does the shift from goods-dominant logic to service-dominant logic impact technology-based business incubators? What are the essential services provided by technology-based business incubators for the success of startups? How can understanding service-dominant logic principles help assess and improve services in technology-based business incubators?

The Bandung Techno Park chief account officer was interviewed in-depth for a qualitative study. This study collected data through a qualitative dual-case study. This research included business incubator managers from Bandung Techno Park, including the Head of Innovation and Business Incubator, the Head of Business Incubation and Entrepreneurship, the Head of Innovation Affairs, and a representative of the Indonesian Business Incubator Association. Indonesian Business Incubator Association Program Development Division head. As well as seven Bandung Techno Park tenants who have experience and are field-oriented learners learning to build their firms through the incubation program owned by the seven startups. Secondary data collected the rest. The study team’s independent evaluation of all data (that is, the authors of this article). Informants (resource persons and focus group participants) include firm executives (seniors), managers, researchers, and university employees who construct, manage, and use ecosystems. Service science is used to assess criteria, stages, learning, facilities, graduation, and post-graduate programs. Service observations mapping by service orientation revealed Goods-Dominant Logic and Service-Dominant Logic.

Literature review

Technology-based business incubator

Technology-based business incubators are organizations or firms that may originate from numerous industries with the goal of providing a program for novice entrepreneurs and are particularly geared to provide services in terms of coaching startups and speeding company growth in the short term (Mian, Citation2014). Technology-based business incubators provide services that help firms grow quickly via a program that is backed by partnerships and other business aspects (Smilor, Citation1987a, Citation1987b). Some of the most significant parts of guidance and services include capital, work facilities, training, and advice (Lee & Osteryoung, Citation2004). These many elements and help are carried out in order to encourage small-scale startups, also known as tenants, to have a more focused, structured, and quantified financial organization and administration in order to generate a profit more quickly and stand in a sustainable manner (Etzkowitz, & Zhou, Citation2017). In the previous five years, Indonesia has supported the establishment of business incubators in all universities via the Ministry of Research and Technology. The government-backed "Welcoming Indonesia 4.0" initiative has served as a springboard for the development of technology-based business incubators in different institutions. However, the service standards given by each institution on the business incubation platform are not consistent (Somsuk & Laosirihongthong, Citation2014). Both in the form of financial aid services (Phillips, (Citation2002), recruiting methods (Schwartz & Hornych, Citation2008), educational programs that are part of the service (Lee & Osteryoung, Citation2004), and inadequate physical facilities (Bruneel et al., Citation2012; Lee & Osteryoung, Citation2004). Physical amenities can be built adequately in large towns, but not in rural areas of Indonesia.

Service science

Diversified services without quality standards require research. University-educated technology business incubator administrators need service science. Why? Indonesian academics and the public are unfamiliar with service science. IBM researcher Jim Spohrer and UC Barkeley Professor of Innovation Studies Henry Chesbrough invented this notion in 2002 (Chesbrough & Spohrer, Citation2006). Transdisciplinary science in business practice, especially between technology and social science, was explored. Fujitsu asserted that service science originated due to the service sector’s considerable emphasis on innovation.

According to Maglio and Spohrer (2008) (Vargo et al., 2008), service science is the study of service systems, which are made up of people, technology, organizations, and shared information that work together to create dynamic values that help systems deal with difficult problems. Both papers agree that service science’s combination of organizational and humanist thinking with business and technology greatly increases our knowledge of how varied players in a system create value and benefits. Despite Spohrer’s emphasis on the service economy, little research has been done. Research and commercial perspectives on service have changed. Service-oriented academic programs and a shift from production to service (such as: computer science, technology, operations management, and marketing). Finally, service science is the scientific study of service problems and service system interactions (Maglio et al., Citation2019). In conclusion, service science is the application of scientific approaches to the study of service problems and the research of the interactions between components of service systems.

Goods-dominant logic (GD-L)

Goods-Dominant Logic (G-D LOGICS) fundamentally differentiates producers and consumers (Lusch & Vargo, Citation2006). This optimizes production, efficiency, and marketing profit. Michel et al. (Citation2008) called goods-dominant logic manufacturing logic and praised Richard Normann (Citation2001), who viewed products as frozen past actions. Products focusing on the manufacturing-based economic exchange paradigm built during the Industrial Revolution are still in use, but the inflexible and transactional connection between producer and consumer has become obsolete. This is because service marketing will be the dominant marketing strategy in the future, with physical goods becoming part of a complete service offering (Grönroos Citation2008). This suggests that service-oriented thinking will dominate, even if physical and service marketing converge. The dominating goods paradigm is used to make economics a science, among other reasons.

Technology-based business incubators require clients to follow a defined incubation program. As a transactional partnership, their reciprocal relationship no longer suffices. Service quality has changed. A service model that serves both parties must include their fresh perspectives. A completely technology-based company incubator will focus on exchange and transactional center activities rather than only manufacturing items to promote value creation, production, innovation, growing markets, and analyzing customers.

Product standardization and market-oriented focus achieve this. Producers and consumers only deal. The engagement of internal and external parties in third parties’ corridors is limited to producers and consumers. They exchange physical results and distinct transactions.

Service-dominant logic (SD-L)

According to the expanding academic literature, which also emphasizes business science and service science, the firm’s direction is shifting from goods to services (Ng & Vargo, Citation2018). The dynamic of established and rising nations shifting to manufacturing is shifting toward services. Vargo and Lusch (Citation2004a, Citationb) consider a service-dominant trade logic is more integrative than a goods-dominant logic (Karpen et al., Citation2012; Vargo & Lusch, Citation2016).

This follows the industrial revolution’s transition from products to services. Institutions speed up by offering many service formulations to technology-based business incubators. Starting with basic tenant readiness and advancing to complete preparedness as a consequence of the learning phase in the incubation process may be a gauge of business incubator performance in serving start-ups. Vargo and Lusch (Citation2004a, Citationb) define services as intangible, immeasurable, diverse, and perishable. Even the idea relies on solving an economic problem.

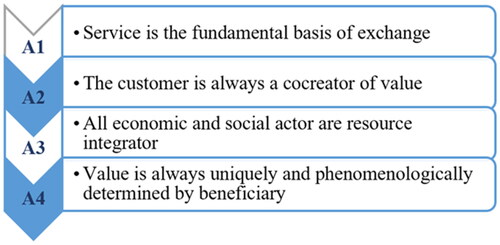

Early marketing theory focused on product delivery and exchange. However, the transformation process requires many hard and rigorous tasks, including the progressive movement from startups from invention to innovation and product development, building prototypes, market validation, gauging market interest, production, and manufacturing capacity. For this reason, switching from goods-dominant logic (G-D logics) to service-dominant logic (S-D logics) may have scientific and practical benefits. In its development, S-D Logics focuses on the historical disclosure of the basic development of economics, which is still formed on the basis of G-D Logics. The development of his theory of S-D logic is described in four stages of axioma, as shown in .

Ten basic rules of service-dominant logic (Vargo & Lusch, 2004a, b) must be understood in order to evaluate the services in tech-based business incubators (). In addition, to guarantee that the type of service will be chosen for future service enhancement,. The primary premises are:

Table 1. Service-dominant logic premises.

Goods-dominant logic vs. service-dominant logic

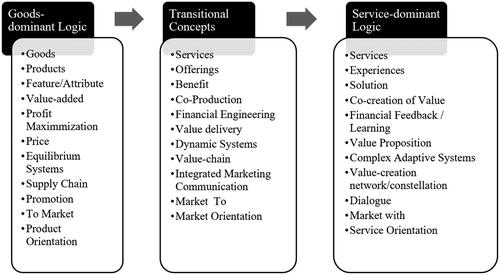

Many scientific studies have looked at "dominant logic," such as "as an information classifier that determines what managers and researchers" should focus on in strategic contexts (Prahalad & Bettis, 1986; Prahalad & Ramaswamy, 2004); service-dominant logic in Vargo and Lusch’s (2004) work; and networks (Ford & Håkansson, 2013). Redefining services as "the application of specialized competences (knowledge and skills) through practices, processes, and performances for the profit of another entity or the entity itself" (Vargo & Lusch, Citation2004a, Citationb) gives marketing a new perspective. "Service-dominant logic (S-D Logics)" research, consolidation, and characterization continued. "Service-dominant logic: replies, reflections, and refinements" (Lusch & Vargo, Citation2006) shows S-D logic conceptual transitions ().

illustrates that each institution undergoes a variable-length method to translate GD-L to SD-L. This survey also shows how many technology-based business incubators from different countries use the GD-L strategy to serve tenants or startups during the incubation period. The US has the most business incubators. The US government supports incubators through economic development and job creation laws (Ogutu & Kihonge, Citation2016). They sponsored local and state aid (Chandra & Fealey, Citation2009). Business incubators in the US are privately owned and funded by government grants, university/company financing, renting, and consulting. State financing, economic development agencies, capital ventures from state legislative appropriations, and state competitive grants and equivalents provide transactional and time-bound aid to US incubators. Thus, the American company incubator service system still features a product-dominating logic scheme that directs startup production using transactional schemes and has a short lifetime.

The Chinese government employs business incubators to create markets and promote startups due to institutional barriers to startup growth and the necessity to move to a market system. Business incubators are government-run infrastructure. The Torch Program is famous. The Chinese government established the Ministry of Science and Technology (MoST) in the 1990s to aid incubator growth, and it has made significant investments in incubators through the "building fund" channel. This building line provides various amenities for technology-based business incubators (Lalkaka, Citation2000, Citation2001). The government has "construction" funds for incubators, "seed capital" funds for startups, and "innovation" funds for small and medium-sized enterprises in development. The Ministry of Science and Technology provides an innovation grant for product development and innovation. The Chinese government funded technology-based business incubator operational construction facilities with 50 million Yuan (US$6 million) every year during the 10th Five-Year Plan (2001–2005). Thus, Chinese incubators have more room and capacity (Scaramuzzi, Citation2002). China’s shift to a high-tech, market-based economy relies on business incubators, which the government is willing to spend heavily on (Citation2002). This trend shows China’s transactional approach to technology-based business incubators. A lot of capital should boost output and market potential over time. GD-L says this focuses on items, products, characteristics, value-added, profit maximization, market pricing, and equilibrium systems that affect national economic growth.

In Brazil, incubators are frequently associated with universities and funded by a variety of public and private organizations, but the collaborative relationship between universities and industry improves corporate stakeholder engagement. The National Incubation Support Program (PNI) funds incubators. This initiative builds incubator workplaces to help start new incubators and expand existing ones. The Brazilian Ministry of Science and Technology, CNPq, FINEP, SEBRAE, and ANPROTEC sponsor the PNI initiative (Scaramuzzi, Citation2002). The degree of corporate and government support for incubation in Brazil is crucial. For instance, FIESP runs 12 incubators. Industrial participation oversees business incubators. Industry controls mass-produced goods’ supply chain. To create new items, incubation is stressed. The government-sanctioned federation coordinates with many entities. In this scenario, Brazil’s technology-based business incubator lacks the freedom to create services and establish internal and external networks that fulfill ANPROTEC’s operational criteria.

In Indonesia, schools must create a technology business incubator, or IBT, which is very effective in launching technology-based firms. In line with Presidential Regulation Number 27 of 2013 on Entrepreneurial Incubators and Ministerial Regulation Number 24 of 2015 on Norms, Standards, Procedures, and Criteria (NSPC) for Entrepreneurial Incubators, the IBT provides mentorship and services.

Entrepreneurs from academia, industry, and government are created through the incubator. Universities with technology-based business incubators can sell inventions directly to the market with A or B accreditation from the government. Considering the business incubator’s physical facilities, programs, management, and organization,. Indonesia’s Ministry of Research, Technology, and Higher Education has built over 50 IBTs to fortify institutions. Data was collected from numerous technology-based business incubators financed by the government, institutions, and industry that create Indonesia’s top startups, including Bandung Techno Park, Incubie Bogor Agricultural University (IPB), the University of Indonesia’s Directorate of Business Innovation and Incubation (DIIB UI), Yogyakarta State University’s Institute for Research and Community Service (LPPM UNY), and Skystar Venture Multimedia Nusantara University (U). Since 2016, the Ministry of Research, Technology, and Higher Education’s "CPPBT" initiative has promoted campus startups. The Ministry of Research, Technology, and Higher Education has supported 558 PPBT applicants from all around Indonesia in recent years, 558 CPPBT applicants were only able to progress to PPBT with a 10.57% rate. PPBT conversion is poor due to CPPBT. CPPBT events will be held this year with 132 participants from 70 universities from Sabang to Merauke. The program’s enrollment has dropped due to government legislative revisions. The program purpose has changed, terms and conditions must be amended, and regulations and processes must be harmonized, making administration tough. Even if the situation has improved, the current physical infrastructure will not be enough to provide the service businesspeople need.

Research methodology and data collection

The research approach used in this study consisted of a qualitative dual case study, including in-depth interviews with experts and focus group observations carried out at Bandung Techno Park and with startups. The data for the research was gathered by conducting interviews with business incubator managers, members of the Indonesian Business Incubator Association, and seven tenants of Bandung Techno Park. The use of multiple data sources, such as documents or reports, enhances the validity and reliability of the findings through data triangulation. In addition, the research team acquired secondary data and assessed it independently. The study applied service science to evaluate criteria, stages, learning, facilities, graduation, and post-graduate programs. It also utilized service observation mapping to differentiate between goods-dominant and service-dominant logic.

The project also included a feasibility study using prior studies conducted by Campbell (Citation1989), Allen and Weinberg (Citation1988), and Smilor and Gill (Citation1986). Moreover, the study underlined the need for ongoing assessment and advocated further investigation to comprehend the service-dominant logic in technology-based business incubators. It underscored the significance of quantitative analysis using larger sample sizes and longitudinal research methods.

Additionally, using earlier studies by Mian et al. (Citation2016), Falkäng and Alberti (Citation2000), and Fayolle et al. (Citation2006) as references, the study looked at the significance of training and support for human resources in technology-based incubators. The study also examined the transition in service characteristics from transactional to value-in-use and the function of technology-based company incubators in establishing marketing networks.

The appropriateness of the data collection methods for this study, such as in-depth interviews, focus group observations, and secondary data collection, was assessed to ensure the necessary insights and perspectives from the participants. An in-depth interview was conducted with the chief account officer of Bandung Techno Park for qualitative research. This research gathered data using a qualitative dual-case study methodology. This research gathered data through interviews and focus group observations of business processes at Bandung Techno Park and many other startups. The sampling strategy was reviewed to ensure it is representative of the population under study, considering the size and diversity of the sample and any potential biases in the selection process. This study included business incubator managers from Bandung Techno Park, namely the Head of Innovation and Business Incubator, the Head of Business Incubation and Entrepreneurship, the Head of Innovation Affairs, and an Indonesian Business Incubator Association representative. The seven tenants of Bandung Techno Park, who are knowledgeable and committed to practical learning, are also growing their businesses thanks to the incubation program the seven startups offer. The remaining data was acquired as secondary data. This study conducted an independent examination of all the data in the research. The informants include top corporate executives, managers, researchers, and university personnel involved in the construction, management, and use of ecosystems. They are sources that are sampled as a benchmark, allowing for a comprehensive understanding of the impact of service-dominant logic on technology-based business incubators by including a diverse range of perspectives from various stakeholders involved in the incubation process. Service science evaluates the criteria, stages, educational opportunities, graduation, and post-graduate programs. Service observations were mapped based on service orientation. Goods-Dominant Logic and Service-Dominant Logic are two contrasting approaches. displays the data: Mapping the service orientation of technology-based business incubators. In this study, the mapping of service orientation was conducted by utilizing service science to assess criteria, stages, learning, facilities, graduation, and post-graduate programs. The study identified seven service orientation assertions to map the service orientation, which included efforts to manage the development center’s initial development stage of operating costs, improve the development of startups, and provide quality-of-service assistance. The study also looked at service orientation through lenses like technology-based business incubators, science parks, innovation centers, and accelerators to learn more about the different types of service provision and how service-dominant logic can be used in technology-based business incubators.

Table 2. Service orientation mapping of technology based business incubator.

Furthermore, the study distinguished between goods-dominant logic (GD-L) and service-dominant Logic (SD-L) to map the service orientation. It highlighted the shift from goods-dominant logic to service-dominant logic and its implications for technology-based business incubators, emphasizing the importance of university-industry partnerships, interactive innovation models, and the role of service-dominant logic in creating value. This careful method for gathering, analyzing, and mapping data helped the study learn important things about the change from goods-dominant logic to service-dominant logic in technology-based business incubators. This made the study’s results more solid and in-depth. The study looked at how service orientation was mapped in this way to see how service-dominant logic could be used and what that meant for technology-based business incubators. It gave useful information about the change from goods-dominant logic to service-dominant logic in this situation. The technique used a holistic approach, including qualitative data collection, feasibility studies, and a strong emphasis on education and human resources assistance ().

Table 3. Type of service orientation in Bandung Techno Park as a technology-based business incubator role.

Furthermore, the study distinguished between Goods-Dominant Logic (GD-L) and Service-Dominant Logic (SD-L) to map the service orientation. It highlighted the shift from goods-dominant logic to service-dominant logic and its implications for technology-based business incubators, emphasizing the importance of university-industry partnerships, interactive innovation models, and the role of service-dominant logic in creating value.

Data analysis

This research successfully enhanced the credibility and comprehensiveness of analyzing the service-dominant logic perspective in technology-based business incubators by identifying numerous examples and case studies, addressing challenges, proposing strategies, exploring cross-industry collaboration, and providing methodological details.

Successful incubator campaign identification

BTP effectively executed a pre-incubation campaign that engaged university faculties and labs to recruit incubation tenants. This aligns with the endeavors of technology-focused business incubators, which serve as co-creators of value and play a significant role in service science by facilitating the collaborative and interactive co-creation of value between service providers and customers.

Distinctive characteristics

Startups that become tenants are offered a one-of-a-kind and exceptional service package. Not only do they undergo a learning process, but they also get guidance from mentors and coaches who are adaptable to meet their requirements. Interactive modes of communication serve as a means for aspiring entrepreneurs to foster innovation. Before graduating from the incubation program, participants are guided on securing patents and copyrights for their discoveries. They also get support in building their professional network with industry professionals, investors, and government representatives.

Failure or struggle analysis

Many new tenants are admitted to the business incubator each year. However, according to statistics, only 10–15% effectively finish the program and graduate. This challenge often arises when entrepreneurs need to establish a clear and comprehensive business model, which is crucial for persuading potential investors. An in-depth investigation is required to assess the potential for innovation driven by technology and market forces. The main issue experienced at Bandung Techno Park is the higher probability of failure than success.

Result discussion

This research indicates that there is no standard measure of the efficacy of a technology-based business incubator when seen via the service-dominant logic lens, a managerial challenge for business incubators. Success is survival and company growth (Rothaermel & Thursby, Citation2005). Joining a business incubator firm is for the academic potential to create a collaborative business environment. We found almost no post-incubation performance studies. The brief pre-incubation, incubation, and post-incubation phases are only an analogy for the ease of "graduating" to become a tenant and have nothing to do with post-incubation survival. In this research, success is measured by thorough identification of industry requirements, periodic assessment of tenant/startup satisfaction with incubator services provided by physical facilities, and incubation programs (G-D Logics and S-D Logics). The two will improve performance management for tech incubators (Almoli, Citation2018).

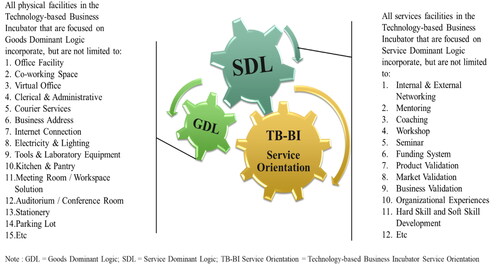

shows how we separate service orientation from G-D Logics by concentrating on the physical facilities offered throughout the incubation term agreed upon by the company as a tenant with the management of a technology-based business incubator. This appears to be a significant service presented to potential tenants, rather than incubation programs that showcase businesses’ short- and long-term success through measurable and scheduled activities. S-D Logics are said to affect technology-based business incubators more. Startups require mentoring programs, stakeholder meetings, help creating networks, business contests to attract investors, workshops, training, coaching, and seminars. Technology-based business incubators may achieve short-term and long-term success by helping enterprises grow. A technology-based business incubator’s pre-, in-, and post-incubation operations work better when coupled to service-dominant reasoning. Service-Dominant Logic’s ten fundamentals, transportation, renewable energy, medical, and ICT services can also use the application.

Service-dominant Logic allows us to study additional technology-based business incubators based on our insights. Thus, technology-based business incubators use at least seven Service Orientations (SOs) as service orientation lenses. shows two viewpoints of this orientation service.

SO-1: Tech Business Incubators Science parks, innovation centers, and accelerators are technology-based business incubators. Technology and entrepreneurship are boosted by policy tools (Mian et al., Citation2016). Technology-based business incubators are generally formed through public-private collaborations involving universities, industries, and corporations, including all levels of government (Etzkowitz, Citation2002). To encourage creative local firms, knowledge transfer and product distribution are promoted. It’s not enough to grasp industry needs (Lalkaka, Citation2000).

SO-2: Technology-based business incubator must have a periodic assessment program on startup satisfaction as a tenant for service incubators (Hackett & Dilts, Citation2004). If necessary, an assessment is also carried out to get feedback from all stakeholders of the technology-based business incubator. The assessment indicator may use the G-D Logics and S-D Logics element.

SO-3: Efforts to manage the development center’s initial development stage of operating costs by providing vital tools and infrastructure may become critical. However, it is much more significant to establish a broader and more structured short-term and long-term plan for each tenant participating in the incubation period program (Campbell, Citation1989)

SO-4: Improving the development of startup can be done by optimizing the management of collaboration among facility providers, program implementers, mentors, and internal and external agents as facilitators to apply service dominant logics with their respective competencies (Polat, Citation2021)

SO-5: If previously stated, associations with universities increase the level of central business incubators (Lalkaka, Citation2006) is accurate, then the form of cooperation based on the potential of each field needs to be evaluated dynamically.

SO-6: Incubators for businesses seek to increase their tenants’ proficiency in order to increase their chances of survival. In business incubators, the success of a company depends on the nature and delivery of the services provided (Bruneel et al., Citation2012). Carrying the concept of Service-dominant Logic results in the following types of services: providing quality technical assistance that is continuous, measurable, and targeted; professional market validation and marketing validation assistance; internal and external network support for startups; qualified human resources support for becoming a startup mentor; supporting legal approvals in the area of copyright legality and the resulting technological innovations; and supporting p2p (peer-to-peer) networks.

SO-7: Quality of service assistance (Hackett & Dilts, Citation2004). Furthermore, the sort of coaching impacts the tenant company’s success percentage at a given period. The objective is for startups and facilitators to collaborate and successfully solve corporate issues in a methodical manner. During the coaching phase, the startup might get strategic short-term and long-term solutions (Siegel et al., Citation2003)

Good-dominant and Service-dominant logic cannot work separately, according to the seven service orientation assertions. Sustainable economic growth depends on promoting innovation and building new enterprises in the region with various stakeholders (Kakouris et al., Citation2016; Mian, Citation2014). In the University Technology Transfer (UTT) process from the early 1980s, the University Incubation model has fostered and sustained spin-off firms (McAdam et al., Citation2016).

Since then, similar models have grown globally to boost economic growth and development (Mian, Citation2014). The incubation process often involves mentorship and information exchange among varied stakeholders to encourage development and sustainability, according to the literature (Hackett and Dilts, Citation2004; Wu, Citation2010). Thus, government, universities, business, and end-user organizations must collaborate on it (Garrett-Jones et al., Citation2005).

Observation result of good-dominant logic perspective

As a technology-based business incubator, BTP’s physical premises and the physical facilities indicated in the matrix constitute the heart of value co-creation with its players (Amit & Zott, Citation2001; Storbacka et al., Citation2016). However, co-creating value in specific areas requires multiple participants (Kijima & Arai, Citation2016). BTP’s superb physical facilities are useless if the business incubator is not utilised efficiently. Startups can rent whole facilities to reach all actors. However, BTP needs a diversity of players to evaluate who would eventually become the seed of an Indonesian incubator network. Indonesia has a tech incubator ecosystem.

A platform that promises a technology-based composition of physical facilities by integrating various (physical) research facilities that allow start-ups to achieve learning, and build knowledge integration and resource sharing. Physical facilities have duration of use, cost, maintenance, are measurable, and have dimensions / capacities as needed. Such as: land area, electricity, internet connection with a certain capacity, and other measurable physical facilities.

Observation result of service-dominant logic perspective

BTP promotes collaboration among varied players with different origins, perspectives, and interests. Start-ups, BPT program managers, government, industry, mentors, business coaches, investors, and other stakeholders involved in the incubation process are observed. Building mutually beneficial connections fosters research, creativity, and technology. Services focus on intangible value co-creation in technology-based business incubators as well as measured and paid dimension quantities. Technology-based incubators need continual assessment opportunities after deployment. An incubator ecosystem will support start-ups, alumni, mentors, business coaches, and industry, government, and target markets in their learning process.

Service competencies for technology-based business incubator in S-D logics perspective

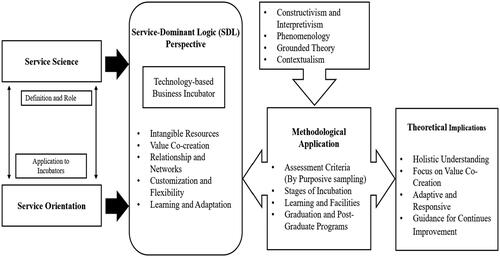

The methodology states that a service science and service orientation framework is used to assess criteria, stages, learning, facilities, graduation, and graduate programs. This makes the theoretical foundation important for this research and suggests a systematic approach to the service-dominant logic perspective, as explained in the theoretical thinking in .

The relationship between the research objectives and research questions is crucial for guiding this study and ensuring that the research outcomes address the intended goals. In this study, the research objectives are aligned with the research questions to provide a comprehensive understanding of the service-dominant logic in technology-based business incubators perspective.

The research objectives, as outlined in the methodology, focus on assessing the criteria, stages, learning, facilities, graduation, and post-graduate programs within technology-based business incubators using a service science and service orientation framework in . These objectives directly relate to the research questions, which seek to understand the impact of the shift from goods-dominant logic to service-dominant logic on technology-based business incubators, the essential services provided by these incubators for startup success, and the application of service-dominant logic principles to assess and improve services in technology-based business incubators.

The alignment between the research objectives and research questions ensures that the study’s methodology and analysis directly address the core inquiries of the research, providing a comprehensive exploration of the service-dominant logic in technology-based business incubators. This connection is essential for maintaining the focus and relevance of the study’s findings. However, S-D Logics gives more value across all phases of the Startup’s incubation cycle. This study identifies seven abilities that managers of technology-based business incubators must possess and improve. This is explained based on the findings of prior investigations. During the indicating process, we identified at least 20 required competences, as shown in .

Table 4. Service-dominant logic technology-based business incubator service competencies.

Discussion and findings

The incubator has fostered the development of technology and business-oriented businesses and research institutions by merging diverse research and development (R&D) teams from universities, government, and industry. This acknowledgment recognizes the synergistic aspect of innovation and the incorporation of diverse research and development (R&D) teams from academic institutions, governmental bodies, and the business sector. The historical trajectory of university business incubators within the university-industry relationship demonstrates a transition from linear to interactive innovation models. The use of accumulated information is increasingly significant in driving innovation in products and startups. In tandem with the incubator’s growth from a self-contained institution to a networked organization, the incubation services transformed, and the collaboration between the university and industry was scrutinized.

Consequently, an interconnected system of networks will expand. As a result of changes in laws and government funding programs, this process of providing services becomes a collaborative effort between universities, industries, and the government to produce value together. The services offered by Bandung Techno Park are meant to include several stakeholders. The Business and Technology Park (BTP), in collaboration with Telkom University and Telkom Education Foundation, oversees the business process goals of the two institutions. This discussion involves active participation from the Local Government, Ministry of Industrial, Ministry of Research and Technology, and several other stakeholders within the technology-based sector. A structured business operation system characterizes Bandung Techno Park’s learning process. However, it also encourages service improvisation and creativity by emphasizing two key components: co-experience and co-development. In this scenario, there is the opportunity to see the influence of many elements on the business process and interactions inside the BTP system, particularly during the incubation phase. Understanding the role of Bandung Techno Park as a platform within a technology-based business incubator ecosystem is crucial for methodically creating value via collaborative efforts.

The S-D Logics standpoint on the implementation of services in technology-based business incubators offers a new design foundation that involves the re-engineering and re-evaluation of many empirically recognized assumptions about the incubation period trajectory for startups.

Conclusions

Paradigm Shift: A paradigm shift from transactional service characteristics to value-in-use, from objective operands to embedded operands that form collaborative variables in a technology-based ecosystem. Thus, tenants and startups see consumer-centricity. Unlike the G-D Logics’ physical facilities, the S-D Logics’ larger breadth allows researchers and managers to better understand and contribute to sustainable innovation.

Framework Study Value: The Service-Dominant Logic (SDL) concept carries a framework that shifts the focus from the temporary and transactional exchange of goods or products to the exchange of value through sustainable services. Essentially, SDL recognizes that value can be created through collaboration between service providers and consumers and that service is the basis of the economy. However, in its implementation, value creation involves many parties, actors, and elements that cannot work independently. The importance of forming collaboration between elements to provide services to each other for success. In the context of technology-based business incubators, the application of SDL can have several valuable essences:

Service Orientation: S-D Logics’ emphasizes understanding and fulfilling consumer needs through optimal service to each other, or in other words, providing the best service to each other. This perspective means focusing on providing services that support business development for startup companies, from the pre-incubation stage, incubation period, to post-incubation. Sustainable synergy to create shared value is not only complete after the startup’s incubation period.

Generalization: In this case, technology-based business incubators such as Bandung Techno Park may have a university business incubator model similar to others in Indonesia. However, there is a different context for more specific operationalization. In that case, institutions must evaluate service management and institutionalization of physical facilities with different parameters, such as affordable prices, reliable network access, collaborative services with partner incubators, and compliance with standard recruitment practices. However, the service orientation concept found in this research is very flexible and can be used.

Interaction in Collaboration: S-D Logics’ emphasizes the importance of collaboration between service providers and consumers. In business incubators, this can be reflected in the close relationship between technology-based business incubators and developing companies, where there is an exchange of knowledge, resources, experience, and support to increase the value mutually achieved. Solving every problem that arises at each incubation stage is no longer following silo problem solving but requires the interaction of various actors and collaboration.

Importance of Knowledge Integration: S-D Logics’ recognizes that knowledge is the key to creating value. In a technology-based business incubator, this can include sharing industry knowledge, technology, best business practices, business ethics, marketing, creative industries, laws and regulations, and involving skills between the technology-based incubator and developing companies.

Results and Value Orientation: Focus on results and customer value is the S-D Logics perspective’s main principle. In this case, the perspective of a technology-based business incubator must be able to measure success not only from a financial perspective but also from the impact of the technology produced by the supported companies on society and the survival of humanity.

Adaptability and Flexibility: S-D Logics’ recognizes that the business environment is constantly changing, and adaptability is critical. In the context of an incubator, this could include flexibility in providing services tailored to each startup’s unique needs.

Technology Use: S-D Logics’ views technology as a tool to facilitate value exchange between service providers and consumers. Technology can increase efficiency, facilitate communication, and provide innovative solutions in business incubators.

Importance of Experience: S-D Logics’ places importance on experience in creating value. In the context of a business incubator, this can mean creating a positive and supportive experience for the startups being mentored.

Applying the essence of Service-Dominant Logic to business incubators can help create an environment that supports the growth and development of startup companies with a focus on providing value through service. Despite limited resources, startups may grow businesses. Due to shared curriculum design experiences, BTP must prepare lessons. It will help startups create products with market-driven technologies and commercial strategy. Innovatively driven. Therefore, assisting startups financially may be a result of the mutual resolve to establish the business’s targeted outcome throughout its initial development phase to enter the open market.

Bandung Techno Park’s technology-based business incubator, as a model for other university business incubators in Indonesia, should evaluate institutionalization of physical facilities at affordable rates, access to reliable networks, collaborative services with partner incubators, and adherence to standardized recruitment practices.

Technology-based business incubators must create and offer continual evaluation. An incubator ecosystem will support start-ups, alumni, mentors, business coaches, and industry, government, and target markets in the innovation conversation. International university cooperation will also be possible. Scientific advancement and global sustainability.

The study’s limitations are its emphasis on the need for continuous evaluation and more inquiry to understand the service-oriented rationale in technology-based business incubators fully. Additionally, it emphasizes the need to use quantitative analysis with more significant sample sizes and longitudinal research approaches. Furthermore, the article admits that the network undergoes expansion and changes throughout time, rendering its complexity unquantifiable.

More research is needed to understand the service-dominant rationale in technology-based business incubators. This sector requires a larger sample size and technology-based incubators to obtain statistical results. Given the location, conditions, and regulatory environment, additional technology-based business incubators may experience the outcomes of this research. This issue needs more research. Thus, while considering future research, it is important to remember that the network expands and changes with time, making its complexity impossible to estimate. Quantitative study with larger samples and comparisons to other incubators is beneficial. A longitudinal research technique and qualitative investigations help us comprehend networks’ complexity and how they improve technology-based incubator enterprises’ services using S-D Logics’.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Eka Yuliana

Eka Yuliana, In 2002, she obtained a Bachelor of Industrial Engineering from the Islamic University of Bandung. She received her Master of Science in Management from the School of Business Management, ITB, in 2010, with a focus on company strategy and marketing. She now has a position as a professor in the School of Economics and Business at Telkom University. The researcher specializes in technology-based incubators and is pursuing a PhD degree in science management at the School of Business Management, ITB. This study is the outcome of a comprehensive review of the literature that underpins the analysis and debate of technology-based business incubators. His research in marketing, entrepreneurship, and consumer behavior expands the range of research findings on knowledge transformation across several disciplines under his supervision. Researchers want to demonstrate the feasibility of creating technology-based business incubators by analyzing them through the lenses of service science and systems thinking. They are very focused on expanding the role of business incubators beyond offering just transactional services and facilities.

Utomo Sarjono Putro

Utomo Sarjono Putro, Professor Utomo graduated with a Bachelor of Engineering from the Department of Industrial Engineering at Institut Teknologi Bandung in 1992, then went on to earn a Master’s degree in Decision Science from the Tokyo Institute of Technology in 1995 and a Doctorate in Decision Science from the Department of Value and Decision Science in 2001. Prof. Utomo has authored book chapters in Springer publications and articles in IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Systems Analysis Modeling Simulation, Systems Research and Behavioral Science, and Procedia Social and Behavioral Science. He presented papers at conferences held by the IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics and the Asia Pacific Conference on Operation Research Society in Japan, Singapore, China, and Vietnam. He provided consultation to state and private firms and governments on negotiation strategies, policy-making using systems modeling, strategic decisionmaking, and decision science. He specializes in studying systems modeling in policy creation, systems thinking, systems approaches to decision-making, negotiation, service sciences, and agent-based modeling. He reads foreign journals such as Systems Research and Behavioral Science and the Asian Journal of Management Science and Applications.

Pri Hermawan

Pri Hermawan, he obtained his Bachelor of Engineering in Electrical Engineering with a Telecommunication Specialization from TELKOM University (STT TELKOM) in Bandung in 1998. He obtained a Master of Engineering degree from the Department of Industrial Engineering and Management at ITB in 2005. The focus of his master’s thesis was on using the adaptive learning model of Hypergame for competitive signaling in corporate marketing interactions. He obtained his doctoral degree in value and decision science from the Tokyo Institute of Technology in Japan in 2009. A scholarship from MEXT: Ministry of Education, Culture, Sport, Science, and Technology (Monbukagakusho) in Japan supported his dissertation, which concentrated on a drama-theoretic analysis of negotiation dilemmas and their application. He is interested in using soft computing for social simulation and using a systems science-based approach to decision-making and bargaining in his study. He has worked as a reviewer for many international publications. He is also an associate professor at School of Business Management ITB; currently, he is the Chief of Decision-Making Science and Negotiation Research Group.

Astri Ghina

Astri Ghina, she is an associate professor in the Master of Management program at the Faculty of Economics and Business. She pursued a chemistry degree at Padjadjaran University from 1998 to 2002. Astri completed her Master of Science in Management degree from the School of Business and Management (SBM) at Institut Teknologi Bandung (ITB) in 2011. She completed her Doctor of Science in Management (DSM) degree from the School of Business and Management (SBM) at Institut Teknologi Bandung (ITB) in 2015.

References

- Abetti, P. A. (2004). Government-supported incubators in the Helsinki Region, Finland: Infrastructure, results, and best practices. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 29(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOTT.0000011179.47666.55

- Adner, R., & Kapoor, R. (2010). Value creation in innovation ecosystems: How the structure of technological interdependence affects firm performance in new technology generations. Strategic Management Journal, 31(3), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.821

- Aerts, K., Matthyssens, P., & Vandenbempt, K. (2007). Critical role and screening practices of European business incubators. Technovation, 27(5), 254–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2006.12.002

- Akaka, M. A., & Vargo, S. L. (2014). Technology as an operant resource in service (eco)systems. Information Systems and e-Business Management, 12(3), 367–384. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10257-013-0220-5

- Allen, D. N., & McCluskey, R. (1991). Structure, policy, services, and performance in the business incubator industry. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 15(2), 61–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879101500207

- Allen, D. N., & Rahman, S. (1985). Small business incubators: A positive environment for entrepreneurship. Journal of Small Business Management, 23(000003), 12.

- Allen, D. N., & Weinberg, M. L. (1988). State investment in business incubators. Public Administration Quarterly, 12(2), 196–215. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40861417

- Almoli, A. (2018). Towards Knowledge-Based Economy; Qatar Science and Technology Park, Performance and Challenges. Doctoral dissertation, Hamad Bin Khalifa University (Qatar)).

- Amit, R., & Zott, C. (2001). Value creation in e–business. Strategic Management Journal, 22(6–7), 493–520. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.187

- Autio, E., & Levien, J. (2017). Management of Entrepreneurial Ecosystems. In: G. Ahmetoglu, T. Chamorro-Premuzic, B. Klinger & T. Karcisky (Eds). The Wiley handbook of entrepreneurship (pp. 423–499). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- Baker, W., Nohria, N., & Eccles, R. G. (1992). The network organization in theory and practice. Classics of Organization Theory, 8, 401–2016.

- Becker, B., & Gassmann, O. (2006). Gaining leverage effects from knowledge modes within corporate incubators. R&D Management, 36(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9310.2005.00411.x

- Bøllingtoft, A., & Ulhøi, J. P. (2005). The networked business incubator—Leveraging entrepreneurial agency? Journal of Business Venturing, 20(2), 265–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2003.12.005

- Bruneel, J., Ratinho, T., Clarysse, B., & Groen, A. (2012). The evolution of business incubators: comparing demand and supply of business incubation services across different incubator generations. Technovation, 32(2), 110–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2011.11.003

- Campbell, C. (1989). Change agents in the new economy: business incubators and E. Economic Development Review, 7(2), 56.

- Carayannis, E. G., & Von Zedtwitz, M. (2005). Architecting gloCal (global–local), real-virtual incubator networks (G-RVINs) as catalysts and accelerators of entrepreneurship in transitioning and developing economies: Lessons learned and best practices from current development and business incubation practices. Technovation, 25(2), 95–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-4972(03)00072-5

- Chan, K. F., & Lau, T. (2005). Assessing technology incubator programs in the science park: The good, the bad and the ugly. Technovation, 25(10), 1215–1228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2004.03.010

- Chandra, A., & Fealey, T. (2009). Business incubation in the United States, China and Brazil: A comparison of role of government, incubator funding and financial. International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 13, 67.

- Chesbrough, H. W. (2006). Open innovation: The new imperative for creating and profiting from technology. Harvard Business Press.

- Chesbrough, H., & Spohrer, J. (2006). A research manifesto for services science. Communications of the ACM, 49(7), 35–40. https://doi.org/10.1145/1139922.1139945

- Dikti, D. (2017). Buku Panduan Pelaksanaan Penelitian dan Pengabdian Kepada Masyarakat Edisi XI Tahun 2017.

- Donofrio, N., Sanchez, C., & Spohrer, J. (2010). Collaborative innovation and service systems. In Holistic engineering education (pp. 243–269). Springer.

- Etzkowitz, H. (2002). MIT and the rise of entrepreneurial science. Routledge.

- Etzkowitz, H., & Zhou, C. (2017). The triple helix: University–industry–government innovation and entrepreneurship. Routledge.

- Falkäng, J., & Alberti, F. (2000). The assessment of entrepreneurship education. Industry and Higher Education, 14(2), 101–108. https://doi.org/10.5367/000000000101294931

- Fayolle, A., Gailly, B., & Lassas-Clerc, N. (2006). Assessing the impact of entrepreneurship education programmes: a new methodology. Journal of European Industrial Training, 30(9), 701–720. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090590610715022

- Ford, D., & Håkansson, H. (2013). Competition in business networks. Industrial Marketing Management, 42(7), 1017–1024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2013.07.015

- Gannage, G. J.Jr, (2014). A discussion of goods-dominant logic and service dominant logic: A synthesis and application for service marketers. Journal of Service Science (JSS), 7(1), 1–16.

- Garrett-Jones, S., Turpin, T., Burns, P., & Diment, K. (2005). Common purpose and divided loyalties: The risks and rewards of cross-sector collaboration for academic and government researchers. R and D Management, 35(5), 535–544. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9310.2005.00410.x

- Grimaldi, R., & Grandi, A. (2005). Business incubators and new venture creation: An assessment of incubating models. Technovation, 25(2), 111–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-4972(03)00076-2

- Grönroos, C. (2008). Service logic revisited: who creates value? And who co-creates? European Business Review, 20(4), 298–314. https://doi.org/10.1108/09555340810886585

- Gummesson, E. (2017). From relationship marketing to total relationship marketing and beyond. Journal of Services Marketing, 31(1), 16–19. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-11-2016-0398

- Gummesson, E., Mele, C., Polese, F., Nenonen, S., & Storbacka, K. (2010). Business model design: Conceptualizing networked value co-creation. International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences, 2(1), 43–59. https://doi.org/10.1108/17566691011026595

- Hackett, S. M., & Dilts, D. M. (2004). A systematic review of business incubation research. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 29(1), 55–82. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOTT.0000011181.11952.0f

- Hannon, P. D. (2005). Incubation policy and practice: Building practitioner and professional capability. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 12(1), 57–75. https://doi.org/10.1108/14626000510579644

- Hansen, M. T., Chesbrough, H. W., Nohria, N., & Sull, D. N. (2000). Networked incubators. Harvard Business Review, 78(5), 74–84, 199.

- Harwitt, E. (2002). High technology incubators: Fuel for China’s new entrepreneurship? China Business Review, 29(4), 26–29.

- Kakouris, A., Dermatis, Z., & Liargovas, P. (2016). Educating potential entrepreneurs under the perspective of Europe 2020 plan. Business & Entrepreneurship Journal, 5(1), 7–24.

- Karpen, I. O., Bove, L. L., & Lukas, B. A. (2012). Linking service-dominant logic and strategic business practice: A conceptual model of a service-dominant orientation. Journal of Service Research, 15(1), 21–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670511425697

- Kijima, K., & Arai, Y. (2016). Value co-creation process and value orchestration. Japan: Global perspectives on service science, 137–154.

- Kohler, T. (2016). Corporate accelerators: Building bridges between corporations and start-ups. Business Horizons, 59(3), 347–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2016.01.008

- Lalkaka, R. (2000). Rapid growth of business incubation in China: Lessons for developing and restructuring countries. WAITRO – World Association of Industrial and Technological Research Organizations.

- Lalkaka, R. (2001, November). Best practices in business incubation: Lessons (yet to be) learned. In International Conference on Business Centers: Actors for Economic & Social Development. Brussels, November (pp. 14–15).

- Lalkaka, R. (2002). Technology business incubators to help build an innovation-based economy. Journal of change management, 3(2), 167–176.

- Lalkaka, R. (2006). Technology business incubation: A toolkit on innovation in engineering, science and technology (vol. 255). UNESCO.

- Lee, S. S., & Osteryoung, J. S. (2004). A comparison of critical success factors for effective operations of university business incubators in the United States and Korea. Journal of Small Business Management, 42(4), 418–426. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-627X.2004.00120.x

- Lendner, C., & Dowling, M. (2003). University business incubators and the impact of their networks on the success of start-ups: An international study. In International Conference on Science Parks and Incubators. Troy, NY: Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.

- Lusch, R. F., & Vargo, S. L. (2006). Service-dominant logic: Reactions, reflections, and refinements. Marketing Theory, 6(3), 281–288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593106066781

- Lusch, R. F., Vargo, S. L., & O’brien, M. (2007). Competing through service: Insights from service-dominant logic. Journal of Retailing, 83(1), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2006.10.002

- Maglio, P. P., Kieliszewski, C. A., Spohrer, J. C., Lyons, K., Patrício, L., & Sawatani, Y. (Eds.) (2019). Handbook of Service Science, Volume II. Springer International Publishing.

- Maglio, P. P., & Spohrer, J. (2008). Fundamentals of service science. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36(1), 18–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-007-0058-9

- McAdam, M., & McAdam, R. (2008). High tech start-ups in University Science Park incubators: The relationship between the start-up’s lifecycle progression and use of the incubator’s resources. Technovation, 28(5), 277–290. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9310.2005.00411.x

- McAdam, M., Miller, K., & McAdam, R. (2016). Situated regional university incubation: A multi-level stakeholder perspective. Technovation, 50-51, 69–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2015.09.002

- Merrifield, D. B. (1987). New business incubators. Journal of Business Venturing, 2(4), 277–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-9026(87)90021-8

- Mian, S. (2014). Business incubation and incubator mechanisms. In Handbook of research on entrepreneurship. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Mian, S. A. (1997). Assessing and managing the university technology business incubator: An integrative framework. Journal of Business Venturing, 12(4), 251–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(96)00063-8

- Mian, S., Lamine, W., & Fayolle, A. (2016). Technology business incubation: An overview of the state of knowledge. Technovation, 50-51, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2016.02.005

- Michel, S., Brown, S. W., & Gallan, A. S. (2008). An expanded and strategic view of discontinuous innovations: Deploying a service-dominant logic. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36(1), 54–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-007-0066-9

- Ng, I. C., & Vargo, S. L. (2018). Service-dominant (SD) logic, service ecosystems and institutions: Bridging theory and practice. Journal of Service Management, 29(4), 518–520. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-07-2018-412

- Normann, R. (2001). Reframing business: When the map changes the landscape. John Wiley & Sons.

- Ogutu, V. O., & Kihonge, E. (2016). Impact of business incubators on economic growth and entrepreneurship development. International Journal of Science and Research, 5(5), 231–241.

- Phan, P. H., Siegel, D. S., & Wright, M. (2005). Science parks and incubators: Observations, synthesis and future research. Journal of Business Venturing, 20(2), 165–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2003.12.001

- Phillips, R. G. (2002). Technology business incubators: How effective as technology transfer mechanisms? Technology in Society, 24(3), 299–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-791X(02)00010-6

- Polat, G. (2021). A dynamic business model for Turkish techno parks: Looking through the lenses of service perspective and stakeholder theory. Journal of Science and Technology Policy Management, 13(2), 244–272. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSTPM-12-2020-0170

- Prahalad, C. K., & Bettis, R. A. (1986). The dominant logic: A new linkage between diversity and performance. Strategic Management Journal, 7(6), 485–501. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250070602

- Prahalad, C. K., & Ramaswamy, V. (2004). The future of competition: Co-creating unique value with customers. Harvard Business Press. https://doi.org/10.1108/10878570410699249

- Rothaermel, F. T., & Thursby, M. (2005). University–incubator firm knowledge flows: Assessing their impact on incubator firm performance. Research Policy, 34(3), 305–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2004.11.006

- Santos, F. M., & Eisenhardt, K. M. (2009). Constructing markets and shaping boundaries: Entrepreneurial power in nascent fields. Academy of Management Journal, 52(4), 643–671. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2009.43669892

- Saviano, M., Barile, S., Spohrer, J. C., & Caputo, F. (2017). A service research contribution to the global challenge of sustainability. Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 27(5), 951–976. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSTP-10-2015-0228

- Scaramuzzi, E. (2002). Incubators in developing countries: Status and development perspectives (pp. 1–35). The World Bank.

- Schwartz, M., & Hornych, C. (2008). Specialization as strategy for business incubators: An assessment of the Central German Multimedia Center. Technovation, 28(7), 436–449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2008.02.003

- Scillitoe, J. L., & Chakrabarti, A. K. (2010). The role of incubator interactions in assisting new ventures. Technovation, 30(3), 155–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2009.12.002

- Shane, S. (2004). Academic entrepreneurship: University spinoffs and wealth creation. Edward Elgar.

- Siegel, D. S., Waldman, D. A., Atwater, L. E., & Link, A. N. (2003). Commercial knowledge transfers from universities to firms: improving the effectiveness of university–industry collaboration. The Journal of High Technology Management Research, 14(1), 111–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1047-8310(03)00007-5

- Siltaloppi, J., Koskela-Huotari, K., & Vargo, S. L. (2016). Institutional complexity as a driver for innovation in service ecosystems. Service Science, 8(3), 333–343. https://doi.org/10.1287/serv.2016.0151

- Smilor, R. (1986). The new business incubator: linking talent, technology, capital, and know-how. Discussion about early business incubator development (Vol. 1). Lanham, Mayland USA: Lexington Books.

- Smilor, R. W., & Gill, M. D. (1986). The new business incubator: Linking talent, technology, capital, and know-how. https://lccn.loc.gov/85045009

- Smilor, R. W. (1987a). Commercializing technology through new business incubators. Research Management, 30(5), 36–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/00345334.1987.11757061

- Smilor, R. W. (1987b). Managing the incubator system: Critical success factors to accelerate new company development. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, EM-34(3), 146–155. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEM.1987.6498875

- Soetanto, D. P., & Jack, S. L. (2013). Business incubators and the networks of technology-based firms. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 38(4), 432–453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-011-9237-4

- Somsuk, N., & Laosirihongthong, T. (2014). A fuzzy AHP to prioritize enabling factors for strategic management of university business incubators: Resource-based view. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 85, 198–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2013.08.007

- Spohrer, J., Anderson, L., Pass, N., & Ager, T. (2008). Service science and service-dominant logic. In Otago Forum, 2(2, No), 4–18. December.

- Spohrer, J., & Maglio, P. (2008). The emergence of service science: Toward systematic service innovations to accelerate co-creation of value. Production and Operations Management, 17(3), 238–246. https://doi.org/10.3401/poms.1080.0027

- Spohrer, J., Vargo, S. L., Maglio, P., & Caswell, N. (2008 The Service System is the Basic Abstraction of Service Science [Paper presentation]. In Hawaiian International Conference on Systems Sciences (HICSS).

- Storbacka, K., Brodie, R. J., Böhmann, T., Maglio, P. P., & Nenonen, S. (2016). Actor engagement as a microfoundation for value co-creation. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), 3008–3017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.02.034

- Vargo, S. L. (2009). Toward a transcending conceptualization of relationship: A service-dominant logic perspective. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 24(5/6), 373–379. https://doi.org/10.1108/08858620910966255

- Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2004a). Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. Journal of Marketing, 68(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.68.1.1.24036

- Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2004b). The four service marketing myths: Remnants of a goods-based, manufacturing model. Journal of Service Research, 6(4), 324–335. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670503262946

- Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2008). Service-dominant logic: Continuing the evolution. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-007-0069-6

- Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2016). Institutions and axioms: An extension and update of service-dominant logic. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 44(1), 5–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-015-0456-3

- Vargo, S. L., Maglio, P. P., & Akaka, M. A. (2008). On value and value co-creation: A service systems and service logic perspective. European Management Journal, 26(3), 145–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2008.04.003

- Von Zedtwitz, M., & Grimaldi, R. (2006). Are service profiles incubator-specific? Results from an empirical investigation in Italy. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 31(4), 459–468. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-006-0007-7

- Webb, J. W., Tihanyi, L., Ireland, R. D., & Sirmon, D. G. (2009). You say illegal, i say legitimate:entrepreneurship in the informal economy. Academy of Management Review, 34(3), 492–510. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2009.40632826

- Wright, M., Clarysse, B., Mustar, P., & Lockett, A. (2007). Academic entrepreneurship in Europe. Edward Elgar.

- Wu, W. (2010). Managing and incentivizing research commercialization in Chinese Universities. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 35(2), 203–224. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-009-9116-4

- Yan, J., Ye, K., Wang, H., & Hua, Z. (2010). Ontology of collaborative manufacturing: Alignment of service-oriented framework with service-dominant logic. Expert Systems with Applications, 37(3), 2222–2231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2009.07.051

- Yu, E., & Sangiorgi, D. (2018). Service design as an approach to implement the value co-creation perspective in new service development. Journal of Service Research, 21(1), 40–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670517709356